Abstract

This study provides insights into the efficacy of FASB ASC 250 by examining the impact of material changes in accounting estimates (MCEs) on the usefulness of earnings. We find that MCEs, on average, increase the usefulness of earnings measured by the predictive ability of earnings for future cash flows and investor responsiveness to earnings news. Although the results suggest that some firms time their implementation of MCEs to meet desired earnings targets, we also find that ASC 250 disclosures attract investors’ and regulators’ scrutiny, suggesting that MCEs are a costly earnings management tool. Collectively, our findings provide limited support for the widespread use of MCEs for earnings management and suggest that this use is much more nuanced than suggested by prior research. Finally, notwithstanding the benefits of ASC 250 disclosures, our descriptive analysis of related disclosures of accounting estimates suggests that there is room for further improvements in current disclosure practices and regulatory monitoring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data are publicly available from the sources identified in the paper.

Notes

Examples of accounting estimates in financial statements include net realizable value of inventories and accounts receivable, property and casualty insurance loss reserves, estimates of revenues from long-term contracts, depreciation expense, impairment of long-lived assets, and pension and warranty expenses. See Appendix 1 for more examples.

To be useful, accounting information must aid users in the assessment of firms’ prospective cash flows and attain a minimum level of relevance and reliability (now faithful representation). Beyond these minimum levels, usefulness may increase by sacrificing reliability for relevance or vice versa (FASB 1978, 1980, 2010).

A full transcript of Robert Herdman’s speech can be found at https://www.sec.gov/news/speech/spch537.htm.

This issue is pertinent to Chung et al. (2022), as it focuses on documenting the opportunistic timing of MCEs to achieve earnings targets.

For instance, Jeffrey Mahoney, general counsel of the Council of Institutional Investors, states: “Investors as a group … want more disclosures about these estimates and they want auditors to tell them more about what they’ve done” (PCAOB Standing Advisory Group meeting on October 2, 2014 on Auditing Accounting Estimates and Fair Value Measurement, Unofficial transcript pages 69, 76). Moreover, in our manual inspection of some of the MCE disclosures, we similarly find that the disclosure is generally vague (Appendix 2 lists MCE disclosure examples.).

Until the early 2000s, researchers did not distinguish between changes in accounting principles and changes in accounting estimates, although APB Opinion 20 required different accounting treatments. For example, studies in the 1980s and 1990s used both changes in accounting principles and changes in accounting estimates to examine how firms used accounting changes to achieve certain goals (Moses 1987; Lilien et al. 1988; Pincus and Wasley 1994).

The FASB’s conceptual framework asserts that relevance and reliability (now faithful representation) are the two fundamental characteristics of decision usefulness of accounting information (FASB 1980, 2010). In 2010, the FASB replaced reliability (i.e., information that is verifiable, neutral, and representationally faithful) with faithful representation (i.e., information that is complete, neutral, and free from error). It also removed discussion of the trade-off between relevance and reliability. The 2010 revision to the conceptual framework left the definition of relevance largely unchanged, and predictive value continues to be a primary aspect of relevance. Regardless of the removal of the relevance-reliability trade-off discussion in SFAC No. 8 (FASB 2010), the trade-off still exists in accrual accounting as a practical matter, and we use it to motivate our analysis.

We use the post-tax, current-quarter estimated net income impact reported in Audit Analytics. If this amount is not reported, we use the pre-tax estimated net income impact and estimate the post-tax amount based on the tax rate implied from the tax expense account. If only year-to-date amounts are reported, we estimate the quarterly impact by dividing the estimated net income impact by the number of the quarter. For example, if a firm reports an MCE and the related year-to-date income effects in the second quarter 10-Q, we would divide the year-to-date income effect by 2.

In an untabulated sensitivity analysis, we use operating cash flows in q + 1, as the dependent variable to accommodate the possibility that certain estimates are realized one quarter ahead. Our results are not sensitive to this change.

Surprise is measured using IBES “street earnings,” which can exclude items that appear in GAAP earnings. Common non-GAAP exclusions include stock-based compensation, restructuring charges, depreciation, and taxes, all estimates that may also be an MCE. If an MCE is excluded by IBES, we would back out the MCE from a number that already excludes the MCE. To assess this issue, we manually compared the Reg G reconciliation reported within the press release to the IBES actual number for a random sample of 30 MCE observations. Based on this hand collection, we estimate that less than 15 percent of our MCE observations are impacted by potential double-counting. As a sensitivity analysis, we re-estimate our results within a sample of MCE observations where the IBES actuals reported equals GAAP and find similar results to those reported here.

Like prior research, we use the IBES unadjusted database to obtain quarterly actual earnings per share (EPS) and quarterly consensus analyst forecasts (e.g., Payne and Thomas 2003; Doyle et al. 2013). If the actual EPS is equal to or greater than the median forecast, the firm meets or beats the analyst forecast (i.e., MB = 1). If the actual EPS is less than the median forecast, the firm misses the analyst forecast (i.e., MB = 0).

We find similar results when we define Pre-MCE Extreme Beat as pre-MCE earnings exceeding the median analyst forecast by more than $0.02.

Chung et al. (2022) additionally control for whether the MCE was first disclosed in a 10-K filing. Our model captures this control by including quarter-year fixed effects.

In untabulated results, we limit the sample to only observations where the filing date and earnings announcement date are the same and find similar results.

As a sensitivity test, we re-estimate the results in Table 6 within subsample of firms that report at least one MCE and a further restricted subsample of the three quarters preceding the MCE and the MCE quarter. We continue to find similar results.

310 out of 1,170 positive MCEs (26.5 percent) are classified as Timed Positive MCE, and 508 out of 889 negative MCEs (57.1 percent) are classified as Timed Negative MCE. The frequencies are not tabulated but available upon request.

Pre-MCE Just Miss is excluded from the Timed Negative MCE model because, by definition, they are mutually exclusive.

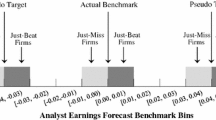

This result does not imply that the mean effect of negative MCEs on the meet/beat likelihood is positive. Figure 1 Panel B suggests that negative MCEs shift the distribution of earnings surprises to the left, suggesting that negative MCEs on average decrease the likelihood of meet/beat.

We conduct a Chi2 test of coefficients and find a test statistic equal to 2.86 and significant at the p < 0.10 level.

While MCE is a quarterly disclosure, quantitative CAE disclosures are reported annually.

References

Albrecht, A., E.G. Mauldin, and N.J. Newton. 2018. Do auditors recognize the potential dark side of executives’ accounting competence? The Accounting Review 93 (6): 1–28.

Altamuro, J., A.L. Beatty, and J. Weber. 2005. The effects of accelerated revenue recognition on earnings management and earnings informativeness: Evidence from SEC staff accounting bulletin No. 101. The Accounting Review 80 (2): 373–401.

An, H., Y.W. Lee, and T. Zhang. 2014. Do corporations manage earnings to meet/exceed analyst forecasts? Evidence from pension plan assumption changes. Review of Accountings Studies 19 (2): 698–735.

Baber, W.R., S. Chen, and S.H. Kang. 2006. Stock price reaction to evidence of earnings management: Implications for supplementary financial disclosure. Review of Accounting Studies 11 (1): 5–19.

Badertscher, B.A., D.W. Collins, and T.Z. Lys. 2012. Discretionary accounting choices and the predictive ability of accruals with respect to future cash flows. Journal of Accounting and Economics 53 (1–2): 330–352.

Balsam, S., E. Bartov, and C. Marquardt. 2002. Accruals management, investor sophistication, and equity valuation: Evidence from 10-Q filings. Journal of Accounting Research 40 (4): 987–1012.

Barth, M.E., D. Cram, and K. Nelson. 2001. Accruals and the prediction of future cash flows. The Accounting Review 76 (1): 27–58.

Barth, M.E., G. Clinch, and D. Israeli. 2016. What do accruals tell us about future cash flows? Review of Accounting Studies 21 (3): 768–807.

Bloomfield, R.J. 2002. The “incomplete revelation hypothesis” and financial reporting. Accounting Horizons. 16 (3): 233–243.

Bradshaw, M.T., L.F. Lee, and K. Peterson. 2016. The interactive role of difficulty and incentives in explaining the annual earnings forecast walkdown. The Accounting Review 91 (4): 995–1021.

Brown, L.D., and M.L. Caylor. 2005. A temporal analysis of quarterly earnings thresholds: Propensities and valuation consequences. The Accounting Review 80 (2): 423–440.

Burgstahler, D., and M. Eames. 2006. Management of earnings and analysts’ forecasts to achieve zero and small positive earnings surprises. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 33 (5–6): 633–652.

Bushman, R.M., and A.J. Smith. 2001. Financial accounting information and corporate governance. Journal of Accounting and Economics 32 (1–3): 237–333.

Bushman, R.M., and A.J. Smith. 2003. Transparency, financial accounting information, and corporate governance. FRBNY Economic Policy Review 9 (1): 65–87.

Cassell, C.A., L.A. Myers, and T.A. Seidel. 2015. Disclosure transparency about activity in valuation allowance and reserve accounts and accruals-based earnings management. Accounting, Organizations and Society 46: 23–38.

Christensen, B.E., S.M. Glover, and D.A. Wood. 2012. Extreme estimation uncertainty in fair value estimates: Implications for audit assurance. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory 31 (1): 127–146.

Cohen, D., M.N. Darrough, R. Huang, and T. Zach. 2011. Warranty reserve: Contingent liability, information signal, or earnings management tool? The Accounting Review 86 (2): 569–604.

Collins, D., and S. Kothari. 1989. An analysis of inter-temporal and cross-sectional determinants of earnings response coefficients. Journal of Accounting and Economics 11: 143–181.

Chuk, E.C. 2013. Economic consequences of mandated accounting disclosures: Evidence from pension accounting standards. The Accounting Review 88 (2): 395–427.

Chung, P.K., M.A. Geiger, D.G. Paik, and C. Rabe. 2022. Do firms times changes in accounting estimates to manage earnings? Contemporary Accounting Research 39 (2): 917–946.

Comprix, J., and K.A. Muller. 2011. Pension plan accounting estimates and the freezing of defined benefit pension plans. Journal of Accounting and Economics 51 (1): 115–133.

Das, S., K. Kim, and S. Patro. 2011. An analysis of managerial use and market consequences of earnings management and expectation management. The Accounting Review 86 (6): 1935–1967.

Dechow, P.M. 1994. Accounting earnings and cash flows as measures of firm performance: The role of accounting accruals. Journal of Accounting and Economics 18 (1): 3–42.

Dechow, P.M., S.P. Kothari, and R.L. Watts. 1998. The relation between earnings and cash flows. Journal of Accounting and Economics 25 (2): 133–168.

Dechow, P.M., W. Ge, and C. Schrand. 2010. Understanding earnings quality: A review of the proxies, their determinants and their consequences. Journal of Accounting and Economics 50 (2–3): 344–401.

DeFond, M.L., and C.W. Park. 2001. The reversal of abnormal accruals and the market valuation of earnings surprises. The Accounting Review 76 (3): 375–404.

Dhaliwal, D.S., C.A. Gleason, and L.F. Mills. 2004. Last-change earnings management: Using the tax expense to meet analysts’ forecasts. Contemporary Accounting Research 21 (2): 431–459.

Doyle, J.T., J.N. Jennings, and M.R. Soliman. 2013. Do managers define non-GAAP earnings to meet or beat analyst forecasts? Journal of Accounting and Economics 56 (1): 40–56.

Drake, K.D., N.C. Goldman, S.J. Lusch, and J.J. Schmidt. 2021. Does the initial disclosure of tax-related critical audit matters constrain tax-related earnings management? Working paper.

Easton, P.D. 1999. Security returns and the value relevance of accounting data. Accounting Horizons 13 (4): 399–412.

Ettredge, M., S. Scholz, K.R. Smith, and L. Sun. 2010. How do restatements begin? Evidence of earnings management preceding restated financial reports. Journal of Business, Finance & Accounting 37 (3–4): 332–355.

Fields, T.D., T.Z. Lys, and L. Vincent. 2001. Empirical research on accounting choices. Journal of Accounting and Economics 31 (1–3): 255–307.

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). 1978. Objectives of Financial Reporting by Business Enterprises. Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 1. FASB, Norwalk

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). 1980. Qualitative Characteristics of Accounting Information. Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 2. FASB, Norwalk.

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). 2005. SFAS No. 154: Accounting changes and error corrections. FASB, Norwalk.

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). 2009. Accounting Standards Codification Topic No. 250: Accounting changes and error corrections. FASB, Norwalk.

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB). 2010. Conceptual Framework for Financial Reporting. Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 8. FASB, Norwalk.

Francis, J.R., and B. Ke. 2006. Disclosure of fees paid to auditors and the market valuation of earnings surprises. Review of Accounting Studies 46: 23–38.

Glendening, M. 2017. Critical accounting estimate disclosures and the predictive value of earnings. Accounting Horizons 31 (4): 1–12.

Glendening, M., E. Mauldin, and K.W. Shaw. 2019. Determinants and consequences of quantitative critical accounting estimate disclosures. The Accounting Review 94 (5): 189–218.

Graham, J.R., C.R. Harvey, and S. Rajgopal. 2005. Value destruction and financial reporting decisions. Financial Analysts Journal 62 (6): 27–39.

Griffith, E.E., J.S. Hammersley, and K. Kadous. 2015. Auditor mindsets and audits of complex estimates. Journal of Accounting Research 53 (1): 49–77.

Hirst, D.E., and P.E. Hopkins. 1998. Comprehensive income reporting and analysts’ valuation judgments. Journal of Accounting Research 36: 47–75.

Huang, M., N.T. Jenkins, and H. Xie. 2021. Mandatory repurchase disclosure, opportunistic repurchases, and their real effects. Working paper.

Jackson, S.B., and X. Liu. 2010. The allowance for uncollectible accounts, conservatism, and earnings management. Journal of Accounting Research 48 (3): 565–601.

Jo, H., and Y. Kim. 2007. Disclosure frequency and earnings management. Journal of Financial Economics 84 (2): 561–590.

Jones, J.J. 1991. Earnings management during import relief investigations. Journal of Accounting Research 29 (2): 193–228.

Kasznik, R., and M.F. McNichols. 2002. Does meeting earnings expectations matter? Evidence from analyst forecast revisions and share prices. Journal of Accounting Research 40 (3): 727–759.

Kothari, S.P. 2001. Capital markets research in accounting. Journal of Accounting and Economics 31: 105–231.

Kothari, S.P., A.J. Leone, and C.E. Wasley. 2005. Performance matched discretionary accrual measures. Journal of Accounting & Economics 39 (1): 163–197.

Lev, B., S. Li, and T. Sougiannis. 2010. The usefulness of accounting estimates for predicting cash flows and earnings. Review of Accounting Studies 15 (4): 779–807.

Li, K.K., and R.G. Sloan. 2017. Has goodwill accounting gone bad? Review of Accounting Studies 22 (2): 964–1003.

Lilien, S., M. Mellman, and V. Pastena. 1988. Accounting changes: Successful versus unsuccessful firms. Accounting Review 63 (4): 642–656.

Linck, J.S., J. Netter, and T. Shu. 2013. Can managers use discretionary accruals to ease financial constraints? Evidence from discretionary accruals prior to investment. The Accounting Review 88 (6): 2117–2143.

Liu, J., and J. Thomas. 2000. Stock returns and accounting earnings. Journal of Accounting Research 38 (1): 71–101.

Lopez, T.J., and L. Rees. 2002. The effect of beating and missing analysts’ forecasts on the information content of unexpected earnings. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance 17 (2): 155–184.

Lundholm, R.J. 1999. Reporting on the past: A new approach to improving accounting today. Accounting Horizons 13 (4): 315–322.

Matsumoto, D.A. 2002. Management’s incentives to avoid negative earnings surprises. The Accounting Review 77 (3): 483–514.

McNichols, M., and G.P. Wilson. 1988. Evidence of earnings management from the provision for bad debts. Journal of Accounting Research 26: 1–31.

Moehrle, S.R. 2002. Do firms use restructuring charge reversals to meet earnings targets? The Accounting Review 77 (2): 397–413.

Moses, O.D. 1987. Income smoothing and incentives: Empirical tests using accounting changes. Accounting Review 62: 358–377.

Nam, S., F. Brochet, and J. Ronen. 2012. The predictive value of accruals and consequences for market anomalies. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance 27 (2): 151–176.

Payne, J.L., and W.B. Thomas. 2003. The implications of using stock-split adjusted I/B/E/S data in empirical research. The Accounting Review 78 (4): 1049–1067.

Pincus, M., and C. Wasley. 1994. The incidence of accounting changes and characteristics of firms making accounting changes. Accounting Horizons 8 (2): 1–24.

Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). 2017. AS 3101: The auditor’s report on an audit of financial statements when the auditor expresses an unqualified opinion. Washington, DC: PCAOB.

Richardson, S.A., R.G. Sloan, M.T. Soliman, and I.R. Tuna. 2006. The implications of accounting distortions and growth for accruals and profitability. The Accounting Review 81 (3): 713–743.

Schipper, K. 1989. Commentary on earnings management. Accounting Horizons 3 (4): 91–102.

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). 2020. Securities Act Release Nos.: 33-10890; 34-90459; Management’s Discussion and Analysis, Selected Financial Data, and Supplementary Financial Information. https://www.sec.gov/rules/final/2020/33-10890.pdf.

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). 2001. Securities Act Release Nos.: 33-8040; 34-45149; FR-60. Cautionary Advice Regarding Disclosure About Critical Accounting Policies. https://www.sec.gov/rules/other/33-8040.htm.

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). 2002. Speech by SEC Staff: Critical Accounting and Critical Disclosures. https://www.sec.gov/news/speech/spch537.htm.

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). 2003. Interpretation: Commission Guidance Regarding Management's Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of Operations. https://www.sec.gov/rules/interp/33-8350.htm.

Seidel, T.A., C.A. Simon, and N.M. Stephens. 2020. Management bias across multiple accounting estimates. Review of Accounting Studies 25 (1): 1–53.

Skinner, D.J., and R.G. Sloan. 2002. Earnings surprises, growth expectations, and stock returns or don’t let an earnings torpedo sink your portfolio. Review of Accounting Studies 7 (2–3): 289–312.

Subramanyam, K.R. 1996. The pricing of discretionary accruals. Journal of Accounting and Economics 22 (1–3): 249–281.

Trompeter, G.M., T.D. Carpenter, K.L. Jones, and R.A. Riley. 2014. Insights for research and practice: What we learn about fraud from other disciplines. Accounting Horizons 28 (4): 769–804.

Turner, L.E. 2001. Speech by SEC Staff: “A Menu of Soup du Jour Topics.” 20th Annual SEC and Financial Reporting Institute Conference Sponsored by The Leventhal School of Accounting, Marshall School of Business Administration, University of Southern California Pasadena, California. Available at: https://www.sec.gov/news/speech/spch498.htm.

Vuong, Q.H. 1989. Likelihood ratio tests for model selection and non-nested hypotheses. Econometrica 57: 307–333.

Acknowledgements

We thank Richard Sloan (editor) and the anonymous reviewer for their invaluable comments and suggestions. We also thank Brant Christensen, Jere Francis, Inder Khurana, Melissa Lewis-Western, Joshua Lee, Karen Nelson, Sukesh Patro, Mark Riley, Roy Schmardebeck, Ken Shaw, and the workshop participants at the Securities and Exchange Commission, the 2017 FARS midyear meeting, 2017 AAA annual meeting, 2018 EAA annual conference, Northern Illinois University, Texas Christian University, University of Missouri-Columbia, and the 2020 Texas Lonestar conference for their feedback.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

1.1 Examples of accounting estimates

(Obtained from PCAOB interim standard AU 342 Auditing Accounting Estimates)

Category | Examples |

|---|---|

Revenue | Airline passenger revenue, subscription income, freight and cargo revenue, dues income, losses on sales contracts |

Contracts | Revenue to be earned, costs to be incurred, percent of completion |

Receivables | Uncollectible receivables, allowance for loan losses, uncollectible pledges |

Inventories | Obsolete inventory, net realizable value of inventories where future selling prices and future costs are involved, losses on purchase commitments |

Financial Instruments | Valuation of securities, trading versus investment security classification, probability of high correlation of a hedge, sales of securities with puts and calls |

Leases | Initial direct costs, executory costs, residual values |

Property, Plant & Equipment, Intangibles | Useful lives and residual values, depreciation and amortization methods, recoverability of costs, recoverable reserves |

Litigation | Probability of loss, amount of loss |

Tax and Interest | Annual effective tax rate in interim reporting, imputed interest rates on receivables and payables |

Accruals | Property and casualty insurance company loss reserves, compensation in stock option plans and deferred plans, warranty claims, taxes on real and personal property, renegotiation refunds, actuarial assumptions in pension costs |

Other | Losses and net realizable value on disposal of segment or restructuring of a business, fair values in nonmonetary exchanges, interim period costs in interim reporting |

Appendix 2

2.1 Disclosure on material changes in estimates (examples)

2.1.1 From Boeing Co 6/30/12 10-Q filed on 7/25/12

Contract accounting is used for development and production activities predominantly by Defense, Space & Security (BDS). Contract accounting involves a judgmental process of estimating total sales and costs for each contract resulting in the development of estimated cost of sales percentages. Changes in estimated revenues, cost of sales and the related effect on operating income are recognized using a cumulative catch-up adjustment which recognizes in the current period the cumulative effect of the changes on current and prior periods based on a contract’s percent complete. For the six and three months ended June 30, 2012, net favorable cumulative catch-up adjustments, including reach-forward losses, across all BDS contracts increased operating earnings by $234 million and $122 million and earnings per share by $0.20 and $0.11. For the six and three months ended June 30, 2011, net favorable cumulative catch-up adjustments, including reach-forward losses, increased operating earnings by $153 million and $100 million and earnings per share by $0.14 and $0.09.

2.1.2 From Google Inc. 6/30/2013 10-Q filed on 7/25/13

The preparation of consolidated financial statements in conformity with GAAP requires us to make estimates and assumptions that affect the amounts reported and disclosed in the financial statements and the accompanying notes. Actual results could differ materially from these estimates. On an ongoing basis, we evaluate our estimates, including those related to the accounts receivable and sales allowances, fair values of financial instruments, intangible assets and goodwill, useful lives of intangible assets and property and equipment, fair values of stock-based awards, inventory valuations, income taxes, and contingent liabilities, among others. We base our estimates on historical experience and on various other assumptions that are believed to be reasonable, the results of which form the basis for making judgments about the carrying values of assets and liabilities.

In the second quarter of 2013, we revised the estimated useful lives of certain types of property and equipment which resulted in an additional depreciation expense of $121 million during the three months ended June 30, 2013.

2.1.3 From Zale Corp 10/31/11 10-Q filed on 12/8/11

We offer our Fine Jewelry customers lifetime warranties on certain products that cover sizing and breakage with an option to purchase theft protection for a two-year period. ASC 605–20, Revenue Recognition-Services, requires recognition of warranty revenue on a straight-line basis until sufficient cost history exists. Once sufficient cost history is obtained, revenue is required to be recognized in proportion to when costs are expected to be incurred. The Company has historically recognized revenue from lifetime warranties on a straight-line basis over a five-year period because sufficient evidence of the pattern of costs incurred was not available. During the first quarter of fiscal year 2012, we began recognizing revenue related to lifetime warranty sales in proportion to when the expected costs will be incurred, which we estimate will be over an eight-year period. The deferred revenue balance as of July 31, 2011 related to lifetime warranties will be recognized prospectively, in proportion to the remaining estimated warranty costs. The change in estimate related to the pattern of revenue recognition and the life of the warranties is the result of accumulating additional historical evidence over the five-year period that we have been selling the lifetime warranties. The change in estimate increased revenues by $6.3 million during the first quarter of fiscal year 2012. In addition, net loss and net loss per share improved by $5.9 million and $0.18 per share during the first quarter of fiscal year 2012.

Appendix 3

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Albrecht, A., Glendening, M., Kim, K. et al. Material changes in accounting estimates and the usefulness of earnings. Rev Account Stud (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-023-09759-8

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-023-09759-8