Abstract

Existing theories of contesting elections typically treat all potential challengers as identical while under-playing the importance of political parties and primary contests. We offer a theory addressing these issues based on how the various actors in the process define and evaluate the probability of winning an election and the value of the office being contested. We test our theory by estimating a model predicting which of three responses a party that loses a legislative race makes in the next cycle: nominating the same candidate, nominating a new candidate, or nominating no one. We find substantial empirical support for our theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Interested readers should examine Squire and Hamm (2005) for more detail on these and other distinguishing features of U.S. state legislatures.

Given that candidates have the incentive to over-report their own independence in this process, we suspect this percentage underestimates the role of parties.

The threshold for competing, C i , can equivalently be conceived of as the expected cost of competing for office. Given this conception, a potential serious challenger would run if and only if B i −C i >0 (i.e., if the expected benefits of competing exceed the expected costs).

Some candidates may overestimate their chance of pulling off a surprising victory (Kazee 1980), but this mis-read of the “electoral tea leaves” likely does not extend to the party organization. As we noted, it is also possible that the perceived value of the seat provides some motivation for a candidate who sees no hope of winning the upcoming election, but is trying to lay the groundwork for a more serious race down the road. Allowing for this possibility, however, does not affect the predictions of our theoretical model.

Ideally, we would test our theory using data on individual potential challengers, but this is not feasible because the population of all potential challengers for a state legislative seat cannot be identified; only those candidates that actually compete can be observed. Moreover, even if we could identify all potential challengers, we cannot directly observe their perceived probability of winning. In short, the data necessary to conduct any meaningful analysis on individual potential challengers do not exist nor could they be effectively gathered. Thus, we rely on standard practice in scientific inquiry by developing predictions from our theory regarding observable behavior at the district level, and then evaluating whether the observed data are consistent with those predictions as a means to evaluate our theory.

This argument parallels the use of previous vote margin as a key predictor of the strategic retirement of incumbents (e.g., Mayhew 1974; Coates and Munger 1995) because the variable serves as an indicator of the vulnerability of the incumbent, which is likely to influence the probability that a strong challenger will emerge.

The relationship plotted in Fig. 1 is depicted as linear for convenience. Our theory implies a monotonic relationship, but is silent about whether it is linear or nonlinear.

The vertical axis of Panel C in Fig. 2 is not presented on a zero to one scale in order to make it more evident where the curve attains its maximum.

This conclusion becomes evident if the reader imagines that the horizontal axis in each of the panels in Fig. 1 is re-labeled winning party candidate quality (a continuous variable measured so that the left of the axis represents high quality and the right represents low). Then, if we were to assume, for simplicity, that any incumbent is stronger than every non-incumbent, we could draw a vertical line rising up from the horizontal axis that separates races with an incumbent (on the left) from races for an open seat (on the right). In Panel A, it makes no difference where this vertical line is drawn; the average probability of observing no challenger is always expected to be higher to the left of the line than to the right. The same is not true for Panels B and C due to the non-monotonic nature of the curves. In both panels, whether the average height of the curve to the left of the vertical line is higher or lower than the average height of the curve to the right depends on the location of the vertical line relative to the point at which the curve bends. Since the locations of the vertical line and the bend are unknown, no clear predictions can be made.

We use the term “Proposition” to denote general theoretical claims that are not directly tested in this paper. We label as a “Hypothesis” each specific claim that is tested empirically.

See Berry et al. (2000) for more discussion of this measure.

Potential challengers must base their decision about whether to run in an election on expectations about party control of government after the election is over. While party control occasionally changes after an election, stability is much more common. Thus, it is reasonable to presume that potential candidates expect party control to remain the same, and make their seat value calculations accordingly.

Nebraska’s legislature is coded as an upper chamber, since the sole chamber in a unicameral legislature should be at least as prestigious as the upper chamber in a bicameral legislature.

We define a major redistricting as a full statewide redistricting prompted by a decennial U.S. Census.

The multinomial logit model, while well suited to this type of dependent variable, does rely on the independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA) assumption. Small-Hsiao and Hausman tests of the IIA assumption in our analysis suggest little cause for concern, as associated p-values of the null hypothesis of no violation are all greater than 0.39. An alternative to multinomial logit is multinomial probit, which does not require the IIA assumption. However, Dow and Endersby (2004) argue that, although neither model should be considered uniformly preferred, the IIA property of multinomial logit is not particularly restrictive or problematic, and multinomial probit models are notoriously vulnerable to estimation problems. Kropko (2008) shows through Monte Carlo simulations that even when the IIA assumption is violated to a high degree, multinomial logit still generally performs as well or better than does multinomial probit. In addition, Quinn et al. (1999) and Keane (1992) note that multinomial probit models lacking choice-specific covariates—i.e., covariates that affect the utility of one choice/outcome on the dependent variable to individuals in the data set but not the utility of other choices/outcomes—suffer from weak identification, which may lead to misleading results. In our analysis, we have no choice-specific covariates. Finally, Coates and Munger (1995) effectively employ a multinomial logit in their analysis. Given all of this, we are confident in using the multinomial logit model here.

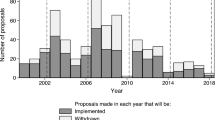

We explored several combinations of time period dummies, finding that whether we included a full set of such dummies, only dummies for even numbered years, or no such dummies did not affect our substantive results (see Tables S1, S2, and S3 of our unpublished supplement). The results we present include separate dummies for each even-numbered year. Making no effort to control for temporal effects seemed insufficient, yet the relatively small number of cases in each odd numbered year slowed the convergence of the likelihood function and meant that the coefficient estimates for those odd year dummies were based on few observations. E-mail request for unpublished supplement to carsey@unc.edu.

Indeed, our hypotheses do not generate clear predictions about most of coefficients in the model. This is because the coefficients represent the estimated effect of independent variables on the log of the odds of one outcome (repeat challenger, new challenger, or no challenger) relative to another, while most of our hypotheses concern the impact of independent variables on the absolute probability of one outcome rather than the relative probabilities of two outcomes.

Note that some of the independent variables are dummies. While the mean value of a dummy variable is greater than zero and less than one (unless the variable has no variance), and thus is not observed for any individual case, holding all dummies at their means when generating predicted probabilities reflects average conditions across observed cases. All predicted probabilities and significance tests regarding them were generated using CLARIFY (King et al. 2000; Tomz et al. 2001).

This difference in predicted probabilities is statistically significant at the 0.05 level. This conclusion is based on computing the difference between the predicted probabilities, constructing a 95 % confidence interval around this difference, and noting whether zero is contained within the interval. All subsequent claims regarding statistically significant differences in predicted probabilities are based on the same procedure.

This decline in the predicted probability of observing a new challenger from 0.69 to 0.65 when the losing vote share increases from 0.44 to 0.50, respectively, is statistically significant at the 0.05 level.

We have no strong post-hoc interpretation for why this occurs, but the bend in the curve at a vote share of 0.13 is statistically significant at the 0.05 level in the sense that the predicted probability of observing no challenger is significantly higher when the loser’s vote share is 0.13 than when the loser’s vote share is zero.

The dearth of cases for which loser’s vote share is less than 0.13 may account for why confidence intervals for predicted probabilities are relatively large in this range.

Some might be concerned with comparisons involving the highest and lowest observed values of legislative professionalism, since they may be outliers. As a robustness check, we calculated the difference between the predicted probability of observing no challenger when legislative professionalism is at its mean compared to when legislative professionalism is set at its tenth and ninetieth percentiles. Both differences (of 0.05 and 0.08, respectively) were statistically significant at the 0.05 level.

The difference when legislative professionalism is set at its tenth percentile is 0.50 and at its ninetieth percentile is 0.60, both of which are statistically significantly different from when legislative professionalism is set at its mean.

Examining incumbents in Congress, Coates and Munger (1995) find that an incumbent’s previous vote margin affects both the probability that she is defeated in the next election and the probability that she simply retires.

References

Adams, G. D., & Squire, P. (1997). Incumbent vulnerability and challenger emergence in senate elections. Political Behavior, 19(2), 97–111.

Banks, J. S., & Kiewiet, D. R. (1989). Explaining patterns of candidate competition in congressional elections. American Journal of Political Science, 33(4), 997–1015.

Baumann, Z. (2010). Institutions, attitudes, and career lengths: evidence from surveys of state house members in four states. Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Southern Political Science Association, Atlanta, GA, January 7–9.

Beck, N., Katz, J., & Tucker, R. (1998). Taking time seriously: time-series-cross-section analysis with a binary dependent variable. American Journal of Political Science, 42(4), 1260–1288.

Berry, W. D., Berkman, M. B., & Schneiderman, S. (2000). Legislative professionalism and incumbent reelection: the development of institutional boundaries. American Political Science Review, 94(4), 859–874.

Bianco, W. T. (1984). Strategic decisions on candidacy in US congressional districts. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 9(2), 351–364.

Black, G. S. (1972). A theory of political ambition: career choices and the role of structural incentives. American Political Science Review, 66(1), 144–159.

Born, R. (1986). Strategic politicians and unresponsive voters. American Political Science Review, 80(2), 599–612.

Born, R. (1977). House incumbents and inter-election vote change. The Journal of Politics, 39(4), 1008–1034.

Box-Steffensmeier, J. M. (1996). A dynamic analysis of the role of war chests in campaign strategy. American Journal of Political Science, 40(2), 352–371.

Canon, D. T. (1993). Sacrificial lambs or strategic politicians? Political amateurs in US House elections. American Journal of Political Science, 37(4), 1119–1141.

Carey, J. M., Niemi, R. G., & Powell, L. W. (2000). Incumbency and the probability of reelection in state legislative elections. Journal of Politics, 62(3), 671–700.

Carsey, T. M., Berry, W. D., Niemi, R. G., Powell, L. W., & Snyder, J. M. Jr. (2008a). State legislative returns, 1967–2003. ICPSR data set #21480.

Carsey, T. M., Niemi, R. G., Berry, W. D., Powell, L. W., & Snyder, J. M. Jr., (2008b). State legislative elections, 1967–2003: announcing the completion of a cleaned and updated dataset. State Politics and Policy Quarterly, 8(4), 430–443.

Coates, D., & Munger, M. C. (1995). Win, lose, or withdraw: a categorical analysis of career patterns in the House of Representatives, 1948–1978. Public Choice, 83(1/2), 95–111.

Dow, J. K., & Endersby, J. W. (2004). Multinomial probit and multinomial logit: a comparison of choice models for voting research. Electoral Studies, 23(1), 107–122.

Fiorina, M. P. (1994). Divided government and the American States: a byproduct of legislative professionalism? American Political Science Review, 88(2), 304–316.

Fox, R. L., & Lawless, J. L. (2005). To run or not to run for office: explaining nascent political ambition. American Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 6442–6459.

Hall, R. L., & Van Houweling, R. P. (1995). Avarice and ambition in congress: representatives’ decisions to run or retire from the US House. American Political Science Review, 89(1), 121–136.

Herrnson, P. S. (1988). Party campaigning in the 1980’s. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hogan, R. E. (2004). Challenger emergence, incumbent success, and electoral accountability in state legislative elections. Journal of Politics, 66(4), 1283–1303.

Holbrook, T. M., & Tidmarch, C. M. (1991). Sophomore surge in state legislative elections, 1968–86. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 16(1), 49–63.

Jacobson, G. C. (1989). Strategic politicians and the dynamics of US House elections, 1946–86. American Political Science Review, 83(3), 773–793.

Jacobson, G. C. (2009). Politics of congressional elections (7th ed.). New York: Pearson/Longman.

Jacobson, G. C., & Kernell, S. (1983). Strategy and choice in congressional elections (2nd ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press.

Kazee, T. A. (1980). The decision to run for the US Congress: challenger attitudes in the 1970s. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 5(1), 79–100.

Kazee, T. A. (1983). The deterrent effect of incumbency on recruiting challengers in US House elections. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 8(3), 469–480.

Kazee, T. A., & Thornberry, M. C. (1990). Where’s the party? Congressional candidate recruitment and American party organizations. Western Political Quarterly, 43(1), 61–80.

Keane, M. P. (1992). A note on identification in the multinomial probit model. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 10(2), 193–200.

King, G., Tomz, M., & Wittenberg, J. (2000). Making the most of statistical analyses: improving interpretation and presentation. American Journal of Political Science, 44(2), 347–361.

Krasno, J. S., & Green, D. P. (1988). Preempting quality challengers in house elections. The Journal of Politics, 50(4), 920–936.

Kropko, J. (2008). Choosing between multinomial logit and multinomial probit models for analysis of unordered choice data. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association, Chicago, April 3–6.

Lublin, D. I. (1994). Quality, not quantity: strategic politicians in US Senate elections, 1952–1990. The Journal of Politics, 56(1), 228–241.

Mack, W. R. (1998). Repeat challengers—are they the best challengers around? American Politics Quarterly, 26(3), 308–343.

Maestas, C. D., Maisel, L. S., & Stone, W. J. (2005). Strategic contact: national party efforts to recruit state legislators to run for the US House. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 30(2), 277–300.

Maestas, C. D., Fulton, S., Maisel, L. S., & Stone, W. J. (2006). When to risk it? Institutions, ambitions, and the decision to run for the US House. American Political Science Review, 100(2), 195–208.

Mayhew, D. R. (1974). Congress: the electoral connection. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Moncrief, G. F. (1999). Recruitment and retention in US legislatures. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 24(2), 173–208.

Quinn, K. M., Martin, A. D., & Whitford, A. B. (1999). Voter choice in multi-party democracies: a test of competing theories and models. American Journal of Political Science, 43(4), 1231–1247.

Sanbonmatsu, K. (2002). Political parties and the recruitment of women to state legislatures. The Journal of Politics, 64(3), 791–809.

Seligman, L., King, M., Kim, C., & Smith, R. (1974). Patterns of recruitment: a state chooses its lawmakers. Chicago: Rand McNally.

Squire, P. (1989). Competition and uncontested seats in US House elections. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 14(2), 281–295.

Squire, P. (2000). Uncontested seats in state legislative elections. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 25(1), 131–146.

Squire, P., & Hamm, K. E. (2005). 101 chambers: congress, state legislatures, and the future of legislative studies. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

Squire, P., & Smith, E. R. A. N. (1984). Repeat challengers in congressional elections. American Politics Quarterly, 12(1), 51–70.

Stone, W. J., & Maisel, L. S. (2003). The not-so-simple calculus of winning: potential US House candidates’ nomination and general election prospects. Journal of Politics, 65(4), 951–977.

Stone, W. J., Maisel, L. S., & Maestas, C. D. (2004). Quality counts: extending the strategic politician model of incumbent deterrence. American Journal of Political Science, 48(3), 479–495.

Taylor, A. J., & Boatright, R. G. (2005). The personal and the political in repeat congressional candidates. Political Research Quarterly, 58(4), 599–607.

Tomz, M., Wittenberg, J., & King, G. (2001). CLARIFY: software for interpreting and presenting statistical results. Version 2.0. Cambridge: Harvard University. http://gking.harvard.edu.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the Annual State Politics and Policy Conference at the University of Arizona, 2003, and the American Politics Research Group colloquium at the University of North Carolina, 2006. We would like to thank those that commented on the paper at that, as well as the anonymous reviewers, for their helpful suggestions. We would also like to acknowledge the support provided by two grants provided by the National Science Foundation (SES-0317924 and SES-0136526).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Carsey, T.M., Berry, W.D. What’s a losing party to do? The calculus of contesting state legislative elections. Public Choice 160, 251–273 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-013-0079-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-013-0079-5