Abstract

Purpose

Nitrogen (N) transfer from white clover (Trifolium repens cv.) to ryegrass (Lolium perenne cv.) has the potential to meet ryegrass N requirements. This study aimed to quantify N transfer in a mixed pasture and investigate the influence of the microbial community and land management on N transfer.

Methods

Split root 15N-labelling of clover quantified N transfer to ryegrass via exudation, microbial assimilation, decomposition, defoliation and soil biota. Incorporation into the microbial protein pool was determined using compound-specific 15N-stable isotope probing approaches.

Results

N transfer to ryegrass and soil microbial protein in the model system was relatively small, with one-third arising from root exudation. N transfer to ryegrass increased with no microbial competition but soil microbes also increased N transfer via shoot decomposition. Addition of mycorrhizal fungi did not alter N transfer, due to the source-sink nature of this pathway, whilst weevil grazing on roots decreased microbial N transfer. N transfer was bidirectional, and comparable on a short-term scale.

Conclusions

N transfer was low in a model young pasture established from soil from a permanent grassland with long-term N fertilisation. Root exudation and decomposition were major N transfer pathways. N transfer was influenced by soil biota (weevils, mycorrhizae) and land management (e.g. grazing). Previous land management and the role of the microbial community in N transfer must be considered when determining the potential for N transfer to ryegrass.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The productivity of agricultural systems must be improved to satisfy the increased demand from the growing global population, with 70 to 100% more food required by 2050 (Tilman et al. 2011; Ray et al. 2013). This heightened demand is frequently met by increasing nitrogen (N) fertiliser applications, with N often the nutrient which limits crop growth. However, it is unsustainable and environmentally damaging to continually over-apply N fertiliser to increase productivity (Vitousek et al. 2009). N pollution from agriculture contributes to eutrophication of terrestrial and aquatic systems, acidification of soils, global warming and ozone depletion (Anderson et al. 2002; Fowler et al. 2013). Furthermore, the high profile criticism of the carbon footprint of livestock production is driving an imperative to reduce fertiliser inputs in intensively managed systems (Herrero et al. 2016). An average of 355 thousand tonnes of N fertiliser are applied to UK grasslands every year, averaging 54 kg N ha−1 yr−1 (DEFRA 2020). Therefore, there is renewed interest in the use of N fixing legumes to improve N supply to non-legumes (Paynel et al. 2008; Fustec et al. 2010; Thilakarathna et al. 2016).

The ability of legumes to form symbiotic relationships with rhizobia makes them a key component of mixed swards. Clover (Trifolium repens L.) is capable of fixing N equivalent of up to 150 kg N ha−1 y−1 (Elgersma and Hassink 1997). The fixed N is subsequently bioavailable and can be transferred via a range of pathways to non-legumes, contributing between 0 to 80% of non-legume N (Høgh-Jensen and Schjoerring 1997; Moyer-Henry et al. 2006; Rasmussen et al. 2007; Gylfadóttir et al. 2007; Chalk et al. 2014). The importance of plant N transfer, and the contribution of individual N transfer pathways, is dependent on the influence of rhizodeposits on mineralisation-immobilisation-turnover (MIT) in soil, competition between plants and the soil microbial community, the capacity for N uptake by the receiving plant, and availability of other N sources (Jensen 1996). Optimisation of N transfer has the potential to increase crop yields via improved soil fertility and nutrient status, providing high quality feed for grazing animals, and maximise the benefits of mixed intercropping systems (Haynes 1980; Thilakarathna et al. 2016), as well as reducing the environmental effects of reactive N (Galloway et al. 2013). Utilising legume N fixation as a source of N for forage crops, e.g., ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) in sustainable grassland management is currently limited by poor understanding of the relative importance of different N transfer pathways within a mixed sward (Thilakarathna et al. 2016). To maximise the benefits of the association between legumes and non-legumes, a better understanding of the underlying mechanisms and factors which govern N transfer is needed. There are a number of biotic N transfer pathways between legumes and non-legumes, which are also influenced by management practices. Fixed nitrogen, e.g., as ammonium and amino acids has been shown to significantly contribute to total N rhizodeposition in early-growth stages of legumes (Lesuffleur et al. 2013). Root exudates are either directly incorporated into non-legumes, with uptake of inorganic and organic N (Näsholm et al. 2009), or via MIT by soil microbes, facilitating indirect N transfer of root exudates (van Kessel et al. 2009; Jalonen et al. 2009). Furthermore, root exudates contain other compounds which stimulate arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) symbiosis (e.g., flavonoids, strigolactones), another key pathway of N transfer (Steinkellner et al. 2007; Wahbi et al. 2016; Thilakarathna et al. 2016; Coskun et al. 2017). Similar to root exudates, mycorrhizae influence N transfer directly, via mycelial connections between legumes and non-legumes (Høgh-Jensen 2006; Meng et al. 2015), and indirectly, by N uptake into the mycorrhizal system, reducing N losses. Retained N can subsequently be transferred to non-legumes (Hodge and Fitter 2010; Asghari and Cavagnaro 2012). AMF, alongside the soil microbial community, support decomposition of senescing legume tissues providing N for non-legumes (Fustec et al. 2010). This is indirect, requiring MIT prior to uptake by non-legumes, but it has been estimated 2 to 26% of biologically fixed N can be transferred via decomposition of roots and nodules (Ledgard and Steele 1992; Jørgensen et al. 1999; Wichern et al. 2008; Louarn et al. 2015). Given the slower nature of this pathway, it contributes to N transfer in the latter stages of plant growth. This pathway incorporates decomposition of both above and belowground legume tissue, and is influenced by the management of mixes pastures. Grazing will remove aboveground biomass for decomposition, but the majority will be returned as excretion (Thilakarathna et al. 2016). Furthermore, defoliation has the potential to increase decomposition of remaining belowground legume tissues, promoting N transfer via this pathway (Ledgard 2001; Dahlin and Stenberg 2010; Peoples et al. 2015). The influence of plant pests on N transfer has also been investigated. For example, Sitona sp. weevils, which are common invertebrate pests of white clover, cause increased N transfer following clover root damage, reduced efficiency of N uptake and increased decomposition of sloughed roots and promote ‘leakage’ of N from legume roots (Murray and Clements 1998; Murray et al. 2002). Through these biotic pathways, with potential influences from land management, N transfer from non-legumes to legumes accounts for 0–8% of legume N, while non-legumes can have up to 80% of N derived from N transfer from legumes (Høgh-Jensen and Schjoerring 2000; Paynel and Cliquet 2003; Rasmussen et al. 2007; Gylfadóttir et al. 2007; Jamont et al. 2013).

The complexity of N transfer between legumes and non-legumes belowground means that it is challenging to directly determine the importance of individual N transfer pathways, particularly as they are inter-dependent. Reducing the complexity of the grassland N-cycle can help to elucidate the relative importance of different N transfer pathways, in particular by controlling abiotic factors (e.g. irrigation, temperature, N fertiliser application and soil N) to quantify biotic N transfer pathways (Chalk et al. 2014; Thilakarathna et al. 2016). A number of experimental approaches have been applied to quantify N transfer between legumes and non-legumes, as reviewed by Chalk et al. (2014). The two most common methods that are suitable for both field and laboratory experiments are 15N isotope dilution and 15N-shoot labelling. However, the dilution method is indirect, time-limited (due to uptake of applied 15N fertiliser by clover and subsequent exudation) and has high observed variability (Barraclough 1995; Viera-Vargas et al. 1995; Chalk et al. 2014). 15N-shoot labelling is direct, although it is not a natural N uptake pathway in grasslands and little attention has been paid to the potential alteration of root dynamics and subsequent N transfer (Chalk et al. 2014). 15N-labelling via natural pathways of N2 fixation using 15N2 (e.g. (Frey and Schuepp 1992) and root uptake, via transplantation (e.g. (Carlsson and Huss-Danell 2014) or split root labelling (e.g. Martin et al. 1991; Johansen and Jensen 1996), enables continuous 15N labelling. While not suitable for a field setting, split root labelling has provided comparable N transfer estimates to shoot labelling (Martin et al. 1991) and can be used to quantify individual N transfer pathways under controlled conditions (Wichern et al. 2008; Chalk et al. 2014; Thilakarathna et al. 2016). One caveat must be the disturbance of roots during set-up of split-root labelling, which may influence N transfer pathways, particularly exudation, mycorrhizal networks and root-root contact, which must be considered during experimental design. However, this method is suitable for quantifying N transfer to the soil microbial community, an important competing fate for legume-N, which also acts as an N transfer pathway during microbial decomposition and turnover, and plays a key role in indirect N transfer of exudates, for mycorrhizal pathways and legume tissue decomposition (Ta and Faris 1987; Parton et al. 2007; Charteris et al. 2016). Within the soil N pool, proteinaceous N accounts for up to 60%, and plays a key role in microbial metabolic activity (e.g., enzymes, structures, transport Schulten and Schnitzer 1998; Friedel and Scheller 2002). Targeting this pool allows direct interrogation of the biomolecular fate of N following N fixation (e.g. Chiewattanakul et al. 2022), and during N transfer from legumes to non-legumes. Recent developments in novel compound-specific 15N-stable isotope probing (SIP) approaches have the potential to enable the direct quantification of clover-N transfer to the soil microbial protein pool (Charteris et al. 2016).

This study aimed to investigate near-to-natural ecosystem N transfer between clover and ryegrass using split-root 15N-labelling of clover. N transfer to ryegrass was quantified following manipulation of N transfer pathways including the addition of soil biota proposed to promote N transfer (e.g. mycorrhizae, below ground herbivores), mimicking of agricultural practices (e.g. grazing and cover crop incorporation), and sterilisation of soil to remove competition for N from the soil microbial community. This approach allowed direct quantification for N transfer pathways (e.g. exudation). N transfer was determined using bulk 15N analyses and compound-specific 15N analyses of the soil protein pool, the latter providing essential information regarding the role of the soil microbial community in N transfer and competition with non-legumes for legume-derived N in a mixed cropping system. We hypothesise that (i) N transfer to ryegrass will be an important source of available N for ryegrass and soil microbes, via both direct and indirect transfer of clover-N, (ii) N transfer will be supported by the soil microbial community during decomposition and through mycorrhizae, (iii) damage to clover via pests or defoliation will increase N transfer. This has the potential for use in the development of more sustainable agricultural strategies to support crop N supply and reduce fertiliser N input requirements and associated environmental costs currently limited by the lack of understanding regarding N transfer pathways (Wahbi et al. 2016; Thilakarathna et al. 2016).

Methods

Soil collection

Soil was collected from a permanent grazed grassland system at the North Wyke Farm Platform (Okehampton, Devon, UK; 50°46’N, 3°54’W). The soil is a clay loam topsoil (36% clay) and the vegetation was Lolium spp. interspersed with Cynosurus, Festuca, Agrostis, Holcus and Dactylis spp. (Bol et al. 2004; Harrod and Hogan 2008; Peukert et al. 2012; Orr et al. 2016). The mean annual rainfall is 1055.7 mm with a mean annual temperature of 9.6 °C (Harrod and Hogan 2008). All farmlets were managed in the same way and received 200 kg N ha−1 of N fertiliser alongside P, K and S before cutting (Orr et al. 2016). Soil cores (264; 10 cm depth, 5.5 cm diameter) were collected on a 50 m grid (Figure S1) across the Farm Platform in June and July 2012. Soil was air-dried and sieved to 2 mm with vegetation and stones removed to give a composite sample and stored at 4 °C until required for use. Soil total carbon (TC) was 5.23% and total nitrogen (TN) was 0.57%. Soil pH was 6.3. Acid washed horticultural silver sand was sieved (1 mm) and furnaced at 450 °C.

N transfer experiments

All plants used in the study were from white clover (Trifolium repens L.) and perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne cv) mother plants established from seed in soil, and plants used in subsequent experiments were all from the same mother plants to reduce plant genetic variations. Experiments were conducted in a temperature-controlled greenhouse (20 °C) with a photoperiod of 16 h. Additional lighting was provided when natural lighting was below 30 W m−2 and shading was provided when natural light was above 220 W m−2. Plants were watered daily with tap water and weekly with a modified nutrient solution adapted from (Hewitt 1966); omitting N, one-fifth strength; Table S1) prior to the experimental period.

A split root 15N-labelling technique was used to determine N transfer between plants which enabled 15N incorporation by a natural N uptake process and ensured all N compounds subject to transfer were 15N labelled (Wichern et al. 2008; Chalk et al. 2014). Established clover and grass plants were rooted into either sand (25 g) and soil (15 g) compartments (10 cm height, 2 cm diameter), with clover roots evenly split between the labelling and transfer compartments (LabC and TraC, respectively; Fig. 1) and allowed to establish for 3 weeks prior to treatment. 15N-urea was applied in five of the eight treatments to the LabC, shown in Table 1. It was not applied in the negative control, or exudate and decomposition treatment, where 15N-labelled inputs (exudates and clover shoots, respectively) were used. The base of the compartments was tapered and plugged with furnaced glass wool to maintain aerobic conditions throughout the soil profile. During incubation, compartments were maintained at 60% water holding capacity (WHC) using full strength nutrient solution daily (Table S1; (Hewitt 1966). Losses (e.g. leaching or gaseous) were limited by the experimental design by constant soil moisture.

Experimental set-up of split root 15N-labelling technique. The labelling compartment (LabC), where the 15N-urea was added, contained sand (orange) and transfer compartment (TraC) and receiving compartment (RecC) contained soil (brown). |Part (a) shows the two-compartment set-up used. Clover roots were split across the LabC and TraC and grass roots were all in the TraC. Part (b) shows the three-compartment set-up used, with clover roots split evenly between the LabC and TraC, and ryegrass roots split evenly between TraC and RecC for the clover to ryegrass experiment. For the ryegrass to clover experiment, ryegrass roots were split between the LabC and TraC, and clover roots between TraC and RecC. Diagram is not to scale

The one-and two-compartment experiments were classified into three categories: (i) controls; (ii) land management/ N type and (iii) presence of organisms, shown in Table 1. Each treatment had four replicates. Two control experiments were conducted. The first added no 15N-label, with double distilled water (DDW; 1 ml) added to the LabC. The second control experiment used sterilised soil, via autoclaving, with 15N-urea (1 ml, 30 mM of 98 atom% 15N) applied to LabC. For land management treatments / N type incubations, one treatment only applied 15N urea to LabC (1 ml 30 mM of 98 atom% 15N). This treatment quantified N transfer in the experiment when all natural pathways were present, and there was no other controls on N transfer (e.g., grazing, pests), while also representing fertiliser addition to the pasture. The decomposition treatment mixed finely chopped clover shoots (2.1 ± 0.3 atom% 15N, 0.7 g FWt), which were collected from clover grown separately with 15N urea (1 ml 30 mM of 98 atom% 15N), into TraC soil. The root exudate treatment applied root exudates collected from 15N-labelled clover into the TraC soil. Root exudates were obtained from clover grown across two sand-filled compartments, with 15N-urea (1 ml 30 mM of 98 atom% 15N) applied to one, and root exudates collected from the second. The exudates were collected by leaching and immediately used to water the TraC in the exudate treatment. Finally, the defoliation treatment mimicked grazing, by removal of clover shoots 100 h after application of 15N-urea (1 ml 30 mM of 98 atom% 15N). The third category, presence of organisms, added either Sitona spp. or AMF (Rhizophagus irregularis) into the TraC with 15N-urea (1 ml 30 mM of 98 atom% 15N) added to the LabC. This AMF was selected as it is commonly used in agriculture, can be found in most soils and has a wide range of host plants. All incubations were halted at 480 h when aboveground biomass was removed immediately to stop N transfer. Roots were removed from the compartments as an intact root system attached to the shoot, separated from above ground biomass, and washed with DDW to remove soil. Additionally, the soil was handpicked for any roots broken during this process. Shoots, roots and soil were frozen (−20 °C), freeze-dried and plant biomass determined.

N transfer from clover to ryegrass and vice versa was determined using an additional receiving compartment (RecC; Fig. 1b). In both directions, the donor plant roots were evenly split between the LabC and TraC, and the receiver plant roots were split between the TraC and RecC. In both treatments (n = 4), 15N-urea (1 mL of 30 mM 98 atom % 15N urea) was applied to the LabC and the incubation was halted at 100 h. Clover and ryegrass root exudates in the clover to ryegrass, and ryegrass to clover experiments, respectively, were collected from the LabC by leaching with DDW (40 ml), to avoid contaminations from soil free amino acids (FAAs) in the TraC. Leachate was frozen and freeze-dried for amino acid (AA) preparation and analysis. This procedure was repeated with sand (80 g) and DDW (80 mL) with a mixture of AA standards (100 µL of 1 mg mL−1 for each AA; Table S7) to determine recovery of AAs from sand.

Extraction, isolation and derivatisation of hydrolysable AAs from soil

Extraction, isolation and derivatisation of soil AAs were conducted as described by Charteris et al. (2016). Freeze-dried soil (100 mg) was hydrolysed with 6 M HCl (5 mL; 100 °C for 24 h) under an N2 atmosphere to yield total hydrolysable amino acids (THAA). Both free and bound AAs (FAA and BAA, respectively) are included to determine total soil protein (Roberts and Jones 2008). Norleucine (Nle; 100 µL of 400 µg mL−1) was added as an internal standard. Hydrolysates were collected by centrifugation, dried and stored under 0.1 M HCl at −20 °C. AAs were isolated using acidified DOWEX 50WX8 200–400 mesh ion exchange resin (Metges and Petzke 1997) and derivatised to N-acetyl, O-isopropyl (NAIP) derivatives (Corr et al. 2007a; Knowles et al. 2010).

Instrumental analyses

Total C and N analyses and 15N isotopic composition determinations

Finely ground soil, shoots and roots were sealed into tin capsules (50 to 70 µg N). Percentage TC, TN and 15N enrichment of soil, shoots and roots were determined at Rothamsted Research (North Wyke) using an elemental analyser (EA; Carlo Erba CN NA2000 analyser; Milan, Italy) coupled to a SerCon 20–22 isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS; SerCon Ltd, Crewe, UK). Instrument performance was monitored, and values calibrated using standards detailed in Table S2. For consistency, all values are reported as atom %, due to high 15N enrichment above range of the delta scale (Brand and Coplen 2012).

AA quantification

A GC-FID (7890B Agilent Technologies) fitted with a DB-35 capillary column (60 m × 0.32 mm i.d., 0.5 µm phase thickness) was used for AA quantification by comparison to the internal standard. NAIP-AAs were identified based on their known elution order and comparison with AA standards (Corr et al. 2007b; Charteris et al. 2016). The carrier gas was helium (constant flow, 2.0 mL min−1) and the initial temperature programme was 70 °C (2 min) ramped to 150 °C (15 °C min−1), then to 210 °C (2 °C min−1) and finally to 270 °C (5 min, 8 °C min−1). Data were acquired and analysed using HP Chemstation (version 1.0, Agilent Technologies).

15N enrichment of AAs

The δ15N values of individual AAs, as NAIP derivatives, were determined using GC-C-IRMS as outlined in Charteris et al. (2016), except the oxidation reactor comprised high purity copper and nickel wires, and was maintained at a temperature of 1030 °C. AA δ15N values were determined relative to that of a monitoring N2 gas with a known δ15N value. δ15N values were only accepted when 75% of an in-house mixture of AA standards, analysed before and after, yielded δ15N values within ± 1 ‰ of the known value (determined offline by EA-IRMS) and the remainder were within ± 1.5 ‰. Data were acquired and analysed using Isodat 3.0 (Thermo Scientific).

Calculations

The percentage 15N retention of the applied 15N-label reflects the 15N enrichment, and the size of the N pool, and allows comparison between treatments. The enrichment (E) of a pool can be expressed as the number of moles of 15N derived from the applied 15N-substrate present in that pool (\({n}_{N}\) is the number of moles of N in the pool and AFE is the atom fraction excess):

The atom fraction is the proportion of 15N in the total N pool calculated from the atom % 15N for bulk soil and plants, and from δ15N values for total hydrolysable amino acids:

where Rstd is the 15N/14N ratio of Air, the international isotopic standard for N (Mariotti 1983). Atom %15N was used for highly enriched pools, while the delta scale was required for amino acids due to lower 15N enrichment. This was essential to avoid loss of sensitivity of compound-specific determinations. As atom fractions, and subsequently calculated %15N retention/incorporation are utilised, there is not direct comparison of the two scales of 15N enrichment. Using the E of a pool, it is possible to calculate percentage 15N retention of the applied substrate using Eq. 4 (EA is the number of moles of excess 15N applied, above natural abundance):

Percentage 15N incorporated of applied (%15NA) and of retained (%15NR) into the soil protein pool was calculated from the concentration and δ15N values of individual AAs as in Charteris et al. (2016). %15NA incorporated into AAs of the applied 15N was used to account for the importance of all pathways of applied 15N, whilst %15NR for AAs in the soil demonstrates the ability of the soil microbial community to utilise transferred 15N.

Calculation of N transfer between plants was modified from Ledgard et al. (1985) to calculate the proportion of N transferred from the donor (D) to the receiver plant (R). The proportion transferred (Ptransfer) was calculated using:

where 15N indicates the 15N content of the receiver, donor and soil (S). N transfer to the soil protein pool was also calculated in the same way using the 15N content of the THAA pool. The 15N content of the donor roots in the TraC was used to calculate Ptransfer as the 15N label was not evenly distributed through the plant and this was considered more representative of the 15N available for transfer. The 15N content of the soil was also included in this calculation to avoid overestimation of N transfer to the receiver plant as significant transfer to soil was observed. The 15N content of the pools was calculated using:

where the atom % 15N \({\mathrm{excess}}_{\mathrm{X}}\) is the difference between the atom % 15N of the control and the treatment for D, R or S pools, and TNX is the total nitrogen content of the D, R and S pools. The Ntransfer can subsequently be calculated using:

Finally, the percentage of N in the receiver plant derived from donor transfer (NdftR) is calculated using:

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software (R Core Team 2021). Prior to statistical analyses, data was tested for normality (Shapiro–Wilk) and homogeneity of variance (Brown-Forsythe). Statistical analyses to determine significant differences in observations were applied throughout the study using one-way ANOVA or student t-tests. Following ANOVA analyses, when the null hypothesis was rejected, a Holm-Sidak test was used to conduct pair-wise multiple comparisons. The significance level was set at p ≤ 0.05 for all statistical analyses.

Results

One- and two compartment N transfer experiments

Effect of treatment on biomass

The biomass (dry weight) of clover and ryegrass for treatments in the one- and two-compartment experiments is shown in Table 2. Clover shoot biomass was significantly less than that of the control for the 15N-urea treatment (p < 0.01), however, there was no significant difference for all other treatments. Overall, total clover biomass did not significantly vary between the treatments (p > 0.05). Clover root biomass was significantly larger in the 15N-urea only and exudation treatments compared to the control (p < 0.01), although these treatments were not significantly different to all other treatments. Ryegrass biomass was significantly larger compared to the control in the 15N-urea treatment, exudation treatment and sterile treatment (p < 0.05), and was also larger in all other treatments, although this difference was not significant.

The abundance of root nodules was also affected by treatment, with a reduced abundance in LabC roots for all treatments compared to the control, except the sterile treatment (Table S3). This reduction was significant for the 15N-urea only (p < 0.05), defoliation (p < 0.001) and fungi (p < 0.05) treatments. Nodule abundance was also significantly reduced in the TraC for the sterile treatment compared to the control treatment (p < 0.05), however, there were no other significant differences in nodules abundance in all other treatments (Table S3).

Percentage 15N retention

Percentage of the applied 15N-urea retained in the different pools is shown in Table 3, calculated from δ15N values and N content of pools (Table S4). The ‘unknown’ pool is the difference between ‘accounted for’ 15N and total 15N applied, which was presumed to be in LabC roots (not determined due to very high enrichment over 10 atom% 15N), 15N-labelled LabC root exudates and remaining 15N-label in LabC sand. Other losses, such as foliar ammonia release are expected to be minor given the experimental set-up (Sommer et al. 2004). 15N-incorporation into clover shoots did not significantly vary with treatment, with high variation between replicates (p > 0.05). The weevil treatment had greater 15N retention in clover TraC roots (2.9 ± 0.7%), which was significantly larger than the sterile treatment (p < 0.05), however, there were no other significant differences between treatments, due to high variation between replicates. The decomposition treatment had significantly higher 15N retention in TraC soil compared to all other treatments (Table 3; all p < 0.001). This was also observed for ryegrass roots and shoots in this treatment compared to all other treatments, which were not significantly different to each other (p > 0.05). The variable 15N retention of clover indicated that the quantity of 15N available for transfer to the soil microbial community and ryegrass varied between treatments and replicates, which was accounted for in subsequent N transfer calculations.

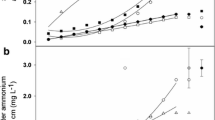

Plant nitrogen transfer

The proportion of N in the receiver plant derived from the donor plant indicated the potential for N-transfer in the different treatments. 15N enrichment of TraC roots was used to quantify N transfer in all treatments except the decomposition treatment, where clover shoot 15N-enrichment was used. N transfer was greatest for the decomposition treatment, with 9.3 ± 1.7% of ryegrass-N derived from the clover shoots incorporated into the soil, which was significantly larger than all other treatments except the sterile treatment (Fig. 2a). In the sterile treatment, N transfer from clover roots accounted for 6.0 ± 0.8% of ryegrass N, while N transfer was comparable for 15N-urea only (3.2 ± 1.1%) and defoliation (2.4 ± 0.3%) treatments and following fungi (2.5 ± 0.5%) and weevil (2.5 ± 0.3%) addition (Fig. 2a). N transfer was least in the exudation treatment, with N transferred from the clover roots accounting for 1.1 ± 0.3% of grass N.

The proportion of nitrogen in (a) receiver plant, (b) soil and (c) soil protein pool derived from the donor plant via N transfer (NdftR). Values are mean ± SE (n = 4). Lower case letters indicate if there are significant differences between the treatments determined via a one-way ANOVA and multiple pairwise comparisons (p < 0.05)

Soil N transfer

There was no observable change in the TN of soil for all treatments compared to the control and 15N-urea control (Table S4). The proportion of soil N derived from clover is shown in Fig. 2b, which was significantly higher for the decomposition treatment compared to all other treatments (p < 0.001). N transfer to soil was also higher compared to 15N-urea only for the defoliation (0.72 ± 0.16%) and fungi (0.88 ± 0.31%) treatments, although the difference was not significant (p > 0.05). The exudation, sterile and weevil treatments were comparable to the positive control (Fig. 2b).

The soil protein pool indicates newly biosynthesised AAs by the soil microbial community and the proportion of clover derived-N present in the soil protein pools is shown in Fig. 2c. This was determined via soil AA concentrations (Table S5) and compound-specific δ15N determination of AAs (Table S6). The THAA concentration in TraC soil did not significantly vary between treatments (Table 4; p > 0.05), although there were some significant differences for individual AAs in the defoliation treatment compared to the control (e.g. valine (Val), leucine (Leu) and threonine (Thr), Table S5). N transfer of clover-derived 15N to the soil protein pool (Fig. 2) showed significant differences between treatments (p < 0.001). The proportion of N in the soil protein pool derived from clover was significantly higher in the decomposition treatment (1.71 ± 0.58%) compared to all other treatments (p < 0.001). It should be noted this may be an overestimation of newly biosynthesised THAAs derived from clover-15N as it was not possible to separate partly decomposed clover in this treatment. The 15N-urea treatment was also significantly higher than all treatments (excluding decomposition; 0.0046 ± 0.003%, p < 0.01) and all other treatments were not significantly different from each other (p > 0.05). This indicated that whilst N transfer to soil did not significantly vary, assimilation into the microbial protein pool was reduced by all treatments except decomposition, compared to the positive control. Within the THAA pool, the distribution of 15N derived from clover did not significantly vary between treatments, with 15N incorporation dominated by glutamine/glutamate (Glx), aspargine/aspartate (Asx), alanine (Ala), glycine (Gly) and proline (Pro), with comparatively low incorporation into Val, phenylalanine (Phe), hydroxyproline (Hyp) and tyrosine (Tyr) (Figure S2).

Three-compartment N transfer experiments

Biomass

Addition of 15N-urea significantly increased clover biomass produced in the clover to ryegrass experiment compared to controls, likely due to a priming effect induced by higher N availability in the LabC (Table 5a). In the reverse experiment, ryegrass to clover, ryegrass shoot biomass increased, however, this was not significant (p > 0.05) (Table 5b). In the TraC, in both experiments, the total biomass of the receiver plant was low in the 15N-urea treatment compared to the control treatment, although the observed differences were not significant (p > 0.05).

Root exudation

THAAs released from roots were significantly higher for clover (0.10 ± 0.01 mg) in the clover to ryegrass experiment compared to ryegrass in the ryegrass to clover experiment (0.041 ± 0.006 mg; p < 0.01). The THAA exudates account for varying recovery of individual AAs, due to retention in the sand, determined using a standard AA mixture (Table S7). Within the THAAs exuded by clover, Pro, Asx, Glx and Phe were the most abundant AAs exuded by clover and Glx, Asx, Phe and Hyp were the most abundant AAs exuded by grass roots (Fig. 3).

Mass of individual AAs exuded from clover (black) and ryegrass (grey) roots. Values are mean ± SE (n = 4) and are corrected for recovery rates of AA standards from sand (Table S7)

% 15N retention

The 15N retention into clover, soil and grass pools were determined from 15N values, %TN and plant biomass (Table S8, Tables 5 and 6). In the clover to ryegrass experiment, uptake into clover biomass accounted for 41.7 ± 4.0%, largely in RecC roots and clover shoots. Only a small portion was transferred to TraC roots (0.72 ± 0.11%). Comparatively higher uptake into the grass donor plant in the grass to clover experiment was observed, accounting for 72.6 ± 11.1% of applied 15N, with the majority of this retained 15N present in grass shoots. The higher 15N retention into donor TraC roots in ryegrass to clover compared to clover to ryegrass meant higher availability for N transfer. This was supported by significantly higher 15N retention in the receiver plant in ryegrass to clover than clover to ryegrass (p < 0.001). Retention in both soil compartments was also higher in the ryegrass to clover compared to clover to ryegrass (Table 6), although enrichment in the RecC was below detection limits in the clover to ryegrass experiment.

N transfer

The proportion of donor derived-N in the receiver plant was calculated based on the yield-dependent calculation (Eq. 8), accounting for differences in available 15N for transfer. N transfer to ryegrass from clover was 0.8 ± 0.3% and N transfer to clover from ryegrass was 1.3 ± 0.6% at 100 h. There was no significant difference between the two N transfer directions. Greater N transfer to the receiver plant was associated with a smaller proportion of donor-derived N in the soil at 100 h, while incorporation into the soil protein pool was comparable in both directions (Table 7). Within the soil protein pool, THAA concentration was larger for both treatments compared to the control, and in the RecC compared to the TraC in the same treatment (Table 7). However, there was no significant difference between the incubations for the overall THAA concentration (p > 0.05), although there were differences within the THAA pool for individual AAs (e.g. Phe, Lys and Tyr) (Tables S9 and S10). 15N assimilation into the individual AAs was calculated from δ15N values (Tables S11 and S12) and AA concentrations (Tables S9 and S10). Within the AA pool, 15N-incorporation was largest for Glx and Asx in the ryegrass to clover TraC. These pools also showed higher 15N-incorporation in the clover to ryegrass TraC, with Pro also showing high 15N-incorporation, which may reflect the distribution of AAs released in root exudates (Fig. 3). It was not possible to detect any assimilation into the soil protein pool or transfer to the bulk soil in the clover to ryegrass RecC soil, while incorporation into individual AAs in the ryegrass to clover was dominated by Asx, Glx, serine (Ser), Ala and Gly (Figure S3).

Discussion

Optimisation of N transfer in mixed clover-ryegrass swards provides an opportunity to use natural ecosystem processes to improve nutrient supply and increase productivity in intensively managed grassland systems (Elgersma and Hassink 1997; Paynel et al. 2008; Fustec et al. 2010; Thilakarathna et al. 2016). This approach has the potential to provide both economic and environmental benefits, through reduced N fertiliser requirements. This study has investigated important N transfer pathways and their potential contribution to overall N transfer using a model clover-ryegrass system. The application of a 15N-labelling approach allowed us to identify and quantify the strength of N transfer via a range of interdependent pathways between white clover and perennial ryegrass (Fig. 4). The modifications to the clover-ryegrass model system aimed to quantify selected N transfer pathways (e.g. exudation), investigate possible increased N transfer via due to land management (e.g. N input, decomposition, defoliation simulating grazing) and the presence of organisms (weevils and mycorrhiza addition).

The N transfer (NdftR) pathways in a model clover-ryegrass system as affected by management (simulated grazing by defoliation, N fertiliser application or shoot residue decomposition) and presence of soil organisms (weevils, mycorrhiza). The bidirectional N transfer at 100 h was determined via the three-compartment experiment. All values are mean ± SE (n = 4)

15N transfer from clover to ryegrass following only 15N-urea fertilisation was relatively minor compared to previous observations (Høgh-Jensen and Schjoerring 2000; Rasmussen et al. 2007; Gylfadóttir et al. 2007). Observed N transfer is generally low in split root labelling experiments (less than 10%) via this natural N uptake pathway (van Kessel et al. 1985; Martin et al. 1991; Ikram et al. 1994; Chalk et al. 2014). Furthermore, the relatively large variability associated with the estimated N transfer has previously been observed in N transfer quantification (Kurppa et al. 2010). A key contributing factor in this study was likely the N status of the soil, which received regular N inputs during livestock production across the farm platform, therefore, N demands were likely met by the existing soil N pool, and there was no indication of N deficiency (e.g. yellow leaves, stunted growth) (Bol et al. 2004; Harrod and Hogan 2008; Orr et al. 2016). N transfer has previously been found to be driven by a source and sink relationship between plants in low N status soils with low N inputs (Murray and Clements 1998; Gylfadóttir et al. 2007). N transfer of the same magnitude as this study has been observed in higher N status soil with other legume-non-legume systems, suggesting plant N transfer is less important in higher N status soils (Sen and Chalk 1996; Teste et al. 2015). Other factors which may have limited N transfer include the young sward age, limited plant size in incubation tubes and disrupted fungal networks during incubation set-up (Jones and Willett 2006; Louarn et al. 2015). N demands were met by increased N fixation, as decreased nodulation under N fertilisation indicated reduced N fixation requirements. Therefore, soil properties (i.e. N status) and crop maturity are important factors for consideration when utilising optimised N transfer in sustainable land management strategies to improve crop N supply. N transfer to soil and the soil protein pool in the 15N-urea only treatment was also relatively low compared to the receiving plant (0.64 ± 0.25% and 0.26 ± 0.10%, respectively). Within the THAA pool, incorporation into individual AAs reflected fundamental biosynthetic pathways of AA biosynthesis (Figure S2a). Incorporation was highest in Glx, due to its central role in AA biosynthesis, with NH4+ incorporated via the GS/GOGAT (glutamine synthetase/ glutamine oxoglutarate amino transferase) and GDH pathways (glutamate dehydrogenase) (Nelson and Cox 2017; Caspi et al. 2018). The Glx pool is subsequently essential for the formation of other AA pools, either by direct conversion (e.g. Pro) or transamination reactions (e.g. Ser, Phe, and Tyr) (Knowles et al. 2010; Nelson and Cox 2017; Caspi et al. 2018). AAs with more biosynthetic steps exhibited lower 15N incorporation (e.g. Phe and Tyr via chorismate), as did secondary AAs (e.g. Hyp) (Adams and Frank 1980). Incorporation was also influenced by pool size, with higher incorporation observed in larger pools (e.g. Ala, Gly, Pro). Hierarchical trends in 15N incorporation for individual amino acids were comparable for all treatments as this reflected the biosynthetic pathways of AA biosynthesis (Figure S2).

Quantification of selected N transfer pathways

One pathway that was possible to determine in isolation was exudation, and ca. 35% of total N transfer from clover to ryegrass in the unmodified system (15N-urea only) was derived from clover root exudates. This significant contribution to total N transfer has previously been observed in young clover-ryegrass mixed swards (Paynel et al. 2001; Paynel and Cliquet 2003). N-containing root exudates are transferred via direct root-root contact, mass flow and microbial-mediated transfer in a mixed cropping system, although direct root-to-root contact was removed in this model system. The proportion of N transferred from clover to the soil microbial community by exudation accounted for 20% of the N transferred to the soil protein pool, demonstrating the importance of root exudates for microbial N acquisition and their role in indirect transfer of exuded N to non-legumes following microbial turnover (Coskun et al. 2017). N transfer via root exudates will likely be further increased when legume and non-legume roots are allowed to intermingle in soil, due to the importance of root contact in this process and enhanced exudation via microbe-plant and plant-plant interactions (Merbach et al. 1999; Inderjit and Weiner 2001; Bais et al. 2006; Canarini et al. 2019).

The microbial community is central to several N transfer pathways, and this was confirmed by 15N incorporation and N transfer into the soil microbial protein pool (Fig. 2 and S2). Sterilisation aimed to remove this pathway, limiting N transfer to mass flow and direct root-to-root contact. The increased N transfer observed was likely due to reduced competition between ryegrass and the soil microbial community (Inselsbacher et al. 2010). Comparable transfer to the soil was observed, which was more bioavailable to ryegrass with lower microbial activity, supported by lower incorporation into the soil protein pool. There was still evidence of assimilation into the soil protein pool, indicating recolonization of the soil by microbes originating from root surfaces, yielding an optimised microbial community, which likely also supported plant N transfer (Marschner and Rumberger 2004).

Modification of N transfer pathways under management strategies

Management strategies, for example grazing and cover crop incorporation, were simulated in the model system to quantify changing N transfer compared to fertilisation only. Defoliation, which simulated grazing, reduced N translocations between compartments, and overall uptake into the plant soil system. Defoliation was hypothesised to result in root decomposition due to plant death, increasing clover-derived N availability and subsequently N transfer to companion plants. Rather than increasing N transfer to ryegrass through decomposition of roots after plant death, defoliation resulted in a small decrease in plant N transfer, and a significant decrease in N transfer to the microbial protein pool, indicating no significant root decomposition compared to the positive control. The reduction in N retention and N transfer reflected the reduced translocation of N by clover, coupled with higher N demands for regrowth, which was observed during the incubation (Del-Val and Crawley 2004). The capacity of clover to regrow while competing with ryegrass for nutrients has been previously observed, however, previous studies have also shown increased N transfer to ryegrass and the soil microbial community which was not observed (Del-Val and Crawley 2004; Ayres et al. 2007). This may be due to the young sward age and single defoliation, with N transfer shown to increase in older mixed swards following repeated defoliation (Høgh-Jensen and Schjoerring 1997; Jørgensen et al. 1999; Louarn et al. 2015). Therefore, changes in N transfer across the lifespan of a mixed sward should be accounted for in land management strategies aiming to maximise N transfer.

Decomposition of clover shoots was representative of turnover of above ground biomass, and residue incorporation from a cover crop. Clover N, released by decomposition, was a significant source of N for ryegrass due to favourable decomposition conditions (e.g., moisture, aerobic conditions, direct contact with soil, C:N ratio) (Weil and Brady 2017) and no plant regrowth was possible. The high N transfer (9.3 ± 1.7%) to ryegrass was supported by microbially-mediated decomposition, reflected in N transfer to the soil protein pool (1.79 ± 0.52%), indicating the central role the soil microbial community plays in N transfer via decomposition of shoot material. N transfer via this pathway was higher than root decomposition which was thought to be low in the defoliation treatment, as white clover shoots decompose faster than roots (Barel et al. 2019). Although N transfer was high, there was no significant biomass increase observed compared to the 15N-urea only treatments and no change in the N status of the soil, likely due to the small scale and short experimental period. Enhanced N transfer following shoot incorporation, such as from cover crops into soil, confirmed the importance of clover death and microbially-mediated decomposition, which was a major source of N to partner crops (Trannin et al. 2000). The role of cover crops in N supply to partner crops warrants further investigation, as larger scale studies have identified yield improvements for cash crops, due to N transfer from decomposition of incorporated cover crops (Ledgard 2001; Abdalla et al. 2019).

Effect of biota on N transfer

Soil biota play an important role in N transfer, both via competition with companion plants for legume-N and supporting the transformation of N through microbially-mediated decomposition. Mycorrhizal networks are thought to play an important role in promoting N transfer via CMNs (common mycorrhizal networks) and indirect uptake and translocation (Cheng and Baumgartner 2004; Wahbi et al. 2016). This pathway was enhanced by addition of mycorrhizae, however, there was no observed increase in N transfer to ryegrass coupled with decreased biomass for both clover and ryegrass. The lack of increased N transfer via mycorrhizal networks, coupled with reduced plant biomass has also been observed in other studies investigating the importance of mycorrhizal networks for N transfer (Haystead et al. 1988; Barea et al. 1989; Hodge and Fitter 2013; Wahbi et al. 2016; Ren et al. 2017). Enhanced N transfer via mycorrhizal networks has been observed with low N availability in soils, driven by a concentration gradient through hyphal links (Jalonen et al. 2009). Therefore, the higher soil N status used in this study limited the importance of clover-derived N as an N source for ryegrass and thus N transfer pathways, such as mycorrhizal networks. N transfer to the soil protein pool was also reduced, although transfer to soil was increased compared to the positive control. Although it was not possible to confirm the extent of mycorrhizal colonisation, it is suggested the addition of the mycorrhizal fungi may have disrupted the existing plant and microbial communities, reducing clover-derived 15N transfer to ryegrass via microbial pathways, and assimilation into the soil protein pool.

Clover pests, such as weevils, reduce resilience to climatic factors and infection while also increasing N transfer, by reducing the N acquisition ability of clover roots, sloughing of roots and damage to root cells (Gerard et al. 2007). This was not observed in the model system following infestation with weevil eggs, with lower N transfer to ryegrass and the soil microbial community. It is suggested any damage to roots and nodules increased N demand by the clover to repair damage, which was also observed following defoliation. This increased competition for available 15N thus reduced the availability of N for transfer to ryegrass and the soil microbial community. This was supported by increased 15N retention in clover TraC roots, suggesting re-uptake of exuded N to repair damaged roots and nodules. Furthermore, there was limited damage observed to roots and nodules, and no change in clover biomass (Goldson and Jamieson 1988; Murray and Hatch 1994; Murray et al. 2002; Gerard et al. 2007). Therefore, the length of infestation may have limited the damage to clover root, with hatching time observed to be over 11 days at 25 ºC (Johnson et al. 2010) and increased damage to clover observed in subsequent years after infestation (Gerard et al. 2007).

Reverse N transfer

N transfer from clover to ryegrass rather than the reverse direction has previously been shown to dominate in mixed swards (Høgh-Jensen and Schjoerring 2000; Rasmussen et al. 2007; Chalk et al. 2014). It was surprising to observe that N transfer from ryegrass to clover was higher than clover to ryegrass (over 100 h). The dominance of N transfer from ryegrass to clover has not been previously observed, although comparable transfer in the two directions has been observed in mixed cropping systems (Jamont et al. 2013). The higher N transfer from ryegrass to clover, and also to the soil and soil microbial community (in the RecC), reflected higher availability of 15N in ryegrass donor TraC roots, ultimately meaning more 15N was available for transfer and higher root biomass for the ryegrass donor plant. The ryegrass was more efficient, or had higher N demand, compared to the clover at utilising the applied 15N, as indicated by higher 15N retention, higher biomass and transfer of 15N from the LabC through to TraC roots and soil. Clover may have also utilised unlabelled N via N2 fixation to meet N demand, although decreased nodulation observed compared to the control experiment does not support this, and N fixation was likely suppressed with N application. Therefore, while ryegrass root exudation was lower than clover, it more quickly reflected the provided 15N source, due to higher 15N-enrichment of ryegrass donor roots, influencing the higher 15N transfer from ryegrass to clover in this model system. This interesting observation in this model system should be further investigated to consider whether sward age or relatively available soil N, shown to reduce N transfer from clover in this study, may also influence the ability of ryegrass to act as an N source in a mixed sward (Del-Val and Crawley 2004; Ayres et al. 2007).

Conclusions

N transfer from clover to ryegrass has the potential to reduce fertiliser requirements and provide economic and environmental benefits. This study used a model system to investigate specific N transfer pathways and the effect of land management on the magnitude of N transfer in a mixed clover-ryegrass pasture. Key findings were:

-

(i)

N transfer was relatively low in these model system studies using a soil from a grassland pasture with a history of frequent fertiliser application, compared to previous observations of N transfer in a clover-ryegrass pasture. Of total N transfer, 35% was derived via root exudation.

-

(ii)

The microbial community played an important role in N transfer in all treatments, via assimilation of clover derived 15N into the soil protein pool, and subsequent release for plant N supply. This confirms the utility of compound-specific 15N-SIP to elucidate the role of microbial N-cycling in this setting.

-

(iii)

Factors including previous management history and sward age must be considered when assessing the potential for N transfer. Low N transfer was observed overall due to previous N additions, and N transfer was also low following a single defoliation in this young sward. It is suggested this would increase with repeated defoliation and sward age.

-

(iv)

Decomposition of clover shoots significantly increased N transfer from clover to ryegrass, representing the use of clover as a cover crop and subsequent incorporation into soil.

-

(v)

Damage to clover (e.g. defoliation and weevils) reduced N transfer to the soil protein pool, likely due to N requirements for repair of clover roots and shoots, with plants out-competing the soil microbial community for transferred N.

-

(vi)

N transfer was bi-directional, with higher N transfer from ryegrass to clover observed on a short time scale in this model system as ryegrass was more efficient at distributing incorporated N to different portions of the plant.

Overall, quantifying the individual mechanisms for N transfer from clover to ryegrass has confirmed the relative role of N transfer pathways, particularly the role of the soil microbial community. Future studies should extend this mechanistic level of detail regarding N transfer to field settings, including quantifying N transfer as a function of soil N status, sward age and stocking density.

References

Abdalla M, Hastings A, Cheng K et al (2019) A critical review of the impacts of cover crops on nitrogen leaching, net greenhouse gas balance and crop productivity. Glob Change Biol 25:2530–2543. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14644

Adams E, Frank L (1980) Metabolism of Proline and the Hydroxyprolines. Annu Rev Biochem 49:1005–1061. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.005041

Anderson DM, Glibert PM, Burkholder JM (2002) Harmful algal blooms and eutrophication: Nutrient sources, composition, and consequences. Estuaries 25:704–726. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02804901

Asghari HR, Cavagnaro TR (2012) Arbuscular Mycorrhizas Reduce Nitrogen Loss via Leaching. PLoS ONE 7:e29825. https://doi.org/10.1371/JOURNAL.PONE.0029825

Ayres E, Dromph KM, Cook R et al (2007) The influence of below-ground herbivory and defoliation of a legume on nitrogen transfer to neighbouring plants. Funct Ecol 21:256–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2435.2006.01227.x

Bais HP, Weir TL, Perry LG et al (2006) The role of root exudates in rhizosphere interactions with plants and other organisms. Annu Rev Plant Biol 57:233–266. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105159

Barea JM, El-Atrach F, Azcon R (1989) Mycorrhiza and phosphate interactions as affecting plant development, N2-fixation, N-transfer and N-uptake from soil in legume-grass mixtures by using a 15N dilution technique. Soil Biol Biochem 21:581–589. https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(89)90133-8

Barel JM, Kuyper TW, de Boer W, de Deyn GB (2019) Plant presence reduces root and shoot litter decomposition rates of crops and wild relatives. Plant Soil. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-019-03981-7

Barraclough D (1995) 15N isotope dilution techniques to study soil nitrogen transformations and plant uptake. Fertilizer Research 42:185–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00750513

Bol R, Amelung W, Friedrich C (2004) Role of aggregate surface and core fraction in the sequestration of carbon from dung in a temperate grassland soil. Eur J Soil Sci 55:71–77. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.00582.x

Brand WA, Coplen TB (2012) Stable isotope deltas: tiny, yet robust signatures in nature. Isot Environ Health Stud 48:393–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/10256016.2012.666977

Canarini A, Kaiser C, Merchant A et al (2019) Root exudation of primary metabolites: Mechanisms and their roles in plant responses to environmental stimuli. Front Plant Sci 10

Carlsson G, Huss-Danell K (2014) Does nitrogen transfer between plants confound 15N-based quantifications of N2 fixation? Plant Soil 374:345–358. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-013-1802-1

Caspi R, Billington R, Fulcher CA et al (2018) The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res 46:D633–D639. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkx935

Chalk PM, Peoples MB, McNeill AM et al (2014) Methodologies for estimating nitrogen transfer between legumes and companion species in agro-ecosystems: A review of 15N-enriched techniques. Soil Biol Biochem 73:10–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOILBIO.2014.02.005

Charteris AF, Knowles TDJ, Michaelides K, Evershed RP (2016) Compound specific amino acid 15N stable isotope probing of nitrogen assimilation by the soil microbial biomass using gas chromatography/combustion/isotope ratio mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 30:1846–1856. https://doi.org/10.1002/RCM.7612

Cheng X, Baumgartner K (2004) Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi-mediated nitrogen transfer from vineyard cover crops to grapevines. Biol Fertil Soils 40:406–412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-004-0797-4

Chiewattanakul M, McAleer ADA, Reay MK et al (2022) Compound-specific amino acid 15N-stable isotope probing for the quantification of biological nitrogen fixation in soils. Soil Biol Biochem 169:108654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2022.108654

Corr LT, Berstan R, Evershed RP (2007a) Development of N -Acetyl Methyl Ester Derivatives for the Determination of δ13C Values of Amino Acids Using Gas Chromatography-Combustion-Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry. Anal Chem 79:9082–9090. https://doi.org/10.1021/ac071223b

Corr LT, Berstan R, Evershed RP (2007b) Optimisation of derivatisation procedures for the determination of δ13C values of amino acids by gas chromatography/combustion/isotope ratio mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 21:3759–3771. https://doi.org/10.1002/rcm.3252

Coskun D, Britto DT, Shi W, Kronzucker HJ (2017) How Plant Root Exudates Shape the Nitrogen Cycle. Trends Plant Sci 22:661–673

Dahlin AS, Stenberg M (2010) Transfer of N from red clover to perennial ryegrass in mixed stands under different cutting strategies. Eur J Agron 33:149–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EJA.2010.04.006

DEFRA (2020) The British Survey of Fertiliser Practice: Fertiliser use on farm crops for crop year 2019 FERTILISER USE ON FARM CROPS FOR CROP YEAR 2019

Del-Val E, Crawley MJ (2004) Interspecific competition and tolerance to defoliation in four grassland species. Can J Bot 82:871–877. https://doi.org/10.1139/B04-066

Elgersma A, Hassink J (1997) Effects of white clover (Trifolium repens L.) on plant and soil nitrogen and soil organic matter in mixtures with perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Plant Soil 197:177–186. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004237527970

Fowler D, Coyle M, Skiba U et al (2013) The global nitrogen cycle in the twenty-first century. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 368:20130164. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0164

Frey B, Schuepp H (1992) Transfer of symbiotically fixed nitrogen from berseem (Trifolium alexandrinum L.) to maize via vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal hyphae. New Phytol 122:447–454. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.1992.tb00072.x

Friedel JK, Scheller E (2002) Composition of hydrolysable amino acids in soil organic matter and soil microbial biomass. Soil Biol Biochem 34:315–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0038-0717(01)00185-7

Fustec J, Lesuffleur F, Mahieu S, Cliquet J-B (2010) Nitrogen rhizodeposition of legumes. A Review. Agron Sustain Dev 30:57–66. https://doi.org/10.1051/agro/2009003

Galloway JN, Leach AM, Bleeker A, Erisman JW (2013) A chronology of human understanding of the nitrogen cycle. Philos Trans Royal Soc Lond B: Biol Sci 368. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0120

Gerard PJ, Hackell DL, Bell NL (2007) Impact of clover root weevil Sitona lepidus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) larvae on herbage yield and species composition in a ryegrass-white clover sward. N Z J Agric Res 50:381–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288230709510306

Goldson SL, Jamieson PD (1988) The response of field-grown lucerne to a manipulated range of insect-induced nitrogen stresses. Ann Appl Biol 113:189–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7348.1988.tb03295.x

Gylfadóttir T, Helgadóttir Á, Høgh-Jensen H (2007) Consequences of including adapted white clover in northern European grassland: transfer and deposition of nitrogen. Plant Soil 297:93–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-007-9323-4

Harrod TR, Hogan DV (2008) The soils of North Wyke and Rowden, Revised edition of the orginal report by Harrod, T. R. 1981. Soil Survey of England and Wales (now the National Soil Resources Institue, Cranfield University, UK)

Haynes RJ (1980) Competitive Aspects of the Grass-Legume Association. Adv Agron 33:227–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2113(08)60168-6

Haystead A, Malajczuk N, Grove TS (1988) Underground transfer of nitrogen between pasture plants infected with vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol 108:417–423. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.1988.tb04182.x

Herrero M, Henderson B, Havlík P et al (2016) Greenhouse gas mitigation potentials in the livestock sector. Nat Clim Chang 6:452–461. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2925

Hewitt EJ (1966) Sand and water culture methods used in the study of plant nutrition, Revised 2n. Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux, Farnham Royal (Bucks)

Hodge A, Fitter AH (2010) Substantial nitrogen acquisition by arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi from organic material has implications for N cycling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:13754–13759. https://doi.org/10.1073/PNAS.1005874107/-/DCSUPPLEMENTAL

Hodge A, Fitter AH (2013) Microbial mediation of plant competition and community structure. Funct Ecol 27:865–875. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12002

Høgh-Jensen H (2006) The Nitrogen Transfer Between Plants: An Important but Difficult Flux to Quantify. Plant Soil 282:1–5

Høgh-Jensen H, Schjoerring JK (1997) Interactions between white clover and ryegrass under contrasting nitrogen availability: N2 fixation, N fertilizer recovery, N transfer and water use efficiency. Plant Soil 197:187–199. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004289512040

Høgh-Jensen H, Schjoerring JK (2000) Below-ground nitrogen transfer between different grassland species: Direct quantification by 15N leaf feeding compared with indirect dilution of soil 15N. Plant Soil 227:171–183. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026535401773

Ikram A, Jensen ES, Jakobsen I (1994) No significant transfer of N and P from Pueraria phaseoloides to Hevea brasiliensis via hyphal links of arbuscular mycorrhiza. Soil Biol Biochem 26:1541–1547. https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(94)90096-5

Inderjit, Weiner J (2001) Plant allelochemical interference or soil chemical ecology? Perspect Plant Ecol Evol System 4:3–12. https://doi.org/10.1078/1433-8319-00011

Inselsbacher E, Hinko-Najera Umana N, Stange FC et al (2010) Short-term competition between crop plants and soil microbes for inorganic N fertilizer. Soil Biol Biochem 42:360–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.11.019

Jalonen R, Nygren P, Sierra J (2009) Transfer of nitrogen from a tropical legume tree to an associated fodder grass via root exudation and common mycelial networks. 32:1366–1376.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02004.x

Jamont M, Piva G, Fustec J (2013) Sharing N resources in the early growth of rapeseed intercropped with faba bean: does N transfer matter? Plant Soil 371:641–653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-013-1712-2

Jensen ES (1996) Barley uptake of N deposited in the rhizosphere of associated field pea. Soil Biol Biochem 28:159–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(95)00134-4

Johansen A, Jensen ES (1996) Transfer of N and P from intact or decomposing roots of pea to barley interconnected by an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus. Soil Biol Biochem 28:73–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(95)00117-4

Johnson SN, Gregory PJ, McNicol JW et al (2010) Effects of soil conditions and drought on egg hatching and larval survival of the clover root weevil (Sitona lepidus). Appl Soil Ecol 44:75–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2009.10.002

Jones DL, Willett VB (2006) Experimental evaluation of methods to quantify dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) in soil. Soil Biol Biochem 38:991–999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2005.08.012

Jørgensen FV, Jensen ES, Schjoerring JK (1999) Dinitrogen fixation in white clover grown in pure stand and mixture with ryegrass estimated by the immobilized 15N isotope dilution method. Plant Soil 208:293–305. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004533430467

Knowles TDJ, Chadwick DR, Bol R, Evershed RP (2010) Tracing the rate and extent of N and C flow from 13C,15N-glycine and glutamate into individual de novo synthesised soil amino acids. Org Geochem 41:1259–1268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orggeochem.2010.09.003

Kurppa M, Leblanc HA, Nygren P (2010) Detection of nitrogen transfer from N2-fixing shade trees to cacao saplings in 15N labelled soil: Ecological and experimental considerations. Agrofor Syst 80:223–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-010-9327-6

Ledgard SF (2001) Nitrogen cycling in low input legume-based agriculture, with emphasis on legume/grass pastures. Plant Soil 228:43–59. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004810620983

Ledgard SF, Steele KW (1992) Biological nitrogen fixation in mixed legume/grass pastures. Plant Soil 141:137–153

Ledgard SF, Freney JR, Simpson JR (1985) Assessing nitrogen transfer from legumes to associated grasses. Soil Biol Biochem 17:575–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(85)90028-8

Lesuffleur F, Salon C, Jeudy C, Cliquet JB (2013) Use of a 15N2 labelling technique to estimate exudation by white clover and transfer to companion ryegrass of symbiotically fixed N. Plant Soil 369:187–197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-012-1562-3

Louarn G, Pereira-Lopès E, Fustec J et al (2015) The amounts and dynamics of nitrogen transfer to grasses differ in alfalfa and white clover-based grass-legume mixtures as a result of rooting strategies and rhizodeposit quality. Plant Soil 389:289–305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-014-2354-8

Mariotti A (1983) Atmospheric nitrogen is a reliable standard for natural 15N abundance measurements. Nature 303:685–687. https://doi.org/10.1038/303685a0

Marschner P, Rumberger A (2004) Rapid changes in the rhizosphere bacterial community structure during re-colonization of sterilized soil. Biol Fertil Soils 40:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-004-0736-4

Martin RC, Voldeng HD, Smith DL (1991) Nitrogen transfer from nodulating soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.], to corn (Zea mays L.) and non-nodulating soybean in intercrops: direct 15N labelling methods. New Phytol 117:233–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.1991.tb04904.x

Meng L, Zhang A, Wang F et al (2015) Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and rhizobium facilitate nitrogen uptake and transfer in soybean/maize intercropping system. Front Plant Sci 6:1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPLS.2015.00339/BIBTEX

Merbach W, Mirus E, Knof G et al (1999) Release of carbon and nitrogen compounds by plant roots and their possible ecological importance. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 162:373–383

Metges CC, Petzke KJ (1997) Measurement of 15N/14N Isotopic Composition in Individual Plasma Free Amino Acids of Human Adults at Natural Abundance by Gas Chromatography-Combustion Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry. Anal Biochem 247:158–164. https://doi.org/10.1006/abio.1997.2037

Moyer-Henry KA, Burton JW, Israel DW, Rufty TW (2006) Nitrogen Transfer Between Plants: A 15N Natural Abundance Study with Crop and Weed Species. Plant Soil 282:7–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-005-3081-y

Murray PJ, Clements RO (1998) Transfer of nitrogen between clover and wheat: Effect of root herbivory. Eur J Soil Biol 34:25–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1164-5563(99)80003-X

Murray PJ, Hatch DJ (1994) Sitona weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) as agents for rapid transfer of nitrogen from white clover (Trifolium repens L.) to perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.). Ann Appl Biol 125:29–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-7348.1994.tb04943.x

Murray PJ, Dawson LA, Grayston SJ (2002) Influence of root herbivory on growth response and carbon assimilation by white clover plants. Appl Soil Ecol 20:97–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0929-1393(02)00014-8

Näsholm T, Kielland K, Ganeteg U (2009) Uptake of organic nitrogen by plants. New Phytol 182:31–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02751.x

Nelson DL, Cox MM (2017) Biosynthesis of amino acids, nucleotides, and related molecules. In: Nelson DL, Cox MM, Lehninger AL (eds) Lehninger principles of biochemistry, Seventh ed. pp 881–928

Orr RJ, Murray PJ, Eyles CJ et al (2016) The North Wyke Farm Platform: effect of temperate grassland farming systems on soil moisture contents, runoff and associated water quality dynamics. Eur J Soil Sci 67:374–385. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejss.12350

Parton W, Silver WL, Burke IC et al (2007) Global-scale similarities in nitrogen release patterns during long-term decomposition. Science 315:361–364. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1134853

Paynel F, Cliquet JB (2003) N transfer from white clover to perennial ryegrass, via exudation of nitrogenous compounds. Agronomie 23:503–510. https://doi.org/10.1051/agro:2003022

Paynel F, Murray PJ, Bernard Cliquet J (2001) Root exudates: A pathway for short-term N transfer from clover and ryegrass. Plant Soil 229:235–243. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004877214831

Paynel F, Lesuffleur F, Bigot J et al (2008) A study of 15N transfer between legumes and grasses. Agron Sustain Dev 28:281–290. https://doi.org/10.1051/agro:2007061

Peoples MB, Chalk PM, Unkovich MJ, Boddey RM (2015) Can differences in 15N natural abundance be used to quantify the transfer of nitrogen from legumes to neighbouring non-legume plant species? Soil Biol Biochem 87:97–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOILBIO.2015.04.010

Peukert S, Bol R, Roberts W et al (2012) Understanding spatial variability of soil properties: a key step in establishing field- to farm-scale agro-ecosystem experiments. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 26:2413–2421. https://doi.org/10.1002/rcm.6336

R Core Team (2021) R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria

Rasmussen J, Eriksen J, Jensen ES et al (2007) In situ carbon and nitrogen dynamics in ryegrass–clover mixtures: Transfers, deposition and leaching. Soil Biol Biochem 39:804–815. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOILBIO.2006.10.004

Ray DK, Mueller ND, West PC, Foley JA (2013) Yield Trends Are Insufficient to Double Global Crop Production by 2050. PLoS ONE 8:e66428. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066428

Ren H, Gao T, Hu J, Yang G (2017) The effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and root interaction on the competition between Trifolium repens and Lolium perenne. PeerJ 2017. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4183

Roberts P, Jones DL (2008) Critical evaluation of methods for determining total protein in soil solution. Soil Biol Biochem 40:1485–1495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2008.01.001

Schulten H-R, Schnitzer M (1998) The chemistry of soil organic nitrogen: a review. Biol Fertil Soils 26:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003740050335

Sen S, Chalk PM (1996) Stimulation of root growth and soil nitrogen uptake by foliar application of urea to wheat and sunflower. J Agric Sci 126:127–135. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021859600073056

Sommer SG, Schjoerring JK, Denmead OT (2004) Ammonia Emission from Mineral Fertilizers and Fertilized Crops. Adv Agron 82:557–622. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2113(03)82008-4

Steinkellner S, Lendzemo V, Langer I et al (2007) Flavonoids and Strigolactones in Root Exudates as Signals in Symbiotic and Pathogenic Plant-Fungus Interactions. Molecules 12:1290–1306. https://doi.org/10.3390/12071290

Ta TC, Faris MA (1987) Species variation in the fixation and transfer of nitrogen from legumes to associated grasses. Plant Soil 98:265–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02374830

Teste FP, Veneklaas EJ, Dixon KW, Lambers H (2015) Is nitrogen transfer among plants enhanced by contrasting nutrient-acquisition strategies? Plant, Cell Environ 38:50–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/pce.12367

Thilakarathna MS, McElroy MS, Chapagain T et al (2016) Belowground nitrogen transfer from legumes to non-legumes under managed herbaceous cropping systems. A Review. Agron Sustain Dev 36:58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-016-0396-4

Tilman D, Balzer C, Hill J, Befort BL (2011) Global food demand and the sustainable intensification of agriculture. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:20260–20264. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1116437108

Trannin WS, Urquiaga S, Guerra G et al (2000) Interspecies competition and N transfer in a tropical grass-legume mixture. Biol Fertil Soils 32:441–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s003740000271

van Kessel C, Singleton PW, Hoben HJ (1985) Enhanced N-Transfer from a Soybean to Maize by Vesicular Arbuscular Mycorrhizal (VAM) Fungi. Plant Physiol 79:562–563. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.79.2.562

van Kessel C, Clough T, van Groenigen JW (2009) Dissolved Organic Nitrogen: An Overlooked Pathway of Nitrogen Loss from Agricultural Systems? J Environ Qual 38:393. https://doi.org/10.2134/jeq2008.0277

Viera-Vargas MS, Souto CM, Urquiaga S, Boddey RM (1995) Quantification of the contribution of N2 fixation to tropical forage legumes and transfer to associated grass. Soil Biol Biochem 27:1193–1200. https://doi.org/10.1016/0038-0717(95)00022-7

Vitousek PM, Naylor R, Crews T et al (2009) Agriculture. Nutrient imbalances in agricultural development. Science 324:1519–1520. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1170261

Wahbi S, Maghraoui T, Hafidi M et al (2016) Enhanced transfer of biologically fixed N from faba bean to intercropped wheat through mycorrhizal symbiosis. Appl Soil Ecol 107:91–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APSOIL.2016.05.008

Weil RR, Brady NC (2017) Nitrogen and sulfur economy of soils. In: Fox D (ed) The Nature and Properties of Soils, 15th edn. Pearson Education Limited, Essex, pp 601–660

Wichern F, Eberhardt E, Mayer J et al (2008) Nitrogen rhizodeposition in agricultural crops: Methods, estimates and future prospects. Soil Biol Biochem 40:30–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOILBIO.2007.08.010

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the NERC for partial funding of the National Environmental Isotope Facility (NEIF; contract no. NE/V003917/1) and the HEFCE SRIF and the University of Bristol for funding the GC-IRMS capabilities. Rothamsted Research are thanked for providing soils from the North Wyke Farm Platform for incubation experiments, and Liz Dixon at North Wyke is thanked for support with 15N analyses of soil and plant biomass.

Funding

This work was conducted as part of K. Pears’ PhD studies at University of Bristol funded through the SWBio DTP BBSRC. Compound-specific 15N-analyses were conducted at the National Environmental Isotope Facility Bristol laboratory (NEIF-B) at University of Bristol (NE/S011587/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

We have no conflicts of interest nor competing interests.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Matthew D. Denton.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Reay, M.K., Pears, K.A., Kuhl, A. et al. Mechanisms of nitrogen transfer in a model clover-ryegrass pasture: a 15N-tracer approach. Plant Soil 480, 369–389 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-022-05585-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-022-05585-0