Abstract

The exploitation of subsurface hydrocarbon reservoirs is achieved through the control of production and injection wells (i.e., by prescribing time-varying pressures and flow rates) to create conditions that make the hydrocarbons trapped in the pores of the rock formation flow to the surface. The design of production strategies to exploit these reservoirs in the most efficient way requires an optimization framework that reflects the nature of the operational decisions and geological uncertainties involved. This paper introduces a new approach for production optimization in the context of closed-loop reservoir management (CLRM) by considering the impact of future measurements within the optimization framework. CLRM enables instrumented oil fields to be operated more efficiently through the systematic use of life-cycle production optimization and computer-assisted history matching. Recently, we have proposed a methodology to assess the value of information (VOI) of measurements in such a CLRM approach a-priori, i.e. during the field development planning phase, to improve the planned history matching component of CLRM. The reasoning behind the a-priori VOI analysis unveils an opportunity to also improve our approach to the production optimization problem by anticipating the fact that additional information (e.g., production measurements) will become available in the future. Here, we show how the more conventional optimization approach can be combined with VOI considerations to come up with a novel workflow, which we refer to as informed production optimization. We illustrate the concept with a simple water flooding problem in a two-dimensional five-spot reservoir and the results obtained confirm that this new approach can lead to significantly better decisions in some cases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Hydrocarbons are found trapped in the pores of subsurface reservoir rock. To exploit oil and gas reservoirs, wells are drilled to connect the rock formation to the surface. Production wells deplete the reservoir by imposing bottom-hole pressures (BHPs) lower than the original reservoir pressure. Injection wells are used to inject fluids (e.g., water or gas) at higher BHPs than the original reservoir pressure to replace the produced volumes and maintain the pressure of the reservoir. Together, production and injection wells create a pressure gradient in the reservoir that forces the fluids originally in-place to flow through the rock formation towards the production wells. As in other processes, an improved performance (i.e., recovery of hydrocarbons) can be achieved by designing optimal control strategies (i.e., well settings) for the system. The flow of fluids through the reservoir involves complex (nonlinear) physical phenomena that depend on many characteristics of the reservoir system whose knowledge is usually very limited. Therefore, the search of production strategies for efficient recovery of hydrocarbons requires methods to handle the inherent uncertainties, in particular geological uncertainties. In our context, reservoir management is the set of practices used to mitigate the effect of these uncertainties and optimize the reservoir performance. To achieve that, reservoir engineers and geoscientists rely on models to characterize the reservoir, integrating all the knowledge available. These models are used to simulate the reservoir response to production strategies and provide elements to support the important decisions to be taken.

Recent tools developed to support decision making in reservoir operations rely on model-based optimization and uncertainty quantification to find the best production strategy. Closed-loop reservoir management (CLRM) goes a step further and takes advantage of the frequent measurements collected throughout the reservoir producing life-time to determine the optimal set of controls (see Jansen et al. 2005 and more references in the Sect. 2). This is achieved through the systematic use of life-cycle optimization in combination with computer-assisted history matching. This combination provides the ability to react to the observations from the true reservoir (i.e., measurements gathered through the designed surveillance plan), offering the opportunity to benefit from the remaining flexibility of the production strategy and compensate for possibly wrong previous decisions, which are doomed to be suboptimal due to the presence of uncertainty.

A major challenge in determining the optimal production strategy arises from the nature of the main uncertainties inherent to the reservoir management problem. The geological uncertainties are endogenous (Jonsbråten 1998): they only get revealed at the cost of decisions. In other words, the production measurements that can help reducing the uncertainty can only be gathered when the field is operated, which requires a decision to be made (i.e., an operational strategy to be defined). In practice this means that the future state of uncertainty depends on current and previous decisions. Therefore, a truly optimal production strategy can only be determined by considering its own impact in the future measurement outcomes and their consequences to the future decisions to be made under the future state of uncertainty.

Recently, we have proposed a methodology in which the CLRM framework is used to assess the value of future measurements (Barros et al. 2016a). Such a methodology allows one to quantify the expected value achievable with the improved decision making enabled by the selected surveillance plan. Thus, it can be used as a tool to assist operators in the design of the optimal surveillance plan (i.e., measurement type, location, frequency, precision,...).

In order to estimate the VOI for a given surveillance plan, we calculate the additional value of the future measurements in terms of the value enabled by the production strategies re-optimized in a closed-loop fashion with the new information. Because it considers the availability of future information, the VOI assessment framework can potentially also help eliminating the shortcoming of the traditional optimization approach related to the endogenous nature of the uncertainties. In this paper, we therefore propose to integrate VOI considerations into the production optimization framework to come up with a novel workflow, which we refer to as informed production optimization (IPO).

In Sect. 2 we recap the key concepts for the development of our new method and relate to previous work addressing problems of similar nature. Next, in Sect. 3, we introduce the proposed workflow for the simplest application of IPO, showing how it builds upon the VOI assessment framework we proposed in Barros et al. (2016a). Thereafter, we illustrate it with a small case study, describing details of our implementation and analyzing the improved VOI results obtained with IPO. After that, we discuss in Sect. 4 how the methodology can be extended to a more general case with multiple decision stages and observation times. Finally, in Sect. 5, we reflect on the advantages of this new concept to optimize production strategies, and we suggest directions for future work.

2 Background

2.1 Closed-loop reservoir management (CLRM)

Closed-loop reservoir management (CLRM) is a combination of frequent life-cycle production optimization and data assimilation (also known as computer-assisted history matching); see Fig. 1. Life-cycle optimization aims at maximizing a financial measure, typically net present value (NPV), over the producing life of the reservoir by optimizing the production strategy. This may involve well location optimization, or, in a more restricted setting, optimization of well rates and pressures for a given configuration of wells, on the basis of one or more numerical reservoir models. Data assimilation involves modifying the parameters of one or more reservoir models, or the underlying geological models, with the aim to improve their predictive capacity, using measured data from a potentially wide variety of sources such as production data or time-lapse seismic. For further information on CLRM see, e.g., (Jansen et al. 2005, 2008, 2009; Naevdal et al. 2006; Sarma et al. 2008; Chen et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2009; Foss and Jensen 2011; Hou et al. 2015).

Closed-loop reservoir management as a combination of life-cycle optimization and data assimilation (Jansen et al. 2008)

2.2 Robust optimization

The conventional approach to optimization under geological uncertainties is the so-called robust optimization. Robust life-cycle optimization uses one or more ensembles of geological realizations (or reservoir models) to account for uncertainties and to determine the production strategy that maximizes a given objective function over the ensemble of N realizations: \({\mathbf {M}}=\{{\mathbf {m}}_1,{\mathbf {m}}_2,\dots ,{\mathbf {m}}_N\}\), where \({\mathbf {m}}_i\) is a vector of model parameters for realization i; see, e.g., Yeten et al. (2003) or Van Essen et al. (2009). Typically, the objective function to be optimized is the net present value (NPV):

where \(\mu _{{\text {NPV}}}\) is the ensemble mean of the objective function values \(J_i\) of the individual realizations. The objective function \(J_i\) for a single realization i is defined as usual:

where t is time, T is the producing life of the reservoir, \(q_{\text {o}}\) is the oil production rate, \(q_{\text {wp}}\) is the water production rate, \(q_{\text {wi}}\) is the water injection rate, \(r_{\text {o}}\) is the price of oil produced, \(r_{\text {wp}}\) is the cost of water produced, \(r_{\text {wi}}\) is the cost of water injected, b is the discount factor expressed as a fraction per year, and \(\tau\) is the reference time for discounting (typically one year). The outcome of the optimization procedure is a vector \({\mathbf {u}}\) containing the settings of the control variables over the producing life of the reservoir. More specifically, the vector \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior}} = [ \begin{matrix} {{\mathbf {u}}_1}^\top&{{\mathbf {u}}_2}^\top&\dots&{{\mathbf {u}}_M}^\top \end{matrix} ]^\top\) comprises the schedule of well controls for each of the M control time intervals (typically months or quarters) through the entire reservoir life-cycle T (typically tens of years). Note that, although the optimization is based on N models, only a single strategy \({\mathbf {u}}\) is obtained, under the rationale that only one strategy can be implemented in reality. Note also that, despite being popular among CLRM practitioners, the robust optimization approach presented by Van Essen et al. (2009) is only one way of dealing with uncertainty in production optimization. An alternative approach is to balance risk and return within the optimization by including well-defined risk measures or other utility functions in the objective function; see, e.g., Capolei et al. (2015) and Siraj et al. (2016).

2.3 VOI assessment in CLRM

Recently, we proposed a new methodology to assess the VOI of future measurements by making use of the CLRM framework (Barros et al. 2016a). Our approach presented there consists of closing the loop in the design phase to simulate how information obtained during the producing life-time of the reservoir comes into play in the context of optimal reservoir management. By considering both data assimilation and optimization in the procedure, we are able to not only quantify how information changes knowledge, but also how it influences the results of decision making (Barros et al. 2016a). This is possible because a new production strategy is obtained every time the models are updated with new information, and the strategies with and without additional information can be compared in terms of the value of the optimization objective function (typically NPV) obtained when applying these strategies to a virtual asset (a synthetic truth); see the flowchart in Fig. 2. We define the VOI of future measurements as the additional value realized by the asset when the future information is utilized for the optimization of the subsequent well controls. Since we do not have perfect knowledge of the true asset, we use an ensemble of plausible truths. For a problem with M control time intervals and considering the \(i^{\text {th}}\) plausible truth \({\mathbf {m}}^i_{\text {truth}}\), the baseline for VOI calculation is the value \(J^i_{\text {prior}}\) obtained without the future information. This involves optimization of all the well controls \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior}} = [ \begin{matrix} {{\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior},1}}^\top&{{\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior},2}}^\top&\dots&{{\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior},M}}^\top \end{matrix} ]^\top\) under the initial state of uncertainty (i.e., over the prior ensemble of model realizations). Note that here we consider the approximation presented (Barros et al. 2016a) to accelerate the procedure: although multiple prior ensembles are used to perform the history matching for the different plausible truths, a single ensemble is used to determine the strategy \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior}}\) optimal under initial uncertainty. Starting from this baseline, the additional value \(VOI^i_j\) of the \({\mathbf {d}}^i_j\) measurements gathered during the \(j^{\text {th}}\) control interval is the difference between the value \(J^i_{\text {post},j}\) obtained through the re-optimization of the well controls in the subsequent control time intervals \({\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post}}\left( t_{j+1}:T\right) =[{\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post},j+1}{}^\top {\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post},j+2}{}^\top \dots {\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post},M}{}^\top ]^\top\) compared to the baseline value \(J^i_{\text {prior}}\). Note that the values \(J^i_{\text {prior}}\) and \(J^i_{\text {post},j}\) are not statistics of the ensembles used in the analysis, but the value produced by implementing the strategies \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior}}\) and \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior}}^i\) to the plausible truth \({\mathbf {m}}_{\text {truth}}^i\). Note also that the well controls prior to the \({\mathbf {d}}_j^i\) measurements, i.e. \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior}}\left( 0:t_j\right) =[{{\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior},1}}^\top {{\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior},2}}^\top \dots {{\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior},j}}^\top ]^\top\), are the ones determined by optimization without future information (i.e., under initial uncertainty).

Accelerated procedure from Barros et al. (2016a)

Workflow for VOI assessment.

2.4 Future information and optimization

The concept of accounting for the availability of future information within the optimization is not new and has been investigated for several applications in different scientific communities. In operations research, such an optimization problem is addressed from a more mathematical perspective, being referred to as stochastic programming. Two-stage or multistage models are used to account for the sequential nature of the decisions, which allows the optimization to be expressed in a nested formulation. For more information, see Birge and Louveaux (1997), Ruszczyski and Shapiro (2003), Georghiou et al. (2011). In the formalism from decision and game theory, non-myopic decision rules are the ones where the decision makers look ahead and consider future information, opposed to the myopic approach in which the influence of current decisions on the future state of uncertainty (i.e., conditional posterior distributions) is ignored (Mirrokni et al. 2012). The artificial intelligence community refers to this class of problems as partially observable Markov decision processes (POMDPs), related to applications where direct observations of the state of the uncertain processes are not available (Smallwood and Sondik 1973; Hauskrecht 2000). In these cases, the decisions are optimized not only based on their direct contribution to produce value but also to maximize the expected pay-off (or reward) of subsequent decisions (Krause and Guestrin 2007, 2009). In systems and control theory, the dual control introduced by Feldbaum (1960, 1961) seeks to determine the optimal trade-off between excitation and control to promote a more active learning from the measurements while directing the system to its optimal state. This is only possible through the definition of control policies that anticipate the availability of future measurements and their learning effect. In this respect, Van Hessem (2004) discussed the steps to be taken to turn the traditional open-loop MPC (i.e., model predictive control) methods into feedback mechanisms that know how to respond to future measurements. More recently, Hanssen (2017) and Hanssen et al. (2017) proposed an implicit dual MPC controller that explicitly includes the feedback mechanism in the optimization problem. In system identification, Forgione et al. (2015) investigated the use of different model update strategies to enable batch-to-batch improvement in the control of industrial processes.

The main applications of these ideas are in: logistics and supply chain problems; network problems such as traffic control and power grids; medical decision making; planning and scheduling. In the oil and gas upstream sector, Jonsbråten (1998) applied stochastic programming to drilling sequence optimization in a simplified setting. Goel and Grossmann (2004) used stochastic models in the planning of offshore gas fields with uncertainties related to the reserves, but without considering reservoir simulation models. Foss and Jensen (2011) claimed that a conscious exploitation of the dual effect of controls can be significant in a reservoir system given the typical large uncertainties, but highlighted the fact that the dual-control problem is unsolvable in practice. Zenith et al. (2015) investigated the use of sinusoidal oscillations as a means of exciting the reservoir to obtain more informative data during well testing, but without analyzing the influence on the subsequent decisions. More recently, Abreu et al. (2015) have proposed a methodology to optimize under uncertainty the valve settings of smart wells considering the possibility of acquiring additional information in the future. Their approach uses the ideas of approximate dynamic programming to make the problem tractable. Hanssen (2017), Hanssen et al. (2017) proposed to tackle the reservoir management problem using closed-loop predictions to optimize control policies which account for the feedback mechanism instead of optimizing control sequences or set points.

3 Two-stage IPO

In the context of production optimization, the decision in question is the use of an optimized production strategy that maximizes the value of the asset. Despite the limited potential for learning due to the poor information content of typical production measurements, the knowledge about a reservoir changes along its producing life-time. Thus determining a single production strategy by performing robust optimization based on the initial state of uncertainty (Van Essen et al. 2009) is equivalent to ignoring the endogenous nature of the reservoir management problem. It is a myopic approach which will likely lead to suboptimal solutions. The stochastic programming ideas discussed in the previous section can be a solution to overcome this limitation.

In this paper we present a workflow for non-myopic production optimization within the CLRM framework. The proposed procedure is a combination of classical stochastic programming and our previously introduced workflow for VOI assessment in CLRM (Barros et al. 2016a). The idea is to model the decision process related to the reservoir management problem with the help of elements of the CLRM framework (i.e., ensemble-based uncertainty quantification, model-based optimization and computer-assisted history matching), which allows us to represent the sequential character of the decisions (corresponding to Markov decision process) while accounting for future measurement data with very limited information content. Because this approach considers future information when performing production optimization, we name it informed production optimization (IPO).

The ultimate goal of reservoir management is to maximize the value delivered by the asset with the implementation of production and surveillance strategies. Our methodology for VOI assessment (Barros et al. 2016a) provides a framework to quantify the value \(J^i_{\text {post},j}\) to be produced by the asset (here, the \(i^{\text {th}}\) plausible truth) with the incorporation of future information gathered through the designed surveillance strategy (here, measurements collected during the \(j^{\text {th}}\) control time interval). For simplicity, we initially address the case with only a single observation time. Later, we discuss how these ideas can be extended to cases with multiple observation times.

In the conventional approach for production optimization, we seek to maximize the predicted objective function for the ensemble of models anticipating that in a closed-loop setting, once more information becomes available, we will have the opportunity to improve our predictive models and adjust our strategies to achieve the best possible \(J^i_{\text {post},j}\). By following this reasoning, the optimization is making use of the flexibility of the remaining degrees of freedom \({\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post}}(t_{j+1}\!:\!T)=[{\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post},j+1}{}^\top {\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post},j+2}{}^\top \dots {\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post},M}{}^\top ]^\top\), while the part of the strategy prior to the future information \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior}}(0\!:\!t_j)=[{{\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior},1}}^\top {{\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior},2}}^\top \dots {{\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior},j}}^\top ]^\top\) is deemed to be suboptimal. We propose here to use \(J^i_{\text {post},j}\) as the cost function for our production optimization problem, as a way of reflecting the true goal of reservoir management when optimizing \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior}}(0\!:\!t_j)\). In fact, since we consider an ensemble of \(N_{\text {truth}}\) equiprobable plausible truths, we still perform robust optimization and our new objective function is defined as

where \(\mu _{\text {post},j}\) is the ensemble mean of the objective function values \(J^i_{\text {post},j}\) for the individual plausible truths. The objective function \(J^i_{\text {post},j}\) for a single realization i of the plausible truth is calculated according to the workflow in Fig. 2, and involves the solution of history matching with the future information gathered during control interval j and re-optimization of the production strategy for the subsequent control intervals \({\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post}}(t_{j+1}\!:\!T)\). We can also see the optimization of this new cost function as a two-stage stochastic model or a nested optimization problem where the outer optimization concerns the production strategy up to control interval j and the inner optimization determines the remaining part of the strategy, which will be different for each one of the \(N_{\text {truth}}\) plausible truths. Thus, the IPO problem can be formulated as

where the outcome of the optimization is a single optimal production strategy \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {IPO}}(0\!:\!t_j)\) until the observation time \(t_j\), and \(N_{\text {truth}}\) optimal strategies \({\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post}}(t_{j+1},2,\dots ,T)\), \(i=1,2,\dots ,N_{\text {truth}}\), for the remaining producing time. The proposed workflow to solve this optimization problem iteratively is displayed in Fig. 3. The procedure resembles the original VOI assessment workflow presented in Barros et al. (2016a) (Fig. 2), but contains an outer iterative loop (shown in blue) to keep updating the part of the production strategy prior to the observation time. The inner part of the workflow (indicated in yellow) remains the same as in Fig. 2; the only difference being that, for the optimization problem, we are only interested in evaluating the new cost function \(J^i_{\text {post},j}\) for each plausible truth and not in computing the associated VOI. Note that, for the case with a single observation time, the optimizations required in this (yellow) part of the workflow reduce to the conventional robust optimization problem, because there are no more future measurements to be considered after \(t_j\). Therefore, the optimal strategies \({\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post}}(t_{j+1}\!:\!T)\) can be determined by following the conventional robust optimization approach proposed by Van Essen et al. (2009). Note also that, just like the VOI workflow can be simplified to quantify the value of clairvoyance (VOC) (Barros et al. 2016a), the IPO procedure can be modified to perform optimization under the assumption that perfect revelation of the truth will be possible in the future.

By recommending a single \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {IPO}}(0\!:\!t_j)\) and multiple \({\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post}}(t_{j+1}\!:\!T)\) we design a flexible production strategy that accounts for the fact that we have the opportunity to update well controls after collecting the measurements at \(t_j\). Because we consider an ensemble of plausible truths, we recognize that the outcome of the future measurements (or future clairvoyance) is unknown, and that the ensemble of \({\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post}}(t_{j+1}\!:\!T)\) controls should reflect this uncertainty in the production strategy to be implemented after \(t_j\). Only when we proceed with the reservoir operations (i.e., by truly implementing \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {IPO}}(0\!:\!t_j)\)) and the actual measurements take place at \(t_j\), the uncertainty model can be updated and the optimal strategy to be implemented for the remaining time can be determined.

From the algorithmic point of view, this nested optimization can be solved just as any other optimization problem. The same methods used in the conventional robust approach apply but the cost function to be evaluated is more complex. Here, we use gradient-based methods for both the inner and the outer optimizations. In this setting, the main challenges concern the outer optimization, in particular for the definition of the starting point and the computation of the gradient for such a complex cost function. We explain the details of our implementation when we describe our case study in Sect. 3.1.

3.1 Example

To test our approach, we used a simple two-dimensional (2D) reservoir simulation model with an inverted five-spot well pattern (i.e., 4 production wells placed at the corners of the reservoir and 1 (water) injection well placed in the middle). This case study follows the exact same configuration with heterogeneous permeability and porosity fields as the example in one of our previous papers. See Barros et al. (2016a) for a more detailed description. We used \(N_\text {truth} = 50\) plausible truths and \(N_\text {truth} = 50\) ensembles of \(N = 49\) realizations of the porosity and permeability fields, conditioned to hard data in the wells, to model the geological uncertainties. The simulations were used to determine the set of well controls (bottom-hole pressures) that maximizes the NPV. The optimizations were run for a \(T = 1,500\)-day time horizon with well controls updated every 150 days, i.e. \(M = 10\), and, with five wells, u had 50 elements. We applied bound constraints to the optimization variables (200 bar \(\le p_\text {prod} \le\) 300 bar and 300 bar \(\le p_\text {inj} \le\) 500 bar). The whole exercise was performed in the open-source reservoir simulator MRST (Lie et al. 2012). For the inner part of the IPO workflow (shown in yellow in Fig. 3), we used the same setup as the one used in our previous work: a CLRM environment created by combining the adjoint-based optimization and EnKF modules available with MRST (see Barros et al. 2016a).

To perform the outer optimization (shown in blue in Fig. 3), we used an implementation of the StoSAG method (Fonseca et al. 2016). The ensemble-based gradient computation was very convenient for our IPO problem, allowing us to use a black-box approach to obtain the gradients for the complex and expensive cost function while benefiting from the computational advantages for cases with the presence of uncertainties. The main difference with the use of StoSAG in a conventional production optimization problem is that here the uncertainties are characterized by the ensemble of plausible truths. Thus we pair each of the \(N_\text {pert} = 50\) perturbations of the well controls to one of the \(N_\text {truth} = 50\) plausible truths and we estimate the search direction by an approximate linear regression of their \(J^i_{\text {post},j}\) values. We used a standard deviation of \(\sigma _\text {pert} = 0.01\) to generate the perturbations of the well controls. The starting point for the outer optimization is the solution obtained with the conventional robust optimization procedure.

For this case study, we considered the availability of oil flow rate measurements in the producers with absolute measurement errors (\(\epsilon _\text {oil} = 5 \text { m}^3/\text {day}\)). Just like in our previous paper (Barros et al. 2016a), the proposed workflow considers a single observation time but was repeated for different observation times, \(t_\text {data} = \{150, 300, \dots , 1350\}\) days. After applying the IPO procedure, we computed the VOI for each of the nine observation times to compare with the VOI obtained when using conventional robust optimization. In addition to that, we repeated the experiments by considering future availability of clairvoyance instead of imperfect measurements.

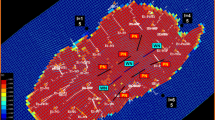

Figure 4 illustrates the motivation for us to select oil rate measurements for this example. It compares the VOC with the value of observing total rates and water-cuts and the value of measuring only oil rates, all obtained by following the conventional optimization approach and displayed in terms of their mean values. We observe that the VOI of total rate and water-cut measurements is very close to the VOC, where the latter represents an upper bound. On the other hand, the VOI of oil rate measurements is considerably lower than the VOC, which suggests that there is room for improvement. The low values, especially for the measurements at \(t_\text {data} = 300\) days, are related to the inability of the oil rate measurements alone to accurately provide information about the water breakthrough time in the producers, whose prediction is paramount to achieve optimal reservoir management in this example. Since our goal here was to verify the potential of our proposed IPO approach to enhance the value produced by the asset, we considered the case with oil rate measurements to be a more suitable case study.

Note that the high VOI of oil rate measurements at \(t_\text {data} = 150\) days is the exception here. This is related to the nature of the waterflooding and decision making (re-optimization) processes. Initially, only oil is present in the system. The injected water flows slowly through the reservoir pores towards the location of the production wells. When the water reaches the production wells (i.e., water breakthrough), the flow of oil starts competing with the flow of water and oil rates start being affected by the fraction of water. This introduces some highly nonlinear effects to the observed response. At \(t_\text {data} = 150\) days, none of the production wells has yet experienced water breakthrough, so oil rate measurements provide better evidence to distinguish the model realizations than oil rate measurements at later times. Besides that, VOI is also a function of the timing of the measurements because a reduction in uncertainty early in time increases the chances of the re-optimization step effectively improving the remaining well controls, which will result in additional value.

Figure 5 shows the results obtained with the IPO approach in comparison to those obtained when using the conventional robust optimization approach. First, we notice that the IPO does not improve significantly the VOC. This happens because, in the unrealistic case of clairvoyance, the revelation of the truth is, by definition, perfect, irrespective of the production strategy that is implemented prior to it. Thus, the gain of using the IPO approach would be more important in cases where the sub-optimality of \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior}}(0\!:\!t_j)\) cannot be compensated by the re-optimization of the remaining degrees of freedom \({\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post}}(t_{j+1}\!:\!T)\) with perfect revelation of the truth, which does not seem to be the case for this example.

On the other hand, for the case with imperfect oil rate measurements, we observe a higher VOI for the IPO approach (Fig. 5). Note that, for the VOI calculation, the values without information are identical for both approaches. This means that the IPO was able to determine production strategies that create more value when applied to the plausible truths. Besides that, this shows that there is indeed room to achieve improved reservoir management by accounting for the availability of future information when searching for the optimal well controls. We highlight the significant increase in VOI obtained for the measurements at \(t_\text {data} = 300\) days, resulting in an improvement of approximately $ 0.8 million.

In order to explain why the strategies determined by the IPO approach are better, we looked also at how they affect the information content of the measurements. For that, we computed the observation impact \(I_{\text {GAI}}\) (Krymskaya et al. 2010) and the uncertainty reduction \(\varDelta \sigma _{\text {NPV}}\) associated with the measurements just like we did in one of our previous papers (Barros et al. 2016a). Figure 6 displays these results for comparison with the VOI in Fig. 5. The observation impact plot indicates that the production strategies obtained with both optimization approaches produce oil rate measurements with similar information content, in terms of predicting its own outcome (i.e. observation self-sensitivity). The results in Fig. 6 (right) also suggest that both optimization approaches perform similarly in terms of producing measurements to reduce the uncertainty (spread) in NPV forecasts. We note, however, an increase in the uncertainty reduction obtained with the IPO approach for the measurements at \(t_\text {data} = 300\) and \(t_\text {data} = 450\) days, which is consistent with the improvement observed in terms of VOI for those observation times (Fig. 5).

Figure 7 shows the production strategies obtained with both optimization approaches for the case considering measurements at \(t_\text {data} = 300\) days, which correspond to the largest improvement in terms of VOI. For both approaches we observe a single production strategy defined until \(t_\text {data} = 300\) days (\({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior}}(0\!:\!300)\) and \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {IPO}}(0\!:\!300)\)) and multiple strategies \({\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post}}\) after that. We notice small differences between the \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior}}\) and \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {IPO}}\) strategies but a reasonable difference in the range of the \({\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post}}\) strategies. Thus, for this example, small changes in \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior}}\) seem to have a significant impact on the optimization of the remaining controls \({\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post}}\).

The re-optimization of \({\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post}}\) is performed over the posterior ensembles which will differ in both optimization approaches because the outcome of the measurements gathered at \(t_\text {data} = 300\) days correspond to the response of the true reservoirs \({\mathbf {m}}^i_{\text {truth}}\) to different well controls \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior}}(0\!:\!300)\) and \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {IPO}}(0\!:\!300)\). The fact that the \({\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post}}\) derived with IPO are more scattered than in conventional optimization indicates that IPO enabled the re-optimization step to better exploit the available flexibility of the remaining degrees of freedom, thus unlocking more value.

We conclude that, for this example, the increase in VOI due to the IPO approach can be partially attributed to the ability of the improved production strategies to yield measurements that result in additional uncertainty reduction in terms of the quantity of interest (NPV). Nevertheless, there seem to be other effects that enable the IPO strategies to perform better for the plausible truths. This could be related to an enhanced controllability of the reservoir states once the measurements reveal some of the initial uncertainty. Overall, these results suggest that, when relying on measurements with limited information content, wrong reservoir management decisions cannot be entirely compensated by re-optimizing the subsequent decisions. In such cases, an approach which is merely reactive to measurements is more likely to result in poorer decisions than an approach that anticipates the availability of future information.

4 Multistage IPO

The results of the example above show that the IPO approach can be valuable for cases with imperfect measurements. However, the procedure depicted in Fig. 3 only addresses the case considering a single observation time, which is not realistic for well production measurements. Therefore, we discuss here what can be done to apply the same reasoning in problems with multiple observation times.

In another of our previous papers (Barros et al. 2015), we showed how our original methodology for VOI assessment can be modified to account for multiple observation times. We demonstrated that, contrary to what one would expect, the computational costs of assessing the value of multiple measurements do not increase beyond reasonable levels. The reason is that, although one might think that we need to consider new additional plausible truths for every observation time, this is not necessary. Once a realization of the initial ensemble is picked to be the plausible truth, the same realization plays the role of truth and the loop is closed as many times as the number of observation times, because that is the only way of ensuring consistency of the synthetic future measurements that we need to generate in order to assess their VOI. Thus, the computational costs of assessing the VOI for multiple observation times is the same as those of the VOI assessment for a single observation time repeated for different observation times, just like what was done in the example above.

Unfortunately, the extension of IPO to cases with multiple observation times is not that simple. In VOI assessment only, the plausible truths are not directly involved in the optimization, but they do play a role in the IPO. Thus, sticking to one of the realizations as the plausible truth throughout all the observation times would imply that we can identify the truth with the measurements obtained at the first observation time, which corresponds to the availability of clairvoyance. Since we are dealing with imperfect measurements, in order to be realistic, we need to update the uncertainty model given by our ensemble of plausible truths. This means that, in principle, the size of the problem grows exponentially with the number of observation times considered, if it is to be solved rigorously. In other words, the number of branches on the scenario tree associated with the problem would be multiplied for every new observation. Figure 8 displays a decision tree for a problem with four observation times where the uncertainty is represented by three new plausible truths each time. We notice the rapid increase in the number of scenarios, which would be even more dramatic if we consider tens of plausible truths and more observation times.

Given the already prohibitive computational costs of VOI assessment, it is safe to say that the rigorous solution of this scenario tree is not feasible for problems relying on reservoir simulation models. Gupta and Grossmann (2011) and Tarhan et al. (2013) have proposed strategies to solve multistage stochastic programming models more efficiently through approximate solutions involving decomposition and constraint relaxation methods.

Here, we propose to use a more intuitive approach to simplify this problem. The first branching before \(t_1\) is the most important one, as it introduces the different plausible truths that will be used to generate the synthetic measurements and to evaluate the performance of the production strategies derived. The second branching before \(t_2\) is also important because it establishes that the respective plausible truth is not perfectly revealed by the imperfect observations made at \(t_1\). However, the branching events associated with the remaining observation times are of smaller importance, because the one at \(t_2\) already guarantees that there are always multiple branches below each plausible truth, reflecting the fact that at any time the uncertainty around the plausible truths is never revealed through unrealistic clairvoyance. This allows us to prune the scenario tree and reduce the size of the problem to be solved for IPO with multiple observation times. Figure 9 shows the pruned scenario tree. Note that after \(t_2\) the number of branches does not increase, which means that, by applying this pruning strategy, we can obtain approximate solutions for three-stage and M-stage stochastic problem at similar computational costs.

To put this idea into practice and extend the two-stage IPO (Fig. 3) to M-stage IPO (with M−1 observation times), we need to make a few changes in the workflow. Figure 10 depicts the modified procedure. First, we introduce an additional ensemble of \(N_{\text {truth}}\) truths \({\mathbf {M}}^i_{\text {truth}}\) for each one of the original plausible truths \({\mathbf {m}}^i_{\text {truth}}\) of our initial ensemble \({\mathbf {M}}_{\text {truth}}\). This corresponds to the second branching of the scenario tree before \(t_2\) (Fig. 9). From there on, the tree does not develop new branches but, for every observation time, \({\mathbf {M}}^i_{\text {truth}}\) is updated through history matching of the synthetic measurements generated with \({\mathbf {m}}^i_{\text {truth}}\). After the last observation, we derive the posterior ensemble of truths \({\mathbf {M}}^i_{\text {truth},M-1}=\{{\mathbf {m}}^{i,1}_{\text {truth}},{\mathbf {m}}^{i,2}_{\text {truth}},\dots ,{\mathbf {m}}^{i,N_{\text {truth}}-1}_{\text {truth}}\}\) and we reach the last decision stage. Like for the two-stage IPO (Fig. 3), the decisions in the last stage are optimized following the conventional robust optimization approach. We use the posterior truths \({\mathbf {m}}^{i,j}_{\text {truth}}\) to generate synthetic measurements and derive the posterior ensembles \({\mathbf {M}}^{i,j}_{\text {post},M-1}\) through history matching. And finally we perform robust optimization over \({\mathbf {M}}^{i,j}_{\text {post},M-1}\). Because we do not introduce additional truth scenarios after the second stage, the nested optimization can group the intermediate stages into a single one. Thus, the M-stage IPO reduces to a nested optimization at three levels: the outer optimization (shown in blue in Fig. 10), the intermediate optimization (in yellow) and the inner optimization (in purple). In the end, the production strategies obtained (\({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {post}}\left( 0\!:\!t_1\right)\) , \({\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post}}\left( t_1\!:\!t_{M-1}\right)\) and \({\mathbf {u}}^{i,j}_{\text {post}}\left( t_{M-1}\!:\!T\right)\)) are applied to the respective original plausible truth \({\mathbf {m}}^i_{\text {truth}}\). We calculate their performances \(J^{i,j}_{\text {post}}\) in terms of our objective function and, finally, we compute the cost function as the mean over all the realizations. Thus, the M-stage IPO problem can be formulated as

where the outcome of the optimization is a single optimal production strategy \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {IPO}}\left( 0\!:\!t_1\right)\) until the first observation time \(t_1\), \(N_{\text {truth}}\) optimal strategies \({\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post}}\left( t_1\!:\!t_{M-1}\right)\), \(i = 1,2,\dots ,N_{\text {truth}}\), for the period between the first and the last observation, and \({N_{\text {truth}}}^2\) optimal strategies \({\mathbf {u}}^{i,j}_{\text {post}}\left( t_{M-1}\!:\!T\right)\), \(i = 1,2,\dots ,N_{\text {truth}}\), \(j = 1,2,\dots ,N_{\text {truth}}\), for the remaining producing time.

The M-stage IPO workflow can be realized in a similar implementation as the one described for our case study. The inner optimization can be performed with the help of the adjoint-based gradients, while the intermediate and outer optimizations can make use of the StoSAG method to estimate the required gradients.

4.1 Example

To test the IPO approach with multiple observation times, we used again the 2D five-spot example, but with a small modification: instead of \(M = 10\), we considered \(M = 3\) control time intervals. We assumed oil production measurements to be available at \(t_\text {data} = \{500, 1000\}\) days, with the same measurement error as before. In order to make the problem more tractable, we used the acceleration measures presented in Barros et al. (2016b), and we reduced the number of plausible truths to \(N^{\text {repr}}_{\text {truth}} = 10\) representative ones and the size of the ensembles for robust optimization to \(N_{\text {repr}} = 5\). The history matching step with the EnKF was performed over the full ensembles.

Figure 11 displays the VOI of the multiple oil rate measurements obtained through the procedure from Barros et al. (2015) with the conventional optimization approach. Figure 11 (bottom) shows that the VOI for the last observation time (\(t_\text {data} = 1000\) days) is significant lower than the VOC, which suggests that there might be scope to improve them with the IPO approach. Thus, the goal of the IPO here can be understood as an optimization of the VOI at \(t_\text {data} = 1000\) days, by maximizing the \(J^{i,j}_{\text {post}}\) achievable through the CLRM framework with the measurements at \(t_\text {data} = \{500, 1000\}\) days.

Figure 12 displays the results obtained in terms of the NPV achieved by the plausible truths. Figure 12 (left) compares the mean NPV for different cases: in red, we have the value attained by the production strategies optimized under prior uncertainty; in blue and in black, the NPV values corresponding to the VOI and VOC at \(t_\text {data} = 1000\) days (Fig. 11); and, in green, the value for the IPO approach. We observe an improvement of approximately $ 55,000 for the mean NPV achieved with the IPO (green) in comparison with the mean NPV for the CLRM using the conventional optimization approach, which represents an increase of 0.1%, or of 4% if expressed in terms of VOI. We note that the incremental gain is small but should be understood as an attempt to improve a solution already close to optimal for this example. This suggests that, in this example with more observations, the CLRM framework with the conventional optimization approach was able to sufficiently compensate for previous suboptimal decisions, resulting in production strategies almost as good as the ones determined through IPO.

Figure 12 (right) depicts the same results but showing the empirical probability distribution function (pdf) curves derived with the NPV of the \(N^{\text {repr}}_{\text {truth}}\) = 10 plausible truths considered. The differences between the curves for the CLRM and IPO are small. However, the distribution for the IPO approach seems to achieve higher values at its peak, which suggests a reduction in the spread of the NPV values. Note that the pdf curves displayed here are the result of curve fitting with a small number of samples (\(N^{\text {repr}}_{\text {truth}} = 10\)), but that the empirical histograms exhibit similar trends (Fig. 12 (bottom)).

Figure 13 shows the production strategies determined by the different approaches compared in Fig. 12. A single production strategy \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior}}\left( 0\!:\!500\right)\) is derived for the conventional robust optimization approach. On the other extreme, a different optimal strategy is determined for each of the \(N^{\text {repr}}_{\text {truth}} = 10\) plausible truths considered, under the assumption of clairvoyance at \(t = 0\). In between, for the CLRM, the solutions obtained consist of the same single strategy as \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior}}\left( 0\!:\!500\right)\) for the first control time interval, and \(N^{\text {repr}}_{\text {truth}} = 10\) different strategies \({\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post}}\left( 500\!:\!1500\right)\) for the remaining of the time. Finally, we see the outcome of the IPO for this three-stage problem: a single optimal production strategy \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {IPO}}\left( 0\!:\!500\right)\) until the first observation time \(t_1 = 500\) days, \(N^{\text {repr}}_{\text {truth}} = 10\) optimal strategies \({\mathbf {u}}^i_{\text {post}}\left( 500\!:\!1000\right)\), \(i = 1,2,\dots ,N^{\text {repr}}_{\text {truth}}\), for the period between \(t_1 = 500\) and \(t_2 = 1,000\) days, and \(\left( N^{\text {repr}}_{\text {truth}}\right) ^2 = 100\) optimal strategies \({\mathbf {u}}^{i,j}_{\text {post}}\left( 1000\!:\!1500\right)\), \(i = 1,2,\dots ,N^{\text {repr}}_{\text {truth}}, j = 1,2,\dots ,N^{\text {repr}}_{\text {truth}}\), from \(t_2 = 1,000\) until \(T = 1,500\) days. The larger number of possibilities associated with future control time intervals allows the IPO strategies to account for the flexibility of the reservoir management problem. We also note that \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {IPO}}\left( 0\!:\!500\right)\) is not the same as \({\mathbf {u}}_{\text {prior}}\left( 0\!:\!500\right)\) and that the difference between them enables the IPO approach to result in improved NPV values, as seen in Fig. 12.

Optimal production strategies for the plausible truths considered (2D five-spot model with \(M = 3\) control time intervals): optimized under prior uncertainty (top left); obtained through CLRM with additional production measurements (top right); determined by the IPO approach with future production measurements (bottom left); optimized under the assumption of clairvoyance available at \(t = 0\) (bottom right)

5 Discussion and conclusions

We have proposed a new approach for production optimization under geological uncertainty. The informed production optimization (IPO) approach considers the endogenous nature of these uncertainties and includes the availability of future information to circumvent the limitations of the conventional robust optimization. To achieve this, the approach accounts for the fact that there is uncertainty about the optimal well settings to be implemented after additional measurements are processed in the future, and that this uncertainty depends on the outcome of these measurements. As a consequence, we perform robust IPO over an ensemble of plausible truths resulting in a single optimal production strategy until the moment that future measurements take place and a range of optimal production strategies for the period after them. We applied IPO to a simple case study, which resulted in a significant increase of the VOI obtained from imperfect measurements, reflecting the improvement in the production optimization. After demonstrating the potential value of the IPO approach for a case with a single observation time, we discussed how it can be extended to situations with multiple observation times and we applied it to the same simple example in a three-stage decision problem. The improvements achieved were more modest, which suggests that, with more measurements, the CLRM framework with the conventional optimization approach was able to make up for previous suboptimal decisions, at least for this example. Based on the results of these examples, we conclude that IPO can improve the way we approach the reservoir management problem, especially in situations where wrong decisions cannot be entirely compensated by the remaining degrees of freedom in the control problem.

An important point that has not been addressed in this work concerns the generation of future synthetic measurements and, in particular, the contribution of the measurement noise. Here we assumed white noise with a pre-defined standard deviation to be added to the simulated measurements, but, in practice, other choices may be more appropriate. Although, in most of the cases, small when compared to the geological uncertainties, this noise contribution may have an impact on the results obtained with the proposed IPO approach. Further research is required for a better understanding of its impact.

Another point for future work concerns the computational costs of such an approach, which are comparable or higher than those of VOI assessment workflows. The IPO ideas only make sense if uncertainty quantification is addressed carefully, and this may require a prohibitive amount of reservoir simulations. For example, in the results for two-stage IPO (Fig. 5), the IPO workflow required approximately \(0.5-1 \times 10^6\) (forward and backward) reservoir simulations for each \(t_\text {data}\) (depending on how many iterations of the outer optimization are performed), compared to approximately \(0.1 \times 10^6\) simulations for the VOI assessment workflow from Barros et al. (2016a). In order to be useful, the IPO needs to be tractable. In one of our previous papers (Barros et al. 2016b) we managed to reduce the number of reservoir simulations required in VOI workflows by selecting representative models, a solution that can also be applied here. Besides that, the use of proxy models or multiscale methods may help to further reduce the number of high-fidelity reservoir simulations needed and make the IPO procedure more practical. Still regarding the tractability of the problem, the procedure we proposed here to extend the IPO approach to cases with multiple observation times represents an approximation of the full multistage stochastic model. There may be other solutions to prune the decision tree and effectively reduce the problem to fewer relevant scenarios, as, e.g., suggested by Gupta and Grossmann (2011) and Tarhan et al. (2013). Therefore, also in this direction there is scope for future research.

References

Abreu ACA, Booth R, Bertolini A, Prange M, Bailey WJ, Teixeira G, Romeu RK, Emerick AA, Pacheco MAC (2015) Proactive and reactive strategies for optimal operational design: an application in smart wells. In: Paper OTC-26209-MS presented at the offshore technology conference Brazil, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 27–29 October

Barros EGD, Leeuwenburgh O, Van den Hof PMJ, Jansen JD (2015) Value of multiple production measurements and water front tracking in closed-loop reservoir management. In: Paper SPE-175608-MS presented at the SPE reservoir characterization and simulation conference and exhibition, Abu Dhabi, UAE, 14–16 September

Barros EGD, Van den Hof PMJ, Jansen JD (2016a) Value of information in closed-loop reservoir management. Comput Geosci 20(3):737–749

Barros EGD, Yap FK, Insuasty Moreno E, Van den Hof PMJ, Jansen JD (2016b) Clustering techniques for value-of-information assessment in closed-loop reservoir management. In: Paper presented at the 15th European conference on mathematics in oil recovery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 29 August–1 September

Birge JR, Louveaux F (1997) Introduction to stochastic programming. Springer, New York

Capolei A, Suwartadi E, Foss B, Jrgensen JB (2015) A mean-variance objective for robust production optimization in uncertain geological scenarios. J Pet Sci Eng 125:23–37

Chen Y, Oliver DS, Zhang D (2009) Efficient ensemble-based closed-loop production optimization. SPE J 14(4):634–645

Feldbaum AA (1960) Dual control theory I–II. Autom Remote Control 21(9):874–880

Feldbaum AA (1961) Dual control theory III–IV. Autom Remote Control 22(11):109–121

Fonseca RM, Chen B, Jansen JD, Reynolds AC (2016) A stochastic simplex approximate gradient (StoSAG) for optimization under uncertainty. Accepted for publication in International Journal for Numerical Methods in Engineering

Forgione M, Birpoutsoukis G, Bombois X, Mesbah A, Daudey PJ, Van den Hof PMJ (2015) Batch-to-batch model improvement for cooling crystallization. Control Eng Pract 41:72–82

Foss B, Jensen JP (2011) Performance analysis for closed-loop reservoir management. SPE J 16:183–190

Georghiou A, Wiesemann W, Kuhn D (2011) The decision rule approach to optimisation under uncertainty: methodology and applications in operations management. Available on Optimization Online, submitted for publication

Goel V, Grossmann IE (2004) A stochastic programming approach to planning of offshore gas field developments under uncertainty in reserves. Comput Chem Eng 28(8):1409–1429

Gupta V, Grossmann IE (2011) Solution strategies for multistage stochastic programming with endogenous uncertainties. Comput Chem Eng 35(11):2235–2247

Hanssen KG (2017) Optimal control under uncertainty Applied to upstream petroleum production. Ph.D. thesis, Norwegian University of Science and Technology

Hanssen KG, Codas A, Foss B (2017) Closed-loop predictions in reservoir management under uncertainty. SPE J 22(5):1585–1595

Hauskrecht M (2000) Value-function approximations for partially observable Markov decision processes. J Artif Intell Res 13:33–94

Hou J, Zhou K, Zhang XS, Kang XD, Xie H (2015) A review of closed-loop reservoir management. Pet Sci 12:114–128

Jansen JD, Brouwer DR, Nvdal G, van Kruijsdijk CPJW (2005) Closed-loop reservoir management. First Break, January, 23, pp 43–48

Jansen JD, Bosgra OH, van den Hof PMJ (2008) Model-based control of multiphase flow in subsurface oil reservoirs. J Process Control 18:846–855

Jansen JD, Douma SG, Brouwer DR, Van den Hof PMJ, Bosgra OH, Heemink AW (2009) Closed-loop reservoir management. In: Paper SPE 119098 presented at the SPE reservoir simulation symposium, The Woodlands, USA, 2–4 February

Jonsbråten TW (1998) Optimization models for petroleum field exploitation. Ph.D. thesis, Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration

Krause A, Guestrin C (2007) Nonmyopic active learning of Gaussian processes: an exploration-exploitation approach. In: Proceedings 24th annual international conference on machine learning, Corvallis, USA, 20–24 June

Krause A, Guestrin C (2009) Optimal value of information in graphical models. J Artif Intell Res 35:557–591

Krymskaya MV, Hanea RG, Jansen JD, Heemink AW (2010) Observation sensitivity in computer-assisted history matching. In: Paper presented at the 72nd EAGE Conference and exhibition, Barcelona, Spain, 14–17 June

Lie K-A, Krogstad S, Ligaarden IS, Natvig JR, Nilsen HM, Skalestad B (2012) Open source MATLAB implementation of consistent discretisations on complex grids. Comput Geosci 16(2):297–322

Mirrokni V, Thain N, Vetta A (2012) A theoretical examination of practical game playing: lookahead search. In: Serna,M. (ed.) SAGT 2012. LNCS, 7615, pp 251–262. Springer, Heidelberg

Naevdal G, Brouwer DR, Jansen JD (2006) Waterflooding using closed-loop control. Comput Geosci 10(1):37–60

Ruszczyski A, Shapiro A (2003) Stochastic programming. Handbooks in operations research and management science. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Sarma P, Durlofsky LJ, Aziz K (2008) Computational techniques for closed-loop reservoir modeling with application to a realistic reservoir. Pet Sci Technol 26(10 and 11):1120–1140

Siraj MM, Van den Hof PMJ, Jansen JD (2016) Robust optimization of water-flooding in oil reservoirs using risk management tools. In: Paper presented at the 11th IFAC symposium on dynamics and control of process systems

Smallwood RD, Sondik EJ (1973) The optimal control of partially observable Markov processes over a finite horizon. Oper Res 21(5):1071–1088

Tarhan B, Grossmann IE, Goel V (2013) Computational strategies for non-convex multistage MINLP models with decision-dependent uncertainty and gradual uncertainty resolution. Ann Oper Res 203:141–166

Van Essen GM, Zandvliet MJ, Van den Hof PMJ, Bosgra OH, Jansen JD (2009) Robust waterflooding optimization of multiple geological scenarios. SPE J 14(1):202–210

Van Hessem DH (2004) Stochastic inequality constrained closed-loop model predictive control with application to chemical process operation. Ph.D. thesis, Delft University of Technology

Wang C, Li G, Reynolds AC (2009) Production optimization in closed-loop reservoir management. SPE J 14(3):506–523

Yeten B, Durlofsky LJ, Aziz K (2003) Optimization of nonconventional well type, location and trajectory. SPE J 8(3):200–210

Zenith F, Foss BA, Tjønnås J, Hasan AI (2015) Well testing by sinusoidal stimulation. SPE Reserv Eval Eng 18(3):441–451

Acknowledgements

This research was carried out within the context of the ISAPP Knowledge Centre. ISAPP (Integrated Systems Approach to Petroleum Production) is a joint project of TNO, Delft University of Technology (TU Delft), ENI, Statoil and Petrobras. The EnKF module for MRST was developed by Olwijn Leeuwenburgh (TNO). The implementation of the StoSAG method was developed by Rahul Fonseca.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Barros, E.G.D., Van den Hof, P.M.J. & Jansen, J.D. Informed production optimization in hydrocarbon reservoirs. Optim Eng 21, 25–48 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11081-019-09432-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11081-019-09432-7