Abstract

Purpose

Although stress emerges when environmental demands exceed personal resources, existing measurement methods for stress focus only on one aspect. The newly-developed Short Stress Overload Scale (SOS-S) assesses the extent of stress by assessing both event load (i.e., environmental demands) and personal vulnerability (i.e., personal resources). The present study was designed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Chinese version of Stress Overload Scale-Short (SOS-SC), and further examine its roles in screening mental health status.

Methods

A total of 1364 participants were recruited from communities and colleges for scale validation.

Results

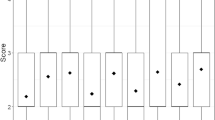

Reliabilities were good throughout the subsamples (ω > 0.80). Confirmatory factor analysis indicated the acceptable goodness-of-fit for the two-factor correlated model (Sample 1: 560 community residents). Multi-group confirmatory factor analysis confirmed measurement invariance across community residents (Sample 1) and college students (Sample 2 and Sample 3). Criterion validity and convergent validity were established (Sample 2: 554 college students). Latent moderated structural equations demonstrated that the relationship between SOS-SC and depression is moderated by social support (Sample 2), further validating the SOS-SC. In addition, the SOS-SC effectively screened individuals in a population at different levels of mental health status (i.e., “at risk” vs. “at low risk” for depression symptoms and/or wellbeing).

Conclusion

The SOS-SC exhibits acceptable psychometric properties in the Chinese context. That said, the two aspects of stress can be differentiated by the Chinese context, therefore, the SOS-SC can be used to measure stress and screen mental health status among the Chinese population, and monitor and evaluate health-promoting interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.44.3.513.

Lazarus, R. S. (1990). Theory-based stress measurement. Psychological Inquiry, 1(1), 3–13. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0101_1.

Li, T. T., Duan, W., & Guo, P. F. (2017). Character strengths, social anxiety, and physiological stress reactivity. Peerj, 5, e3396. doi:10.7717/peerj.3396.

McGrath, J. E. (1970). A conceptual formulation for research on stress. In J. E. McGath (Ed.), Social and psychological factors in stress (pp. 10–21). New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Cohen, S., Kessler, R. C., & Gordon, L. U. (1995). Strategies for measuring stress in studies of psychiatric and physical disorders. In S. Cohen, R. C. Kessler & L. U. Gordon (Eds.), Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists (pp. 3–26). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Cohen, S., Janicki-Deverts, D., & Miller, G. E. (2007). Psychological stress and disease. JAMA, 298(14), 1685–1687. doi:10.1001/jama.298.14.1685.

Amirkhan, J. H. (2012). Stress overload: A new approach to the assessment of stress. American Journal of Community Psychology, 49(1–2), 55–71. doi:10.1007/s10464-011-9438-x.

Amirkhan, J. H., Urizar, G. G., & Clark, S. (2015). Criterion validation of a stress measure: The Stress Overload Scale. Psychological Assessment, 27(3), 985–996. doi:10.1037/pas0000081.

Cohen, S., Gianaros, P. J., & Manuck, S. B. (2016). A stage model of stress and disease. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 11(4), 456–463. doi:10.1177/1745691616646305.

Mcewen, B. S. (2008). Central effects of stress hormones in health and disease: Understanding the protective and damaging effects of stress and stress mediators. European Journal of Pharmacology, 583(2–3), 174–185. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.11.071.

Martin, P. R. (2016). Stress and primary headache: Review of the research and clinical management. Current Pain and Headache Reports, 20(7), 8. doi:10.1007/s11916-016-0576-6.

Dohrenwend, B. S. (2002). Social stress and community psychology. In T. A. Revenson (Ed.), A quarter century of community psychology: Reading from the American Journal of Community Psychology (pp. 103–117). New York: Plenum.

Bernard, L. C., & Krupat, E. (1994). Health psychology: Bio-psychosocial factor in health and illness. Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace College Publishers.

Lessard, J., & Holman, E. A. (2014). FKBP5 and CRHR1 polymorphisms moderate the stress-physical health association in a national sample. Health Psychology, 33(9), 1046–1056. doi:10.1037/a0033968.

Dohrenwend, B. P. (2006). Inventorying stressful life events as risk factors for psychopathology: Toward resolution of the problem of intracategory variability. Psychological Bulletin, 132(3), 477–495. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.3.477.

Hobfoll, S. E., Schwarzer, R., & Chon, K. K. (1998). Disentangling the stress labyrinth: Interpreting the meaning of the term stress as it is studied in health context. Anxiety Stress and Coping, 11(3), 181–212. doi:10.1080/10615809808248311.

Brantley, P., Jones, G., & Boudreaux, E. (1997). Weekly stress inventory. In C. Zalaquett & R. Wood. (Eds.), Evaluating stress: A book of resources (pp. 405–420). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow.

Windle, G., Bennett, K. M., & Noyes, J. (2011). A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 9, 18. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-9-8.

Mazure, C. M. (1998). Life stressors as risk factors in depression. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5(3), 291–313. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00151.x.

Duan, W. (2016). The benefits of personal strengths in mental health of stressed students: A longitudinal investigation. Quality of Life Research, 25(11), 2879–2888. doi:10.1007/s11136-016-1320-8.

Dahlin, M., Joneborg, N., & Runeson, B. (2005). Stress and depression among medical students: A cross-sectional study. Medical Education, 39(6), 594–604. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02176.x.

Assari, S., & Lankarani, M. M. (2016). Association between stressful life events and depression: Intersection of race and gender. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 3(2), 349–356. doi:10.1007/s40615-015-0160-5.

Mazurka, R., Wynne-Edwards, K. E., & Harkness, K. L. (2016). Stressful life events prior to depression onset and the cortisol response to stress in youth with first onset versus recurrent depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44(6), 1173–1184. doi:10.1007/s10802-015-0103-y.

Hammen, C. L. (2014). Stress and depression: Old questions, new approaches. Current Opinion in Psychology, 4, 80–85. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2014.12.024.

Duan, W., Ho, S. M., Siu, B. P., Li, T., & Zhang, Y., (2015). Role of virtues and perceived life stress in affecting psychological symptoms among Chinese college students. Journal of American College Health, 63(1), 32–39. doi:10.1080/07448481.2014.963109.

Monroe, S. M., Slavich, G. M., & Gotlib, I. H. (2014). Life stress and family history for depression: The moderating role of past depressive episodes. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 49, 90–95. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.11.005.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.98.2.310.

Amirkhan, J. H. (2016). A brief stress diagnostic tool: The short Stress Overload Scale. Assessment. doi:10.1177/1073191116673173.

World Health Organization. (2017). Mental health: A state of well-being. Retrieved March 12, 2017 from http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/mental_health/en/.

Dodge, R., Daly, A. P., Huyton, J., & Sanders, L. D. (2012). The challenge of defining wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2(3), 222–235. doi:10.5502/ijw.v2i3.4.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. -Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879.

Van de Vijver, F., & Hambleton, R. K. (1996). Translating tests. European Psychologist, 1(2), 89–99. doi:10.1027/1016-9040.1.2.89.

Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., & Ferraz, M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 25(25), 3186–3191. doi:10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014.

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2.

Zhou, K. N., Lie, H. X., Wei, X. L., Yin, J., Liang, P. F., Zhang, H. M., et al. (2015). Reliability and validity of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in Chinese mainland patients with methadone maintenance treatment. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 60, 182–188. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2015.03.007.

Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the depression, anxiety and stress Scales (2 edn.). Sydney: Psychological Foundation.

Wang, K., Shi, H. S., Geng, F. L., Zou, L. Q., Tan, S. P., Wang, Y., Neumann, D. L., Shum, D. H. K., & Chan, R. C. K. (2016). Cross-cultural validation of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 in China. Psychological Assessment, 28(5), E88–E100. doi:10.1037/pas0000207.

Reise, S. P., & Waller, N. G. (2009). Item response theory and clinical measurement. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 5(5), 27–48. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153553.

Su, R., Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2014). The development and validation of the comprehensive inventory of thriving (CIT) and the brief inventory of thriving (BIT). Applied Psychology: Health and Well Being, 6(3), 251–279. doi:10.1111/aphw.12027.

Duan, W., Guan, Y., & Gan, F. (2016). Brief inventory of thriving: A comprehensive measurement of wellbeing. Chinese Sociological Dialogue, 1(1), 15–31. doi:10.1177/2397200916665230.

Stochl, J., Jones, P. B., Perez, J., Khandaker, G. M., Böhnke, J. R., & Croudace, T. J. (2016). Effects of ignoring clustered data structure in confirmatory factor analysis of ordered polytomous items: A simulation study based on PANSS. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 25(3), 205–219. doi:10.1002/mpr.1474.

Sorra, J. S., & Dyer, N. (2010). Multilevel psychometric properties of the AHRQ hospital survey on patient safety culture. BMC Health Services Research, 10, 199. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-10-199.

Hayes, A. F. (2006). A primer on multilevel modeling. Human Communication Research, 32(4), 385–410. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.2006.00281.x.

Janjua, N. Z., Khan, M. I., & Clemens, J. D. (2006). Estimates of intraclass correlation coefficient and design effect for surveys and cluster randomized trials on injection use in Pakistan and developing countries. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 11(12), 1832–1840. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01736.x.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3(4), 424–453. doi:10.1037//1082-989x.3.4.424.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. doi:10.1207/s15328007sem0902_5.

Duan, W., & Bu, H. (2017). Development and initial validation of a short three-dimensional inventory of character strengths. Quality of Life Research, 26(9), 2519–2531. doi:10.1007/s11136-017-1579-4.

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(3), 464–504. doi:10.1080/10705510701301834.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Nwebury Park, CA: Sage.

Niu, L., Qiu, Y., Luo, D., Chen, X., Wang, M., Pakenham, K. I., et al. (2016). Cross-culture validation of the HIV/AIDS stress scale: The development of a revised Chinese version. PloS ONE, 11(4), e0152990. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0152990.

Asparouhov, T., & Muthen, B. (2009). Exploratory structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 16(3), 397–438. doi:10.1080/10705510903008204.

Marsh, H. W., Liem, G. A. D., Martin, A. J., Morin, A. J. S., & Nagengast, B. (2011). Methodological measurement fruitfulness of exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM): New approaches to key substantive issues in motivation and engagement. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 29(4), 322–346. doi:10.1177/0734282911406657.

Mu, W., & Duan, W. (2017). Evaluating the construct validity of Stress Overload Scale-Short using exploratory structural equation modeling. Journal of Health Psychology. doi:10.1177/1359105317738322.

Wang, K., Cai, L., Qian, J., & Peng, J. (2014). Social support moderates stress effects on depression. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 8, 41. doi:10.1186/1752-4458-8-41.

Leidy, N. K., Revicki, D. A., & Geneste, B. (1999). Recommendations for evaluating the validity of quality of life claims for labeling and promotion. Value in Health, 2(2), 113–127. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4733.1999.02210.x.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 17CSH073); Wuhan University Humanities and Social Sciences Academic Development Program for Young Scholars “Sociology of Happiness and Positive Education” (Grant No. Whu2016019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Wenjie Duan and Wenlong Mu declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Appendix A

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Duan, W., Mu, W. Validation of a Chinese version of the stress overload scale-short and its use as a screening tool for mental health status. Qual Life Res 27, 411–421 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1721-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1721-3