Abstract

Beck et al. (2009) and much follow-up research (including Bochnak 2015; Bowler 2016; Deal and Hohaus 2019) argue that languages systematically differ in the semantics of gradable predicates like tall and old, with some languages adopting a vague, delineation-based semantics and others adopting a relational, degree-based semantics. Beck et al. (2009) capture this point of variation in the so-called Degree Semantics Parameter. Based on elicitation and corpus data, we suggest here that the grammar of Samoan (Austronesian, Oceanic; Independent State of Samoa, American Samoa) has recently undergone a change from one parameter setting to the other, triggered by the addition of a degree-based comparative operator to the functional lexicon of the language. This operator developed through lexical and syntactic re-analysis from a directional particle. In Samoan, the grammar of degree is thus modelled after the grammar of another scalar domain, directed motion in space, a strategy that the typological literature suggests is cross-linguistically common.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper investigates Beck et al.’s (2009) influential Degree Semantics Parameter ±DSP from a diachronic angle: Does the semantics of gradable predicates ever change from delineation to degree-based (or vice versa)? If so, what are the pathways of this change? The answers we will provide here are based on a case study on language change in Samoan (Austronesian, Oceanic), a highly analytic verb-initial language with split-ergativity, spoken by approximately 175,000 speakers on the Samoan archipelago. The contemporary language has been analysed as having a +DSP setting, where gradable predicates receive a degree-based analysis (Beck et al. 2009; Hohaus 2012, 2015, among others). We argue here that this +DSP setting is the result of a “felicitous conspiracy of changes” (Eckardt 2012: 2675) that were involved in the re-analysis of the particle atu ‘away, thither’ from a directional particle to a comparative operator, in an extension of its type domain from locations to degrees.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: In the next section, we will review the two approaches to the semantics of gradable predicate and the Degree Semantics Parameter. We will then briefly discuss the analysis of comparison constructions in Present-Day Samoan (PDS), whose directional comparative construction requires a +DSP analysis. In Sect. 3, we present data from two corpora compiled for the purposes of this research that show that this construction is not attested in an earlier stage of the language, Early-Written Samoan (EWS), as also suggested by remarks in the descriptive and typological literature. We conclude that while gradable predicates in PDS have a degree semantics, gradable predicates in EWS can be analysed under a delineation approach. We model this change (and thus the change in the setting of the DSP) in Sect. 5. Section 6 concludes and discusses the broader implications of our findings for semantic change and cross-linguistic variation.

2 Background

2.1 Two approaches to the semantics of gradable predicates

The starting point of this paper is one of the core properties of the semantics of gradable predicates: In their positive form in (1a), they are vague and context dependent in their interpretation. However, in their comparative form in (1b), they are not, and the sentence in (1b) is true if and only if Yapeng’s height exceeds Shatha’s height, irrespective of the context the sentence is uttered in.

-

(1)

The two main approaches to the semantics of gradable predicates account for this property in different ways.Footnote 1 Under what we are going to refer to as the delineation approach (Kamp 1975; Klein 1980, 1982, 1991; van Rooij 2011, inter alia), the vagueness and context dependency of (1a) are wired into the lexical meaning of those predicates. Gradable predicates like tall in (2) induce a three-way partition on a set of individuals, the comparison class C, into those we consider definitely tall (= the positive extension of tall \(+_{\text{\textsc{height}},\,c}\)), those we consider definitely not tall (= its negative extension \(-_{\text{\textsc{height}},\,c}\)), and those borderline cases which fall into the extension gap, for which the predicate is undefined (\(\circ _{\text{\textsc{height}},\,c}\)).

-

(2)

For any comparison class \(C \in D_{\langle e,t\rangle}\) and individual \(x \in D_{e}\), 〚 tall 〛(C)(x)

is defined iff x∈C & x is considered either tall or not tall in relation to C.

If defined, 〚 tall 〛(C)(x)=1 iff x is considered tall in relation to C

A comparative like (1b) then is composed from the interpretation of the positive in (2), and is true if and only if there is a comparison class in which Yapeng counts as tall and Shatha does not, that is, the comparative operator, in (3), assigns the comparee (= Yapeng) to the positive extension of tall, and the standard (= Shatha) to the negative extension. If Yapeng is indeed taller than Shatha, the set containing just the two of them is the smallest possible comparison class to make the sentence true.

-

(3)

For any relation \(R \in D_{\langle \langle e,t\rangle ,\langle e,t\rangle \rangle}\) and individuals \(x,y \in D_{e}\),

〚 -er 〛(y)(R)(x)=1 iff ∃C [R(C)(x)=1 & R(C)(y)=0]

The interpretation of the comparative under a degreeless analysis thus relies on manipulating the partitions of the comparison class and, in the words of Morzycki (2015: 99), their “precisification.” The actual height ordering between the comparee and the standard, however, remains implicit but can be inferred.

Under the degree approach (Cresswell 1976; von Stechow 1984a,b; Kennedy 1997; Beck 2011, to name but a few), gradable predicates make reference to degrees, abstract entities that are elements of measurement scales. The adjectival root is interpreted as relational, as in (4), and the vagueness and context dependency of the positive form in (1a) are introduced by a covert operator that also binds the degree argument (see also von Stechow 1984a, 2009; Fults 2006; Kennedy 2007).

-

(4)

The comparative in (1b) is true under the degree-based analysis if and only if the maximal degree to which Yapeng is tall exceeds the maximal degree to which Shatha is tall. The comparison is explicit rather than implicit.

-

(5)

The delineation approach is elegant in that it allows for a transparent mapping of form to meaning. It is, however, not equal to the degree approach in expressive power: Its only mechanism for comparison is manipulating the partitions induced by the adjective. As observed by von Stechow (1984b), differential measure phrases (and, by extension, differential degree questions) as well as factorial phrases as in (6) cannot be analysed under such an approach, given that these rely on addition and multiplication. Additional technology (in the form of equivalence classes) is also required for the semantic analysis of the constructions in (7), namely degree questions and other constructions with full or pronominal measure phrases. Gradable adjectives in English are thus standardly analysed as having a degree-based semantics (see Beck 2011 and Morzycki 2015 for overviews).

-

(6)

-

(7)

Beck et al. (2009) and much subsequent research in the past ten years have, however, suggested that the two approaches to the semantics of gradable predicates have a cross-linguistic reality and that the choice between the two analyses is a systematic point of cross-linguistic variation (see also Hohaus and Bochnak 2020 for a recent overview).

2.2 The degree semantics parameter

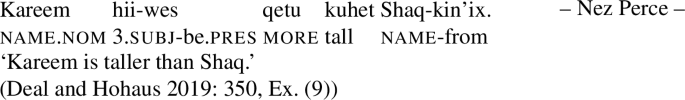

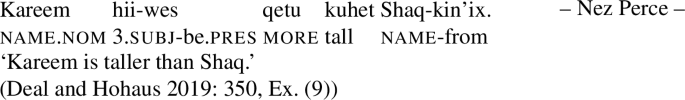

Languages in which gradable predicates are not acceptable in the constructions in (6) and (7) lend themselves to a delineation-based analysis (Beck et al. 2009; Bochnak 2015; Bowler 2016; Deal and Hohaus 2019). Such languages might lack dedicated functional morphology for gradable predicates altogether and express comparison via a morpho-syntactic conjunction strategy as in (8), from Motu (Austronesian, Oceanic; Papua New Guinea). They may, however, superficially also look very much like English, as is the case for Nez Perce (Penutian, Sahaptian; United States of America), in (9). However, comparatives in Nez Perce crucially do not support differential measure phrases (see Deal and Hohaus 2019 for further discussion).Footnote 2

-

(8)

-

(9)

Beck et al. (2009) suggest that the observed variation in expressive power in comparison construction can be explained by assuming that languages systematically vary in whether they adopt a delineation or degree semantics for gradable predicates. They frame this proposal as a parameter of cross-linguistic variation, the Degree Semantics Parameter in (10).

-

(10)

Degree Semantics Parameter (DSP):

A language {does/does not} have gradable predicates (type 〈d,〈e,t〉〉 and related), i.e., lexical items that introduce degree arguments. (Beck et al. 2009: 19, Ex. (62))

Villalta (2007a,b), Beck et al. (2009), and Hohaus (2012, 2015) analyse Present-Day Samoan (PDS) as a +DSP language whose gradable predicates have a degree-based semantics. The next section briefly reviews the evidence for such an analysis (see the references cited for further details).

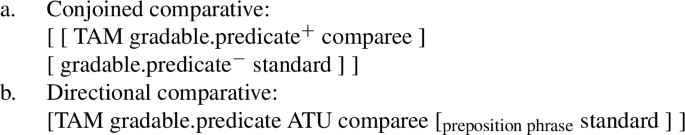

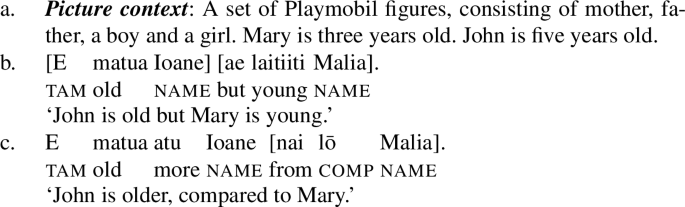

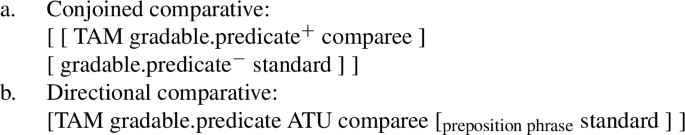

2.3 Comparison constructions in present-day Samoan

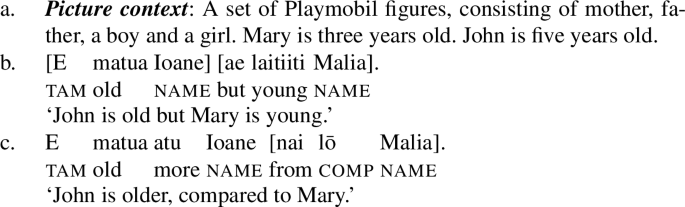

PDS has two morpho-syntactic strategies to express a comparison, sketched in (11), which in terms of their semantics translate to implicit and explicit comparison. Just like Motu (discussed in the previous section), PDS employs a conjoined comparative, a bi-clausal construction, an example of which is in (12b).Footnote 3 The conjoined comparative in PDS is not evaluative, that is, (12b) does not entail that John is old (nor that Mary is young). Even though speakers find the conjoined comparative acceptable in the context provided (and actively produce this structure), some express a preference for the other morpho-syntactic strategy that PDS has to express a comparison, in (12c). We will refer to this type of construction here as the directional comparative.

-

(11)

-

(12)

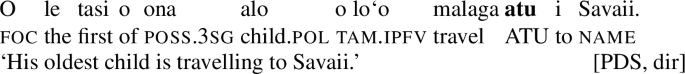

The label for (11b) derives from the fact that the particle atu, which we have glossed as translating to ‘more’ above, serves double duty in PDS as both comparative morphology and a directional particle to be used with predicates that encode an actual or metaphorical motion, like alu ‘to go’ in (13). We return to this example and to its semantic analysis in Sect. 5.1 below.

-

(13)

Circling back to the comparative interpretation of atu, evidence for a degree-based analysis comes from directional comparatives with differential measure phrases like (14). Comparatives like (15), where the standard is a measure phrase, also receive a straightforward analysis under the degree approach.

-

(14)

-

(15)

While thus degree-based like its English counterpart, an important difference between the two languages is the compositional status of the nai lō-standard phrase. Because of its ability to take scope outside of syntactic islands, Hohaus (2015) analyses these phrases as frame-setting adjuncts, with a semantics similar to that of English compared to-phrases. As they are thus not arguments of the comparative operator, but rather only indirectly manipulate the standard of the comparison, we will largely set them aside in what follows.

Samoan also differs from +DSP languages like English in that other constructions that would require a degree-based analysis are unavailable, as summarised in Table 1, based on Beck et al. (2009), Hohaus (2012, 2015), and Bowler (2016). With the exception of the directional comparative, the language patterns more like the –DSP languages Motu and Warlpiri with respect to the established diagnostics for degreehood. Note, however, that the language has other morphological means for comparison, including intensification and the superlative (see also Hohaus 2021). Crucially, though, if it were not for the directional comparative, there would be no reason to adopt a degree-based analysis of gradable predicates in the language.

The synchronic differences between English and PDS plausibly have a diachronic explanation: In the descriptive and typological literature, the directional comparative has been reported to be a recent innovation (Marsack 1975; Stassen 1985), with the conjoined comparative the traditional strategy of comparison (see also Holmer 1966; Chung 1978; Beck et al. 2009). Early grammatical descriptions of the language (Pratt 1862, 1878; Funk 1893; Neffgen 1903; Jensen 1925/1926) only describe the conjoined structure, while the contemporary literature only reports the directional comparative (Hunkin and Galumalemana Afeleti 1992; Mosel and Hovdhaugen 1992; Mosel and So’o 1997). Based on these initial observations, we propose the hypotheses in (16).

-

(16)

The next section aims at putting the observations from the literature and these hypotheses on a more robust empirical footing with a comparison of data from two corpora that we constructed for this purpose. The first corpus is a corpus of the contemporary language, the second a corpus from the earliest stages of the textualisation of the language, circa 1859 to 1915, which we are going to refer here as Early Written Samoan (EWS).

3 The corpus data

In this section, we present data in support of H1 and H2 from two studies based on two corpora, a corpus of Early Written Samoan and a corpus of Present-Day Samoan, described in Sect. 3.1. The first study, in Sect. 3.2 (and also reported in Hohaus 2018), compares the interpretation of atu in the two corpora. We find that comparative atu is only attested in the PDS corpus, but not in the EWS corpus. The second study, in Sect. 3.3, is a reverse corpus search of the EWS corpus on translational strategies for the degree-based comparison constructions in the 1611 King James version of the Bible in English. We find that none of the translational strategies require a +DSP analysis of EWS.

3.1 The corpora

In the absence of a continuous accessible record of the language, with a noticeable gap in publications in and on the language from the beginning of the First World War until the Western islands gained back independence in 1962, we created two corpora for the purposes of comparison; see Tables 2 and 3.Footnote 4,Footnote 5

Texts for the corpora were selected based exclusively on their time of publication and their accessibility, resulting in a certain amount of variation in the genera of texts included. The first corpus, the corpus of Early Written Samoan, contains texts from a first and very productive phase of publications in and on the Samoan language, circa 1830 to 1915. The beginning of this time period coincides with the arrival of greater numbers of foreign traders and missionaries on the islands; it ends when New Zealand seized control over the Western islands (then the colony of German Samoa) in 1914.Footnote 6,Footnote 7 The second corpus, the corpus of Present-Day Samoan, is a corpus of the contemporary language.

3.2 The first corpus study

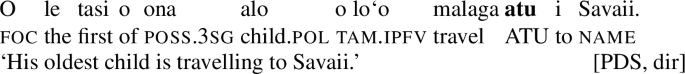

For both corpora, we performed a manual or, where possible, computerised search for atu, and classified the occurrences according to their interpretation as directional (dir), comparative (comp) or unclear. Three homonyms of atu were excluded altogether, namely nominal atu translating, either to ‘range, row, set’ or to ‘fish, bonito’ as well as verbal atu, translating to ‘to worry, to be anxious’ (Milner 1966: 28). Representative examples of directional atu from both corpora are in (17) and (18); an example of comparative atu from the PDS corpus is in (19).

-

(17)

-

(18)

-

(19)

The examples classified as unclear include serial constructions like (20), where the first predicate encodes an event that can be conceptualised as having a direction (such as momo‘e ‘to run’), and the second predicate encodes a property concept (such as vave ‘to be fast’). A directional interpretation of atu with the bracketing in (21a) is the contextually plausible interpretation in all of the examples. Note, however, that in PDS, these examples are ambiguous and can also be bracketed as sketched in (21b), which results in the comparative interpretation, provided in brackets in (20). We return to these examples in Sect. 5.3, where we speculate that these specific environments might have facilitated the syntactic and lexical re-analysis of directional atu into comparative atu.

-

(20)

-

(21)

We report the results of the two corpus searches in Tables 4 and 5, which include the absolute number of occurrences of atu as well as, in brackets, the estimated frequency per 1000 words.Footnote 8 The last row of each table specifies the distribution of the different readings within the corpus8. While we did not find any instances of comparative atu in the EWS corpus, there are 144 such instances in the PDS corpus. Directional comparatives in PDS thus occur with a relative frequency of 4 per 1000 words, based on the estimated corpus size. They account for 7.18 percent of occurrences of atu in the PDS corpus. Given this relative frequency of comparative atu in the PDS corpus, we might thus have expected to find 89 instances of comparative atu in the EWS corpus. Given the distribution of the two interpretations in the PDS corpus, we might have expected to find 268 instances of comparative atu in the EWS corpus.Footnote 9 We find none. This difference in the distribution of the two interpretations of atu across the two corpora is statistically highly significant under a chi-square test for independence (\(\chi ^{2} = 272.7\), df=1, p<.0001).

We interpret these results to mean that atu only had a directional interpretation in EWS, and that EWS lacked comparative morphology. This finding has implications for the setting of the Degree Semantics Parameter in EWS: Evidence for +DSP in PDS comes only from the comparative, and more specifically from the fact that it supports differential measure phrases and comparison with a degree (see Sect. 2.3 above). This evidence is not available for EWS, and PDS can be analysed as degreeless in the sense that it is a –DSP language, where gradable predicates are vague.

3.3 The second corpus study

Such an analysis also receives support from a reverse search of the EWS corpus that investigates translational strategies for those constructions that require a degree-based semantics in English (see also Sect. 2.2), listed in (22). For the purposes of the second study, we manually classified all occurrences of comparison constructions in the five books of Moses and the four canonical gospels in the 1611 King James version of the Bible (KJV), which plausibly was used by the translators (from the London Missionary Society; see also Lundie 1846; Turner 1861, 1884; Garrett 1982; Robson 2009). We then compared those bible verses that contained any of the constructions listed in (22) with the 1862 Samoan Bible translation.

-

(22)

If gradable predicates in EWS indeed only had an inherently vague semantics, we would expect the EWS translations to rely on paraphrases that do not involve a gradable predicate. The reverse search also serves to ascertain whether EWS had any other functional morphology for the comparative, instead of PDS atu. A more systematic investigation of other comparison constructions in EWS beyond the ones in (22) was not conducted, as they do not inform the setting of the Degree Semantics Parameter in the language, and may receive a vague or a degree-based analysis.

The results from the corpus study are reported in Table 6. The first column lists the total number of occurrences of the constructions from (22) in the five books of Mose and the four canonical gospels in the 1611 KJV. The second column specifies the number of translations that require a +DSP analysis (equivalent to their English counterparts), and the third column lists the number of occurrences using alternative strategies in the translation of the degree-based constructions. Of the 123 instances found and analysed, none were translated in a manner that would require a +DSP setting. This can also be seen in (23), in the translations for the examples from (22). Unlike their English counterparts, none of the translations employ a gradable predicate: Instead of the differential comparative in English, in (22a), we find an additive nominal construction. The differential degree questions in (22b), in the translation, also use a nominal structure. The equative construction with the factorial phrase in (22c) is translated with a numeral predicate. The no more than-comparison with a degree in (22d) is replaced by the exclusive particle na‘o ‘only’ (see also Hohaus and Howell 2015; Howell et al. 2022). Instead of the seventy-five years old-measure construction, we find a relative clause with a numeral predicate in (23e). The English degree question in (22f) is translated by a temporal until when-question.

-

(23)

Modulo general methodological concerns relating to the absence of negative evidence from corpora (but see Stefanowitsch 2006; Lemmens 2019; Newmeyer 2019), the results from both corpus studies provide robust empirical evidence in support of the remarks in the descriptive and typological literature (in particular, Marsack 1975; Stassen 1985) that comparative atu is a fairly recent (that is, 20th century) addition to the grammar of Samoan. It is plausible that comparative atu developed from directional atu through a process of grammaticalisation, which we model more formally in Sect. 5. While this is an interesting diachronic finding in its own right, it also has implications for the analysis of gradable predicates in EWS, which we discuss in more detail in the next section.

4 The grammar of EWS

The absence of comparative atu in the corpus translates to an absence of those constructions that, for PDS, have been taken as evidence for a degree-based analysis of gradable predicates and of comparison constructions more generally. The grammar of EWS comparison thus lends itself to the vague and delineation-based analysis that is summarised in Table 7. Adopting the argumentation in the literature on –DSP languages (see in particular Beck et al. 2009; Bochnak 2015; Bowler 2016; Deal and Hohaus 2019), we take such an analysis not only to be available in this case, but also to be more parsimonious. (It is, however, not without an alternative; see below.)

Under such an analysis, EWS adopts an implicit strategy for comparative meaning that is based on the assignment to the different partitions of the comparison class rather than on the comparison of degrees. This strategy is exemplified in the conjoined comparative in (24) from the EWS corpus. Its interpretation is in (25), where \(L_{\textrm{Joseph}}\) represents the interpretation of the subject noun phrase from the first clause (= the love Joseph’s father Jacob has for Joseph).

-

(24)

-

(25)

The –DSP analysis in Table 7 does not preclude a language from having functional morphology for comparison (see also Bowler 2016; Deal and Hohaus 2019) as long as the underlying semantics is based on the interpretation of the Positive form. From a qualitative inspection of the EWS corpus, it appears that the language indeed had a number of comparison constructions besides the conjoined comparative, including (but not restricted to) superlative aupito in (26), which is also attested as one of the strategies to express a superlative in PDS.

-

(26)

A degreeless semantics for aupito across EWS and PDS is in (27), under which the superlative is composed from the Positive and assigns all members of the contextual comparison class but the associate to the negative extension of the gradable predicate. This implicit superlative allows the inference that the associate exceeds everyone in the comparison class with respect to the relevant property.

-

(27)

The absence of evidence for a degree-based analysis of comparison constructions in EWS does, however, not preclude such an analysis. An alternative analysis of the EWS data is one under which gradable predicates are degree-based (just like they are in PDS) but the language would lack a degree-based comparative operator and adopt an implicit strategy of comparison, thereby forfeiting much of the expressive power degrees provide. Such an analysis would situate the variation observed between the two stages of the languages as concerning the inventory of comparison operators in the functional lexicon rather than the semantics of gradable predicates. While possible, we side here with the large body of literature on the crosslinguistic semantics of comparison constructions that parsimony provides a strong conceptual argument against such an analysis (most notably Beck et al. 2009, but also including Pearson 2010; Bochnak 2013, Bochnak 2015; Bochnak and Bogal-Allbritten 2015; Bowler 2016; Reisinger and Lo 2017; Deal and Hohaus 2019; Hohaus and Bochnak 2020).

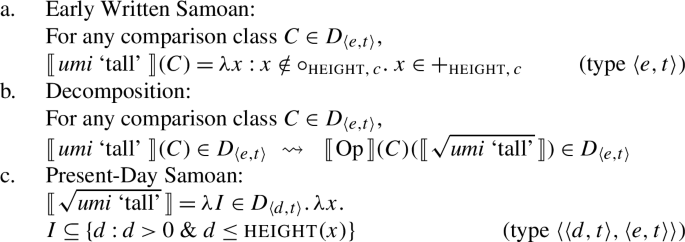

5 Modelling the change

While we lack the data to trace the grammatical development from EWS to PDS in any further detail, we will sketch here a model of the change in the grammar between these two stages of the language, building on earlier suggestions in Hohaus (2018). Such a model will require an analysis of how atu came to acquire its comparative meaning in addition to its directional meaning, and an analysis of how the meaning of gradable predicates changed from vague to relational, a change that also compositionally re-allocates the vagueness associated with the positive form from the lexical entry of the gradable predicate to the covert pos-operator.

5.1 Directed motion in EWS and PDS

Hohaus (2012, 2018) suggests that, under its directional interpretation in (28), the particle atu operates on paths. Paths can be thought of as sequences of adjacent locations \((l_{0}, l_{1}, l_{2}, l_{3}, \dots l_{n})\), whose length exceeds one (but see also Cresswell 1978; Piñón 1993; Krifka 1998; Zwarts 2005). We assume that locations are elements of the denotation domain \(D_{l}\). For any path p, the beginning of the path, beg(p), is that location such that there is no other location that precedes it in the sequence. Likewise, the end of a path p, end(p) is that location such that there is no location in the sequence that follows it. Verbs of motion like alu ‘to go’ in (29) do not only describe a manner of motion (here, walking as opposed to running), but also relate individuals to their movement paths, and thus to the set of locations that they have passed through.

-

(28)

-

(29)

〚 alu ‘to go’ 〛 = λp. λx. x walks along p (type 〈〈l,t〉,〈e,t〉〉)

Directional particles impose further restrictions on these paths. Atu requires that the path is directed away from the location at which it started out. Hence, every non-initial location \(l_{n}\) that is an element of the path is required to be further away from the beginning of the path beg(p) than the next lower-ranked location in the sequence, \(l_{n-1}\) or \(\textrm{pre}(l_{n})\). The sets of locations that constitute a directed motion path are thus totally ordered, a property they share with the denotation domain of degrees \(D_{d}\). (We will return to this property shortly.) We adopt the semantics in (30) for directional atu, under which it is of type 〈〈l,t〉,〈〈〈l,t〉,〈e,t〉〉,〈e,t〉〉〉.

-

(30)

Even though of distinct semantic types in the grammar, the locations that are part of a directed motion path are just like degrees: A scale is a set of elements (= degrees) that is totally ordered. We propose that this shared property allowed for the path-based semantics of atu to be extended to a degree-based semantics, from type 〈l,t〉 to type 〈d,t〉. More specifically, in a contextual comparative like (31), the difference degree interval can be thought of as a directed path along the height scale, as in Fig. 1: The origin of the path is the contextual comparison standard c; its endpoint is the right boundary of the degree interval that Mary occupies on the height scale (see also Schwarzschild 2012).

-

(31)

We suggest that the change observed exploits the conceptual parallels between directed motion paths and the difference interval on a degree scale. PDS atu is thus another example of functional material that has come to be “used in different conceptual domains, as long as the domains can be understood as being structured in a certain way” (Herwig and Wunderlich 1991: 785, my translation). We propose a formal model of this change in the next section.

5.2 From directed motion to degree-based comparison

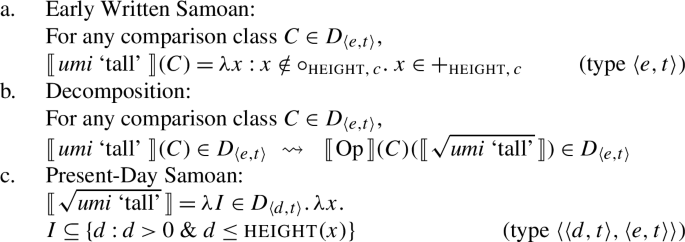

We suggest that the addition of atu-comp to the grammar of Samoan can be understood as resulting from a generalisation from the type of paths involved in the interpretation of atu-dir (= directed paths, type 〈l,t〉) to a type domain whose elements share with directed paths that they are linearly ordered (= degrees, type d). The result of this type transfer is in (32), a differential, contextual comparative operator, based on degree intervals, to the exclusion of empty and degenerate intervals.Footnote 10

-

(32)

This comparative operator can only compose if gradable predicates make available a degree interval. Assuming that the grammar of EWS was –DSP, the development of atu-comp will, therefore, have had to go hand-in-hand with a re-analysis of the semantics of gradable predicates. More specifically, we suggest that adding the comparative operator in (32) to the functional lexicon of the language co-occurred with a decomposition of the vague, degreeless gradable predicate in (33a) into a root and a covert Positive operator, as in (33b); see Hohaus et al. (2014) for similar suggestions for the acquisition of +DSP in English and German children. The resulting lexical entry for the gradable predicate, in (33c), is degree-based, and the resulting language stage can be characterised as +DSP.Footnote 11

-

(33)

In the process of this decomposition, the context dependency of the gradable predicate (that in EWS is part of its lexical meaning) is thus delegated to a covert operator. We propose such an operator in (34), a degree-based operator that mimics the behaviour of the vague predicate. Assuming that degree scales have a tripartite structure (von Stechow 2008, 2009), as in Fig. 2, this operator locates the endpoint of x’s maximal height interval within an interval that is an element of the upper partition \(+_{\mathfrak{S},c}\) of the scale. If we take the height scale, for instance, those would be the height degrees of those people we consider tall in relation to a given comparison class.

-

(34)

Putting the pieces together, the interpretation of the contextual comparative from (31) under this analysis is in (35), where the differential argument has undergone existential closure. The sentence is true if and only if there is a proper degree interval that is a subset or equal to Mary’s height interval and whose left-close boundary is the contextual comparison standard c. Such a proper interval will only exist if Mary’s height exceeds the degree c. This degree will be contextually provided, but can also indirectly be restricted by a nai lō-phrase; see Hohaus (2015) for details.

-

(35)

Differential measure phrases such as i le lua inisi ‘by two inches’ measure the length of this difference interval the comparative describes (see also, e.g., Schwarzschild and Wilkinson 2002), as in (36).

-

(36)

While the parallels between directed motion paths and difference intervals are conceptually attractive, the change would have required the right type of syntactic environment to proceed. We identify one such environment in the next section.

5.3 Bridging contexts and syntactic re-analysis

The lexical development of atu-comp from atu-dir would have required a syntactic environment where the particle is able to combine with either a motion predicate or a gradable predicate. Serial predicate constructions provide such an environment, and we therefore speculate that they may have been instrumental in the language change we have observed. Recall from above that examples like (20), where a motion predicate is followed by a gradable predicate, are ambiguous in PDS between a comparative and a directional interpretation. Diachronically, these examples would have lend itself to re-bracketing and the re-analysis of atu sketched in (37). Contexts that support the re-analysis from (37a) to (37b) and act as bridging contexts are plausibly frequent; the two interpretations overlap in the contexts that make them true: That is, contexts in which an individual runs away are always contexts in which that individual runs, and if someone runs fast, it is always also true that he is running faster than some contextually salient standard, in this the case the contextual threshold for what is considered fast running.

-

(20)

-

(37)

The syntactic re-analysis in (37) will have had to go hand-in-hand with the lexical re-analysis of atu as a comparative operator and the decomposition of the gradable predicate into a degree-based root. The change we have observed for Samoan can thus be modelled as being a result of three parallel processes: One, the syntactic re-analysis of a specific syntactic configuration under certain contextual conditions. Two, the type transfer from paths (type 〈l,t〉) to degree intervals (type 〈d,t〉) in the lexical entry of atu. Three, the decomposition of the meaning of the gradable predicate into a covert operator and a relational root meaning based on degree intervals, which can combine with the new comparative operator.

6 Discussion and conclusion

This paper added a diachronic perspective to the analysis of the grammar of comparison in Samoan. The data from the corpus of Early-Written Samoan (EWS) provide robust evidence in favour of the observations in the descriptive and typological literature that comparative atu is a recent grammatical innovation to complement the conjoined comparative construction. The findings have consequences beyond the analysis of the lexical semantics of atu, however: In the absence of evidence in favour of a degree-based analysis of gradable predicates, the grammar of comparison in EWS can receive a delineation-based analysis, based on a –DSP setting. We proposed and formalised a view of the development of the grammar of the language under which the development of a degree-based comparison operator co-occurs with a change in the semantics of gradable predicates, from –DSP to +DSP. In Samoan, the grammar of degree is thus derived from the grammar of space, with the directional comparative building on the conceptual parallels between a directed movement path away from a point of origin and the difference interval in a degree comparison.

Typological data suggest that this might be a common grammaticalisation path across the Oceanic languages and beyond (see also Holmer 1966; Stassen 1985; Dixon 2008). This paper thus opens up interesting perspectives for future research into the diachronic semantics of comparison constructions and the domains after which degrees are modelled in the grammar. It also allows us to reflect on the nature of semantic and parametric change: Is the change in the semantics of gradable predicates (and thus in the setting of the Degree Semantics Parameter) directional, and if so, why? Or do languages also change in the opposite direction and give up the composition of the unmarked form into a degree-based root and a covert Positive operator? From the perspective of expressive power, such a change does not appear plausible: In the case of Samoan, the grammar of comparison in PDS has more expressive power than the grammar of comparison in EWS; the set of comparisons that the former can express can be thought of as a superset of the set of meanings that the latter can express. A prohibition against the loss of expressive power might then block change in the reverse direction.

Notes

Abbreviations used in glosses: caus = causative, comp = marker of comparison standard, dem = demonstrative, emph = emphatic, foc = focus marking, inch = inchoative, incl = inclusive, ipfv = imperfective, neg = negation, nom = nominative, pfv = perfective, pl = plural, pol = polite, poss = possessive, prep = preposition, pres = present, prosp = prospective, prn = pronoun, Q = question particle, sg = singular, subj = subject, tam = tense-aspect marker, and top = topic marking.

Unless otherwise indicated, the data from contemporary Samoan comes from the author’s research since 2009, which involved five trips to the South Pacific and more than 80 language consultants based in Samoa, New Zealand, Hawaii and Germany. Data collection involved translation, acceptability rating and natural production tasks (Matthewson 2004, 2011; Burton and Matthewson 2015), and combined both qualitative and quantitative methodology.

Word count estimates for the EWS corpus as well as the children’s literature in the PDS corpus were calculated based on the average number of words per page based on a manual word count for a representative number of pages. The word count estimate for the newspaper articles in the PDS corpus is based on a PDF word count performed online.

The earliest texts in the EWS corpus are translations, which may raise some methodological concerns. The translations are, however, reported to have been made in collaboration with native speakers (Lundie 1846: 75).

The earliest written record of the Samoan language dates back to the early 1830s and thus to shortly after John Williams from the London Missionary Society arrived on the islands in 1830 and published the first three books in Samoan in 1834 after having developed a writing system for the language based on the Latin script (Ellis 1844; Lundie 1846; Turner 1861, 1884; Moyle 1984).

While the German colonial administration is reported to not have taken much of an interest in the language and Samoan continued to be used as the language of instruction in schools (Engelberg 2014), New Zealand adopted a more suppressive approach that also involved banning it from schools (Hang and Baker 1997).

We attribute the overall lower relative frequency of atu in the PDS corpus compared to the EWS corpus to the difference in text type and genre, with a lower number of two of the most frequent tokens in the EWS corpus, namely, fai atu ‘to say’ and tali atu ‘to reply’.

The difference in the expected number of occurrences based on relative frequency versus distribution is a result of the overall lower relative frequency of atu in the PDS corpus; see also footnote 7 above.

Note that the second conjunct of (30) is superfluous here given that degrees, unlike the locations in the case of atu-dir, are already totally ordered by definition.

As a result of our assumptions about the semantics of paths (type 〈l,t〉) and the type transfer, the gradable predicate ends up with a semantics based on intervals, here understood as convex sets of degrees. Note that under the semantics proposed here, a gradable predicate like umi ‘tall’ then relates an individual to all the degree intervals that are a subset or equal to the degree interval that individual occupies on the scale, which begins at the scalar minimum and extends to their actual height. In this respect, the semantics assumed here differs from other interval-based approaches (most notably, Schwarzschild and Wilkinson 2002; Beck 2010). We will have to leave a more detailed comparison between the two analyses for another occasion.

References

Beck, Sigrid. 2010. Quantifiers in than-clauses. Semantics and Pragmatics 1(3): 1–72. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.3.1.

Beck, Sigrid. 2011. Comparison constructions. In Semantics: An international handbook of natural language meaning, eds. Claudia Maienborn, Klaus von Heusinger, and Paul H. Portner, II:1341–1389. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Beck, Sigrid, Svetlana Krasikova, Daniel Fleischer, Remus Gergel, Stefan Hofstetter, Christiane Savelsberg, John Vanderelst, and Elisabeth Villalta. 2009. Crosslinguistic variation in comparison constructions. Linguistic Variation Yearbook 9: 1–66. https://doi.org/10.1075/livy.9.01bec.

Bochnak, M. Ryan. 2013. Crosslinguistic variation in the semantics of comparatives, PhD dissertation, University of Chicago.

Bochnak, M. Ryan. 2015. The degree semantics parameter and crosslinguistic variation. Semantics & Pragmatics 8(6): 1–46. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.8.6.

Bochnak, M. Ryan, and Elizabeth Bogal-Allbritten. 2015. Investigating gradable predicates, comparison, and degree constructions in underrepresented languages. In Methodologies in semantic fieldwork, eds. Lisa Matthewson and Ryan Bochnak, 110–134. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bowler, Margit. 2016. The status of degrees in Warlpiri. Proceedings of TripleA 2: 1–17.

Burton, Strang, and Lisa Matthewson. 2015. Targeted construction storyboards in semantic fieldwork. In Methodologies in semantic fieldwork, eds. Ryan Bochnak and Lisa Matthewson, 135–156. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carle, Eric, and Ainslie Chu Ling-So’o. 2013. ‘O le ketapila matuā fia‘ai. Wellington: Huia Publishers.

Chung, Sandra. 1978. Case marking and grammatical relations in Polynesian. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Cresswell, Max J. 1976. The semantics of degree. In Montague Grammar, ed. Barbara Partee, 261–292. New York: Academic Press.

Cresswell, Max J. 1978. Prepositions and points of view. Linguistics and Philosophy 2(1): 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00365129.

Deal, Amy Rose, and Vera Hohaus. 2019. Vague predicates, crisp judgments. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung (SuB) 23: 347–364. https://doi.org/10.18148/sub/2019.v23i1.537.

Dixon, Robert M. 1977. Where have all the adjectives gone? Studies in Language 1(1): 19–80. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110822939.

Dixon, Robert M. 2008. Comparative constructions: A crosslinguistic typology. Studies in Languages 32(4): 787–817. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.32.4.02dix.

Eckardt, Regine. 2012. Grammaticalisation and semantic reanalysis. In Semantics: An international handbook of natural language meaning, eds. Claudia Maienborn, Klaus von Heusinger, and Paul Portner, III:2675–III:2701. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Ellis, William. 1844. The history of the London Missionary Society. London: John Snow.

Engelberg, Stefan. 2014. Die deutsche Sprache und der Kolonialismus. In Zur Rolle von Sprachideologemen und Spracheinstellungen in sprachenpolitischen Argumentationen, eds. Heidrun Kämper, Peter Haslinger, and Thomas Raithel, 307–322. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

Francez, Itamar, and Andrew Koontz-Garboden. 2017. Semantics and morphosyntactic variation: Qualities and the grammar of property concepts. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fraser, John 1898. Folk-songs and myths from Samoa. The Journal of the Polynesian Society 7(1): 15–29.

Fults, Scott. 2006. The structure of comparison: An investigation of gradable adjectives, PhD dissertation, University of Maryland, College Park.

Funk, Bernhard. 1893. Kurze Anleitung zum Verständniß der Samoanischen Sprache. Berlin: Mittler und Sohn.

Garrett, John. 1982. To live among the stars: Christian origins in Oceania. Geneva: World Council of Churches.

Hang, Desmond L., and Miles Baker. 1997. The place of the indigenous language in science lessons in Western Samoa. Directions: The Journal of Educational Studies 19(1): 100–121.

Herwig, Michael, and Dieter Wunderlich. 1991. Lokale und Direktionale. In Semantik: Ein internationales Handbuch der zeitgenössischen Forschung, eds. Arnim von Stechow and Michael Herwig, 759–785. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Hohaus, Vera. 2012. Directed motion as comparison: Evidence from Samoan. In Proceedings of Semantics of Under-Represented Languages of the Americas (SULA), Vol. 6, 335–348.

Hohaus, Vera. 2015. Context and composition: How presuppositions restrict the interpretation of free variables, PhD dissertation, Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen. https://doi.org/10.15496/publikation-8634.

Hohaus, Vera. 2018. How do degrees enter the grammar? Language change in Samoan from [−DSP] to [+DSP]. Proceedings of TripleA 4: 106–120. https://doi.org/10.15496/publikation-24546.

Hohaus, Vera. 2021. Gradability and modality: A case study from Samoan. In Polynesian syntax and its interfaces, eds. Lauren Clemens, and Diane Massam, 11–35. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hohaus, Vera, and M. Ryan Bochnak. 2020. The grammar of degree: Gradability across languages. Annual Review of Linguistics 6: 235–259. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011718-012009.

Hohaus, Vera, and Anna Howell. 2015. Alternative semantics for focus and questions: Evidence from Sāmoan. In Proceedings of the annual meeting of the Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association (AFLA), Vol. 21, 69–86.

Hohaus, Vera, Sonja Tiemann, and Sigrid Beck. 2014. Acquisition of comparison constructions. Language Acquisition 21(3): 215–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/10489223.2014.892914.

Holmer, Nils M. 1966. Oceanic semantics: A study in the framing of concepts in the native languages of Australia and Oceania. Uppsala: Lundeqvistska Bokhandeln.

Howell, Anna. 2013. Abstracting over degrees in Yoruba comparison constructions. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung (SuB) 17: 271–288.

Howell, Anna, Vera Hohaus, Polina Berezovskaya, Konstantin Sachs, Julia Braun, Åžehriban Durmaz, and Sigrid Beck. 2022. (No) variation in the grammar of alternatives. Linguistic Variation 22(1): 1–77. https://doi.org/10.1075/lv.19010.how.

Hunkin, Galumalemana Afeleti L.. 1992. Gagana Samoa: A Samoan language coursebook. Auckland: Polynesian Press.

Jensen, H. 1925/1926. Zur Grammatik des Samoanischen. Zeitschrift für Eingeborenen-Sprachen 16: 241–256.

Kamp, Hans. 1975. Two theories of adjectives. In Formal semantics of natural language, ed. Edward Keenan, 123–155. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kennedy, Christopher. 1997. Projecting the adjective: The syntax and semantics of gradability and comparison, PhD thesis, University of California, Santa Cruz.

Kennedy, Christopher. 2007. Vagueness and grammar: The semantics of absolute and relative gradable adjectives. Linguistics and Philosophy 30(1): 1–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-006-9008-0.

Klein, Ewan. 1980. A semantics for positive and comparative adjectives. Linguistics and Philosophy 4(1): 1–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00351812.

Klein, Ewan. 1982. The interpretation of adjectival comparatives. Journal of Linguistics 18(1): 113–136. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022226700007271.

Klein, Ewan. 1991. Comparatives. In Semantics: An international handbook of contemporary research, eds. Arnim von Stechow and Dieter Wunderlich, 673–691. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Krifka, Manfred. 1998. The origins of telicity. In Events and grammar, ed. Susan Rothstein, 197–235. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Lemmens, Maarten. 2019. In defense of frequency generalizations and usage-based linguistics. CogniTextes 19(1616): 1–56. https://doi.org/10.4000/cognitextes.1616.

Lundie, Duncan. 1846. Mary Missionary life in Samoa. Edinburgh: William Oliphant and Sons.

Marsack, Charles C. 1975. Samoan, 4th edn. Norwich: The English Universities Press.

Matthewson, Lisa. 2004. On the methodology of semantic fieldwork. International Journal of American Linguistics 70(4): 369–451.

Matthewson, Lisa. 2011. Methods in crosslinguistic formal semantics. In Semantics: An international handbook of natural language meaning, eds. Claudia Maienborn, Klaus von Heusinger, and Paul H. Portner, 268–284. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Milner, George B. 1966. Samoan dictionary. London: Oxford University Press.

Morzycki, Marcin. 2015. Modification. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mosel, Ulrike, and Even Hovdhaugen. 1992. Samoan reference grammar. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press.

Mosel, Ulrike, and Ainslie So’o. 1997. Say it in Samoan. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Moyle, Richard M. 1984. The Samoan journals of John Williams (1830 and 1832). Canberra: Australian National University Press.

Neffgen, Heinrich. 1903. Grammatik der samoanischen Sprache nebst Lesestücken und Wörterbuch. Wien: Hartleben.

Newmeyer, Frederick J. 2019. Conversational corpora: When ‘big is beautiful’. CogniTextes 19(1584): 1–83. https://doi.org/10.4000/cognitextes.1584.

O le Feagaiga Fou a lo tataou alii o Iesu Keriso, ua liu i le Upu Samoa. 1849. London: William Clowes and Sons.

O le Tusi Paia o le feagaiga tuai ma le feagaiga fou lea, ua Faasamoaina. 1862. London: British and Foreign Bible Society.

Pearson, Hazel. 2010. How to do comparison in a language without degrees: A semantics for the comparative in Fijian. Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung (SuB) 14: 339–355.

Piñón, Christopher P. 1993. Paths and their names. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Chicago Linguistics Society (CLS) 29: 287–303.

Pratt, George. 1862. Samoan dictionary with a short grammar of the Samoan dialect. Matautu: London Missionary Society’s Press.

Pratt, George. 1878. A grammar and dictionary of the Samoan language. London: Trübner.

Pratt, George. 1890. Tala faatusa mai atunuu eseese ua Faa-Samoaina e palate: Fables from many hands translated into the Samoan dialect. London: London Missionary Society.

Reisinger, Daniel K., and Roger Y. Lo. 2017. Comox: A degreeless language. Proceedings of International Conference on Salish and Neighbouring Languages (ICSNL) 52: 225–243.

Robson, Andrew E. 2009. Malietoa, Williams and Samoa’s embrace of christianity. The Journal of Pacific History 44(1): 21–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223340902900761.

Salesa, Damon. 2004. Mauaina o tātaou tu‘ā (Discovering our ancestors). Wellington: Learning Media.

Schuster, Ignaz, and Louis Violette. 1875. O Tala Filifilia mai Tusi Paia mai le feagaiga tuai ma le feagaiga fou. Freiburg: B. Herder.

Schwarzschild, Roger. 2012. Directed scale segments. Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 22: 65–82. https://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v22i0.2634.

Schwarzschild, Roger, and Karina Wilkinson. 2002. Quantifiers in comparatives: A semantics of degree based on intervals. Natural Language Semantics 10(1): 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015545424775.

Sierich, F. Otto. 1900. Samoanische Märchen. Leiden: Internationales Archiv für Ethnographie.

Snyder, William, Kenneth Wexler, and Dolon Das. 1995. The syntactic representation of degree and quantity: Perspectives from Japanese and Child English. In Proceedings of the West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 13: 581–596.

Stassen, Leon. 1985. Comparison and Universal Grammar. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Stefanowitsch, Anatol. 2006. Negative evidence and the raw frequency fallacy. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory 2(1): 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1515/CLLT.2006.003.

Stübel, Oskar 1896. Samoanische Texte unter Beihülfe von Eingeborenen gesammelt und übersetzt. Veröffentlichungen aus dem königlichen Museum für Völkerkunde 4(2–4): 54–246.

Thompson, Sandra A. 2004. Property concepts. In Morphologie: Ein internationales Handbuch zur Flexion und Wortbildung, eds. Geert Booij, Christian Lehmann, Joachim Mugdan, Stavros Skopeteas, and Wolfgang Kesselheim, II, 1111–1117. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Turner, George. 1861. Nineteen years in Polynesia: Missionary life, travels and researches in the islands of the Pacific. London: John Snow.

Turner, George. 1884. Samoa: A hundred years ago and long before. Edinburgh: R. and R. Clark.

Va’afusuaga, Jane. 2016. O le meaālofa mo Ana. Auckland: Little Island Press.

van Rooij, Robert. 2011. Explicit and implicit comparatives. In Vagueness and language use, eds. Paul Egré and Nathan Klinedinst, 51–72. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Villalta, Elisabeth. 2007a. Fragebogen zu Komparativen im Samoan. Language questionnaire. Tübingen: Eberhard Karls Universität.

Villalta, Elisabeth. 2007b. Komparative im Samoan. Manuscript. Tübingen: Eberhard Karls Universität.

von Stechow, Arnim. 1984a. Comparing semantic theories of comparison. Journal of Semantics 3(1–2): 1–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/3.1-2.1.

von Stechow, Arnim. 2008. Topics in degree semantics: Degrees. Lecture notes. Tübingen: Eberhard Karls Universität.

von Stechow, Arnim. 2009. The temporal degree adjectives früh(er)/ spät(er) (‘early(er)’/ ‘late(r)’) and the semantics of the positive. In Quantification, definiteness and nominalization, eds. Anastasia Giannakidou and Monika Rathert, 214–233. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

von Stechow, Arnim. 1984b. My reaction to Cresswell’s, Hellan’s, Hoeksema’s and Seuren’s comments’. Journal of Semantics 3(1–2): 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/3.1-2.183.

Wai, Fiti Leung. 2012a. ‘O lo‘u aso muamua ‘i le a‘oga. (My first day at school). Auckland: Read Pacific.

Wai, Fiti Leung. 2012b. Aso Fa‘ailogaina ‘o le Teuila (Teuila Festival). Auckland: Read Pacific.

Wai, Fiti Leung. 2014. Aso Sa Pa’epa’e (White Sunday). Auckland: Read Pacific.

Zwarts, Joost. 2005. Prepositional aspect and the algebra of paths. Linguistics and Philosophy 28(6): 739–779. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-005-2466-y.

Acknowledgements

I’m indebted to the speakers of Samoan that have contributed to this research: Fa‘afetai, fa‘afetai tele lava. For comments and discussion, I would also like to thank Sigrid Beck, Richardo Bermúdez-Otero, Margit Bowler, Ashwini Deo, Martina Faller, Andrew Koontz-Gardoben, Emily Hanink, Agnes Jäger, Malte Zimmermann and Richard Zimmermann, as well as the audiences at Gothenburg, Saarbrücken, Berlin, and London, Ontario. Zahra Kolagar, Amrah Gadziev, Benjamin Ulmer and Alina Schumm have provided invaluable help with the corpus search. I would also like to thank the staff at the archives of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Samoa-Apia, at the Macmillan Brown Library at the University of Canterbury in Christchurch and at the New Zealand Glass Case special collection at the University of Auckland library for their help in retrieving the materials for the corpus of EWS.

Funding

This research was funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft [German Research Foundation] under grant number 75650358, Sonderforschungsbereich 833 “The Construction of Meaning,” Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hohaus, V. Language change and the Degree Semantics Parameter. Nat Lang Linguist Theory (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-023-09600-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-023-09600-6