Abstract

In this paper, the general kinematics and dynamics of a rigid body is analysed, which is in contact with two rigid surfaces in the presence of dry friction. Due to the rolling or slipping state at each contact point, four kinematic scenarios occur. In the two-point rolling case, the contact forces are undetermined; consequently, the condition of the static friction forces cannot be checked from the Coulomb model to decide whether two-point rolling is possible. However, this issue can be resolved within the scope of rigid body dynamics by analysing the nonsmooth vector field of the system at the possible transitions between slipping and rolling. Based on the concept of limit directions of codimension-2 discontinuities, a method is presented to determine the conditions when the two-point rolling is realizable without slipping.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In modelling and analysis of mechanical systems, one of the most challenging issues is the contact problem between the bodies, which leads to nonsmooth effects. The nonsmoothness originates from two physical sources, from the unilateral property of the normal contact forces, and from the dry friction characteristics of the tangential contact forces.

At the tangential contact of rigid bodies, we distinguish a slipping contact state and a static contact state which includes sticking or rolling. By assuming deformations at the contact, these states are defined locally, and the cumulated friction effect can be computed numerically or can be interpreted by different contact models [13, 14]. However, when the stiffnesses of the contacting bodies are large enough, the rigid body model is an acceptable assumption, and at the contact state of the discrete contact point, we can sharply distinguish the slipping and rolling–sticking cases. Then, the Coulomb model and similar dry friction models include both a constraint of rolling–sticking and a force law of slipping (see [16, 17], or [21] for an overview). These models include the conditions of the transitions between the two states, as well; these transitions change not just the equations but also the dimension of the resulting dynamical systems.

As constraints are included in the friction models, the presence of multiple contact points brings out many issues related to multiple contacts, including the indeterminacy of contact forces. This scenario occurs already at a single three-dimensional rigid body with two contact points, which is the main topic of this paper.

When a rigid body is in contact with two rigid surfaces, four different contact states are possible from the combination of rolling and slipping at each contact point. It can be shown that at two-point rolling, the contact forces are undetermined, which makes it impossible to check the limitations of friction forces, and thus, to determine the transition into slipping. It seems that the problem is beyond the available tools of rigid body mechanics, and one should include models with elastic deformation to resolve the indeterminacy and to get a complete description of the problem. However, the indeterminacy can be avoided within the rigid body model: by careful analysis of the vector field of the resulting dynamical system, it is possible to find the trajectories of slipping–rolling transitions without calculating the missing contact forces. For this approach, we use the tools of analysis of codimension-2 discontinuities of vector fields, which was presented in [3] and [4].

The scenario of a rigid body with two contact points can be found in several mechanical applications, such as the railway wheelsets [2, 11, 19], the rolling elements of bearings [10, 20, 29], the compressed elements of the tensegrity structures [24], or in the rotating ball flowmeter [7, 23], which was analysed by the authors in [1]. The example of a ball with two contact points has been recently used for demonstrating a new approach of friction models [26].

The paper is organized as follows: in Sect. 2, the mechanical model is presented containing the rigid body with two contact points, and the necessary formulation is derived for the subsequent analysis. In Sect. 3, the nonsmooth behaviour is presented in the state space, and we demonstrate that the direct description of the transitions is not possible due to the indeterminacy of contact forces. In Sect. 4, the concepts of possible and realizable rolling states are presented in the case of a single contact point. This approach is extended to the body with two contact points in Sect. 5, and the conditions of the realizable rolling states are determined. In Sect. 6, the results are demonstrated on a mechanical example with closed form calculations.

2 Mechanical model of a rigid body with two contact points

Consider the motion of a rigid body which is in normal contact with two fixed, rigid surfaces at the points \(P^+\) and \(P^-\), respectively. Assume that the external forces and the geometry of the surfaces ensure that the contact points persist continuously during the motion, and no other contact points appear. It is assumed that the normal contact persists in a regular state and compilations of the Painleve paradox [6] do not occur.

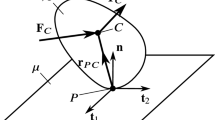

2.1 Geometry

At a certain configuration of the body, let \({\mathbf {n}}^+\), \({\mathbf {n}}^-\) denote the normal unit vectors of the surfaces at \(P^+\) and \(P^-\). Let C denote the centre of gravity of the moving body, and let the locations of the contact points are \({\mathbf {r}}^+=\overrightarrow{CP^+}\) and \({\mathbf {r}}^-=\overrightarrow{CP^-}\) (see Fig. 1).

For the convenient kinematic description of friction effects, we introduce orthonormal bases at the contact points. First, let us consider the vector \({\mathbf {r}}^+-{\mathbf {r}}^-\) pointing from \(P^-\) to \(P^+\), and define the corresponding unit vector

Then, two tangential unit vectors can be defined at each contact point:

We exclude the degenerate cases when the two contact points coincide, or, \({\mathbf {r}}^+-{\mathbf {r}}^-\) is parallel to \({\mathbf {n}}^+\) or \({\mathbf {n}}^-\). Then, (1)–(3) provide the orthonormal bases \(({\mathbf {n}}^+,{\mathbf {t}}_1^+,{\mathbf {t}}_2^+)\) and \(({\mathbf {n}}^-,{\mathbf {t}}_1^-,{\mathbf {t}}_2^-)\).

2.2 Kinematics

At the contact points, the velocities of the moving body are denoted by

respectively. These velocities are not independent, but they are related by the reduction formula of rigid body kinematics,

where \(\varvec{\Omega }\) is the angular velocity vector of the body and \(\times \) denotes cross product.

The scalar product of the right-hand side of (5) by \({\mathbf {a}}\) vanishes. Thus, we can introduce the variable

which is the common velocity component of \(P^+\) and \(P^-\) in the direction of \({\mathbf {a}}\). From (4) and (6), we get \(u_2^+=c^+u_a\) and \(u_2^-=c^-u_a\), where

Then, the velocities (4) become

The cross product of (5) by \({\mathbf {a}}\) gives

Then, by using the notation

for the angular velocity component parallel to \({\mathbf {a}}\), the angular velocity vector can be expressed in the form

Consequently, (8) and (11) show that in a given configuration, the velocity state of the body can be described uniquely by the four variables \(u_1^+,u_1^-,u_a\) and \(\Omega _a\).

The rolling of the body at \(P^+\) is characterized by \({\mathbf {v}}^+={\mathbf {0}}\), which is equivalent to \(u_1^+=u_a=0\). Similarly, the rolling at \(P^-\) is characterized by \({\mathbf {v}}^-={\mathbf {0}}\), which is equivalent to \(u_1^-=u_a=0\).

2.3 Newton–Euler equations

At the contact points \(P^+\) and \(P^-\), the contact forces are denoted by \({\mathbf {F}}^+\) and \({\mathbf {F}}^-\), respectively (see Fig. 2). They are expressed in the form

where \(N^+>0\) and \(N^->0\) are the normal force components, and the tangential forces are given by

All other external loads are reduced into the centre of gravity C of the body, leading to the resultant external force \({\mathbf {F}}_e\) and the resultant external torque \({\mathbf {M}}_e\). Then, the Newton–Euler equations of the rigid body become

where \({\mathbf {J}}\) is the mass moment of inertia of the body,

is the velocity of the centre of gravity of the body, and the dot denotes differentiation with respect to the time.

2.4 Coulomb friction model

To complete our model, we assume the simple Coulomb friction model between the bodies. That is, the point \(P^+\) can be either in slipping state characterized by

or, in rolling state characterized by

Similarly, the slipping and rolling states of \(P^-\) are given by

and

respectively.

To simplify the notations, we implicitly assumed, that the friction coefficient \(\mu \) is the same at the two contact points, which restriction can be released if necessary. We also assume that the static and dynamic friction coefficients are the same, which can be generalized for a class of friction models presented in Sect. 4.1. Note that instead of the presented basic description, the contact laws could be alternatively interpreted as set-valued force laws (see [8] and [28]).

2.5 Kinematic cases

The slipping or rolling states of the two contact points lead to four different kinematic cases of the body. Throughout the paper, these cases are referred to by the following acronyms:

-

Case SS: slipping–slipping case, the body is slipping at both \(P^+\) and \(P^-\),

-

Case SR: slipping–rolling case, the body is slipping at \(P^+\) and rolling at \(P^-\),

-

Case RS: rolling–slipping case, the body is rolling at \(P^+\) and slipping at \(P^-\),

-

Case RR: rolling–rolling case, the body is rolling at both \(P^+\) and \(P^-\).

Note that we assume a permanent normal contact where there is no separation or impacts between the surfaces. When the analysis is extended to the cases with dynamic effects from normal contact, several other kinematic cases appear at two contact points already in problems in two dimensions [15, 18, 27]. With the loss of contact in spatial problems with two contact points, we obtain at least nine kinematic cases [1]. In this paper, we assume that the normal contact is ensured, leading to the four kinematic cases listed above.

3 Nonsmooth dynamics

3.1 State space

The six degrees of freedom of a free rigid body are reduced by two because of the two normal contact constraints. Thus, at least in the vicinity of an initial configuration, the configuration space of contacting body can be parametrized by generalized coordinates in the form

We parametrize the velocity state of the body by the vector

which quantities are called the quasi-velocities (see [9], p. 217) of the system.

The vectors \({\mathbf {r}}^+\), \({\mathbf {r}}^-\), \({\mathbf {n}}^+\) and \({\mathbf {n}}^-\) depend on the generalized coordinates q, and the moment of inertia tensor \({\mathbf {J}}\) depends on q, as well. Moreover, we assume that the external loads \({\mathbf {F}}_e\) and \({\mathbf {M}}_e\) depends only on q and s. In addition, all these dependencies are assumed to be smooth.

Then, dynamics of the moving body is determined in a state space \({\mathcal {X}}\) composed from the generalized coordinates (24) and the quasi-velocities (25),

The dynamics in \({\mathcal {X}}\) is governed by a set of first-order ordinary differential equations. As the velocity state depends linearly on the first derivatives of the generalized coordinates, these derivatives can be expressed in the form

where K(q) is a four-by-four matrix depending smoothly on q. The dynamics of s is written in the form

where the function f(s, q) can be derived from the Newton–Euler equations by selecting the appropriate contact state equations from (16)–(23). Finally, the full dynamics of the state space is formally given by

3.2 The different types of dynamics in the state space

Consider the set

in the state space. This is the subspace where

Similarly, the set

contains the states where

These sets (30) and (31) are codimension-2 subspaces of the state space \({\mathcal {X}}\). Their intersection is the codimension-3 subspace

Purely from kinematic point of view, the location of the different types of dynamics is the following:

-

Case RR (rolling–rolling) is located at \(\Sigma ^\#\).

-

Case RS (rolling–slipping) is located at \(\Sigma ^+\setminus \Sigma ^\#\).

-

Case SR (slipping–rolling) is located at \(\Sigma ^-\setminus \Sigma ^\#\).

-

Case SS (slipping–slipping) is located at \({\mathcal {X}}\setminus (\Sigma ^+\cup \Sigma ^-)\).

The properties of the four kinematic cases can be found in Table 1.

It can be shown that from the Newton–Euler equations (14) and the appropriate conditions from (16)–(23), we can derive the differential equation in the form (29). (Alternatively to the Newton–Euler equations, the kinematic constraints could be directly included to the rolling cases by the Gibbs–Appell equation from [9], p. 254.) Then, we get the vector field F(x) for each kinematic case, which we denote by \(F_\text {SS}(x)\), \(F_\text {SR}(x)\), \(F_\text {RS}(x)\) and \(F_\text {RR}(x)\).

3.3 Indeterminacy of the contact forces

If we want to determine the rolling–slipping transitions between the different cases (see Fig. 3), we have to consider the restrictions (19) and (23) of the friction forces, as well. In each kinematic case, Equations (14) and (16)–(23) form a differential-algebraic equation (DAE), where the unknowns are the contact forces \({\mathbf {F}}^+\), \({\mathbf {F}}^-\), and derivatives \(\dot{s}\) of the quasi-velocities. If we count the independent scalar equations and unknowns (see Table 2), we get that in the cases SS, SR, and RS, all unknowns are determined including the contact forces. However, in Case RR, we do not have enough equations, which causes the central issue of this paper.

The problem is the following: the rolling constraints (18) and (22) are not independent, and thus, we get only 3 kinematic constraints, while 4 unknowns appear when we replace (17) and (21) with (19) and (23). Consequently, the contact forces are undetermined. Without the value of the contact forces, the conditions of the transition between Case RR and the other cases cannot be determined from the inequalities (19) and (23).

It seems that the complete dynamical description of the model is not possible within the framework of the rigid body dynamics and Coulomb friction model. However, by exploiting an internal consistency of the Coulomb model, we can avoid the problem and make the transitions well defined.

For doing that, let us focus on the behaviour of the vector field of the slipping cases in the vicinity of the subspace containing the rolling-rolling case. We will do this in Sect. 5, while the necessary tools are presented step by step in Sect. 4.

Possible transitions between the four kinematic cases. The downward arrows denote slipping of the body at one or both contact points. The upward arrows correspond to the transition from sticking to rolling. At Case RR, the corresponding arrows are dashed, denoting the fact that these transitions cannot be checked by directly using the Coulomb friction law, because the contact forces are undetermined

4 Analysis of realizable rolling states at a single-point contact

4.1 The basic ideas of slipping directions and realizable sticking

Consider the trivial example of a block freely slipping on a vertical line, which can be seen in the left panel of Fig. 4. The notation is the following: m is the mass of the block, u is the velocity of the block, g is the gravitational acceleration, and L is the loading force. We consider the Stribeck extension of the Coulomb model in the form of velocity-dependent friction coefficient \(\mu (|u|)\). In the limiting cases, the monotonically decreasing friction coefficient provides the static friction coefficient \(\mu _\text {s}=\lim _{|u|\rightarrow 0}\mu (|u|)\) and the dynamic friction coefficient \(\mu _\text {d}=\lim _{|u|\rightarrow \infty }\mu (|u|)\) (see the right panel of Fig. 4).

According to the Coulomb model with this extension, the slipping contact state is described by the differential equation

The static (sticking) contact state is given by \(u\equiv 0\) and the ’dynamics’ is given by the static equation

where \(T_\text {s}\) is the static friction force. Consider an initial sticking state and push the block by a force L. Our question is whether the block keeps its slipping state or not. Consider the following two different approaches, which we call the possibility and realizability of the sticking state.

First, we can use the direct condition from the Coulomb friction model which restrict the value of the static friction force:

Definition 1

Under the load L, sticking of the block is possible if the static friction force \(T_\text {s}=L\) satisfies

Second, we can consider the infinitesimal slipping perturbations \(u\rightarrow 0^+\), and \(u\rightarrow 0^-\), which correspond to the right and left directions of slip, respectively. The sticking state is realizable if both of these perturbations are eliminated by the dynamics (33), and thus, sticking is regained. In other words, the acceleration and velocity should not have the same direction:

Definition 2

Under the load L, sticking of the block is realizable if

It can be checked by direct calculation that the conditions (35) and (36) are equivalent, and thus, the possible and realizable sticking coincides in this example. It is important to show that the two conditions are conceptionally rather different: when checking possibility, we used the condition (35), which is an additional piece of empirical information from the Coulomb model, which complements the formula \(T_\text {d}=-\mu m g u/|u|\) of the dynamic friction force \(T_\text {d}\). However, the condition (36) does not contain this additional information, but it is purely based on some qualitative assumptions of the slipping dynamics (33).

The example demonstrates that the Coulomb or the Coulomb–Stribeck models contain some internal consistency: the restriction of the maximal contact forces is given in such way which is consistent with the direction of the surrounding vector field in the state space.

In Sect. 4.2, this property is shown for general rigid body in the planar and spatial cases of the single-point contact, which has been analysed throughout in [4]. Then, in Sect. 5, we can show how the concept of realizability can be applied even in the two-point contact case when the possibility cannot be checked due to the indeterminacy of the contact forces.

4.2 Realizable static states at single point contact

4.2.1 Planar contact case

Sketch of a state space of a Filippov system, related to the dynamics of a rigid body with a single planar contact. The rolling or sticking dynamics is located in the discontinuity set \(\Sigma \), and the slipping dynamics is located outside. The point \({\bar{x}}\) with the red limit vectors represents a attracting sliding point, where both limit vectors point towards \(\Sigma \), and thus, the rolling motion is realizable. The point \({\bar{x}}'\) with the blue vectors corresponds to the crossing case when the rolling motion is not realizable

Now, we generalize the case of the previous example. Consider a rigid body with a single contact point with a rigid surface. In the planar (two-dimensional) case, the slipping velocity at the contact point is described purely by a single component u, and the static (rolling or sticking) case is characterized by \(u=0\). In the presence of Coulomb friction, the dynamics of such body often leads to a Filippov-system, which can be defined in the following way:

Definition 3

(Filippov system) Consider a system

Assume that (37) has the following properties:

-

1.

F is defined in \({\mathbb {R}}^m\setminus \Sigma \) where

$$\begin{aligned} \Sigma =\left\{ x: x_1=0\right\} . \end{aligned}$$(38) -

2.

For all \({{\bar{x}}}\in \Sigma \) the limits

$$\begin{aligned} \begin{aligned} F^*_1({\bar{x}})&=\lim _{\epsilon \rightarrow 0^+}{\bar{x}}+\epsilon n_1, \\ F^*_2({\bar{x}})&=\lim _{\epsilon \rightarrow 0^+}{\bar{x}}+\epsilon n_2 \end{aligned} \end{aligned}$$(39)exist where \(n_1=(1,0,\dots 0)\) and \(n_2=(-1,0,\dots 0)\).

-

3.

For all \({{\bar{x}}}\in \Sigma \), \(F^*_1({\bar{x}})\ne F^*_2({\bar{x}})\).

Then, we call (37) a Filippov system.

In Definition 3,

-

\(\Sigma \) is the codimension-1 discontinuity set (also called switching surface),

-

\(n_1\) and \(n_2\) are the unit normal vectors of \(\Sigma \),

-

\(F^*_1({\bar{x}})\), \(F^*_2({\bar{x}})\) are called limit vectors at a point \({{\bar{x}}}\in \Sigma \) (see Fig. 5).

The normal component of \(F_1^*\) and \(F_2^*\) with respect to \(\Sigma \) express whether the trajectories approach or leave the discontinuity set \(\Sigma \). This distinction leads to the following categorization:

Definition 4

Consider a point \({{\bar{x}}}\) of the discontinuity set \(\Sigma \).

-

The point \({\bar{x}}\) is called an attracting sliding point of \(\Sigma \) if \(\left\langle F^*_1({\bar{x}}),n_1\right\rangle <0\) and \(\left\langle F^*_2({\bar{x}}),n_2\right\rangle <0\).

-

The point \({\bar{x}}\) is called a crossing point of \(\Sigma \) if \(\left\langle F^*_1({\bar{x}}),n_1\right\rangle \cdot \left\langle F^*_2({\bar{x}}),n_2\right\rangle <0\).

-

The point \({\bar{x}}\) is called a repelling sliding point of \(\Sigma \) if \(\left\langle F^*_1({\bar{x}}),n_1\right\rangle >0\) and \(\left\langle F^*_2({\bar{x}}),n_2\right\rangle >0\).

For more details about Filippov systems and about the more general class of piecewise smooth systems, see [5] and [12].

When the motion of the rigid body leads to a Filippov system in the state space, the static contact states are located in the discontinuity set \(\Sigma \) (see Fig. 5). Following our assumptions from the block example presented above, we would like to ensure that all possible perturbations in the slipping velocity are eliminated by the dynamics. That is, the static (rolling or sticking) contact state of the body is realizable when the vector field point towards \(\Sigma \) from both sides:

Definition 5

(Realizable rolling or sticking in 2D) Consider the rigid body with a single planar contact where the slipping velocity is denoted by u, and the static contact state corresponds to \(u=0\). Assume that the motion of the body can be described by a Filippov system (37) where \(x_1=u\). We say that a rolling or sticking state \({{\bar{x}}}\) of the body is realizable if and only if the given state in the state space is an attracting sliding point of \(\Sigma \).

We expect that this realizability of the static contact case is equivalent to the possibility required by the Coulomb model and its generalizations. This coincidence can be proved as a special case of Theorem 4 in [4].

Unfortunately, the term ’sliding region’, which has become usual in the literature, is a bit misleading in mechanical applications: in the state space, there is no slipping in the sliding region, but it is the location of the static (rolling or sticking) behaviour. Thus, we avoid the term ’sliding’ in the mechanical sense and use the term ’slipping’ instead.

4.2.2 Spatial contact case

Now, let us consider the spatial (three-dimensional) variant of the previous scenario, when the slipping velocity at the single contact point has two components \(u_1\) and \(u_2\), and the static state is characterized by \(u_1=u_2=0\). When Coulomb friction is assumed at the contact, the dynamics often leads to an extended Filippov system.

Definition 6

(Extended Filippov system) Consider a system

Assume that (40) has the following properties:

-

1.

F is defined in \({\mathbb {R}}^m\setminus \Sigma \) where

$$\begin{aligned} \Sigma =\left\{ x: x_1=x_2=0\right\} . \end{aligned}$$(41) -

2.

For all \({{\bar{x}}}\in \Sigma \) and \(\phi \in [0,2\pi )\) the limit

$$\begin{aligned} F^*({\bar{x}},\phi )=\lim _{\epsilon \rightarrow 0}{\bar{x}}+\epsilon n(\phi ) \end{aligned}$$(42)exists where \(n(\phi )=(\cos \phi ,\sin \phi ,0,\dots 0)\).

-

3.

For all \({{\bar{x}}}\in \Sigma \), there exist \(\phi _1,\phi _2\in [0,2\pi )\) such that \(F^*({\bar{x}},\phi _1)\ne F^*({\bar{x}},\phi _2)\).

Then, we call (40) an extended Filippov system.

In Definition 3,

-

\(\Sigma \) is a codimension-2 discontinuity set,

-

\(n(\phi )\) maps the interval \(\phi \in [0,2\pi )\) onto the set of unit normal vectors of \(\Sigma \),

-

\(F^*({\bar{x}},\phi )\) is called the limit vector field of (40) at a given point \({{\bar{x}}}\in \Sigma \) (see Fig. 6).

Sketch of a state space of an extended Filippov system, related to the dynamics of a rigid body with a single spatial contact. The rolling or sticking dynamics is located in the discontinuity set \(\Sigma \), and the slipping dynamics is located outside. At a point \({\bar{x}}\in \Sigma \), there are continuously many normal vectors \(n(\phi )\), which generates the limit vector field \(F^*({\bar{x}},\phi )\) containing the possible directional limits of the vector field. The green vector shows the projection of \(F^*\) onto the normal space of \({\bar{x}}\). The polar components of these projection gives the functions \(R(\phi )\) and \(V(\phi )\), which are used to determine whether the rolling motion is realizable

Unlike in the codimension-1 case, a point \({{\bar{x}}} \in \Sigma \) has now continuously many normal directions \(\phi \in [0,\pi )\). We can find certain special limit directions. In the normal space, the limit directions are the asymptotes of the trajectories connected to the discontinuity set. First, let us define the quantities

which are the radial and circumferential component of the limit vector field at \({\bar{x}}\). A limit direction \(\phi _1\) and the corresponding normal vector \(n(\phi _1)\) are an asymptote of at least one trajectory at \({\bar{x}}\in \Sigma \) in the normal plane if the circumferential component V vanishes:

Definition 7

(Limit direction) Assume that the direction \(\phi _1\in [0,2\pi )\) satisfies \(V({\bar{x}},\phi _1)=0\). Then, \(\phi _1\) is called a limit direction of F at \({\bar{x}}\in \Sigma \). This limit direction is called attracting if \(R({\bar{x}},\phi _1)<0\) or repelling if \(R({\bar{x}},\phi _1)>0\).

That is, the attracting and repelling limit directions correspond to the trajectories which reach \({\bar{x}}\) in forward or backward direction of time. By using the concept of limit directions, the sliding and crossing points of \(\Sigma \) can be defined analogously to those of the classical Filippov systems:

Definition 8

Assume that F possesses at least one limit direction at \({\bar{x}}\in \Sigma \).

-

The point \({\bar{x}}\) is called an attracting sliding point of \(\Sigma \) if all the corresponding limit directions are attracting.

-

The point \({\bar{x}}\) is called a crossing point of \(\Sigma \) if there exists at least one attracting and one repelling limit direction.

-

The point \({\bar{x}}\) is called a repelling sliding point of \(\Sigma \) if all the corresponding limit directions are repelling.

In the spatial (3D) case, the realizability of the static (rolling or sticking) contact case requires that no solutions can escape along repelling limit directions:

Definition 9

(Realizable rolling or sticking in 3D) Consider the rigid body with a single spatial contact where the components of the slipping velocity are denoted by \(u_1\) and \(u_2\), and the static contact state corresponds to \(u_1=u_2=0\). Assume that the motion of the body can be described by an extended Filippov system (40) where \(x_1=u_1\) and \(x_2=u_2\). We say that a rolling or sticking state \({{\bar{x}}}\) of the body is realizable if and only if the given state in the state space is an attracting sliding point of \(\Sigma \).

It can be shown that this realizable property of rolling is equivalent to the possibility of rolling prescribed by the Coulomb model. This proof can be found in Theorem 4 of [4], although the term ’realizable’ is still not mentioned there.

5 Analysis of realizable rolling states at two-point contact

In the single-point contact case, we recognized that for the Coulomb and Coulomb–Stribeck models, the condition of possibility of the static contact state does not add further information to that we know from the realizability based on the vector field of the system. Consequently, if we can establish the realizability for the two-point contact state, then we do not need the information from the condition of the maximum values of static friction force. Thus, the problem of the undetermined contact forces can be resolved.

5.1 Nonsmooth dynamics in Case SS

Based on the concepts shown above, let us continue the analysis from the end of Sect. 3.2. In the two-point slipping case (Case SS), the equations (17) and (21) can be written into the form

where

These quantities satisfy \((\lambda _1^+)^2+(\lambda _2^+)^2=1\) and \((\lambda _1^-)^2+(\lambda _2^-)^2=1\), and they formally contain the nonsmooth dependence on the quasi-velocities \(u_1^+,u_1^-,u_a\) of (25). (Note that \(u_2^+=c^+u_a\) and \(u_2^-=c^-u_a\), see (7).)

Let us use the notation \(\lambda =(\lambda _1^+,\lambda _2^+,\lambda _1^-,\lambda _2^-)\). Then, the Newton–Euler equations (14) can be decomposed into algebraic and differential parts in the form

and

where

-

the matrices \(A_N\) and \(A_s\) depend smoothly on s and q, and they depend linearly on \(\lambda \);

-

the vectors \(b_N\) and \(f_\text {smooth}\) depend smoothly on s and q.

Assume that (46) provides strictly positive values for the normal forces \(N^+\) and \(N^-\). Then, the combination of (46) and (47) leads to

where \(f_\text {nonsmooth}=A_sA_N^{-1}b_N\). We can conclude that in general, the components of \(f_\text {nonsmooth}\) are rational functions in \(\lambda \) with a quadratic numerator and denominator.

By adding the (smooth) kinematic part of the vector field from (27), we get the differential equation (29) in the form

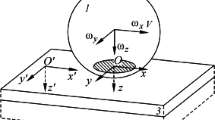

for the two-point slipping case. The sets \(\Sigma ^+\) and \(\Sigma ^-\) from (30)–(31) are exactly the codimension-2 discontinuity sets of (49), where the auxiliary variables (45) and the contact forces (44) are not defined. The discontinuity sets are intersecting each other at \(\Sigma ^\#\) (see (32)), which is the location of the two-point rolling case. The structure of the state space can be seen in Fig. 7.

Structure of the state space of the two-point contact body. The two codimension-2 subspaces \(\Sigma ^+\) and \(\Sigma ^-\) are the discontinuity sets of the two-point slipping dynamics (Case SS), and these are the loci of the mixed rolling slipping cases (SR and RS), respectively. The intersection \(\Sigma ^\#\) of these sets corresponds to the two-point rolling case (Case RR). The possible directions of slipping in Cases RS and SR correspond to unit circles parametrized by \(\phi ^+\) and \(\phi ^-\). The possible directions of two-point slipping in Case RR correspond to a unit sphere, which can be parametrized by \(\phi ^+\) and \(\phi ^-\) (see Fig. 8)

Let us consider the angles

Then, we get

Let us denote the normal vectors of the discontinuity sets by

At a point \({\bar{x}}\in \Sigma ^+\setminus \Sigma ^\#\), we can take the limit

Similarly, at \({\bar{x}}\in \Sigma ^-\setminus \Sigma ^\#\), we can take the limit

From the structure of the equations (48)–(49), we can check that the limit (53)–(54) satisfy the conditions of Definition 6. That is, (49) can be considered an extended Filippov system with two intersecting discontinuity sets.

By calculating the limit directions of the vector field from (53) and (54), we could determine the realizability of the mixed rolling–slipping cases (RS and SR), and thus, the conditions of their transition to the two-point slipping case (see the continuous arrows in Fig. 3). However, we do not focus on these transitions, but instead, we try to determine the realizability of the two-point rolling (RR) case.

5.2 Transition from Case RR to Case SS

The two-point rolling case (RR) is located at the intersection of \(\Sigma ^+\) and \(\Sigma ^-\), where a codimension-3 discontinuity set \(\Sigma ^\#\) appears in the phase space (see Fig. 7). The possible directions normal to \(\Sigma ^\#\) can be visualized by a 2-sphere.

Parametrization of the unit sphere of normal directions by using the angles \(\phi ^+\) and \(\phi ^-\). Left panel: the parameter lines depicted on the unit sphere. Right panel: the parameter ranges. The “northern” and “southern” hemispheres of the left panel correspond to the two squares of the parameter plane on the right panel. The “equator” of the sphere corresponds to the parameter values \(\sin \phi ^+=\sin \phi ^-=0\), where the parametrization is singular

We would like to parametrize this sphere by using the angles \(\phi ^+\) and \(\phi ^-\). Thus, consider the normal vector \(n(\phi ^+,\phi ^-)\) in the form

where the parameter range of the angles is

The graph of (56) is an unit sphere spanned by the components \(u_1^+,u_1^-\) and \(u_2\) (see Fig. 8). The vector (55) is a unit vector satisfying

and it satisfies the normality conditions

The formulae 58 express that the projections of the normal vector \(n(\phi ^+,\phi ^-)\) onto the normal spaces of \(\Sigma ^+\) and \(\Sigma ^-\) are perpendicular to \(n^+(\phi +)\) and \(n^-(\phi ^-)\), respectively (see Fig. 7).

The parametrization (55) is singular at \(\sin \phi ^+=\sin \phi ^-=0\). For the nonsingular parameter region \((\phi _1,\phi _2)\in \Phi \) (see (56)), we can define the limit

Then, the radial and circumferential components of the vector field can be defined analogously to (43):

The singularity of the parametrization at \(\sin \phi ^+=\sin \phi ^-\) behaves the following way:

-

Consider the four parameter combinations given by \((\cos \phi ^+,\cos \phi ^-)=(\pm 1,\pm 1)\). Each of them is a single point in the parameter plane (excluding periodicity, see the number 1-4 in the right panel of Fig. 8). In the same time, each of this combination covers a quarter arc on the unit sphere of normal directions (see the left panel of Fig. 8), which corresponds to continuously many slipping directions with the same tangential forces.

-

Consider the parameter combinations \(\cos \phi ^+=\pm 1\), \(\cos \phi ^-\ne \pm 1\) or \(\cos \phi ^-=\pm 1\), \(\cos \phi ^+\ne \pm 1\). These values cover the edges of the square regions in the parameter plane. In the same time, they correspond to the discrete points where the unit sphere intersects the codimension-2 discontinuity sets of Cases SR and RS. Thus, these states should be excluded from the analysis, because they correspond to the single-point slipping.

Thus, we denote the singular parameter set by

and the corresponding normal vectors by

By the formula (62), the normal vectors correspond to the middle points of the four quarter arcs of the “equator” of the unit sphere (see Fig. 8). Then, the domain of the limit (59) can be extended to \(\Phi \cup {\tilde{\Phi }}\). The functions (60) can be applied to \({\tilde{\Phi }}\), as well, but \(V^+\) and \(V^-\) coincide in this case because \(n^+\) is then parallel to \(n^-\). Thus, we require a further vector for the following definition:

Now, we have all the formulation to define the limit directions of the transitions between Cases RR and SS.

Definition 10

(Limit directions at the intersection) Consider a point \({{\bar{x}}}\) in the intersection \(\Sigma ^\#\) of the discontinuity sets \(\Sigma ^+\) and \(\Sigma ^-\). Assume that the pair \((\phi ^+_1,\phi ^-_1)\in \Phi \cup {\tilde{\Phi }}\) satisfies \(V^+({\bar{x}},\phi ^+,\phi ^-)=V^-({\bar{x}},\phi ^+,\phi ^-)=0\), and it also satisfies \({\tilde{V}}({\bar{x}},\phi ^+,\phi ^-)=0\) if \((\phi ^+_1,\phi ^-_1)\in {\tilde{\Phi }}\). Then, \((\phi ^+_1,\phi ^-_1)\) is called a limit direction of \(F_\text {SS}\) at \({\bar{x}}\in \Sigma ^\#\). This limit direction is called attracting if \(R({\bar{x}},\phi _1^+,\phi _1^-)<0\) or repelling if \(R({\bar{x}},\phi _1^+,\phi _1^-)>0\).

If a point \({\bar{x}}\) possesses a repelling limit direction, then the two-point rolling state is not realizable because trajectories can escape from Case RR into Case SS through this direction. That is, all limit directions at \({\bar{x}}\in \Sigma ^\#\) must be attracting to avoid the two-point slipping, which condition is analogous to that of an attracting sliding point in Definition8. However, we should also check the possibility of transitions when the body starts slipping at only one of the contact points.

5.3 Transition from Case RR into Cases RS and SR

In the rolling–slipping case (Case RS), the rolling constraint (18) leads to \(u_1^+=u_2=0\). Then, the tangential forces at \(P^-\) are given by

In a similar way we did in (46)–(47), a system of algebraic equations can be solved for \(N^+,N^-,T_1^+\) and \(T_2^+\), and then, we can express the time derivatives of the nonconstrained quasi-velocities \({\dot{u}}_1^-\) and \({\dot{\Omega }}_a\). It can be shown that the resulting differential equation

is a Filippov system, where \(\Sigma ^\#\) is embedded into \(\Sigma ^+\) as a codimension-1 discontinuity set given by \(u_1^-=0\).

The slipping–rolling case (Case SR) leads to a similar scenario: Then, the contact forces at \(P^+\) are given by

and the resulting differential equation

is a Filippov system where \(\Sigma ^\#\) is a codimension-1 discontinuity set at \(u_1^+=0\).

At a point \({\bar{x}}\in \Sigma \), a transition from Case RR into Cases RS or SR can occur along a trajectory of \(F_\text {RS}(x)\) or \(F_\text {SR}(x)\) pointing away from the discontinuity set \(\Sigma ^\#\). Thus, to avoid single-point slipping at \(P^+\) or \(P^-\), the state \({\bar{x}}\in \Sigma ^\#\) must be an attracting sliding point of \(F_\text {RS}(x)\) or \(F_\text {SR}(x)\), respectively.

5.4 Realizability of the two-point rolling case

Now we can formulate the main consequence of the analysis. In the state space, the dynamics of Case RR (located in \(\Sigma ^\#\)) is surrounded by domains of the slipping cases (Cases SS, RS and SR). When any slipping transition occurs between Case RR and a slipping case, at least a trajectory of the slipping vector fields \(F_\text {SS}(x)\), \(F_\text {RS}(x)\) or \(F_\text {SR}(x)\) at \(\Sigma ^\#\) needs to leave \(\Sigma ^\#\) at the given point. Thus, the two-point rolling case is realizable when all slipping trajectories point towards the discontinuity set \(\Sigma ^\#\). Then, the effect of small perturbations is eliminated by the slipping vector fields from all directions, and the two-point rolling state is recovered. Based on our results presented in the paper, our final consequence can be formulated:

Definition 11

(Realizable two-point rolling) Let us consider the rigid body with two spatial contacts described in Sects. 2 and 3. We say that a rolling or sticking state \({{\bar{x}}}\in \Sigma ^\#\) of the body is realizable if and only if

-

at \({\bar{x}}\), all limit directions of \(F_\text {SS}(x)\) are attracting,

-

\({\bar{x}}\) is an attracting sliding point of \(\Sigma ^\#\) with respect to \(F_\text {RS}(x)\),

-

and \({\bar{x}}\) is an attracting sliding point of \(\Sigma ^\#\) with respect to \(F_\text {SR}(x)\).

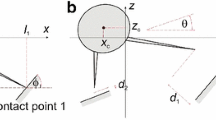

6 Application example—ball in a trough

The practical testing of the realizability conditions of Definition 11 often requires numerical techniques, because (60) leads to nonlinear equations in the sine and cosine of the angles \(\phi ^+\) and \(\phi ^-\). In this last section, we demonstrate the method on a simple example where the conditions can be calculated analytically.

Consider a homogeneous ball moving in a horizontal V-shaped trough (see Fig. 9). A general constant loading torque vector \({\mathbf {M}}_e\) is acting on the ball. Our goal is to calculate the conditions when the two-point rolling of the ball is realizable. We assume a friction coefficient \(\mu =\mu _\text {s}=\mu _\text {d}\) at both contact points.

Sketch of the example analysed in Sect. (6): a ball rolling in a horizontal right angle trough. By using the method developed in the paper, we can determine the conditions for the constant loading torque when the two-point rolling is realizable. Due to the undetermined contact forces, this process cannot be done by the usual techniques of rigid body mechanics

In this example, the location of the contact points and the normal vectors are independent of the configuration, and they are given by

where r is the radius of the ball and \({\mathbf {i}}\), \({\mathbf {j}}\), \({\mathbf {k}}\) are the basis vectors fixed to the trough (see Fig. 9). Then, (1)–(3) become

From (7), we get \(c^+=c^-=1/\sqrt{2}\). Thus, we can use the notation \(u_2=u_2^+=u_2^-=u_a/\sqrt{2}\), and the velocities of the contact points become

For the homogeneous ball, the centre of the gravity C is the geometric centre. Let v denote the velocity of C along the trough, and the velocity vector is

From (70) and (71), the angular velocity of the ball can be expressed,

In this simple case, we replace (25) by a new set

of quasi-velocities, which choice simplifies the form of the equations. The transformation

between (25) and (73) is just a rescaling of some components, which does not modify the general description presented above.

The external force system consists of the resultant force \({\mathbf {F}}_e=-mg/\sqrt{2}({\mathbf {i}}+{\mathbf {j}})\) from the gravity g and the resultant torque \(\mathbf {M_e}=M_{ex}{\mathbf {i}}+M_{ey}{\mathbf {j}}+M_{ez}{\mathbf {k}}\). From the Newton–Euler equations (14), we get

and

where m is the mass of the ball, an \(jmr^2\) is the mass moment of inertia, where \(j=2/5\) for a homogeneous sphere.

The right-hand sides of (28) and the algebraic equations (29) are fully determined by the variables \(u_1^+\), \(u_1^-\) and \(u_2\), and they do not depend on either v or an arbitrary set of q describing the configuration of the ball. (Note that the system is symmetric with respect to the rotation of the ball around its centre and to the translation of the ball along the trough.) Consequently, the nonsmooth dynamics can be reduced to the space of quasi-velocities,

The discontinuity sets are given by the variables \((0,u_1^-,0,v)\in \Sigma ^+\), \((u_1^+,0,0,v)\in \Sigma ^-\), and \((0,0,0,v)\in \Sigma ^\#=\Sigma ^+\cap \Sigma ^-\). According to (75)–(76), the two-point rolling in \(\Sigma ^\#\) is given by

and the components \(N^+\), \(N^-\), \(T_2^+\) and \(T_2^-\) of the contact forces are undefined.

At a point \({\bar{x}}=(0,0,0,{\hat{v}})\in \Sigma ^\#\), we want to determine the conditions, where the two-point rolling motion of the realizable two-point motion. As the variable v does not directly affect the dynamics, the same result is expected independently from the choice of \({\bar{x}}\). Thus, instead of varying the state \({\bar{x}}\), we investigate the dependence on the external torque components \(M_{ex}\), \(M_{ey}\) and \(M_{ez}\) as parameters.

For the simplicity of the formulae, we consider the dimensionless form

of the torque components, and the realizable rolling states are explored in the parameter space \((m_x,m_y,m_z)\).

6.1 Transition from Case RR to Cases RS and SR

In Case RS, the vector field \(F_\text {RS}\) can be derived from (75)–(47) by considering the rolling constraint \(u_1^+=u_2=0\) and the slipping friction force (64). Then, from the normal vectors \(n_1=(0,0,1,0)\) and \(n_2=(0,0,-1,0)\) the limits (39) of the vector field become

From Definitions (11) and 4, a realizable rolling states needs to satisfy \(\left\langle F^*_{\text {SR1}},n_1\right\rangle <0\) and \(\left\langle F^*_{\text {SR2}},n_2\right\rangle <0\). By using direct calculation from (80)–(81), the boundary cases \(\left\langle F^*_{\text {SR1}},n_1\right\rangle =0\) and \(\left\langle F^*_{\text {SR2}},n_2\right\rangle =0\) leads to

respectively.

Due to the symmetry of the mechanical system, a very similar calculation can be applied to Case SR, and in the boundary case, we get the equations

In the parameter space \((m_x,m_y,m_z)\) of the dimensionless components of the external torque, (35)–(36) describe four planes, which encompass a tetrahedron (see Fig. 10). Inside this tetrahedron, there is no one-point slip transition to Cases RS and SR. However, we have to check the two-point slip transition, as well.

Surfaces at the boundary case of slipping in the parameter space of the dimensionless torques \(m_1,m_2\), and \(m_3\). The blue edged tetrahedron visualizes the planes (82)–(83), which are related to the one-point slipping. The curved surfaces are given by (88), which is related to the two-point slipping. The body inside of these surfaces gives the region where the two-point rolling is realizable (see Fig. 11)

6.2 Transition from Case RR to Case SS

As we changed \(u_a\) into \(u_2\) in the transformation (74), we can redefine the angles (50) by

Then, (51) simplifies to \(\lambda _1^+=\cos \phi ^+\), \(\lambda _2^+=\sin \phi ^+\), \(\lambda _1^-=\cos \phi ^-\) and \(\lambda _2^-=\sin \phi ^-\). Then, by using (75)–(76) with the friction forces from (44), the limit vector field (59) can be written into the form

where the normal forces are given by

The limit vector field (85) can be used to calculate the conditions of the transition from Case RR to Case SS.

Slipping initiates simultaneously at both contact points, when an attracting limit direction appears at \(\Sigma ^\#\) according to Definition 10. In boundary case between and attracting and repelling limit direction,

needs to be satisfied. From the three equations (87), the dimensionless moments \(m_x\), \(m_y\) and \(m_z\) can be expressed as a function of the angles \(\phi ^+\) and \(\phi ^-\) characterizing the direction of the slip transition:

The expressions (88) form a parametric representation of a surface in the parameter space \((m_x,m_y,m_z)\). This surface can be seen in Fig. 10, where the upper and lower branches of the curved surface are related to the two regions of the domain of directions in (56) and in Fig. 8.

6.3 Realizable two-point rolling

In the parameter space, the realizable region of two-point rolling is determined by the interplay between the surfaces of one-point and two-point slipping transitions (see (82)–(83) and (88), respectively). Then, we got a three-dimensional region in the parameter space of the dimensionless torques \(m_x,m_y\) and \(,m_z\) (see Fig. 11). The resulting “body” in the parameter space has four planar faces (denoted by solid grey), where the two-point rolling (Case RR) motion turns into one-point slipping (Cases RS and SR); and two curved faces (denoted by the coloured parameter lines) where two-point slipping (Case SS) appears.

The region in the parameter space of the dimensionless torques \(m_1,m_2\), and \(m_3\), where the two-point rolling motion is realizable. This three-dimensional region is determined by the surfaces in Fig. 10. The grey planar surfaces correspond to one-point slipping, and the coloured curved surfaces correspond to two-point slipping. The special points (90) are denoted by small circles, squares and triangles. The edge highlighted by red shows the parameter values where the maximum acceleration of the ball can be achieved in (78) with a realizable two-point rolling

When we analyse the effect of the torque component \(M_{ez}\), let us consider the special values

It can be shown from (82)–(83) and (88) that the corresponding dimensionless values

are related to the special points in Fig. 11 denoted by circles, squares and triangles, respectively. The value of the torque component \(M_{ez}\) separates the following cases:

-

For \(|M_{ez}|\le M_{ez1}\), Case SS can turn into Cases SR or RS for large values of \(|M_{ex}|\) and \(|M_{ey}|\) (only single-point slipping).

-

For \(M_{ez1}\le |M_{ez}|\le M_{ez2}\), Case SS can turn into Cases SR, RS or SS for large values of \(|M_{ex}|\) and \(|M_{ey}|\) (single- or two-point slipping).

-

For \(M_{ez2}\le |M_{ez}|\le M_{ez3}\), Case SS can turn into Case SS for large values of \(|M_{ex}|\) and \(|M_{ey}|\) (only two-point slipping).

-

For \(M_{ez3}\le |M_{ez}|\), the two-point rolling is not realizable.

By analysing the region of the realizable rolling states, we can obtain a following interesting result: the maximal magnitude of acceleration \({\dot{v}}\) of the centre of the ball can be determined (see (78)). By direct calculation, it can be shown that this maximal acceleration with realizable two-point rolling is given by

and this acceleration is achieved by the torque vectors corresponding to the red coloured edge in Fig. 11.

7 Conclusion

In this paper, we analysed the motion of a rigid body that is in contact with two rigid surfaces in the presence of dry friction. When the normal contacts are maintained at both contact points, the slipping or rolling at each contact point results in four kinematic cases. It was shown that in the presence of Coulomb model or similar dry friction models, the state space of the two-point slipping system contains two codimension-2 discontinuity sets. These subspaces correspond to the two mixed rolling-slipping cases, and they intersect each other in the codimension-3 discontinuity set of the two-point rolling case. The nonsmooth dynamics of the body contains transitions between these cases in the corresponding subspaces. It can be shown that the kinematic constraints of rolling at the two contact points are not fully independent, which makes the contact forces undetermined in the two-point rolling case. Thus, the transitions from two-point rolling to the slipping cases cannot be determined directly from the limits of the static friction forces prescribed by the Coulomb model.

We showed that the indeterminacy can be resolved by the qualitative analysis of the vector field at the discontinuity, which procedure is based on the consistency of the dry friction models. The analytical tools of nonsmooth systems were utilized to find the possible directions where trajectories are connected to the intersection of the two codimension-2 discontinuity sets, and thus, the possible rolling–slipping transitions can be explored without knowing the undetermined contact forces. Finally, we presented the dynamic conditions which ensure that the two-point rolling is realizable without slipping. Then, the method was demonstrated with analytical calculations for a ball rolling in a trough. It was proven that its maximal realizable acceleration without slipping is \(\sqrt{2}\mu g\).

The method can be applied to mechanical engineering problems containing two-point contact parts like railway wheelsets [11, 19], where the qualitative behaviour of the dynamics could be explored in the parameter space. Another application of the method is to create analytical solutions of reference examples to test the capabilities of numerical methods of multi-body software packages in cases of multiple contact points with dry friction.

A possible generalization of the analysis would be to consider more advanced friction models, including dynamical effects or pre-sliding displacement (see [16, 21] for an overview), or the assumption of finite contact region creating spinning torques (see e.g. [14]).

It would be interesting to include frictional contacts applied though kinematic joints. For the analysis of theses system, the assumptions about of the friction should be reconsidered according to the energetic issues of the normal contact models [22, 25].

Furthermore, it would be useful to check whether the formulation presented in the paper could help to improve numerical integration of mechanical systems with two or more contact points. The existence of limit directions provide some preliminary qualitative information about the solutions, which can be possibly exploited at numerical simulation.

Data Availability Statement

The manuscript has no associated data.

References

Antali, M., Stepan, G.: Discontinuity-induced bifurcations of a dual-point contact ball. Nonlinear Dyn. 83(1), 685–702 (2016)

Antali, M., Stepan, G.: On the nonlinear kinematic oscillations of railway wheelsets. J. Comput. Nonlinear Dyn. 11(5), 1–10 (2016)

Antali, M., Stepan, G.: Sliding and crossing dynamics in extended Filippov systems. SIAM J. Appl. Dyn. Syst. 17(1), 823–858 (2018)

Antali, M., Stepan, G.: Nonsmooth analysis of three-dimensional slipping and rolling in the presence of dry friction. Nonlinear Dyn. 97(3), 1799–1817 (2019)

di Bernardo, M., Budd, C.J., Champneys, A.R., Kowalczyk, P.: Piecewise-smooth Dynamical Systems. Springer, London (2008)

Champneys, A.R., Varkonyi, P.R.: The painlevé paradox in contact mechanics. IMA J. Appl. Math. 81(3), 538–588 (2016)

Eldridge, G., Eldridge, R.: Cyclonic flow meters. US Patent, US 5 905 200 (1999)

Glocker, C.: Set-Valued Force Laws. Springer, Berlin (2001)

Greenwood, D.T.: Advanced Dynamics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2003)

Hamrock, B.J.: Ball motion and sliding friction in an arched outer race ball bearing. J. Tribol. 97(2), 202–2010 (1975)

Iwnicki, S.: Simulation of wheel-rail contact forces. Fatigue & Fracture of Engineering Materials and Structures 26, 887–900 (2003)

Jeffrey, M.R.: Hidden Dynamics. Springer Nature, Switzerland (2018)

Johnson, K.L.: Contact Mechanics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1985)

Leine, R.I., Glocker, C.: A set-valued force law for spatial Coulomb-Contensou friction. Eur. J. Mech. A 22(2), 193–216 (2003)

Li, G., Wu, S., Wang, H., Ding, W.: Global dynamics of a non-smooth system with elastic and rigid impacts and dry friction. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. 95, 105603 (2021)

Marques, F., Flores, P., Claro, J.C.P., Lankarani, H.M.: A survey and comparison of several friction force models for dynamic analysis of multibody mechanical systems. Nonlinear Dyn. 86(3), 1407–1443 (2016)

Marques, F., Flores, P., Claro, J.C.P., Lankarani, H.M.: Modeling and analysis of friction including rolling effects in multibody dynamics: a review. Nonlinear Dyn. 45, 223–244 (2019)

McNamara, S., Garcia-Rojo, R., Herrmann, H.: Indeterminacy and the onset of motion in a simple granular packing. Phys. Rev. E 72, 021304 (2005)

Meijaard, J.: The motion of a railway wheelset on a track or on a roller rig. Proc. IUTAM 19, 274–281 (2016)

Noel, D., Ritou, M., Furet, B., Noch, S.L.: Complete analytical expression of the stiffness matrix of angular contact ball bearings. J. Tribol. (2013). https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4024109

Pennestri, E., Rossi, V., Salvini, P., Valentini, P.: Review and comparison of dry friction models. Nonlinear Dyn. 83, 1785–1801 (2016)

Pereira, M.S., Nikravesh, P.: Impact dynamics of multibody systems with frictional contact using joint coordinates and canonical equations of motion. Nonlinear Dyn. 9(1), 53–71 (1996)

Peters, M.L.J.P.: Orbital ball flowmeter for gas and fluis. US Patent, US 8 505 378 B2 (2013)

Schorr, P., Li, E.R.C., Kaufhold, T., Hernández, J.A.R., Zentner, L., Zimmermann, K., Böhm, V.: Kinematic analysis of a rolling tensegrity structure with spatially curved members. Meccanica 56, 953–961 (2021)

Stronge, W.J.: Generalized momentum applied to multibody impact with friction. Mech. Struct. Mach. 29(2), 239–260 (2001)

Vaganian, A.: On generalized Coulomb-Amontons’ law in the context of rigid body dynamics. Nonlinear Dyn. 101(4), 2145–2155 (2020)

Varkonyi, P.L., Or, Y.: Lyapunov stability of a rigid body with two frictional contacts. Nonlinear Dyn. 88(1), 363–393 (2017)

Walker, S.V., Leine, R.I.: Set-valued anisotropic dry friction laws: formulation, experimental verification and instability phenomenon. Nonlinear Dyn. 96(2), 885–920 (2019)

Zhao, J.S., et al.: Effects of gyroscopic moment on the damage of a tapered roller bearing. Mech. Mach. Theory 69, 185–199 (2013)

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results has been supported by the Eotvos Lorand Research Network in the Premium Postdoctoral Fellowship Programme under the grant number PPD2018-014/2018.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Budapest University of Technology and Economics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Antali, M., Stepan, G. Slipping–rolling transitions of a body with two contact points. Nonlinear Dyn 107, 1511–1528 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-021-06538-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-021-06538-5