Abstract

Aims

The few remaining old-growth forests in the northeastern United States are often comprised of ectomycorrhizal (EM) tree-dominated patches surrounded by arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) tree-dominated secondary forests. We examined how (1) distance from old growth and tree neighborhood composition influenced EM colonization, fungal richness, and fungal community composition of Betula lenta L. (black birch) seedlings, a common EM tree that colonizes abandoned agricultural fields, and (2) potential effects of EM fungal genera on seedling physiological performance.

Methods

We sampled soils and tree composition from the edge of an EM-dominated old-growth forest into an adjacent AM-dominated secondary forest. We used soils to grow black birch seedlings in a growth chamber bioassay. We measured seedling EM colonization and investigated effects of EM fungi and soil characteristics on seedling physiological performance.

Results

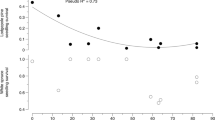

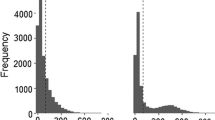

We identified 20 EM fungal species and found decreases in EM colonization and fungal richness with distance from old growth, with many taxa present only near the edge. Neighborhood EM tree abundance best explained EM colonization while distance interacted with EM tree basal area to best explain EM fungal richness of seedlings. Soils from neighborhoods lacking EM trees resulted in sparse EM colonization of seedlings. We found no clear effects of EM fungal genera on seedling performance, but we detected a slight decrease in seedling photosynthetic rate with distance from old growth.

Conclusions

Old-growth forests can be reservoirs of EM fungi, and EM tree patches can function as localized inoculum sources in AM-dominated secondary forests, potentially facilitating EM tree establishment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abrams MD (1998) The red maple paradox. Bioscience 48:355–364

Agerer R (1987) Colour atlas of ectomycorrhizae. Einhorn Verlag, Schwabisch Gmünd

Agerer R (2001) Exploration types of ectomycorrhizae. Mycorrhiza 11:107–114

Albornoz FE, Ryan MH, Bending GD et al (2022) Agricultural land-use favours Mucoromycotinian, but not glomeromycotinian, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi across ten biomes. New Phytol 233:1369–1382

Arias MG, McGee G, Dovciak M (2023) Persistent effects of land-use history on myrmecochorous plant and epigeic ant assemblages across an ecoregional gradient in New York State. Biodivers Conserv 32:965–985

Arnold TW (2010) Uninformative parameters and model selection using Akaike’s Information Criterion. J Wildl Manag 74:1175–1178

Baar J, Horton TR, Kretzer AM, Bruns TD (1999) Mycorrhizal colonization of Pinus muricata from resistant propagules after a stand-replacing wildfire. New Phytol 143:409–418

Baxter JW, Dighton J (2001) Ectomycorrhizal diversity alters growth and nutrient acquisition of grey birch (Betula populifolia) seedlings in host–symbiont culture conditions. New Phytol 152:139–149

Bellemare J, Motzkin G, Foster DR (2002) Legacies of the agricultural past in the forested present: an assessment of historical land-use effects on rich mesic forests. J Biogeogr 29:1401–1420

Bending GD, Read DJ (1995) The structure and function of the vegetative mycelium of ectomycorrhizal plants. New Phytol 130:401–409

Bennett JA, Klironomos J (2019) Mechanisms of plant–soil feedback: interactions among biotic and abiotic drivers. New Phytol 222:91–96

Bennett JA, Maherali H, Reinhart KO, Bennett JA, Maherali H, Reinhart KO, Lekberg Y, Hart MM, Klironomos J (2017) Plant-soil feedbacks and mycorrhizal type influence temperate forest population dynamics. Science 355:181–184

Bloom AJ, Chapin FS, Mooney HA (1985) Resource limitation in plants-an economic analogy. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 16:363–392

Bogar L, Peay K, Kornfeld A, Huggins J, Hortal S, Anderson I, Kennedy P (2019) Plant-mediated partner discrimination in ectomycorrhizal mutualisms. Mycorrhiza 29:97–111

Borchers SL, Perry DA (1990) Growth and ectomycorrhiza formation of Douglas-fir seedlings grown in soils collected at different distances from pioneering hardwoods in southwest Oregon clear-cuts. Can J For Res 20:712–721

Braun EL (1950) Deciduous forests of Eastern North America. Blackburn Press, Caldwell

Brundrett MC (2009) Mycorrhizal associations and other means of nutrition of vascular plants: understanding the global diversity of host plants by resolving conflicting information and developing reliable means of diagnosis. Plant Soil 320:37–77

Brundrett MC, Tedersoo L (2020) Resolving the mycorrhizal status of important northern hemisphere trees. Plant Soil 454:3–34

Bruns TD, Peay KG, Boynton PJ, Grubisha LC, Hynson NA, Nguyen NH, Rosenstock NP (2009) Inoculum potential of Rhizopogon spores increases with time over the first 4 year of a 99-yr spore burial experiment. New Phytol 181:463–470

Cardinale BJ, Palmer MA, Collins SL (2002) Species diversity enhances ecosystem functioning through interspecific facilitation. Nature 415:426–429

Chapin FS, Moilanen L (1991) Nutritional controls over nitrogen and phosphorus resorption from alaskan birch leaves. Ecology 72:709–715

Claus A, George E (2005) Effect of stand age on fine-root biomass and biomass distribution in three european forest chronosequences. Can J For Res 35:1617–1625

Cline ET, Ammirati JF, Edmonds RL (2005) Does proximity to mature trees influence ectomycorrhizal fungus communities of Douglas-fir seedlings? New Phytol 166:993–1009

Collier FA, Bidartondo MI (2009) Waiting for fungi: the ectomycorrhizal invasion of lowland heathlands. J Ecol 97:950–963

Correia M, Espelta JM, Morillo JA, Correia M, Espelta JM, Morillo JA, Pino J, Rodríguez‐Echeverría S (2021) Land-use history alters the diversity, community composition and interaction networks of ectomycorrhizal fungi in beech forests. J Ecol 109:2856–2870

Cortese AM, Horton TR (2023) Islands in the shade: scattered ectomycorrhizal trees influence soil inoculum and heterospecific seedling response in a northeastern secondary forest. Mycorrhiza 33:33–44

Crabtree RC, Bazzaz FA (1992) Seedlings of black birch (Betula lenta L.) as foragers for nitrogen. New Phytol 122:617–625

Crabtree RC, Bazzaz FA (1993) Seedling response of four birch species to simulated nitrogen deposition: ammonium vs. nitrate. Ecol Appl 3:315–321

Deacon JW, Donaldson SJ, Last FT (1983) Sequences and interactions of mycorrhizal fungi on birch. Plant Soil 71:257–262

Dickie IA, Davis M, Carswell FE (2012) Quantification of mycorrhizal limitation in beech spread. New Z J Ecol 36:6

Dickie IA, Montgomery RA, Reich PB, Schnitzer SA (2007) Physiological and phenological responses of oak seedlings to oak forest soil in the absence of trees. Tree Physiol 27:133–140

Dickie IA, Reich PB (2005) Ectomycorrhizal fungal communities at forest edges. J Ecol 93:244–255

Dovčiak M, Frelich LE, Reich PB (2005) Pathways in old–field succession to white pine: seed rain, shade, and climate effects. Ecol Monogr 75:363–378

Dovčiak M, Hrivnák R, Ujházy K, Gömöry D (2008) Seed rain and environmental controls on invasion of Picea abies into grassland. Plant Ecol 194:135–148

Dulmer KM, LeDuc SD, Horton TR (2014) Ectomycorrhizal inoculum potential of northeastern US forest soils for American chestnut restoration: results from field and laboratory bioassays. Mycorrhiza 24:65–74

Eagar AC, Cosgrove CR, Kershner MW, Blackwood CB (2020) Dominant community mycorrhizal types influence local spatial structure between adult and juvenile temperate forest tree communities. Funct Ecol 34:2571–2583

Fleming LV, Deacon JW, Last FT, Donaldson SJ (1984) Influence of propagating soil on the mycorrhizal succession of birch seedlings transplanted to a field site. Trans Br Mycological Soc 82:707–711

Flinn KM, Marks PL (2007) Agricultural legacies in forest environments: tree communities, soil properties, and light availability. Ecol Appl 17:452–463

Foster D, Orwig DA, McLaughlin JA (1996) Ecological and conservation insights from reconstructive studies of temperate old-growth forests. Trends Ecol Evol 11:419–424

Frelich LE, Reich PB (2003) Perspectives on development of definitions and values related to old-growth forests. Environ Reviews 11:S9–S22

Galante TE, Horton TR, Swaney DP (2011) 95% of basidiospores fall within 1 m of the cap: a field-and modeling-based study. Mycologia 103:1175–1183

Gardes M, Bruns TD (1993) ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes - application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol Ecol 2:113–118

Gardes M, Bruns TD (1996) ITS-RFLP matching for identification of Fungi. In: Clapp JP (ed) Methods in molecular biology™. Species diagnostics protocols: PCR and other nucleic acid methods. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ, pp 177–186

Goodman DM, Trofymow JA (1998) Comparison of communities of ectomycorrhizal fungi in old-growth and mature stands of Douglas-fir at two sites on southern Vancouver Island. Can J For Res 28:574–581

Green DS (1983) The efficacy of dispersal in relation to safe site density. Oecologia 56:356–358

Griffiths GR, McGee GG (2018) Lack of herbaceous layer community recovery in post-agricultural forests across three physiographic regions of New York. J Torrey Bot Soc 145:1–20

Grove S, Saarman NP, Gilbert GS, Faircloth B, Haubensak KA, Parker IM (2019) Ectomycorrhizas and tree seedling establishment are strongly influenced by forest edge proximity but not soil inoculum. Ecol Appl 29:e01867

Hall B, Motzkin G, Foster DR, Syfert M, Burk J (2002) Three hundred years of forest and land-use change in Massachusetts, USA. J Biogeogr 29:1319–1335

Harley JL (1940) A study of the root system of the beech in woodland soils, with especial reference to mycorrhizal infection. J Ecol 28:107–117

Hayward J, Horton TR, Pauchard A, Nuñez MA (2015) A single ectomycorrhizal fungal species can enable a Pinus invasion. Ecology 96:1438–1444

Hedges LV, Gurevitch J, Curtis PS (1999) The meta-analysis of response ratios in experimental ecology. Ecology 80:1150–1156

Hobbie EA, Agerer R (2010) Nitrogen isotopes in ectomycorrhizal sporocarps correspond to belowground exploration types. Plant Soil 327:71–83

Horton TR, Bruns TD (1998) Multiple-host fungi are the most frequent and abundant ectomycorrhizal types in a mixed stand of Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and bishop pine (Pinus muricata). New Phytol 139:331–339

Horton TR, Bruns TD, Parker VT (1999) Ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with Arctostaphylos contribute to Pseudotsuga menziesii establishment. Can J Bot 77:93–102

Horton TR, van der Heijden MGA (2008) The role of symbioses in seedling establishment and survival. In: Seedling Ecology and Evolution. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 189–212.

Horton TR, Molina R, Hood K (2005) Douglas-fir ectomycorrhizae in 40- and 400-year-old stands: mycobiont availability to late successional western hemlock. Mycorrhiza 15:393–403

Humphrey JW, Peace AJ, Jukes MR, Poulsom EL (2004) Multiple-scale factors affecting the development of biodiversity in UK plantations. In: Forest biodiversity: Lessons from history for conservation, pp 143–162

Ishida TA, Nara K, Hogetsu T (2007) Host effects on ectomycorrhizal fungal communities: insight from eight host species in mixed conifer–broadleaf forests. New Phytol 174:430–440

Izzo A, Canright M, Bruns TD (2006) The effects of heat treatments on ectomycorrhizal resistant propagules and their ability to colonize bioassay seedlings. Mycol Res 110:196–202

Jagodzinski AM, Ziółkowski J, Warnkowska A, Prais H (2016) Tree age effects on fine root biomass and morphology over chronosequences of Fagus sylvatica, Quercus robur and Alnus glutinosa stands. PLOS ONE 11:e0148668

Jonsson LM, Nilsson M-C, Wardle DA, Zackrisson O (2001) Context dependent effects of ectomycorrhizal species richness on tree seedling productivity. Oikos 93:353–364

Kårén O, Högberg N, Dahlberg A, Jonsson L, Nylund J-E (1997) Inter- and intraspecific variation in the ITS region of rDNA of ectomycorrhizal fungi in Fennoscandia as detected by endonuclease analysis. New Phytol 136:313–325

Köhler J, Yang N, Pena R, Raghavan V, Polle A, Meier IC (2018) Ectomycorrhizal fungal diversity increases phosphorus uptake efficiency of European beech. New Phytol 220:1200–1210

Kranabetter JM, Berch SM, MacKinnon JA, Ceska O, Dunn DE, Ott PK (2018) Species–area curve and distance–decay relationships indicate habitat thresholds of ectomycorrhizal fungi in an old-growth Pseudotsuga menziesii landscape. Divers Distrib 24:755–764

Last FT, Dighton J, Mason PA (1987) Successions of sheathing mycorrhizal fungi. Trends Ecol Evol 2:157–161

Liang M, Johnson D, Burslem DFRP, Yu S, Fang M, Taylor JD, Taylor AFS, Helgason T, Liu X (2020) Soil fungal networks maintain local dominance of ectomycorrhizal trees. Nat Commun 11:2636

Liang H, Wu H, Zou G (2008) A note on conditional AIC for linear mixed-effects models. Biometrika 95:773–778

Luo Z, Guan H, Zhang X, Liu N (2017) Photosynthetic capacity of senescent leaves for a subtropical broadleaf deciduous tree species Liquidambar formosana Hance. Sci Rep 7:6323

Lyford W (1980) Development of the root system of northern red oak, (Quercus rubra L). Harv For Paper no 21:29

MacArthur RH, Wilson EO (1966) The theory of Island Biogeography. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Marks PL (1995) Reading the landscape: primary vs. secondary forests. Arnoldia 55:2–10

Mason PA, Wilson J, Last FT, Walker C (1983) The concept of succession in relation to the spread of sheathing mycorrhizal fungi on inoculated tree seedlings growing in unsterile soils. Plant Soil 71:247–256

Matlack GR (2009) Long-term changes in soils of second-growth forest following abandonment from agriculture. J Biogeogr 36:2066–2075

Matsuda Y, Takano Y, Shimada H, Yamanaka T, Ito S (2013) Distribution of ectomycorrhizal fungi in a Chamaecyparis obtusa stand at different distances from a mature Quercus serrata tree. Mycoscience 54:260–264

Mazerolle MJ (2020) AICcmodavg: Model Selection and Multimodel Inference Based on (Q)AIC (c). R package version 2.3.1. https://cran.r-project.org/package=AICcmodavg. Accessed 25 Aug 2023

McGuire KL (2007) Common ectomycorrhizal networks may maintain monodominance in a tropical rain forest. Ecology 88:567–574

Moreau PA, Borovicka J (2010) Epitypification of Naucoria bohemica, Agaricales, Hymenogastraceae. Czech Mycol 62:33–42

Mueller-Dombois D, Ellenberg H (1974) Aims and methods of vegetation ecology. Wiley and Sons, New York

Nara K (2006) Ectomycorrhizal networks and seedling establishment during early primary succession. New Phytol 169:169–178

Nara K (2006) Pioneer dwarf willow may facilitate tree succession by providing late colonizers with compatible ectomycorrhizal fungi in a primary successional volcanic desert. New Phytol 171:187–198

Nara K, Nakaya H, Wu B, Zhou Z, Hogetsu T (2003) Underground primary succession of ectomycorrhizal fungi in a volcanic desert on Mount Fuji. New Phytol 159:743–756

Nguyen NH, Hynson NA, Bruns TD (2012) Stayin’ alive: survival of mycorrhizal fungal propagules from 6-yr-old forest soil. Fungal Ecol 5:741–746

Nuñez MA, Horton TR, Simberloff D (2009) Lack of belowground mutualisms hinders Pinaceae invasions. Ecology 90:2352–2359

Oksanen J et al (2019) Vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.5-2. https://cran.rproject.org/web/package=vegan. Accessed 25 Aug 2023

Peay KG, Bruns TD (2014) Spore dispersal of basidiomycete fungi at the landscape scale is driven by stochastic and deterministic processes and generates variability in plant–fungal interactions. New Phytol 204:180–191

Peay KG, Bruns TD, Kennedy PG, Bergemann SE, Garbelotto M (2007) A strong species–area relationship for eukaryotic soil microbes: island size matters for ectomycorrhizal fungi. Ecol Lett 10:470–480

Peay KG, Garbelotto M, Bruns TD (2010) Evidence of dispersal limitation in soil microorganisms: isolation reduces species richness on mycorrhizal tree islands. Ecology 91:3631–3640

Pinheiro J et al (2020) nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. R package version 3.1-151. https://cran.r-project.org/package=nlme. Accessed Accessed 25 Aug 2023

Phillips RP, Brzostek E, Midgley MG (2013) The mycorrhizal-associated nutrient economy: a new framework for predicting carbon–nutrient couplings in temperate forests. New Phytol 199:41–51

Policelli N, Horton TR, Hudon AT et al (2020) Back to roots: the role of ectomycorrhizal fungi in boreal and temperate forest restoration. Front Forests Global Change 3:1–15

R Core Team (2020) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria

Rogers RS (1978) Forests dominated by hemlock (Tsuga canadensis): distribution as related to site and postsettlement history. Can J Bot 56:843–854

Royo AA, Pinchot CC, Stanovick JS, Stout SL (2019) Timing is not everything: assessing the efficacy of pre- versus post-harvest herbicide applications in mitigating the burgeoning birch phenomenon in regenerating hardwood stands. Forests 10:324

Säfken B, Rügamer D, Kneib T, Greven S (2021) Conditional model selection in mixed-effects models with cAIC4. J Stat Softw 99:1–30

Schoch CL, Seifert KA, Huhndorf S, Robert V, Spouge JL, Levesque CA, Chen W, Consortium FB (2012) Nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region as a universal DNA barcode marker for Fungi. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109:6241–6246

Shah F, Nicolás C, Bentzer J, Shah F, Nicolás C, Bentzer J, Ellström M, Smits M, Rineau F, Canbäck B, Floudas D, Carleer R, Lackner G, Braesel J, Hoffmeister D, Henrissat B, Ahrén D, Johansson T, Hibbett DS, Martin F, Persson P, Tunlid A (2016) Ectomycorrhizal fungi decompose soil organic matter using oxidative mechanisms adapted from saprotrophic ancestors. New Phytol 209:1705–1719

Simard SW, Perry DA, Smith JE, Molina R (1997) Effects of soil trenching on occurrence of ectomycorrhizas on Pseudotsuga menziesii seedlings grown in mature forests of Betula papyrifera and Pseudotsuga menziesii. New Phytol 136:327–340

Smith SE, Read DJ (2010) Mycorrhizal symbiosis. Academic Press, Cambridge

South DB, Harris SW, Barnett JP, Hainds MJ, Gjerstad DH (2005) Effect of container type and seedling size on survival and early height growth of Pinus palustris seedlings in Alabama, U.S.A. For Ecol Manag 204:385–398

Spake R, van der Linde S, Newton AC, Suz LM, Bidartondo MI, Doncaster CP (2016) Similar biodiversity of ectomycorrhizal fungi in set-aside plantations and ancient old-growth broadleaved forests. Biol Conserv 194:71–79

Stuart EK, Castañeda-Gómez L, Macdonald CA, Wong-Bajracharya J, Anderson IC, Carrillo Y, Plett JM, Plett KL (2022) Species-level identity of Pisolithus influences soil phosphorus availability for host plants and is moderated by nitrogen status, but not CO2. Soil Biol Biochem 165:108520

Tedersoo L, Bahram M, Dickie IA (2014) Does host plant richness explain diversity of ectomycorrhizal fungi? Re-evaluation of Gao (2013) data sets reveals sampling effects. Mol Ecol 23:992–995

Tedersoo L, Jairus T, Horton BM, Abarenkov K, Suvi T, Saar I, Kõljalg U (2008) Strong host preference of ectomycorrhizal fungi in a tasmanian wet sclerophyll forest as revealed by DNA barcoding and taxon-specific primers. New Phytol 180:479–490

Thiet RK, Boerner REJ (2007) Spatial patterns of ectomycorrhizal fungal inoculum in arbuscular mycorrhizal barrens communities: implications for controlling invasion by Pinus virginiana. Mycorrhiza 17:507–517

Tourville JC, Zarfos MR, Lawrence GB, McDonnell TC, Sullivan TJ, Dovciak M (2023) Soil biotic and abiotic thresholds in sugar maple and American beech seedling establishment in forests of the northeastern United States. Plant and Soil. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-023-06123-2

Trappe JM (1962) Cenococcum graniforme-its distribution, ecology, mycorrhiza formation, and inherent variation. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Washington, Seattle

Twieg BD, Durall DM, Simard SW (2007) Ectomycorrhizal fungal succession in mixed temperate forests. New Phytol 176:437–447

van der Heijden MGA, Klironomos JN, Ursic M, Moutoglis P, Streitwolf-Engel R, Boller T, Wiemken A, Sanders IR (1998) Mycorrhizal fungal diversity determines plant biodiversity, ecosystem variability and productivity. Nature 396:69–72

van der Heijden MGA, Martin FM, Selosse M-A, Sanders IR (2015) Mycorrhizal ecology and evolution: the past, the present, and the future. New Phytol 205:1406–1423

Weckel M, Tirpak JM, Nagy C, Christie R (2006) Structural and compositional change in an old-growth eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) forest, 1965–2004. For Ecol Manag 231:114–118

White TJ, Bruns TD, Lee SB, Taylor JW (1990) Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA Genes for phylogenetics. In: White TJ, Bruns TD, Lee SB, Taylor JW (eds) PCR - protocols and applications - a laboratory manual. Academic Press, Cambridge, pp 315–322

Whitney GG (1990) The history and status of the hemlock-hardwood forests of the Allegheny Plateau. J Ecol 78:443–458

Yanai RD, Park BB, Hamburg SP (2006) Vertical and horizontal distribution of roots in northern hardwood stands of varying age. Can J For Res 36:450–459

Zhang K, Dang H, Tan S, Wang Z, Zhang Q (2010) Vegetation community and soil characteristics of abandoned agricultural land and pine plantation in the Qinling Mountains, China. For Ecol Manag 259:2036–2047

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff at the Mianus River Gorge for providing logistical help with this project. Allison Lyubomirskaya provided invaluable help with collection of soils and neighborhood tree data. We thank Dr. Stephen Stehman for his assistance with experimental design as well as Dr. Jamie Lamit and Dr. Andrew Newhouse for reviewing previous versions of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding was provided by a Mianus River Gorge Research Assistant Program Fellowship, Edna Bailey Sussman Foundation internship, SUNY ESF Graduate Student Association research grant, and a Lowe-Wilcox scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Andrew M. Cortese designed and implemented field protocols and set up the growth chamber bioassay. Andrew M. Cortese and John E. Drake conducted physiological measurements of seedlings. Andrew M. Cortese, John E. Drake, Martin Dovciak, and Jonathan B. Cohen contributed to data analysis. Andrew M. Cortese and Thomas R. Horton conducted molecular identification of EM fungi from seedlings. All authors contributed to writing and editing all versions of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest are declared by the authors.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Isabel Mujica.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 80.0)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Cortese, A.M., Drake, J.E., Dovciak, M. et al. Proximity to an old-growth forest edge and ectomycorrhizal tree islands enhance ectomycorrhizal fungal colonization of Betula lenta L. (black birch) seedlings in secondary forest soils. Plant Soil 493, 391–405 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-023-06237-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-023-06237-7