Abstract

The number of return migrants from the U.S. to Mexico has swelled in recent years, yet we know little about the academic performance of the over 500,000 U.S.-born children who have accompanied them. This study compares Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) test scores of U.S.-born children of return migrants in Mexico to two groups: Mexican-born students in Mexico and students in the U.S. born to Spanish-speaking immigrant parents. While previous work often highlights the struggles these children face in adapting to schools in Mexico, at age 15 they attain slightly higher PISA scores than their Mexican-born counterparts. However, these adolescents’ scores are much lower than similar youths’ in the U.S. Results for both comparisons change little in models controlling for variables related to immigrant selection and are consistent across possible individual moderators, including age at migration. This paper highlights the importance of a cross-border perspective and attention to institutional context in studies of immigrant education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over 2 million Mexican migrants in the U.S. made the journey back to Mexico between 2005 and 2014, making it the largest return migration flow in the world (Gonzalez-Barrera, 2015). U.S.-born children of these Mexican return migrants now constitute a sizable population in Mexico, since 2010 exceeding 500,000, or 2% of school enrollment (Masferrer, 2021, p. 39). Although this population has begun to receive scholarly attention, we know little about their educational outcomes at the national level. Are these students strangers in the homeland, struggling to adjust to a foreign society and school system? Or are they able to capitalize on their or their parents’ transnational experiences to excel in school? Knowing how these students are doing academically is relevant to both Mexican and U.S. policymakers interested in promoting the well-being of this growing but often invisible group of “students we share” (Gándara & Jensen, 2021).

These U.S.-born migrants also raise a number of theoretical questions for studies of immigrant incorporation. What does it mean to assimilate into a society where ethnic, cultural, and legal barriers are at a minimum? How does incorporation play out when the immigrant appears part of the mainstream? Does a difficult “context of exit” outweigh a favorable “context of return” (Silver, 2018)? Because Mexico lacks national standardized testing (Santibañez, 2021), we do not know whether the educational situation of U.S.-born children of Mexican return migrants is generally one of advantage or disadvantage. Furthermore, if disparities exist, we do not know whether this is due to the challenges of migration or a process of selection of which families choose or are forced to migrate back to Mexico.

To help answer these questions, this paper relies on the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) to characterize the educational achievement of U.S.-born children of return migrants in Mexico. PISA assesses 15-year-olds’ reading, math, and science skills every three years in dozens of countries worldwide (Schleicher, 2019). This paper uses data from 2009 to 2012 to make two sets of comparisons. First, to assess the degree of integration or assimilation into their ancestral society, I compare U.S.-born children of return migrants to local non-migrants. Second, I estimate how these children’s academic trajectories might have progressed had their parents not return-migrated, comparing these children to a counterfactual group in the U.S. I also investigate the selection of return migrant parents and assess how this may impact their children’s achievement.

I find that, compared to Mexican adolescents, U.S.-born students in Mexico perform slightly better on all three subjects in PISA. These effect estimates are nearly identical in models that do or do not control for pre-return-migration selection variables or post-migration mediators. These results vary somewhat by gender and rurality, but age at migration and region have only weak effects. On the other hand, these adolescents obtain much lower scores than children of Spanish-speaking immigrants in the U.S. Reading scores are especially low, at half a standard deviation below the U.S. comparison group. Controlling for variables meant to measure selection into migration only slightly narrows the estimated disparity. Analyses of moderators show little difference across gender, rurality, age at migration, or region. These results tell a story of educational assimilation: counterfactual estimates suggest that moving to Mexico results in a fall in PISA scores to just above the relatively low local average. In an institutional context characterized by under-resourced Mexican schools (Santibañez, 2021), educational assimilation weakens these adolescents’ educational standing. It is also likely that unmeasured disadvantageous characteristics of return migrant families, such being undocumented in the U.S. (Landale et al., 2016), impact the educational outcomes of these children.

This paper makes three larger contributions. First, it highlights the importance that institutional factors – such as the Mexican school system – can assume in the assimilation process (Crul & Vermeulen, 2003; Midtbøen & Nadim, 2022; Schneider et al., 2022). Second, this paper showcases the strengths of a cross-border perspective that considers sending and receiving contexts in tandem (Waldinger, 2017) and its relevance to research on immigrant education. Finally, this paper pushes for consideration of an increasingly significant group in Mexico and other countries of emigration: foreign-born children of return migrants.

Research Context

The Mexico-U.S. migration system has transformed dramatically in the 21st century (Durand & Massey, 2019). After decades of high migration from Mexico to the U.S., the number of Mexican immigrants in the U.S. peaked at 12.8 million in 2007 and has declined since, numbering 11.4 million in 2019 (Gonzalez-Barrera, 2021). This net negative migration is due both to lower rates of entry and rising rates of return (Durand & Massey, 2019). From 2005 to 2010, 1.39 million Mexican immigrants returned to Mexico from the U.S., and 710,000 returned between 2013 and 2018 (Gonzalez-Barrera, 2021).

A large part of the return flows has been undocumented immigrants. From 2010 to 2018, 2.6 million undocumented Mexican immigrants returned to Mexico (Warren, 2020). A rapid increase in deportations is responsible for a large part of this outflow (Durand & Massey, 2019, p. 37), but Warren (2020) highlights that 45% of undocumented Mexican immigrants returned voluntarily. Precarious economic conditions in the U.S. and a stabilizing Mexican economy have increased incentives to return (Gonzalez-Barrera, 2021).

As economic conditions and U.S. immigration policy have changed, so has the composition of Mexican return migrants. Campos-Vazquez and Lara (2012) find a shift from positive to negative selection when compared to the full Mexican population: In 1990, return migrants had more years of schooling and higher wages than their stay-at-home compatriots, whereas in 2010 they tended to have less schooling and earn lower wages. Denier and Masferrer (2020) find evidence of return migrant wage decline between 2000 and 2015. Parrado and Gutierrez (2016) argue that the lower wages of return migrants in 2010 compared to 1990 and 2000 are due to the less voluntary nature of return migration in recent years, and they also find decreases in entrepreneurship and the ability to remain inactive. For deportees, accumulation of valuable skills and capital is cut short (Cassarino, 2004). Using data from 2011 to 2013, Diaz et al. (2016) show that negative selection also characterizes comparisons to Mexican immigrants who stay in the U.S.; for example, return migrants are less likely to possess a high school or college degree. After return, these migrants face challenges to reintegration (Escoto & Masferrer, 2021), with inadequate government programs to aid them (Jacobo Suárez & Cárdenas Alaminos, 2019).

Children are virtually absent from most discussions of return migration, yet their numbers are significant. In 2000, the Mexican census counted 258,000 U.S.-born minors; by 2010, this had more than doubled to 570,000 (Masferrer et al., 2019). This number has remained steady in the years since: the 2020 Mexican census reports that 500,600 minors, or about 2% of the school-age population, were born in the U.S. (Masferrer, 2021, p. 39). Hamilton et al. (2023) estimate that one in six U.S.-born children in Mexico in 2014 to 2018 were “de facto deported,” meaning they accompanied a deported parent.

Although there has not yet been a large-scale investigation of these children’s educational outcomes, researchers have begun to study this group. Most of this work emphasizes the difficulties that this generation faces in the Mexican “homeland.” Zúñiga and Giorguli Saucedo (2018) dub children of return migrants to Mexico – whether U.S.- or Mexican-born – the “0.5 generation.”Footnote 1 Like the “1.5 generation” label for children who migrate at a young age (Portes & Rumbaut, 2001), “0.5 generation” foregrounds liminality; they cannot be easily grouped with either the native-born “0 generation” or the “first generation” of migrants more broadly, and this in-betweenness contributes to their particular challenges navigating an education system and society that feels both familiar and foreign.

These challenges are myriad. Despite usually possessing oral proficiency in both Spanish and English, the written competency of children of return migrants often lags behind (Despagne & Jacobo Suárez, 2019; Gándara, 2020; González et al., 2016; Santibañez, 2021). Especially when they first arrive, their peers often treat them as outsiders (Meyers, 2014), and the stigma they face can be exacerbated by the political climate, such as the 2016 election (Bybee et al., 2020). Conflicts also occur psychologically, as these children struggle with their identity and feelings of belonging (Bybee et al., 2020; Despagne & Jacobo Suárez, 2019). Yet their appearance and oral fluency often renders them invisible to teachers (Sánchez García & Hamann, 2016), and resources for immigrant students are lacking in Mexico (Santibañez, 2021). Even navigating the complicated bureaucracy to enroll in school or finding the money for transportation, uniforms, and school supplies may be out of reach for return migrant families (Gándara, 2020; Mateos, 2019), although government intervention appears to have improved educational access in recent years (Amuedo-Dorantes & Juarez, 2022). Furthermore, family separation is a frequent, stressful feature of migration that is common for this population (González et al., 2016; Hamilton et al., 2023; Masferrer et al., 2019; Zúñiga, 2018). These factors are compounded by the harsh immigration regime in the U.S. that encourages and forces the departure of these families (Waldinger, 2021).

The generally negative selection of migrant parents may further compound their children’s disadvantage. Observing which migrant families both voluntarily and involuntarily return to Mexico, Hernández-León et al. (2020, p. 94) suggest that “U.S. policies […] effectively externalize downward assimilation to communities of origin.” Migrants who return to Mexico from the U.S. may be those having the roughest time in the host country; hence their children are a selected group, more likely to struggle in the homeland due to disadvantage accrued before return. Furthermore, less-educated migrant parents are less likely to find lucrative work and more likely to be targeted for deportation, so controlling for family background may narrow disparities.

Yet not all work on children of return migrant conceives of them as consigned to disadvantage. Zúñiga and Giorguli Saucedo (2018) and Hernández-León et al. (2020) see some of the children in their studies benefiting from dual nationality. Similarly, in an intensive ethnography in two schools in central Mexico, Bybee et al. (2020, p. 135) observe a “star student” discourse: “The notion of American-Mexican pupils as ‘good students’ was common enough in both schools that it extended beyond English classes where they had an obvious advantage.” Although these students experienced bullying and exclusion due to their perceived foreignness, the privilege of binational education and other resources gave some of them a leg up in school.

Theory

Individual Explanations

How can we understand the varied results from previous studies of children of return migrants in Mexico? Theories of return migrant integration point to possible explanations for both positive and negative outcomes of their U.S.-born children. This subsection focuses on individual, non-school explanations (Downey et al., 2004; Entwisle & Alexander, 1992). First, these theories help us understand possible disadvantage. The perspective of neoclassical economics suggests that return migrant families may not have found lucrative employment in the host country (Todaro, 1980). Even in cases where they have, a transnationalist perspective (Basch et al., 1994; Portes et al., 1999) emphasizes that alienation and exclusion in the “home” society can still afflict return migrants and their children as they struggle with their identities. Institutions for investment and activation of resources gained in the U.S. may also be lacking (Hagan & Wassink, 2020, p. 539). In addition, migrants who are not ready and willing to migrate (Cassarino, 2004) – as in the case of deportation, which recently accounts for 55% of all return migrations to Mexico (Warren, 2020) – are less likely to possess the resources to ease re-entry into Mexican society. The result can be traumatic for children and may give rise to the difficulties documented in the ethnographic research cited above. Furthermore, children who frequently change schools suffer academically (Engec, 2006; Mehana & Reynolds, 2004), and a cross-border move may be all the more disruptive.

Yet these students may also be among the privileged in Mexico. The New Economics of Labor Migration (Stark & Bloom, 1985) highlights how voluntary return migration can be evidence of economic success, with parents accumulating sufficient resources to lead a comfortable life in Mexico. Following Cassarino’s (2004) resource mobilization-preparedness framework, if children benefit from resource-rich social networks and parents who have achieved their goals in acquiring skills and capital while abroad, and if the family is ready and willing to move, they are more likely to be well supported upon return to the parents’ country of origin. Scholars suggest that at least some of these children benefit from resources such as dual nationality, bicultural facility, and experience in better resourced schools (Gándara & Jensen, 2021). Furthermore, in the absence of most social markers of difference, assimilation theory predicts that integration should be straightforward and rapid (Alba & Nee, 2003; Portes & Zhou, 1993). As Bybee et al. (2020) document, these U.S.-born children of return migrants may be “star students.”

Institutional Explanations

Individual resources or encumbrances may not be as important as the institutional context in which these children find themselves (Escoto & Masferrer, 2021; Woessmann, 2016). In recent years, scholars of immigrant incorporation have found that institutional features of national systems may be at least as important as individual factors in accounting for incorporation outcomes (Crul & Vermeulen, 2003; Midtbøen & Nadim, 2022; Platt et al., 2022; Schneider et al., 2022; Thomson & Crul, 2007). When schools are well resourced and give students many opportunities for “second chances,” immigrant-origin students tend to benefit (Dronkers & de Heus, 2016; Entorf & Lauk, 2008; Heath et al., 2008; Midtbøen & Nadim, 2022). If schools are not accommodating of students of different backgrounds, or if these students are concentrated in under-resourced schools, they tend to suffer (Borgna & Contini, 2014; Dronkers & Levels, 2007; Valenzuela, 1999). Institutional features may also affect different types of migrant-origin students in different ways (Crul et al., 2013; Crul, 2016).

Features of the Mexican education system suggest that children of return migrants may be especially ill-served. Although the U.S. education system has many weaknesses, the Mexican system has far fewer resources. In 2014, Mexico spent 2,000 USD per pupil, while the U.S. spent 18,000 USD (Santibañez, 2021, p. 25). The school day is short (4.5 h in elementary and 7 h in secondary school), few extracurricular or enrichment programs exist, and many teachers in Mexico must navigate hectic hours, shifting between schools and sets of students in the middle of the school day (Santibañez, 2021). There are also virtually no accommodations for children who are not fluent in Spanish, such as supplementary classes for Spanish learners (Despagne & Jacobo Suárez, 2019). All of these limitations are likely to lower student achievement.

Analytic Approach

For children of return migrants, how do we define “positive” or “negative” outcomes in school? One important consideration is accounting for immigrant selection (Feliciano, 2005; Feliciano & Lanuza, 2017). Selection can be incorporated into statistical models of children’s education in two ways. First, it can be directly included as a covariate measuring relative educational attainment, at either the group (Feliciano, 2005) or individual (Feliciano & Lanuza, 2017) level. Alternatively, the researcher can find a suitable comparison group that implicitly accounts for immigrant selection. For example, Hoffmann (2024) compares young Eastern European migrants in Western Europe to similar co-nationals who stayed behind in the East. This second approach has the benefit of accounting for more than measured educational selectivity: many skills are not captured by measures of formal education (Hagan et al., 2015), and immigrants are also selected in ways not related to skills. Further adjustment for observed individual differences can render the groups even more comparable.

This paper makes both types of comparisons. First, it places U.S.-born children of Mexican return migrants in the Mexican educational context by comparing them to local Mexican children without migration backgrounds, providing an estimate of the descriptive gap in achievement between locals and U.S.-born children of return migrants. This set of analyses follows the tradition of assimilation literature, showing how similar to locals these migrant children have become.

Second, this study compares these children to an illuminating group across the border. The target here is a causal estimand: the scores these children would have obtained in the U.S. had they not migrated to Mexico. Due to data limitations, this study is not able to identify children of Mexican immigrants in the U.S. Instead, this set of comparisons looks at children of Spanish-speaking immigrants. Although different from the ideal comparison group of children of Mexican immigrants in the U.S., this is arguably still a viable pseudo-control group. About two-thirds of the Hispanic population in the U.S. is of Mexican origin (Trevelyan et al., 2016, p. 12). Furthermore, previous studies show similar achievement among U.S.-born children of Spanish-speaking immigrants from a variety of origins. Using data from the Immigration and Intergenerational Mobility in Metropolitan Los Angeles (IIMMLA) survey and Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Study (CILS-III) for San Diego, Rumbaut (2008, p. 222) finds that the high-school grades of second-generation Mexican, Salvadoran, and Guatemalan students are very similar. Similarly, models by Glick and Hohmann-Marriott (2007) show that in the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, third-grade math scores for children of Mexican, Puerto Rican, and other Hispanic origins are indistinguishable.

Finally, this paper explicitly examines immigrant selection by comparing and incorporating attributes of parents of these children in Mexico and the U.S. By considering both the U.S. and Mexico, this paper employs a cross-border perspective (Waldinger, 2017) that sheds greater light on the process and outcomes of migration than a single-country analysis would.

Data and Methods

The target population for this study is Mexican migrants’ U.S.-born children who are enrolled in school in Mexico. Data come from the pooled 2009 and 2012 waves of PISA. These years are chosen for two reasons. First, these waves saw larger samples for Mexico (over 30,000 total in each year), while in 2015 and 2018 only about 7,500 Mexican students took the PISA test. In addition, these years included questions on Mexican region and family structure, while the later years did not. The Online Appendix shows results for a pooled sample that additionally includes PISA data for 2015 and 2018 and also presents results separately for these four survey years.

In Mexico it is not uncommon for non-migrant Mexican mothers to travel to the U.S. for the birth of their children, securing them U.S. citizenship (Vargas-Valle et al., 2022). To remove this group from the sample, I exclude children who migrated to Mexico before the age of one. (In some analyses below, I also exclude children who migrated before the age of six, and results are substantively unchanged.) As shown in Table 1, the sample of interest comprises 450 children in Mexico who were born in the U.S. to two Mexican-born parents. I compare these to 61,896 children born in Mexico to two Mexican-born parents as well as 631 children born to two immigrant parents in the U.S. who speak Spanish in the home.

Outcome variables consist of reading, math, and science scores, which the OECD constructs to have a global mean of 500 and standard deviation of 100. I use the five plausible values for reading, math, and science scores, combining estimates and calculating standard errors as suggested by the PISA Technical Reports.

I present three sets of estimates. The first are simple difference-in-means estimates, subtracting the average scores for U.S.-born children of return migrants from average scores for the Mexican and U.S. comparison samples. In the absence of selection into (return) migration, these estimates would be unbiased for the effect of being a child of return migrants. However, migrant families are likely selected. To help account for this, the next set of estimates uses OLS regressions that control for pre-return-migration variables. The final set of estimates also adjusts for post-migration variables that might mediate the relationship between migrating to Mexico and educational outcomes; if these variables are mediators, then effect estimates should be attenuated compared to other estimates. I also test the influence of the potential moderators of gender, rural/urban location, age at migration, and region by performing OLS regressions with pre-migration variables on subsets of the data. In all analyses, I cluster standard errors at the school level and incorporate sampling weights using the survey package in R (Lumley & Gao, 2024). Comparisons within Mexico use final student weights, while comparisons with the U.S. use senate weights that give equal weight to each country.

Pre-return-migration control variables include five continuous variables. First are mother’s and father’s education, measured in six-category International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED).Footnote 2 Next are two composite indices constructed by the OECD (see OECD, 2014, p. 312), which I standardize to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 within waves. Cultural possessions measures whether pupils have classical literature, books of poetry, and works of art in the home. For educational resources, respondents indicate whether their homes contain a desk to study at, a quiet place to study, a computer they can use for school work, educational software, books to help with school work, technical reference books, and a dictionary. I also control for age. Controls also include four categorical variables. One measures whether the child was enrolled in one year or less, more than one year, or no early childhood education and care (ECEC). I also control for survey year and two-category gender. Return migrants may also be selected by their region of origin. Although PISA does not ask where in Mexico respondents’ parents were born, it does include information on which Mexican state the respondent currently resides in. As a proxy for region of origin of parents, for models including the Mexican comparison sample I include a dichotomous variable for whether respondents live in the traditional migrant-sending regions of Aguascalientes, Colima, Durango, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Michoacán, Nayarit, San Luis Potosí, or Zacatecas (Denier & Masferrer, 2020).

Next, I consider post-migration variables as possible mediators. These include two composite variables constructed by the OECD that I standardize to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 within waves. Household wealth measures whether respondents have their own room, internet, a dishwasher, or a DVD player, and counts of cell phones, televisions, computers, cars, and rooms with a bath or shower. This variable also includes country-specific measures of wealth: for Mexico, these include cable TV, a phone line, and a microwave oven, and for the U.S. include a guest room, high-speed internet, and a musical instrument. An index of economic, social and cultural status relies on variables for wealth, home possessions, cultural possessions, books in the home, parental education, and parental occupation. I also include highest parental occupational status measured in the International Socio-Economic Index (Ganzeboom et al., 1992); a measure of family structure that includes categories for living with two parents, living with one parent, or living with no parents; and a dichotomous measure of urban locality, with one category for small and large cities and another for villages, small towns, and towns. Descriptive statistics for all of these variables are presented in Table 1, separately for each group.

Results

Comparisons within the Mexican Context

The first set of analyses compares children of return migrants to local children in Mexico. As shown in Table 1, although mean scores for all three groups are below the global average of 500, U.S.-born children in Mexico tend to score slightly higher than Mexican-born children. Scores for children of Spanish-speaking immigrants in the U.S. are higher still.

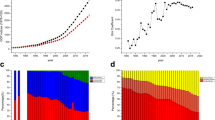

The top panel of Fig. 1 compares PISA scores of children of return migrants in Mexico to the local Mexican-born sample using difference-in-means (DIM) and ordinary least squares (OLS). (Coefficients for both OLS models are presented in the Online Appendix.) The error bars show 95-percent asymptotic confidence intervals. We first consider the DIM estimates, which subtract the average reading, math, or science scores for children of return migrants from the scores for the comparison group. Compared to other adolescents in Mexico, children of return migrants perform somewhat better in all three subjects. The difference amounts to 12 points in reading, 8.7 in math, and 13 in science. The advantage is statistically significant for all three subjects and amounts to about one-tenth of a standard deviation. The next set of estimates adjusts for pre-migration characteristics in a linear regression estimated by OLS; estimates barely change. Rather than struggling academically, The U.S.-born children of return migrants perform as well as or better than similar Mexican-born children. This provides partial support for these being “star students.”

Difference-in-means (DIM) and OLS estimates comparing children of return migrants in Mexico to children in Mexico and children of Spanish-speaking immigrants in the U.S. Error bars represent 95% asymptotic confidence intervals. OLS (pre-migration) models adjust for parents’ education, cultural possessions, home educational resources, age, ECEC, gender, survey year, and (for the Mexico sample) traditional migrant-sending region. OLS (post-migration) models additionally adjust for household wealth; an index of economic, social and cultural status; urban or non-urban locality; highest parental ISEI; and family structure. All models cluster standard errors at the school level and incorporate sampling weights. Data come from the 2009 and 2012 waves of PISA.

The third set of estimates, “OLS (pre- & post-migration),” includes possible post-migration mediators of the advantage possessed by members of this group. These include household wealth; an index of economic, social and cultural status; urban or non-urban locality; highest parental occupational status (in ISEI); and family structure. The academic advantaged enjoyed by children of return migrants does not shrink. These models suggest that material circumstances do not account for these children’s higher scores; binational experience and potentially unmeasured parental resources are likely at play here.

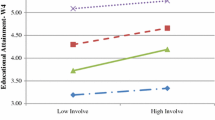

The next analyses consider possible moderators of these effects. How do results vary by gender, age at migration, rural or urban locality, or region? Generally, girls tend to surpass boys in school (Buchmann et al., 2008), and the advantage for immigrant girls may be even higher (Dronkers & Kornder, 2014). Thus we might expect daughters of return migrants to have an easier time adjusting to academic life in Mexico. Panel A of Fig. 2 shows that the proportions of U.S.-born girls and local Mexican samples are nearly identical. Does the academic performance of sons and daughters of return migrants differ? The first estimates in Fig. 3 show the difference between daughters of return migrants and Mexican-born girls, derived from OLS models with the same pre-migration control variables (except gender) and standard error procedures as for the full sample above. Corresponding estimates for boys follow. Surprisingly, estimates for boys are higher; while daughters of return migrants attain scores indistinguishable from Mexican girls, sons score one-fifth of a standard deviation higher than other boys.

Sample distributions of gender, school location, and age at arrival. The first two panels compare the U.S.-born children of return migrants to Mexican-born locals, while the third panel shows the distribution only for the former. All estimates incorporate sampling weights. Data come from the 2009 and 2012 waves of PISA.

Worldwide, PISA scores tend to be lower in rural areas (Echazarra & Radinger, 2019; Sullivan et al., 2018). Hamann and Zúñiga (2021) claim that children of return migrants in Mexico are more likely to live in rural areas, where relative paucity of resources may contribute to disadvantage. The right-hand set of estimates in Fig. 1 shows that including a measure of rurality does not change estimates of overall score disparities. But location could still moderate results. What proportion of the children in this sample live in rural areas, and how does achievement vary between rural and urban areas? PISA categorizes “school community” as village, small town, town, city, or large city.

Panel B of Fig. 2 partially corroborates Hamann and Zúñiga (2021): this group tends to live in somewhat less urban areas than the general population of Mexican children. For OLS models, I dichotomize this variable into non-urban (village, small town, and town) vs. urban (city or large city) areas. Figure 3 shows that score disparities do indeed vary by rurality, but in the opposite direction than expected. Children of return migrants in non-urban areas score one-fifth of a standard deviation higher than similar children in those same areas, while those in urban areas do not score significantly differently.

Moderators of the difference in PISA scores between U.S.-born children of return migrants and Mexican-born adolescents. All estimates come from OLS models that adjust for the controls specified in the data section, cluster standard errors at the school level, and incorporate sampling weights. Data come from the 2009 and 2012 waves of PISA.

Next I consider age at migration as a potential moderator. Although there is little work on academic achievement of children of return migrants, children who migrate at younger ages tend to score higher on achievement tests (Hermansen, 2017; Lemmermann & Riphahn, 2018). Furthermore, Despagne and Jacobo Suárez (2019) suggest that challenges faced by children of return migrants tends to fade with time. Are the results reported above due to a large proportion of children who migrated at a young age? On the other hand, age at migration may work in the opposite direction in this case, with more time in higher resourced U.S. schools leading to higher test scores. Do results differ between children who migrate before school age and those with some U.S. school experience? Panel C in Fig. 2 shows that the distribution of age at migration is skewed toward the younger years; 64% of the sample migrated to Mexico before the age of six. Figure 3 explores two possible divisions of arrival age, at six and ten years. According to the figure, these age cut-offs have only a small effect. Children who migrate at older ages have slightly higher point estimates, but these are not significantly different except for science: compared to children who migrate before the age of ten, those who migrate at ten or older score 13 points (about one-tenth of a standard deviation) higher on PISA science tests. Although the difference is not significant for the age six cutoff, it is still a positive estimate, at eight points. Hence additional time in U.S. schools may in fact give these children some small advantage on PISA tests.

Finally, results may vary by region in Mexico.Footnote 3 First, regions with a long history of migration may have better resources to reintegrate return migrants and their children (Denier & Masferrer, 2020). Although the main results do not change when I control for residence in the traditional migrant-sending states of Aguascalientes, Colima, Durango, Guanajuato, Jalisco, Michoacán, Nayarit, San Luis Potosí, or Zacatecas, results may still vary if I restrict the sample to these areas. However, as shown in Fig. 3, results within and outside of traditional migrant-sending regions are very similar; the migrant regions see slightly lower point estimates, but these are not significantly different from the rest of Mexico. Second, in the northern Mexican states along the U.S. border, binational life is more fluid, characterized by circular migration and even daily commutes between the U.S. and Mexico (Chávez, 2016; Panait & Zúñiga, 2016). In addition, children born in the U.S. to non-migrant Mexican mothers are more common in these states (Vargas-Valle et al., 2022); although I attempt to remove this group from the sample by excluding children who migrated to the U.S. before the age of one, some may remain. Hence I perform separate analyses for respondents living in the northern states of Baja California, Sonora, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Nuevo León, or Tamaulipas. Figure 3 shows that results are very similar for students inside and outside of these northern states. Regardless of region, children of return migrants in this sample tend to outperform Mexican-born children on PISA tests.

Comparisons to the U.S. Context

We now turn to comparisons between U.S.-born children of return migrants in Mexico and children of Spanish-speaking immigrants in the U.S. This pseudo-control group allows us to address the counterfactual question: what would have happened to these children had they not migrated to Mexico? Put another way, how much have they dissimilated (FitzGerald, 2012) from their counterparts in the U.S.? Descriptive statistics in Table 1 show that although this group achieves somewhat higher scores than their Mexican-born peers, the U.S. comparison group performs much higher.

The bottom panel of Fig. 1 presents the disparities. Unadjusted difference-in-means estimates show stark negative differences: -48 in reading, -31 in math, and − 33 in science. These amount to children of return migrants attaining math and science scores one-third of a standard deviation lower than their U.S. counterparts and reading scores one-half of a standard deviation lower. Despite their slight score advantage in Mexico, these children struggle on PISA exams much more than children of Spanish-speaking immigrants in the U.S. (Coefficients for both OLS models are presented in the Online Appendix.)

Are such large disparities due to selection into migration? Fig. 4 compares histograms of family attributes of the two samples. The top row shows two measures of pre-return characteristics. First, Panel A shows that children of return migrants are more likely to have been enrolled in early childhood education. Panel B compares parents’ highest years of education, showing that this group tends to have a parent with more years of education – 12 years compared to the comparison group’s 11 – and also more likely to have a parent with a college degree. While previous research shows negative selection in the general return migrant population (Campos-Vazquez & Lara, 2012), this group appears to be somewhat positively selected: they benefit from greater personal and family educational advantages than their counterparts who remain in the U.S.

Hence we would expect that controlling for pre-migration characteristics will not account for disparities in PISA scores. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 1, an OLS model that adjusts for these characteristics estimates slightly smaller gaps, but they remain for all three subjects.

Since selection into migration on these measured characteristics does not account for disparities, could the post-migration experience play a role? The second row of Fig. 4 presents two measures of post-migration attributes. Panel C shows a composite measure of family wealth. Despite their pre-migration advantages, children of return migrants enjoy fewer material assets than the U.S. comparison group. Finally, previous work has shown that family separation is a common part of return migration (Masferrer et al., 2019). However, as shown in Panel D, U.S.-born children of return migrants in this sample are only slightly less likely to live in a two-parent household than the U.S. comparison sample.

The right set of estimates in Fig. 1 adjusts for pre- and post-migration characteristics. Estimated disparities become even more negative, although they are not significantly different from the DIM estimates. This suggests that it is neither selection nor the post-migration material experience of children of return migrants that accounts for their lower achievement compared to the U.S. The lower resources of Mexican schools as well, the stress of adapting to an unfamiliar society, and unmeasured factors such as legal status of parents are a large part of the story here.

The final set of analyses examines factors that moderate the effect of migration. Figure 5 presents the same set of moderators as Fig. 3, fitting the “OLS (pre-migration)” model to subsets of the data. First, effects differ little by gender: girls and boys in this group achieve lower scores than daughters and sons of Spanish-speaking immigrants in the U.S., respectively. Although point estimates for girls are somewhat lower, differences between boys and girls are not statistically significant. The urban-rural divide shows no great differences, in contrast to the results for the Mexican comparison group.

Moderators of the difference in PISA scores between U.S.-born children of return migrants in Mexico and children of Spanish-speaking immigrants in the U.S. All estimates come from OLS models that adjust for the controls specified in the data section, cluster standard errors at the school level, and incorporate sampling weights. Data come from the 2009 and 2012 waves of PISA.

We also see little variation in effect by age at migration. Although point estimates are slightly higher for children who migrated at older ages, differences are not significantly different. If we restrict the analysis to children who migrated to Mexico below the age of six or ten, estimated disparities are just as negative as for children who migrated at older ages. The last moderators considered test variation by region. Again, results vary little across traditional migrant-sending regions, northern Mexican states, and the rest of Mexico.

Across all moderators, results change little, with negative point estimates that are statistically significant in nearly all cases. Although samples may be too small to detect fine-grained differences between subgroups, the overall story is clear: regardless of how we stratify the sample, children of return migrants in Mexican schools obtain lower PISA scores than children of Spanish-speaking immigrants in the U.S.

Sensitivity Analysis

Results may be sensitive to choice of estimation strategy or omission of a confounding variable. To assess the robustness of results, this section presents results from alternative estimation techniques. Figure 6 presents five types of estimates of the effect of being in a child of return migrants. The estimates labeled “OLS” reproduce the results for “OLS (pre-migration)” from Fig. 1, and the other estimates test the robustness of this baseline estimate. The next three sets of estimates use strategies from the MatchIt package (Ho et al., 2011). “PSM” and “Mahalanobis” present estimates 1:1 matching for propensity scores estimated from logistic regression (Rosenbaum & Rubin, 1983) and Mahalanobis distance, respectively. “Optimal Full” employs optimal full matching (Hansen & Klopfer, 2006), which places all units into subclasses in order to minimize the sum of absolute within-subclass distances. Finally, “IPW” uses stabilized inverse probability weights (Austin & Stuart, 2015, p. 3663), performing bivariate weighted OLS regressions with the full samples.

Alternate estimates comparing children of return migrants in Mexico to children in Mexico and children of Spanish-speaking immigrants in the U.S. Error bars represent 95% asymptotic confidence intervals. Models adjust for parents’ education, cultural possessions, home educational resources, age, ECEC, gender, survey year, and (for the Mexico sample) traditional migrant-sending region. OLS is the baseline model, PSM uses propensity score matching, matches on Mahalanobis distance, Optimal Full implements the matching algorithm from Hansen and Klopfer (2006), and IPW incorporates (stabilized) inverse probability weights. Data come from the 2009 and 2012 waves of PISA.

Estimates are fairly robust to choice of estimator. Across almost all specifications, the U.S.-born children of return migrants outperform Mexican-born locals, and they score lower across all subjects when compared to children of Spanish-speaking immigrants in the U.S.

The Online Appendix provides other tests of robustness. First, Section B assesses the sensitivity of results to omitted confounders. Important variables might be correlated with both immigration (and return migration) as well as test scores. For the Mexican comparison, results are already close to 0, so this analysis focuses on the U.S. comparison. How strong would an unobserved confounder need to be in order to create a null effect for migration to Mexico for U.S.-born children of return migrants? I use the sensemakr package (Cinelli & Hazlett, 2020) to help answer this question. Results are fairly robust to high levels of potential confounding; a confounder even ten times as strong as the joint effect of mother’s and father’s education would still not produce a nonsignificant coefficient.

Second, have results changed over time? Section C of the Online Appendix presents results for 2015 and 2018 waves of PISA in addition to 2009 and 2012, both pooled and separately by year. In pooled analyses using all four PISA waves, results are substantively similar to the 2009 and 2012 analyses, with U.S.-born children of return migrants outperforming Mexican-born children and performing worse than U.S.-born children. However, the math scores for this pooled sample are higher and the reading and science scores are lower, to the point where the latter are not significantly different from the Mexican control group. Separating results by survey year reveals why: in 2015, math scores for the migrant group were especially high, and in 2015 and 2018 scores tended lower. As the migration system has shifted, these children of return migrants are at increasing disadvantage relative to the U.S. comparison group, but their scores are indistinguishable from the Mexican group.

Discussion and Conclusion

This paper quantifies the educational situation of U.S.-born children of return migrants in Mexico. Previous research on this group has presented a mixed picture: Although these children face stigma, language difficulties, and bureaucratic hurdles (Despagne & Jacobo Suárez, 2019; Gándara, 2020; González et al., 2016; Mateos, 2019; Zúñiga, 2018), some scholars have documented the advantages bestowed by bicultural facility and time in relatively well resourced U.S. schools (Bybee et al., 2020; Hernández-León et al., 2020; Zúñiga & Giorguli Saucedo, 2018). To address this empirical question at the population level, this paper compares this group to both the broader population of Mexican 15-year-olds as well as children of Spanish-speaking immigrants in the U.S.

Comparisons with Mexican children reveal a slight advantage: U.S.-born children of return migrants outperform Mexican children on reading, math, and science PISA tests by about one-tenth of a standard deviation. Unlike the larger population of Mexican return migrants, parents of these adolescents are slightly positively selected on education. Controlling for pre- or post-return-migration family characteristics does little to change effect estimates. These results vary somewhat by subgroups; the advantage for boys is greater than that for girls, and the advantage in non-urban areas is higher than in urban areas. Age at migration only weakly moderates effects, with children migrating at age 10 or older performing better in science than those who migrate at younger ages; some time in better resourced U.S. schools may help these students perform better on PISA. There is little regional variation in results.

Comparisons with the U.S. sample, however, tell a story of disadvantage. Juxtaposed with this pseudo-control group, children of Mexican return migrants obtain much lower scores, ranging from one-third a standard deviation for math and science to one-half of a standard deviation for reading. Results also vary little by potential moderators. The large score differences with U.S. students echoes previous work that documents significant struggles in school for children of return migrants in Mexico. Although they perform close to the Mexican average, children who migrate after beginning school in the U.S. likely feel that they are struggling compared to the friends they left behind. The stress of moving to a new academic system may leave lasting impacts (Engec, 2006; Mehana & Reynolds, 2004). Furthermore, reading scores may be lower due to less time spent formally learning to read and write in Spanish (Despagne & Jacobo Suárez, 2019; González et al., 2016). These findings suggest that institutional context plays an important role in the incorporation process; these children assimilate to the relatively low educational average of Mexican schools, which receive far fewer resources than those in the U.S., have shorter school days, and provide little support for children who are not fluent in Spanish (Santibañez, 2021). However, these results may also arise from unmeasured characteristics of children and their families that may make them disadvantaged relative to their counterparts in the U.S.; for example, their parents may be more likely to have been undocumented or to have faced economic hardship in the U.S. (Landale et al., 2016).

At the same time, this group retains a small advantage – at least in math achievement – compared to Mexican-born students. This may result from a few factors. First, they may benefit from bicultural resources or prestige bestowed by experience in the U.S. (Bybee et al., 2020; Hernández-León et al., 2020; Zúñiga & Giorguli Saucedo, 2018). For U.S.-born students with experience in U.S. schools, facility with standardized tests (which are much more common in the U.S. than Mexico) may enable their success on PISA, regardless of actual learning. These children may also benefit from resources they or their families obtained during their time abroad (Clemens & Pritchett, 2008); the positive educational selection of their parents supports this conclusion. For children in the sample who came to Mexico at very young ages, the fact that their mothers were able to live in the U.S. at the time they gave birth may indicate greater family resources or other unmeasured advantages related to education. A more sobering possibility is that bureaucratic hurdles prevent the most disadvantaged students from enrolling in school (Mateos, 2019), or they have dropped out completely (Zúñiga & Carrillo Cantú, 2020); in either case they are excluded from the PISA sample. However, 2015 data suggest that U.S.-born young people in Mexico are not less likely to be enrolled in school than the Mexican-born (Amuedo-Dorantes & Juarez, 2022). Further research is needed to explore these possibilities.

This study suggests a number of future directions for research on children of return migrants in Mexico. First, this study has not been able to differentiate between voluntary and involuntary return migration. Hamilton et al. (2023) estimate that one in six U.S.-born children in Mexico are the children of recently deported parents. The threat of deportation has been shown to negatively impact student achievement (Gándara & Ee, 2021), and the lower scores in 2015 and 2018 shown in the Online Appendix coincide with increasing deportations from the U.S. Future work should attempt to differentiate the academic effects of different types of return. Second, previous studies of children of Mexican return migrants have often pooled together students born in the U.S. and those born in Mexico who migrate to the U.S. at an early age (Zúñiga, 2018; Zúñiga & Giorguli Saucedo, 2018; Zúñiga & Hamann, 2021). Although identifying the latter is not possible in PISA data, future research should assess the achievement of the Mexican-born group as well. Lastly, since PISA is administered to only 15-year-olds, we do not know if achievement varies by age at test time. Previous work has shown that disparities for children of immigrants may be greater at younger ages (Hoffmann, 2018; Strand et al., 2015), and educational parity at older ages may not translate to equality in the labor market (Lee, 2021, pp. 192–193). Future research should investigate achievement at younger ages as well as the school-to-work transition for this population.

This study constitutes an important corrective to literature on U.S.-born children of return migrants in Mexico. First, by showing that the educational situation of these students is one of slight advantage compared to other students in Mexico, this study suggests that previous studies have overstated the struggles these children face, or that efforts to ease these students’ transitions to Mexican schools may have born fruit (Zúñiga et al., 2008). Second, by considering two countries in cross-border perspective (Waldinger, 2017), this paper highlights the importance of institutional context in immigrant education. The U.S. comparisons presented here show that migration from more- to less-advantaged educational contexts can entail unfortunate consequences for children’s educational outcomes, especially in a national context that is hostile towards immigrants.

Data Availability

The PISA data underlying this article are available from the OECD, at https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/. Replication code in R is available from the author’s website.

Notes

Due to limitations of PISA data, the present study focuses only on U.S.-born children, rather than the original definition of the 0.5 generation that includes all children of return migrants regardless of birthplace.

Although some migrants may gain additional education after returning to Mexico, most do not. In the 2010 Mexican Census, only 1.6% of Mexican-born respondents who were living in the U.S. five years previously and who have their children in the household are enrolled in education (author’s calculations, Minnesota Population Center, 2023).

Although data on all Mexican states are available for 2009, due to participation less than 65% in 2012, data are not available for the Mexican states of Oaxaca, Michoacán, or Sonora in that year (INEE, 2013, p. 3).

References

Alba, R., & Nee, V. (2003). Remaking the American mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration. Harvard University Press.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C., & Juarez, L. (2022). Health Care and Education Access of transnational children in Mexico. Demography, 59(2), 511–533. https://doi.org/10.1215/00703370-9741101

Austin, P. C., & Stuart, E. A. (2015). Moving towards best practice when using inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using the propensity score to estimate causal treatment effects in observational studies. Statistics in Medicine, 34(28), 3661–3679. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.6607

Basch, L. G., Schiller, G., N., & Szanton Blanc, C. (1994). Nations unbound: Transnational projects, postcolonial predicaments, and deterritorialized nation-states. Gordon and Breach.

Borgna, C., & Contini, D. (2014). Migrant achievement penalties in Western Europe: Do Educational systems Matter? European Sociological Review, 30(5), 670–683. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcu067

Buchmann, C., DiPrete, T. A., & McDaniel, A. (2008). Gender inequalities in Education. Annual Review of Sociology, 34(1), 319–337. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134719

Bybee, E. R., Whiting, E. F., Jensen, B., Savage, V., Baker, A., & Holdaway, E. (2020). Estamos aquí pero no soy de aqui: American Mexican Youth, Belonging and Schooling in Rural, Central Mexico. Anthropology & Education Quarterly, 51(2), 123–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/aeq.12333

Campos-Vazquez, R. M., & Lara, J. (2012). Self-selection patterns among return migrants: Mexico 1990–2010. IZA Journal of Migration, 1(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.1186/2193-9039-1-8

Cassarino, J. P. (2004). Theorising Return Migration: The conceptual Approach to Return migrants Revisited. International Journal on Multicultural Societies, 6(2), 253–279.

Chávez, S. (2016). Border Lives: Fronterizos, Transnational Migrants, and Commuters in Tijuana (1st edition). Oxford University Press.

Cinelli, C., & Hazlett, C. (2020). Making sense of sensitivity: Extending omitted variable bias. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Statistical Methodology), 82(1), 39–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/rssb.12348

Clemens, M. A., & Pritchett, L. (2008). Income per Natural: Measuring Development for people Rather Than places. Population and Development Review, 34(3), 395–434. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2008.00230.x

Crul, M. (2016). Super-diversity vs. assimilation: How complex diversity in majority–minority cities challenges the assumptions of assimilation. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 42(1), 54–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1061425

Crul, M., & Vermeulen, H. (2003). The second generation in Europe. International Migration Review, 37(4), 965–986. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2003.tb00166.x

Crul, M., Schneider, J., & Lelie, F. (2013). Super-diversity. A new perspective on integration. VU University.

Denier, N., & Masferrer, C. (2020). Returning to a New Mexican Labor Market? Regional Variation in the Economic Incorporation of Return migrants from the U.S. to Mexico. Population Research and Policy Review, 39(4), 617–641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-019-09547-w

Despagne, C., & Jacobo Suárez, M. (2019). The adaptation path of transnational students in Mexico: Linguistic and identity challenges in Mexican schools. Latino Studies, 17(4), 428–447. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41276-019-00207-w

Diaz, C. J., Koning, S. M., & Martinez-Donate, A. P. (2016). Moving Beyond Salmon Bias: Mexican Return Migration and Health Selection. Demography, 53(6), 2005–2030. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0526-2

Downey, D. B., von Hippel, P. T., & Broh, B. A. (2004). Are schools the great equalizer? Cognitive inequality during the summer months and the School Year. American Sociological Review, 69(5), 613–635. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240406900501

Dronkers, J., & de Heus, M. (2016). The educational performance of children of immigrants in sixteen OECD countries. Adjusting to a World in Motion: Trends in Global Migration and Migration Policy, 264–290.

Dronkers, J., & Kornder, N. (2014). Do migrant girls perform better than migrant boys? Deviant gender differences between the reading scores of 15-year-old children of migrants compared to native pupils. Educational Research and Evaluation, 20(1), 44–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2013.874298

Dronkers, J., & Levels, M. (2007). Do School Segregation and School resources explain region-of-origin differences in the mathematics achievement of immigrant students? Educational Research and Evaluation, 13(5), 435–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803610701743047

Durand, J., & Massey, D. S. (2019). Evolution of the Mexico-U.S. Migration System: Insights from the Mexican Migration Project. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 684(1), 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716219857667

Echazarra, A., & Radinger, T. (2019). Learning in rural schools: Insights from PISA, TALIS and the literature. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/8b1a5cb9-en

Engec, N. (2006). Relationship between mobility and student performance and behavior. The Journal of Educational Research, 99(3), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.3.167-178

Entorf, H., & Lauk, M. (2008). Peer effects, Social multipliers and migrants at School: An International Comparison. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 34(4), 633–654. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830801961639

Entwisle, D. R., & Alexander, K. L. (1992). Summer setback: Race, poverty, School Composition, and Mathematics Achievement in the first two years of School. American Sociological Review, 57(1), 72–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096145

Escoto, A., & Masferrer, C. (2021). Integration into the Educational System and the Job Market among Young migrants in Mexico. In A. Vila-Freyer, & L. Meza-González (Eds.), Young migrants crossing multiple Borders to the North (Vol. 36, pp. 211–233). Transnational.

Feliciano, C. (2005). Does selective Migration Matter? Explaining ethnic disparities in Educational Attainment among immigrants’ children. International Migration Review, 39(4), 841–871. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2005.tb00291.x

Feliciano, C., & Lanuza, Y. R. (2017). An immigrant Paradox? Contextual attainment and intergenerational Educational mobility. American Sociological Review, 82(1), 211–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122416684777

FitzGerald, D. (2012). A comparativist manifesto for international migration studies. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 35(10), 1725–1740. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2012.659269

Gándara, P. (2020). The students we share: Falling through the cracks on both sides of the US-Mexico border. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 43(1), 38–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2019.1667514

Gándara, P., & Ee, J. (Eds.). (2021). Schools under siege: The impact of Immigration Enforcement on Educational Equity. Harvard Education.

Gándara, P., & Jensen, B. (Eds.). (2021). The students we share: Preparing US and Mexican educators for our transnational future. SUNY.

Ganzeboom, H. B. G., De Graaf, P. M., & Treiman, D. J. (1992). A standard international socio-economic index of occupational status. Social Science Research, 21(1), 1–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/0049-089X(92)90017-B

Glick, J. E., & Hohmann-Marriott, B. (2007). Academic performance of Young children in immigrant families: The significance of race, ethnicity, and National origins. International Migration Review, 41(2), 371–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2007.00072.x

González, B. R., Cantú, E. C., & Hernández-León, R. (2016). Moving to the homeland: Children’s narratives of Migration from the United States to Mexico. Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, 32(2), 252–275. https://doi.org/10.1525/mex.2016.32.2.252

Gonzalez-Barrera, A. (2015). More Mexicans Leaving Than Coming to the U.S. In Pew Research Center’s Hispanic Trends Project.

Gonzalez-Barrera, A. (2021). Before COVID-19, more Mexicans came to the U.S. Than left for Mexico for the first time in years. In Pew Research Center.

Hagan, J. M., & Wassink, J. T. (2020). Return Migration around the World: An Integrated Agenda for Future Research. Annual Review of Sociology, 46(1), 533–552. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-120319-015855

Hagan, J., Hernández-León, R., & Demonsant, J. L. (2015). Skills of the Unskilled: Work and Mobility among Mexican Migrants (First edition). University of California Press.

Hamann, E. T., & Zúñiga, V. (2021). What educators in Mexico and in the U.S. need to know and acknowledge to attend to the Educational needs of transnational students. In P. Gándara, & B. Jensen (Eds.), The students we share: Preparing US and Mexican educators for our transnational future (pp. 99–118). SUNY.

Hamilton, E. R., Masferrer, C., & Langer, P. (2023). U.S. Citizen Children De Facto Deported to Mexico. Population and Development Review, 49(1), 175–203. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12521

Hansen, B. B., & Klopfer, S. O. (2006). Optimal full matching and related designs via Network flows. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 15(3), 609–627. https://doi.org/10.1198/106186006X137047

Heath, A. F., Rothon, C., & Kilpi, E. (2008). The second generation in Western Europe: Education, unemployment, and Occupational Attainment. Annual Review of Sociology, 34(1), 211–235. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134728

Hermansen, A. S. (2017). Age at arrival and life chances among childhood immigrants. Demography, 54(1), 201–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0535-1

Hernández-León, R., Zúñiga, V., & Lakhani, S. M. (2020). An imperfect realignment: The movement of children of immigrants and their families from the United States to Mexico. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 43(1), 80–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2019.1667508

Ho, D. E., Imai, K., King, G., & Stuart, E. A. (2011). MatchIt: Nonparametric preprocessing for Parametric Causal Inference. Journal of Statistical Software, 42(8). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v042.i08

Hoffmann, N. I. (2018). Cognitive achievement of children of immigrants: Evidence from the Millennium Cohort Study and the 1970 British Cohort Study. British Educational Research Journal, 44(6), 1005–1028. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3476

Hoffmann, N. I. (2024). A win-win exercise? The effect of westward migration on educational outcomes of eastern European children. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 50(4), 891–913. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2022.2087057

INEE. (2013). México en PISA 2012: Resumen ejecutivo. Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación.

Jacobo Suárez, M., & Cárdenas Alaminos, N. (2019). Open-Door Policy? Reintegration Challenges and Government Responses to Return Migration in Mexico. In A. E. Feldmann, X. Bada, & S. Schütze (Eds.), New Migration Patterns in the Americas: Challenges for the 21st Century (pp. 111–140). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89384-6_5

Landale, N. S., Oropesa, R. S., Noah, A. J., & Hillemeier, M. M. (2016). Early cognitive skills of mexican-origin children: The roles of parental nativity and legal status. Social Science Research, 58, 198–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2016.02.004

Lee, J. (2021). Asian americans, Affirmative Action & the rise in Anti-asian hate. Daedalus, 150(2), 180–198. https://doi.org/10.1162/daed_a_01854

Lemmermann, D., & Riphahn, R. T. (2018). The causal effect of age at migration on youth educational attainment. Economics of Education Review, 63, 78–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2017.11.001

Lumley, T., & Gao, P. (2024). Survey: Analysis of Complex Survey Samples.

Masferrer, C. (2021). Return, Deportation, and Immigration to Mexico. In C. Masferrer & L. Pedroza (Eds.), The Intersection of Foreign Policy and Migration Policy in Mexico Today (pp. 37–46). El Colegio de México.

Masferrer, C., Hamilton, E. R., & Denier, N. (2019). Immigrants in their parental homeland: Half a million U.S.-born minors settle throughout Mexico. Demography, 56(4), 1453–1461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00788-0

Mateos, P. (2019). The mestizo nation unbound: Dual citizenship of Euro-mexicans and U.S.-Mexicans. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 45(6), 917–938. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1440487

Mehana, M., & Reynolds, A. J. (2004). School mobility and achievement: A meta-analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 26(1), 93–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2003.11.004

Meyers, S. V. (2014). Outsiders in two countries: School tensions in the lives of Mexican migrant youth. Latino Studies, 12(2), 217–236. https://doi.org/10.1057/lst.2014.22

Midtbøen, A. H., & Nadim, M. (2022). Navigating to the top in an egalitarian Welfare State: Institutional opportunity structures of second-generation social mobility. International Migration Review, 56(1), 97–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/01979183211014829

Minnesota Population Center (2023). Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, International: Version 7.4. IPUMS. https://doi.org/10.18128/D020.V7.4. [dataset].

OECD (2014). PISA 2012 Technical Report. OECD.

Panait, C., & Zúñiga, V. (2016). Children circulating between the U.S. and Mexico: Fractured schooling and linguistic ruptures. Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, 32(2), 226–251. https://doi.org/10.1525/mex.2016.32.2.226

Parrado, E. A., & Gutierrez, E. Y. (2016). The changing nature of Return Migration to Mexico, 1990–2010: Implications for Labor Market Incorporation and Development. Sociology of Development, 2(2), 93–118. https://doi.org/10.1525/sod.2016.2.2.93

Platt, L., Polavieja, J., & Radl, J. (2022). Which integration policies work? The heterogeneous impact of National Institutions on immigrants’ Labor Market Attainment in Europe. International Migration Review, 56(2), 344–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/01979183211032677

Portes, A., & Rumbaut, R. G. (2001). Legacies: The story of the immigrant second generation. University of California Press.

Portes, A., & Zhou, M. (1993). The New Second Generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 530, 74–96. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1047678

Portes, A., Guarnizo, L. E., & Landolt, P. (1999). The study of transnationalism: Pitfalls and promise of an emergent research field. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 22(2), 217–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/014198799329468

Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/70.1.41

Rumbaut, R. G. (2008). The coming of the second generation: Immigration and ethnic mobility in Southern California. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 620(1), 196–236. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716208322957

Sánchez García, J., & Hamann, E. T. (2016). Educator responses to migrant children in Mexican schools. Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, 32(2), 199–225. https://doi.org/10.1525/mex.2016.32.2.199

Santibañez, L. (2021). Contrasting realities: How differences between the Mexican and U.S. Education Systems affect transnational students. In P. Gándara, & B. Jensen (Eds.), The students we share: Preparing US and Mexican educators for our transnational future (pp. 17–44). SUNY.

Schleicher, A. (2019). PISA 2018: Insights and interpretations. OECD.

Schneider, J., Crul, M., & Pott, A. (Eds.). (2022). New Social mobility: Second Generation pioneers in Europe. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-05566-9

Silver, A. M. (2018). Displaced at home: 1.5-Generation immigrants navigating membership after returning to Mexico. Ethnicities, 18(2), 208–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796817752560

Stark, O., & Bloom, D. E. (1985). The New Economics of Labor Migration. The American Economic Review, 75(2), 173–178. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1805591

Strand, S., Malmberg, L., & Hall, J. (2015). English as an additional Language (EAL) and educational achievement in England: An analysis of the National Pupil Database. University of Oxford Department of Education.

Sullivan, K., McConney, A., & Perry, L. B. (2018). A comparison of rural Educational disadvantage in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand using OECD’s PISA. SAGE Open, 8(4), 2158244018805791. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018805791

Thomson, M., & Crul, M. (2007). The second generation in Europe and the United States: How is the transatlantic debate relevant for further research on the european Second Generation? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 33(7), 1025–1041. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691830701541556

Todaro, M. (1980). Internal migration in developing countries: A survey. Population and economic change in developing countries (pp. 361–402). University of Chicago Press.

Trevelyan, E., Gambino, C., Gryn, T., Larsen, L., Acosta, Y., Grieco, E., Harris, D., & Walters, N. (2016). Characteristics of the U.S. Population by Generational Status: 2013. U.S. Census Bureau. (Working {{Paper}} No. P23-214.

Valenzuela, A. (1999). Subtractive schooling: U.S.-Mexican Youth and the politics of Caring. State University of New York.

Vargas-Valle, E. D., Glick, J. E., & Orraca-Romano, P. P. (2022). US Citizenship for our Mexican children! US-born children of non-migrant mothers in Northern Mexico. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 0(0), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2022.2076253

Waldinger, R. (2017). A cross-border perspective on migration: Beyond the assimilation/transnationalism debate. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1238863

Waldinger, R. (2021). After the transnational turn: Looking across borders to see the hard face of the nation-state. International Migration, n/a(n/a). https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12868

Warren, R. (2020). Reverse Migration to Mexico Led to US Undocumented Population decline: 2010 to 2018. Journal on Migration and Human Security, 8(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/2331502420906125

Woessmann, L. (2016). The Importance of School Systems: Evidence from International differences in Student Achievement. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 30(3), 3–32. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.30.3.3

Zúñiga, V. (2018). The 0.5 generation: What children know about International Migration. Migraciones Internacionales, 9(3), 92–120.

Zúñiga, V., & Carrillo Cantú, E. (2020). Migración Y exclusión Escolar: Truncamiento de la educación básica en menores migrantes de Estados Unidos a México. Estudios Sociológicos De El Colegio De México, 38(114). https://doi.org/10.24201/es.2020v38n114.1907

Zúñiga, V., & Giorguli Saucedo, S. E. (2018). Niñas y niños en la migración de Estados Unidos a México: La generación 0.5. El Colegio de México.

Zúñiga, V., & Hamann, E. T. (2021). Children’s voices about return migration from the United States to Mexico: The 0.5 generation. Children’s Geographies, 19(1), 88–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2020.1743818

Zúñiga, V., Hamann, E. T., & Sánchez García, J. (2008). Alumnos transnacionales: Las Escuelas Mexicanas Frente A La Globalización. Secretaría de Educación Pública.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Roger Waldinger, Andrés Villarreal, Jennie Brand, Chad Hazlett, members of UCLA’s Migration Working Group, and participants at the 2022 Population Association of America and the American Sociological Association annual meetings for their helpful feedback on previous versions of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hoffmann, N.I. Strangers in the Homeland? The Academic Performance of U.S.-Born Children of Return Migrants in Mexico. Popul Res Policy Rev 43, 40 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-024-09886-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-024-09886-3