Abstract

The personalization thesis claims that leaders’ influence over voters has increased. While research consistently shows that candidates influence party choice, we know little about their effects on the prior decision to turn out in elections. This article represents the first study to examine the relationship between candidate trait evaluations and turnout decisions in the American context and the first longitudinal study of the phenomenon. The study utilizes ANES data to test three hypotheses drawn from theories on electoral participation and personalized politics in U.S. presidential elections between 1980 and 2020. The results show that while trait evaluations of Republican candidates consistently affect turnout, perceptions of Democratic candidates’ competence mobilize voters in specific elections. Moreover, individual polarization promotes turnout, particularly among partisan dealigned voters with different perceptions of the candidates’ competence. The results indicate a personalization of electoral participation that can benefit civic engagement and democratic quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although studies of voting behavior repeatedly explore the impact of personalized politics, we know little about individual candidates’ capacity to mobilize people to turn out in elections. The personalization thesis posits that contemporary politics increasingly revolves around individual candidates, impacting voter behavior across Western democracies (Kriesi, 2012; McAllister, 2007). The literature attributes the personalization of politics to two societal processes: mediatization and partisan dealignment (McAllister, 2007). Mediatization refers to politics adapting and internalizing a media logic to gain and maintain public attention, causing the political discourse to focus on conflict and leaders’ attributes instead of party platforms and substantive issues (Strömbäck, 2008). Ultimately, mediatization alters voters’ criterion for evaluating politics and reinforces the impact of individual candidates in explaining political behavior (Aaldering et al., 2018; Aelst et al., 2012; King, 2002).

Partisan dealignment refers to the trend of eroding ties between voters and parties, characterizing all Western democracies since the 1970s (Dalton et al., 2002). Considering the strong and stable influence partisanship has on political behavior and participation (e.g., Bartels, 2000; Dalton, 2016; Johnston, 2006), partisan dealignment is theorized to produce volatile voters and unstable party systems (McAllister, 2007). Furthermore, scholars advocate that dealigned voters are more susceptible to adopting the criteria proposed by the personalized political discourse (e.g., Dassonneville, 2016; Garzia et al., 2021), making partisan dealignment a reinforcing factor in the personalization of politics.

This study advances the literature on personalized electoral behavior by introducing how candidates’ traits can mobilize voter turnout and, for the first time, examining the variation in voters’ responses to these traits across eleven U.S. presidential elections from 1980 to 2020. The relationship between trait evaluations and turnout decisions represents a novel perspective on individual leaders’ mobilizing capabilities, highlighting the vital role of voters’ cognition in determining the effectiveness of leader effects. Alongside its academic relevance, the study also has practical implications as it explores how personalization can improve democratic quality as an alternative factor for electoral participation in times of partisan dealignment and polarization.

The article continues as follows. First, the literature review concludes that analyzing trait evaluations is a viable strategy to capture leader effects and that people primarily judge candidates by their competence and character. Second, the article provides arguments for the hypotheses, expecting that people are more likely to turn out when they approve of the candidates’ competence and character (H1), judge the competing candidates differently along the respective dimension (H2), and that dealigned voters are particularly susceptible to these relationships (H3). Third, the data and method section presents how the study utilizes the American National Election Studies (ANES) data to test the hypotheses.

Fourth, the results indicate stable turnout predictions from Republican trait evaluations, with notable mobilizing effects from Democratic candidates’ competence in select elections. Furthermore, the results show that different evaluations between the candidates promote turnout and that polarized perceptions along the competence dimensions particularly mobilize dealigned voters. The results align the article with the extant literature as it concludes that leaders do matter—but that the extensive claims of the personalization thesis are exaggerated. This conclusion calls for novel approaches to studying leader effects to unveil the psychological mechanisms underpinning individuals’ political behavior.

Research Review

Global vs. Trait Evaluations as Predictors of Leader Effects

The literature usually relies on global or trait evaluations to predict leader effects. Global evaluations measure respondents’ overall feelings toward candidates on a scale ranging between like and dislike (Ohr & Oscarsson, 2013). ANES operationalizes this concept with a thermometer score ranging between 0 very much dislike and 100 like very much (Harsgor & Nevitte, 2022). Trait evaluations differ from global evaluations in that they aim to measure the specific personal characteristics respondents approve of the candidates. The specific measures vary between election studies but usually include evaluations of candidates’ leadership skills, morality, honesty, intelligence, and empathy (Bittner, 2011). Scholars then conceptualize the trait dimensions as latent constructs constituted by respondents’ evaluations of these characteristics.

Global evaluations have a long tradition as a predictor of political behavior and are standard questions in most election studies. The standardized format makes the indicator well-suited for comparative and longitudinal studies of leader effects. In the context of party choice, extensive evidence shows that voters’ global evaluations of candidates substantially impact their party choice independent of the institutional setting (e.g., Aarts & Blais, 2013; Garzia et al., 2021; Gattermann & De Vreese, 2017; Nadeau & Nevitte, 2013). Studies also indicate that the effects of global evaluation on vote choice increase over time (Garzia, 2013; Poguntke & Webb, 2005).

Furthermore, people’s general feelings toward candidates guide turnout decisions (Adams et al., 2006; Brody & Page, 1973; Ferreira da Silva et al., 2021; Harsgor & Nevitte, 2022; Weisberg & Grofman, 1983). Ferreira da Silva et al. (2021) show that positive evaluations of candidates promoted turnout in 13 European democracies between 1974 and 2016. Their results also demonstrate that the relative effects of candidate evaluations have increased over time while the relative effects of partisanship have decreased and that individuals with television-based media consumption are more susceptible to leader effects (Ferreira da Silva et al., 2021). Thus, the findings support the claims that partisan dealignment and mediatization drive the personalization of politics and affect electoral participation (McAllister, 2007). Harsgor and Nevitte (2022) confirm the relationship between global evaluations and turnout and demonstrate that negative evaluations of the out-party’s candidate can promote individual turnout decisions.

Although global evaluations have documented effectiveness as a predictor of political behavior, the concept suffers from two drawbacks. First, global evaluations are endogenous to both partisanship and vote choice, which impedes researchers’ ability to isolate independent relationships (Ferreira da Silva & Costa, 2019; Fiorina, 1978; Holian & Prysby, 2014). Second, the concept is a rather blunt indicator for research questions seeking a nuanced understanding of the mechanisms governing candidates’ influence on individuals. Although people’s general feelings toward candidates most likely influence subsequent attitudes and choices, this relationship does not shed light on the factors determining how people assess political candidates.

Against this background, the literature highlights two arguments favoring trait evaluations as predictors of political behavior. First, evaluations of candidates’ personal qualities are more exogenous to partisanship and vote choice than global evaluations are (Ferreira da Silva & Costa, 2019). Candidates’ traits are valuable and accessible heuristics for voters when assessing how candidates will perform in office and confronting unexpected events and crises (Ferreira da Silva & Costa, 2019; Holian & Prysby, 2014; Ohr & Oscarsson, 2013). Thus, when people consider their general feelings about candidates, they base their judgments on a few politically relevant personal qualities (Bittner, 2011; Ohr & Oscarsson, 2013). Consequently, peoples’ trait evaluations are more isolated to spurious relationships than global evaluations and are viable alternatives to unveil leader effects.

Second, the prominent role of candidates’ personal qualities in the political debate can affect the criterion voters use in their political decision-making. The personalization thesis attributes mediatization as one of the main reasons leaders are central to contemporary politics (McAllister, 2007). According to the mediatization theory, the commercialization of mass media has led to political parties adapting and internalizing a media logic that emphasizes individual candidates and politicians at the expense of the party platform and substantial issues (Strömbäck, 2008). Consequently, the media and the political parties drive the personalization process by framing candidates’ individual qualities as the essential criterion for voters to consider when deciding on political matters (Ferreira da Silva & Costa, 2019).

The extant literature offers four primary conclusions regarding the relationship between trait evaluations and party choice. First, studies show that positive perceptions of candidates’ traits relate to party choice independent of the electoral system (e.g., Aaldering et al., 2018; Bittner, 2011, 2021; Funk, 1996; Holian & Prysby, 2014; Jenssen & Aalberg, 2006; Miller et al., 1986; Ohr & Oscarsson, 2013). Second, studies suggest a link between the issues owned by a party and how voters evaluate the candidates’ traits (Bittner, 2011; Hayes, 2005). Scholars refer to this phenomenon as trait ownership (Hayes, 2005) or partisan stereotype (Bittner, 2011) and advocate that voters perceive candidates to perform well on trait dimensions that relate to the issues owned by the respective parties. Following this phenomenon, candidates can attract voters when they “successfully “trespass” on their opponent’s trait territory” (Hayes, 2005, p. 909). Third, dealigned voters without partisan loyalties are more susceptible to base their political choices on trait evaluations than partisan voters are (Bittner, 2011; Garzia, 2013; Garzia et al., 2021; Holian & Prysby, 2014). Fourth, studies suggest that candidates can gain electoral benefits from negative trait evaluations of the opposing candidate (Holian & Prysby, 2014, 2020).

Despite the ample evidence demonstrating the political relevance of candidates’ personal qualities, to this article’s knowledge, only one prior study has tested whether trait evaluations affect turnout decisions. Ferreira da Silva and Costa (2019) test whether respondents’ evaluations along two trait dimensions—competence and warmth—relate to turnout decisions in seven general elections in European countries with different institutional settings. Their results show that positive evaluations of candidates’ warmth increase turnout, especially among dealigned voters who did not vote previously (Ferreira da Silva & Costa, 2019).

The Nature and Number of Trait Dimensions

The literature is ambiguous regarding the nature and number of trait dimensions voters consider when evaluating political candidates. A substantive part of the literature conceptualizes a two-dimensional framework of competence and character (or warmth/trustworthiness) to fit voters’ criterion best (e.g., Bittner, 2011; Ferreira da Silva & Costa, 2019; Greene, 2001; Hayes, 2005; Johnston, 2002; Kinder et al., 1980). A second line of the literature advocates that voters evaluate candidates along four dimensions: competence (or leadership skills), integrity, reliability (or trustworthiness), and charisma (or empathy) (e.g., Kinder, 1986; Miller et al., 1986; Ohr & Oscarsson, 2013). Furthermore, scholars have conceptualized additional dimensions, such as six (Aaldering & Vliegenthart, 2016) up to twelve (Brown et al., 1986).

This study relies on Bittner’s (2011) two-dimensional framework and conceptualizes that people evaluate candidates’ competence and character. The model resembles the stereotype content model (SCM), which views the trait dimensions as competence and warmth (Fiske et al., 2007), as both models distinguish between candidates’ intentions (character/warmth) and their capacity to fulfill their intentions (competence) (Ferreira da Silva & Costa, 2019). Capabilities that constitute the competence dimension include intelligence, knowledge, and leadership skills, whereas the character dimension includes capabilities such as morality, empathy, and honesty (Bittner, 2011).

Theoretically, the two-dimensional framework is a viable representation of the criterion voters use when judging the personal qualities of leaders. Bittner (2011) shows in an extensive literature review that “about twenty-eight different typologies have been developed and used by other scholars […] generally incorporating some combination of ‘competence’, ‘leadership’, ‘character/integrity’, and ‘empathy’” (p. 34). This combination resembles how Kinder (1986) and Miller et al. (1986) conceptualize personality traits, where the former also notes a strong correlation between competence and leadership, as well as between character/integrity and empathy (Bittner, 2011). Bittner (2011) confirms Kinder’s (1986) notion and demonstrates that her dataset of trait evaluations (N = 186,000) “suggests that the largest amount of internal cohesion exists when we conceive of traits as falling into two dimensions, character and competence” (p. 39).

Practically, limiting the number of dimensions improves the possibility of temporal and spatial comparisons of leaders’ effects on turnout decisions. However, unlike the case with global evaluation scales, there is no accepted standard for measuring voters’ perceptions of candidates’ personality traits. Thus, there is significant variation in how election studies choose to operationalize the concept between different studies and over time within the same study. This ambiguity calls for a concept that offers elasticity in what indicators are used and comparability regarding the theory and results of previous studies. The chosen framework fulfills these needs. First, it allows for an analysis of how the personality traits of the presidential candidates affect the American public’s turnout decisions throughout eleven presidential elections between 1980 and 2020. Second, since the two-dimensional framework is the most common conceptualization in the literature, the choice makes the study’s results more relevant for retrospective comparisons and future studies.

The Hypothesized Relationships Between Trait Evaluations and Turnout

This article tests three hypotheses regarding the relationship between trait evaluations of presidential candidates’ competence and character and individual turnout decisions. The first hypothesis aligns with the extant literature and expects positive trait evaluations along both dimensions to affect turnout decisions positively (e.g., Adams et al., 2006; Brody & Page, 1973; Ferreira da Silva & Costa, 2019; Ferreira da Silva et al., 2021; Harsgor & Nevitte, 2022; Weisberg & Grofman, 1981). The expectation is intuitively appealing and derives from Converse’s (1966) theory of “abstaining due to alienation,” which posits that people abstain from voting when they disapprove of the proffered alternatives (Adams et al., 2006). Conversely, the theory expects the utility of voting to increase as a function of positive perceptions of the candidates.

The literature indicates that party affiliation may affect the respective trait dimensions’ relative effects on turnout (e.g., Bittner, 2011; Hayes, 2005). However, the only prior study of the focal relationship does not distinguish between candidates’ party affiliation but combines trait evaluations of both leading candidates (Ferreira da Silva & Costa, 2019). This choice may explain why the study does not find robust evidence for the relationship regarding the competence dimension. Therefore, this study acknowledges that party affiliation may affect the relative effects of competence and character on turnout decisions and distinguish between trait evaluations of Democratic and Republican candidates. However, the article does not predict the directions of the supposed relative effects due to the absence of a solid theory. Thus, the first hypothesis follows the predictions of Converse’s (1966) theory of "abstaining due to alienation" and expects that:

H1

Positive trait evaluations of candidates’ competence and character affect turnout decisions positively.

An objection to the first hypothesis is that it does not account for voters’ incentives to vote for the least unfavorable candidate out of two unsatisfactory alternatives. Downs (1957) theory of “abstaining due to indifference” accounts for the incentives for voters caught between a rock and a hard place, as it advocates that it is the lack of different alternatives that primarily depresses turnout (Adams et al., 2006). The rationale of the theory is that the utility of voting is a function of the expected difference in outcome between the alternatives (Adams et al., 2006). Consequently, Downs (1957) theory suggests that turnout decisions depend on whether voters can distinguish between the competing candidates’ competence and character. Empirical evidence using global evaluations as predictors of turnout supports that different evaluations between candidates can promote turnout (Ferreira da Silva et al., 2021; Harsgor & Nevitte, 2022). Therefore, the second hypothesis acknowledges Downs (1957) alternative explanation to turnout and expects that:

H2

Greater differences between evaluations of the Democratic and Republican candidates’ competence and character affect turnout decisions positively.

Third, the article addresses the claim of the personalization thesis that attributes partisan dealignment as a cause of personalized voting behavior. Essentially, the personalization theory relies on the social psychological model of voting behavior that conceptualizes early socialization into group identities as what primarily determines partisanship and subsequent political behavior (e.g., Campbell et al., 1960, 1966). Factors related to social identities, such as religion, regional origin, and social class, determine people’s party affiliation, which later affects how they interpret and act in the political arena (Campbell et al., 1960). Consequently, partisanship is a stable and reliable predictor of political choices and the most decisive factor in why people turn out in elections (Bartels, 2000; Budge & Farlie, 1976; Clarke et al., 2004; Oscarsson & Holmberg, 2016). Conversely, voters without partisan loyalties are more volatile in their political choices and more susceptible to short-term effects, such as leader appearances (Campbell et al., 1960; Dassonneville, 2016).

Advocators of the personalization theory argue that the past decades’ steady decline in partisanship across all Western democracies has destabilized the electorate and reinforced the significance of individual candidates and politicians (McAllister, 2007). Empirical evidence supports the claims that candidates matter more for dealigned voters in their party choice (Bittner, 2011; Dassonneville, 2016; Garzia, 2013; Garzia et al., 2021; Holian & Prysby, 2014). Furthermore, studies indicate that the same relationship applies to turnout decisions (Ferreira da Silva & Costa, 2019; Ferreira da Silva et al., 2021). Therefore, the third hypothesis follows the claims of the personalization theory and expects that:

H3

The effects of H1 and H2 are stronger for dealigned voters than for voters with a partisan identity.

Data and Methods

Using the ANES cumulative data from 1980 to 2020 (N = 33,915), this study examines the link between trait evaluations and voter turnout across eleven presidential elections.Footnote 1 ANES is a cross-sectional survey that has interviewed a representative sample of the American population after every presidential election since 1948. The chosen timeframe from 1980 to 2020 marks the inclusion of trait evaluations in the ANES and provides a solid foundation for exploring the long-term dynamics of voting behavior over four decades with significant societal and political changes.

The dependent variable is self-reported turnout (0 = abstained, 1 = voted). The article analyzes weighted dataFootnote 2 to address that survey studies are generally subject to measurement bias and that the issue is particularly pertinent when analyzing measures of turnout in post-election studies (Jackman & Spahn, 2019; Selb & Munzert, 2013; Tsai, 2020). These studies consequently overestimate turnout rates because abstainers are less prone to participate in election studies (Brehm, 1993; Voogt & Saris, 2003) and tend to misreport their turnout decisions due to social desirability bias (Belli et al., 1999; Jackman & Spahn, 2019; Selb & Munzert, 2013; Tsai, 2020). Figure 1 confirms this bias, as the self-reported turnout rates are substantially higher than the official records reported by the United States Election Project,Footnote 3 although the data is weighted. Figure 1 also reports the available attempts by ANES to validate respondents’ votes, with the 1988 survey as the most recent presidential election included.Footnote 4 These measures align more closely with official records, highlighting their accuracy and, unfortunately, limited availability of such validated data. Despite its limited availability, the validated vote records offer an opportunity to validate the findings’ robustness, as accounted for in the result section. This validation, combined with the alignment of self-reported measures with official longitudinal trends and the study’s focus on clarifying focal relationships rather than forecasting precise turnout rates, allows the article to mitigate concerns about measurement bias. Nevertheless, the article calls for a cautious interpretation of the specific turnout probabilities reported in the results.

The article employs confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to verify that the indicators for competence and character accurately capture respondents’ evaluations of presidential candidates.Footnote 5 Indicators of competence include evaluations of the candidates’ intelligence, knowledge, and leadership skills, and indicators of character are inspirational, caring, and moral.Footnote 6 The analysis normalized all indicators to range between 0 and 1.

Three findings from the CFA support that the indicators adequately capture respondents’ judgments of candidates along the dimensions of competence and character. First, the CFA confirms the theoretical expectation of associations between the indicators and the latent traits as all indicators positively load to the latent constructs (β = [0.532, 0.805], p < 0.0001). Second, the analysis underscores respondents’ capacity to distinguish between Democratic and Republican candidates’ traits as the cross-party evaluations consistently negatively correlate (r = [-0.156, − 0.276], p < 0.0001). Third, the strong within-party correlation (r = 0.943 & 0.937, p < 0.0001) indicates a partisan lens in trait evaluations, where the assessment of one dimension spills over to the second dimension.

The strong within-party correlation calls for a nuanced analysis to confirm that respondents can distinguish between the competence and character traits of candidates from the same party. Therefore, the study constructs a two-factor model that combines competence and character into one dimension per party, representing a more straightforward, unidimensional approach. This model is then compared to the initial four-factor model to determine which framework, a uni- or two-dimensional, more accurately mirrors how voters assess candidates. The study used x2 statistics alongside the following model fit indices to ascertain which model more accurately reflects voter evaluations: comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) (Acock, 2013). Both models report significant chi-square valuesFootnote 7 and moderately good fit indices.Footnote 8 The comparison revealed that the four-factor model significantly outperformed the two-factor model in chi-square values (Δχ2 = 246.5, df = 5, p < 0.001), indicating that voters effectively differentiate between competence and character traits, supporting the two-dimensional framework.

Based on the results of the CFA, the analysis utilizes the indicators in four additive indexes to test the relationship between trait evaluations and turnout. The four indexes measure evaluations of Democratic and Republican candidates’ competence and character and range between not competent/having character at all (= 0) and very competent/having character (= 1). The analysis uses the absolute difference in trait evaluations between the competing candidates to test the second hypothesis. The absolute difference variable captures the individual polarization along both dimensions and ranges between absolute indifference (= 0) and absolute difference (= 1).

Figures 2, 3 illustrate the temporal development of these predictors across the eleven presidential elections between 1980 and 2020. Figure 2 illustrates that respondents judge the competence of the competing candidates very similarly in most elections and that both parties have seen a negative trend since the 2012 election, together with increasing individual-level polarization. Figure 3 also demonstrates a negative trend in recent years, accompanied by increased polarization. However, respondents disapproved of Bill Clinton’s character in the 1992 and 1996 elections, and Joe Biden managed to reverse the downward trend for the Democratic party in the 2020 election.

The analysis uses the strength of partisanship as an indicator of partisan dealignment when testing the third hypothesis derived from the personalization thesis. The variable measures the partisan identity of respondents and ranges between “independent or apolitical”, “leaning independent”, “weak partisan”, and “strong partisan”. Figure 4 demonstrates the temporal change in the distribution of partisanship among respondents. Since 2000, the group that identifies as “independent or apolitical” is the most prevalent, constituting almost half of the sample in the previous election study. Parallel to the increase of dealigned respondents, we note a decrease in the proportion of respondents identifying as either “leaning independent” or “weak partisans”. The “strong partisans” group is relatively stable over time, at levels between 9 and 15 percent of the sample.

The choice of sociodemographic controls follows the literature on candidate evaluations and turnout decisions (e.g., Ferreira da Silva & Costa, 2019; Ferreira da Silva et al., 2021; Harsgor & Nevitte, 2022) and includes age (18–31; 31–50; 51+), gender (0 = male; 1 = female) and having a college degree (0 = no; 1 = yes). The analysis also controls for the election years using a dummy variable for each election study, with the election of 1980 as the reference category. All variables included in interaction terms are centered around its grand mean to ease multicollinearity issues (Iacobucci et al., 2017).

The analysis uses logistic regression to test the three hypotheses. The method allows for modeling the relationships between the dichotomous outcome variable turnout and the predictors while controlling for potential confounding factors. However, the hierarchical structure of the data indicates that survey responses clustered in the eleven election studies are not independent, making multilevel modeling (MLM) a more appropriate method to analyze the data. Nevertheless, initial analysis reveals that the intra-class correlation (ICC) is close to zero (ICC = 0.014), indicating that differences across election years only explain minor amounts of the variation in turnout and that logistic regression analysis is more appropriate for the data (Sommet & Morselli, 2017).

The latter sections of the results address potential bias from self-reported turnout and election-specific effects. First, the analysis tests the models against the available validated vote records. Second, the analysis replicates the original models using MLM with random intercepts for each of the eleven presidential elections. Third, the study utilizes the leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) test that iterates each model eleven times. Finally, the analysis interprets the results of the MLM, the LOOCV test, and an additional logistic regression model, including the election years as interaction terms, with the original models to answer whether the effects of trait evaluations are persistent or election-specific.

Results

Table 1 summarizes the results of three logistic regression models that stepwise test how the variables of the three hypotheses relate to the dependent variable turnout. Model 1 tests the first hypothesis by examining the relationship between trait evaluations and turnout decisions while controlling for the strength of partisanship, age, gender, education, and the election year. Model 2 tests the second hypothesis by examining how respondents’ differences in evaluations between the two competing candidates relate to turnout. Model 3 tests the third hypothesis by examining whether the strength of partisanship moderates the focal relationships in the first and second hypotheses while controlling for all the predictors of the previous two models.

The chi-square test indicates that Model 3 provides the best fit (Δχ2 (10) = 243.336, p < 0.0001). Complementing this analysis, Fig. 5 illustrates that although the three models underpredict turnout, they successfully capture the general trends of the ANES data. Moreover, these conservative estimates more closely align with the official turnout rates in Fig. 1, which may serve as an implicit correction for the overreporting bias in self-reported turnout.

Predicted probabilities of turnout based on Models 1–3 in Table 1 and turnout rates according to the ANES data.

The first hypothesis predicts positive trait evaluations of both Democratic and Republican candidates to affect turnout probabilities positively. The reduced Model 1 demonstrates that positive evaluations of Democratic candidates’ competence and Republican candidates’ character are significantly associated with higher turnout. For example, a one-unit increase in evaluations of Democratic candidates’ competence results in a 1.233 (p < 0.01) increase in turnout odds, and a one-unit increase in evaluations of Republican candidates’ character produces a 1.606 (p < 0.001) increase in turnout odds. However, Model 1 does not find significant associations between turnout and character evaluations of Democratic candidates nor competence evaluations of Republican candidates.

In Model 3, with improved fit statistics, the relationship between competence evaluations of Democratic candidates and turnout becomes insignificant. Conversely, the relationship between evaluations of Republican candidates’ character and turnout remains robust in Model 3, with an odds ratio of 1.573 and a significance level of p < 0.001. Specifically, Model 3 demonstrates a ten percentage point increase in turnout probability, from approximately 60 to 70 percent, moving from the minimum to the maximum value of evaluations of Republican candidates’ character while holding all other predictors in Model 3 at their mean values. Furthermore, Model 3 demonstrates a negative relationship between competence evaluations of Republican candidates and turnout probabilities (OR = 0.829, p < 0.01), which contradicts the expectations from hypothesis one. In summary, the results support that people’s perceptions regarding Republican candidates’ character matter for their turnout decisions, in line with the predictions of hypothesis one. However, the support for the other three associations is mixed, which we shall return to in the final part of the result section.

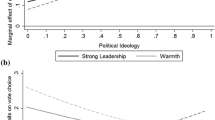

The second hypothesis predicts that respondents with different evaluations of the two competing candidates are likelier to turn out than respondents with indifferent evaluations. The results of Model 2 and Model 3, in Table 1, support the expectations, as the absolute difference in evaluations on both trait dimensions positively relates to turnout. Moreover, the relationships remain significant with stable effect sizes across the two models (Δ OR Competence (absolute difference) = 0.062; Δ OR Character (absolute difference) = 0.006). Figures 6 and 7 visualize the effects according to Model 3 while keeping all other predictors at their mean value. Because the predictors are also part of the model’s interaction terms, they are mean-centered, initially ranging between 0 and 1. The figures demonstrate that moving from indifferent to different evaluations along both trait dimensions increases turnout probabilities by almost fifteen percentage points. Consequently, the results support the predictions of the second hypothesis and Downs (1957) theory, suggesting that the utility of voting is a function of the expected difference in the election outcome.

Marginal effects on turnout probabilities of the absolute difference between evaluations of Democratic and Republican candidates’ competence and character while all other predictors are kept at their mean values. The graphs are based on the estimates of Model 3 in Table 1.

The third hypothesis predicts that these focal relationships are stronger among dealigned voters than those with partisan loyalties. First, we focus on whether the strength of partisanship moderates the relationship between trait evaluations and turnout. The results of Model 3 suggest that partisan dealignment only moderates the relationships that include evaluations of Republican candidates but not Democratic candidate evaluations. Figures 8 and 9 visualize how the strength of partisanship moderates the relationship between trait evaluations of Republican candidates and turnout probabilities while holding all other predictors at their mean values.

Marginal effects on turnout probabilities of the interaction between evaluations of Republican candidates’ competence and character and the strength of partisanship while all other predictors are kept at their mean values. The graphs are based on the estimates of Model 3 in Table 1.

The results nuance the findings of the first hypothesis, as partisan dealignment moderates which trait dimension promotes turnout. Figure 8 demonstrates that positive evaluations of Republican candidates’ competence positively relate to turnout probabilities for the group identifying as “independent or apolitical”. These dealigned respondents’ probability of turning out increases by almost ten percentage points as we move along the evaluation scale of Republican candidates’ competence. In contrast, we note negative relationships for the groups with a weak or strong partisan identity. Figure 9 demonstrates the opposite moderating effects of partisan dealignment, as the effects of competence evaluations on turnout increase with the strength of partisanship. As we move along the evaluation scale, the probability of turning out for the two partisan-aligned groups increases by about ten percentage points. The positive relationship is slightly smaller for respondents identifying as “leaning independent” and negligibly for the most dealigned voters.

The third hypothesis also predicts that dealigned voters are more susceptible to base their turnout decisions on the difference in evaluations of the competence and character of the two competing candidates. Figures 10 and 11 visualize how the relationship between the absolute difference in trait evaluations on turnout depends on respondents’ alignment with the parties while keeping all other predictors in Model 3 at their mean values. Figure 10 supports the third hypothesis as partisan dealignment increases the effect size polarized evaluations have on turnout probabilities. Maximizing the absolute difference in competence evaluations between the two candidates increases turnout probabilities by over 20 percentage points for independent or apolitical respondents compared to indifferently evaluating the candidates. The effect size decreases as respondents become more aligned with the parties. For those identifying as "strong partisans", the change is only about five percentage points along the dimension of absolute difference in competence evaluations.

Marginal effects on turnout probabilities of the interaction between the absolute difference between evaluations of Democratic and Republican candidates’ competence and character and the strength of partisanship while all other predictors are kept at their mean values. The graphs are based on the estimates of Model 3 in Table 1.

Conversely, Fig. 11 contradicts the expectations derived from the personalization thesis and does not suggest that partisan dealignment moderates the relationship between the absolute difference in character evaluations and turnout decisions. Instead, the parallel lines of Fig. 11 suggest that individual polarization regarding the competing candidates’ character is a vital predictor of turnout probabilities among all voters, independent of their partisan dealignment.

Robustness Tests: Self-Reported Turnout vs. Validated Votes?

The Data and methods section highlighted the consistent overrepresentation in self-reported turnout, necessitating model validation. Accordingly, the analysis replicated the models presented in Table 1 for the presidential elections from 1980 to 1988 in six logistic regression models, employing self-reported and validated turnout records to test the consistency of the observed effects.Footnote 9

Three key findings emerge upon replicating the models. First, the intercepts are consistently lower when using validated turnout, reflecting a more accurate measure of electoral participation. Second, the relationships observed differ from those in the original model, potentially due to the restriction of the analysis to only include three election surveys. Third, when comparing self-reported versus validated turnout models within the specific subset of the data, most relationships remain consistent across the models. This consistency underscores the robustness of the original findings, reinforcing their validity even when considering the potential biases of self-reported measures.

Robustness Tests: Persistent vs. Election-Specific Effects?

Because presidential candidates change and each election is unique, the analysis now addresses the stability of the relationships to assert whether election-specific effects inflate the results. The analysis replicated the three models from Table 1 using multilevel modeling (MLM) with random intercepts for the eleven election years and the leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) test that iterates each model eleven times by excluding one year from the sample for each iteration.Footnote 10 Both tests account for the over-time variation of the estimates, and by comparing these estimates with the original models, we can assert the stability of the relationships.

The MLM and LOOCV tests support that the relationships of Model 3, with improved fit statistics, in Table 1 are stable over time and not subject to substantial election-specific effects. Evaluations of Republican candidates’ character continue to relate positively to turnout probabilities, with an odds ratio of 1.640 (p < 0.001) for the MLM and 1.665 (p < 0.001) for the LOOCV test, compared to 1.574 (p < 0.001) for the original Model 3 in Table 1. The estimates for the absolute difference follow the same pattern. Furthermore, both tests confirm the significant interaction terms, showing that partisan dealignment moderates the relationships between competence evaluations of Republican candidates and different competence evaluations.

However, neither tests confirm the significant association between competence evaluations of Democratic candidates and turnout probabilities observed in Model 1 of Table 1. Furthermore, the range of the random effects in the MLM is between 0.020 and 0.025 (with a standard deviation of [0.142; 0.158]), indicating that the fixed effects do not account for all the temporal variation of the intercepts. These results indicate that the relationship between competence evaluations of Democratic candidates and turnout might be particularly influential during specific elections but not persistent during the whole period.

As a final examination of the potential election-specific effects, the analysis explored the specific elections when trait evaluations significantly guided turnout decisions. The analysis fitted a logistic regression model with interaction terms that estimate the change in the relationship between trait evaluations and turnout probabilities relative to the reference category of the 1980 presidential election.Footnote 11 Figures 12–15 visualize the odds ratios for the interaction terms derived from the model while holding all other predictors at their mean values.

Interaction effects of trait evaluations and election year on the odds of turnout, while all other predictors are kept at their mean values. The figures display odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals based on the logistic regression model summarized in Online Appendix 6.

Figure 12 visualizes the odds ratios for the interaction terms that include competence evaluations of Democratic candidates and confirms the suspicions of the relationship being inflated by election-specific effects. The results demonstrate that evaluations of Bill Clinton’s competence in the 1992 and 1996 presidential elections substantially impacted turnout probabilities compared to the effects of competence evaluations of Jimmy Carter in the 1980 presidential election. Figure 12 also demonstrates that competence evaluations have been more important during the last four elections, although not with the same magnitude as during the 1990s.

The relationship between character evaluations and turnout probabilities is relatively stable for both candidates between 1980 and 2008, with a negative trend beginning in the 2012 presidential election. For example, in the 2020 presidential election, a one-unit increase in positive character evaluations for Joe Biden and Donald Trump was associated with a decrease in the odds of turning out by 58 percent and 73 percent, respectively, compared to the relationship between character evaluations of Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan and the odds of turning out in the 1980 presidential election.

Conclusions

This article examines how presidential candidates’ competence and character evaluations influence voter turnout across eleven U.S. elections from 1980 to 2020. Utilizing ANES data and multiple statistical techniques, this study introduces a novel mechanism for mobilizing voter turnout in the American context and provides the first longitudinal evidence of this relationship’s relevance in explaining electoral behavior. Together, the research highlights the importance of voters’ social cognition in moderating leader effects and underscores the need to explore alternative mechanisms of electoral participation in times of increased partisan dealignment.

First, the study demonstrates mixed support for the first hypothesis, predicting that voters abstain from voting when they disapprove of candidates’ traits. Republican candidates have a stable capacity to mobilize voters through trait evaluations, and the strength of partisanship determines whether competence or character is decisive for turnout decisions. For Democratic candidates, competence evaluations substantially impacted turnout in some elections, but the results do not indicate stable effects or positive relationships between character evaluations and turnout. Second, the support for the second hypothesis is more straightforward, as different evaluations of the competing candidates consistently promote turnout among all voters. This relationship is particularly strong among partisan dealigned voters with different perceptions of the candidates’ competence.

The findings contribute to the literature on electoral behavior and personalization of politics with four main conclusions that call for further research. First, leaders matter beyond party choice. Therefore, scholars should broaden the concept of leader effects and explore leader influence in other contexts, such as crises and policy appeals. Second, voters differentiate between leaders’ personal qualities and vary in their responses to these evaluations. Therefore, analyzing trait evaluations is preferred over global evaluations for scholars aiming to understand the psychological processes driving leader effects. However, more knowledge of the nature, number, and relative strength of trait dimensions would increase the validity and benefit the literature. Third, voters respond to trait evaluations differently depending on the candidate’s party affiliation, with Democratic candidates’ competence and Republican candidates’ character proving mobilizing. Future studies may explore the reasons for this partisan divide by drawing on Hayes’ (2005) theory of trait ownership. Turnout patterns may mirror those of party choice, meaning candidates mobilize voters by effectively embodying traits typically associated with the opposing side.

Fourth, the extensive claims of the personalization thesis are exaggerated and lack nuance. Although the results show signs of increased personalized electoral participation in recent elections, the main conclusion is that candidate influence is neither a new phenomenon nor exclusive to voters without partisan loyalties. This finding aligns with the empirical literature on personalized politics (e.g., Aarts et al., 2011; Karvonen, 2010; King, 2002; Kriesi, 2012) and underscores the need for leader effect studies to pose new questions. Particularly critical is exploring the psychological mechanisms underlying why merely approving a candidate’s qualities is often insufficient to mobilize voters, while polarized perceptions consistently drive voter turnout across all voter groups. The emerging literature on affective polarization (Iyengar et al., 2019) offers a promising avenue for future studies to explore this phenomenon of voter psychology. This literature challenges traditional views of partisanship by elucidating how voters’ social identities influence their emotional and behavioral responses toward parties and candidates (e.g., Mason, 2015; Renström et al., 2023). Notably, the most crucial task is to move beyond the not-so-original conclusion that leaders matter sometimes. Instead, we aim to unveil the factors and mechanisms that condition their influence over voters.

The ambiguity of the conditions for leader effects highlights the main weaknesses of this article, where data limitations hinder detailed predictions and inferences about personalized electoral participation. The first concern is the consistent overrepresentation of turnout in self-reported data, which introduces a bias into the study’s understanding of voting behavior and turnout trends. While the supplementary analysis utilizing validated votes addresses and mitigates some of these concerns, the availability of validated vote data for only three election surveys limits the generalizability of these findings. Thus, this article encourages readers to approach the specific turnout levels predicted by the models with caution and to pursue more accurate measurements in future studies to enhance our understanding of voting behavior. Such efforts may include revisiting vote validation methods, exploring alternative methods for measuring turnout or conducting comparative studies to validate findings across various electoral contexts.

The second concern is the study’s limited ability to comprehensively explain the nature and subsequent effects of voters’ perceptions of candidates. While this article advances our understanding of personalized electoral participation over time, the cross-sectional nature of the ANES data inherently limits our ability to explore the dynamics of individual voters’ perceptions and establish causal relationships. To address these vital questions, scholars should consider novel approaches such as experimental designs, panel data, and alternative measurement methods, which can provide deeper insights into the factors shaping how people think and act politically.

Finally, the results indicate that personalization and polarization can benefit democratic participation. The increased focus on individual politicians, increasing partisan dealignment, and growing gaps between the competing candidates are often framed as a democratic problem. The assumption is that electoral participation requires deliberative debates on substantive issues, where voters sense belonging to a party while trusting the intentions and abilities of the opposing side. These results provide an alternative narrative of rational voters who make independent decisions and demand quality leadership to ensure the realization of democracy.

Data Availability

The data and replication R code is available here: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/IVENBD

Notes

For more information about the American National Election Studies cumulative datafile, see: https://electionstudies.org/data-center/anes-time-series-cumulative-data-file/

The analysis use the weighting variable VCF0009z. For a full description about the weighting method, see: https://electionstudies.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/HowToAnalyzeANESData.pdf

For more information about United States Election Projekt, see: https://www.electproject.org

For more information about ANES’s attempts of vote validation, see: https://electionstudies.org/data-quality/

See Online Appendix 1 for a full summary of the CFA.

See Online Appendix 2 for a full account of indicator composition.

Four-factor model: x2 (48) = 2391.130, p < .0001; Two-factor model: x2 (53) = 2637.654, p < .0001.

Four-factor model: CFI = .909; RMSEA = .098; TLI = .875; Two-factor model: CFI = .899; RMSEA = .097; TLI = .875.

See Online Appendix 3 for a full summary of the six logistic regression models.

See Online Appendices 4 and 5 for a full summary of the MLM and LOOCV tests.

See Online Appendix 6 for a full summary of the logistic regression model that examines the moderating effects election year has on the relationship between trait evaluations and turnout probabilities.

References

Aaldering, L., van der Meer, T., & Van der Brug, W. (2018). Mediated leader effects: The impact of newspapers’ portrayal of party leadership on electoral support. International Journal of Press-Politics, 23(1), 70–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161217740696

Aaldering, L., & Vliegenthart, R. (2016). Political leaders and the media. Can we measure political leadership images in newspapers using computer-assisted content analysis? Quality & Quantity. International Journal of Methodology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-015-0242-9

Aarts, K., Blais, A., Schmitt, H., & European Consortium for Political Research (Eds.). (2011). Political leaders and democratic elections. Oxford University Press.

Aarts, K., & Blais, A. (2013). Pull or push? The relative impact of positive and negative leader evaluations on vote choice. In K. Aarts, A. Blais, & H. Schmitt (Eds.), Political Leaders and Democratic Elections (p. 0). Oxford University Press.

Acock, A. C. (2013). Discovering structural equation modeling using Stata (1st ed.). Stata Press.

Adams, J., Dow, J., & Merrill, S. (2006). The political consequences of alienation-based and indifference-based voter abstention: Applications to presidential elections. Political Behavior, 28(1), 65–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-005-9002-1

Aelst, P., Sheafer, T., & Stanyer, J. (2012). The personalization of mediated political communication: A review of concepts, operationalizations and key findings. Journalism, 13, 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/1464884911427802

Bartels, L. M. (2000). Partisanship and voting behavior, 1952–1996. American Journal of Political Science, 44(1), 35–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/2669291

Belli, R. F., Traugott, M. W., Young, M., & McGonagle, K. A. (1999). Reducing vote overreporting in surveys: Social desirability, memory failure, and source monitoring. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 63(1), 90–108.

Bittner, A. (2011). Platform or personality? : The role of party leaders in elections (Sundsvall Floor 2 324). Oxford University Press.

Bittner, A. (2021). The personalization of politics in Anglo-American democracies. Frontiers in Political Science. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpos.2021.660607

Brehm, J. (1993). The phantom respondents: Opinion surveys and political representation. University of Michigan Press.

Brody, R. A., & Page, B. I. (1973). Indifference, alientation and rational decisions. Public Choice, 15(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01718840

Brown, S. D., Lambert, R. D., Kay, B. J., & Curtis, J. E. (1988). In the eye of the beholder: leader images in Canada. Canadian Journal of Political Science, 21(4), 729–755. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423900057425

Budge, I., & Farlie, D. (1976). A comparative analysis of factors correlated with turnout and voting choice. Party Identification and Beyond. In Party Identification and Beyond. Representations of Voting and Party Competition.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1960). The American voter. University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/A/bo24047989.html

Campbell, A., Converse, P., Miller, W. E., & Stokes, D. E. (1966). Elections and the political order. Wiley.

Clarke, H. D., Sanders, D., Stewart, M. C., & Whiteley, P. (2004). Political choice in Britain (1st ed.). Oxford University PressOxford.

Converse, P. (1966). The concept of the normal vote. In A. Campbell, D. E. Stokes, & W. E. Miller (Eds.), Elections and the political order. Wiley.

Dalton, R. J. (2016). Party identification and its implications. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics.

Dalton, R. J., McAllister, I., & Wattenberg, M. P. (2002). The consequences of partisan dealignment. In M. P. Wattenberg & R. J. Dalton (Eds.), Parties Without Partisans: Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies (p. 0). Oxford University Press.

Dassonneville, R. (2016). Volatile voters, short-term choices? An analysis of the vote choice determinants of stable and volatile voters in Great Britain. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 26(3), 273–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2016.1158181

Downs, A. (1957). An economic theory of political action in a democracy. Journal of Political Economy, 65(2), 135–150. https://doi.org/10.1086/257897

Ferreira Da Silva, F., & Costa, P. (2019). Do we need warm leaders? Exploratory study of the role of voter evaluations of leaders’ traits on turnout in seven European countries. European Journal of Political Research, 58(1), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12273

Ferreira da Silva, F., Garzia, D., & De Angelis, A. (2021). From party to leader mobilization? The personalization of voter turnout. Party Politics, 27(2), 220–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068819855707

Fiorina, M. P. (1978). Economic retrospective voting in American national elections: A micro-analysis. American Journal of Political Science, 22(2), 426. https://doi.org/10.2307/2110623

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(2), 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005

Funk, C. L. (1996). The impact of scandal on candidate evaluations: An experimental test of the role of candidate traits. Political Behavior, 18(1), 1–24.

Garzia, D. (2013). Changing parties, changing partisans: The personalization of partisan attachments in Western Europe. Political Psychology, 34(1), 67–89.

Garzia, D., da Silva, F. F., & De Angelis, A. (2021). Leaders without partisans: Dealignment, media change, and the personalization of politics. Rowman & Littlefield.

Gattermann, K., & De Vreese, C. H. (2017). The role of candidate evaluations in the 2014 European Parliament elections: Towards the personalization of voting behaviour? European Union Politics, 18(3), 447–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116517704519

Greene, S. (2001). The Role of character assessments in presidential approval. American Politics Research, 29(2), 196–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X01029002004

Harsgor, L., & Nevitte, N. (2022). Do leader evaluations (De) mobilize voter turnout? Lessons from presidential elections in the United States. Politics and Governance, 10(4), 361–373.

Hayes, D. (2005). Candidate qualities through a partisan lens: A theory of trait ownership. American Journal of Political Science, 49(4), 908–923. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2005.00163.x

Holian, D. B., & Prysby, C. (2014). Candidate character traits in the 2012 presidential election: Candidate character traits. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 44(3), 484–505. https://doi.org/10.1111/psq.12134

Holian, D. B., & Prysby, C. (2020). Polls and elections: Did character count? Candidate traits and the 2016 presidential vote. Presidential Studies Quarterly, 50(3), 666–689. https://doi.org/10.1111/psq.12636

Iacobucci, D., Schneider, M. J., Popovich, D. L., & Bakamitsos, G. A. (2017). Mean centering, multicollinearity, and moderators in multiple regression: The reconciliation redux. Behavior Research Methods, 49(1), 403–404. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-016-0827-9

Iyengar, S., Lelkes, Y., Levendusky, M., Malhotra, N., & Westwood, S. J. (2019). The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annual Review of Political Science, 22(1), 129–146. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-051117-073034

Jackman, S., & Spahn, B. (2019). Why does the american national election study overestimate voter turnout? | Political Analysis | Cambridge Core. Preprint retrieved from https://www-cambridge-org.ezproxy.ub.gu.se/core/journals/political-analysis/article/why-does-the-american-national-election-study-overestimate-voter-turnout/78AAF29C00F368C735507F0D5160AE20

Jenssen, A. T., & Aalberg, T. (2006). Party-leader effects in Norway: A multi-methods approach. Electoral Studies, 25(2), 248–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2005.06.008

Johnston, R. (2002). Prime ministerial contenders in Canada. In A. King (Ed.), Leaders’ Personalities and the Outcomes of Democratic Elections. Oxford University Press.

Johnston, R. (2006). Party identification: Unmoved mover or sum of preferences? Annual Review of Political Science, 9(1), 329–351. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.9.062404.170523

Karvonen, L. (2010). The personalisation of politics: A study of parliamentary democracies. ECPR Press.

Kinder, D. R. (1986). Presidential character revisited. In R. R. Lau & D. O. Sears (Eds.), Political cognition: The 19th annual carnegie symposium on cognition. L. Erlbaum Associates.

Kinder, D. R., Peters, M. D., Abelson, R. P., & Fiske, S. T. (1980). Presidential prototypes. Political Behavior, 2(4), 315–337.

King, A. S. (Ed.). (2002). Leaders’ personalities and the outcomes of democratic elections. Oxford University Press.

Kriesi, H. (2012). Personalization of national election campaigns. Party Politics, 18(6), 825–844. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068810389643

Mason, L. (2015). “I disrespectfully agree”: The differential effects of partisan sorting on social and issue polarization. American Journal of Political Science, 59(1), 128–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12089

McAllister, I. (2007). The personalization of politics. In R. J. Dalton & H. Klingemann (Eds.), The oxford handbook of political behavior (p. 0). NY: Oxford University Press.

Miller, A. H., Wattenberg, M. P., & Malanchuk, O. (1986). Schematic assessments of presidential candidates. The American Political Science Review, 80(2), 521–540. https://doi.org/10.2307/1958272

Nadeau, R., & Nevitte, N. (2013). Leader effects and the impact of leader characteristics in nine countries. In K. Aarts, A. Blais, & H. Schmitt (Eds.), Political leaders and democratic elections (p. 0). Oxford University Press.

Ohr, D., & Oscarsson, H. (2013). Leader Traits, Leader Image, and Vote Choice. In K. Aarts, A. Blais, & H. Schmitt (Eds.), Political Leaders and Democratic Elections (p. 0). Oxford University Press.

Oscarsson, H., & Holmberg, S. (2016). Svenska väljare (Upplaga 1:1). Wolters Kluwer.

Poguntke, T., & Webb, P. (Eds.). (2005). The presidentialization of politics: A comparative study of modern democracies (1st ed.). Oxford University PressOxford.

Renström, E. A., Bäck, H., & Carroll, R. (2023). Threats, emotions, and affective polarization. Political Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12899

Selb, P., & Munzert, S. (2013). Voter overrepresentation, vote misreporting, and turnout bias in postelection surveys. Electoral Studies, 32(1), 186–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2012.11.004

Sommet, N., & Morselli, D. (2017). Keep calm and learn multilevel logistic modeling: A simplified three-step procedure using stata, R, Mplus, and SPSS. International Review of Social Psychology, 30(1), 203–218. https://doi.org/10.5334/irsp.90

Strömbäck, J. (2008). Four phases of mediatization: An analysis of the mediatization of politics. The International Journal of Press/politics, 13(3), 228–246. https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161208319097

Tsai, C. (2020). A re-examination of American national election studies to resolve a controversy about who overreports turnout. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 32(4), 780–789. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edaa011

Voogt, R. J. J., & Saris, W. E. (2003). To participate or not to participate: The link between survey participation, electoral participation, and political interest. Political Analysis, 11(2), 164–179. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpg003

Weisberg, H. F., & Grofman, B. (1981). Candidate evaluations and turnout. American Politics Quarterly, 9(2), 197–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X8100900204

Acknowledgements

I thank the anonymous reviewers and the editors of Political Behavior for their constructive and helpful comments, which significantly improved the quality of the manuscript. I also thank my supervisors, Stefan Dahlberg and Stefan Linde, for their guidance throughout the process, and Hanspeter Kriesi for his feedback on an early manuscript draft. Finally, I thank my family for their unwavering support and encouragement.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Mid Sweden University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Segerberg, T. The Personalization of Electoral Participation? The Relationship Between Trait Evaluations of Presidential Candidates and Turnout Decisions in American Presidential Elections 1980–2020. Polit Behav (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-024-09949-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-024-09949-3