Abstract

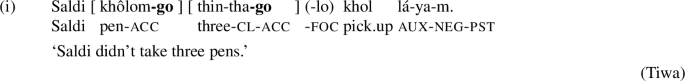

This paper explores a distinction between two phenomena that yield multiple realizations of case associated with one nominal. The first is the familiar type of nominal case concord; the second is a new phenomenon we label “case iteration.” While case concord involves the morphological realization of case on categorially distinct elements via feature sharing, case iteration arises via a separate mechanism and involves the realization of multiple instances of a functional head, which we model as D. In this sense, the case concord/case iteration distinction mirrors the agreement/clitic doubling distinction in the domain of argument-predicate matching. We argue for the existence of case iteration as a separate phenomenon primarily on the basis of novel data from Tiwa (Tibeto-Burman; India). In Tiwa, traditional case concord in continuous DPs is ruled out, but case iteration is obligatory in discontinuous DPs. We also demonstrate that this phenomenon is attested in Amahuaca (Panoan; Peru) and explore related patterns crosslinguistically.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

It is well known that similar surface patterns in natural language can arise via distinct underlying mechanisms. One domain where this has been explored extensively in the recent literature is argument-predicate matching. In this literature, it has been demonstrated that what pretheoretically looks like “agreement” in the verbal domain can actually be divided into two distinct phenomena: agreement and clitic doubling. True agreement arises when a verbal head directly bears the features of one of the nominal arguments of its clause. On the other hand, it is now typically assumed that clitic doubling involves the realization of an instance of the functional head D within the verbal complex. Crucially, agreement does not involve any overt material from the DP being realized on the verb, but clitic doubling does involve an overt instance of D from the nominal argument being realized on the verb.

These two mechanisms—agreement and clitic doubling—account for two distinct patterns that, while similar, have clear empirical differences. For example, Arregi and Nevins (2008) and Nevins (2011) argue that clitics, but not agreement markers, are tense-invariant—they have the same morphophonological form regardless of the tense and aspect marking of the verb on which they surface. Preminger (2009) has argued that agreement and clitic doubling can be distinguished by what happens when the respective operations fail. Failed agreement typically results in default features being spelled out on the verb, while failed clitic doubling results in no morphological realization of ϕ-features on the verb. Additionally, Harizanov (2014), Kramer (2014), and Baker and Kramer (2018) have noted that clitic doubling can change the calculus of binding relationships while agreement cannot. This growing body of work has not only contributed to our theoretical understanding of how agreement and clitic doubling are derived, but also to our empirical understanding of which properties pattern together in the realm of argument-predicate matching and why. Thus, developing our understanding of this somewhat fine-grained distinction has served to advance both theory and description.

In this paper, we argue that a similar distinction should be made in the domain of nominal concord. Focusing specifically on case, we propose that what pretheoretically looks like case concord is actually derived via two distinct underlying mechanisms. The first mechanism we will continue to refer to as “case concord”; the second we will label “case iteration.” These two phenomena yield similar surface patterns, but arise via distinct derivations, resulting in distributional differences. We argue that concord is similar to agreement in that it involves case features being morphologically realized on multiple categorially distinct elements within the DP. This is similar to how agreement results in features of the nominal being realized both on the nominal and the verb. In contrast, case iteration involves the realization of multiple instances of a functional head, which we model as D, similar to how clitic doubling is the result of an instance of D realized in the verbal complex.

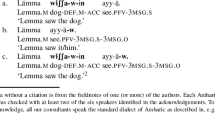

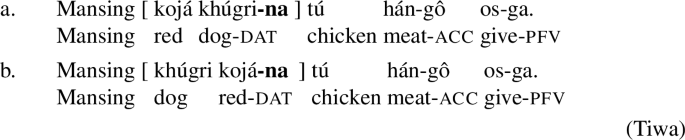

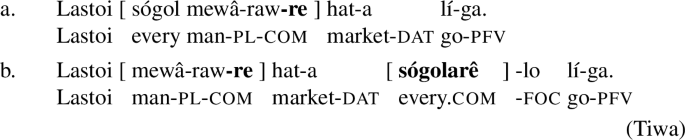

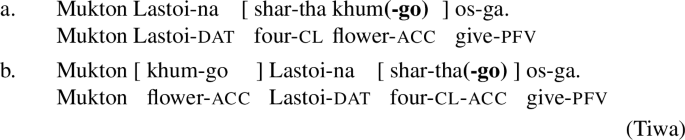

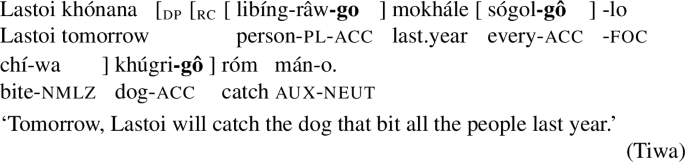

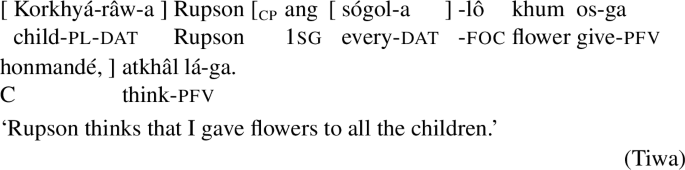

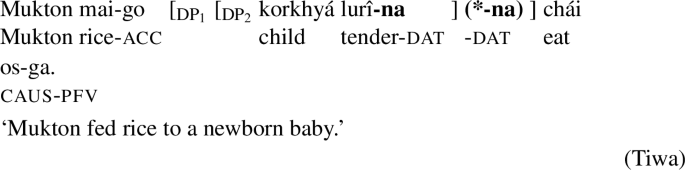

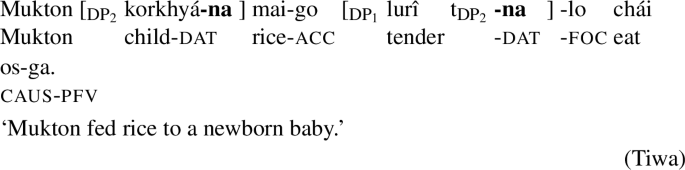

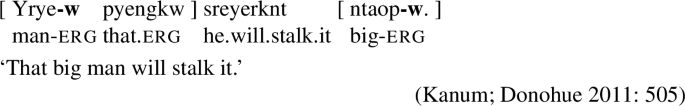

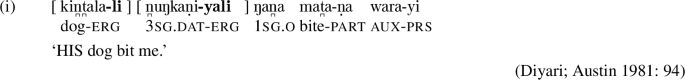

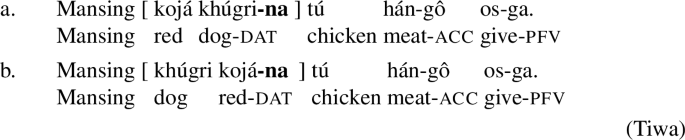

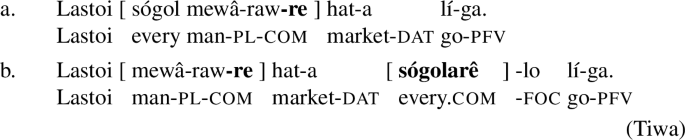

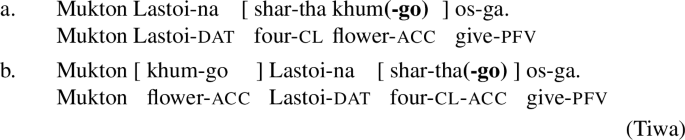

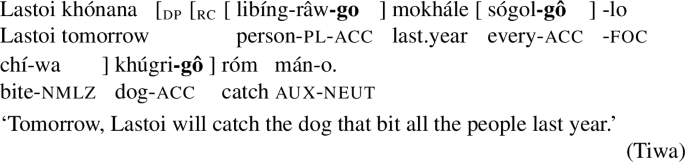

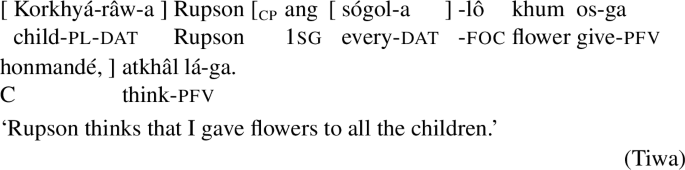

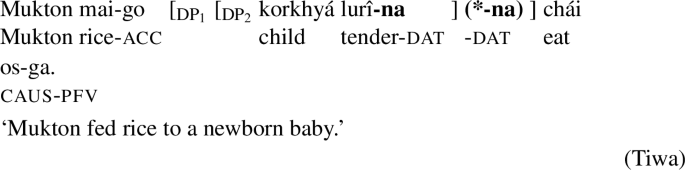

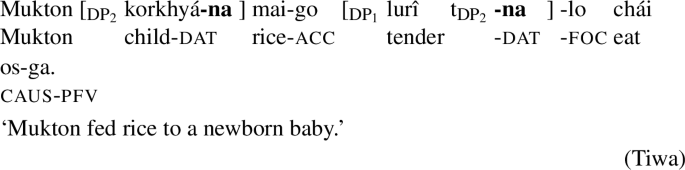

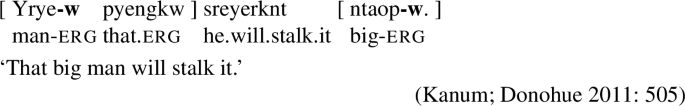

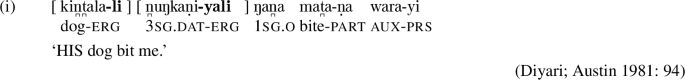

We argue for the existence of this separate phenomenon of case iteration primarily on the basis of novel data from original fieldwork on Tiwa (Tibeto-Burman; India). In Tiwa, case can only be realized once in a continuous DP; case concord is impossible. However, in discontinuous DPs, the two pieces of the DP match in case. This basic contrast is illustrated in (1).Footnote 1

-

(1)

‘Mukton fed rice to a newborn baby.’

In (1a), dative case surfaces as an enclitic on the adjective lurî ‘tender,’ which is the final element of the DP. In (1b) we see that it is ungrammatical for the noun korkhyá ‘child’ to also bear dative case in a continuous DP. However, the situation is reversed in a discontinuous DP. In (1c), we see that both the noun and adjective surface with dative case when they form a discontinuous DP, and (1d) shows that it is ungrammatical for case marking to be left off of the noun. We take this concord-like pattern that occurs only under discontiguity to be indicative of the phenomenon of case iteration.

We argue that case iteration does not arise via the mechanisms traditionally assumed to underlie concord. In particular, case iteration is not the morphological realization of case features on categorially distinct elements such as adjectives and nouns. Instead, we propose that case iteration arises when DPs contain nested DP shells, where the head of each DP is spelled out as an instance of case. Thus, in a language like Tiwa, case is only ever realized on D. We argue that this is the key to understanding the empirical differences between a language like Tiwa, which allows case matching only in discontinuous DPs, and languages having canonical case concord, which display concord even within continuous DPs.

In making this argument for case iteration, we first outline the properties of Tiwa discontinuous DPs and the case matching patterns we find in Sect. 2. We then briefly consider languages with true concord in Sect. 3 and outline why theories of concord cannot easily be extended to cover the Tiwa data. In Sect. 4 we lay out our analysis of case iteration, which involves a DP shell structure and feature sharing between nested instances of D. We illustrate how this analysis can account for the basic Tiwa pattern as well as instances of differential object marking and case stacking. After making our main argument, we then turn our attention to the larger picture beyond Tiwa. In Sect. 5 we discuss data from original fieldwork on an unrelated language, Amahuaca (Panoan; Peru), and demonstrate that a similar pattern of case matching in this typologically different language can also be accounted for under our DP-shell analysis. In Sect. 6 we zoom out even further, considering the crosslinguistic picture of case iteration and other possibly related phenomena. Sect. 7 offers concluding remarks about the concord/case iteration distinction and the empirical signature of each phenomenon.

2 Case matching in Tiwa

In this section, we introduce basic information about the morphosyntax of DPs in Tiwa as well as the pattern of case matching in discontinuous DPs in the language. We demonstrate that a variety of elements can be separated from the noun in a discontinuous DP and that case matching can occur with various case markers. We also show that while case matching is obligatory for the majority of discontinuous DPs, there are instances of case-marking mismatches. We show that these mismatches are highly constrained, mirroring a more general pattern of differential object marking in the language.

2.1 Tiwa nominals and case marking

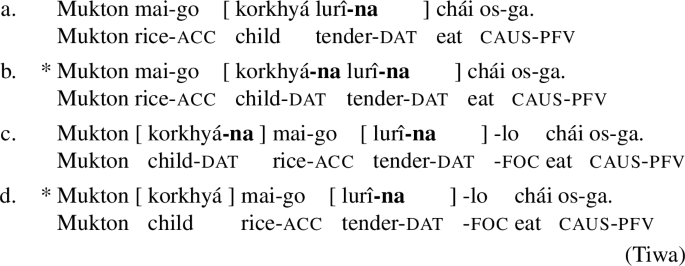

Tiwa is a Tibeto-Burman language spoken primarily in Assam, India by approximately 33,900 speakers.Footnote 2 Data presented here were collected by the second author through work with three speakers between 2015 and 2022 in Umswai, Karbi Anglong district, Assam, and in 2020–21 via WhatsApp with one of those speakers. Tiwa is a head-final language with accusative alignment. The basic SOV order can be obscured by scrambling, as seen in (2).

-

(2)

‘Mukton saw Tonbor.’

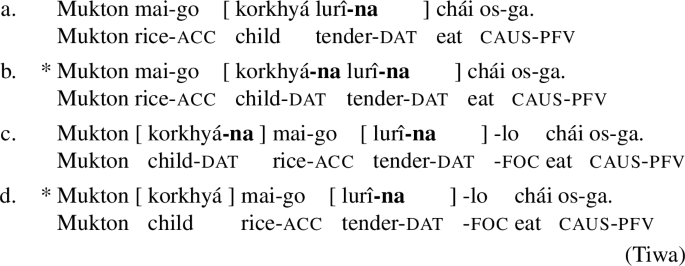

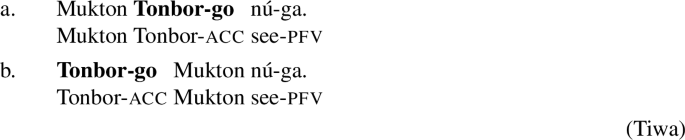

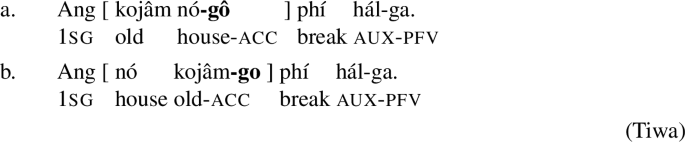

In (2a) we see the basic SOV order of the language, but in (2b) the object DP Tonborgo scrambles across the subject Mukton. The order of elements within a DP is also variable in Tiwa, but case always surfaces as an enclitic on the final element of the DP, as demonstrated in (3) and (4).

-

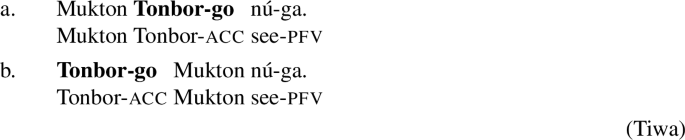

(3)

‘I tore down the old house.’

-

(4)

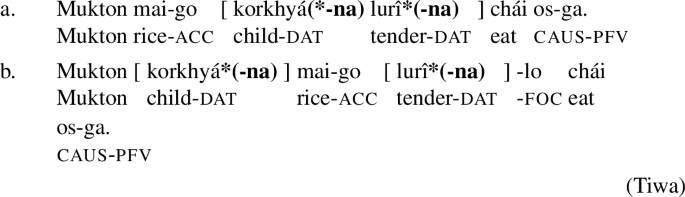

‘Mansing gave meat to the red dog.’

In (3a) the head noun nó ‘house’ is the final element of the DP and the accusative case marker surfaces on it. However, the order of the noun and adjective is switched in (3b) and here the accusative case marker surfaces on the adjective kojâm ‘old’ instead. The same pattern holds for dative case in (4). In (4a) the dative case marker surfaces on the noun khúgri ‘dog,’ which is final in the DP, while in (4b) the order is reversed, and dative surfaces on kojá ‘red.’ Like adjectives, numerals, quantifiers, and relative clauses can appear before or after the head noun (Dawson 2020: 45–46). Demonstratives, indefinite articles, and possessors must appear before the head noun, but show variable order among themselves and with quantifiers, which can precede these elements. In all instances, case is realized on the right-most element. The consistent DP-final position of case suggests that case is realized in the position of a high functional head in the nominal, which we will model as D.Footnote 3

Note that the variability in word order of both DPs within the clause and elements within the DP does not clearly track traditional information structural categories such as focus and topic. As discussed below, Tiwa marks information structure through enclitics on the DP, which we assume are adjoined to DP and not associated with a particular structural position within the clause.

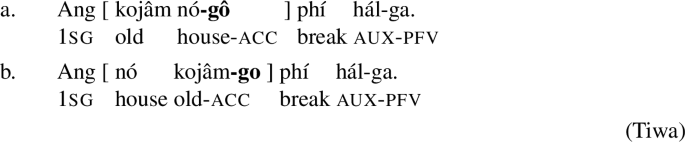

2.2 Case matching in discontinuous DPs

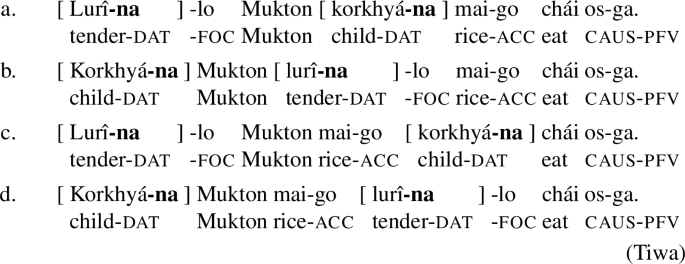

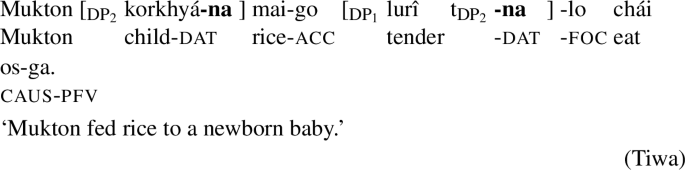

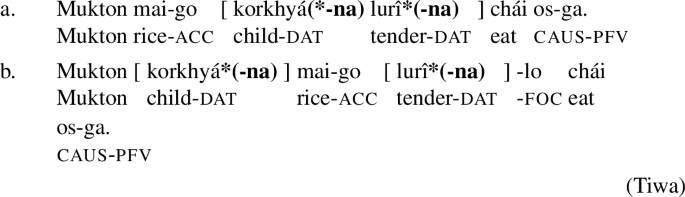

There is no case concord in continuous DP structures in Tiwa, as can be seen in (5a), where it is ungrammatical for the dative marker -(n)a to surface twice in the DP.Footnote 4 This case marker can only appear on the adjective lurî ‘tender,’ which is the final element in the DP, not on the noun korkhyá ‘child.’ However, Tiwa allows various modifiers that are typically DP-internal to surface non-adjacent to the noun of their DP. In such discontinuous DPs, the modifier and noun match in case, as seen in (5b), where both lurî and korkhyá surface with dative case.Footnote 5

-

(5)

‘Mukton fed rice to a newborn baby.’

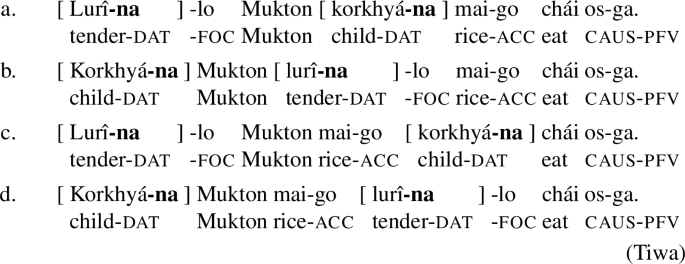

In discontinuous DP structures in Tiwa, both elements behave like independent DPs. As seen in (5b), they can both be case-marked, with the case enclitic surfacing at the end of each element. Additionally, both elements of a discontinuous DP can undergo scrambling independently, as illustrated in (6). In (6a), the adjective lurî has scrambled over the subject, while in (6b), the noun has scrambled over the subject. Additionally, (6c) and (6d) show that the two pieces of the discontinuous DP can be separated by more than one constituent.Footnote 6

-

(6)

‘Mukton fed rice to a newborn baby.’

The usual position for the separated modifier in a discontinuous DP is immediately before the verb, structurally lower than the head noun. However, this is a tendency, rather than a requirement. As seen in (6a) and (6c), it is possible for the modifier to scramble to a higher position in the structure.

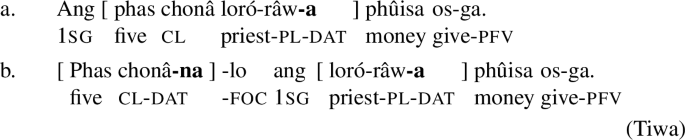

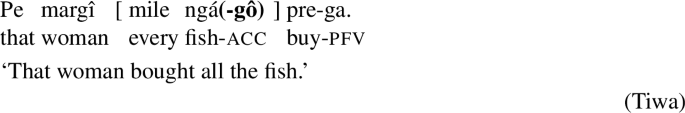

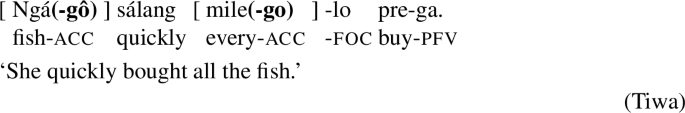

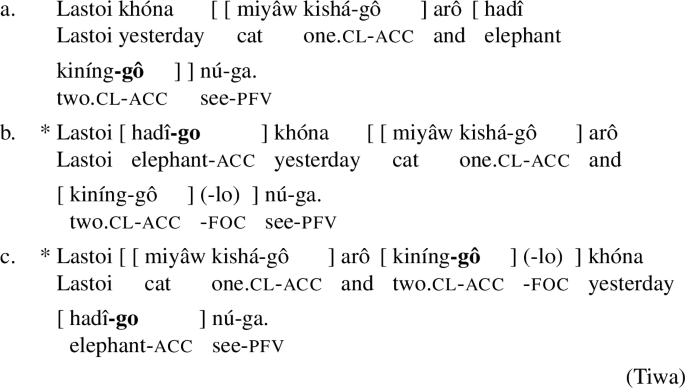

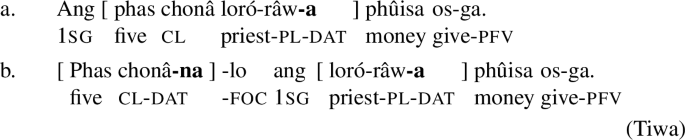

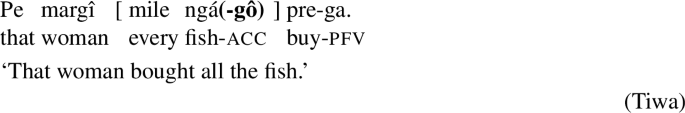

The pattern of case matching only under discontiguity is possible with any modifier that can be separated from the head noun in a discontinuous DP. This was illustrated for an adjective by the pair in (5). The same pattern is also found for numerals, (7); quantifiers, (8); relative clauses, (9); demonstratives, (10); indefinite articles, (11); and possessors, (12).

-

(7)

‘I gave money to five priests.’

-

(8)

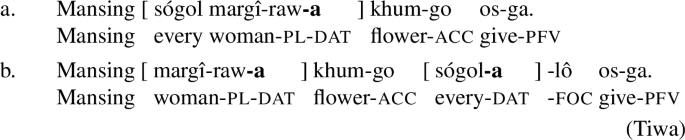

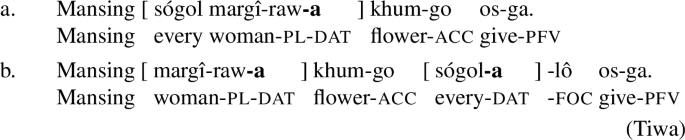

‘Mansing gave flowers to every woman.’

-

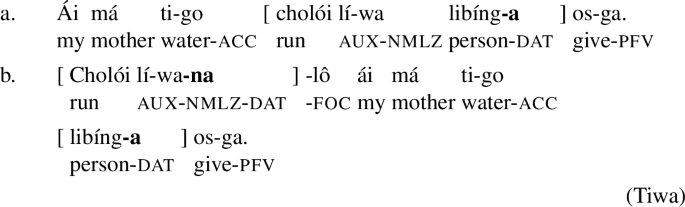

(9)

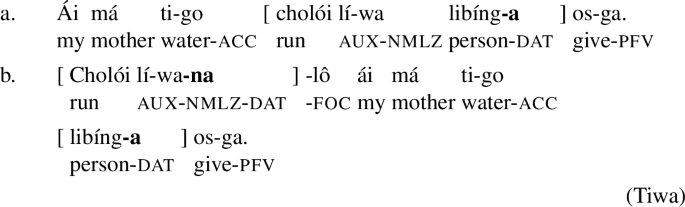

‘My mother gave water to the man that was running.’

-

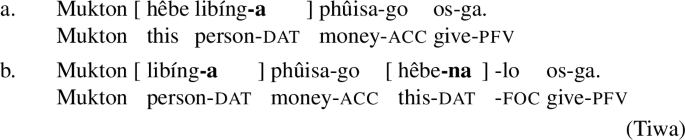

(10)

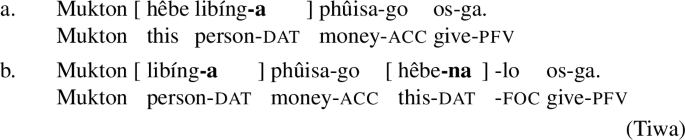

‘Mukton gave money to this person.’

-

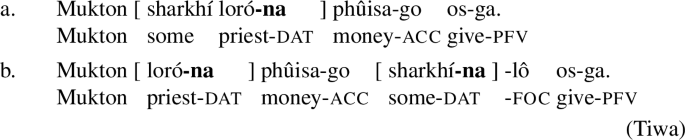

(11)

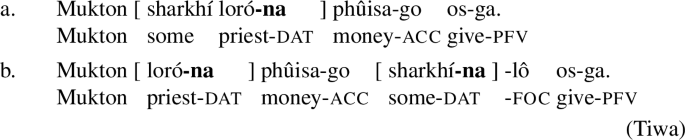

‘Mukton gave money to some priest.’

-

(12)

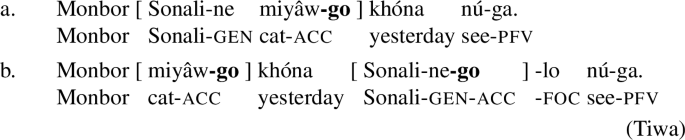

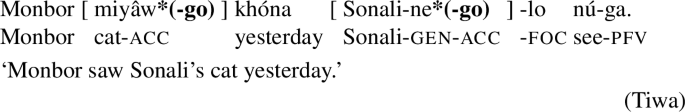

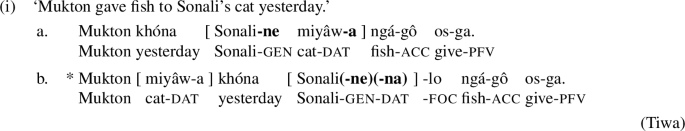

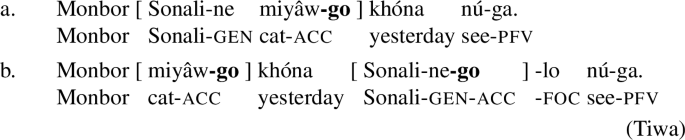

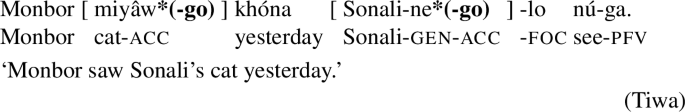

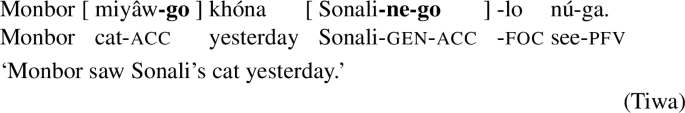

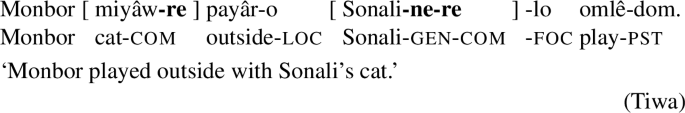

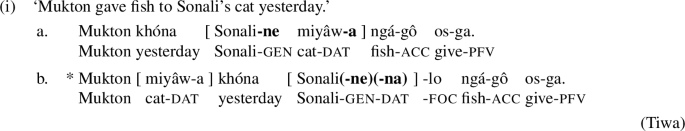

‘Monbor saw Sonali’s cat yesterday.’

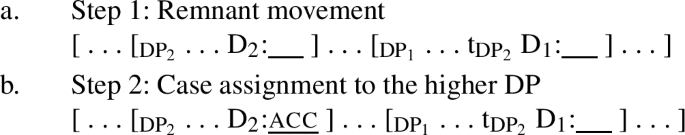

In (7b), we see that the numeral phas chonâ ‘five’ receives dative case, as does the noun lorórâw ‘priests.’ Likewise, in (8b), the quantifier sógol ‘every’ receives dative case, as does the noun margîraw ‘women.’ The sentence in (9b) contains a relative clause cholói líwa ‘that ran.’Footnote 7 This relative clause receives dative case, as does the head noun libíng ‘person.’ (10b) shows that both the head noun libíng ‘person’ and the demonstrative hêbe ‘this’ receive data case under discontiguity. (11b) likewise shows that the noun loró ‘priest’ and the indefinite article sharkhí ‘some’ receive dative.Footnote 8 Finally, in (12b), Sonali, which already has genitive case due to the fact that it is a possessor, receives additional accusative case marking, as does the noun miyâw ‘cat.’Footnote 9

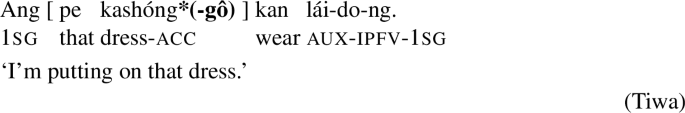

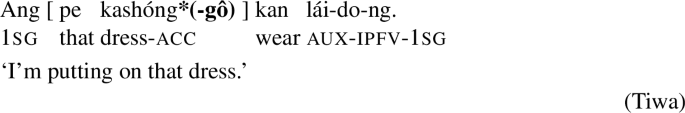

So far, the case matching examples we have considered have almost all involved the dative case marker -(n)a. However, matching in discontinuous DPs occurs with other case markers as well, including nominative, which is unmarked, (13); accusative -gô, (14); genitive -(n)e, (15); and comitative -rê, (16).

-

(13)

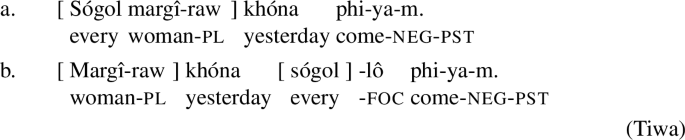

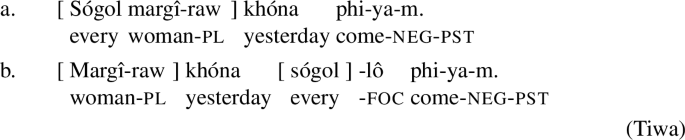

‘Every woman didn’t come yesterday.’

-

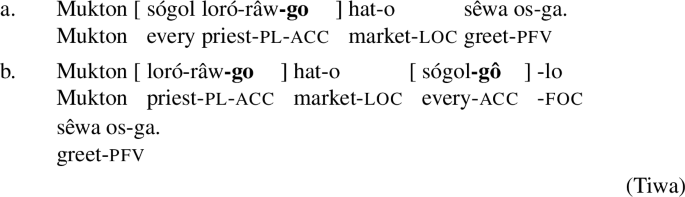

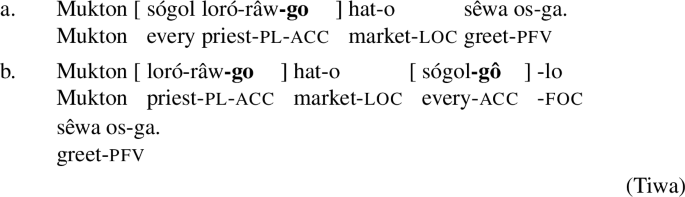

(14)

‘Mukton greeted every priest in the market.’

-

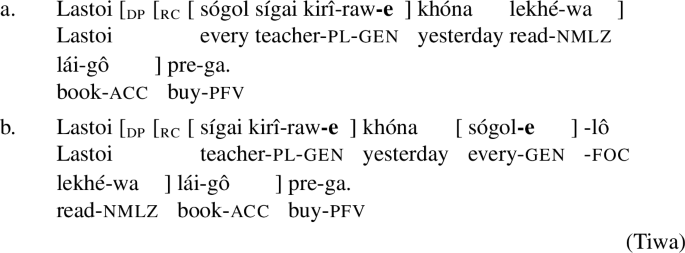

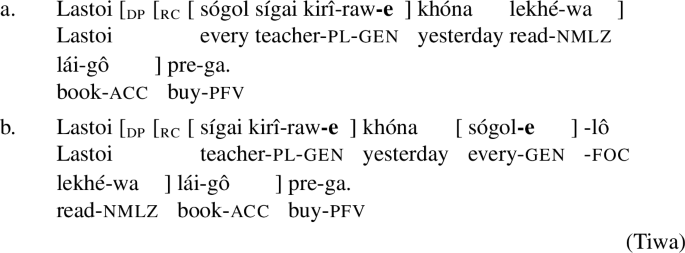

(15)

‘Lastoi bought the book that every teacher read yesterday.’

-

(16)

‘Lastoi went to market with every man.’

In (13b), both pieces of the discontinuous DP are unmarked for case. This is expected since the entire DP is nominative, which has no overt phonological realization in Tiwa. In (14b), the noun lorórâw ‘priests’ and the universal quantifier sógol both surface with the accusative case marker. The examples in (15) each contain a non-finite relative clause with a genitive-marked subject. In (15b), the subject DP is split within the relative clause so both the noun sígai kirîraw ‘teachers’ and the quantifier sógol bear genitive case. Finally, in (16b), the noun mewâraw ‘men’ and the corresponding quantifier both surface with comitative case.

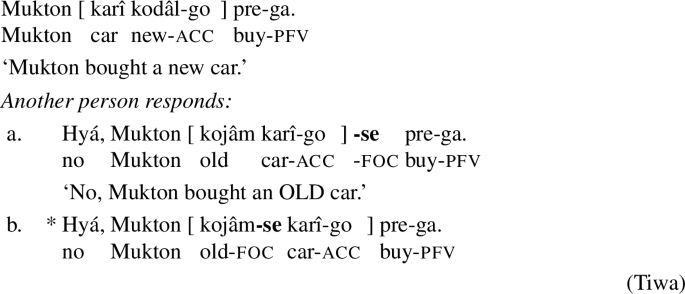

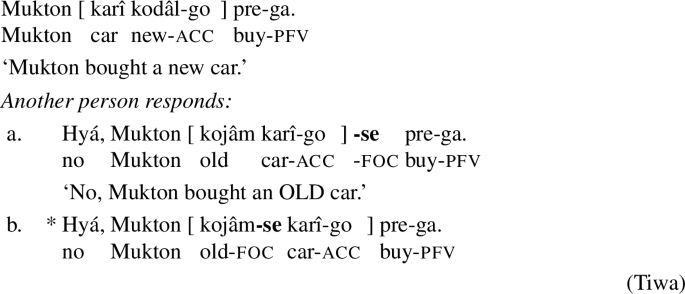

Finally, as the examples above show, the discontinuous modifier is typically focus-marked, usually with the information focus clitic -lô. This feature of discontinuous DPs in Tiwa is not surprising from a crosslinguistic perspective. It has been shown for many languages that discontinuous DPs provide a way of conveying different information structural statuses for different subparts of a single noun phrase (see Reinholtz 1999; De Kuthy 2002; Fanselow and Féry 2006; among many others). In Tiwa, focus is marked with enclitics that adjoin to the DP, to the right of any case marking. None of these clitics can appear on a subconstituent within the DP, even when that subconstituent is narrowly focused. This is shown in (17), with the contrastive focus clitic -sê, which is often used in corrective contexts. In this example, one speaker states that Mukton bought a new car. Another speaker wishes to correct the first speaker by clarifying that Mukton bought an old car. (17a) shows that the speaker can do this by cliticizing the contrastive focus clitic to the entire object DP. (17b) shows that it is ungrammatical for this clitic to appear directly on the corrected adjective.

-

(17)

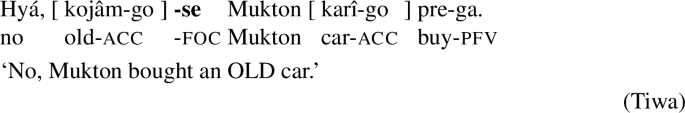

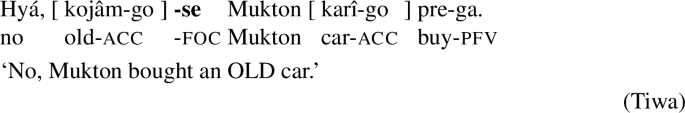

Discontinuous DPs provide a way of unambiguously signaling which part of the DP is focused. This is shown in (18), which also serves as a corrective response to the speaker’s original statement in (17). Here the corrected adjective is separated from the head noun and surfaces with its own case marking. The contrastive focus clitic can now be directly cliticized to this constituent.

-

(18)

As a response to (17):

While the vast majority of discontinuous DPs involve a two-way split with focus marking on one of the two pieces, speakers also accept three-way splits in the right information structural contexts. For instance, the sentence in (19) is accepted in contexts where a previous speaker has mistakenly identified Ruphadoi as buying red pháskais (a type of traditional Tiwa clothing). This speaker corrects the color with the contrastive focus marker -sê and adds the additional new information of how many pháskais with the general information focus marker -lô. The noun pháskai remains unmarked, as it is old information. Each of the three pieces of the discontinuous DP in this sentence surfaces with accusative case marking.

-

(19)

We assume that, in principle, further splits could be possible, though this would perhaps require a context that is too complicated to result in pragmatic felicity.

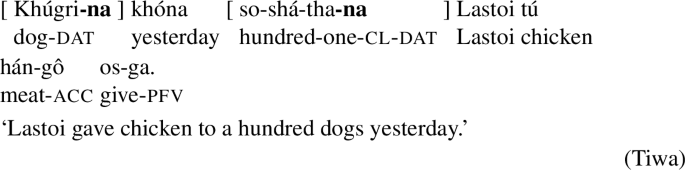

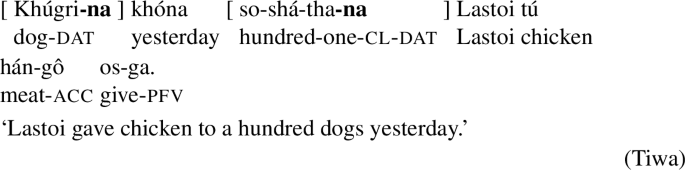

Finally, while focus marking of the discontinuous modifier is typical, it is also possible for the separated modifier to appear without focus marking, as seen in (20) where the numeral soshátha ‘one hundred’ surfaces with dative case marking, but not focus marking.

-

(20)

Given this, and the fact that discontinuous DPs are not required in cases of narrow focus, as in (17a), we assume that the mechanism for deriving discontinuous DPs is not directly triggered by information structural marking, but is instead generally available. Narrow focus simply provides a frequent functional motivation for this mechanism to be applied.

2.3 Case mismatches in discontinuous DPs

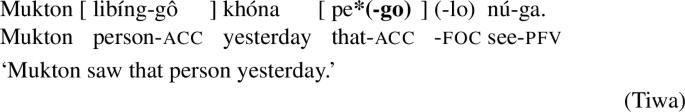

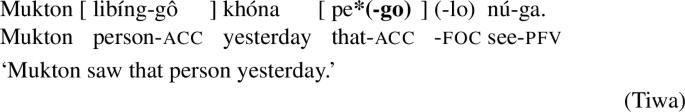

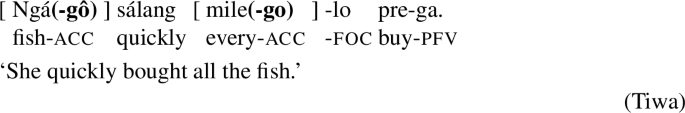

All examples of discontinuous DPs discussed so far have shown case matching between the head noun and stranded modifier(s). There is a pattern in Tiwa that at first glance appears to be an exception to the generalization that case matching always occurs under discontiguity: accusative case matching is seemingly “optional” in some sentences, as in (21).

-

(21)

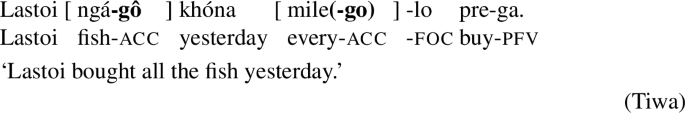

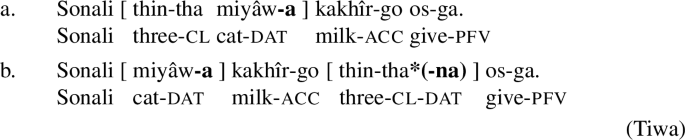

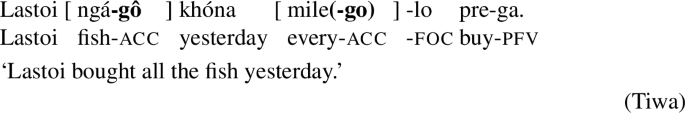

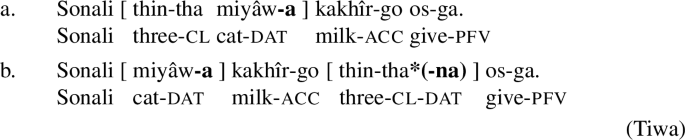

In (21), the noun ngá ‘fish’ shows accusative case marking while the stranded quantifier mile ‘every’ can surface without case marking. This apparent optionality is only found with accusative case; case matching with other case markers, like dative, is obligatory, as shown in (22).

-

(22)

‘Sonali gave milk to three cats.’

That case mismatching is only possible with accusative case is not entirely surprising given that Tiwa exhibits differential object marking (DOM). An example of DOM is given in (23), which shows that the object ngá ‘fish’ can appear either with or without accusative case marking.

-

(23)

DOM in Tiwa is sensitive to a number of factors including animacy, definiteness, and specificity (see Bossong 1991; Aissen 2003; among many others). What is interesting from the perspective of the current discussion is that the patterns of accusative case marking in discontinuous DPs are exactly as we would expect if both pieces of a discontinuous DP are independent DPs eligible for separate case assignment.

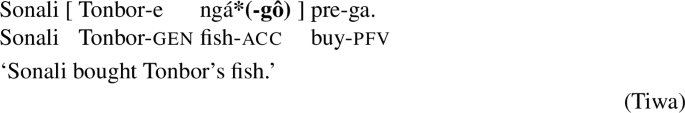

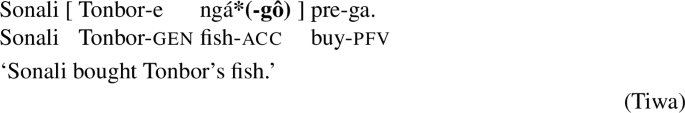

Specifically, if a continuous object DP must be marked with accusative case, so too must both pieces of the resulting discontinuous DP if that DP is split. For example, possessed object DPs must always surface with accusative case. This is true for continuous DPs, as in (24), and also for both the noun and possessor when they form a discontinuous DP, as in (25).

-

(24)

-

(25)

The same pattern holds for demonstratives. (26) shows that objects with demonstratives must be marked accusative. (27) shows that the demonstrative in a discontinuous object DP must likewise surface with accusative case.

-

(26)

-

(27)

In contrast, DPs that do not require accusative case marking when continuous also do not require accusative case when discontinuous. For instance, continuous DP objects with quantifiers can appear without accusative case marking, as in (28). The same holds for discontinuous DPs with quantifiers, as shown in (29) and in (21) above. Note that all four case marking possibilities are attested for example (29): both pieces can be unmarked, both can be marked, and either piece can be marked while the other remains unmarked.

-

(28)

-

(29)

The same pattern holds for objects modified by a numeral. (30a) shows that a numeral-modified object can appear without accusative case. (30b) shows that the numeral can be unmarked when discontinuous as well.

-

(30)

‘Mukton gave Lastoi four flowers.’

Note that there is a loose correlation between accusative case marking and structural height within the clause. In particular there is a general preference for overt case marking on objects that appear to the left of adverbs or other arguments. This pattern is reflected in discontinuous DPs, where speakers prefer overt case marking on pieces that are higher in the structure. Note, however, that while accusative case marking in Tiwa is typically associated with DPs that appear in a structurally higher position than unmarked DPs, a purely structural account of DOM in Tiwa faces empirical challenges as unmarked objects can appear higher than the subject in some instances (Dawson 2020).

2.4 Summary

In this section, we have seen that Tiwa allows discontinuous DPs and that each element of a discontinuous DP behaves like an independent DP. Interestingly, the majority of these discontinuous DPs display case matching even though this same type of case concord is not possible internal to a continuous DP constituent. This pattern of case matching occurs with a variety of case markers and with any element that can be separated from the other DP elements in a discontinuous structure. The only exception to case matching is found with split object DPs, which may or may not match in accusative case marking. This pattern reflects a broader phenomenon of DOM in the language. With these basic facts in mind, we now turn to a discussion of previous proposals for analyzing case concord.

3 Theories of concord

Previous analyses of concord have been primarily concerned with languages that display concord in continuous DPs. The patterns of concord found in these languages are empirically distinct from the type of case matching found only in discontinuous DPs in Tiwa. We argue that analyses designed to account for DP-internal concord patterns cannot be straightforwardly extended to the Tiwa pattern.

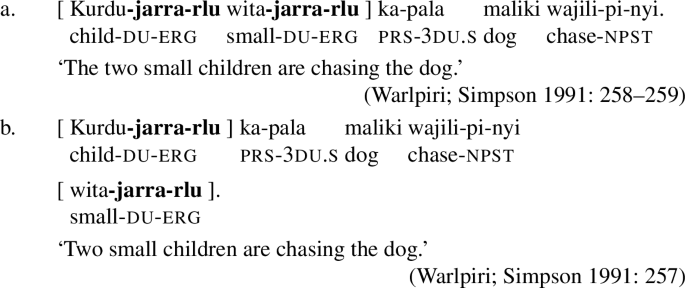

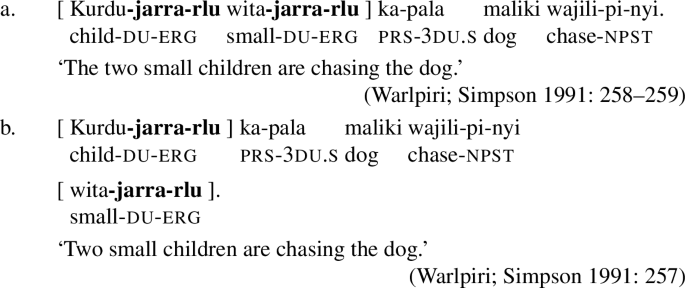

Languages like Warlpiri show concord internal to continuous DPs as well as in discontinuous DPs.Footnote 10

-

(31)

As seen in (31), multiple elements of the DP may surface with number and case marking. It is this type of DP-internal concord pattern that has been the subject of a majority of the literature on concord.

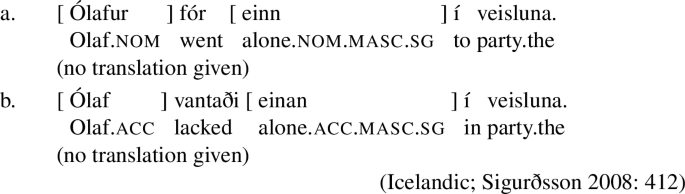

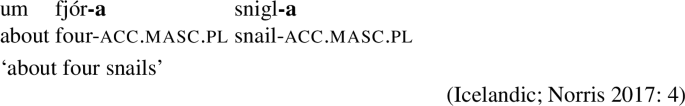

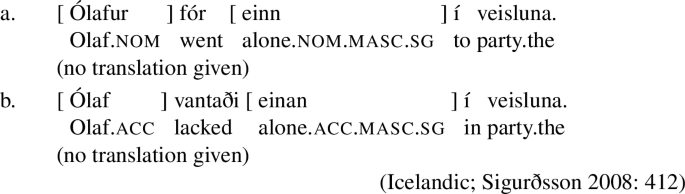

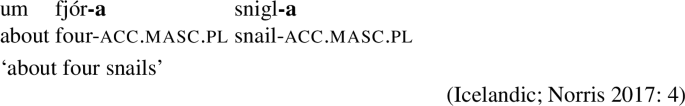

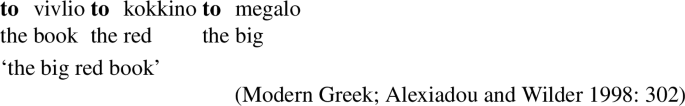

An additional pattern that some analyses of concord attempt to derive arises when elements that originate external to the DP also show concord to match features of the DP. This type of pattern can occur with elements such as predicative adjectives and secondary predicates in languages like Icelandic, Latin, Modern Greek, and Serbo-Croatian (Matushansky 2008). An example of this pattern with an Icelandic “semi-predicate” is given in (32).

-

(32)

Here we see that the semi-predicate meaning ‘alone’ surfaces in the nominative, masculine, singular form einn to match the nominative subject Ólafur in (32a). In (32b) it surfaces in the corresponding accusative form einan, showing concord with Ólaf. Crucially, Icelandic and other languages that show concord in predication structures also show concord internal to DPs as well, as shown in (33).

-

(33)

Various mechanisms for deriving concord internal to DPs as well as in predication have been proposed in the literature. Here we focus on analyses of case concord.Footnote 11 Two of the main families of analyses that have been proposed differ in how many instances of case assignment are taken to be involved in structures that show concord. Under one family of analyses, each overt reflex of case is the result of an independent instance of case assignment. Under the second family of analyses we will consider, case is assigned only once, with additional morphological reflexes of case arising due to feature spreading.

The first family of views includes accounts such as that of Brattico (2008) and Matushansky (2008). Brattico (2008) follows Kayne (2002) in assuming that case is assigned to lexical items, not maximal projections. Thus, any lexical item that bears case is assigned case directly. In structures that show concord, multiple elements bear case morphology, and are taken to have been independently assigned case. Under Matushansky’s (2008) account, the domain of case assignment is the complement of the case assigner. For example, if v is taken to be the locus of accusative case assignment, the sister of v, that is, VP, will be the domain for accusative case assignment. Each case-bearing element in that domain is then assigned case.

The second family of views is represented by accounts such as that of Babby (1987) and Norris (2014). Babby (1987) argues that case is assigned to nominal maximal projections and percolates down through the nominal to all elements that can bear case and that have not already been assigned a different case internal to the nominal. Norris (2014) adopts a view of concord that is morphological in nature. Case is assigned to nominal maximal projections (KPs) in the syntax, but the realization of case on various DP-internal elements is due to operations that occur in the morphological component. Norris argues that an Agr0 node (Embick 1997) is inserted at the site of each concord-bearing element and that the case feature of the Agr0 node receives the value of the most local case-bearing head that dominates it.

Both families of analyses considered here have in common that they are designed to account for the possibility of multiple realizations of case internal to a continuous DP. This DP-internal case concord is not possible in Tiwa, as demonstrated in Sect. 2. It is unclear how to straightforwardly rule out case concord in continuous DPs while ensuring that case matching in discontinuous DPs is obligatory under either type of theory we have considered. If case matching is derived by assigning case to multiple items in the DP, it is unclear why this multiple case assignment can only occur in discontinuous structures. Likewise, if case is assigned once and then spread, it is not obvious why case feature spreading only occurs under discontiguity.

If we found the reverse of the Tiwa pattern in a language—case concord in continuous DPs, but a lack of concord in discontinuous DPs—we could easily salvage a traditional concord analysis by appealing to the order of operations. If the operation that results in concord were to apply fairly late in the derivation, the movement that splits a discontinuous DP could bleed concord. If case concord is the result of multiple instances of case assignment, multiple case assignment could be bled if one piece of the DP moved out of the domain where case was assigned prior to case assignment. This would be consistent with a view of case assignment as happening after at least some narrow syntactic operations like movement, perhaps as late as in the morphological component. If, instead, case concord results from case feature spreading throughout a DP, concord could be bled if the DP were to be split prior to this feature spreading. There would be no case in the piece of the DP that did not contain the head to which case was originally assigned. This type of view would be consistent with concord being a morphological operation, as argued for by Norris (2014). Therefore, no matter which type of theory we adopt, we could in principle derive a pattern where movement bleeds concord. The problem is explaining the reverse: the pattern we see in Tiwa would actually be an instance of movement feeding concord. This cannot be derived simply by reordering the operations of movement and concord. If the mechanism responsible for concord applied before splitting a DP, this should result in concord in both continuous and discontinuous structures. This is the Warlpiri pattern, but is simply not the pattern we see in Tiwa.

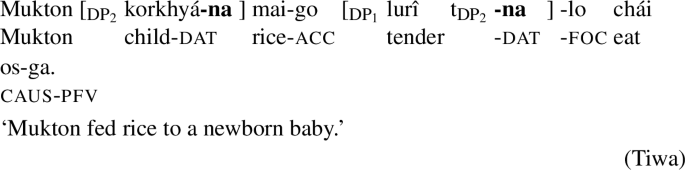

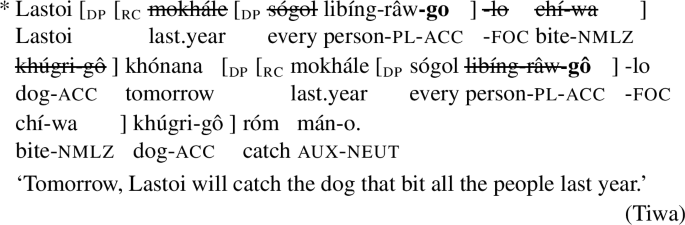

One way we might attempt to salvage a traditional concord analysis for Tiwa is by positing that the pattern of case matching only in discontinuous structures is a purely morphological pattern. That is, one might assume that the familiar type of DP-internal concord applies across the board in Tiwa but is simply blocked from surfacing in continuous DPs. This could potentially be operationalized as some type of constraint or rule that forbids the pronunciation of more than one instance of case in each structurally continuous portion of a DP (e.g. an impoverishment rule). However, the mechanism for choosing which instances of case to pronounce under such an analysis would need to be constrained. While case concord is ruled out in continuous DPs, as we demonstrated in Sect. 2, multiple instances of case can surface within a DP, provided that DP contains additional clausal structure. For example, in relative clauses, DPs internal to the relative clause are case-marked, as seen in (34).

-

(34)

Here the entire DP containing the relative clause is assigned accusative case, which is realized on the head noun khúgri ‘dog.’ No accusative case surfaces on the relative clause, even though relative clauses match their head noun in case when they are split from the noun to form a discontinuous DP. However, internal to the relative clause, accusative case does surface on the object. In fact, since the object of the relative clause is a discontinuous DP, accusative case surfaces on both the noun libíngrâw ‘people’ and the universal quantifier sógol. Thus, if the lack of concord in Tiwa is due to non-pronunciation of identical instances of case, this pronunciation algorithm must be able to differentiate between instances of case with different sources, namely case assigned internal to relative clauses versus at the matrix level.

The Tiwa pattern could potentially be captured by assuming that there is traditional concord plus a phase-bound case impoverishment rule that is bled by movement. The deletion rule would target all instances of case that were not final in a DP, and the fact that this rule would be sensitive to phases could account for realizations of case internal to relative clauses. If this rule were post-syntactic, it could be bled by the type of movement that splits discontinuous DPs, accounting for why each portion of the DP surfaces with an instance of case. However, this type of account has some shortcomings. First of all, it is incompatible with the order of operations proposed by Arregi and Nevins (2012). Under their account, impoverishment precedes linearization, but the type of impoverishment rule needed to account for Tiwa would have to identify the linearly final instance of case in a DP in order to spare it from deletion. Second, the fact that case is always realized as a DP enclitic in Tiwa is an accident under this morphological account. It is purely coincidental that the final instance of case is preserved in this strongly head-final language. Third, data from differential subject marking in Amahuaca (the topic of Sect. 5.3) make it clear that the higher element of a discontinuous DP must be independently eligible for case assignment. As will be discussed, these facts are difficult to capture without assuming that the higher element of the discontinuous structure is a full DP, which is not predicted by the morphological account.

Given these issues, we will not adopt this version of a morphological account here. However, in what follows we will draw on certain of its core ideas; in particular, we will argue that movement indeed creates the conditions for multiple instances of case that are always present to actually be spelled out. Under the account we will develop, movement has this effect not because it bleeds the application of an impoverishment rule, but because it splits apart two layers in a DP shell structure. If these layers were realized in a continuous structure, a morphological operation—haplology—would apply to block the multiple realization of case. (This operation, in contrast to impoverishment, applies only very locally, and may apply post-linearization.) This account improves on the impoverishment account by tying the case matching behavior of Tiwa to the fact that its case marker is a DP-level enclitic, surfacing in a position where we expect to find a head in this head-final language. Crucially, under the account we propose, the pattern of case matching only under discontiguity that we find in Tiwa is not merely a special instance of the familiar type of case concord, as an impoverishment account assumes. Instead, it reflects an empirically different phenomenon that arises as the result of spelling out multiple instances of D that each bear case.

4 The DP-shell analysis

An empirically adequate theory of case matching in discontinuous DPs in Tiwa should minimally be able to account for two key properties of the pattern. The first is that case matching is possible only under discontiguity in Tiwa. Case matching is entirely ruled out in continuous DPs, which, as we discussed in Sect. 3, is not predicted by existing theories of case concord. The second aspect of the Tiwa pattern that a theory should be able to account for is the fact that each piece of a discontinuous DP behaves like an independent DP. As discussed in Sect. 2, each piece of a discontinuous DP can independently undergo the type of scrambling that is available to DPs and each piece can bear case. We also saw that each piece of a discontinuous DP can be assigned accusative case independently in DOM contexts. We argue that both of these aspects of the Tiwa case matching pattern can be captured under an account that assumes that DPs contain multiple DP shells, the heads of which are spelled out as case. This is the phenomenon we refer to as case iteration. In the following sections we lay out our analysis and demonstrate how it can be leveraged to account not only for the basic facts in Tiwa, but also the more complicated pattern of DOM as well as instances of case stacking.

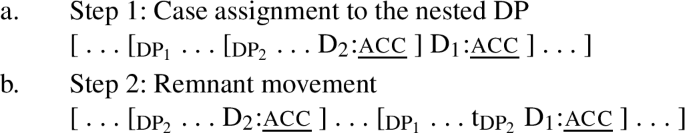

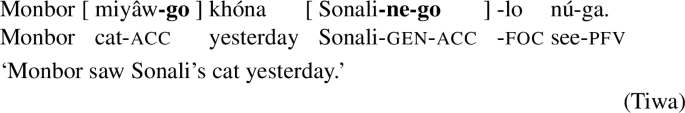

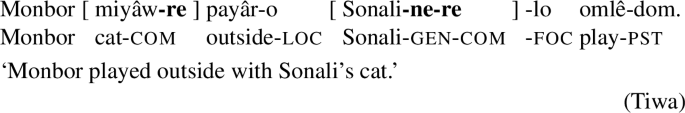

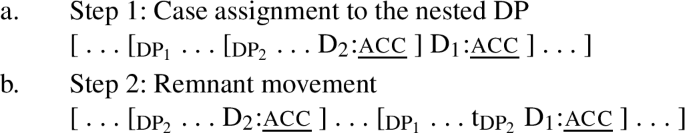

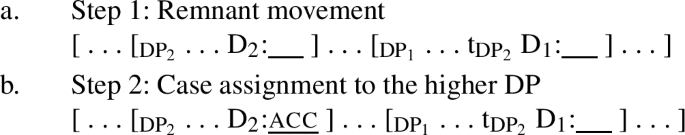

4.1 Analysis of basic case iteration in Tiwa

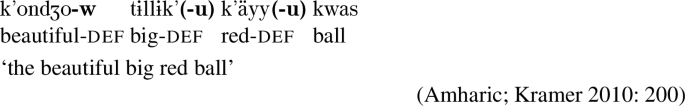

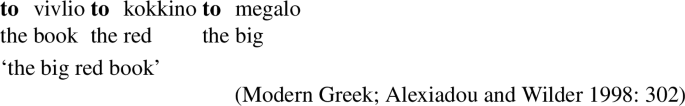

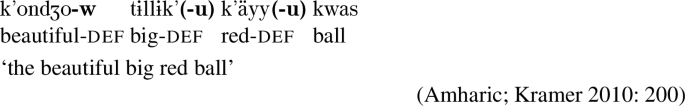

The analysis we put forth here assumes nested DP shells. What is important for our analysis is that the highest projection in the nominal constituent can iterate in a language like Tiwa. We specifically assume that D can recursively select another DP as its complement. It would also be possible to analyze this iteration as recursion of K in a KP-shell structure if K is taken to be the highest head in the extended nominal projection.Footnote 12 We choose to treat this shell structure as a DP shell structure because of connections to the other conceptions of multiple DP layers in analyses of phenomena such as clitic doubling (Torrego 1992; Uriagereka 1995) and polydefiniteness (Alexiadou and Wilder 1998; Lohrmann 2010; Panagiotidis and Marinis 2011; Lekakou and Szendrői 2012; Alexiadou 2014; Hankamer and Mikkelsen 2021; among others), which we return to in Sect. 6.Footnote 13

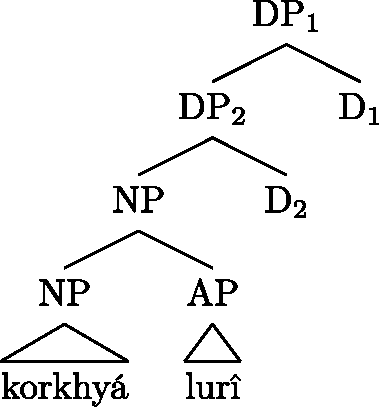

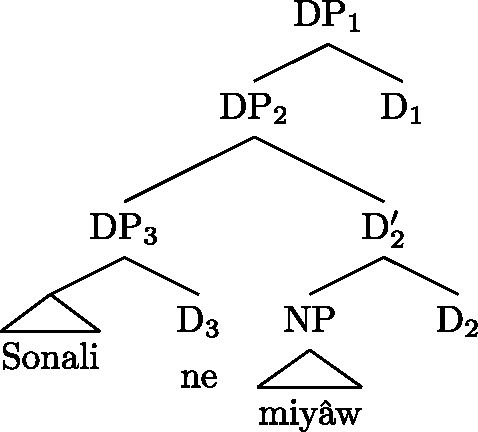

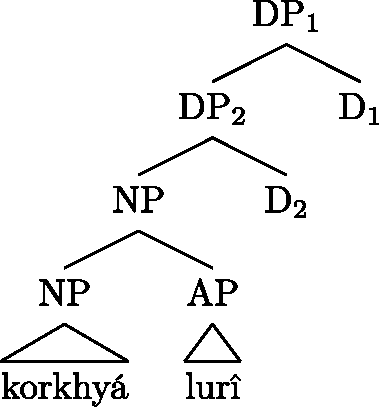

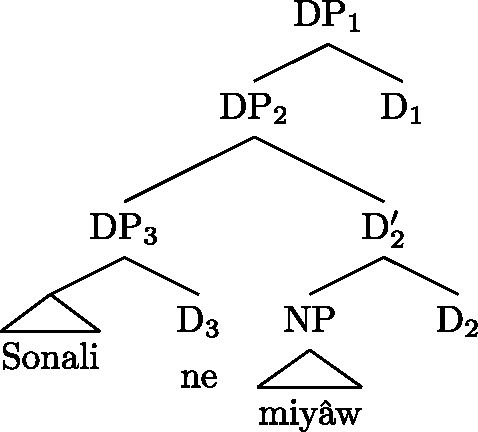

In a Tiwa DP that will be split to form a discontinuous constituent, there are multiple DP layers, as shown for the DP korkhyá lurî ‘newborn baby’ in (35).

-

(35)

In (35), D1 selects DP2 as its complement. This leads to a structure where DP1 serves as an outer DP shell to DP2. The complement of D2 is an NP. The NP korkhyá also has an AP adjunct lurî.

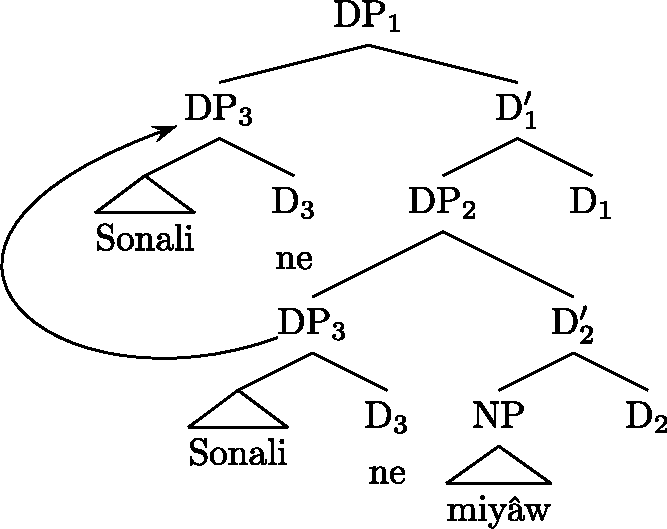

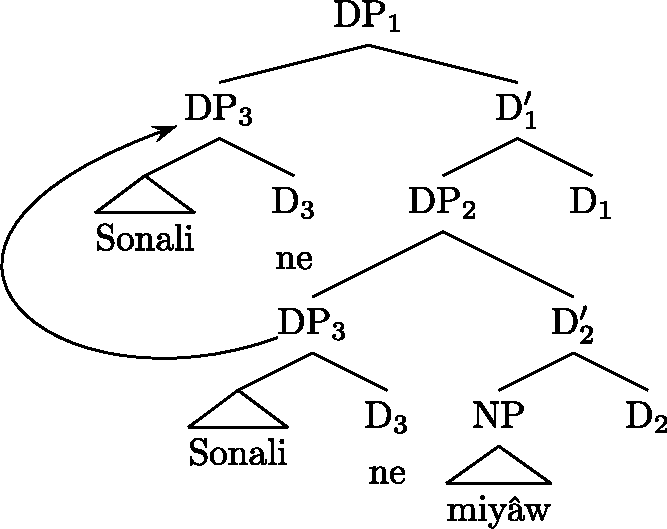

We argue that discontinuous DPs in Tiwa result from the movement of a subconstituent of a lower DP to the specifier of a higher DP, followed by remnant movement of the lower DP. First, the element that will be stranded, in this case the AP, undergoes movement to the specifier of the higher DP, as illustrated in (36).Footnote 14

-

(36)

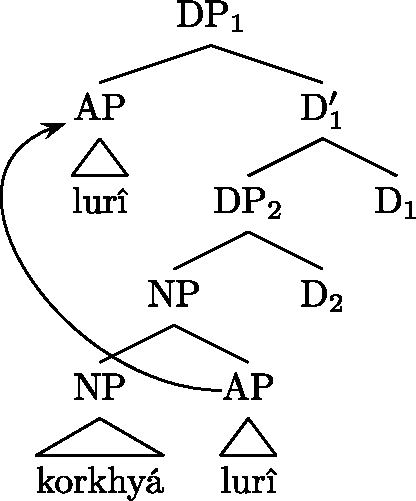

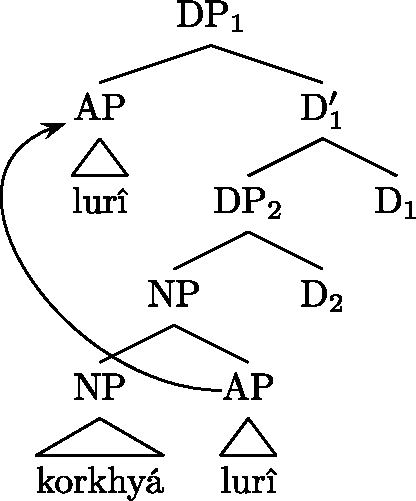

After the AP has moved to Spec,DP1, DP2, which contains the noun, can undergo remnant movement to a position higher in the clausal spine, stranding the AP in DP1. This remnant movement results in discontinuous DPs like the one in (37).

-

(37)

Here, DP2 contains the NP and an instance of D, and DP1, which remains lower in the structure, contains the previously moved AP as well as an instance of D. This means that there are two instances of D that are linearly non-adjacent. In this structure, both instances of D expone case and they both surface as the dative marker -na, resulting in the pattern of case matching. Instances where a DP is split into more than two pieces would be derived by positing additional DP shells with movement to the specifier of each DP and multiple instances of remnant movement. Since each piece would contain an instance of D, all pieces of the DP could match in case.

Evidence that the pieces of a discontinuous DP are related via movement and not via base-generation comes from islands. First, note that discontinuous DPs in Tiwa can be split across a finite clause boundary, as expected given that continuous DPs can scramble from a complement clause into the matrix clause (Dawson and Deal 2019). This is shown in (38), which shows a split between the head noun korkhyárâw ‘children’ and its modifier sógol ‘every.’ While the modifier appears in the complement clause, the head noun has undergone long-distance scrambling into the matrix clause.

-

(38)

That part of a discontinuous DP can scramble across a finite clause boundary shows that discontiguity is not subject to general clausal locality constraints.

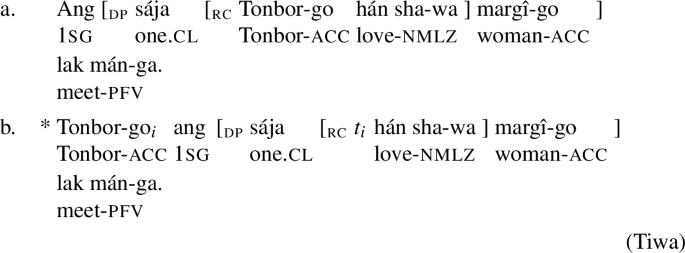

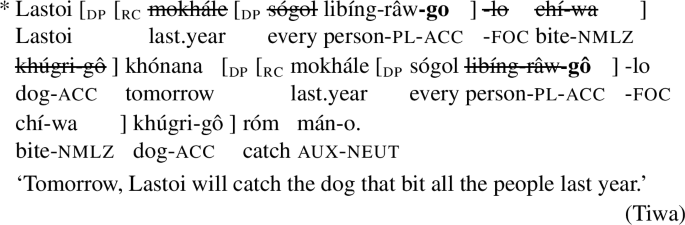

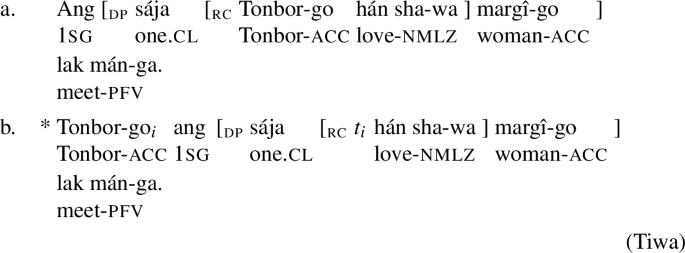

While discontinuous DPs can be split across a finite clause boundary, they cannot be split across a syntactic island. Relative clauses are syntactic islands in Tiwa. As (39) shows, elements that originate inside a relative clause cannot be scrambled out.

-

(39)

‘I met a woman who loves Tonbor.’

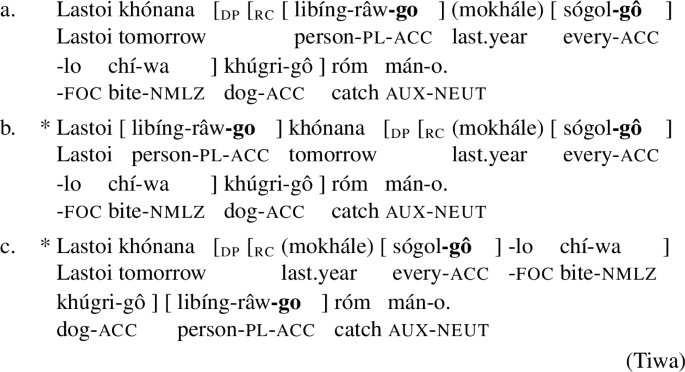

Similarly, in discontinuous DPs, a noun cannot be separated from its modifier across the boundary of a relative clause island, as demonstrated in (40).

-

(40)

‘Tomorrow, Lastoi will catch the dog that bit all the people (last year).’

As seen in (40a), discontinuous DPs can occur inside relative clauses. Here, the modifier sógol ‘every’ is separated from the noun libíngrâw ‘people.’ (40b) and (40c) show that when the noun libíngrâw appears outside of the relative clause, the result is ungrammatical. The fact that a quantifier and its restrictor cannot be separated by a relative clause boundary to form a discontinuous DP suggests that discontinuous DPs in Tiwa are derived via movement.

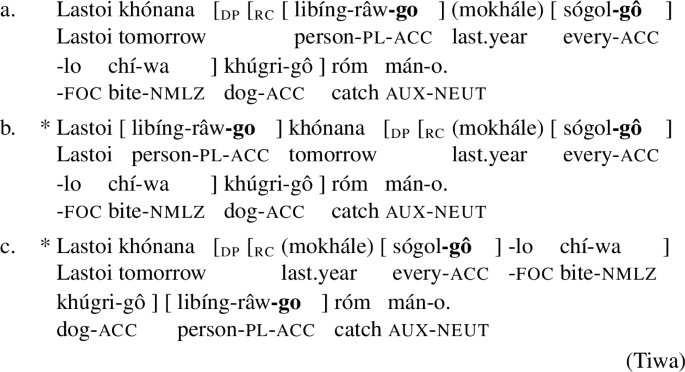

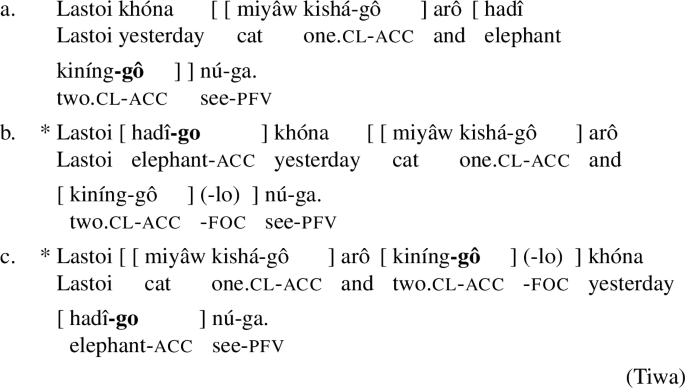

These facts also hold of coordinate structures, as shown in (41). In (41a), two object DPs are coordinated. (41b) and (41c) show that the noun hadî ‘elephant’ from the second conjunct cannot appear outside of the coordinate structure to form a discontinuous DP with its modifier kiníng ‘two.’

-

(41)

‘Lastoi saw one cat and two elephants.’

In summary, then, the pattern is that when the pieces of a discontinuous DP are related across an island boundary, the result is ungrammaticality. This suggests that the pieces of discontinuous DPs in Tiwa are related via movement rather than base generation.Footnote 15

It is, in theory, possible to derive a pattern like island sensitivity without assuming that the two pieces of a discontinuous constituent are generated as a single continuous DP if, for instance, there are locality constraints on the generation of two DP constituents that are to be construed as constituting a single thematic argument. A concrete proposal for how to implement such a restriction has been offered by Ott (2012) to account for German split topicalization. Ott argues that split topicalization structures involve two nominal constituents that begin in a bare predication structure as {DP,NP} or {DP,QP}. Because this predication structure cannot be labeled, one of the two subconstituents has to move to a higher position to break the symmetry and allow for labeling. Because the two pieces of a split topic originate as part of the same predication structure, splits show locality effects such as island sensitivity. However, because the two pieces do not originate as a single DP, this account makes several desirable predictions for German. Both pieces of a split topic should be able to contain a distinct noun, splits should be able to show orders or combinations of elements that are not possible in a single continuous DP, and there should be restrictions on the referential properties of the pieces of the split topic since one must be able to be a predicate.

However, none of these predictions hold for Tiwa. Crucially, in Tiwa, only elements that can form an acceptable continuous DP can be split to form a discontinuous DP. Given the number of empirical differences between discontinuous DPs in Tiwa and the split topicalization structures discussed by Ott (2012), we assume that these instantiate two different types of constructions and that locality restrictions on discontinuous DPs in Tiwa cannot be derived by appealing to a predication relationship between the two pieces. Therefore, we assume that the island sensitivity seen in Tiwa is truly evidence that the two pieces of a discontinuous DP originate as a single continuous DP that is subsequently split via movement.

With this understanding of how discontinuous DPs are derived, the question that remains is how a case iteration account can derive the empirical pattern of case matching only in discontinuous DPs. How do iterated instances of D come to bear the same case value and what blocks the realization of multiple instances of case in a continuous DP if iterated DP layers are possible? As in theories of DP-internal concord that argue that case is assigned to the highest head in the DP and then spread to other heads, we assume that case is assigned to the outermost D and then spread. However, this operation of feature spreading is significantly more constrained in Tiwa than it is in languages that exhibit concord in continuous DPs. In Tiwa, only iterated instances of D share case features. That is to say, this feature spreading is limited to configurations in which an instance of D selects a DP as its complement. Case concord is not a general process in the language and case cannot be spread to any other DP-internal elements. (This is why case is always realized as a DP enclitic rather than on a consistent element, such as the noun, in the DP.)

If a continuous DP contains multiple DP shells, case will be assigned to the outermost instance of D and then will spread to lower instances of D in a nested configuration like (35). However, in a head-final language like Tiwa, iterated instances of D will all be linearized to the right, thus resulting in linear adjacency between multiple instances of D, as schematized in (42). Since these adjacent instances of D are featurally identical, a process of morphological haplology ensures that only one instance will be pronounced (see Nevins 2012, and sources cited therein).Footnote 16 This rules out two or more adjacent instances of case marking at the end of continuous DPs, favoring instead the attested pattern of a single instance of case marking in continuous DPs, as shown in (42).

-

(42)

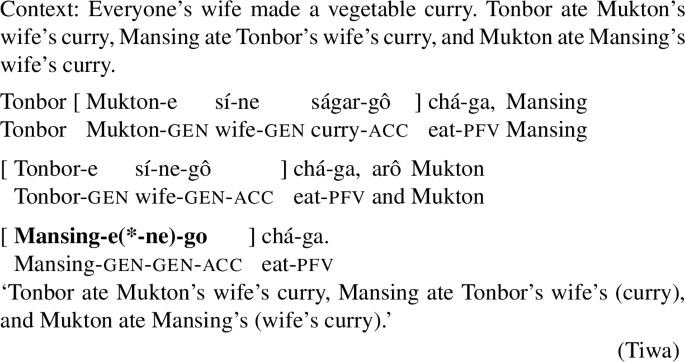

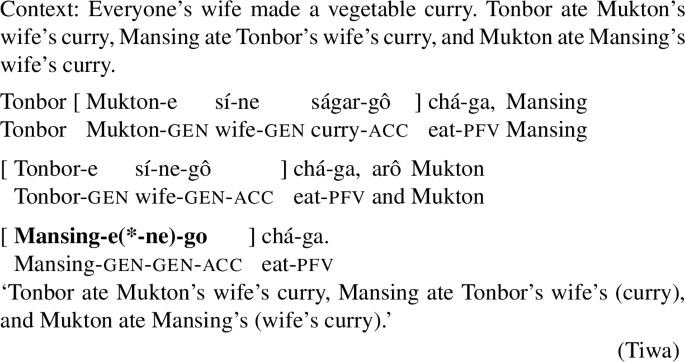

There are two distinct pieces of independent evidence for haplology of featurally identical, linearly adjacent case markers. The first of these comes from NP ellipsis, illustrated in (43).

-

(43)

In this sentence, NP ellipsis in the second clause eliminates ságar ‘curry,’ leading to a genitive-accusative sequence. In the third clause, NP ellipsis targets both ságar ‘curry’ and sí ‘wife.’ However, the result is not a genitive-genitive-accusative string, as we would expect if no haplology applied, but rather a genitive-accusative string.

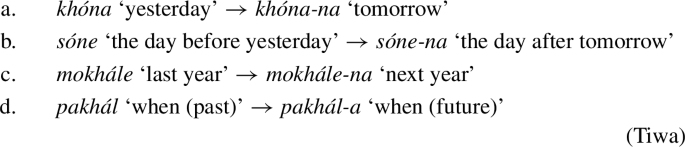

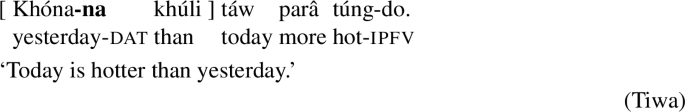

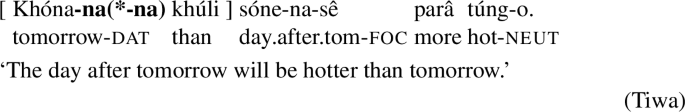

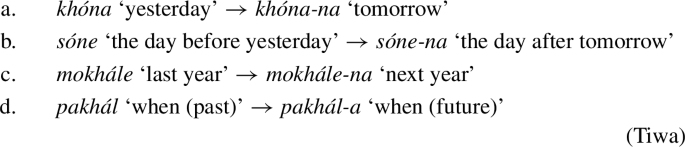

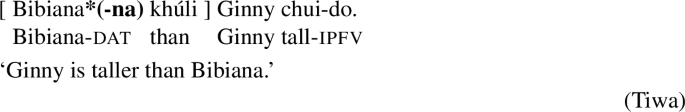

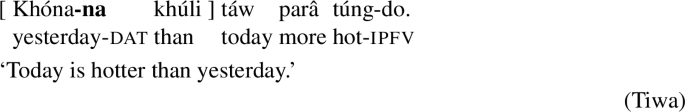

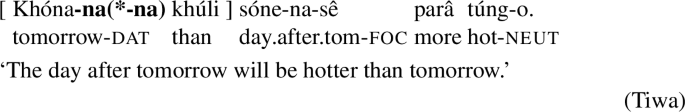

The second piece of evidence for haplology comes from the realization of dative case marking on future-oriented temporal expressions in the standard of a phrasal comparative. In Tiwa, temporal expressions are by default past-oriented, with future-oriented temporal expressions formed by affixing dative case -(n)a (Dawson 2020: 30). This process applies generally across the language, as shown for a sample of temporal expressions in (44).

-

(44)

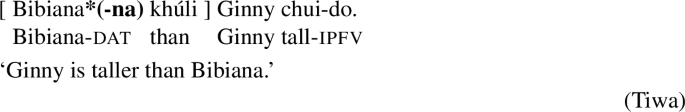

Comparatives in Tiwa are phrasal, rather than clausal, with the standard of comparison assigned dative case by the comparative postposition khúli ‘than’ (Dawson 2020, 2021), as shown in (45). Temporal expressions can serve as the standard of comparison, as shown in (46), with the expected dative case marking.

-

(45)

-

(46)

When a future-oriented temporal expression serves as the standard of comparison, there is only one surface realization of dative case, as shown in (47). If there were no haplology, we would expect a dative-dative string—the first because the temporal expression is future oriented, and the second assigned by the comparative khúli.Footnote 17

-

(47)

In continuous DPs, haplology occurs when nested instances of D are linearly adjacent, resulting in only one instance of the case marker. In discontinuous DPs, on the other hand, each piece surfaces with matching case because the iterated instances of D are separated by intervening material. In deriving these discontinuous structures, the case feature is shared between instances of D when the DPs are nested. For example, since both the noun and adjective in (37), repeated as (48), surface with dative case, dative case is assigned when the DPs are still in a nested configuration.

-

(48)

The dative case feature is spread from D1 to D2, and when the DP is split via remnant movement, both instances of D surface as the dative case marker, resulting in the pattern of case matching.

Before moving on to consider various extensions of our analysis, it is worth considering briefly another alternative to the DP-shell account we have proposed. The island facts discussed here support a movement derivation of discontinuous DPs. However, an alternative possibility to the view that we argue for here is to assume that the entire DP containing the noun and modifiers undergoes movement and that the appearance of a discontinuous DP arises because different elements of the DP are pronounced at different positions along the path of movement (Fanselow and Ćavar 2002). This type of analysis would not require positing multiple DP shells, but rather would rely on some process like scattered deletion (Nunes 1999) to derive the surface distribution of elements. Under this type of account, if we assume that case is only realized in D, the correct case matching results could be derived so long as D could never be targeted for scattered deletion. This is because there would be a single instance of D in each copy in the movement chain, which, if pronounced, would result in a case enclitic on whatever other material was pronounced at that position in the chain.

A major issue for this type of account lies in constraining the deletion operation. An unconstrained deletion operation could, for example, produce the appearance of island violations. As discussed, a modifier cannot be separated from its head noun across a relative clause island. If scattered deletion were allowed to freely apply to any terminal nodes in a copy of a moved DP, a seemingly island-violating string could be derived without any genuine island violations. Consider the example in (49).

-

(49)

In this structure, the entire DP containing the relative clause undergoes movement. In the higher copy, all material in the DP and the relative clause it contains is deleted except for the noun libíngrâw ‘people’ and its accusative case marker—an instance of D. In the lower copy, only the restrictor of the quantifier sógol inside the relative clause is deleted. This deletion would result in the appearance of an island violation without any true movement out of an island. Such configurations are ungrammatical, suggesting that scattered deletion would have to be constrained so as not to allow such strings to arise.Footnote 18 An additional constraint on deletion would have to prevent case markers themselves from being deleted in movement copies. If deletion of D were not ruled out, case matching would appear to be optional.Footnote 19 As we showed in Sect. 2, the only place where pieces of discontinuous DPs are allowed to mismatch in case is in DOM contexts. Otherwise, case matching is obligatory.

As outlined here, a scattered deletion account would have to be significantly constrained in order to derive the correct results. The problem is that there is little consensus about how to properly constrain this mechanism, and the Tiwa data conflict with some prominent proposals for how to do so. This is clear, for instance, for constraints along the lines of those put forth by Nunes (1999) and Bošković (2001). They consider scattered deletion to be a last resort option—it is only licensed if full deletion of a lower copy is blocked for PF reasons. The types of patterns found with discontinuous DPs in Tiwa do not seem indicative of a last resort strategy. There is no consistent position that the lower piece of a discontinuous DP must occupy such that its pronunciation appears to be motived by PF considerations. Likewise, structures with continuous DPs in the highest position in the chain are always possible alternatives to their discontinuous counterparts. Thus, it appears that scattered deletion would have little motivation in Tiwa discontinuous DPs, in addition to requiring multiple stipulations to rule out unattested deletion patterns.

The proposal we have sketched here based on DP shells is able to derive the key pattern of case matching only under discontiguity with fewer stipulations than alternative accounts require. In the following two sections we will discuss how this analysis is able to be straightforwardly extended to derive case mismatches in DOM contexts as well as patterns of case stacking in Tiwa.

4.2 Deriving case mismatches

As discussed in Sect. 2.3, pieces of a discontinuous DP in Tiwa may mismatch in case only if the case associated with the DP is accusative. This can be understood as part of a broader pattern of DOM in the language.

The analysis laid out above must assume that case assignment can precede remnant movement of the lower DP in a nested structure in order to derive feature sharing between instances of D and thus case matching. Case is assigned and shared between nested instances of D; later movement then allows each instance of D to realize the matching case value that was assigned earlier. This is schematized in (50).

-

(50)

However, in order to derive case mismatches, it must also be possible for case assignment to follow the movement that splits a DP, leading to only one of the resulting DPs appearing with case marking. If movement occurs before case assignment, the two resulting pieces of a DP can be assigned case independently, yielding a possible mismatch in case. This is schematized in (51).

-

(51)

Crucially, the instances where case assignment can follow remnant DP movement are significantly more restricted than the instances where case assignment must precede movement. Specifically, case assignment only appears to be able to follow movement when the case that is being assigned is accusative case. We argue here that this state of affairs is expected under prominent approaches to the treatment of accusative case.

Under Agree-based approaches to case assignment, accusative case is generally taken to be a structural case that is assigned by v/Voice (Kratzer 1996; Chomsky 2000, 2001; Legate 2008; among others). If we assume that object DPs are merged within the VP, this means that the head that assigns accusative case to the object is not merged until after the object has been merged, allowing for the possibility that remnant movement of part of the object DP could occur prior to Merge of v. If this remnant movement took place before v was merged, v could assign accusative case only to the higher of the two DPs in the discontinuous DP structure, as in (51). If case were assigned after the DP was split, the accusative case feature could not spread between instances of D since they would not be in the requisite local nested configuration.

This same kind of flexible ordering of movement and case assignment would not be possible with other overt cases that display matching. For example, dative on indirect objects can be analyzed as an inherent case, associated with an applicative or v structure above the VP (e.g. Woolford 2006). If a DP is merged as the specifier of ApplP, it will be assigned inherent dative case by Appl upon external Merge. Because dative case is assigned as soon as the DP in question is merged and not once a higher head is merged in the structure, there is no flexibility in the relative timing of case assignment and movement. Remnant movement of a lower DP in a nested DP structure cannot take place until after dative case has been assigned, resulting in no possible mismatches in dative case. A similar situation holds for the other cases that show obligatory matching: they are not assigned via Agree with a higher head outside of the phrase where they are externally merged, yielding a pattern of obligatory matching.

Another prominent approach to accusative case assignment, and particularly DOM, is dependent case theory (Yip et al. 1987; Marantz 1991; Baker and Vinokurova 2010; Baker 2015; among others). Under dependent case theory, it is generally assumed that accusative case is assigned to the lower of two DPs in a c-command configuration in a clause. Patterns of DOM can be derived by assuming that the internal argument must move out of the VP in order to be in the same case domain as the external argument. If the internal argument moves into the correct case domain, it is assigned accusative case; if it remains low, it does not receive dependent accusative case.

We do not take a stance on whether this approach to DOM is ideal for Tiwa, and we acknowledge that the very existence of discontinuous DPs presents some challenges for standard dependent case algorithms since two pieces of what was underlyingly a single DP should not be able to count as case competitors for one another. However, we aim to show that the case mismatches that we see only for accusative case could be derived under a dependent case approach as well. In order for dependent case assignment to interact correctly with the timing of movement to derive both accusative matches and mismatches, we must assume that dependent case assignment applies in the narrow syntax (Preminger 2011, pace Bobaljik 2008). If the entire nested internal argument DP moves into the same case domain as the external argument DP before it is split, the entire thing could be assigned accusative case. If the nested DP is then split by remnant movement of the lower DP, both pieces would have accusative case.Footnote 20 If, however, only one piece of a discontinuous DP moves high enough in the structure to be in the same case domain as the external argument, only that piece will be assigned dependent accusative case, resulting in a case mismatch. This kind of approach to case assignment would not derive case mismatches for other cases, such as dative, since none of the other cases require a DP to first move into a different case domain to be assigned case.

While case mismatch data in the context of DOM can be accounted for under the nested DP approach to case matching we present here, regardless of whether an Agree-based or dependent view of accusative case is adopted, these data are problematic for concord-based views of case matching. For the purely morphological view of case matching considered in Sect. 3, case matching would be the result of true concord plus deletion of all but the final instance of case in each continuous portion of the DP. It is unclear how case mismatches could be derived in DOM contexts under such a view. If case were always assigned to the entire DP, it should always surface on both pieces of the discontinuous object DP. If, as under our account, case is assigned only to the piece of the discontinuous DP that surfaces with case in DOM contexts, then the highest piece of the DP must be independently eligible for case assignment. This is captured under our account by the fact that the piece of a discontinuous DP that surfaces with case is itself a full DP, eligible for case assignment. At the very least, it seems that a surface-oriented account involving concord plus impoverishment would have to allow each piece of a discontinuous DP to be assigned case independently, requiring something like multiple DP layers—one for each piece of a DP.

Likewise, another possible alternative analysis based on traditional concord would be one in which concord is only possible in certain domains in the DP (Pesetsky 2013; Bayırlı 2017). According to this type of view, case concord within the DP would be blocked from applying below a certain layer of structure in the DP. Above this boundary, all elements would be able to participate in the feature sharing necessary for concord, but below this boundary, feature sharing would be blocked completely. Under this type of account, nouns and modifiers in Tiwa would typically be too low in the DP to undergo case feature sharing with D. However, if discontinuous DPs were formed by moving an element out of DP and if this movement out of DP were preceded by a step of movement higher in the DP, specifically to Spec,DP, this intermediate movement step would allow the moving element to enter the domain in which concord was active and thus show concord. The DOM data prove challenging for this type of account. If case were assigned prior to the DP splitting, it is unclear how a case mismatch could be derived. Both D and the element that moved through its specifier should bear case. If case were assigned after the DP was split, the higher, case-bearing piece of the DP would need to be independently eligible for case assignment. As with the impoverishment that was just discussed, this would still require an appeal to multiple DP layers.Footnote 21

4.3 Case stacking

An interesting facet of the phenomenon of case iteration in Tiwa is that it can result in case stacking, as seen in (52) and (53).

-

(52)

-

(53)

In (52), the possessor Sonali surfaces with genitive case, as we expect since it is a possessor. However, stacked outside of the genitive case marker -ne is the accusative case marker -gô. This accusative case is what we expect since Sonali originates within a DP that itself is accusative-marked, as evidenced by the accusative case on the noun miyâw ‘cat.’ The same pattern holds with comitative case, as shown in (53), where the genitive-marked possessor Sonaline also takes the comitative marker -rê.Footnote 22

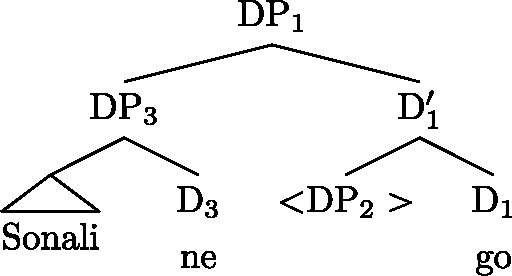

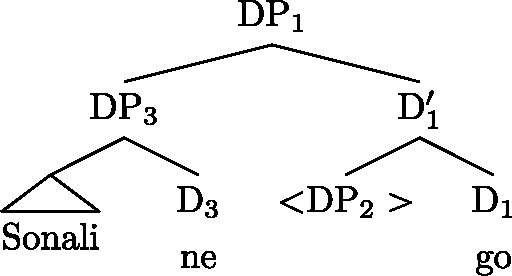

We propose that the reason discontinuous possessors can exhibit case stacking is because they contain two instances of D that bear different case features. We assume the base structure of a DP with a possessor that will be split from the rest of the DP is as shown in (54) for the DP Sonaline miyâw ‘Sonali’s cat.’

-

(54)

When the possessor Sonaline is stranded, it first moves to Spec,DP1, as shown in (55).

-

(55)

Accusative case is assigned to DP1, and case is spread from D1 to D2. Finally, DP2 undergoes remnant movement, stranding DP1, which contains the possessor. The structure of the stranded element is shown in (56), in which D1 and D3, the head of the possessor DP, are adjacent.

-

(56)

In this structure, D3 is realized as the genitive case marker -ne and D1 is realized as the accusative case marker -gô. Since the two instances of D bear different features, haplology does not apply, resulting in surface case stacking.

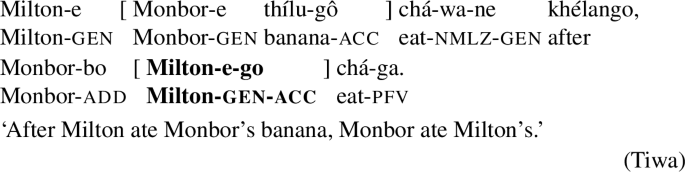

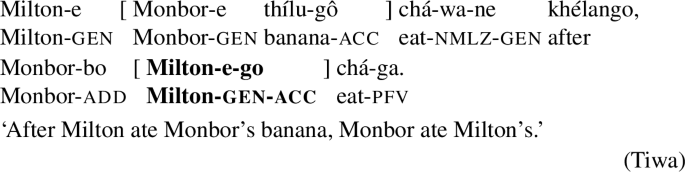

This configuration of two adjacent, featurally distinct instances of D occurs elsewhere in the language, namely in NP ellipsis. When a possessed noun is elided in Tiwa, the case marker that would typically appear on the noun stacks onto the genitive-marked possessor. This is shown in (57).

-

(57)

In the DP Miltonego ‘Milton’s’ in (57), the noun thílu ‘banana’ is elided under identity with the previous instance of the noun in the phrase Monbore thílugô ‘Monbor’s banana.’ Even though the NP is elided, the accusative case marker that would otherwise surface on the noun remains: it is stacked on the genitive-marked possessor. Just like the structure in (56), the DP Miltonego involves two adjacent instances of D—one internal to the possessor DP, and the other in the main DP. We take this parallel as support for the idea that case stacking in discontinuous DPs involves multiple adjacent instances of featurally distinct D.

The DP-shell analysis we have proposed for case iteration is able to account not only for the pattern of case matching that we find in discontinuous DPs in Tiwa, but also for case mismatches that arise in DOM contexts as well as instances of case stacking. In the following section we show that this DP-shell analysis can also be extended to account for a similar pattern of case iteration in an unrelated and typologically different language, Amahuaca.

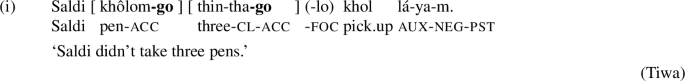

5 Extending the DP-shell analysis to Amahuaca

Amahuaca is a Panoan language spoken in the Peruvian and Brazilian Amazon by approximately 500 speakers (Eberhard et al. 2023). The data presented here were collected by the first author through fieldwork with four speakers carried out in the district of Sepahua in Atalaya Province, Ucayali, Peru between 2015 and 2018. Amahuaca is mixed headed, being mostly head final, but having a head-initial AspP and CP (Clem 2022). Scrambling of arguments and adjuncts is largely available. As in Tiwa, DP-internal word order in Amahuaca is flexible (Clem 2019a: 47–50), suggesting the availability of movement operations within the DP. One difference from Tiwa, which displays accusative alignment, is that Amahuaca exhibits a tripartite alignment system with nominative, ergative, and accusative case. Case surfaces as a DP enclitic. Another difference we will see is that Amahuaca has differential subject marking rather than differential object marking, and this differential case marking is clearly structural in nature (Clem 2019b). Despite these differences between the two languages, we will demonstrate that the DP-shell analysis we have pursued for Tiwa can be easily extended to derive the Amahuaca patterns.

5.1 Case matching in Amahuaca

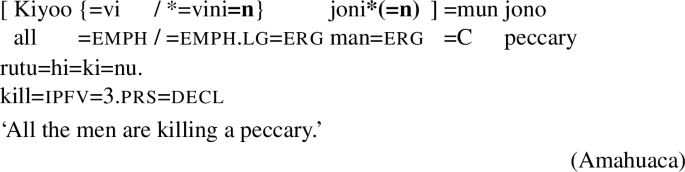

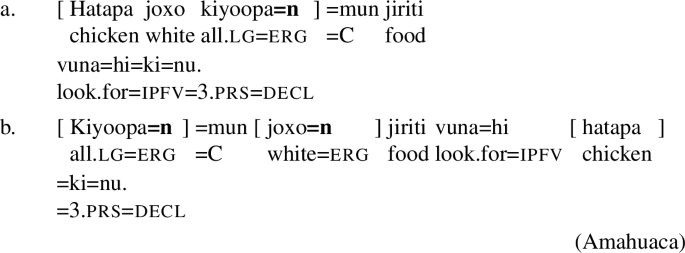

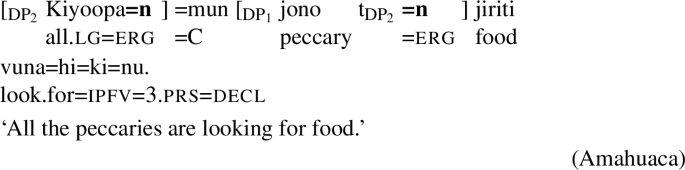

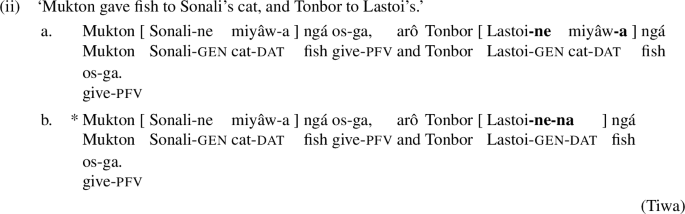

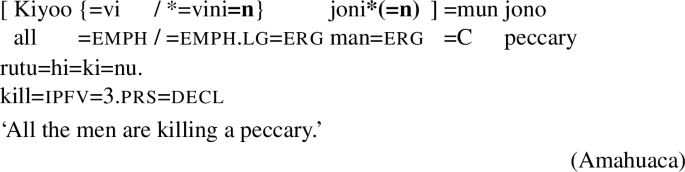

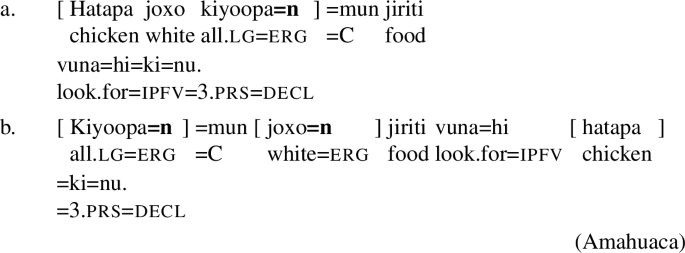

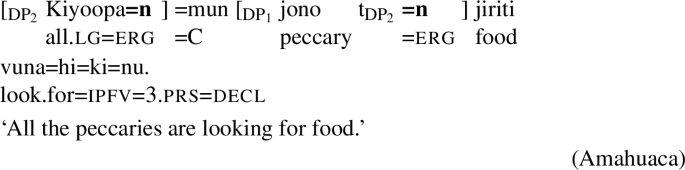

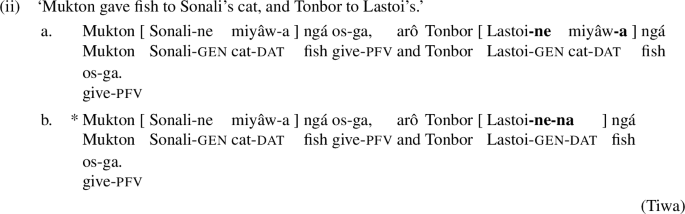

As in Tiwa, there is no case concord in continuous DP structures in Amahuaca. In matrix declarative clauses, a second position clitic =mun surfaces with exactly one syntactic constituent preceding it (Clem 2019b). It is ungrammatical for a DP with multiple instances of case marking to appear in the initial position before this clitic, as shown in (58).Footnote 23

-

(58)

In (58), ergative marking is obligatory at the end of the DP, but it is ungrammatical internal to the DP on the quantifier kiyoovi(ni). From the position of the DP before the second position clitic, we can conclude that the noun and its modifier form a single constituent. Therefore, the ungrammaticality of double case marking demonstrates that when a noun and its modifiers occur as a single continuous constituent, case concord is impossible. Note that this pattern contrasts with that found in a language with true concord like Warlpiri. Warlpiri also has a second position clitic (the auxiliary ka-pala in (31) above), and when a DP is clearly a single constituent before the second position clitic, case concord is still possible (Simpson 1991: 257–258).

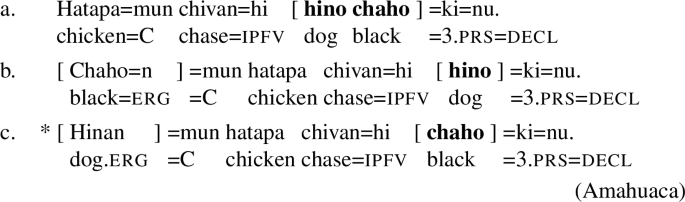

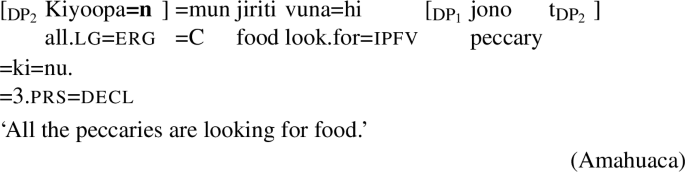

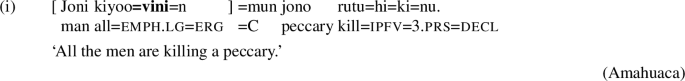

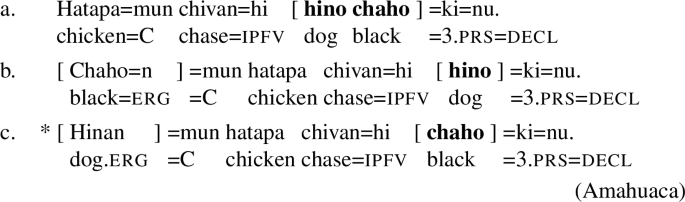

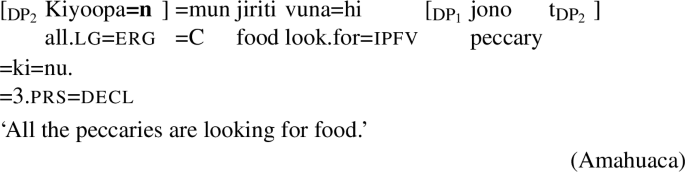

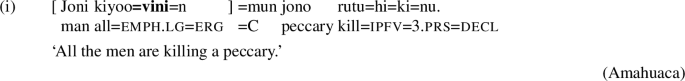

Also like in Tiwa, case matching on the noun and its modifiers becomes available when the DP is discontinuous in Amahuaca. Modifiers that are separated from the noun match the noun in case, as seen in (59) with ergative case.

-

(59)

We see in (59) that when the noun is separated from the quantifier, both pieces surface with ergative case marking.

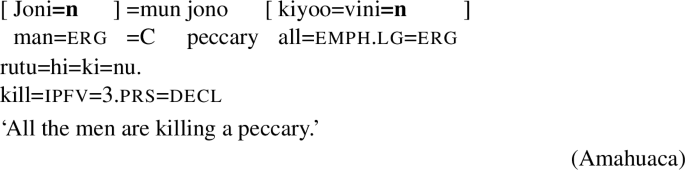

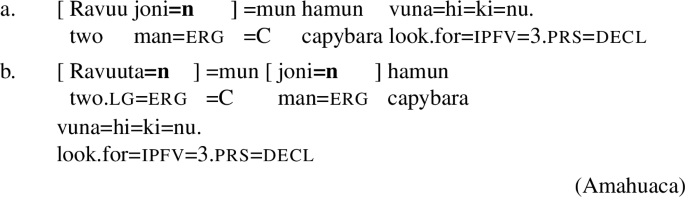

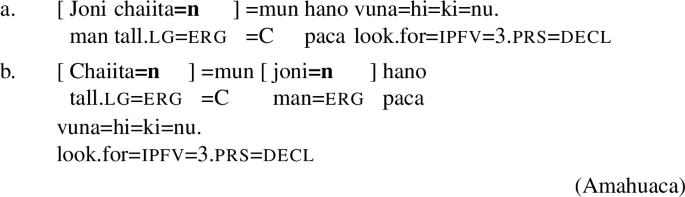

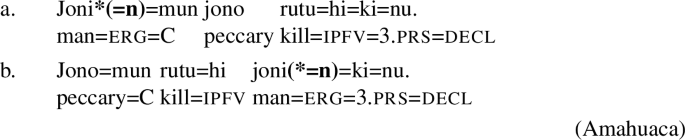

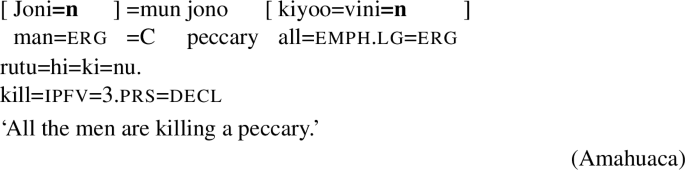

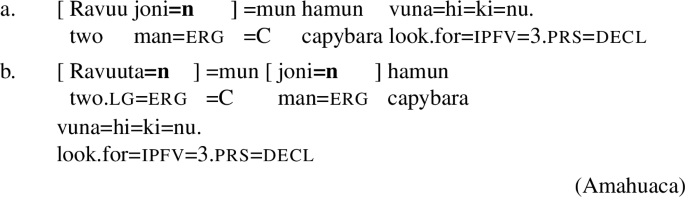

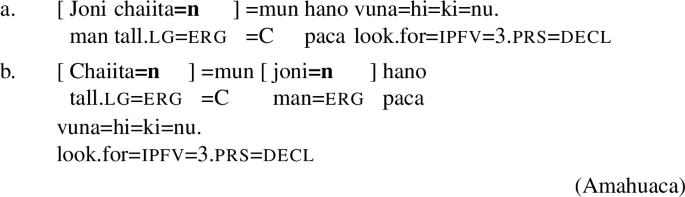

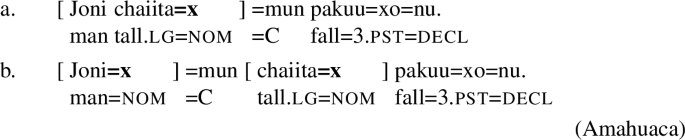

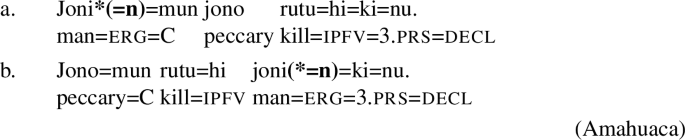

In Amahuaca, like in Tiwa, various modifiers can be separated from the head noun to form a discontinuous DP. When they are separated, they match the noun in case. Modifiers displaying this behavior include quantifiers, as was seen in (59), and also numerals (60), and adjectives (61).

-

(60)

‘Two men are looking for capybaras.’

-

(61)

‘The tall man is looking for a paca.’

In (60b), both the numeral ravuu(ta) ‘two’ and the noun joni ‘man’ surface with ergative case. In (61b), the adjective chaii(ta) ‘tall’ and the noun joni ‘man’ both surface with ergative case.

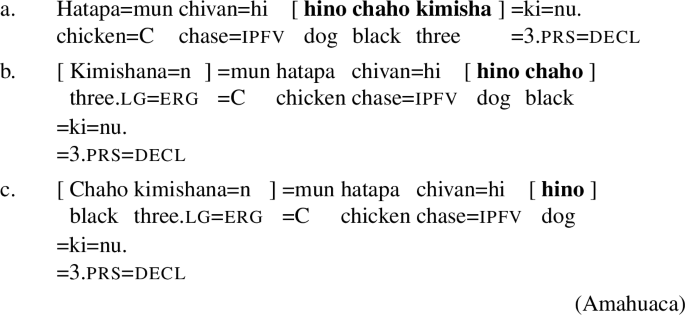

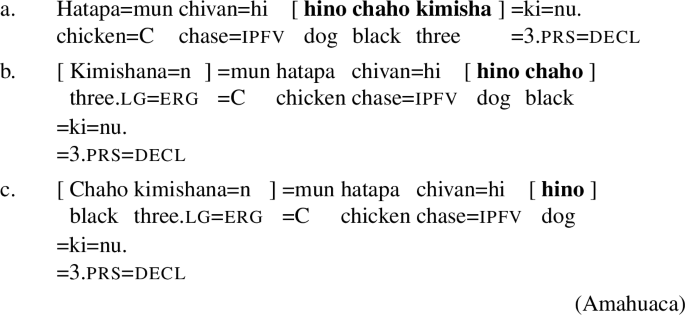

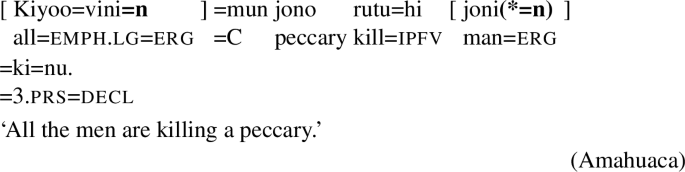

Like in Tiwa, it is also possible for Amahuaca DPs with more than one modifier to be split into more than two pieces under the right conditions. This is shown in (62) for a three-part split.

-

(62)

‘All the white chickens are looking for food.’

In (62b) both the quantfier kiyoo(pa) ‘all’ and the adjective joxo ‘white’ are split from the noun hatapa ‘chicken,’ and both modifiers surface with ergative case.Footnote 24

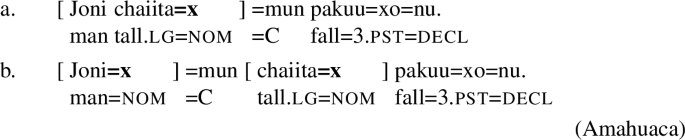

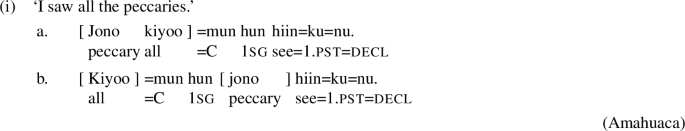

In addition to matching in ergative case, as we have seen in the examples so far, discontinuous DPs can also match in nominative case, as seen in (63). Note that nominative case receives a non-zero realization in Amahuaca.Footnote 25

-

(63)

‘The tall man fell.’

As seen in (63b), when the head noun joni ‘man’ is separated from the adjective chaii(ta) ‘tall,’ both pieces can surface with nominative case.

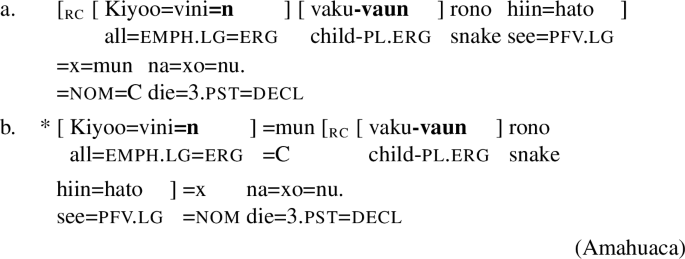

Similar to what was seen for Tiwa, discontinuous DPs in Amahuaca show sensitivity to islands. Relative clauses in Amahuaca are islands for movement (Clem 2019a: 46, 2023). As shown in (64b), it is impossible for a modifier of a non-head constituent of a relative clause to surface outside of the relative clause despite the fact that DP splits are possible within relative clauses, as seen in (64a).

-

(64)

‘The snake that all the children saw died.’

In (64a), the subject of the internally-headed relative clause is structurally discontinuous. The modifier kiyoovinin ‘all’ is split from the noun vakuvaun ‘children’ and both surface with ergative case. However, when the modifier kiyoovinin is moved out of the relative clause to a position before the second-position clitic =mun, as in (64b), the result is ungrammatical. This provides evidence that the two pieces of a discontinuous DP in Amahuaca are related via movement since they cannot be split across a relative clause island.Footnote 26

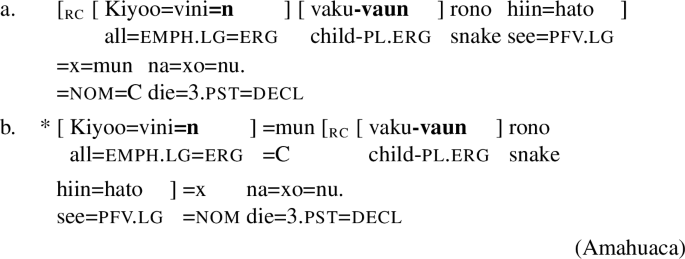

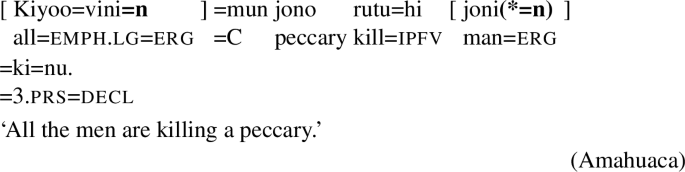

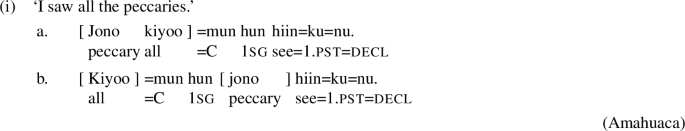

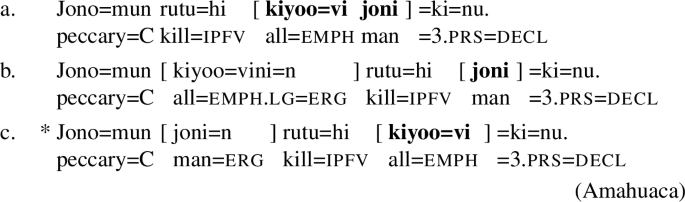

A final interesting point to consider in terms of the basic patterns of discontinuous DPs in Amahuaca is a restriction on the surface position of nouns and their modifiers. There are, in general, few restrictions on the surface position of various pieces of discontinuous DPs in Amahuaca. However, one important generalization emerges. If one piece of a discontinuous subject appears in the base position of the DP, the noun must surface in this piece of the discontinuous DP. We assume that the externally-merged position of subjects in Amahuaca is in Spec,vP (modulo unaccusativity). Head-initial AspP dominates vP, meaning that subjects that remain in their externally-merged position linearly appear immediately to the right of aspect marking (Clem 2019b). Modifiers may not be stranded in this position, as seen in (65) and (66). (The distribution of ergative case in examples like (65)–(67) is the subject of Sect. 5.3.)

-

(65)

‘All the men are killing a peccary.’

-

(66)

‘The black dog is chasing a chicken.’

In (65a), we see that a continuous DP with a quantifier and noun can appear in the externally-merged position of the subject. The example in (65b) shows that the noun can be stranded in this low position with the quantifier surfacing higher in the structure. However, (65c) demonstrates that it is ungrammatical to strand the quantifier in a similar way, even though quantifiers can, in general, appear lower than their restrictors, as in (59).Footnote 27 This ungrammaticality is not remedied by causing the two pieces of the DP to match in case. The same pattern is shown for an adjective in (66)—only the noun, not the adjective that modifies it, can be stranded in the base position of the subject.

Interestingly, when a noun contains more than one modifier, one of the modifiers can be stranded along with the noun in the base position of the subject, as shown in (67).

-

(67)

‘Three black dogs are chasing a chicken.’

In (67a), we see a DP with a noun, adjective, and numeral in the base subject position. It is possible for the noun hino ‘dog’ and the adjective chaho ‘black’ to remain in this position while the numeral kimisha(na) ‘three’ moves higher, as in (67b). Note that it is also possible for both modifiers to move together to a higher position, stranding only the noun, as seen in (67c).Footnote 28 Therefore, the generalization that emerges is that, in a discontinuous subject DP, if any piece remains in the base position, that piece must contain the noun. This generalization will factor into our discussion of the derivation of discontinuous DPs in Amahuaca in the following section.

5.2 Analysis of Amahuaca case matching

As discussed for Tiwa in Sect. 4, we assume that case matching under discontiguity arises in Amahuaca due to the presence of multiple shells in the DP. In this section, we highlight how this case iteration analysis is able to be extended to Amahuaca with minimal additions, despite the differences between Amahuaca and Tiwa.

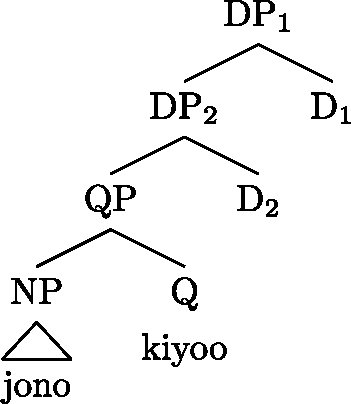

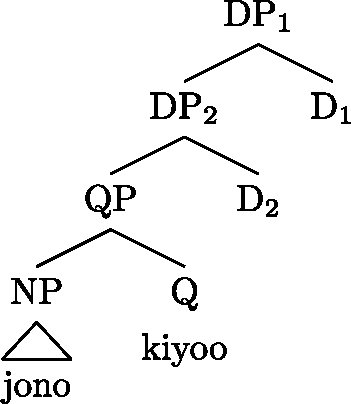

We assume that iteration of D is possible in the Amahuaca DP, with remnant movement of the lower DP in discontinuous structures. This means that a DP like jono kiyoo ‘all peccaries’ will have a base structure as in (68) prior to undergoing splitting.

-

(68)

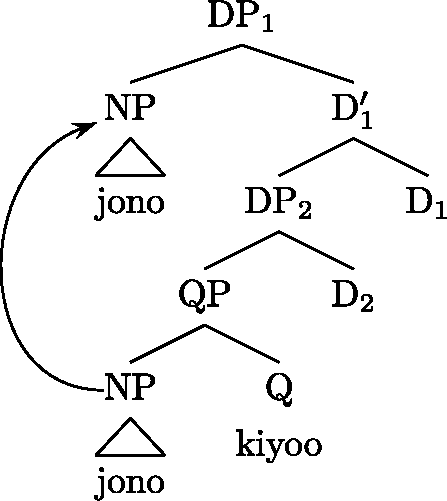

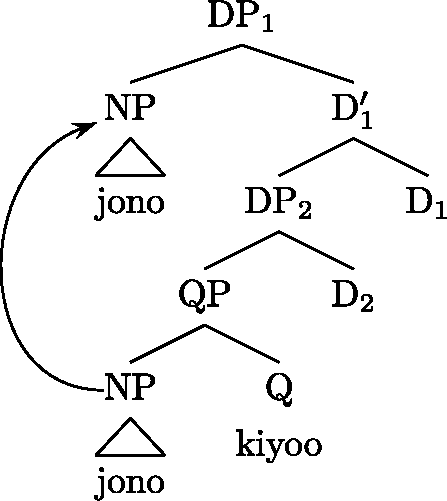

In the tree in (68) we see that D1 takes DP2 as its complement. In turn, the head of this DP selects a QP, which contains the quantifier and NP. Given the noun-stranding data discussed in Sect. 5.1, we must make one stipulation for Amahuaca that was not necessary for the Tiwa data. As we saw, a piece of a discontinuous DP containing the noun may be stranded in the base position of the DP in Amahuaca, but a piece containing only modifiers may not. We argue that this is due to the fact that, in Amahuaca, the subconstituent that moves to the specifier of a higher DP must contain the noun.Footnote 29 This will leave the lower DP, which will then contain only modifiers, free to undergo remnant movement and strand the noun. This NP movement to Spec,DP1 is illustrated in (69).

-

(69)

Once this movement to Spec,DP1 occurs, DP2, which contains the universal quantifier kiyoo, is free to undergo remnant movement, stranding the noun in the position occupied by DP1. This remnant movement results in configurations like those shown in (70).

-

(70)

In (70), the quantifier and the noun match in case. This case matching is derived via feature spreading of the ergative case feature from D1 to D2. When the head of DP1 is assigned ergative case, it passes this feature on to the head of DP2, which is still nested within DP1. When DP2 undergoes remnant movement, both D1 and D2 will surface as ergative case.

In a continuous DP in Amahuaca, only one case marker surfaces. For Tiwa, we argued that both instances of D did not surface as adjacent case markers in continuous DPs due to haplology. In Amahuaca, the ergative case marker is simply suprasegmental nasality that surfaces on the preceding vowel (orthographically represented as =n) and the nominative case marker is a palatal fricative (orthographically represented as =x). Given that Amahuaca does not phonologically show more than a two-way nasality contrast for vowels nor a length contrast for fricatives, we assume that there is not a phonologically licit way to contrastively realize adjacent case markers at the right edge of a continuous DP in Amahuaca. Only when a DP is split can multiple case markers surface.

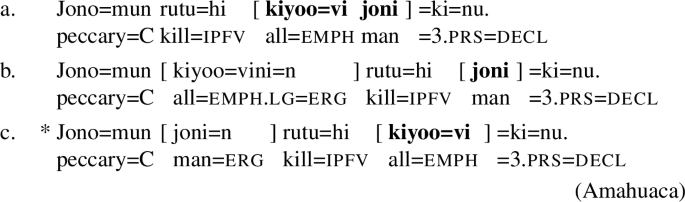

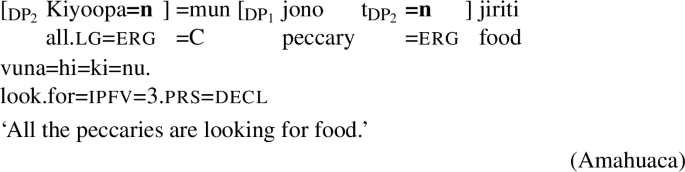

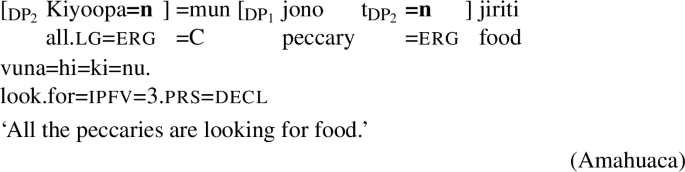

5.3 Differential subject marking

Having demonstrated how the DP-shell analysis can derive the case iteration in Amahuaca, we now turn to a slightly more complicated set of data. Like Tiwa, Amahuaca exhibits differential case marking. However, in Amahuaca, it is ergative subjects that can appear in a case-marked or unmarked form, and the marking of ergative case depends strictly on the syntactic position of the transitive subject.Footnote 30 Interestingly, this pattern of structural differential case marking interacts with case iteration. This interaction falls out from the architecture of the DP-shell analysis and the assumption that case assignment can be timed before some instances of movement and after others (i.e. the assumption that case assignment can occur in the narrow syntax; Preminger 2011).

As mentioned in the discussion of noun-stranding, Amahuaca subjects that appear to the right of aspect are those that appear in their base position. In this position, transitive subjects are unmarked for case. Transitive subjects that appear higher in the structure receive ergative case, as demonstrated in (71).

-

(71)

‘The man is killing the peccary.’

In (71a), we see that the transitive subject joni ‘man’ is marked with ergative case, as expected. However, in (71b), this subject DP remains low in its externally-merged position and does not receive ergative case marking. Clem (2019b) provides a more detailed description of this pattern of differential ergative marking and analyzes ergative case as the result of agreement with two heads, v and T. In order to be marked with overt morphological ergative case, a DP must agree with v in Spec,vP and must also agree with T, which goes hand-in-hand with movement of the DP out of vP.

Important for our purposes is the interaction between this pattern of differential subject marking and case matching. The only types of configurations where the two pieces of an ergative DP mismatch in case is when one piece remains in the low vP-internal position, where DPs generally lack overt case. In such instances, the piece of the DP that remains low is not marked ergative, while the piece that moves higher surfaces with ergative case, as demonstrated in (72).

-

(72)

In (72), the subject quantifier surfaces with ergative case. However, the corresponding noun remains low and cannot surface with ergative case. Crucially, this pattern is exactly what we would expect given the general pattern of ergative case marking in the language. Thus, as in Tiwa, case matching and mismatching reflect the more general patterns of case marking.

This case mismatching can be derived by considering the timing of case assignment and movement. Recall that in structures like (73), repeated from (70), case matching results because D1 is assigned ergative case prior to the splitting of the DP.

-

(73)

In (73), the entire nested DP is the goal for Agree with T and moves to the higher position associated with overt ergative case. D1 is assigned ergative case, and this case is spread to D2 in the nested configuration. When DP2 undergoes remnant movement, both D1 and D2 are realized with ergative case.

This case matching derivation can be contrasted with a derivation that results in a mismatch like we see in (74).

-

(74)

In structures like (74), the nested DP is not the goal for Agree with T. Instead, DP2 undergoes remnant movement out of DP1 and subsequently is a goal for Agree with T, moving to the higher position associated with overt ergative case. Because D1 and D2 are no longer in a nested configuration at the time of case assignment, feature spreading between the two instances of D does not apply. Thus D2 is assigned ergative case directly and D1 does not receive case. This results in the mismatch in case that we find. Like in Tiwa, the availability of a case mismatch is due to the fact that (overt) ergative case is not assigned immediately upon external Merge of the DP in Amahuaca, allowing for the DP to be split prior to case assignment.

We have thus demonstrated that the DP-shell analysis pursued for Tiwa can be straightforwardly extended to Amahuaca, which is typologically quite different in various respects. Amahuaca has a tripartite alignment system and exhibits differential subject marking, while Tiwa shows accusative alignment and differential object marking. However, the shared pattern of case matching only under discontiguity can be accounted for under the same basic case iteration analysis that relies on nested DP shells.

6 Case iteration crosslinguistically

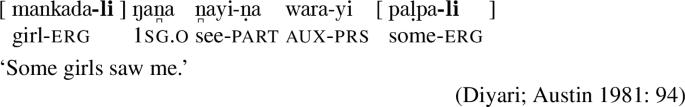

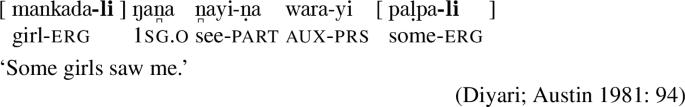

We have argued that case iteration in Tiwa and Amahuaca is an empirically different phenomenon from case concord. In case iteration, multiple instances of D originating in the same DP shell structure spell out the same case features. In case concord, various categorially distinct elements in the DP bear morphological reflexes of case. In this section, we discuss crosslinguistic predictions of the DP-shell account of case iteration we have developed here and its possible connections to the phenomenon of determiner spreading.

Tiwa and Amahuaca are unrelated languages with quite different typological profiles. These languages show similar case iteration patterns because (i) they mark case as an enclitic on the DP, (ii) they allow discontinuous DPs, and (iii) they lack DP-internal case concord. In this section we will discuss two additional languages that show these features.

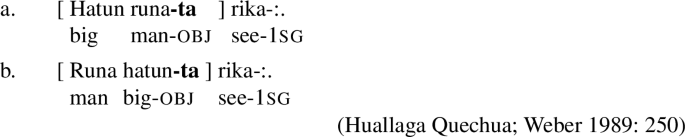

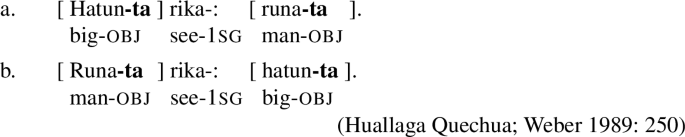

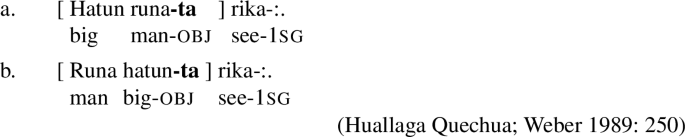

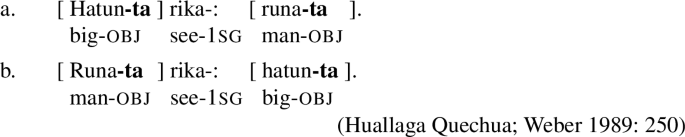

The first language we will consider is Huallaga (Huánuco) Quechua (Quechuan; Peru). In Huallaga Quechua, case surfaces on the final element of the DP, regardless of whether that element is the head noun or a modifier, as shown in (75).Footnote 31

-

(75)

‘I see the big man.’

In (75) object case -ta appears on the final DP-internal element, which is runa ‘man’ in (75a) but hatun ‘big’ in (75b) when the modifier appears post-nominally. Note that in these examples we see only one instance of case marking within the DP rather than observing concord.

Discontinuous DPs are also possible in Huallaga Quechua, and when they occur, each element must bear a copy of the appropriate case marker for the DP (Weber 1989: 231, 250). This case iteration pattern is exemplified in (76).

-

(76)

‘I see the big man.’

Here, the modifier and head noun are split across the verb and both must surface with the object case marker -ta in this discontinuous configuration.Footnote 32