Abstract

Background

This cross-sectional study aimed to explore health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in a large heterogeneous patient sample seeking outpatient treatment at a specialist mental health clinic.

Method

A sample of 1947 patients with common mental disorders, including depressive-, anxiety-, personality-, hyperkinetic- and trauma-related disorders, completed the EuroQoL 5-Dimension 5-Level (EQ-5D-5L) to assess HRQoL. We investigated clinical and sociodemographic factors associated with the EQ-5D index and the EQ Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) using regression analyses.

Results

The sample reported lower HRQoL compared with the general population and primary mental health care patients. Sick leave, disability pension, work assessment allowance, and more symptoms of anxiety and depression were associated with lower EQ-5D index and EQ VAS scores. Furthermore, being male, use of pain medication and having disorders related to trauma were associated with reduced EQ-5D index scores, while hyperkinetic disorders were associated with higher EQ-5D index scores.

Conclusion

HRQoL of psychiatric outpatients is clearly impaired. This study indicated a significant association between employment status, symptom severity, and HRQoL in treatment-seeking outpatients. The findings highlight the importance of assessing HRQoL as part of routine clinical assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) serves as a comprehensive indicator of a person’s well-being in mental and physical aspects related to level of daily functioning [1]. Globally, persons with common mental disorders (CMD) account for one third of years lived with disability [2] and their HRQoL is reduced compared to healthy individuals [3,4,5]. For this reason, increased awareness has been devoted to assessing HRQoL in addition to measures of symptom severity [6] in mental health care.

Early studies on quality-of-life (QoL) in people with anxiety and depression found that QoL was significantly reduced and could vary according to diagnoses. Proportion of patients with a clinically severe QoL impairment ranged from 63% for depression, 59% for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), 26% for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), to 21% for social phobia [7]. These early studies typically used the Short Form Health Survey to assess quality of life, often finding most pronounced effects on the social functioning and mental health components, but also for work, physical health, and home and family [8]. A more recent review found that QoL is reduced before disorder onset, drops during the disorder, and improves following treatment as changes in anxiety and depression are associated with changes in QoL [9]. QoL relates to satisfaction with one’s life, while HRQoL could be defined as the way health affects QoL [10]. For HRQoL, common mental health problems are associated with lower HRQoL compared to people with common medical disorders such as back/neck problems, diabetes, and hypertension [11]. This corresponds with research on quality-adjusted life-years showing that the greatest impact was from arthritis, mood disorders, and personality disorders [12].

The association between mental illness and HRQoL varies across disorders. Of those disorders frequently encountered in outpatient psychiatric settings, anxiety disorders and depressive disorders have reduced HRQoL [8, 13]. The same is true for patients with PTSD [14, 15], who also have been reported to have lower HRQoL than other anxiety disorders [16]. Patients with personality disorders report lower HRQoL compared to patients with other mental disorders [17,18,19] and to have several personality disorders is associated with even lower EQ-5D values [20, 21]. On the other hand, patients with attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), have been found to have lower HRQoL than the general population, but better HRQoL compared to depression and personality disorders [22, 23], and comorbidity has been associated with lower HRQoL [24, 25].

The Norwegian mental healthcare is structured with two main levels: primary care and specialist care. Primary care is usually the first level of care and patients are referred to specialist health care if more specialised treatment is needed, for instance due to a higher severity level. Factors associated with HRQoL in the Norwegian primary mental healthcare have been investigated [26], but these results may not be applicable to patients in specialist care, as the latter are expected to have higher symptom severity and more functional impairment, and thus lower HRQoL. Previous research within Norwegian specialist healthcare restricted to a limited number of mental disorders like anxiety and depression may not be generalizable to more heterogeneous patient samples [27]. For instance, personality disorders are found to be a substantial subgroup of patients in psychiatric outpatient care [28]. There is a need for studies investigating HRQoL scores across different types of patient groups frequently encountered in routine specialist mental healthcare.

Studies have found women to report lower HRQoL [29, 30], while other studies have not found gender differences [26]. Clinical variables like symptoms of anxiety and depression, comorbidity, more subjective health complaints and work impairment or sick leave have been associated with lower HRQoL [27, 31, 32]. Further, psychotropic medication is often prescribed to patients with mental disorders, and use of antidepressants and pain medication have been found related to lower HRQoL [33, 34].

Many of the previous studies were disorder specific, and the reported HRQoL may not be generalizable to psychiatric outpatient samples that typically are very heterogeneous. There is therefore a need for studies investigating HRQoL and factors related to HRQoL in heterogeneous patient populations referred for treatment in specialist healthcare. Moreover, research using the EuroQoL 5-Dimension 5-level (EQ-5D-5L) to assess HRQoL in heterogeneous samples with common mental health disorders is lacking.

In this study, we aimed to investigate factors associated with HRQoL by applying the EQ-5D-5L in a large and heterogeneous patient sample referred for treatment in specialist mental healthcare. Further, we aimed to study differences in HRQoL across mental disorders. In accordance with previous studies, we anticipated that all patient groups would score lower on HRQoL than the general population. Personality disorders were expected to report lower HRQoL than patients with anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, PTSD and trauma-related disorders, and ADHD.

Methods

Sample and procedures

This study reports on data from an observational routine treatment monitoring study with a cross-sectional design. Patients at a psychiatric outpatient facility in the specialist healthcare were invited to participate. In the Norwegian healthcare system, patients must have a mental condition that requires more specialised mental healthcare than provided in the municipality healthcare to be entitled specialist health care, and they must be referred by their general practitioner. As part of routine assessment patients were diagnosed by a clinician using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview [35]. Diagnoses were clustered within their overarching block of the ICD-10 chapter V Mental and behavioural disorders (F00-F99) [36]. We included the following groups of disorders: F30 (Mood disorders), F40 (Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders), F60 (Disorders of adult personality and behaviour), and F90 (Behavioural and emotional disorders with onset usually occurring in childhood and adolescence). These were labelled depressive-, anxiety, personality and hyperkinetic disorders, respectively. In addition, patients diagnosed within F43 Adjustment disorders and F44 Dissociative disorders were labelled “trauma-related disorders” and were treated as a separate diagnostic group from the remaining F40 disorders, corresponding to the DSM-5 categorisation, where trauma- and stressor-related disorders and anxiety disorders are separated. We did not have access to information regarding chronicity of the disorders. The period of data collection was from March 12, 2020, to November 7, 2023.

Measures

As part of routine screening procedures, respondents self-reported if they were currently working/studying, if they recently had been or currently were on sick leave, current use of psychotropic medication, and relationship status, which was coded as being in a relationship or being single. Information regarding age, sex and psychiatric diagnoses were retrieved from clinical register data. Data on disability benefits and Work Assessment Allowance (WAA) were extracted from the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration (NAV). Self-report questionnaires were completed before treatment through an online survey portal (CheckWare), which applies electronic ID for secure login. Respondents received an SMS with a link to the survey, and they received a reminder if the survey was not completed within a week.

EQ-5D-5L [37] is a five-item questionnaire that measures HRQoL. This is a preference-based measure, i.e. the value of different health states is rated according to an individual’s preferences, which has frequently been used to assess HRQoL [38]. It contains five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression) and respondents rate their perceived health on each domain (e.g. mobility) by choosing from five response labels on a level of severity from 1 (no problems; I have no problems in walking about) to 5 (severe problems; I am unable to walk about). The score from each item is combined into a five-digit EQ-5D-5L profile. By use of country-specific preference weights, the profile may be calculated to an EQ-5D index score from 0 (death) to 1 (perfect health). In general population studies, the EQ-5D index value is reported to range from 0.81 to 0.87 [3, 39,40,41]. As country-specific weights do not exist for Norway a “crosswalk” technique was applied using UK preference weights [42].

The EQ-5D-5L also includes a visual analogue scale which asks the respondents “We would like to know how good or bad your health is today”, which is scored on a scale from 0 (The worst health you can imagine) to 100 (The best health you can imagine).

The EQ-5D-5L has previously been used to study HRQoL in patients with CMD in specialist health care, demonstrating good psychometric properties [22, 43]. In Norway the scale has been validated in patients with depression and anxiety at risk of sick leave [27, 44] as well as in the general population [39]. For mental health populations, the EQ-5D-5L has good psychometric properties in patients with depression, anxiety and personality disorders [45,46,47]. Internal reliability was not expected to be high as the EQ-5D-5L measures five separate domains [48]. Cronbach’s alpha in the current study was 0.69.

The Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) [49] was used to measure symptoms of depression. The PHQ-9 has nine items which are rated on a four-point Likert scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). The total score range is from 0 to 27, and a higher score indicates more severe depressive symptoms. The psychometric properties of the PHQ-9 are well-established, including for the Norwegian translation [50]. Internal reliability in this study was good, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82.

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7) [51] was included to measure symptoms of anxiety. The GAD-7 measures the severity of symptoms with seven items that are scored on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). The total score ranges from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating higher severity. Although the GAD-7 was originally developed to screen for symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder, studies show that the instrument also is a useful screener of general anxiety symptoms in heterogeneous patient samples [52]. The internal reliability was good in this study (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.84).

The PHQ-9 and GAD-7 were combined to form the Patient Health Questionnaire Anxiety and Depression Scale (PHQ-ADS) [53], which has a total score range from 0 to 48. The PHQ-ADS has good psychometric properties [54]. The Cronbach’s alpha for the 16-item PHQ-ADS was 0.88.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted in the statistical environment of R. Little’s Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) test was used to identify missing data patterns, with the null hypothesis that data is missing completely at random. The analysis indicated that data was missing completely at random. To make use of all available data, replacement of missing values was handled by multiple imputation (MI), as MI is argued to reduce bias compared to complete case analysis [55,56,57]. MI by chained equations was conducted using the MICE package [58].

Differences between groups of mental disorders on the EQ-5D index and VAS were tested with ANOVAs, with Games-Howell corrected post-hoc tests. Partial eta squared was calculated as effect size and an effect size of 0.01 was interpreted as small, 0.06 as medium and 0.14 as large [59]. Two separate stepwise regression analyses were conducted with EQ-5D index and EQ VAS as outcomes. The first step controlled for background variables (age, sex, and relationship status). The second step controlled for occupational status, with working/studying as reference. In the third step, the use of anxiolytics, antidepressants, pain medication, hypnotics and psychostimulants were included as separate binary variables (yes or no). In the fourth step, PHQ-ADS was included. In the final step, comorbidity and diagnostic groups were added, with the subgroup F30 depressive disorders as reference.

Power analysis

To identify small effect sizes, with α = 0.05 and power = 0.80, a required sample size of N = 1200 would be needed for the ANOVAs (5 groups), and N = 878 for the regression models (12 predictors). The sample size was therefore acceptable.

Sensitivity analysis

Initial screening of the data showed skewed values for the EQ-5D index and EQ VAS, and the Breusch-Pagan test indicated an issue with heteroscedasticity for the regression models. We, therefore, repeated the regression analyses with robust standard errors [60] using the lm_robust function from the estimatr package [61]. In addition, the regression analysis with the EQ-5D index as outcome was repeated where the PHQ-ADS variable was omitted as a covariate.

Results

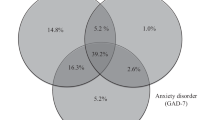

Patients were invited to participate by an SMS that included a link directing them to the online consent form and self-report questionnaires. A total of 3789 responded to the invitation link, of whom 3584 consented to participate and 205 declined. Of those who consented, clinical variables from patient registers were available for 3201 patients. Patients with other disorders (n = 1190), and participants who had not completed the EQ-5D-5L (n = 64), were removed. Data from a total of 1947 respondents (65% female) with a mean age of 32.2 years (SD = 10.3) were included in the analyses. The sample reported a mean PHQ-9 score of 16.1 (SD = 5.51), which indicates moderate-severe symptoms of depression. Except for patients with anxiety disorders who reported depressive symptoms of moderate severity, all diagnostic subgroups reported moderately severe depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 range 15–19) [49]. The mean GAD-7 score was 12.4 (SD = 4.75) which indicates moderate symptoms of generalized anxiety. All diagnostic subgroups reported generalized anxiety symptoms in the moderate severity range (GAD-7 range 10–14) [51]. See Table 1 for background characteristics of the sample. Detailed diagnostic information is provided in Table S1 in the Supplementary Material.

In the dataset, 16 (0.8%) had one or more items missing on the EQ-5D-5L, 11 (0.6%) had missing on the EQ VAS, 142 (7.3%) respondents had not reported their relationship status, and five (0.3%) had missing values on PHQ-ADS. There were no missing values on the remaining variables.

Distribution of EQ-5D-5L domains

Table 2 displays reported problems across EQ-5D-5L domains for patients with single diagnoses and comorbid patients. The proportion reporting problems among the non-comorbid diagnostic subgroups was overall lower for patients with hyperkinetic disorders than the other diagnoses. Those with personality disorders reported the highest proportion of problems in all domains except for pain/discomfort and self-care, where patients with comorbid conditions reported more problems.

EQ-5D index

For the complete sample the mean EQ-5D index was 0.46 (SD = 0.25). Those with a diagnosis of a personality disorder and trauma-related disorders reported the lowest EQ-5D index, both with a mean score of 0.40 (SD = 0.26), followed by depressive (M = 0.46, SD = 0.24) and anxiety disorders (M = 0.49, SD = 0.24). Those with hyperkinetic disorders reported the highest EQ-5D index (M = 0.53, SD = 0.25). The difference in values was statistically significant (F(4) = 15.07, p < 0.001, ηρ² = 0.03). Games-Howell corrected post-hoc tests showed that both personality and trauma-related disorders scored significantly lower than depressive, anxiety and hyperkinetic disorders.

EQ VAS

The complete sample reported a mean EQ VAS value of 47.45 (SD = 18.79). Those with a personality disorder diagnosis reported the lowest EQ VAS with a mean score of 43.70 (SD = 18.30), followed by trauma-related disorders (M = 44.50, SD = 19.00), depressive disorders (M = 46.30, SD = 18.30) and anxiety disorders (M = 49.40, SD = 18.30). Those with hyperkinetic disorders reported the highest EQ VAS score (M = 51.60, SD = 20.00). The differences between the diagnostic subgroups were statistically significant (F(4) = 9.328, p < 0.001, ηρ² = 0.02). Games-Howell adjusted post-hoc tests showed that personality scored significantly lower than anxiety and hyperkinetic disorders, trauma-related scored significantly lower than anxiety and hyperkinetic disorder, depressive scored significantly lower than anxiety disorders, and hyperkinetic scored significantly higher than depressive disorders.

EQ-5D index and EQ VAS - comparisons with primary care and the general population

Both the diagnostic subgroups and the total sample scored lower on both the EQ-5D index and the EQ VAS than the general population [39] and Norwegian primary mental health services [34]. For the EQ-5D index, there were statistically significant differences between the total sample and the primary care sample, (mean difference [MD] = 0.10, 95% CI = 0.06–0.13, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.39), and the general population (MD = 0.34, 95% CI = 0.31–0.37, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.52). For the EQ VAS, there were statistically significant differences between the total sample and the primary care sample (MD = 5.45, 95% CI = 2.75–8.15, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 0.28) and the general population (MD = 30.4, 95% CI = 27.9–33.0 p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 1.64). Figure 1 shows comparisons between the diagnostic subgroups and the total sample with the general population and primary care.

Variables associated with the EQ-5D index

The stepwise linear regression analyses with the EQ-5D index as outcome (see Table 3), male gender, being on sick leave, being on disability pension, receiving WAA, a higher score on the PHQ-ADS, use of pain medication, and trauma-related disorders were associated with lower EQ-5D index. In contrast, hyperkinetic disorders were associated with higher EQ-5D index. Symptoms of anxiety and depression showed the strongest association with the EQ-5D index. The model explained 40% (adjusted R2) of the variance.

As sensitivity analyses, the regression analysis was repeated with robust standard errors. All results were identical to the main analysis, except for use of pain medication which was no longer significant. Moreover, we repeated the regression analysis with the EQ-5D index as outcome, with the PHQ-ADS excluded as covariate. In the additional analysis, relationship status, anxiety medication, comorbidity, and anxiety disorders turned significant. Male gender was no longer a significant covariate. Sick leave, disability benefits, WAA, pain medication, hyperkinetic and trauma-related disorders remained significant covariates. The total variance explained was 9%.

Variables associated with the EQ VAS

In the regression analysis with the EQ VAS as outcome (see Table 4), the results showed that being on sick leave, disability pension, receiving WAA, and a higher score on PHQ-ADS were associated with a lower score on the EQ VAS. The variance explained (adjusted R2) for the model was 26%, where symptoms of anxiety and depression accounted for most of the variance explained. The sensitivity analysis with robust standard errors showed equal results as the main analysis.

Discussion

This study aimed to explore HRQoL in outpatients with CMD seeking treatment at a specialist mental health care clinic. The sample included patients with anxiety, depressive, personality, hyperkinetic and trauma-related disorders. Overall, we found that patients with personality and trauma-related disorders reported the lowest scores on the EQ-5D index and EQ VAS, followed by depression and anxiety, with hyperkinetic disorders reporting the highest scores. The results are expected when compared to previous studies of HRQoL using the EQ-5D-5L [22, 27, 47, 62] and support the scale as a useful measure of HRQoL also in heterogeneous psychiatric outpatient samples.

The complete sample reported an EQ-5D index of 0.46, and an EQ VAS score of 47.5. The sample scored lower than the general population and patients in the Norwegian primary mental health service [34, 39]. The Norwegian healthcare system is organised in such a way that patients in need of more specialised care are referred from primary care to specialist care, which may explain the lower scores in our study. The EQ-5D index and EQ VAS scores are also lower than a previous sample treated in the Norwegian specialist health care [63] which included patients referred for psychotherapy and work-focused interventions due to anxiety and/or depression. Another Norwegian study in the specialist health care [32] reported considerably higher EQ VAS scores on the EQ-5D-3 L for patients with CMD, compared to our study and Lindberg et al. [34]. However, in the study by Reme et al. [32] CMD was evaluated based on self-report questionnaires, while we extracted diagnoses from medical records based on clinician-administered structured interviews, and the difference in diagnostic procedures may contribute to explain the differences in HRQoL scores. Moreover, the sample in the current study is characterized by great heterogeneity and included several mental disorders that are frequently treated in specialist healthcare. This may explain the more severe HRQoL compared to what has been reported in several previous studies. The present study adds to the literature by reporting HRQoL in a representative sample of psychiatric outpatients and provides a more accurate description of routine clinical settings where a broad range of mental disorders are frequently encountered.

The overall EQ VAS score in the current study was higher than what has been reported in psychiatric samples in England and the Netherlands [22], but similar to a Spanish study within the specialist health service [43]. However, in the latter study, the reported EQ-5D index was higher compared to our results. The EQ-5D index is derived from five different domains and calculated based on country specific weights, whereas the EQ VAS is based on one question which is not weighted. This may contribute to explain the greater similarity in EQ VAS scores compared to EQ-5D index scores. Additionally, possible cultural differences have been suggested to influence HRQoL, for example, the Spanish culture has been described more collectivistic compared to northern European countries [64]. Furthermore, previous studies have shown that immigrants representing an ethnic minority or originating from countries with societal challenges report reduced HRQoL [26, 65, 66]. However, the potential cultural impact on HRQoL is debated, and although health utilities are shown to vary between countries, cultural values have not systematically been shown to explain these differences [67]. Instead, country-specific weighting has been recommended, and the results of this study should therefore be replicated in the future when Norwegian value sets are available.

The reduced EQ-5D index and EQ VAS scores in patients with depressive and anxiety disorders were comparable to previous research [9]. Studies show that depression has high comorbidity with other mental disorders [68], and e.g. comorbid depression and personality disorders have been associated with worse HRQoL [69]. Our results showed that the EQ-5D index and EQ VAS were lower in comorbid patients than patients with single disorders, except for personality disorders. However, in routine clinics screening for comorbidity, including personality disorders, is often not conducted in a systematic manner [28, 70], perhaps due to high caseloads among clinicians, and it is possible that the degree of comorbidity is underreported in this study.

The EQ-5D index score reported by patients with personality disorders were, with the exception of trauma-related disorders, lower than the remaining diagnostic subgroups in the current study, which supports previous studies where personality disorders were systematically associated with lower HRQoL [12, 20, 21]. Personality disorders are found to be frequent, yet often undiagnosed, in specialist healthcare [28, 70, 71]. It is a strength that such disorders are included in the current study, as this reflects the heterogeneity of psychiatric outpatients more accurately. However, in Norwegian routine clinical settings a practice of underdiagnosing personality disorders has been suggested [72]. This may thus be true for the current sample as well, meaning that the actual prevalence of personality disorders is higher than the numbers reported. In recent years, effective treatments have been developed for several personality disorders, and a clinical implication of our study is that health professionals should strengthen the recognition of personality disorders as part of the routine assessment, to make effective treatment available for patients with personality disorders to improve HRQoL in this patient group.

The overall reduced HRQoL reported by patients with trauma-related disorders corroborates previous studies [8, 73]. In the DSM-IV and the ICD-10, trauma-related disorders are categorised as anxiety disorders. However, in this study we treated trauma-related disorders, including PTSD, as a separate subgroup from anxiety disorders. This categorisation is in line with the DSM-5 which included a separate chapter for Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorders. A possible explanation for the low HRQoL reported by patients with trauma-related disorders is that the patients had suffered multiple traumas. Furthermore, previous research has noted a high symptom overlap between complex PTSD and personality disorders [74] and a comorbidity rate of up to 50% between the two disorders [75]. Considering the aforementioned fact that comorbidity and personality disorders are underdiagnosed in routine clinics, the association between trauma-related disorders, personality disorders and HRQoL should be investigated further in future studies.

Patients with hyperkinetic disorders reported the highest EQ-5D index. The index value is lower than a Swedish study for newly diagnosed patients with ADHD [23] and similar to a Swedish study of unremitted ADHD patients [76]. Combined with an increased awareness that ADHD persists into adulthood [77] and increased use of psychostimulants in the Nordic countries [78], there has been an increase in referrals to the specialist healthcare for assessments of hyperkinetic disorders. The higher HRQoL reported by patients with hyperkinetic disorders in this study indicates that, on the group level, these patients have less functional impairment than the other disorders studied. This finding may inform health policy decisions, as the allocation of resources is often based on an evaluation of patients’ impairment, their need of care and the expected benefit from the care provided.

Being on sick leave, disability pension, WAA, and higher symptom level were associated with lower EQ-5D index and EQ VAS scores, which is in line with previous Norwegian and international studies [27, 34, 79]. These findings have clinical relevance and suggest that mental health treatment should aim at increasing work participation, as treatment interventions aimed at both symptom reduction and improved work functioning are beneficial for patients with mental disorders [80].

Moreover, we found that patients with trauma-related disorders and men were associated with lower scores on the EQ-5D index, but not the EQ VAS. The former finding corroborates previous studies that found anxiety disorders and PTSD to have reduced HRQoL [8]. The latter finding contradicts previous research which has found women to report lower EQ-5D index scores than men [27, 81], or no gender differences [34].

Pain medication was associated with lower EQ-5D index, which corroborated a Norwegian study in primary health care [34]. This finding is noteworthy, as it may be expected that there are more patients with a need for pain medication treated in primary care. The underlying pathology causing a need for pain medication is likely to impact HRQoL to a great extent, however, we did not have access to medical records to study this in detail. Mental health professionals should routinely screen for symptoms of pain, as the co-occurrence of pain and mental health problems may require specifically tailored interventions [82]. However, the finding must be treated with caution, as pain medication was not a significant covariate when robust regression analysis was applied. The results did not reveal significant associations between other psychotropic drugs and HRQoL, however, we did not explore if the association between medication use and HRQoL varied between diagnoses, which may be a relevant area for future research, as clinical guidelines recommend different medications to be prescribed for various mental disorders.

Symptoms of anxiety and depression were most strongly related to the EQ-5D index and the EQ VAS. This was expected, as previous studies have found higher symptom levels to be associated with lower scores on the EQ-5D index and the EQ VAS [27, 83]. However, researchers have warned about a potential overlap between symptom measures and measures of HRQoL [84]. The index value is derived from the five EQ-5D domains, which include anxiety/depression. We therefore conducted an additional analysis excluding the measure of anxiety and depression symptoms. In the analysis, being in a relationship and anxiety disorders were associated with better HRQoL, and use of anxiety medication and comorbidity were associated with worse HRQoL. The association between gender and HRQoL ceased to be significant, while the remaining variables had equal effects as in the original analysis. This analysis explained a smaller amount of the variance in the EQ-5D index compared to the analysis that included the symptom measure. The fact that psychological symptoms had such a profound effect on the outcome, suggests that future studies should be careful when considering controlling for symptoms of anxiety and depression, due to the potential overlap with HRQoL.

Limitations

A strength of this study is the large heterogeneous sample with clinician-assessed mental disorders representative of outpatient specialist mental health care. However, there are limitations that should be noted. The cross-sectional design limits the conclusion that can be drawn, and future studies should include post-treatment assessment to evaluate factors related to change in HRQoL. The use of psychotropic medication was self-reported and not retrieved from registers at the treatment facility. Moreover, medication use was recorded at the time of referral, and medication dosage may have been changed or discontinued after treatment start. Substance consumption was not reported, which is a limitation given that previous studies have shown a high comorbidity rate between mental disorders and substance use disorder [85], and further, that dual diagnoses are associated with lower HRQoL [86, 87]. Patients with psychotic disorders were treated at different units than those included in this study, which is a limitation, and consequently the findings of the current study may not generalize to more heterogeneous samples that include patients diagnosed with psychotic disorders. Furthermore, the Cronbach’s alpha of the EQ-5D-5L was below the recommended cut-off of 0.70 [88]. However, it has been argued that internal consistency is not a good indication of psychometric properties for the EQ-5D-5L, as it is a multidimensional construct based on five domains that are separate from each other. Hence, internal reliability is not expected to be high [48, 89] and previous research has reported equally low internal reliability [90]. Lastly, the EQ-5D-5L is limited to five domains, and future studies may consider using alternative measures, such as the SF-36 [91], to capture other aspects of relevance for HRQoL.

Conclusion

The present study indicates that treatment seeking patients in specialist mental healthcare are characterised by reduced HRQoL compared both to the general population and primary care patients. The factors most strongly related to HRQoL were occupational status and mental health symptoms, which suggests that both are important areas to target in clinical work. The study shows the importance of routinely assessing HRQoL in patients with CMD.

Data availability

Data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Kaplan, R. M., & Hays, R. D. (2022). Health-related quality of life measurement in public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 43, 355–373.

Vigo, D., Thornicroft, G., & Atun, R. (2016). Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(2), 171–178.

Saarni, S. I., Suvisaari, J., Sintonen, H., Pirkola, S., Koskinen, S., Aromaa, A., et al. (2007). Impact of psychiatric disorders on health-related quality of life: General population survey. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 190(4), 326–332.

Evans, S., Banerjee, S., Leese, M., & Huxley, P. (2007). The impact of mental illness on quality of life: A comparison of severe mental illness, common mental disorder and healthy population samples. Quality of life Research, 16, 17–29.

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Linzer, M., Hahn, S. R., Williams, J. B., Degruy, F. V., et al. (1995). Health-related quality of life in primary care patients with mental disorders: Results from the PRIME-MD 1000 study. Jama, 274(19), 1511–1517.

Berghöfer, A., Martin, L., Hense, S., Weinmann, S., & Roll, S. (2020). Quality of life in patients with severe mental illness: A cross-sectional survey in an integrated outpatient health care model. Quality of Life Research, 29, 2073–2087.

Rapaport, M. H., Clary, C., Fayyad, R., & Endicott, J. (2005). Quality-of-life impairment in depressive and anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(6), 1171–1178.

Olatunji, B. O., Cisler, J. M., & Tolin, D. F. (2007). Quality of life in the anxiety disorders: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 27(5), 572–581.

Hohls, J. K., König, H-H., Quirke, E., & Hajek, A. (2021). Anxiety, depression and quality of life—a systematic review of evidence from longitudinal observational studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 12022.

Karimi, M., & Brazier, J. (2016). Health, health-related quality of life, and quality of life: What is the difference? Pharmacoeconomics, 34, 645–649.

Cook, E. L., & Harman, J. S. (2008). A comparison of health-related quality of life for individuals with mental health disorders and common chronic medical conditions. Public Health Reports, 123(1), 45–51.

Penner-Goeke, K., Henriksen, C. A., Chateau, D., Latimer, E., Sareen, J., & Katz, L. Y. (2015). Reductions in quality of life associated with common mental disorders: Results from a nationally representative sample. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 76(11), 17176.

Judd, L. L., Akiskal, H. S., Zeller, P. J., Paulus, M., Leon, A. C., Maser, J. D., et al. (2000). Psychosocial disability during the long-term course of unipolar major depressive disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(4), 375–380.

Danielsson, F., Schultz Larsen, M., Nørgaard, B., & Lauritsen, J. (2018). Quality of life and level of post-traumatic stress disorder among trauma patients: A comparative study between a regional and a university hospital. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine, 26(1), 1–9.

Le, Q. A., Doctor, J. N., Zoellner, L. A., & Feeny, N. C. (2013). Minimal clinically important differences for the EQ-5D and QWB-SA in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): Results from a doubly randomized preference trial (DRPT). Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 11(1), 1–9.

Beard, C., Weisberg, R. B., & Keller, M. B. (2010). Health-related quality of life across the anxiety disorders: Findings from a sample of primary care patients. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24(6), 559–564.

Cramer, V., Torgersen, S., & Kringlen, E. (2006). Personality disorders and quality of life. A population study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 47(3), 178–184.

Dixon-Gordon, K. L., Whalen, D. J., Layden, B. K., & Chapman, A. L. (2015). A systematic review of personality disorders and health outcomes. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 56(2), 168.

Huang, I-C., Lee, J. L., Ketheeswaran, P., Jones, C. M., Revicki, D. A., & Wu, A. W. (2017). Does personality affect health-related quality of life? A systematic review. PloS One, 12(3), e0173806.

Soeteman, D. I., Verheul, R., & Busschbach, J. J. (2008). The burden of disease in personality disorders: Diagnosis-specific quality of life. Journal of Personality Disorders, 22(3), 259–268.

Davidson, K., Norrie, J., Tyrer, P., Gumley, A., Tata, P., Murray, H., et al. (2006). The effectiveness of cognitive behavior therapy for borderline personality disorder: Results from the borderline personality disorder study of cognitive therapy (BOSCOT) trial. Journal of Personality Disorders, 20(5), 450–465.

Janssen, M., Pickard, A. S., Golicki, D., Gudex, C., Niewada, M., Scalone, L., et al. (2013). Measurement properties of the EQ-5D-5L compared to the EQ-5D-3L across eight patient groups: A multi-country study. Quality of life Research, 22, 1717–1727.

Ahnemark, E., Di Schiena, M., Fredman, A-C., Medin, E., Söderling, J., & Ginsberg, Y. (2018). Health-related quality of life and burden of illness in adults with newly diagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Sweden. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 1–11.

Pagotto, L. F., Mendlowicz, M. V., Coutinho, E. S. F., Figueira, I., Luz, M. P., Araujo, A. X., et al. (2015). The impact of posttraumatic symptoms and comorbid mental disorders on the health-related quality of life in treatment-seeking PTSD patients. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 58, 68–73.

Watson, H. J., Swan, A., & Nathan, P. R. (2011). Psychiatric diagnosis and quality of life: The additional burden of psychiatric comorbidity. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 52(3), 265–272.

Lindberg, M. S., Brattmyr, M., Lundqvist, J., Roos, E., Solem, S., Hjemdal, O., et al. (2023). Sociodemographic factors and use of pain medication are associated with health-related quality of life: Results from an adult community mental health service in Norway. Quality of Life Research, 32(11), 3135–3145.

Sandin, K., Shields, G. E., Gjengedal, R. G., Osnes, K., Bjørndal, M. T., & Hjemdal, O. (2021). Self-reported health in patients on or at risk of sick leave due to depression and anxiety: Validity of the EQ-5D. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 655151.

Zimmerman, M., Rothschild, L., & Chelminski, I. (2005). The prevalence of DSM-IV personality disorders in psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(10), 1911–1918.

Braveman, P., & Gottlieb, L. (2014). The social determinants of health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Reports, 129(1_suppl2), 19–31.

Van Wilder, L., Charafeddine, R., Beutels, P., Bruyndonckx, R., Cleemput, I., Demarest, S., et al. (2022). Belgian population norms for the EQ-5D-5L, 2018. Quality of Life Research, 31(2), 527–537.

Sobocki, P., Ekman, M., Ågren, H., Krakau, I., Runeson, B., Mårtensson, B., et al. (2007). Health-related quality of life measured with EQ‐5D in patients treated for depression in primary care. Value in Health, 10(2), 153–160.

Reme, S. E., Grasdal, A. L., Løvvik, C., Lie, S. A., & Øverland, S. (2015). Work-focused cognitive–behavioural therapy and individual job support to increase work participation in common mental disorders: a randomised controlled multicentre trial. Occupational and environmental medicine.

Revicki, D. A., & Wood, M. (1998). Patient-assigned health state utilities for depression-related outcomes: Differences by depression severity and antidepressant medications. Journal of Affective Disorders, 48(1), 25–36.

Lindberg, M. S., Brattmyr, M., Lundqvist, J., Roos, E., Solem, S., Hjemdal, O. (2023). Sociodemographic factors and use of pain medication are associated with health-related quality of life: Results from an adult community mental health service in Norway. Quality of Life Research. :1–11.

Sheehan, D. V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, K. H., Amorim, P., Janavs, J., Weiller, E., et al. (1998). The mini-international neuropsychiatric interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59(suppl 20), 22–33.

World Health Organization (WHO). (1993). International Statistical Classification of Diseases and related health problems 10th revision (ICD-10). Organization WH.

Herdman, M., Gudex, C., Lloyd, A., Janssen, M., Kind, P., Parkin, D., et al. (2011). Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Quality of life Research, 20, 1727–1736.

Richardson, J., Iezzi, A., & Khan, M. A. (2015). Why do multi-attribute utility instruments produce different utilities: The relative importance of the descriptive systems, scale and ‘micro-utility’effects. Quality of Life Research, 24, 2045–2053.

Garratt, A. M., Hansen, T. M., Augestad, L. A., Rand, K., & Stavem, K. (2021). Norwegian population norms for the EQ-5D-5L: Results from a general population survey. Quality of Life Research. :1–10.

Burström, K., Johannesson, M., & Diderichsen, F. (2001). Swedish population health-related quality of life results using the EQ-5D. Quality of life Research, 10, 621–635.

Luo, N., Johnson, J. A., Shaw, J. W., Feeny, D., & Coons, S. J. (2005). Self-reported health status of the general adult US population as assessed by the EQ-5D and Health Utilities Index. Medical care. :1078–1086.

Statens legemiddelverk (2021). Guidelines for the submission of documentation for single technology assessment (STA) of pharmaceuticals - Legemiddelverket.

Bilbao, A., Martín-Fernández, J., García-Pérez, L., Mendezona, J. I., Arrasate, M., Candela, R., et al. (2022). Psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L in patients with major depression: Factor analysis and Rasch analysis. Journal of Mental Health, 31(4), 506–516.

Sandin, K., Shields, G., Gjengedal, R. G., Osnes, K., Bjørndal, M. T., Reme, S. E., et al. (2023). Responsiveness to change in health status of the EQ-5D in patients treated for depression and anxiety. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 21(1), 35.

Brazier, J., Connell, J., Papaioannou, D., Mukuria, C., Mulhern, B., Peasgood, T., et al. (2014). A systematic review, psychometric analysis and qualitative assessment of generic preference-based measures of health in mental health populations and the estimation of mapping functions from widely used specific measures. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester England), 18(34), vii.

Abdin, E., Chong, S. A., Seow, E., Peh, C. X., Tan, J. H., Liu, J., et al. (2019). A comparison of the reliability and validity of SF-6D, EQ-5D and HUI3 utility measures in patients with schizophrenia and patients with depression in Singapore. Psychiatry Research, 274, 400–408.

Mulhern, B., Mukuria, C., Barkham, M., Knapp, M., Byford, S., & Brazier, J. (2014). Using generic preference-based measures in mental health: Psychometric validity of the EQ-5D and SF-6D. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 205(3), 236–243.

Feng, Y-S., Kohlmann, T., Janssen, M. F., & Buchholz, I. (2021). Psychometric properties of the EQ-5D-5L: A systematic review of the literature. Quality of Life Research, 30, 647–673.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, J. B. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613.

Brattmyr, M., Lindberg, M. S., Solem, S., Hjemdal, O., & Havnen, A. (2022). Factor structure, measurement invariance, and concurrent validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and the generalized anxiety disorder scale-7 in a Norwegian psychiatric outpatient sample. Bmc Psychiatry, 22(1), 461.

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097.

Beard, C., & Björgvinsson, T. (2014). Beyond generalized anxiety disorder: Psychometric properties of the GAD-7 in a heterogeneous psychiatric sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(6), 547–552.

Kroenke, K., Wu, J., Yu, Z., Bair, M. J., Kean, J., Stump, T., et al. (2016). The patient health questionnaire anxiety and depression scale (PHQ-ADS): Initial validation in three clinical trials. Psychosomatic Medicine, 78(6), 716.

Kroenke, K., Baye, F., & Lourens, S. G. (2019). Comparative validity and responsiveness of PHQ-ADS and other composite anxiety-depression measures. Journal of Affective Disorders, 246, 437–443.

Cummings, P. (2013). Missing data and multiple imputation. JAMA Pediatrics, 167(7), 656–661.

Sterne, J. A., White, I. R., Carlin, J. B., Spratt, M., Royston, P., Kenward, M. G. (2009). Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: Potential and pitfalls. Bmj. ;338.

Pepinsky, T. B. (2018). A note on listwise deletion versus multiple imputation. Political Analysis, 26(4), 480–488.

van Buuren, S., & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. (2011). Mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 45, 1–67.

Richardson, J. T. (2011). Eta squared and partial eta squared as measures of effect size in educational research. Educational Research Review, 6(2), 135–147.

Huber, P. J. (1964). Robust estimation of a location parameter. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 35(1), 73–101.

Blair, G., Cooper, J., Coppock, A., Humphreys, M., Sonnet, L., Fultz, N. (2018). Package ‘estimatr’ Stat. ;7(1):295–318.

Sagayadevan, V., Lee, S. P., Ong, C., Abdin, E., Chong, S. A., & Subramaniam, M. (2018). Quality of life across mental disorders in psychiatric outpatients. Ann Acad Med Singap, 47, 243–252.

Sandin, K., Shields, G. E., Gjengedal, R. G., Osnes, K., & Hjemdal, O. (2021). Self-reported health in patients on or at risk of sick leave due to depression and anxiety: Validity of the EQ-5D. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 655151.

Bailey, H., & Kind, P. (2010). Preliminary findings of an investigation into the relationship between national culture and EQ-5D value sets. Quality of Life Research, 19, 1145–1154.

Sevillano, V., Basabe, N., Bobowik, M., & Aierdi, X. (2014). Health-related quality of life, ethnicity and perceived discrimination among immigrants and natives in Spain. Ethnicity & Health, 19(2), 178–197.

Watkinson, R. E., Sutton, M., & Turner, A. J. (2021). Ethnic inequalities in health-related quality of life among older adults in England: Secondary analysis of a national cross-sectional survey. The Lancet Public Health, 6(3), e145–e54.

Roudijk, B., Donders, A. R. T., & Stalmeier, P. F. (2019). Cultural values: Can they explain differences in health utilities between countries? Medical Decision Making, 39(5), 605–616.

Kringlen, E., Torgersen, S., & Cramer, V. (2001). A Norwegian psychiatric epidemiological study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(7), 1091–1098.

Feenstra, D. J., Hutsebaut, J., Laurenssen, E. M., Verheul, R., Busschbach, J. J., & Soeteman, D. I. (2012). The burden of disease among adolescents with personality pathology: Quality of life and costs. Journal of Personality Disorders, 26(4), 593–604.

Øiesvold, T., Nivison, M., Hansen, V., Skre, I., Østensen, L., & Sørgaard, K. W. (2013). Diagnosing comorbidity in psychiatric hospital: Challenging the validity of administrative registers. BMC Psychiatry, 13(1), 1–7.

Geile, J., Aasly, J., Madea, B., & Schrader, H. (2020). Incidence of the diagnosis of factitious disorders–nationwide comparison study between Germany and Norway. Forensic Science Medicine and Pathology, 16, 450–456.

Sjåstad, H. N., Gråwe, R. W., & Egeland, J. (2012). Affective disorders among patients with borderline personality disorder. PloS One, 7(12), e50930.

Jellestad, L., Vital, N. A., Malamud, J., Taeymans, J., & Mueller-Pfeiffer, C. (2021). Functional impairment in posttraumatic stress disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 136, 14–22.

Powers, A., Petri, J. M., Sleep, C., Mekawi, Y., Lathan, E. C., Shebuski, K., et al. (2022). Distinguishing PTSD, complex PTSD, and borderline personality disorder using exploratory structural equation modeling in a trauma-exposed urban sample. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 88, 102558.

Scheiderer, E. M., Wood, P. K., & Trull, T. J. (2015). The comorbidity of borderline personality disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder: Revisiting the prevalence and associations in a general population sample. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 2(1), 11.

Edvinsson, D., & Ekselius, L. (2018). Six-year outcome in subjects diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder as adults. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 268(4), 337–347.

Kooij, S. J., Bejerot, S., Blackwell, A., Caci, H., Casas-Brugué, M., Carpentier, P. J., et al. (2010). European consensus statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD: The European Network adult ADHD. BMC Psychiatry, 10, 1–24.

Karlstad, Ø., Zoëga, H., Furu, K., Bahmanyar, S., Martikainen, J. E., Kieler, H., et al. (2016). Use of drugs for ADHD among adults—a multinational study among 15.8 million adults in the nordic countries. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 72, 1507–1514.

Bouwmans, C., Vemer, P., van Straten, A., Tan, S. S., & Hakkaart-van Roijen, L. (2014). Health-related quality of life and productivity losses in patients with depression and anxiety disorders. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 56(4), 420–424.

Gjengedal, R. G., Osnes, K., Reme, S. E., Lagerveld, S. E., Johnson, S. U., Lending, H. D., et al. (2022). Changes in depression domains as predictors of return to work in common mental disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders, 308, 520–527.

Boerma, T., Hosseinpoor, A. R., Verdes, E., & Chatterji, S. (2016). A global assessment of the gender gap in self-reported health with survey data from 59 countries. BMC Public Health, 16, 1–9.

Kohrt, B. A., Griffith, J. L., & Patel, V. (2018). Chronic pain and mental health: Integrated solutions for global problems. Pain, 159, S85–S90.

König, H-H., Born, A., Günther, O., Matschinger, H., Heinrich, S., Riedel-Heller, S. G., et al. (2010). Validity and responsiveness of the EQ-5D in assessing and valuing health status in patients with anxiety disorders. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 8(1), 1–9.

Hays, R. D., & Fayers, P. M. (2021). Overlap of depressive symptoms with health-related quality-of-life measures. Pharmacoeconomics, 39(6), 627–630.

Lai, H. M. X., Cleary, M., Sitharthan, T., & Hunt, G. E. (2015). Prevalence of comorbid substance use, anxiety and mood disorders in epidemiological surveys, 1990–2014: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 154, 1–13.

Benaiges, I., Prat, G., & Adan, A. (2012). Health-related quality of life in patients with dual diagnosis: Clinical correlates. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 10, 1–11.

Marquez-Arrico, J. E., Navarro, J. F., & Adan, A. (2020). Health-related quality of life in male patients under treatment for substance use disorders with and without major depressive disorder: Influence in clinical course at one-year follow-up. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(10), 3110.

Prinsen, C. A., Mokkink, L. B., Bouter, L. M., Alonso, J., Patrick, D. L., De Vet, H. C., et al. (2018). COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Quality of life Research, 27, 1147–1157.

Davies, A., Waylen, A., Leary, S., Thomas, S., Pring, M., Janssen, B., et al. (2020). Assessing the validity of EQ-5D-5L in people with head & neck cancer: Does a generic quality of life measure perform as well as a disease-specific measure in a patient population? Oral Oncology, 101, 104504.

Hernandez, G., Garin, O., Dima, A. L., Pont, A., Martí Pastor, M., Alonso, J., et al. (2019). EuroQol (EQ-5D-5L) validity in assessing the quality of life in adults with asthma: Cross-sectional study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(1), e10178.

WareJr, J. E., & Gandek, B. (1998). Overview of the SF-36 health survey and the international quality of life assessment (IQOLA) project. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 51(11), 903–912.

Funding

Open access funding provided by NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology (incl St. Olavs Hospital - Trondheim University Hospital). The Norwegian University of Science and Technology provided open-access funding for the study.

Open access funding provided by NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology (incl St. Olavs Hospital - Trondheim University Hospital)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study. AH wrote the first draft of the manuscript and all authors contributed to revising and editing the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (case number REK 2019/31836) and the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (case number 605327).

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Havnen, A., Lindberg, M.S., Lundqvist, J. et al. Health-related quality of life in psychiatric outpatients: a cross-sectional study of associations with symptoms, diagnoses, and employment status. Qual Life Res (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-024-03748-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-024-03748-3