Abstract

The search for happiness, understood as an inner and personal attitude that goes beyond mere satisfaction, is one of the aims of tourists’ co-creation of value. To date, few studies have analysed the importance of people’s moral principles in the co-creation of tourist value. Moral emotions play an essential role in this process. In this study, 12 tourism managers within administration, 28 hotel managers and 24 travel agencies actively participated in defining the indicators selected to measure how the co-creation of value from five Spanish towns affected customers’ happiness. Moreover, 444 tourists participated in the study. The PLS-SEM technique was used to examine the data obtained. Results show that the co-creation of value contributes to the happiness of the tourist. Of particular significance is the influence of customers’ co-creation of value on customer happiness. Additionally, the predictive capacity of the model is replicable to other tourist destinations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent decades, co-creation behaviours in the development of a product or provision of a service have gained considerable popularity in the tourism sector (Kim et al. 1994; Robina-Ramirez et al. 2022; Ruhanen et al. 2021). Strategies that analyse customer satisfaction are focused on the role played by organisations and destinations in providing the service or making the product (Neuhofer et al. 2013, Robina-Ramírez et al. 2021a, b; Ho et al. 2021). This role is enriched from the potential decision-making and motivating power of the tourist who adds value to the product or service (Prebensen et al. 2013; Tan et al. 2016); indeed, the client goes from being a mere recipient of a service to a co-creator of value (Yi and Gong 2013; Zayed et al. 2022).

In this value creation process, participatory and interactive strategies are essential to improve customer satisfaction and the final product (Cerdan Chiscano and Darcy 2021; Robina-Ramírez et al. 2021a, b; Ho et al. 2021). The client cooperates with the product provider or service provider not only for personal satisfaction but to improve the final product or service (Xie et al. 2020; Núñez-Barriopedro et al. 2021), propose changes in its production process (Gebauer et al. 2010), better position the product in the market (Fujioka 2009), provide experience (Gentile et al. 2007), evaluate the type of service it provides (Sánchez-Hernández et al. 2020; Vargo et al. 2008) and measure the potential value it is capable of providing (Ueda et al. 2008).

In the last decade, various studies have emerged that relate the creation of value and happiness (Chiu et al. 2014; Pera and Viglia 2015; Sanjuán and Magallares 2014; Ravina-Ripoll et al. 2019a, b, 2021a, b; Hughes and Vafeas 2021). The customer can choose to be happy by participating in the value co-creation process, without having to be completely satisfied with the result of the exchange of products and services. While satisfaction stems mainly from a positive result that comes from outside the person (product or service), happiness is something more internal and personal based on the enjoyment or pleasure received from goods or services (Núñez-Barriopedro et al. 2020; Ravina-Ripoll et al. 2019a, b, 2021a, b; Waterman 2008). However, the literature has evidenced the importance of the co-creation of value for happiness (Ravina-Ripoll et al. 2021a, b).

In the face of the hedonistic happiness, another type of “transcendent” happiness has recently emerged, connected to values and moral principles (Robina and Pulido 2018; Robina-Ramírez et al. 2021c). Transcendence is a horizontal, interdisciplinar, and multi-lateral concept (Weathers et al. 2016; Cosimato et al. 2021). Some researchers link it to the effort to explore the sacred, while others associate it with the development of personal qualities and values (Robina Ramírez and Fernández Portillo 2020). Both goes beyond the interest humans place in superficial and material objects (Zinnbauer and Camerota 2004; Waterman 2008). For the European Institute of Spirituality in Economy and Society (2014), the meaning of happiness match with the sacred and the meaning of like in search to behavioural excellency (European Forum SPES 2014).

Although there are some studies that address the relationship between transcendence and tourism (Buzinde 2020; Haldorai et al. 2020), as far as our research goes, the meaning of happiness as the search for the deep meaning of life based on the development of personal qualities and values has not yet been addressed in the co-creation of value scenario.

This paper analyses the role played by “transcendent” happiness in the co-creation of tourists in the region of Extremadura, based on the Attraction-Selection-Attrition (ASA) theory. People are attracted to an organisation (Salter 2006; Schneider 1987) or a type of experience with which they identify. The purpose of these is not so much simply searching for personal satisfaction but to be able to explore ways to grow and develop personally in a way that complements the values of the destination (historical, art and heritage, nature, leisure, religious, gastronomic).

The importance of this study is twofold. First, this document fills an important research gap by measuring the explanatory and predictive effect of the factors that influence the process of co-creation of value of the tourist service and its influence on the “transcendent” happiness of the tourist. Second, this study highlights the importance of developing moral emotions, which go beyond the mere enjoyment or pleasure of the tourist.

The document is structured as follows. First, the theoretical framework addresses the relationship between the co-creation of value and happiness, the role that emotions play in happiness, and the meaning of moral emotions and authenticity. Then, the research methodology and results are presented. Finally, a discussion is conducted and conclusions are drawn.

2 Theoretical framework

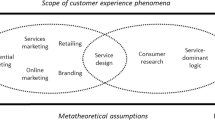

2.1 Co-creation of value and happiness

The literature recognises that co-creation behaviour provides a state of happiness in the client that affects the quality of the company's service (Ennew and Binks 1999; Cuesta-Valiño et al. 2021) and that makes them more proactive and collaborative (Aarikka-Stenroos and Jaakkola 2012; Singagerda 2020), thus strengthening customers’ commitment as a co-creator of the service (Pera and Viglia 2015; Hsieh et al. 2018). Several studies have analysed the relationship between the co-creation of the service and happiness when improving the service (Frey and Stutzer 2010; Hsieh et al. 2018; Cuesta-Valiño et al. 2021; Ravina-Ripoll et al. 2021a, b; Hughes and Vafeas 2021; Cosimato et al. 2021). This commitment is based on their values and beliefs regardless of the satisfaction experienced by the tourist. The transactional concept of merely fulfilling client-supplier expectations is replaced by the concept of voluntary donation to the service provider.

The first factor of value co-creation is sharing information (Yi and Gong 2013). The altruistic, donation attitude of the client leads them to analyse how information on the destination can improve (Dong et al. 2008) based on responsible behaviour (Ennew and Binks 1999). Feedback can be “communicative” when the client spontaneously decides to voluntarily help other clients to solve a problem during the provision of the service (Yi and Gong 2013) or the “recommendation” of the destination to third parties (Garma and Bove 2011; Groth et al. 2004). This recommendation can help promote the company through comments on platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, blogs, etc., all of which provide positive approach to what is customer happiness (Garma and Bove 2011).

This double relationship must be presided over by actions of courtesy, kindness, and respect (Kelley et al. 1990). We speak of a civic co-creation behaviour that provides additional value to the company and a feeling of happiness (Groth 2005). The client-provider courtesy also involves improving the willingness of tourists to accept failures in the provision of the service by the provider such as delays and equipment shortages (Lengnick-Hall et al. 2000). The more positive, harmonious, and pleasant the social environment, the more likely customers are to participate in co-creating value (Lengnick-Hall et al. 2000).

2.2 The role emotions play in the pursuit of happiness

Most scholars are of the opinion that happiness can only be explained and measured based on certain practices that lead to it (Hofmann 2013) or from the development of positive emotions (Shiota et al. 2017; Núñez-Barriopedro et al. 2021). There are three emotional attributes commonly used in psychology: (1) affect, (2) mood, and (3) emotion (Batson et al. 1992). While “affect” and “mood” refer more to non- reflective feelings or personality aspects that are difficult to identify (Fridja 1986), “emotions” can be measured from personal experience; this is a feeling that comes from a specific stimulus (Barrett et al. 2009). According to Tamir et al. (2017), the more emotions we experience, the happier we would be. In the value co-creation process, the generation of emotions depends on the type of behaviour orientation, specifically whether it is egocentric (Ralston et al. 2014) or altruistic (Bove et al. 2009; Groth 2005). While egocentrics are more oriented towards personal well-being, collectivists prioritise the well-being of the group (Snyder and Omoto 2008). Although in both there may be a desire to add value to the product or service, the latter incorporate a typology of emotions absent among those with an egocentric orientation (Sanjuán and Magallares 2014). However, the altruistic orientation generates typologies of "social emotion". Then, feelings are established towards a positive relationship with another person or interest group, developing feelings of justice towards others (Hareli and Rafaeli 2008). According to Rudd et al. (2012), these positive emotions affect the pro-social behaviour of individuals based on feelings of unity and connection with others.

From that connection, a reaction of awe, gratitude, and compassion can be generated in individuals (Stellar et al. 2017). “Awe” is meant as overwhelm positive feelings towards something or someone designed to be admired (Keltner and Haidt 2003), that feeling of admiration could thereafter inspire the transformation of attitudes. “Gratitude” is usually triggered when you experience a feeling of debt toward others who provides you an astonishing service (Büssing et al. 2018). It positively influence your personal attitudes and feeling to return unexpected gift received (Chang et al. 2021). “Compassion” arouses feelings to suffer with someone who deserve to be attended for the potential damage caused (Goetz et al. 2010); among these feelings are sympathy and pity (Goetz et al. 2010), anger and shame (Fridja 1986) or sadness and guilt (Böhm 2003). These feelings may be caused by deceitful or fraudulent behaviours or falsehoods in the provision of services to clients (Brown et al. 1999). It triggers affections, or afflictions (Wispé 1991) to diminish sometimes devastating situations (Markowitz and Rosner 2013). Subsequently, awe, gratitude, and compassion can influence the behaviour of co-creation value in tourists (Pera and Viglia 2015).

2.3 Morality and beliefs in the pursuit of happiness

The last few decades have provides us new research in happiness based on the measurement of emotions and affects (Helliwell et al. 2020). As a results, a series of methods have been developed to measure new approach to the feelings individuals experiment with life satisfaction and happiness (Hektner et al. 2007). This way of measuring and understanding happiness seeks to provide accurate descriptions of the psychological states that people experience but leaves aside the role played by morality (Intelisano et al. 2020).

In the work entitled “True happiness: The role of morality in the folk concept of happiness”, Phillips et al. (2017) incorporate their moral values and beliefs. Whereas it is commonly understood happiness as a feeling good, it also connected to the moral approach of being good (Aristotle, 340 BC/2002; Foot 2001; Intelisano et al. 2020), not is it solely linked to the social improvement of a group but rather to the moral well-being of society in general (Haidt 2003). Moral emotions generate a greater state of happiness when the moral order is based on compliance with principles that must be respected (Malti et al. 2014) such as: “do good and avoid evil” or “treat others as you would like to be treated” (Grisez et al. 1987). Co-creation behaviours alongside the inclusion of moral emotions allow us not only to measure the value of building a more just and equitable society (Johnson and Manoli 2011) but to develop experiences and challenges to better transform society into a habitable place to live (Robina-Ramírez and Medina-Merodio 2019).

2.4 Authenticity in co-creation behaviours in tourism

Emotions guided by moral principles highlight the value of authenticity as an upward resource. Examining the services that drive tourists' co-creation behaviours, we find that authenticity plays a key role in moderating the relationships between co-creation behaviour and memorable tourism experiences (Vargo and Lusch 2004). Fields et al. defined the co-creation of tourist experiences as the sum of psychological events experienced by tourists built on the support of moral principles that exude authenticity and the improvement of civic tourist behaviour (Bartels and Pizarro 2011; Groth 2005). Although the relationship between co-creation and authenticity was validated by Cubillas et al., it gained little interest in the scientific community. However, the effect of civic behaviours on value co-creation experiences improves the habitability of the tourist in the destination (Yi and Gong 2008) through the human and moral character of the person (Zatori et al. 2018). In addition, civic and citizenship-oriented behaviours can bring a high degree of happiness to tourists (Yi et al. 2011).

According to that knowledge and authors, the following hypothesis can be drawn (see Table 1):

H1

Customer co-creation of value (CCV) capacity influences customer happiness (CF).

H2

The development of individual and social emotions (SIE) influences the customer's ability to co-create value (CCV).

H3

The development of moral emotions (ME) influences the development of individual and social emotions (SIE).

H4

The development of moral emotions (ME) influences authenticity in behaviour (A).

H5

Authenticity in behaviour (A) influences the development of individual and social emotions (SIE).

H6

The development of moral emotions (ME) influences the customer’s ability to co-create value (CCV).

H7

Authenticity in behaviour (A) influences the customer’s co-creation of value (CCV).

3 Methodology

3.1 Selection of indicators

From the book “Focus groups as a tourism research tool: The focus group as a tool for tourism research”, Sánchez-Oro Sánchez and Robina Ramírez (2020) explain that focus groups have re-emerged as a popular technique to collect qualitative data among a wide range of academic sectors. In the tourism sector, such methods are well applied to indicators of the co-creation of value and happiness. Tourism managers in administration and tourism companies have participated in the definition of indicators. Utilising emails, the scientific proposals of the research were explained to 24 tourism managers from the local provincial and regional administration, as well as to 32 hotel managers and 28 professionals from travel agencies. Finally, 12 tourism managers from the administration sector, 28 hotel managers, and 24 travel agencies participated (see Table 2).

Two sessions were held with the participants; the first was conducted in the second week of January 2022. The objectives of the work and the main concepts were explained: co-creation, moral emotions, authenticity, and happiness. For two hours, we received suggestions about how to adapt these concepts to the tourism sector. Then, we defined several constructs: Customer Happiness (CH), Co-creation of customer value (CCV), Social-Individual Emotions (SIE), Authenticity (A), and Moral Emotions (ME). During the fourth week of January, two focus groups were held through the Zoom online platform to select the indicators for each of the latent variables extracted from the literature review. In the first meeting, the concept of each of the indicators extracted from the literature review was studied. During the second meeting, indicators were reviewed and modified, and the final list of indicators was presented (see Table 3). From the items, the questions valued by the tourists were developed (Teye et al. 2002). Additionally, the questionnaires were approved through the "ethical authorisation" process, document 039–19 reported by the University of Extremadura.

3.2 Survey and demographic variables

Extremadura region was chosen due to tourism is one of the main industries in Spain compared to regional GDP. According to Sánchez-Martín and Rengifo-Gallego (2019) Extremadura is the poorest region in Spain where tourism have a significant importance in the region compared to other regions with highest regional GDP.

As the indicators of the co-creation of value and happiness were defined in January 2022 by tourism managers from the local provincial and regional administration, as well as hotel managers and professionals from travel agencies, during February and March the survey were released through those tourism groups. The research teamwork decided to choose those months due to the availability of the managers and travel agencies to be responsible of launching the survey and collecting the data. At the end of every week each tourism group were sending the data to the research teamwork in order to store and organize the sample. Questionnaire were designed to obtain all the data without leaving empty boxes, response to the data was compulsory for the tourism industry. According to the data provided by local provincial and regional administration thirty two thousands, one hundreds fifty nine tourist were received during February and March in the regional territory of Extremadura.

In relation to demographic variables, 56% were women, almost 60% of the population was under 45 years of age, 63% were currently working, and 65% had studied at high school or university (see Table 4).

3.3 PLS-SEM data methods

We used the multivariate PLS technique to process the information obtained from the questionnaires. PLS-SEM is well suited exploratory methodology to small sample sizes based on normal data distribution and is well adapted for making predictions by researchers (Chin and Newsted 1999). To generate the statistical model, the PLS (Partial Least Squares). SmartPLS 3 Version 26 technique was applied. This version is especially recommended for composite site models (Rigdon et al. 2017). PLS-SEM links constructs and indicators determined in the measurement and the structural explanatory model (Hair et al. 2011), through its proof of validity and reliability (Dijkstra and Henseler 2015). In this case, the type of elements used are considered reflective. It means the indicators are highly correlated and interchangeable, they are reflective and their reliability and validity should be thoroughly examined (Haenlein and Kaplan 2004; Wong 2013). Likewise, this technique is ideal in social science analysis (Fornell and Bookstein 1982) thanks to the precision of its predictions; this means that the model could be replicated in other settings (Carmines and Zeller 1979).

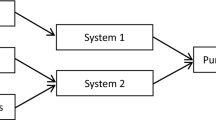

3.4 Hypothesis and model

Seven working hypotheses have been developed:

H1

Customer co-creation of value (CCV) capacity influences customer happiness (CH).

H2

The development of individual and social emotions (SIE) influences the customer's ability to co-create value (CCV).

H3

The development of moral emotions (ME) influences the development of individual and social emotions (SIE).

H4

The development of moral emotions (ME) influences authenticity in behaviour (A).

H5

Authenticity in behaviour (A) influences the development of individual and social emotions (SIE).

H6

The development of moral emotions (ME) influences the customer’s ability to co-create value (CCV).

H7

Authenticity in behaviour (A) influences the customer’s co-creation of value (CCV) (Fig. 1).

4 Results

4.1 Measurement model results

In this section, we analyse the model’s reliability and validity (Hair et al. 2016). The first one analyses simple correlations of the measurements with their respective latent variables (≥ 0.7 was accepted. See Table 5). Table 6 shows the main parameters. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used as a reliability index of the latent variables. In addition, the composite reliability was calculated. To measure validity, the mean variance extracted (AVE), known as “convergent validity” (accepted > 0.5), was evaluated (see Table 6). The discriminant validity was verified using the Fornell-Larcker criterion (Fornell and Bookstein 1982). This was accepted as the square root of the AVE of each item exceeded the correlations with the other latent variables.

Furthermore, according to Henseler et al. (2015), the lack of discriminant validity is the best technique to detect the lack of lack of discriminant validity, known as heterotrait- monotrait ratio (HTMT). Henseler et al. (2015) proposed testing the correlations between variables using the HTMT parameter. Since all values are < 0.90, as observed in Table 8, this condition is accepted (Henseler 2017). Table 7 reveals that the HTMT ratios for each pair of factors was < 0.90 (Henseler 2017) (Table 8).

4.2 Structural model results

PLS-SEM aims to maximize the amount of variance explained through the coefficient of determination (R2). The structural evaluation of the model also analyses the predictive relevance (Q2), the size and the significance of the standardized regression coefficients or path coefficients. The basic algorithm of the PLS follows a two-step approach, the first one refers to the iterative estimation of the scores of the latent variables, and the second step refers to the final estimation of the weights, loads and path coefficients by means of the estimation of ordinary least squares (p value > 0.05) (Henseler et al. 2015) (Table 9).

According to Henser et al. (2016), the best fit criterion for the global model is residual root mean square normalization (SRMR) (Hu and Bentler 1998, 1999). A model with an adequate fit is considered when the values are less than 0.08. Therefore, a value of 0 for SRMR would indicate a perfect fit and, in general, an SRMR value less than 0.05 indicates an acceptable fit (Byrne 2008). A recent simulation study shows that a correctly specified model implies SRMR values greater than 0.06 (Henseler et al. 2016). SRMR is 0.079, so the model is appropriate to the empirical data used (Hair et al. 2016).

The R2 values (see Table 10) obtained for the investigation led to the following conclusions: 0.67 = “Substantial”, 0.33 = “Moderate”, and 0.19 = “Weak” (Chin 1998). The result obtained for the main dependent variable in the intention to use model (DCM) was R2 = 45.7%. Therefore, the evidence shows that the presented model has a moderate predictive capacity. This explains why both moral emotions (ME) and individual and social emotions (SIE) as authenticity (A) affect the co-creation of value (CCV), all of which contribute to improving customer happiness (CH).

From these data, it is clear that the model has predictive capacity (Chin 1998). Following Stone–Geisser (Q2) (Stone 1977; Geisser 1974), all endogenous constructions comply with Q2 > 0, as can be seen in Table 10. Hair et al. (2016) also establish values of 0.02 as small, values of 0.15 as medium, and values of 0.35 as large in their predictive validity of the model. In our case, the values of A, CCV, and SIE exceed the maximum threshold, which indicates a high predictive relevance, while CH has an intermediate predictive relevance.

5 Discussion

This research analyses the role played by "transcendent" happiness in the co-creation of tourists in the region of Extremadura, based on the ASA theory. People are attracted to an organisation, initiative, service, or product with which they identify (Salter 2006; Schneider 1987). Furthermore, travellers have different motivations to co-create value in a product or service (Cerdan Chiscano and Darcy 2021). In participatory and interactive processes, tourists contact suppliers to improve the final product as well as to provide their experiences, as indicated in Table 10.

According to the results of the study, it is interesting to observe the high percentage of tourists who have provided some type of feedback to the supplier (79%), mainly through social networks. Within that percentage, 29% have purely pleasurable motivations and do not ask other questions, whilst 50% are aligned with the search for development as a person through tourist attractions (Robina-Ramírez and Cotano-Olivera 2020; Robina-Ramírez et al. 2021c). These results show a search for “transcendent” happiness well above a merely "hedonistic" happiness. This becomes an essential aspect for the tourist suppliers when designing their strategy to interact with customers.

The model confirms the model initially proposed in the focus groups to develop customer co-creation of value (CCV; R2 = 0.510). It is based on the development of individual and social emotions (SIE; R2 = 0.553), an authenticity in behaviour (A; R2 = 0.413), and moral emotions. This co-creation of value contributes to the happiness of the tourist (CH; R2 = 0.457).

Similarly, the predictive capacity of the dependent variable (CH) [Q2 = 0.242] provides reasons to apply this model to other tourist destinations with similar socioeconomic conditions. It should be noted that all hypotheses are accepted. Of particular significance is the influence of the customer co-creation of value on customer happiness [H1: CCV → HC: β = 0.676; t = 26,849]. Tourists confirm that the co-creation behaviour provides a state of happiness in proactive customers and collaborators (Aarikka-Stenroos and Jaakkola 2012; Ennew and Binks 1999), strengthening their commitment and responsibility to transmit information to the provider (Pera and Viglia 2015).

We also highlight the fact that H4 (ME → A: β = 0.643; t = 21.723) and H5 (ME → A: β = 0.526; t = 12.932) both show a new dimension of the co-creation of value in which the transmission of customer information not only seeks to improve the service but also to contribute to developing a better world based on the application of moral principles (Grisez et al. 1987). The concept of happiness therefore moves from a merely hedonistic vision of “feeling good” to a search for personal and moral development of the person (Aristotle, 340 BC/2002; Foot 2001).

6 Conclusions

Several important conclusions stand out from this study. Firstly, the study demonstrates a high percentage of tourists who understand happiness not as a mere pleasure (Waterman 2008) but as a value that transcends and develops the person. According to the data extracted from the study carried out, tourism is not understood as a throwaway product, but as a cultural or leisure activity that contributes to the development of people. Traveling is more than discovering corners of the world for just gastronomy or curiosity; instead, traveling is understood as personally developing through touristic experiences. It is about developing experiences and services that improve society so that the world is a better place (Robina-Ramírez and Medina-Merodio 2019). Tourism understood as an experience that improves the quality of life of tourists beyond the moment in which the service is provided through moral experiences.

Secondly, moral experiences play a key role in providing information to suppliers. Tourists are not only satisfied by providing information to improve the service; they also seek civic attitudes and better citizenship to build a more habitable world. This notion of civic attitude in the co-creation of value is aligned with transcendent happiness. The client goes from an altruistic attitude (Dong et al. 2008) to a moral one to improve society (Johnson and Manoli 2011). A tourist's experience of co-creating value generates behaviour that is not so much egocentric (Ralston et al. 2014) as altruistic (Bove et al. 2009; Groth 2005), which ends up feeling justified (Hareli and Rafaeli 2008), united, and connected with others (Moisander and Pesonen 2002; Rudd et al. 2012). Then, the authenticity is highlighted as an essential factor in the tourist's co-creation process. The information generated by the tourist must be truthful and built on the moral principles of the people. This attitude not only generates happiness in the tourist but also helps to develop exemplary civic behaviour for other people and for the company (Bartels and Pizarro 2011; Groth 2005).

Therefore, the model proposes moving from the transactional concept of the mere fulfillment of client–supplier expectations to the concept of voluntarily donating to the service provider, which provides greater customer happiness (Pera and Viglia 2015). The happiness of the client to feel useful, makes all this part of the service. It confers a high degree of autonomy and personality to the service (Cerdan Chiscano and Darcy 2021). A totally personalized service is guaranteed because each client is different from another. Their way of participating and co-creating value is also different, even the same client at different times (Yi and Gong 2013). The result is a unique, personal and unrepeatable service.

The main limitations of our study are related to conducting in-depth focus groups and surveys. The interviews were carried out through virtual meetings and telephone calls.

All study participants are from Extremadura, but future studies can continue with the same methodology in other regions or countries in order to compare results.

In addition, the mediation between the Model Social Individual Emotions and Authenticity towards the relationship between Moral Emotions and Co-creation will be considered in a second paper.

References

Aarikka-Stenroos, L., Jaakkola, E.: Value co-creation in knowledge intensive business services: a dyadic perspective on the joint problem-solving process. Ind. Mark. Manag. 41(1), 15–26 (2012)

Aristotle: Nicomachean ethics. In: Broadie, S., Rowe, C. (eds.) (2002/340 BCE)

Barrett, L.F., Gendron, M., Huang, Y.M.: Do discrete emotions exist? Philos. Psychol. 22(4), 427–437 (2009)

Bartels, D.M., Pizarro, D.A.: The mismeasure of morals: antisocial personality traits predict utilitarian responses to moral dilemmas. Cognition 121(1), 154–161 (2011)

Bastian, B., Kuppens, P., De Roover, K., Diener, E.: Is valuing positive emotion associated with life satisfaction? Emotion 14, 639–645 (2014)

Batson, D., Shaw, L.L., Oleson, K.C.: Differentiating affect, mood and emotion: toward functionally-based conceptual distinctions. In: Clark, M. (ed.) Emotion review of personality and social psychology, vol. 13, pp. 294–326. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks (1992)

Böhm, G.: Emotional reactions to environmental risks: consequentialist versus ethical evaluation. J. Environ. Psychol. 23(2), 199–212 (2003)

Bove, L.L., Pervan, S.J., Beatty, S.E., Shiu, E.: Service worker role in encouraging customer organizational citizenship behaviors. J. Bus. Res. 62(7), 698–705 (2009)

Brown, J.S., Laundré, J.W., Gurung, M.: The ecology of fear: optimal foraging, game theory, and trophic interactions. J. Mammal. 80(2), 385–399 (1999)

Büssing, A., Recchia, D.R., Baumann, K.: Validation of the gratitude/awe questionnaire and its association with disposition of gratefulness. Religions 9(4), 117 (2018)

Buzinde, C. N.: Theoretical linkages between well-being and tourism: The case of self-determination theory and spiritual tourism. Annals Tour. Res. 83, 102920 (2020)

Carmines, E.G., Zeller, R.A.: Reliability and Validity Assessment. SAGE Publications, California (1979)

Cerdan Chiscano, M., Darcy, S.: C2C co-creation of inclusive tourism experiences for customers with disability in a shared heritage context experience. Curr. Issue Tour. 24(21), 3072–3089 (2021)

Chang, Y.P., Dwyer, P.C., Algoe, S.B.: Better together: Integrative analysis of behavioral gratitude in close relationships using the three-factorial interpersonal emotions (TIE) framework. Emotion (2021). https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0001020

Chin, W.W.: Commentary: Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Q. 22, vii–xvi (1998)

Chin, W.W., Newsted, P.R.: Structural equation modeling analysis with small samples using partial least squares. Stat. Strateg. Small Sample Res. 1(1), 307–341 (1999)

Chiu, W.Y., Tzeng, G.H., Li, H.L.: Developing e-store marketing strategies to satisfy customers’ needs using a new hybrid gray relational model. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Decis. Mak. 13(2), 231–261 (2014)

Cosimato, S., Faggini, M., del Prete, M.: The co-creation of value for pursuing a sustainable happiness: the analysis of an Italian prison community. Socioecon. Plan. Sci. 75, 100838 (2021)

Cuesta-Valiño, P., Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, P., Núnez-Barriopedro, E.: The role of consumer happiness in brand loyalty: a model of the satisfaction and brand image in fashion. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 22, 458 (2021)

Dijkstra, T.K., Henseler, J.: Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Q. 39(2), 297–316 (2015)

Dong, B., Evans, K.R., Zou, S.: The effects of customer participation in co-created service recovery. J. Acad. Market. Sci. 36(1), 123–137 (2008)

Emmons, R.A., Crumpler, C.A.: Gratitude as a human strength: appraising the evidence. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 19(1), 56–69 (2000)

Ennew, C.T., Binks, M.R.: Impact of participative service relationships on quality, satisfaction and retention: an exploratory study. J. Bus. Res. 46(2), 121–132 (1999)

European Forum SPES: European forum, spirituality in economics and society. http://eurospes.org/content/our-mission-spiritual-based-humanism (2014)

Foot, P.: Natural Goodness. Oxford University Press, New York (2001)

Fornell, C., Bookstein, F.L.: Two structural equation models: LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory. J. Mark. Res. 19(4), 440–452 (1982)

Frey, B.S., Stutzer, A.: Happiness and Economics: How the Economy and Institutions Affect Human Well-Being. Princeton University Press, Princeton (2010)

Fridja, N.H.: The Emotions. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1986)

Fujioka, Y.: A consideration of the process of co-creation of value with customers. Artif. Life Robot. 14(1), 101–103 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10015-009-0732-8

Garma, R., Bove, L.L.: Contributing to well-being: customer citizenship behaviors directed to service personnel. J. Strateg. Mark. 19(7), 633–649 (2011)

Gebauer, H., Johnson, M., Enquist, B.: Value co-creation as a determinant of success in public transport services: a study of the Swiss Federal Railway operator (SBB). Manag. Serv. Qual. Int. J. 20, 511 (2010)

Geisser, S.: A predictive approach to the random effect model. Biometrika 61(1), 101–107 (1974)

Gentile, C., Spiller, N., Noci, G.: How to sustain the customer experience: an overview of experience components that co-create value with the customer. Eur. Manag. J. 25(5), 395–410 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2007.08.005

Goetz, T., Frenzel, A.C., Stoeger, H., Hall, N.C.: Antecedents of everyday positive emotions: an experience sampling analysis. Motiv. Emot. 34(1), 49–62 (2010)

Grisez, G., Boyle, J., Finnis, J.: Practical principles, moral truth, and ultimate ends. Am. J Jurisprud. 32, 99–151 (1987)

Groth, M.: Customers as good soldiers: examining citizenship behaviors in internet service deliveries. J. Manag. 31(1), 7–27 (2005)

Groth, M., Mertens, D.P., Murphy, R.O.: Customers as good soldiers: extending organizational citizenship behavior research to the customer domain. In: Turnipseed, D.L. (ed.) Handbook of Organizational Citizenship Behavior, pp. 411–430. Nova Science Publishing (2004)

Haenlein, M., Kaplan, A.M.: A beginner’s guide to partial least squares analysis. Underst. Stat. 3(4), 283–297 (2004)

Haidt, J.: The moral emotions. In: Davidson, R.J., Scherer, K.R., Goldsmith, H.H. (eds.) Handbook of Affective Sciences, pp. 852–870. Oxford University Press (2003)

Hair, J.F., Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M.: PLS-SEM: indeed a silver bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 19(2), 139–152 (2011)

Hair, J.F., Hult, G.T.M., Ringle, C., Sarstedt, M.: A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd edn. Sage Publications (2016)

Haldorai, K., Kim, W. G., Chang, H. S., Li, J. J.: Workplace spirituality as a mediator between ethical climate and workplace deviant behavior. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 86, 102372 (2020)

Hareli, S., Rafaeli, A.: Emotion cycles: on the social influence of emotion in organizations. Res. Organ. Behav. 28, 35–59 (2008)

Hektner, J.M., Schmidt, J.A., Csikszentmihalyi, M.: Experience Sampling Method: Measuring the Quality of Everyday Life. Sage (2007)

Helliwell, J.F., Huang, H., Wang, S., Norton, M.: Social environments for world happiness. World Happiness Rep. 2020(1), 13–45 (2020)

Henseler, J.: Partial least squares path modeling. In: Advanced Methods for Modeling Markets, pp. 361–381. Springer, Cham (2017)

Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M., Sarstedt, M.: A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 43(1), 115–135 (2015)

Henseler, J., Hubona, G., Ray, P.A.: Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: updated guidelines. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 116, 2 (2016)

Ho, C.Y., Tsai, B.H., Chen, C.S., Lu, M.T.: Exploring green marketing orientations toward sustainability the hospitality industry in the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 13(8), 4348 (2021)

Hofmann, S.G.: The pursuit of happiness and its relationship to the meta-experience of emotions and culture. Aust. Psychol. 48(2), 94–97 (2013)

Hsieh, Y.C., Chiu, H.C., Tang, Y.C., Lin, W.Y.: Does raising value co-creation increase all customers’ happiness? J. Bus. Ethics 152(4), 1053–1067 (2018)

Hu, L.T., Bentler, P.M.: Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 3(4), 424 (1998)

Hu, L. T., Bentler, P. M.: Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equat. Model. Multidis. J. 6(1), 1–55 (1999)

Hughes, T., Vafeas, M.: Happiness and co-creation of value: playing the blues. Mark. Theory 21(4), 579–589 (2021)

Intelisano, S., Krasko, J., Luhmann, M.: Integrating philosophical and psychological accounts of happiness and well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 21(1), 161–200 (2020)

Johnson, B., Manoli, C.C.: The 2-MEV scale in the United States: a measure of children’s environmental attitudes based on the theory of ecological attitude. J. Environ. Educ. 42(2), 84–97 (2011)

Kelley, S.W., Donnelly, J.H., Skinner, S.J.: Customer participation in service production and delivery. J. Retail. 66(3), 315 (1990)

Keltner, D., Haidt, J.: Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cogn. Emot. 17(2), 297–314 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930302297

Kim, U., Triandis, H.C., Kagitcibasi, C., Yoon, G.: Individualism and Collectivism: Theoretical and Methodological Issues. Sage, Newbury Park (1994)

Lengnick-Hall, C.A., Claycomb, V., Inks, L.W.: From recipient to contributor: Examining customer roles and experienced outcomes. Eur. J. Mark. 34(3/4), 359–383 (2000)

Malti, T., Ongley, S.F., Killen, M., Smetana, J.: The development of moral emotions and moral reasoning. Handb. Moral Dev. 2, 163–183 (2014)

Markowitz, G., Rosner, D.: Deceit and Denial. University of California Press (2013)

Neuhofer, B., Buhalis, D., Ladkin, A.: Co-creation through technology: dimensions of social connectedness. In: Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2014, pp. 339–352. Springer, Cham (2013)

Núñez-Barriopedro, E., Ravina-Ripoll, R., Ahumada-Tello, E.: Happiness perception in Spain, a SEM approach to evidence from the sociological research center. Qual. Quant. 54(3), 761–779 (2020)

Núñez-Barriopedro, E., Cuesta-Valiño, P., Gutiérrez-Rodríguez, P., Ravina-Ripoll, R.: How does happiness influence the loyalty of karate athletes? A model of structural equations from the constructs: consumer satisfaction, engagement, and meaningful. Front. Psychol. 12, 794 (2021)

Pera, R., Viglia, G.: Turning ideas into products: subjective well-being in co-creation. Serv. Ind. J. 35(7–8), 388–402 (2015)

Phillips, J., De Freitas, J., Mott, C., Gruber, J., Knobe, J.: True happiness: the role of morality in the folk concept of happiness. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 146(2), 165 (2017)

Prebensen, N.K., Woo, E., Chen, J.S., Uysal, M.: Motivation and involvement as antecedents of the perceived value of the destination experience. J. Travel Res. 52(2), 253–264 (2013)

Ralston, D.A., Egri, C.P., Furrer, O., Kuo, M.H., Li, Y., Wangenheim, F., et al.: Societal-level versus individuallevel predictions of ethical behavior: a 48-society study of collectivism and individualism. J. Bus. Ethics 122(2), 283–306 (2014)

Ravina-Ripoll, R., Marchena Domínguez, J., Montañes Del Rio, M.: Happiness Management en la época de la Industria 4.0. RETOS. Rev. Cienc. Adm. Econ. 9(18), 189–202 (2019a)

Ravina-Ripoll, R., Núñez-Barriopedro, E., Evans, R.D., Ahumada-Tello, E.: Employee happiness in the industry 4.0 era: insights from the Spanish industrial sector. In: 2019b IEEE Technology & Engineering Management Conference (TEMSCON), pp. 1–5. IEEE (2019b)

Ravina-Ripoll, R., Nuñez-Barriopedro, E., Almorza-Gomar, D., Tobar-Pesantez, L.B.: Happiness management: a culture to explore from brand orientation as a sign of responsible and sustainable production. Front. Psychol. 12, 727845 (2021a)

Ravina-Ripoll, R., Romero-Rodríguez, L.M., Ahumada-Tello, E.: Workplace happiness as a trinomial of organizational climate, academic satisfaction and organizational engagement. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 22(3), 474–490 (2021b)

Rigdon, E.E., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C.M.: On comparing results from CB-SEM and PLS-SEM: five perspectives and five recommendations. Mark. ZFP 39, 4–16 (2017)

Robina-Ramírez, R., Medina-Merodio, J.A.: Transforming students’ environmental attitudes in schools through external communities. J. Clean. Prod. 232, 629–638 (2019)

Robina Ramirez, R., Pulido Fernandez, M.: Religious travellers’ improved attitude towards nature. Sustain. 10(9), 3064 (2018)

Robina Ramírez, R., Fernández Portillo, A.: What role does touristś educational motivation play in promoting religious tourism among travellers? Ann. Leis. Res. 23(3), 407–428 (2020)

Robina-Ramírez, R., Cotano-Olivera, C.: Driving private schools to go “green”: the case of Spanish and Italian religious schools. Teach. Theol. Relig. 23(3), 175-188 (2020)

Robina-Ramírez, R., Isabel Sánchez-Hernández, M., Díaz-Caro, C.: Hotel manager perceptions about corporate compliance in the tourism industry: an empirical regional case study in Spain. J. Manag. Gov. 25(2), 627–654 (2021a)

Robina-Ramírez, R., Medina-Merodio, J.A., Estriégana, R., Jimenez-Naranjo, H.V.: Money cannot buy happiness: improving governance in the banking sector through spirituality. Corp. Gov. Int. J. Bus. Soc. (2021b)

Robina-Ramírez, et al.: What do urban and rural hotel managers say about the future of hotels after COVID-19? The new meaning of safety experiences (2021c)

Robina-Ramírez, R., Sánchez, M.S.O., Jiménez-Naranjo, H.V., Castro-Serrano, J.: Tourism governance during the COVID-19 pandemic crisis: a proposal for a sustainable model to restore the tourism industry. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 24(5), 6391–6412 (2022)

Rudd, M., Vohs, K.D., Aaker, J.: Awe expands people’s perception of time, alters decision making, and enhances well-being. Psychol. Sci. 23(10), 1130–1136 (2012)

Ruhanen, L., Saito, N., Axelsen, M.: Knowledge co-creation: the role of tourism consultants. Ann. Tour. Res. 87, 103148 (2021)

Salter, D.W.: Testing the attraction-selection-attrition model of organizational functioning: the personality of the professoriate. J. Psychol. Type 66(10), 88–97 (2006)

Sánchez Martín, J.M., Rengifo Gallego, J.I.: Evolución del sector turístico en la Extremadura del siglo XXI: auge, crisis y recuperación. Lurralde 42, 19–50 (2019)

Sánchez-Hernández, M.I., Stankevičiūtė, Ž, Robina-Ramirez, R., Díaz-Caro, C.: Responsible job design based on the internal social responsibility of local governments. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17(11), 3994 (2020)

Sánchez-Oro Sánchez, M., Robina Ramírez, R.: Los grupos focales (“focus group”) como herramienta de investigación turística. Universidad de Extremadura (2020)

Sanjuán, P., Magallares, A.: Coping strategies as mediating variables between self-serving attributional bias and subjective well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 15(2), 443–453 (2014)

Schneider, B.: The people make the place. Pers. Psychol. 40(3), 437–453 (1987)

Shiota, M.N., Campos, B., Oveis, C., Hertenstein, M.J., Simon-Thomas, E., Keltner, D.: Beyond happiness: building a science of discrete positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 72(7), 617 (2017)

Singagerda, F.: How much media marketing and brand image reinforce ecommerce consumer loyalty? Int. J. Data Netw. Sci. 4(4), 389–396 (2020)

Snyder, M., Omoto, A.M.: Volunteerism: Social issues perspectives and social policy implications. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2(1), 1–36 (2008)

Stellar, J.E., Gordon, A.M., Piff, P.K., Cordaro, D., Anderson, C.L., Bai, Y., Maruskin, L.A., Keltner, D.: Self-transcendent emotions and their social functions: compassion, gratitude, and awe bind us to others through prosociality. Emot. Rev. 9(3), 200–207 (2017)

Stone, M.: An asymptotic equivalence of choice of model by cross-validation and Akaike's criterion. J. Royal Stat. Soc. Series B (Methodological), 44–47 (1977)

Tamir, M., Schwartz, S.H., Oishi, S., Kim, M.Y.: The secret to happiness: feeling good or feeling right? J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 146(10), 1448 (2017)

Tan, S.K., Tan, S.H., Luh, D.B., Kung, S.F.: Understanding tourist perspectives in creative tourism. Curr. Issue Tour. 19(10), 981–987 (2016)

Teye, V., Sonmez, S.F., Sirakaya, E.: Residents’ attitudes towards tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 29, 668–688 (2002)

Ueda, K., Takenaka, T., Fujita, K.: Toward value co-creation in manufacturing and servicing. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 1(1), 53–58 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cirpj.2008.06.007

Vargo, S.L., Lusch, R.F.: Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. J. Mark. 68(1), 1–17 (2004)

Vargo, S.L., Maglio, P.P., Akaka, M.A.: On value and value co-creation: a service systems and service logic perspective. Eur. Manag. J. 26(3), 145–152 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2008.04.003

Waterman, A.S.: Reconsidering happiness: a eudaimonist’s perspective. J. Posit. Psychol. 3(4), 234–252 (2008)

Weathers, E., McCarthy, G., Coffey, A.: Concept analysis of spirituality: an evolutionary approach. Nurs. Forum 51(2), 79–96 (2016)

Wispé, L.: The Psychology of Sympathy. Springer (1991)

Wong, K.K.K.: Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) techniques using SmartPLS. Mark. Bull. 24, 1–32 (2013)

Xie, J., Tkaczynski, A., Prebensen, N.K.: Human value co-creation behavior in tourism: insight from an Australian whale watching experience. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 35, 100709 (2020)

Yi, Y., Gong, T.: If employees “go the extra mile”, do customers reciprocate with similar behavior? Psychol. Mark. 25(10), 961–986 (2008)

Yi, Y., Gong, T.: Customer value co-creation behavior: scale development and validation. J. Bus. Res. 66(9), 1279–1284 (2013)

Yi, Y., Nataraajan, R., Gong, T.: Customer participation and citizenship behavioral influences on employee performance, satisfaction, commitment, and turnover intention. J. Bus. Res. 64(1), 87–95 (2011)

Zatori, A., Smith, M.K., Puczko, L.: Experience-involvement, memorability and authenticity: the service provider’s effect on tourist experience. Tour. Manag. 67, 111–126 (2018)

Zayed, M.F., Gaber, H.R., El Essawi, N.: Examining the factors that affect consumers’ purchase intention of organic food products in a developing country. Sustainability 14(10), 5868 (2022)

Zinnbauer, B.J., Camerota, E.C.: The spirituality group: a search for the sacred. J. Transpers. Psychol. 36(1), 50–65 (2004)

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. The publication of this work was possible thanks to the funding provided by the European Regional Development Fund andby the Consejería de Economía, Ciencia y Agenda Digital from Junta de Extremadura through Grant GR18052.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Robina-Ramírez, R., Leal-Solís, A., Medina-Merodio, J.A. et al. From satisfaction to happiness in the co-creation of value: the role of moral emotions in the Spanish tourism sector. Qual Quant 57, 3783–3804 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-022-01528-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-022-01528-0