Abstract

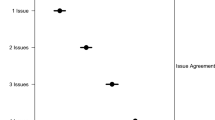

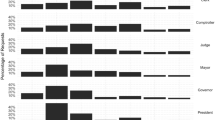

When do scandals hurt candidates? In this study, we employ a candidate conjoint experiment to understand the conditions under which candidates are most penalized for scandals. Survey respondents evaluate candidates in election scenarios that vary candidate partisanship, the presence and type of negative news about the candidate, and the amount of other information available to voters about the candidates, such as issue positions and demographics. Averaging across respondents and the distribution of candidate attributes, the results show scandal decreases the probability of voting for a candidate, but the size of this negative effect varies by context. The negative effects of scandal on voting decisions are mitigated by the amount of other information available to voters. Our findings also reveal that it is not always the case that voters are blind to the moral failings of scandal-plagued candidates in the presence of other information; voters may continue to rate scandal-plagued candidates negatively in terms of morality but prefer these candidates in terms of partisanship and shared political views.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We did not formally pre-register our hypotheses. As a result, we keep our analyses to a limited set of tests focused on those most central to the study. Replication data available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/0IN4PX.

Doherty et al. (2014) find that the passage of time does less to mitigate the negative consequences of scandals when it comes to scandals involving tax evasion.

Our study differs from Green et al. (2018) in two ways that provide advantages in internal validity that complement the field experiment: In Green et al. (2018), the evaluators or political figure being evaluated varied as uncertainty varied, while our experiment holds constant the figure being evaluated (Congressional candidate). Second, instead of relying on respondents’ self-reports to quantify uncertainty, we exogenously manipulate the quantity of information.

Zaller defines a consideration as, “any reason that might induce an individual to decide a political issue one way or the other” (1992, p. 40).

This could occur when a scandal generates high levels of national attention, similar to Hamel and Miller (2019). For example, when the Associated Press reported 2020 Congressional candidate Cal Cunningham’s extramarital affair, his campaign tried to pivot media attention to his policy positions, but soon retreated from interviews and public events except for defensive statements regarding the scandal (Robertson 2020).

One thing that could curtail partisan motivated reasoning is a divide within a partisan’s own party (Rundquist et al. 1977).

This may be further influenced by the nature of the scandal and reporting of it. For example, when the Pittsburgh Gazette broke the story of Republican Tim Murphy urging his “mistress” to have an abortion, the scandal was directly tied to his abortion policy positions (Ward 2017). In contrast, scandals are often reported with little substantive information about the candidate’s record, potentially helping to keep separate evaluations of candidate integrity and morality. For example, when Democratic Congressman Anthony Weiner admitted to tweeting a photo of his genitalia, The Washington Post report noted his partisanship “Weiner (D),” and focused on the potential ethical and legal issues of the scandal (Horowitz 2011).

Bansak et al. study how the number of tasks (up to 30) influences quality of responses and find that, “satisficing is not a serious concern that should dictate the number of tasks” (2018, p. 118).

We chose scandals that resemble the types of wrongdoing for which high profile political figures, such as Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, had recently been accused. The effects could vary if the candidate was proven to have committed the wrongdoing. Likewise, we might also anticipate effects of scandal to vary if the vignette indicated if the wrongdoing involved abuse of power (Doherty et al. 2011).

The low-information setting has at least two parallels to real elections. It may reflect situations where scandal has dominated the popular discourse, making it harder to learn other information about a candidate. It may also approximate situations where scandal is the only salient information about a lower-profile candidate (beyond party).

In low information cases in the real world, voters may still be able to infer other information about candidates just from their name, such as gender. However, gender does not have a significant marginal effect when present in the experiment.

Bansak et al. (2019) find that response quality does not suffer from “excessive satisficing” even in an application with 18 attributes.

We present information in a tabular format to make it easier for respondents to process information. This format performed well in a validation study on immigration preferences (Hainmueller et al. 2015).

The full regression equation is in pg. 4 of the Appendix. We use linear regression with cluster robust standard errors. Hainmueller et al. show the consistency of linear regression and note linear regression represents a “convenient procedure for applied researchers” (2014, p. 15). Results are similar with logistic regression (Online Appendix Table A3).

One concern about having respondents represented in the data multiple times could be that the first task may influence respondents’ answers on subsequent tasks (Hainmueller et al. 2014). Results are similar for only the first task respondents completed (Online Appendix Figure A1).

We chose ten total attributes for the high information environment to match the amount of information presented in the highest information environment from Peterson (2017).

An alternative design could have randomized where “News” appeared in the table. However, in that design, because the position of the news attribute and the amount of information would be varying, we might see the effect of scandal dissipate either because voters weigh scandal less heavily, or instead, because they do not see the information about scandal.

Supplemental analyses that collapse Republicans and Democrats or types of scandals in the analysis are in Online Figure A3 and Table A5. We do not detect significant differences in effects of scandal by copartisanship.

Republicans evaluating copartisans are somewhat less likely to vote for copartisans with any news (including positive news) relative to the No recent news condition in the high information environment, a finding that we would not have theoretically expected.

Similar to scandal, the effect of sharing partisanship with a candidate also declines as the information environment expands, consistent with Peterson (2017). Most attributes do not show significant differences as the information environment expands from medium to high, though effects vary (See Online Appendix Figures A5, A6).

Confidence intervals are 95% cluster bootstrap percentile intervals.

This measure of shared policy positions is based on comparing respondents’ pre-treatment self-reported attitudes with candidate positions. The more shared policy stances, the greater likelihood of voting for the candidate (Online Appendix Table A7).

In this model specification, we include all attributes and levels instead of solely the news and information variables. Given that issue positions and candidate demographics are not present in the low information environment, we did not include these attributes in the main specification. Due to the independent randomization of attributes and levels, including these variables in the specification does not substantially change the effects of scandal.

This analysis is limited to partisans in order to evaluate the effect of shared partisanship.

References

Abramowitz, A. I. (1991). Incumbency, campaign spending, and the decline of competition in U.S. House elections. Journal of Politics, 53(1), 34–56.

Alford, J., Teeters, H., Ward, D., & Wilson, R. (1994). Overdraft: The political cost of congressional malfeasance. Journal of Politics, 56(3), 788–801.

Bansak, K., Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J., & Yamamoto, T. (2018). The number of choice tasks and survey satisficing in conjoint experiments. Political Analysis, 26, 112–119.

Bansak, K., Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J., & Yamamoto, T. (2019). Beyond the breaking point? Survey satisficing in conjoint experiments. Political Science Research and Methods. https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2019.13.

Barnes, T., Beaulieu, E., & Saxton, G. (2020). Sex and corruption: How sexism shapes voters’ responses to scandal. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 8(1), 103–121.

Bartels, L. (2002). Beyond the running tally: Partisan bias in political perceptions. Political Behavior, 24(2), 117–150.

Basinger, S. J. (2013). Scandals and congressional elections in the post-Watergate era. Political Research Quarterly, 66(2), 385–398.

Basinger, S. J. (2018). Judging incumbents’ character: The impact of scandal. Journal of Political Marketing, 18(3), 216–239.

Bhatti, Y., Hansen, K. M., & Olsen, A. L. (2013). Political hypocrisy: The effect of political scandals on candidate evaluations. Acta Politica, 48(4), 408–428.

Blair, G., Cooper, J., Coppock, A., Humphreys, M., & Sonnet, L. (2018). estimatr: Fast estimators for design-based inference. R package.

Brown, L. M. (2006). Revisiting the character of congress. Journal of Political Marketing, 5(1–2), 149–172.

Carlson, J., Ganiel, G., & Hyde, M. S. (2000). Scandal and political candidate image. Southeastern Political Review, 28(4), 747–757.

Cobb, M., & Taylor, A. (2014). Paging congressional democrats: It was the immorality, stupid. PS: Political Science & Politics, 47(2), 351–356.

Coppock, A., & McClellan, O. A. (2019). Validating the demographic, political, psychological, and experimental results obtained from a new source of online survey respondents. Research & Politics. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168018822174.

Dimock, M., & Jacobson, G. (1995). Checks and choices: The House bank scandal’s impact on voters in 1992. Journal of Politics, 57(4), 1143–1159.

Doherty, D., Dowling, C. M., & Miller, M. G. (2011). Are financial or moral scandals worse? It depends. PS: Political Science & Politics, 44(4), 749–757.

Doherty, D., Dowling, C., & Miller, M. (2014). Does time heal all wounds? Sex scandals, tax evasion, and the passage of time. PS: Political Science & Politics, 47(2), 357–366.

Fischle, M. (2000). Mass response to the Lewinsky Scandal: Motivated reasoning or Bayesian updating? Political Psychology, 21(1), 135–159.

Franchino, F., & Zucchini, F. (2015). Voting in a multi-dimensional space: A conjoint analysis employing valence and ideology attributes of candidates. Political Science Research and Methods, 3(2), 221–241.

Funk, C. (1996). The impact of scandal on candidate evaluations: An experimental test of the role of candidate traits. Political Behavior, 18(1), 1–24.

Green, D. P., Zelizer, A., & Kirby, D. (2018). Publicizing scandal: Results from five field experiments. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 13(3), 237–261.

Hainmueller, J., Hopkins, D. J., & Yamamoto, T. (2014). Causal inference in conjoint analysis: Understanding multidimensional choices via stated preference experiments. Political Analysis, 22(1), 1–30.

Hainmueller, J., Hangartner, D., & Yamamoto, T. (2015). Validating vignette and conjoint survey experiments against real-world behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(8), 2395–2400.

Hamel, B., & Miller, M. (2019). How voters punish and donors protect legislators embroiled in scandal. Political Research Quarterly, 72(1), 117–131.

Horowitz, J. (2011). Rep. Weiner admits tweeting lewd photo of himself. The Washington Post.

Iyengar, S., & Kinder, D. R. (1987). News that matters: Television and American opinion. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Klašnja, M., Lupu, N., & Tucker, J. A. (2020). When do voters sanction corrupt politicians? Journal of Experimental Political Science. https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2020.13.

Kunda, Z. (1990). The case for motivated reasoning. Psychological Bulletin, 108(3), 480–498.

Lau, R. R., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2001). Advantages and disadvantages of cognitive heuristics in political decision making. American Journal of Political Science, 45(4), 951–971.

Long, N. (2019). The impact of incumbent scandals on senate elections, 1972–2016. Social Sciences, 8(4), 1–19.

McCurley, C., & Mondak, J. J. (1995). Inspected by #18406313: The influence of incumbents’ competence and integrity in U.S. House elections. American Journal of Political Science, 39, 864–885.

McDermott, M., Schwartz, D., & Vallejo, S. (2015). Talking the talk but not walking the walk: Public reactions to hypocrisy in political scandal. American Politics Research, 43(6), 952–974.

Nyhan, B. (2015). Scandal potential: How political context and news congestion affect the president’s vulnerability to media scandal. British Journal of Political Science, 45(2), 435–466.

Nyhan, B. (2017). Media scandals are political events: How contextual factors affect public controversies over alleged misconduct by U.S. governors. Political Research Quarterly, 70(1), 223–236.

Paschall, C., Sulkin, T., & Bernhard, W. (2019). The legislative consequences of congressional scandals. Political Research Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912919826224.

Pereira, M. M., & Waterbury, N. W. (2018). Do voters discount political scandals over time? Political Research Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912918795059.

Peters, J. G., & Welch, S. (1980). The effects of charges of corruption on voting behavior incongressional elections. American Political Science Review, 74(3), 697–708.

Peterson, E. (2017). The role of the information environment in partisan voting. Journal of Politics, 79(4), 1191–1204.

Praino, R., Stockemer, D., & Moscardelli, V. G. (2013). The lingering effect of scandals in congressional elections: Incumbents, challengers, and voters. Social Science Quarterly, 94(4), 1045–1061.

Rapoport, R., Metcalf, K., & Hartman, J. (1989). Candidate traits and voter inferences: An experimental study. Journal of Politics, 51(4), 917–932.

Robertson, G. D. (2020). Cunningham keeps low in NC Senate race marked by his affair. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/election-2020-virus-outbreak-senate-elections-sex-scandals-north-carolina-5b2812777ae5e5582858360aaf22b76d.

Rundquist, B. S., Strom, G. S., & Peters, J. G. (1977). Corrupt politicians and their electoral support: Some experimental observations. American Political Science Review, 71, 954–963.

Saad, L., & Newport, F. (2015). “Email” defines Clinton; “immigration” defines Trump. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/185486/email-defines-clinton-immigration-defines-trump.aspx.

Taber, C. S., & Lodge, M. (2006). Motivated skepticism in the evaluation of political beliefs. American Journal of Political Science, 50(3), 755–769.

Von Sikorski, C. (2018). The aftermath of political scandals: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Communication, 12, 3109–3133.

Vonnahme, B. M. (2014). Surviving scandal: An exploration of the immediate and lasting effects of scandal on candidate evaluation. Social Science Quarterly, 95(5), 1308–1321.

Ward, P. S. (2017). Rep. Tim Murphy popular with pro-life movement, urged abortion in affair, texts suggest. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

Walter, A. S., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2019). Explaining voters’ heterogeneous responses to politicians’ immoral behavior. Political Psychology, 40(5), 1075–1097.

Welch, S., & Hibbing, J. R. (1997). The effects of charges of corruption on voting behavior in congressional elections, 1982–1990. Journal of Politics, 59(1), 226–239.

Zaller, J. R. (1992). The nature and origins of mass opinion. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Zaller, J. R. (1998). Monica Lewinsky’s contribution to political science. PS: Political Science & Politics, 31(2), 182–189.

Acknowledgements

We thank four anonymous reviewers and the editors for their thoughtful feedback during the review process.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Funck, A.S., McCabe, K.T. Partisanship, Information, and the Conditional Effects of Scandal on Voting Decisions. Polit Behav 44, 1389–1409 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09670-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09670-x