Abstract

In dissipative dynamical systems, equilibrium (stationary) points have a dominant organizing effect on transient motion in phase space, especially in nonlinear systems. These time-independent solutions are readily defined in the context of ordinary differential equations, that is, they occur when all the time derivatives are simultaneously zero. However, there has been some recent interest in perpetual points: points at which the higher time derivatives are zero, but not necessarily the first. Previous work has focused on analytic work (including simulation) and some experimental studies of electric circuits. This paper focuses attention on the occurrence of these points in a simple mechanical system, including experimental verification. Thus, points of zero acceleration can be found in which the corresponding velocity is a maximum or minimum, but not zero. Specifically, the rigid-arm pendulum is used to generate data for which acceleration (and its derivative) can be evaluated. In this paper an experimental (mechanical) setup is described, specifically designed to investigate perpetual points, including a description of the data analysis approaches developed to identify their location.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Perpetual point (PP) is a new type of critical point in dynamical systems proposed in 2015 by Prasad [1]. It is defined as a point for which all accelerations of the system become zero, while at least one of the velocities remains nonzero. Although the role of such points is still not fully understood, many interesting features of PPs were revealed [1,2,3]. Thus, PPs may become a useful tool for analysis of nonlinear systems and help to better understand some complex dynamical phenomena.

An intriguing topic is the possible connection between PPs and hidden or rare attractors. An attractor is called rare if it has relatively small basin of attraction volume, while the basin of the hidden attractor does not intersect with the neighborhood of any fixed point [4]. Recently, many new examples of hidden attractors have been discovered [5,6,7,8,9] and this topic is gaining increasing interest. One of the challenging problems is to detect and localize rare and hidden attractors in multi-stable systems. Some sample-based methods were proposed [10, 11], but they do not reveal any information on the topology of the phase space nor indicate the mechanisms of creation of hidden or rare attractors. The lack of unstable fixed points in the neighborhood of hidden attractors led to the hypothesis that PPs could serve as a tool to locate hidden attractors [3, 4]. This concept has been widely investigated recently, and despite some limitations [12], PPs prove to be a useful tool to localize hidden and rare attractors in multiple types of systems [3, 13,14,15]. Especially in electrical systems there is a need to search for efficient tool to localize non-trivial solutions. In [16, 17] the authors present experimental studies of multi-stable electrical circuits with hidden attractors and consider PPs as a possible tool to localize them in the phase space.

Initially, Prasad [1] suggested that PPs exists only in dissipative systems (in the sense of Levinson [18]), but this hypothesis is not universal as proved by Jafari et al. [19]. Apart from the above, there are papers showing that PPs can help to better understand complex transient dynamics [1], categorize chaotic flows [20] and characterize the attractor ruin phenomenon [21]. It is likely that more possible applications will be shortly discovered, especially given the current interest in PPs.

However, most of the authors refer to simple archetypal non-dimensional models to present some general features of PPs or depict their possible applications. This is mainly because PPs are a new concept, but also because in more complex dynamical models PPs may be extremely difficult to derive analytically as large sets of nonlinear equations needs to be solved for that purpose. Also, there is a lack of experimental investigations on the existence and characteristic of PPs in real-world systems and, up to this point, no one has considered the possibility of reaching PPs in mechanical systems, despite the theoretical examples based on the types of system often used in mechanical modeling (e.g., Duffing’s equation and the simple pendulum). In this paper we investigate PPs in the context of experimental mechanical systems to assess their feasibility. We develop a simple experimental rig specifically designed to access PPs using only experimental data. Based on the obtained results we assess the applicability of this new mathematical concept in the field of experimental mechanics.

The paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2 we investigate the possibility of reaching PPs in simple mechanical systems. Section 3 includes the description of the model and parameter identification. Then, we validate the model and examine the accuracy of numerical simulations. In Sect. 4 we present analytical, numerical and experimental investigations to localize PPs. Finally, in Sect. 5 the conclusions are given.

2 Perpetual points in mechanical systems

Mechanical systems have some specific features that are significant when considering PPs. One of them is the fact that they are always described by a set of second-order ordinary differential equations (ODEs)—one for each degree of freedom (DoF) of a given system: the configuration space. Hence, after the transformation to the set of first-order ODEs we get two equations per each DoF: the phase space. Let us assume that we have the system with n DoF each described by the generalized coordinate \(x_{i}\) where \(i=1,\,2,\ldots ,n\). Such system is described by the set of second-order ODEs:

After the transformation to the set of first-order ODEs, we get:

Therefore, the state of the system is given by 2n coordinates \(x_{i},v_{i}\) (\(i=1,\,2,\ldots ,n\)). Physically, \(x_{i}\) defines the displacement and \(v_{i}\) the velocity related to ith degree of freedom. Hence, the definition of PPs for n DoF mechanical system is the following:

which, including \(\dot{x}_{i}={v}_{i}\), can be rewritten as:

In mechanical systems \(\ddot{x}_{i}\) is the acceleration and \(\dddot{x}_{i}\) is sometimes referred to as jerk, both related to the ith degree of freedom. This means that at the PP all accelerations and jerks have to be equal to zero, while at least one of the velocities should be different than zero (if the velocity were zero, we would have an equilibrium point). The question is, whether such points exist in mechanical systems and, ultimately, whether they can be observed experimentally.

We start our analysis with a simple, single DoF system without external excitation. This is primarily for the sake of simplicity and because the derivation of PPs becomes much more difficult (or even impossible) with the growth of system dimension: the curse of dimensionality familiarly encountered in nonlinear dynamics. We consider the physical (rigid-arm) pendulum which is the most common paradigmatic example in nonlinear dynamics. PPs typically exist only in dissipative systems, so in our example we assume the most simple viscous damping model of dissipation. The equation of motion for the physical pendulum with viscous damping is the following second-order ODE:

where I stands for the pendulum moment of inertia, m is the mass of the pendulum, l is the distance from the pendulum pin joint to its center of gravity, and b is the viscous damping coefficient. After simple calculations we reach the exact formula for PPs given as:

We see that regardless of parameters values the PPs always occur at \(\varphi =\pm (n+1/2)\pi \). Still, the parameters values affect the angular velocity at PPs, and in turn, the velocity at PPs determines their feasibility. To assess whether PPs can be reached experimentally we pick some representative pendula of different scales form different experimental investigations [11, 22,23,24,25,26,27]. We obtain the sets of parameter values that describe the pendula from the recalled experimental rigs and calculate the corresponding angular velocities at PPs. For some cases, we have to recalculate parameter values so that they refer to Eq. 5. Results are presented in Table 1.

The examples shown in Table 1 reflect different sizes and shapes of pendula. For the pendulum with small mass, moment of inertia and damping coefficient (# 1,3) we see that the angular velocities at PPs are extremely high (\(>\,17,500\,\mathrm{rpm}\)) and, of course, cannot be reached in an experiment. By increasing the viscous damping coefficient (# 2) we are able to decrease the angular velocity at PP to \(2762\,\mathrm{rpm}\), but it also would be infeasible to achieve in the considered case [22]. When we increase the mass, moment of inertia and damping coefficient (# 5,7) we reduce the velocity at PPs to around \(3000\,\mathrm{rpm}\). Still, at the recalled experimental rigs, such speeds would cause extreme centrifugal forces that could destroy them. By tuning the parameter values we are able to decrease the angular velocities at PPs to \(647\,\mathrm{rpm}\) (# 4) which still is too much for the considered experimental setup [24]. To sum up, analyzing the data presented in Table 1 we claim that for the considered experimental realizations of a physical pendulum it is not possible to reach PPs experimentally due to the large angular velocities.

The above analysis proves that even for the simple paradigmatic example of a nonlinear mechanical system we may not be able to get to PPs in an experiment. We do not consider more complex systems, but the problem is that with the growth of complexity the formulas describing PPs become much more difficult to obtain. Therefore, one can conclude that for the most of commonly analyzed mechanical systems it is barely possible to reach PPs. Nevertheless, in this paper we show that it is possible to design a simple experimental setup to facilitate the observation of PPs and analyze them experimentally.

3 Model of the system

In the paper we experimentally investigate the dynamics of a tilted physical pendulum with the specific shape as presented in Fig. 1a. Taking into account the conclusions from the previous section we design our system to make PPs feasible. For that purpose, we add a plastic strip that increases the drag and tilt the axis of rotation. Pendulum is mounted directly to a very low friction rotary motion sensor (PASCO CI-6538) which enables precise measurement of the pendulum position and serves as a pin joint.

In Fig. 1b we show the schematic model of the pendulum rod with its parameters. The pendulum has mass m and moment of inertia I, and the center of gravity is located at the distance l from its pin joint. The position of the system is described by the angular displacement of the pendulum \(\varphi \). The axis of rotation is tilted from vertical line by the angle \(\alpha \) (see Fig. 1c).

Usually, when modeling the energy dissipation in mechanical systems as a first try we use viscous linear damping model. In our case this model was not able to reproduce the experimental data, especially at high rotational speeds which was our main goal. This was thought to be mainly due to the existence of the plastic strip that causes significant drag: drag is typically modeled as a force proportional to the square of velocity, but incorporating drag still proved to be insufficient. Then, we came up with the nonlinear model of the energy dissipation with cubic velocity dependence. After a parameter identification process this model gave us satisfactory convergence between the results of numerical simulations and experimental data. The energy dissipation model is given by the following formula that describes the torque generated in the pin joint:

The motion of the system shown in Fig. 1 is governed by the following second-order ODE:

The values of the appropriate physical parameters are given in Table 2.

Introducing dimensionless time \(\tau =t\omega \), where \(\omega =1\,\mathrm{rad/s}\) we obtain dimensionless equation of motion:

where primes denotes the differentiation with respect to non-dimensional time \(\tau \) : \(\varphi '=\varphi \), \(\dot{\varphi }'=\dot{\varphi }/\omega \), \(\ddot{\varphi }'=\ddot{\varphi }/\omega ^{2}\). In Eq. 9 dimensional parameters are replaced by the following non-dimensional parameters: \(A=mgl/I\), \(B=b/I\) and \(C=c/I\) that have the following values \(A=158.82\), \(B=0.1384\), \(C=0.000095\). Thanks to the fact that \(\omega =1\,\mathrm{rad/s}\) after the transformation to dimensionless form we do not change values of generalized coordinates: \(\varphi '=\varphi \), \(\dot{\varphi }'=\dot{\varphi }\), \(\ddot{\varphi }'=\ddot{\varphi }\). Hence, for the sake of simplicity tildes in dimensionless Eq. 9 will henceforth be omitted.

3.1 Identification of system parameters and validation of the model

After derivation of the model we performed a detailed identification of its parameters values. The mass of the pendulum m is the only parameter measured directly. To measure the angles of inclination \(\alpha \) we take two photographs in perpendicular planes on which we have the considered system and upright hanging thread. Based on the 3D model created in CAD software we obtain the pendulum moment of inertia \(I=5.2502\times 10^{-5}\,{\mathrm {kg\,m^{2}}}\) and the distance between its axis of rotation and the center of gravity \(l=5.008\times 10^{-2}\,{\mathrm {m}}\). Finally, we estimate the coefficients describing energy dissipation function (b, c) using curve fitting toolboxes of Mathematica software. We perform a series of experimental tests and then try to numerically find the best fit for parameters values receiving \(b=7.2662\times {\mathrm {10^{-6}\,Nm\,s}}\) and \(c=4.9877\times 10^{-9}\,{\mathrm {Nm\,s^{3}}}\).

After determining the parameters values we perform a series of experiments to validate the mathematical model. Tests include both oscillatory motion and rotations with relatively high rotational speeds both in clockwise and counterclockwise directions. In Fig. 2 we compare the experimental data with the results from direct numerical integration of the model. Panels (a, b) refer to oscillatory motion of the pendulum for the first considered angle of inclination (\(\alpha =5.4^{\circ }\)). Initial conditions for the first trial [panel (a)] were \(\varphi _{0}=-2.0\,\mathrm{rad}\), \(\dot{\varphi }_{0}=0.0\,\mathrm{rad/s}\) and for the second trial [panel (b)] \(\varphi _{0}=0.0\,\mathrm{rad}\), \(\dot{\varphi }_{0}=7.5\,\mathrm{rad/s}\).

In general we see that the results of numerical simulations are qualitatively the same as the experimental data. Still, we observe a slight difference when the amplitude of oscillations decay [panels (a) and (b)]. This is mainly due to the fact that the main goal during fitting the parameter values was to achieve the best convergence to the numerical data for high-speed rotations (in the range of values for which the PPs are anticipated to occur). In oscillatory motion the angular velocity never exceeds \(8\,\mathrm{rad/s}\) and the numerical results diverge from experimental data with the decrease in the angular velocity.

In panels (c, d, e, f) we present the comparison for rotations in the clockwise (d, f) and counterclockwise (c, e) directions. We use double vertical axes: angular displacement in [rad] on the left and number of consecutive rotations (revolutions [-]) on the right. For rotations we present the results for both considered angles of inclination. Panels (c, d) refer to \(\alpha =5.4^{\circ }\) and (e, f) to \(\alpha =22.8^{\circ }\). The initial conditions for direct numerical integration are the following: \(\varphi _{0}=0.0\,\mathrm{rad}\), \(\dot{\varphi }_{0}=56.0\,\mathrm{rad/s}\) for panel (c); \(\varphi _{0}=0.0\,\mathrm{rad}\), \(\dot{\varphi }_{0}=-\,87.0\,\mathrm{rad/s}\) for panel (d), \(\varphi _{0}=0.0\,\mathrm{rad}\), \(\dot{\varphi }_{0}=100.0\,\mathrm{rad/s}\) for panel (e) and \(\varphi _{0}=0.0\,\mathrm{rad}\), \(\dot{\varphi }_{0}=-\,75.0\,\mathrm{rad/s}\) for panel (f). For both considered angles of inclination the results of numerical simulations are in remarkable agreement with the experimental data. Therefore, we claim that the numerical model is robust enough to simulate the behavior of the system in the vicinity of PPs with good precision.

4 Investigation of perpetual points

In this section we consider PPs in the dynamical model described in the previous section. We start with analytical derivations to obtain exact formulas which describe how location of PPs depends on the parameter values. Then, we numerically investigate the vicinity of PPs in the phase space. Finally, we describe the experimental procedure that we carry out to detect the location of PPs. We present the experimental results and asses their accuracy.

4.1 Analytical derivation

To derive PPs analytically we first need to rewrite Eq. 9, which is a second-order ODE, as a set two first-order ODEs. For that purpose we assume that:

and thus obtain the following set of first-order ODEs:

The PPs are given by the following set of equations:

Comparison between the experimental data (orange) and the results from a direct numerical integration (blue) of Eq. 8. Panels a, b show oscillatory motion of the pendulum, while c, d, e, f show fast (multiple) rotations. Panels a, b, c, d refer to \(\alpha =5.4^{\circ }\), while e, f to \(\alpha =22.8^{\circ }\). For rotary cases, the right axes indicate the number of consecutive rotations. (Color figure online)

Using the above formula we can derive the PPs analytically, resulting in:

It is important to notice that the system under consideration has the following property:

and thus the jerk is equal to zero when \(\varphi =(n+0.5)\pi \). It is a specific feature of the investigated system and strongly simplifies our analysis.

For the sake of simplicity we assume that \(\varphi =(\varphi -\pi )\,{\mathrm {mod\,}}2\pi \) and get \(\varphi \in \left\langle -\pi ,\,\pi \right\rangle \,\mathrm{rad}\). Then, using the above formulas we calculate PPs. For the first considered angle of inclination \(\alpha =5.4^{\circ }\) we obtain:

and for the second considered angle of inclination \(\alpha =22.8^{\circ }\) we get:

We see that in this model it is potentially feasible to reach a PP since they appear at much lower angular velocities than for typical experimental rigs with pendula (see Table 1). Two important elements in achieving this accessibility was the tilting the axis of the pendulum, and adding the plastic strip to increase the drag. These modifications allowed the parameters values to be adjusted resulting in a dramatic decrease in the angular velocities at PPs.

4.2 Numerical analysis

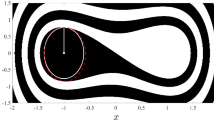

After deriving the PPs analytically, now we turn to numerical solutions of the ODEs. In Fig. 3 we show trajectories of the system near PP. To present the behavior of the system we use 3D plots with angular displacement \(\varphi \), velocity \(\dot{\varphi }\) and acceleration \(\ddot{\varphi }\) on abscissa, ordinate and applicate, respectively. Hence, we are able to depict the surface of zero acceleration (gray half-transparent surface). Moreover, due to the fact that the zeros of pendulum jerk are constrained to a specific angle (see Eq. 14) we can also simply display the surface of zero jerk (yellow half-transparent surface). Therefore, the PPs must occur at the line of intersection of these two planes and we mark their position with a special marker.

3D plots of the trajectories in the vicinity of PPs. Panels a, b refer to the first considered angle of inclination \(\alpha =5.4^{\circ }\), while c, d to \(\alpha =22.8^{\circ }\). Panel b is the zoom up of panel (a), and panel d is the zoom up of panel (c). In each panel we show trajectories obtained starting from initial conditions given in Table 3

Panels (a, b) of Fig. 3 were calculated for the first considered angle of inclination \(\alpha =5.4^{\circ }\). In panel (a) with lines of different colors we show 7 trajectories that start from different initial conditions that are given in Table 3 with the corresponding line colors. In Panel (b) we magnify the close neighborhood of the PP. Similarly, in panels (c, d) we consider the system assuming the second angle of inclination \(\alpha =22.8^{\circ }\). In panel (c) we show the trajectory that goes through the PP and 7 nearby trajectories (for initial conditions and line colors see Table 3). In panel (d) we magnify the local neighborhood of the PP. In all the panels with the bold red line we highlight the trajectory that starts from the PP and with the bold blue line the trajectory that approaches the PP.

Analyzing Fig. 3 we see that it is not that difficult to reach the neighborhood of PPs. Still, there is a significant difference between the two considered angles of inclination. To simplify the comparison we maintain the same axis ranges for panels (a, c) and (b, d). We see that the trajectories are much more dense for the first angle of inclination [panels (a, b)] than for the second one [panels (c, d)]. Hence, it is much easier to reach (or pass near) the PP if it occurs at low angular velocity which confirms the conclusions from Sect. 2. Still, simulations presented above show that for the considered system it should be possible to reach close vicinity of PP in a series of experiments.

4.3 Experimental investigation

In this section, we present the experimental procedure to locate PPs and apply it for the two considered angles of inclination. Our investigation is based on a large series of experimentally obtained time traces. For each trial we use PASCO CI - 6538 rotary motion sensor and PASCO ScienceWorkshop® 750 Interface Model No. CI-7599 to track the angular displacement of the pendulum. The above setup enables \(1\,{\mathrm {kHz}}\) sampling rate with \(1^{\circ }\) precision of angle measurements.

Each experimental time series we seek initial conditions which fulfill the requirement that the initial angular velocity should be at least equal to the analytically obtained velocity at PP. We realize this by simply hitting the pendulum with an impulsive strike. This enables us to reach adequate initial angular velocities of about \(120\,\mathrm{rad/s}\). For both angles of inclination we perform 150 trials—75 in the clockwise and 75 in the counterclockwise directions. This give us time traces which are then post-processed with Mathematica software. Finally, we analyze the results and try to estimate the location of PPs based on the experimental data only.

4.3.1 Post-processing of the acquired data

The angle measurement device provided good precision, with good spatial and temporal resolution. However, the main problem is that we are only able to track the position of the pendulum \(\varphi \) in time, while to obtain PPs we need to analyze the first, the second and the third derivative of the angular displacement which causes huge problems. Because of the discrete nature of the acquired (inevitably slightly noisy) experimental data, the familiar problem of noise amplification on differentiation was encountered. That is one of the reasons why time lag embedding, where instead of calculating the exact values of the derivatives we look at the signal with some constant delay, is a popular approach in nonlinear dynamics. Still, in our case this method is not suitable because to detect PPs we need to track the actual values of the velocity, acceleration and jerk. Therefore, we use the following post-processing procedure to obtain these quantities from the acquired data.

In the fist step we divide the time trace into single rotations. Then, for each rotation we prepare the dataset by adding 60 data points recorded before the rotation and 60 data points after the rotation. Then, in each dataset we normalize the angular position of the pendulum \(\varphi \) so that the considered rotation starts at \(\varphi =0\,\mathrm{rad}\) and ends at \(\varphi =2\pi \,\mathrm{rad}\) or \(\varphi =-2\pi \,\mathrm{rad}\) for rotations in counterclockwise and clockwise direction, respectively. Then, we take the first point of the dataset and mark the initial position of the pendulum \(\varphi _{0}\) and the initial time \(t_{0}\). Similarly, from the last point of the dataset we take the final position of the pendulum \(\varphi _\mathrm{end}\) and the time \(t_\mathrm{end}\). Using the above we calculate the average angular velocity for a given dataset as:

Then, we fit the following function to the dataset:

For this purpose we use the \({\mathbf {{\mathrm {\mathtt {NonlinearModelFit}}}}}\) function of Mathematica software which optimizes values of the parameters \(C_{i}\) to ensure the best possible fit. We show sample results of this estimation in panels (a) and (e) of Fig. 4 where blue dots correspond to the experimental data and red lines are the estimated \(\varphi \left( t\right) \) functions. Panels (a, b, c, d) correspond to the sample dataset obtained from the time trace recorded for \(\alpha =5.4^{\circ }\), while panels (e, f, g, h) refer to \(\alpha =22.8^{\circ }\).

Effects of the post-processing of the acquired experimental data. Panels a, e show the recorded experimental data (blue dots) and their numerical estimation with a continuous function (red lines). Panels b, f show the evolution of velocity, c, g acceleration and d, h jerk. Red vertical lines indicate the numerically identified possible locations of perpetual points. (Color figure online)

Comparison between the location of PPs obtained analytically (red crosses) and estimated based on the experimental data (green crosses) supplemented with black dots showing the numerically detected possible locations of PPs based on experimental data. Panel a shows the results for \(\alpha =5.4^{\circ }\) and (b) for \(\alpha =22.8^{\circ }\)

Using the above procedure we get continuous functions that describes the evolution of our system which can be efficiently differentiated multiple times to obtain \(\dot{\varphi }\left( t\right) \), \(\ddot{\varphi }\left( t\right) \) and \(\dddot{\varphi }\left( t\right) \). In Fig. 4 we show sample results. It is important to notice that for the earlier and the consecutive rotation we perform a separate estimation. Thus, we are only interested in the range that corresponds to the given rotation. For the sake of clarity in Fig. 4 we use half-transparent lines for the estimations outside this range that should not be considered. We see that within the selected range velocities (green lines), accelerations (orange lines) and jerks (blue lines) are smooth. Moreover, the acceleration and jerk have shapes that were somehow expected—one period of \(\sin \) and \(\cos \) function.

Based on the above estimations we are able to detect points along the experimentally obtained time trace which have both acceleration and jerk close to zero while having nonzero velocity. In Fig. 4 we show the time traces that pass close to the vicinity of PP at time \(t_\mathrm{PP}\) marked with vertical red line. However, they do not pass exactly through PPs and not all orbits go as near PPs as the ones we present. Still, in the next section we show that with a large enough number of trials we are able to predict the position of PPs with satisfactory precision.

4.3.2 Experimental results

As mentioned before, we perform 150 trials for each considered angle of inclination (75 in clockwise and counterclockwise directions). Then, the data recorded in each trial is post-processed as described in the previous subsection. After the post-processing we look for the points at which the jerk is equal to zero. For these points we check whether the absolute value of acceleration is smaller than \(1\,\mathrm{rad/s}^{2}\). Hence, we look for the points that fulfill the following condition:

Each point that fulfills the above conditions is noted down as the potential location of the PP. We detect 121 possible localizations of PPs for the first considered angle of inclination (\(\alpha =5.4^{\circ }\) ) and 45 for the second case (\(\alpha =22.8^{\circ })\). An explanation of the observed difference in the number of detected points can be found in subsection 4.2 where we showed how the orbits behave in the vicinity of PPs for different angles of inclination. Next, we compute the points with minimum average distance from all potential PPs locations, resulting in:

for the angle of inclination \(\alpha =5.4^{\circ }\)and:

for the angle of inclination \(\alpha =22.8^{\circ }\).

The results from the above procedure are presented in Fig. 5. In panel (a) we present the results for the first considered angle of inclination \(\alpha =5.4^{\circ }\) and in panel (b) for the second angle of inclination \(\alpha =22.8^{\circ }\). Black dots mark detected possible localizations of PPs from single time traces; with red crosses we depict the position of PPs obtained analytically, and with green crosses the overall results of the experimental investigation. We also plot dotted lines to better indicate the position of the crosses. The presented results prove that using the procedure described in the paper with enough number of experimental trials we are able to locate PPs with satisfactory precision.

5 Conclusions

In this paper we considered the feasibility of identifying PPs in mechanical systems. We investigated the archetypal model of a physical pendulum. This model is relatively simple and possesses the specific feature that the jerk is equal to zero for a specific angular deflection of the pendulum, a feature that simplifies our investigation. After reviewing some exemplar realizations of experimental rigs from the literature we claim that for most cases PPs occur at high velocities and would be extremely difficult to reach experimentally. Nevertheless, we propose the design of a simple experimental rig with a pendulum in which we are able to reduce velocity at PPs, and reach them in a series of experiments.

We obtained this characteristic by tilting the rotational axis of the pendulum and adding the plastic strip to increase the drag and enhance the energy dissipation. For this specific type of physical pendulum we established PPs analytically, numerically and experimentally assuming two different angles of tilt. We provided an analytical derivation of PPs and show numerical results that reveal how trajectories behave in the vicinity of PPs and in addition show how parameter values affect the probability of reaching the PP.

The results presented reveal the possible utilization of PPs which can be used to identify energy dissipation models. It is a by-product of the performed investigation that we will expand and further analyze in an upcoming paper.

In the final part, we described the experimental investigation undertaken to verify the existence and practical accessibility of PPs. To obtain velocities, accelerations and jerks from raw experimental data we used a specific post-processing procedure that successfully eliminated noise and estimated the evolution of the system with piece-wise continuous functions. The results prove that the proposed procedure is robust and allows an effective estimate of PPs from raw experimental data with good precision.

References

Prasad, A.: Existence of perpetual points in nonlinear dynamical systems and its applications. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 25(02), 1530005 (2015)

Prasad, A.: A note on topological conjugacy for perpetual points. Int. J. Nonlinear Sci. 21(1), 60–64 (2015)

Dudkowski, D., Prasad, A., Kapitaniak, T.: Perpetual points and hidden attractors in dynamical systems. Phys. Lett. A 379(40), 2591–2596 (2015)

Dudkowski, D., Jafari, S., Kapitaniak, T., Kuznetsov, N.V., Leonov, G.A., Prasad, A.: Hidden attractors in dynamical systems. Phys. Rep. 637, 1–50 (2016)

Kuznetsov, N.V.: Hidden attractors in fundamental problems and engineering models: a short survey. In: Duy, V., Dao, T., Zelinka, I., Choi, H.S., Chadli, M. (eds.) AETA 2015: recent advances in electrical engineering and related sciences, pp. 13–25. Springer, Berlin (2016)

Leonov, G.A., Kuznetsov, N.V., Vagaitsev, V.I.: Localization of hidden Chua’s attractors. Phys. Lett. A 375(23), 2230–2233 (2011)

Kuznetsov, A.P., Kuznetsov, S.P., Mosekilde, E., Stankevich, N.V.: Co-existing hidden attractors in a radio-physical oscillator system. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 48(12), 125101 (2015)

Pham, V.T., Vaidyanathan, S., Volos, C.K., Jafari, S.: Hidden attractors in a chaotic system with an exponential nonlinear term. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 224(8), 1507–1517 (2015)

Chaudhuri, U., Prasad, A.: Complicated basins and the phenomenon of amplitude death in coupled hidden attractors. Phys. Lett. A 378(9), 713–718 (2014)

Brzeski, P., Lazarek, M., Kapitaniak, T., Perlikowski, P.: Basin stability approach for quantifying responses of multistable systems with parameters mismatch. Meccanica 51(11), 2713–2726 (2016)

Brzeski, P., Wojewoda, J., Kapitaniak, T. Kurths, J., Perlikowski, P.: Sample-based approach can outperform the classical dynamical analysis—experimental confirmation of the basin stability method. Sci. Rep. 7, 6121 (2017)

Nazarimehr, F., Saedi, B., Jafari, S., Sprott, J.C.: Are perpetual points sufficient for locating hidden attractors? Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 27(03), 1750037 (2017)

Dudkowski, D., Prasad, A., Kapitaniak, T.: Perpetual points: new tool for localization of coexisting attractors in dynamical systems. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 27(04), 1750063 (2017)

Pham, V.T., Volos, C., Jafari, S., Kapitaniak, T.: Coexistence of hidden chaotic attractors in a novel no-equilibrium system. Nonlinear Dyn. 87(3), 1–10 (2016)

Jiang, H., Liu, Y., Wei, Z., Zhouchao, L.: Hidden chaotic attractors in a class of two-dimensional maps. Nonlinear Dyn. 85(4), 2719–2727 (2016)

Pham, V.T., Volos, C., Jafar, S., Kapitaniak, T.: Coexistence of hidden chaotic attractors in a novel no-equilibrium system. Nonlinear Dyn. 87(3), 2001–2010 (2017)

Wei, Z., Pham, V.T., Kapitaniak, T., Wang, Z.: Bifurcation analysis and circuit realization for multiple-delayed wang-chen system with hidden chaotic attractors. Nonlinear Dyn. 85(3), 1635–1650 (2016)

Leonov, G.A., Kuznetsov, N.V., Mokaev, T.N.: Homoclinic orbits, and self-excited and hidden attractors in a Lorenz-like system describing convective fluid motion. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 224(8), 1421–1458 (2015)

Jafari, S., Nazarimehr, F., Sprott, J.C., Golpayegani, S.M.R.H.: Limitation of perpetual points for confirming conservation in dynamical systems. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 25(13), 1550182 (2015)

Nazarimehr, F., Jafari, S., Golpayegani, S.M.R.H., Sprott, J.C.: Categorizing chaotic flows from the viewpoint of fixed points and perpetual points. Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 27(02), 1750023 (2017)

Ueta, T., Ito, D., Aihara, K.: Can a pseudo periodic orbit avoid a catastrophic transition? Int. J. Bifurc. Chaos 25(13), 1550185 (2015)

de Paula, A.S., Savi, M.A., Pereira-Pinto, F.H.I.: Chaos and transient chaos in an experimental nonlinear pendulum. J. Sound Vib. 294(3), 585–595 (2006)

Zilletti, M., Elliott, S., Ghandchi Tehrani, M.: Electromechanical pendulum for vibration control and energy harvesting In: EACS 2016—6th European conference on structural control at Sheffield, England (2016)

Kecik, K., Brzeski, P., Perlikowski, P.: Non-linear dynamics and optimization of a harvester–absorber system. Int. J. Struct. Stab. Dyn. 17(5), 1740001 (2016)

George, C., Virgin, L.N., Witelski, T.: Experimental study of regular and chaotic transients in a non-smooth system. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 81, 55–64 (2016)

Lenci, S., Rega, G.: Experimental versus theoretical robustness of rotating solutions in a parametrically excited pendulum: a dynamical integrity perspective. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 240(9), 814–824 (2011)

Marszal, M., Witkowski, B., Jankowski, K., Perlikowski, P., Kapitaniak, T.: Energy harvesting from pendulum oscillations. Int. J. Non-Linear Mech. 94, 251–256 (2017)

Acknowledgements

P. Brzeski is supported by the Foundation for Polish Science (FNP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary material 1 (mpg 29746 KB)

Supplementary material 2 (mpg 46720 KB)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Brzeski, P., Virgin, L.N. Experimental investigation of perpetual points in mechanical systems. Nonlinear Dyn 90, 2917–2928 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-017-3852-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11071-017-3852-z