Abstract

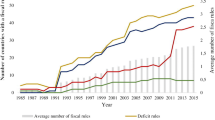

In recent years, several countries have enacted numerical fiscal rules, which set limits for government expenditure, revenue, deficits and debt. According to both proponents and critics of these rules, they are a tool to depoliticize fiscal policy and perhaps the political system more broadly, by forcing political parties to adopt increasingly similar political positions. However, little empirical research has been done on whether the introduction of fiscal rules actually affects countries’ internal political life. This article explores whether fiscal rules do, in fact, cause legislative parties to adopt similar political positions, by testing the effects of fiscal rules on the level of political polarization. Using party manifestos data from 185 elections in 32 OECD countries, this article finds little robust evidence that fiscal rules independently reduce the level of political polarization within national legislatures. Contrary to popular arguments about fiscal rules and depoliticization, there is little evidence for an independent effect of fiscal rules on the variance of political parties’ positions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Which are in place in several countries, including Denmark, Sweden and Australia (Bova et al. 2015).

In place in France since 2006 (Bova et al. 2015, 28).

The issue of depoliticization of national democratic politics is a growing discussion and research agenda in both positive and normative political science; see Wood (2016). But this phenomenon’s potential relationship to fiscal rules remains under-researched.

See Layman et al. (2006) for a review.

A version of such a golden rule of public borrowing was present in the Germany constitution from 1969 to 2010 and was amended in 2011 (Bova et al. 2015, 30).

Such rules were adopted by law in Sweden from 2010 (Bova et al. 2015, 63).

An example includes the debt limit in the Polish constitution of 1999 (Bova et al. 2015, 54).

A recent exception is Aaskoven (2019).

The degree for which incumbent government is constrained by external forces should also determine the extent to which voters hold governments responsible for the state of the national economy; see Kosmidis (2018) for a discussion of this literature and a contrarian view.

For a wider discussion of the budgetary reforms in Sweden, see Wehner (2007).

I am grateful to one of the reviewers for pointing this mechanism out.

The midpoint of the original left–right scale is used by Dalton. However, this specific denominator value is not important for the index.

Formally, \({\text{Polarization}} = \sqrt {\mathop \sum \limits_{p} {\text{size}}_{p} *\left( {\frac{{{\text{position}}_{p} - {\text{average position}}}}{5}} \right)^{2} }\), where party is indexed by p.

Concretely, the variable measures the parties' positions on two categories in the Manifestos dataset, per503 about positive attitudes toward equality and equality-promoting approaches to public policy and per504 about favorable mentions of introduction, maintenance and expansion of public services and social security programs (Volkens et al. 2015b). Recent research by Horn et al. (2017) also suggests that the welfare indicator is a valid measure of political parties’ positions within these areas.

“Appendix 1” also contains an overview of polarization for each country over the time period using the measures of polarization used in this article.

Such as a so-called Golden Rule which states that the government can only borrow to fund public investment rather than public consumption. Such a rule is used to be a part of the German constitution (Bova et al. 2015, 30).

The amendment to the European Union’s fiscal rules put down in the so-called Fiscal Compact of 2012 required the states signing this agreement to implement the supranational fiscal rules of the European Union into their national fiscal frameworks, which might make the distinction between national and supranational fiscal rules blurry for these countries. However, since the coverage of this article’s dataset ends in 2012, this is not an issue for this analysis.

Although Curini and Hino (2012) argue that this relationship is conditional on minority/majority government dynamics.

Unit roots’ tests also suggest that the four fiscal rules variables are not stationary over the analyzed time period.

Results are available from the author upon request.

In the above estimation, political polarization and fiscal rules are measured in the same year. However, as suggested by one of the reviewers, parties might be working their manifestos at least a couple of years before an election and would therefore take potential fiscal rules, which are in place then, into account. However, if the fiscal rules variables are lagged either 1 or 2 years and the estimations in Tables 2 and 3 redone, there is still usually (but not always) no statistically significant effect of fiscal rules on political polarization, and this is always the case when the four types of fiscal rules are analyzed simultaneously. Results are available upon request.

This result is robust to controlling for the size of the public sector as a percent of GDP, which could also be effected by increased levels of economic development (Boix 2001).

From the Comparative Political Dataset (Armingeon et al. 2015).

Results are available upon request.

I am grateful to one of the reviewers for pointing this issue out.

Which also contains issues such as reduction in deficits and fiscal retrenchment in crisis (Volkens et al. 2015b).

An expenditure rule might of course be the most effective of the fiscal rules in restraining public finances; see Bäck and Lindvall (2015, 65). However, a balanced budget rule ties more directly to the issue of reducing public deficits, which is part of the Manifestos Project's market economy dimension, and this fiscal rule does not seem to have a statistically significant effect within this dimension.

This article has concerned independent effects of fiscal rules on polarization. An extra analysis, where the fiscal rules variables are interacted with the type of fiscal policy aggregate they concern (public expenditure, public revenue, government net lending (deficit) and government debt), suggests that expenditure rule and debt rules might actually decrease polarization when, respectively, government expenditure and government debt reach high levels. Results are available upon request.

A reviewer suggested that fiscal rules might not affect the variance of voters' ideological position and this could be the reason for the lack of an effect of fiscal rules on partisan polarization. An auxiliary analysis of the effect of fiscal rules on voter polarization found in Appendix D gives very inclusive evidence for whether fiscal rules affect the variance of voters' ideological positions. This analysis uses the standard deviation of voters' left–right placement as the dependent variable based on data from the Eurobarometer. I am grateful to Roni Lehrer for providing these data.

Including a decrease in electoral turnout (Aaskoven 2019).

For evidence for this phenomenon from developing countries, see Hyde and O'Mahoney (2010).

Also used by Ward et al. (2015).

In some cases, such as the German experience with a “grand coalition,” the two largest parties might be in government together. However, in most of these cases the parties usually formulate their election year position and electoral platform as if they would continue in government without their coalition partner.

Results are available upon request.

See Alt and Lassen (2006a) for an account of the link between polarization and fiscal policy.

References

Aaskoven, Lasse. 2019. Fiscal Rules and Electoral Turnout. Political Science Research and Methods. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2019.27.

Altunbas, Yener, and John Thornton. 2017. Why Do Countries Adopt Fiscal Rules? The Manchester School 85 (1): 65–67.

Alt, James E., and David Dreyer Lassen. 2006a. Fiscal Transparency, Political Parties, and Debt in OECD Countries. European Economic Review 50: 1403–1439.

Alt, James E., and David Dreyer Lassen. 2006b. Transparency, Political Polarization, and Political Budget Cycles in OECD Countries. American Journal of Political Science 50 (3): 530–550.

Angrist, Joshua D., and Jörn-Steffen Pischke. 2009. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Armingeon, Klaus, Christian Isler, Laura Knöpfel, David Weisstanner, and Sarah Engler. 2015. Comparative Political Data Set 1960–2013. Bern: Institute of Political Science, University of Berne.

Asatryan, Zareh, Cesar Castellon and Thomas Stratmann. 2016. Balanced Budget Rules and Fiscal Outcomes: Evidence from Historical Constitutions. ZEW discussion paper no. 16-034.

Beck, Thorsten, George Clarke, Alberto Groff, Philip Keefer, and Patrick Walsh. 2001. New Tools in Comparative Political Economy: The Database of Political Institutions. World Bank Economic Review 15 (1): 165–176.

Bergman, U.Michael, and Michael Hutchison. 2015. Economic Stabilization in the Post-crisis World: Are Fiscal Rules the Answer? Journal of International Money and Finance 52: 82–101.

Boix, Carles. 2001. Democracy, Development and the Public Sector. American Journal of Political Science 45 (1): 1–17.

Bova, Elva, Tidiane Kinda, Priscilla Muthoora, and Frederik Toscani. 2015. Fiscal Rules at a Glance. Washington DC: International Monetary Fund.

Bäck, Hanna, and Johannes Lindvall. 2015. Commitment Problems in Coalitions: A New Look at the Fiscal Policies of Multiparty Government. Political Science Research and Methods 3 (1): 53–72.

Campante, Filipe and Dani Rodrik. 2017. Brazil’s Argentina Moment. Project Syndicate, 8th June 2017.

Canes-Wrone, Brandice, and Jee-Kwang Park. 2012. Electoral Business Cycles in OECD Countries. American Political Science Review 106 (1): 103–122.

Chowdhury, Anis and Iyanatul Islam. 2012. Fiscal Rules—Help or hindrance? VOX, CEPR’s Policy Portal, 4th October 2012.

Curini, Luigi, and Airo Hino. 2012. Missing Links in Party-System Polarization: How Institutions and Voters Matter. Journal of Politics 74 (2): 460–473.

Dalgaard, Carl-Johan, and Ola Olsson. 2013. Why Are Rich Countries More Politically Cohesive? Scandinavian Journal of Economics 115 (2): 423–448.

Dalton, Russell J. 2008. The Quantity and the Quality of Party Systems: Party System Polarization, Its measurement, and Its Consequences. Comparative Political Studies 41 (7): 899–920.

Debrun, Xavier, Laurent Moulin, Alessandro Turrini, Joaquim Ayuso-I-Casals, and Manmohan S. Kumar. 2008. Tied to the Mast? National Fiscal Rules in the European Union. Economic Policy 23 (54): 297–362.

Dreher, Axel. 2006. Does Globalization Affect Growth? Evidence from a New Index of Globalization. Applied Economics 38 (10): 1091–1110.

Dreher, Axel. 2009. IMF Conditionality: Theory and Evidence. Public Choice 141 (1): 233–267.

Ezrow, Lawrence, Margit Tavits, and Jonathan Homola. 2014. Voter Polarization, Strength of Partisanship, and Support for Extremist Parties. Comparative Political Studies 47 (11): 1558–1583.

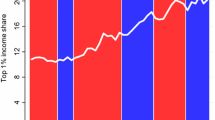

Fenzl, Michele. 2018. Income Inequality and Party (de)Polarisation. West European Politics 41 (6): 1262–1281.

Fernandez-Albertos, Jose. 2015. The Politics of Central Bank Independence. Annual Review of Political Science 18: 217–237.

Hallerberg, Mark, and Nicole Rae Baerg. 2016. Explaining Instability in the Stability and Growth Pact: The Contribution of Member State Power and Euroskepticism to the Euro Crisis. Comparative Political Studies 49 (7): 968–1009.

Hallerberg, Mark, Rolf R. Strauch, and Jürgen von Hagen. 2009. Fiscal Governance in Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Han, Sung Min. 2015. Income Inequality, Electoral Systems and Party Polarization. European Journal of Political Research 54: 582–600.

Hauptmeier, Sebastian, A. Jesuse Sanchez-Fuentes, and Ludger Schuknecht. 2011. Towards Expenditure Rules and Fiscal Sanity in the Euro Area. Journal of Policy Modelling 33: 597–617.

Häusermann, Silja, Thomas Kurer, and Bruno Wüest. 2018. Participation in Hard Times: How Constrained Government Depresses Turnout Among the Highly Educated. West European Politics 41 (2): 448–471.

Heinemann, Friedrich, Marc-Daniel Moessinger, and Mustafa Yeter. 2018. Do Fiscal Rules Constrain Fiscal Policy? A Meta-regression-Analysis. European Journal of Political Economy 51: 69–92.

Horn, Alexander, Anthony Kevins, Carsten Jensen, and Kees Van Kersbergen. 2017. Research Note: Peeping at the Corpus—What is Really Going on Behind the Equality and Welfare Items of the Manifestos Project? Journal of European Social Policy 27 (5): 403–441.

Hyde, Susan D., and Angela O’Mahoney. 2010. International Scrutiny and Pre-electoral Fiscal Manipulation in Developing Countries. The Journal of Politics 72 (3): 690–704.

Indridason, Indridi H. 2011. Coalition Formation and Polarisation. European Journal of Political Research 50: 689–718.

Keefer, Philip. 2013. DPI2012 Database of Political Institutions: Changes and Variable Definitions. The World Bank.

Koehler, Sebastian, and Thomas König. 2015. Fiscal Governance in the Eurozone: How Effectively Does the Stability and Growth Pact Limit Governmental Debt in the Euro Countries? Political Science Research and Methods 3 (2): 329–351.

Kopits, George. 2001. Fiscal Rules: Useful Policy Framework or Unnecessary Ornament? IMF working paper 01/145.

Kosmidis, Spyros. 2018. International Constraints and Electoral Decisions: Does the Room to Maneuver Attenuate Economic Voting? American Journal of Political Science 62 (3): 519–534.

Layman, Geoffrey C., Thomas M. Carsey, and Juliana Menasce Horowitz. 2006. Party Polarization in American Politics. Annual Review of Political Science 9: 83–110.

Lindqvist, Erik, and Robert Östling. 2010. Political Polarization and the Size of Government. American Political Science Review 104 (3): 543–565.

Marshall, John, and Stephen D. Fisher. 2015. Compensation or Constraint? How Different Dimensions of Economic Globalization Affect Government Spending and Electoral Turnout. British Journal of Political Science 45 (2): 353–389.

Martin, Lanny W., and Randolph T. Stevenson. 2001. Government Formation in Parliamentary Democracies. American Journal of Political Science 45 (1): 33–50.

Matakos, Konstantinos, Orestis Troumpounis, and Dimitros Xefteris. 2016. Electoral Rule Disproportionality and Platform Polarization. American Journal of Political Science 60 (4): 1026–1043.

Pontusson, Jonas, and David Rueda. 2008. Inequality as a Source of Political Polarization: A Comparative Analysis of Twelve OECD Countries. In Democracy, Inequality, and Representation: A Comparative Perspective, ed. Christopher Anderson and Pablo Beramendi. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Reuter, Wolf Heinrich. 2015. National Numerical Fiscal Rules: Not Complied with, but Still Effective? European Journal of Political Economy 39: 67–81.

Schaechter, Andrea, Tidiane Kinda, Nina Budina and Anke Weber. 2012. Fiscal Rules in Response to the Crisis—Towards the “Next-Generation” Rules. A New Dataset. IMF working paper 12/187.

Sen, Sedef, and Colin M. Barry. 2018. Economic Globalization and the Economic Policy Positions of Parties. Party Politics. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068818761179.

Solt, Frederick. 2009. Standardizing the World Income Inequality Database. Social Science Quarterly 90 (2): 231–242.

Stone, Randall W. 2008. The Scope of IMF Conditionality. International Organization 62 (4): 589–620.

Tavits, Margit, and Joshua D. Potter. 2015. The Effect of Inequality and Social Identity on Party Strategies. American Journal of Political Science 59 (3): 744–758.

Volkens, Andrea, Pola Lehmann, Theres Matthieß, Nicolas Merz, Sven Regel, and Annika Werner. 2015a. The Manifesto Data Collection. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). Version 2015a. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB).

Volkens, Andrea, Pola Lehmann, Theres Matthieß, Nicolas Merz, Sven Regel, and Annika Werner. 2015b. The Manifesto Project Dataset—Codebook. Manifesto Project (MRG/CMP/MARPOR). Version 2015a. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB).

Ward, Dalston, Jeong Hyun Kim, Matthew Graham, and Margit Tavits. 2015. How Economic Integration Affects Party Issue Emphases. Comparative Political Studies 48 (10): 1227–1259.

Wehner, Joachim. 2007. Budget Reform and Legislative Control in Sweden. Journal of European Public Policy 14 (2): 313–332.

Wood, Matthew. 2016. Politicisation, Depoliticisation and Anti-politics: Towards a Multilevel Research Agenda. Political Studies Review 14 (4): 521–533.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Peter Kurrild-Klitgaard, Martin Vinæs Larsen, Conor Little, Benjamin C. K. Egerod, seminar participants at the University of Copenhagen and three anonymous reviewers for suggestions, help and advice. All errors and shortcomings are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Polarization 1985–2014 by country

Appendix 2: Robustness tests

While the previous estimations control for a wide variety of potential confounders of political polarization, concerns might be raised that these variables only concern domestic correlates of political polarization, while international sources of both changes to fiscal rules and political polarization are left out. However, international factors such as level of economic globalization and foreign trade reliance (Ward et al. 2015) and the influence of international organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the European Union might be simultaneously correlated with both domestic political polarization and the extent to which countries enact fiscal rules. Particularly, countries undergoing an IMF lending program might be constrained in their fiscal policy,Footnote 32 which could affect political polarization, and countries receiving IMF aid might, because of the conditions tied to the IMF’s lending programs,Footnote 33 be obliged to enact national fiscal rules. Furthermore, the supranational fiscal rules of the European Union’s Stability and Growth Pact might have had spillovers into the national fiscal rules’ framework and might also have affected domestic political polarization.

To explore these factors, in Table 4, the full estimations from Tables 2 and 3 are redone with controls for these international factors. These controls are international trade as a percentage of GDP, the KOF index of economic globalization (Dreher 2006),Footnote 34 whether the country is currently under an IMF program and whether the country is part of the Stability and Growth Pact. The inclusion of these variables does not change the results from Tables 2 and 3 much, with the exception that debt rule does become statistically significant at the p < 0.10 level with a positive coefficient when analyzing polarization on the welfare indicator when trade as percent of GDP and the KOF index are added to the estimation. However, given the relatively low level of statistical significance of the debt rule in these cases, and the fact that debt rule is only statistically significant in some estimations, this positive effect is more likely to reflect a statistical coincidence than a true effect.

Furthermore, with the exception of the Stability and Growth Pact, which does seem to decrease at least polarization on the rile indicator, these variables do not themselves seem to be statistically significantly associated with political polarization within the OECD. While the Stability and Growth Pact actually seems to matter for political polarization, it might reflect a depolarization effect of European integration in line with the arguments of Ward et al. (2015) rather than a pure effect of fiscal rules, which is plausible given the weak effects of the national fiscal rules.

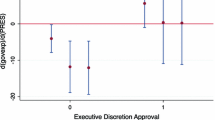

Party system polarization thus seems largely unaffected by the existence of national fiscal rules. However, a further argument might be made that the introduction of fiscal rules might affect some parties more than others and might especially be of concern for parties with an ambition to enter and especially lead a government and formulate national fiscal policy. In order to test this argument, in Table 5, instead of representing polarization as the aggregate distance between all legislative parties, I analyze fiscal rules’ effect on the absolute ideological distance between the two largest parties in the legislature. Since being the largest party is a key predictor of government formation (Martin and Stevenson 2001), and most OECD countries’ party systems typically have the two largest parties in different political blocs,Footnote 35 the distance between the two major parties would in most cases capture the ideological distance between the main government party and the main opposition party, who both aspire become a government party.

The results from Table 5, however, do not lend support to the above argument as neither of the fiscal rules variables is near any level of statistical significance. The results are similar if the rile indicator is replaced by the welfare indicator.Footnote 36 There seems to be no statistically significant either positive or negative effect of the introduction of the different types of fiscal rules on political polarization neither for overall left–right placement nor for parties’ positions on welfare and redistribution.

Judging from the results above, there seems to be weak evidence of an independent effect of national fiscal rules on political polarization, neither positive nor negative. However, even though national fiscal rules do not seem to be endogenous to several measures of globalization and the various control variables, some endogeneity concerns might still arise, especially with regards to uneven trends in polarization between countries. A causal interpretation of the above results, following a difference-in-difference logic, would rely on the assumption that there would be parallel trends in political polarization before fiscal rule adoption both in countries which later adopted fiscal rules and the ones which did not (Angrist and Pischke 2009, 229–231). However, this assumption might not hold, as rising polarization might in itself be associated with an increased or decreased likelihood of actually implementing fiscal rules.Footnote 37 So, in order to test whether uneven trends in political polarization between countries which adopt fiscal rules and countries which do not might be driving the results, I rerun the full estimations from Tables 2, 3 and 5 adding country-specific time trends to the estimation; see Angrist and Pischke (2009, 238–239). The results are given in Table 6. However, adding these country-specific time trends does not cause the fiscal rules variables to attain any level of convention statistical significance. The inclusion of these country trends even makes the effect of revenue rule on welfare polarization statistically insignificant.

Appendix 3: Fiscal rules and polarization in other dimensions

Appendix 4: Fiscal rules and voter polarization

See Table 10.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aaskoven, L. Do fiscal rules reduce political polarization?. Comp Eur Polit 18, 630–658 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-019-00202-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-019-00202-4