Abstract

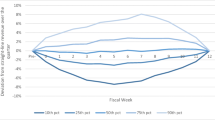

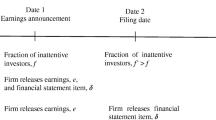

Using data from Taiwan, where listed firms are required to disclose monthly revenues, this paper examines the information value of mandatory interim revenue disclosures. We find that monthly revenue surprises have a significant effect on analysts’ earnings forecasts, suggesting that analysts incorporate such information into their earnings forecasts once the information is available. In addition, monthly revenue surprises significantly predict future earnings surprises, and their predictive power goes beyond the information provided by analysts’ earnings forecasts, suggesting that monthly revenue surprises provide leading information about future earnings growth but analysts do not fully reflect this information. Stock prices drift positively with monthly revenue surprises during the period prior to the quarterly earnings announcement. However, when quarterly earnings are finally announced, stock prices are no longer driven by monthly revenue surprises, suggesting that monthly revenue surprises have been fully incorporated into the stock prices. Overall, our results suggest that interim accounting information helps investors increase the speed of adjustments to fundamental news.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

According to Article 36 of the Securities Exchange Act of Taiwan, since 1988 Taiwan’s listed firms are required to disclose unaudited net operating revenues of the preceding month within the first ten days of each month. Please see Sect. 2.1 for a detailed introduction of the accounting disclosure regulation in Taiwan.

As will be shown later in Table 2, the first autocorrelation of SUE (0.27) is lower than and only half those of SURGEQ (0.51) or SURGEM (0.52). The information provided by monthly revenue surprises thus contains the information about the persistence of earnings growth and thus could herald future earnings growth (proxied by SUE). It is possible that monthly revenue surprises and SUE are not correlated if monthly revenue surprises are negatively autocorrelated or short-lived, and if a company’s expenses change dramatically. However, this is not a typical case in our study. On the other hand, if we observe that three monthly revenue surprises are persistent, it is more likely the earnings surprises would be persistent since past earnings surprises are less likely to be driven by expense reduction.

According to the security market statistics of the Taiwan Stock Exchange Corporation (https://www.twse.com.tw/en/statistics/), more than 90% of trading in the 1990s was carried out by individual investors. This percentage gradually decreased. In 2015, about 60% of trading was made by individual investors.

Please refer to Proposal 3117–1, Agenda Related Documents 727, Legislative Yuan of the Republic of China, 1987, in https://db.lawbank.com.tw/FLAW/GetRFile.ashx?LEID=35597&T=2.

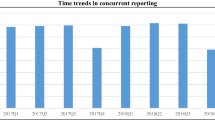

Taiwan’s listed firms were initially only required to announce their reports semiannually. Mandatory quarterly financial reporting was implemented after 1988 by the Securities and Exchange Commission in Taiwan. During the period of TW GAAP, the quarterly reports must be filed before 30 April, 31 August, 31 October for the first three quarters, and before 31 March of the following year for the fourth quarter. Following the adoption of the IFRS, the schedule for public firms to release quarterly financial reports was changed. The deadlines for the first three fiscal quarters became 15 May, 14 August, and 14 November, and the deadline for the fourth quarter became 31 March of the following year.

In addition, since the adoption of IFRS, firms only report monthly consolidated revenues and no longer provide monthly individual parent company revenues.

The announcement dates are regulated by Article 36 of the Securities Exchange Act in Taiwan.

For example, Ertimur et al. (2003) and Jegadeesh and Livnat (2006a, b) examine the stock market responses to revenue surprises on earnings-announcement dates through controlling for earnings surprises of the same quarter in the regression. In their context, revenue surprises serve as a complemental role in addition to concurrent earnings surprises.

However, using a panel of US retail firms from 1993 to 2001, Van Buskirk (2012) find that providing frequent disclosures (monthly revenues) is not associated with reduced information asymmetry.

For example, Easterwood and Nutt (1999) show that analysts tend to overreact to good prior earnings news but underreact to bad news.

They show that it takes up to 5 months for analysts to fully incorporate the information contained in quarterly revenue surprises into their earnings forecasts. In addition, the full revision should be more than double the analysts’ initial revisions.

McNichols and Manegold (1983) provide similar results in the context of quarterly earnings disclosures. They examine the extent to which quarterly reports preempt the news in the annual report, and find that return variability is lower during annual report announcement in the “annual-plus-quarterly-reports” environments.

We also use the IBES earnings estimate database for a robustness check. IBES covers international data back to 1987, but the coverage for Taiwan stocks is far less than that in the CMoney database during our sample period. The results based on IBES earnings estimate data are qualitatively similar and we report the results in Appendix Tables 13 and 14.

At the end of 2015, the exchange rate was US$1 = NT$32.88.

Stocks with a nominal price less than 10 face more short-sell limits, according to trading protocol on the Taiwan stock market, and thus are more likely to be illiquid and/or mispriced.

We exclude firms if their TW SIC codes are 14 (Construction sector) or 17 (Financial sector).

For example, construction firms are required to use the completed contract method in IFRS, which recognizes revenues and profits only when projects are completed.

We deleted firms covered by fewer than two analysts because the information quality of earnings forecast from only one analyst is a concern. However, we conduct the robustness test of including those firms covered by only one analyst and we find that our results are robust. We report the results in Appendix Tables 15 and 16.

The TW SIC codes are retrieved from TEJ Company Attribute Database Module item #05 (TSEC Sector). TEJ integrates the industry codes from Taiwan Stock Exchange (TWSE) and the Gre Tai Securities Market (GTSM). There are 29 industries in our sample after excluding financial and construction industries.

In Panel C of Table 1, the only company in the Glass and ceramic industry is Taiwan Glass Ind. Corporation. The only company in the Agricultural science and technology industry is Huikwang Corporation.

For a robustness check, we also use a seasonal random walk without a drift to estimate the revenue expectation. Revenue surprise estimated from this historical time-series model is simply the year-on-year revenue growth (denoted as RevYoY). Seasonal random walk without a drift is commonly used by practitioners and by academics, such as Kasznik and Lev (1995) and Ayers et al. (2011), and is also likely to capture market expectation.

To estimate a drift term \({v}_{i,m}\), we first calculate the year-over-year difference of revenue per share and then average it over the past 24 observations. To calculate the 24 observations of the year-over-year difference of revenue per share based on a rolling window, we need additional 12 observations of preceding monthly revenues. Hence, we require a total of 36 preceding firm-month revenue observations to estimate a monthly revenue surprise (SURGEM) for a firm. If a firm does not have 36 firm-month observations (in calculating 24 observations of preceding year-over-year difference of revenue per share), we require at least 21 firm-month observations (in calculating 9 observations of preceding year-over-year difference of revenue per share) to estimate a SURGEM; otherwise, we assign a missing value for the variable.

To estimate a drift term \({\varrho }_{i,t}\), we first calculate the year-over-year difference of EPS and then average it over the past 8 observations. To calculate the 8 observations of the year-over-year difference of EPS based on a rolling window, we need additional 4 observations of preceding quarterly earnings. Hence, we require a total of 12 preceding firm-quarter earnings observations to estimate a quarterly SUE for a firm. If a firm does not have 12 firm-quarter observations (in calculating 8 observations of preceding year-over-year difference of EPS), we require at least 7 firm-quarter observations (in calculating 3 observations of preceding year-over-year difference of EPS) to estimate a SUE; otherwise, we assign a missing value for the variable.

We also estimate the SURGEQ directly from the time series of quarterly revenues as the estimation of SUE. The correlation between SURGEQ estimated by the sum of three SURGEMs and SURGEQ estimated directly from the time series of quarterly revenues is significantly high at 0.86. The results employing SURGEQ from these two estimations are qualitatively similar.

TURN is the monthly trading volume divided by outstanding shares, multiplied by 100.

We thank an anonymous referee for suggesting that we use this empirical design to exclude the possible effects of quarterly earnings announcements.

According to the dates of earnings announcements mentioned in Sect. 2.1, prior to 2013, earnings-announcement months were March, April, May, August, September, October, and November. However, after 2013, September and October were removed from the list.

For example, Hodgdon et al. (2008) show that compliance with the disclosure requirements of IFRS reduces information asymmetry and enhances the ability of financial analysts to provide more accurate forecasts. Byard et al. (2011) highlight the role of enforcement regimes and firm-level reporting incentives in determining the impact of mandatory IFRS adoption. Tan et al. (2011) find that mandatory IFRS adoption improves foreign analysts’ forecast accuracy. We thank an anonymous referee for this helpful suggestion.

In unreported results, we also exclude the sample during the transitional period (2012–2013) and rerun the regression. The results are qualitatively similar.

We also use the analyst earnings forecasts from I/B/E/S as a robustness test. As shown in Appendix Table 13, the results regarding the effect of SURGEM on the forecast revision during non-earnings-announcement months are robust to the I/B/E/S data.

We also conduct a robustness test that includes those firms covered by only one analyst. The results are qualitatively similar. Please refer to Appendix Table 15.

In the unreported results, we also exclude the transitional period (2012–2013) and rerun the regression. The results are qualitatively similar.

We also conduct a robustness test that includes those firms covered by only one analyst, the results are qualitatively similar. Please refer to Appendix Table 16.

We choose the trading day window (\(\tau + 3, \tau + 20 \)), meaning that it does not cover the next monthly revenue disclosure. We also test a shorter window (\(\tau + 3, \tau + 12\)) and the results are qualitatively similar.

We calculate the cumulative abnormal return as the raw return minus the return on the value-weighted size and price-to-book ratio matched portfolio benchmark. We form the six matched portfolios by the intersection of the two size and three price-to-book groups at the end of month m–1, as in Jegadeesh and Livnat (2006a, b). Among these six portfolios, the portfolio to which a stock belongs is the benchmark for that stock.

This empirical design excludes earnings-announcement months from the regression and thus excludes any possible effects from earnings surprises, which may contaminate the effect of revenue surprises. We thank an anonymous referee for this helpful suggestion.

As mentioned in Eq. (10), to isolate the marginal effects of revenue surprises, we use the residual of regressing SURGEM2 on SURGEM1, denoted as \({SURGEM2}_{i,t}^{\perp}\), and the residual of regressing SURGEM3 on SURGEM2 and SURGEM1, denoted as \({SURGEM3}_{i,t}^{\perp}\), as the explanatory variables.

Since these regressions are based on quarterly observations, we aggregate monthly SURGEMs and forecast revisions into quarterly data, SURGEQ and FRQ respectively. Please see Sect. 3.2 for the details of construction of SURGEM and the forecast revision on a quarterly basis.

References

Abarbanell JS, Bernard VL (1992) Tests of analysts’ overreaction/underreaction to earnings information as an explanation for anomalous stock price behavior. J Finance 47:1181–1207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1992.tb04010.x

Agarwal S, Qian W, Zou X (2021) Disaggregated sales and stock returns. Manage Sci Forthcoming. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2020.3813

Ali A, Chen TY, Radhakrishnan S (2007) Corporate disclosures by family firms. J Account Econ 44:238–286. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2007.01.006

Arif S, De George ET (2020) The dark side of low financial reporting frequency: Investors’ reliance on alternative sources of earnings news and excessive information spillovers. Account Rev 95:23–49. https://doi.org/10.2308/tar-2017-0018

Ayers BC, Li OZ, Yeung PE (2011) Investor trading and the post-earnings-announcement drift. Account Rev 86:385–416. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.00000027

Ball R, Brown P (1968) An empirical evaluation of accounting income numbers. J Account Res 6:159–178. https://doi.org/10.2307/2490232

Barber BM, Lee YT, Liu YJ, Odean T (2009) Just how much do individual investors lose by trading? Rev Financ Stud 22:609–632. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhn046

Beaver WH (1968) The information content of annual earnings announcements. J Account Res 6:67–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/2490070

Beaver WH, McNichols MF, Wang ZZ (2018) The information content of earnings announcements: new insights from intertemporal and cross-sectional behavior. Rev Account Stud 23:95–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-017-9417-z

Bilinski P, Eames M (2019) Analyst revenue forecast reporting and the quality of revenues and expenses. J Bus Financ Account 46:136–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbfa.12355

Botosan CA, Plumlee MA (2002) A re-examination of disclosure level and the expected cost of equity capital. J Account Res 40:21–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.00037

Butler M, Kraft A, Weiss IS (2007) The effect of reporting frequency on the timeliness of earnings: The cases of voluntary and mandatory interim reports. J Account Econ 43:181–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2007.02.001

Byard D, Li Y, Yu Y (2011) The effect of mandatory IFRS adoption on financial analysts’ information environment. J Account Res 49:69–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2010.00390.x

Chandra U, Ro BT (2008) The role of revenue in firm valuation. Account Horizons 22:199–222. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch.2008.22.2.199

Chen H-Y, Chen S-S, Hsin C-W, Lee C-F (2014) Does revenue momentum drive or ride earnings or price momentum? J Bank Financ 38:166–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.09.021

Claessens S, Djankov S, Fan JPH, Lang LHP (2002) Disentangling the incentive and entrenchment effects of large shareholdings. J Finance 57:2741–2771. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6261.00511

Cuijpers R, Peek E (2010) Reporting frequency, information precision and private information acquisition. J Bus Financ Account 37:27–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5957.2009.02180.x

Downar B, Ernstberger J, Link B (2018) The monitoring effect of more frequent disclosure. Contemp Account Res 35:2058–2081. https://doi.org/10.1111/1911-3846.12386

Easterwood JC, Nutt SR (1999) Inefficiency in analysts’ earnings forecasts: systematic misreaction or systematic optimism? J Finance 54:1777–1797. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00166

Edmonds CT, Leece RD, Maher JJ (2013) CEO bonus compensation: The effects of missing analysts’ revenue forecasts. Rev Quant Financ Account 41:149–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-012-0305-0

Elgers PT, Lo MH (1994) Reductions in analysts’ annual earnings forecast errors using information in prior earnings and security returns. J Account Res 32:290–303. https://doi.org/10.2307/2491287

Ernstberger J, Link B, Stich M, Vogler O (2017) The real effects of mandatory quarterly reporting. Account Rev 92:33–60. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-51705

Ertimur Y, Livnat J, Martikainen M (2003) Differential market reactions to revenue and expense surprises. Rev Account Stud 8:185–211. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024409311267

Fan JPH, Wong TJ (2002) Corporate ownership structure and the informativeness of accounting earnings in East Asia. J Account Econ 33:401–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-4101(02)00047-2

Froot K, Kang N, Ozik G, Sadka R (2017) What do measures of real-time corporate sales say about earnings surprises and post-announcement returns? J Financ Econ 125:143–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JFINECO.2017.04.008

Fu R, Kraft A, Zhang H (2012) Financial reporting frequency, information asymmetry, and the cost of equity. J Account Econ 54:132–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2012.07.003

Ghosh A, Gu Z, Jain P (2005) Sustained earnings and revenue growth, earnings quality, and earnings response coefficients. Rev Account Stud 10:33–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-004-6339-3

Gigler F, Kanodia C, Sapra H, Venugopalan R (2014) How frequent financial reporting can cause managerial short-termism: An analysis of the costs and benefits of increasing reporting frequency. J Account Res 52:357–387. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12043

Hodgdon C, Tondkar RH, Harless DW, Adhikari A (2008) Compliance with IFRS disclosure requirements and individual analysts’ forecast errors. J Int Account Audit Tax 17:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intaccaudtax.2008.01.002

Ivković Z, Jegadeesh N (2004) The timing and value of forecast and recommendation revisions. J Financ Econ 73:433–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2004.03.002

Jegadeesh N, Livnat J (2006a) Post-earnings-announcement drift: The role of revenue surprises. Financ Anal J 62:22–34. https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v62.n2.4081

Jegadeesh N, Livnat J (2006b) Revenue surprises and stock returns. J Account Econ 41:147–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2005.10.003

Kajüter P, Klassmann F, Nienhaus M (2019) The effect of mandatory quarterly reporting on firm value. Account Rev 94:251–277. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-52212

Kama I (2009) On the market reaction to revenue and earnings surprises. J Bus Financ Account 36:31–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5957.2008.02121.x

Kasznik R, Lev B (1995) To warn or not to warn: Management disclosures in the face of an earnings surprise. Account Rev 70:113–134

Keung EC (2010) Do supplementary sales forecasts increase the credibility of financial analysts’ earnings forecasts? Account Rev 85:2047–2074. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2010.85.6.2047

Kim O, Lim SC, Park T (2009) Measuring the impact of sales on earnings and equity price. Rev Quant Financ Account 32:145–168. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-008-0086-7

Kothari SP (2001) Capital markets research in accounting. J Account Econ 31:105–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-4101(01)00030-1

Kraft AG, Vashishtha R, Venkatachalam M (2018) Frequent financial reporting and managerial myopia. Account Rev 93:249–275. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-51838

Lang MH, Lundholm RJ (1996) Corporate disclosure policy and analyst behavior. Account Rev 71:467–492

Lin AY, Swanson PE (2010) Contrarian strategies and investor overreaction under price limits. J Econ Finance 34:430–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-009-9075-5

Lorenz T, Homburg C (2018) Determinants of analysts’ revenue forecast accuracy. Rev Quant Financ Account 51:389–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-017-0675-4

McNichols M, Manegold JG (1983) The effect of the information environment on the relationship between financial disclosure and security price variability. J Account Econ 5:49–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-4101(83)90005-8

Melgarejo M (2018) Beating market expectations and the pricing of firms’ probability of default. J Contemp Account Econ 14:41–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcae.2018.02.005

Mendenhall RR (2004) Arbitrage risk and post-earnings-announcement drift. J Bus 77:875–894. https://doi.org/10.1086/422627

Mensah YM, Werner RH (2008) The capital market implications of the frequency of interim financial reporting: An international analysis. Rev Quant Financ Account 31:71–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-007-0069-0

Shane P, Brous P (2001) Investor and (value line) analyst underreaction to information about future earnings: The corrective role of non-earnings-surprise information. J Account Res 39:387–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.00018

Stickel SE (1989) The timing of and incentives for annual earnings forecasts near interim earnings announcements. J Account Econ 11:275–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-4101(89)90009-8

Tan H, Wang S, Welker M (2011) Analyst following and forecast accuracy after mandated IFRS adoptions. J Account Res 49:1307–1357. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2011.00422.x

Tsao SM, Lu HT, Keung EC (2016) Voluntary monthly earnings disclosures and analyst behavior. J Bank Financ 71:37–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2016.04.010

Tsao SM, Lu HT, Keung EC (2018) Interim reporting frequency and the mispricing of accruals. Account Horiz 32:29–47. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch-52097

Van Buskirk A (2012) Disclosure frequency and information asymmetry. Rev Quant Financ Account 38:411–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-011-0237-0

Wagenhofer A (2014) Trading off costs and benefits of frequent financial reporting. J Account Res 52:389–401. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12045

Womack KL (1996) Do brokerage analysts’ recommendations have investment value? J Finance 51:137–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1996.tb05205.x

Yeh Y, Lee T, Woidtke T (2001) Family control and corporate governance: Evidence from Taiwan. Int Rev Financ 2:21–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2443.00014

Zhao R (2017) Revenue benchmark beating and the sector-level investor pricing of revenue and earnings. Account Horizons 31:45–67. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch-51645

Acknowledgements

We thank Cheng-Few Lee (the Editor) and two anonymous referees for their invaluable comments. We thank Hong-Yi Chen, Yehning Chen, and Chih-Yen Lin for their comments and suggestions. The author gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Department of Finance, College of Management, National Taiwan University.

Funding

This study was funded by Department of Finance, College of Management, National Taiwan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables

12,

13,

14,

15 and

16.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, WD., Yu, CT. The information value of interim accounting disclosures: evidence from mandatory monthly revenue reports. Rev Quant Finan Acc 58, 245–295 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-021-00994-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-021-00994-1

Keywords

- Revenue surprises

- Earnings surprises

- Post-earnings-announcement drift

- Analyst forecast revisions

- Interim accounting information