Abstract

Background

Pharmacists contribute to medication safety by providing their services in various settings. However, standardized definitions of the role of pharmacists in hospice and palliative care (HPC) are lacking.

Aim

The purpose of this scoping review was to provide an overview of the evidence on the role of pharmacists and to map clinical activities in inpatient HPC.

Method

We performed a scoping review according to the PRISMA-ScR extension in CINAHL, Embase, and PubMed. We used the American Society of Hospital Pharmacists (ASHP) Guidelines on the Pharmacist’s Role in Palliative and Hospice Care as a framework for standardized categorization of the identified roles and clinical activities.

Results

After screening 635 records (published after January 1st, 2000), the scoping review yielded 23 publications reporting various pharmacy services in HPC. The articles addressed the five main categories in the following descending order: ‘Medication order review and reconciliation’, ‘Medication counseling, education and training’, ‘Administrative Roles’, ‘Direct patient care’, and ‘Education and scholarship’. A total of 172 entries were mapped to the subcategories that were added to the main categories.

Conclusion

This scoping review identified a variety of pharmacists’ roles and clinical activities. The gathered evidence will help to establish and define the role of pharmacists in inpatient hospice and palliative care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impact statements

-

A variety of clinical pharmacy activities were identified to help establish a standardized definition of pharmacists’ roles in inpatient HPC.

-

Among the identified clinical activities, pharmacist-led systematic medication reviews and drug therapy adjustments to optimize medication regimens were the most commonly reported.

Introduction

In hospice and palliative care (HPC), drug therapy is focused on decreasing patients’ symptom burden and improving their quality of life [1]. However, end-of-life medication has to balance complex factors [2]. On average, palliative care patients receive 7.0–7.8 drugs daily [2,3,4]. Drug-related problems (DRPs), encompassing mainly inadequate drug treatment, inappropriate dosages, drug–drug interactions, adverse drug events, medication errors, and poor adherence [5, 6], may arise from the patients’ general vulnerability, their comorbidities, and the high prevalence of polypharmacy [7, 8]. To prevent potential harm from DRPs, it is necessary to enable rational and appropriate prescribing, to decrease prescribing errors, and to identify potential DRPs [9, 10].

A 2021 German study in patients of a hospital-based palliative care (PC) unit demonstrated DRPs’ impact on symptom progression. As symptom control requirements and medication regimens became more complex, DRPs arose more frequently. Pharmacists’ medication reviews and subsequent recommendations for action led to successful detection and interventions to resolve the identified DRPs, while maintaining adequate symptom control [11].

The body of evidence demonstrating clinical and economic benefits of pharmacy services, encompassing pharmaceutical care [12] to increase medication safety in various settings is growing [13,14,15]. Defined as a subset of clinical pharmacy practice, pharmaceutical care contributes to the care of individuals [12]. According to the American Society of Hospital Pharmacists, pharmaceutical care is the “responsible provision of medication-related care for the purpose of achieving definite outcomes that improve a patient’s quality of life” [16] which is in accordance with the main principle of HPC to maximize quality of life wherever possible [17, 18]. Although there have been major advances in defining the role of pharmacists in HPC [19, 20], standardization is lacking. This was revealed in a 2021 qualitative study on the role of hospice pharmacists in the UK, a country with advanced pharmacy services in various settings [21]. There is a lack of a standardized definition not only in Europe but also on a national level. In Switzerland, the role of pharmacists has not yet been defined and a recent nationwide study on PC networks failed to include pharmacists [22]. Occasionally, clinical pharmacists perform medication reviews and join rounds in hospital-based PC units, as they do in other medical specialties [23]. To our knowledge, only one Swiss hospice or hospice-like institution (i.e., hospitals excluded) collaborates with a clinical pharmacist on a contractual basis (local survey performed in 2021) [24].

A European whitepaper on standards and norms for HPC lists pharmacists as members of the multiprofessional team in the provision of PC services, yet fails to define their roles [25]. The COVID-19 situation contributed efforts to further develop the role of pharmacists in HPC [26] and pharmacy services in patients with advanced cancer are increasingly implemented [27]. However, the scope of HPC is much broader. Implementation of pharmacy services and the impact on clinical outcomes need further investigation.

In order to establish a definition of the role of pharmacists in HPC and to implement pharmacy services, an overview of the current evidence on the role of pharmacists and clinical activities in HPC is essential.

Aim

The purpose of this scoping review was to provide an overview of the evidence of the role of pharmacists and to map clinical activities in inpatient HPC.

Method

We performed and reported this scoping review according to the recommendation of the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews [28]. A protocol, that was not previously published, was used to outline the search strategy and to document the process.

Search and information sources

We used the aspects location (‘L’), professionals (‘P’), and services (‘SE’) from the mnemonic ECLIPSE [29] to develop the search string, define the eligibility criteria, and structure the data charting process. The search string was designed combining the three building blocks ‘Hospice-like settings’, ‘Pharmacist’, ‘Pharmacy Services’, and ‘using MeSH terms and keywords. It was initially developed in PubMed and translated for use in Embase (using Emtree terms) and CINAHL (using Subject Headings) facilitated through the polyglot website [30]. The full electronic search strategy is available as a Supplementary file S1). Because provision of clinical pharmacy services is rapidly changing and adapting to the current needs [14], the search was limited to articles published after turn of the millennium (January 1st, 2000). The final search was performed on February 10th, 2021. No filters were applied. Employees of the university’s library were contacted for procurement of articles where full text versions were not available online. A weekly literature alert was set to identify relevant newly published articles. The latest alert check and hand-search to identify eligible articles that were published since February 2021 took place on October 10, 2022.

Although modern definitions stress that PC is a “component of comprehensive care throughout the life course” [31], this scoping review focuses on inpatient HPC settings as the ASHP guidelines used for mapping of the identified clinical pharmacy activities were developed from a hospital perspective (see “Synthesis of results” section).

Eligibility criteria and selection of sources of evidence

After removing all duplicates, title-abstract screening was performed in Mendeley® by two independent reviewers (DH, UW) based on predefined eligibility criteria (see Table 1). Discrepancies were resolved through consensus. Full text screening was performed by one reviewer (DH) and discussed with two additional reviewers (UW, CMM).

Data charting process and data items

A table to collect charted data (author, country, year of publication, type of publication, study design, methods, setting, role of pharmacist, and clinical pharmacy activities) was created in Excel® with one row for each included article. Frequency of the mapped clinical activities, and, where applicable, their impact on clinical outcomes and findings from cost analyses were assessed. The data charting process of the included articles was discussed among the authors. The detailed table is provided by the authors upon request.

To standardize the heterogeneous definitions of the publication types included, the terms practice research report and practice report were applied to articles that deviated from the classical structure of an original article. Those reporting research performed in practice (e.g., qualitative research for implementation projects), but with no clear publication structure, were classed as practice research reports; narrative reports from practice sites were classified as practice reports (e.g., project progress reports, case studies).

Synthesis of results

We created a table (see “Summary of identified pharmacy services provided to inpatient hospice and palliative care”, Supplementary file 2) to summarize the charted data. We categorized the identified clinical activities and mapped them to the following five main categories of the American Society of Hospital Pharmacists (ASHP) Guidelines on the Pharmacist’s Role in Palliative and Hospice Care [19]:

-

‘Direct patient care’: to serve as a resource on the optimal use of medication in symptom management (optimized outcomes), to optimize a medication regimen, and to improve adherence to a medication regimen.

-

‘Medication order review and reconciliation’: to manage and improve the medication-use process in patient care settings, to optimize a medication regimen and to increase patient safety as well as pharmacoeconomy.

-

‘Medication counseling, education and training’: to provide medication counseling, to train and to educate staff, patients, caregivers, and families.

-

‘Administrative roles’: to develop procedures that ensure safe use of medications, to optimize patient care services, to support medication supply chain management.

-

‘Education and scholarship’: to contribute to the body of knowledge of pharmacists in PC and further develop the role of pharmacists.

With these guidelines, the ASHP established a definition of the pharmacist’s role in HPC and provided a summary of general best practice principles. Further, the article was used to determine subcategories for each of the five main categories.

Findings of articles that investigated impact on clinical outcomes and/or performed a cost analysis of the pharmacy services (see “Summary of identified pharmacy services provided to inpatient hospice and palliative care”, Supplementary file 2) were separately mapped (see “Impact on clinical outcomes and findings from cost analyses”, Table 2).

Results

Selection of sources of evidence

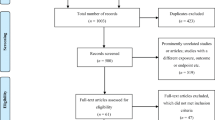

A total of 742 publications were identified in the three databases. After removal of duplicates, 635 articles were screened for eligibility based on title and abstract. We assessed 129 articles for eligibility based on full text. The scoping review yielded a total of 23 publications, of which 22 were further used for data charting (see Fig. 1). Although identified in the literature search, the clinical roles and activities listed in the ASHP guidelines were not included in the data charting process. However, the article served as an indicator article to confirm that the search strategy had included the most relevant publications on the topic.

Flowchart of the scoping review [28]

Characteristics of sources of evidence

Of the included sources, 77.3% (n = 17/22) originated from the United States of America (USA). The others sources originated from the United Kingdom (n = 3/22, 13.6%), Poland (n = 1/22, 4.5%), and Qatar/Canada (n = 1/23, 4.5%). The majority of the included articles (n = 12/22, 54.5%) were original articles [21, 32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42], followed by articles classified as practice reports (n = 6/22, 27.3%) [43,44,45,46,47,48] and practice research reports (n = 4/22, 18.2%) [26, 49,50,51].

Synthesis of results

Table 2 in Supplementary material shows a summary of all pharmacists’ roles and clinical activities. Overall, the articles revealed a wide range of pharmacists’ clinical roles and activities as well as pharmacy services provided to inpatient HPC settings (see “Summary of identified pharmacy services provided to inpatient hospice and palliative care”, Supplementary file 2).

The frequency of the five main categories mentioned among the 22 articles was assessed with the following descending order observed: ‘Medication order review and reconciliation’ (n = 20/22, 90.9%), ‘Medication counseling, education and training’ (n = 19/22, 86.4%), ‘Administrative Roles’ and ‘Direct Patient Care’, both (n = 16/22, 72.7%), and ‘Education and Scholarship’ (n = 10/22, 45.5%).

A total number of 172 entries (N = 100%) was mapped to the five main categories in descending order of frequency: ‘Medication Counseling, Education and Training’ (n = 46/172, 26.7%), ‘Administrative Roles’ (n = 44/172, 25.6%), ‘Direct Patient Care’ (n = 39/172, 22.7%), ‘Medication Order Review and Reconciliation’ (n = 26/172, 15.1%), and ‘Education and Scholarship’ (n = 17/172, 9.9%).

Subcategories were added to each main category to summarize and assess the identified clinical activities more accurately. Most of the articles addressed the subcategory ‘Medication review (optimizing medication regimens and drug therapy adjustments)’ (n = 20/22, 90.9%), followed by ‘Medication counseling, training, and education to health care providers’ (n = 17/22, 77.3%) and ‘Medication counseling, training, and education to patients, caregivers, and families’ (n = 15/22, 68.2%).

The same three subcategories represented the most entries of clinical activities.

Results of individual sources of evidence

As both, the subcategory ‘medication review (optimizing medication regimens and drug therapy adjustments)’ and the corresponding main category ‘Medication Order Review and Reconciliation’ were addressed most frequently by the articles, with the following details provided for this clinical pharmacists’ role: A 2021 US study analyzed the results of a pharmacist-led deprescribing pilot program [36]. The number of patient encounters with the hospice pharmacist was associated with 3.2-fold higher odds of achieving more than 50% reduction in medications that were recommended for deprescribing. Another article introduced the DE-PHARM initiative, which was aimed at ensuring patient-centered, health-focused, prognosis-appropriate, and rational medication regimens [50]. DE-PHARM was a pharmacist-driven program for deprescribing, focusing on patients with limited life expectancy in long-term care. Other articles also highlighted the importance of deprescribing and discontinuing medications as pharmacy services in hospice care [33, 34, 41, 43, 47, 49].

Fourteen articles reported impact on clinical outcomes of the clinical activities (n = 14/22, 63.6%). However, only five reported measurable impacts on clinical outcomes. Five articles reported findings from cost analyses (see Table 2) with all demonstrating an association between the provision of pharmacy services and potential cost savings [26, 33, 35, 37, 51]. One of these articles showed that there was no significant association between the time spent by the pharmacist performing services and the number of medication requirements and per diem medication costs, regardless of the pharmacist chosen by the hospices (prescription benefits manager, pharmacist on staff or both) [35]. Another article demonstrated not only a favorable return on investment (based on cost avoidance due to preventable adverse drug events identified by pharmacist) that exceeds a pharmacist’s annual salary but also stated that pharmacy services ‘contribute to the quality and value of care provided to a PC patient and their family, in a way that is left unsatisfied if this discipline’s perspective is not included in the care equation’ [37].

Discussion

Summary of evidence

Based on our scoping review, we identified various clinical pharmacy activities and their impact on clinical outcomes that helped to gauge the scope of pharmacists’ roles in inpatient HPC. Interestingly, most publications on the topic originated from the USA. Although the modern hospice care movement was initiated in England in the nineteen-sixties [52], our search yielded only three articles from European countries. One possible explanation is that clinical pharmacy is well established in the USA, with high levels of specialized education available for pharmacists [53]. For example, US pharmacists can be trained specifically in HPC [19, 32].

The identified pharmacists’ activities and clinical roles are mainly associated with intentions to increase medication safety, and thus, patient safety. The activities involve medication counselling and education of health care providers, patients, and their families, optimization of medication regimens and therapy adaptions, as well as medication and symptom management provided in the context of direct patient care.

Due to the inherent complexity of the drug therapy regimen, at every stage of palliative care, therapy decisions and changes to the drug regimen are prone to DRPs. To avoid occurrence of DRPs, to early identify and resolve occurring DRPs, HPC settings could potentially benefit from medication reconciliation, medication review, and pharmacist-led deprescribing [33, 34, 54]. Early identification of DRPs [9, 54] paired with interprofessional communication are effective pharmacists’ activities that have been demonstrated to increase medication safety in various settings [9]. To help prevent future DRPs, alongside pharmacist-led optimization of medication regimens, drug consultations are valuable in HPC settings both to prevent, to identify, and resolve DRPs [36, 50].

Complex, frequently changing drug therapy regimens in HPC patients require thorough assessment and interprofessional exchange. A reflective approach with medications is central to a safe and rational drug regimen and particularly relevant in HPC, where patients are highly vulnerable to issues that could reduce their quality of life even for a short time [8]. Therapeutic goals change drastically with the decision to pursue non-curative treatment in favor of symptom management and quality of life. Goals must constantly be assessed and adapted, including patients’ and their families’ individual goals and needs. Thus, the adaption of medication can vary greatly over time [55]. Deprescribing is an important step to reduce polypharmacy and outweigh the benefit of each drug against its possible harm [56]. The beneficial effects of pharmacist-led deprescribing and interventions to discontinue medications were discussed in several publications [33, 36, 50]. The importance of drug therapy adaptions was reflected in the numerous articles addressing the main category ‘Medication Order Review and Reconciliation’.

The variety of pharmacists roles and clinical activities were not only shown to have a positive impact on clinical outcomes but also to be associated with lower per patient-day drug costs and cost avoidance associated with adverse drug events that were identified and resolved by pharmacists. Similar findings emerged from a 2004 survey study, where respondents reported lower overall pharmaceutical costs attributed to hiring a clinical pharmacist [57].

Strengths and weaknesses

The MeSH term ‘Palliative Care’ is rather broad and may include publications that address earlier stages of PC (e.g., at diagnosis) rather than the last 6 months of life as defined in this scoping review. Therefore, it was not included in the search strategy. By restricting our search, we risked missing relevant publications. Definitions and concepts of HPC settings differ internationally [25], nevertheless, we expect only slight differences in the scope of pharmacists’ roles and clinical activities as complexity of drug regimens is associated with HPC in general, irrespective of the setting. The descriptive design of the scoping review has served the purpose to provide an overview of the evidence of the role of pharmacists in inpatient HPC well.

The study types revealed a high level of heterogeneity. However, this was addressed by introducing the two article categories practice research report and practice report. Further, there was a deviation in the denotation of the described clinical activities bearing a risk of mapping them to the wrong category. Standardized categorization was achieved by discussing data charting among the authors. Using the ASHP guidelines [19] as a framework was helpful to structure the findings from the literature. The structured process helped to assess the scope of pharmacists’ clinical activities and services provided to inpatient HPC. Pharmacy services are highly advanced in the US with different fields of specialization available for clinical pharmacists. Therefore, the ASHP guidelines could serve as framework to define the role of pharmacists in HPC in other countries.

Gaps in the availability of definitions of the pharmacist’s role in inpatient HPC can be used as food for thought for further research.

Further research

Even in countries where ΗPC settings are small and the variety of prescribed medications is limited, pharmacists’ skills and knowledge can support health care providers in the medication management, especially in HPC patients with complex drug therapy regimens that are prone to DRPs. In order to develop a structured definition of the role of pharmacists in HPC, more research on clinical pharmacy activities assessing their impact on clinical outcomes and overall costs of care is needed.

Conclusion

This scoping review identified a variety of pharmacists’ clinical roles and activities in inpatient hospice and palliative care. The most notable of the identified clinical activities were optimizing medication regimens to reduce inappropriate medication and associated risks for drug-related problems as well as the provision of medication counseling to health care providers, patients, families, and caregivers. The findings helped to highlight pharmacist contributions to inpatient hospice and palliative care. The gathered evidence will help to establish and define the role of pharmacists in inpatient hospice and palliative care settings.

References

Watson M, Campbell R, Vallath N, et al. Principles of drug use in palliative care (chapter 5). In: Watson M, Campbell R, Vallath N, et al., editors. Oxford handbook of palliative care. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2019. ISBN 978-0-19-87465-5.

Wernli U, Hischier D, Meier CR, et al. Prescription trends in hospice care: a longitudinal retrospective and descriptive medication analysis. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/10499091221130758.

Kadoyama KL, Noble BN, Izumi S, et al. Frequency and documentation of medication decisions on discharge from the hospital to hospice care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:1258–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15860.

Kotlinska-Lemieszek A, Paulsen O, Kaasa S, et al. Polypharmacy in patients with advanced cancer and pain: a European cross-sectional study of 2282 patients. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2014;48:1145–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.03.008.

Krishnaswami A, Steinman MA, Goyal P, et al. Deprescribing in older adults with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:2584–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.467.

Strand LM, Morley PC, Cipolle RJ, et al. Drug-related problems: their structure and function. DICP. 1990;24:1093–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/106002809002401114.

O’Mahony D, O’Connor MN. Pharmacotherapy at the end-of-life. Age Ageing. 2011;40:419–22. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afr059.

Rémi C, Bausewein C, Twycross R, et al. Arzneimitteltherapie in der Palliativmedizin [Drug therapy in palliative care]. 2nd ed. Munich: Urban & Fischer; 2015. ISBN 978-3-437-23672-3.

Mekonnen AB, McLachlan AJ, Brien JA. Effectiveness of pharmacist-led medication reconciliation programmes on clinical outcomes at hospital transitions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010003. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010003.

Maxwell SR. Rational prescribing: the principles of drug selection. Clin Med (Lond). 2016;16:459–64. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.16-5-459.

Bauer D. Auswirkungen einer intersektoralen pharmakotherapeutischen Betreuung durch Apotheker auf die Symptomlast von Palliativpatienten [Effects of intersectoral pharmacotherapeutic care by pharmacists on symptom burden in palliative care patients]. Dissertation. Faculty of Medicine Ludwig-Maximilian University (LMU) Munich. 2018.

Dreischulte T, van den Bemt B, Steurbaut S, et al. European Society of Clinical Pharmacy definition of the term clinical pharmacy and its relationship to pharmaceutical care: a position paper. Int J Clin Pharm. 2022;44:837–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-022-01422-7.

Al-Quteimat OMA, Amer M. Evidence-based pharmaceutical care: the next chapter in pharmacy practice. Saudi Pharm J. 2016;24:447–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2014.07.010.

Parrish R, Chew L. Lecture 1-justification of the value of clinical pharmacy services and clinical indicators measurements-introductory remarks from a traveler on a 40-year wayfaring journey with clinical pharmacy and pharmaceutical care. Pharmacy (Basel, Switzerland). 2018;6:56. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy6030056.

Touchette DR, Doloresco F, Suda KJ, et al. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacy services: 2006–2010. Pharmacotherapy. 2014;34:771–93. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.1414.

American Society of Hospital Pharmacists. ASHP statement on pharmaceutical care. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1993;50:1720–3.

Kaboli PJ, Hoth AB, McClimon BJ, et al. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:955–64. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.9.955.

Lee SWH, Mak VSL, Tang YW. Pharmacist services in nursing homes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85:2668–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.14101.

Herndon CM, Nee D, Atayee RS, et al. ASHP guidelines on the pharmacist’s role in palliative and hospice care. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2016;73:1351–67. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp160244.

Krzyżaniak N, Pawłowska I, Bajorek B. An overview of pharmacist roles in palliative care: a worldwide comparison. An overview of pharmacist roles in palliative care: a worldwide comparison. Palliat Med Pract. 2016;10:160–73.

Edwards Z, Chapman E, Pini S, et al. Understanding the role of hospice pharmacists: a qualitative study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2021;43:1546–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-021-01281-8.

Reeves E, Schweighoffer R, Liebig B. An investigation of the challenges to coordination at the interface of primary and specialized palliative care services in Switzerland: a qualitative interview study. J Interprof Care. 2021;35:21–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1724085.

Strasser F, Sweeney C, Willey J, et al. Impact of a half-day multidisciplinary symptom control and palliative care outpatient clinic in a comprehensive cancer center on recommendations, symptom intensity, and patient satisfaction: a retrospective descriptive study. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2004;27:481–91.

Wernli U, Duerr F, Kobleder A, et al. Sichere und rationale Medikation im Hospiz-Setting—eine neue Rolle für Apotheker:innen? [Safe and rational medication in hospice care—a new role for pharmacists?]. Palliative. 2021;04:48–52.

Radbruch L, Payne S. White paper on standards and norms for hospice and palliative care in Europe: part 2. Eur J Palliat Care. 2010;17:22–33.

Hanley J, Spargo M, Brown J, et al. The development of an enhanced palliative care pharmacy service during the initial COVID-19 surge. Pharmacy (Basel). 2021;9:196. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy9040196.

Franco J, de Souza RN, Lima TDM, et al. Role of clinical pharmacist in the palliative care of adults and elderly patients with cancer: a scoping review. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2022;28:664–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/10781552211073470.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

Wildridge V, Bell L. How CLIP became ECLIPSE: a mnemonic to assist in searching for health policy/management information. Health Info Libr J. 2002;19:113–5. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-1842.2002.00378.x.

Clark JM, Sanders S, Carter M, et al. Improving the translation of search strategies using the Polyglot Search Translator: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Libr Assoc. 2020;108:195–207. https://doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2020.834.

67th World Health Assembly. Resolution WHA67.19 (item 15.5). Strengthening of palliative care as a component of comprehensive care throughout the life course. 2014. http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA67/A67_R19-en.pdf. Accessed 1 Feb 2023.

Atayee RS, Sam AM, Edmonds KP. Patterns of palliative care pharmacist interventions and outcomes as part of inpatient palliative care consult service. J Palliat Med. 2018;21:1761–7.

Basri DS, DiScala SL, Brooks AT, et al. Analysis of inpatient hospice pharmacist interventions within a veterans affairs medical center. J Pain Pall Care Pharmacother. 2018;32:240–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/15360288.2019.1615025.

Kemp LO, Narula P, McPherson ML, et al. Medication reconciliation in hospice: a pilot study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2009;26:193–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909108328698.

Latuga NM, Wahler RG, Monte SV. A national survey of hospice administrator and pharmacist perspectives on pharmacist services and the impact on medication requirements and cost. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2012;29:546–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909111432291.

Le V, Patel N, Nguyen Q, et al. Retrospective analysis of a pilot pharmacist-led hospice deprescribing program initiative. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:1370–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17122.

Lehn JM, Gerkin RD, Kisiel SC, et al. Pharmacists providing palliative care services: demonstrating a positive return on investment. J Palliat Med. 2019;22:644–8. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2018.0082.

Malotte K, Naidu DR, Herndon CM, et al. Multicentered evaluation of palliative care pharmacists’ interventions and outcomes in California. J Palliat Med. 2021;24:1358–63. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2020.0566.

Pawłowska I, Pawłowski L, Lichodziejewska-Niemierko M. The role of a pharmacist in a hospice: a nationwide survey among hospice directors, pharmacists and physicians. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2016;23:106–12.

Romero NM, DiScala S, Quellhorst J, et al. Pharmacy-led quality improvement project on pain control using continuous subcutaneous infusion of opioids in an inpatient hospice unit. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2020;37:885–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909120912954.

Wilby KJ, Mohamad AA, AlYafei SA. Evaluation of clinical pharmacy services offered for palliative care patients in Qatar. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2014;28:212–5. https://doi.org/10.3109/15360288.2014.938884.

Wilson S, Wahler R, Brown J, et al. Impact of pharmacist intervention on clinical outcomes in the palliative care setting. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2011;28:316–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909110391080.

Demler TL. Pharmacist involvement in hospice and palliative care, in U.S. Pharmacist. Buffalo: T.L. Demler, State University of New York, Buffalo School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences; 2016, pp. HS2–HS5.

Dickman A. The place of the pharmacist in the palliative care team. Eur J Palliat Care. 2010;17:133–5.

Kaldy J. Niche markets: filling gaps with expertise, ingenuity. Consult Pharm J Am Soc Consult Pharm. 2015;30:434–42.

Meade V. Senior care pharmacy profile: Grace Lawrence. Innovative services for assisted living, hospice, and the community. Consult Pharm. 2006;21:38–44. https://doi.org/10.4140/tcp.n.2006.38.

Protus BM, Kimbrel JM, Gonzalez J. Clinical pharmacists’ partnership with hospices drives an evolution of PBM services. In: Protus BM, editor. Formulary. Dublin: HospiScript, Catamaran Company; 2012. p. 428–32.

Quinn MJ. Cytochrome P450 in palliative care and hospice kits. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2019;21:280–5.

Knowlton CH. Collaborative pharmacy practice enters hospice care. Caring. 2004;23:26–9.

Pruskowski J, Arnold R, Skledar SJ. Development of a health-system palliative care clinical pharmacist. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74:e6–8.

Richter C. Implementation of a clinical pharmacist service in the hospice setting: financial and clinical impacts. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2018;32:256–9.

Stolberg M. Die Geschichte der Palliativmedizin: Medizinische Sterbebegleitung von 1500 bis heute [The history of palliative medicine: end-of-life care from 1500 to the present day]. 2nd ed. Frankfurt am Main: Mabuse-Verlag; 2015. ISBN: 9783940529794.

Thompson J. Deprescribing in palliative care. Clin Med (Lond). 2019;19:311–4. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.19-4-311.

Hanlon JT, Weinberger M, Samsa GP, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a clinical pharmacist intervention to improve inappropriate prescribing in elderly outpatients with polypharmacy. Am J Med. 1996;100:428–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9343(97)89519-8.

O’Brien CP. Withdrawing medication: managing medical comorbidities near the end of life. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57:304–7.

Scott IA, Hilmer SN, Reeve E, et al. Reducing inappropriate polypharmacy: the process of deprescribing. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:827–34. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0324.

Nowels D, Kutner JS, Kassner C, et al. Hospice pharmaceutical cost trends. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2004;21:297–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/104990910402100414.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support received from Dr. Marc von Gernler (pharmacy information specialist at Medical Library, University of Bern) while we were planning and conducting the scoping review.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Bern. No specific funding was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wernli, U., Hischier, D., Meier, C.R. et al. Pharmacists’ clinical roles and activities in inpatient hospice and palliative care: a scoping review. Int J Clin Pharm 45, 577–586 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-023-01535-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-023-01535-7