Abstract

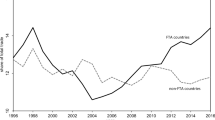

This paper empirically investigates how far free trade agreements (FTAs) successfully lower tariff rates and non-tariff barriers (NTBs) for manufacturing industries by employing the bilateral tariff and NTB data in time series for countries in the world. We find that FTAs under GATT Article XXIV and the Enabling Clause are associated with the 2.0 and 1.5 % lower tariff rates, respectively. In the case of NTBs, on the other hand, their respective effects are 2.1 and 2.4 %. Also, compared with these effects of FTAs, WTO membership does not have large effects on tariff rates but does have them on NTBs. These results provide important implication for the literature on the numerical assessment of FTAs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In this paper, “FTAs” refer to reciprocal trade agreements between two or more partners and those categorized as regional trade agreements (RTAs) in the world trade organization (WTO). It includes not only RTAs under GATT Article XXIV but also those based on the Enabling Clause.

Several studies by Andrew Rose cannot find robust positive impacts of WTO membership. Engelbrecht and Pearce (2007) and Subramanian and Wei (2007) analyze the impacts of the WTO membership on agricultural trade and find negatively significant impacts. Tomz, Goldstein, and Rivers (2007) conduct a careful gravity analysis by including zero trade and controlling for multilateral resistance but do not find robust positive impacts of WTO membership. On the other hand, Chang and Lee (2007) employ the propensity score matching method to tackle endogeneity and specification errors in gravity exercises. As a result, they find robust positive impacts of WTO membership on trade.

In the TRAINS database, most of the countries report applied rates rather than bound rates for MFN rates. When both applied and bound rates are available, we use the applied rates since our main purpose is to examine how far FTAs contribute to reducing actually-imposed tariff rates.

Namely, we assume that exporters always use the schemes with the lowest tariff rates though, in the real world, some exporters may be forced to use higher general tariff rates, such as MFN rates, because some compliance costs would be incurred in using preferential tariff schemes (Demidova and Krishna 2008).

We notice a long-lasting discussion on pros and cons of the tariff-rate aggregation methods, either taking simple averages or calculating trade-value-weighted averages, both of which necessarily generate specific biases, possibly affected by complicated political economy in trade negotiations. One reason for applying simple averages is that this study focuses on reductions in tariff rates rather than measuring effects of tariff reductions on international trade. Another reason is to economize our empirical study. Although it is not logically impossible to calculate trade value-weighted averages, the calculation is extremely cumbersome particularly because our study uses by-commodity bilateral tariffs in the large number of countries over a long time period with frequent changes in commodity classification for tariffs and trade data.

The conversion table is available at http://unstats.un.org/unsd/cr/registry/regdnld.asp?Lg=1.

For more details on the construction of the tariff database, see Hayakawa (2013).

For more details, see “Note for Users,” which is available on the following website:

http://www.unescap.org/tid/artnet/db/usernote-2012.pdf .

Another famous NTB measure includes Trade Restrictiveness Indices provided in Kee et al. (2009). However, this measure is available by country, not by country-pair and thus not suitable for our analysis on the effects of FTAs. Also, for other measures on NTBs, see Anderson and van Wincoop (2004).

Thus, our NTB measure might contain biases if any systematic relationship between liberalized products and those trade values exists due to political economy of trade liberalization.

It should also be noted that if a systematic relationship exists between FTA rates and MFN rates, our estimates would suffer from some biases. However, the literature has not shared a common understanding of the direction of such biases yet. For example, while Limao (2006) and Karacaovali and Limao (2008) find that the reduction on MFN rates is smaller in the products with the lower FTA preferential rates, Estevadeordal et al. (2008) and Baldwin and Seghezza (2010) show the opposite results.

Nevertheless, there still remain possible endogeneity sources in our FTA variable, which make our estimates difficult to show the causal effects of FTAs. Thus, we need to carefully interpret our estimates.

As in the previous studies listed in the introductory section, our identification strategy for WTO effects is to quantify tariff/NTBs changes in a limited number of countries that joined WTO during our sample period though such changes in those countries may not fully reflect the overall effects of being WTO members.

Information on BIT is available from the following UNCTAD website:

OECD countries include Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, United Kingdom, and United States.

MFN rates are recorded as “general rates” before accession in the TRAINS database.

The data on NTBs are not available by industry.

This result in tobacco may be due to the effects of WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC), which entered into force in 2005 and encouraged a large number of countries to strengthen various kinds of restrictions on tobacco including tariff rates in the latter half of the 2000s. Such countries include those that joined in WTO after 2005. As a result, our estimates on the WTO effects on tariff rates in tobacco products may capture such a rise of tariff rates through the WHO FCTC.

One may notice that, unlike the results in the previous tables, some coefficients for one-year lagged FTA dummy are insignificant in figures. However, the “control group” is different between this estimation and the others. The FTA coefficient in the specification in the previous tables indicates the differences in tariff rates/NTBs between one year after the entry and all of the other years including two years after the entry. On the other hand, the coefficient for one-year lagged FTA dummy in these figures shows differences from the average among years before the entry, entry year, and over-11 years after the entry. Thus, the differences in the results in one-year lagged FTA dummy may indicate that the effects one year after the entry are larger than the average effects among two to ten years after the entry.

The trade promotion through FTAs will result in establishing many new trade relationships/networks among firms in member countries. If those establishment leads to the self-creation of the further relationships/networks, such effects will appear as the lagged effects of FTAs on NTBs. However, we cannot differentiate such indirect effects with other effects of FTAs on NTBs.

For example, Felbermayr and Jung (2011) examine the effects of standardizing technical requirements on industry-level productivity.

References

Anderson JE, van Wincoop E (2004) Trade costs. J Econ Lit 42(3):691–751

Ando M (2009) Impacts of FTAs in East Asia: CGE simulation analysis. RIETI Discussion Paper Series 09-E-037

Bagwell K, Staiger R (2011) What do trade negotiators negotiate about? empirical evidence from the world trade organization. Am Econ Rev 101(4):1238–1273

Baier SL, Bergstrand JH (2007) Do free trade agreements actually increase members’ international trade? J Int Econ 71(1):72–95

Baldwin R, Seghezza E (2010) Are trade blocs building or stumbling blocs? J Econ Integr 25:276–297

Baldwin RE, Venables AJ (1995) Regional economic integration. In: G.M. Grossman et al. (Eds.) Handbook of international economics, Volume 3, North-Holland, pp. 1597–1644

Caporale G, Rault C, Sova R, Sova A (2009) On the bilateral trade effects of free trade agreements between the EU-15 and the CEEC-4 countries. Rev World Econ 145(2):189–206

Chang PL, Lee MJ (2007) The WTO trade effect. J Int Econ 85(1):53–71

Demidova S, Krishna K (2008) Firm heterogeneity and firm behavior with conditional policies. Econ Let 98:122–128

Engelbrecht H, Pearce C (2007) The GATT/WTO has promoted trade, but only in capital-intensive commodities! Appl Econ 39(12):1573–1581

Estevadeordal A, Freund C, Ornelas E (2008) Does regionalism affect trade liberalization toward nonmembers? Q J Econ 123(4):1531–1575

Felbermayr G, Jung B (2011) Sorting it out: technical barriers to trade and industry productivity. Open Econ Rev 22(1):93–117

Hayakawa K (2013) How serious is the omission of bilateral tariff rates in gravity? J Jpn Int Econ 27:81–94

Karacaovali B, Limao N (2008) The clash of liberalizations: preferential vs. multilateral trade liberalization in the European union. J Int Econ 74(2):299–327

Kee HL, Nicita A, Olarreaga M (2009) Estimating trade restrictiveness indices. Econ J 119(534):172–199

Limao N (2006) Preferential trade agreements as stumbling blocks for multilateral trade liberalization: evidence for the United States. Am Econ Rev 96(3):896–914

Medvedev D (2010) Preferential trade agreements and their role in world trade. Rev World Econ 146:199–222

Novy D (2013) Gravity redux: measuring international trade costs with panel data. Econ Inq 51(1):101–121

Park I, Soonchan P (2009) Consolidation and harmonization of regional trade agreements (RTAs): a path toward global free trade, MPRA Paper, No. 14217

Petri AP, Plummer MG, Zhai F (2011) The trans-pacific partnership and Asia-Pacific integration: A quantitative assessment, East–west Center Working Papers, No. 119

Plummer M, Wignaraja G (2006) The post-crisis sequencing of economic integration in Asia: trade as a complement to a monetary future. Econ Int 107:59–85

Rose A (2004a) Do we really know that the WTO increases trade? Am Econ Rev 91(1):98–114

Rose A (2004b) Do WTO members have more liberal trade policy? J Int Econ 63(2):209–235

Rose A (2005a) Which international institution promote international trade? Rev Int Econ 13(4):682–698

Rose A (2005b) Does the WTO make trade more stable? Open Econ Rev 16(1):7–22

Roy J (2010) Do customs union members engage in more bilateral trade than free-trade agreement members? Rev Int Econ 18(4):663–681

Subramanian A, Wei S (2007) The WTO promotes trade, strongly but unevenly. J Int Econ 72(1):151–175

Tomz M, Goldstein J, & Rivers, D. (2007) Membership has its privileges: Understanding the effects of the GATT/WTO, unpublished.

Vicard V (2009) On trade creation and regional trade agreements: does depth matter? Rev World Econ 145:167–187

Winchester N (2009) Is there a dirty little secret? Non-tariff barriers and the gains from trade. J Policy Model 31(6):819–834

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted as part of a project of the Institute of Developing Economies called “Comprehensive Analysis on Consequence of Trade and Investment Liberalization in East Asia”.

We thank two anonymous referees for their helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hayakawa, K., Kimura, F. How Much Do Free Trade Agreements Reduce Impediments to Trade?. Open Econ Rev 26, 711–729 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-014-9332-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-014-9332-x