Abstract

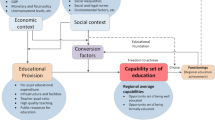

Nations transfer educational reform models for the systematic improvement of education. Nowhere is this more evident than in the Gulf Cooperation Council states, which have implemented primarily Western decentralized reform models to overhaul their educational systems. This article reports non-empirical research, written as a conceptual analysis that examines the current situation of the educational reform in Qatar. The theory of education transferring serves as a conceptual framework to scrutinize Qatar’s recent educational change to Project-based Learning. This illustrates the shift from the initial decentralized reform to its current centralized state. Contextual factors that influence decentralization are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The globalization of education has developed into a worldwide movement, giving countries the opportunity to transfer educational policies and practices with the hope of repairing and transforming their education systems. This has led to unprecedented transfers of education reform models that decentralize national education systems (Lee 2006; Steiner-Khamsi 2004). Decentralization can be defined as “the transfer of decision-making authority, responsibility, and tasks from higher to lower organizational levels or between organizations” (Hanson 1998, p. 12). In decentralized education systems, authority is shifted from a centralized authority such as a Ministry of Education to local governments or schools (Kirk 2013).

One result of this process is that educational policymakers use decentralized reform blueprints developed in a different cultural context without any serious consideration to the cultural fit (Dimmock and Walker 2000). Not only is the transferring of reforms endemic, but it lacks careful consideration about the context and ownership of each reform, making it more difficult to implement reform goals (McDonald 2012). Transferring understates the influence of culture, resulting in a “de-territorialization and decontextualization of reform” (Steiner-Khamsi 2004, p. 5). This raises the issue that “educational policies and practices that are effective in their original context may not prove effective elsewhere” (Romanowski, Alkhateeb, and Nasser 2018, p. 19).

This is often the case with transferred decentralized educational reforms. The appeal for decentralization is frequently framed from a Western vantage point, claiming that highly centralized education systems fail to address the developing challenges of rapid economic expansion (Tan 2012). Policymakers argue that decentralization provides enhancements to the educational systems through the vehicles of efficiency, accountability, effectiveness, and the redistribution of decision-making powers from a central authority to a local authority, which attains autonomy in the sphere of education (Haug 2009; Winkler 1993). This is evident in the Global South, where the determination to “transfer…decision-making authority, responsibility, and tasks from higher to lower organizational levels or between organizations” (Hanson 1998, p. 112) is mostly prescribed by outsourced educational reforms, which tend to disregard the indigenous community and epistemology. There is justification for decentralizing education; however, often the goals, strategies, and outcomes of decentralization differ from the contexts and cultures of the countries themselves (Dou, Devos, and Valcke 2017), leading to failure and a return to a centralized system of education (Yazdi 2013).

This article reports non-empirical research written in the context of conceptual analysis. We suggest that non-empirical methods such as reflection, personal observation, and authority and experience provide valuable forms of knowledge (Dan 2018). The objective of this article is to discuss Qatar’s decentralized education reform, using the theory of education transferring as a framework. We examine how Qatar’s reform embraced a transferred, decentralized reform model and discuss how the reform has gradually recentralized or shifted back to its original centralized system. First, we provide a discussion and rationale for the transferring or borrowing of education reforms, focusing on decentralization. Next, we discuss decentralization more directly, addressing Bray’s (2003) forms of decentralization, followed by a discussion of the benefits and challenges of implementing a decentralized reform. Then we discuss Qatar’s borrowed decentralized reform, Education for a New Era, initiated over a decade ago. We use the example of a recent national educational change to Project-based Learning (PBL) to describe how the recentralization of Qatar’s reform has impacted the classroom. Lastly, we explore and discuss contextual factors that may influence and constrain the ongoing educational reforms and the process of decentralization.

Educational policy transferring

Globalization has challenged the traditional view that nations can develop and achieve their national education goals unilaterally (Dale 2000; Rizvi and Lingard 2010). Instead, nations must rely on the cooperation and external influence of supranational agencies or other countries. This results in nations transferring or borrowing education reforms, policies, and practices, based on the belief that education reform models will improve not only their education systems but also their economic and social conditions (Abi-Mershed 2010; Hallinger and Bryant 2013; Tan 2014). An essential element of policy transferring is the deliberate adoption of a policy or practice from one setting to another (Phillips and Ochs 2003). Bennett (1997) argued that policy transferring incorporates external influences to alter domestic policy by merging policies from different countries. The process of transferring education reforms is not an end in itself but rather a means to develop education and improve the country’s capacity to compete regionally and globally (Khodr 2011).

Education transferring is evident in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states, which have engaged in broad-based reforms to overhaul their educational systems (Gonzalez et al. 2008). For example, the United Arab Emirates began a massive education reform plan, Vision 2020, in 1999, Bahrain started Schools of the Future in 2004, and Qatar’s reform Education for a New Era was established in 2002 (Sakr 2008). The vast majority of these educational reforms are primarily Western decentralized models that shift authority from a centralized education system to local governments or schools (Kirk 2013). More to the point, these reforms reflect “foreign models introduced by foreign consultants, without much consideration for the exigencies of the local context” (Aydarova 2013, as cited in Aydarova 2017, p. 4).

There is no shortage of criticism of policy transfer. The dominant criticism centers on the concern that education reforms, policies, and practices that were effective in the context where they were developed might not be effective elsewhere. Although transferring seems like a simple process, there are many obstacles. Transferring education reforms requires the entire government and its school systems to alter their traditional ways of operation. Also, school leaders and teachers may entirely “rely on systems developed for other educational contexts built on different educational and cultural views” (Ellili-Cherif, Romanowski, and Nasser 2012, p. 473), requiring them to replace one set of ideas or approaches with a much different one (McDonald 2012). Besides, when any education reform is implemented, school systems, educational leaders, and teachers must adapt or change to a new system (Avalos and Assael 2006; Tatto et al. 2006), challenging traditional values and norms.

Decentralization of education

Worldwide, education policy transferring has led to the adoption of decentralized education reforms. The push for community-level decentralization in education started in the US during the post-World War II era, motivated by political and economic concerns (Edwards and DeMatthews 2014), then gained popularity and accelerated during the neoliberal globalization of the 1980s (Burbules and Torres 2000). The international literature on education considers decentralization as “probably the single most advocated reform for improving the provision of such basic services as education and health in developing countries” (Chann 2016, p. 131). The specific form of decentralization varies in each context, but introducing a decentralized system requires both behavioral and institutional change (Florestal and Cooper 1997). A decentralized reform strategy is clearly political since it attempts to alter the status quo by transferring government authority. In education, decentralization requires a fundamental transformation of educational management and authority, demanding the introduction and implementation of a new management culture (Govinda 1997).

However, as Chann (2016) suggested, the development of education is a complex process, and using decentralization as a tool for improvement is still subject to debate. In developing countries, the call for educational decentralization is fueled by reports published by International Development Organizations, such as the World Bank and UNESCO, concerning the development of the Global South’s human resources. For the World Bank, decentralization in developing countries is a synonym for “improving efficiency, effectiveness and democracy” (Gershberg 2005, p. 2). Fiske (1996, p. v) states that:

Business leaders have discovered the limitations of large, centralized bureaucracies in dealing with rapidly changing market conditions. . . The worldwide recessions of the late 1980s and early 1990s have drawn attention to the crucial role of education in building sound economies, and experience has shown that many centralized systems of education are not working. A global debate about the proper role of the state has led to more emphasis on the concepts of free markets, competition, and even privatization.

In this sense, educational decentralization is a highly economical process that could result in significant changes to how school systems make policy, generate revenues, spend funds, and manage local schools. Decentralization of education promises improvement in “efficiency, transparency, accountability, and responsiveness of service provision compared with centralized systems” (World Bank Group 2001, para 2). UNESCO emphasized the democratic aspect of decentralization, linking it directly to political democratization as “people want to be consulted and involved in decision-making that concerns them directly” (McGinn and Welsh 1999, p. 10). As shown by these arguments, the rationale for educational decentralization involves serving markets through delivering accountability, efficiency, and effectiveness, all while achieving democracy.

It is widely rationalized that decentralization is a form of democratic governance. Smoke (1999) suggested that embedded in the declared benefits of decentralization “is the existence of democratic mechanisms that allow local governments to discern the needs and preferences of their constituents, as well as provide a way for these constituents to hold local governments accountable to them” (p. 10). The underlying assumption is that decentralization involves participatory approaches to educational governance, which are justified in terms of ensuring efficient management and accountability (Naidoo 2005). The key is the extent to which power and decision-making are transferred. More specifically, Bray (2003) noted three significant forms of decentralization:

-

1.

Deconcentration (transfer of tasks and work but not authority; schools are responsible for the implementation of policies and rules);

-

2.

Delegation (transfer of decision-making authority from higher to lower levels, but authority can be withdrawn by the center);

-

3.

Devolution (transfer of authority to an autonomous unit which can act independently without permission from the center).

Understanding these differences, Hanson (1997) suggested, is essential, since each form determines the amount, type, and permanency of authority to be transferred. It is important to note that there is neither a genuinely decentralized educational system nor a fully centralized educational system: all educational decisions retain some degree of centralization and decentralization (Hanson 1998). Therefore, a centralized vs. decentralized view no longer provides an accurate framework to understand educational reform. Instead, we should view decentralization on a continuum ranging from deconcentration to devolution. Yazdi (2013) similarly posited that centralization or decentralization cannot be considered an absolute, since “in most countries, a balance between both is required to make an effective educational system” (p. 98). The advantages of a decentralized system tend to be the disadvantages of a centralized system.

Benefits of decentralization in education

There is ample “Western” academic research that renders decentralization a silver bullet that guarantees solutions for many educational, political, and economic problems worldwide. The overall rationale for decentralization is to promote a form of democratic governance and participatory approaches to education. One fundamental feature of decentralization is accountability. It is argued that accountability is vital to decentralization because accountability requires responsibility. The logic is that local institutions are better equipped to determine and respond to local needs and are more easily accountable to local communities, so they can provide a more equitable allocation of resources (Bernbaum 2011; Ribot 2001; Winkler 1993; Winkler 1993). Smyth (2011) argued that decentralization makes “schools more responsive and accountable to parents while removing schools from what was argued to be inefficient centralised control” (p. 97). Holding lower-level actors—principals, teachers, and parents—downwardly accountable for outcomes is essential for successful decentralization (Ekpo 2007; Shah and Thompson 2004).

As for enhancing efficiency and effectiveness, Crook and Manor (1998) argued that moving people closer to government increases efficiency by helping to “tap the creativity and resources of local communities by giving them the chance to participate in development” (p. 1). Dobrolyubova (2013) contended that when power is delegated in a decentralized structure, new functions develop to control the effectiveness of the delegated authorities’ performance. Concerning education, the argument supporting decentralization centers on providing opportunities for stakeholders to participate in education, by moving decisions about education closer to those responsible for delivering education (McGinn and Welsh 1999). It is assumed that the local stakeholders have a greater knowledge of local needs and preferences much better than a centralized government, since locals are better informed to meet the heterogeneous demands (Channa 2015).

There are challenges when education systems are decentralized (Chann 2016). Hanson (1997) noted that developing a decentralized system of education takes significant time and cannot be accomplished simply by passing a policy. Instead, a decentralized system must be built, which requires overcoming challenges at the center and the periphery. Notable challenges when implementing a decentralized system include the need to change long-established behaviors and attitudes (Hanson 1997), the lack of human capacity (Devas 2005; Smoke 1999), and the need to develop new skills in individuals at all levels (Hanson 1997). Finally, Hanson (1997) pointed out, the “educational officials who managed the centralized system tend to be less than enthusiastic about decentralization and slow down the change process”. In fact, Bray (2003) suggested that although deconcentration is a form of decentralization, “it can be a mechanism for tightening central control of the periphery instead of allowing for greater local decision-making” (p. 207).

Background and context

In the following sections, we further explore this debate by examining the case of decentralized educational reform over the past decade in Qatar. Specifically, we first outline Qatar’s decentralized educational reform Education for a New Era, which was designed by the RAND Corporation. Next, we show how the pillars of the reform, particularly autonomy, impact the role of teachers. Finally, we provide an analysis of the current situation through an example of a recent educational change initiative.

The theoretical benefits of decentralization are appealing to countries that desire social and economic development via advanced educational systems. Qatar was achieving economic prosperity, substantial social progress, and a growing desire to participate more prominently in global activities. However, Qatar’s educators became concerned with the poor performance of its students on standardized tests like PISA/TIMSS and the low education quality provided by Qatar’s schools. Qatari students demonstrated underachievement, a lack of marketable skills, and a loss of interest in higher education, so “they [were] failing to contribute to Qatar’s economic and social prosperity and [were] becoming more susceptible to extremist influences” (Erman 2007, p. 11).

In 2003, Qatari officials responded to these issues by contracting RAND Corporation, a non-profit research organization, to critically examine and assess the Qatari education system from kindergarten to grade 12, and to provide recommendations to improve the system to address the nation’s rapidly changing needs. In Nasser’s (2017) words, RAND’s analysis “identified the strengths and weaknesses of the existing system and pointed to two main reform priorities: improving the education system’s essential elements through standards-based system and devising a system-changing plan to address the system’s overall inadequacies” (p. 3). Furthermore, RAND noted that schools lacked a vision and mission. There was also an absence of school leadership, schools relied on top-down decisions, and concerns existed about curriculum and instruction (Nasser 2017).

Qatar ventured into a decentralized educational reform, providing a new government-funded school structure, Education for a New Era, that was refined and customized to suit the local context (Brewer et al. 2007). Qatari authorities adopted a “charter school” model that was heavily reliant on a decentralized system, embracing four pillars that demand a decentralized system: autonomy (shifting from a centralized to a decentralized system allocating decision-making to educators so they may better meet students’ needs), variety (providing diverse schooling options to fit specific needs), choice (providing parents with the chance to choose schools that best meet the needs of their children, based on publicly available data on school environment and performance), and accountability (the new independent schools would be held accountable to the government via a contractual agreement and regular monitoring through standardized student assessments).

Based on the reform’s principle of autonomy, teachers experienced a substantial shift in their role toward more non-traditional classroom practices (Zellman et al. 2009). Providing teachers autonomy enabled them to control the content of their lesson plans, including curriculum development, the selection of learning resources, and flexibility and variety in their instructional approaches (Nasser 2017). For many teachers, this new role and process created confused responsibilities and roles, as many teachers did not have the expertise and skills needed to adapt to the shift (Nasser 2017; Zellman et al. 2009). Furthermore, there was a lack of guidance and development for teachers (Zellman et al. 2009).

Recognizing the need to improve the quality of teacher professional development, another weakness identified by RAND, the Ministry of Education and Higher Education (MoEHE) provided numerous professional development programs. (In November 2002, Qatar established the Supreme Education Council (SEC) to oversee and direct Qatar’s education system. In 2014 by an Amiri Decree, the SEC was renamed to the Ministry of Education and Higher Education.) Nasser (2017) provided a historical account of how Qatar’s education reform addressed teacher development. In the early years of the reform, these programs included contracting educational companies, also known as School Support Organizations (SSOs), to work with schools and teachers to provide professional support and development, focused on improving teaching methods and implementing student-centered teaching methods. The SSOs also worked with teachers on planning and curriculum development and attempted to build the capacity used in a train-the-trainers model.

The MoEHE developed a framework for professional development in 2012-2013 and its Education Institute offered a variety of teacher training programs throughout the reform. Professional standards for teachers were implemented in 2007 and revised in 2014. In 2012, the College of Education at Qatar University developed the National Center for Educator Development, which still provides numerous professional development programs for teachers and educational leaders. Additionally, the MoEHE implemented a certification and licensing program for teachers. Meanwhile, the College of Education moved from offering a bachelor’s degree in general education to degrees in education that specialized in areas such as mathematics, English, and science. The college also launched postgraduate teacher training programs.

In summary, Education for a New Era has spawned numerous forms of teacher development in Qatar’s public schools. Over a decade, diverse teacher development has been implemented so that teachers can keep current on the latest teaching techniques. This support for teachers through a variety of programs should have developed both capacity and teachers who can implement a variety of pedagogical approaches with little development.

An example of a recent change initiative: Implementing project-based learning in Qatari governmental schools

Qatar has spent over a decade working to provide high-quality and effective teacher development that will improve classroom teaching and practice, ultimately improving student learning. This has led to a wide array of programs and teaching approaches left for teachers to implement. We argue that by now, since schools have faced a barrage of new top-down educational policies and practices trying to improve education, Qatari teachers should be able to perform and implement a program like PBL. In what follows, we argue that Qatar has now embraced a deconcentration educational structure, where teachers implement a prescribed set of procedures that extend into the classroom. For example, we see borrowed education policies and strategies that require a decentralized system to flourish, but they are adopted and forced into a centralized school system. In this study, we use an example of pedagogical innovation, focusing on implementing PBL in Qatari governmental schools. As is discussed below, PBL is still considered a new phenomenon in Qatar’s government schools (Said 2016).

Following the Qatar National Vision 2030 (General Secretariat for Development Planning 2008), a list of strategies was developed at a state level. All educational institutions were asked to promote creativity and innovation in teaching and learning, in order to help students develop 21st-century skills (Said 2016). Over the next decade, a list of transferred policies and strategies for educational innovation was implemented under the supervision of various sectors of the government. The aims of implementing these educational reforms were (1) to provide schools with the chance to develop innovative approaches to curriculum and pedagogy, and (2) to develop learners with critical thinking and creativity.

The most recent policy issued by the MoEHE requested the implementation of PBL into the curriculum of four subject areas: Arabic, English as a Foreign Language, Math, and Science. Qatari government schools announced the initiation of PBL in May 2017; all governmental schools received a white paper from MoEHE on the topic, two weeks before the school summer break. The MoEHE provided a two-day workshop for PBL training by subject, facilitated by two invited speakers from outside Qatar. One or two teachers selected from each government school attended the required workshop. Upon completion, the train-the-trainer model was used with the remaining teachers in their school. The actual implementation began in the middle of September 2017.

According to the initial plan for the PBL implementation communicated during the workshops, each teacher was expected to implement six PBL sessions during the fall semester 2017-18, later reduced to two sessions. Each teacher also had to design a project for his or her students to conduct during these two PBL sessions. The project design was supposed to follow a form distributed by the MoEHE, which listed a six-step procedure and included lesson plan templates, providing little autonomy for teachers. Teachers could only choose project topics based on a few options from the existing textbooks. Additionally, the teachers were to fill out a set of forms requested by the MoEHE, including detailed plans of implementing the project and how the project will match the national curriculum standard by subject. The MoEHE also provided peer assessment forms and reflection forms for students. Each school could decide the duration of each PBL session, but could only use two contact hours or two class periods for conducting PBL. The rest of the contact hours during the semester were to be taught using the conventional method. Each school was provided with a certain number of materials by MoEHE that could be used to design projects, such as fabric, plastic food materials, and posters.

Discussion

What is the current situation regarding decentralization in Qatar’s education system? According to the existing theories, the education system has moved away from the intent of the reform, which was a delegation form of decentralization to a more deconcentration form. Although there can be many reasons for this transition, here we address several prominent issues. Following Bray’s (2003) model of forms of decentralization, the educational reform initiated in 2003 could be seen as decentralization aiming to reach a delegation or even devolution level, at least based on government ideals. Nevertheless, its implementation was challenged by several factors which constrained its progression including stakeholders’ criticisms based on the substantial reliance on policy borrowing, lack of concern of Qatari culture and identity, anxiety over language policy among others.

Notably, public dissatisfaction, coupled with little evidence of progress in the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), was a factor in the gradual re-centralization of government control (Abou-El-Kheir 2017; Nolan 2012). Nolan (2012) wrote, “while the initial restructuring of the K-12 system was intended to grant greater autonomy to schools, the extent of the challenge and the lack of clear guidelines undermined community confidence in the reform efforts” (p. 26). According to Hanson (1998), for a decentralized system to evolve and become effective, all stakeholders must agree, be willing to collaborate, and have a shared vision. In the case of Qatar, teachers, principals, and parents were not engaged or directly involved in the reform, causing a backlash against the political will that promoted the reform. In this way, one could argue that the reform has not achieved or sustained the four pillars in the charter school model of decentralization. The example of a state-wide change initiative for pedagogical innovation towards PBL serves as a platform to discuss the specific concerns of implementing a decentralized system, particularly with how borrowed teaching strategies requiring autonomy are implemented within a centralized education system.

First, decentralization often encounters several cultural restraints indicating that the process might not fit well into all countries, which is one reason that some countries reject decentralization and re-centralize public education (Yazdi 2013). In the case of Qatar, the concept of autonomy that was a pillar of the transferred reform that generated resistance (Alfadala 2015). Implementing a pedagogical innovation focusing on student-centered learning, such as PBL, demands serious change at several institutional levels: support from leadership, infrastructure facilities, curriculum transformation, assessment adjustment, and most importantly, the engagement of teachers who are the main actors in implementation (Fullan 2007; Moesby 2004). Specifically, PBL requires autonomy at the administrative and classroom level (Savin-Baden 2003), demanding an immense change in teachers’ roles from knowledge-transmitters and instructors of behavior to facilitators of independent, self-regulated, and self-directed learning (Savin-Baden 2003). However, the practice of implementation in Qatar reflects a deconcentrational approach, where schools and teachers are required to carry out the tasks and are responsible for implementing a list of pre-determined rules that, in practice, contradict the philosophy of PBL learning and teaching.

This example also reflects a dilemma between good intentions and practical difficulty. On the one hand, the MoEHE intended to use this program as a strategy for developing independent, creative, and collaborative learners with critical thinking abilities, an aspect of the original reform. In order to promote autonomous learners, however, teachers must be individually autonomous learners themselves, with the professional skills to use strategies and techniques that promote learning autonomy (Nakata 2011). This requires that teachers have space where autonomy can flourish. School and societal environments play an influential role in teacher autonomy in terms of their readiness to facilitate learner autonomy (Fullan 2014). But in this PBL implementation, the teachers were not involved in any decision-making process and they played only a passive role in the implementation. Therefore, they only saw the change initiative as a classroom strategy requiring them to follow the recipe book, instead of seeing the its potential educational benefits (Du, Chaaban, and AlMabrd, 2019). From the MoEHE’s perspective, this top-down process may increase the efficiency of implementation; nevertheless, the lack of understanding, motivation, and skills by the implementers, in this case teachers, became obstacles to realizing the governmental wishes and made the reform less effective than expected (Adelman and Taylor 2007; Al Said et al. 2019). It also made the process a form of deconcentration instead of the desired delegation.

In the same vein, Yazdi (2013) drew attention to the ways in which decentralization often encounters cultural restraints, indicating that the process might not fit well into all countries. After such a failure of decentralization, some countries return to a re-centralization of education. Several Qatari cultural factors may have formed constraints to these reforms. First, it can be argued that if a decentralized reform is centralized or top-down in its implementation, it is likely to face resistance and failure. This is one possible reason for the recentralization of Qatar’s public education. Akkary (2014) stated, “these mandates impose that the practitioners adopt these changes with total disregard to their perspectives on the feasibility and responsiveness of these changes to the needs of schools and students” (p. 183). In other words, the intended decentralization through Qatar’s educational reform, in its current form, reflected the concept of deconcentration (Bray 2003) from its inception, which undermined the principles of autonomy and variety.

Second, understandings and implementation of decentralization is often culturally bounded. Akkary (2014) raised a significant issue regarding Qatar’s educational reform and the view of decentralization in the Arab world. She wrote, “the prevalence of the top-down approach to reform has resulted in deeply ingrained norms that revolve around the responsibility of initiating reform. In Arab countries, initiating reform is viewed as the sole responsibility of national governments” (p. 183). The view that the government is responsible for the change conflicts with the fundamental bottom-up philosophy of decentralization.

Furthermore, regarding teachers and cultural issues in the Arab world, Bashshur (2005) suggested that teachers think that policymakers are responsible for such reforms, making teachers the passive recipients rather than the initiators of change. As a result, teachers lack any sense of being agents of change in their schools. For reform to take root in GCC countries, scholars, policymakers, and school practitioners must work together to culturally ground Western practices and develop reform proposals that are embedded in the cultural contexts of their schools (Akkary 2014).

To sum up, the case of Qatar makes it clear that even where there is significant political will, without engaging broad sections of society in education reform, the efficacy of that reform will be limited. To achieve the objectives and receive the benefits of decentralization, the education system must be embedded in an inclusive environment, where governmental understanding can be best shared and communicated with those who are responsible for the implementors of any change initiative (McGinn and Welsh 1999). Although scholars doubt whether decentralization can be realized at all for developing countries where democracy is not practiced (Bardhan and Mookherjee 2005), the current study argues that a governmental wish for decentralization in a developing country like Qatar is neither black and white nor a one-directional movement. There is always a paradox when borrowing “Western” concepts for a different context (Romanowski et al. 2018). Digesting and developing a borrowed idea are less consistent and more complex than one expects, as Gershberg and Winkler (2004) pointed out: “what is equitable may not be efficient, what is efficient may not be democratic, and what is democratic may not be equitable” (p. 324). Educational policymakers and those who implement reform policies and practices must develop an understanding of the role of culture and context in borrowed educational reforms: rather than making the culture fit into the system, the system should fit the culture.

References

Abi-Mershed, O. (2010). The politics of Arab educational reform. In O. Abi-Mershed (Ed.), Trajectories of education in the Arab world: Legacies and challenges (pp. 1–12). New York, NY: Routledge.

Abou-El-Kheir, A. (2017). Qatar’s K-12 education reform—A review of the policy decisions and a look to the future. OSF Preprints. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/9U8CA.

Adelman, H. S., & Taylor, L. (2007). Systemic change for school improvement. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 17(1), 55–77.

Akkary, R. (2014). Facing the challenges of educational reform in the Arab world. Journal of Educational Change, 15(2), 179–202.

Al Said, R. S., Du, X., Al Khatib, H. A. H., Romanowski, M. H., & Barham, A. I. I. (2019). Math teachers’ beliefs, practices, and belief change in implementing problem based learning in Qatari primary governmental school. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 15(5), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejmste/105849.

Alfadala, A. (2015). K-12 Reform in the Gulf Corporation Council (GCC) countries: Challenges and policy recommendations. The World Innovation Summit for Education (WISE), 1–56. https://www.wise-qatar.org/2015-wise-research-K12-reform-GCC-countries/

Avalos, B., & Assael, J. (2006). Moving from resistance to agreement: The case of the Chilean teacher performance evaluation. International Journal of Educational Research, 45(4/5), 254–266.

Aydarova, O. (2013). If not “the best of the West”, then “look East”: Imported teacher education curricula in the Arabian Gulf. Journal of Studies in International Education, 17(3), 284–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315312453742.

Aydarova, E. (2017). Discursive contestations and pluriversal futures: A decolonial analysis of educational policies in the United Arab Emirates. Education Policy Analysis Archives. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.25.3063.

Bardhan, P., & Mookherjee, D. (2005). Decentralization, corruption and government accountability: An overview. In S. Rose-Ackerman (Ed.), International Handbook Of The Economics Of Corruption (pp. 161–188). Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Co.

Bashshur, M. (2005). Dualities and entries in educational reform issues. In A. El Amine (Ed.), Reform of general education in the Arab world (pp. 277–298). Beirut: UNESCO.

Bennett, C. J. (1997). Understanding ripple effects: The cross-national adoption of policy instruments for bureaucratic accountability. Governance, 10(3), 213–233.

Bernbaum, M. (2011). Decentralization: EQUIP2 lessons learned in education. Washington, DC: United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

Bray, M. (2003). Control of education: Issues and tensions in centralization and decentralization. In R. F. Arnove & C. A. Torres (Eds.), Comparative education: The dialectic of the global and the local (2nd ed., pp. 204–228). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Brewer, D. J., Augustine, C. H., Zellman, G. L., Ryan, G. W., Goldman, C. A., Stasz, C., et al. (2007). Education for a new era: Design and implementation of K-12 education reform in Qatar. Santa Monica, CA: RAND-Qatar Policy Institute.

Burbules, N., & Torres, C. (2000). Globalization and education: An introduction. In N. Burbules & C. Torres (Eds.), Globalization and education: Critical perspectives (pp. 1–26). New York, NY: Routledge.

Chann, A. (2016). Popularity of the decentralization reform and its effects on the quality of education. Prospects Comparative Journal of Curriculum, Learning, and Assessment, 46(1), 131–147.

Channa, A. (2015). Decentralization and the quality of education. Background paper prepared for education for all global monitoring report 2015. Paris: UNESCO.

Crook, R. C., & Manor, J. (1998). Democracy and decentralization in South-East Asia and West Africa: Participation, accountability and performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dale, R. (2000). Globalization and education: Demonstrating a “common world educational culture” or locating a “globally structured educational agenda”? Educational Theory, 50(4), 419–427.

Dan, V. (2018). Empirical and non-empirical methods. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Devas, N. (2005). The challenges of decentralization. Brasilia: Global Forum on Fighting Corruption.

Dimmock, C., & Walker, A. (2000). Developing comparative and international and management: A cross-cultural model. School Leadership and Management, 20(2), 143–160.

Dobrolyubova, E. (2013). How decentralization affects efficiency and effectiveness of public expenditures: Review of execution of delegated powers. Public Administration Issues, 4, 99–112.

Dou, D., Devos, G., & Valcke, M. (2017). The relationships between school autonomy gap, principal leadership, teachers’ job satisfaction and organizational commitment. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 45(6), 959–977. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143216653975.

Du, X., Chaaban, Y., & AlMabrd, Y. M. (2019). Exploring the concepts of fidelity and adaptation in the implementation of project-based learning in the elementary classroom: Case studies from Qatar. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 18(9), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.26803/ijlter.18.9.1.

Edwards, D. B., Jr., & De Matthews, D. (2014). Historical trends in educational decentralization in the United States and developing countries: A periodization and comparison in the post-WWII context. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 22(40), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v22n40.2014.

Ekpo, A. H. (2007). Decentralization and service delivery: A framework. Nairobi: African Economics Research Consortium.

Ellili-Cherif, M., Romanowski, M. H., & Nasser, R. (2012). All that glitters is not gold: Challenges of teacher and school leader licensing system in a GCC country. International Journal of Educational Development, 32(3), 471–481.

Erman, A. (2007). Think independent: Qatar’s education reforms. Harvard International Review, 28(4), 11–12.

Fiske, E. B. (1996). Decentralization of education. Politics and consensus. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Florestal, K., & Cooper, R. (1997). Decentralisation of education: Legal issues. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Fullan, M. (2007). The new meaning of educational change. New York, NY: Routledge.

Fullan, M. (2014). Teacher development and educational change. New York, NY: Routledge.

General Secretariat for Development Planning (2008). Qatar National Vision 2030. Doha: General Secretariat for Development Planning. https://www.mdps.gov.qa/en/qnv/Documents/QNV2030_English_v2.pdf.

Gershberg, A., & Winkler, D. R. (2004). Education decentralization in Africa: a review of recent policy and practice. In B. Levy & S. Kpundesh (Eds.), Building State Capacity in Africa: New Approaches, Emerging Lessons. Washington, DC: World Bank Institute.

Gershberg, A. I. (2005). Towards an education decentralization strategy for Turkey: Guideposts from international experience: Policy note for the Turkey education sector study. Washington, DC: World Bank Institute. http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTTURKEY/Resources/361616-1142415001082/Turkey_decentralization_strategy.pdf.

Gonzalez, G., Karoly, L. A., Constant, L., Salem, H., & Goldman, C. A. (2008). Facing human capital challenges of the 21st century: Education and labor market initiatives in Lebanon, Oman, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates, MG-786. Santa Monica, CA: RAND.

Govina, R. (1997). Decentralization of educational management: Experience from south Asia. Paris: UNESCO International Institute for Educational Planning (IIEP).

Hallinger, P., & Bryant, D. A. (2013). Synthesis of findings from 15 years of educational reform in Thailand: Lessons on leading educational change in East Asia. International Journal of Leadership in Education: Theory and Practice, 16(4), 399–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2013.770076.

Hanson, E. M. (1997). Educational decentralization: Issues and challenges. Occasional paper 9. Chile Partnership for Educational Revitalization in the Americas.

Hanson, M. E. (1998). Strategies of educational decentralization: Key questions and core issues. Journal of Educational Administration, 36(2), 111–128.

Haug, B. (2009). Educational decentralization and student achievement. A comparative study utilizing data from PISA to investigate a potential relationship between school autonomy and student performance in Australia, Canada, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Oslo: Faculty of Education, University of Oslo.

Khodr, H. (2011). The dynamics of international education in Qatar: Exploring the policy drivers behind the development of Education City. Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies, 2(6), 514–525.

Kirk, D. J. (2013). Comparative education and the Arabian Gulf. In A. Wiseman & E. Anderson (Eds.), Annual review of comparative and international education (pp. 175–189). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing.

Lee, M. N. N. (2006). Centralized decentralization in Malaysian education. In C. Bjork (Ed.), Educational decentralization: Asian experiences and conceptual contributions (pp. 149–158). Dordrecht: Springer.

McDonald, L. (2012). Educational transfer to developing countries: Policy and skill facilitation. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 69, 1817–1826.

McGinn, N., & Welsh, T. (1999). Decentralization of education: Why, when, what and how?. Paris: UNESCO.

Moesby, E. (2004). Reflections on making a change towards project-oriented and problem-based learning (POPBL). World Transactions on Engineering and Technology Education, 3, 269–278.

Naidoo, J. (2005). Managing the improvement of education. In A. M. Verspoor (Ed.), The challenge of learning: Improving the quality of basic education in sub-Saharan Africa (pp. 239–270). Paris: ADEA.

Nakata, Y. (2011). Teachers’ readiness for promoting learner autonomy: A study of Japanese EFL high school teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(5), 900–910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.03.001.

Nasser, R. (2017). Qatar’s educational reform past and future: Challenges in teacher development. Open Review of Educational Research, 4(1), 1–19.

Nolan, L. (2012). Liberalizing monarchies: How Gulf monarchies manage education reform. Doha: Brookings Doha Center.

Phillips, D., & Ochs, K. (2003). Processes of policy borrowing in education: Some explanatory and analytical devices. Comparative Education, 39(4), 451–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305006032000162020.

Ribot, J. (2001). Local actors, powers and accountability in African decentralizations: A review of issues. Paper prepared for International Development Research Centre of Canada Assessment of Social Policy Reforms Initiative, United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD).

Rizvi, F., & Lingard, B. (2010). Globalizing educational policy. London: Routledge.

Romanowski, M. H., Alkhateeb, H., & Nasser, R. (2018). Policy borrowing in the Gulf Cooperation Council Countries: Cultural scripts and epistemological conflicts. International Journal of Educational Development, 60, 19–24.

Said, Z. (2016). Science education reform in Qatar: Progress and challenges. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science & Technology Education, 12(8), 2253–2265.

Sakr, A. (2008). GCC states competing in educational reform. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/20501.

Savin-Baden, M. (2003). Facilitating problem-based learning: Illuminating perspectives. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Shah, A., & Thompson, T. (2004). Implementing decentralized local governance: A treacherous road with potholes, detours, and road closures. World Bank policy research working paper 3353. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Smoke, P. (1999). Understanding decentralization in Asia: An overview of key issues and challenges. Regional Development Dialogue, 20(2), 1–17.

Smyth, J. (2011). The disaster of the ‘self-managing school’ – genesis, trajectory, undisclosed agenda, and effects. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 43(2), 95–117.

Steiner-Khamsi, G. (2004). Lessons from elsewhere: The politics of educational borrowing and lending. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Tan, C. (2012). The culture of education policy making: Curriculum reform in Shanghai. Critical Studies in Education, 53(2), 153–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2012.672333.

Tan, E. (2014). Human capital theory: A holistic criticism. Review of Educational Research, 84(3), 411–445. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654314532696.

Tatto, M., Schmelkes, S., Guevara, M., & Tapia, M. (2006). Implementing reform amidst resistance: The regulation of teacher education and work in Mexico. International Journal of Educational Research, 45(4/5), 267–278.

Winkler, D. R. (1993). Fiscal decentralization and accountability in education: Experiences in four countries. In J. C. Hannaway & M. Carnoy (Eds.), Decentralization and school. Improvement can we fulfil the promise? (pp. 102–134). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

World Bank Group (2001). Decentralization and subnational regional economics. http://www1.worldbank.org/publicsector/decentralization/service.htm.

Yazdi, S. V. (2013). Review of centralization and decentralization approaches to curriculum development in Iran. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 3(4), 97–115.

Zellman, G. L., Ryan, G. W., Karam, R., Constant, L., Salem, H., Gonzalez, G., Orr, N., Al-Thani, H., & Al-Obaidli, K. (2009). Implementation of the K-12 education reform in Qatar’s schools. RAND-Qatar Policy Institute. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/monographs/2009/RAND_MG880.pdf.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Romanowski, M.H., Du, X. Education transferring and decentralized reforms: The case of Qatar. Prospects 52, 285–298 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-020-09478-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-020-09478-x