Abstract

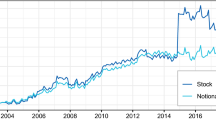

Monetary aggregates have a special role under the “two pillar strategy” of the ECB. Hence, a theoretically consistent measure of monetary aggregates for the European Monetary Union (EMU) is needed. This paper analyzes aggregation over monetary assets for the EMU. We aggregate over the monetary services for the eleven EMU (EMU-11) countries, which include Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Slovakia, and Slovenia. We adopt the Divisia monetary aggregation approach, which is consistent with index number theory and microeconomic aggregation theory. The result is a multilateral Divisia monetary aggregate, in accordance with Barnett (J Econ 136(2):457–482, 2007). The multilateral Divisia monetary aggregate for the EMU-11 is found to be more informative and a better signal of economic trends than the corresponding simple sum aggregate. We then analyze substitutability among monetary assets for the EMU-11 within the framework of a representative consumer’s utility function, using Barnett’s (J Bus Econ Stat 1:7–23, 1983) locally flexible functional form, the minflex Laurent indirect utility function. The analysis of elasticities with respect to the asset’s user-cost prices shows that: (i) transaction balances and deposits with agreed maturity are income elastic and (ii) the monetary assets are not good substitutes for each other within the EMU-11. Simple sum monetary aggregation assumes that component assets are perfect substitutes. Hence simple sum aggregation distorts measurement of the monetary aggregate. The ECB provides Divisia monetary aggregates to the Governing Council at its meetings, but not to the public. Our European Divisia monetary aggregates will be expanded and refined, in collaboration with Wenjuan Chen at the Humboldt University of Berlin, to a complete EMU Divisia monetary aggregates database to be supplied to the public by the Center for Financial Stability in New York City.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

References

Anderson RG and BE Jones (2011) A comprehensive revision of the US monetary services (Divisia) indices. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review 83(1):51–72

Barnett WA (1978) The user cost of money. Economics Letters 1, 145--149. In: Barnett WA, Serletis A (eds) The Theory of Monetary Aggregation. (Reprinted). Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 6–10

Barnett WA (1980) Economic monetary aggregates: an application of aggregation and index number theory. Journal of Econometrics 14, 11--48. In: Barnett WA, Serletis A (eds) The Theory of Monetary Aggregation, (Reprinted). Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 11–48

Barnett WA (1983) New indices of money supply and the flexible Laurent demand system. J Bus Econ Stat 1:7–23

Barnett WA 2003 Aggregation-theoretic monetary aggregation over the euro area, when countries are heterogeneous. European Central Bank Working Paper no. 260. Frankfurt

Barnett WA (2007) Multilateral aggregation-theoretic monetary aggregation over heterogeneous countries. J Econ 136(2):457–482

Barnett WA (2012) Getting it wrong. How Faulty Monetary Statistics Undermine the Fed, the Financial System, and the Economy. The MIT Press, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge

Barnett WA, Chauvet M (2011) How better monetary statistics could have signaled the financial crisis. J Econ 161(1):6–23

Barnett WA, Lee YW (1985) The global properties of the minflex Laurent, generalized Leontief, and translog flexible functional forms. Econometrica 53:1421–1437

Barnett WA, Offenbacher EK, Spindt PA (1981) New concepts of aggregated money. J Financ 36:497–505

Barnett WA, Offenbacher EK, Spindt PA (1984) The new Divisia monetary aggregates. J Polit Econ 92:1049–1085

Barnett WA, Liu J, Mattson RS, van den Noort J (2013) The new CFS Divisia monetary aggregates: design, construction, and data sources. Open Econ Rev 24:101–124

Barten AP (1969) Maximum likelihood estimation of a complete system of demand equations. Eur Econ Rev 1:7–73

Belongia MT, Ireland PN (2006) The own-price of money and the channels of monetary transmission. J Money, Credit, Bank 38:429–445

Belongia MT, Ireland PN (2014) The Barnett critique after three decades: a new Keynesian analysis. J Econ 183(1):5–21

Belongia MT, Ireland PN (2015a) Interest rates and money in the measurement of monetary policy. J Bus Econ Stat 332:255–269

Belongia MT, Ireland PN (2015b) A ‘working’ solution to the question of nominal GDP targeting. Macroecon Dyn 19:508–534

Belongia MT, Ireland PN (2016) Money and output: Friedman and Schwartz revisited. J Money Credit Bank 48(6):1223–1266

Beyer A (2008) Euro Area Money Demand is Stable, Mimeo presented at NCB Expert Workshop, Frankfurt am Main, 14 November

Blackorby C, Russell RR (1989) Will the real elasticity of substitution please stand up? Am Econ Rev 79:882–888

Boone L, Mikol F, Van den Noord P (2004) Wealth Effects on Money Demand in EMU: Econometric Evidence, OECD Economics Department Working Papers 411

Bruggeman A, Camba-Mendez G, Fischer B, Sousa J (2005) Structural filters for monetary analysis: the inflationary movements of money in the euro area, ECB Working Paper no. 470

Chan W, Nautz D (2015) The information content of monetary statistics for the Great Recession: Evidence from Germany. SFB 649 Discussion Paper 2015–027

Cherchye L, Demuynck T, Rock BD, Hjerstrand P (2015) Revealed preference tests for weak Separability: an integer programming approach. J Econ 186(1):129–141

Darvas Z (2015) Does money matter in the euro area? Evidence from a new Divisia index. Econ Lett 133:123–126

Fisher I (1922) The making of index numbers: a study of their varieties, tests, and reliability. Houghton Mifflin, Boston

Gerlach S, Assenmacher-Wesche K (2006) Interpreting euro area inflation at high and low frequencies. BIS Working Paper no. 195

Gorman WM (1959) Separable utility and aggregation. Econometrica 27:469–481

Hjertstrand P, Swofford JL, Whitney G (2016) Mixed integer programming revealed preference tests of utility maximization and weak Separability of consumption, leisure, and money. J Money, Credit, Bank 48(7):1547–1561

Neumann MJM, Greiber C (2004) Inflation and core money growth in the euro area. Bundesbank Discussion Paper no. 36/2004

Rayton BA, Pavlyk K (2010) On the recent divergence between measures of the money supply in the UK. Econ Lett 108(2):159–162

Serletis A, Gogas P (2014) Divisia monetary aggregates, the great ratios, and classical money demand functions. J Money Credit Bank 46(1):229–241

Serletis A, Rahman S (2013) The case for Divisia money targeting. Macroecon Dyn 17:1638–1658

Serletis A, Robb AL (1986) Divisia aggregation and substitutability among monetary assets. J Money, Credit, Bank 18:430–446

Serletis A, Shahmoradi A (2005) Seminonparametric estimates of the demand for money in the United States. Macroecon Dyn 9(4):542–559

Serletis A, Shahmoradi A (2007) Flexible functional forms, curvature conditions, and the demand for assets. Macroecon Dyn 11:455–486

Stracca L (2004) Does liquidity matter? Properties of a Divisia monetary aggregate in the euro area. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 66(3):309–331

Strotz RH (1957) The empirical implications of a utility tree. Econometrica 25:169–180

Strotz RH (1959) The utility tree: a correction and further appraisal. Econometrica 27:482–488

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Definitions:

Monetary and financial institutions (MFI) from the ECB Glossary: MFIs are Central Bank, resident credit institutions as defined by community law, and other resident financial institutions whose business is to receive deposits and /or close substitutes for deposits from entities other than MFIs and for their own account to grant credits and/or make investments in securities.

Overnight deposits from the ECB Glossary, deposits with next-day maturity: This instrument category comprises mainly those sight/demand deposits that are fully transferable by check or similar instrument. It also includes non-transferable deposits that are convertible on demand or by close of business the following day. Overnight deposits are included in M1 and hence in M2 and M3.

Deposits redeemable at notice (DRN) from the ECB Glossary: These deposits are savings deposits for which the holder must respect a fixed period of notice before withdrawing the funds. In some cases there is the possibility of withdrawing on demand a certain fixed amount in a specified period or of early withdrawal subject to the payment of a penalty. Deposits redeemable at a period of notice up to three months are included in M2 and hence in M3, while those with a longer period of notice are part of the non-monetary longer term financial liabilities of the MFI sector.

Deposits with an agreed maturity (DAM) from the ECB Glossary: These deposits are mainly time deposits with a given maturity that, depending on national practices, may be subject to the payment of a penalty in the event of early withdrawal. Some non-marketable debt instruments, such as non-transferable retail certificates of deposit, are also included. Deposits with an agreed maturity of up to two years are included in M2 and hence in M3, while those with an agreed maturity of over two years are included in the non-monetary long term financial liabilities of the MFI sector.

Non-profit institutions serving households (NPISH) from the Eurostat Glossary: These institutions make up an institutional sector in the context of national accounts consisting of non-profit institutions which are not mainly financed and controlled by government and which provide goods or services to households for free or at prices that are not economically significant. Examples include churches and religious societies, sports and other clubs, trade unions, and political parties. NPISH are private, non-market producers which are separate legal entities. Their main resources, apart from those derived from occasional sales, are derived from voluntary contributions in cash or in kind from households in their capacity as consumers, from payments made by general governments, and from property income.

Non-financial corporation (NFC) from the ECB Glossary: These firms are corporation or quasi-corporation that is not engaged in financial intermediation but is active primarily in the production of market goods and non-financial services.

Appendix 2

The M1 monetary aggregate contains the most liquid monetary asset components. The ECB has defined the M1 monetary aggregate to include currency in circulation and overnight deposits. Overnight deposits are deposits with next-day maturity and comprises mainly of sight deposits or demand deposits which are fully transferable by check or similar instruments. The ECB definition of the M2 aggregate includes currency in circulation, overnight deposits, deposits with agreed maturity (DAM) up to 2 years and deposits redeemable at notice (DRN) up to 3 months. The data on currency in circulation is taken from the individual countries’ central banks, as currency held by banks. The ECB website does not provide the data on currency in circulation. The data for the outstanding amount of OD, DAM, and DRN are for the households and non-profit institutions serving households. The data for the interest rate for OD, DAM and DRN are the Monetary Financial Institutions (MFI) interest rates for the households and non-profit institutions serving households. Currency is assumed is to have a zero own rate of return. The outstanding amount and interest rate data for OD, DAM and DRN are from the ECB Data Warehouse.

The benchmark rate is the expected rate of return received on a pure investment providing no services other that its yield. In short, the benchmark rate is the rate of return on pure capital. Since it provides no services other than its yield, the benchmark rate must be at least as high as the upper envelope over all the monetary aggregate’s component yield-curve-adjusted rates of return. In that upper envelope, we also include the interest rate on loans of maturity of up to one year.

In case of a few countries like Finland, France, and the Netherlands, the interest rate on deposits with agreed maturity of 2 years was greater than the loan rate for a few months. For those periods, 100 basis points were added to the upper envelope to keep the user costs from becoming zero. This procedure is in accordance with Anderson and Jones (2011). In the case of Finland, the interest rate on DAM was higher than the loan rate for two periods of up to one year. For DAM and DRN, those periods were January 2009 to September 2009 and March 2012 to October 2012. For those periods, 0.01 point is added to the loan rate, so that the benchmark rate is highest of all the rates of return on monetary assets. The corresponding periods for France are March 2009 to January 2011 and December 2011 to January 2011. For the Netherlands, the periods are January 2009 to June 2010 and January 2012 to October 2013.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barnett, W.A., Gaekwad, N.B. The Demand for Money for EMU: a Flexible Functional Form Approach. Open Econ Rev 29, 353–371 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-017-9453-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-017-9453-0

Keywords

- Divisia monetary aggregation

- European monetary union

- Monetary aggregation theory

- Multilateral aggregation

- Minflex Laurent

- Elasticities of demand