Abstract

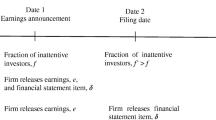

We provide new evidence on the disclosure in earnings announcements of financial statement line items prepared under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). First, we investigate the circumstances that might provide disincentives generally for GAAP line item disclosures. We find that managers who regularly intervene in the earnings reporting process limit disclosures at the aggregate level and in each of the financial statements so as to more effectively guide investor attention to summary financial information. Specifically, this disclosure behavior obtains when managers habitually cater to market expectations, engage in income smoothing, or use discretionary accruals to improve earnings informativeness. Second, we predict and find that the specific GAAP line items that firms choose to disclose are determined by the differential informational demands of their economic environment, consistent with incentives to facilitate investor valuation. However, these valuation-related disclosure incentives are muted when managers habitually intervene in the earnings reporting process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We use the term “intervene in the earnings reporting process” to encompass earnings as well as expectations management. We are agnostic regarding the motives behind the managerial intervention in earnings reporting. Our predictions do not depend on whether earnings management is a reflection of managerial opportunism or an indication of incentive alignment (e.g., signaling).

We build our premise on the argument that information provided in earnings press releases is more salient and leads to greater investor reaction. This notion is supported by empirical research in accounting (Louis et al. 2008; Stice 1991) and by theoretical and empirical works in behavioral finance on limited investor attention and the effect of saliency on information processing (Hirshleifer and Teoh 2003; Klibanoff et al. 1998; Huberman and Regev 2001; Ho and Michaely 1988; see Daniel et al. 2002, for a review).

For example, Corporate America’s best practice guidelines require earnings press releases to provide disclosure of the “most significant factors affecting the enterprise’s results for the period.” (http://www2.fei.org/news/FEI-NIRI-EPRGuidelines-4-26-2001.cfm).

Although earnings press releases are subject to the antifraud provisions of the federal securities laws and may not mislead or omit material information, there are no requirements for mandatory disclosure of all material line items in an earnings press release. Consequently, our predictions regarding disclosure of specific line items are not merely due to any mandatory disclosure requirements (see Heitzman et al. 2008).

Except for the balance sheet claims factor, the rest of the factors are consistent with natural aggregation suggested by financial statement analysis.

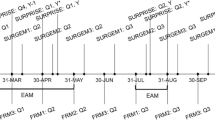

Our discussions with Standard & Poor’s indicate that only the quarterly Compustat Prelim database has truly “preliminary” data, i.e., data collected from earnings announcements released in newswires and other similar sources. In contrast, the annual Compustat Prelim database may include data from either earnings announcements or actual SEC filings and annual reports that have been preliminarily updated by Compustat under its tiered update program. Given that the focus of our paper is on disclosure in earnings announcements, we limit our analysis to the quarterly files. To check the robustness of the quarterly Prelim database, we selected a random sample of 50 firms with at least eight quarters of data (699 firm-quarters) and manually compared Compustat’s disclosure classification and coding with information disclosed in earnings press releases for each of more than 80 financial statement line items that we consider in this study. The Spearman correlation between the four disclosure ratios examined in this study calculated using the Prelim database and the corresponding “corrected” disclosure ratios based on our best efforts manual verification exceeds 0.90, indicating that measurement error is not a significant issue for in our study. Details of this manual verification are available from the authors.

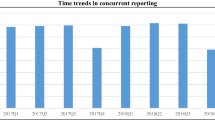

We begin the sample period in year 2000 because of Compustat’s data collection practices. First, before year 2000, Prelim data were collected by Compustat from sources based on their timeliness. For instance, Compustat may have collected data from The Wall Street Journal (which provides only limited data items) due to its timeliness even though one could subsequently obtain a more detailed press release from the company. However, with the improvement in information technology, we understand that Compustat does not rely on The Wall Street Journal except may be in exceptional circumstances. Consistent with this, we find (untabulated) that the Compustat Prelim data are almost entirely based on press releases and newswire articles rather than The Wall Street Journal during our sample period. Second, Compustat instituted a temporary policy during 1999 to limit the collection of data items from earnings announcements. This was apparently done for business reasons unrelated to corporate disclosure practices.

We exclude items related to EPS calculations for two reasons. (See items listed under Earnings per Share and Common Shares Used in Standard & Poor’s Compustat User’s Guide.) First, these disclosures are unlikely to be voluntary given that a firm has already decided to make preliminary earnings announcements. Second, the disclosure level of EPS variables exhibits limited cross-sectional and inter-temporal variations. The mean disclosure ratios for EPS items are in the range of 97–98% in all calendar quarters over the sample period. Aside from EPS data, we also exclude unique items that apply only to financial services firms. A list of the financial statement items included in the calculation of disclosure ratios is available from the authors.

While we use discretionary accruals to measure income smoothing (Tucker and Zarowin 2006), we cannot rule out the possibility that our measure is also reflecting the innate earnings properties rather than solely the effects of managerial intervention.

Earnings surprise is measured as actual earnings per share (EPS) minus average EPS forecast made by individual analysts just before earnings announcement, both based on the unadjusted I/B/E/S database. If the necessary I/B/E/S data is not available for a firm-quarter, we define earnings surprise as seasonally adjusted EPS (i.e., EPS in the current quarter minus EPS in the same quarter of prior year).

Chen et al. (2002) include continuous variables for firm age and stock return volatility but, similar to us, use dummy indicators for the other four variables.

However, Wasley and Wu (2006) argue that cash flow statement disclosures are not driven by litigation considerations. The positive association between disclosure and litigation risk may therefore not hold for cash flow statement disclosures.

First, although there is reasonable consistency across studies as to what the variables are proxying for, there are some exceptions. For instance, prior research has used book-to-market ratio to proxy for information environment (Frankel et al. 1999), proprietary costs (Bamber and Cheon 1998), and disclosure complexity (Bushee et al. 2003). By using factor analysis we, to some extent, let the data identify the relevant economic constructs. Second, factor analysis enables us to extract underlying constructs that explain discretionary disclosure rather than include several correlated variables jointly. Third, factor analysis helps eliminate measurement errors from extracted factors to the extent that the measurement errors in different proxies are uncorrelated (Kim and Mueller 1978, p. 68).

While we do not have a proxy for proprietary cost, we believe that these costs are unlikely to determine “voluntary” disclosure of line items that must be provided within a short period of time (see Chen et al. 2002, p. 233–234).

Multicollinearity does not appear to be an issue in our models. The variance inflation factors for the independent variables included in Panel A Model 1 (Panel B) of Table 3 range from 1.02 to 2.78 with a mean of 1.78 (1.06–6.08 with a mean of 2.40).

Note that Yu’s (2008) results suggest that analyst coverage dampens, but not eliminates, earnings management; firms with analyst coverage do engage in earnings management, albeit to a lesser extent. Specifically, he finds that for an increase in analyst coverage equal to its inter-quartile range, the decrease in the level of discretionary accruals is equal to 14% (26) of its sample mean (median; p. 258).

For the sake of completeness, we ran Model 2 interacting Info_increase and AvgJMOB with the IBES/NOIBES dummies. For both Info_increase and AvgJMOB, while the magnitude of the slope is larger for uncovered firms, it is not significantly different from that of the covered firms. For AvgJMOB, the insignificant result is arguably consistent with the evidence in Bartov et al. (2002) that the stock market appears to favor firms that meet or beat market expectations even when the outcome is due to earnings and/or expectations management.

The combined effect for each ratio is calculated by multiplying the inter-quartile range for each independent variable and the corresponding slope estimate, summing the products across the three variables, and dividing the aggregate sum by the mean of the disclosure ratio from Panel A of Table 2. While we discuss the marginal effects based on reported OLS regression estimates, the results based on unreported fractional response regressions are comparable.

To limit the loss of observations, we use industry median (based on the 48 Fama-French industry classifications) disclosure ratio as a substitute when a financial statement data item is missing. The tenor of the factor analysis results is unaffected if we instead use the median disclosure ratio of the corresponding financial statement for that firm-quarter as a substitute or if we exclude the firm-quarters with missing value in any financial statement item.

For example, see the following excerpts from the press release of SSA Global: “We believe EBITDA provides meaningful additional information that enables management to monitor our ability to generate cash and provides investors an understanding of cash flow performance over comparative periods. We also believe EBITDA reflects the underlying economics of our business and aligns with the operating cash flow performance of our company as measured under GAAP.” (http://regional.ssaglobal.com/home/press/press/modulepress/q12005results).

When these individual data item factors are regressed against hypothesized determinants, regression results are indistinguishable across the three, lending support to collapsing the three into one factor.

“A Clear Look at EBITDA” by Ben McClure (http://www.investopedia.com/articles/06/ebitda.asp).

Based on a review of S&P industry surveys, Francis et al. (2003) find that EBITDA is the preferred performance metric in oil and gas, healthcare, and telecommunications for security analysts. Untabulated analysis shows that EBITDA-related disclosures are most prevalent in the following industries: oil, gold, meals, telecom, mines, entertainment, transportation, healthcare, and publishing. Companies’ disclosure practices appear consistent with equity analysts’ demand.

Consistent with our constructs, we use the proportion of tangible assets to measure “capital intensity” in the IS_EBITDA regression and one minus the proportion of tangible assets to measure “asset risk” in the two balance sheet disclosure regressions.

For example, in its earnings press release dated February 3, 2004, Rigel Pharmaceuticals, Inc., a company meeting our definition of a cash-strapped development stage company, highlighted in the body of the press release the magnitude of tangible assets consisting of cash and available-for-sale securities and also provided a summary balance sheet.

Similar to the discussions in Barth et al. (2001, n. 23), this prediction is not inconsistent with the results in Dechow et al. (1998). Using data reported in Table 6 of Barth et al. (2001), we find that the incremental adjusted R-squared from their unrestricted model (where accruals components are broken down) compared with the CF and ACCRUALS model (where total accruals are included) has a Spearman correlation of −0.69 (P < 0.01) with industry-level mean operating cycle. Results are similar when their unrestricted model is compared with a model where disaggregated earnings enter as the sole variable.

OperCycle = [(average net receivables/net sales) + (average inventory/cost of goods sold) − (average accounts payable/cost of goods sold)]/360. This measure is expressed as a fraction of a year, so multiplying OperCycle by 360 gives the operating cycle in days.

Sensitivity analysis indicates that each of the three litigation proxy variables (high tech dummy, trading volume and return volatility) is significantly negatively associated with cash flow and EBITDA disclosures in a multivariate setting.

We do not estimate the economic significance for Panel A of Table 5 given that the dependent variables are standardized mean-zero factor scores. Also, we exclude Inv_Asset given its insignificance. When aggregating the economic significance of the hypothesized determinants of accrual disclosures in the cash flow statement, we consider the absolute value of the slope estimate for OperCycle.

We do not interact Inv_Asset and OCF_RD with managerial intervention groups given the former is not statistically significant in our regressions and given that the incidence of OCF_RD = 1 is less than 10% in the sample used in the Table 5 regression, respectively.

We thank the referee for suggesting this analysis. The details of this analysis are available from the authors.

Depending on I/B/E/S basic/diluted flag, we compare the actual earnings with GAAP basic (Compustat #19) or diluted (Compustat #9) EPS.

See Healy and Palepu (2001) for a broad review of the disclosure literature. In addition to these four factors, extant literature identifies disclosure complexity as another relevant factor (Frankel et al. 1999; Chen et al. 2002; Bushee et al. 2003). Given that our factor analysis does not identify a factor that loads on variables proxying for disclosure complexity, we limit our discussions to these four factors.

We used data over the longer time period to include disclosure incentives lagged up to two years and found some evidence of delayed managerial response to changed firm characteristics (unreported). Factor analysis using data over 2000 through 2003 leads to virtually identical inferences.

Prior literature also suggests that firms that engage in merger and acquisition transactions (Chen et al. 2002) or new issues (Frankel et al. 1995; Lang and Lundholm 1993; Healy et al. 1999; Clarkson et al. 1994) have incentives to provide voluntary information to reduce information asymmetry. We use indicators to capture firms that engage in these capital market transactions. However, those indicators do not load on any factors in the factor analysis, and none of their coefficients is significant at conventional levels when included in the multivariate regression analysis.

References

Adhikari, A., & Duru, A. (2006). Voluntary disclosure of free cash flow information. Accounting Horizon, 20, 311–332.

Alexander, J. C. (1991). Do the merits matter? A study of settlements in securities class actions. Stanford Law Review, 43, 497–598.

Altman, E. I. (1968). Financial ratios, discriminant analysis, and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. The Journal of Finance, 23, 589–609.

Amir, E., & Lev, B. (1996). Value-relevance of nonfinancial information: The wireless communication industry. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 22, 3–30.

Arya, A., Sunder, S., & Glover, J. C. (1998). Earnings management and the revelation principle. Review of Accounting Studies, 3, 7–34.

Bamber, L. S., & Cheon, Y. S. (1998). Discretionary management earnings forecasts: Antecedents and outcomes associated with forecast venue and forecast specificity choices. Journal of Accounting Research, 36, 167–190.

Banker, R., Huang, R., & Natarajan, R. (2006). Does SG&A expenditure create a long-lived asset? Working paper (http://aaahq.org/mas/MASPAPERS2007/cost_behavior/Banker,%20Huang%20and%20Natarajan.pdf). Temple University, Baruch College, and The University of Texas at Dallas.

Barclay, M. J., Smith, C. W., Jr., & Morellec, E. (2006). On the debt capacity of growth options. Journal of Business, 79, 37–59.

Barth, M. E., Cram, D. P., & Nelson, K. K. (2001). Accruals and the prediction of future cash flows. The Accounting Review, 76, 27–57.

Bartov, E., Givoly, D., & Hayn, C. (2002). The rewards to meeting or beating earnings expectations. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 33, 173–204.

Beidleman, C. (1973). Income smoothing: The role of management. The Accounting Review, 48, 653–667.

Berger, P. G., & Hann, R. (2007). Segment profitability and the proprietary and agency costs of disclosure. Working Paper (http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=436740). University of Chicago and University of Southern California.

Bhattacharya, N., Black, E. L., Christensen, T. E., & Larson, C. R. (2003). Assessing the relative informativeness and performance of pro forma earnings and GAAP operating earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 36, 285–319.

Botosan, C. A. (1997). Disclosure level and the cost of equity capital. The Accounting Review, 72, 323–349.

Botosan, C. A., & Harris, M. S. (2000). Motivations for a change in disclosure frequency and its consequences: An examination of voluntary quarterly segment disclosures. Journal of Accounting Research, 38, 329–353.

Botosan, C. A., & Plumlee, M. A. (2002). A re-examiniation of disclosure level and the expected cost of equity capital. Journal of Accounting Research, 40, 21–40.

Bowen, R. M., Davis, A. K., & Matsumoto, D. A. (2005). Emphasis on pro forma versus GAAP earnings in quarterly press releases: Determinants, sec intervention, and market reactions. The Accounting Review, 80, 1011–1038.

Brown, L. D., & Caylor, C. L. (2005). A temporal analysis of quarterly earnings thresholds: Propensities and valuation consequences. The Accounting Review, 80, 423–440.

Bublitz, B., & Ettredge, M. (1989). The information in discretionary outlays: Advertising, research and development. The Accounting Review, 64, 108–124.

Burgstahler, D. C., & Eames, M. (2006). Management of earnings and analysts’ forecasts to achieve zero and small positive earnings surprises. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 33, 633–652.

Bushee, B. J., Matsumoto, D. A., & Miller, G. S. (2003). Open versus closed conference calls: The determinants and effects of broadening access to disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 34, 149–180.

Bushee, B. J., & Noe, C. F. (2000). Corporate disclosure practices, institutional investors, and stock return volatility. Journal of Accounting Research, 38(Supplement), 171–202.

Bushman, R. M., Piotroski, J. D., & Smith, A. J. (2004). What determines corporate transparency? Journal of Accounting Research, 42, 207–252.

Cattell, R. B., & Vogelman, S. (1977). A comprehensive trial of the Scree and KG criteria for determining the number of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 12, 289–325.

Chen, S., DeFond, M. L., & Park, C. W. (2002). Voluntary disclosure of balance sheet information in quarterly earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 33, 229–251.

Clarkson, P. M., Kao, J. L., & Richardson, G. D. (1994). The voluntary inclusion of forecasts in the MD&A section of annual reports. Contemporary Accounting Research, 11, 423–450.

Collins, D. W., & Hribar, P. (2002). Errors in estimating accruals: Implications for empirical research. Journal of Accounting Research, 40, 105–134.

Collins, D. W., Maydew, E. L., & Weiss, I. S. (1997). Changes in the value relevance of earnings and book values over the past forty years. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 24, 39–67.

Cotter, J., Tuna, I., & Wysocki, P. D. (2006). Expectations management and beatable targets: How do analysts react to explicit earnings guidance? Contemporary Accounting Research, 23, 593–624.

Daniel, K., Hirshleifer, D., & Teoh, S. H. (2002). Investor psychology in capital markets: Evidence and policy implications. Journal of Monetary Economics, 49, 139–209.

Dechow, P. M. (1994). Accounting earnings and cash flows as measures of firm performance: The role of accounting accruals. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 18, 3–42.

Dechow, P. M., Kothari, S. P., & Watts, R. L. (1998). The relation between earnings and cash flows. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 25, 133–168.

DeFond, M. L., & Hung, M. (2003). An empirical analysis of analysts’ cash flow forecasts. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 35, 73–100.

DeFond, M. L., & Park, C. W. (1997). Smoothing income in anticipation of future earnings. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 23, 115–139.

Degeorge, F., Patel, J., & Zeckhauser, R. (1999). Earnings management to exceed thresholds. Journal of Business, 72, 1–33.

Demski, J. S. (1998). Performance measure manipulation. Contemporary Accounting Research, 15, 261–285.

Diamond, D. W. (1985). Optimal release of information by firms. Journal of Finance, 40, 1071–1094.

Doyle, J. T., Lundholm, R. J., & Soliman, M. T. (2003). The predicted value of expenses excluded from pro forma earnings. Review of Accounting Studies, 8, 145–174.

Doyle, J. T., & Soliman, M. T. (2002). Do managers use pro forma earnings to exceed analyst forecasts? Working Paper (http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=328940). Utah State University and University of Washington.

Dye, R. (1985). Disclosure of nonproprietary information. Journal of Accounting Research, 23, 123–145.

Dye, R. (2001). Commentary on essays on disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 32, 181–235.

Field, L., Lowry, M., & Shu, S. (2005). Does disclosure deter or trigger litigation? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39, 487–507.

Francis, J., LaFond, R., Olsson, P. M., & Schipper, K. (2004). Cost of equity and earnings attributes. The Accounting Review, 79, 967–1010.

Francis, J., Philbrick, D., & Schipper, K. (1994). Shareholder litigation and corporate disclosures. Journal of Accounting Research, 32, 137–164.

Francis, J., & Schipper, K. (1999). Have financial statements lost their relevance? Journal of Accounting Research, 37, 319–352.

Francis, J., Schipper, K., & Vincent, L. (2002). Expanded disclosures and the increased usefulness of earnings announcement. The Accounting Review, 77, 515–546.

Francis, J., Schipper, K., & Vincent, L. (2003). The relative and incremental explanatory power of earnings and alternative (to earnings) performance measures for returns. Contemporary Accounting Research, 20, 121–164.

Frankel, R., Johnson, M., & Skinner, D. (1999). An Empirical examination of conference calls as a voluntary disclosure medium. Journal of Accounting Research, 37, 133–150.

Frankel, R., McNichols, M., & Wilson, P. (1995). Discretionary disclosure and external financing. The Accounting Review, 70, 133–150.

Fudenberg, K., & Tirole, J. (1995). A theory of income and dividend smoothing based on incumbency rents. Journal of Political Economy, 103, 75–93.

Gelb, D. (2002). Intangible assets and firms’ disclosures: An empirical investigation. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 29, 457–476.

Gradient Analytics, Inc. (2005). Earnings quality analytics: The earnings quality factor model. White paper. http://www.gradientanalytics.com/whitepapers/QuantitativeAnalysis.pdf.

Graham, J. R., Harvey, C. R., & Rajgopal, S. (2005). The economic implications of corporate financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 40, 3–73.

Hayn, C. (1995). The information content of losses. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 20, 125–153.

Healy, P. (1985). The effect of bonus schemes on accounting decisions. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 7, 85–107.

Healy, P. M., Hutton, A. P., & Palepu, K. G. (1999). Stock performance and intermediation changes surrounding sustained increases in disclosure. Contemporary Accounting Research, 16, 485–520.

Healy, P. M., & Palepu, K. G. (2001). Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 31, 405–440.

Heitzman, S., Wasley, C. E., & Zimmerman, J. L. (2008). The joint effects of materiality thresholds and voluntary disclosure incentives on firms’ disclosure decisions. Working paper (http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1069382). University of Rochester.

Hirschey, M. (1982). Intangible capital aspects of advertising and R&D expenditures. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 30, 375–389.

Hirshleifer, D., Lim, S. S., & Teoh, S. H. (2007). Driven to distraction: Extraneous events and underreaction to earnings news. Working paper (http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=980958). University of California at Irvine and DePaul University.

Hirshleifer, D., & Teoh, S. H. (2003). Limited attention, information disclosure, and financial reporting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 36, 337–386.

Ho, T., & Michaely, R. (1988). Information quality and market efficiency. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 23, 53–70.

Hoskin, R. E., Hughes, J. S., & Ricks, W. E. (1986). Evidence on the incremental information content of additional firm disclosures made concurrently with earnings. Journal of Accounting Research, 24(Supplement), 1–32.

Huberman, G., & Regev, T. (2001). Contagious speculation and a cure for Cancer: A nonevent that made stock prices soar. Journal of Finance, 56, 387–396.

Johnson, M. F., Kasznik, R., & Nelson, K. K. (2001). The impact of securities litigation reform on the disclosure of forward-looking information by high technology firms. Journal of Accounting Research, 39, 297–327.

Joos, P., & Plesko, G. A. (2005). Valuing loss firms. The Accounting Review, 80, 847–870.

Jung, W., & Kwon, Y. K. (1988). Disclosure when the market is unsure of information endowment of managers. Journal of Accounting Research, 26, 146–153.

Kasznik, R., & Lev, B. (1995). To warn or not to warn: Management disclosures in the face of an earnings surprise. The Accounting Review, 70, 113–134.

Kim, J., & Mueller, C. W. (1978). Introduction to factor analysis: What it is and how to do it. Sage: University Paper Series on Quantitative Applications in the Social Sciences.

Kim, O., & Verrecchia, R. E. (2001). The relation among disclosure, returns, and trading volume information. The Accounting Review, 76, 633–654.

Kirschenheiter, M., & Melumad, N. D. (2002). Can “big bath” and earnings smoothing co-exist as equilibrium financial reporting strategies? Journal of Accounting Research, 40, 761–796.

Klibanoff, P., Lamont, O., & Wizman, T. A. (1998). Investor reaction to salient news in closed-end country funds. Journal of Finance, 53, 673–699.

Kothari, S. P., Shu, S., & Wysocki, P. (2008). Do managers withhold bad news? Working Paper (http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=803865). MIT Sloan School of Management.

Lang, M., & Lundholm, R. (1993). Cross-sectional determinants of analyst ratings of corporate disclosures. Journal of Accounting Research, 31, 246–271.

Lev, B., & Sougiannis, T. (1996). The capitalization, amortization, and value-relevance of R&D. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 21, 107–138.

Lougee, B. A., & Marquardt, C. A. (2004). Earnings informativeness and strategic disclosure: An empirical examination of “pro forma” earnings. The Accounting Review, 79, 769–795.

Louis, H., Robinson, D., & Sbaraglia, A. (2008). An integrated analysis of the association between accrual disclosure and the abnormal accrual anomaly. Review of Accounting Studies, 13, 23–54.

Papke, L. E., & Wooldridge, J. M. (1996). Econometric methods for fractional response variables with an application to 401(K) plan participation rates. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 11, 619–632.

Pastena, V., & Ronen, J. (1979). Some hypotheses on the pattern of management’s informal disclosures. Journal of Accounting Research, 17, 550–564.

Sankar, M., & Subramanyam, K. (2001). Reporting discretion and private information communication through earnings. Journal of Accounting Research, 39, 367–392.

Scott, T. W. (1994). Incentives and disincentives for financial disclosure: Voluntary disclosure of defined benefit pension plan information by Canadian firms. The Accounting Review, 69, 26–43.

Skinner, D. J. (1994). Why Firms voluntarily disclose bad news. Journal of Accounting Research, 32, 38–60.

Skinner, D. J. (1997). Earnings disclosures and stockholder lawsuits. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 23, 249–282.

Soffer, L. E., Thiagarajan, S. R., & Walther, B. R. (2000). Earnings preannouncement strategies. Review of Accounting Studies, 5, 5–26.

Stice, E. (1991). The market reaction to 10-K and 10-Q filings and to subsequent The Wall Street Journal earnings announcements. The Accounting Review, 66, 42–55.

Suozzo, P., Cooper, S., Sutherland, G., & Deng, Z. (2001). Valuation multiples: A primer. UBS Warburg: Valuation and Accounting (November).

Tucker, J. W., & Zarowin, P. A. (2006). Does income smoothing improve earnings informativeness? The Accounting Review, 81, 251–270.

Verrecchia, R. E. (1983). Discretionary disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 5, 179–194.

Verricchia, R. E. (2001). Essays on disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 32, 97–180.

Wasley, C. E., & Wu, J. S. (2006). Why do managers voluntarily issue cash flow forecasts? Journal of Accounting Research, 44, 389–429.

You, H., & Zhang, X. (2007). Investor under-reaction to earnings announcement and 10-K report. Working paper (http://www4.gsb.columbia.edu/null/download?&exclusive=filemgr.download&file_id=16535). Barclays Global Investors and University of California, Berkeley.

Yu, F. (2008). Analyst coverage and earnings management. Journal of Financial Economics, 88, 245–271.

Acknowledgments

The partial sponsorship of the research by Analysis Group, Inc. is gratefully acknowledged. The authors acknowledge the extensive discussions with and the inputs received from Gary Barwick, Don Barsody, Joe Kannikal, and Debbie Puetz of Standard and Poor’s. We are especially grateful to Shuping Chen (discussant, 2007 FARS Meeting) for her extensive and thoughtful comments and suggestions. We also acknowledge inputs from an anonymous reviewer, Daniel Beneish, Leslie Hodder, Ben Lansford (discussant, 2006 AAA Annual Meeting), April Klein, Inder Khurana, S. P. Kothari, Edward Xuejun Li, Russ Lundholm (the editor), Joshua Livnat, Ajay Maindiratta, Raynolde Pereira, Kathy Petroni, Joshua Ronen, Stephen Ryan, Isabel Wang, Jeff Wooldridge, Paul Zarowin, and Jerry Zimmerman, and the workshop participants at Indiana University, New York University, Texas Christian University, and the University of Missouri at Columbia. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of I/B/E/S International Inc. for providing analyst forecast data. Part of the research was completed when K. Ramesh was an academic fellow at the Securities and Exchange Commission, which, as a matter of policy, disclaims responsibility for any private publication or statements by any of its employees or contractors. The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the commission or its staff.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Discussion of disclosure incentive proxies based on extant literature

1.1.1 Disclosure incentive predictions based on extant literature

Without providing a detailed literature review, we briefly summarize the main predictions from this extensive literature, which has considered different cost-benefit trade-offs firms face in choosing whether to disclose, when, and how much. Based on our review, we identify the following four economic constructs that are commonly cited as motivating disclosure decisions:Footnote 34

-

1.

Information Environment,

-

2.

Litigation Costs,

-

3.

Proprietary Costs,

-

4.

Bad News.

With respect to information environment, prior research suggests that firms’ discretionary disclosures in earnings announcements should increase with the expected benefits of reducing information risk (Healy and Palepu 2001; Lang and Lundholm 1993; Verricchia 2001; Botosan 1997; Botosan and Plumlee 2002; Graham et al. 2005; Frankel et al. 1999; Chen et al. 2002) or the expected reduction in private information search costs (Bushee et al. 2003; Diamond 1985; Scott 1994; Graham et al. 2005). Similarly, the extent of discretionary disclosures in earnings announcements is likely to be positively associated with litigation risk (Bushee et al. 2003; Botosan and Harris 2000; Chen et al. 2002; Kasznik and Lev 1995; Johnson et al. 2001; Field et al. 2005), but this association may not hold for cash flow statement disclosures (Wasley and Wu 2006). While extant literature generally suggests that proprietary costs will lead to curtailed disclosures (Verrecchia 1983, 2001; Dye 2001; Scott 1994; Clarkson et al. 1994; Graham et al. 2005), Chen et al. (2002) aptly suggest that proprietary cost considerations are unlikely to limit voluntary disclosure of information that are required to be disclosed shortly thereafter.

The analytical models in Dye (1985) and Jung and Kwon (1988) suggest that when there is uncertainty about firms’ information endowment, investors cannot differentiate firms’ withholding of bad news from the nonexistence of information, leading to fewer disclosures. In contrast, there is mixed evidence in the extant literature on the incentives for timely disclosure of bad news (Pastena and Ronen 1979; Kothari et al. 2008; Skinner 1994; Soffer et al. 2000). However, our analysis is focused on the disclosure of other financial information conditional on the decision to disclose the preliminary earnings information. The empirical evidence in Chen et al. (2002) suggests that firms disclosing bad earnings news may provide other financial information given that earnings by themselves may be a poor indicator of future cash flows and firm value (Hayn 1995; Collins et al. 1997). This leads us to predict a positive association between bad news and the discretionary disclosure of financial information in earnings announcements.

1.1.2 Measurement of disclosure incentive factors

We use factor analysis to reduce the dimensionality of the 16 variables used in past research as proxies for the disclosure incentives discussed above. A list of references is available from the authors. To allow for lagged values of disclosure incentives in our sensitivity analysis, we conduct the factor analysis on observations in calendar years 1998 through 2003.Footnote 35 Three factors are retained based on the Scree test as well as on the proportion of variance accounted for by the retained factors (Cattell and Vogelman 1977). We choose oblique rotation because it allows extracted factors to be correlated, which is intuitively appealing in the given context. For example, one would expect a correlation between bad news and litigation risk.

Together the three factors explain about 38% of the total variation in the original 16 variables. We present the factor loadings in Table 7. We label the first factor “Information Environment” (IE). Consistent with prior studies, this factor loads positively on firm size, coverage on I/B/E/S, number of analyst following, number of shareholders, and the percentage of institutional ownership, all of which are likely to be correlated with information risk or private information search costs.

We label the second factor “Litigation Costs” (LC). LC is positively correlated with high technology industry membership, typically considered a proxy for litigation costs. It is also positively correlated with trading volume, considered in some past research to be a proxy for litigation risk (Kasznik and Lev 1995; Johnson et al. 2001). See Bushee and Noe (2000) and Bushee et al. (2003) for a different perspective. A significant portion of shareholder damages in securities litigation is typically due to the trading volume during the class period (Kasznik and Lev 1995). LC is also positively related to return volatility. Alexander (1991) argues that large share price fluctuations may themselves be associated with the incidence of lawsuits. Damages in securities litigation are also generally based on share price changes (Lang and Lundholm 1993). The positive loading on return volatility suggests that vulnerability to litigation increases with return volatility. Finally, LC loads with a negative sign on the industry concentration ratio, which has generally been viewed in past literature as a proxy for proprietary costs (see Berger and Hann 2007 for a different perspective). Since most of the variation (81%) in LC is provided by trading volume, high tech industry membership, and stock return volatility, we view this factor as predominantly measuring litigation costs (untabulated analysis).

After flipping the signs on the factor loadings, we label the third factor “Bad News” (BN). As shown in Table 7, BN is positively correlated with whether a firm reports an earnings decrease or a loss and is negatively correlated with ROA and the ratio of operating cash flows to total assets (Cash Flow). Lang and Lundholm (1993) distinguish between period-specific “performance” variables (e.g., rate of return) and relatively stable structural variables (e.g., variability in the rate of return). The variables that load on the BN factor are more likely to belong to the former category and to represent period-specific bad news, although one could argue that ROA and Cash Flow are more reflective of long-run profitability (which Frankel et al. 1999 find to be positively associated with disclosure) than of period-specific news. However, earnings decreases and the existence of losses by themselves explain most of the variation in the BN factor (74%), reinforcing the belief that BN largely captures period-specific information (untabulated analysis).

Overall, the factor analysis identifies proxies for three, and possibly all four, of the incentives for discretionary disclosure discussed in prior research.Footnote 36

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

D’Souza, J., Ramesh, K. & Shen, M. Disclosure of GAAP line items in earnings announcements. Rev Account Stud 15, 179–219 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-009-9100-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-009-9100-0