Abstract

Industrial policy, particularly through the provision of large-scale assistance to industry in the form of ‘tax holidays’ and subsidies to firms, is very important in China. A major contribution of this paper is to introduce firm-level measures of assistance directly into industry-level production functions determining firm output using Chinese firm-level panel data for 1998–2007 and analysing the impact of government assistance on TFP at the firm-level. Our results indicate inverted U-shaped gains from assistance: across the 26 industries considered, firms receiving assistance rates of 1–10, 10–19, 20–49 and 50+% experienced on average 4.5, 9.4, 9.2 and −3% gains in TFP level, respectively. We then decompose the growth of TFP and relate it to assistance and formal political connections between firms and the government. We find in general firms receiving assistance contributed relatively more to TFP growth than non-assisted firms. However, this was largely through new firms being ‘encouraged’ to start-up rather than through firms open throughout 1998 to 2007 improving. There is also evidence that closure rates were truncated as a result of assistance. Moreover, the better results for assisted firms was very much ‘driven’ by a sub-group that received assistance but had no formal political connections and were not State-owned.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Providing assistance to industry as part of an industrial strategy has a long history, in both developing and developed economies (Schwartz and Clements 1999). Until more recently, such approaches were presumed to have been largely a failure, summed-up by Cohen (2006, p. 88) as follows:

“The standard criticism levelled against sectoral industrial policies is that the state has neither the necessary information nor adequate incentives to make better choices than the market… it tends to misestimate … the negative long-term effects of the protection granted to certain firms and the negative impacts of the benefits granted to promoted sectors on other sectors.”

However, industrial policy is generally now regarded more favourably as shown by various contributions to recent books on the topic (e.g., Felipe 2015; Stiglitz and Lin 2013). Rather than just ‘believe’ in the market and allow economic success to be generated by globalisation allied to government intervention in support of liberalisation, privatisation and deregulation, “… it has become obvious that all governments are engaged in various forms of industrial policies… (therefore) the question is not whether any government should use industrial policy but rather how to use industrial policy in the best way” (Stiglitz et al. 2013, pp. 5–6).

China is perceived as a country that provides large-scale assistance to industry (Haley and Haley 2013). But was government assistance targeted at the right firms and sectors and at an appropriate level? A recent paper by Aghion et. al. (2015) investigated if the distribution of government assistance to firms in China enhanced productivity, finding that assistance was allocated to competitive sectors and /or fostered competition in a sectorFootnote 1 so enhancing productivity growth over the 1998–2007 period. Their approach was essentially to test if subsidies were correlated with initial competition levels, where the latter was measured using a Lerner index. They also measured the concentration of assistance across firms within each sector (using a Herfindahl index). Both the correlations obtained at the sector-city level (the Lerner indices) and the Herfindahl indices were regressed on firm-level total factor productivity (TFP) estimates obtained using an Olley–Pakes approach. Both measures were found to have positive and significant impacts on TFP, and this is taken as evidence that government assistance was targeted at the right firms and sectors.

However, Aghion et al. (op. cit.) did not test directly whether receiving assistance had a direct impact on each firms’ TFP nor the extent of such assistance; if receiving assistance is found to lower firm-level TFP (at least for some categories of firms or at, say, high levels of assistance) then it may well be that overall industrial policy in China introduces distortions that increase misallocation and work against the productivity-enhancing effects associated with the (more macro-level) distribution of assistance. Whether assistance acts as a boost to investment and production, and the extent to which this improves/reduces efficiency and thus productivity growth, is largely an empirical issue. Thus a major contribution of this paper is to fill this gap in the literature, by introducing variables that measure the assistance (including tax ‘holidays’ and subsidies) received by each firm directly into production functions determining firm output and analysing the impact of the assistance on TFP at the firm-level. A system-GMM econometric approach is used to measure firm-level TFP (with the variables representing assistance instrumented by their lagged values). To check the robustness of our results, the impact of assistance is also tested using a production function approach based on ‘matching’ firms receiving assistance with those not receiving ‘treatment’ who nonetheless had very similar characteristics to the assisted sub-group (Imbens and Rubin 2015). Both sets of results indicate that across the 26 industries considered Chinese firms that received assistance had higher TFP during 1998–2007, although there is some evidence that too high a level of assistance has negative consequences for TFP, suggesting that ‘rent-seeking’ and/or the pursuit of profit is blunted when firms become too dependent on government help, especially when such help is tied to ‘political control’ by the state (which is the case in China as explained below). To justify such results, we provide a simple model in the appendix that sets out how this is consistent with economic theory.

Apart from the Aghion et al. (2015) study, we are only aware of a study by Girma et al. (2009) who used the same database as we use (but only for 1999 to 2005) to consider whether subsidies boosted export sales for domestic firms in manufacturing (finding subsidies stimulated exporting intensities of existing exporters but had little impact on encouraging firms to enter exporting). The major differences with the current study are: we include all (and not just domestic) firms in manufacturing and utilities covering 1998–2007; the more important form of assistance provided through ‘tax holidays’ (as well as subsidies) is included; and our dependent variable is TFP. Other studies, mostly covering developed economies, that consider the impact of assistance on productivity are relatively scarce, usually relate only to labour productivity (not TFP) and have produced mixed results. For example, Irwin and Klenow (1996) found no impact on labour productivity of R&D subsidies for U.S. high-tech companies; for Japanese forestry, Managi (2010) found a negative relationship between subsidies and TFP; Einio (2014) reports no instantaneous impacts of R&D support programmes in Finland on productivity (although there is evidence of long-term gains); Huang (2015) shows that tax credit use among Taiwanese firms enhanced their productivity; while Koski and Pajarinen (2015) report that R&D subsidies had no statistically significant impact on labour productivity in Finnish firms during 2003–2010, although employment subsidies and other subsidies (the latter covering similar State aid instruments as included in the present study) were negatively related to output-per-worker.Footnote 2

The paper is set out as follows. In the next section we discuss the rationale for the (Chinese) government providing assistance to firms, where government aid can be central, state or local (or some combination of all three levels). In Section 3 we discuss briefly the form that assistance takes and present some background information on its importance to firms. Following this, we estimate industry-level production functions using system-GMM and a ‘matching’ approach, to test whether assistance impacted on the level of TFP across firms. In Section 5 we decompose the growth of TFP and relate it to assistance and the extent of formal political connections between firms and the government. The paper concludes with a summary and some ideas for further research that would extend the approach taken in this paper.

2 The rationale for government assistance to firms

The starting (traditional neoclassical) position is usually that markets are efficient such that they are the best mechanism by which to allocate resources (cf. the model of general equilibrium associated with Arrow and Debreu 1954); the exception is when there are market failures (European Commission 2002). Traditionally such failures have been associated with imperfect and asymmetric information being available to (especially smaller) firms, and/or imperfect (risk) markets leading to higher (financial) costs for by such firms and more generally a problem of incomplete markets (Greenwald and Stiglitz 1986). Failures are also associated with not being able to capture positive externalities in other firms—such as R&D spillovers—or the wider benefits gained from geographic agglomeration (e.g., intra-industry specialization through Marshall-Arrow-Romer economies and/or inter-industry Jacobian urbanization economies—see Marshall 1890, Arrow 1962, and Romer 1986 and Jacobs 1970, 1986). Such justification for government intervention on the grounds of market failure has been criticized by those who do not adhere to the neoclassical tradition; for example, evolutionary economists (e.g., Metcalfe and Georghiou 1998) have argued that information costs, leading to asymmetric outcomes, are one of the features of the market, and they are in part necessary as a selection device (for promoting the fittest firms) and in providing incentives for learning and discovery, which is crucial to the process of variety creation upon which the evolutionary view of markets is based (as Metcalfe and Georgiou, op. cit., point out “a profit opportunity known to everybody is a profit opportunity for nobody”). This does not mean that there is no rationale for government intervention, assuming that it sees a direct increase in economic benefits from more firms gaining information and thus acting on that information (e.g., by adopting certain technologies, increasing their overall capabilities, etc.). For example, Casson (1999) argues that in this situation the government has a comparative advantage in information, and it is on this basis (not market failure) that it can justify intervention. See also Cohen (2006, section 3.1).

More recently, there has been an emphasis on dynamic factors that lead to a comparative advantage (Rodrik 2006), such as the importance of knowledge and firm capabilities as a source of firm performance and thus productivity growth.Footnote 3 Thus government intervention to enhance both learning and learning spillovers is especially warranted to coordinate structural transformations that will close the “knowledge” gap that exists with firms at the (international) frontier, so moving resources from low- to high-productivity sectors (it is argued—see Felipe 2015—that such sectors do not develop naturally in developing economies without government help). Thus, for example, Khan (2015) sets out a model of the ‘competitiveness curve’ that justifies assistance to industry (particularly in developing economies) based on providing ‘rents for learning’ to cover knowledge and capability gaps and encourage learning-by-doing. In developing economies like China, firms initially lack the sophisticated organisations and technical capabilities to produce goods and services at global quality standards (and costs), and assistance buys time to engage in the learning that is needed, as well as encouraging inward foreign direct investment from firms that have the required competencies (which should also lead to additional spillover effects).

In China, there is an additional rationale for government providing (large-scale) assistance to firms; in principle all firms in China can be subject to political control—i.e., there is a lishu relationship, which means firms are “subordinate to” political influence (the Chinese name for this relationship, as represented in the National Bureau of Statistics database we use below, is 隶属关). In practice the lishu relationship includes “… approvals for licences, domain, major projects, major operations decisions (such as profit distribution and investment) and firm structures” (Tan et al. 2007, p. 788), all of which are set to meet political objectives. As well as controls, the lishu relationship also involves government support and subsidies (e.g., access to finance, more favourable tax treatment, granting of contracts, access to raw materials and other ‘scarce resources’Footnote 4, etc.). The relationship is much stronger for publicly owned firms (e.g., state-owned enterprises, or SOEs, and collectively owned enterprises), who are also expected to meet certain ‘social’ goals set by politicians, such as employment targets, but it is still relevant to privately-owned and foreign-owned firms (either because of the strength of political connections and/or because of intervention by government). An essential difference in the lishu relationship between publicly-controlled and privately-owned firms tends to be that the former are more beset with meeting policy goals (e.g., employment) rather than receiving favourable treatment such as subsidies and/or access to finance (Wu et al. 2012).

However, Xia et al. (2009) state that over time the importance of lishu has diminished especially following reforms introduced in 1997, and the vast majority of newly established privately owned firms that have set up in China since the late 1990s have opted not to have any (formal) lishu relationship with the government (central, regional or local). Evidence for this is provided in (Ding et al. 2015, Table 1), who show that the proportion of medium- to large-sized Chinese firms in manufacturing and utilities with no political connections increased from 15.7% in 1998 to 76% by 2007. And yet the same data (which is also used in this study—see Table 1 above) shows that on average between 1998 and 2007 nearly 57% of firms receiving assistance had no formal political connections (nearly 52% of all firms, which includes those with no assistance, had no political connections). This provides strong support for the claim made by Haley and Haley (2013, Chapter 1) that under the operation of Chinese State Capitalism, the government is able to meet its industrial strategies not so much directly through traditional lishu relationships but rather through ensuring firms are dependent on government for financial assistance that creates mutual dependence. That is, Haley and Haely (op. cit, p. 21–22) note that “in China political factors matter at least as much as, and often more than, economic factors for firms’ and markets’ performance and therefore for the dispensation of subsidies”. They also argue—based on case studies—that there is substantial evidence that Chinese production subsidies have encouraged many overseas (and especially U.S.) firms to move manufacturing to China, after developing their technological competencies in their home countries.

Because of the decentralisation of power in China to the provinces, and the further layer of often strong local government with its own agenda, firms can have different (even several) links with central, provincial and local governments, each with hidden and often conflicting budgetary processes. Li and Zhou (2005) point out that local government officials have a major incentive to develop the economies in their jurisdictions because their political careers depend on the economic performance of their regions. Thus Walder (1992, pp. 528–29) comments that “China’s national budget is a nested hierarchy of independent budgets—each government unit exercises property rights over firms under their financial jurisdiction… each of which seeks to expand its revenues by capturing investment, subsidies, and grants”. Haley and Haley (op. cit. p. 21) review the case study evidence that shows “provincial governments deploy massive subsidies to support favoured business groups and further provincial rather than central objectives or efficiencies”.

Thus while Chinese policymakers in the period after the ‘open door’ reforms starting in 1992 sought to learn from how Korea and Japan achieved large-scale development, which included lessons in subsidising strategic industries, there is evidence (Heilmann and Shih 2013) that full-scale assistance to firms (and industrial policy more generally) only really got going in the 1990’s once Chinese policymakers had concluded that by supporting targeted firms they could advance the state’s interests in the new economic order (Thun 2004). Historically, such help had been limited to State-owned Enterprises (SOEs), but since the 1990’s this has been extended to privately-owned firms as well.

In terms of the type of assistance usually given to firms, this tends to be based on ‘horizontal’ (covering activities that take place in a broad range of sectors and typically affecting the ‘infrastructure’ surrounding firms) and ‘vertical’ (more targeted on specific firms and sectors) policies. The former has in more recent times received greater support as it is seen to have a smaller impact on competition (since it is not about ‘picking winners’ as all firms should face a ‘level playing field’), whereas vertical policies can favour one (sub-group) of firms to the detriment of others. That said, even horizontal policies impact more on certain firms (e.g., those more engaged in R&D, or located in sectors with attributes that are being encouraged by policy, such as higher value-added). In the Chinese context, Lin et. al. (2015) argue there has been a continuous upgrading towards more capital-intensive sectors with (latent) dynamic comparative advantage (rather than the static advantage of having a substantial, relatively cheap abundance of sufficiently skilled labour). In broad terms, industrial policy pursues the growth of ‘pillars’ (key industriesFootnote 5) where technology acquisition and improving competitive advantage feature strongly. Firms receive various financial incentives (including ‘tax holidays’, grants, and access to cheap loans), that are consistent with providing additional liquidity and sharing risk, and thus overall subsidizing production and investment; however, as Haley and Haley (2013, pp. 31–32) point out official information is very limited on how much assistance is provided, to whom and for what. Thus they conclude that “generally, despite stated policies, outsiders cannot ascertain the true policies that underlie subsidies”.

Thus whether assistance acts as a boost to investment and production, while at the same time underpinning productivity growth, is largely an empirical issue. Does it mitigate market failures, help infant industries, new firm entry and underdeveloped capital markets, coordinate (vertical and horizontal) linkages in production and enhance learning-by-doing; or, as Porter (1990) argues, do subsidies dull the market incentives firms’ face, delay adjustment and innovativeness, and overall constrain flexibility and instead create a culture of ‘rent seeking’ (particularly for SOEs and those firms with strong political connections with government—cf. Yu et al. 2010; Tan et al. 2007)?

Based on the discussion in this section, and in anticipation of the results presented below, we provide a simple theoretical model in the appendix where generally assistance lowers the ‘user’ cost of capital, so relaxing likely financial constraints and allowing firms to upgrade the quality of their capital stock, which in turn will lead to increases in TFP (e.g., through lowering costs as ‘vintage’ capital stock is replaced by more efficient, newer capital equipment; and/or through allowing firms to introduce new, higher quality products). The model also allows for managerial effort to be divided between pursuing higher levels of TFP and rent-seeking (e.g., through lishu relationships), where the latter (cet. par.) increases profitability (without increasing TFP) and thus boosts the personal reward to managers (e.g., when assistance ‘leaks’ into higher profits, through such ‘soft budget’ constraints, managers obtain greater bonus-related payFootnote 6 and this creates an agency problem—see, for example, Hanke and Heine 2015). The outcome is that we are able to show theoretically that up to a certain assistance rate (which we denote in the model as \(\widehat \gamma\)) managerial effort is dominated by efforts to improve TFP; however, when actual government assistance becomes too high (γ > \(\widehat {\mathrm{\gamma }}\)) this dulls the pursuit of higher TFP as ‘rent seeking’ dominates managerial efforts. Note, lack of data (e.g., on managerial effort) means we cannot directly estimate and therefore test the assumptions underlying the model in the appendix.

3 The extent of government assistance to Chinese firms

The data source used in this study covers medium- to large-sized firms belonging to 26 industries covering manufacturing and utilities for 1998–2007. A discussion of the unbalanced panel dataset used—the annual accounting reports required by government to be filed by industrial firms with the NBS over the period of 1998–2007—is presented in Ding et al. (2015). This dataset includes all SOEs and other types of enterprises with annual sales of five million yuan (about $817,000) or more. Brandt et al. (2012.) provide a thorough discussion of this extensively used dataset, which for present purposes covered nearly 600 thousand firms, which corresponds to some 2.2 million firm-year observations.

Table 1 presents information on the percentages that received assistance during this period, with firms sub-divided into those who only received tax holidays, subsidies, or both types of assistance. Information on subsidies received is reported by firms while tax holidays is calculated from taxes paid on profits and VAT combined with data on value-added and profits-before-tax for each firm. Firms that did not pay the full 17% rate of VAT or 33% profits tax are considered to have received a tax holiday.Footnote 7 Table 1 also reports the average tariff (ad valorem equivalent) on final imported goods as an additional source of assistance to firms, computed using the WITS (World Bank) database.Footnote 8

The percentage of firms receiving government assistance increased from over 53% in 1998 to over 72% in 2007 (Table 1). The largest form of assistance was tax holidays, while the percentage of firms receiving only subsidies was relatively small (and fairly constant); those receiving both tax holidays and subsidies rose from around 4% of firms in 1998 to over 8% by 2007. During this period, and reflecting China joining the WTO at the end of 2001, protection from overseas competition declined with the average tariff rate declining from some 18 to 10% (see Table 24.1 in Harrison et al. (2014), for details on tariff rates across industriesFootnote 9).

In terms of the financial value of assistance, Table 2 presents assistance rates (calculated using data on the total value of assistance divided by total value-added produced for each sub-group shownFootnote 10) broken-down into type of assistance and by ownership categories. Relief from paying VAT at its full rate was the most valuable source of help received (worth between 5.9 and 7.5% of value-added during the period), followed by profit tax ‘holidays’ (increasing from around 2% in 1998 to nearly 5% in 2007). Direct subsidies were worth significantly less (on average around 1% of value-added over 1998–2007). Cumulatively, assistance rose from around 10% of value-added in 1998 to 13% by 2007; foreign-owned firms (including those based in special economic areas and Taiwan) received the highest rates of assistance, rising slowly over time, while (perhaps unexpectedly) SOEs as a sub-group received the lowest rates of assistance.Footnote 11

4 The direct impact of assistance on firm level productivity

In this section we present the empirical findings on the relationship between the rate of government assistance received and TFP. The methodology (and justification for its use—such as the need to use a fixed-effects estimator; the strengths of the approach versus the Olley and Pakes (1996) and Levinsohn and Petrin (2003) approaches; the need to estimate a gross-output versus value-added production function; and the consistency of estimating TFP using a single-stage, rather than multi-stage, approach) has been fully set out in in Ding et al. (2015), where a system Generalised Methods of Moments (GMM) approach was used to estimate log-linear Cobb-Douglas gross-output production functions for 26 industries in China, using annual firm-level National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) data for 1998–2007. Specifically, we estimate the following model:

where endogenous y, e, m and k refer respectively to the logarithms of real gross output, employment, intermediate inputs, and the capital stock in firm i at time t (i = 1,…,N; t = 1,…T); and Xit is a vector of observed (proxy) variables determining TFP. In particular we include dummy variables measuring the rate of assistance received (compared to the benchmark sub-group who received no assistance); we do this because we find that the effect of assistance on TFP is non-linear and this is a standard way of accounting for non-linearity. Also included into the vector Xit are firm characteristics such as firm age, political affiliation, firm ownership, export behavior, whether the firm engaged in R&D, financial variables, and geographic location (Table 3 provides a list of the variables used; further discussion is provided in Ding et al., op. cit., relating to their Table 1). Lastly, t is a time trend, measuring exogenous gains in TFP over time.

Equation (1)—in dynamic form with additional lagged values of output and factor inputs—is estimated using the two-step XTABOND2 system GMM approach (Arellano and Bond 1991) implemented in STATA (this also involves correcting for any potential finite sample bias using Windmeijer’s 2005, approach). Thus Eq. (1) is estimated both in first-differences and in levels, allowing for fixed effects and tackling endogeneity of the right-hand-side variables (including the lagged dependent variable) and selection bias by using lagged values of the endogenous variables as instruments in the first differences equation, and first-differences of the same variables as instruments in the levels equation (Blundell and Bond 1998).Footnote 12 In this study, gross output, intermediate inputs, labour, and capital are treated as endogenous, as well as assistance rates, political affiliation, capital ownership,Footnote 13 exporting, and R&D. Lastly, according to Arellano and Bond (1991), the presence of second-order autocorrelation implies that the estimates are inconsistent. Panel tests for autocorrelation are used to establish whether second-order correlation is an issue.

The detailed results from estimating Eq. (1) for 26 two-digit industries/industry groups are presented in Table 7 (in the unpublished appendix). These are very similar to those presented in Ding et al. (2015), to which the interested reader is directed for a full discussion. Here we concentrate on the parameter estimates for the assistance variables (Table 4, top half). Firstly, as the diagnostics show, the models estimated pass various tests of the validity of the instruments used and tests for autocorrelation. All the models for the 26 industries pass the Hansen test for over-identification at the 10% level or better, suggesting the validity of the instrument set used. With regard to tests for autocorrelation, none show evidence of second-order serial correlation in the differenced residuals (based on a 10% significance level), suggesting the overall consistency of our estimates.

Table 4 shows that in 11 out of 26 industries the impact of assistance on TFP increases monotonically for those firms that receive less than 10, 10–19 and 20–49% assistant rates; for a further 10 industries assistance rates between 1–9% have a significantly positive effect while the impact is greater for those in receipt of 10–19% assistance rates, and approximately the same for those receiving 20–49% compared to 10–19% assistance. Only for the petroleum sector, measuring instruments, electronic power generation and gas production is there a decline in the positive impact of assistance on TFP for the 20–49% sub-group compared to 10–19%. Tobacco is the only sector where assistance (for any sub-group) has no statistically significant impact on TFP. In 9 industries firms with assistance rates 50+% experienced significant declines in TFP (especially coal mining, electronic power generation and water production), while in nonmetal products receiving 50+% assistance boosted TFP by 5.7% and in metal products the impact was 13.7% higher TFP (only in the latter sector does TFP increases monotonically across all assistance rate sub-groups).

On average across all 26 industries, the parameter estimates in Table 4 show that firms receiving assistance rates of 1–10, 10–19, 20–49 and 50+% experienced on average 4.5, 9.4, 9.2 and −3% gains in TFP, respectively,Footnote 14 which is consistent with the theoretical model in the appendix which proposes that “over-assistance” induces firm managers to substitute managerial effort for rent-seeking effort, which consequently lowers TFP. This complements the result obtained by Aghion et al. (2015) that “… driving the Herfindahl for the dispersion of tax holidays on income taxes and value-added taxes to 0 would lead to an increase in TFP of 8.5 to 10.3 percentage points” (pp. 15–16). Thus both studies show that assistance to industry in China has an impact on firm-level TFP.

Based on the results from estimating Eq. (1), we can also calculate an index of TFP. The obvious approach would be \(ln\widehat P_{it} = y_{it} - \widehat \alpha _Ee_{it} - \widehat \alpha _Mm_{it} - \widehat \alpha _Kk_{it}\), but this is not a proper TFP index, because the measure of input growth (\(\widehat \alpha _Ee_{it} - \widehat \alpha _Mm_{it} - \widehat \alpha _Kk_{it}\)) does not satisfy axiom X5 (proportionality) in O’Donnell (2015), except in the case of constant returns-to-scale. The solution is to restore proportionality by using a special case of the Färe and Primont (1995) input index:

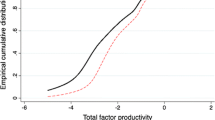

and use Eq. (2) to summarise our results. Figure 1, which shows the cumulative distribution of TFP for firms with different rates of assistance, confirms that assisted firms generally had higher TFP, with a gap between the best and worst performing sub-groups of 0.133 at the widest point.Footnote 15

Lastly, even though in estimating Eq. (1) we allow for fixed effects, endogeneity and selection bias for certain key right-hand-side variables (via instrumenting intermediate inputs, labour, capital, assistance rates, political affiliation, capital ownership, exporting, and R&D), we also as a robustness check re-estimated Eq. (1) using a ‘matched’ sample approach (Imbens and Rubin 2015), even though the asymptotic theory for matching and then using system GMM is not yet developed. Separately for each of the 26 industries covered here we used a propensity-score approach to predict the likelihood of receiving assistance and then used one-to-one ‘matching’ to create an overlapping ‘treatment’ and ‘control’ group of firms (the STATA procedure PSMATCH2 was used).Footnote 16 This smaller sample was then used to re-estimate Eq. (1)—using system-GMM but this time not instrumenting assistance rates—with the key results reported in Table 4 (lower half). Tests of the appropriateness of the ‘matching’ technique (using PSTEST in STATA) based on Rubin’s B and R show that the ‘treatment’ and ‘control’ groups are sufficiently balanced. Moreover, the results obtained with respect to the parameter estimates attached to the assistance rate dummies are generally similar; the averages across all industries of the impact of assistance on TFP for the various sub-groups are less than 10 percentage points different when the ‘full’ data and ‘matched’ data results are compared. This confirms that the estimates produced in Table 4 (top half) of the impact of assistance on TFP are indeed robust.

5 TFP growth and the impact of assistance

The previous section shows the impact of receiving assistance on the level of TFP, while this section takes the next step: we decompose the growth of aggregate TFP and consider the contribution of government assistance. That is, while in Section 4 we have found that assistance generally leads to higher levels of TFP, evidence is still needed as to whether government aid induces higher aggregate TFP growth—where the latter includes firms in operation throughout 1998–2007 (covering within-firm and inter-firm changes to TFP) as well as the impact of new firm entry and firm closures.Footnote 17 Put differently, TFP growth is not just about changes in the distribution of the TFP level across firms, but also the (re-)allocation of resources across firms as they expand or contract.

We measure TFP growth and its decomposition using the well-known Haltiwanger approach (Foster et al. 1998). The index of productivity in year t is defined as a geometrically weighted average of individual firm-level productivities (Eq. 2). This index and its growth between t and t−k can therefore be written as follows:Footnote 18

where P measures productivity and θit is the share of output for firm i in period t. Thus, productivity growth can be expressed as follows:

Using estimates of lnPt for 1998 and 2007 (Eq. 2) and Eqs. (3, 4), we obtain the results in Table 5. The latter shows that overall Chinese firms achieve on average TFP growth of 7.9% p.a., with 80%Footnote 19 of this attributable to the impact of new firm entry (firm closure actually decreased TFP growth by 0.3% p.a.). The next major source was from continuing firms becoming internally more productive (contributing 21% of overall growthFootnote 20).

Table 5 also shows that SOE’s contributed 2.1% to overall TFP growth (or 27% of the totalFootnote 21), which is significantly below what might have been expected given their share of total output in 1998 (over 42%), and in part reflects their having lower TFP levels. Much of the contribution to SOE TFP growth was due to the closure of inefficient firms (contributing 62%Footnote 22 of total TFP growth). Similarly, Table 5 shows that firms that had strong political connections (i.e., lishu relationships with provincial or central government) also contributed much less to overall TFP growth, which is in line with the results for SOE’s (see Wu et al. 2012).

Importantly, Table 5 shows that firms receiving assistance made a relatively larger contribution to overall TFP growth p.a. (non-assisted firms, accounting for some 49% of output in 1998, contributed just over 25% of overall TFP growth and thus in aggregate the assisted group contributed around 75% of total TFP growth). Further, taking account of their share of output and hence relative importance in 1998,Footnote 23 all the assisted sub-groups performed better than the non-assisted group, reflecting both stronger improvements in TFP over time and larger increases in their shares of total output (note, in Table 5 the TFP index for firms with a 50+% assistance rate is higher than the TFP indices for non-assisted and <10% assisted firms; in Fig. 1, the average TFP of the 50+% sub-group is about the same or lower with the difference being due to TFP not being weighted by output shares in Fig. 1). The entry of more productive and the closure of less productive firms dominated the composition of TFP growth in non-assisted firms (accounting for 44 and 33% of overall growth, respectively), and there was also a significant contribution from ‘within-firm’ improvements in productivity. Overall, this is in line with what might be expected when no government incentives are received and firms face the full impact of market competition. For the assisted sub-groups, there is much less reliance on the closure of less productive firms as a means of improving TFP growth (contributions were either small or negative) which suggests that assistance may have helped to ‘prop-up’ a proportion of relatively unproductive firms. There is also little evidence to suggest that assisted firms overall experienced higher ‘with-firm’ productivity gains, relative to non-assisted firms. Instead, the major source of TFP improvement for assisted firms tended to be the opening of new firms, perhaps in part attracted (facilitated) by the subsidies available from government.

Lastly, we present results when firms are grouped by whether they were State-owned, had any political connections, and received assistance (at any positive rate). Part of the reason for grouping the data in this way is that during the period covered the proportion of output attributed to firms with no political connections increased from 12.9% in 1998 to over 55% by 2007 (Table 5). And yet Table 3 shows that on average between 1998–2007 nearly 57% of firms receiving assistance had no formal political connections. This provides strong support for the claim made by Haley and Haley (2013, Chapter 1) that under the operation of Chinese State Capitalism, the government has become less reliant on formal, traditional lishu relationships and instead ensures firms are dependent on government for financial assistance that creates mutual dependence.

Table 6 shows that firms receiving government financial assistance that had no formal political connections and were not State-owned had (by some margin) the best performance: this sub-group contributed nearly 59% to overall TFP growth, with the highest TFP levels in both 1998 and 2007, and the largest increase in market share (up from 8% to nearly 45%). In this sub-group, some 97% of TFP growth was due to the entry of new firms. Next, in terms of the contribution to aggregate TFP growth, comprised firms receiving no assistance, and as stated above net entry and, to a lesser extent, ‘within-firm’ improvements had the largest impact on productivity growth.

In contrast, firms that received assistance and were either SOE’s (with no formal political links, i.e. lishu relationship) or had political connections (but were not SOE’s)—the ‘remainder’ sub-group—contributed the least to TFP growth, despite their having some 26% of total output in 1998 (which only fell to 23% by 2007). For this sub-group, there were significant, but counter-balancing contributions to TFP growth from positive ‘within-firm’ improvements and the entry of more productive firms, and even larger negative impacts through the closure of more productive firms. The final sub-group (assisted SOE’s with political connections) contributed some 9% to overall TFP growth, but they had the lowest TFP levels in both years and lost around 50% of their market share over the period. This sub-group saw little improvement in TFP growth through the ‘within-firm’ contribution, although there were significant gains through the most productive ‘continuing’ firms gaining market shares at the expense of the least productive firms (‘between-firm’ effects).

6 Summary and conclusions

Industrial policy, particularly through the provision of large-scale assistance to industry in the form of ‘tax holidays’ and subsidies to firms, is very important in China (e.g., the data used here for medium- to large-sized firms in manufacturing and utilities shows that in 2007 over 72% of firms received government assistance, worth around 13% of their value-added). Recently Aghion et al. (2015) have reported that the distribution of government assistance to firms in China has enhanced productivity over the 1998–2007 period, given that it was allocated to competitive sectors and /or fostered competition in a sector. However, they did not test directly whether receiving assistance had a direct impact on each firms’ TFP, perhaps thereby introducing distortions that work against the productivity-enhancing effects associated with the distribution of assistance.

A major contribution of this paper has been to use Chinese firm-level panel data for 1998–2007 to introduce measures of assistance received by each firm directly into industry-level production functions determining firm output. The latter were estimated using a system-GMM econometric approach (with assistance instrumented by its lagged valued); and by estimating production functions using ‘matched’ data comprising firms receiving assistance and firms not receiving ‘treatment’ who nonetheless had very similar characteristics to the assisted sub-group. The results indicated that, across the 26 industries considered, Chinese firms that received assistance had higher TFP during 1998–2007, although there is some evidence that too high a level of assistance has negative consequences for TFP. On average the results showed that firms receiving assistance rates of 1–10, 10–19, 20–49 and 50+% experienced on average 4.5, 9.4, 9.2 and −3% gains in TFP, respectively.

While we find that government assistance generally boosted TFP at the firm level, we also show that aggregate TFP growth was largely achieved through assisted new firms being ‘encouraged’ to start-up rather than through continuing firms improving, and there is also some evidence that closure rates were truncated as a result of government assistance. That said, overall assisted firms did contribute more to TFP growth than non-assisted firms, but this was very much ‘driven’ by a sub-group that received government financial assistance but had no formal political connections and were not State-owned. Assisted firms that were SOE’s and/or had political connections were the lowest performers, which suggests that state policy to boost TFP worked best in China when it was de-coupled from formal political control.

Turning to further work that could be done, we have not at this stage set out to test if different forms of assistance (i.e., different types of tax holidays as well as subsidies to firms) have differential impacts. Our initial attempts to do this using system-GMM suffered from collinearity problems, so further experimentation with regard to modelling is necessary. Taking the Haltiwanger results a stage further, it would also be interesting to model directly the impact of assistance on the (hazard rate of) firm closure.

Notes

Competition-friendly policies are defined as those that allocate assistance to a wide group of firms in a sector (so encouraging competition) and/or that target younger and more productive firms.

Karhunen and Huovari (2015), using similar data, confirm these results for Finland.

Note, this is not limited to ‘catch-up’ in developing economies; ‘network failures’ in general arise because technological know-how (broadly defined) is partly tacit and therefore cannot be diffused easily. Networks can be important for the transfer of such tacit knowledge (they are mutual learning processes fostered by well-managed collaboration between specialists in complementary fields, as well as between designers, producers and end-users), and they can also partly overcome the problems associated with firms experiencing bounded rationality and consequently bounded vision (Teece and Pisano 1998).

Closer ties to government can also help businesses to overcome market and state failures in securing property rights and enforcing contracts—Li et al. (2008) and Zhou (2013). Note, therefore, this definition of politically connected firms is different to the approach adopted by Faccio (2006), who looked at such connections across 47 countries (excluding China).

There are currently around 15 ‘pillar’ industries set by the central government in China, from technology-intensive sectors like aerospace and computing, through to wholesale and retailing. The ‘culture’ sector is also now a pillar industry.

Or when corruption is present, it may be possible for them to use the extra profits to reward themselves more directly.

Others (e.g., Aghion et al. 2015) have also included the ‘implied’ rate of interest firms paid on loans (calculated as interest payments divided by current liabilities) to measure the extent to which firms may have received loans at below-market interest rates. Certainly the implied interest across firms did decline between 1998 and 2004 (before rising again between 2004 and 2007)−see Fig. 2 in the unpublished appendix. However, the percentage of firms paying zero interest, because they had no borrowings, also rose dramatically from around 29% in 1998 to around 42% in 2007 (mostly due to the growth in importance of smaller privately-owned businesses during this period—see Table 1 in Ding et al. (2015)—who were generally unable to secure loans from the Chinese banking system). Given this, no direct measure of the ‘implied’ cost of borrowing is included in this study (although, note, we do include measures on firm liquidity into our determinants of TFP—see Table 3 below).

Table 8 in the unpublished appendix provides the breakdown used in this study.

That is, not the average across firms—totals for each sub-group were instead used.

Table 9 in the unpublished appendix provides a breakdown of assistance rates across ownership sub-groups by type of assistance. It is also important to note that while SOEs had lower rates of assistance, the NBS data shows that in 1998 SOEs received nearly 39% of all assistance by value (¥64.6 of a total of ¥167.4 billion); in 2007 they received just over 14% of all assistance (¥207.9 of a total of ¥1453.2 billion).

We use Roodman’s (2009) ‘collapse’ procedure in all our estimations using XTABOND2 in STATA, such that only the instruments applicable to each variable—not the full instrument set covering all variables—are used. Too many instruments have been shown to often result in a Hansen p-value at or very close to 1.

Note we expect that (in particular) receiving assistance, being politically affiliated and State-owned are endogenous (to each other) and that is why we instrument these variables and test whether the instruments used are appropriate. With regard therefore to identifying causality, we have endogenous relationships which imply causality in both directions, and we are able to take account of this through the use of an instrumental variable approach. Only if a set of structural equations were estimated with say a FIML approach (which implies the as yet to be developed methodology of multi-equation fixed effects modelling which is beyond the scope of this paper) could structural parameters be retrieved and direct causal relationships amongst all the endogenous variables be separated out. Instead here we can identify the reduced form causal impact of a change in assistance on TFP, based on an unbiased parameter estimates, given we instrument endogenous variables.

This is based on taking a simple average across all industries (irrespective of whether parameter estimates were statistically significant or not) and expressing the results as eΣα − 1.

The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test for equality of distribution functions between the 20 to <50% and 50+% distributions has a d-statistic of −0.133 (and associated p-value of 0.00).

The equation used for the propensity score matching was \(\begin{array}{l}Assisted_{it} + \alpha _0 + \alpha _1\,Assisted_{it - 1} + \alpha _2\\ \left( {High\,political\,affiliation\, \times \,SOE} \right)_{it} \;+\; \alpha _xZ_{it} + \mu _{it}\end{array}\) (3)

where Zit comprises a sets of control variables determining the probability of being assisted (involving the indicated variables in Table 3, including industry and year dummies).

In the context of the exercise undertaken here, firms that are in the dataset in 2007 and not 1998 are deemed ‘new entrants’; firms that appear in 1998 but not 2007 are classified as closed. Since the NBS dataset does not include enterprises with annual sales below ¥5 million, it is important to note that about 80% of all industrial firms are excluded from the sample. However, as shown in Brandt. et al. (2012), using the full census of firms periodically carried out in China, the omitted firms only account for some 9.9% of output in 2004, and 2.5% of exports. Moreover, a comparison of 1995 NBS and Census data shows the NBS has a similar level of coverage, allowing Brandt. et al. (2012) to state that “… the NBS decision rule on which firms to include in their annual sample is not introducing any systematic bias in our estimates”. Thus the issue that firms may still exist but be below the ¥5 million benchmark is not likely to have any significant impact here.

As will be seen, we combine the between-firm and cross-firm effects into one ‘between firm’ effect.

i.e., 6.28 ÷ 7.88.

i.e., 1.64 ÷ 7.88.

i.e., 2.11 ÷ 7.88.

i.e., 1.31 ÷ 2.11.

Recall the figures in Column 1 (Table 5) reflect two components, as shown in Eq. (3): a within-subgroup productivity change and the relative importance of the subgroup over time. That is, we can rewrite Eq. (3) as: \({\mathrm{\Delta }}lnP_t = \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_i {\theta _{it}lnP_{it}} - \mathop {\sum}\nolimits_i {\theta _{it - k}lnP_{it - k}}\)

Note that we can shift the location of productivity ω to make sure the optimal choice is between 0 and 1, without loss of generality.

Note that η < −1, so γ* > 0. We assume \(\alpha _K > \frac{{ - 1}}{{\left( {1 + \eta } \right)}}\), so γ* < 1. Thus, the optimal effort is an interior solution.

References

Aghion P, Cai J, Dewatripont M, Du L, Harrison A, Legros P (2015) Industrial policy and competition. Am Econ J Macroecon 7(4):1–32

Arellano M, Bond S (1991) Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. Rev Econ Stud 58(2):277–297

Arrow KJ (1962) The economic implications of learning by doing. Rev Econ Stud 29:155–173

Arrow KJ, Debreu G (1954) Existence of an equilibrium for a competitive economy. Econometrica 22(3):265–290. https://doi.org/10.2307/1907353

Blundell R, Bond S (1998) Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. J Econ 87:115–143

Brandt L, Van Biesebroeck J, Zhang Y (2012) Creative accounting or creative destruction? Firm-level productivity growth in Chinese manufacturing. J Dev Econ 97:339–351

Casson M (1999) Market failure and government support for business: a comment, for the DTI, mimeo

Cohen E (2006) Theoretical foundations of industrial policy. EIB Pap 11(1):85–106

Ding S, Guariglia A, Harris R (2015) The determinants of productivity in Chinese large and medium-sized industrial firms, 1998–2007. J Product Anal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-015-0460-0

Du L, Harrison A, Jefferson G (2014) FDI spillovers and industrial policy: the role of tariffs and tax holidays. World Dev 64:366–383

Einio E (2014) R&D subsidies and company performance: evidence from geographic variation in government funding based on the ERDF population-density rule. Rev Econ Stat 96(4):710–728

European Commission (2002) A study of business support services and market failure. A report to the European Commission, the Foundation for SME Development, University of Durham, July. http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/3646/attachments/1/translations/en/renditions/pdf

Faccio M (2006) Politically connected firms. Am Econ Rev 96(1):369–386

Färe R, Primont D (1995) Multi-output production and duality: theory and applications. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston

Felipe J (ed) (2015) Development and modern industrial policy in practice: issues and country experiences, Asian Development Bank and Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK

Foster L, Haltiwanger J, Krizan CJ (1998) Aggregate productivity growth: lessons from microeconomic evidence, NBER Working Paper No. 6803

Girma S, Gong Y, Gorg H, Zhihong Y (2009) Can production subsidies explain China’s export performance? Evidence from firm-level data. Scand J Econ 111(4):863–891

Greenwald BC, Stiglitz JE (1986) Externalities in economies with imperfect information and incomplete markets. Q J Econ 101(2):229–264. https://doi.org/10.2307/1891114

Haley UCV, Haley GT (2013) Subsidies to Chinese industry: state capitalism, business strategy, and trade policy. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Hanke PC, Heine K (2015) Subsidies and corporate governance—an agency approach. Manag Decis Econ 36:256–264

Harrison A, Shenggen F, Kanbur R, Wei SJ, Zhang X (2014) Trade and Industrial Policy: China in the 1990s to Today. The Oxford Companion to the Economics of China. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 161–170

Heilmann S, Shih L (2013) The rise of industrial policy in China, 1978–2012. Harvard-Yenching Institute Working paper series

Huang C-H (2015) Tax credits and total factor productivity: firm-level evidence from Taiwan. J Technol Transf 40(6):932–947

Imbens GW, Rubin DB (2015) Causal inference for statistics, social, and biomedical sciences: an introduction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Irwin DA, Klenow PJ (1996) High-tech R&D subsidies: estimating the effects of Sematech. J Int Econ 40:323–344

Jacobs J (1970) The economy of cities. Jonathan Cape, London

Jacobs J (1986) Cities and the wealth of nations. Penguin, Harmondsworth

Khan MH (2015) Industrial policy design and implementation challenges, In: Felipe J (ed) Development and modern industrial policy in practice: issues and country experiences. Asian Development Bank and Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK, pp 94–126

Karhunen H, Huovari J (2015) R&D subsidies and productivity in SMEs. Small Bus Econ 45(4):805–823

Koski H, Pajarinen M (2015) Subsidies, the shadow of death and labor productivity. J Ind Competition Trade 15:189–204

Levinsohn J, Petrin A (2003) Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservable. Rev Econ Stud 70(2):317–341

Li H, Zhou L-A (2005) Political turnover and economic performance: the incentive role of personnel control in China. J Public Econ 89:1743–1762

Li H, Meng L, Wang Q, Zhou L-A (2008) Political connections, financing and firm performance: evidence from Chinese private firms. J Dev Econ 87:283–299

Lin JY, Long CX, Zhang X (2015) Industrial diversification in the People’s Republic of China, In: Felipe J (ed) Development and modern industrial policy in practice: issues and country experiences. Asian Development Bank and Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK, pp 197–218

Managi S (2010) Productivity measures and effects from subsidies and trade: an empirical analysis for Japan’s forestry. Appl Econ 42:3871–3883

Marshall A (1890) Principles of Economics. Macmillan, London

Metcalfe S, Georghiou L (1998) Equilibrium and evolutionary foundations of technology policy. STI Rev 1998(1):22–26. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/sti-review_sti_rev-v1998-1-en

O’Donnell CJ (2015) Using information about technologies, markets and firm behaviour to decomose a proper productivity index. J Econom. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2015.06.009

Olley S, Pakes A (1996) The dynamics of productivity in the telecommunications equipment industry. Econometrica 64(6):1263–1297

Porter ME (1990) The competitive advantage of nations. Free Press, New York, NY

Rodrik D (2006) Industrial development: stylized facts and policies revised. Copy at http://j.mp/2oz4ySE. http://drodrik.scholar.harvard.edu/publications/industrial-development-stylized-facts-and-policies-revised

Romer PM (1986) Increasing returns and long-run growth. J Political Econ 94:1002–1037

Roodman D (2009) How to doxtabond2: an introduction to difference and system GMM in Stata. Stata J 9:86–136

Rubin DB (2001) Using propensity scores to help design observational studies: application to the tobacco litigation. Health Serv Outcomes Res Methodol 2:169–188

Schwartz G, Clements B (1999) Government subsidies. J Economic Surv 13(2):119–147

Stiglitz JE, Lin JY (eds) (2013) The industrial policy revolution I: the role of government beyond ideology. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, UK

Stiglitz JE, Lin JY, Monga C (2013) Introduction: the rejuvenation of industrial policy. In: Stiglitz JE, Lin JY (eds) The industrial policy revolution I: the role of government beyond ideology, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, UK, pp 1–18

Tan J, Li S, Xia J (2007) When iron fist, visible hand, and invisible hand meet: firm-level effects of varying institutional environments in China. J Bus Res 60:786–794

Teece DJ, Pisano G (1998) The Dynamic Capabilities of Firms: an Introduction’. In: Dosi G, Teece DJ, Chytry J (eds) Technology, organization and competitiveness. Perspectives on industrial and corporate change. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 193–214

Thun E (2004) Industrial policy, Chinese style: FDI, regulation, and dreams of national champions in the auto sector. J East Asian Stud 4:453–489

Walder AG (1992) Property rights and stratification in socialist redistributive economies. Am Sociol Rev 57:524–539

Windmeijer F (2005) A finite sample correction for the variance of linear efficient two-step GMM estimators. J Econ 126:25–51

Wu W, Wu C, Rui OM (2012) Ownership and the value of political connections: evidence from China. Eur Financ Manag 18:695–729

Yu M, Hui Y, Pan H (2010) Political connections, rent seeking, and the fiscal subsidy efficiency of local governments. (In Chinese with English summary). Jingji Yanjiu/Economic Res J 45(3):65–77

Xia J, Li S, Long C (2009) The transformation of collectively owned enterprises and its outcomes in China, 2001-05. World Dev 37:1651–1662

Zhou W (2013) Political connections and entrepreneurial investment: evidence from China’s transition economy. J Bus Ventur 28:299–315

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

For simplicity, the firm employs a Cobb-Douglas function:

where Y, E, M and K refer to output, employment, intermediate inputs and capital stock; ω is the physical productivity of the firm, and we assume constant return to scale so αE + αM + αE = 1. With imperfect competition, demand is:

and we assume the elasticity of demand is η < −1; P is the price of the product; and f(x) is the quality of the product which is a function of the managerial effort x. We assume f(x) is increasing in x.

Factor prices are PE, PM, and PK(γ) and in particular, the ‘user’ cost of capital PK(γ) is a function of government assistance γ (with \(\frac{{\partial P_K}}{{\partial \gamma }} < 0\)).

The firm maximises profit, subjective to the production function (A.1) and the demand curve (A.2):

After some manipulation, the profit function can be shown to be:

where \({\mathrm{\Phi }} = \left( { - \frac{1}{\eta }} \right)\left( {\frac{\eta }{{\eta + 1}}} \right)^{\eta + 1}\left[ {P_E^{\alpha_E}P_M^{\alpha_M}\frac{1}{{\alpha _E^{\alpha_E}\alpha _E^{\alpha_M}\alpha _K^{\alpha_K}}}} \right]^{\eta + 1}\), which does not involve x or γ.

As well as managerial effort to boost product quality, managers can also exert rent-seeking effort q:

where g(q), the share of government assistance that directly rewards management, is increasing in rent-seeking effort q. Assuming that the nominal salary of managers is a share β of firm profit, we can write the problem of the manager as:

subject to the constraint that total effort (x + q) = 1. This imposes a trade-off for the manager of allocating her effort between pursuing TFP (hence higher profit) and pursuing rent-seeking to boost her private rewards without having to make the effort of boosting TFP.

To simplify the solution of the problem (and without loss of generality), we set f(x) = x and g(q) = eq−1, and \(P_K\left( \gamma \right) = e^{ - \gamma }\overline P _K\) where \(\overline P _K = 1\) is the normalised market ‘user’ cost of capital. Thus, the first order condition of the manager’s problem is

where the first term measures the marginal return to managerial effort from firm profit that determines nominal salary, while the second term represents the marginal return of managerial effort from rent-seeking. The former is positive while the latter is negative (as she has less rent-seeking effort to spend the more profit-seeking effort is allocated). The trade-off between the two implies optimal managerial effort is:Footnote 24

Note that \(x^{\ast}(\gamma)\) is a concave function of γ, with a maximum at \(\gamma ^ \ast = \frac{{ - 1}}{{\alpha _K\left( {1 + \eta } \right)}}\).Footnote 25 Also, measured TFP is:

As η < −1, measured TFP is higher if physical productivity ω is higher. More importantly, assistance generally increase TFP except when assistance is too high. This is summarized in the following proposition.

Proposition 1: When\(\gamma \;<\; \gamma^{\ast}, x^{\ast}(\gamma)\) and TFP(γ) are increasing in γ; when \(\gamma \ge \gamma^{\ast}, x^{\ast}(\gamma)\) and TFP(γ) are decreasing in γ.

That is, government subsidies lower the marginal cost of production and provide an incentive to the manager to allocate more effort to pursue higher profitability (via higher TFP), but over-assistance induces the manager to substitute managerial effort by rent-seeking effort, and consequently lowers TFP.

Unpublished appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Harris, R., Li, S. Government assistance and total factor productivity: firm-level evidence from China. J Prod Anal 52, 1–27 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-019-00559-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11123-019-00559-4