Abstract

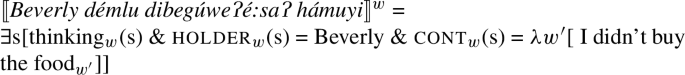

This paper concerns clausal embedding in Washo (also spelled Washoe, Wáˑšiw), a highly endangered Hokan/isolate language spoken around Lake Tahoe in the United States. We argue that Washo offers evidence that both complementation and modification are available strategies for subordination, and in doing so contribute more generally to the ongoing debate about how clauses are embedded by attitude verbs. We observe that the embedding strategies of certain predicates in Washo follow from independent properties of clause types in the language. On the one hand, clauses embedded by presuppositional verbs come in the form of clausal nominalizations, which are selected as thematic internal arguments. The DP layer in these complements is responsible for encoding familiarity in a general sense (along the lines of Kastner 2015) both in these complement clauses as well as in other constructions in the language. On the other hand, clauses embedded by non-presuppositional verbs are not selected at all; they are instead adjunct modifiers, which follows from the fact that the attitude verbs they modify are always intransitive. This aspect of the analysis lends support to the property-analysis of ‘that’-clauses (e.g., Kratzer 2006; Moulton 2009; Elliott 2016), but only in certain instances of embedding. We argue that the Washo facts show that selection still plays a role for some verbs, contra theories that do away with it altogether (Elliott 2016), but selection cannot explain everything either, as non-presuppositional verbs are intransitive and do not select at all.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

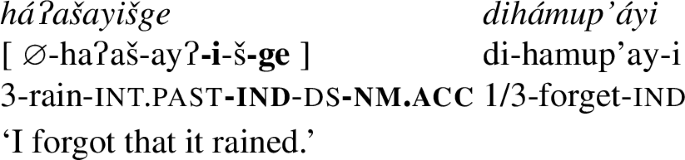

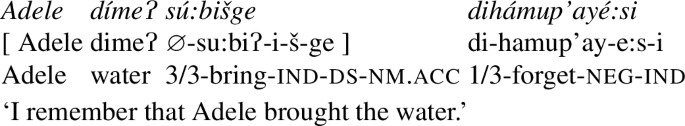

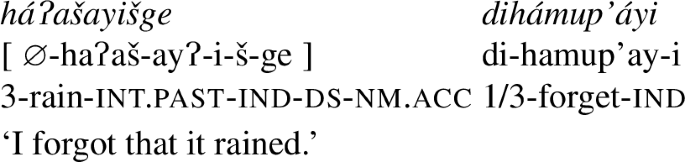

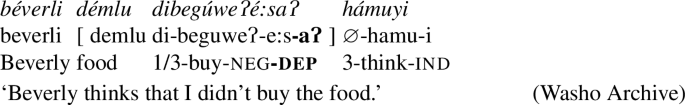

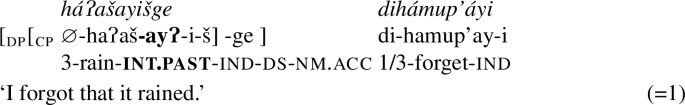

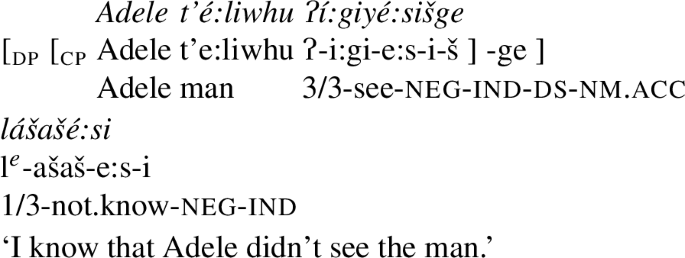

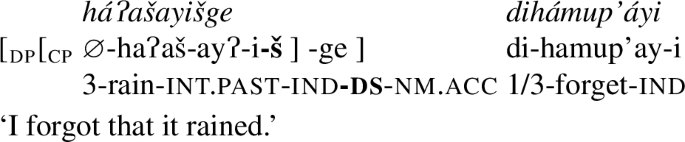

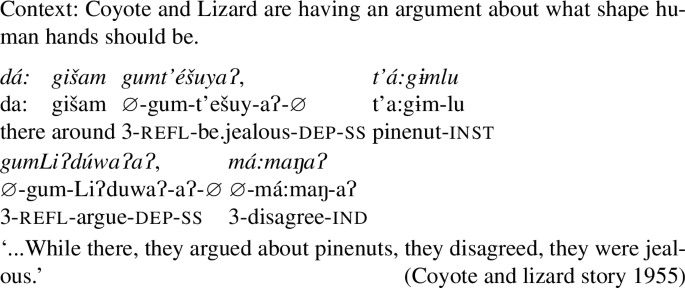

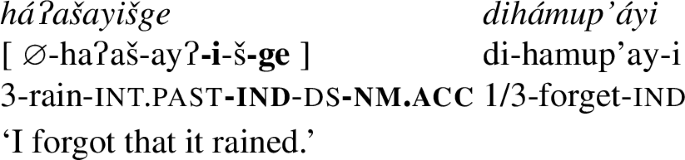

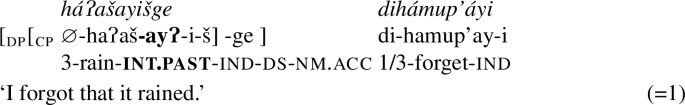

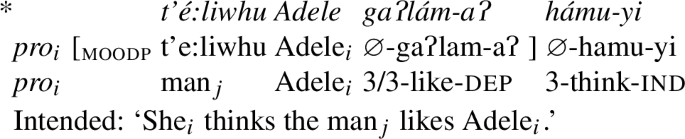

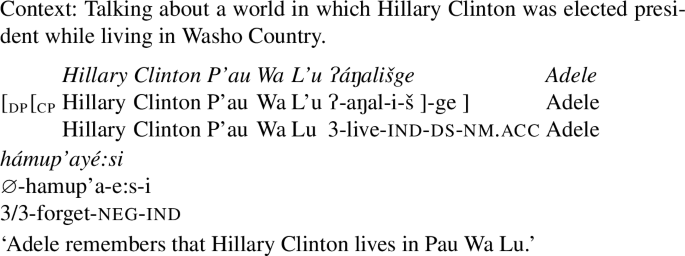

The empirical starting point for this paper is the observation of a morphosyntactic split in modes of clausal embedding in Washo (also spelled Washoe, Wáˑšiw), a highly endangered Hokan/isolate language spoken around Lake Tahoe in the United States. The split is demonstrated in (1)–(2), in which the embedded clauses are indicated by brackets.Footnote 1,Footnote 2 In (1), the clause embedded by the verb hamup’ay ‘forget’ is marked with the independent mood marker -i, as well as the (accusative) nominalizing suffix -ge. In (2), the clause embedded by the verb hamu ‘think’ is marked with the dependent mood marker -aʔ, and is not nominalized.Footnote 3

-

(1)

-

(2)

We show in what follows that this split correlates with, among other things, two classes of verbs that are generally taken to differ on the basis of the presuppositions they impose on the clauses they embed. Often, this distinction is reduced to the notion of factivity: semantically, a factive predicate presupposes the truth of its complement, while a non-factive predicate does not. On the syntactic side of this distinction, it has been demonstrated through a range of studies that presuppositional and non-presuppositional predicates behave differently also with respect to the size and type of clauses they may embed (Kiparsky and Kiparsky 1970; Zubizarreta 1982; Adams 1985; Rooryck 1992; Abrusán 2011, 2014; Kastner 2015; i.a.). The data in (1)–(2) suggest that a morphosyntactic distinction in the embedding properties of these verb classes is also active in Washo, whereby the clauses embedded by presuppositional verbs are nominalized, while those embedded by non-presuppositional verbs are bare.

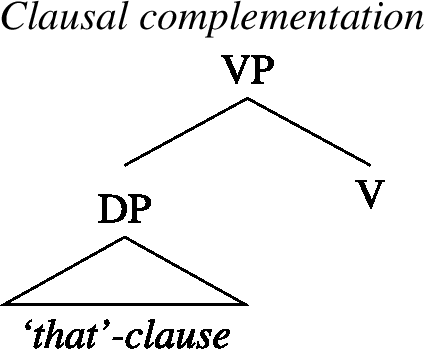

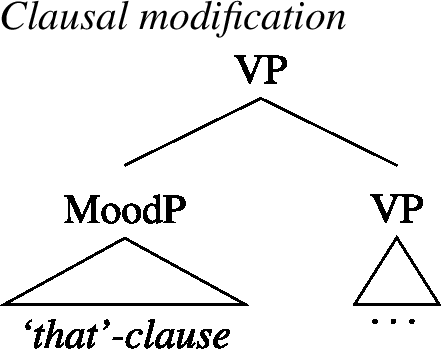

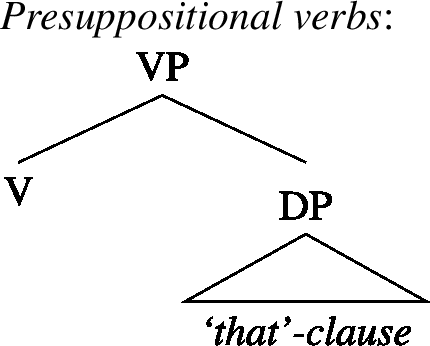

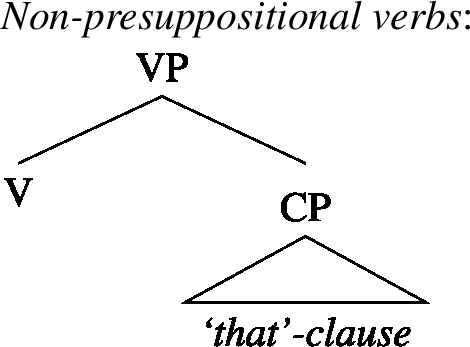

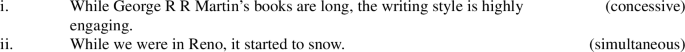

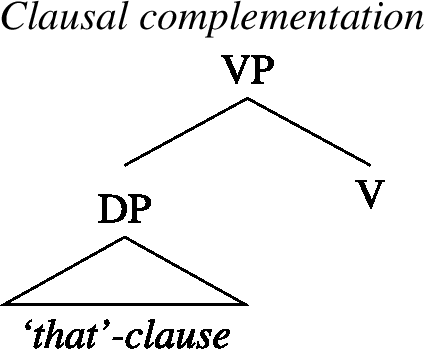

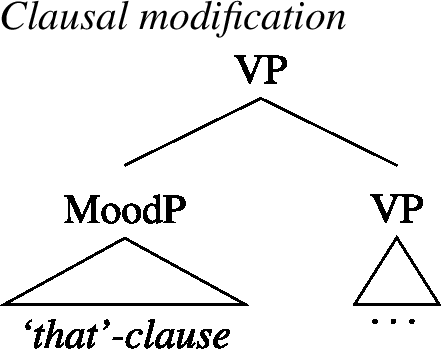

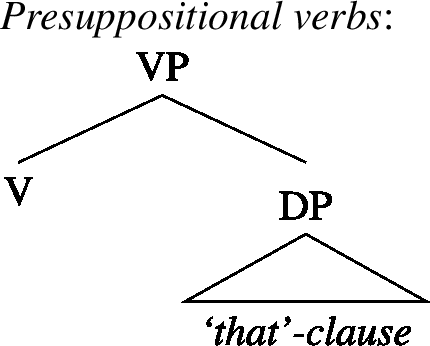

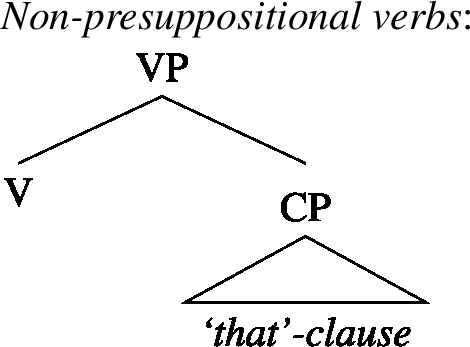

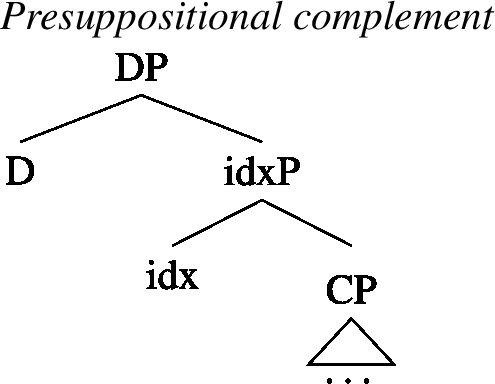

We argue that the shape of these clauses however signals another difference across these modes of embedding, aside from their morphosyntactic shape: while nominalized clauses are selected as complements in the familiar way, bare clauses are instead verbal modifiers. The structural differences between clausal complementation and modification that we propose for Washo are schematized in (3) and (4), respectively.

-

(3)

-

(4)

In our analysis, the DP layer in selected nominalizations as in (3) is responsible for encoding familiarity (Heim 1982) of the embedded propositional content. This idea is generally in line with recent work by, e.g., Kastner (2015), who argues that presuppositional complements are selected by either an overt or covert D head before composing with the matrix predicate itself. Meanwhile, the adjunct status of clauses as in (4) follows in our analysis from the fact that the verbs that embed them are always intransitive, lending support in this respect to the property-analysis of ‘that’-clauses (e.g., Kratzer 2006; Moulton 2009; Elliott 2016, 2017).

We show moreover that the selection/adjunction distinction in (3)–(4) is language-wide in Washo, and is not limited to the aforementioned split across attitude verbs: the nominalization strategy in (3) is also found in internally headed relative clauses and event nominalizations, while the bare clausal embedding strategy in (4) is used in other types of adjunct clauses. The proposed analysis accounts for this, taking into consideration the difference in mood markers found in these clause types as well, by assimilating this distinction to the distribution of mood elsewhere in the language. These mood markers reflect differences in the semantics of the embedded clause, and mirror the patterns observed in further types of embedded clauses as well, supporting the proposed language-wide distinction in complementation vs. modification.

Broadly speaking, the overarching aim of this paper is to rethink the relationship between embedding verbs and the clauses they embed from a more global perspective of a given language, and to elucidate the distinction between complementation and modification as available modes of embedding. On the one hand, the Washo data provide new cross-linguistic support for several recent theories of clausal embedding and the composition of attitude ascriptions. On the other hand, we argue that the Washo pattern reveals that clausal embedding is not as uniform as previously claimed: in Washo, selection does play a role for some verbs, contra theories that do away with it altogether (Elliott 2016), but selection cannot explain everything either (Kastner 2015), as non-presuppositional verbs in Washo are intransitive and do not select at all. The emerging picture is thus one in which both the verb itself and the category of embedded material play a role in deriving presuppositionality effects, in line with proposals for example in Schulz (2003); Özyıldız (2017) and Bondarenko (2020).

The outline of this paper is as follows. In Sect. 2 we elaborate on the two morphosyntactic types of embedded clauses in Washo. In Sect. 3 we propose our syntactic analysis of how these clauses are embedded. In Sect. 4 we introduce the ingredients of our semantic analysis, briefly summarizing previous work on attitude verbs and clausal embedding. In Sect. 5 we present our analysis and draw a broader connection to other types of embedded clauses in Washo, and Sect. 6 concludes.

2 Two strategies for clausal complementation

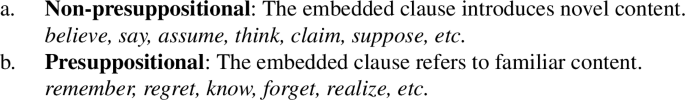

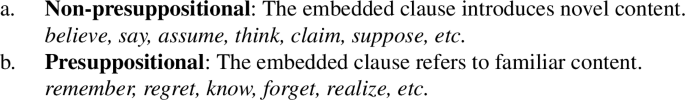

In this section we lay out the two distinct strategies that Washo employs for clausal embedding by verbs of the presuppositional and non-presuppositional type. In the examples to follow, we adopt the following (descriptive) distinction of verb types, based in part on Cattell (1978:77), as well as on Kastner (2015:159) and Bogal-Allbritten and Moulton (2017:215):Footnote 4

-

(5)

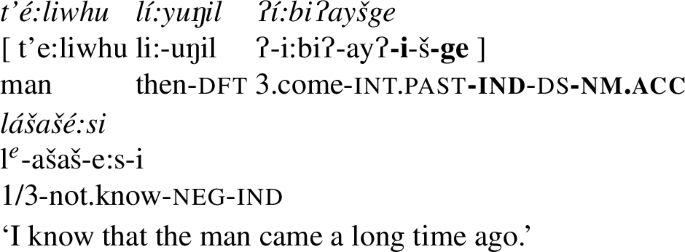

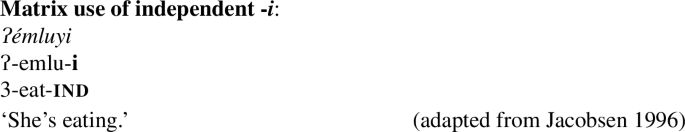

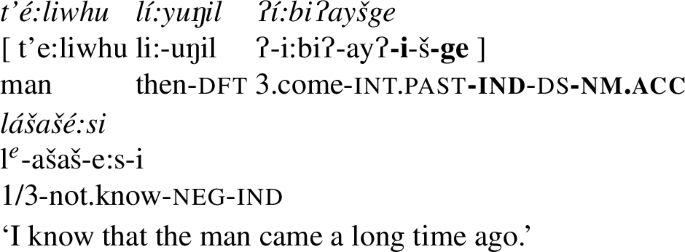

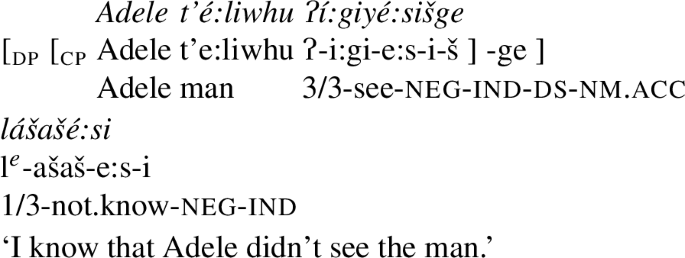

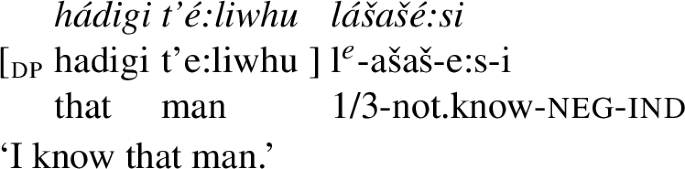

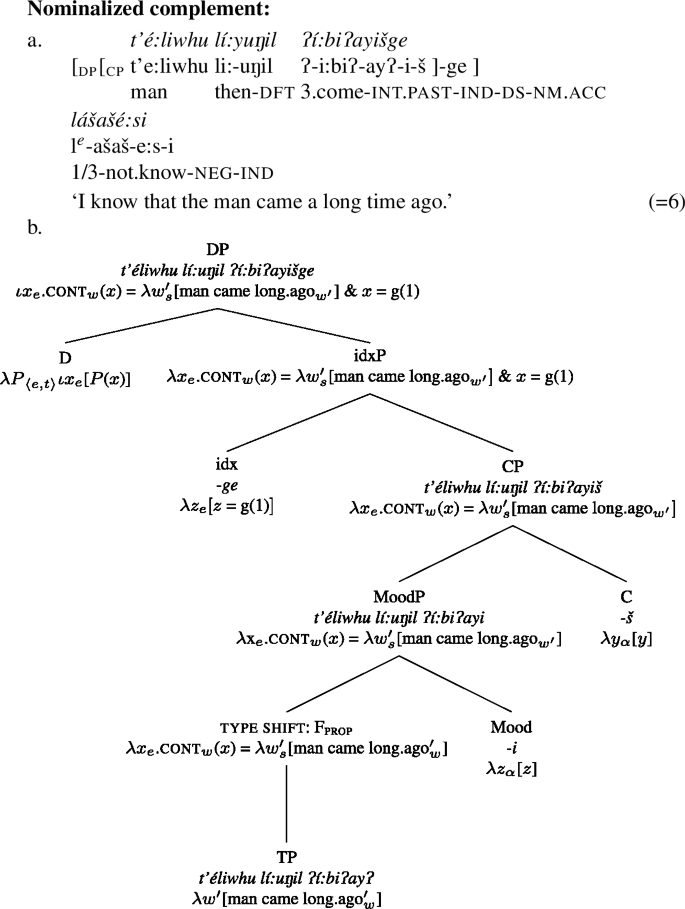

Clauses embedded by presuppositional verbs exhibit two characterizing traits, both of which are exemplified below in (6) under the embedding verb ášašé:s ‘know.’ First, they are always nominalized and bear the suffix -gi/-ge.Footnote 5 Second, they occur with the ‘independent’ mood suffix -i, which is the default mood in Washo; for example, this is the obligatory mood marker in matrix clauses, as shown in (7). To avoid confusion in the examples that follow, we also note here that the verbs ‘know’ and ‘remember’ in Washo are part of a small class of verbs that are inherently negative, i.e., the positive interpretation of this verb requires morphological negation by the suffix -e:s, and in fact ‘remember’ is simply the negated version of ‘forget.’Footnote 6

-

(6)

-

(7)

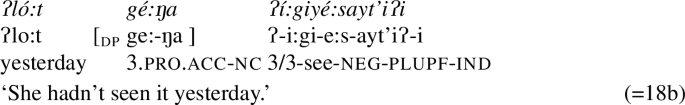

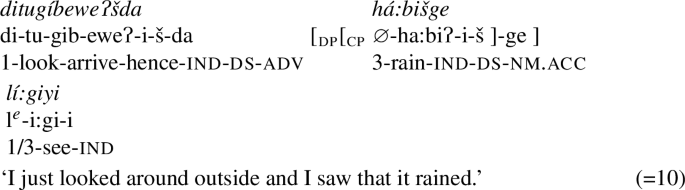

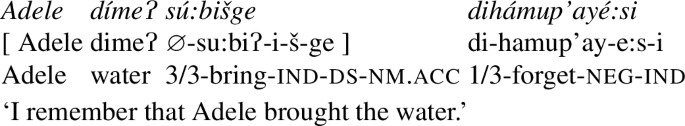

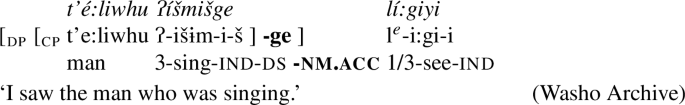

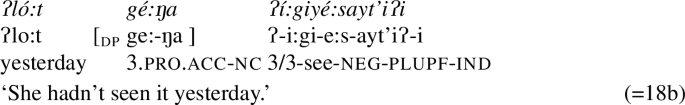

Other examples of nominalizations exhibiting these traits follow in (8–10), embedded by the verbs ‘remember,’ ‘forget,’ and ‘see,’ respectively.

-

(8)

-

(9)

-

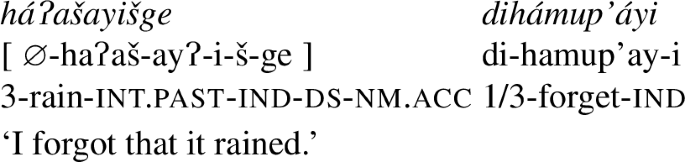

(10)

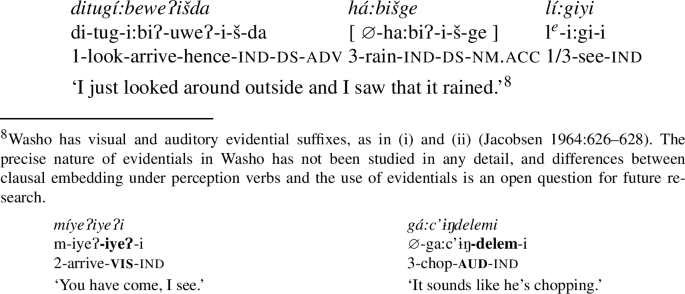

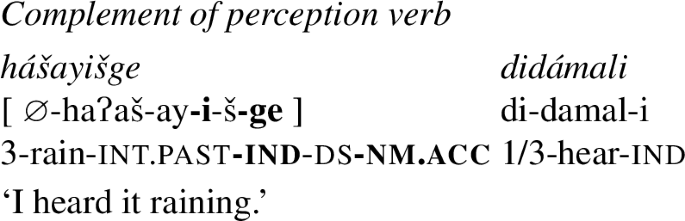

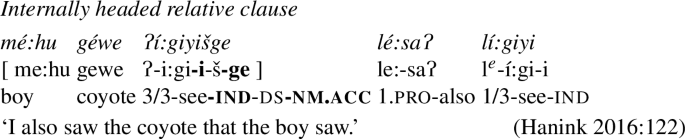

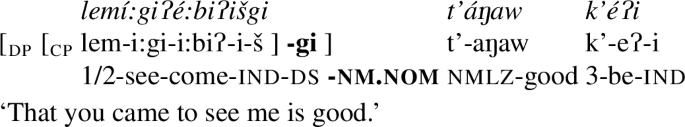

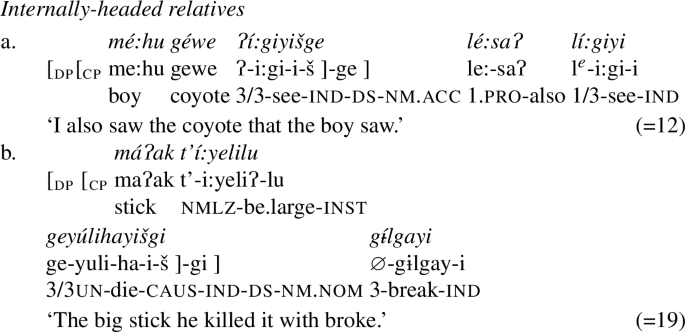

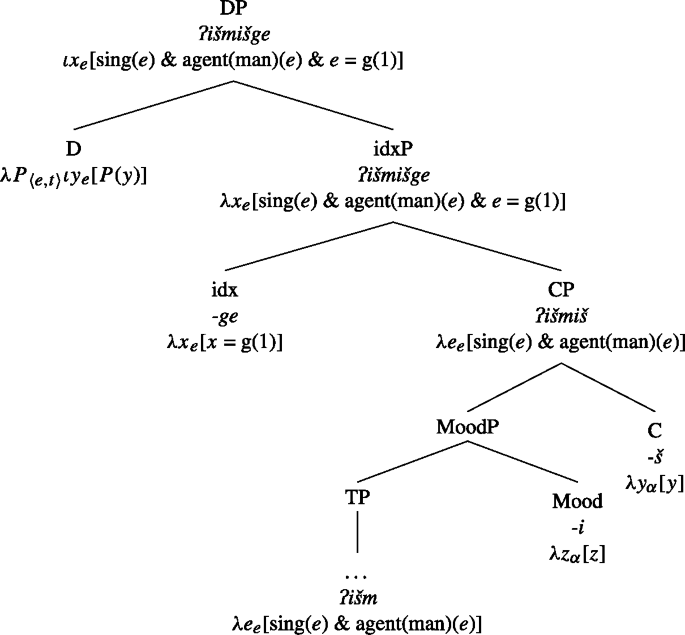

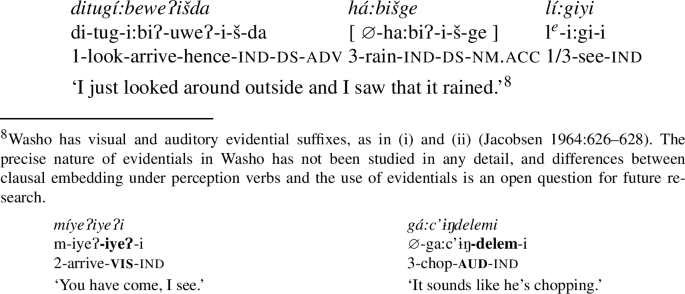

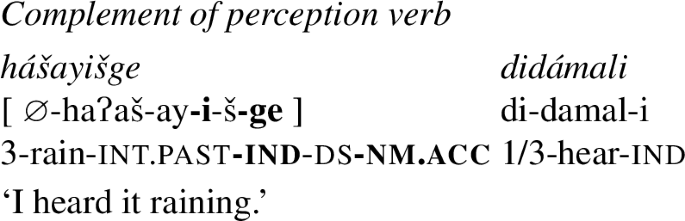

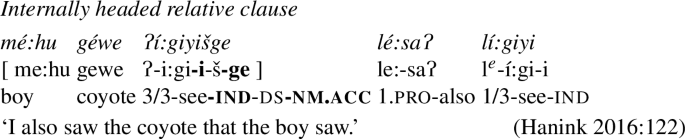

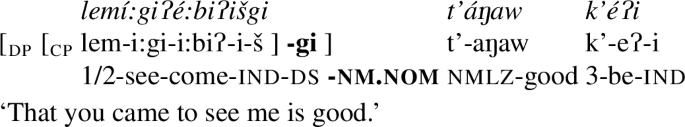

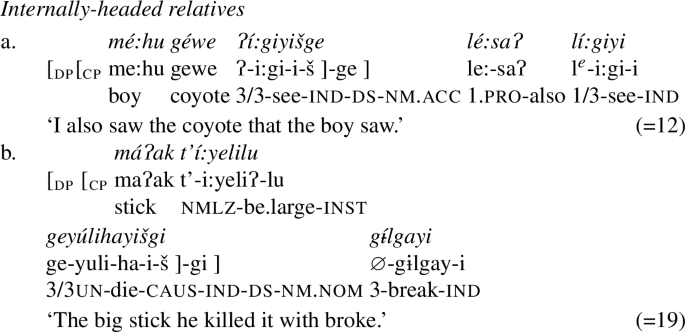

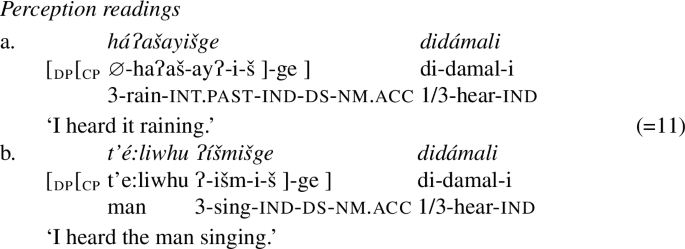

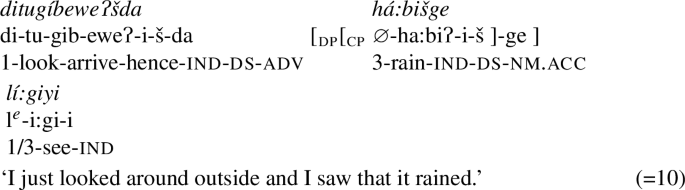

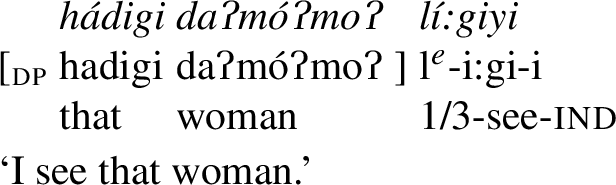

As will become important later in the paper, clausal nominalization is a robust strategy for subordination throughout the language. For example, the complements of perception verbs likewise come in the form of clausal nominalizations (11) (Hanink 2016), as do internally headed relatives (12) (Jacobsen 1998; Peachey 2006; Hanink 2021). We return to the significance of nominalization in the complements of presuppositional verbs and beyond in Sect. 5.2.

-

(11)

-

(12)

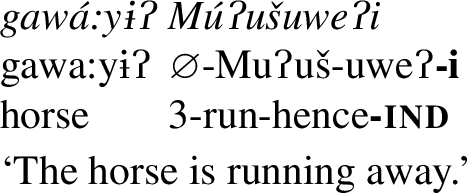

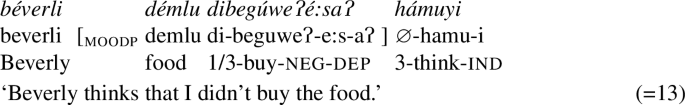

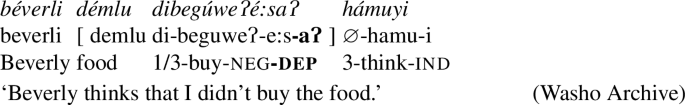

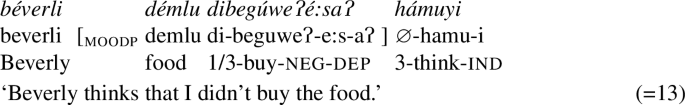

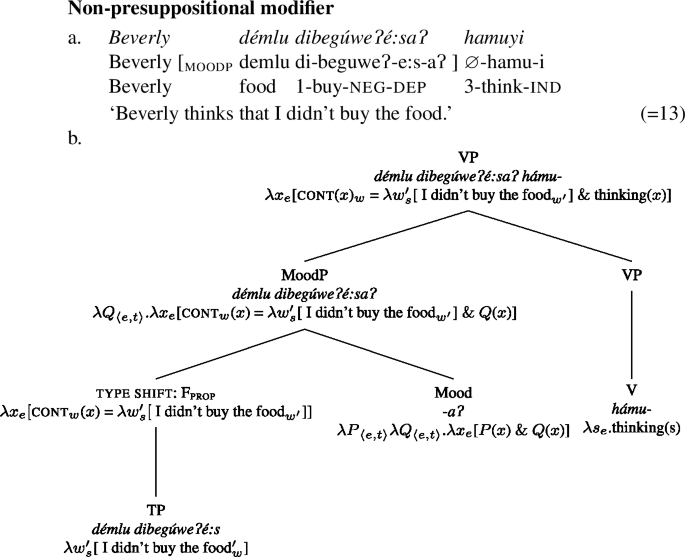

Changing gears, clauses embedded by non-presuppositional verbs differ from those embedded by presuppositional verbs in two ways. First, they surface with the ‘dependent’ mood marker -aʔ, rather than with the independent mood marker -i as above. (We return to arguments for the classification of these suffixes as mood markers in Sect. 5.) Second, they are never nominalized; as noted by Jacobsen (1964:663), this mood marker never co-occurs with nominalizing morphology. Both of these traits can be seen in the embedded clause in (13), which in this case is subordinate to the non-presuppositional verb hámu ‘think’:

-

(13)

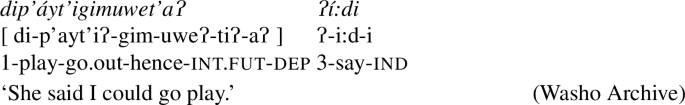

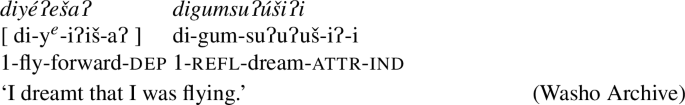

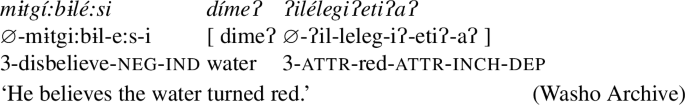

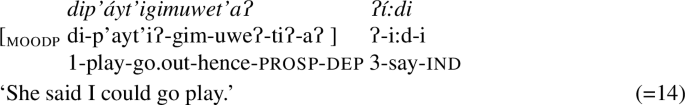

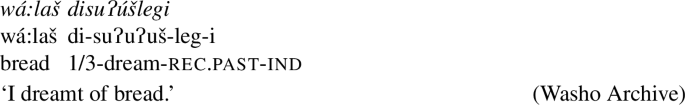

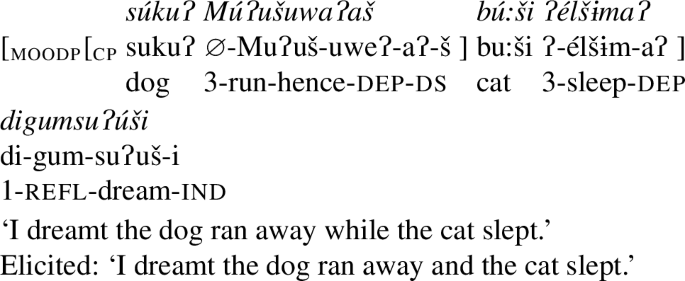

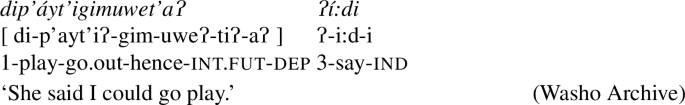

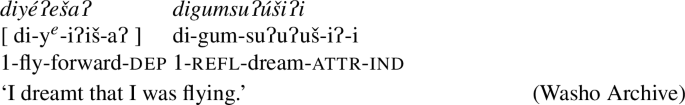

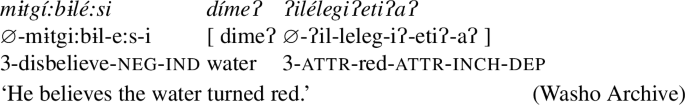

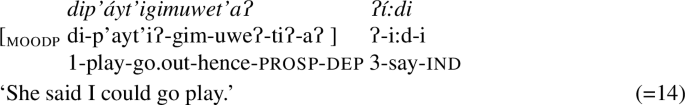

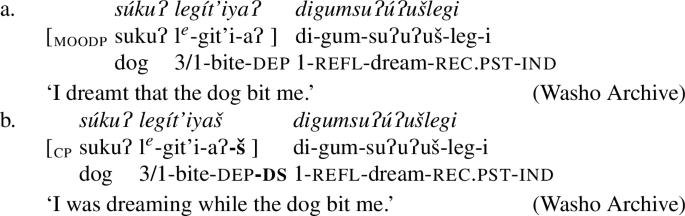

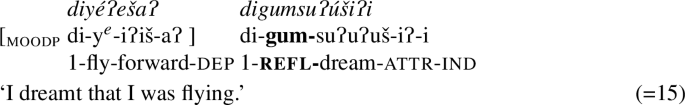

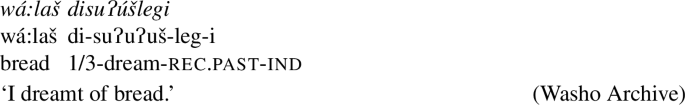

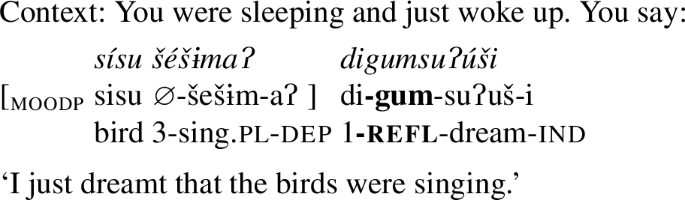

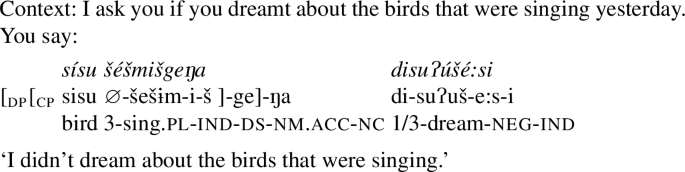

These traits are further corroborated by the examples below, demonstrated with the verbs ‘say,’ ‘dream,’ and ‘believe,’ respectively:

-

(14)

-

(15)

-

(16)

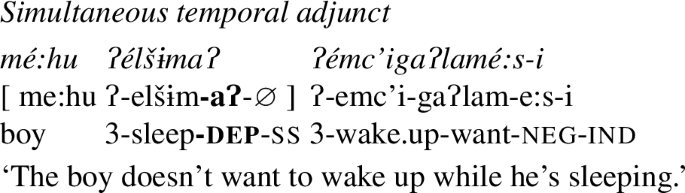

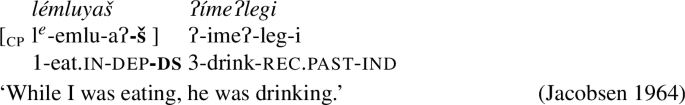

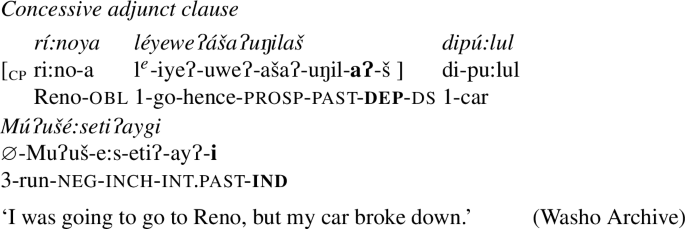

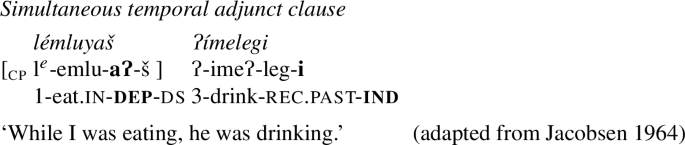

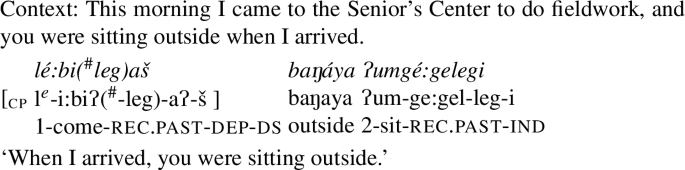

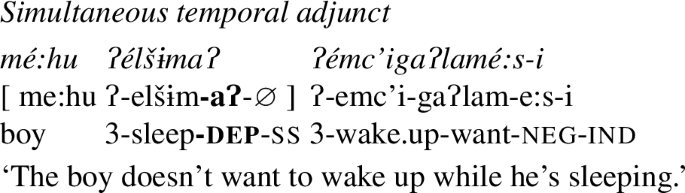

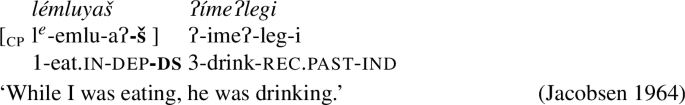

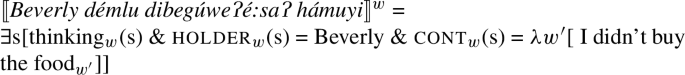

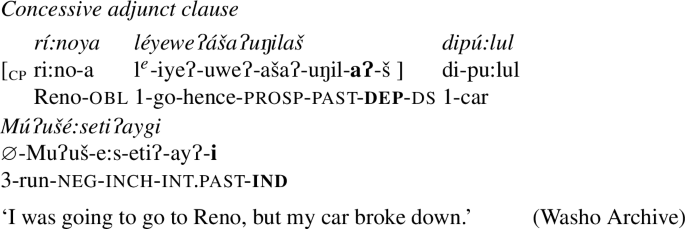

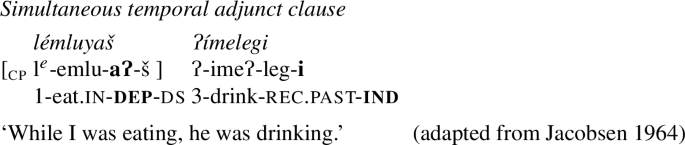

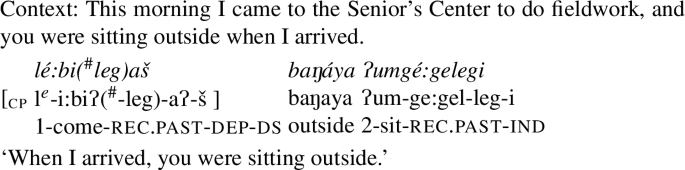

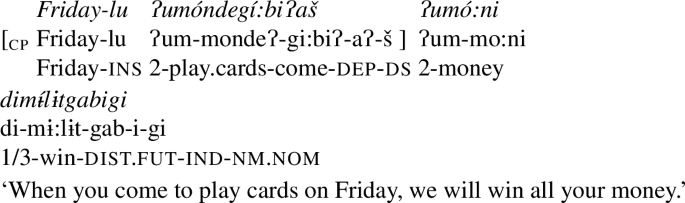

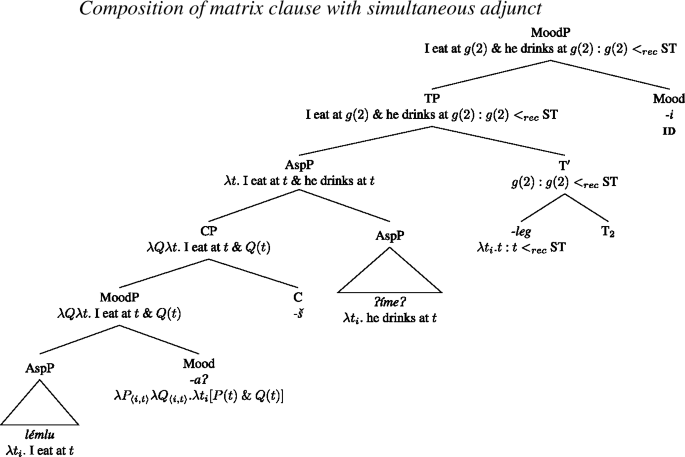

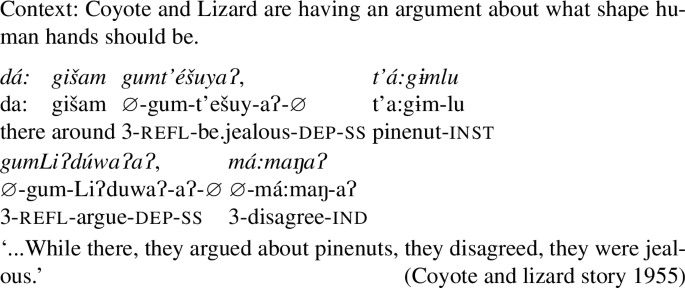

It will become important moving forward that, beyond clauses embedded by non-presuppositional verbs, the dependent mood marker -aʔ is also found in certain types of adjuncts, namely clauses conveying concession or temporal simultaneity. An example of the latter is given in (17) below:

-

(17)

In Sect. 5.5, we return to the discussion of adjuncts in order to show that the use of the dependent mood marker in both contexts is not an accident, but rather falls out from the meaning of this morpheme.

Below, Table 1 summarizes the descriptive morphological differences between clauses embedded by presuppositional and non-presuppositional verbs in Washo, which differ both in the choice of mood marker and in the presence or absence of the nominalizing suffix -gi/-ge. This table will be updated in the following section after we justify the syntactic structures we propose for these clauses.

Looking forward, both the presence or absence of nominalizing morphology and the difference in mood markers will play an important role in the semantics we assign to the two types of clauses. In the next section, we offer the proposed corresponding syntactic structures for both embedded clause types, and argue for a difference in embedding strategy—complementation vs. modification—before moving on to the semantic analysis.

3 The syntax of clausal embedding

The aim of this section is to elaborate on the respects in which the morphological and structural properties of clauses embedded by presuppositional verbs differ from those embedded by non-presuppositional verbs. In clausal nominalizations, we argue that the embedded clause is housed inside a larger DP structure in which the suffix -gi/-ge is the spell out of a syntactically-encoded index-hosting head (à la Elbourne 2005; Schwarz 2009), which introduces the flavor of “familiarity” of this clause type. Clauses embedded by non-presuppositional verbs differ in their lack of nominalization as well as in choice of mood marker. Crucially, we argue that these morphosyntactic differences correlate further with whether the embedded clause is selected as the thematic object of the matrix verb (-i-marked nominalizations), or is instead an adjunct modifier (-aʔ-marked clauses).

3.1 Clausal nominalizations are DPs

We begin with the discussion of clausal nominalizations. We adopt the claim that nominalized clauses are full CPs encased inside a DP (Peachey 2006; Hanink 2016). The hallmark of this clause type in Washo is the presence of the nominalizing suffix -gi/-ge at the right periphery of the embedded clause, which Hanink (2021) argues is the spell out of an index-hosting head “idx” within a larger DP structure. While Washo lacks a definite article, there is independent evidence, laid out in Hanink (2021), that Washo nominals do project a DP layer (based on e.g., tests identified by Bošković 2008). On Hanink’s account, the semantic role of idx is to introduce familiarity within the DP in the sense of Heim (1982), building on Elbourne (2005) and Schwarz (2009). We propose in the next section that it is idx that gives rise to the presuppositional “flavor” of certain clausal nominalizations, in that the index is able to pick out contextually salient propositional content via an assignment function.

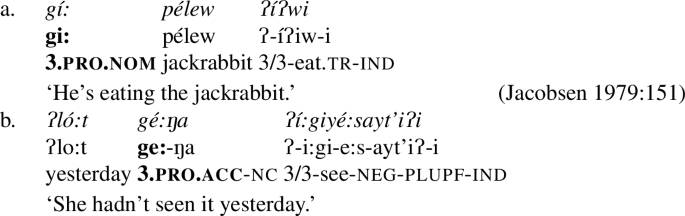

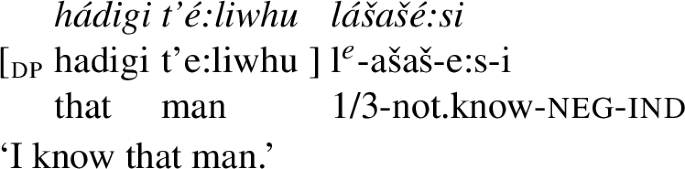

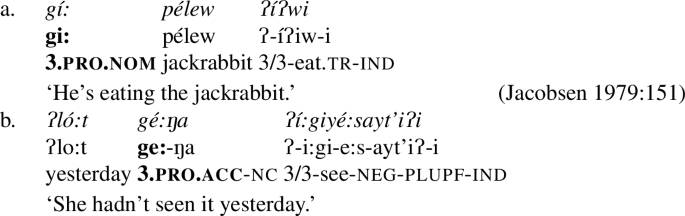

Before moving to this discussion, we first provide evidence that clausal nominalizations are truly DPs, based on both their case and distributional properties. First, the suffix -gi/-ge is found elsewhere in the language in the form of a third-person pronoun, where its form co-varies with case: gí: is the nominative form of the pronoun (18a), while gé: is the accusative form (18b):Footnote 7

-

(18)

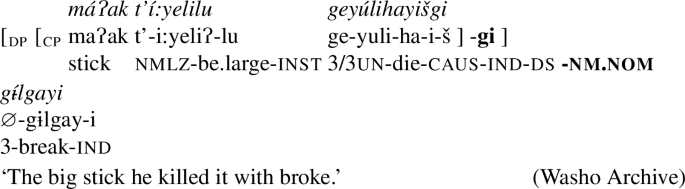

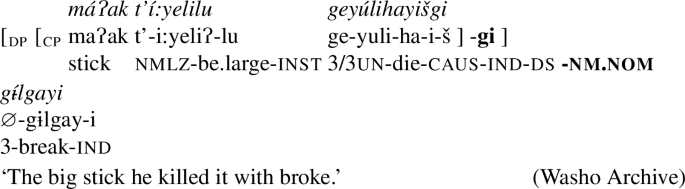

The case distinction in pronouns is moreover mirrored in clausal nominalizations in that the suffix -gi occurs when the argument resulting from the nominalization is the subject of the matrix verb, but surfaces otherwise as -ge. To exemplify this contrast, consider the use of -gi in the internally headed relative clause in (19). In this case, the entire nominalization refers to the stick that is being used to kill something; as this stick is the thematic subject of the matrix verb g-ílgayi ‘break,’ the nominative form of the suffix appears:

-

(19)

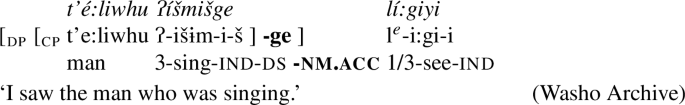

In all other cases, the accusative form -ge surfaces. The example in (20) shows a nominalized clause that acts as the object of the matrix verb, here ‘see,’ in which accusative case is duly assigned.Footnote 8

-

(20)

Accordingly, the complements of presuppositional verbs are marked with -ge, as they act as objects of the matrix verb (in a way to be made more precise below). We note however that we do find cases where nominalized propositions may be subjects of copular clauses, as in (21). In the analysis below, this follows from the fact that, like the complements of presuppositional verbs, sentential subjects are familiar and therefore nominalized (on a par with the obligatory definiteness marking observed in this construction in e.g., Hebrew, Greek, Persian and ASL; see discussion in Kastner 2015:178).Footnote 9 Bare clauses (with any mood marker) may not be subjects.

-

(21)

We note here that the language does not however allow nouns to embed complements (e.g., constructions of the form ‘the fact that …’), which have also been the focus of investigation in recent work on factivity and embedding (e.g., Moulton 2009, 2015; Kastner 2015; Elliott 2016).

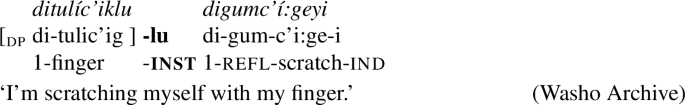

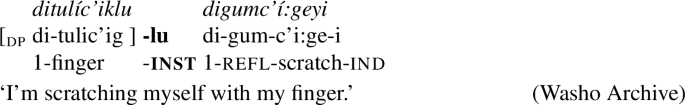

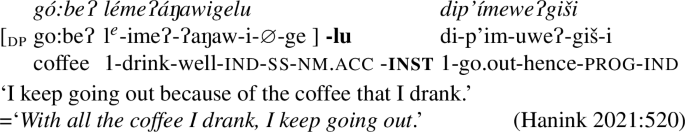

Aside from the above case properties, the DP-status of clausal nominalizations is supported by their distribution. For example, they can appear as the complements of postpositions (see also Peachey 2006), which always select nominal complements. We show this below with the instrumental postposition -lu, which in (22) selects for the nominal argument ditulíc’ik ‘my finger’:

-

(22)

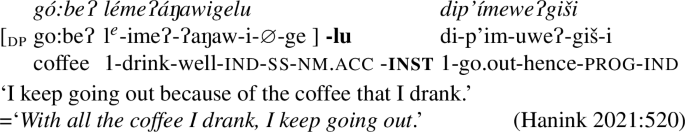

The same postposition can also select for a clausal nominalization, as in (23):

-

(23)

Taken together, the case and distributional properties of clausal nominalizations indicate that they are DPs. We now turn to lay out in more detail the assumptions we make about the structure of the DP in Washo.

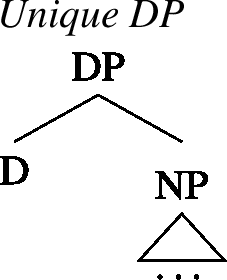

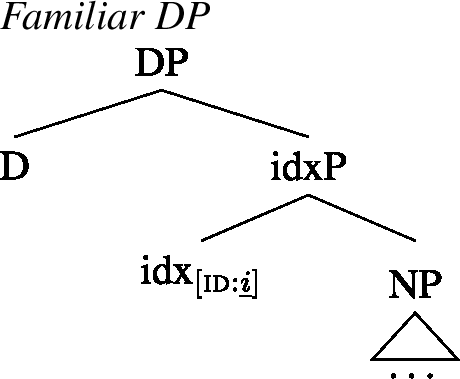

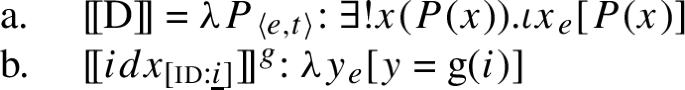

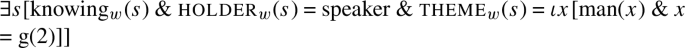

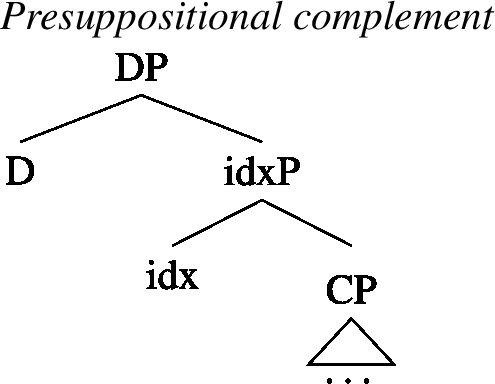

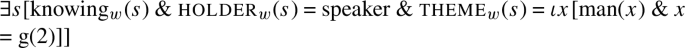

3.1.1 The structure of the Washo DP

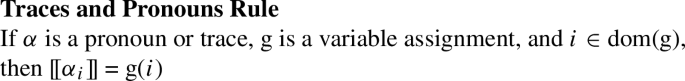

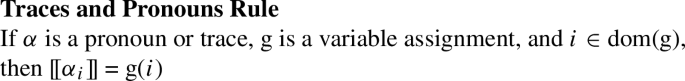

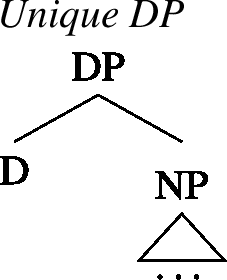

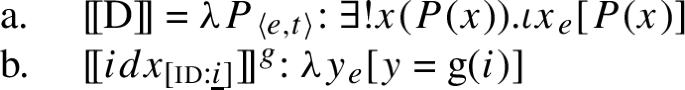

In the approach we adopt going forward, familiarity in definite descriptions (in the sense of Heim 1982) is divorced from the semantics of the definite article, and is instead encoded by a head idx that projects its own phrase (Simonenko 2014; Hanink 2018, 2021) within the extended projection of N. This approach to DP structure builds on proposals by Elbourne (2005) and Schwarz (2009), the latter of whom argues that anaphoric/familiar DPs differ from non-anaphoric (i.e., solely uniqueness-encoding) DPs not only semantically but also syntactically: DPs with non-familiar referents lack an index-hosting head in their functional structure. The semantic index structurally encoded within familiar DPs is then interpreted along the lines of a pronoun, for example by the Traces and Pronouns Rule of Heim and Kratzer (1998) (24), allowing it to be mapped back to an antecedent or to pick out a referent deictically (e.g., on a demonstrative use; Elbourne 2008).

-

(24)

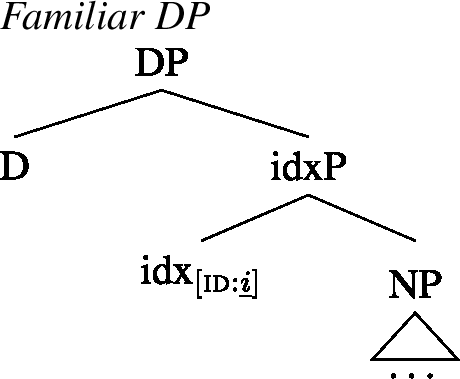

We adopt in particular the following implementation of this type of account found in Hanink (2021), according to which idx is in the extended projection (in the sense of Grimshaw 2005) of N (see also Simonenko 2014), and hosts semantic index features that contribute to an anaphoric or familiar meaning.

-

(25)

-

(26)

In (26), the meaning of idx is property-denoting, following an ident type shift (Partee 1986) of the individual-denoting index, while D has a classical Fregean/Strawsonian meaning:

-

(27)

Idx then acts essentially as a modifier that combines with the NP via Predicate Modification (Heim and Kratzer 1998), contributing an anaphoric meaning:

-

(28)

While we do not recreate all of her arguments here, Hanink argues that the distribution of gi/ge supports the proposal that this morpheme is the realization of idx (and not D). For instance, gi/ge is also observed in independent pronominal forms (29) (as mentioned above), as well as within the structure of demonstratives (30):

-

(29)

-

(30)

In particular, (30) provides evidence that idx is a head separate from D in that it can occur with the overt D head hadi- (adopting the structure of demonstratives as proposed by, e.g., Elbourne 2008). Going forward, we adopt this proposal for the structure of familiar DPs in Washo.Footnote 10

3.1.2 The structure of CP

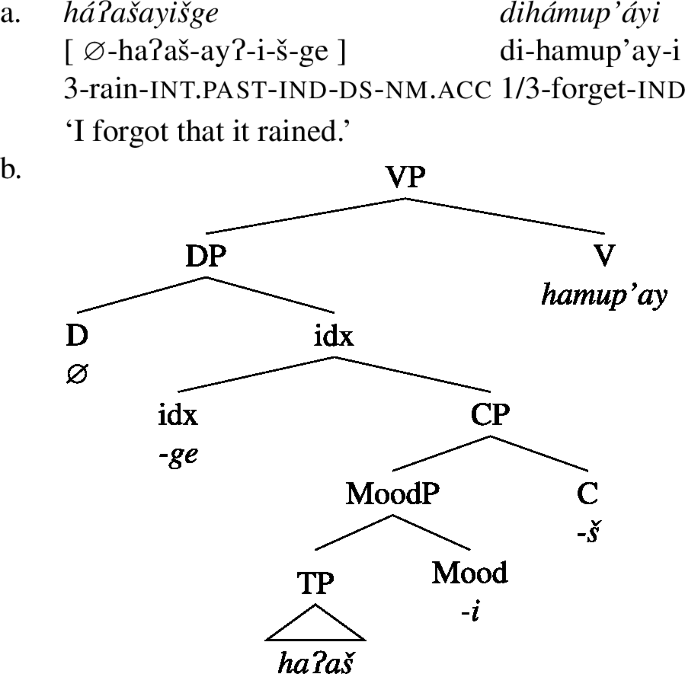

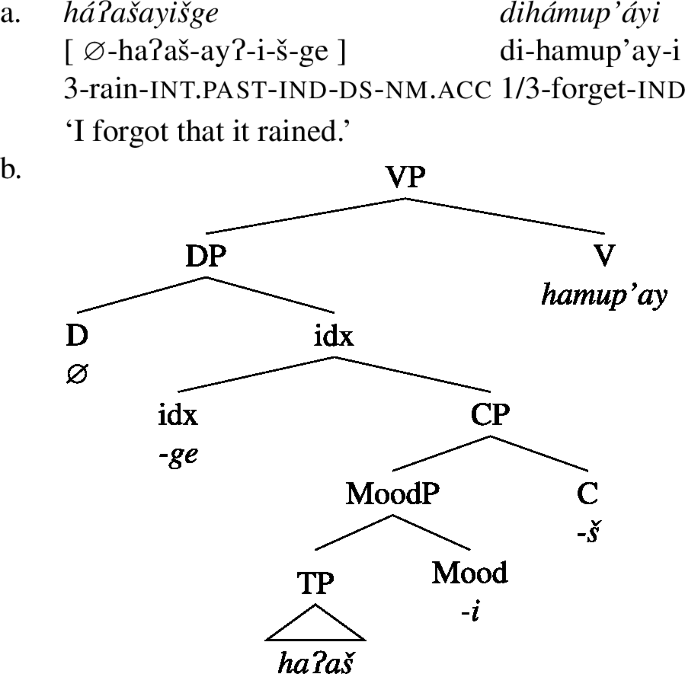

Turning now to the clausal level, we follow Peachey (2006) in the proposal that clausal nominalizations contain a fully spelled-out CP structure. Evidence that the material below this nominal layer constitutes a complete, independent clause comes from various morphological clues. First, these clauses are able to host tense information, which we treat as a realization of T (though tense is optional; see Bochnak 2016 for a detailed analysis of tense and temporal interpretation in the language). This is exemplified in (31) with the presence of the intermediate past suffix -ayʔ :

-

(31)

Second, these clauses require the presence of the independent mood suffix, which, as discussed in the previous section, is always realized as -i in nominalizations, and is accordingly observed in (31). Here we adopt the idea that mood markers are housed in their own projection, MoodP, which surfaces below CP (following e.g., Giannakidou 2009 for Greek). (As mentioned above, we return to arguments for the classification of this suffix as a mood marker in Sect. 5.) Finally, we also note that negation is allowed in these nominalizations, as shown through the example in (32):Footnote 11

-

(32)

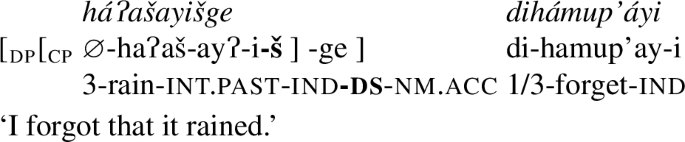

Finally, evidence for a CP layer comes from the fact that nominalized clauses exhibit switch reference morphology (Jacobsen 1967) where appropriate. Switch reference is common in languages of North America (McKenzie 2015) and refers to grammatical markers that track whether the subjects of two connected clauses are coreferential. In Washo, the different subject suffix -š appears when the subject of an embedded clause differs from the one in the clause it is embedded in (the same subject marker is null) (Jacobsen 1964:665, 1998). Consider again the example in (33). The subject of the embedded clause is pleonastic, while the subject of the matrix clause is the speaker. As these subjects are not coreferential, the different subject marker -š appears at the edge of the embedded verb ‘rain,’ as the final morpheme before the nominalizer -ge:

-

(33)

We follow Finer (1985) and Arregi and Hanink (2018, 2021) on the proposal that the different subject marker in Washo is hosted in C, thus constituting evidence for the presence of a CP layer in these nominalizations. As Arregi and Hanink point out, switch reference morphemes are the highest suffixes within the embedded clause (preceding only -gi/-ge in clausal nominalizations), supporting this view. Note that there are no other complementizers in the language.Footnote 12

Taking these points together, we schematize the structure we adopt for clausal nominalizations in (34b), in which the entire clause is selected for by idx, which itself is selected by D.Footnote 13 This DP is then selected as the complement of the matrix verb (see Hanink 2021 for a treatment of the realization of case on these nominalizations). Note that because Washo is a largely head-final language, the structure is left-branching aside from the DP, in which nominal projections are neutrally head initial.Footnote 14

-

(34)

3.1.3 Presuppositional verbs select their complements

As indicated in the proposed structure for clausal nominalizations in (34b), the nominalization of the embedded clause results in the selection of a DP argument by the matrix verb, which in this particular case is hámup’ay ‘forget.’ This is consistent with the transitive nature of these verbs elsewhere in the language: verbs in this class select thematically for an internal argument (35)–(36) and are observed to mark case on the nominalizations they select for (36). While case-marking in Washo is never realized on bare nominals, it is the accusative form of the pronoun that surfaces as the direct object of ‘see’ in (36).Footnote 15

-

(35)

-

(36)

We take the transitive status of the verbs that select them as well as the obligatory case-marking of nominalized clauses (see e.g., Picallo 2002) to be uncontroversial evidence for the argumental status of these clauses.Footnote 16 In the next section, we turn to clauses embedded by non-presuppositional verbs, which differ from nominalized clauses in both this regard and in other behaviors.

3.2 The structure of bare clausal embedding

Clauses embedded by non-presuppositional verbs differ foremost from their presuppositional counterparts in that they are not nominalized and therefore lack a DP layer altogether. However, they also differ in two other ways. First, clauses embedded by non-presuppositional verbs lack a CP-layer.Footnote 17 Instead, we submit that these clauses are MoodPs, headed by the dependent mood marker -aʔ, thus constituting a type of semi-reduced clause in the language (though not much hinges on this reduced status). More importantly, the behavior of clauses embedded by non-presuppositional verbs reveals that these -aʔ clauses are not complements at all, but are better understood as adjuncts. We therefore argue instead that these clauses are not selected but serve as verbal modifiers, much in line with recent proposals for English by e.g., Elliott (2016, 2017).

3.2.1 Motivating the lack of CP

The first piece of evidence for the lack of a CP layer in clauses embedded by non-presuppositional verbs comes from the fact that clauses embedded by these verbs are the only subordinate construction in the language that we know of where the switch reference marker -š doesn’t surface (noted also by Jacobsen 1964:639–641). As discussed above for clausal nominalizations, recall that the switch reference marker surfaces in any embedded clause whose subject differs from the one in the clause embedding it. This means that we should, in principle, expect the switch reference morpheme -š to surface in the following example, in which the subjects of the two clauses differ:

-

(37)

Though the subject of the matrix clause is some female individual and that of the embedded clause is the speaker, the different subject suffix does not appear. We therefore contend that these clauses do not contain a CP layer, thereby explaining the otherwise puzzling lack of switch reference morphology.

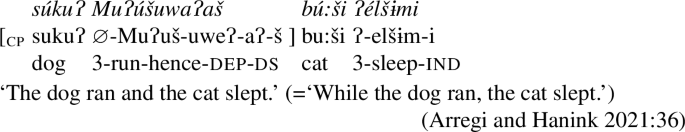

Corroborating this argument is the fact that, aside from -i-marked clausal nominalizations, there are other clauses that surface with the dependent mood marker -aʔ, but nevertheless do display switch reference morphology where expected. Such cases are found for example in the temporal adjuncts discussed above in Sect. 2, which convey a simultaneous reading. Adjuncts of this kind are exemplified below in (38) and (39):

-

(38)

-

(39)

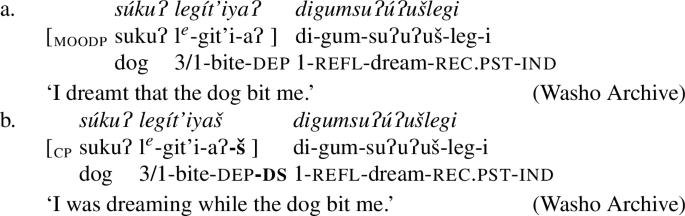

Such examples show that the different subject marker is not simply incompatible with the dependent mood marker for independent reasons; its absence in clauses embedded by non-presuppositional verbs is thus a signal for the lack of C in the structure. We conclude this argument with the following minimal pair, which highlights the correlation between meaning difference and the appearance of switch-reference marking:

-

(40)

Aside from switch reference, an additional piece of evidence for the lack of C comes from fronting behavior. One characteristic of clauses embedded by non-presuppositional verbs is that they generally remain in their clause-internal position, as exemplified by the typical SOV order in (41) (repeated), and (42):Footnote 18

-

(41)

-

(42)

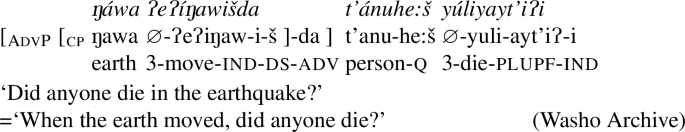

Other -aʔ-marked clauses however, such as temporal adjuncts, behave differently. These do prefer to front, which, alongside the facts from switch reference, is consistent with the idea that they are full CPs, which are known to front cross-linguistically:

-

(43)

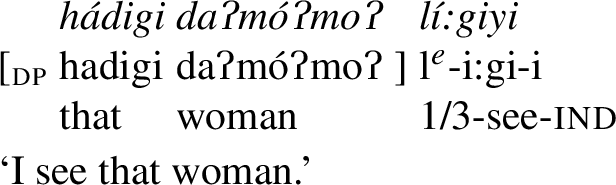

This in-situ preference of non-presuppositional -aʔ-clauses also differs from that of clausal nominalizations, which, like temporal adjuncts, strongly prefer to front (a behavior common for heavy NPs such as clausal nominalizations). Consider the following example in (44), in which the matrix clause subject daʔmóʔmoʔ ‘woman’ appears in a non-canonical position following the nominalization, rather than in its expected initial position in an SOV word order:

-

(44)

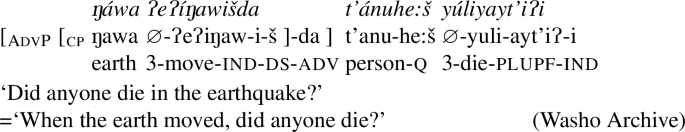

Other instances exemplifying the fronting of CPs include, for example, adverbializations of clauses formed with the suffix -da as in (45) and (46), which receive a serial interpretation:Footnote 19

-

(45)

-

(46)

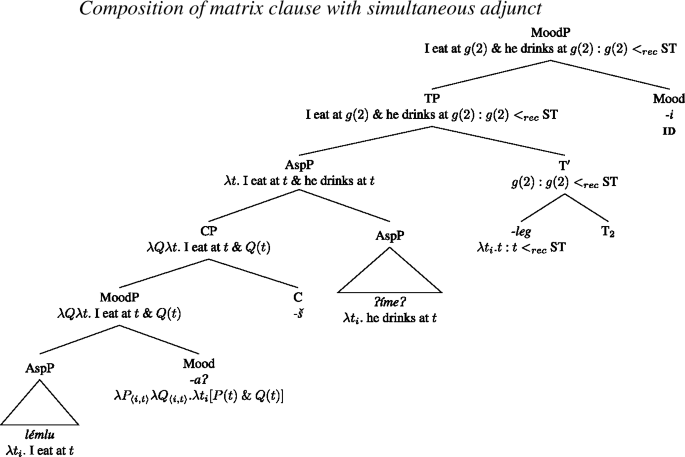

Taken together, the facts from switch reference and fronting behavior suggest that there is no CP layer within -aʔ-clauses embedded by non-presuppositional verbs. We therefore propose the structure in (47b) for this type of embedded clause, in which MoodP adjoins low, to VP:

-

(47)

3.2.2 Non-presuppositional verbs do not select

As the structure in (47b) makes clear, our proposal is that non-presuppositional verbs differ from their presuppositional counterparts in that the former do not subcategorize for a DP complement. In fact, they do not select for a complement at all, but are modified instead by MoodP adjuncts. This proposal is motivated by the behavior of non-clausal arguments of non-presuppositional verbs: the same verbs that embed MoodPs do not select complements elsewhere in the language.

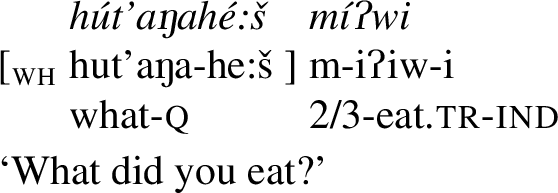

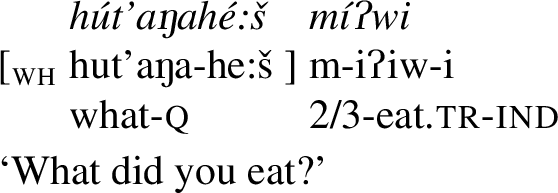

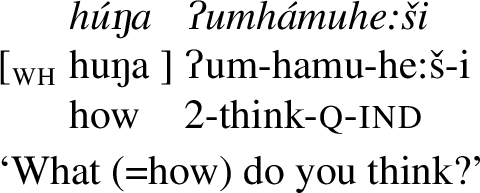

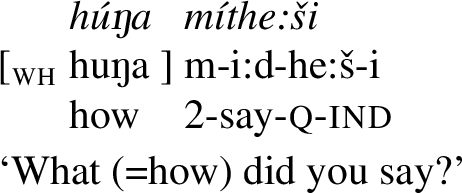

This claim is corroborated for example by the behavior of wh-questions in the language. The canonical wh-pronoun ‘what’, hút’aŋahé:š, can be selected for by transitive verbs such as iʔiw ‘eat’ (48):

-

(48)

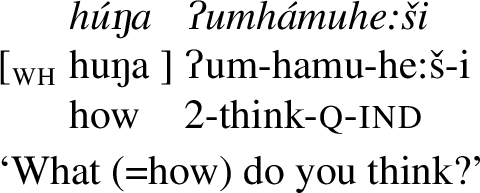

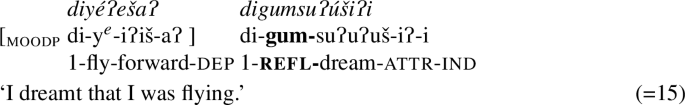

However, in similar questions involving non-presuppositional verbs such as ‘think’ (49) and ‘say’ (50), the wh-pronoun huŋa ‘how’ is used instead.

-

(49)

-

(50)

Crucially, the cut here follows precisely the adjunct vs. argument distinction of wh-words, revealing that non-presuppositional verbs cannot select for argument wh-words such as ‘what’, but only adjunct wh-words, such as ‘how.’ The behavior of clausal embedding by both verb types is thus mirrored in the domain of wh-questions.

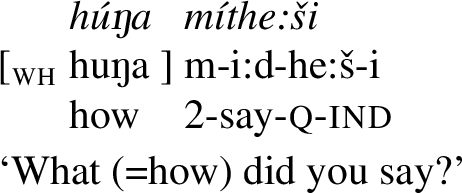

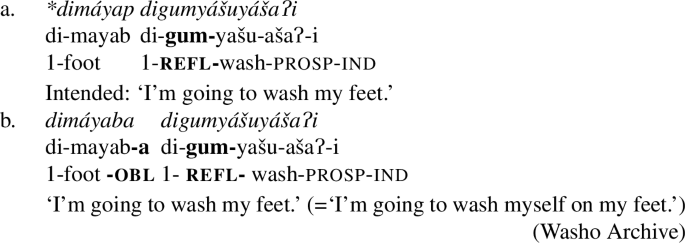

Further evidence that non-presuppositional verbs do not select for -aʔ clauses comes from reflexives. Reflexivization in Washo is marked by the verbal prefix gum- (invariant for person and number), which initial evidence suggests is not agreement but a valency-reducing marker (in the sense of Marantz 1984).Footnote 20 The presence of this prefix therefore unsurprisingly removes the possibility of an additional internal argument, as the reflexive object must fill this thematic role. This effect is demonstrated in (51), which shows that the verb yášu ‘wash’ is reflexive in Washo, and thus cannot take a direct object (51a). The notional ‘object’ is therefore expressed with the oblique case marker, -a (51b); the reflexive prefix cannot co-occur with another notional internal argument without this oblique case-marking.

-

(51)

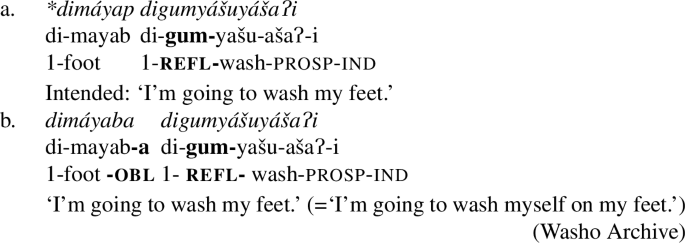

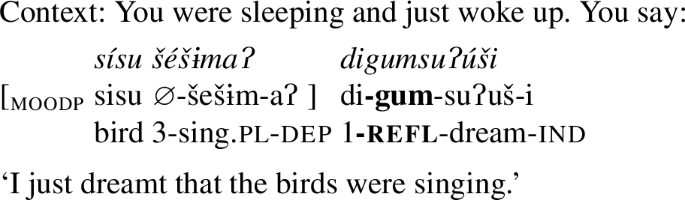

Crucially, certain non-presuppositional verbs show reflexive marking in Washo, but may nevertheless embed -aʔ clauses. Take for example the verb ‘dream,’ as in (52). The fact that the prefix gum- is present rules out the possibility that the -aʔ clause is selected as the object of the matrix verb (the example in (40b) above moreover shows that this reflexive marking is also present when the matrix clause is accompanied by an adjunct, in which dream is likewise intransitive).Footnote 21

-

(52)

The reflexive use of ‘dream’ in (52) can be contrasted moreover with its transitive form in (53), which lacks the reflexive prefix, and is therefore able to directly select for the complement wá:laš ‘bread’.

-

(53)

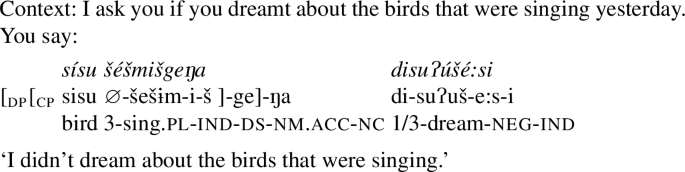

This line of reasoning predicts that, without the reflexive, non-presuppositional verbs can select for nominalizations.Footnote 22 This prediction is born out, as shown by the contrast between (54) and (55). The verb ‘dream’ in (54) is reflexive and occurs with an -aʔ-marked adjunct, while in (55) it is not reflexive and selects for a nominalized clause. Crucially, the two have different meanings: the embedded clause in (54) is interpreted as a ‘that’-clause, while in (55) it is interpreted as an internally headed relative.

-

(54)

-

(55)

In sum, clauses embedded by non-presuppositional verbs are not selected, but are instead VP modifiers, as represented in the structure in (47b). These types of clauses are therefore different from the complements of presuppositional verbs in both their size, in their choice of mood marker, and in their mode of embedding.

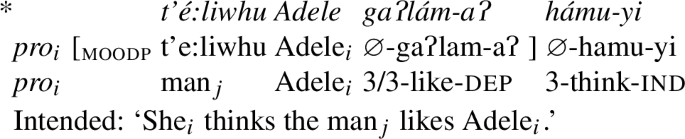

As a final note on the height of adjunction, we offer evidence from Condition C effects that the CP adjunct must attach low, below the subject, as schematized in the tree above in (47b). This line of reasoning builds on Clem’s (2019) claims for the height of CP adjunction in Amahuaca: if the MoodP is generated below the main clause subject, we then expect Condition C effects to arise under the relevant configurations (see also Arregi and Hanink 2021 for this line of reasoning applied to other embedded clause types). This is borne out in Washo: in (56), the presence of the co-indexed R-expression inside the embedded clause triggers ungrammaticality. (Due to the pro-drop in this sentence, it is crucially not obvious whether the adjunct is center-embedded or fronted, however we indicate pro in initial position here to keep with the evidence of where the adjunct is first merged.)

-

(56)

3.3 Summary

To summarize, there are clear syntactic differences between the clausal embedding strategies of presuppositional and non-presuppositional verbs in Washo. We have shown that presuppositional verbs select directly for full, nominalized clauses marked with the independent mood marker -i, while clauses embedded by non-presuppositional verbs are smaller MoodPs, headed by the dependent mood marker -aʔ. Importantly, we have also shown that non-presuppositional verbs do not select for the clauses they embed; we have argued that MoodP in these cases is an adjunct to VP. Table 2 expands on Table 1, giving a further classification of the differences between clauses embedded by both verb types.

An aside: A reviewer asks whether MoodPs differ from clausal complements in barring extraction. As far as we know, Washo however does not permit extraction out of any clause type (e.g., relative clauses are exclusively internally headed (Jacobsen 1998), while wh-expressions remain in-situ, even in long-distance questions). We point out that we in fact (correctly) predict that ‘that’-clauses of both types should bar extraction; clausal nominalizations constitute Complex Noun Phrase islands while -aʔ-clauses are adjuncts and are therefore also islands.

Having laid out the syntactic properties of clausal embedding in Washo, we now turn to the discussion of the semantic differences correlated with the two structures, where we offer a more complete picture of how the syntax and semantics work together in Washo in order to derive the difference between both types of embedded clauses with mechanisms that are independently required by the language.

4 Clausal embedding and presuppositions

We show below in Sect. 5 that the interpretation of the two types of embedded clauses described above is directly related to the differences in their underlying structures. The differences in meaning of these clauses is conditioned by the verbs that embed them, as well as the characteristics of the embedded clauses themselves. Before doing so however, we briefly lay out in this section some relevant background on attitude verbs, and elaborate on how recent semantic and syntactic literature are at odds with one another in certain key respects.

4.1 Decomposing attitude verbs

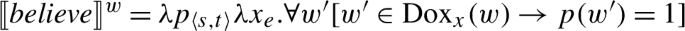

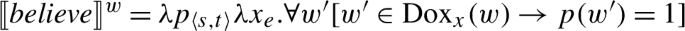

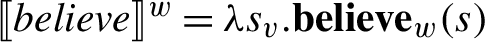

A version of the classical Hintikkan semantics for propositional attitude verbs (Hintikka 1969) is given in (57). Here, the attitude verb relates a proposition p, denoted by the complement clause, and an individual x, the subject. The relation encoded in believe is that p is true in all of x’s doxastic alternatives.

-

(57)

This picture can be augmented to accommodate factive verbs by simply adding the presupposition that p is true in the evaluation world to the lexical entry directly. In this way, know can be modeled similarly to believe with an extra presupposition, as in (58).Footnote 23

-

(58)

Thus, on this view, the attitude verb selects directly for its complement, and a factivity presupposition is built in directly to its lexical semantics.

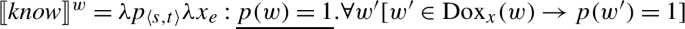

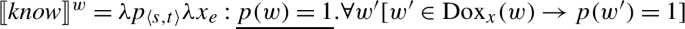

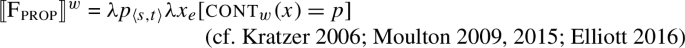

Recently, a strand of research has developed that builds on but revises this classical view, developing a more explicit compositional analysis while maintaining a broadly Hintikkan view of attitude ascriptions as quantifying over possible worlds. In the work of Kratzer (2006) and Moulton (2009, 2015), attitude verbs are taken to relate eventualities to a piece of content. On a more extreme neo-Davidsonian view, Elliott (2016) analyzes propositional attitude verbs as simple predicates of events or states, with the content and holder of the attitude introduced separately. In his analysis, believe simply describes believing events (or states), as in (59).Footnote 24

-

(59)

Given that the only argument position is for an event or state, the content of the belief, that is, the complement clause, must be integrated into attitude reports in a different way. There is also no room in this type of verb meaning for a factivity presupposition, which encodes a relation between the embedded proposition and the evaluation world, the former of which is not an argument of the verb. Under this type of analysis, the composition of an attitude verb and its complement is accordingly more complicated than the analysis in (57)–(58). Let us begin to unpack this here.

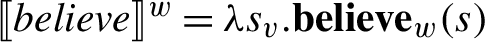

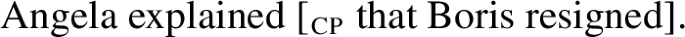

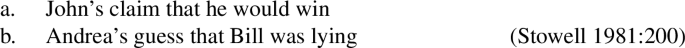

Building on Kratzer (2006), Moulton (2009, 2015) argues that complement clauses, and more generally that-clauses in English, do not denote propositions (i.e., sets of possible worlds) directly; rather, they denote sets of individuals of a certain kind (see also Moltmann 2008, 2020). In particular, Moulton builds on the insights of Stowell (1981), who argues that that-CPs are not selected by nouns, but are appositive to them (see also Grimshaw 1990; recent arguments against this idea are given in Hankamer and Mikkelsen 2021). Stowell argues that such CPs should denote predicates of individuals, given that the nominals they modify are of that type.

-

(60)

In an example such as (60a) for instance, Stowell observes that claim does not seem to be assigning a θ-role to the that-clause, rather, both refer to the same thing: the claim itself. Building on this idea, Moulton proposes that that-clauses denote sets of individuals whose content is a certain proposition, as in (61).

-

(61)

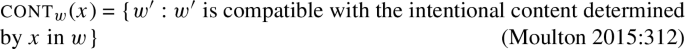

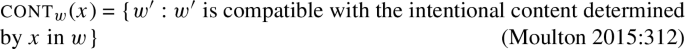

The link between the embedded proposition and its content is mediated by a function contw (Kratzer 2006), which takes an individual x and returns the set of worlds compatible with the content of x, as in (62). A modal base is thus projected from an entity other than a world (Hacquard 2006, 2010; Kratzer 2006).

-

(62)

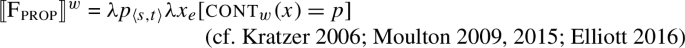

The compositional glue is a functional head in the high periphery of embedded clauses that transforms propositions into properties of individuals. We refer to this head as F\(_{\text{\textsc{prop}}}\) and give its denotation in (63). The result of combining F\(_{\text{\textsc{prop}}}\) with the proposition denoted by the complement clause is a predicate of individuals whose content is equated with the proposition denoted by the clause, as in (64).Footnote 25

-

(63)

-

(64)

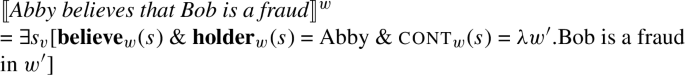

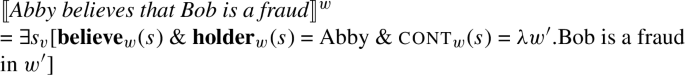

One extra step is needed in order to combine the meaning in (64), which is of type 〈e,t〉, with the attitude verb in (59), which is a predicate of events of type 〈v,t〉. Here we follow Lasersohn (1995) and Elliott (2016) in positing no model-theoretic type distinction between individuals and events/states. This move now makes it possible for the matrix predicate to combine semantically with the embedded clause via Predicate Modification (Heim and Kratzer 1998). The result is that a sentence containing an attitude ascription can be given the semantics in (65).Footnote 26 Stated in prose, (65) says that there is a state of believing, the holder of which is Abby, and the content of which is the proposition that Bob is a fraud.

-

(65)

An important question that emerges from this view of attitude predicates is the relationship between the matrix verb and the clause it embeds. The reduction of attitude verbs to event predicates as well as the view of that-clauses as property-denoting leads to a view according to which clauses embedded by these verbs are always modifiers, and selectional relationships are not necessary. Elliott (2016) builds on this idea and makes the strong claim that that-clauses and DP arguments of the types in (66) and (67) differ fundamentally in that the latter are always selected, while the status of the former as modifiers means that they are not.

-

(66)

-

(67)

This revised view also suggests that factivity distinctions are not to be found in the lexical semantics of attitude verbs, for these are simply predicates of events or states (see also Moulton 2009:Chap. 5). On this decompositional view, factivity would need to be integrated through composition with the complement clause; Kratzer (2006) for example suggests that there are different flavors of complementizers that can encode presuppositions. We now turn to some recent ideas on how presuppositional distinctions can be tracked by syntactic structure.

4.2 Attitude verbs and selection

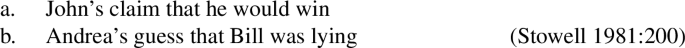

The idea that that-clauses are always modifiers in the sense described above is at odds with recent proposals regarding the syntax of clausal embedding. For example, Kastner (2015) proposes a direct syntax to semantics mapping in that presuppositional and non-presuppositional verbs have different selectional requirements: the former select a DP (68), while the latter select for a complement clause directly (69).

-

(68)

-

(69)

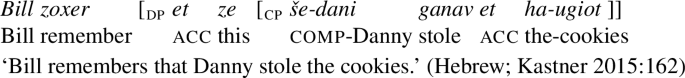

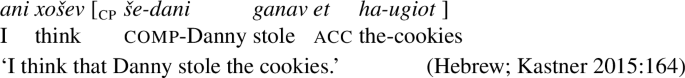

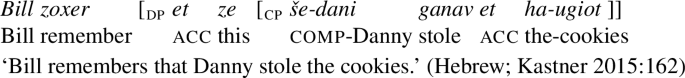

Kastner argues that the difference in interpretation of presuppositional and non-presuppositional verbs reflects this difference in structure. Specifically, he adopts Heim’s (1982) approach to familiarity and argues that the D head in (68) introduces a presupposition that there is a familiar entity in the discourse. Meanwhile, complements without D have no familiarity restrictions, as in (69). His evidence comes from well-known extraction asymmetries between presuppositional and non-presuppositional complements (Kiparsky and Kiparsky 1970), as well as morphological evidence from Hebrew that demonstrates the different categorial status of complements overtly: in presuppositional complements, the demonstrative ze ‘this’ introduces the that-clause, as in (70), while in non-presuppositional complements, no such definite morphology is present, as shown in (71).Footnote 27

-

(70)

-

(71)

A consequence of this analysis is that presuppositionality is not a semantic property of attitude verbs, but is rather derived from the presence (or absence) of D, which introduces a familiarity presupposition, in the embedded clause.Footnote 28

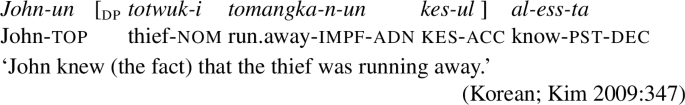

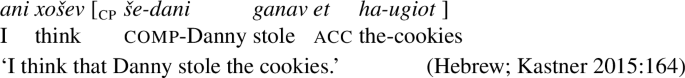

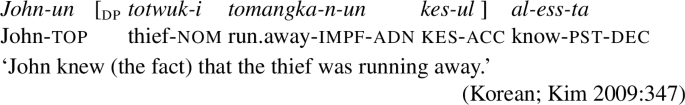

Independent cross-linguistic support for the view that the ‘nouny-ness’ of the complement correlates with a presuppositional requirement of familiarity comes from Bogal-Allbritten and Moulton (2017), who build on Kim (2009) and argue for a notion of familiarity implicated in nominalized clauses in Korean, as in (72), in which the complement of presuppositional ‘know’ is likewise nominalized:

-

(72)

This is similar to what we find in Hebrew and Washo insofar as nominalized clauses in these languages are to be found with presuppositional verbs only. The problem that arises then from the treatment of that-clauses and their cross-linguistic kin uniformly as modifiers (as on their property analysis) is how to account for the differences between clauses embedded by presuppositional and non-presuppositional verbs: there is no way to treat the embedded clause in (68) as a modifier, given its status as an individual-denoting DP.

While similar to Kastner’s, our syntactic analysis of presuppositional vs. non-presuppositional complements in Washo is slightly different. Like Kastner, we propose that presuppositional complements are larger than non-presuppositional complements. The former come with DP material encasing a CP, in which the suffix -gi/-ge is the realization of the functional head idx, which encodes familiarity. Further, our non-presuppositional complements lack a DP layer. Crucially however, there are two important differences between our analysis and Kastner’s. First, while Kastner assumes that there is a silent N head in the DP structure (see also Elbourne 2013), this is not motivated for Washo. Recall crucially that in Washo, there is no overt nominal: clause-embedding nouns such as ‘fact’ or ‘rumor’ are unattested in the language. In Washo, nominalizing morphology is simply a suffix on the verb, and no noun is ever pronounced between this morphology and the CP it embeds. Unless we want to rely on the claim that such a noun is always silently encoded in the structure—which is unattested in Washo—the treatment of the clauses embedded by presuppositional verbs as modifiers is untenable.

Second, the Washo data reveal not only a difference in size and shape, but also a difference in embedding strategy: clauses embedded by presuppositional verbs are selected, while those embedded by non-presuppositional verbs are modifiers, contra Kastner’s proposal. The picture that emerges from Washo therefore yields two important results. First, it provides novel and cross-linguistic support for Kastner’s proposal that presuppositional verbs select for DPs. Second however, it challenges the view that non-presuppositional verbs select for embedded clauses at all, and in doing so lends evidence to a property analysis of that-clauses according to which certain (but not all) embedded clauses are not selected, along the lines of Elliott’s (2016) proposal. Thus, there is evidence from Washo that both strategies—selection and modification—can co-exist as clausal embedding strategies.

In the next section, we derive the two modes of embedding that have been discussed for Washo. We show that presuppositionality derives from the familiarity presupposition introduced by the nominalizing layer, while the lack of presuppositionality effects in other embedded clauses is due to an alternate mode of embedding: modification. We show that these are the two strategies for embedding more generally throughout Washo, and sketch extensions to the analysis of other embedded clauses in the language.

5 Deriving clausal embedding in Washo

We present in this section an analysis of clausal embedding in which the syntax and semantics work together to derive the range of behaviors that we have discussed above. First, the DP material in clausal nominalizations contributes familiarity to the content expressed by the proposition denoted by the embedded clause. Embedded clauses without a DP later carry no such presupposition, and are adjuncts to the intransitive attitude predicates they modify. Second, the mood markers -i and -aʔ in Washo have different meanings, which reflect the different roles played by the clauses they occur in. These roles govern (in part) whether an embedded clause is a complement or a modifier of the verb that embeds it.

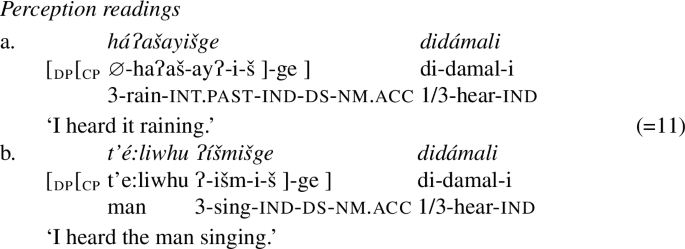

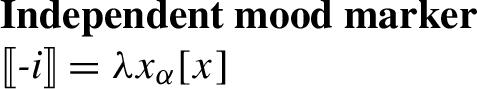

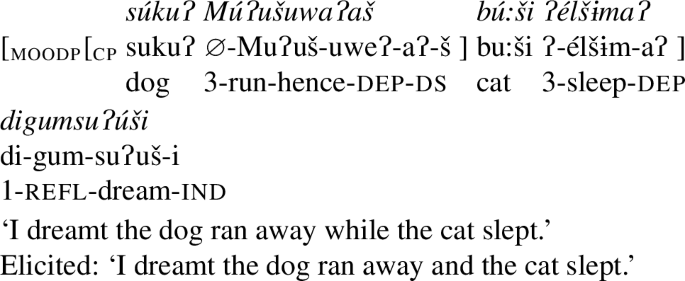

5.1 The semantics of independent and dependent mood markers

Let us begin with a modest proposal for the semantics of the mood markers -i and -aʔ, which appear in clauses embedded by presuppositional and non-presuppositional verbs, respectively. Before stating our proposal, we note that justification for the treatment of these suffixes as Mood comes not only from their relative position in the clause, but also from the fact that they are in complementary distribution with other clause-typing Mood markers in the language, for instance the imperative (-∅), optative (-hi), and horative (-hulew) moods (Jacobsen 1964:654–664).

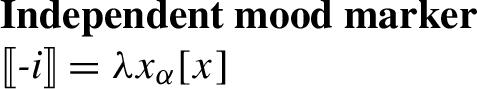

First, given its wide distribution and default status for matrix clauses (e.g., (7), repeated in (73)), we propose that the independent mood marker -i denotes the identity function, i.e., it is semantically vacuous, as shown in (74).

-

(73)

-

(74)

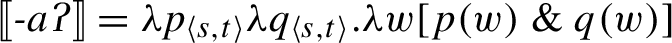

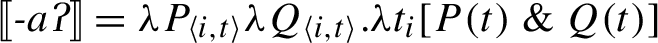

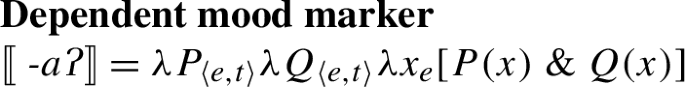

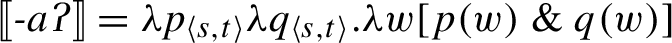

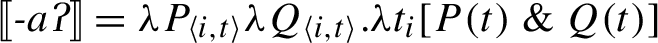

Meanwhile, we propose that the dependent mood marker -aʔ has the semantics of conjunction. Specifically, in the case of clauses that modify non-presuppositional verbs, -aʔ conjoins predicates of individuals, as in (75).

-

(75)

This semantics explains two crucial characteristics of -aʔ clauses. First, it explains why clauses of this type do not take on presuppositional interpretations: they lack the DP layer containing both D and the idx head found in the structure of clausal nominalizations. We contend that idx imposes restrictions on its complement, such that it may only select for C, and not Mood, ruling out its selection of bare -aʔ-clauses. In the case of non-presuppositional modifiers, the 〈e,t〉-type embedded clause instead combines with the matrix attitude predicate via the dependent mood marker (shown in more detail in Sect. 5.4). Second, it explains why clauses with this mood marker cannot stand alone, i.e., why -aʔ-marking is restricted to subordinate clauses. In Sect. 5.5, we show that the conjunction semantics of -aʔ can be generalized to conjoin other types of semantic objects, which provides an explanation for its distribution in other types of subordinate clauses, particularly adjunct clauses.

Our semantic analysis of these moods does not contain a modal or temporal component, as is common in the analysis of verbal mood in other languages (e.g., Farkas 1985; Portner 1997; Quer 2001; Schlenker 2005; Giannakidou 2009; Matthewson 2010; among others. See Portner 2018 for a recent overview). There are nevertheless conceptual similarities between our analysis of mood in Washo and mood distinctions found in other languages. First, as in many other mood systems, one mood (the independent mood -i) is treated as a default with a trivial semantic value (e.g., Portner 1997; Schlenker 2005). Second, we note that moods in Washo—not only the independent and dependent moods, but more broadly—have to do with clause-typing, which is a major function of moods cross-linguistically (dubbed “sentence mood” by Portner 2018). In this connection, the independent/dependent mood distinction that we find in Washo appears to find conceptual kin in what are known as the independent and conjunct orders in several Algonquian languages. Descriptively, the independent order is typically used in matrix clauses, while conjunct order is typically used in many types of subordinate clauses (see e.g., Brittain 2001).Footnote 29 Just like verbal moods in more familiar languages, the exact distribution of these orders is subject to cross-linguistic variation within the Algonquian family. Also similar to Washo, these orders stand in opposition to other orders such as the imperative. While a full analysis of mood marking in Washo is beyond the scope of this paper and requires further research, we believe that the foundations we have laid out here for the independent and dependent moods will carry over to a more detailed future analysis.

In the rest of this section, we detail the semantic composition of presuppositional and non-presuppositional embedded clauses in Washo, based on the syntax we put forward in Sect. 3 as well as on the aspects of the semantic analyses of attitude predicates and that-clauses we introduced in Sect. 4.

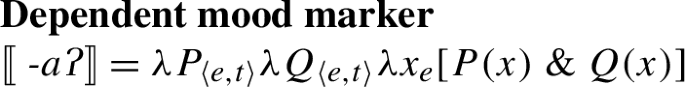

5.2 Presuppositional complements and the role of nominalization

We now turn to the derivation of the clausal complements of presuppositional verbs. We adopt the idea introduced in Sect. 4 that the role of a functional element F\(_{\text{\textsc{prop}}}\) is to turn the proposition-denoting embedding clause into a property of individuals whose content is expressed by that proposition. In our implementation, we treat F\(_{\text{\textsc{prop}}}\) as an optional type-shift as in (76) (cf. Simeonova 2018), which applies at the level of TP, instead of as an obligatory syntactic node in the clausal periphery.

-

(76)

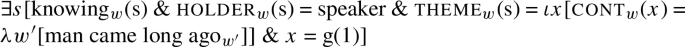

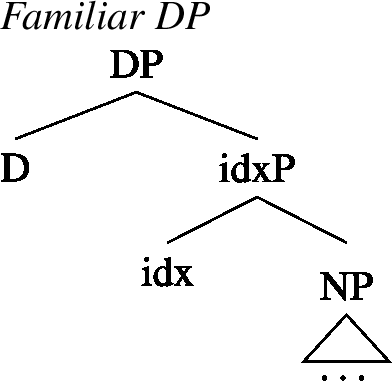

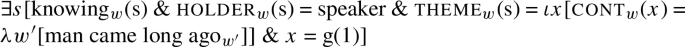

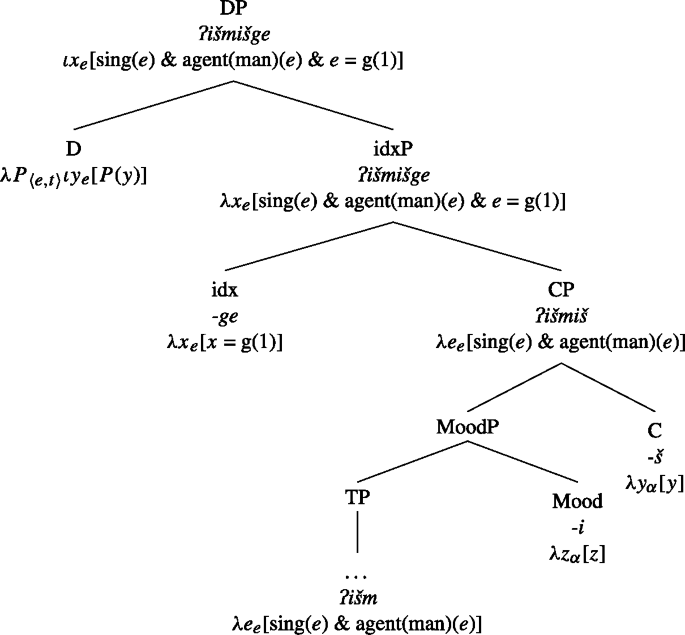

Adopting the assumptions about the structure of the DP and CP outlined in Sect. 3, the nominalizing DP-layer hosts a silent D head as well as the head idx, which is overtly realized as -gi/ge. This idx head selects for its complement clause directly. The derivation of a clausal nominalization embedded by the verb ‘know’ then proceeds as in (77). First, the embedded clause is formed and undergoes the F\(_{\text{\textsc{prop}}}\) type-shift, returning a set of individuals whose content is specified by the proposition ‘the man came long ago.’ Second, this embedded clause composes with both Mood and C, both of which denote the identity function in this case. Third, the resulting property denoted by the CP undergoes Predicate Modification with idx, resulting in a property of individuals specified by this content that are also familiar. Finally, this property composes with D, resulting in the unique individual whose content is specified by the embedded proposition, and which is identical to the referent mapped to 1 by the assignment function g.Footnote 30

-

(77)

Diverging from Kastner (2015) and related claims in Bogal-Allbritten and Moulton (2017), we take the presence of idx to be responsible for encoding the familiarity of the content expressed by the embedded clause, which is present in nominalized complement clauses, but absent in embedded bare clauses (as idx is selected by D, and only presuppositional verbs select for DPs); cf. Sect. 3.2.2. The main idea is that the assignment function will map the index (‘1,’ in the above example) to the salient individual whose content expresses the same proposition as the nominalized clause. The result is that the complement of the verb is an individual of type e, rather than a proposition of type 〈s,t〉. It can now combine with the transitive matrix verb via function application, just like any other individual-denoting DP would.Footnote 31 The truth conditions for (77) are given in (78).

-

(78)

In parallel, examples in which ‘know’ selects for a simple familiar DP work as follows. Consider again the example in (79), repeated from (35):

-

(79)

For an example such as (79), the theme of the matrix verb ‘know’ is not the unique, familiar content of a proposition, but rather some salient man in the discourse that is mapped to by the index ‘2’:

-

(80)

Adopting this analysis for clausal nominalizations unifies both the structure and interpretation of simple familiar definites as in (81) as well as the nominalized complements of presuppositional verbs, as in (82) (see also Hanink 2021).

-

(81)

-

(82)

5.3 Presuppositionality and factivity

At this point we return to the notion of factivity as generally described in the literature. In our analysis, idx is only present in nominalized clauses, and so the presence or absence of D can explain the presence or absence of presupositionality, and furthermore unifies the other uses of anaphoric/familiar DPs such as demonstratives. However, factivity does not reduce to mere familiarity alone: factivity as we typically know it presupposes the truth of the complement. But there are many individuals, familiar or not, whose propositional content is not a fact—rumors, for instance. We consider two established options for encoding factivity in the structure proposed above, and discuss problems for each of these options.

5.3.1 Factivity is not just familiarity

In effect, Kastner (2015) assimilates factivity to familiarity: factive complements are familiar, and their truth is presupposed. His account however does not derive this directly, as there is nothing in the semantics of D that enforces this latter characteristic. We could in principle stipulate a presupposition that x is a fact in the definition of D (or of C; Kratzer 2006), or through a silent head fact (Elbourne 2013), but in addition to being an ad hoc fix, it is not clear that we want such a presupposition generally associated with clausal nominalizations or with D more generally.

Recall that clausal nominalizations in Washo also form internally headed relatives (83), as well as so-called perception readings (84):

-

(83)

-

(84)

The above clausal nominalizations also make use of a DP-layer, but we do not necessarily want to build factivity into their meaning. Instead, the referents that these nominalizations pick out (i.e., individuals or events) are simply familiar to interlocuters in a given context. That is to say, a semantics invoking familiarity is not limited to simple DPs and the complements of presuppositional verbs alone.

For instance, Hanink (2018, 2021) argues that the function of -gi/-ge in clausal nominalizations giving rise to perception/events readings such as those in (84) is likewise to pick out a referent in the immediate context through the introduction of idx into the structure of the DP. Building on Toosarvandani’s (2014) proposal for event nominalizations in Northern Paiute similar to the kind in (84), Hanink argues that the role of idx in the perception reading is to map the index it introduces to a familiar event through the assignment function. The role of the D layer is therefore to ι-bind the event variable introduced by the verb, returning an individual meaning for the whole DP. As proposed by Toosarvandani, the key to achieving this meaning is to leave the event variable in the proposition denoted by the vP unbound, as in (85), with the crucial result that existential closure of the event variable does not take place.

Consider the example in (84b) as derived in (85). First, the event variable in the meaning of the embedded clause does not undergo existential closure, preserving the meaning of a property of events. Second (and again assuming events and individuals to be of like types), this property undergoes Predicate Modification with [[idx]], which denotes the property of being anaphoric/familiar, just as it does in the clausal complements of presuppositional verbs, as well as in simple familiar DPs in e.g., Schwarz’s (2009) analysis of German and Hanink’s (2021) analysis of Washo demonstratives. Finally, D ι-binds this property, with a resulting meaning of a unique singing event that is equivalent to a familiar event in the context. Crucially, no reference to factivity is required for familiarity to be achieved.

-

(85)

Hanink (2021) further argues that index-encoding idx is required in internally headed relatives in order to derive the correct meaning of an individual (rather than a proposition), though for reasons of space we do not discuss this construction in any detail here.Footnote 32 Crucially however, we argue that the clausal complements of presuppositional verbs are just like event nominalizations of this kind, in that both pick out an individual via an assignment function. In the case of the former, the index picks out a familiar event. In the case of the latter, it picks out a familiar individual whose content is described by some proposition.

5.3.2 Factivity is not lexically specified

Kastner (2015) has it moreover that factivity may be lexically specified. Given that, in our analysis, presuppositional verbs in Washo already differ in their argument structure from non-presuppositional verbs, they could plausibly be special also in lexicalizing a factivity presupposition directly, just as the classical Hintikkan-style analysis would have it.

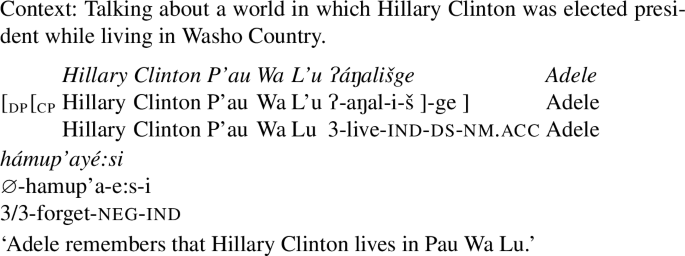

We do however find contexts where a proposition that is false in the actual world can appear as the nominalized complement of a presuppositional verb, such as those in (86)–(87).

-

(86)

-

(87)

To be sure, these contexts involve make-believe, where a speaker’s beliefs about the actual world are suspended to make room for what is happening in the make-believe world. Perhaps then we could keep a factivity presupposition in the lexical semantics of the verb, but tied to the evaluation world, which may not necessarily be the actual world. Converging evidence to reject this approach comes however for example from recent work on Korean (Bogal-Allbritten and Moulton 2017), which shows that the familiarity presupposed in nominalized clauses may be just that—familiarity—and not factivity.

Furthermore, if we build factivity directly into certain attitude predicates, then we have to assume that they are ambiguous between a factive and non-factive meaning. That is, while we might want to encode a presupposition of truth to the meaning of ‘see’ in (88), we surely do not want this presupposition to be encoded in the meaning of the same verb in (89).

-

(88)

-

(89)

Given that the complements of such verbs are always DPs, we can maintain a unified denotation for verbs such as ‘see’ or ‘know’ if we do not build a factive presupposition to their meaning in cases in which it is not warranted, as in (89), but rather appeal to the familiarity introduced by both DP complements.

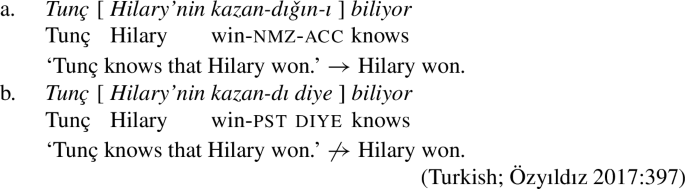

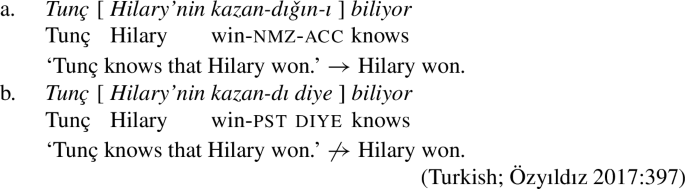

Consider a similar argument for Turkish made by Özyıldız (2017), who shows that the same predicate can give rise to both a factive and non-factive interpretation, depending on the shape of the clause it embeds. As in Washo, a nominalized embedded clause results in a presuppositional (factive) interpretation, which is absent with a non-nominalized clause.

-

(90)

Based on the fact that the same attitude predicate can give rise to different truth conditions, Özyıldız argues that factivity cannot be tied to the verb, but is instead better understood as the result of the entire composition of the predicate with the clause it embeds (see also Schulz 2003). A similar conclusion is drawn by Bondarenko (2019, 2020), who analyzes a factivity alternation in Buryat (Mongolic). In this language as well, a nominalized complement of the verb hanaxa yields a presuppositional interpretation ‘remember,’ while a CP complement yields a non-presuppositional interpretation ‘think.’ Thus, we find converging cross-linguistic evidence that nominalized complements correspond with presuppositional interpretations of attitude reports (with Washo differing in that attitude predicates themselves do not show selectional flexibility).

5.3.3 Deriving default factivity

In sum, our analysis for presuppositional complements uses the same ingredients that are independently motivated in the language for other types of clausal complements like relative clauses and event nominalizations. The only difference between a presuppositional complement and the other types of nominalizations is that the former additionally includes the F\(_{\text{\textsc{prop}}}\) type shift, in order for the resulting individual DP to refer to the content of the proposition, rather than to the proposition itself. While this analysis elegantly accounts for the morphological similarity of these constructions in Washo, it does not directly derive factivity, which is typically encoded as a presupposition of the matrix verb under traditional accounts of propositional attitudes. However, given examples like (86)–(87), as well as recent developments in the analysis of other languages that behave similarly (e.g., Korean, Turkish, Buryat), we believe this to be the correct result.

A complete account of how the apparent flavor of factivity arises—in Washo and cross-linguistically—is beyond the scope of this paper. We offer here a couple of suggestions for how future work might proceed on this question. For instance, Schlenker (2021) proposes a default presupposition projection algorithm for factive verbs and other presupposition triggers. His main motivation is that classical lexicalist theories of presupposition run into problems in cases where a presupposition trigger does not uniformly trigger the relevant presupposition (for instance, like our (86) and (87) above), and in cases where a presupposition projects in the absence of a lexical trigger (e.g., in the case of certain gestures). We refer the reader to Schlenker’s paper for the details, but the upshot of the proposal is that presuppositions need not be lexicalized in particular expressions, but rather arise as a result of the way that the entailments of certain expressions interact with the context (either the context of utterance or the local linguistic context). Such a view fits in nicely within the broader research program of taking a compositional rather than lexical approach to attitude ascriptions, which we follow in this paper.

Another possibility, suggested by a reviewer, is that presuppositional verbs in Washo have a “fact” argument, which can be saturated by a nominalized clause. This may be an interesting avenue to pursue. In this connection, though, we note that Washo does not seem to have a noun corresponding to English ‘fact’ (cf. Kastner 2015).

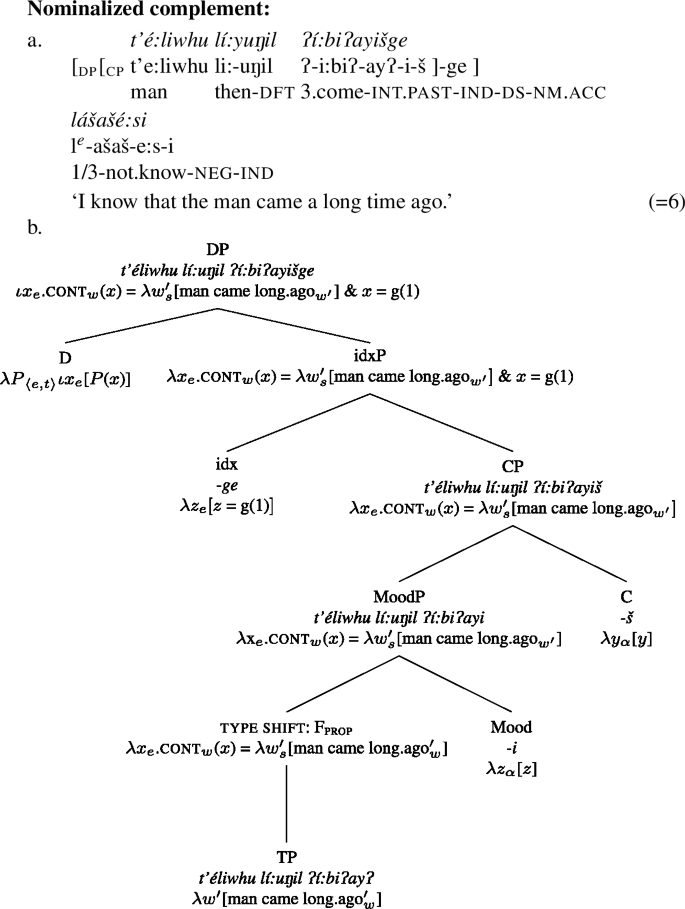

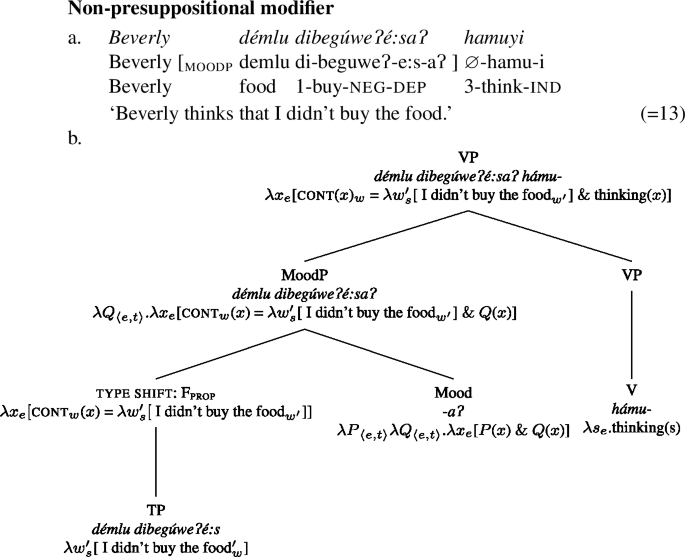

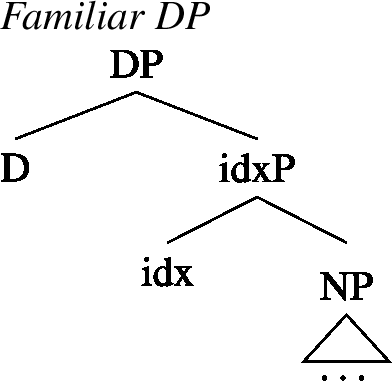

5.4 Non-presuppositional modifiers

We now turn to instances of clausal embedding by non-presuppositional verbs. Structurally speaking, clauses embedded by non-presuppositional verbs in Washo lack a nominalizing DP-layer (as well as a CP-layer, but this does not play a role in our account). Given that the function of the nominalizing D head is to transform properties into individuals, it then follows that the absence of D in non-presuppositional clauses means that these clauses denote properties.

Following our analysis of embedded clauses in the previous section, we apply the F\(_{\text{\textsc{prop}}}\) type shift at the TP level, transforming a proposition into a property of individuals. This property then combines with the dependent mood marker -aʔ. Given the conjunction semantics we proposed for -aʔ in (75), the result is a function from properties of individuals to properties of individuals. Assuming that events and individuals are both type of type e (as introduced in Sect. 4.1), this meaning can combine directly with the matrix verb it modifies via Function Application. The composition of non-presuppositional clauses thus proceeds as in (91).Footnote 33

-

(91)

After adding in the attitude holder argument and existentially closing the matrix event variable, we arrive at the truth conditions in (92). The content of the attitude is equated with the attitude event itself via the conjunction semantics of the dependent mood.

-

(92)

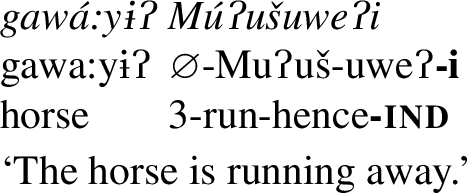

Our semantics for clausal modification predicts that these clauses should not stack recursively: F\(_{\text{\textsc{prop}}}\) is defined in terms of equality, and so the stacking of “contents” of multiple propositions should result in contradiction (see also Moulton 2009:29; Elliott 2016:183–184). This prediction appears to be correct for Washo: instead of stacking bare -aʔ-clauses in the relevant contexts, speakers provide an adjunct instead that indicates temporal simultaneity (more on this in Sect. 5.5). Note that the switch reference marker -š is present on the most deeply embedded verb ‘run away’ in (93), which indicates that this clause is a full CP rather than a MoodP modifier (as discussed in Sect. 3.2.1). We note that it is a descriptive fact about Washo that clauses headed by the dependent marker -aʔ cannot be coordinated, though we do not address the syntax of coordination here.

-

(93)

5.5 The mood marker difference generalized

We now step back and discuss how the semantics for the mood markers -i and -aʔ that we proposed in Sect. 5.1 can be leveraged to account for their distribution beyond clauses embedded by presuppositional and non-presuppositional verbs. In particular, the dependent mood -aʔ appears in several types of adjunct clauses, and we sketch how our account can be extended to those cases.

Recall that for the independent mood -i, we propose that it denotes the identity function, i.e., it is semantically vacuous. For presuppositional complements, it simply passes up the meaning of an F\(_{\text{\textsc{prop}}}\)-type-shifted TP, which later combines with the idx head -ge and then D; see (77). A similar situation obtains in the case of internally-headed relative clauses and event nominalizations, modulo the absence of F\(_{\text{\textsc{prop}}}\); see e.g., (83a–83b) and (84a–84b), respectively. Recall as well that outside of complement and relative clauses, the independent mood -i occurs as a default mood marker in matrix clauses, as in (94). This fact makes sense in view of our proposal that -i introduces no semantic content.

-

(94)

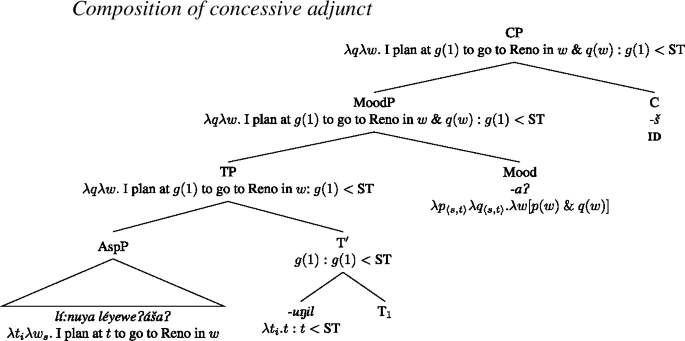

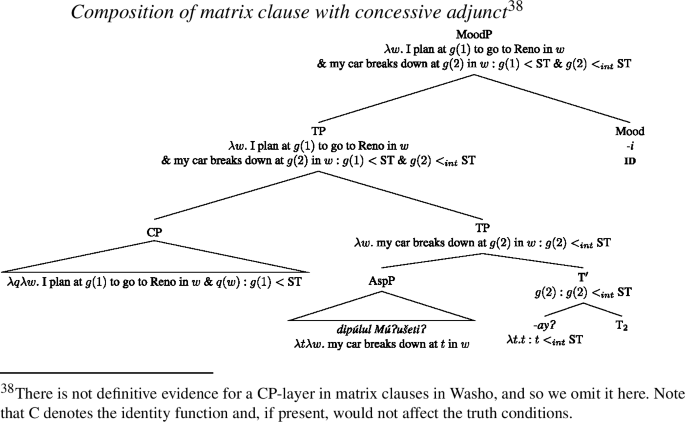

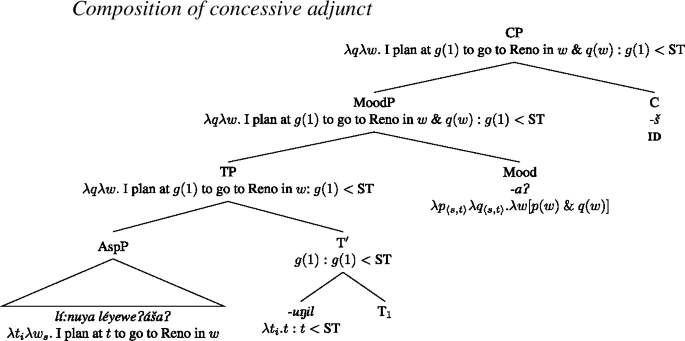

This meaning for the independent mood stands in contrast to the dependent mood marker -aʔ, which we have proposed denotes conjunction of properties. This semantics immediately explains why dependent -aʔ doesn’t occur in matrix clauses: the application of -aʔ to a clause does not deliver a propositional type. Given that modification generally involves a conjunctive semantics (Heim and Kratzer 1998), we can understand why the dependent -aʔ occurs in many types of adjunct clauses. In particular, two types of adjunct clauses that we focus on here are (i) “concessive” or “contrastive” adjunct clauses, exemplified in (95); and (ii) temporal adjunct clauses, where the -aʔ-clause receives a “simultaneous” interpretation (often translated by speakers as ‘when’ or ‘while’ in English), exemplified in (96). As we already noted in Sect. 3.2.1, unlike -aʔ-marked clauses embedded by non-presuppositional verbs, both types of adjunct clauses exhibit switch reference morphology when the subjects of both clauses are different, telling us that these adjunct clauses are full CPs.

-

(95)

-

(96)

Let us first consider in more detail the concessive adjunct clauses like in (95). The main clause contains the independent mood -i, while the adjunct clause contains the dependent mood -aʔ, as well as switch reference morphology. As (95) also shows, both clauses contain their own tense (-uŋil ‘past’) and aspect (-ašaʔ ‘prospective’) layers.

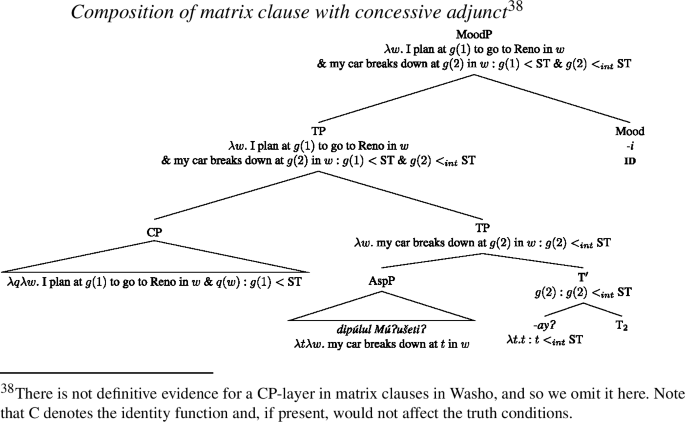

We propose that concessive adjunct clauses adjoin high in the main clause structure, at TP. At this height in the structure, the main clause denotes a proposition. Given our analysis of the semantics of -aʔ as generalized conjunction, the adjunct clause itself should also denote a proposition. This is of course plausible since the adjunct clause also contains its own tense. These two propositions are conjoined by the version of -aʔ in (97).

-

(97)

Our full analysis of the sentence in (95) is given below in (98) and (99). Unlike attitude complement clauses, we do not posit an instance of the F\(_{\text{\textsc{prop}}}\) type shift in this case: these clauses do not make reference to an object with propositional content, and no type shift is necessary for the composition. To facilitate a comparison with simultaneous temporal adjunct clauses below, we fully spell out our assumptions about tense here. Following Bochnak (2016), we assume that tenses modify a reference time pronoun located in T. Like other free variables, the reference time pronoun receives its value from the assignment function g. It saturates the temporal argument of AspP, returning a proposition. The general past marker -uŋil restricts the value of the temporal pronoun to a time prior to the speech time; the intermediate past -ayʔ restricts this value to a time in the intermediate past of the speech time.

-

(98)

-

(99)

We note that our semantics on its own does not derive an interpretation of “concession.” We tentatively propose that such an interpretation comes about pragmatically, plausibly due to the incompatibility of the content of both clauses holding simultaneously (i.e., I go to Reno vs. my car breaks down).

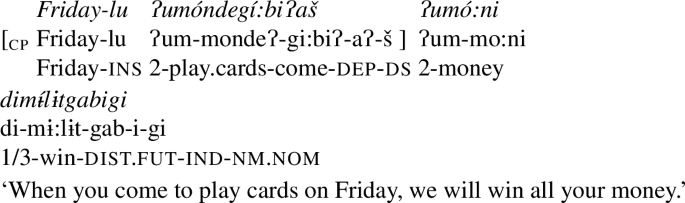

Turning now to simultaneous temporal adjuncts, we observe that these adjunct clauses do not and cannot contain their own tense. This is true whether the main clause contains a past or future tense, as shown in (100) and (101).

-

(100)

-

(101)

We propose that simultaneous adjunct clauses attach to AspP in the main clause. Since AspP denotes a predicate of times (e.g., Kratzer 1998), the dependent marker -aʔ thus conjoins predicates of times for this type of adjunct clause, as in (102). This means that the material that -aʔ embeds also denotes a predicate of times. We propose that in this case, the Mood head -aʔ directly embeds an AspP, which has two welcome consequences. First, we get the correct semantic type (i.e., -aʔ conjoins two predicates of times), and second, this explains why simultaneous adjunct clauses cannot host a tense morpheme.Footnote 34 We get temporal simultaneity from the fact that the temporal variable from the main clause will be filled in for the temporal argument of both clauses after they are conjoined. Just as with concessive adjunct clauses, we do not posit an instance of the F\(_{\text{\textsc{prop}}}\) type shift for simultaneous adjunct clauses.

-

(102)

-

(103)

Note that this analysis predicts that such clauses may stack (without an overt coordinator, cf. the discussion of MoodP stacking above in Sect. 5.4). We also predict this in the case of simultaneous adjuncts, given that the meaning of the dependent mood morpheme should allow for recursion. This prediction is borne out, as exemplified in (104):

-

(104)

We note that our analysis also makes predictions about the same type of Condition C effects discussed for MoodP adjuncts to non-presuppositional verbs in Sect. 3.2.2. In that section, we offered evidence from Condition C that these adjuncts are base-generated low, below the matrix subject. Given our proposals above for the height of attachment of concessive and simultaneous adjuncts (at different heights, but both higher than the base position of the main clause subject), we predict that a Condition C violation should not be incurred in cases where an R-expression in these adjunct types precedes a co-indexed pronoun in the main clause. At the moment, we do not have the relevant data to test these predictions. (See Arregi and Hanink 2021 for tentative results involving simultaneous adjuncts that in fact runs counter to our claims here; Condition C effects in Washo are however far from understood and research is ongoing.) Nothing crucial to the core of our proposal hinges on this, however. The main take away point is that the dependent Mood marker -aʔ has the general meaning of conjunction, regardless of the attachment site of the -aʔ-marked clause.

To sum up, our analysis of the dependent mood marker -aʔ as denoting generalized conjunction can help shed light on why this marker can be used in certain complement clauses and adjunct clauses. Note that for the adjunct clauses, we do not include the relations of contrast or simultaneity anywhere in the semantics directly. We believe this is a good thing, since it can account for the wide range of uses of -aʔ-marked clauses. We suggest that the more specific interpretations come about pragmatically, though we do not propose a full analysis here.Footnote 35 Building these meanings into -aʔ directly would not explain why these meanings are not present in -aʔ-marked clauses embedded by non-presuppositional verbs. The generalized conjunction semantics of the dependent mood may also help to explain why -aʔ-marked clauses appear with a fairly high frequency in narratives: -aʔ-marking just denotes conjunction (albeit with a subordination syntax), but has a variety of pragmatic functions, expressing various discourse relations. While we leave a full analysis of all the functions of -aʔ-marking in Washo to future research, we believe our analysis already goes a long way to account for many of the uses of -aʔ-marked clauses in the language.

6 Conclusion

We have argued in this paper for a language-wide distinction between complementation and modification as two distinct modes of clausal embedding in Washo. This distinction is most clearly visible in the embedding strategies of two classes of verbs that are largely taken to differ according to presuppositionality: while presuppositional verbs directly select for DP complements in the form of clausal nominalizations, non-presuppositional verbs do not select but are instead modified by the (non-nominalized) clauses they embed. We have argued that this is explained by independent factors in the language, in a way that ties in neatly to the morphosyntactic shape of the embedded clause, selectional properties of attitude predicates, and the semantics of the independent and dependent mood markers in the language.

The emerging picture yields two important results contributed by the data from Washo. First, while it is in line with Kastner’s (2015) proposal that presuppositional verbs select for DPs, it challenges the view that non-presuppositional verbs select for embedded clauses directly: we argue instead that embedded clauses in this context are better understood as verbal modifiers. Second, the status of the MoodP in Washo as an adjunct to non-presuppositional verbs supports Elliott’s (2016) claim that attitude verbs are intransitive—but only in the case of this verb class—and is untenable for describing on the other hand the way in which presuppositional predicates embed clauses.

This picture has larger consequences for theories of clausal embedding across verb types. First, it is crucial that selection does play a role for some verbs, contra strong theories of clausal complementation (e.g., Kratzer 2006; Moulton 2009) where embedded clauses are not selected, and also contra Elliott (2016), for whom clausal embedding by verbs is always adjunction. The Washo evidence suggest that presuppositional verbs select for their complements both syntactically and semantically, while non-presuppositional verbs do not select in any way, but are simply good candidates for modification. Secondly, the behavior of clauses embedded by presuppositional verbs is not a product of factivity directly, though it is related through reference to familiarity. Other languages that make similar (though possibly slightly different) distinctions that support this state of affairs come from recent work on e.g., Korean, Turkish, and Buryat, suggesting wider-reaching implications from this work.

Notes

Washo is an SOV language with agglutinative verbal morphology. Uncited data come from fieldwork between 2015-2020 in two communites in California and Nevada, respectively.

Abbreviations: acc: accusative; adv: adverbial; attr: attributive; aud: auditory evidential; caus: causative; dep: dependent mood; dft: defunctive; dist: distal; dist.fut: distant future; ds: different subject; du: dual; in: intransitive; inch: inchoative; ind: independent mood; inst: instrumental; int.fut: intermediate future; int.past: intermediate past; near.fut: near future; nc: negative concord; neg: negation; nm: clausal nominalizer; nmlz: deverbal nominalizer; nom: nominative; obl: oblique; pl: plural; plupf: pluperfect; pro: pronoun; prog: progressive; prosp: prospective; q: question particle; rec.past: recent past; refl: reflexive; ss: same subject; tr: transitive; un: unexpressed object; vis: visual evidential. A prefixed number indicates verbal or possessor agreement. Transitive verbs have subject and object agreement prefixes, indicated as subj/obj.

Cattell (1978) also discusses a class of verbs called “response-stance” verbs, which include entries such as ‘agree’ and ‘accept.’ To our knowledge, Washo does not lexicalize any of the verbs in this class.

The difference in the form of the suffix is a reflex of a nominative/accusative case distinction. We return to this in Sect. 3.1.

Other members of this class include e.g., ‘not believe’ and ‘not know how (to do something).’

Due to normal phonology, the vowel is long and stressed only when gi/ge stands alone, i.e., in pronominal uses (Jacobsen 1964:309,312–313).

A reviewer asks whether this example is ambiguous between an internally-headed relative, a presuppositional attitude, and perception reading. This is in fact the case, given that all three clause types are morphosyntactically identical. In general, the readings are disambiguated by context, unlike in languages in which word order differentiates relative clauses (e.g., Diegueño, Basilico 1996).

A reviewer suggests testing such subjects with the predicates ‘a lie’ or ‘false.’ To our knowledge, this is not possible in Washo.