Abstract

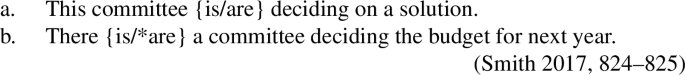

This work investigates the morphosyntax of nominal expressions in Standard Italian that have multiple adjectives in “split coordination,” which permits a plural noun to be modified by singular adjectives, for example le mani destra e sinistra (the hand.pl left.sg and right.sg). The proposal is (i) that these expressions are built from multidominant structures, with a constituent shared by the conjuncts, and (ii) that plural marking on the noun reflects “summative” feature resolution on the nP comparable to coordination resolution. This proposal captures various properties of split-coordinated expressions, including the availability of adjective stacking and of feature-mismatched conjuncts, as well as agreement with a class of nouns that “switch” gender in the plural. Taking agreement with resolving features to be a form of semantic agreement, which has been argued to be possible only in certain syntactic configurations (Smith 2015, 2017, 2021), the account captures prenominal-postnominal adjective asymmetries in split coordination. The work offers a coherent account of coordination and semantic agreement in the nominal domain, connects split coordination to related phenomena such as nominal right node raising and adjectival hydras, and, more broadly, evinces the unity of nominal and verbal agreement, pace analyses of nominal concord (Norris 2014).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Coordinated expressions can receive either an intersective (“joint”) interpretation, as in (1a), or a split (“collective”) interpretation, as in (1b) (Winter 1998; Heycock and Zamparelli 2005; Champollion 2016).

-

(1)

The coordinated expression in (1a) refers to a single individual who is both a liar and a cheat. In (1b), the coordination of two singular nouns refers to a group comprised of two individuals: one man and one woman. The number of individuals has a corresponding effect on verbal agreement: in (1a), the individual interpretation induces singular agreement, whereas in (1b), the group interpretation induces plural agreement.

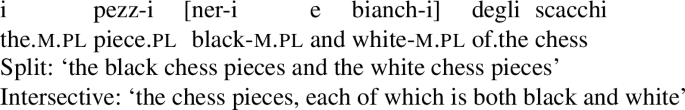

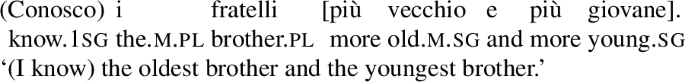

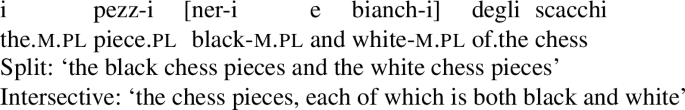

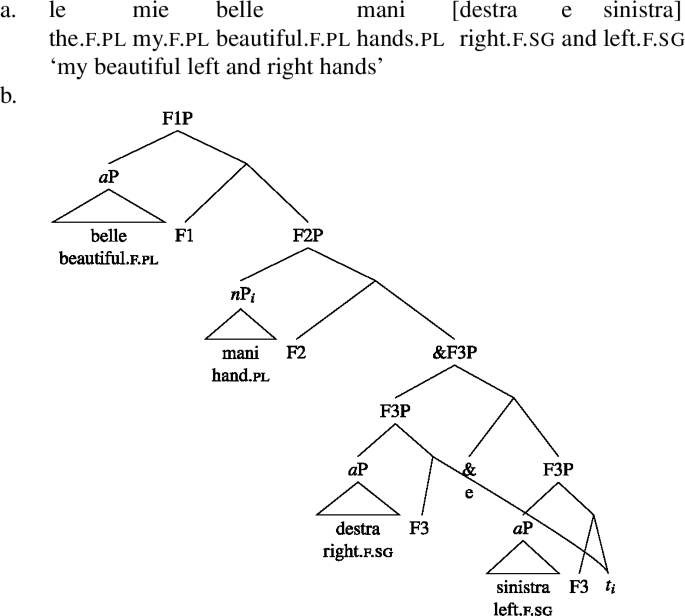

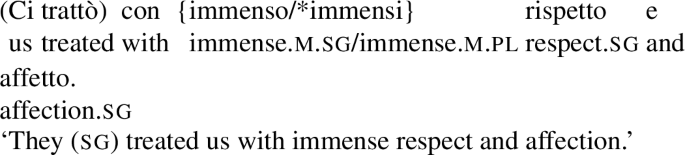

The intersective-versus-split dichotomy extends to modifiers. In the Standard Italian example in (2), a coordinated expression consists of a plural nounFootnote 1 modified by two adjectives, which can have either a split or an intersective interpretation (the latter being less plausible for the meaning in (2)).

-

(2)

As evident from (2), when the adjectives in split coordination (henceforth “SpliC,” pronounced “splice”) pick out groups of multiple individuals, adjectival inflection is plural (see also (3)). Strikingly, when SpliC adjectives in Italian each pick out one individual, a plural noun can be modified by singular adjectives, as in (4) and (5) (see also Belyaev et al. 2015 on Italian, and Bosque 2006 on Spanish).

-

(3)

-

(4)

-

(5)

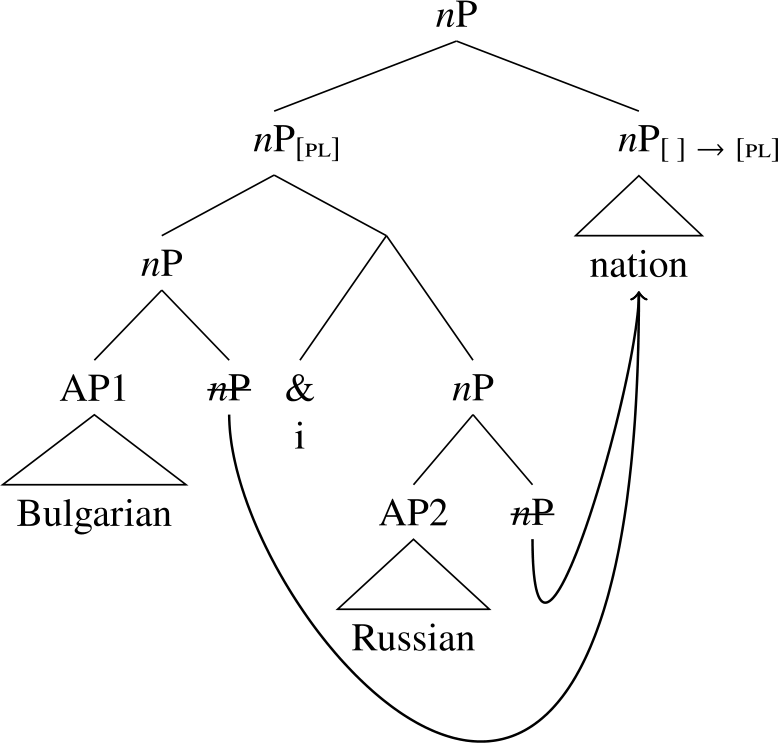

This presents a puzzle: if adjectives agree with a noun, and the noun is plural, where do singular features on the adjectives in expressions like (4) and (5) originate? In this article, I argue for a multidominant analysis of split-coordinated (SpliC) nominal expressions. For SpliC adjectives, an nP node is shared by two (or more) conjuncts and has two (or more) sets of nominal features, with each adjective agreeing with a distinct set. (The pronunciation of the “SpliC” abbreviation as “splice” is thus fitting for the analysis; it is as if coordinated expressions are “spliced” together at a shared node.) The features on nP come to be resolved in a way comparable to coordination resolution, yielding plural marking on the noun. The analysis extends Grosz’s (2015) treatment of so-called summative agreement in verbal right node raising (RNR), from agreement targets like T to agreement controllers like n.

The structural components of the account are as follows. I adopt a roll-up derivation of the Italian nominal domain (Cinque 2005, 2010, 2014), whereby postnominal order of adjectives is the result of phrasal movement of nP, or of phrases dominating nP. Following Cinque, I assume adnominal adjectives are hierarchically organized in a rigid sequence within the nominal domain. Their linear order with respect to the noun is determined through phrasal movements, and the order is read off from the c-command relations in the structure (cf. the Linear Correspondence Axiom of Kayne 1994). I take aPs to be merged as specifiers of functional projections along the nominal spine.Footnote 2 A simplified example is given in (6) for a syntactic derivation yielding a postnominal order.

-

(6)

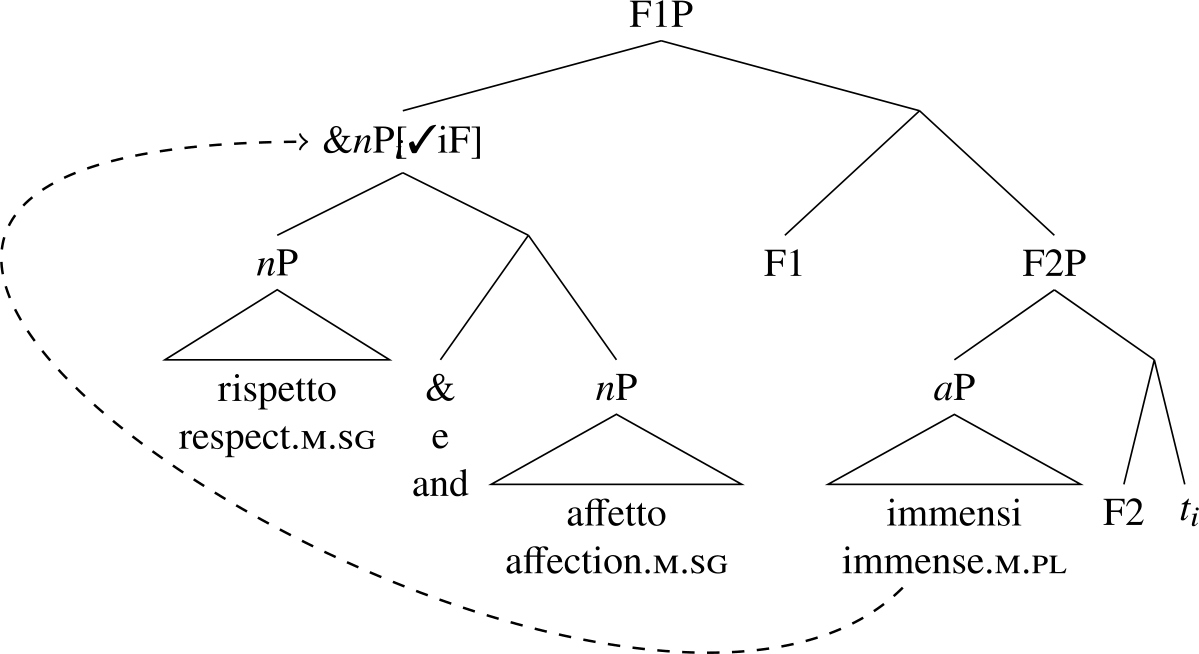

Coordination is represented asymmetrically, following Munn (1993) and others, though nothing hinges on this. For the SpliC example in (4), the nP bears two [sg] features (distinguished by indices), each of which is agreed with by one of the conjuncts. The two [sg] features on the nP are resolved as [pl], yielding plural marking on the noun. These components of the analysis are sketched in (7), which depicts the lower part of the nominal structure for (4). The nP in (7) is Parallel Merged (in the sense of Citko 2005) in its base position, and this constituent moves into the specifier position of a higher FP above the coordinated phrase.

-

(7)

In addition to capturing facts for SpliC expressions, the multidominant analysis lays the foundations for an account of an agreement asymmetry between prenominal and postnominal adjectives. While postnominal SpliC adjectives yield the resolving pattern described above, prenominal SpliC adjectives present a different pattern, where the expressed number values must match between the adjectives and the noun (8) (see also Belyaev et al. 2015):

-

(8)

I argue that the prenominal-postnominal asymmetry follows from a configurational condition on semantic agreement, which has been independently proposed for other phenomena. By hypothesis, the features involved in number resolution are semantic features (interpretable features, or iFs), which are only visible to a probe if it does not c-command the goal (9a), a condition (almost identical to the one) proposed by Smith (2015, 2017, 2021) for semantic agreement with hybrid nouns.Footnote 3 Prenominal adjectives c-command their nPs, and therefore cannot agree with them in semantic features (9b).

-

(9)

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides the details of the multidominant structure for SpliC expressions and shows how it captures various structural patterns. Section 3 offers an account of agreement in SpliC expressions in terms of a dual feature system and an explicit formulation of resolution, which is hypothesized to occur in the context of semantic agreement in a restricted syntactic configuration. This section highlights related phenomena of nominal RNR and adjectival hydras, and advances an analysis of asymmetric behavior between pre- and postnominal SpliC adjectives. Section 4 evaluates alternative analyses of SpliC expressions, demonstrating that they face empirical challenges. In Sect. 5, I address a putative challenge to the present account coming from gender agreement with a class of nouns that “switch” gender in the plural, and argue that on closer inspection, the analysis is capable of capturing these facts. Section 6 adapts the analysis for cross-linguistic extensions. Section 7 concludes by discussing theoretical implications for coordinate structure and agreement in the nominal domain.

2 Split coordination and multidominance

In this section, I demonstrate how the multidominant analysis of SpliC adjectives correctly captures various structural patterns, and provide derivations of SpliC expressions in different grammatical contexts. I focus presently on postnominal SpliC adjectives with the resolving pattern and discuss other SpliC expressions in Sect. 3.

In Standard Italian, gender (m and f) and number (sg and pl) are nominal features reflected in the inflection of nouns, adjectives, determiners, possessive pronouns, and other elements (see e.g. Maiden and Robustelli 2013). Adjectives appear either pre- or postnominally, depending on a number of syntacticosemantic determinants (Zamparelli 1995; Cinque 2010, 2014; among others). I postpone my discussion of gender and number agreement to Sect. 3.

Multidominant structures (McCawley 1982; Wilder 1999; Citko 2005; Gračanin-Yuksek 2007, 2013; Bachrach and Katzir 2009, 2017; Grosz 2015; Shen 2018; among many others) have been proposed or entertained for other phenomena found in Italian, including verbal RNR (10) (Grosz 2015; Shen 2018, 2019) and adjectival “hydras” (11) (Bobaljik 2017). (The judgment in (10) is from Grosz 2015.) Like SpliC expressions, verbal RNR and adjectival hydras allow “cumulative” plural marking: on verbal agreement in the former and adjectival agreement in the latter.

-

(10)

-

(11)

I propose that nominal SpliC expressions in Italian are also multidominant. In the simplest case, two (or more) conjuncts each include a distinct aP but structurally share the same nP. For postnominal adjectives, the nP moves to produce the expected postnominal order (12). I postpone the discussion of agreement to Sect. 3. I assume that multidominance is constrained by the requirement that expressions be linearizable. (Regarding the linearization of shared constituents in multidominant structure, see Gračanin-Yuksek 2007, 2013; Bachrach and Katzir 2009, 2017.)

-

(12)

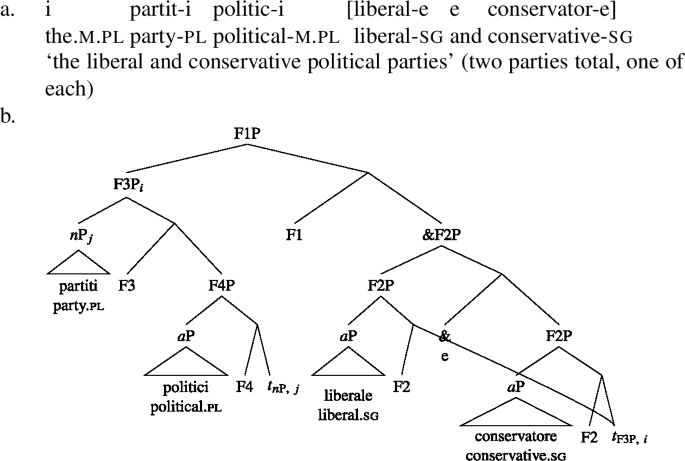

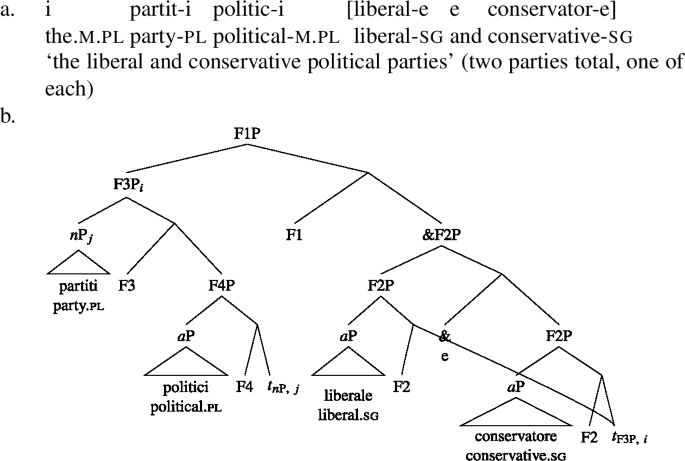

A multidominant account makes several correct predictions. First, it should be possible for more complex phrases to be shared between conjuncts, such as a modified noun (an FP). We indeed observe this in (13a), which has a postnominal modifier politici ‘political’ modifying the noun partiti ‘parties,’ with this entire expression shared by two conjuncts, each which has its own singular modifier (liberale and conservatore, respectively). See the derivation in (13b): there is nP movement internal to the shared phrase to derive the postnominal order of partiti politici, and there is movement of this larger shared phrase to derive the postnominal order of the SpliC adjectives.

-

(13)

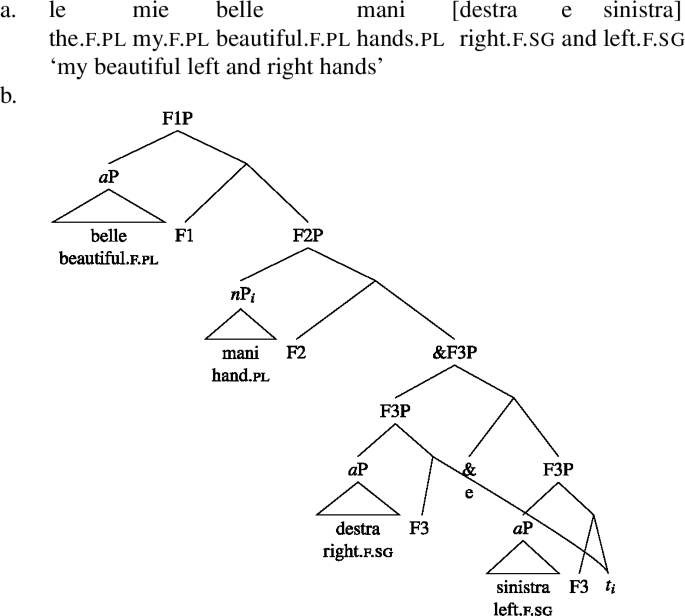

Second, it should be possible for an aP to merge above the conjunction, modifying the collective group denoted by the coordinated phrase. This is indeed borne out; see (14a), which includes modification of the SpliC expression by a prenominal adjective (modification by a postnominal adjective would also be possible). See the syntactic derivation in (14b); here the shared nP again moves, this time outside of the coordinate structure, and the prenominal aP merges higher in the nominal domain.

-

(14)

Third, adjectival stacking in each conjunct should be allowed, with more than one adjective appearing in each conjunct. While marked (with varying levels of degradation), these are indeed accepted by my consultants, as (15)–(17) show.

-

(15)

-

(16)

-

(17)

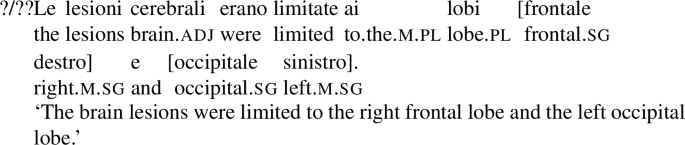

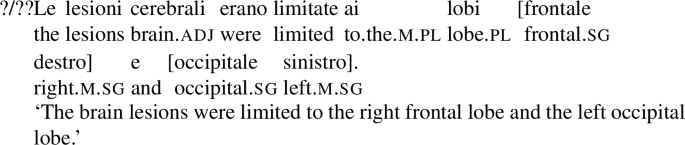

I note that these examples involve multiple instances of sharing, which I suggest is responsible for their degradation. The derivation of (17) is provided in (18). In this tree, two large phrases (F1Ps) are conjoined, which each dominate two aPs and which share the nP (containing the noun lobi); this shared nP moves to a specifier position also shared across the two conjuncts. Roll-up movement occurs so that two distinct phrases F3P (each containing the shared, moved nP) move to the specifiers of their respective F1Ps. (See Fn. 15 on the derivation of agreement with adjective stacking.)

-

(18)

Lastly, for completeness, observe that NP ellipsis is also acceptable with SpliC expressions. In the example in (19), the demonstrative still agrees in the plural, reflecting the presence of an unpronounced plural noun, which nevertheless co-occurs with singular SpliC adjectives. Under the present analysis, this is consistent if the nP is what is elided.

-

(19)

To summarize so far, the multidominant analysis of such expressions correctly captures that larger expressions than nP can be shared, that the entire coordinate phrase can be modified, and that adjectival stacking is permitted; it is also consistent with ellipsis facts. While some alternative approaches may be able to contend with these facts, I discuss empirical challenges to these approaches in Sect. 4.

3 Summative agreement and agreement asymmetries

I now address how agreement is established between nouns and adjectives in SpliC structures under my proposal, yielding the striking pattern of singular adjectives modifying a plural noun, among other interesting patterns. I point to an agreement asymmetry for split coordination with prenominal versus postnominal adjectives, and argue that this stems from the asymmetry observed in other domains for “semantic agreement” (Smith 2015, 2017, 2021). (See also Munn 1999 on agreement asymmetries with coordination involving what is described as “semantic agreement.”) It is shown that the semantic agreement analysis makes correct predictions for SpliC nouns as well as for the distribution of feature mismatches between conjuncts.

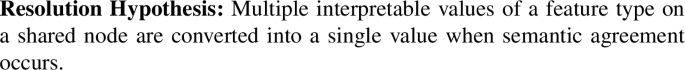

My analysis of agreement in these constructions is reducible to three main hypotheses, stated in (20)–(22). In essence, the proposal is that shared nouns have multiple features, and these features are resolved to single values in specific agreement contexts. This yields our pattern of interest (among others), with singular postnominal adjectives modifying a plural noun.

-

(20)

-

(21)

-

(22)

These hypotheses will require some unpacking, but broadly speaking, we can say for (23) that the nP containing mani ‘hand.pl’ bears two interpretable singular number features corresponding to its two distinct subsets (one left, one right). The adjectives each agree with one of these interpretable features, and consequently resolution applies, yielding plural marking on the noun.

-

(23)

The structural restriction on semantic agreement offers a way of capturing an asymmetry between postnominal and prenominal SpliC adjectives. While two (or more) postnominal singular adjectives can modify a plural-marked noun, two (or more) prenominal singular adjectives can only modify a singular-marked noun (see also Belyaev et al. 2015), as illustrated by (24)–(26).Footnote 4 This is captured by my account, given that prenominal aPs c-command nPs they agree with, and therefore cannot participate in semantic agreement and consequently cannot participate in resolution. (See Nevins 2011; Bonet et al. 2015 for analyses of other prenominal-postnominal agreement asymmetries in Romance in structural terms.) I walk through this more explicitly below.

-

(24)

-

(25)

-

(26)

In spelling out the details of the account, I first address the connection between multidominance and resolution, focusing in Sect. 3.1 on the hypotheses in (20) and (21). I then offer a more detailed analysis of agreement, showing how “semantic agreement” fits within this system in Sect. 3.2. In Sect. 3.3, I provide derivations that highlight how the singular-plural mismatch pattern between adjectives and nouns arises, as well as the asymmetry between prenominal and postnominal SpliC adjectives. I demonstrate further that the account correctly captures agreement patterns in SpliC expressions throughout the nominal domain, as well as the distribution of feature mismatch patterns, and also extends to SpliC expressions in which there are multiple nouns rather than multiple adjectives.

3.1 Summative agreement in multidominant structures

My approach to agreement in SpliC expressions implicates multidominance: in particular, feature resolution occurs on a shared node that enters into agreement with elements in distinct conjuncts. This approach is adapted from Grosz’s (2015) account of verbal RNR, which exhibits what Grosz refers to as “summative agreement” (see also Yatabe 2003 and references therein). Summative agreement can in fact be seen both in verbal RNR and in adjectival hydra constructions, both of which have received multidominant analyses in the literature. I discuss each in turn before addressing SpliC expressions.

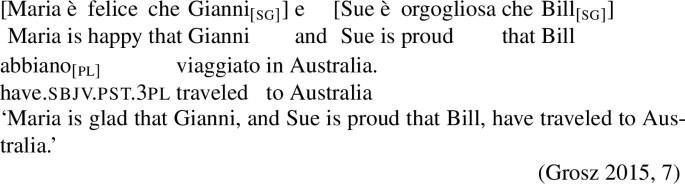

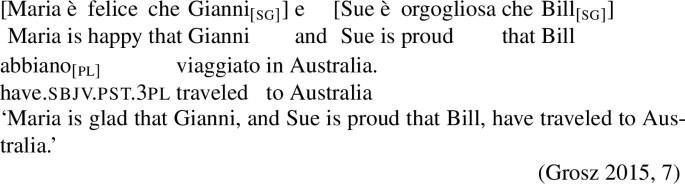

In English and other languages, finite T shared in verbal RNR can exhibit plural agreement with two singular subjects (27). Italian speakers are also reported to permit summative agreement in verbal RNR (28) (see also Grosz 2015; Shen 2019).

-

(27)

-

(28)

Grosz (2015) proposes that summative agreement on finite T is the result of agreement with multiple goals: in the case of (27) and (28), with two singular subjects. The shared T head agrees with both subjects, whose features bear distinct referential indices, reflecting that the features are identified with different referents. With T bearing two [sg] features, resolution subsequently yields a plural feature, which is expressed in the realization of agreement on T. I henceforth refer to feature resolution on a shared node in a multidominant structure as “summative resolution.” The tree in (29) offers a representation of Grosz’s analysis.Footnote 5 By hypothesis, the feature calculus in summative resolution operates the same way as in coordination resolution, such that two singular features are converted into a plural value.

-

(29)

Adapted from Grosz (2015, 18)

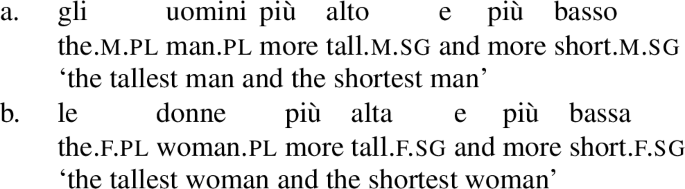

Beyond verbal RNR, summative agreement can also be found between nominals and agreeing adjectives. Bobaljik (2017) observes that various Romance languages allow two singular DPs to be modified by the same plural postnominal adjective, in what are sometimes called “adjectival hydra” constructions. This is true for Italian:

-

(30)

-

(31)

Given the presence of determiners in both conjuncts, two DPs seem to be coordinated, which should not be constituents to the exclusion of the adjective that modifies them. An analysis germane to the current approach would build adjectival hydras like those in (30) and (31) with multidominant structure, with two DPs coordinated and a shared aP. A multidominant, summative account of adjectival hydras is in fact suggested by Bobaljik (2017).Footnote 6 (32) illustrates a syntactic derivation of (31) that employs both multidominant structure and summative resolution: the shared aP agrees with the features of both nPs, and comes to resolve these number values into a plural value.

-

(32)

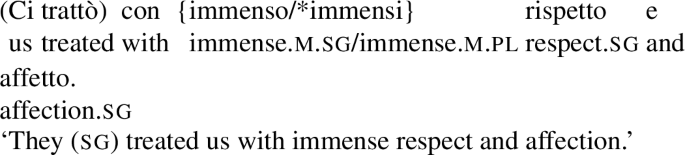

Resolution is not limited to number; gender resolution can also be seen with gender-mismatched conjuncts in adjectival hydras. In coordination resolution, when one conjunct is feminine and the other is masculine, agreement with the coordinate phrase is masculine: this is true both for animates (33) and inanimates (34).

-

(33)

-

(34)

If summative resolution with adjectival hydras is like coordination resolution, the expectation is that gender mismatch should also yield masculine agreement. This is correct: in (35), we see that the adjective bears m.pl inflection, reflecting resolved agreement with gender-mismatched nouns.

-

(35)

The derivation of gender resolution is controversial, though researchers generally agree that it can involve both uninterpreted grammatical gender features and “semantic” gender (broadly construed); see Corbett (1991), Wechsler and Zlatić (2003), Wechsler (2008), Adamson and Anagnostopoulou (2024); among many others. For concreteness, I follow the view of gender resolution according to which semantic resolution applies in the case of animates (e.g. Adamson and Anagnostopoulou 2024), yielding feminine for a group consisting of women and masculine for a gender-mixed group or a group consisting of men (cf. Corbett 1991; Wechsler 2008); see Ferrari-Bridgers 2007 on Italian specifically). I will use privative features f and m for expository purposes, though other possibilities are also available.

-

(36)

For inanimates, according to Adamson and Anagnostopoulou (2024), there are two options. When there are matched (uninterpretable) gender features, no semantic resolution operation is performed on them, and the features remain as they are, as two distinct (sets of) gender features. This is not an issue for PF, as realization can yield a single output. The inflection thus expresses whatever the shared feature value is; conflicting feature values would yield distinct realizations and would therefore result in ineffability. See Citko (2005), Asarina (2011), Hein and Murphy (2020) for related formulations for RNR contexts.

-

(37)

For mismatched features with inanimates, a few analytic options would suffice to yield a masculine value. Adamson and Anagnostopoulou (2024) argue that neuter resolution with Greek mismatched inanimates is also semantic in character, and it is possible that the Italian masculine resolution can be viewed the same way. Resolution with mismatched inanimates would then look the same as in (36).

We now return to the link between multidominance and resolution. I suggest on the basis of what I have discussed so far that there is a link between multidominance and summative agreement, which is supported by verbal RNR, adjectival hydras, and SpliC expressions. I propose that the connection should be decomposed into two parts: (38) and (39).

-

(38)

-

(39)

That resolution occurs in the context of semantic agreement is in harmony with the view that coordination resolution involves semantic features for both notional gender (e.g. Anagnostopoulou 2017; Adamson and Anagnostopoulou to appear; Adamson and Anagnostopoulou 2024) and number (Harbour 2020 and references therein).

The independence of (38) from (39) implies that multiple features can be on a shared phrase that do not get converted into a single value. Evidence for this comes from nonresolving agreement (or “morphological” agreement), which is an option for verbal RNR (40) (see Shen and Smith 2019 for extensive discussion), adjectival hydras (41), and SpliC expressions (42). (In these examples, resolved agreement is also available, as indicated.) In such cases, semantic agreement does not occur, so resolution fails to occur: multiple [sg] features remain on the shared element, and are realized at PF with a singular form (see also Shen and Smith 2019 on this analysis). This environment is also parallel to what was described above for multiple nonresolving gender features (37); for number, two (sets of) [sg] features can receive the same realization at PF. (The next subsection describes nonresolving agreement in further detail in the context of SpliC expressions.)

-

(40)

-

(41)

-

(42)

For verbal RNR and adjectival hydras, a probe is shared (T and aP, respectively) and enters into agreement with multiple goals, coming to carry multiple values of the same feature type. The combined set of feature values on the probe can then be resolved to single values.

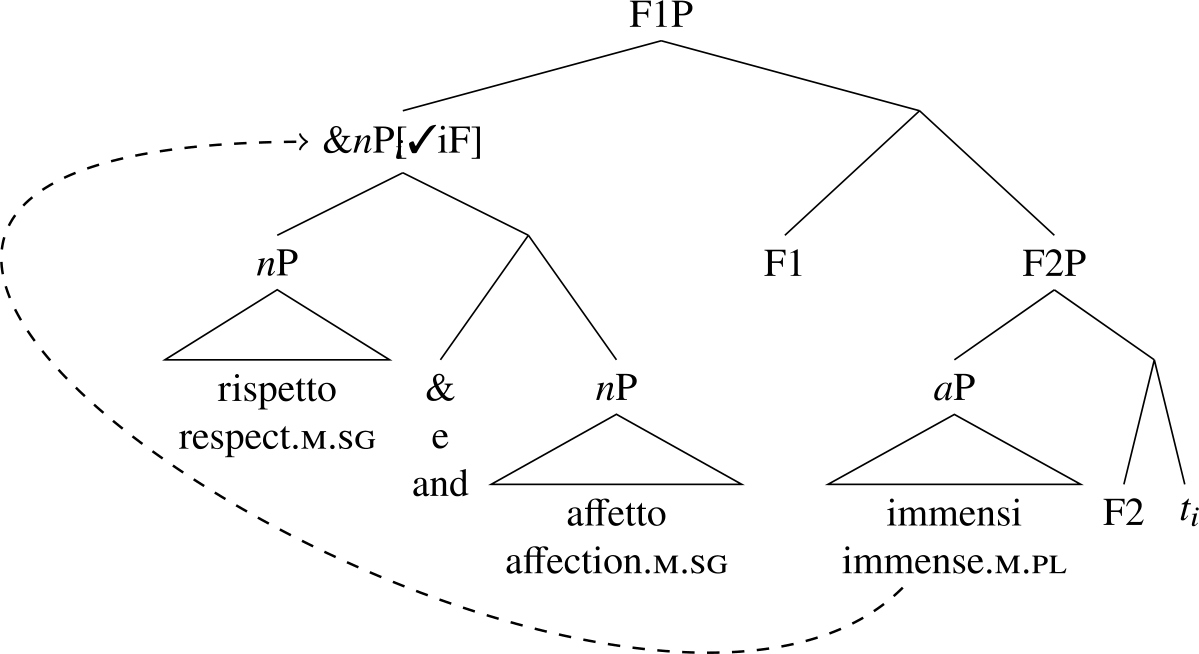

Turning to split coordination, my proposal is that (38) and (39) are also operative here, though for SpliC adjectives, summative resolution occurs on a goal nP.Footnote 7 Each probing aP agrees with the resolving features of nP, and resolution converts the multiple features on the nP into a single value (see (43), repeated from (7)). (Note that summative resolution is only grammatical with postnominal adjectives, a point to which I return in Sect. 3.2.)

-

(43)

Setting aside for the moment the issue of adjective agreement, a summative analysis of SpliC expressions captures the fact that feature mismatch between conjuncts is possible, with number resolution yielding plural and gender mismatch yielding masculine.Footnote 8 Number mismatch is shown in (44); gender mismatch is also grammatical for some speakers, as (45) shows.Footnote 9 The expected pattern of resolution arises in both cases (46), the gender resolution being apparent from the determiner agreement. (I ignore the geometric realities of trapezoids presently.)

-

(44)

-

(45)

-

(46)

To summarize so far, postnominal adjectives in SpliC constructions agree with nominal phrases that bear multiple values for number (and gender). The adjectives agree with independent values of the nP—as is discussed further below—and the multiple values on the nP are resolved as they are in the case of coordination resolution. This account captures agreement in a related type of construction with adjectival hydras, and it correctly derives the results of gender- and number-mismatched adjectives.

Recall from my Resolution Hypothesis (39) that converting values of some feature type is limited to cases of semantic agreement. As of yet, I have not defined what semantic agreement is nor the conditions under which it occurs. Doing so will necessitate a more elaborate discussion of how agreement proceeds. This will allow us to restrict the environments in which we observe the resolution pattern in split coordination to postnominal adjectives.

3.2 Analyzing agreement

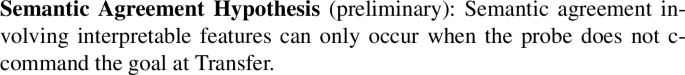

My hypothesis concerning semantic agreement is restated in (47), which contains two components I now address in turn: interpretable features and the structural condition.

-

(47)

Semantic Agreement Hypothesis (preliminary): Semantic agreement involving interpretable features can only occur when the probe does not c-command the goal at Transfer.

The model of the grammar I assume can be identified with the Distributed Morphology framework (Halle and Marantz 1993; Halle 1997; Harley and Noyer 1999; Bobaljik 2000; Embick 2010; Arregi and Nevins 2012; Harley 2014; among many others). I adopt the standard Y-Model in which abstract elements in the syntax are realized postsyntactically in the PF component.

Following Smith (2015, 2017, 2021), I adopt a dual feature system in which ϕ features can have two halves: an uninterpretable value (uF) that is sent to PF and an interpretable value (iF) that is sent to LF; see also Wurmbrand (2012, 2016, 2017), Anagnostopoulou (2017), Shen and Smith (2019), Adamson and Anagnostopoulou (2024). (This dichotomy is related to the concord vs. index distinction from Wechsler and Zlatić 2003; Wechsler and Hahm 2011; Landau 2016a; related work.) Under the system I adopt, depicted in (48), uFs and iFs are both present in the narrow syntax. I further assume that uF values (“uFs”) are sent to the PF branch after Transfer, and are therefore the features that come to be realized, while iFs are sent to the LF branch after Transfer, and therefore come to be interpreted. uF values can be, for example, gender feature values assigned by nonsemantic criteria (Kramer 2015) or number feature values in the case of, for example, collective nouns like committee (Smith 2021).

-

(48)

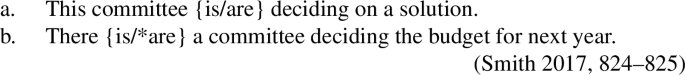

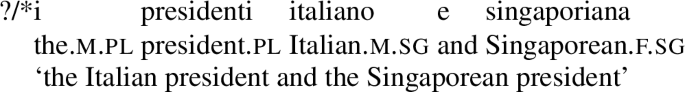

While uF and iF values often match, it is possible for them to differ from each other. According to Smith, this is the case for committee nouns, which can bear different values for number in British English (49) (as well as in other varieties), giving rise to the agreement mismatch pattern in (50), whereby agreement targets can diverge in which number value they express with the same controller.

-

(49)

(Smith 2017, 836)

(Smith 2017, 836)

-

(50)

This[sg] committee are[pl] deciding on a solution. (Smith 2017, 824–825)

In the absence of conditioning factors for the determination of a uF value, I assume that a redundancy rule applies, which copies the value of an iF to the uF “slot” in the syntax at Transfer, if both value types are represented on the same node (cf. Wechsler and Zlatić 2003, 50 on a similar representational relation between concord and index). This is illustrated for number feature values in (51). (See also Adamson and Anagnostopoulou to appear and Adamson and Anagnostopoulou 2024 on this process for gender.)

-

(51)

In this system, “semantic agreement” is agreement for iFs. A striking property of semantic agreement is that it is restricted in where it may apply. Semantic agreement asymmetries are found in various domains; Smith (2015, 2017, 2021) offers (among others) the example of verbal agreement with committee nouns in British English. Drawing on observations from the literature (e.g. Elbourne 1999; Huddleston and Pullum 2002), Smith shows that in various types of expressions, such nouns, while being grammatically singular, can occur with plural T agreement when the nominal c-commands T (52a) but not when the opposite c-command relation holds (52b).

-

(52)

A comparable asymmetry has been identified for agreement in the verbal domain with coordinated nominals. Smith (2021) and others have pointed out that English coordinated subjects trigger resolved plural agreement when the subject c-commands T, but trigger closest conjunct agreement in existential constructions (53b), where the T probe appears to c-command the &P.Footnote 10 The former can be characterized as semantic agreement with a resolved plural value, while in the latter case, Smith’s claim is that semantic values at the coordinate level are not available; the probe instead agrees with the formal features of the highest (first) conjunct. See Munn (1999) for discussion of a related asymmetry for verbal agreement with SVO versus VSO orders in Arabic.

-

(53)

The same asymmetry is observed with SpliC expressions in Italian. Thus while postnominal SpliC adjectives can exhibit the resolved pattern (54), prenominal SpliC adjectives cannot (55). This is the same direction of structural asymmetry as in the abovementioned examples, with “semantic agreement” being disallowed when the aP probe c-commands the nP.

-

(54)

-

(55)

That there is a structural unity between prenominal and postnominal SpliC expressions is supported by a semantic restriction shared by the two. As I discuss in detail in Sect. 4, postnominal SpliC adjectives are restricted; they cannot be gradable, quality adjectives, as in (56). The same holds for prenominal SpliC adjectives: it is ungrammatical for quality adjectives to participate in SpliC expressions, as in (57).

-

(56)

-

(57)

I return to this point in Sect. 4. For now, the relevant point is that both postnominal and prenominal adjectives participate in SpliC expressions, yet there is an agreement asymmetry, such that only the former can have the resolved pattern.

Following Smith (2015, 2017, 2021), I adopt the view that semantic agreement—agreement with iFs—is confined to structures in which a certain c-command relation holds between probe and goal: I presently treat this as a relation in which the probe does not c-command the goal. (The mechanics are discussed further below.) Under this view, semantic agreement is not expected to be possible with prenominal adjectives, as an aP (the probe) would c-command an nP (the goal). In contrast, semantic agreement with postnominal adjectives should be possible, as the probe will not c-command the goal. (The relationship between semantic agreement and resolution is clarified below.) Our prenominal-postnominal asymmetry is thus as in (58a), where semantic agreement involves interpretable features (iFs), to be explained below.

-

(58)

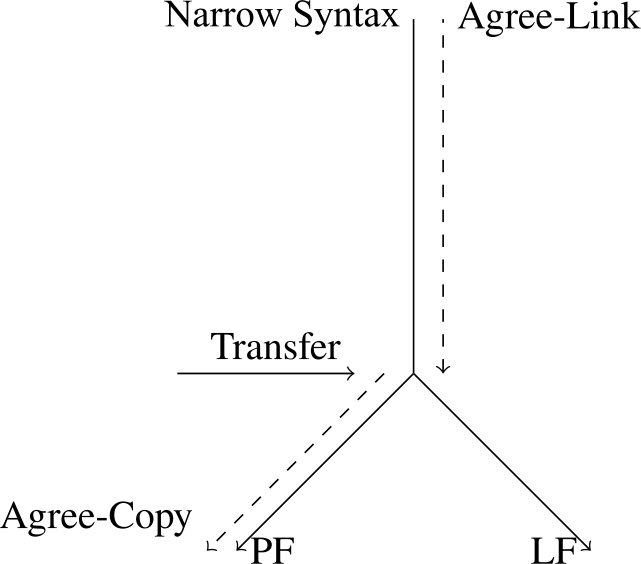

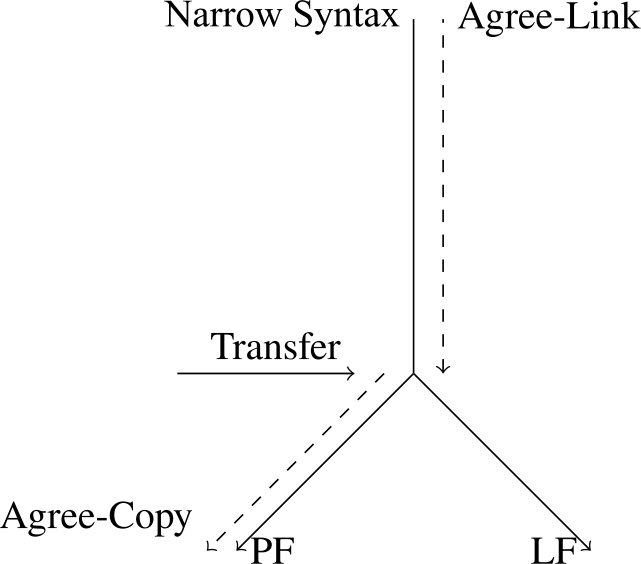

Why is semantic agreement configurationally constrained? I follow Smith in taking this to be an issue of the modularity of agreement relations. I adopt the view that agreement operations are distributed between the narrow syntax and the postsyntax (Arregi and Nevins 2012; Bonet et al. 2015; Smith 2015, 2017, 2021; Adamson and Anagnostopoulou to appear; Adamson and Anagnostopoulou 2024; among others). This view has been fruitfully applied in the area of agreement with coordinate structures, for example with closest conjunct agreement; see especially Benmamoun et al. (2009), Bhatt and Walkow (2013), Marušič et al. (2015), Smith (2021). Following Arregi and Nevins as well as Smith, I adopt the distinction between Agree-Link, which establishes an Agree relation between a probe and a goal in a c-command relationship (59a), and Agree-Copy, which copies the feature values from the probe to the goal (59b). I also adopt Smith’s view that Agree-Copy may happen at the point of Transfer, but that this is limited to a particular configuration, as stated in (59bi). This condition restricts the distribution of semantic agreement, as I elucidate below.Footnote 11 The basic model is sketched in (60).

-

(59)

-

(60)

The c-command condition on Agree-Copy will restrict its derivational timing: if the probe c-commands the goal, Agree-Copy can only occur along the PF branch. If the probe does not c-command the goal, then Agree-Copy may occur at Transfer. This will allow us to capture the agreement asymmetry observed for prenominal and postnominal SpliC adjectives, as I show below.

An appeal to the modularity of agreement is not unique to Arregi and Nevins (2012) and Smith (2021); see for example Bonet et al. (2015) on agreement asymmetries and modularity, and Choi and Harley (2019) for a recent implementation of postsyntactic agreement under c-command. An appeal to this type of structural condition on agreement also bears affinities with a line of work that identifies spec-head agreement as a relevant variable for agreement asymmetries in the verbal domain (e.g. Chung 1998; Munn 1999; Guasti and Rizzi 2002; Samek-Lodovici 2002; Franck et al. 2006) as well as prenominal-postnominal asymmetries in the nominal domain (e.g. Shlonsky 2004; Koopman 2006; Nevins 2011; Bonet 2013; Bonet et al. 2015)—though instead of spec-head agreement, my condition requires less strictly that the probe not be c-commanded by the goal. (See relatedly the idea from Bjorkman and Zeijlstra 2019 that looking “up” results in more “robust” agreement than the configuration in which the probe c-commands the goal.) The c-command condition also bears a strong affinity with previous distinctions in the literature between spec-head agreement and agreement under government: Munn (1999) invokes this difference to capture asymmetries with coordinated subjects in Arabic (on which, see also Aoun et al. 1994 and others), as well as other phenomena, including conjunct agreement patterns in Brazilian Portuguese.

To reiterate, for me, semantic agreement is agreement for interpretable features. As mentioned above, agreement is distributed, with Agree-Link established in the narrow syntax and Agree-Copy either at Transfer or in the postsyntax. While iF and uF values are present in the narrow syntax, these values split at Transfer, with iFs sent to the LF interface and uFs sent to the PF interface. Because uFs and iFs are sent to different interfaces at the point of Transfer, semantic agreement can only happen if Agree-Copy occurs at Transfer.

I assume further with Smith (2021) that semantic agreement is not available for all iFs, but rather with a specific set of iFs that are syntactically active. Thus committee nouns in British English have active iFs, even if the same iF is not active in other varieties.Footnote 12 Relevant for my purposes with SpliC expressions is that all nodes with multiple feature sets can be active in Italian.

I am now in a position to couch my hypothesis from (22)/ (47) in terms related to my adopted theory of agreement more generally.Footnote 13

-

(61)

Semantic Agreement Hypothesis (final version): Agree-Copy with active iFs (“semantic agreement”) can only occur when the probe does not c-command the goal at Transfer.

As a sample illustration of how agreement operates, consider la nazione bulgara ‘the Bulgarian nation,’ a tree for which is repeated in (62).

-

(62)

At the point when the nP merges in its base position, I assume it bears valued gender and number features: in particular, it bears u[f] and i[sg].

When a enters the derivation, it merges bearing unvalued gender and number features and therefore probes. It does not identify any suitable goal, as it has not merged yet with any constituent that bears the relevant features. I assume, however, that aPs can probe from their maximal projections. Probing from maximal projections has been argued for by Clem (2022) and others and is often implicitly assumed for adjectival agreement (see e.g. Landau 2016b). When aP merges as a specifier of an FP, it probes and finds the valued features of the nP goal, establishing an Agree-Link connection. Subsequently, the nP moves.

D also bears unvalued gender and number features in the syntax and therefore probes, establishing an Agree-Link relation with the nP, which bears valued gender and number features.

At Transfer, because of movement, the higher nP c-commands the aP and not the other way around—and the two are therefore eligible to participate in Agree-Copy either at the point of Transfer or in the postsyntax; I assume both are possible options in the grammar. Deriving postsyntactic Agree-Copy, the i[pl] value of number at Transfer will first be copied to the corresponding uF slot, per (51), and this u[pl] is sent to PF. As a result of Agree-Copy in the postsyntax, the aP comes to bear valued u[f] and u[pl] features, which it realizes as inflection on the adjective (see e.g. Adamson 2019 on postsyntactic insertion of inflectional morphology on adjectives).

Because D c-commands the nP, Agree-Copy is restricted: it can only happen in the postsyntax, along the PF branch, after Transfer. As a result of Agree-Copy, D comes to bear the same uF values of the nP. Presently, the configurational difference, and correspondingly the difference for the timing of Agree-Copy, has no substantial impact on which features end up on aP versus D. However, the timing difference will impact our SpliC expressions, which I direct my attention to shortly.

To summarize so far: the agreement patterns of SpliC expressions are analyzed with three key components: (i) multidominant structure, whereby shared phrases carry multiple features of the same feature type; (ii) resolution of these features in the context of semantic agreement; and (iii) structural conditions on the distribution of semantic agreement. We are now in a position to show how this derives various patterns in SpliC expressions.

3.3 Deriving agreement patterns and the prenominal-postnominal asymmetry

With these pieces in place, I now proceed to show how the dual feature system derives the correct results. In this subsection, I demonstrate how the account captures the prenominal-postnominal asymmetry in the marking of the noun. I then show how the account further (i) derives the number facts for prenominal elements such as D; (ii) predicts an asymmetry in the allowance of feature mismatches between the adjectives; and (iii) extends to a combination of nouns in split coordination.

3.3.1 Number and gender marking on post- and prenominal SpliC adjectives

In the case of SpliC adjectives, the “resolving” features on the nP are interpretable, so semantic agreement with postnominal adjectives, as in (63a), is with these iF values. In the syntax, the aP probes and establishes an Agree-Link connection with the nP, and the nP moves to the specifier position of the higher FP (63b). Because the aP does not c-command the higher nP, interpretable features on the nP are visible.

-

(63)

For the example in (63), the nP bears two [sg] iFs in the syntax. Because the probe does not c-command the goal and the iFs are active, the i[sg] values can be copied from the nP to each aP at Transfer. Resolution is triggered by this process, resolving the two i[sg] features on nP to i[pl]. This feature is copied to the uF slot on nP via the redundancy rule, and this uF comes to be expressed as plural marking on the noun. (The adjectives will each bear i[sg] received through Agree-Copy at Transfer, which is copied to their uF slots as u[sg].)Footnote 14 (64) depicts the states of the number feature values on nP, starting with a set of interpretable values, which come to be resolved as plural, which is subsequently copied to the uF slot. The first representation shows what is present in the narrow syntax on the nP; the second shows the resolved number value following resolution at Transfer; and the third shows what happens at Transfer before the number feature representation is shipped to the PF and LF branches.

-

(64)

The gender of nazione is uninterpretable and feminine. Because of the multidominant structure, two u[f] features are present on the nP. Agree-Copy occurs at Transfer, but the gender uF values match; therefore uF agreement for gender occurs. Realization is consequently feminine for each adjective and on the noun.

-

(65)

A reviewer wonders (i) how interpretable features are interpreted on adjectives, and (ii) how agreement for each adjective targets the correct features on the shared node; I briefly discuss suggestions about each in turn. Regarding (i), there are several possibilities. One is that the adjectives themselves have noun-like semantics (e.g. Fábregas 2007), and these interpretable features compose with these adjectives in the way they would with other nouns. Alternatively, I note that other researchers have also suggested that nominal features can be interpreted on adjectives—see Sudo and Spathas (2020) for one recent implementation that includes gender presuppositions for determiners and adjectives. (See also discussion of LF interpretation in multidominant structures in Belk et al. 2022.) For (ii), there are also a few possibilities. One is that Agree-Copy can freely choose whichever features to copy from the shared node to the probe, given that they are structurally equidistant from each other; however, because the iF is also interpreted on the adjective relative to some index (e.g. 8 or 13), the choice of copying has some interpretive import. Thus there will be an alignment between the set of features that are copied and the adjectival semantics corresponding to that particular partition of the nominal reference.

For prenominal adjectives (66a), the nP does not move and therefore the aP c-commands the nP at Transfer. Consequently, Agree-Copy happens in the postsyntax; because interpretable features are sent to PF and not LF at the point of Transfer, Agree-Copy can only refer to uFs (66b).

-

(66)

For (66), the nP bears two i[sg] features in the syntax. Agree-Link is established between each aP and the nP. Because the conditions are not met for Agree-Copy at Transfer, it occurs in the postsyntax, and resolution is not triggered. Both i[sg] features are copied to the uF slot, and come to be expressed as singular on the noun (see Shen 2019, 23 for this same type of analysis for nominal RNR, and relatedly Shen and Smith 2019 for “morphological agreement” in verbal RNR). (Each aP will bear the multiple u[sg] features copied from the nP.) (67) depicts the derivational stages for the number features of the nP, first in the narrow syntax and then at Transfer.

-

(67)

As with gender matching as described above, the situation of having two of the same feature value for number results in a single realization at PF, this time for singular number.

As an anonymous reviewer points out, the account predicts that prenominal SpliC adjectives that are marked plural should be incompatible with a singular interpretation. This is indeed borne out:

-

(68)

3.3.2 Agreement on other nominal elements

The current system also makes correct predictions for other agreement targets in the nominal domain.

For plural nouns with singular postnominal SpliC adjectives, Agree-Link is also established between elements higher in the nominal domain and the nP. For prenominal material such as determiners, possessive pronouns, and adjectives, the c-command condition is not met for Agree-Copy at Transfer. Therefore, each of these elements is predicted to agree with the uF values of nP. Because resolution is triggered for Agree-Link at Transfer with a postnominal adjective, the nP comes to bear i[pl] in the syntax. The i[pl] value is subsequently copied to the uF slot before the PF branch. Therefore, postsyntactic agreement with higher agreement targets is expected to be for u[pl]. This is borne out:

-

(69)

In contrast, prenominal SpliC adjectives require singular marking on the head noun, reflecting the fact that no semantic agreement has taken place. Since resolution is not triggered, the uF value is singular, and therefore, higher elements should express singular features. This is borne out:

-

(70)

The same holds for nonresolving SpliC postnominal expressions; see (71), with the singular-marked option repeated from (42). (I discuss this context further below.)

-

(71)

3.3.3 Predicted asymmetry: Conjunct mismatch

The dual feature analysis captures an asymmetry in conjunct mismatch effects. As discussed in Sect. 2, postnominal SpliC adjectives can mismatch by either number features, as in (72), or gender features, as in (73) (repeated from (44) and (45), respectively). This is correctly predicted by the current account: agreement can copy independent iFs from the nP, and feature mismatches can be resolved on the nP.Footnote 15

-

(72)

-

(73)

For prenominal adjectives, the prediction is that resolution is unavailable, because it cannot be triggered by Agree-Copy with iFs, as the c-command condition is not satisfied. Consequently, mismatched iFs should be copied as mismatched uFs. The uFs on the nP will conflict, which results in ineffability at the point of exponence. Thus neither number nor gender mismatch should be tolerated with prenominal SpliC adjectives. This is borne out:

-

(74)

-

(75)

A further prediction concerns postnominal SpliC adjectives. As with prenominal adjectives, it is possible for postnominal SpliC adjectives to occur with a singular-marked noun, with the interpretation that there are two individual entities total (76). This reflects a lack of semantic agreement. This is expected if Agree-Copy can occur in the postsyntax, as it is not mandatory for it to take place at Transfer even when the c-command condition is met.

-

(76)

For (76), two i[sg] values bearing different indices appear on the nP in the narrow syntax. Each aP enters into an Agree-Link relation with the nP. Because the aPs do not c-command the nP following its movement, Agree-Copy can occur either at Transfer or in the postsyntax. If it happens in the postsyntax, then at Transfer, the iFs will become uFs via the redundancy rule, with two u[sg] features. Agree-Copy will thus copy the u[sg] features on the nP to each aP, and the aPs and the nP will all come to bear singular inflection.

If this is the correct characterization of singular nouns in SpliC expressions, we make a further prediction for conjunct mismatch. Recall that plural nouns permit number-mismatched postnominal adjectives (77a), consistent with the semantic agreement analysis. In contrast, when no semantic agreement takes place, the noun copies multiple iFs to the uF slot via the redundancy rule, as with prenominal SpliC adjectives. We therefore predict that it should not be possible for the noun to be marked singular if there is mismatch between the two conjuncts: if there is no semantic agreement, then the result should be conflicting number features on nP, forcing a PF crash. And if there is semantic agreement, then resolution should be triggered, causing the number marking to be plural. It should therefore be impossible to have number mismatch between the conjuncts when the noun is singular-marked. This is borne out (77b). (Note that (77b) also speaks against a closest conjunct agreement analysis of the phenomenon.)

-

(77)

Similarly, we predict gender mismatch to be ungrammatical with singular nouns modified by SpliC adjectives. This is also borne out: while plural nouns permit conjunct mismatch for gender (78a), singular nouns are not compatible with gender mismatch (78b).Footnote 16

-

(78)

3.3.4 Predicted asymmetry: SpliC nouns

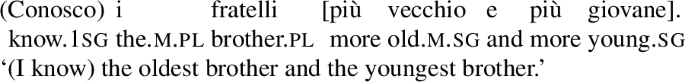

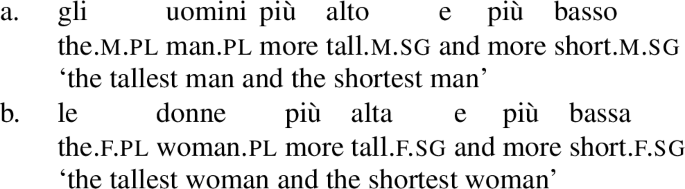

Under the current approach, summative resolution in multidominant structure is treated the same way as coordination resolution. More concretely, suppose that valued iFs of every conjunct project to &P, leading to multiple iFs on &P. As with summative agreement, resolution is only triggered in response to Agree-Copy for iFs. This leads to a prediction: the same prenominal-postnominal asymmetry should be found in Italian with SpliC nPs modified by an adjective. In particular, a postnominal aP that occurs with two singular SpliC nPs should be able to agree with a resolved plural value. Conversely, a prenominal adjective that modifies two singular SpliC nPs should not be able to agree in the plural.

Cinque (2010, 88–90) observes the relevant asymmetry. Prenominal adjectives modifying coordinated singular nouns exhibit a restriction analogous to the one discussed for SpliC adjectives. Agreement must be singular for prenominal adjectives, but can be plural for postnominal adjectives:

-

(79)

-

(80)

For the postnominal derivation, the &nP moves to the specifier of a higher FP, and therefore, the iFs of &nP are visible to aP; this is represented in (81). &nP has two values of i[sg], which are both copied to the aP. Because iF agreement triggers resolution, the result is that aP comes to bear i[pl]. This value provides a u[pl] value via the redundancy rule, which is realized with plural marking on the adjective.

-

(81)

In contrast, when the prenominal adjective modifies two SpliC nouns, the aP still c-commands the &nP. Therefore, agreement is for uFs only (82a). Because Agree-Copy does not occur with iFs, resolution is not triggered. The &nP copies its set of iFs to its uF slot (82b), and it is this set that Agree-Copy sees in the postsyntax for the aP, resulting in singular inflection on the adjective.

-

(82)

It is striking that there is a prenominal-postnominal asymmetry for both SpliC adjectives and for SpliC nouns: in general, the pattern is that two singular SpliC conjuncts occur with a plural element only when the adjectives are postnominal. This is represented schematically in Table 1. The generality of the pattern suggests the two arise from the same mechanisms, as proposed here.

3.4 Section summary

To summarize this section, summative agreement in SpliC expressions resembles summative agreement observed for other phenomena in Italian that have also been claimed to be multidominant, namely verbal RNR and adjectival hydras. The resolution analysis of summative agreement comes from an extension of Grosz’s (2015) treatment of verbal RNR, permitting resolution not just on probes but also on goals. The analysis of agreement is framed within a dual feature system and restricts semantic agreement (and resolution) to a configuration in which the probe does not c-command the goal. This makes correct predictions for prenominal-postnominal asymmetries for SpliC adjectives with respect to number marking of the noun, the availability of conjunct mismatch (for both gender and number), and the number inflection of other nominal elements; it also makes correct predictions for prenominal-postnominal asymmetries for adjective agreement with SpliC nouns.

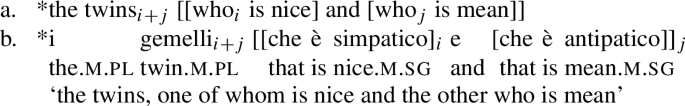

Some reviewers express concern regarding overgeneration. In particular, they worry that expressions like *the childreni+j walksi and singsj and *the twinsi+j is talli and is shortj are incorrectly predicted to be grammatical, given that (38) licenses the presence of multiple features on a shared phrase. As I discuss in Sect. 4, there are in fact restrictions on which adjectives participate in SpliC expressions. Similarly, I tentatively suggest that, while multidominant structures are permitted in clausal syntax, split reference is not necessarily licensed in these configurations. I submit that this is a counterpart to Grosz’s observation that in verbal RNR, while verbal summative resolution is possible, cumulative reference is not; for example, one cannot say *Sue’s proud that Johni and Mary’s glad that Billj have finally meti+j (Grosz 2015, 15). I do not currently understand the full set of constraints on multidominant SpliC expressions, and leave the resolution of this issue to future research.

Having laid out the current analysis and what it captures, in the next section, I turn to alternative approaches to SpliC expressions and show that they face empirical challenges.

4 Critical assessment of alternative approaches

In this section, I consider alternative analyses to SpliC expressions and show how they encounter difficulties. I first (Sect. 4.1) consider a relative clause derivation along with a related analysis from Bosque (2006). I then consider two alternatives that have been entertained for similar constructions in Bulgarian: one involving “direct” coordination (Arregi and Nevins 2013) (Sect. 4.2) and one involving ellipsis (Sect. 4.3). Lastly, I consider at length an across-the-board (ATB) movement alternative proposed by Harizanov and Gribanova (2015) for Bulgarian and discuss how it does not capture the Italian data (Sect. 4.4).

4.1 Against the relative clause analysis

Consider again one of the chief agreement patterns of interest, where a plural noun occurs with singular SpliC adjectives. An alternative analysis to entertain is one where the adjectives are each in a separate (reduced) relative clause, and agree with a null, singular relative pronoun; accordingly, each relative clause is a modifier of a single referent. This type of analysis is sketched in (83).

-

(83)

There are two reasons to reject such an analysis: (i) split relativization is in fact never possible in the language, and (ii) the adjectives that participate in SpliC expressions are in fact restricted to relational adjectives, which cannot (always) be derived via a relative clause source. I address each point in turn.

The phenomenon of split antecedent relativization is known, where two coordinated (possibly singular) nominals can share one relative clause (see e.g. Link 1984; Grosz 2015; Bobaljik 2017):

-

(84)

the womani and manj [whoi+j are married to each other]

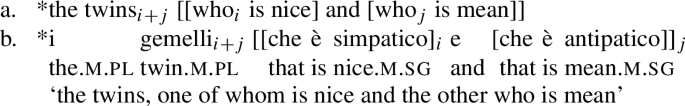

In the imaginable counterpart “split relativization,” the reference of a plural noun is split between two coordinated relative clauses. However, relativization is altogether impossible with coordinated, unreduced singular-referring relative clauses. This is true both in English (85a) and in Italian (85b) for two singular-modifying relative clauses.

-

(85)

The intended meanings of (85a) and (85b) instead only come across in nominal appositive constructions (86), which require an intonational break after the noun and occur with definite articles for each conjunct.

-

(86)

Given that split relativization is not an option for full relative clauses, we have no reason to suspect that the option should exist for reduced relatives. This suggests that SpliC adjectives are not in fact derived through split relativization. In terms of the agreement features, this indicates that singular features on SpliC adjectives come from agreement with nP, not with relative pronouns.

The second point concerns the relational status of SpliC adjectives. Consider, for example, the gradable, quality adjectives in (87) (repeated from (56)), which cannot be split-coordinated.

-

(87)

Bosque (2006) suggests that in Spanish (also Romance), SpliC adjectives must be relational, in the sense of Bosque and Picallo (1996) and others. As Morzycki (2016, 49) puts it, relational adjectives are subsective but not obviously intersective: for example, a legal conflict is a type of conflict, but something that is a legal conflict is not clearly both legal and a conflict. These adjectives have been described as having a classificatory function and as being nongradable (e.g. McNally and Boleda 2004), in contrast with quality adjectives like tall.

Bosque’s characterization of Spanish SpliC adjectives is largely in line with the Italian data, as well. Postnominal SpliC adjectives can be, among other types, locational (88), “ethnic” (89), ordinal (90), or “classifying” (in a broad sense) (91). They can be restrictive in their interpretation, as is clearest from (92). For all these cases in (88)–(92), the adjectives are nongradable and cannot be coordinated with quality adjectives, in line with the “relational” characterization.Footnote 17 Recall from the data in (56) and (57) that SpliC expressions cannot be composed using quality adjectives.

-

(88)

-

(89)

-

(90)

-

(91)

-

(92)

Further support for the relational requirement of SpliC adjectives comes from contrasting different uses of “the same” adjectives in SpliC expressions; see related discussion of Spanish in Bosque (2006, 58). The ability to appear in SpliC expressions varies depending on whether the adjectives are relational or quality adjectives: for example, while color adjectives can be relational (see (91)), such as when they serve to restrict reference to a subtype of flora or fauna, they can also serve as quality adjectives. Only the former type works in SpliC expressions, as illustrated in (93) and (94). (Thanks to Stanislao Zompì, p.c., for discussion.)

-

(93)

-

(94)

The requirement that SpliC adjectives be relational rules out a relative clause derivation whereby each SpliC adjective is predicated of a null relative pronoun. The reason is that the interpretation of the predicative meaning of the adjective is often not the same as the relational meaning. For example, national adjectives like italiano ‘Italian’ or iraniano ‘Iranian’ can be used relationally (see McNally and Boleda 2004; Alexiadou et al. 2007; Alexiadou and Stavrou 2011; Arsenijević et al. 2014), and their relational use can be split-coordinated (95). But the relational interpretation lacks a corresponding predicative use (96).Footnote 18

-

(95)

-

(96)

A proposal similar to the relative clause analysis is Bosque’s (2006) account of postnominal SpliC adjectives in Spanish, an example of which is in (97).

-

(97)

Bosque’s account of data like (97) involves a complex derivation in which: (i) D (realized as los) takes a small clause PredP complement; (ii) the PredP subject is &P; (iii) each coordinated DP has a predicative structure whereby a pro subject with number features (and presumably gender features) occurs with a predicative “C/P” (prepositional complementizer) complement, where the complement is the relational adjective (mexicano, argentino); and (iv) the PredP predicate is the nP (embajadores), which raises to the specifier of the PredP. A tree with these details is provided in (98). The relational adjectives each agree in number (and presumably gender) with their respective pro subjects, and the nP acquires plural marking through agreement with the coordinate phrase.

-

(98)

(Bosque 2006, 54)

(Bosque 2006, 54)

I see at least three problems with this account. First, the nonpronunciation of the Ds in each conjunct has to be stipulated, as there is no evidence for the embedded determiners. Second, the account does not actually restrict SpliC adjectives to being relational; why could it not be a PredP with predicative adjectives in each conjunct? Third, it is not clear that the account can capture SpliC expressions where there is singular marking on the noun, which were discussed in detail in Sect. 3.Footnote 19

Both the split relativization facts and the relational facts speak against a relative clause analysis of SpliC expressions. To be clear, however, the relational requirement for SpliC adjectives is not immediately accounted for by what I have proposed above. I speculate that relational adjectives’ ability to participate in SpliC expressions is related to their noun-like status (on which, see Fábregas 2007; Marchis 2010; Moreno 2015; and references therein). As Fábregas (2007) notes, relational adjectives are frequently built morphologically on nouns; they seem semantically equivalent to a noun modifying another noun (compare cellular structure and cell structure); and unlike quality adjectives, they can be modified by numeral prefixes like poly- (or poli- in Italian). Fábregas analyzes relational adjectives effectively as nouns combined with a defective adjectivizing head. However, because they inflect like adjectives and can bear adjectivizing suffixes (e.g. -ivo for legislativo ‘legislative’ in (5)), I assume they are indeed adjectives. Nevertheless, I assume their noun-like status permits them—but not other modifiers—to host interpretable nominal featuresFootnote 20 and to allow them to modify independent partitions of the nominal reference. I assume that there is an adjectivizing head an (n for “noun”) that bears the relevant properties, though I will not spell this out more explicitly.

4.2 Against the direct coordination analysis

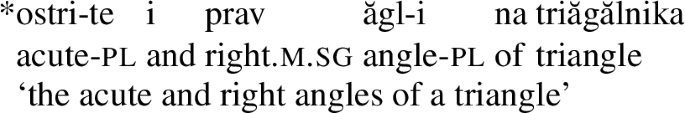

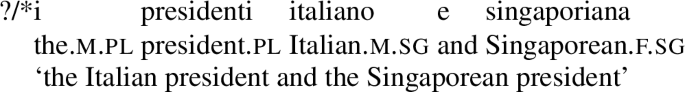

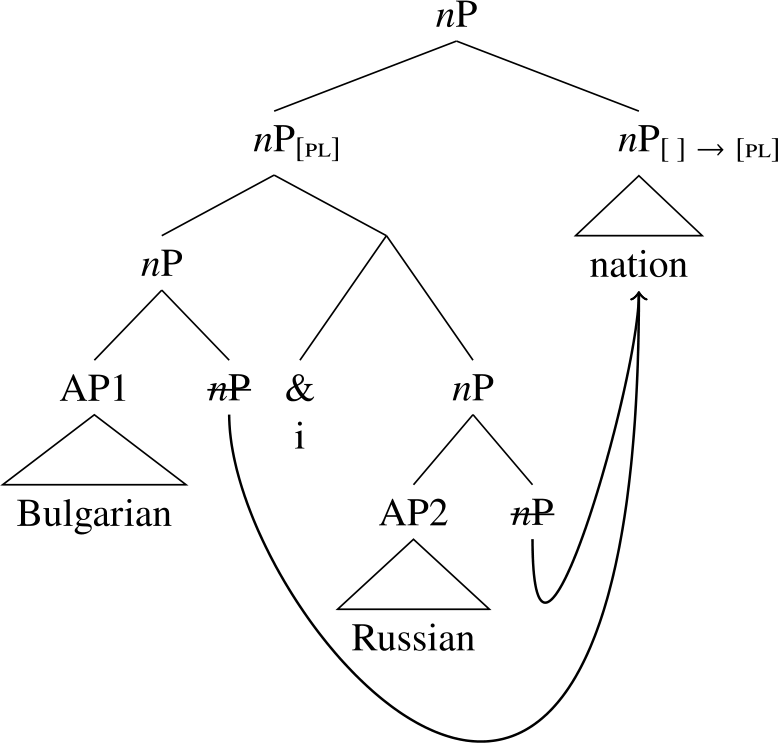

Another alternative to consider coordinates aPs rather than larger structures; this has been proposed for Bulgarian for similar expressions. Bulgarian, like Italian, allows a plural noun to be modified by two singular adjectives (Arregi and Nevins 2013; Harizanov and Gribanova 2015; Gribanova 2017):

-

(99)

Arregi and Nevins (2013) propose to derive these expressions by coordinating the modifiers directly, as in (100). (They assume aPs are adjoined to nP, and that the definite suffix lowers in the postsyntax.)

-

(100)

Harizanov and Gribanova (2015) argue against Arregi and Nevins’s analysis of Bulgarian on the basis of several pieces of evidence; most of their arguments apply specifically to the agreement mechanisms of Arregi and Nevins’s account, rather than the coordinate structure itself.Footnote 21 The exception comes from adjective stacking in each conjunct, which is not expected from direct coordination (100), because stacked adjectives do not form their own constituents to the exclusion of the noun they modify. In contrast, adjective stacking is expected to be possible under the multidominant account (see (18)). Adjective stacking in each conjunct is allowed in Bulgarian (Harizanov and Gribanova 2015), as illustrated by (101)—a tree of which is provided in (102)—and in Italian ((17), a fragment of which is repeated in (103)). (The lack of reported degradation for Bulgarian is consistent with the earlier suggestion in Sect. 2 that the Italian expressions are degraded to due to multiple sharing. For Bulgarian, only the nP needs to be shared in stacking examples, since there is no roll-up movement.)

-

(101)

-

(102)

-

(103)

Stacking, while permitted in the multidominant analysis, is not expected under a direct coordination analysis.

I note that there is an issue with extending my account of agreement to the Bulgarian data. For my account of Italian, I argued that resolution can only happen in the context of semantic agreement, and that this form of agreement is not permitted when aP c-commands nP. However, as evident from (102), keeping the assumptions of my account constant for Bulgarian, the aPs c-command the nP, whose plural value would come from resolution, contrary to what we expect to be possible. I tentatively suggest that in Bulgarian, resolution can happen without semantic agreement; I discuss this further in Sect. 6.

4.3 Against the elliptical analysis

The next alternative to consider involves ellipsis of the second nP. The elliptical analysis can be rejected on the basis that it does not derive the correct combination of morphological and interpretive properties; see Harizanov and Gribanova’s (2015) rejection of this analysis for Bulgarian.

Evidence against the elliptical analysis comes from (104), which lists the patterns of inflection and interpretation of number expected for an elliptical derivation, keeping constant the number agreement of the second adjective with the elided noun. These derivable ellipsis patterns, not all of which are even grammatical, all contrast with the central pattern of interest in (105).

-

(104)

-

(105)

The argument presented here applies specifically to when the marking of the head noun is plural rather than singular; an elliptical derivation is conceivable for other expressions with singular nouns, though it is not clear how an elliptical account could derive the prenominal-postnominal asymmetry.

4.4 Against an ATB analysis

The analysis for Bulgarian pursued by Harizanov and Gribanova (2015) takes SpliC expressions to be derived as follows: (i) two nPs are conjoined, each of which include separate adjoined aPs, (ii) segments of nP are ATB-moved, right-adjoining to the coordinate structure, and (iii) the moved nP receives a plural concord feature from the resolved plural value of the coordinated phrase (106).

-

(106)

ATB movement accounts have been criticized for node raising constructions in the verbal domain on various grounds. For example, such constructions are insensitive to islands, contrary to what is expected under a movement analysis, and secondly, these accounts are unable to account for so-called internal readings; see Belk et al. (2022) for extensive discussion of both issues in the context of verbal RNR and for further references. It is difficult to construct a relevant example for the former point in my nP case, so I instead turn to the latter.

Consider a modifier like giunto ‘joined,’ which, for two hands, can refer to a relation where they are pressed together, for example in a prayer context (107). Crucially, this internal reading in which the hands are joined with each other occurs in the plural; it is not possible to describe each hand independently as being joined, as in (108) (compare in English my folded hands vs. #my left folded hand and my right folded hand).

-

(107)

-

(108)

Consider a SpliC expression like my left and right folded hands and the parallel Italian example in (109) (which is more natural with a pause between the shared adjective and the SpliC adjectives, as in English). For an ATB analysis of SpliC expressions, the shared phrase would be generated in independent conjuncts, and would be moved out from each conjunct across the board. For a modifier like giunto, in a shared phrase, we should expect an effect like that seen in (108), as joined hand would be generated in each conjunct. In contrast, a multidominant analysis treats SpliC expressions as having a shared plural nP, and the example should therefore be felicitous. The prediction of the multidominant analysis is borne out. (See Belk et al. 2022 for more detailed discussion of internal readings in node raising expressions.) A structure for (109) would be parallel to that of the example (13b) in Sect. 2, with the adjective giunte ‘joined’ being internal to the shared constituent.

-

(109)

A reviewer asks whether we could treat singular-marked SpliC nouns with postnominal adjectives (e.g. (76)) as involving ATB movement. As (110) shows, even with a singular-marked noun, the internal reading is available, which speaks against an ATB analysis.

-

(110)

Another issue with the ATB account for Italian concerns adjective stacking. The example in (17) is repeated in (111).

-

(111)

It is not apparent that an ATB account with roll-up movement can derive stacking, as it would require subextraction from a moved constituent, a “freezing” configuration widely viewed as impossible (on freezing, see Corver 2017 and references therein).Footnote 22 See the derivation in (112): in each case, two FPs are coordinated, each of which dominate two aP specifiers and an nP (the one that is ATB-moved out of each conjunct). The nP moves to a specifier position above the lower aP within each conjunct, and then the FP dominating both the nP and the lower aP move up to the specifier position of each conjoined FP. However, in order to receive plural marking under the ATB analysis and to be pronounced in the higher position, the identical nPs must be ATB-extracted from each conjunct, requiring subextraction from the FP. It is thus unexpected under the ATB account that stacking should be permitted in Italian, while it is expected under the multidominant account.

-

(112)

In addition to the above-raised points, there are also differences between the Bulgarian data and the Italian data. This suggests that the ATB analysis that Harizanov and Gribanova (2015) offer for Bulgarian cannot readily be adapted for Italian.

The first point concerns mismatches between the conjuncts: as Harizanov and Gribanova claim, because ATB movement requires identity of the extracted constituents, they predict that number mismatch between the conjuncts should be ungrammatical. (Harizanov and Gribanova assume number features are present on n.) The examples in (113) and (114) are adapted from their Bulgarian data and were confirmed by a consultant. To this, I also add the more plausibly number-mismatched coordination in (115), which is also ungrammatical.

-

(113)

-

(114)

-

(115)

As discussed earlier, while marked (with varying levels of degradation), Italian examples are accepted by my consultants for number mismatch (116). Recall from Sect. 3.3.3 that the mismatch pattern is expected under the semantic agreement analysis with multidominant structure.

-

(116)

A related prediction not tested by Harizanov and Gribanova is that, because of the identity condition on ATB movement, gender mismatch should also be ungrammatical. This prediction is indeed borne out for Bulgarian. For example, the noun prezident ‘president’ (117a) has a feminized counterpart (117b), and the masculine plural can refer to a mixed gender group (117c). However, it is not possible for gender-mismatched SpliC adjectives to modify the masculine plural noun (118).

-

(117)

-

(118)

For comparison with Italian, I maintain Harizanov and Gribanova’s assumption that n is the locus of number features. I also assume that gender is also on n; see Kramer (2015), Adamson and Šereikaitė (2019); among many others. For at least some speakers of Italian, gender mismatch is possible, as (119) shows.

-

(119)

The ability to have number- or gender-mismatched conjuncts is expected under the multidominant approach, which lacks the matching condition of the nonmultidominant ATB approach; in both cases, mismatch is expected to be possible for semantic agreement.

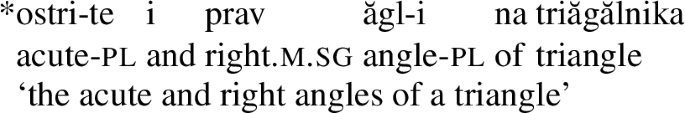

Lastly, Harizanov and Gribanova’s account also claims to capture for Bulgarian that morphologically irregular plurals (both suppletive and those that could be described as having irregular morphophonology), such as hora ‘people’ (singular čovek) and oči ‘eye’ (singular oko), are ungrammatical with singular SpliC adjectives (120). (See Gribanova 2017 for a modified analysis incorporating a combination of ATB movement and multidominant sharing of a root.)

-

(120)

For Harizanov and Gribanova, the idea is that the singular form of the root appears in each conjunct, and is lexically inserted early in the derivation. When the nP moves out of each conjunct and the moved constituent receives a plural feature via concord, a morphological conflict is produced in which the root cannot combine in the context of the plural. Harizanov and Gribanova’s analysis crucially relies on the view that roots are inserted early, which is highly controversial (see critical discussion in Harley 2014), and it also requires that even irregular morphophonology is treated as suppletive. Without these assumptions, the ATB analysis does not readily explain the facts about irregular plurals in Bulgarian.

Holding Harizanov and Gribanova’s (2015) assumptions constant for the sake of comparison, we can ask whether this analysis can be applied to Italian. There are morphologically irregular plurals in Italian such as uomini ‘men,’ an irregular plural of uomo, and templi ‘temples,’ an irregular plural of tempio. Unlike Bulgarian, Italian allows irregular plurals to occur with singular SpliC adjectives, as (121) and (122) show (there is no contrast with comparable regular nouns (121b)).

-

(121)

-

(122)

As a reviewer rightly points out, if roots are not inserted early, or if irregular morphophonology is not treated as suppletion in Italian, then no issue arises with an ATB analysis. That being said, Harizanov and Gribanova suggest that their ATB account captures the irregular plural data in Bulgarian, but it is really the (questionable) assumption about early root insertion that is critical for their account, and in any case, their account does not extend to the Italian data.Footnote 23

Before I move on, I note that Harizanov and Gribanova (2015) show that pluralia tantum nouns in Bulgarian are only compatible with plural-marked adjectives (123). This is actually also true in Italian (124).

-

(123)

-

(124)

That the ATB account can derive this pattern is not in dispute. The current account derives this pattern through either (i) agreement with the uninterpretable number features of the pluralia tantum noun when interpretable features are not active or, alternatively, (ii) agreement with interpretable [pl]; see Acquaviva (2008) on the semantic contribution of plural for pluralia tantum nouns. The current account would only generate the “wrong” singular value on postnominal adjectives if pluralia tantum nouns could be represented as having uninterpretable [pl] with an interpretable [sg]. I am aware of no independent evidence in Italian for this representation.

4.5 Section summary

The current approach builds Italian nominal expressions with SpliC adjectives from multidominant structures, with semantic agreement limited to particular configurations giving rise to agreement patterns in which the marking of the noun diverges from that of the adjectives. It was shown that various alternative approaches face challenges, including those that employ relative clauses, direct coordination of aPs, ellipsis, and ATB movement.

I now turn to a potential challenge for the account of SpliC expressions from a class of nouns with exceptional gender properties, showing that the data are in fact consistent with the approach.

5 A challenge? Gender agreement with switch nouns

One class of nouns exhibits a striking pattern when modified by SpliC adjectives. The nouns in question have the unusual property that they take masculine agreement in the singular but feminine in the plural (125).

-

(125)

As Acquaviva (2008) and Adamson (2018) show, the difference between the singular and plural is represented in terms of gender features (though see discussion of variation in Loporcaro 2018, 85–86). This becomes evident when looking at cases in which there is a number mismatch between an overt nominal in the plural and a gender-agreeing phrase in the singular. While there is no overt f.sg form of these nouns (126)–(127a), f.sg agreement arises with the f.pl nouns in various environments (127b).

-

(126)

-

(127)

Given their more complex gender status, switch nouns present an interesting puzzle for when they are modified by singular SpliC adjectives: should the adjectives agree with the gender of the feminine plural noun or the gender of the corresponding masculine singular?

If there are two singular nPs, as in the case of an ATB analysis, the prediction should be that each noun is masculine and correspondingly the adjectives should agree with the masculine. Under this analysis, it should not be possible to have f.sg adjectives modifying a f.pl noun, since each adjective would modify a feminine singular nP within each conjunct (being subsequently raised ATB); there is no feminine singular incarnation of the noun.

In contrast, the current analysis only has a single, shared nP, so we expect a feminine plural noun to trigger feminine agreement on each adjective. We observe that this is indeed possible (128).Footnote 24

-

(128)

This pattern can be captured under the multidominant analysis. I assume that gender licensing conditions for roots are applicable at the interfaces, following Kramer (2015) (see also Adamson and Šereikaitė 2019). For inanimate roots, licensing by either [m] or [f] is in the postsyntax, for example at the point of exponence. While various details need not concern us, what is relevant is that a root such as \(\sqrt{\text{\textsc{{bracc}}}}\) is licensed in the context of an n with various combinations, but crucially not with the combination of feminine with singular (see relatedly the analysis in Acquaviva 2008, Chap. 5).Footnote 25

Recall that only uFs survive along the PF branch. Therefore, whatever number feature is relevant for exponence of the noun is the one that determines which gender value can appear. For resolved, plural nouns with SpliC adjectives, the feature [pl] is compatible with [f]. In order for resolution with inanimates to yield [f], both gender features must be u[f]. (That there is a point in the syntactic derivation where nP bears [f] and multiple [sg] features is unproblematic, because this feature combination does not come to be evaluated for licensing.) A derivation is sketched for resolution in (129).

-

(129)

Adjective number agreement is for iFs—thus iFs are resolved on the nP at Transfer. Because the grammatical gender values are uninterpretable, semantic resolution will not occur for them, but PF will be able to provide a single output for them in the form of feminine inflection. The interpretable number features are also used to provide the uF slot with a value via the redundancy rule; it is these uF features that are relevant to the gender licensing of the head noun’s root at PF (129b).

The combination of [f] and [sg] is prohibited with these nouns at PF. In the case of split coordination where the head noun is marked singular, the prediction is that it must be m in order to satisfy its gender licensing requirement; we therefore predict that it should trigger masculine agreement. This is borne out, as shown by the following. (Note that speakers prefer (130b) over (130a), perhaps because (130b) does not present the issue of gender mismatch between the singular and plural incarnations of the noun.)

-

(130)

-

(131)

In sum, the current account is consistent with the behavior of gender agreement with switch nouns occurring with SpliC adjectives. Assuming gender licensing applies at the interfaces, the possible combinations of gender and number come out correctly under the present account.

6 Cross-linguistic variation