Abstract

Research on the (in)definiteness of bare nouns has developed various proposals regarding which type-shifters exist in human language and which principles are needed to govern their distribution (Carlson 1977; Partee 1987; Chierchia 1998; Dayal 2004; i.a.). At the same time, literature on headless relative clauses (HRCs), primarily focusing on free relatives (FRs) in Indo-European languages, has also developed type-shifting principles (Jacobson 1995; Caponigro 2003, 2004). The type-shifting principles from the FR literature, however, are fundamentally different than those found in proposals for bare nouns. Here, we present case studies from two Mayan languages which diverge from one another in the behavior of bare nouns, and which possess several different kinds of headless relative clauses. We show that “super-free relative clauses” (Caponigro et al. 2021; Caponigro 2022), which lack a wh-word, pattern in ways parallel to bare nouns in the respective languages. We also demonstrate that HRCs headed by a wh-word—i.e., FRs—diverge from bare nouns; they pattern similarly to one another across the languages under investigation, and in ways similar to what has been reported for FRs crosslinguistically. We provide evidence that there is a dedicated FR type-shifter (FR-ι) used as a post-syntactic mechanism to repair a type-mismatch at the CP level, building on work by Caponigro (2004). Our novel contribution is that this type-shifter is available regardless of the presence or absence of other type-shifters in a language. This paper adds new data to our understanding of the range and applicability of different definiteness-related type-shifters as well as captures certain typological tendencies regarding HRCs.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

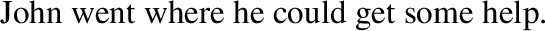

This paper investigates the meaning and distribution of headless relative clauses (HRCs): those that involve wh-words (so-called “free relatives”), and others that don’t. HRCs, such as the English free relative (FR) in (1), look like clauses but have the distribution of arguments. A semantic property of the FR in (1) is that it has a maximal interpretation (Jacobson 1995; Rullmann 1995; Caponigro 2004), meaning that it is possible to paraphrase this with a definite noun phrase: ‘the things/the food that you cooked.’

-

(1)

I ate [hrc what you cooked].

While such constructions in English are uniformly maximal in this way, looking beyond English, it appears to be more common to find that FRs allow either a maximal or an existential interpretation, depending on various factors such as the syntactic context in which they occur. Based on this observation, Caponigro (2004) claims that the FR in a sentence like (1) itself denotes a set of individuals, and proposes that if a type-mismatch occurs, it can be repaired by a type-shifter. Thus in order for the bracketed FR in (1) to be in argument position of the verb, there is a type-shifter that shifts the set of type 〈et〉 denoted by ‘what you cooked’ into a maximal individual of type e.

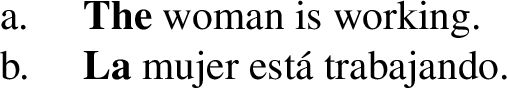

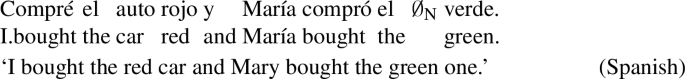

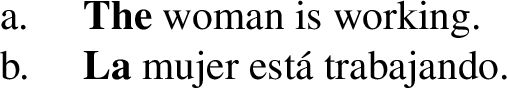

This analysis for the FR in (1) makes explicit appeal to the literature on type-shifters for bare nouns (Carlson 1977; Partee 1987; Chierchia 1998; Dayal 2004; Jenks 2018; Despić 2019; Moroney 2021; i.a.). This literature has developed various proposals regarding which type-shifters exist in human language, as well as which principles are needed to govern their distribution. In languages such as English and Spanish, overt morphemes such as the or la in (2) are needed in order for nouns to obtain a definite interpretation.

-

(2)

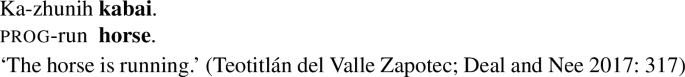

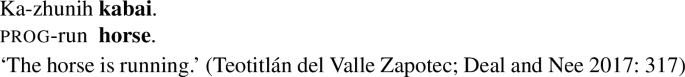

However, many languages do not have the equivalent of the bolded definite articles in (2). Instead, a bare noun can refer to a definite entity, as the bare noun kabai ‘horse’ in (3) from Teotitlán del Valle Zapotec.Footnote 1

-

(3)

The question of how to derive these definite readings from a bare noun in the absence of an overt morpheme has received considerable attention. A range of work has proposed that the covert type-shifter ι, which shifts properties to individuals, is only available in languages which lack a definite article, such as Teotitlán del Valle Zapotec (Deal and Nee 2017), but not in languages which have an overt article, like English or Spanish (Chierchia 1998; Dayal 2004; Jenks 2018; Despić 2019; Moroney 2021; i.a.).

Given this research on type-shifters cross-linguistically in the nominal domain, it is surprising that English or Spanish would have an equivalent ι type-shifter for FRs like the one in (1). That is, since English and Spanish have obligatory definite articles, we might expect them to lack a covert type-shifter of the sort needed to derive the FR in (1). In fact, if we were to take the analyses from the literature on languages with definite articles and apply them to HRCs, we would expect it to be the case that a definite article would appear in FRs in English, contrary to fact (cf. *‘the what you cooked’).

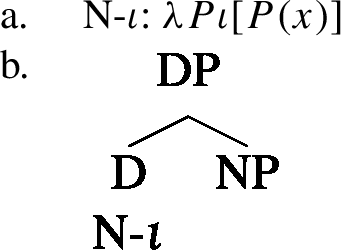

Why are the type-shifting principles for FRs different than those elsewhere within the same language? In this paper, we argue that there is an available ι type-shifter for FRs, FR-ι, in languages which have FRs—regardless of whether the language has overt definite articles in the nominal domain. We present evidence that while nominal ι (what we call N-ι) is available only in some languages to derive definite interpretations for bare nominals, FR-ι is needed to type-shift FRs, regardless of properties of a language’s nominal domain.

In this paper, we arrive at a finer-grained distinction of type-shifting. Many classic works like Montague (1974), Partee and Rooth (1983), Partee (1987) and literature within the Combinatorial Grammar literature (e.g., Steedman 1987; Jacobson 1999; i.a.), regard type-shifting as a foundational part of the formal semantic tool kit, that is, as part of the basic compositional architecture, rather than something that is part of the grammar or syntactic structures of particular languages. At the same time, there has been recognition (e.g. Pylkkänen and McElree 2006; Winter 2007) that not all type-shifting rules are necessarily alike. More specifically some type-shifting rules may be subject to cross-linguistic variation while some are more likely universal, as noted in Partee (1987). Despite this general recognition of the potential for different kinds of type-shifting, there has not been a clear-cut distinction made between general type-shifting principles as part of the compositional architecture versus ones that are subject to cross-linguistic variation. In this paper, we look at two type-shifting operations, N-ι and FR-ι, that perform the same function semantically but pattern differently from each other. N-ι, we propose, is variable across languages in ways that are sensitive to language-particular competition; another, FR-ι, we suggest to be uniform across languages as a post-syntactic last resort. In turn, the existence of N-ι is in a language is dependent to cross-linguistic variation, but FR-ι is not.

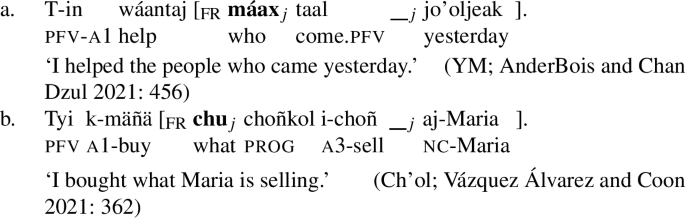

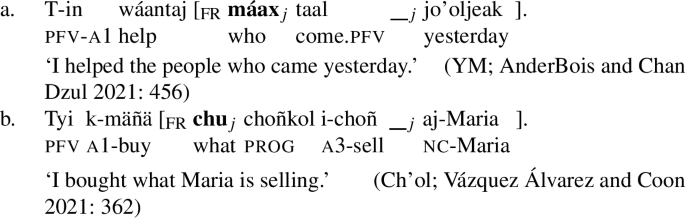

Empirically, we focus on the interpretation and distribution of bare nouns and HRCs in two Mayan languages: Yucatec Maya (YM) and Ch’ol. YM and Ch’ol differ in the possible interpretations of bare nouns: Ch’ol patterns like Teotitlán del Valle Zapotec in (3) in that it permits bare nouns to have definite interpretations in certain environments, while YM patterns more like the English and Spanish in (2) in that it requires articles for a definite interpretation. However, FRs such as in (4) for both languages are entirely parallel to each other—and also parallel to what has been reported for most other languages—in their distribution and interpretation.

-

(4)

We take this as evidence that the necessary type-shifter for FRs, FR-ι, is available for FRs across languages and crucially is not correlated with the availability of type-shifting in bare nouns within the same language. As we discuss below in detail (see especially Sect. 3.3 and Sect. 5.2), this lack of parallelism between FRs and bare nouns is all the more striking in Ch’ol and YM since FRs freely combine with the full range of determiners found with nouns.

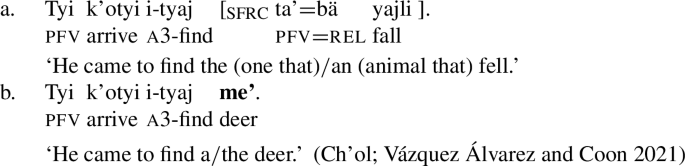

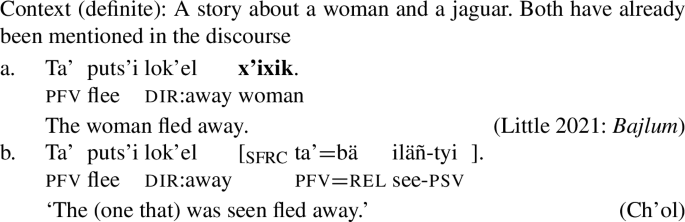

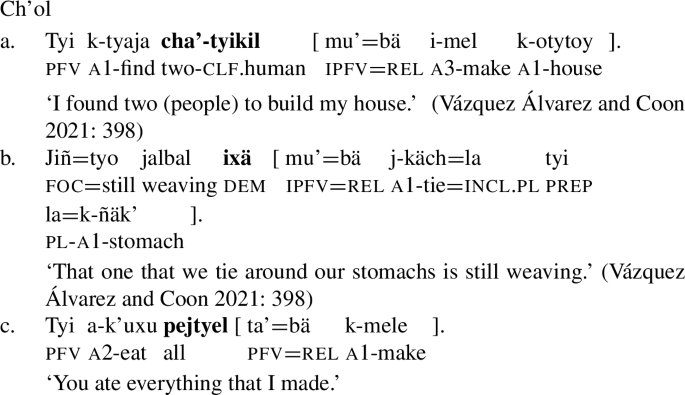

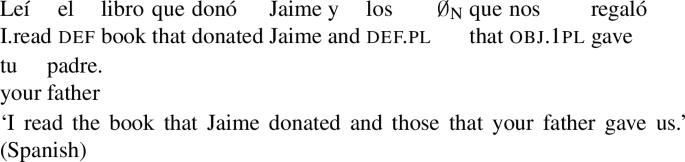

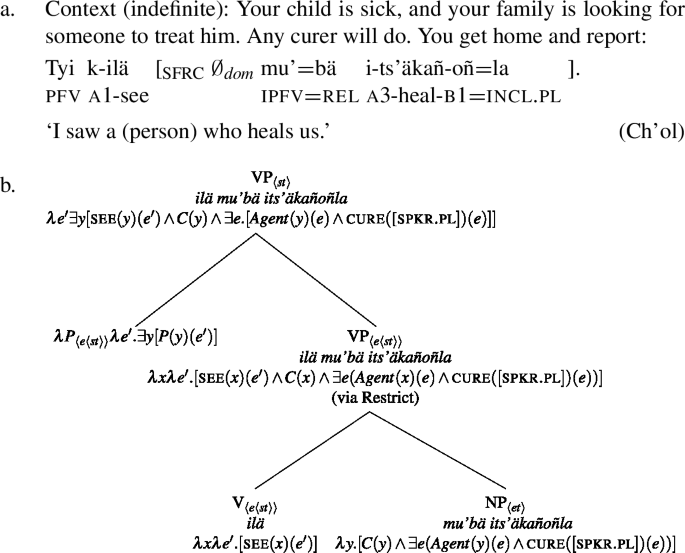

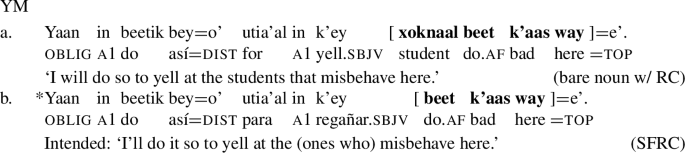

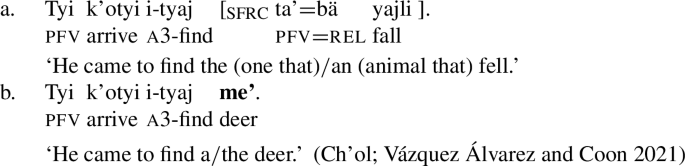

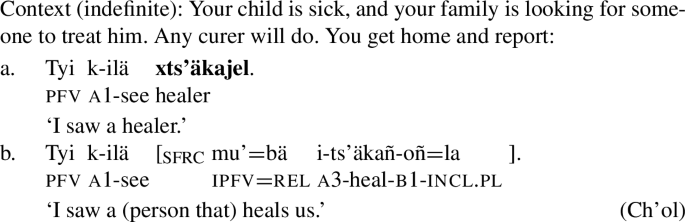

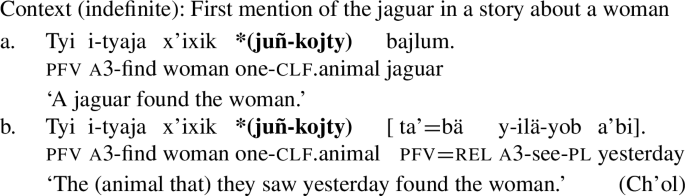

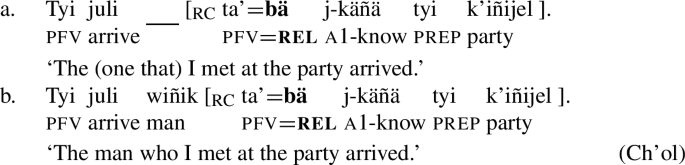

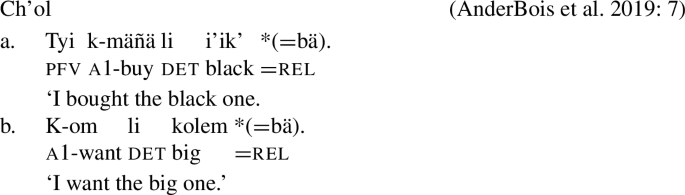

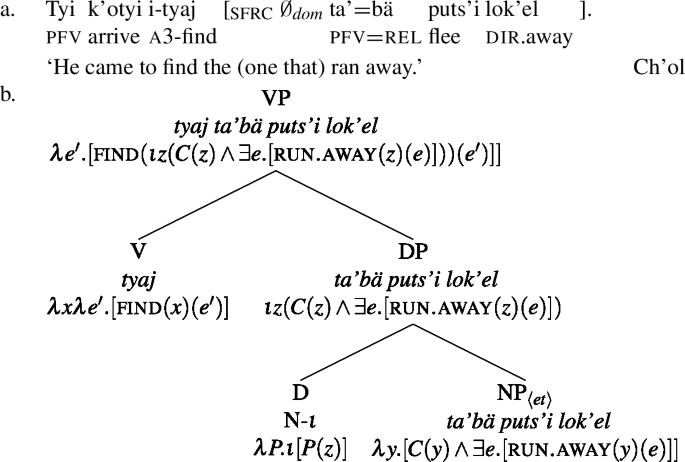

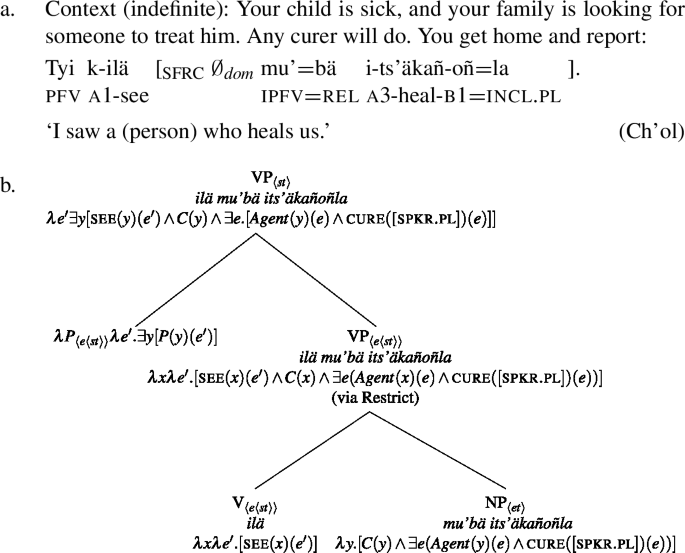

Beyond bare nouns, we also compare FRs with another type of HRC we call “super-free relative clauses” (SFRC), following terminology in Caponigro et al. (2021), shown in (5a) for Ch’ol. The SFRC in Ch’ol has no wh-word and is marked with the relative clause second position enclitic =bä on the perfective aspect marker (the perfective marker tyi is an allomorph of ta’). Compare (5a) to (5b), which has a bare noun in the same syntactic position.

-

(5)

In Ch’ol, we provide evidence below that both the SFRC and the bare noun can be interpreted as definite or indefinite, depending on the context. We show that—unlike FRs headed by wh-words in (4) above—the distribution and definite versus indefinite interpretation of SFRCs such as in (5a) parallel that of bare nouns in each language. Ch’ol and YM offer ideal test cases for this comparison because the two languages diverge substantially in how bare nouns may be interpreted. In Ch’ol, bare nouns can be definite or indefinite, paralleling the available interpretations for the SFRCs. YM, on the other hand, has an obligatory definite determiner: bare nouns and SFRCs are only licensed in theme position of existential predicates.

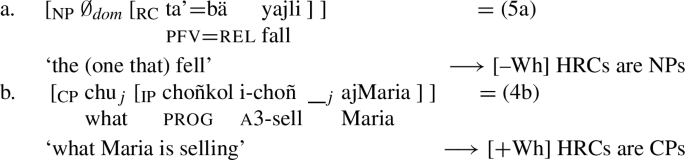

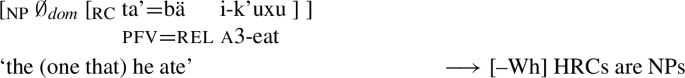

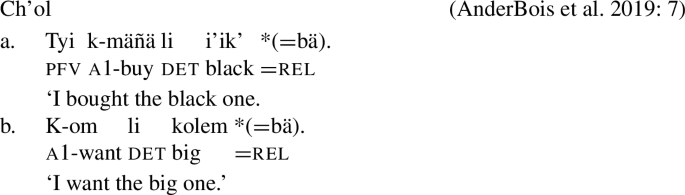

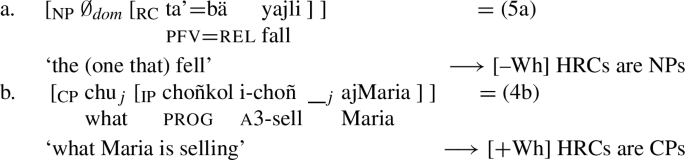

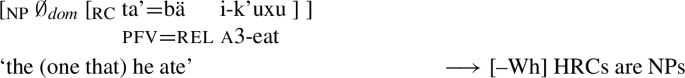

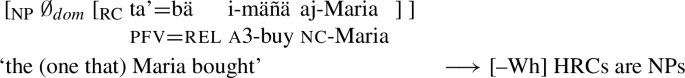

We propose that SFRCs are type-shifted via the same operations available to bare nouns in a given language, thus enriching our understanding of the applicability of definiteness-related type-shifters. Taken together, these findings challenge the restrictive nature of ι in Chierchia (1998) and Dayal (2004), showing that a more nuanced picture is needed to capture variation across languages with respect to type-shifters. The analysis is previewed in (6), using data points (5a) and (4b) from above. We use the label [±Wh] to indicate whether the HRC has a wh-word in it. We argue that [–Wh] HRCs are NPs, and thus their distribution parallels that of bare nouns in the language. Whatever type-shifting principles are available for bare nouns in the language are also available for SFRCs. SFRCs are headed by a null nominal head that is anaphoric a discourse salient set: ∅dom. [+Wh] HRCs are CPs, as has been proposed before (e.g., Caponigro 2003, 2004), and thus are subject to different type-shifting principles. Maximality of [+Wh] HRCs comes through a proposed FR-ι, a post-syntactic mechanism to resolve a type-mismatch.

-

(6)

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. We begin with relevant background and overview of HRCs in each language in Sect. 2. We then turn to SFRCs in Sect. 3, demonstrating that SFRCs pattern differently in Ch’ol than they do YM, but that they parallel bare nouns in their respective languages. In Sect. 4, we tie this difference in interpretation and distribution of SFRCs to the presence of an obligatory definite article in YM, but not in Ch’ol. YM marks definites overtly and does not allow bare nouns or SFRCs in most contexts. Ch’ol, on the other hand, allows both bare nouns and SFRCs to be definite and indefinite, depending on the environment. We extend the analysis from Little (2020) for bare nouns to definite and indefinite SFRCs in Ch’ol. In Sect. 5, we turn to FRs (HRCs with overt wh-words) which have a primarily maximal/definite interpretation, in line with a robust cross-linguistic pattern. In Sect. 6 we propose that there is a FR-ι available regardless of whether a language has an overt definite article. We conclude with a summary of the findings and theoretical implications, as well as some cross-linguistic predictions of our analysis for HRCs in Sect. 7.

2 Headless relative clauses in Yucatec Maya and Ch’ol

This section begins with relevant background on YM and Ch’ol in Sect. 2.1, and then turns to a survey of the four basic types of HRCs in the two languages in Sect. 2.2. We conclude this section by foreshadowing the basic outline of our analysis, to be developed below, that these HRCs require two distinct type-shifters, accounting for their different semantic properties.

2.1 Grammatical overview

Yucatec Maya (YM), or Maaya T’aan, as it is known to speakers, belongs to the Yucatecan branch of the Mayan family of languages. According to the Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas (INALI 2008), YM is the most widely spoken indigenous language of Mexico. The 2020 census (INEGI 2020) states that 774,755 people speak the language in Mexico. The bulk of the population is located in the Yucatan peninsula, with much smaller numbers of speakers in other states of Mexico and other countries including the United States, Guatemala, and Belize with minimal dialectal differences (Bricker et al. 1998).

Ch’ol, known to speakers as Lakty’añ, belongs to the Ch’olan-Tseltalan branch of Mayan languages. It is spoken by 254,715 people (INEGI 2020) in southern Mexico in the states of Chiapas, Tabasco, and Campeche, with most of the Ch’ol-speaking population in Chiapas. It is also spoken by diaspora communities in Mexico and the United States. It is the ninth most spoken language in Mexico (INEGI 2020). There are three mutually intelligible dialects (Tila, Tumbalá and Sabanilla). Data here come from the Tila dialect.

Cited data in both languages come from text corpora (e.g., Vázquez Álvarez and Coon 2019 for Ch’ol and Monforte et al. 2010; Can Canul and Gutiérrez-Bravo 2016; and cited internet sources for YM). All dialects of Ch’ol are represented in Vázquez Álvarez and Coon (2019): Tumbalá, Tila, and Sabanilla. Uncited data from both languages comes from consultations with native speakers. Three speakers of Ch’ol were consulted (two of the Tila dialect, one of the Tumbalá dialect). Uncited data found here is reported from the Tila dialect. There was no difference in terms of the empirical patterns reported here between the dialects. Three speakers were consulted for any uncited YM data.

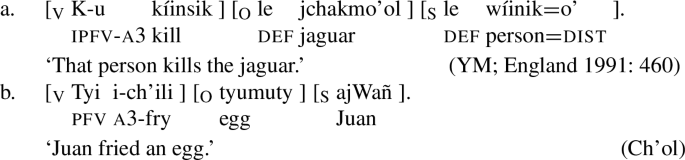

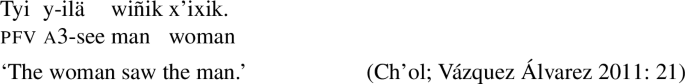

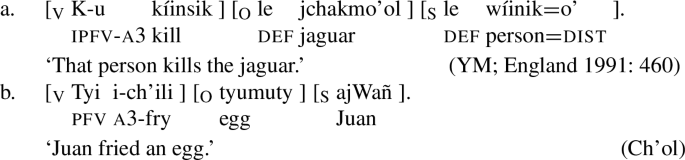

Like other Mayan languages, YM and Ch’ol are head-marking, ergative-absolutive languages with basic verb-initial word order (see Bennett et al. 2016; Aissen et al. 2017 for general Mayan overviews). VOS is described as one of the basic word orders in both languages (see e.g., Durbin and Ojeda 1978 for YM and Coon 2010 for Ch’ol), illustrated in the examples in (7). We adopt the theory-neutral labels “Set A” and “Set B” for person markers in YM and Ch’ol, following Mayanist tradition. Set A markers index ergative subjects and possessors, and Set B index absolutive arguments. There are no overt reflexes of third person absolutives and as such we do not include third person absolutive marking in our glosses. We have not fully parsed out stem-internal morphology that is not relevant to the discussion at hand (e.g., derivational morphemes, stem-final “status suffixes”).

-

(7)

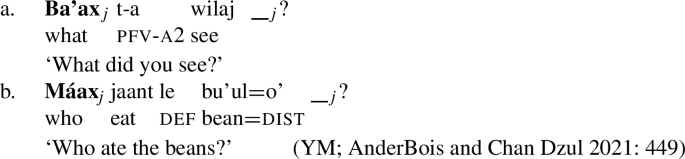

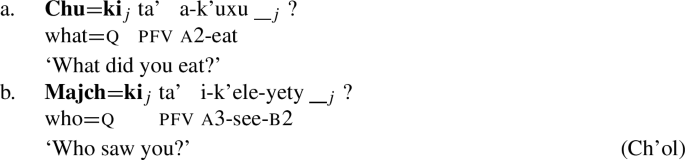

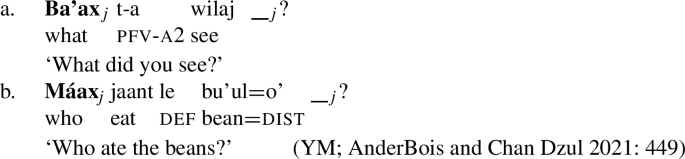

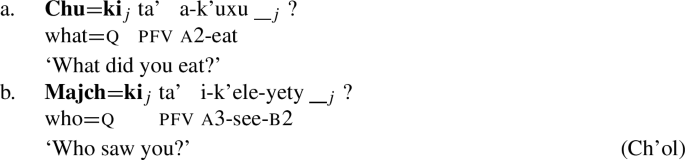

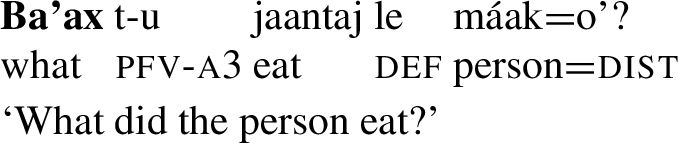

While arguments follow the verb in discourse-neutral contexts, YM and Ch’ol are like other Mayan languages in having preverbal positions for topics, foci, wh-elements, and relativized nouns (see discussion of information structure in Mayan in Aissen 1992, 2017). Wh-interrogatives must appear in a clause-initial A′-position in both languages, as shown by the YM and Ch’ol examples in (8) and (9). In-situ wh-interrogatives and multiple wh-questions are ungrammatical in both YM and Ch’ol (AnderBois and Chan Dzul 2021; Vázquez Álvarez and Coon 2021).

-

(8)

-

(9)

In YM, interrogative wh-words look morphologically the same as the wh-words that appear in FRs (AnderBois and Chan Dzul 2021). Interrogative wh-words in Ch’ol occur with the =ki clitic, glossed as ‘q’ in (9). As seen in examples like (4b) above, wh-words in Ch’ol FRs appear without this clitic, which Vázquez Álvarez and Coon (2021) take to be generated in interrogative C0; FRs involve the same A′-movement of a wh-word, but to the specifier of a non-interrogative CP (see (6b)), discussed further below.

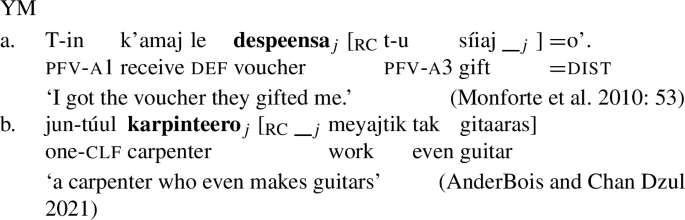

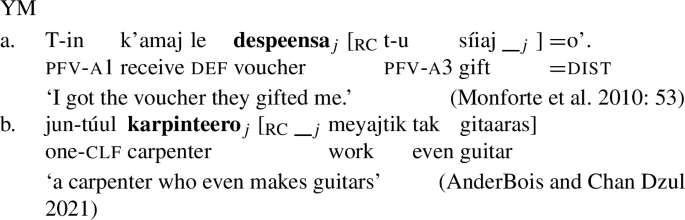

Turning now to relative clauses, headed relative clauses in YM and Ch’ol are externally headed, with the relative clause typically following the nominal. In YM, there is no overt complementizer or relativizing element present for relativized core arguments. Examples from YM are given in (10) with the noun head bolded.

-

(10)

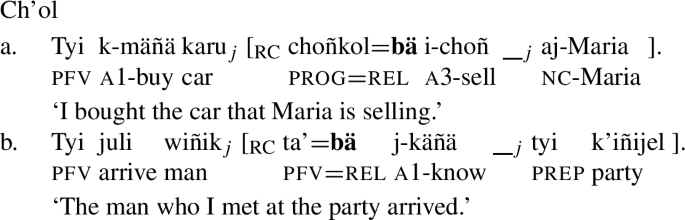

Unlike YM, Ch’ol has a relativizing morpheme, the second-position clitic =bä. This clitic is borrowed from neighboring Mixe-Zoquean languages and is required in argument relativization (Martínez Cruz 2007; Zavala 2007), as shown below. As exhibited in (11), heads are external to the relative clause, and the relative clause usually appears postnominally (see Coon 2018 on prenominal relatives in Ch’ol). The perfective marker tyi surfaces as ta’ with the enclitic =bä.

-

(11)

As the examples above illustrate, wh-words or other relative pronouns are not used when core arguments are relativized in either Ch’ol or YM. Relativization of obliques (e.g., locative or temporal relatives) require a wh-word. These are not discussed further here, but see Vázquez Álvarez and Coon (2021) and AnderBois and Chan Dzul (2021) for examples and discussion.

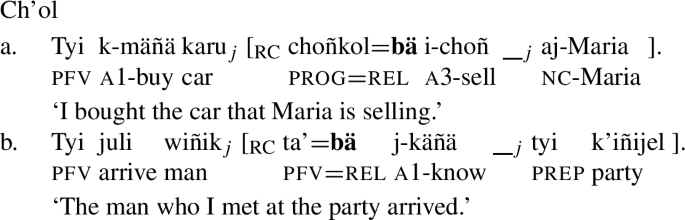

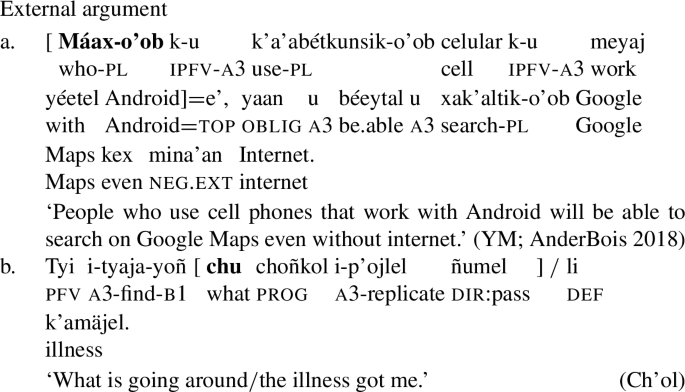

2.2 Four types of headless relative clauses

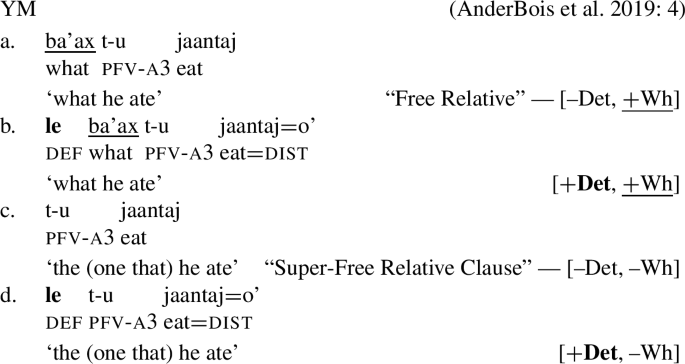

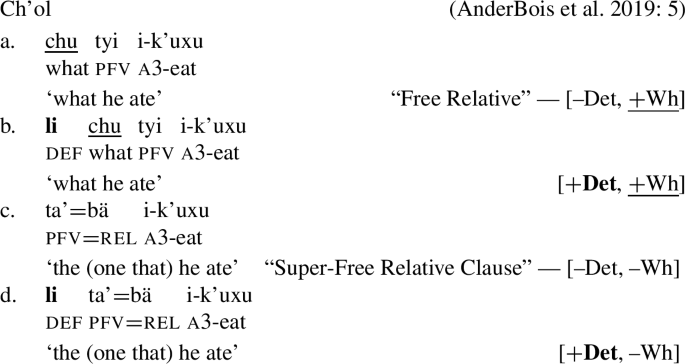

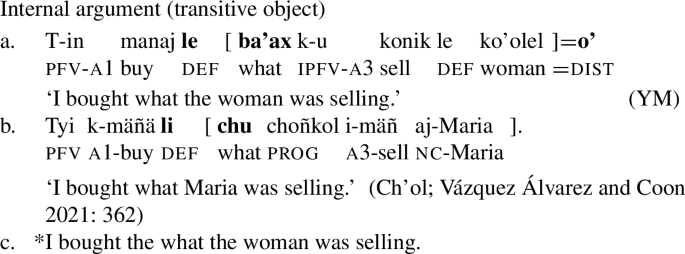

Having surveyed the relevant grammatical properties, we turn now to HRCs. We follow the work in Caponigro et al. (2021) in using the features [±Det] and [±Wh] throughout the paper to indicate whether HRCs have an overt determiner and/or a wh-word. HRCs in both languages have four forms, corresponding to each possible combination of values of the features [±Det] and [±Wh].Footnote 2 For the most part, we translate the [–Wh] HRCs with ‘the (one that)...’ or ‘a (person/thing that)...’ in order to differentiate them from their [+Wh] counterparts.

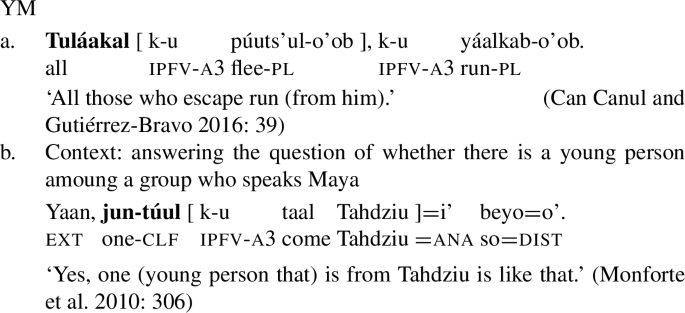

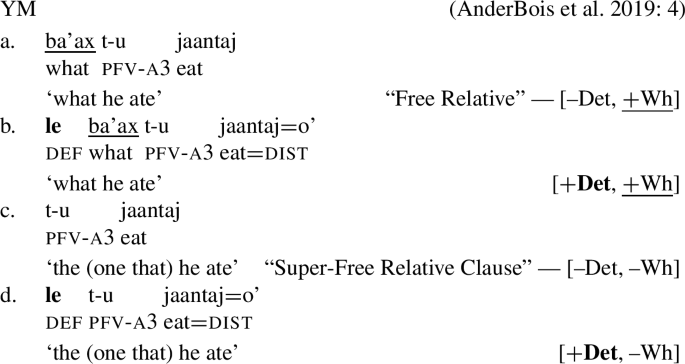

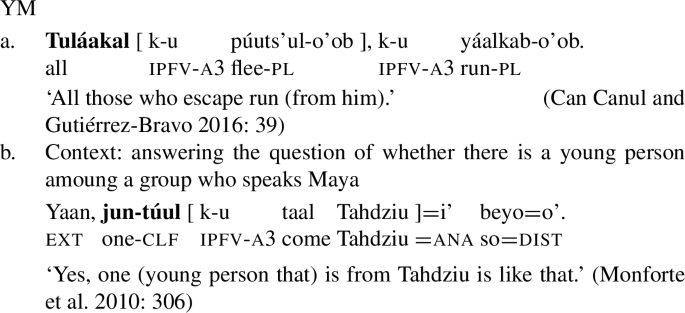

Beginning with YM, we find all four HRCs in (12). Each can be translated into English as ‘what he ate,’ though we will see below that there is variation in both the semantics and distribution of these forms. The first example in (12a) is an instance of a [+Wh] HRC, also referred to in the literature as a FR. FRs can also appear with determiners as in (12b). HRCs may also appear without a wh-word as in (12c) and (12d). The SFRC in (12c) bears neither a wh-word nor a determiner, and is formally identical to a full clause (i.e., ‘He ate it’). The same form can be introduced by a determiner, as in (12d). As we will see below, (12c) is only available in the theme position of existential predicates, a fact we will tie in to the available type-shifters in the language.

-

(12)

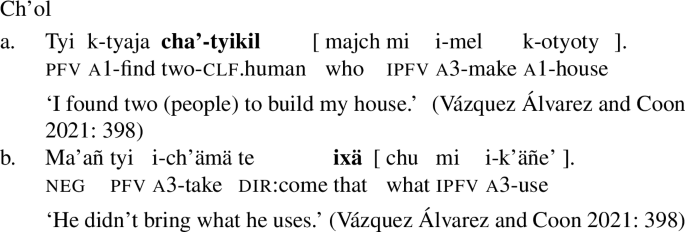

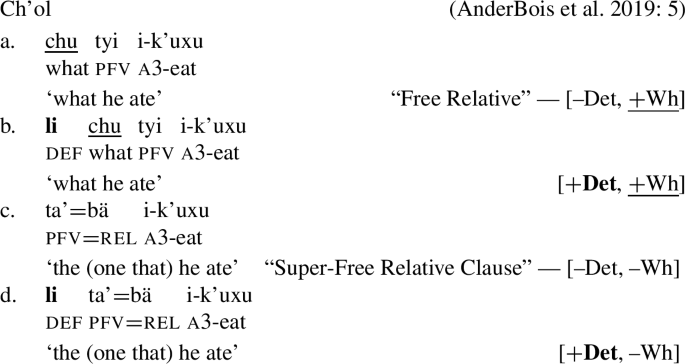

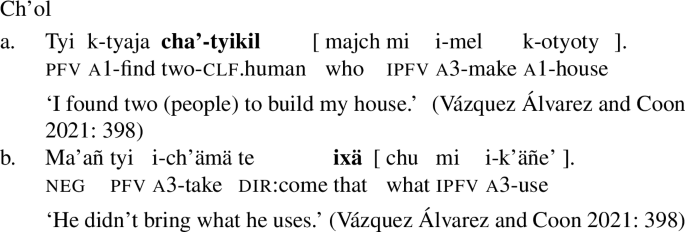

Ch’ol, like YM, also has four morphologically distinct HRCs, occurring with and without a wh-word and determiner, seen in (13). Ch’ol’s relativizing clitic =bä—also present on the headed RCs from (11) above—appears obligatorily on [–Wh] HRCs, exhibited in (13c) and (13d) below.

-

(13)

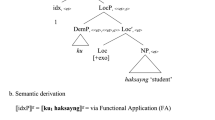

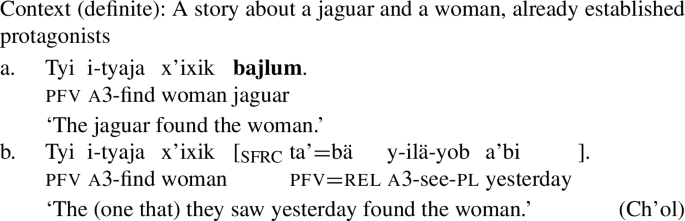

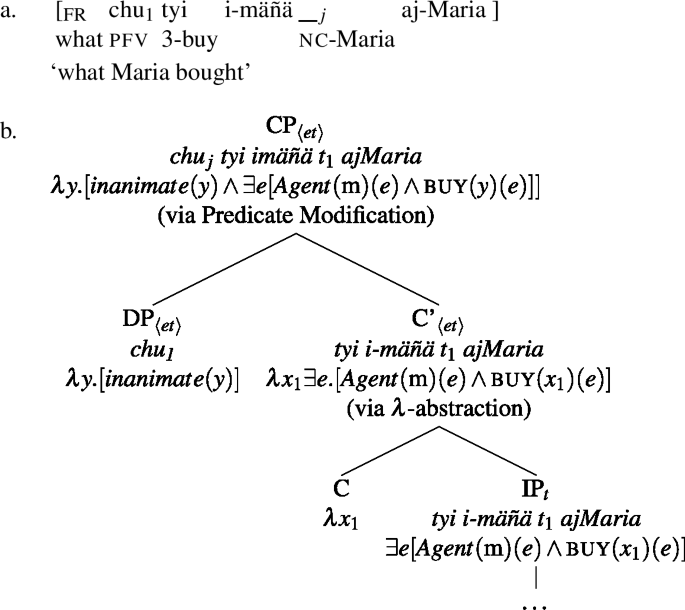

To foreshadow the analysis, we will argue below that the [+Wh] FRs in (12a) and (13a) correspond to CPs, in which the wh-word has undergone A′-movement to Spec,CP. These CPs may combine with a definite article, as in (12b) and (13b); be in theme position of existential or certain other verbal predicates; or may be type-shifted by the dedicated CP-selecting type-shifter FR-ι, available in both languages as a last-resort mechanism. Schematically, the Ch’ol [+Wh] FR in (13a) has the structures in (14). The corresponding YM form is parallel.

-

(14)

We argue that the [−Wh] HRCs in (12c)–(12d) and (13c)–(13d) above are entirely different creatures. The SFRCs in (12c) and (13c) have structures identical to headed relative clauses, but with a particular null nominal head (∅dom) anaphoric to a discourse salient set, properties of which are discussed in further detail below. The structure of the Ch’ol SFRC in (13c) above is schematized in (15); again the YM structure is parallel. These NPs may also combine with determiners, as in the [+Det, –Wh] forms in (12d) and (13d).

-

(15)

Overt morphological evidence for this analysis comes from the obligatory presence of the =bä second-position clitic in Ch’ol. Further evidence for this proposal, discussed in detail in the following section, comes from their distribution: the SFRCs pattern with bare nouns in their respective languages in terms of the availability of (in)definite readings in different syntactic positions. In Ch’ol, a language without obligatory determiners, SFRCs have access to the nominal type-shifter, N-ι. YM, on the other hand, is a language with obligatory determiners and—we claim—no access to N-ι. As predicted, the distribution of SFRCs in YM is thus highly restricted.

In the following sections, we discuss the semantics of each type of HRC in argument position. We adopt previous work for arguments that li in Ch’ol and le…=o’ in YM contribute definiteness (see Vázquez Álvarez 2011 and Little 2020 for Ch’ol, and Vázquez-Rojas Maldonado et al. 2018 for YM). We focus in on the interpretational differences of the two main types of HRCs without determiners: [+Wh] FRs and [–Wh] SFRCs. We show that FRs which we argue to be CPs are, outside of existential constructions, definite and maximal, which largely parallels cross-linguistic work on these constructions. SFRCs, on the other hand, parallel the distribution and interpretation of bare nouns in each language. We propose that this lends support to an analysis in which these are NPs, structurally identical to headed relative clauses, but headed by a null nominal element.

3 Bare nouns and [–Wh] headless relative clauses

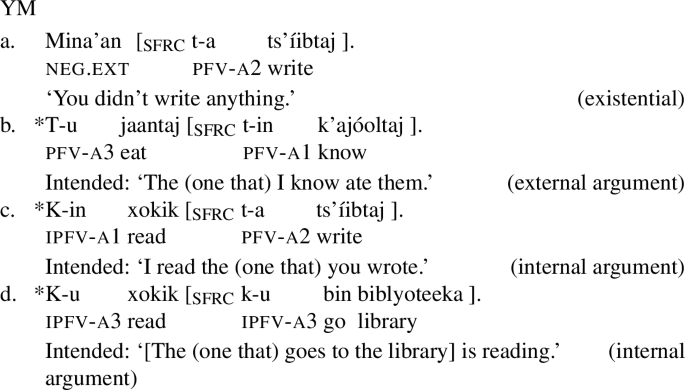

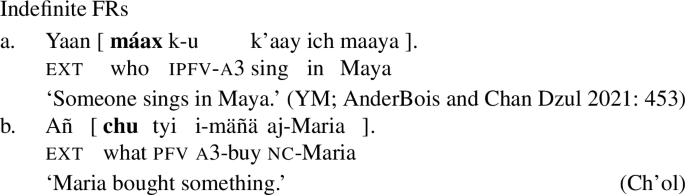

Caponigro et al. (2021) labels HRCs in (16) as SFRCs due to the fact there is neither a wh-word nor a determiner; these are [–Det, –Wh] in the notation used here.

-

(16)

In Sects. 3.1 and 3.2, we provide evidence that these SFRCs in YM and Ch’ol entirely parallel the distribution and interpretation of bare nouns in each language. We will argue below that their respective distributional patterns are due to the presence or absence of an obligatory definite article within the two languages. In Sect. 3.3 we briefly examine the contribution of determiners in [–Wh] HRCs in both languages, before turning to our analysis in the following section.

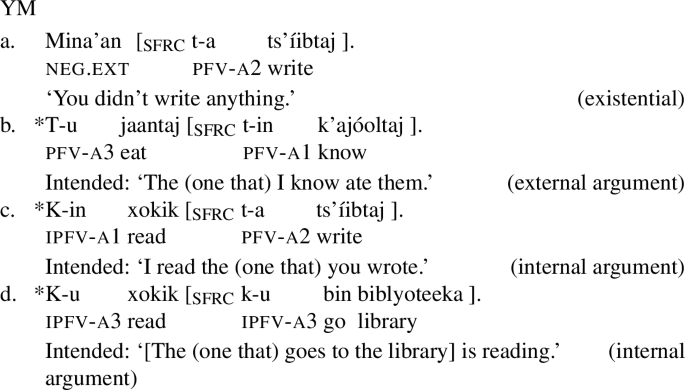

3.1 Bare nouns and super-free relative clauses in Yucatec Maya

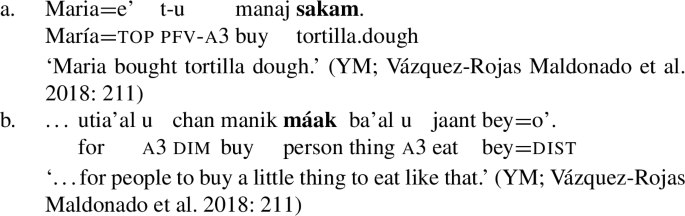

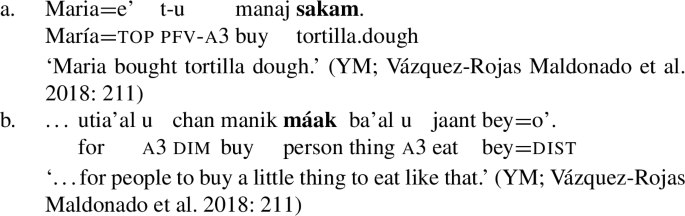

Bare nouns are licensed in very restricted environments when in argument position in YM. They can either have a mass interpretation as in (17a) or collective interpretation when licensed by a quantificational or irrealis environment, such as when introduced by utia’al in (17b).

-

(17)

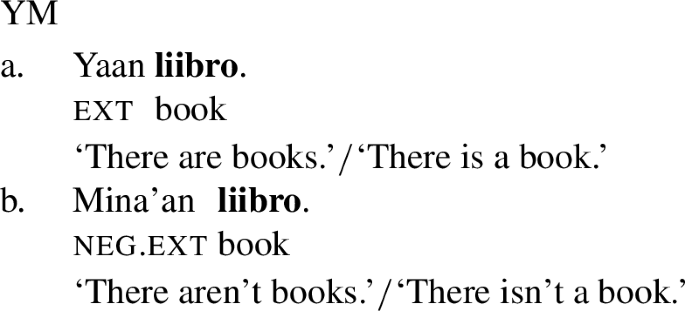

Otherwise, we only find very restricted cases of bare nouns and they are never interpreted as definite. They may be existential indefinites with the existential predicate yaan or its negative counterpart mina’an, as seen in (18).

-

(18)

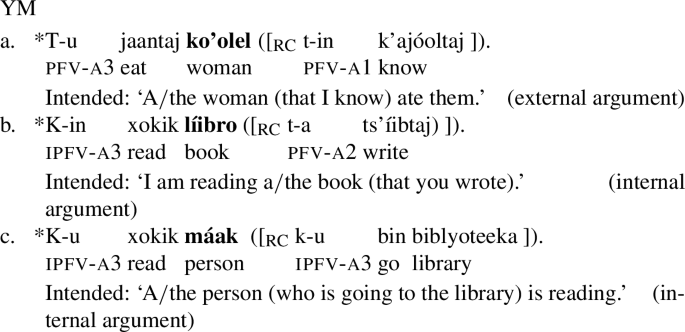

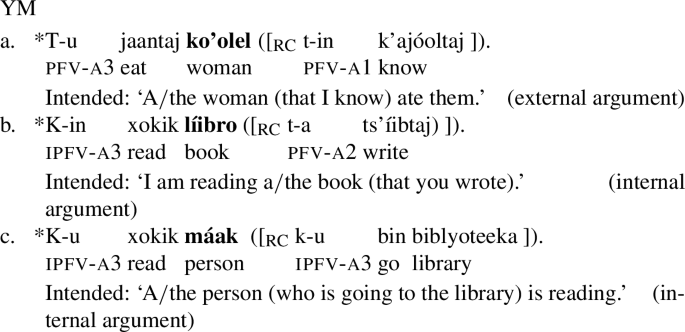

Apart from the examples above, bare count nouns are ungrammatical in argument position as shown in (19), even when modified by a relative clause (given in parentheses).

-

(19)

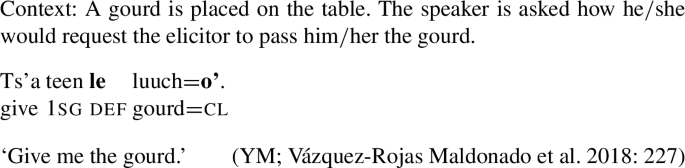

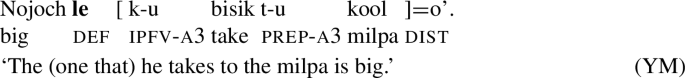

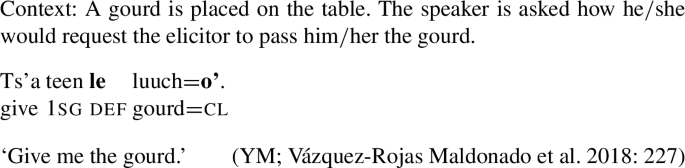

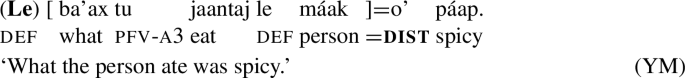

Vázquez-Rojas Maldonado et al. (2018) provide extensive diagnostics demonstrating that YM has an obligatory definite article, le...=o’. An example of a nominal with this article is given below in (20); the definite article is obligatory in this context.

-

(20)

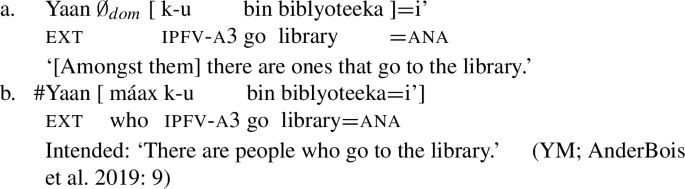

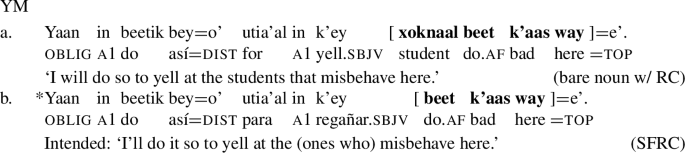

We see the same pattern for SFRCs in YM as we saw for bare count nouns: SFRCs are possible in theme position of existential predicates but are ungrammatical in other positions, illustrated in (21).Footnote 3 Outside of existential contexts, SFRCs are not possible as external arguments or internal argument (transitive objects and unaccusative subjects).

-

(21)

A summary of the distribution and interpretation of bare nouns and SFRCs is give in Table 1. As can be seen here, their distribution and interpretation is entirely parallel.

3.2 Bare nouns and super-free relative clauses in Ch’ol

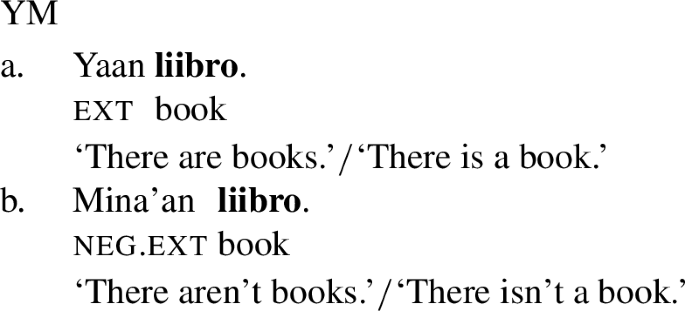

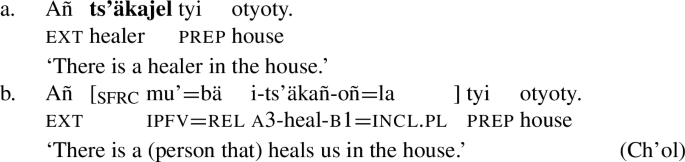

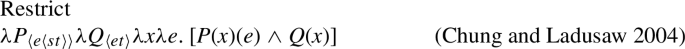

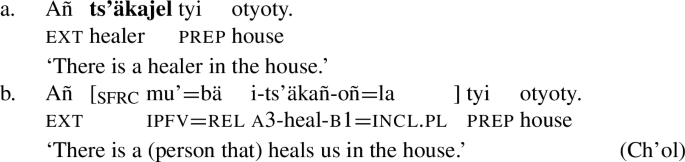

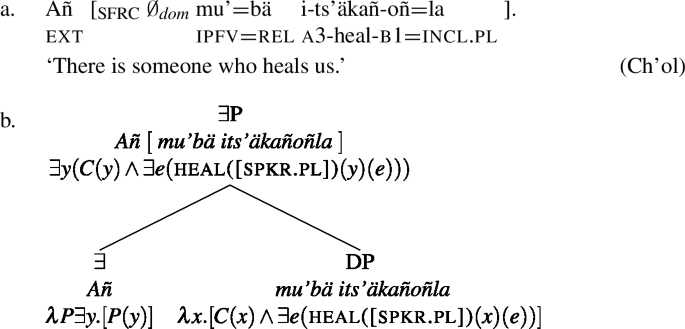

As seen in YM above, in Ch’ol, nouns and SFRCs may may appear in theme position of existential predicates such as añ in (22a) and (22b).

-

(22)

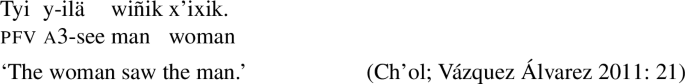

For argument positions, however, both bare nouns and SFRCs differ substantially from what we have seen for YM. First, bare nouns may be arguments in Ch’ol, as in the sentence in (23). Vázquez Álvarez (2011) translates both bare nouns as definite in (23).

-

(23)

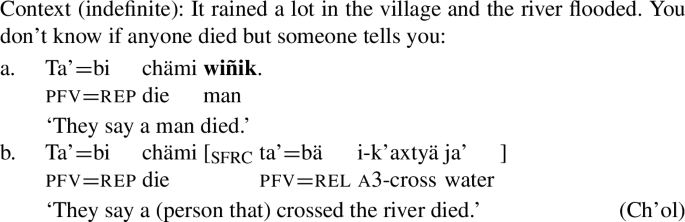

Little (2020) provides evidence that while a definite interpretation is available for all bare arguments, the positions in which nouns may be interpreted as indefinite in Ch’ol are syntactically restricted. Bare nouns as internal arguments (unaccusative subjects and transitive objects) can be definite or indefinite. Bare nouns as external arguments (transitive and unergative subjects) are always definite. We provide evidence that SFRCs show the same syntactic variation in their interpretation that bare nouns do.

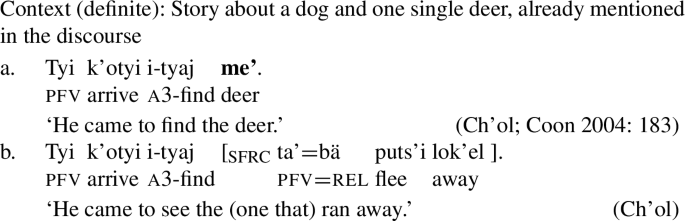

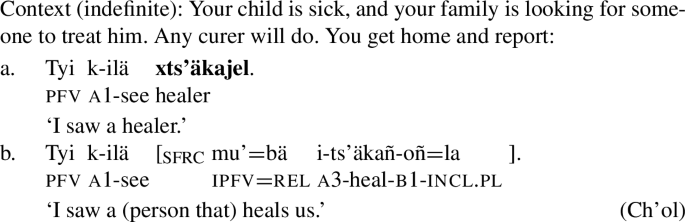

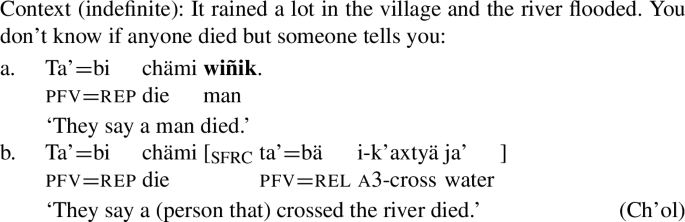

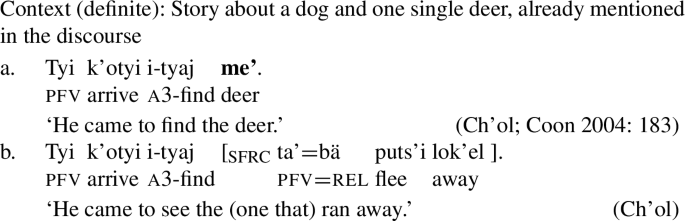

Examples (24)–(27) show instances of SFRCs and bare nouns in internal argument position. In (24), we see an instance of a definite bare noun as an internal argument as well as a definite SFRC. In the context, the deer is an established discourse referent, referred to by the bare noun in (24a), and by the SFRC in (24b). Examples (25) and (26) show that internal arguments (unaccusative subjects and transitive objects) can be indefinite, as can SFRCs in the same position. The examples in (27) show that bare nouns and SFRCs can receive definite interpretations when appearing as unaccusative subjects.

-

(24)

-

(25)

-

(26)

-

(27)

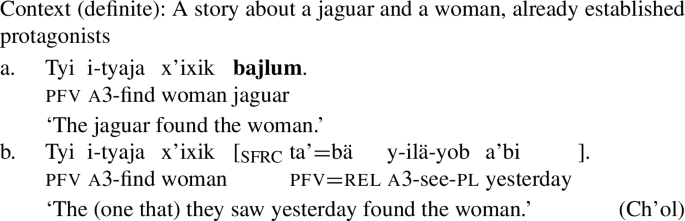

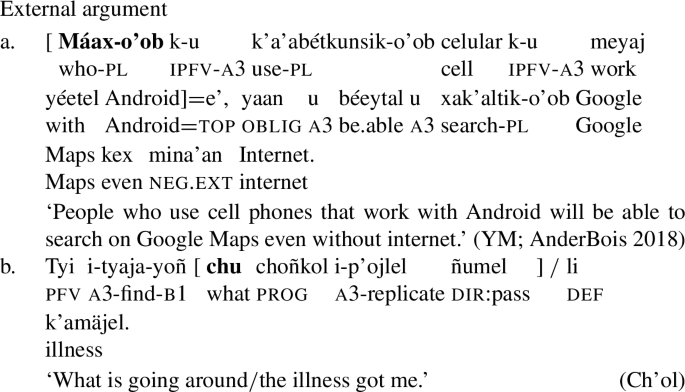

With external arguments, the subject always receives a definite interpretation. Examples with transitive subjects are shown in (28).

-

(28)

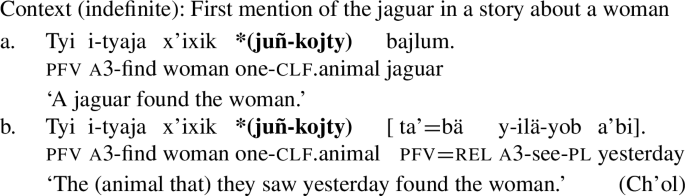

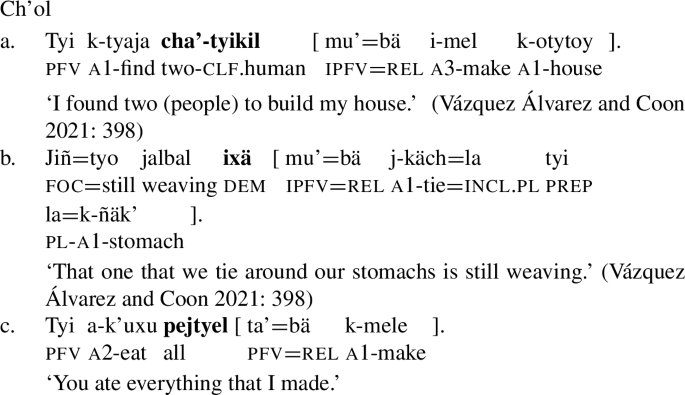

In order to generate an indefinite interpretation for an external argument, the numeral juñ ‘one’ plus the appropriate numeral classifier obligatorily appears, as seen with the transitive subjects in (29a) and (29b).

-

(29)

A summary of the findings for Ch’ol is given in Table 2. Here we observe that again, bare nouns and SFRCs behave entirely parallel to each other with respect to their distribution and possible interpretations. Internal arguments can have both definite and indefinite interpretations, but external arguments can only have definite interpretations. While not shown due to space constraints, the interpretation of bare nouns modified by relative clauses in Ch’ol also follows the same pattern reported in Table 2 for bare nouns and SFRCs.

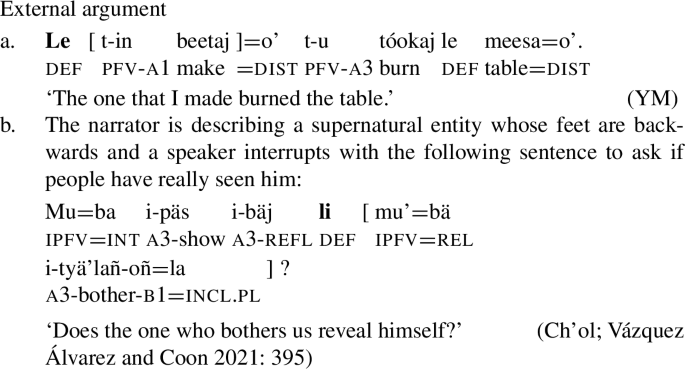

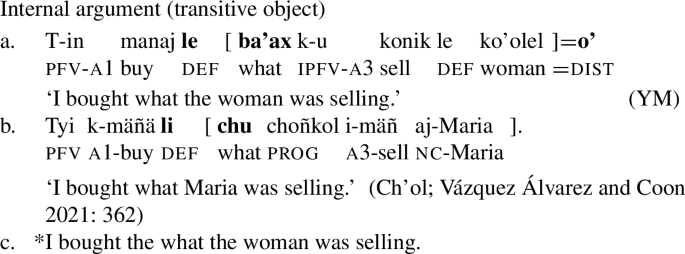

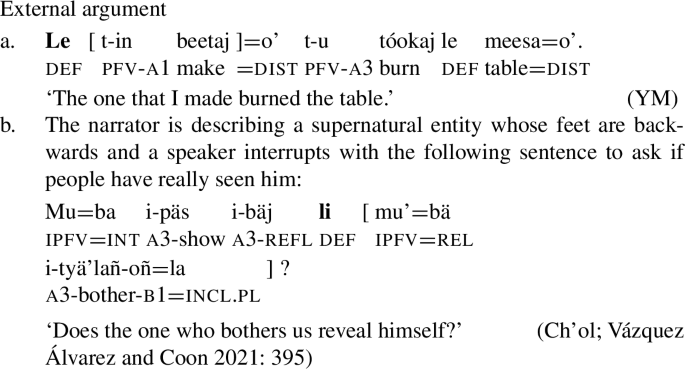

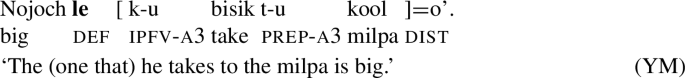

3.3 [+Det, –Wh] headless relative clauses

One distinctive feature of HRCs in Mayan languages including Ch’ol and YM is that they allow a full range of determiners to co-occur with HRCs. We demonstrate this here for the [–Wh] HRCs, the focus of this section, though we will see the same thing below for [+Wh] HRCs. Examples are given here for external arguments. Determiners can also appear in HRCs that are in internal argument position. Note that if the determiner is removed from (30a) in YM, the example would be ungrammatical; in (30b) in Ch’ol if the determiner is removed the example is still grammatical. Further work is needed to understand the contribution that the determiner makes in optional contexts in Ch’ol.

-

(30)

For the examples above, the determiner is a definite article, and therefore looks somewhat similar to what Citko (2004) has dubbed “light-headed relative clauses” in Polish. In contrast to Polish, however, both YM and Ch’ol allow for the full range of determiners that are available with nouns in the language, rather than a specific grammaticized set. Crucially, these determiners include demonstratives, quantifiers, and numerals (numerals which do not otherwise allow for pronominal uses). Examples are given in (31) and (32).

-

(31)

-

(32)

Again, [–Wh] HRCs pattern with bare nouns in each language: they appear with the full range of determiners possible on nouns.

3.4 Empirical summary

In this section, we have presented the major properties of [–Wh] HRCs. We have seen that within both YM and Ch’ol, their behavior parallels that of bare nouns very closely. We have shown that SFRCs pattern with bare nouns in two key respects. First, they combine with the same range of determiners of various kinds (the [+Det, –Wh] HRCs from Section 3.3). Second, when occurring without a determiner, as [–Det, –Wh] HRCs (i.e., the SFRCs from Sect. 3.1–3.2), they show the same distribution and range of interpretations in each language, as summarized in Table 3. YM disallows bare (count) nouns in all positions except in theme position of the existential predicate, this parallels the behavior of SFRCs. In Ch’ol, bare nouns are possible in all positions, but their possible interpretations vary depending on their syntactic position.

In the next section, we take this pattern to provide evidence to the range and applicability of type-shifters and evidence for a particular syntactic structure of SFRCs, one that parallels headed relative clauses.

4 Super-free relative clauses are NPs

We begin with an analysis for the [–Det, –Wh] SFRCs, arguing that the type-shifting and argument-forming principles available to nouns in a given language also apply to SFRCs. The analysis for [+Wh] HRCs in Sect. 6 will rely on pieces of the proposal we put forth for SFRCs here.

4.1 The gap in super-free relative clauses

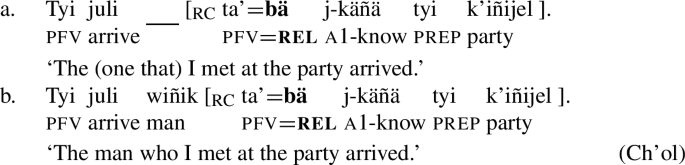

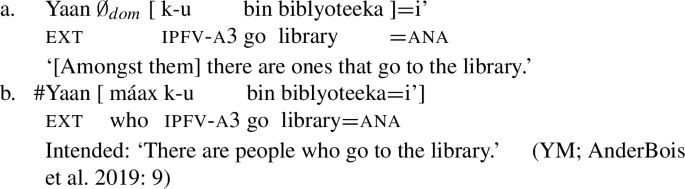

Recall that SFRCs have similar morphological properties to headed relative clauses. This is especially apparent in Ch’ol as Ch’ol has a relative clause marker =bä, shown in (33). These two clauses are identical, except that where the head noun wiñik ‘man’ appears in (33b), there is a gap in the SFRC in (33a).

-

(33)

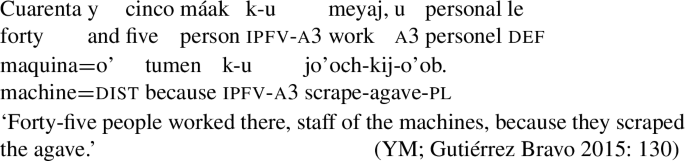

We propose that the gap corresponds to a null nominal head anaphoric to a discourse salient set, which we represent as ∅dom below. We provide evidence that this null element in the SFRC in (33a) is of semantic type 〈et〉, like nouns. However, instead of denoting some set of individuals with a lexically specified property P, as would be expected for the head of a relative clause, we provide evidence that the set of individuals that ∅dom denotes is anaphoric to some salient set in the discourse, C.Footnote 4 This is in contrast to what we will propose below for [+Wh] HRCs, which have a sortal domain, determined by the wh-word.

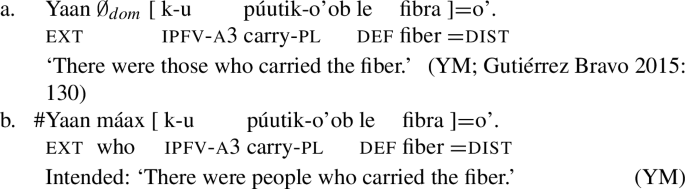

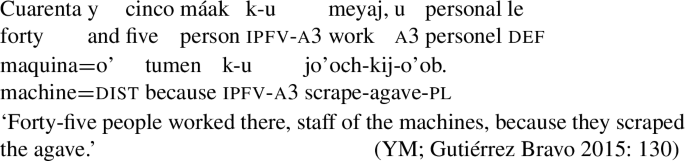

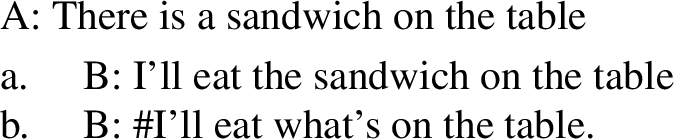

Clear evidence that the gap in SFRCs is anaphoric to a discourse-salient set comes form the following minimal pair in YM. The first sentence in (34) is continued in (35). The felicitous continuation in (35a) indicates that there were those who carried fiber amongst the group of forty-five people mentioned before. In contrast, speakers report that (35b), which is a [+Wh] HRC, sounds strange because it seems as if it is introducing another group and not the group of forty-five mentioned in the first sentence.

-

(34)

-

(35)

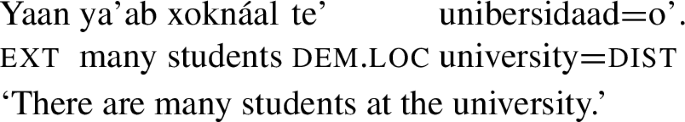

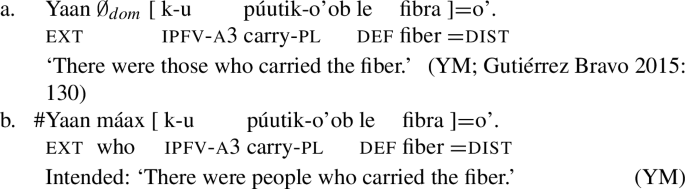

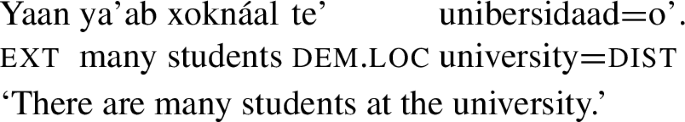

Another example is shown below, where (37) is a continuation of (36). Here, the [–Wh] HRC is in theme position of the existential predicate yaan in (37). As above, the [+Wh] HRC in (37b) is infelicitous; it does not pick out students from the group originally introduced in (36), but rather sounds as if a new group of students is being discussed. What is notable here is that the NPs are existential, not definite. It is thus only the domain that is anaphoric in the examples in (35a) and (37a).

-

(36)

-

(37)

In contrast, [+Wh] HRCs sound more natural in a context without a previously mentioned set, for example at the beginning of a conversation in (38).

-

(38)

Ch’ol parallels the data for YM; for reasons of space we do not provide it here.

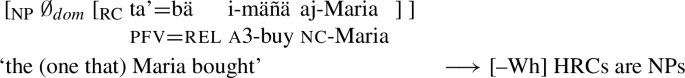

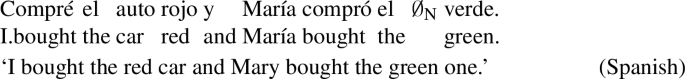

Lastly, there is evidence that [–Wh] HRCs in YM and Ch’ol are not instances of nominal ellipsis, contra what Gutiérrez Bravo (2012, 2015) has posited for YM.Footnote 5 For instance, in Spanish it has been argued that there is nominal ellipsis in the following example where the noun auto is elided in the second conjunct, represented as ∅N.Footnote 6

-

(39)

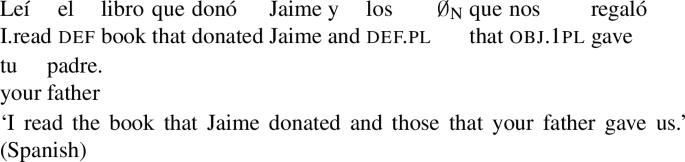

In nominal ellipsis like (39) for Spanish, the gap requires the semantics of a noun to be a property. That is, ∅N = { x: x is a car }. For [–Wh] HRCs, we have proposed that the gap is a salient set of entities in a discourse. In most cases, there is a common property in the members of the set (students or workers, as in the examples above). There are people among those workers who carried the fiber; the interpretation is not ‘There are workers who carried fiber’. However, it is not necessarily the property that is relevant for [–Wh] HRCs in Ch’ol and YM, but rather being part of a particular salient group or set that just so happens to have this property within a particular situation. In contrast, for nominal ellipsis in Spanish, only that property is necessary—the elided nominal does not need to be the same entities previously mentioned. In Spanish in (40), the elided nominal, ∅N has the property of being a book, but the interpretation and use of the plural determiner makes it clear that the books denoted by the elided noun are not the same as the previously mentioned book.

-

(40)

Ch’ol offers clear morphological evidence against a simple nominal ellipsis account via its relative clause clitic =bä. As observed above, the clitic =bä occurs in [–Wh] relative clauses both with and without an overt head (see (13c) and (13d) above). As seen in (41), Ch’ol requires the presence of =bä in constructions parallel to the Spanish examples above. This provides evidence that these constructions involve relativization, just like the SFRCs, which also appear obligatorily with the =bä clitic.

-

(41)

There is no definitive evidence morphosyntactically in YM, but neither is there evidence against the hypothesis for the relative clause analysis, or evidence that there is a difference between these constructions in the two languages. As such, we assume here that the same analysis applies to YM. Thus, we maintain that the [–Det, –Wh] SRFCs are NPs with a null head anaphoric to some previously mentioned set, represented as C in our semantics.

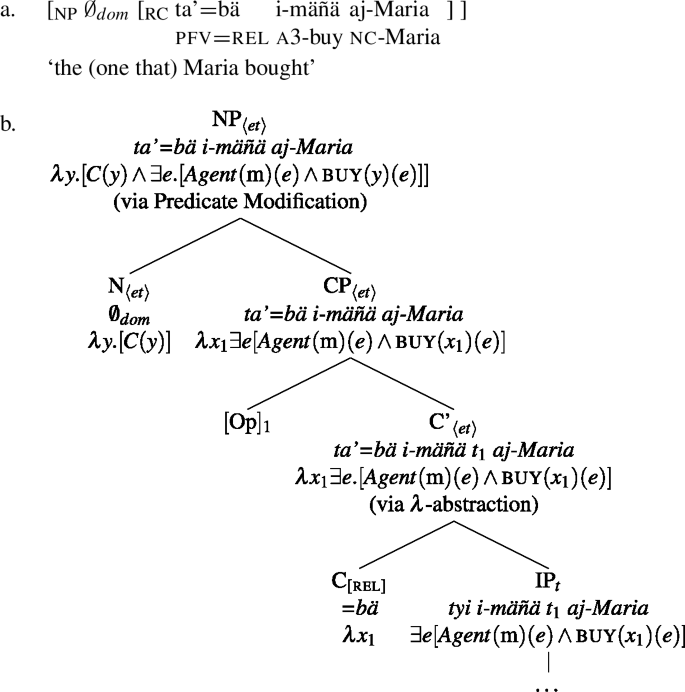

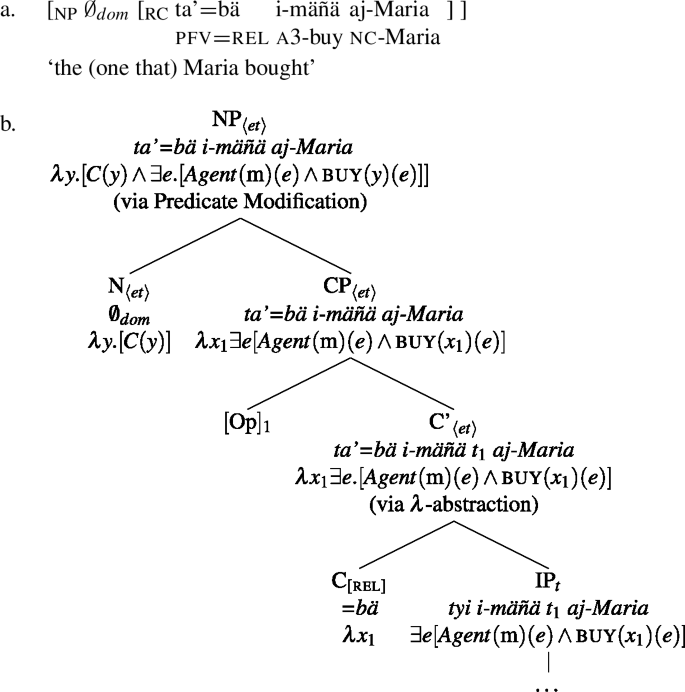

The SFRCs have structures identical to headed relative clauses, but with ∅dom occupying the position of the head of the relative clause. The structure of a Ch’ol SFRC is schematized in (42); again the YM structure is parallel. The SFRC ‘the (one that) Maria bought’ is the intersection of some discourse salient set of objects and that object or objects that were bought by Maria. The details of the analysis are given in the next section.

-

(42)

4.2 Analyzing super-free relative clauses

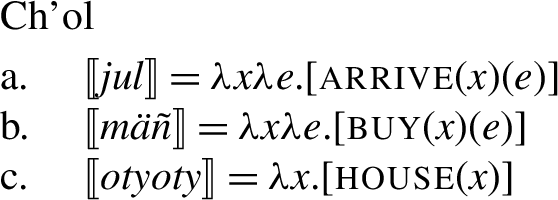

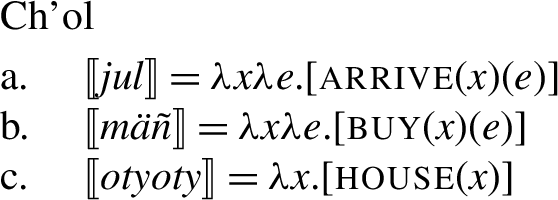

We adopt a neo-Davidsonian approach in which verbs are predicates of events; denotations are given in (43) for unaccusative and transitive verbs and nouns. External arguments are generated in Spec,VoiceP and are not part of the denotation of the verbal predicate, following Kratzer (1996). Denotations for the Ch’ol unaccusative verb jul ‘arrive’ and the transitive verb mäñ ‘buy’ are given in (43a) and (43b). We assume that nouns are type 〈et〉, shown for the noun otyoty ‘house’ in (43c).Footnote 7

-

(43)

Our proposed syntax and semantics for SFRCs like the one repeated in (44a) is given in (44b). As proposed above, NP is headed by a null nominal element \(\emptyset _{dom}\), which represents a contextually supplied set C of type 〈et〉, standing in for some set of individuals supplied by the context. The null nominal element combines with a CP relative clause. Within the relative clause, we introduce a semantically vacuous operator that moves to Spec,CP and leaves a trace of type e. We place Ch’ol’s =bä relativizing clitic in the head of the relative clause, C0, where lambda abstraction takes place. The syntactic structure in (44b) captures the fact that =bä appears in SFRCs and headed relative clauses. At the CP level the N head (∅dom) and CP combine via predicate modification to render the contextually supplied set of individuals such that Maria bought them. In YM, the semantic derivation proceeds in the same way, though C0 is phonetically null as there is no relativizing clitic.

-

(44)

Syntactically, the SFRC is nominal, which is a welcome result as SFRCs behave entirely parallel to the interpretation of bare nouns in the language (see Table 3 above). In Ch’ol, internal arguments can be definite or indefinite depending on context. External arguments are only possible as definite. In YM, bare (count) nouns as well as SFRCs are ungrammatical in argument position; they are only possible as the theme of existential predicates. We detail the proposal for how the possible interpretations are derived for Ch’ol, then discuss YM. The difference between these two languages hinges on the presence of obligatory articles.

4.3 Definite interpretations for super-free relative clauses

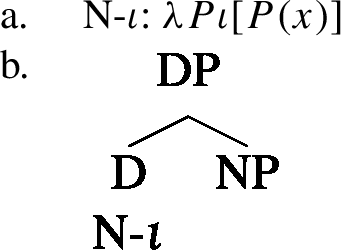

Here we extend the analysis from Little (2020) for bare nouns in Ch’ol to SFRCs. We propose that the definite interpretation, available for both internal and external SFRCs arguments in Ch’ol, is achieved using a nominal ι type-shifter (N-ι) available for both bare nouns and SFRCs (i.e., NPs). This parallels much existing work in which ι is used to semantically type-shift bare nouns so they may serve as arguments (Chierchia 1998; Dayal 2004; Jenks 2018; Despić 2019; Moroney 2021). N-ι applies to nominal arguments, which includes SFRCs, as per our structure above in (44b). This is shown in (45).

-

(45)

We place N-ι in a D0 head in Ch’ol. Positing a syntactic D0 head is in keeping with the fact that there appears to be an an in-progress grammaticalization process of a definite article in the language. In Ch’ol, both bare nouns and nouns modified by the determiner li can refer to definite entities. Little and Vázquez Martínez (2018) and Vázquez Martínez and Little (2020) demonstrate that nominals with and without li can refer to definites in the Tila dialect of Ch’ol, though li tends to appear more often with anaphoric definites. Locating N-ι in D0 is also in keeping with the fact that other determiners can appear in D with SFRCs.

Consequently, N-ι is part of the lexicon in Ch’ol but not in YM as YM has an obligatory definite article. In Ch’ol N-ι is syntactically merged in D and changes the meaning of the structure: it contributes meaning to the nominal and is part of the syntax. We therefore make a distinction between type-shifting as a last resort and N-ι in Ch’ol, which is a covert element merged in the syntax. By comparing YM and Ch’ol, we see that SFRCs in each language behave entirely parallel to the language’s bare nouns, providing empirical support for a type-shifter subject to cross-linguistic variation.

Since N-ι is part of the nominal domain, we propose that it is available to merge with nouns in Ch’ol in any argument position. This correctly captures the fact that both SFRCs and bare nouns in Ch’ol can receive definite interpretations in any syntactic position (i.e, internal and external arguments). We propose that the grammar of YM, on the other hand, simply does not contain N-ι. Instead, both bare NPs and SFRCs require an overt determiner to appear in argument positions outside of existential constructions.

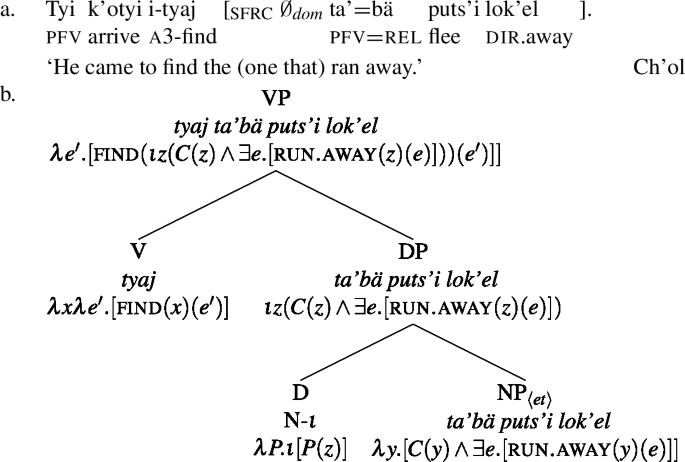

To derive the definite reading for the Ch’ol sentence (46a), the SFRC combines with the N-ι type-shifter, shifting the SFRC of type 〈et〉 to a definite individual of type e that can then be an argument of the verb tyaj ‘find’ in (46b).

-

(46)

4.4 Deriving the indefinite interpretations of Ch’ol super-free relative clauses

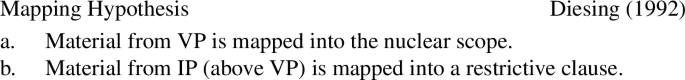

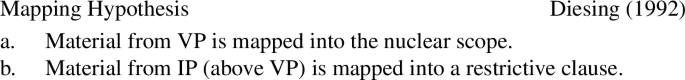

We propose that N-ι is available to repair a type mismatch in SFRCs in any argument position in languages that have it; specifically, it is freely available in languages that allow bare nouns to be definite, like Ch’ol. It is unavailable in YM, accounting for the highly restricted distribution of both bare nouns and [–Det, –Wh] SFRCs. On the other hand, as we observed in Sect. 3, the environments in which SFRCs and bare nouns in Ch’ol can be interpreted as indefinite is more restricted: only internal arguments may receive an indefinite interpretation (recall that YM is yet more restrictive, only allowing this in the presence of an existential predicate). In order to account for low-scope indefinites, we adopt Little’s (2020) analysis of indefiniteness in Ch’ol. Little (2020) draws on Diesing’s (1992) Mapping Hypothesis, in which existential closure occurs at the VP level, shown in (47).

-

(47)

Crucially, existential closure occurs below the external argument. This is a welcome result as it allows for only internal objects (unaccusative subjects and transitive objects, i.e., absolutive arguments) to be interpreted as indefinite. This is in keeping with the empirical picture in Ch’ol summarized in Table 2 above.

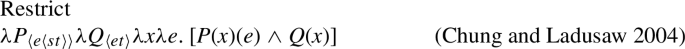

Following Little (2020), we propose that the verb and SFRC combine via Chung and Ladusaw’s (2004) Restrict in (48).

-

(48)

This analysis capitalizes on the notion that indefiniteness in Ch’ol is an instance of pseudo noun incorporation, accounting for the generalization that bare NP objects must be adjacent to the verb (e.g., Massam 2001 for Niuean and Coon 2010 for Ch’ol). The theme argument is then existentially closed at the VP, as per the Mapping Hypothesis (Diesing 1992). Structurally constraining existential closure to the VP correctly predicts the interpretational possibilities of bare nouns and SFRCs in Ch’ol. Implicit in Chung and Ladusaw (2004) is that Restrict is invoked to apply to syntactically nominal arguments. A derivation for an indefinite object SFRC is given in (49b) for Ch’ol, using the SFRC semantics from (44b) from above in object position.

-

(49)

Recall that indefinite SFRCs are not possible in the external argument position, which is predicted by this approach. The SFRC is of type 〈et〉, and in external argument position it cannot combine with the predicate via Function Application due to a type clash. The SFRC also cannot combine with the predicate via Restrict since it is only compatible at the VP level with internal arguments. The only possibility is to resolve the type clash with the dedicated nominal type-shifter N-ι, correctly predicting that only definite SFRCs are possible in external argument position in Ch’ol.

In addition to VP-level existential closure of SFRCs, existential predicates can also provide the existential semantics, generating an indefinite interpretation. This is shown for a Ch’ol indefinite in (50b).

-

(50)

YM, in contrast, only allows SFRCs to appear as themes to existential predicates, as in (18) above; we assume the existential predicate existentially binds the unsaturated argument. There is no pseudo-incorporation in YM like there in Ch’ol, accounting for the absence of bare indefinites—and by extension SFRCs—in internal argument position of non-existential predicates. Instead, YM employs overt morphemes to derive indefinite interpretations.

4.5 Type-shifters for bare nouns = type-shifters for super-free relative clauses

In this section, we argued that allowing a dedicated nominal type-shifter, N-ι, to apply to SFRCs just as it does to bare nouns captures the fact that bare nouns and SFRCs behave identically with respect to their distribution and interpretation in Ch’ol. This fact falls out naturally under an account which takes SFRCs to be themselves NPs, albeit with a special null head. As per previous literature on the interpretation of bare nouns (Chierchia 1998; Dayal 2004; i.a.), N-ι is a possible type-shifter in languages that allow bare nouns to be definite, such as Ch’ol. An indefinite interpretation is derived for internal arguments only via existential closure at the VP level and existential predicates. External arguments are generated structurally outside of the VP so only N-ι may apply, accounting for the impossibility of indefinite interpretations for bare external arguments in Ch’ol.

In YM, on the other hand, definite nouns must be marked with an overt definite article, as extensively detailed in Vázquez-Rojas Maldonado et al. (2018). Languages such as YM and English must mark definite noun phrases with an overt morpheme, thus leading researchers to posit that these languages do not have a covert N-ι (Chierchia 1998; Dayal 2004; Moroney 2021; i.a.). This is why SFRC cannot be in argument position: they would induce an irreparable type clash. YM also makes use of the numeral ‘one’ or an existential construction to mark indefinites, demonstrating that, at least for singular count nouns, indefinites must be marked overtly.

Outside of existential constructions, [–Wh] headless relative clauses in YM require a determiner element. In these cases, the semantics of the entire HRC come from the determiner. For instance, in the case of the following examples in YM, the determiner le...=o is a definite article.

-

(51)

As mentioned in Sect. 3.3, not only can definite determiners appear with [+Det, –Wh] HRCs, but numerals, demonstratives and other quantifiers are also possible. This provides evidence that syntactically these behave like headed relative clauses and other NPs, and are not a special type of headless relative (i.e., no special category of “light-headed relative clause” is needed here).Footnote 8

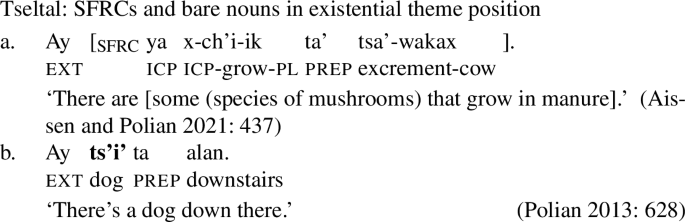

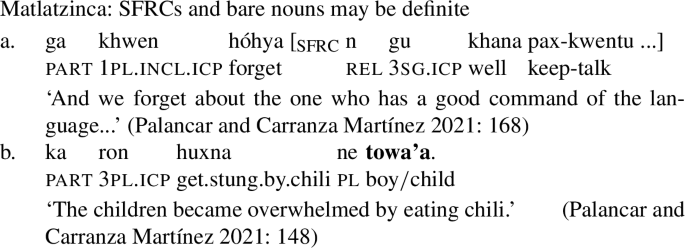

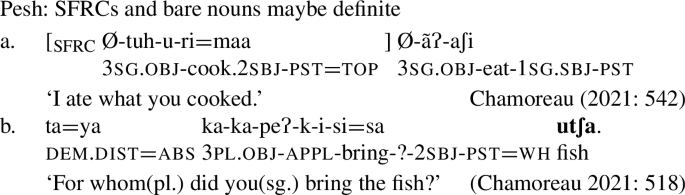

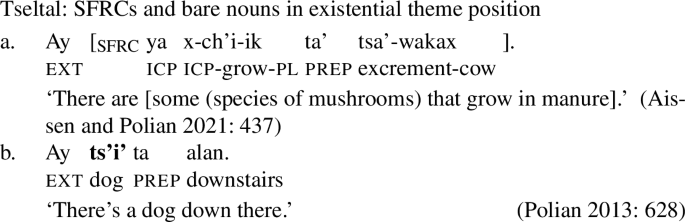

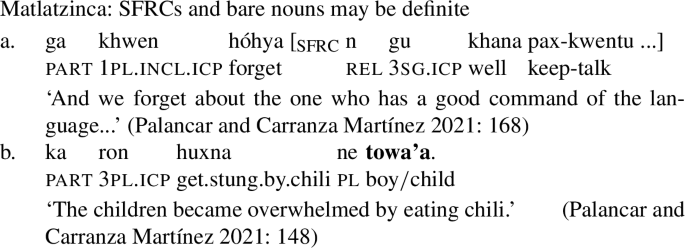

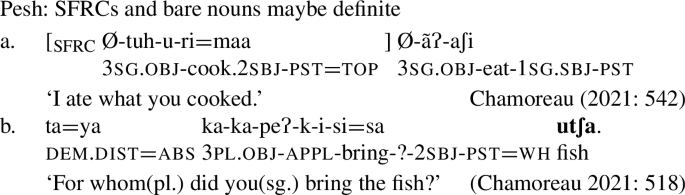

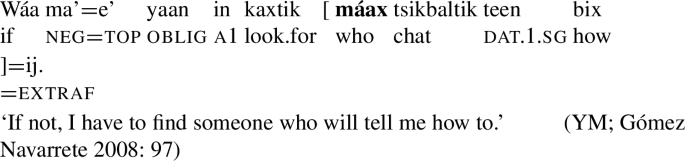

While not all languages have SFRCs (English being one), a recent survey of indigenous languages of Mesoamerica in Caponigro et al. (2021) provides evidence that more generally, when SFRCs are present in a language, their interpretations parallel that of bare nouns in that language. We provide examples below from Tseltal (Mayan), Matlatzinca (Oto-Manguean) and Pesh (Chibchan). In Tseltal (52), we see that SFRCs are possible in theme position of existential predicates, like bare nouns. Otherwise, definite nominals must be marked with a determiner (Polian 2013); a definite reading of SFRC is not possible. In Matlatzinca (53), bare nouns, when plural, and SFRCs, in all contexts, are possible as definite (Palancar and Carranza Martínez 2021). In Pesh (54), SFRCs are possible and their interpretation is definite (Chamoreau 2021). Pesh also allows bare nouns to be definite. Bracketing and bolding below is our own.

-

(52)

-

(53)

-

(54)

While further work needs to be done to determine the details of the syntax and semantics of bare nouns in these languages, this preliminary survey of textual data provides tentative evidence from a wider sample of languages that bare nouns and SFRCs parallel one another in their interpretation and distribution. This adds to our knowledge of the range and applicability of N-ιacross languages: it can apply freely to nouns, whether these are bare nouns or the SFRCs which we argued are headed by a special null nominal, \(\emptyset _{dom}\).

5 [+Wh] headless relative clauses in Yucatec Maya and Ch’ol

We argued above that [–Det, –Wh] SFRCs are syntactically nominal and abide by the same argument-forming principles as bare nouns. This explains why YM does not allow SFRCs to be definite (since YM does not have N-ι in the nominal domain) but Ch’ol does. It also explains why they freely occur with other D0 elements in each language, yielding [+Det, –Wh] HRCs.

This section turns to [+Wh] headless relative clauses, also known as Free Relatives (FRs). FRs pattern similarly cross-linguistically: they have a definite, maximal interpretation unless in theme position of existential or “coming-into-being” predicates (Jacobson 1995; Caponigro 2003, 2004). This consistent pattern leads us to propose that there is a special ι-type-shifter for FRs, distinct from N-ι, and this type-shifter is available regardless of whether a language marks definiteness with an overt article or not (i.e., regardless of language-specific properties of the nominal domain). We begin with FRs with no determiner in Sect. 5.1, turning to their appearance with determiners in Sect. 5.2.

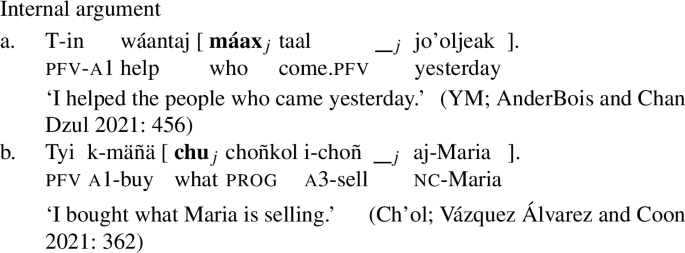

5.1 [–Det, +Wh] headless relative clauses

Free Relatives in both YM and Ch’ol are repeated in (55). We find that FRs, or [–Det, +Wh] HRCs, in both languages pattern alike: they are introduced by a wh-word, which corresponds to a gap in the FR. As previewed above, we take FRs to be CPs in which the wh-word has undergone A′-movement from a clause-internal position, represented below (we do not represent movement in all examples that follow). The FRs themselves are necessarily interpreted as definite in most cases, as in (55a) and (55b) where the FR appears in the internal argument position of a transitive verb.

-

(55)

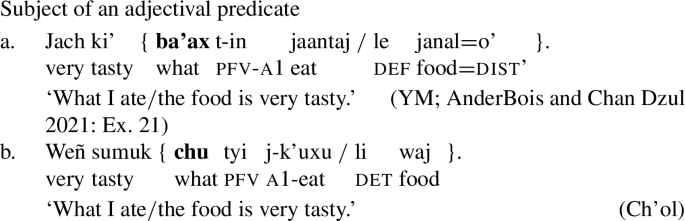

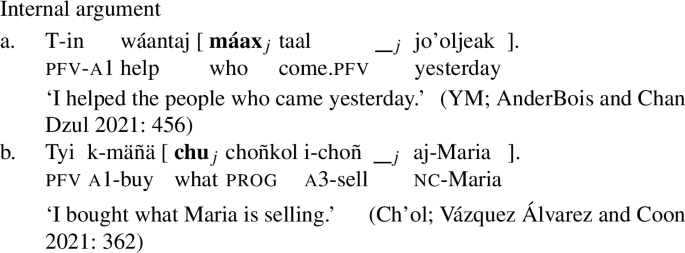

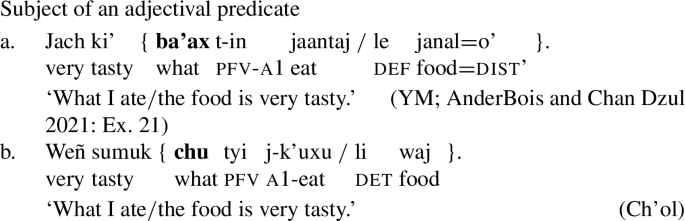

FRs are also possible as subjects of adjectival predicates in (56). We illustrate in (56) that these sentences can be paraphrased by replacing the FR with a definite nominal, a diagnostic discussed in Jacobson (1995) and Caponigro (2003) for definiteness.

-

(56)

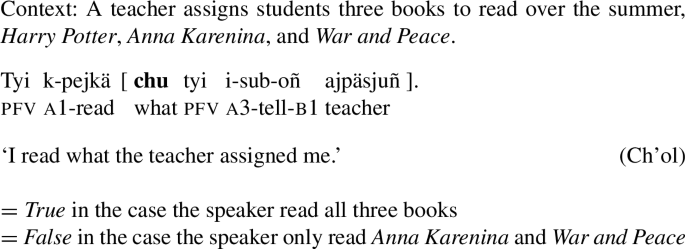

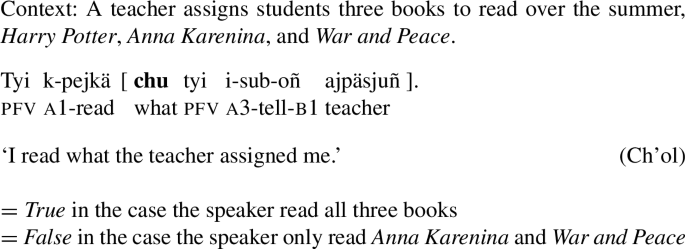

The definiteness and maximal properties of these FRs are further confirmed by the following Ch’ol example in which the Ch’ol sentence corresponding to ‘I read what the teacher assigned’ is true only in the context where the speaker read all three books. It is false is in a context where the speaker only read two books.

-

(57)

When appearing in external argument position, must also be interpreted as definite and maximal, as shown in (58).

-

(58)

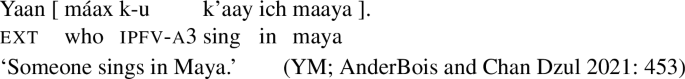

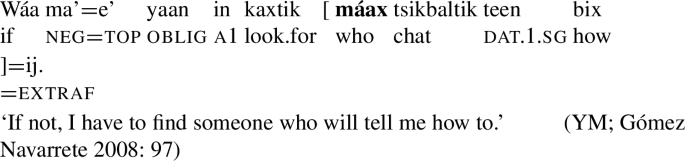

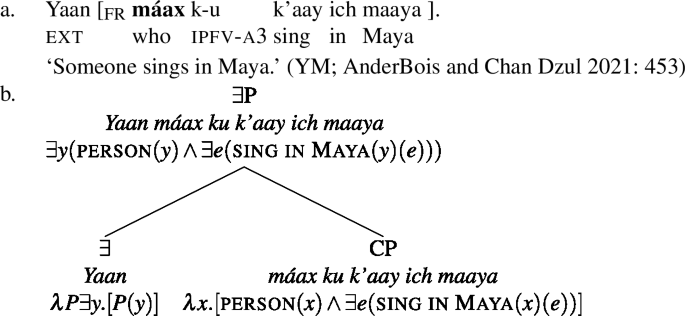

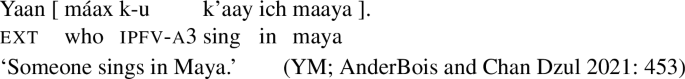

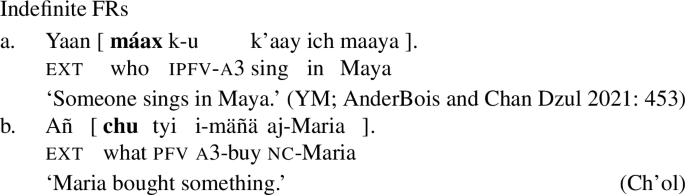

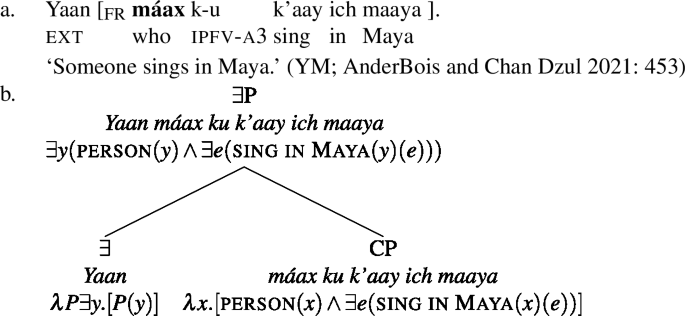

FRs can only be interpreted as indefinite when combining existential predicates, and with certain verbs that denote coming-into-being, view, or existence. Examples with the existential predicate añ in Ch’ol and yaan in YM are given below. These are often translated into English as ‘someone’ or ‘something’ (note these languages lack distinct indefinite pronouns). The FR in YM in (60) is interpreted as indefinite due to the verb ‘look for.’

-

(59)

-

(60)

Additional examples from YM and Ch’ol can be found in AnderBois and Chan Dzul (2021) and Vázquez Álvarez and Coon (2021), respectively. Note that in YM and Ch’ol there is no requirement that existential FRs have some modal, irrealis or circumstantial flavor. Existential FRs in many Indo-Euroean languages have been reported to require certain moods in existential FRs (Šimík 2011), but this is not the case for YM or Ch’ol. As was mentioned in Caponigro (2021), this poses a challenge to Šimík’s (2011) empirical generalization that existential FRs can only occur in infinitival form or some other non-indicative mood.

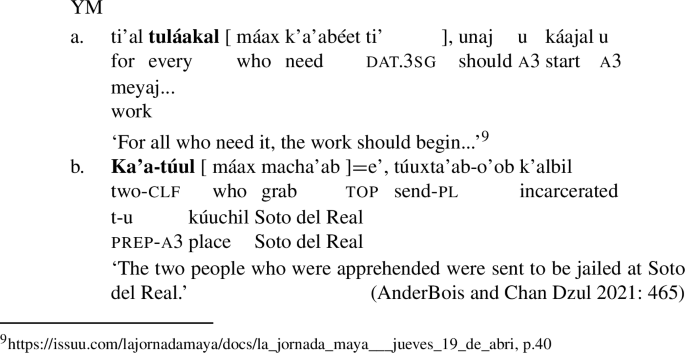

5.2 [+Det, +Wh] headless relative clauses

A key property of FRs in YM and Ch’ol, is that, unlike in English, they may appear with determiners, as illustrated in (61a) and (61b); an ungrammatical English example is shown in (61c). [+Det, +Wh] HRCs are shown in transitive object position below, but may also appear as transitive and intransitive subjects.

-

(61)

We discuss the semantic contribution of the definite determiner further in Sect. 6, but first focus on the implications of this for our understanding of FRs. Similar to what we observed in Sect. 3.3 for [–Wh] HRCs, a full range of determiners is possible with [+Wh] HRCs. Again, this provides evidence that these [+Det] HRCs are not a special type of light-headed relative clause construction as proposed by Citko (2004) for Polish. The Mayan facts provide evidence that there is parametric variation regarding whether HRCs in a given language can appear with determiners.

-

(62)

-

(63)

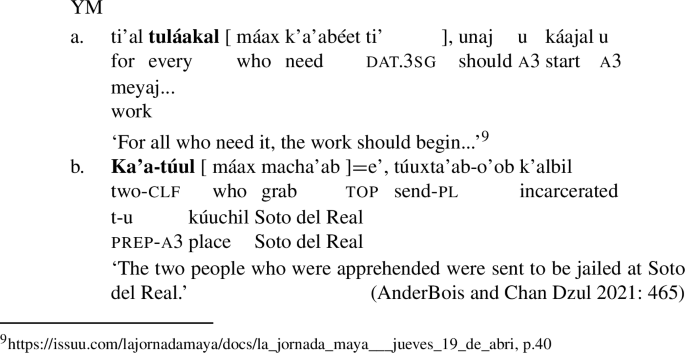

Unless they are in theme position of an existential predicate or of a coming-into-being/view/existence predicate, FRs are interpreted as definite and maximal. No differences in FR distribution or interpretation were found between the two languages, a fact which we tie into our analysis of a type-shifter for FRs: FR-ι. FRs in YM and Ch’ol pattern with FRs in English and other languages in terms of their interpretation. This generalization has been supported by other languages of Mesoamerica, summarized in Caponigro (2022). Unlike in English, however, FRs in both Mayan languages may co-occur with determiners, which we take to be a point of parametric variation across languages. In the next section we provide an analysis for (i) the definiteness of these FRs and (ii) why the indefinite interpretation is restricted to certain positions.Footnote 9

6 [+Wh] free relatives are CPs

In the previous section, we observed that unlike SFRCs—whose interpretation closely parallels that of bare nouns in the respective language—FRs pattern similarly to one another across the two languages. In this section, we argue for an account of FRs that makes use of a definite type-shifter, FR-ι, which follows a very different set of principles than N-ι. The presence of N-ι is closely tied to nominal expressions and is sensitive to the existence of other determiners, and therefore its availability varies across languages. We propose that FR-ι, on the other hand, is specific to FRs, which are syntactically CPs, and is available regardless of the existence of competing determiners in the language. Section 6.1 provides an analysis for the syntactic and semantic properties of FRs, Sect. 6.2 discusses the FR-ι type-shifter, and Sect. 6.3 summarizes and rejects an alternative account.

6.1 The syntax and semantics of [+Wh] headless relative clauses

As previewed above, we take FRs to be CPs, which involve A′-movement of a wh-word from a clause-internal position, repeated for a Ch’ol FR in (64).

-

(64)

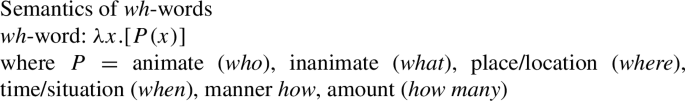

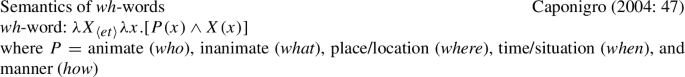

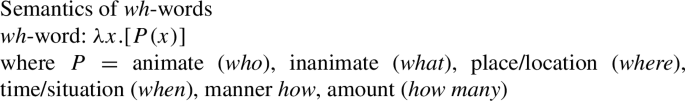

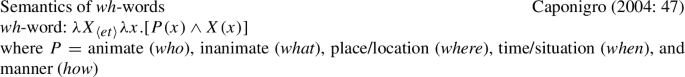

We adopt the proposal of Caponigro (2003, 2004) and more recently that of Caponigro (2022), based on Mesoamerican languages, that the relative clause itself in FRs denotes a set, and that wh-words introduce a sortal domain. A′-movement of the wh-word triggers lambda abstraction that makes this denote a set, derived in the tree below in (66b). The wh-words corresponding to ‘who’ and ‘what’ have as their the sortal domain animate/human or inanimate as in (65).Footnote 10

-

(65)

Putting these assumptions together, we exemplify the approach with the FR in Ch’ol in (66a) ‘what Maria bought.’ The derivation is given in (66b).

-

(66)

In (66b), the wh-word moves from its position as an internal argument of the verb to Spec,CP and the verb mäñä ‘buy’ combines with the trace of type e. We introduce lambda abstraction over the moved wh-word at C then the wh-word and the predicate combine via predicate modification to return the set of individuals which are inanimate and such that Maria bought them, rendering a predicate of type 〈et〉. Next, we discuss how this structure interacts with FR-ι.

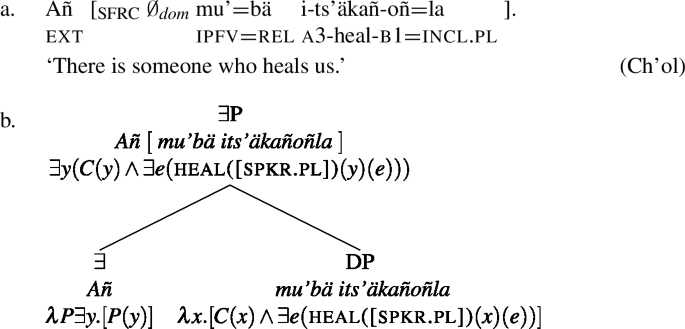

6.2 FR-ι: A type-shifter for free relatives

Recall that a central motivation for this research is to investigate the range and applicability of type-shifting cross-linguistically. It has been proposed that languages that allow bare nouns to be definite have an ι type-shifter available; this same type-shifter is not available in languages that must mark definite nominals overtly with an article (e.g., Chierchia 1998; Dayal 2004; Jenks 2018; Despić 2019; Moroney 2021; i.a.). At the same time, literature on FRs has proposed a type of ι type-shifter available even in languages that obligatorily mark definiteness overtly (Jacobson 1995; Caponigro 2003, 2004).

What is unclear from these previous discussions is whether different type-shifting principles apply to FRs because FRs in English (and many other languages) cannot be combined with determiners, or due to an intrinsic difference between the type-shifting processes in FRs and other nominals. Ch’ol and YM provide a clear answer to this question. Since FRs combine freely with determiners in both languages, if the same type-shifting mechanism were at play, we would expect that FRs in Ch’ol and YM would pattern quite different from one another, just as we saw for SFRCs. However, FRs pattern similarly in both languages, and crucially are different from SFRCs and bare nouns.

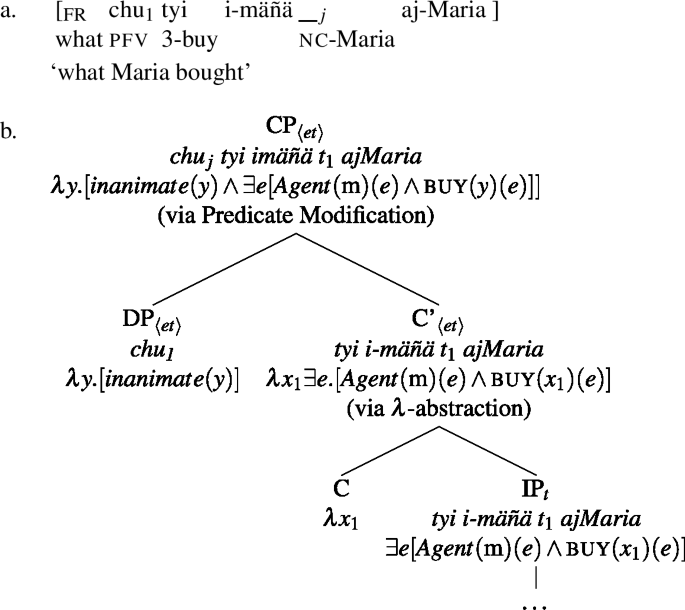

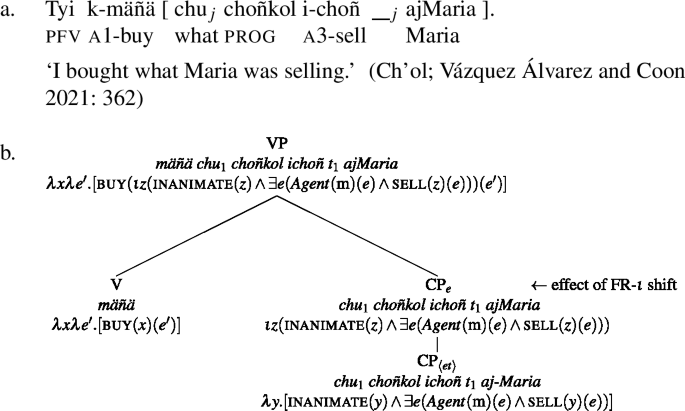

We therefore propose that there is a Free Relative ι (FR-ι) available to languages regardless of the presence or absence of obligatory definite articles. Following (Caponigro 2003, 2004), we propose that FR-ι is a post-syntactic mechanism used to resolve a type-mismatch for CPs appearing in argument position. The derivation for an internal argument FR is given in (67b). FR-ι type-shifts CPs as a last-resort operation, making it quite different from N-ι, which we proposed above to be a D0 head, available as a lexical item in some languages but not others. This is contrary to Caponigro’s suggestions that type-shifters for bare nouns and those for FRs are parallel.

-

(67)

We take FR-ι to be a type-shifter to resolve a type-mismatch in the semantics à la Partee (1987). This is what has been discussed before in Jacobson (1995) and Caponigro (2003, 2004, 2022) for FRs. As per the tree in (67b), it shifts the CP\(_{\langle et \rangle }\) to an individual, without changing the syntax. This is different than N-ι in Ch’ol, which is merged in a D head and subject to cross-linguistic variation. Thus, while a type-shifter like N-ι may be subject to cross-linguistic variation and competition in terms of whether it is in a language’s lexicon, FR-ι is not. FR-ι is part of the semantic architecture and available regardless of the inventory of determiners in a language.

Indefinite interpretations for FRs are blocked in two different ways for each language. For YM, where indefiniteness via Restrict and type-shifting is ruled out on other grounds, there is no other operation that can type-shift the FR in order for it to receive an indefinite interpretation. Indefinite interpretations are only available with existential predicates, as discussed below.

For Ch’ol, we propose that indefinite interpretations are ruled out for FRs because Restrict is limited to combine things that are nominal. FRs are CPs, thus internal FR arguments cannot combine with the verb via Restrict, and consequently existential closure cannot apply. This restriction is not explicit in Chung and Ladusaw’s (2004) original proposal, but is arguably implicit since Restrict is indeed used in the Austronesian languages Chamorro and Maori for noun-incorporation structures and indefinites, respectively. Thus, a definite interpretation is the only one available for FRs in Ch’ol.

As FR-ι is a last-resort mechanism used to repair a type clash, certain predicates may override the need to use FR-ι. One example is with the existential predicate, in which case the semantics of the predicate existentially closes the unsaturated argument of the FR, deriving an indefinite interpretation. These FRs are usually translated into English with indefinite pronouns. An example from YM is given below, with the derivation in (68b). We assume that FRs with indefinite interpretations appearing in internal argument position of coming-into-being/view/existence predicates behave similarly.

-

(68)

Note that in (68b), FR-ι is not present in the structure. The NP combines with the existential predicate via Function Application. Combining via FR-ι would cause a conflict with the existential meaning and be ungrammatical for the same reasons as a [+Wh] HRC with an overt definite article.

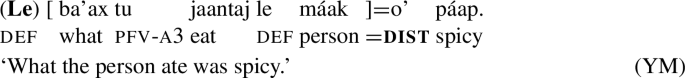

One final question raised by the data here is what difference, if any, there is between the [–Det, +Wh] FRs described in Sect. 5.1, and the FRs which co-oocur with a determiner, [+Det, +Wh] HRCs, seen in Sect. 5.2. Consider, for example, the bracketed HRC in (69), which may appear with or without a determiner.

-

(69)

Semantically, the inclusion of the definite article may be motivated by the fact that overt definite articles in both languages have not only uniqueness uses, but also anaphoric/familiar uses (see Vázquez-Rojas Maldonado et al. 2018 for YM, Little and Vázquez Martínez 2018 and Little 2020 for Ch’ol). While the maximality/uniqueness contributed by FR-ι is not necessarily incompatible with anaphoricity, it seems that the overt article more readily allows it.

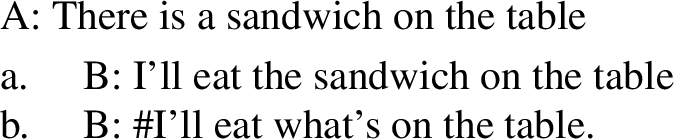

Indeed, we may make a similar observation about English FRs compared to corresponding definite descriptions. There is an intuition that there is some aversion to the obvious anaphoric interpretation in (70b). While (70b) is not strictly infelicitous on the relevant interpretation, it seems that the use of the overt definite article the more readily facilitates the anaphoric interpretation.

-

(70)

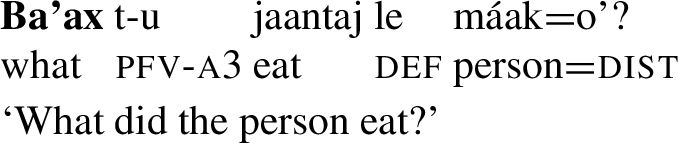

In addition to semantic reasons, for YM at least, the use of the overt definite avoids temporary ambiguities. For example, the FR in (69) (the version with no definite article) is largely identical to the corresponding interrogative in (71).

-

(71)

The use of the overt definite version of (69), therefore, avoids the possibility of garden-pathing.

Finally we note that the availability of [+Det,+Wh] HRCs provides evidence against an analysis where they are in fact headed relative clauses with a nominal head, as proposed for YM in Gutiérrez Bravo (2013, 2015). Recall that wh-words cannot introduce headed relative clauses in either language in argument position, making it hard to maintain an analysis that [+Det,+Wh] HRC could be analyzed as headed relative clauses with a null head.

6.3 Summary and rejecting a semantic alternative

In this section we motivated a cross-linguistic FR-ι used to type-shift [–Det, +Wh] HRCs, or FRs. Such a type-shifter has been proposed for English as well as other languages (Caponigro 2003, 2004), but this literature has largely not discussed the applicability of the type-shifter with respect to nouns. We proposed that FR-ι is a type-shifter available to FRs, regardless of whether a language has an obligatory definite article. The differences between SFRCs and FRs in our view are largely due to syntactic differences between the two. Whereas N-ι is a type-shifter that occurs with nominal expressions, FR-ι is limited to occur with CPs as a post-syntactic mechanism to repair a type clash.

To more semantically-minded researchers, this syntactic approach might seem like a missed opportunity. One might have hoped that the differences between SFRCs and FRs would instead be explained by differences between the semantics of wh-words and that of nouns rather than their syntactic differences. FRs make use of wh-words and therefore may plausibly have a more question-like semantics not shared with nouns.Footnote 11

For example, Xiang (2020) proposes a “hybrid categorial” semantics in which question abstracts are functions from short answers to propositional answers. She then defines an operator, \(\mathcal{A}\), that applies to the question meaning in FRs to return the complete true short answer to the question (Sect. 6.1.1). Since \(\mathcal{A}\) takes question meanings as inputs, while N-ι takes common noun meanings, this semantic difference might appear to explain the different behavior of FRs and SFRCs.

While Xiang’s \(\mathcal{A}\) is potentially suitable for English, where FRs only have definite interpretations, it doesn’t work for Ch’ol and YM for two reasons. First, as we have seen, FRs can systematically receive indefinite interpretations with existential predicates regardless of the FR’s particular content.Footnote 12 Second, and perhaps more troublingly, we have seen that FRs in Ch’ol and YM combine with the full range of determiners available to ordinary nouns in each language. What a semantic alternative would require, therefore, is that FRs have a meaning that are at once different enough from those of nouns to require different type-shifters, yet similar enough to be able to combine freely with the full range of overt quantifiers, numerals, determiners, and demonstratives. Despite its initial appeal, we therefore conclude that a semantic alternative is not viable. In contrast, on our account, we have taken FRs and SFRCs to internally have very similar meanings (thus explaining their ability to compose with various determiners), but to differ in their syntactic category (thus triggering different type-shifting principles).

7 Conclusions

We began this paper with a puzzle on type-shifting and HRCs. On the one hand, a range of previous literature has employed a type-shifting analysis for bare nouns in languages that allow bare nouns to be definite; these same principles are not employed in languages with obligatory articles. The literature on FRs, on the other hand, has adopted a type-shifting analysis, regardless of whether there is an obligatory definite article.

While previous literature has suggested that these two cases are different instantiations of a single type-shifting mechanism, in this paper, we have argued that there are two distinct type-shifting mechanisms—N-ι and FR-ι. The former is a nominal type-shifter available for bare nouns and SFRCs. Crucially, N-ι is sensitive to the presence or absence of an obligatory definite article within a given language. This was illustrated by the availability of N-ι in Ch’ol (no obligatory definite article), but not in YM (obligatory definite article). Conversely, FR-ι is particular to FR CPs and inserted post-syntactically to resolve a type-mismatch regardless of the presence or absence of definite articles. We have seen this illustrated by the availability of FR-ι in both Ch’ol and YM, despite the difference in their determiner systems. The independence of FR-ι from N-ι is made all the more clear by the fact that both languages allow for both SFRCs and FRs to combine with all the same determiners found in other nominals.

By making this distinction between N-ι and FR-ι we are thus able to make a finer-grained distinction in the type-shifting principles available across languages. N-ι is subject to language-specific properties. On the other hand FR-ι is a type-shifter in the strict sense, present in the semantic architecture to resolve a type-mismatch and not subject to cross-linguistic variation. This paper thus provides an empirical basis for the claims in Partee (1987) who writes:

I do not want to suggest that there is a single uniform and universal set of type-shifting principles. There are some very general principles which are derivable directly from the type theory, others which are quite general but which depend on the algebraic structure of particular domains...and still others which seem to be language-particular rules. (Partee 1987: 361)

By investigating the case of HRCs in Ch’ol and YM we have evidence for a “quite general” type-shifter (FR-ι) and another type-shifter abiding by “language-particular rules” (N-ι).

To conclude, we offer three avenues for future work. First, if a language has SFRCs, do they pattern as bare nouns elsewhere? Our analysis, as well as a preliminary look into other Mesoamerican languages, would predict they do. This future line of investigation involves both a look into the interpretation and distribution of bare nouns as well as SFRCs. Similarly, if SFRCs do pattern like bare nouns, we also expect the same range of determiners that occur with nouns to appear with SFRCs. If these pattern as expected, then this is further support for the range and applicability of nominal type-shifters for [–Wh] HRCs.

Second, we expect that regardless of how definiteness is expressed in a language, FR-ι is available for FRs in languages which possess these constructions. This has largely been supported by previous work, including a cross-linguistic survey of under-studied Mesoamerican languages (Caponigro et al. 2021) and a summary in Caponigro (2022). Given our findings, however, we do not necessarily expect FRs to pattern parallel to SFRCs. Further investigation into languages with SFRCs will bear on this.

Lastly, it is of note that much work on HRCs has concentrated on English and other Indo-European languages. We would like to highlight that the empirical findings here suggest that generalizations from Indo-European HRCs are not as representative as the literature may lead a reader to believe. For instance, the existence of SFRCs, existential FRs without any modal or irrealis flavor, and [+Det] HRCs are not found in English, but are possible—and common—in Mayan. Beyond their existence, we hope to have shown that the properties of these various HRCs pose challenges to prior theories of HRCs and the kinds of type-shifting operations they rely on.

Notes

Glosses follow Leipzig Glossing Conventions with the following additions: A – “Set A” (ergative; possessive); af – agent focus; ana – anaphoric clitic; B – “Set B” (absolutive); dim – diminutive; dir – directional; ext – existential; extraf – extrafocal; icp – incompletive; nc – noun class prefix; oblig – obligative; rep – reportative. Language data in this paper comes from textual sources, cited throughout, or from elicitation with Ch’ol and YM speakers conducted by the authors following contextualized elicitation tasks (see e.g. Matthewson 2004). Data cited from Spanish-language sources have been translated to English by the authors, and in some cases glosses from other works have been simplified or modified for consistency.

For reasons of both space and scope, we do not discuss adjunct HRCs or free choice relative clauses in either language. While adjunct HRCs are attested in both languages they are not completely parallel and more work needs to be conducted in order to determine their semantics. For free choice relatives such as ‘whatever he bought,’ there are some confounding factors that need further investigation before they can be discussed in detail. The reader is referred to AnderBois and Chan Dzul (2021) and Vázquez Álvarez and Coon (2021) for more on these constructions in YM and Ch’ol and Caponigro and Fălăuş (2018) and Šimík (2021) for cross-linguistic variation in free choice relatives.

The only case where there is a difference between bare nouns and SFRCs is the irrealis usage. Some bare nouns are possible as in the example in (ia). A SFRC is not grammatical in the same position as exhibited in (ib). We speculate that this may be for processing reasons (i.e. without a head or an overt relativizer in YM, unlike Ch’ol, detecting the presence of the relative clause is difficult), but leave such cases to future work to investigate.

-

(i)

-

(i)

A slightly more complicated alternative formulation would be to take the domain to be the set of individuals x such that x is a part of a contextually salient plural individual. This more complex alternative appears equivalent for present purposes, but perhaps clarifies somewhat the contrast with the competing account based on nominal ellipsis, where it is the property itself that is relevant, rather than the specific individuals instantiating it.

See also discussion about this construction and an analysis based on PF deletion in Ticio (2010).

Note that Ch’ol unergative verbs are formally transitive (Coon 2012) and make use of a transitive light verb cha’le and a nominal complement. Unergative subjects pattern with transitive subjects in the forms described here.

Caponigro (2022) notes that Gitksan (Tsimshianic), as described in Aonuki (2022), may be a counterexample to the generalization that [–Det,+Wh] HRCs are definite: Aonuki (2022) describes [–Det,+Wh] HRCs as being interpreted consistently as indefinite in any argument position. However, to quote from Caponigro (2022: 40): “it has emerged from a follow-up conversation with Yurika Aonuki, that the wh-words that introduce FRs in Gitksan can also be used on their own, without introducing an FR. In this absolute use, they are always interpreted as indefinites (e.g., the wh-word for ‘who’ means ‘someone’ when used on its own). Therefore, “indefinite” FRs could just be headed (or light-headed) relative clauses with an indefinite wh-word as their head. Further investigation is needed to determine which hypothesis is correct.” We thank a reviewer for pointing this out to us.

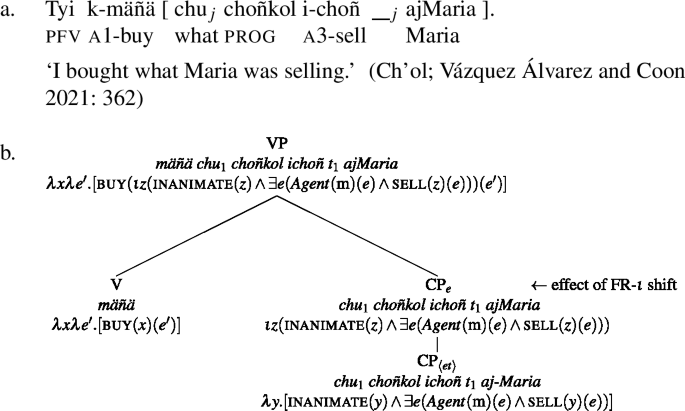

In Caponigro (2003, 2004), the wh-word takes an additional argument of type 〈et〉, given below:

-

(i)

“[P]hrasal wh-words are assumed to act as set restrictors: they apply to a set and return a subset” (Caponigro 2004: 47).

Here we focus on FRs headed by wh-words corresponding to ‘who’ and ‘what,’ but note that in Ch’ol bajche’ ‘how,’ jay-clf ‘how many,’ ba’ ‘where,’ chukoch ‘why,’ jalaj ‘when’ and ba’bä ‘which’ are possible in FRs (see Vázquez Álvarez and Coon 2021 for more details and examples). In YM, in addition to the examples discussed here, only tu’ux ‘where’ and bix ‘how’ are clearly acceptable in FRs (see AnderBois and Chan Dzul 2021 for details and discussion).

-

(i)

Cross-linguistically, Caponigro (2003) argues that the wh-words found in FRs are a subset of the interrogative wh-words within a language, typically a proper subset. Crucially, this set is not necessarily related to the set of relative pronouns found for headed RCs within the same language (e.g. English what occurs in FRs, but not in headed RCs). See Sect. 2.1.1 of Xiang (2020) for further discussion of this generalization and its implications for the relationship between FR and interrogative semantics.

Xiang (2020) discusses a different sort of “existential” interpretation for English FRs as in (i).

-

(i)

Whatever the status of this example, we note that its interpretation does not rely on a higher existential predicate as in the Ch’ol and YM cases, but on the mention-some semantics/pragmatics that Xiang discusses. Indefinite/existential FRs in Ch’ol and YM (and seemingly in most other languages) are similarly possible regardless of the particular FR’s content and therefore represent a distinct phenomenon than English cases like (i).

-

(i)

References

Aissen, Judith. 1992. Topic and focus in Mayan. Language 68(1): 43–80.

Aissen, Judith. 2017. Information structure in Mayan. In The Mayan languages, eds. Judith Aissen, Nora C. England, and Roberto Zavala, 293–324. London: Routledge.

Aissen, Judith, and Gilles Polian. 2021. Headless relative clauses in Tseltalan. In Headless relative clauses in languages of Mesoamerica, eds. Ivano Caponigro, Harold Torrence, and Roberto Zavala, 403–443. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Aissen, Judith, Nora C. England, and Roberto Zavala, eds. 2017. The Mayan languages, Oxon: Routledge.

AnderBois, Scott. 2018. U chiikulil k’aatchi’: Forma, función, y la estandarización de la puntuación [The question mark: Form, function, and the standardization of punctuation]. Cuadernos de linguistica de El Colegio de Mexico 5(1): 388–426.

AnderBois, Scott, and Miguel Oscar Chan Dzul. 2021. Headless relative clauses in Yucatec Maya. In Headless relative clauses in languages of Mesoamerica, eds. Ivano Caponigro, Harold Torrence, and Roberto Zavala, 444–473. London: Oxford University Press.

AnderBois, Scott, Miguel Oscar Chan Dzul, Jessica Coon, and Juan Jesús Vázquez Álvarez. 2019. Relativas libres en ch’ol y maya yucateco y la tipología de cláusulas relativas sin núcleo. In Proceedings of form and analysis in Mayan linguistics 5, Vol. 5.

Aonuki, Yurika. 2022. Free relatives in Gitksan. In Proceedings of the 11th semantics of under-represented languages in the Americas, eds. Seung Suk Lee and Yixiao Song, 1–16. Amherst: GLSA.

Bennett, Ryan, Jessica Coon, and Robert Henderson. 2016. Introduction to Mayan linguistics. Language and Linguistics Compass 10: 1–14.

Bricker, Victoria, Po’ot Yah, and Ofelia Dzul de Po’ot. 1998. A dictionary of the Maya language as spoken in Hocaba, Yucatan. Salt Lake City: The University of Utah Press.

Can Canul, César, and Rodrigo Gutiérrez-Bravo. 2016. Maayáaj tsikbalilo’ob kaampech = narraciones mayas de Campeche. Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas.

Caponigro, Ivano. 2003. Free not to ask: On the semantics of free relatives and wh-words cross-linguistically. PhD diss, UCLA.

Caponigro, Ivano. 2004. The semantic contributions of wh-words and type shifts: Evidence from free relatives crosslinguistically. In Semantics and linguistic theory, Vol. 14, 38–55.

Caponigro, Ivano. 2021. Introducing headless relative clauses and the findings from Mesoamerican languages. In Headless relative clauses in Mesoamerican languages, eds. Ivano Caponigro, Harold Torrence, and Roberto Zavala. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Caponigro, Ivano. 2022. Headless relative clauses and the syntax-semantics mapping: Evidence from Mesoamerica. In Proceedings of the 11th semantics of under-represented languages in the Americas, eds. Seung Suk Lee and Yixiao Song, 27–42. Amherst: GLSA.

Caponigro, Ivano, and Anamaria Fălăuş. 2018. Free choice free relative clauses in Italian and Romanian. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 36(2): 323–363.

Caponigro, Ivano, Harold Torrence, and Roberto Zavala Maldonado, eds. 2021. Headless relative clauses in Mesoamerican languages, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carlson, Gregory N. 1977. Reference to kinds in English. PhD diss, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Chamoreau, Claudine. 2021. Headless relative clauses in pesh. In Headless relative clauses in Mesoamerican languages, eds. Ivano Caponigro, Harold Torrence, and Roberto Zavala, 509–546. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 1998. Reference to kinds across language. Natural Language Semantics 6(4): 339–405.

Chung, Sandra, and William A. Ladusaw. 2004. Restriction and saturation, Vol. 42. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Citko, Barbara. 2004. On headed, headless, and light-headed relatives. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 22(1): 95–126.

Coon, Jessica L. 2004. Roots and words in Chol (Mayan): A distributed morphology approach, Ba thesis, Reed College.

Coon, Jessica. 2010. VOS as predicate fronting in Chol. Lingua 120: 354–378.

Coon, Jessica. 2012. Split ergativity and transitivity in Chol. Lingua 122: 241–256.

Coon, Jessica. 2018. Distinguishing adjectives from relative clauses in Chuj (with help from Ch’ol). In Heading in the right direction: Linguistic treats for Lisa Travis, eds. Laura Kalin, Jozina van der Klok, and Ileana Paul, 90–99. Montreal: McGill Working Papers in Linguistics.

Dayal, Veneeta. 2004. Number marking and (in)definiteness in kind terms. Linguistics and Philosophy 27(4): 393–450.

Deal, Amy Rose, and Julia Nee. 2017. Bare nouns, number, and definiteness in Teotitlán del Valle Zapotec. In Proceedings of sinn und bedeutung, eds. Chris Cummins, Nikolas Gisborne, Caroline Heycock, Brian Rabern, Hannah Rohde, and Robert Truswell. Vol. 21, 317–334. Edinburgh.

Despić, Miloje. 2019. On kinds and anaphoricity in languages without definite articles. In Definiteness across languages, eds. Ana Aguilar-Guevara, Julia Pozas Loyo, and Violeta Vázquez-Rojas Maldonado, 261–292. Berlin: Language Science Press.

Diesing, Molly. 1992. Indefinites. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Durbin, Marshall, and Fernando Ojeda. 1978. Basic word-order in Yucatec Maya. In Papers in Mayan linguistics, ed. Nora C. England, 69–77. Columbia: Department of Anthropology, University of Missouri.