Abstract

This paper employs bibliometric analysis to determine the scientific landscape of the influence of social transfers on female labor supply. We determine the scale and scope of the subject, as well as interconnections between various research fields, utilizing the Scopus database. The most significant areas of the research landscape are (i) labor, (ii) socioeconomics, and (iii) maternity, with multiple and complex connections between and among them. However, these areas are specific within given countries, and there is little collaboration between countries and researchers. This implies that the current state of research may not be sufficient to explain how, in fact, cash transfers affect human behavior in case of women’s labor. It is important for policymakers, particularly those governing non-homogeneous structures, such as the European Union, to avoid generalizing conclusions on the success or failure of a given policy in a given country. Research results demonstrate that the large scientific landscape investigated is divided into clusters which encompass ideas that are strongly interconnected outside their clusters. Nevertheless, the degree of collaboration between authors from different countries is low. A map of keywords reveals that certain aspects of the landscape may be associated only with a specific country or group of countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Various types of social transfers are important components of governance in modern society. They are widely used by states to increase fertility, reduce poverty, equalize gender status, and improve wellbeing. Such social transfers also have numerous side-effects, such as reduction in labor force participation and decreased independence among specific groups in society. Therefore, investigation of the effects of such transfers is of key importance for policymakers because it will enable them to achieve desired outcomes with the fewest possible drawbacks. Further, it is interesting, from a scientific point of view, to observe which mechanisms lie between the impulse created by a transfer and the effect(s) as observed by society or the economy. One of the key areas affected by transfers is women’s labor force participation, as determined by several factors, of which maternity is often listed as important (Chan and Liu 2018; Scarlato and d’Agostino 2019). Women’s labor force participation significantly influences society, family relations and culture (Beham et al. 2020; Bikketi et al. 2016; Ergas 2014; Lee and Zaidi 2020; Park and Goreham 2017; Urbina 2020). For this reason, it is crucial to increase such participation as it could lead to improvement in gender relations and increased female influence in various aspects of society, such as governance, policymaking, and the economy. This issue is important across all settings, including urban, suburban, and rural environments. However, the traditional gender roles that remain present in rural areas make study of this topic even more appropriate, considering the relationships between rural development/inclusive engagement and the level of local community participation in socio-economic life (Chmieliński et al. 2018).

Faced with the complexity of this topic, we start with a general question—what research patterns have emerged with respect to cash transfers as related to female labor supply? Our aim is to examine a map of interconnections and the flow of ideas between concepts encompassed in the literature on cash transfers and female labor supply through bibliometric analysis based on the Scopus database. The key part of the study is to visualize the landscape of research (e.g., trends, scientific output, and its role in the investigated field,) as well as its evolution over time with attention given to the scope of cooperation between researchers. As the subject of cash transfers is only one of the aspects influencing labor, we decided to compare this research area to a more general, i.e., “women labor,” research area.

Considering the multidimensionality of the investigated area, we hypothesize that the research landscape of this field is divided into clusters but that the clusters are interconnected with each other. We predict that multidisciplinary approaches and interconnections between different areas of science are required to reveal the dependencies and cause-effect connections of the phenomena. Consequently, we try to determine what direction should be adopted in analyzing this field in order to predict its effects on social policies. With a rapidly growing number of publications on women labor, we decided to use the Scopus database. Such an approach enables analysis of the research field on the basis of research papers’ metadata, such as keywords, authors affiliation, and journal titles. In this manner, a network based on the above data is constructed to identify clusters in the scientific landscape and the general direction of the research.

2 Literature review—women labor and cash transfers as a field of research

In the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, various programs were implemented to support families and parents with the goals of poverty reduction, equalization of social and economic standing of various society members, and the elimination of gender inequalities (Farah Quijano 2009; Garganta et al. 2017; Mariano 2020; OECD 2011). Such programs may be classified into four categories: (i) cash transfers depending on employment, or “CTE” (e.g. income-tax credit); (ii) cash transfers not depending on employment (universal cash transfers, or “UCT”); (iii) non-cash benefits for employees; and (iv) non-cash unconditional benefits. In this paper, we focus on cash transfers—CTE and UCT—although it should be noted that various studies show that benefits like longer maternity leave or the facilitation of childcare have great impact on the transformation of gender relations in the economy (Ennser-Jedenastik 2017). Cash transfers are also used to distinguish between different welfare system models, for example the Mediterranean model characterized by the prevalence of monetary transfers to families, as compared to the provision of social services (Ciavolino et al. 2016).

A significant portion of CTE benefits is focused on mothers and childcare, with the objectives of increasing the participation of women and improvement of child education and wellbeing. The observed effects included generally increased participation among women (Adireksombat 2010; Guest and Parr 2013; Sánchez-Mangas and Sánchez-Marcos 2008). This conclusion is particularly supported when there is a gap between the labor market potential for men and women, and female participation is low (Hernández Alemán et al. 2019). Moreover, when benefits support childcare, it not only allows for higher participation but also enables women to comply with employer requirements regarding quality of work (Press et al. 2006). It is particularly interesting that, among the different kinds of benefits, the results of cash transfers are more significant than for other measures (Haskins and Weidinger 2019). Although it could be assumed that CTE increases women participation, there is evidence that family allowances have an adverse effect on the number of hours worked by women in the EU countries (Schlenker 2015). Interestingly, lump-sum payments from CTE (mainly tax-credits that are paid once per year) could result in a reduction in the female labor supply (Yang 2018). This effect on women’s labor force participation is similar to that observed in the case of UCT, which means that over-generalizing the programs could result in misleading conclusions. Therefore, great care shall be taken in their evaluation. Programs like cash-for-care, wherein mothers receive money for staying a home with a child, can, essentially, be interpreted as women being employed by the state. Therefore, it is questionable (Österbacka and Räsänen 2021) that such measures decrease female participation in the labor market, as, in fact, women do perform a type of paid work in such cases. For this reason, we treat such transfers as work dependent (CTE) and not unconditional (UCT) in our research.

Contrary to CTE, with a broad literature on its positive effects, researchers observe that UCT programs could lead to a decrease in female participation, even if there are some type of conditions, as they do not directly relate to beneficiary employment (Garganta et al. 2017; Myck and Trzciński 2019; Naz 2004; Stadelmann-Steffen 2011; Yang 2018). It should be taken into account, however, that a significant portion of unemployed women face involuntary unemployment—particularly in the case of single mothers. For this group, financial support i crucial as it enables relief from poverty and a return to the labor force supply (Wu and Eamon 2011), as well as changing their lives to increase autonomy—and, therefore, allowing for better choice of work (Wiggan 2010). It is important to mention that, in the case of single parents, such benefits positively affect not only the parent but also their children, with respect to education and future wellbeing (Kalil and Ziol-Guest 2005).

It is tempting to expand the single-mother case to other situations where UCT are necessary to remove the beneficiary from poverty. However, doing so is difficult because, although mathematical models clearly estimate the scale of the labor effect under a given program, it cannot be concluded that the same effects can be transferred to another environment. Even beneficiaries in the same country, but in different parts of society (e.g., urban vs. rural), may have different responses to the same program (Giuliani and Duvander 2017). For example, a study of the UCT program in Poland proved that it had impact on the prevalence of poverty and income inequality (Chrzanowska and Landmesser 2017). Broad reviews of the programs in different countries, however, demonstrate that such findings are not homogeneous. Success of a given program may depend, for example, on the age of beneficiaries, the share of UCT/CTE spending as a portion of GDP, and the situation in labor markets—all with numerous exceptions (Bartosik 2020; Kabeer et al. 2012). Moreover, some researchers point out that UCT can have positive effect on women’s participation in the labor market due to increased self-esteem, ability to access credit, and improvement in quality of life (Akbulut 2016). When the subject resides outside of well situated economies, however, the traditional approach to the utility function, which exchanges work, leisure, and family duties may might not be applicable, as such “goods” are not inter-changeable (Mideros and O’Donoghue 2015). In such cases, the UCT may have positive, longitudinal effects on the female labor supply. This could be due not only to cultural and historical differences in heterogenic beneficiary groups, but also other differences in human cognitive processes, which are difficult to analyze using only statistical methods (Nisbett et al. 2001).

3 Materials and methods

The above literature review reveals the significantly wide scope of the subject. Numerous works from different areas must be reviewed to obtain a proper grasp on the factual state of the art. Therefore, we will apply bibliometric methods to analyze the cognitive structure of the subject (Leydesdorff 2011) and visualize the research landscape (Drupp et al. 2020) with respect to cash transfers and their effect on the female labor supply. In addition to standard analysis, we aim to focus on the relationship(s) between the elements of the subject in topological structures (Ganciu et al. 2016) to measure the flow and evolution of ideas (Hassan and Haddawy 2013). Among the different tools available to measure and visualize the relationship(s) between the subjects of our analysis (Klapka and Slaby 2018; Schatten 2013), we opted to rely on the visualization of similarities method through use of the VOSViewer software. This software is a tool used to visualize bibliometric networks. It enables clustering and mapping of interconnections between nodes (e.g., keywords, authors, affiliations). Its key feature is its ability to provide insight into the network structure, based on publication metadata available in science databases, such as Scopus, WoS, and others (van Eck and Waltman 2007).

3.1 Data sources

The subject of this paper is multidisciplinary, and the issue of women’s participation in the labor force is one that is widespread across different countries and cultures. Therefore, we chose Scopus as the bibliometric database for our study, based on its journal overlap with other sources (AlRyalat et al. 2019; Mongeon and Paul-Hus 2016), its usability for social sciences analysis (Palomo et al. 2017), as well as its wide range publications (Falagas et al. 2008) and significant collection of older records, which is important to our subject (Baas et al. 2020).

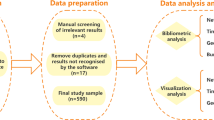

To start the search we used an initial query process, and obtained data adopting the PRISMA methodology in areas of screening, eligibility, and inclusion (Moher et al. 2009). As the automatic retrieval process of the literature records may result in inconsistent, duplicated, or irrelevant data, we based our process on PRISMA statement. It provides clarity for the literature filtering process and enables the reader to better understand how the authors achieved final input for analysis. The PRISMA was modified to work on records, rather than reports, to obtain a relevant list of data for the bibliometric analysis, instead of the systematic review. We ran multiple queries and reviewed the results. A significant portion of the bibliography records was found to be irrelevant due to common use of the certain terminology in the medical sciences. Therefore, the query was refined to exclude these articles by using ((EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "MEDI")). Some of the articles included in Scopus were identified as “in press” stage, and these were also excluded as they could potentially be withdrawn without publication (Oransky 2013). To do so, we used (EX-CLUDE (PUBSTAGE, "aip")).

Further screening revealed that some of the articles included terms other than our initial keywords relevant to the subject of women’s labor and cash transfers. Due to the wide structure of the Scopus database, the combination of words in abstracts can be the same for significantly different subjects. Therefore, we exchanged the “AND” operator for “W/[n]” (proximity of words within the range of [n] words), which significantly narrowed the results and limited them to the subject of women’s labor in relation to social transfers. The final query was adopted in the form: TITLE-ABS-KEY ((woman OR gender OR female) w/3 (work OR labor OR employment) AND ((transfer OR payment OR subsidy OR benefit) W/3 (cash OR social OR antipoverty) OR "tax credit" OR "child benefit" OR "rodzina 500" OR (family W/3 subsidy) OR (family W/3 benefit))) AND (EX-CLUDE (PUBSTAGE, "aip")) AND (EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "MEDI")). This resulted in 253 retrieved records. We wished to include as many records as possible in the analysis did not wish to lose the connection of the metadata with cash transfers and woman labor. During our preliminary queries, we observed that relevant keywords had to be located near to one another, as in a phrase. However, we could not limit our search to only to direct connections, such as “woman labor,” as, in many cases, authors used adjectives or other descriptive words separating our keywords, such as “woman engagement in labor”. Therefore, we decided to use “within” operator (“W”) to enhance our search. Different bibliographic search guidelines suggest that a “phrase” search should use a proximity parameter between 1 and 5. Therefore, we opted to use the middle number of 3 to avoid inclusion of too many irrelevant records.

From the 253 retrieved documents, 16 were assessed as ineligible for the study (mostly agriculture and medical articles), leaving 237 records for inclusion in the study. Figure 1 presents the flow of the retrieval process according to the modified PRISMA methodology (Page et al. 2021).

To observe the importance and scope of cash transfers in the literature regarding women’s labor, we also generated a larger set of data for general “women labor”—TI-TLE-ABS-KEY ("woman labor" OR "female labor" OR "woman work" OR "female work" OR "woman employment" OR "female employment")) AND (EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, "MEDI")) AND (EXCLUDE (PUBSTAGE, "aip"))—which yielded 9,064 results. This set was used as further background for our analysis. All the positions were accepted as eligible in order to observe the full range of subjects connected to female labor.

The bibliographic data obtained was then reviewed for harmonization of keywords used in the analysis, in turn, facilitating analysis of similarities between different publications. In this process, orthography mistakes were corrected for relevant keywords (mostly “womans”, “womens”), and the naming of keywords was unified (“female” instead of “women”, “labor” instead of “work”/“employment”).

3.2 Selection of indices

To address our hypothesis, we selected the following bibliographic indices:

-

(1)

General data regarding publications, countries and journals—to determine the landscape of the bibliography;

-

(2)

Co-operation network—to analyze collaboration in the field of women’s labor and cash transfers and to determine whether there are any central/key parts of the network (Acedo et al. 2006);

-

(3)

Keyword co-occurrence and evolution in time—to determine how the subject was approached, its dynamic, and to visualize progress in this field (Su and Lee 2010). Bibliographic sources (e.g., scientific publications) enable the observation of changes over longer time periods (Stek and van Geenhuizen 2015).

4 Results

This section presents results of the research landscape regarding the relationship(s) of cash transfers to women labor (WLCT), as compared to the entire field of women labor (WL).

5 Research landscape

The number of publications per year regarding women’s labor has increased over the last decade (Fig. 2), almost doubling the number published between 2001 and 2010. The same can be observed with respect to research connecting women’s labor and cash transfers. However, in relative numbers, cash transfers are referenced only in a small part of the “women labor” bibliography and that number has remained at an almost constant level of 2.8 to 2.9% since the year 2000.

The ten countries with the greatest number of contributions to the above research fields are presented in the Table 1. The main observation to be derived from this information is that most of the literature on the subject present in Scopus was created in highly-industrialized countries. There is a clear division between the United States/United Kingdom and other countries in terms of the number of relevant publications. In both subjects, there is similar country output, with slightly higher WLCT output in the cases of Germany and Australia. China’s absence from this table is noteworthy, as it is the source of the second largest number of publications in Scopus—with a total of 3.1 million, as compared to 5.5 million for the US and 1.6 million for the UK—between 2005 and 2014 (Erfanmanesh et al. 2017). We consider this observation as a potentially interesting subject for further study on women’s labor.

Table 2 illustrates the ten journals with the greatest number of publications on WL (left) and WLCT (right). Percentages represent the share of the given journal in all publications identified on WL and WLCT in Scopus. A high degree of heterogeneity among the sources on the subject can be observed, with a slightly higher concentration on the narrowed topic of cash transfers. Although Feminist Economics leads in WL and is in second place with respect to the number of articles addressing WLCT, the structure of the publications is divided evenly between sources, with only slight differences between them. Nevertheless, the socioeconomical part of the scientific community dominates among the top journals. Notably, only two journals are present for both subjects and only four journals from the top 10 on WL appears among all results found on the WLCT subject. We see this as implying the lack of a dominating publication that concentrates on the subject.

Regarding the WLCT subject (Table 4), it can be observed that the number of citations is significantly lower than those on WL (Table 3), which is understandable considering that WLCT is a more specific subject. Tables 3, 4 refer only to selected conclusions, which are the most relevant to the scope of our study. It can be observed that the top literature on these subjects results from observations regarding gender differences, in the case of WL, in the very specific subject of childcare. As a result, the combination of childcare and cash benefits can be perceived as the central axis of the literature on WLCT.

5.1 Cooperation network

5.1.1 International collaboration network

Figure 3 illustrates the international collaboration of authors of investigated papers according to each author’s country of affiliation). For WL, a set minimum of 50 documents and 187 citations per country were chosen as a threshold value. Twenty-seven countries achieved this value. The size of circles represents the number of publications affiliated with a particular country, whereas the thickness of the lines depicts the extent of collaboration. As it can be seen, the strongest links appear between the US and the UK, followed by Germany, which is consistent with the bibliography landscape described above. What can be observed is that Asian countries’ interest in women’s labor is rising, although, in this case, peripheral to the center of scientific production, and connect their research work to the US. At the same time, European countries combine their research efforts within the continent, leaving the UK aside.

This study applies the bibliographic coupling technique for citation mapping (Fig. 4). A couple is defined when two or more articles have the same reference. For the WL set, a threshold minimum of 200 citations were chosen. Out of 9064 publications, 76 achieved this value, and 58 of these were connected. Larger circles indicate the greater importance of a publication. Although countries’ collaboration discussed above is deemed to be at relatively low levels, with a single country in the dominant position, in the case of bibliography source usage, the collaborative network, as measured by coupling, is much more widespread and evenly distributed in case of WL. Such a coupling picture means that important ideas are being shared among a large part of the research community. For the WLCT, a threshold of 20 citations was set. Fifty documents fulfilled this limitation. Of these, 32 were connected to each other.

6 Keywords and their evolution

To analyze the subject and its evolution, maps of the co-occurrence of all keywords were generated (Fig. 5). The WL the map consists of 121 items with a threshold of 50 occurrences (out of total of 15,263 keywords). For WLCT, the map contains of 39 items with a threshold of 5 occurrences.

The pictures for WLCT (Fig. 5c) and WL (Fig. 5a) are similar in all significant aspects. It can be observed that researchers concentrate around three main areas: (i) labor—with gender as a key differentiator of the labor supply; (ii) socioeconomics—and the role of women’s employment in shaping relations with the society; and (iii) women and maternity—with the role women play in culture through child-rising.

For WL, the largest (i) cluster consists of 51 items (17 items for WLCT) and concentrates around female labor itself, with relation to the keywords: “women status”, “labor force”, “female”, “gender”, and “labor participation”. This cluster is also positioned geographically as it contains the keywords: “Europe”, “Western Europe”, “Turkey”, “Germany”, “France”, and “Sweden”. The (ii) cluster, including 36 items for WL (13 items for WLCT), consists mainly of social aspects, such as family, marriage, economic factors, population, and demography with geographical attribution to “developed country”. The last cluster (iii) containing 34 keywords for WL (9 for WLCT) applies to concepts of human, female, child, maternity, education, adult. Geographically it can be attributed to the United States – a keyword appearing often in this cluster.

From the timeline approach, we can see that research was concentrated purely on economic aspects at the beginning, i.e., treating women as unexplored reservoir of labor. With time, it moved to the social role played by female labor in the culture and family/work environment. Finally, in the most recent decade, researchers gave attention to gender inequalities and participation (Fig. 5b, d).

7 Discussion

There have been numerous studies on this broad and complex subject. The state of the research indicates various attempts to measure the impact of the women’s work phenomena, as well as to determine connections and relations between work and factors that affect it, such as fertility, housework, social security (Bennett 2005; Fuwa and Cohen 2007; Kalwij 2010). The greater portion of the literature is based on statistical methods (such as differences-in-differences, correlation analysis, microsimulation) and measures the impact of isolated factors (Aassve and Lappegård 2009; Kalb and Thoresen 2010; Schøne 2004). Significantly, a smaller portion of the publications attempts to reveal underlying mechanisms regarding how, in fact, the transfers affect the processes of increasing participation and closing the gender gap; or, in other words, how they affect the perception and decision-making processes of an individual and their close circumstances (such as family) that finally results in the choice to work. Tables and charts generated within our analysis prove that the subject is broad and relates to many important aspects of modern society, from fertility, though gender relations to economic status. This offers an answer to our research question regarding the research patterns on cash transfers and female labor supply. The key to our hypothesis presented in the introduction is the networks of connections between the subjects. It can be seen that this large scientific landscape is divided into clusters that encompass ideas strongly interconnected outside such clusters. Moreover, through investigation using a higher number of keywords, we can find the complexity of interconnections that indicate further important areas of study, such as medicine (although medical publications were removed), agriculture or ethnic studies. Links to agriculture confirm that the topic is important and should be considered further from the perspective of public policies toward rural development, especially regarding inclusive engagement of all inhabitants of rural areas and trends toward the increasing arrival of women in the agricultural sector (Fourcroy and Drejerska 2019).

Importantly, the degree of collaboration between countries is considered to be low. It is, therefore, difficult to judge whether conclusions drawn from one country may be applied in another. Moreover, the map of keywords reveals that some aspects of the topics are connected only within a specific country or group of countries. This may be a result of historical and social differences that significantly affect human behavior, which makes research on women’s labor even more complicated and its results less transferable between countries, although certain regional and local instruments of labor market policy may be applied for specific patterns characteristic for specific territories (Chrzanowska and Drejerska 2016). It is of importance for policymakers, particularly those governing non-homogenous structures like European Union, to avoid generalizing conclusions regarding the success or failure of a given policy in a given country. Understanding and predicting the effects of social transfers on women’s labor participation cannot be achieved only with quantitative approaches that measure the size of an effect and its correlation. The fact that different economies can react differently should be considered, as well as the fact that such reactions may be followed by different policy measures. For example, Ireland and Denmark ostensibly offered the ideal mix of favorable conditions for women in the labor market in 2007 but lost crucial elements of gender equality through cuts in public spending (e.g., for the early childhood supplement) (Castellano and Rocca 2017).

Despite broad modeling in the literature, the findings are largely insufficient to explain the mechanisms of any connections between the effects of cash transfers and women’s labor (Kabeer et al. 2012). Some of the research, therefore, employed interview techniques to either support the quantitative findings or to dive into the mechanisms and patterns between the observed numbers (Peterson and Engwall 2016; Ranganathan and Pedulla 2021). Such research reveals interesting aspects of the social interactions between various groups, such as a conflict between beneficiaries and “childless taxpayers” that is barely evident from the results of quantitative methods. Such aspects of shaping social relations are important for understanding the dynamics of modern society. The influence of aid programs affects not only welfare but could create long-lasting divisions in the society and, thereby, could lead to unexpected and unwilling clashes within the communities that may, in turn, fuel future crises or other events such as riots, strikes, collapse of social cooperation, or assaults on social minorities. Socio-demographic factors such as gender, as well as age, health status, and place of residence have also been examined by many authors as correlates of material deprivation (Dudek and Szczesny 2021). Therefore, the importance of grasping the mechanisms behind the influence of cash transfers on women’s work participation is a key factor in determining future social policies.

8 Concluding remarks

We emphasize the necessity of employing methods other than statistical tools for analysis of dependencies between cash transfers and women. The above analysis shows that social and gender clustering is one of the directions toward which current research is moving. This inevitably leads to differences in cognitive processes between genders, as well as social perception of policies adopted by the state. It would be worthwhile to study how adopted policies work over the long term, affecting not only female work but also the mechanisms influencing life satisfaction, self-confidence, health, and/or education. Therefore, in-depth interviews and surveys across society should be performed to establish the effects of cash transfer programs and to gather information for future development of social policy.

Our results further indicate the necessity of employing a multidisciplinary approach to explore connections between cash transfers and women’s labor. This is in line with our hypothesis and may be applied by academics in further research and to guide policymakers. Policymakers concentrating on only one aspect of the area, for example, the growth or decline of women’s participation in the labor force, may overlook the serious influence of cash transfers on female decision-making, position in the family, gender gap, rising ambitions, and stronger participation of women in social life. This is underscored by the fact that the lines of indirect cooperation between authors indicated in this paper by bibliographic coupling prove that the scientific community uses resources from different areas to understand the phenomena of factors affecting women’s participation in the labor force.

It must be noted that one of the primary limitations of this review is that its scope is bounded to a database that naturally uses English as primary its language and that—as was shown—most of the literature comes from the US and UK. There significant databases other than Scopus, such as Web of Science (Barnett et al. 2011) or PubMed, that could contain other important publications on the subject (Joshi 2016). Possible further work could extend the analysis more broadly to domestic literature than that which is included in the global bibliometric database. There is a wide range of programs that are broadly described in local languages. It would be particularly interesting to observe a given program within a local community, not only measuring it but also trying to explain underlying human decision-making processes related to the implementation of such program.

Another limitation that should be noted is our choice of the most popular keywords (for WL 121 out of 15,263) for the sake of transparency of the results. However, we ran the calculation for the higher number of keywords, and it did not only confirm our overall picture but emphasized further the complexity of the interconnections.

Data availability

Scopus—abstract and citation database (accessed August-December 2021).

References

Aassve, A., Lappegård, T.: Childcare cash benefits and fertility timing in Norway: allocations familiales et calendrier de la fécondité en Norvège. Eur. J. Popul. Rev. Eur. Démographie. 25, 67–88 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-008-9158-6

Acedo, F.J., Barroso, C., Casanueva, C., Galan, J.L.: Co-authorship in management and organizational studies: an empirical and network analysis*. J. Manag. Stud. 43, 957–983 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00625.x

Adireksombat, K.: The effects of the 1993 earned income tax credit expansion on the labor supply of unmarried women. Public Finance Rev. 38, 11–40 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1177/1091142109358626

Akbulut, H.: Gender disparities, labor force participation and transfer payment: what do macro data say? Rev. Econ. Perspect. 16, 375–387 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1515/revecp-2016-0021

AlRyalat, S.A.S., Malkawi, L.W., Momani, S.M.: Comparing bibliometric analysis using PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science databases. J. Vis. Exp. (2019). https://doi.org/10.3791/58494

Baas, J., Schotten, M., Plume, A., Côté, G., Karimi, R.: Scopus as a curated, high-quality bibliometric data source for academic research in quantitative science studies. Quant. Sci. Stud. 1, 377–386 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00019

Barnett, G., Huh, C., Kim, Y., Park, H.: Citations among Communication journals and other disciplines: a network analysis. Scientometrics 88, 449–469 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-011-0381-2

Bartosik, K.: The effect of the child cash benefits on female labour supply in OECD countries. Gospod. Nar. 303, 83–110 (2020). https://doi.org/10.33119/GN/125463

Baughman, R., DiNardi, D., Holtz-Eakin, D.: Productivity and wage effects of “family-friendly” fringe benefits. Int. J. Manpow. 24, 247–259 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1108/01437720310479723

Beham, B., Drobnič, S., Präg, P., Baierl, A., Lewis, S.: Work-to-family enrichment and gender inequalities in eight European countries. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 31, 589–610 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1355837

Bennett, F.: Gender implications of current social security reforms. Fisc. Stud. 23, 559–584 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5890.2002.tb00073.x

Bikketi, E., Ifejika Speranza, C., Bieri, S., Haller, T., Wiesmann, U.: Gendered division of labour and feminisation of responsibilities in Kenya; implications for development interventions. Gend. Place Cult. 23, 1432–1449 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2016.1204996

Blau, F.D., Kahn, L.M.: The gender wage gap: extent, trends, and explanations. J. Econ. Lit. 55, 789–865 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20160995

Brewster, K.L., Rindfuss, R.R.: Fertility and women’s employment in industrialized nations. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 26, 271–296 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.271

Brines, J.: Economic dependency, gender, and the division of labor at home. Am. J. Sociol. 100, 652–688 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1086/230577

Castellano, R., Rocca, A.: The dynamic of the gender gap in the European labour market in the years of economic crisis. Qual. Quant. 51, 1337–1357 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-016-0334-1

Chan, M.K., Liu, K.: Life-cycle and intergenerational effects of child care reforms. Quant. Econ. 9, 659–706 (2018). https://doi.org/10.3982/QE617

Chmieliński, P., Faccilongo, N., Fiore, M., La Sala, P.: Design and implementation of the Local Development Strategy: a case study of Polish and Italian Local Action Groups in 2007–2013. Stud. Agric. Econ. 120, 25–31 (2018). https://doi.org/10.7896/j.1726

Chrzanowska, M., Drejerska, N.: Unemployment in Polish regions from the perspective of spatial autocorrelation. Ann. Agric. Econ. Rural Dev. 103, 101–116 (2016)

Chrzanowska, M., Landmesser, J.: Simulation of ex ante effects of „Family 500+”program. Pr. Nauk. Uniw. Ekon. We Wrocławiu. (2017). https://doi.org/10.15611/pn.2017.468.04

Ciavolino, E., Sunna, C., De Pascali, P., Nitti, M.: Women resignation during maternal leave. Qual. Quant. 50, 1747–1763 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-015-0233-x

Clark, W.A.V., Withers, S.D.: Disentangling the interaction of migration, mobility, and labor-force participation. Environ. Plan. Econ. Space. 34, 923–945 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1068/a34216

Craig, L.: Does father care mean fathers share?: a comparison of how mothers and fathers in intact families spend time with children. Gend. Soc. 20, 259–281 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243205285212

Del Boca, D., Flinn, C., Wiswall, M.: Household choices and child development. Rev. Econ. Stud. 81, 137–185 (2014)

Drupp, M.A., Baumgärtner, S., Meyer, M., Quaas, M.F., von Wehrden, H.: Between Ostrom and Nordhaus: The research landscape of sustainability economics. Ecol. Econ. 172, 106620 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2020.106620

Dudek, H., Szczesny, W.: Multidimensional material deprivation in Poland: a focus on changes in 2015–2017. Qual. Quant. 55, 741–763 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-020-01024-3

Ekberg, J., Eriksson, R., Friebel, G.: Parental leave —A policy evaluation of the Swedish “Daddy-Month” reform. J. Public Econ. 97, 131–143 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2012.09.001

Ennser-Jedenastik, L.: How women’s political representation affects spending on family benefits. J. Soc. Policy. 46, 563–581 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279416000933

Erfanmanesh, M., Tahira, M., Abrizah, A.: The publication success of 102 nations in Scopus and the performance of their Scopus-indexed journals. Publ. Res. q. 33, 421–432 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-017-9540-5

Ergas, C.: Barriers to sustainability: gendered divisions of labor in Cuban urban agriculture. In: From Sustainable to Resilient Cities: Global Concerns and Urban Efforts. pp. 239–263. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley (2014)

Falagas, M.E., Pitsouni, E.I., Malietzis, G.A., Pappas, G.: Comparison of PubMed, Scopus, web of science, and Google Scholar: strengths and weaknesses. FASEB J. 22, 338–342 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.07-9492LSF

Farah Quijano, M.A.: Social policy for poor rural people in Colombia: reinforcing traditional gender roles and identities? Soc. Policy Adm. 43, 397–408 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2009.00670.x

Fernández, R., Fogli, A.: Culture: an empirical investigation of beliefs, work, and fertility. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 1, 146–177 (2009)

Fourcroy, E., Drejerska, N.: Agricultural employment transformation in France. Ann. Pol. Assoc. Agric. Agribus. Econ. 21, 59–68 (2019). https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0013.2070

Fuwa, M., Cohen, P.N.: Housework and social policy. Soc. Sci. Res. 36, 512–530 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2006.04.005

Galor, O., Weil, D.N.: The gender gap, fertility, and growth. Am. Econ. Rev. 86, 374–387 (1996)

Ganciu, A., Balestrieri, M., Cicalò, E.: Visualising the research on visual landscapes. Graph representation and network analysis of international bibliography on landscape. In: proceedings of the XIV International Forum Le Vie dei Mercanti (2016)

Garganta, S., Gasparini, L., Marchionni, M.: Cash transfers and female labor force participation: the case of AUH in Argentina. IZA J. Labor Policy. 6, 10 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40173-017-0089-x

Giuliani, G., Duvander, A.Z.: Cash-for-care policy in Sweden: An appraisal of its consequences on female employment: Cash-for-care policy in Sweden. Int. J. Soc. Welf. 26, 49–62 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12229

Goldin, C.: The quiet revolution that transformed women’s employment, education, and family, https://www.nber.org/papers/w11953, (2006)

Guest, R., Parr, N.: Family policy and couples’ labour supply: an empirical assessment. J. Popul. Econ. 26, 1631–1660 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-012-0421-0

Haskins, R., Weidinger, M.: The temporary assistance for needy families program: time for improvements. Ann. Am. Acad. Pol. Soc. Sci. 686, 286–309 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716219881628

Hassan, S.-U., Haddawy, P.: Measuring international knowledge flows and scholarly impact of scientific research. Scientometrics 94, 163–179 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-012-0786-6

Hernández Alemán, A., León, C.J., Márquez-Ramos, L.: The effect of the universal child care cash benefit on female labour supply in Spain. Estud. Econ. Apl. 35, 801 (2019). https://doi.org/10.25115/eea.v35i3.2508

Hill, M.A., King, E.: Women’s education and economic well-being. Fem. Econ. 1, 21–46 (1995)

Joshi, A.: Comparison between Scopus & ISI Web of Science. J. Glob. Values. 7, 11 (2016)

Kabeer, N., Piza, C., Taylor, L.: What are the economic impacts of conditional cash transfer programmes? A systematic review of the evidence. Technical report., (2012)

Kalb, G., Thoresen, T.O.: A comparison of family policy designs of Australia and Norway using microsimulation models. Rev. Econ. Househ. 8, 255–287 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-009-9076-3

Kalil, A., Ziol-Guest, K.M.: Single mothers’ employment dynamics and adolescent well-being. Child Dev. 76, 196–211 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00839.x

Kalwij, A.: The impact of family policy expenditure on fertility in western Europe. Demography 47, 503–519 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0104

Klapka, O., Slaby, A.: Visual analysis of search results in Scopus database. In: Méndez, E., Crestani, F., Ribeiro, C., David, G., Lopes, J.C. (eds.) Digital libraries for open knowledge, pp. 340–343. Springer International Publishing, Cham (2018)

Lee, K., Zaidi, A.: How policy configurations matter: a critical look into pro-natal policy in South Korea based on a gender and family framework. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy. 40, 589–606 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-12-2019-0260

Leydesdorff, L.: Bibliometrics/Citation networks. In: The Encyclopedia of Social Networks. pp. 72–74. Sage, Beverley Hills (2011)

London, A.S., Scott, E.K., Edin, K., Hunter, V.: Welfare reform, work-family tradeoffs, and child well-weing. Fam. Relat. 53, 148–158 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00005.x

Luci-Greulich, A., Thévenon, O.: The impact of family policies on fertility trends in developed countries. Eur. J. Popul. Rev. Eur. Démographie. 29, 387–416 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-013-9295-4

Mariano, S.: Conditional cash transfers, empowerment and female autonomy: care and paid work in the Bolsa Família programme. Brazil. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Policy. 40, 1491–1507 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-03-2020-0093

Mideros, A., O’Donoghue, C.: The effect of unconditional cash transfers on adult labour supply a unitary discrete choice model for the case of Ecuador. Basic Income Stud. (2015). https://doi.org/10.1515/bis-2014-0016

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D.G.: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 62, 1006–1012 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005

Mongeon, P., Paul-Hus, A.: The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: a comparative analysis. Scientometrics 106, 213–228 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5

Myck, M., Trzciński, K.: From partial to full universality: the family 500+ programme in Poland and its labor supply implications. Ifo DICE Rep. 17, 36–44 (2019)

Naz, G.: The impact of cash-benefit reform on parents? labour force participation. J. Popul. Econ. 17, 369–383 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-003-0157-y

Nisbett, R.E., Peng, K., Choi, I., Norenzayan, A.: Culture and systems of thought: holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychol. Rev. 108, 291–310 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.108.2.291

OECD: Doing better for families. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Paris (2011)

Oppenheimer, V.K.: Women’s employment and the gain to marriage: the specialization and trading model. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 23, 431–453 (1997)

Oransky, A.I.: Is an “article in press” “published?” A word about Elsevier’s withdrawal policy, https://retractionwatch.com/2013/02/25/is-an-article-in-press-published-a-word-about-elseviers-withdrawal-policy/, (2013)

Österbacka, E., Räsänen, T.: Back to work or stay at home? Family policies and maternal employment in Finland. J. Popul. Econ. (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-021-00843-4

Page, M.J., McKenzie, J.E., Bossuyt, P.M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T.C., Mulrow, C.D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J.M., Akl, E.A., Brennan, S.E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J.M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M.M., Li, T., Loder, E.W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L.A., Stewart, L.A., Thomas, J., Tricco, A.C., Welch, V.A., Whiting, P., Moher, D.: The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 10, 89 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

Palomo, J., Figueroa-Domecq, C., Laguna, P.: Women, peace and security state-of-art: a bibliometric analysis in social sciences based on SCOPUS database. Scientometrics 113, 123–148 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2484-x

Park, D.-B., Goreham, G.A.: Changes in rural Korean couples’ decision-making patterns: a longitudinal study. Asian Women. 33, 1–23 (2017)

Peterson, H., Engwall, K.: Missing out on the parenthood bonus? Voluntarily childless in a “child-friendly” society. J. Fam. Econ. Issues. 37, 540–552 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-015-9474-z

Press, J.E., Fagan, J., Laughlin, L.: Taking pressure off families: child-care subsidies lessen mothers’ work-hour problems. J. Marriage Fam. 68, 155–171 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00240.x

Ranganathan, A., Pedulla, D.S.: Work-family programs and nonwork networks: within-group inequality, network activation, and labor market attachment. Organ. Sci. 32, 315–333 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2020.1391

Sánchez-Mangas, R., Sánchez-Marcos, V.: Balancing family and work: the effect of cash benefits for working mothers. Labour Econ. 15, 1127–1142 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2007.10.002

Scandura, T.A., Lankau, M.J.: Relationships of gender, family responsibility and flexible work hours to organizational commitment and job satisfaction. J. Organ. Behav. 18, 377–391 (1997). https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199707)18:4%3c377::AID-JOB807%3e3.0.CO;2-1

Scarlato, M., d’Agostino, G.: Cash transfers, labor supply, and gender inequality: evidence from South Africa. Fem. Econ. 25, 159–184 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2019.1648850

Schatten, M.: What do Croatian scientist write about ? A social and conceptual network analysis of the Croatian scientific bibliography. Interdiscip. Descr. Complex Syst. 11, 190–208 (2013). https://doi.org/10.7906/indecs.11.2.2

Schlenker, E.: The labour supply of women in STEM. IZA J. Eur. Labor Stud. 4, 12 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40174-015-0034-1

Schøne, P.: Labour supply effects of a cash-for-care subsidy. Popul. Econ. 17, 703–727 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-003-0176-8

Simkhada, B., van Teijlingen, E.R., Porter, M., Simkhada, P.: Factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care in developing countries: systematic review of the literature. J. Adv. Nurs. 61, 244–260 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04532.x

Stadelmann-Steffen, I.: Dimensions of family policy and female labor market participation: analyzing group-specific policy effects. Governance 24, 331–357 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2011.01521.x

Stek, P.E., van Geenhuizen, M.: Mapping innovation in the global photovoltaic industry: a bibliometric approach to cluster identification and analysis. In: ERSA 55th Congress, World Renaissance: Changing roles for people and places, Lisbon, Port. 25–28 Aug 2015. 30 (2015)

Su, H.-N., Lee, P.-C.: Mapping knowledge structure by keyword co-occurrence: a first look at journal papers in Technology Foresight. Scientometrics 85, 65–79 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-010-0259-8

Urbina, D.R.: In the hands of women: conditional cash transfers and household dynamics. J. Marriage Fam. 82, 1571–1586 (2020)

van Eck, N.J., Waltman, L.: VOS: a new method for visualizing similarities between objects. In: Decker, R., Lenz, H.-J. (eds.) Advances in data analysis, pp. 299–306. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg (2007)

Wang, H., Li, R., Tsai, C.-L.: Tuning parameter selectors for the smoothly clipped absolute deviation method. Biometrika 94, 553–568 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/asm053

Wiggan, J.: Managing time: the integration of caring and paid work by low-income families and the role of the UK’s tax credit system. Policy Stud. 31, 631–645 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2010.511527

Wu, C.-F., Eamon, M.K.: Patterns and correlates of involuntary unemployment and underemployment in single-mother families. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 33, 820–828 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.12.003

Yang, H.-S.: Social security dependent benefits, net payroll tax, and married women’s labor supply: social security dependent benefit and labor supply. Contemp. Econ. Policy 36, 381–393 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1111/coep.12250

Yavas, U., Babakus, E., Karatepe, O.M.: Attitudinal and behavioral consequences of work-family conflict and family-work conflict: does gender matter? Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 19, 7–31 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1108/09564230810855699

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Investigation, resources, and data curation were proceeded by Jakub Wysoczański. The first draft of the manuscript was written by all authors and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Drejerska, N., Chrzanowska, M. & Wysoczański, J. Cash transfers and female labor supply—how public policy matters? A bibliometric analysis of research patterns. Qual Quant 57, 5381–5402 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-022-01609-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-022-01609-0