Abstract

We ask whether fiscal rules constrain incumbents from using fiscal policy tools for reelection purposes. Using data on fiscal rules provided by the IMF for a sample of 77 (advanced and developing) countries over the 1984–2015 period, we find that strong fiscal rules dampen political budget cycles. Our results are remarkably robust against inclusion of media freedom and the level of government debt as explanatory variables. Furthermore, we find a strong effect of fiscal rules in, amongst others, countries with fewer veto players, left-wing governments, established democracies, and more globalized economies. In addition, the effect of fiscal rules on political budget cycles seems to be stronger after the global financial crisis, reflecting post-crisis expansion in the number of countries with strong fiscal rules, notably in the European Union.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The political budget cycle (PBC) literature focuses on election cycles in government spending, taxation and budget deficits. Early PBC models were based on the premise that incumbents manipulate fiscal policy in order to secure reelection and predicted that governments adopt expansionary fiscal policies before Election Day (Nordhaus 1975). More recent PBC models emphasize the role of temporary informational asymmetries regarding politicians’ competencies in explaining electoral cycles in fiscal policy. In those models, signaling competency is the driving force behind the PBC (see, for example, Shi and Svensson 2006).Footnote 1 Although the evidence is mixed, several studies report evidence for election effects in fiscal policy.Footnote 2

Recent research no longer assumes that all governments will behave in the same way, but asks under what circumstances a PBC is more likely to occur (de Haan and Klomp 2013). The more private benefits politicians gain when in power (i.e., larger rents from remaining in public office), the stronger are their incentives to influence voters’ perceptions prior to an election. Incumbents’ ability to manipulate government finances is shaped by a number of different constraints on their behavior.Footnote 3 Recently, Veiga et al. (2017) examined circumstances under which fiscal manipulation may occur, differentiating between several factors affecting the incentives of the incumbent to behave opportunistically, factors affecting the capacity of the opportunistic policies to yield additional votes,Footnote 4 and characteristics of political institutions, such as proportional versus majoritarian electoral rules. They find that the degree of media freedom is the most important conditioning factor for PBCs. When media freedom is weak, the electoral effect on budget deficits is strong.

However, Veiga et al. (2017) do not consider whether fiscal rules, i.e., long-lasting constraints on fiscal policy in the form of numerical limits on budgetary aggregates (Schaechter et al. 2012), condition PBCs. It is likely that incumbents constrained by such rules will have a more difficult time increasing spending or cutting taxes before elections. As Alt and Rose (2007, p. 862) in their analysis of fiscal rules in US states write, “we should observe larger cycles in states without fiscal rules than in those with rules if these rules are effective in limiting politicians’ ability to run deficits and thus manipulate the timing of spending for electoral purposes.” And that indeed is what they find. In explaining the result, Alt and Rose refer to the signal-extraction problem faced by financial markets, i.e., how to discern the true state of affairs from the available information. Lowry and Alt (2001) argue that balanced budget requirements allow bond market participants to solve precisely such a signal-extraction problem, thereby making it easier for imperfectly informed bond market investors to distinguish between political officials who choose to comply with balanced budgets and those who do not. Alt and Rose (2007, p. 863) argue that “if politicians in states with no-carry rules run consecutive deficits, investors interpret their behavior as opportunism and respond sharply.” Fiscal rules therefore may narrow the government’s room for fiscal maneuvering, thereby limiting the incumbent’s capacity to behave opportunistically.

On the other hand, strict fiscal rules may encourage incumbents to circumvent the rules, making use of creative accounting practices (Milesi-Ferretti 2004). Some evidence supports that view. For instance, focusing on member states of the European Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), Alt et al. (2014) report that governments running excessive budget deficits resort to ‘gimmickry’ instead of abiding by the rules of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP), thereby (at least temporarily) avoiding policies that may be unpopular electorally.Footnote 5

By now, an extensive literature exists on fiscal rules, both covering factors driving their adoption and their consequences. For instance, using a large cross-section of countries, Altunbas and Thornton (2017) examine the economic, institutional and political characteristics of countries affecting the likelihood that a numerical rule will be adopted as part of a fiscal strategy to limit the level of public debt. As to their consequences, fiscal rules have been found to reduce macroeconomic volatility (Fatas and Mihov 2006), diminish the procyclicality of fiscal policy (Bergman and Hutchison 2015), reduce public debt (Azzimonti et al. 2016), lower budget deficits (Caselli and Reynaud 2019) and reduce the probability of experiencing sovereign debt crises (Asatryan et al. 2018).Footnote 6

Thus far, the question of whether fiscal rules affect the existence of election cycles in fiscal policy has received only scant attention in a cross-country context. Footnote 7 The only study of which we are aware is by Ademmer and Dreher (2016), who conclude that fiscal institutions only help to limit the sizes of PBCs in weak media environments. Their study, however, is confined to European Union (EU) countries.

Using data for 77 (advanced and developing) democracies over the 1984–2015 period and the IMF’s database of fiscal rules (Schaechter et al. 2012), we ask whether fiscal rules prevent incumbent governments from using fiscal policy for reelection purposes. We do so by investigating the effect of the interaction between (the strength of) fiscal rules and the proximity of elections on the government budget balance. Our results suggest that strong fiscal rules constrain PBCs. That result potentially could be driven by EU member states because those countries adopted more stringent fiscal rules in the wake of the global financial crisis. Nevertheless, a sensitivity analysis reveals that strong fiscal rules also limit opportunistic behavior during elections in non-EU countries.

Other sensitivity analyses show that our results are remarkably robust against including media freedom and the level of government debt as explanatory variables. Furthermore, we find that fiscal rules have substantial effects in, amongst others, countries with fewer veto players, left-wing governments, established democracies, and more globalized economies. In addition, the effect of fiscal rules on PBCs seems to be stronger after the global financial crisis, reflecting post-crisis expansion in the number of countries adopting such rules.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 describes the data on which we rely, while Sect. 3 outlines our methodology and Sect. 4 presents the main results. Section 5 offers a robustness analysis; Sect. 6 concludes.

2 Data

Our dataset consists of an unbalanced panel of 77 democracies over the 1984–2015 period.Footnote 8 As PBC theory presumes that a country is democratic, we only consider countries with a score of 6 or more for the Polity2 index taken from the Polity IV database of the Center for Systematic Peace. Furthermore, we only included countries for which we have enough observations (i.e., at least ten, preferably, consecutive data points) and if the period under consideration contains at least two observed (competitive) elections. Finally, we checked for outliers, which led to the exclusion of two countries (Niger and Mali).Footnote 9

Data on the governments’ primary budget balances as percentages of GDP (our dependent variable) were collected from the IMF’s World Economic Outlook Database.Footnote 10 We rely on the primary balance because interest payments on outstanding public debt, which are included in governmental budget balances, do not reflect fiscal policies in the current period. All democratic countries for which the IMF reports data on primary balances have been included in our sample. Data on elections were taken from several editions of the Political Handbook of the World and from the PARLINE database of the Inter-Parliamentary Union. To evaluate the effects of elections on fiscal policy stances, it is important for the incumbent government to control its budget. Therefore, we follow de Haan and Klomp (2016) in identifying elections relevant to our study: if the president or prime minister has no legislative powers in the realm of fiscal policy and is accountable to a parliamentary majority that can bring the government down by voting “no confidence”, we classify the country concerned as a parliamentary regime and rely only on elections for parliament.

Early resignation of the government might be caused due to factors that arguably also affected fiscal policies, like a crisis or social unrest (Shi and Svensson 2006). Therefore, we ignore early elections, because they might be endogenous to the government’s budget balance. Following Shi and Svensson (2006), we consider elections only if it (1) is held on the fixed date (year) specified by the constitution, (2) is held in the last year of a constitutionally fixed term for the legislature or (3) the election is announced at least 1 year in advance.

It is common practice in the literature to enter an election dummy if elections were held in a particular year. However, that practice is likely to create measurement error, since it ignores the timing of elections (Franzese 2000). Governments can manipulate fiscal policy in the year prior to an election. In fact, they probably should do so if they want to benefit electorally from their manipulations in view of the time delay required for new fiscal policy measures to produce macroeconomic effects. Our election variable therefore is calculated as M/12 in an election year and (12 − M)/12 in a pre-election year, where M is the m-th month of the year in which the election is held. In all other years, its value is set equal to zero.Footnote 11

We collected data on fiscal rules from the IMF’s Fiscal Rules Dataset (Schaechter et al. 2012). The dataset considers national and supranational fiscal rules and covers four categories: budget balance rules, debt rules, expenditure rules and revenue rules. Furthermore, the dataset provides information on five key characteristics of those rules. We consider national and supranational fiscal rules and construct our index as follows:

where ‘coverage’ identifies the governmental tier (central or general, i.e., including subnational governments) covered by the rule. ‘Legal basis’ considers the statutory basis of the rule, ranging from political agreements, to legislative statutes, to constitutional rules. ‘Supporting procedures’ is the sum of the existence (or lack thereof) of multi-year expenditure ceilings, a fiscal responsibility law and an independent fiscal body setting budget assumptions and monitoring its implementation. ‘Enforcement’ is measured as the sum of having a formal enforcement procedure and whether or not a monitoring mechanism external to the government is in place. Finally, ‘flexibility’ captures whether a well-defined escape clause exists, whether a balanced budget target is adjusted cyclically, and whether public infrastructure spending is excluded from the expenditure ceiling.Footnote 12 That method yields 11 characteristics in total.Footnote 13 All five of the independent variables are normalized to unity so that the fiscal rules index has values between 0 and 5.Footnote 14

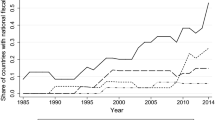

Apart from an aggregate fiscal rules index, we enter four disaggregated indexes, capturing rules referring to budget deficits, public debt, government expenditures and revenues. As shown in Fig. 1, multiple types of fiscal rules are in place in several of the countries in our sample. Using sub-indexes, we can evaluate whether different types of fiscal rules have distinctive effects on the government’s budget balance and whether their conditional effects on the impact of elections differ. We constructed the sub-indexes in ways similar to the aggregate index described above. While the data on ‘legal basis’, ‘coverage’, ‘enforcement’ and ‘flexibility’ are specific for each type of fiscal rule, the score on ‘supporting procedures’ is the same for each type of rule, meaning that when a country has adopted supporting procedures, each disaggregated fiscal rules index would have the minimum possible score. We have set the corresponding index equal to zero to correct for effects that the index would otherwise assign to a non-existing fiscal rule. Therefore, when a country has supporting procedures in place, the overall fiscal rules index is not an average of the four disaggregated indexes.

Figure 2 displays the average value of the fiscal rules index over the sample period and also shows the index’s development over time for EU and non-EU countries. As shown in the figure, the index not only varies across countries, but also reveals substantial variation over time within countries. Several countries, notably in the EU, have adopted more stringent fiscal rules over time. However, there are also countries for which the index has declined over time, either because they decided to drop a fiscal rule—e.g., in the United States—or because of a change in the design of the fiscal framework—e.g., in the Netherlands. To check whether our results are driven by EU countries, we include a sensitivity analysis in which we focus on non-EU countries only.

3 Method

To investigate whether fiscal rules constrain PBCs, we estimate a dynamic panel data model. The model takes the following form:

where \(Budget_{i,t}\) measures the government’s primary budget balance (scaled by GDP) for country i in year t. The 1-year lag of the dependent variable controls for path dependence since governments often make multi-year budgetary plans for their expected terms in office. Furthermore, when governments are faced with budgetary pressures, required fiscal adjustments often are spread over multiple years. Therefore, we expect persistence in budget deficits.Footnote 15\(Elections_{i,t}\) is the election variable as defined above, \(FRI_{i,t}\) is one of our fiscal rules indexes (i.e., the aggregate index and rules for budget deficits, public debt, government expenditures and government revenues),Footnote 16 and \(Elections_{i,t} *FRI_{i,t}\) is the interaction between fiscal rules and elections. Vector \(X_{i,t}\) is a set of control variables, including a 1-year lag of the public-debt-to-GDP ratio. In addition, \(X_{i,t}\) contains the inflation rate (based on consumer prices) and GDP growth to control for business cycle dynamics (all taken from the World Economic Outlook Database). We also enter year dummies,\(\tau_{t}\), to control for common time effects. Finally, \(\mu_{i}\) captures the unobserved country-specific effects; \(\varepsilon_{i,t}\) is the i.i.d. error term.

We estimate the model using panel fixed effects (FE) to eliminate country-specific heterogeneity. The dynamic panel data model, however, contains a potential bias owing to the inclusion of the lagged dependent variable. Even though our sample period is quite long (T = 31) so that the results may not be affected much by potential endogeneity that could arise from that modeling choice, we estimate alternative specifications to control for the so-called Nickell bias. First, we estimate a bias-corrected fixed effects (LSDVC) specification (Bun and Kiviet 2003). LSDVC estimation avoids the Nickell bias, but assumes strict exogeneity of the explanatory variables. Second, we estimate a GMM model that controls for endogeneity. The widely used Arellano and Bond (1991) GMM and system GMM (Blundell and Bond 1998) assume mean stationarity of the variables. That assumption is unlikely to hold in our panel.Footnote 17 We therefore run the GMM estimator as suggested by Ahn and Schmidt (1995), which does not require mean stationarity.

4 Results

Table 1 reports the fixed effects estimation results with country clustered standard errors. Column (1) provides estimates of Eq. (2), excluding the interaction between our election variable and aggregated fiscal rules index; that interaction is entered in column (2). Following the same setup, the subsequent columns in Table 1 show results for the disaggregated indexes referring to expenditures, revenues, budget balance, and debt, respectively.

In column (1) of Table 1, the 1-year lag of the budget balance variable reveals (as expected) considerable path dependence in the dependent variable (similar results are reported by other studies like Alt and Lassen 2006b; Klomp and de Haan 2013), while GDP growth seems to improve the budget balance. The estimated coefficients on the inflation measure and the level of public debt likewise are positive and significant. The estimated coefficient on the election variable is negative and significant, suggesting that in election years the government’s budget balance deteriorates.

Our results suggest that strong fiscal rules are associated with smaller budget deficits. Furthermore, the coefficient on the aggregate fiscal index in column (1) is, on average, twice as large as the coefficients on the disaggregated indexes referring to expenditures, revenues, budget balance, and debt rules, as shown in columns (3), (5), (7) and (9). As shown in column (2) of Table 1, the coefficient on the interaction of our election variable and the aggregate fiscal rules index is positive, but insignificant. The same holds true for the interactions between our election variable and the sub-indexes.

As shown by Brambor et al. (2006), the coefficients on the election variable and the fiscal rules indexes in the interaction models must not be interpreted as the average (unconditional) effect on the government budget as in linear-additive models. The marginal effect of elections on the budget balance should therefore not be assessed based on the significance (or lack thereof) of the coefficient on the interaction term, but should be assessed for all possible values of the fiscal rules index. Figure 3 shows the marginal effect of elections on the government budget balance conditional on the overall fiscal index and the sub-indexes for the different types of fiscal rules. The red line depicts the marginal effect of elections and the dashed lines display the 95% confidence interval for which the marginal effect is calculated. The grey bars show the percentages of observations for each observed value of the fiscal rules index. As indicated in Fig. 2, most countries had not yet adopted a fiscal rule at the beginning of our sample period. Fiscal rules were put in place gradually over time. Therefore, for many observations the fiscal rules index contains a value of zero (i.e., a country had no fiscal rule).

Marginal effect of elections conditional on different types of fiscal rules. Notes The marginal effects of elections on the primary budget balance conditional on the strength of fiscal rules are calculated with a 95% confidence interval following the instructions of Brambor et al. (2006). The graphs are based on the estimates shown in columns (2), (4), (6), (8) and (10) of Table 2, respectively

The graphs show that most types of fiscal rules constrain politicians from exploiting fiscal policy tools for reelection purposes (the exception being revenue rules).Footnote 18 Only in countries with weak fiscal rules (i.e., in countries with low values for the fiscal rules index), the marginal effect of the elections variable is significantly different from zero. Once the fiscal rules index rises to a certain threshold (depending on the fiscal rules index, somewhere between 1.75 and 3.75), the marginal effect of elections becomes insignificant. Hence, Fig. 3 suggests that elections, on average, do not affect fiscal policy in countries with strong fiscal rules.

Note, however, that the absence of sufficient variation in the indexes, most notably for the revenue rules index, causes wider confidence intervals—especially for higher values of the fiscal rules’ index (Hainmueller et al. 2019). Lack of variation in the data could inflate or deflate the estimated marginal effects of elections for values of the fiscal rules index where observations are sparse (King and Zeng 2006). Consequently, the conditional marginal-effect estimates may be fragile and model dependent.

We therefore follow Hainmueller et al. (2019) to assess the validity of our interaction effect estimates.Footnote 19 To improve the empirical estimates, those authors developed a simple strategy allowing the conditional effects and the coefficients on the covariates to vary freely across the moderator variable. That strategy admits nonlinear interaction effects and safeguards against excessive inflation of the estimates for observations without sufficient data support.

Figure A1 in the online appendix shows the marginal effect plot for the aggregate fiscal rules index and for its disaggregated components. Figure A1 reveals that the results for the overall fiscal rules index are almost identical to those displayed in Fig. 3, for which we followed the guidelines of Brambor et al. (2006). The conditional marginal effect seems to be linear and the cutoff points at which the marginal effect of elections loses significance appear to be very close to each other (i.e., at a value of 2.5 of the fiscal rules index). Because the disaggregated fiscal rules indexes contain less variation, the conditional marginal effects and the corresponding confidence intervals vary more widely. Nevertheless, all conclusions remain unchanged. Therefore, we conclude that our results do not suffer from assuming a linear interaction effect and a lack of common support of the fiscal rules index when computing the conditional marginal effects.

5 Sensitivity analysis

Are the findings reported above robust when we use the different estimation methods outlined in Sect. 3? Table 2 reports the results for the bias corrected fixed effects estimation (LSDVC) and generalized methods of moments estimation (GMM) approaches for the aggregate fiscal rules index. Figure A2 in the online appendix shows the corresponding marginal effect plots. The LSDVC estimates seem to add a bit more explanatory power to the lagged dependent variable,Footnote 20 whereas the effect of fiscal rules is more prevalent and significant in the GMM estimation. What is most important, the results do not differ much from those reported in Table 2. Hence, our findings suggest that the Nickell bias does not affect the results so that we continue using panel fixed effects estimations.

In general, the countries with high values of the fiscal rules index are EU member states; those countries tended to adopt more stringent fiscal rules than non-EU countries (see Fig. 2). To investigate whether our results are driven by EU countries, we have estimated our main model for the non-EU countries in our sample. Based on those estimates, Fig. 4 shows the marginal effect of elections conditional on the strength of the fiscal rules for non-EU countries, following the approach of Hainmueller et al. (2019). The results suggest that our results are not driven by EU countries because in the sample of non-EU countries strong fiscal rules also limit the effects of elections on the primary budget balance.

Effect of the strength of fiscal rules on PBCs: non-EU countries. Notes The marginal effects of elections on the primary budget balance conditional on the strength of fiscal rules are calculated with a 95% confidence interval following the instructions of Hainmueller et al. (2019). The estimation strategy is a kernel-smoothing estimator of the conditional marginal effect, which is based upon the semiparametric varying-coefficient estimator of Li and Racine (2010). The blue line shows the marginal effects of elections conditional to the fiscal rules index; the surrounding gray area shows the confidence interval for which the marginal effect is calculated. The grey bars on the bottom show the percentage of observations for the fiscal rules index. (Color figure online)

One issue with the results reported in the previous section is the potential endogeneity of our fiscal rules index. Obviously, the establishment of a fiscal rule or its strictness might be related to the country’s fiscal stance. For instance, countries with high public debt (for which we control) might be more likely to introduce stricter fiscal rules. Consequently, interdependencies between fiscal policies and fiscal rules are possible (Heinemann et al. 2018). Heinemann et al. (2018, p. 70) conclude in their meta-regression analysis of the effects of fiscal rules on fiscal policy outcomes that their analysis points “to a substantial bias if the potential endogeneity of fiscal rules is neglected, confirming that these concerns have to be taken seriously. This insight strongly weakens the seemingly optimistic message in the existing empirical literature with respect to the effectiveness of fiscal rules.” However, our IV estimates (reported in the online appendix), in which we either enter the fiscal rules index with a lag (following Debrun et al. 2008) or use the determinants of fiscal rules’ adoption identified by Altunbas and Thornton (2017) as instruments, do not suggest that our results are driven by the endogeneity of fiscal rules.

Next, we have entered several additional control variables into our model. As shown in the literature review of de Haan and Klomp (2013), evidence has been reported suggesting that some variables condition the effect of elections on fiscal policy. However, those variables never have been considered simultaneously. As de Haan and Klomp (2013, p. 402) write, “In our view, the most important challenge is to try to identify whether some of the conditioning variables as identified in the literature dominate others.” We ask whether the conditioning impact of fiscal rules on PBCs remains salient once we interact them with other variables suggested by the literature. To do so, we have estimated three-way interaction models.Footnote 21 Figure 5 displays the results of the three-way interaction models, while Table A4 in the online appendix reports the corresponding estimation results.

Marginal effects of elections conditional on fiscal rules; additional control variables. Notes The marginal effects of elections on the primary budget balance conditional on the strength of fiscal rules are calculated with a 90% confidence interval following the instructions of Brambor et al. (2006). The graphs are based on the estimates shown in columns (1)–(7) of Table A4, respectively

First, we follow Shi and Svensson (2006) and Veiga et al. (2017) by entering media freedom. The smaller is the information gap between politicians and voters, the less the incumbent can manipulate fiscal policy. Alt and Rose (2007) argue that competitive media outlets with substantial market penetration will reduce such informational asymmetry, thereby making it less likely that PBCs will be observed. Following Veiga et al. (2017), we proxy media freedom, defined as a press status variable obtained from Freedom House’s 2017 Freedom of the Press index.Footnote 22 It indicates whether the media environment is considered to be “free”, “partially free”, or “not free” and varies between 0 and 1. To keep the model tractable, we simplified the index into a binary variable indicating whether the media environment in a country was considered to be “free” (Z = 1) or not, i.e., “partially free” or “not free” (Z = 0). The results shown in Fig. 5a suggest that when a country does not have a fiscal rule in place, elections have a stronger impact on the government’s budget if its media is not free. However, fiscal rules constrain PBCs irrespective of whether a country’s media is or is not free, suggesting that the inclusion of media freedom does not affect our baseline results.

Next, we consider the level of government debt because indebtedness may constrain the government’s ability to behave opportunistically in election years.Footnote 23 To do so, we distinguish between countries with low (Z = 0) and high (Z = 1) public debt (as percentage of GDP) based on the median of that variable. The results displayed in Fig. 5b indicate that a large government debt does not prevent incumbent governments from behaving opportunistically during elections. On the contrary, the effect of elections on the budget seems to be large in countries with high public debt. Furthermore, the constraining effect of fiscal rules does not seem to differ across low or high government debt levels, suggesting that our results are not driven by government debt accumulation.

We also control for checks and balances in the political system following Streb et al. (2009). As Franzese (2002, p. 384) notes, when policy control is shared by multiple policy makers, “problems of bargaining, agency, coordination, and collective action will dampen, or otherwise complicate, electioneering, especially insofar as these entities serve different constituents.” Data on the number of legislative veto players is taken from the 2017 Database of Political Institutions (DPI) of the Inter-American Development Bank (Cruz et al. 2018). We compute the median to distinguish between countries for which the number of legislative veto players is small (Z = 0) or large (Z = 1) to construct a binary variable. The results displayed in Fig. 5c suggest that elections have a stronger impact on the government budget in countries with a small number of legislative veto players than in countries with a large number of veto players. Fiscal rules constrain electorally incentivized manipulations of fiscal policy in countries with few veto players, but in countries with more veto players, fiscal rules do not seem to have a mitigating effect.

In addition, we examine the role of political ideology. PBC theory predicts that incumbents, independent of their ideologies, manipulate fiscal policies to enhance their reelection chances. That prediction suggests that ideology should not matter. Nevertheless, we have considered the impact of government ideology.Footnote 24 For that purpose, we rely on a (rather crude) proxy for ideology from the 2017 DPI database that captures the incumbents’ ideological orientation with respect to economic policy.Footnote 25 We distinguish between governments with right-wing (Z = − 1), centrist (Z = 0) and left-wing (Z = 1) political ideology. Figure 5d shows the results. We find a strong effect of elections on the government budget balance in countries with left-wing and centrist governments. On the other hand, right-wing governments do not seem to manipulate fiscal policies significantly before elections in our panel. Furthermore, we find that fiscal rules constrain electoral manipulations more strongly in countries with left-wing governments.

According to Janků and Libich (2019), the ‘budget shock’ brought about by the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) raised voters’ cost of inattention. Therefore, it may have strengthened their incentives to acquire and process fiscal policy information. Likewise, that increase in the cost of inattention may have reduced the incentives of politicians to manipulate fiscal policy.Footnote 26 Janků and Libich (2019, p. 22) conclude that their results offer “a more general lesson. It implies caution in conducting empirical research on fiscal policy that includes both the pre-GFC and post-GFC periods. We show that the possible structural break around 2008 must be controlled for to avoid misleading results, and that using the usual time dummies may be insufficient.” We followed up on that advice and find that the conditional effect of fiscal rules on the marginal impact of elections on the government budget is different for the pre-GFC (Z = 0) and post-GFC (Z = 1) periods.Footnote 27 The results in Fig. 5e show that prior to the financial crisis, fiscal rules did not seem to dampen PBCs, but in the post-GFC period, fiscal rules strongly affect opportunistic behavior in election years. We argue that the strengthening of fiscal rules after the GFC is the main driver of that outcome. As shown in Fig. 2, the number of countries with fiscal rules in place expanded after the GFC. In addition, these rules may have started to ‘bite’ more often.

Next, we follow Brender and Drazen (2005) and consider the age of democracy. The argument is that “in economies in which the electorate has a lot of experience with elections, and where the collection and reporting of the relevant data to evaluate economic policy are common, voters would be unlikely to ‘fall’ for the trick of making the economy look good right before elections” (Brender and Drazen 2005, pp. 1289–1290). Following Veiga et al. (2017), we created a dummy that is one when a country has had four competitive elections and at least ten consecutive democratic years (i.e., an established democracy). Figure 5f displays the results. We find that fiscal rules maintain their constraining effects on electoral manipulations of fiscal policy in established democracies, but in new democracies, PBCs are present irrespective of fiscal rules. The latter finding is consistent with the results of Brender and Drazen (2005).

Finally, we examined the role of globalization, as it might constrain the government’s ability to behave opportunistically (Potrafke 2009). We rely on the KOF Economic Globalization Index, which measures the economic dimensions of globalization (see Gygli et al. 2019 for further details). It ranges between 0 and 100 and contains measures of both de facto and de jure trade and financial globalization.Footnote 28 To capture the impact of globalization in the model, we created a dummy variable based on the index’s median indicating whether a country’s exposure to globalization was high (Z = 1) or low (Z = 0). The results shown in Fig. 5g suggest that fiscal rules do not restrain PBCs in countries that are less affected by globalization. However, in more globalized economies they constrain electoral incentives to manipulate fiscal policy.

Therefore, it seems that the constraining effect of fiscal rules on the occurrence of PBCs is different in the years before the global financial crisis, in new democracies, and in less globalized economies.

6 Conclusions

A long tradition of examining political budget cycles (PBCs) is evident in the literature. Like most of the recent contributions, we have focused on the conditionality of the relationship between elections and budget deficits. That is, for a sample of 77 (advanced and developing) countries over the 1984–2015 period and using data on fiscal rules provided by the IMF, we find that strong fiscal rules constrain political budget cycles. In addition, we confirm the findings of previous studies that fiscal rules in general improve the government budget balances. Because EU member states generally adopted more stringent fiscal rules than other nations, our results seem to be driven primarily by the former. Nevertheless, strong fiscal rules also constrain political budget cycles in non-EU countries.

We also examined the potential confounding effects of other conditional variables identified in the literature. We find that our results are remarkably robust to the inclusion of media freedom and the level of government debt. Furthermore, we find strong effects of fiscal rules in, amongst others, countries with fewer veto players, left-wing governments, established democracies, and more globalized economies. In addition, the effect of fiscal rules on political budget cycles seems to be stronger after the global financial crisis.

Our findings have clear policy implications. First, our confirmation of previous research finding that fiscal rules enhance fiscal discipline stresses the importance of those rules. Second, our finding that fiscal rules not only enhance public budget discipline but also moderate fiscal manipulations for election purposes offers perhaps even more important support for strengthening fiscal rules. At the same time, that finding also leads to another question: If fiscal rules constrain the incumbent, will they not be evaded? The index on which we rely considers only the design of fiscal rules and does not capture their actual efficacies. Nonetheless, Reuter (2015) shows that even though fiscal rules are not always complied with, they still force fiscal policy aggregates towards their numerical constraints in times of non-compliance. Moreover, de Jong and Gilbert (2020) show that when EU countries did not comply with the Stability and Growth Pact rules and entered the Excessive Deficit Procedure, the recommendations of the European Commission led to substantial fiscal consolidations. Those studies show that non-compliance with fiscal rules is not necessarily a sign of their ineffectiveness.

Finally, our analysis does not provide an answer to the question of whether supranational or national fiscal rules drive our results. An extensive discussion is ongoing in the literature about the effectiveness of supranational fiscal rules, notably the EU’s Stability and Growth Pact (see Koehler and König 2015 for a discussion of the literature). Whereas several studies conclude that the SGP’s rules had limited effects on fiscal discipline (see, for instance, de Haan et al. 2004), other studies reach more optimistic conclusions. For instance, Koehler and König (2015) conclude that the pact’s mechanism effectively has reduced the overall government debts of euro area countries since 1999. An interesting question for future research would be to ask whether supranational or national fiscal rules drive our results.

Notes

Not all theoretical PBC models are based on signaling competency. For instance, Drazen and Eslava (2010) develop a model in which politicians differ in the values they assign to different types of spending, but voters do not observe those preferences. By shifting the composition of spending towards the goods voters prefer, an incumbent politician will try to signal that his preferences are close to those of voters, implying that he will choose high post-election spending on those same goods. The evidence of Drazen and Eslava (2010) and some other studies discussed in de Haan and Klomp (2013) provide support for that mechanism.

Conditioning factors discussed in the literature include the transparency of budget institutions (Alt and Lassen 2006a, b), the age of democracy (Brender and Drazen 2005, 2013), political checks and balances (Streb et al. 2009) and media freedom or quality (Shi and Svensson 2006; Veiga et al. 2017; Repetto 2018).

As to the capacity, contrary to the standard assumption in PBC models that expansionary fiscal policies will strengthen electoral support for the incumbent, Peltzman (1992) argues that US voters punish politicians who let government spending increase, no matter whether that increase is financed by taxes or debt. Brender and Drazen (2008) report similar findings for a sample of 74 countries. However, focusing on support for the political parties in government instead of the prime minister’s party, Klomp and de Haan (2013) report that expansionary fiscal policies increase electoral support for incumbents.

Gimmicks “are a variety of (more or less deliberate) attempts by governments to improve the appearance of their public finance statistics (e.g., the goverment’s budget balance or public debt) through actions that have no substantive effect on their real underlying fiscal position” (Alt et al. 2014, p. 709). Several studies report evidence that the SGP has not prevented election-motivated fiscal policy manipulations (cf. Mink and de Haan 2006; Efthyvoulou 2012).

However, some studies reach less optimistic conclusions. For instance, Eliason and Lutz (2018) do not find evidence that one of the most stringent sets of fiscal rules in the United States, i.e., Colorado’s Taxpayer Bill of Rights, affected the levels of taxing or spending there. Likewise, based on answers from 639 politicians who provided responses about compliance with Germany’s debt brake for its 16 federal states, Heinemann et al. (2016) report that the debt brake’s credibility among policy makers is far from perfect.

Some evidence in favor of the effect of fiscal rules on fiscal manipulation at the subnational level has been reported. Using data from US states, Rose (2006) finds that PBCs are nearly absent in states adopting prohibitions on deficit carry-overs in combination with borrowing restrictions. Similar results are reported by Alt and Rose (2007, p. 862), who conclude that the fiscal rule set “remains the biggest single contextual difference we find in the estimated magnitudes of political budget cycles” across states. Likewise, based on data from Italian municipalities, Bonfatti and Forni (2019) conclude that fiscal rules moderate the PBC. However, using a sample of Spanish municipalities, Benito et al. (2013) report that a balanced budget rule has not dampened electoral cycles.

See Table A1 in the online appendix for a list of all countries and Table A2 for the summary statistics.

Our main results are not driven by the inclusion of the two countries, for which we observed extreme outliers in the primary budget balance (budget surpluses of 28.2% and 40.6% in 2006, respectively, following sharp increases in government revenues). The results including Mali and Niger are available on request.

Results using the overall budget balance are similar and available upon request.

Several sensitivity analyses using alternative election dummy variables indicate that ignoring the timing of elections does not capture the impact of elections on the budget properly (results available on request). That is, if only the (pre-) election year is considered, the effects of elections on the budget balance vanish. However, the effect of elections becomes significant (in both years) when the election and pre-election years are considered jointly. Furthermore, the budgetary impact of elections seems to be similar in the election and pre-election years. Those analyses therefore support the conclusion that scholars have to take the timing of elections into account (Franzese 2000).

Schaechter et al. (2012) suggest not including the flexibility measures in the aggregated fiscal rules index. Flexible rules may not be equally suited for all countries. In addition, flexibility creates new challenges for monitoring and effective implementation. However, in the literature on the design of optimal fiscal rules, some considerations have been put forward explaining why flexible fiscal rules may be desirable. Very stringent fiscal rules can tie the hands of policymakers too tightly during economic downturns and could promote ineffective (procyclical) fiscal policies. It appears that fiscal rules considering the cyclical component and excluding public infrastructure spending from the expenditure ceiling are more effective in promoting sound fiscal policy (Guerguil et al. 2017). As flexibility seems to play a role in the effectiveness of fiscal rules, we enter fiscal rules indexes that include flexibility as our preferred specification, in line with Bergman and Hutchison (2015). However, results excluding flexibility from the fiscal index are similar and available upon request.

All observations in the IMF’s fiscal rules database are 0–1 dummies, except for ‘coverage’ and ‘legal basis’ of the fiscal rule. ‘Coverage’ takes on three different values: no coverage = 0, central government = 1, general government or wider = 2. The numbers may be adjusted upward by 0.5 to account for similar rules applying to different governmental levels. ‘Legal basis’ takes on five different values: political commitment = 1, coalition agreement = 2, statutory rule = 3, international treaty = 4, constitutional rule = 5.

We also considered assigning equal weight to every element of the aggregate fiscal rules index. Results with equal weights are similar and available upon request.

Our main conclusions remain unchanged when we omit the lagged government budget balance from the model (results available upon request).

In the regressions, we enter the contemporaneous fiscal rules index. If fiscal rules bite, they are more likely to do so in the same year to which our fiscal policy variable refers.

Violations from the mean stationarity assumption could be detected based on Sargan’s or Hansen’s tests of overidentifying restrictions, but those tests (can) have very low power when the number of instruments increases (Bun and Sarafidis 2013). As our sample covers 31 years, the number of instruments would be rather large.

Although the marginal effect for revenue rules also is significant, those results are less meaningful in view of the large number of countries with scores of zero for that rule.

Hainmueller et al. (2019) discuss how the estimates of multiplicative interaction models may be misleading, as interactions models might suffer from (1) assuming that the interaction effect is linear and (2) lacking variation across the moderator variable.

Note that the LSDVC estimator is calculated with bootstrap standard errors (non-clustered), whereas FE estimation and GMM estimation correct for potential heteroscedasticity using clustered robust standard errors. This could possibly explain the minor differences between the LSDVC and the FE estimation results. Although the results of the FE estimation using classic standard errors (available upon request) and clustered robust standard errors do not differ a lot, the model seems to improve little using clustered robust standard errors. Unfortunately, to the best of our knowledge, no LSDVC package is available allowing for clustered standard errors.

Unfortunately, we cannot check for excessive upward or downward bias in the estimated conditional marginal effects, since the estimation strategy of Hainmueller et al. (2019) cannot be applied to three-way interactions.

We also entered the media freedom index from the Global Media Freedom Dataset of the Media Freedom Resource Centre (MFRC), which reports data from 1948 to 2014. We find similar results using that index but end up with fewer observations because information for 2015 is missing. As a further robustness check, we tried two combinations of Freedom House’s index and MFRC’s index because the former’s press status variable is available only from 1989 onwards: (1) we replace Freedom House’s index with MFRC’s index when observations are missing, and (2) we enter a weighted average of the two indexes. Combining the two indexes, however, is not our preference. The correlation between Freedom House’s and MFRC’s index is 0.753, which is high, but also indicates that the indexes do not fully overlap. Moreover, the loss of observations using Freedom House’s index is small (i.e., 26 observations). The results in all cases, however, remain similar and are available upon request.

Bohn and Veiga (2019, p. 430) argue that incumbent governments carrying heavy public debt loads may behave more opportunistically in election years than those with less debt when confronted with a looming recession because “high-debt governments face recessions frequently.”

We thank one of the referees for this suggestion.

We lose 277 observations (and seven countries) when relying on the proxy. To the best of our knowledge, no better proxy is available for political orientation, given our panel.

To test that possibility, we examined whether the election effect in the baseline model differs across the two periods. To do so, we tested the model excluding the interaction with the fiscal rules index. The interaction term between the elections variable and the GFC dummy turns out to be insignificant (results available on request), suggesting that the effect of elections on fiscal policy is the same before and after the crisis. Those results contrast with the findings of Janků and Libich (2019).

We consider the 2009–2015 period as post-GFC years, in line with Janků and Libich (2019). Other specifications of post-GFC years (i.e., the 2007–2015 and 2008–2015 periods) yield similar results (available upon request).

De facto trade globalization is determined by trade in goods and services, while de jure trade globalization includes customs duties, taxes and trade restrictions. De facto financial globalization includes foreign investment in several categories, while de jure financial globalization is based on investment restrictions, openness of the capital account and international investment agreements.

References

Ademmer, E., & Dreher, F. (2016). Constraining political budget cycles: Media strength and fiscal institutions in the enlarged EU. Journal of Common Market Studies, 54, 508–524.

Ahn, S. C., & Schmidt, P. (1995). Efficient estimation of models for dynamic panel data. Journal of Econometrics, 68, 5–27.

Alt, J. E., & Lassen, D. D. (2006a). Fiscal transparency, political parties, and debt in OECD countries. European Economic Review, 50, 1403–1439.

Alt, J. E., & Lassen, D. D. (2006b). Transparency, political polarization, and political budget cycles in OECD countries. American Journal of Political Science, 50, 530–550.

Alt, J. E., Lassen, D. D., & Wehner, J. (2014). It isn’t just about Greece: Domestic politics, transparency, and fiscal gimmickry. British Journal of Political Science, 44, 707–716.

Alt, J. E., & Rose, S. S. (2007). Context-conditional political business cycles. In C. Boix & S. C. Stokes (Eds.), Oxford handbook of comparative politics (pp. 845–867). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Altunbas, Y., & Thornton, J. (2017). Why do countries adopt fiscal rules? The Manchester School, 85, 65–87.

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies, 58, 277–297.

Asatryan, Z., Castellón, C., & Stratmann, T. (2018). Balanced budget rules and fiscal outcomes: Evidence from historical constitutions. Journal of Public Economics, 167, 105–119.

Azzimonti, M., Battaglini, M., & Coate, S. (2016). The costs and benefits of balanced budget rules: Lessons from a political economy model of fiscal policy. Journal of Public Economics, 136, 45–61.

Benito, B., Bastida, F., & Vicente, C. (2013). Creating room for manoeuvre: A strategy to generate political budget cycles under fiscal rules. Kyklos, 66, 467–496.

Bergman, M., & Hutchison, M. (2015). Economic stabilization in the post-crisis world: Are fiscal rules the answer? Journal of International Money and Finance, 52, 82–101.

Blundell, R. W., & Bond, S. R. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87, 115–143.

Bohn, F., & Veiga, F. J. (2019). Elections, recession expectations and excessive debt: An unholy trinity. Public Choice, 180, 429–449.

Bonfatti, A., & Forni, L. (2019). Fiscal rules to tame the political budget cycle: Evidence from Italian municipalities. European Journal of Political Economy, 60, 101800.

Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analysis. Political Analysis, 14, 63–82.

Brender, A., & Drazen, A. (2005). Political budget cycles in new versus established democracies. Journal of Monetary Economics, 52, 1271–1295.

Brender, A., & Drazen, A. (2008). How do budget deficits and economic growth affect reelection prospects? Evidence from a large cross-section of countries. American Economic Review, 98, 2203–2220.

Brender, A., & Drazen, A. (2013). Elections, leaders, and the composition of government spending. Journal of Public Economics, 97, 18–31.

Bun, M., & Kiviet, J. F. (2003). On the diminishing returns of higher-order terms in asymptotic expansions of bias. Economics Letters, 79, 145–152.

Bun, M., & Sarafidis, V. (2013). Dynamic panel data models. UvA-econometrics working papers 13/01. University of Amsterdam.

Caselli, F., & Reynaud, J. (2019). Do fiscal rules cause better fiscal balances? A new instrumental variable strategy. IMF working paper 19/49.

Cruz, C., Keefer, P., & Scartascini, C. (2018). Database of political institutions 2017. Inter-American Development Bank.

de Haan, J., Berger, H., & Jansen, D. (2004). Why has the stability and growth pact failed? International Finance, 7(2), 235–260.

de Haan, J., & Klomp, J. (2013). Conditional political budget cycles: A review of recent evidence. Public Choice, 157, 387–410.

de Haan, J., & Klomp, J. (2016). Election cycles in natural resource rents: Empirical evidence. Journal of Development Economics, 121, 79–93.

de Jong, J. F. M., & Gilbert, N. D. (2020). Fiscal discipline in EMU? Testing the effectiveness of the excessive deficit procedure. European Journal of Political Economy, 61, 101822.

Debrun, X., Moulin, L., Turrini, A., Ayuso-i-Casals, J., & Kuma, M. S. (2008). Tied to the mast? The role of national fiscal rules in the European Union. Economic Policy, 23, 298–362.

Drazen, A., & Eslava, M. (2010). Electoral manipulation via voter-friendly spending: Theory and evidence. Journal of Development Economics, 92, 39–52.

Dubois, E. (2016). Political business cycles 40 years after Nordhaus. Public Choice, 166, 235–239.

Efthyvoulou, G. (2012). Political budget cycles in the European Union and the impact of political pressures. Public Choice, 153, 295–327.

Eliason, P., & Lutz, B. (2018). Can fiscal rules constrain the size of government? An analysis of the “crown jewel” of tax and expenditure limitations. Journal of Public Economics, 166, 115–144.

Fatas, A., & Mihov, I. (2006). The macroeconomic effects of fiscal rules in the US states. Journal of Public Economics, 90, 101–117.

Franzese, R. J. (2000). Electoral and partisan manipulation of public debt in developed democracies, 1956–90. In R. Strauch & J. von Hagen (Eds.), Institutions, politics and fiscal policy. New York: Springer.

Franzese, R. J. (2002). Electoral and partisan cycles in economic policies and outcomes. Annual Review of Political Science, 5, 369–421.

Guerguil, M., Mandon, P., & Tapsoba, R. (2017). Flexible fiscal rules and countercyclical fiscal policy. Journal of Macroeconomics, 52, 189–220.

Gygli, S., Haelg, F., Potrafke, N., & Sturm, J.-E. (2019). The KOF globalisation index-revisited. Review of International Organizations, 14, 543–574.

Hainmueller, J., Mummolo, J., & Xu, Y. (2019). How much should we trust estimates from multiplicative interaction models? Simple tools to improve empirical practice. Political Analysis, 27, 163–192.

Hammond, G. (2012). State of the art of inflation targeting. CCBS handbook (Vol. 29). London: Centre for Central Banking Studies, Bank of England.

Heinemann, F., Janeba, E., Schröder, C., & Streif, F. (2016). Fiscal rules and compliance expectations—Evidence for the German debt brake. Journal of Public Economics, 142, 11–23.

Heinemann, F., Moessinger, M., & Yeter, M. (2018). Do fiscal rules constrain fiscal policy? A meta-regression analysis. European Journal of Political Economy, 51, 69–92.

Janků, J., & Libich, J. (2019). Ignorance isn’t bliss: Uninformed voters drive budget cycles. Journal of Public Economics, 173, 21–43.

King, G., & Zeng, L. (2006). The dangers of extreme counterfactuals. Political Analysis, 14(2), 131–159.

Klomp, J., & de Haan, J. (2013). Political budget cycles and election outcomes. Public Choice, 157, 245–267.

Koehler, S., & König, T. (2015). Fiscal governance in the Eurozone: How effectively does the stability and growth pact limit governmental debt in the euro countries? Political Science Research and Methods, 3(2), 329–351.

Li, Q., & Racine, J. S. (2010). Smooth varying-coefficient estimation and inference for qualitative and quantitative data. Economic Theory, 26, 1607–1637.

Lowry, R. C., & Alt, J. E. (2001). A visible hand? Intertemporal efficiency, costly information, and market-based enforcement of balanced-budget laws. Economics and Politics, 13, 49–72.

Lucotte, Y. (2012). Adoption of inflation targeting and tax revenue performance in emerging markets economies: An empirical investigation. Economic Systems, 36, 609–628.

Mandon, P., & Cazals, A. (2019). Political budget cycles: Manipulation by leaders versus manipulation by researchers? Evidence from a meta-regression analysis. Journal of Economic Surveys, 33, 274–308.

Milesi-Ferretti, G. M. (2004). Good, bad or ugly? On the effects of fiscal rules with creative accounting. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 377–394.

Minea, A., & Villieu, P. (2009). Can inflation targeting promote institutional quality in developing countries? mimeo.

Mink, M., & de Haan, J. (2006). Are there political budget cycles in the euro area? European Union Politics, 7, 191–211.

Nordhaus, W. (1975). The political business cycle. Review of Economic Studies, 42, 169–190.

Peltzman, S. (1992). Voters as fiscal conservatives. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 57, 327–361.

Philips, A. Q. (2016). Seeing the forest through the trees: A meta-analysis of political budget cycles. Public Choice, 168(3–4), 313–341.

Potrafke, N. (2009). Did globalization restrict partisan politics? An empirical evaluation of social expenditures in a panel of OECD countries. Public Choice, 140, 105–124.

Repetto, L. (2018). Political budget cycles with informed voters: Evidence from Italy. The Economic Journal, 128, 3320–3353.

Reuter, W. H. (2015). National numerical fiscal rules: Not complied with, but still effective? European Journal of Political Economy, 39, 67–81.

Rose, S. (2006). Do fiscal rules dampen the political business cycle? Public Choice, 128, 407–431.

Schaechter, A., Kinda, T., Budina, N., & Weber, A. (2012). Fiscal rules in response to the crisis—Toward the “next-generation” rules. A new dataset. IMF working paper 12/187.

Shi, M., & Svensson, J. (2006). Political budget cycles: Do they differ across countries and why? Journal of Public Economics, 90, 1367–1389.

Streb, J. M., Lema, D., & Torrens, G. (2009). Checks and balances on political budget cycles: Cross-country evidence. Kyklos, 62, 425–446.

Streb, J. M., & Torrens, G. (2013). Making rules credible: Divided government and political budget cycles. Public Choice, 156, 703–722.

Veiga, F. J., Gonçalves Veiga, L., & Morozumi, A. (2017). Political budget cycles and media freedom. Electoral Studies, 45, 88–99.

Acknowledgements

We like to thank participants in the 2019 meeting of the European Public Choice Society in Jerusalem, and especially our discussant, Lamar Crombach, as well as two anonymous referees for their very helpful comments on a previous version of the paper. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the views of De Nederlandsche Bank.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gootjes, B., de Haan, J. & Jong-A-Pin, R. Do fiscal rules constrain political budget cycles?. Public Choice 188, 1–30 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-020-00797-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-020-00797-3