Abstract

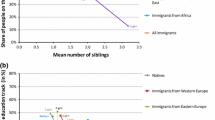

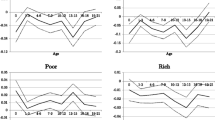

This study examines the causal relationship between childhood immigrants’ age at arrival and their life chances as adults. I analyze panel data on siblings from Norwegian administrative registries, which enables me to disentangle the effect of age at arrival on adult socioeconomic outcomes from all fixed family-level conditions and endowments shared by siblings. Results from sibling fixed-effects models reveal a progressively stronger adverse influence of immigration at later stages of childhood on completed education, employment, adult earnings, occupational attainment, and social welfare assistance. The persistence of these relationships within families indicates that experiences related to the timing of childhood immigration have causal effects on later-life outcomes. These age-at-arrival effects are considerably stronger among children who arrive from geographically distant and economically less-developed origin regions than among children originating from developed countries. The age-at-arrival effects vary less by parental education and child gender. On the whole, the findings indicate that childhood immigration after an early-life formative period tends to constrain later human capital formation and economic opportunities over the life course.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The senstive period of language acquisition appears to primarily affect the formal aspects of language, such as phonology, morphology, and syntax, but not the processing of meaning, such as aqcuisition of vocabulary and semantic understanding (Newport 2002).

Identification of language-related effects of age at arrival rests on the assumption that all other age-at-arrival effects (i.e., those not related to language acquisition) are shared by children arriving in the host society (i.e., the United States and Australia) from Anglophone and non-Anglophone origin countries.

Prior to 1970, immigration to Norway primarily consisted of citizens from the Nordic countries and other Western Europeans who came to seek work or who immigrated because of family connections.

Norwegian registry-based data on year of arrival are based on the first registered stay in official statistics, whereas census or survey data used in similar studies from Australia, Canada, and the United States often rely on self-reported information by immigrants on when they first arrived, arrived for the current stay, or simply arrived (Redstone and Massey 2003).

For the calculation of stable employment, the basic amount is doubled and would equal approximately U.S. $18,200.

This information is available only from 2003. From this year onward, I use information on all annual observations when the child is 30 years or older.

Because of few observations, the South American and African origin regions were merged.

Full regression estimates for the full sample are available upon request.

These calculations use the exp(β) – 1 formula. Note also that for the analysis of log earnings conditional on employment, the sibling sample is further limited to persons in families where at least two siblings were above the employment cutoff.

The main effects of origin region and parental education will be absorbed by the sibling fixed effects.

References

Akresh, I. R., & Frank, R. (2008). Health selection among new immigrants. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 2058–2064.

Åslund, O., Böhlmark, A., & Skans, O. N. (2015). Childhood and family experiences and the social integration of young migrants. Labour Economics, 35, 135–144.

Beck, A., Corak, M., & Tienda, M. (2012). Age at immigration and the adult attainments of child migrants to the United States. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 643, 134–159.

Berry, J. W., Phinney, J. S., Sam, D. L., & Vedder, P. (2006). Immigrant youth: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 55, 303–332.

Birdsong, D. (2006). Age and second language acquisition and processing: A selective overview. Language Learning, 56, 9–49.

Bleakley, H., & Chin, A. (2004). Language skills and earnings: Evidence from childhood immigrants. Review of Economics and Statistics, 86, 481–496.

Bleakley, H., & Chin, A. (2010). Age at arrival, English proficiency, and social assimilation among US immigrants. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2, 165–192.

Böhlmark, A. (2008). Age at immigration and school performance: A siblings analysis using Swedish register data. Labour Economics, 15, 1366–1387.

Böhlmark, A. (2009). Integration of childhood immigrants in the short and long run: Swedish evidence. International Migration Review, 43, 387–409.

Bradshaw, J., & Richardson, D. (2009). An index of child well-being in Europe. Child Indicators Research, 2, 319–351.

Bratsberg, B., Raaum, O., & Røed, K. (2010). When minority labor migrants meet the welfare state. Journal of Labor Economics, 28, 633–676.

Bratsberg, B., Raaum, O., & Røed, K. (2012). Educating children of immigrants: Closing the gap in Norwegian schools. Nordic Economic Policy Review, 3, 211–251.

Bratsberg, B., Raaum, O., & Røed, K. (2014). Immigrants, labour market performance and social insurance. Economic Journal, 124, F644–F683.

Bratsberg, B., & Ragan, J. F., Jr. (2002). The impact of host-country schooling on earnings: A study of male immigrants in the United States. Journal of Human Resources, 37, 63–105.

Brochmann, G., & Kjeldstadli, K. (2008). A history of immigration: The case of Norway, 900–2000. Oslo, Norway: Universitetsforlaget.

Chiswick, B. R., & DebBurman, N. (2004). Educational attainment: Analysis by immigrant generation. Economics of Education Review, 23, 361–379.

Chiswick, B. R., & Miller, P. W. (1992). Language in the labor market: The immigrant experience in Canada and the United States. In B. Chiswick (Ed.), Immigration, language and ethnic issues: Canada and the United States (pp. 229–296). Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute.

Cobb-Clark, D. A., Sinning, M., & Stillman, S. (2012). Migrant youths’ educational achievement: The role of institutions. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 643, 18–45.

Coll, C. G., & Magnuson, K. (1997). The psychological experience of immigration: A developmental perspective. In A. Booth, A. C. Crouter, & N. S. Landale (Eds.), Immigration and the family (pp. 91–131). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Corak, M. (2012). Age at immigration and the education outcomes of children. In A. S. Masten, K. Liebkind, & D. J. Hernandez (Eds.), Realizing the potential of immigrant youth (pp. 90–114). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Cunha, F., Heckman, J. J., Lochner, L., & Masterov, D. V. (2006). Interpreting the evidence on life cycle skill formation. In E. Hanushek & F. Welch (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of education (Vol. 1, pp. 697–812). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier.

Dustmann, C., & Frattini, T. (2013). Immigration: The European experience. In D. Card & S. Raphael (Eds.), Immigration, poverty, and socioeconomic inequality (pp. 423–456). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Dustmann, C., & Soest, A. V. (2002). Language and the earnings of immigrants. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 55, 473–492.

Eccles, J. S., Midgley, C., Wigfield, A., Buchanan, C. M., Reuman, D., Flanagan, C., & Mac Iver, D. (1993). Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents' experiences in schools and in families. American Psychologist, 48, 90–101.

Elder, G. H., Jr. (1998). The life course as developmental theory. Child Development, 69, 1–12.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. London, UK: Faber & Faber.

Erikson, R., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (1992). The constant flux: A study of class mobility in industrial societies. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1999). Social foundations of postindustrial economies. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Feliciano, C. (2005). Educational selectivity in U.S. immigration: How do immigrants compare to those left behind? Demography, 42, 131–152.

Fleischmann, F., & Kristen, C. (with contributions from Heath, A. F., Brinbaum, Y., Deboosere, P., Granato, N., ... van de Werfhorst, H. G.). (2014). Gender inequalities in the education of the second generation in Western countries. Sociology of Education, 87, 143–170.

Friedberg, R. M. (2000). You can’t take it with you? Immigrant assimilation and the portability of human capital. Journal of Labor Economics, 18, 221–251.

Fuligni, A. (2001). A comparative longitudinal approach to acculturation among children from immigrant families. Harvard Educational Review, 71, 566–579.

Galloway, T. A., Gustafsson, B., Pedersen, P. J., & Österberg, T. (2015). Immigrant child poverty—The achilles heel of the Scandinavian welfare state. In T. I. Garner & K. S. Short (Eds.), Measurement of poverty, deprivation, and economic mobility (pp. 185–219). Bingley, UK; Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Gonzalez, A. (2003). The education and wages of immigrant children: The impact of age at arrival. Economics of Education Review, 22, 203–212.

Grant, M. J., & Behrman, J. R. (2010). Gender gaps in educational attainment in less developed countries. Population and Development Review, 36, 71–89.

Guven, C., & Islam, A. (2015). Age at migration, language proficiency, and socioeconomic outcomes: Evidence from Australia. Demography, 52, 513–542.

Hakuta, K., Bialystok, E., & Wiley, E. (2003). Critical evidence: A test of the critical-period hypothesis for second-language acquisition. Psychological Science, 14, 31–38.

Heath, A. F., & Kilpi-Jakonen, E. (2012). Immigrant children’s age at arrival and assessment results (OECD Education Working Paper No. 75). Paris, France: OECD.

Hermansen, A. S. (2016). Moving up or falling behind? Intergenerational socioeconomic transmission among children of immigrants in Norway. European Sociological Review, 32, 675–689.

Knudsen, E. I., Heckman, J. J., Cameron, J. L., & Shonkoff, J. P. (2006). Economic, neurobiological, and behavioral perspectives on building America’s future workforce. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103, 10155–10162.

Kossoudji, S. A. (1988). English language ability and the labor market opportunities of Hispanic and East Asian immigrant men. Journal of Labor Economics, 6, 205–228.

Lee, S. M., & Edmonston, B. (2011). Age-at-arrival’s effects on Asian immigrants’ socioeconomic outcomes in Canada and the U.S. International Migration Review, 45, 527–561.

Lenneberg, E. H. (1967). Biological foundation of language. New York, NY: Wiley.

Lessard-Phillips, L., Fleischmann, F., & Van Elsas, E. (2014). Ethnic minorities in ten Western countries: Migration flows, policies and institutional differences. In A. Heath & Y. Brinbaum (Eds.), Unequal attainments (pp. 25–61). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Marsh, L. C., & Cormier, D. R. (2002). Spline regression models. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Massey, D. S., Arango, J., Hugo, G., Kouaouci, A., Pellegrino, A., & Taylor, J. E. (1993). Theories of international migration: A review and appraisal. Population and Development Review, 19, 431–466.

Mayer, K. U. (2009). New directions in life course research. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 413–433.

McKenzie, D. J. (2008). A profile of the world’s young developing country international migrants. Population and Development Review, 34, 115–135.

McManus, W., Gould, W., & Welch, F. (1983). Earnings of Hispanic men: The role of English language proficiency. Journal of Labor Economics, 1, 101–130.

Myers, D., Gao, X., & Emeka, A. (2009). The gradient of immigrant age-at-arrival effects on socioeconomic outcomes in the U.S. International Migration Review, 43, 205–229.

Newport, E. L. (2002). Critical periods in language development. In L. Nadel (Ed.), Encyclopedia of cognitive science (pp. 737–740). London, UK: MacMillan Publishing Ltd./Nature Publishing Group.

OECD. (2008). Growing unequal? Income distribution and poverty in OECD countries (Report). Paris, France: OECD.

OECD. (2015). International migration outlook (Report). Paris, France: OECD.

Oropesa, R. S., & Landale, N. S. (1997). In search of the new second generation: Alternative strategies for identifying second generation children and understanding their acquisition of English. Sociological Perspectives, 40, 429–455.

Oropesa, R. S., & Landale, N. S. (2009). Why do immigrant youths who never enroll in U.S. schools matter? School enrollment among Mexicans and non-Hispanic whites. Sociology of Education, 82, 240–266.

Penfield, W., & Roberts, L. (1959). Speech and brain mechanisms. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Phinney, J. S. (1990). Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of research. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 499–514.

Piore, M. J. (1979). Birds of passage: Migrant labor and industrial societies. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Portes, A., & Rumbaut, R. G. (2001). Legacies: The story of the immigrant second generation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Redstone, I., & Massey, D. S. (2003). Coming to stay: An analysis of the U.S. census question on immigrants’ year of arrival. Demography, 41, 721–738.

Rumbaut, R. G. (1994). The crucible within: Ethnic identity, self-esteem, and segmented assimilation among children of immigrants. International Migration Review, 28, 748–794.

Rumbaut, R. G. (2004). Ages, life stages, and generational cohorts: Decomposing the immigrant first and second generations in the United States. International Migration Review, 38, 1160–1205.

Schaafsma, J., & Sweetman, A. (2001). Immigrant earnings: Age at immigration matters. Canadian Journal of Economics, 34, 1066–1099.

Shonkoff, J. P., & Phillips, D. A. (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Söhn, J. (2011). Immigrants’ educational attainment: A closer look at the age-at-migration effect. In M. Wingens, M. Windzio, H. de Valk, & C. Aybek (Eds.), A life-course perspective on migration and integration (pp. 27–54). New York, NY: Springer.

Statistics Norway. (1998). Standard classification of occupations. Oslo/Kongsvinger: Statistics Norway.

Statistics Norway. (2001). Norwegian standard classification of education (Revised 2000). Oslo/Kongsvinger: Statistics Norway.

Statistics Norway. (2016). Immigrants and Norwegian-born to immigrant parents, January 1, 2016. Oslo/Kongsvinger: Statistics Norway. Retrieved from http://ssb.no/en/befolkning/statistikker/innvbef

Steinberg, L., & Silverberg, S. B. (1986). The vicissitudes of autonomy in early adolescence. Child Development, 57, 841–851.

Suarez-Orozco, M. M., & Suárez-Orozco, C. (2001). Children of immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Tainer, E. (1988). English language proficiency and the determination of earnings among foreign-born men. Journal of Human Resources, 23, 108–122.

UNDP. (2011). Human development report 2011 (HDR Report). New York, NY: UNDP.

UNICEF. (2016). Fairness for children: A league table of inequality in child well-being in rich countries (Innocenti Report Card 13). Florence, Italy: UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti.

United Nations. (2012). The age and sex of migrants 2011 wallchart [Data file]. New York, NY: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Available at http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/migration/age-sex-migrants-2011.shtml

Van Ours, J. C., & Veenman, J. (2006). Age at immigration and educational attainment of young immigrants. Economics Letters, 90, 310–316.

Wang, C., & Wang, L. (2011). Language skills and the earnings distribution among child immigrants. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 50, 297–322.

Wils, A., & Goujon, A. (1998). Diffusion of education in six world regions, 1960–90. Population and Development Review, 24, 357–368.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Acknowledgments

Early versions of this article were presented at the 2013 Annual Meeting of Population Association of America in New Orleans, Statistics Norway, Stockholm University, and University of Oslo. I thank the participants at these events for their comments. I also thank Arne Mastekaasa, Torkild Hovde Lyngstad, Irena Kogan, and Anthony Heath for helpful advice and suggestions. Funding for this research was provided by the Norwegian Research Council (Grant Nos. 158058 and 236793). This research used data from Norwegian administrative registries collected by Statistics Norway.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hermansen, A.S. Age at Arrival and Life Chances Among Childhood Immigrants. Demography 54, 201–229 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0535-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-016-0535-1