Abstract

Background and aims

Soil organic carbon (SOC) accrual is central to the discussion on active atmospheric CO2 removal strategies, but it requires a clear understanding of the mechanisms driving new SOC formation. SOC is formed from the decomposition of above- and below-ground plant inputs, yet their accurate quantification remains a major challenge. In the current study the in-growth soil core and δ13C methods were combined to quantify the net C input from single or combined above- and below-ground parts of a poplar (Populus) bioenergy plantation.

Methods

Three different mesh sizes were used for the in-growth cores in four different treatments designed to estimate the relative contributions of above-ground litter fall, fine roots and mycorrhizae (C3 input from the poplar) to the new C formation in cores filled with a C4 soil, by applying a mass balance equation.

Results

Soil C formation was higher in the treatments with roots as compared to the treatments with above-ground C inputs only (29 vs 16 g C m−2), despite the disproportionally lower root inputs as compared to above-ground C inputs (34 vs 175 g C m−2 y−1). Soil C formation from different sources (above- and below-ground) was additive; i.e. the observed soil C formation in the combined treatment was the sum of those in the single soil C input treatments. As a result, below-ground C-inputs had a high conversion efficiency to SOC of 76%. Above-ground plant inputs had a very low SOC formation efficiency of 9%, and were presumably mainly mineralized by microorganisms.

Conclusion

The higher soil C accumulation rates from below-ground C inputs are particularly important in bioenergy plantations where the above-ground biomass is frequently removed for biomass and energy production.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Soils are the largest reservoir of organic carbon (C) in terrestrial ecosystems, containing three times more C than the vegetation that they support (Batjes 1996). As such, they represent a potential sink for the anthropogenic emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) that threaten the stability of the Earth’s climate. Several studies have focused on management practices that could increase the accrual of C in soils (Dimitriou et al. 2012; Follett and Reed 2010; Luo et al. 2010; Powlson et al. 2011), and a new framework for the formation and stabilization of soil organic carbon (SOC) has been recently established (Cotrufo et al. 2015, 2013; Lehmann and Kleber 2015; Schmidt et al. 2011). Nevertheless, our understanding of the key processes and drivers of SOC accrual remains limited. The relative contribution to SOC formation of above-ground versus below-ground plant parts has gained interest in research, as it is a key factor that drives SOC formation (Kätterer et al. 2011; Kong and Six 2010; McCormack et al. 2015; Rasse et al. 2005; Wardle et al. 2004).

All terrestrial ecosystems consist of above-ground and below-ground components, with the annual above-ground litter fall most often representing the largest C input to the soil (Berhongaray et al. 2017; Bolinder et al. 2007; Grace et al. 2006). For many decades research on SOC relied on the assumption that above-ground plant litter is the principal source of SOC. Moreover, in most SOC models above- and below-ground C inputs have the same potential to form stabilized SOC – such as the AMG model (Andriulo et al. 1999); the Roth-C model, (Coleman and Jenkinson 1996); and the Century model (Parton et al. 1994). These assumptions have, however, been questioned and recent studies demonstrated that below-ground C inputs have a relatively larger influence on SOC formation than above-ground C inputs (Clemmensen et al. 2013; Rasse et al. 2005). Understanding the single and combined contribution of above- versus below-ground C inputs is particularly important in bioenergy plantations, where the above-ground biomass is regularly removed for energy production, while SOC storage needs to be sustained to achieve a neutral C footprint of the system and to protect its long-term productivity.

Although forest ecosystems (forested and afforested areas), and in particular fast-growing, highly productive plantations, have been highly recommended to restore C stocks in the soil (Smith 2004), only few studies used tracers to elucidate the effect of the different plant sources of soil C in these tree-based ecosystems (Kuzyakov and Domanski 2000). A couple of studies have quantified SOC formation in tree plantations using isotopes (Alberti et al. 2015; Del Galdo et al. 2003; Martinez et al. 2016), but none of these differentiated between above- versus below-ground inputs. While Bird and Torn (2006) examined the difference of needle versus root decomposition in SOM formation, their study focused on the litter chemistry independent of the input rates. A better understanding of the contribution of above-ground and below-ground plant parts to the accumulation of SOC is therefore needed to improve management practices that can maximize C storage in the soil.

Above-ground C inputs in the soil include leaf and woody tissue litter. These C inputs are related to the above-ground biomass production (and yield), and can easily be measured with standard approaches. On the other hand, below-ground C inputs can be defined as root mortality occurring over a specified period of time, plus all C allocated below-ground by plants to root-associated organisms such as mycorrhizae, or rhizo-deposits (root sloughing and exudates). The quantification of this below-ground C input is complex, but crucial as e.g. the inputs via mycorrhizae can exceed the input via leaf litter and fine root turnover (Godbold et al. 2006). Therefore this study aims to quantify: (i) the C inputs of below-ground (roots and their exudates, mycorrhizal mycelia) and above-ground tissues (leaf and wood litter), and (ii) their relative contribution to new SOC formation individually or in combination. We hypothesize that the single effects of above- and below-ground inputs on SOC formation are additive, such that their combined application yields the same SOC formation as the sum of the single applications. We used the changes in the 13C signature of SOC in in-growth cores filled with C4 soil in a C3 poplar plantation, applying a methodology that has been successfully used before (Alberti et al. 2015; Cotrufo et al. 2011; Martinez et al. 2016), to estimate the relative contributions of above-ground and below-ground plant parts to the bulk SOC pool. Additionally we manipulated mesh sizes to assess the individual versus combined contributions to SOC of the different plant inputs.

Materials and methods

Study site and plantation establishment

The experimental field site was located in Lochristi, Belgium (51o06’N, 03o51’E) and consisted of an operational short-rotation woody crop (SRWC) poplar (Populus spp.) plantation for bioenergy production. The average annual temperature at the site is 9.5 °C and the average annual precipitation is 726 mm (Royal Meteorological Institute of Belgium; www.rmi.be). The monthly soil temperature and precipitation during the four growing seasons of the experiment are provided in the Supplementary Material. The region is pedologically described as a sandy region and has poor natural drainage; the soil type according to the World Reference Base (WRB) is an Anthrosol (FAO, 2014). A detailed soil analysis prior to the establishment of the plantation (in 2010) characterized the soil type as sandy in texture (Verlinden et al. 2013). Further details on the chemical analysis and soil variables of the experimental site are presented in Table 1 (see also Broeckx et al. 2012). The site extended over an area of 18.4 ha, and was previously managed partially as: (i) cropland (alternating crops, including ryegrass, wheat, potatoes, beets, and corn), and (ii) extensively grazed pasture. In March 2010 the entire field was ploughed down to 60 cm depth, and in April 2010 the area was planted with 25 cm long dormant and unrooted cuttings from 12 poplar genotypes in mono-genotypic blocks in a double-row planting scheme with a commercial leek planter at an overall density of 8000 trees per ha (Broeckx et al. 2012). The plantation was managed in two-year rotations, and coppiced in February 2012 (after growing seasons 2010 and 2011) as well as in February 2014 (after growing seasons 2012 and 2013). For more information on the site and its management, see Broeckx et al. (2012) and Verlinden et al. (2015a).

In-growth cores and treatments

The use of natural abundance 13C is a very useful method for quantifying the relative contributions of two C sources to SOC, as well as the SOC turnover rate, when there is a significant difference in 13C between the sources (Balesdent et al. 1988). This opportunity arises from the different discrimination of 13CO2 versus 12CO2 during photosynthesis by plants with different photosynthetic strategies (C3 or C4). Changes in the vegetation from C3 to C4 or vice versa, alter the 13C signature of soil C inputs, and thus allow an estimate of the newly formed SOC versus the ‘old’ SOC. We used the in-growth soil core 13C technique (Cotrufo et al. 2011; Godbold et al. 2006) to discriminate SOC inputs from the C3 vegetation (i.e., the poplar SRWC plantation, further referred as C3 inputs) into the soil (Fig. 1). We used a soil with a very distinct C4 plant signature (further referred as C4 soil), collected from the top soil of the Pawnee National Grasslands in Colorado, USA. The vegetation is a C4-C3 short grass steppe, with Botuloua gracilis as the dominating grass. The C4 soil is a Chernozem (FAO, 2014) formed in alluvium, wind-reworked alluvium and loess. In December 2009, 28 rubber totes of 68 L were filled with the topsoil of this short grass steppe located 140 km northeast of Fort Collins (Colorado, USA). Approximately 2.5 tons of soil were shipped to Belgium in January 2010. After arrival at the campus of the University of Antwerp, in April 2010, the C4 soil was sterilized with an electric soil sterilizer (model SS-60R, Pro-grow Supply Corp, Brookfield, WI, USA). Following sterilization the soil was sieved using a 5 mm mesh to remove most roots and stones, and left to air dry. In November–December 2010, the sieved C4 soil was inserted in the in-growth cores (8.5 cm diameter, 40 cm depth). The amount of soil in each in-growth core was previously determined to mimic the soil bulk density of the site (average bulk density = 1.42 kg dm−3; Berhongaray et al. 2017). During the in-growth core installation in the soil of the SRWC plantation seven samples were randomly taken from the C4 soil, representing the initial C4 soil (Soil 0). The samples were oven-dried at 40 °C in the laboratory and conserved in plastic bags until analysis.

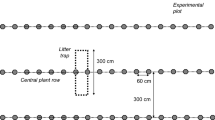

Three different mesh sizes were used for the in-growth cores in four different treatments (Fig. 2). These treatments were designed to estimate the relative contributions of above-ground litter fall, of fine roots and of mycorrhizae (C3 input from the poplar crop) to the new SOC formation in the C4 soil.

-

Treatment I (T-I, all inputs): a mesh size of 2 mm allowed inputs from fine roots and mycorrhizal mycelia. The opening on the top also allowed inputs from above-ground (leaf and wood litter).

-

Treatment II (T-II, exclusion of above-ground input): the same mesh size (2 mm) as in Treatment I, but a 10 mm mesh net on top of the in-growth core and the periodic removal of above-ground litter from the top prohibited above-ground inputs. Care was taken to avoid above-ground inputs. The cores were visited every month during the leaf fall season (from August to November) and every 2–3 months during the rest of the year. All litter was removed from the top of the nets; if any above-ground input went through the net it was removed from the in-growth core.

-

Treatment III (T-III, root exclusion): an intermediate mesh size (37 μm) excluded the penetration of roots, but allowed the in-growth of mycorrhizal mycelia. Above-ground inputs were also permitted.

-

Treatment IV (T-IV, only above-ground): the smallest mesh size (5 μm) excluded the in-growth of roots and mycorrhizal mycelia, allowing only the inputs of above-ground litter.

To generate some variation in C input conditions, these four in-growth treatments were applied in two genetically and phenotypically contrasting poplar genotypes (i.e. Koster: Populus deltoides x P. nigra, and Skado: P. trichocarpa x P. maximowiczii). A description of the morphological, physiological and productivity differences between the two poplar genotypes (Koster and Skado) has been previously reported (Broeckx et al. 2012; Verlinden et al. 2015a). The in-growth cores were installed for a period of two years (2011–2012; two growing seasons), and a period of three years (2011, 2012 and 2013; three growing seasons) in both of the two former land uses (pasture and cropland). The C4 soil in-growth cores were replicated five times per genotype, per former land use, per treatment and per period, yielding a total of 160 in-growth cores. See the Supplementary Material for further details on the planting scheme and the treatment plan.

The C4 in-growth cores were placed in the narrow rows of the double-row plantation, where the root biomass was higher (Berhongaray et al. 2013b) to have a higher chance that roots grew inside the in-growth cores, following earlier recommendations (Martinez et al. 2016). The differences in root biomass inside and just outside the in-growth cores were accounted for in the calculations of the C inputs (see below Eq. 2). Despite the different weed control measures during the first rotation, common agricultural weeds remained abundant within the plantation. Weed presence was higher at the early stage of the plantation, but decreased when poplars became dominant, especially after the coppice in 2012. All weeds growing near the in-growth cores were removed by hand to avoid any bias from weed C inputs.

Sampling and sample manipulation

Soil samples were taken in the middle of the in-growth core with a bulk density corer (5 cm diameter and 5 cm length; Eijkelkamp Agrisearch equipment, The Netherlands) at 5 cm increments from the soil surface to 35 cm depth. To obtain a good representation of the vertical distribution of SOC formation, while avoiding unmanagable sample numbers, the 0–5 cm, 10–15 cm and 30–35 cm samples were analyzed, while the rest of the soil depth samples were discarded. The very top and the bottom of the C4 soil sample were scratched away, and discarded to avoid contamination from the surrounding C3 soil. In total 480 soil samples were taken considering the 160 in-growth cores and the three sampling depths (2 genotypes × 2 land uses × 4 treatments × 3 depths × 2 periods × 5 replicates = 480 samples).

The samples were brought to the laboratory in plastic bags. Each soil sample was weighed (fresh weight = FW), dried in a drying oven at 45 °C for seven days for determination of dry weight (DW), and bulk density. After weighing the samples were sieved using a 2 mm mesh to separate the roots (the soil is stone-free), and then pulverized in a mill (model ZM 200, Retsch, Germany). Subsamples of all soil samples, as well as of those collected prior to incubation (soil 0) were shipped to the EcoCore Analytical Facility, Colorado State University (Fort Collins, Colorado, USA) for the determination of C% and δ13C by an Elemental Analyzer-Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometer (EA-IRMS model NA1500, Carlo Erba, Italy coupled to a VG Isochrom continuous flow IRMS, Isoprime Inc., UK). Each sample was acid fumigated, to eliminate any carbonate (Harris et al. 2001) and analyzed in duplicate. In case of major differences between the two results (more than 5% difference), a third and eventually a fourth analytical replicate was performed. This procedure increased the confidence of the δ13C value of the sample. From the C mass fractions and the bulk density, the SOC pool for each depth interval was calculated.

C3 litter inputs

Above-ground plant parts

During each of the three sampled growing seasons (2011, 2012, 2013) leaf litter production was quantified in the plantation using plastic baskets. Three replicate plastic baskets of 0.57 m × 0.39 m were placed in two plots under the canopy of both genotypes within each former land use type (n = 24). Litter fall was regularly collected every year (2011, 2012, 2013) from mid-August till complete leaf abscission (in November or December depending on genotype and growing season). Baskets were emptied every one to two weeks, and collected leaves were transported to the laboratory where they were oven dried at 70 °C and weighed for dry mass determination.

Woody litter was estimated from samples collected at the field site in early March 2012 after the coppice of the plantation. All woody biomass material was collected from the soil surface on 16 areas of 1 m2. The collected biomass material was transported to the laboratory and dried in a drying oven at 60–70 °C until constant weight. Dried leaf and wood litter samples were ground and analyzed by dry combustion with an NC element analyzer (model NC-2100 Element Analyzer, Carlo Erba Instruments, Italy) and later expressed as C inputs using the C mass fraction. More details on the woody sampling procedure were previously published (Berhongaray et al. (2017). Leaf and wood C isotope data were obtained from Verlinden et al. (2015a, b) for both genotypes at the same plantation. An average isotopic composition of above-ground litter was calculated using the C isotope composition and the relative proportion of the different sources to the total litter input.

Roots

The fine root (Ø <2 mm) biomass and productivity were annually estimated for the field site and previously published (Berhongaray et al. 2017). Briefly, from February 2011 to December 2013 intact soil samples were taken – adjacent to the in-growth cores – every 2–3 weeks (from 10 to 20 samples, except for the winter when the sampling intensity was decreased) using an 8 cm diameter × 15 cm deep hand-driven corer (Eijkelkamp Agrisearch equipment, The Netherlands) in both genotypes and former land uses. All roots were picked from the sample by hand and sorted in two different diameter classes (<2 mm and > 2 mm). The roots were also sorted in dead (necromass) and living (biomass) roots based on the darker colour and the poorer cohesion between the cortex and the periderm of the dead roots. It was possible that some roots were not picked from the sample, especially biomass of very fine roots. We minimized any underestimation of root biomass by correcting the root biomass to the picking duration time as explained in Berhongaray et al. (2013c). Following washing, fine roots were oven dried at 70 °C for one to four days to determine the standing (fine) root biomass. Dried biomass from roots was ground and analyzed by dry combustion with an element analyzer (NC-2100 element analyzer, Carlo Erba Instruments, Italy) and converted to C mass using the average C mass fraction (C%) and expressed in g C m−2. These data were used for estimations of fine root production, mortality and C input. More details on the procedure of root collection and on data processing can be found in Berhongaray et al. (2013b, 2015, 2017). Sub-samples of root material from the different genotypes, land uses and years (n = 36) were ground to fine powder and analyzed for C% and δ13C by EA-IRMS (Carlo Erba Instruments NA1500, Italy coupled to VG Isochrom, EcoCore Analytical Facility).

Root exudation (including root sloughing, i.e. rhizodeposition) was also considered for the root C input estimations. Root exudation represented an annual input of fresh root C into soils that was estimated as a proportion of the C allocation to roots (Pausch and Kuzyakov 2018). Net root exudates are defined as the part of the C that remains in the soil after microbial respiration. A recent review accounted that these root exudates are about 30% of the net C remaining in the roots (i.e. root production)(Pausch and Kuzyakov 2018). We therefore used the annual fine root production estimates to calculate the net input of C from root exudates into the soil (root exudation from here on) as follows:

The installation of the in-growth cores in the SRWC field with a different soil (the C4 soil) affected root growth inside the in-growth cores (see below in Results section). To correct for this issue the C input was multiplied by the ratio of root biomass in the C4 soil to the root biomass in the C3 soil as follows:

Since the in-growth cores were installed eight months after planting, the root biomass at the time of the in-growth core installation time was discounted from the final biomass in the C3 soil. Root C inputs were estimated for each depth interval (0–5 cm; 10–15 cm and 30–35 cm) using available root distribution data (Berhongaray et al. 2015), a cumulative root fraction model (Jackson et al. 1996) and the total root C input (Berhongaray et al. 2017).

Partitioning of the plant derived soil organic carbon

New SOC originating from above- and below-ground inputs was determined using the two end-member mixing model (Balesdent et al. 1988). The fraction (f) of SOC coming from the trees was calculated as:

where δ13CSoil sample = δ13C of the SOC at the sampling time, δ13CSoil0 = average δ13C of the SOC in the original C4 soil, and δ13CPlant = average δ13C of the plant C input. Average δ13CPlant was calculated considering the relative contribution of the different sources (leaves, wood and roots) to the total litter input for each treatment and soil depth. For example, treatment I at 0–5 cm of soil depth received inputs from above (leaves and wood litter) and from roots, while the deeper soil depths (10–15 cm and 30–35 cm) received inputs from roots only. Consequently the average δ13CPlant for the top soil was calculated by multipliying the δ13C from leaves, wood and root tissues, weighted by their relative contribution to the total C input, i.e. 70%, 20% and 10% respectively. On the other hand, for the deeper soil layers only the root δ13C was used. The new SOC (soil Cnew), or the plant-derived C in each sample was determined from the total SOC pool (soil Ctotal) and f as follows:

The partitioning of soil Cnew originating from the different sources (above-ground, roots and mycorrhizae) was estimated for each soil depth, using two approaches for the above-ground parts and the roots: the contribution in a single application, and the contribution in a combined application with above- or below-ground inputs as presented in Table 2. The efficiency of the conversion of plant-derived C into SOC, was estimated for the above- and the below-ground C inputs as the ratio between new SOC and plant C-inputs, following Cotrufo et al. (2015).

Statistical analyses

The fraction (f) and absolute amounts of plant-derived C in the soil were calculated for each of the 96 experimental factor combinations (genotypes, former land uses, input treatments, soil depths and periods) using the average and standard deviation values. The numerical Monte Carlo method (MCS) was used for the purpose of propagating uncertainties in the estimations. A normal distribution function was chosen for each variable. When necessary a truncated normal distribution was used to avoid negative values of biomass or of %C. The run of the MCS included the stochastic sampling of 1000 iterations for each input variable. More details about the MCS can be found in the Supplementary Material. The C accumulation was divided by the time period and expresed as C accumulation rate (g C m−2 y−1). A factorial analysis of variance was carried out to evaluate the individual and aggregate effects of the factors (fixed effects: genotype, former land use, input treatment, soil depth) on the plant derived C. Since variables not always displayed a normal distribution (see Supplementary Material), the data were also analyzed by a Kruskal-Wallis test. Regression and correlation analyses were performed to identify relationships among variables, the significance of which was tested by an F test (P ≤ 0.05). Further details on the statistical analyses of the genotypes, former land uses, and input treatments can be found in the Supplementary Material. The software InfoStat (Di Rienzo et al. 2011) was used for all analyses.

Results

The highest biomass of fine roots over the examined soil profile occurred in the upper 5 cm layer of the soil (Fig. 3, left panel). Root biomass was lower in the in-growth cores than in the soil outside the in-growth cores: 6% lower when averaged over the three depths, but only 1% lower in the top soil layer, and up to 13% lower in the deeper layers.

Left panel = Distribution of root biomass with soil depth in the C4 soil of the in-growth cores and at the field site and the C3 soil adjacent to the in-growth cores. Right panel = Mean annual above-ground (hatched bar) and root carbon (C) inputs (black bars), including root exudation, into the C4 in-growth cores as a function of soil depth. Average values expressed in amounts of C. Fine horizontal lines represent the range of C inputs for each depth (minimum and maximum C input) across the different combinations of genotypes, former land-uses and time periods considered. DM = dry mass, A = above-ground

Above-ground litter represented the largest C input to the soil (p < 0.05; Fig. 3). It was six times larger than the total input from roots in the top soil (0–5 cm depth). When the entire soil profile (up to 60 cm depth) was considered, above-ground inputs were 30% higher than below-ground inputs. Leaf fall represented 86% of the above-ground input, and wood litter from harvest losses represented a minor proportion, although statistically significant differences between genotypes, former land uses and years were observed (Berhongaray et al. 2017). Root mortality represented (on average) 78% of the estimated below-ground C inputs, while root exudates contributed 22%. This proportional contribution of the root exudates depended on the assumption of Eq. 1, but could hinge between 11% and 43% when reducing or doubling the exudation rates (see details in the sensitivity analysis in the Supplementary Material 4). An increase of total C inputs (above- + below-ground) of about 50% was observed the year after harvest (Fig. 4), due to an increase in root mortality (Berhongaray et al. 2015) and – to a smaller extent – in wood litter (Berhongaray et al. 2013a). The total C inputs were 60% higher in the genotype Skado as compared to Koster (Fig. 4), explained by the higher leaf litter, root biomass and general productivity (60% higher, Mg ha−1 y−1 of dry matter) of genotype Skado (Berhongaray et al. 2017; Verlinden et al. 2015a).

The plant isotopic composition (δ13C) significantly varied among genotypes, land uses and tree parts (Table 3; p < 0.05). In general, it was higher in genotype Skado than in Koster, higher in the former pasture than in the cropland, and higher in wood tissues than in leaves and fine roots. As a consequence, the isotopic composition of the C4-soil evolved differently over time across the different treatments (Fig. 5). During the three years that the in-growth cores were in the soil, the δ13C signature of the C4 soil decreased in the top layer from an initial value of −16.9‰, at a rate of −0.81‰ y−1 in T-I (all inputs), −0.69‰ y−1 in T-II (above-ground exclusion), and − 0.45‰ y−1 in T-III (root exclusion) and T-IV (below-ground exclusion) (p < 0.05). Small decreases in the δ13C were detected in the deeper soil layers, with no differences between treatments T-I, T-II and T-III, with an average annual decrease of −0.15 ‰ y−1, which differed from T-IV that had an average annual decrease of −0.05‰ y−1. This vertical distribution pattern of δ13C followed the depth pattern of C input into the soil (Fig. 3). Significant differences were also detected between genotypes (p < 0.05), but not between former land uses. The δ13C depletion rate was higher in the first two years as compared to the third year (Fig. 6), which could be explained by the higher C input during the year after harvest (Fig. 4). The total soil C concentration increased in the top layer from 0.73% in 2010 to 0.87% in 2014 (p < 0.01), being higher in genotype Skado and the former cropland land use as compared to Koster and pasture (p < 0.01).

Average plant δ13C (in ‰) as well as initial and final – after three years – soil δ13C (in ‰; left panel) and soil C concentration (in %; right panel) across genotypes and land uses for each treatment at different soil depths. Plant δ13C was calculated considering the relative contribution of the different sources (leaves, wood and roots) to the total litter input. Soil0 represents the initial C4 soil δ13C and C %; T-I, T-II, T-III and T-IV are the four treatments as explained in Fig. 2. Horizontal bars represent the standard deviation

Change of average soil δ13C (in ‰) over time for each treatment, genotype (Skado, Koster) and former land use in the top soil (0–5 cm). T-I, T-II, T-III and T-IV refer to the four treatments as explained in Fig. 2. Vertical bars represent standard errors

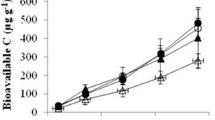

The plant derived C accumulation rate was significantly different among treatments and between genotypes (ANOVA; p < 0.05), but not significantly different between former land uses (see SM 5). Carbon accumulated at all three soil depths in the treatments in which root growth was allowed (T-I and T-II; Table 4). Treatments that received mainly above-ground inputs (T-III and T-IV) accumulated new C in the top soil layer only, with no statistically significant C accumulation in the deeper layers. The same was valid for the mycorrhizae; their contribution to soil C formation was found in the top soil layer only. There were no significant differences in the soil C accumulation from the single or combined application of above-ground and root C inputs (Table 5); therefore, they were averaged and treated as replicates from here on. Despite their lower C-input rate compared to aboveground litter, roots dominated the contributions to the soil C formation at all depths, especially deeper in the soil (Table 6).

In terms of efficiency of SOC stabilization, i.e., normalized to plant C inputs, root-derived C contributed more efficiently to new SOC formation than above-ground litter (Fig. 7). Fitting the regression through the origin (zero intercept), soil C increased at a rate of 0.76 g g−1 of below-ground C inputs, while soil C only increased at a rate of 0.09 g g−1 of above-ground C inputs.

Annual accumulation of plant-derived organic carbon in the soil (new soil-C), as estimated from 13C natural abundances during the cultivation of a short rotation coppice plantation of poplar, from two tree components: only above-ground C inputs (leaf and wood litter; open circles), and only the below-ground C inputs (roots and mycorrhizae; solid circles). Above-ground data from the top soil layer (0–5 cm) and below-ground data from three soil layers (0–5 cm, 10–15 cm, 30–35 cm). Each data point represents to an average of genotype*land-use*per sampling-year. The dotted line represents the 1:1 relationship

Discussion

Roots and soil C changes

Roots dominated the formation of new SOC at all depths, especially deeper in the soil where roots were the only input whose C was being converted to SOC. Around 50 to 70% of stored C in forest soils in Sweden was derived from roots and root-associated microorganisms as analyzed with bomb 14C data (Clemmensen et al. 2013). A long-term crop experiment in Sweden showed that root-derived SOC was about 2.3 times higher than SOC from above-ground crop residues (Kätterer et al. 2011). Our current results agree with these two studies in that most of the new SOC was derived from roots rather than from shoots and leaf litter. Carbon allocation to roots is therefore a key process that can be optimized for enhanced C sequestration (Kell 2012). Mycorrhizal fungal symbionts can develop an extensive hyphal mycelium to explore the soil and acquire nutrients, and also have a high potential to contribute to SOC formation. In experiments in Italy (Godbold et al. 2006) and USA (Phillips et al. 2012) the contribution of mycorrhizae largely exceeded the contribution from roots, and accounted for more than 60% of the new soil C. In the present study, however, the amount of new SOC originating from mycorrhizae was very low and situated only in the top layer, probably associated to the nutrients entering the soil via above-ground litter fall. The differences between our study and the afore mentioned studies might be explained by the high soil fertility at our site, as evidenced from a detailed analysis of soil nutrients at both former land-use types (Broeckx et al. 2012). This chemical soil analysis showed that our plantation was established on a very fertile soil where low mycorrhizal abundance could be expected (Treseder 2004). Although no fertilizers were applied since the establishment of the plantation, the decades of former agricultural use had rendered the soils highly enriched with phosphorus and moreover, both nitrogen deposition and groundwater nitrate concentrations were high (Zona et al. 2013).

There was a tendency for a lower soil C formation rate in the combined application of above- and below-ground C inputs as compared to the single applications, but this difference was not statistically significant at p < 0.05. The C retention efficiency (i.e. the increase of SOC per unit of C input) of residues decreases with the amount added (Shahbaz et al. 2017). Soil C accumulation was, however, observed in our study to be additive when above- and below-ground inputs were applied together (relative to single applications), confirming our hypothesis that above- and below-ground inputs do not have synergetic or antagonistic effects on SOC formation. With regard to the C cycle at the plantation, the fraction of total net primary productivity (NPP) that was retained as soil C varied from 10% to 13% (average C accumulation = 60 g C m−2 y−1; average NPP = 540 g C m−2 y−1; Verlinden et al. 2015a, b; Berhongaray et al. 2017).

Soil C changes were previously estimated for the site using a C mass-balance approach (Berhongaray et al. 2017), which combined measurements of standing biomass with litter fall and measurements of respiratory CO2 efflux. Although this approach provided reliable results in quantifying the whole ecosystem C budget, uncertainties about the contribution of different above- and below-ground C fluxes to the soil C accrual remained. Our study confirmed that below-ground C inputs have a much larger influence on SOC formation than above-ground C inputs, as previously suggested (Clemmensen et al. 2013; Rasse et al. 2005). The results showed a very high (76%) conversion efficiency of plant-produced C into SOM for the root C-inputs. This conversion efficiency was, logically, dependent on the assumed rate of root exudation (cfr. Sensitivity analysis in Supplementary Material). The sensitivity analysis showed that when the root exudation was assumed twice as high, the conversion efficiency dropped from 76% to 63%. Although much reduced, this conversion efficiency of root-derived C still remained seven-times higher than that of above-ground C inputs. This ratio of 7 was also much higher than the 2.3 ratio reported for annual crops (Kätterer et al. 2011). On the other hand, the sensitivity analysis also revealed that it was very unlikely that root exudation rates were overestimated, since lower root exudates rendered the conversion efficiency of root-derived C close to 100%, which is impossible. Furthermore, we suspect that root exudates were larger than was estimated in the current study. The root exudates were calculated using the most recent revision from Pausch and Kuzyakov (2018), but the C allocation patterns (and so the net root production and exudates) in this last mentioned study were estimated for crops and grassland species only, due to the small number of studies on trees. Our estimates of the proportion of root exudates to the total below-ground C inputs were almost three times smaller (22% vs 62%) than estimated for a poplar plantation in central Italy (Godbold et al. 2006). The lack of information and the discrepancies between experiments emphasize the importance of measuring root exudates in tree dominated crops and ecosystems.

The effect of the in-growth cores

Root biomass developed well in the in-growth cores. Their distribution along the soil profile was in line with earlier studies that showed that poplars with sufficient nutrients and water develop roots mainly in the top layer of the soil (Al Afas et al. 2008; Berhongaray et al. 2015). Although the in-growth core method is a useful method to study plant-soil relationships (Alberti et al. 2015; Cotrufo et al. 2011; Martinez et al. 2016), it has some limitations, such as achieving the same soil properties inside the core as outside. Nutrient availability, soil texture and bulk density characteristics inside the mesh bags should be comparable to the soil characteristics outside, otherwise they could affect root growth patterns inside the in-growth core (Steingrobe et al. 2000). This was hard to achieve in the current study with our approach, given the need of a soil with a strongly different isotopic signature. We succeeded in mimicking the texture and bulk density of the ambient soil, but not the soil fertility (the C4 soil was nutrient-poorer than the surrounding C3 soil). It was, therefore, necessary to measure root biomass both inside and outside the in-growth bags, and subsequently correct the root C input estimates (Fig. 3).

Treatment C accumulation rates

The plant-derived soil C accumulation (around 50 g C m−2 y−1 in T-1, including all inputs) was lower than that reported in other studies. In a 30-year old silver fir forest in northern Italy accumulation rates of around 200 g C m−2 y−1 were observed from below-ground tree parts at the 0–15 cm soil depth, and 100 g C m−2 y−1 at the 15–30 cm depth, albeit with almost six times larger below-ground C inputs as compared to our site (Martinez et al. 2016). Carbon accumulation of new C3 derived C at our site occurred at the top soil layer mostly, with little accumulation in the deeper layers. This was coincident with the poplar fine roots profile, where most roots occurred in the upper 5 cm layer of the soil (Fig. 3) and with the occurrence of mycorrhizal C inputs. Moreover, no evidence was found for deep C inputs via leaching of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) originating from decomposing C3 litter, as we did not find any significant changes in δ13C in the deep soil layers of T-IV (only above-ground inputs). Probably the lack of soil C changes in the deep soil horizons were due to the short period considered. As the DOC represented a small flux, many more years are needed to detect any soil C change.

Genotype and former land use effects

Variations in the plant residues δ13C among genotypes and land uses were associated to differences in the water use efficiency of the trees at the site. Genotypes with a higher water use efficiency were more enriched with 13C (Verlinden et al. 2015b). Moreover, trees growing on former pasture (with higher soil nitrogen availability) displayed higher δ13C, as compared with trees growing on former cropland, likely driven by a nitrogen-related effect on photosynthetic capacities (Verlinden et al. 2015b). Differences in δ13C among different tree organs were already shown for leaves, wood and roots (Godbold et al. 2006), but the reasons for these isotopic patterns remain unclear (Cernusak et al. 2009). Although there were differences in δ13C (Table 3) and C inputs (Fig. 4) between genotypes and former land uses, no differences were detected in the new soil C formation.

Possible mechanisms for more root carbon than above-ground carbon accumulation

Despite the fact that the eutrophic conditions at the site probably favored high microbial C use efficiencies (Cotrufo et al. 2013), the high conversion of root C-inputs to SOM suggests that a large fraction of this SOC may still have been in undecomposed plant materials, likely forming light, coarse particulate organic matter pools. Conversely, above-ground plant inputs had a SOC formation efficiency of 9%, which is much lower than the estimated realizable 30% microbial carbon use efficiency in resource limited natural systems (Sinsabaugh et al. 2013). This suggests that a larger part of above-ground residues underwent a fast microbial decomposition during the three years of study, but the remaining 9% of C was presumably associated to minerals (Cotrufo et al. 2015). This proportion of above-ground derived C retention in soil C is in the range of the shoot-derived C retention of 1% and 12.2% reported for experiments with corn in Uruguay (Mazzilli et al. (2015) and in Canada (Bolinder et al. (1999). When the fate of 13C from pine needles and fine roots decomposing in situ was traced into SOC, more litter-derived SOC was found from roots than from needles (Bird and Torn 2006). However, on the longer-term the majority of the root derived C was found in undecomposed particulate organic matter, while needle-derived C contributed relatively more to the more stabilized SOM fraction with longer turnover time (Hatton et al. 2015). Consistently, in a controlled laboratory incubation, above-ground tissues were subject to faster microbial decomposition, resulting in more efficient formation of minerally associated organic matter (Lavallee et al. 2018). Decadal-scale studies are needed to determine which of these two pathways of SOC formation (sensu Cotrufo et al. 2015) leads to the highest persistent SOC storage.

The different decomposition rates of the above- and below-ground C sources might constitute another mechanism explaining the higher SOC formation efficiency of root litter versus aboveground litter. Root biomass is more suberized than above-ground tissues. In a number of ecosystems suberins were found to significantly contribute to new soil C formation with a longer turn-over rate than above-ground lipids (Hamer et al. 2012; Ji et al. 2015; Mendez-Millan et al. 2010). However, root suberin and other exudates are released closed to the soil minerals that protect SOC from microbial decomposition. Instead, above-ground litter remain in the soil surface, at least in the short term, and the leaf lipids have lower probability for stabilization in the soil matrix.

Conclusions

Below-ground C inputs accumulated into the organic matter pool at efficiencies 7 to 10 fold higher than above-ground C inputs. Our findings have implications for soil C sequestration; if more plant C is allocated below-ground to fine roots instead of the above-ground parts, a higher soil C accrual is expected, at least in the short term. These results are particularly important in bioenergy plantations where the above-ground biomass is frequently removed for biomass and energy production.

References

Al Afas N, Marron N, Zavalloni C, Ceulemans R (2008) Growth and production of a short-rotation coppice culture of poplar—IV: fine root characteristics of five poplar clones. Biomass Bioenergy 32:494–502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2007.11.007

Alberti G, Vicca S, Inglima I, Belelli-Marchesini L, Genesio L, Miglietta F, Marjanovic H, Martinez C, Matteucci G, D’Andrea E (2015) Soil C: N stoichiometry controls carbon sink partitioning between above-ground tree biomass and soil organic matter in high fertility forests. iForest 8:195–206

Andrés P, Moore JC, Cotrufo F, Denef K, Haddix ML, Molowny-Horas R, Riba M, Wall DH (2017) Grazing and edaphic properties mediate soil biotic response to altered precipitation patterns in a semiarid prairie. Soil Biol Biochem 113:263–274

Andriulo A, Mary B, Guerif J (1999) Modelling soil carbon dynamics with various cropping sequences on the rolling pampas. Agronomie 19:365–377

Balesdent J, Wagner GH, Mariotti A (1988) Soil organic matter turnover in long-term field experiments as revealed by carbon-13 natural abundance. Soil Sci Soc Am J 52:118–124. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1988.03615995005200010021x

Batjes NH (1996) Total carbon and nitrogen in the soils of the world. Eur J Soil Sci 47:151–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2389.1996.tb01386.x

Berhongaray G, El Kasmioui O, Ceulemans R (2013a) Comparative analysis of harvesting machines on an operational high-density short rotation woody crop (SRWC) culture: one-process versus two-process harvest operation. Biomass Bioenergy 58:333–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2013.07.003

Berhongaray G, Janssens IA, King JS, Ceulemans R (2013b) Fine root biomass and turnover of two fast-growing poplar genotypes in a short-rotation coppice culture. Plant Soil 373:269–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-013-1778-x

Berhongaray G, King JS, Janssens IA, Ceulemans R (2013c) An optimized fine root sampling methodology balancing accuracy and time investment. Plant Soil 366:351–361. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-012-1438-6

Berhongaray G, Verlinden MS, Broeckx LS, Ceulemans R (2015) Changes in belowground biomass after coppice in two Populus genotypes. For Ecol Manag 337:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2014.10.035

Berhongaray G, Verlinden MS, Broeckx LS, Janssens IA, Ceulemans R (2017) Soil carbon and belowground carbon balance of a short-rotation coppice: assessments from three different approaches. GCB Bioenergy 9:299–313

Bird JA, Torn MS (2006) Fine roots vs. needles: a comparison of 13 C and 15 N dynamics in a ponderosa pine forest soil. Biogeochemistry 79:361–382

Bolinder M, Angers D, Giroux M, Laverdiere M (1999) Estimating C inputs retained as soil organic matter from corn (Zea mays L.). Plant Soil 215:85–91

Bolinder M, Janzen H, Gregorich E, Angers D, VandenBygaart A (2007) An approach for estimating net primary productivity and annual carbon inputs to soil for common agricultural crops in Canada. Agric Ecosyst Environ 118:29–42

Broeckx LS, Verlinden MS, Ceulemans R (2012) Establishment and two-year growth of a bio-energy plantation with fast-growing Populus trees in Flanders (Belgium): effects of genotype and former land use. Biomass Bioenergy 42:151–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2012.03.005

Cernusak LA, Tcherkez G, Keitel C, Cornwell WK, Santiago LS, Knohl A, Barbour MM, Williams DG, Reich PB, Ellsworth DS (2009) Why are non-photosynthetic tissues generally 13C enriched compared with leaves in C3 plants? Review and synthesis of current hypotheses. Funct Plant Biol 36:199–213

Clemmensen K, Bahr A, Ovaskainen O, Dahlberg A, Ekblad A, Wallander H, Stenlid J, Finlay R, Wardle D, Lindahl B (2013) Roots and associated fungi drive long-term carbon sequestration in boreal forest. Science 339:1615–1618

Coleman K, Jenkinson D (1996) RothC-26.3-A model for the turnover of carbon in soil. In: Powlson D, Smith P, Smith J (eds) Evaluation of soil organic matter models. Springer, Berlin

Cotrufo M, Alberti G, Inglima I, Marjanović H, Lecain D, Zaldei A, Peressotti A, Miglietta F (2011) Decreased summer drought affects plant productivity and soil carbon dynamics in Mediterranean woodland. Biogeosciences 8:2729–2739

Cotrufo MF, Wallenstein MD, Boot CM, Denef K, Paul E (2013) The Microbial Efficiency-Matrix Stabilization (MEMS) framework integrates plant litter decomposition with soil organic matter stabilization: do labile plant inputs form stable soil organic matter? Glob Chang Biol 19:988–995. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12113

Cotrufo MF, Soong JL, Horton AJ, Campbell EE, Haddix M, Wall DH, Parton WJ (2015) Formation of soil organic matter via biochemical and physical pathways of litter mass loss. Nat Geosci 8:776–779

David H, Horwáth WR, Van Kessel C (2001) Acid fumigation of soils to remove carbonates prior to total organic carbon or carbon-13 isotopic analysis. Soil Sci Soc Am J 65:1853-1856

Del Galdo I, Six J, Peressotti A, Francesca Cotrufo M (2003) Assessing the impact of land use change on soil C sequestration in agricultural soils by means of organic matter fractionation and stable C isotopes. Glob Chang Biol 9:1204–1213

Di Rienzo JA, Casanoves F, Balzarini MG, Gonzalez L, Tablada M, Robledo CW (2011) InfoStat. versión 24-03-2011 edn. Universidad Nacional de Córdoba, Córdoba, Argentina

Dimitriou I, Mola-Yudego B, Aronsson P, Eriksson J (2012) Changes in organic carbon and trace elements in the soil of willow short-rotation coppice plantations. Bioenergy Res 5:563–572

Food and Agriculture Organization [FAO] (2014) World Reference Base for Soil Resources: International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps

Follett RF, Reed DA (2010) Soil carbon sequestration in grazing lands: societal benefits and policy implications. Rangel Ecol Manag 63:4–15

Godbold DL, Hoosbeek MR, Lukac M, Cotrufo MF, Janssens IA, Ceulemans R, Polle A, Velthorst EJ, Scarascia-Mugnozza G, De Angelis P, Miglietta F, Peressotti A (2006) Mycorrhizal hyphal turnover as a dominant process for carbon input into soil organic matter. Plant Soil 258:15–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-005-3701-6

Grace PR, Ladd JN, Robertson GP, Gage SH (2006) SOCRATES—a simple model for predicting long-term changes in soil organic carbon in terrestrial ecosystems. Soil Biol Biochem 38:1172–1176

Hamer U, Rumpel C, Dignac MF (2012) Cutin and suberin biomarkers as tracers for the turnover of shoot and root derived organic matter along a chronosequence of Ecuadorian pasture soils. Eur J Soil Sci 63:808–819

Hatton PJ, Castanha C, Torn MS, Bird JA (2015) Litter type control on soil C and N stabilization dynamics in a temperate forest. Glob Chang Biol 21:1358–1367

Jackson RB, Canadell J, Ehleringer JR, Mooney HA, Sala OE, Schulze ED (1996) A global analysis of root distributions for terrestrial biomes. Oecologia 108:389–411

Ji H, Ding Y, Liu X, Li L, Zhang D, Li Z, Sun J, Lashari MS, Joseph S, Meng Y (2015) Root-derived short-chain suberin diacids from rice and rape seed in a paddy soil under rice cultivar treatments. PLoS One 10:e0127474

Kätterer T, Bolinder MA, Andrén O, Kirchmann H, Menichetti L (2011) Roots contribute more to refractory soil organic matter than above-ground crop residues, as revealed by a long-term field experiment. Agric Ecosyst Environ 141:184–192

Kell DB (2012) Large-scale sequestration of atmospheric carbon via plant roots in natural and agricultural ecosystems: why and how. Phil Trans R Soc B 367:1589–1597

Kong AY, Six J (2010) Tracing root vs. residue carbon into soils from conventional and alternative cropping systems. Soil Sci Soc Am J 74:1201–1210

Kuzyakov Y, Domanski G (2000) Carbon input by plants into the soil. Review. J Plant Nutr Soil Sc 163:421–431. https://doi.org/10.1002/1522-2624(200008)163:4

Lavallee J, Conant R, Paul E, Cotrufo M (2018) Incorporation of shoot versus root-derived 13C and 15N into mineral-associated organic matter fractions: elucidating mechanisms using a litter-soil slurry incubation. Biogeochemistry 137:379–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10533-018-0428-z

Lehmann J, Kleber M (2015) The contentious nature of soil organic matter. Nature 528:60–68

Luo Z, Wang E, Sun OJ (2010) Can no-tillage stimulate carbon sequestration in agricultural soils? A meta-analysis of paired experiments. Agric Ecosyst Environ 139:224–231

Martinez C, Alberti G, Cotrufo MF, Magnani F, Zanotelli D, Camin F, Gianelle D, Cescatti A, Rodeghiero M (2016) Belowground carbon allocation patterns as determined by the in-growth soil core 13 C technique across different ecosystem types. Geoderma 263:140–150

Mazzilli SR, Kemanian AR, Ernst OR, Jackson RB, Piñeiro G (2015) Greater humification of belowground than aboveground biomass carbon into particulate soil organic matter in no-till corn and soybean crops. Soil Biol Biochem 85:22–30

McCormack ML, Dickie IA, Eissenstat DM, Fahey TJ, Fernandez CW, Guo D, Helmisaari HS, Hobbie EA, Iversen CM, Jackson RB (2015) Redefining fine roots improves understanding of below-ground contributions to terrestrial biosphere processes. New Phytol 207:505–518

Mendez-Millan M, Dignac MF, Rumpel C, Rasse DP, Derenne S (2010) Molecular dynamics of shoot vs. root biomarkers in an agricultural soil estimated by natural abundance 13C labelling. Soil Biol Biochem 42:169–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.10.010

Parton WJ, Ojima DS, Cole CV, Schimel DS (1994) A general model for soil organic matter dynamics: sensitivity to litter chemistry, texture and management. In: Bryant R, Arnold R (eds) Quantitative modeling of soil forming processes. ASA, CSSA, SSA, Madison

Pausch J, Kuzyakov Y (2018) Carbon input by roots into the soil: quantification of rhizodeposition from root to ecosystem scale. Glob Chang Biol 24:1–12

Powlson DS, Whitmore A, Goulding K (2011) Soil carbon sequestration to mitigate climate change: a critical re-examination to identify the true and the false. Eur J Soil Sci 62:42–55

Rasse DP, Rumpel C, Dignac M-F (2005) Is soil carbon mostly root carbon? Mechanisms for a specific stabilisation. Plant Soil 269:341–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-004-0907-y

Schmidt MW, Torn MS, Abiven S, Dittmar T, Guggenberger G, Janssens IA, Kleber M, Kögel-Knabner I, Lehmann J, Manning DA (2011) Persistence of soil organic matter as an ecosystem property. Nature 478:49–56

Shahbaz M, Kuzyakov Y, Heitkamp F (2017) Decrease of soil organic matter stabilization with increasing inputs: mechanisms and controls. Geoderma 304:76–82

Sinsabaugh RL, Manzoni S, Moorhead DL, Richter A (2013) Carbon use efficiency of microbial communities: stoichiometry, methodology and modelling. Ecol Lett 16:930–939

Smith P (2004) Soils as carbon sinks: the global context. Soil Use Manag 20:212–218. https://doi.org/10.1079/Sum2003233

Steingrobe B, Schmid H, Claassen N (2000) The use of the ingrowth core method for measuring root production of arable crops — influence of soil conditions inside the ingrowth core on root growth. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 163:617–622. https://doi.org/10.1002/1522-2624(200012)163:6

Treseder KK (2004) A meta-analysis of mycorrhizal responses to nitrogen, phosphorus, and atmospheric CO2 in field studies. New Phytol 164:347–355

Verlinden MS, Broeckx LS, Zona D, Berhongaray G, De Groote T, Camino Serrano M, Janssens IA, Ceulemans R (2013) Net ecosystem production and carbon balance of an SRC poplar plantation during the first rotation. Biomass Bioenergy 56:412–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biombioe.2013.05.033

Verlinden M, Broeckx L, Ceulemans R (2015a) First vs. second rotation of a poplar short rotation coppice: above-ground biomass productivity and shoot dynamics. Biomass Bioenergy 73:174–185

Verlinden M, Fichot R, Broeckx L, Vanholme B, Boerjan W, Ceulemans R (2015b) Carbon isotope compositions (δ13C) of leaf, wood and holocellulose differ among genotypes of poplar and between previous land uses in a short-rotation biomass plantation. Plant Cell Environ 38:144–156

Wardle DA, Bardgett RD, Klironomos JN, Setälä H, van der Putten WH, Wall DH (2004) Ecological linkages between aboveground and belowground biota. Science 304:1629–1633. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1094875.

Zona D, Janssens IA, Gioli B, Jungkunst HF, Camino-Serrano M, Ceulemans R (2013) N2O fluxes of a bio-energy poplar plantation during a two years rotation period. GCB Bioenergy 5:536–547

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the European Research Council under the European Commission’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) as ERC Advanced Grant agreement # 233366 (POPFULL), as well as by the Flemish Hercules Foundation as Infrastructure contract # ZW09-06. Further funding was provided by the Flemish Methusalem Programme and by the Research Council of the University of Antwerp. GB was supported by the Erasmus-Mundus External Cooperation, Consortium EADIC – Window Lot 16 financed by the European Union Mobility Programme # 2009-1655/001-001. We gratefully acknowledge the excellent technical, logistic and field support of the entire POPFULL team. We also thank Drs. Eugene Kelly, Keith Paustian, Catherine Stewart and Bas van Wesemael for helping with the C4 soil collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Ingrid Koegel-Knabner.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 1178 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Berhongaray, G., Cotrufo, F.M., Janssens, I.A. et al. Below-ground carbon inputs contribute more than above-ground inputs to soil carbon accrual in a bioenergy poplar plantation. Plant Soil 434, 363–378 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-018-3850-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-018-3850-z