Abstract

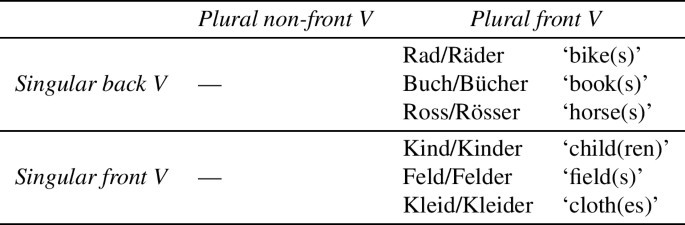

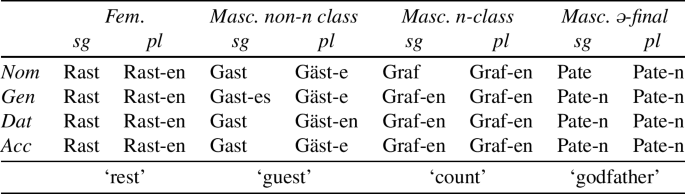

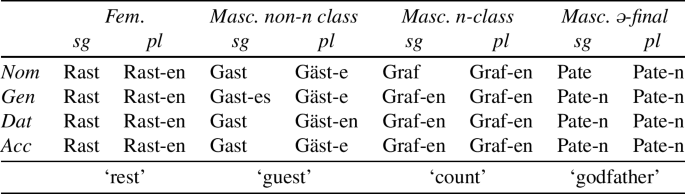

Plurals in the native stratum of German nouns exhibit a complex interlacing of arbitrary lexical classes and virtually exceptionless generalizations across them. Thus while it is not fully predictable phonologically or semantically which suffix allomorph a plural noun takes and whether it undergoes umlaut (vowel fronting), specific suffixes consistently trigger or block umlaut (Augst 1979; Wurzel 1998; Wunderlich 1999), and all plural forms obey a fixed prosodic template (Wiese 1996b, 2009). This combination of regular and irregular has given rise to the claim that German noun plurals defy a morpheme-based analysis and require global paradigm structure conditions (Bittner 1991; Wurzel 1998; Carstairs-McCarthy 2008) or construction-specific constraints (Neef 1998; Wunderlich 1999; Wiese 2009). In this paper, I present a new, purely concatenative analysis of German plurals combining and extending on elements of the classical autosegmental analyses for German umlaut (Yu 1992; Lieber 1992; Féry 1994) and schwa (Hall 1992; Noske 1993; Wiese 1996b) couched in Stratal OT (Kiparsky 2015; Bermúdez-Otero 2018) and Containment Theory (Prince and Smolensky 1993; Revithiadou 2007; van Oostendorp 2008). I show that assuming a general plural suffix consisting of a featurally underspecified segmental root node and a floating Coronal feature allows for a purely phonological explanation of both paradigmatic implications and the templatic shape of noun plurals, which have so far been treated as independent problems, and gives rise to a principled account of apparent exceptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

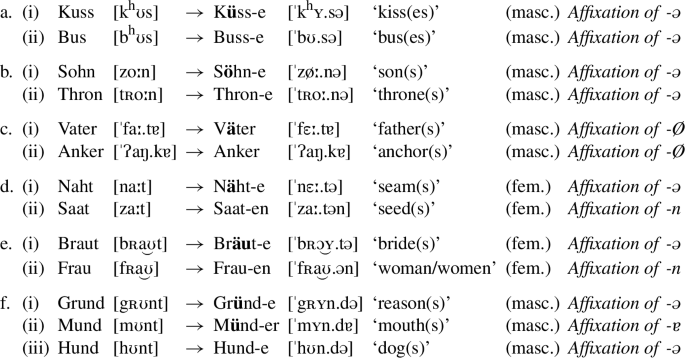

1.1 Wiese’s and Wunderlich’s dilemmas

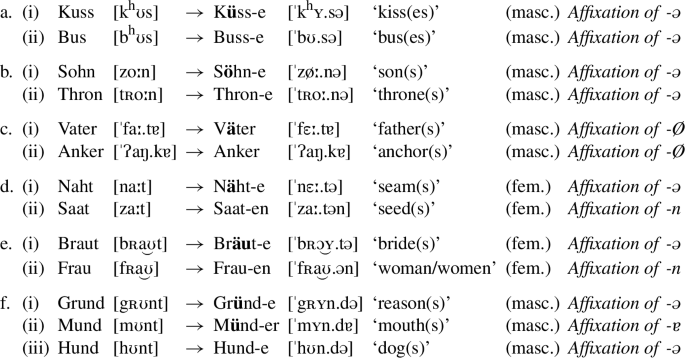

Plurals in the native stratum of German nouns exhibit a complex interlacing of phonologically unpredictable lexical classes and broad, virtually exceptionless generalizations across them. This analytic tension between predictability and idiosyncrasy emerges most clearly in the analyses of Richard Wiese and Dieter Wunderlich. Thus Wiese (1996b, 2009) observes that plurals in the native stratum of German instantiate a consistent prosodic template: Whereas singular nouns may end in any kind of syllable, virtually all plural nouns end in the sequence of a full-vowel syllable and a reduced syllable, headed either by schwa ([ə]), (1a), a-schwa ([ɐ]) (1b), or by a syllabic sonorant (1c-f).Footnote 1

While this generalization can be captured succinctly by assuming that the plural affix is a prosodic template in the sense of Prosodic Morphology (McCarthy and Prince 1993, 1996; Wiese 1996b, and Wiese 2009 for a constraint-based version of this intuition), this doesn’t account for the fact that the constant templatic shape of plurals is achieved by different affixation patterns, which are not completely predictable by phonological shape and/or gender, as shown by the quasi-minimal pairs in (2):

-

(2)

Unpredictability of segmental plural allomorphs

Since this allomorphy is not purely phonological, a considerable amount of it has to be stated independently of the template. But positing explicit allomorphy rules (like [+Plural] → -ɐ /  …, see e.g. Yang 2016) which derive the different patterns in (2) would render Wiese’s plural template a redundant statement of a generalization already following as an epiphenomenon of independent morphological rules.

…, see e.g. Yang 2016) which derive the different patterns in (2) would render Wiese’s plural template a redundant statement of a generalization already following as an epiphenomenon of independent morphological rules.

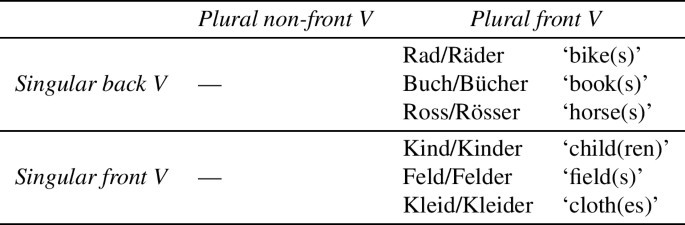

The second, closely related, analytic dilemma is rooted in the fact that German noun plurals differ across two logically independent dimensions (Wunderlich 1999)Footnote 2: the choice of a suffix allomorph, already illustrated in (1) and (2), and the presence vs. absence of umlaut, the phonological fronting of back and low vowels characteristic of many morphological processes in German.Footnote 3 As shown in (3), with more quasi-identical pairs, umlaut can appear or be absent with roots of basically the same phonological shape (and the same gender) independently of whether the segmental suffix is identical (3a,b,c) or not (3d,e,f):

-

(3)

Umlaut and plural allomorphs

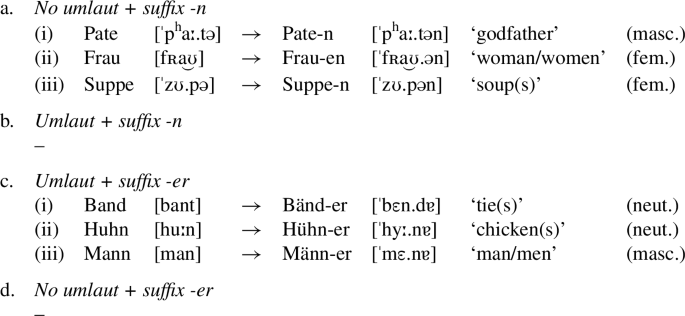

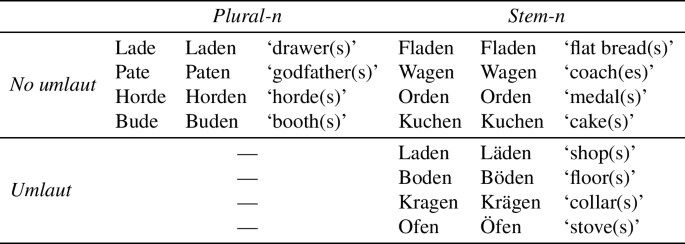

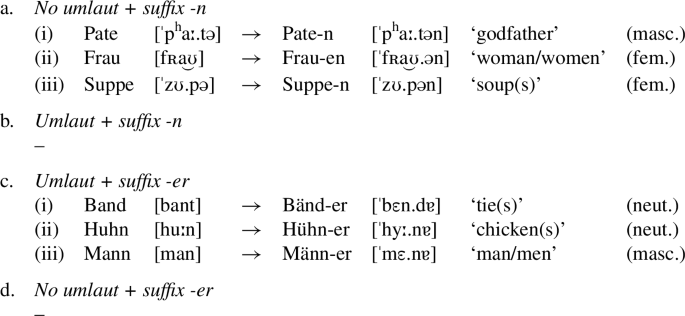

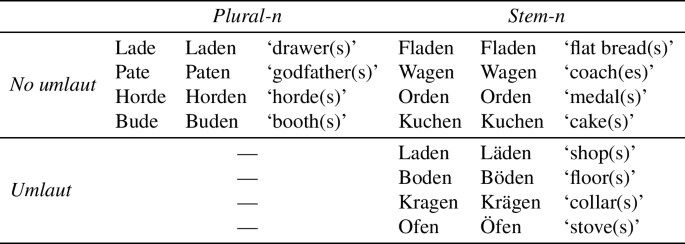

At the same time, there are highly reliable predictive correlations between the choice of suffix allomorph and the presence of umlaut. Whereas plurals in -e (-ə) and -Ø may co-occur with umlaut or not, depending on the specific lexeme, nouns with plural -n never umlaut (4a,b) and nouns with plural -er [-ɐ] virtually always umlaut (4c,d):

-

(4)

(Non-)co-occurrence of umlaut and segmental plural allomorphs

The attraction of umlaut by -er is highlighted by the existence of a handful of plural doublets, where nouns, one in -e, and one in -er have different plurals with slightly different semantic/pragmatic connotations (5). Strikingly these words don’t show umlaut if they form the plural in -e, but umlaut becomes obligatory in the -er forms.

-

(5)

(Non-)co-occurrence of umlaut and segmental plural allomorphs

Thus Wunderlich’s observations pose a similar dilemma as Wiese’s generalization: The general unpredictability of umlaut and plural allomorphy illustrated in (2) and (3) seems to require specifying theses choices lexically (e.g. by diacritic features or by listing) for every lexeme, but this wouldn’t capture the systematic nature of the generalizations in (4) and (5). In the following section, I will sketch the gist of my approach, which provides a unified account to both Wunderlich’s and Wiese’s generalizations, and solves the analytic double bind they face.

1.2 The proposal in a nutshell

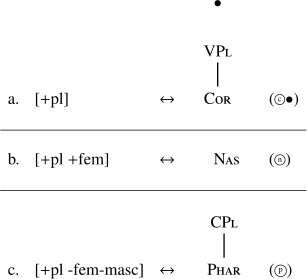

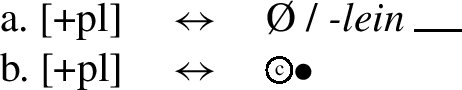

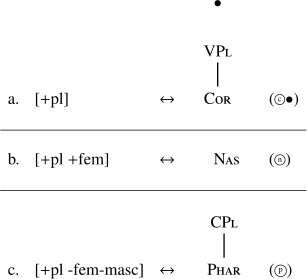

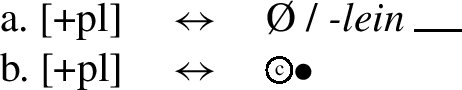

The proposal I develop here is to resolve Wunderlich’s and Wiese’s dilemmas by analyzing German plural morphology as the effect of concatenative affixation of ‘defective’ subsegmental material in the sense of Generalized Nonlinear Affixation (Bermúdez-Otero 2012), combining and elaborating on two independent assumptions from the pre-OT literature on German: that umlaut-triggering affixes contain a floating feature encoding frontness (Yu 1992; Lieber 1992; Féry 1994), and the representation of affixal [ə] via a defective segment-sized phonological unit (corresponding to the C- or X-slot of Wiese 1986; Hall 1992; Noske 1993). This accounts for the templatic shape of plurals since incomplete segments are less strictly protected by faithfulness constraints and hence give rise to phonological Emergence-of-the-Unmarked effects (shown in detail in Sect. 5), and allows us to systematically relate umlaut and segmental morphology under the assumption that the floating feature may either surface as vocalic fronting or as the place-of-articulation specification of coronal segments as predicted by Unified Feature Theory (Clements and Hume 1995) (see Sect. 3). That the templatic shape of plurals holds for all plurals (not only for -ə) is derived from the novel assumption that there is a single fully general plural affix, attaching to all plural nouns—consisting of an unspecified root node (written as “•”) and a floating Coronal feature (6a) (comprising a VPlace node in the feature geometry of Clements and Hume 1995) and two more restricted markers for feminine (6b) and neuter (6c) plurals that specify additional segmental features which may combine with the general plural affix in the appropriate contexts (I refer to the phonological shapes of these affixes by the abbreviations given in brackets such as ‘ •’):

•’):

-

(6)

Representations for German plural affixes

The substantial phonological underspecification of the plural marker in (6a) allows phonology to spell out the optimal shape of the feature-less segment, resulting in the default case in -e ([ə]) (7a), the maximally unmarked segment in German, but in -n if the base already ends in schwa (7b) since German doesn’t allow for sequences of adjacent schwas, a consequence of a more general ban against string-adjacent weak syllable nuclei ( ) in the language (see Neef 1998 and Sect. 5.1 for detailed discussion).

) in the language (see Neef 1998 and Sect. 5.1 for detailed discussion).

-

(7)

•-Allomorphy

However, in most forms, plural is realized morphologically by two of the affixes in (6), resulting in a classical case of multiple (extended) exponence. Thus from a phonological point of view, a feminine noun such as Welt [vεlt] ‘world’ could realize the plural segment as [ə] (as for masculine Schrot in (7a)), but morphology leads also to insertion of (6b) to spell out [+feminine]. After phonological optimization, the resulting segment -n realizes, both the segmental root node of (6a) and the floating nasal feature of (6b), as shown in (8a). Similarly for the neuter noun Feld [fεlt] ‘field’ the general plural affix associates to the pharyngeal feature of (6c) spelling out [+pl -fem -masc] to form a low central vowel (8b) (subscripts indicate associated affix features):

-

(8)

•+{

,

, }-Merging

}-Merging

The examples in (7) and (8) are slightly oversimplified in that they disregard the floating Coronal (+VPlace) feature which is an inherent part of (6-a). Floating Coronal is in fact phonologically suppressed in specific cases, but shows up either in the suffix as part of -n as shown in (9a) for Saat [za ːt] ∼ Saat-en [za ː.t ] ‘seed(s)’ (the full analysis that would also apply to Welt in (8a)) or as umlaut (vowel fronting) as in (9b) for Naht [na ːt] ∼ Näht-e [ˈnεː.tə] ‘seam(s)’ under the standard assumption that front vowels are characterized by the feature Coronal (Hume 1994; Clements and Hume 1995; Lahiri and Evers 1991).

] ‘seed(s)’ (the full analysis that would also apply to Welt in (8a)) or as umlaut (vowel fronting) as in (9b) for Naht [na ːt] ∼ Näht-e [ˈnεː.tə] ‘seam(s)’ under the standard assumption that front vowels are characterized by the feature Coronal (Hume 1994; Clements and Hume 1995; Lahiri and Evers 1991).

-

(9)

-Allomorphy

-Allomorphy

The theoretical importance of these data is in revealing that ‘floating’ features are not simply a notational alternative to procedural morphophonological rules for encoding non-segmental changes in stems. The floating exponents of German plurals also show up as part of what is traditionally seen as the suffix, they combine with other floating exponents, and alternate between stem-internal and suffixal morphology. This combinatorial freedom and contextual variability is expected if the primitives of plural exponence are autosegmental pieces of phonological structure, but cannot be captured if processes such as umlaut are implemented as the result of morphophonological rules (Janda 1982; Anderson 1992), readjustment rules (Embick and Halle 2005), or morphophonological constraints (Neef 1998; Alderete 2001; Xu and Aronoff 2011).

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. In Sect. 2, I lay out background assumptions on the architecture of Optimality Theory, adopting the Stratal Autosegmental Containment approach, and on the featural representation of German segments. The core of the subsegmental analysis is developed in detail and shown to derive central implications between suffix choice and umlaut in Sect. 3. Sect. 4 extends the analysis to phonologically predictable cases of suffix allomorphy, and provides arguments that German plurals instantiate crucial instances of phonological opacity which cannot be covered in an account relying only on surface constraints, but follow naturally in Stratal Containment. Wiese’s generalization on the templatic shape of noun plurals is derived in Sect. 5, and Sect. 6 shows that nouns taking exceptional plural allomorphs are also best captured in a subsegmental analysis by positing floating root features. Previous theoretical work on German plurals is critically discussed in Sect. 7. Finally, Sect. 8 contains a short summary of the paper.

2 Background assumptions

The Generalized Nonlinear Affixation approach (GNA, Bermúdez-Otero 2012; Bye and Svenonius 2012; Zimmermann 2017; Paschen 2018) to which I contribute here is a research program which generalizes the tradition of Autosegmental Phonology (Goldsmith 1976; McCarthy 1979; Marantz 1982) and Prosodic Morphology (McCarthy and Prince 1996), where tonal and templatic exponence is interpreted as affixation of partially specified phonological material (e.g. floating tones or timing slots without segmental melodies) to all productive cases of nonconcatenative morphology in line with the concatenativist hypothesis in (10):

-

(10)

The Concatenativist Hypothesis:

Morphology = Concatenation + Phonological alternations

Recent work in the GNA approach has shown that even cases of nonconcatenative morphology that seem to be inherently procedural, such as morphologically triggered shortening, segment deletion and polarity receive a natural analysis in this general framework (Bye and Svenonius 2012; Zimmermann 2013; Trommer and Zimmermann 2014; Trommer 2014, 2015; Zimmermann 2017). German plurals have been taken as a different type of challenge to the Concatenativist Hypothesis. An affixational analysis has been argued to be incapable to capture submorphemic generalizations (Köpcke 1988; Neef 1998) such as the triggering of umlaut by -er-suffixes as well as the prosodic consistency in German plurals (Wiese 2009). In the following sections, I will show that a strict GNA approach not only solves these problems, but also provides deeper phonological explanations for these generalizations and captures them in a more natural way than approaches employing morphophonological constraints requiring spellout for specific features (Hammond 1995; Russel 1995; Klein 2000; MacBride 2004; Xu and Aronoff 2011) or paradigmatic distinctness (Neef 1998; Kurisu 2001; Carstairs-McCarthy 2008) (see Sect. 4 for detailed discussion).

This points to a final important aspect of the Nonlinear Affixation approach: The heuristic value of the GNA program and the Concatenativist Hypothesis—to closely link nonconcatenative morphology and productive phonological alternations—stands and falls with its coupling to a strong version of the Indirect Reference Hypothesis (Nespor and Vogel 1986; Selkirk 1986; Inkelas and Zec 1995), which disallows direct reference to morphosyntactic information in phonological rules and constraints. Morphologically sensitive constraints as in indexed-constraint approaches (Pater 2000, 2007) or its rough equivalent, the assumption of different cophonologies for specific morphological constructions (Orgun 1996; Inkelas and Zoll 2005; Inkelas 2014), substantially undermine the empirical content of the Concatenativist Hypothesis since they allow phonology to perform most of the operations usually assumed in approaches to morphology employing spellout constraints or rules (Anderson 1992; Xu and Aronoff 2011; Staubs 2011) in a morphologically distinctive way (see Bermúdez-Otero 2012 for discussion).

In the following, I will therefore assume that the possible effects of morphosyntactic information on phonological computation is minimal. It is restricted to the notion of morphological color in Autosegmental Colored Containment Theory, and to the stratal architecture of word-internal morphophonology, which I will discuss in the following two sections.

2.1 Autosegmental Colored Containment Theory

Autosegmental Colored Containment Theory (Zimmermann 2014, 2017; Trommer 2011, 2015; Zaleska 2018; Paschen 2018) is an implementation of the restrictive original version of Optimality Theory proposed in Prince and Smolensky (1993) in that it adopts hierarchical autosegmental representations and the Containment requirement on candidate generation. In a nutshell, containment-based systems retain unpronounced phonological structure as floating material in the output of phonological computation—a possibility coming for free in any formalism adopting hierarchical autosegmental and prosodic representations—allowing direct comparison between inputs and outputs and thus obviating the overly powerful coindexing mechanism of Correspondence Theory for implementing faithfulness constraints (Walther 2001). The version adopted here slightly departs from the Prince and Smolensky version of Containment by adopting the representation of epenthesis through morphological colors from Colored Containment Theory (van Oostendorp 2006; Revithiadou 2007), and by generalizing the Containment assumption to association lines (‘Radical Containment’).

Morphological colors: Following van Oostendorp (2006) and Revithiadou (2007), I assume that morphological structure is minimally reflected in phonological representations by coloring. At the interface of morphology and phonology, every morpheme M of an underlying representation is assigned a unique color which is inherited to all nodes and association lines that are part of M. Colors have two consequences for phonological computation. First, they allow us to detect whether two phonological elements belong to different morphemes, providing a general autosegmental notion of morpheme boundary. This aspect of the theory, although crucial to foundational results of Colored Containment Theory (see e.g. van Oostendorp 2007), will not be relevant for the German data discussed here. Second, colors allow us to distinguish underlying (‘colored’) material from epenthetic material: Epenthetic material is colorless, and by the Containment Assumption GEN doesn’t license the change or removal of the color of underlying material.

Possible operations of GEN: By the Radical Containment Assumption, phonological material can never be literally removed from phonological input representations in the course of phonological computation (Prince and Smolensky 1993; van Oostendorp 2008:1365). The candidate-generating function GEN is thus restricted to the following changes it may perform on underlying forms (phonetic visibility is conceived as an elementary attribute of association lines, but not of phonological nodes):

-

(11)

Possible operations of GEN:

-

a.

Insert epenthetic nodes (prosodic nodes, feature nodes, segmental root nodes) or phonetically visible association lines between nodes

-

b.

Mark a colored association line as phonetically invisible

-

a.

(11a) implements the slightly implicit assumptions held on Containment and GEN in the earliest version of Optimality Theory (Prince and Smolensky 1993), whereas (11b) replaces deletion of association lines by a less invasive operation: marking for phonetic invisibility (indicated in the following by dotting). (12) shows different candidates generated by this version of GEN for the input (12a) two vowels (with underlyingly associated moras), and some plausible repairs of the resulting hiatus (see Casali 1996, 1997, for a detailed containment-based analysis) where epenthetic/colorless nodes are marked by grey background shading and epenthetic association lines by dashing (- - -). In (12b) a single association line is inserted, generating a diphthong ([au]), in (12c) additional syllable and foot nodes are added and associated, and in (12d) an additional glottal stop:

-

(12)

Deletion as Phonetic (Non-)pronunciation: (Non-)pronunciation of underlying material is implemented as phonetic non-interpretation of phonological material following the axiom in (13):

-

(13)

Axiom of phonetic realization

A phonological node is phonetically realized iff it is dominated by the highest prosodic node of the candidate through a path of phonetically visible association lines

Thus in (12b,c,d) all underlying material is pronounced since it is dominated through (underlying or epenthetic) phonetic association lines by the highest prosodic node (a  -node in (12b), and a foot node in (12c,d)). (14) shows candidates produced by GEN leading to partial non-pronunciation. In (14b), the association line between the syllable and its mora is marked as non-phonetic by dotting (…), thus neither the mora nor the vowel [a] below it are pronounced. Crucially, (14a) (the output candidate identical to the input) also leads to partial non-pronunciation even though all input structure is preserved in the phonological output. [u] and its mora are not dominated by the highest P-node (the syllable), and hence invisible for phonetic spellout. (14c,d) are two more complex candidates with compensatory lengthening, where one of the vowels is unpronounced since the association line connecting it to a mora is rendered invisible, but the mora itself is fully integrated via epenthetic association lines, and hence pronounced as additional length:

-node in (12b), and a foot node in (12c,d)). (14) shows candidates produced by GEN leading to partial non-pronunciation. In (14b), the association line between the syllable and its mora is marked as non-phonetic by dotting (…), thus neither the mora nor the vowel [a] below it are pronounced. Crucially, (14a) (the output candidate identical to the input) also leads to partial non-pronunciation even though all input structure is preserved in the phonological output. [u] and its mora are not dominated by the highest P-node (the syllable), and hence invisible for phonetic spellout. (14c,d) are two more complex candidates with compensatory lengthening, where one of the vowels is unpronounced since the association line connecting it to a mora is rendered invisible, but the mora itself is fully integrated via epenthetic association lines, and hence pronounced as additional length:

-

(14)

Since ‘deletion’ in Autosegmental Containment is roughly equivalent to a generalized notion of ‘floating,’ I will also use the classical circle notation for indicating phonetic non-realization (e.g.  for the second vowel in (14b)). For convenience, I will abbreviate the term ‘phonetically realized’ in the following simply by ‘phonetic’ and will call colored (i.e., underlying) phonological material ‘morphological’ since it is interpreted by morphology as part of specific morphemes.

for the second vowel in (14b)). For convenience, I will abbreviate the term ‘phonetically realized’ in the following simply by ‘phonetic’ and will call colored (i.e., underlying) phonological material ‘morphological’ since it is interpreted by morphology as part of specific morphemes.

Markedness constraints and the Cloning Hypothesis: Following Trommer (2011), I assume that containment-based markedness constraints are restricted by the hypothesis in (15) which limits sensitivity to underlying material to generalized constraints (‘clones’) mimicking independently motivated markedness constraints on surface representations:

-

(15)

The Cloning Hypothesis:

Every markedness constraint has two incarnations, a phonetic and a general clone: The general clone refers to complete phonological representations. The phonetic clone refers to the phonetically realized substructure of phonological representations.

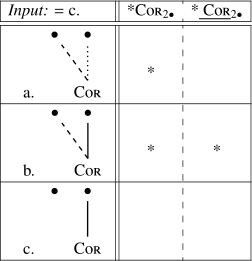

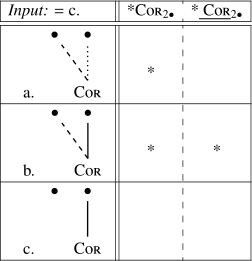

Phonetic clones are standard markedness constraints on phonetic output representations, whereas general clones evaluate input and output representations together (i.e., the combination of all input and output structure). Whereas these constraints are structurally identical, they refer to different sub-representations of candidates (or more exactly of input-candidate mappings), but can be ranked independently in individual grammars (see McCarthy 1996, 2003; Ettlinger 2008 for related approaches in Correspondence Theory). Phonetic clones are marked by underlining, while general clones are not graphically marked. Consider as an example the constraint against double linking of Coronal features which will play a crucial role in the analysis of umlaut below. Both the generalized (*Cor\(_{\mbox{2$\bullet$}}\)) and the phonetic clone of this constraint  penalize a Coronal feature which is linked morphologically to a single segment (16c) and spreads phonetically to another segment, resulting in surface double linking (16b) (e.g. /o …y\(_{\mbox{Cor}}\)/ ⇒ [ø\(_{\mbox{Cor}}\) …y\(_{\mbox{Cor}}\)]). While shifting of the Coronal feature as in (16a) (i.e., spreading and concomitant overt deassociation from its original node (e.g. /o …y\(_{\mbox{Cor}}\)/ ⇒ [ø

penalize a Coronal feature which is linked morphologically to a single segment (16c) and spreads phonetically to another segment, resulting in surface double linking (16b) (e.g. /o …y\(_{\mbox{Cor}}\)/ ⇒ [ø\(_{\mbox{Cor}}\) …y\(_{\mbox{Cor}}\)]). While shifting of the Coronal feature as in (16a) (i.e., spreading and concomitant overt deassociation from its original node (e.g. /o …y\(_{\mbox{Cor}}\)/ ⇒ [ø …u)]) obviously doesn’t violate

…u)]) obviously doesn’t violate  (Coronal is phonetically linked to only one segment), it still violates the generalized markedness constraint *Cor\(_{\mbox{2$\bullet$}}\) since the overall representation contains both phonetically visible and invisible association lines (16a):

(Coronal is phonetically linked to only one segment), it still violates the generalized markedness constraint *Cor\(_{\mbox{2$\bullet$}}\) since the overall representation contains both phonetically visible and invisible association lines (16a):

-

(16)

Phonetic vs. generalized markedness constraints

Note that generalized constraints cannot fully replace phonetic versions of specific constraints. Thus the ban on front round vowels in a language such as English which disallows them (see also Sect. 4.3 for minor effects on German plurals) must be the phonetic clone of the constraint,  . The general clone

. The general clone  would not be satisfied by changing an underlying /y/ resulting in surface [i] or [u]. Due to Containment, the resulting sound would still have the underlying Cor and Lab specifications accessible to the generalized clone.

would not be satisfied by changing an underlying /y/ resulting in surface [i] or [u]. Due to Containment, the resulting sound would still have the underlying Cor and Lab specifications accessible to the generalized clone.

2.2 Stratal organization

In line with the classical theoretical work on German morphophonology (Wiese 1988, 1996b; Giegerich 1987; Hall 1992), I assume that the lexical morphophonology of German is organized in different strata, accounting both for morphological and phonological differences. In particular, I will assume the version of Stratal Optimality Theory (Kiparsky 2000, 2015; Bermúdez-Otero 2018, to appear) laid out in Trommer (2011) which comprises three lexical strata, ① the Root Level (optimizing roots and stem-level affixes before their concatenation), ② the Stem Level (evaluating combinations of stem-level affixes and roots, but also word-level affixes before concatenation), and ③ the Word Level evaluating complete words.

I assume that the native layer of plural formation that I analyze in this paper, is located at the Stem Level, whereas the s-plural productive in borrowings (such as Kid ∼ Kid-s ‘children’) and stems with non-standard phonotactics (e.g. the few noun roots ending in non-reduced vowels such as Oma ∼ Oma-s ‘grandma(s)’) is part of the Word Level (see Wiese 2009 and references cited there on detailed arguments for the special status of plural-s). Even though all plural morphology under discussion in this paper is identified with the Stem Level, the stratal organization plays a restricted role in the analysis in restricting the possible shapes of inputs (e.g. excluding schwa+nasal syllables), and accounting for the neutralization of crucial stem-level contrasts in the Phrase-Level (postlexical) phonology resulting in surface opacity (see Sect. 4).

2.3 Assumptions on German vowels and syllable nuclei

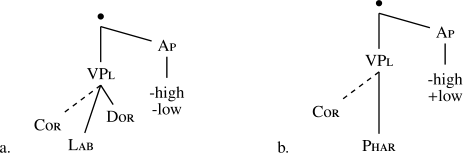

I adopt the Unified Feature Geometry of Clements and Hume (1995) with slight modifications adapting it to the German vowel system. The major design feature of the Clements-Hume system setting it apart from other feature-geometric proposals (e.g. Sagey 1986 and Halle et al. 2000) is that vowels and consonants utilize the same place features (being dominated by different non-terminal nodes (VPlace vs. CPlace), where Vplace is also obligatorily dominated by a CPlace node) which renders it well-suited to capture the alternation between consonantal suffix place and vocalic fronting in umlaut which I analyze here. Note that, departing slightly from Clements and Hume, I assume that [±consonantal] (in their proposal the inverse feature [±vocoid]) is not an inherent part of the segmental root node but on a separate tier associated to the root, which allows a simpler representation of the fact that the underspecified plural segment • is underlyingly neither a consonant nor a vowel acquiring a [±consonantal] specification according to its context.

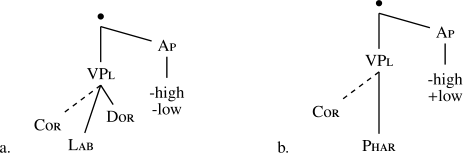

Full vowels: Following Lahiri and Evers (1991), I assume that back and front vowels are characterized by the privative features [Dor(sal] and [Cor(onal)] respectively, dominated by the VPlace node (Clements and Hume 1995), illustrated for [e/ε], [o/ɔ] and [ø/œ] in (17a,b,c), whereas the low vowel [a] is only specified for [Phar(yngeal)] (17d), hence neither Dorsal nor Coronal. Full vowels are hence specified by exactly one lingual place feature (and additionally [Labial] in the case of the back round vowels). Vocalic height in full vowels is represented by the Ap(erture) node dominating the features [±high] and [±low].

-

(17)

Full vowels

In line with Yu (1992, see also Lieber 1992 and Scharinger 2006 for experimental evidence), I interpret the possibility of a stem vowel to undergo umlaut as a consequence of underspecification. Thus the vowel of a noun such as Sohn [zoːn] ‘son’ umlauting to plural Söhn-e [ˈzøː.nə] has height and rounding features (in the case of Sohn [-high -low Labial]), but is specified for neither Dor nor Cor, notated here as “O” (18a) (fully parallel: the underspecified high round back vowel “U” as in Gut [guːt] ∼ Güt-er [gyː.tɐ] ‘good(s)’ (18b)). In the singular, Dor is filled in by default resulting in a back vowel, while in the plural the floating Cor of the suffix associates to the vowel resulting in [øː]. On the other hand, a minimally distinctive non-umlauting noun such as Thron [tʀoːn] ‘throne’, plural Thron-e [ˈtʀoː.nə] is underlyingly fully specified as Dorsal as in (17b). Similarly, an umlauting low vowel (notated as capital “A”) as in Rat [ʀa ːt] ∼ Räte [ˈʀεː.tə] ‘council(s)’ is not specified for Pharyngeal, but only for [+low-high] (18b) in contrast to the fully specified immutable [a] in (17d). (18c) becomes Pharyngeal in the singular by default, but results in [ε] (17a) if the floating plural Cor associates to it (collaterally changing [+low] to [-low]). See Sect. 4.3 for an in-depth discussion of vocalic underspecification.

-

(18)

Underspecified full vowels

Reduced vowels: The central mid vowel [ə], is arguably the default (epenthetic) vowel of German (Wiese 1986, 1996b; Hall 1992; Noske 1993), which corresponds to its status in the analysis of plural allomorphy proposed here: Schwa is the realization of the underspecified plural segment, if no other factors enforce a more specified segment. Following van Oostendorp (1995), I take [ə] to be a maximally underspecified vowel. In particular, I assume that it not only lacks specific place but also height features (in terms of the assumed feature geometry: the Aperture node), hence that it only bears a VPlace node. The lack of height features also characterizes the low central vowel [ɐ], which I will call ‘a-schwa’ in the following. The a-schwa has an additional Pharyngeal feature dominated by VPlace; it is thus representationally a reduced [a]. (19) shows the representations for reduced vowels (19a,b) and the defective segment of the plural affix (19c):

-

(19)

Reduced vowels

Syllabic sonorants: The status of schwa is closely connected to the variable realization of sonorants in post-consonantal position (orthographic en, em, el). For example, a noun such as Atem ‘breath’ pronounced as [ʔaː.təm] in the literary standard pronunciation is naturally produced as [ʔaː.t ] in colloquial speech. Thus grammatically there is free variation between syllabic consonants and coda consonants headed by schwa, whereas the presence of schwa is clearly phonemic in other contexts (cf. e.g. the contrast between Beet [beːt] ‘flower bed’ and Bete [beː.tə] ‘beet root’). I will take here the conservative position that in the input to the stratum where plural morphophonology applies (the Stem Level) final postconsonantal sonorants uniformly head weak syllables headed by sonorant consonants (as in [ˈʔaː.t

] in colloquial speech. Thus grammatically there is free variation between syllabic consonants and coda consonants headed by schwa, whereas the presence of schwa is clearly phonemic in other contexts (cf. e.g. the contrast between Beet [beːt] ‘flower bed’ and Bete [beː.tə] ‘beet root’). I will take here the conservative position that in the input to the stratum where plural morphophonology applies (the Stem Level) final postconsonantal sonorants uniformly head weak syllables headed by sonorant consonants (as in [ˈʔaː.t ]), hence are not preceded by schwa, whereas the observed free variation is due to variable constraint ranking at the Phrase Level (Wiese 1986, 1996b; Noske 1993, see Sect. 4.1 for details). A special case is the rhotic [ʀ] that cannot occur in rhymes where it alternates with the a-schwa [ɐ] (e.g. in Bär [beːɐ] ∼ Bären[ˈbeː.ʀən] ‘bear(s)’), which I will discuss in detail in Sects. 3.4 and 4.2.

]), hence are not preceded by schwa, whereas the observed free variation is due to variable constraint ranking at the Phrase Level (Wiese 1986, 1996b; Noske 1993, see Sect. 4.1 for details). A special case is the rhotic [ʀ] that cannot occur in rhymes where it alternates with the a-schwa [ɐ] (e.g. in Bär [beːɐ] ∼ Bären[ˈbeː.ʀən] ‘bear(s)’), which I will discuss in detail in Sects. 3.4 and 4.2.

3 The core analysis

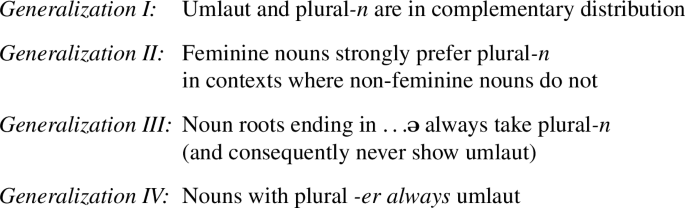

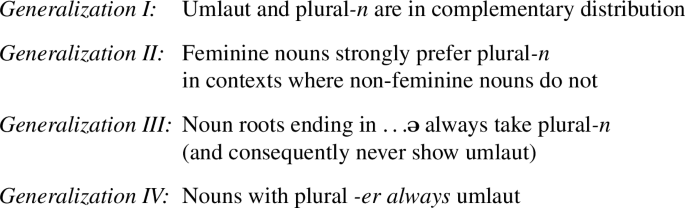

In this section, I show that a Generalized Nonlinear Affixation analysis of German plural formation provides a solution to Wunderlich’s Dilemma—systematic relations between aspects of plural spellout in the face of ultimate unpredictability—by deriving the central generalizations in (20): (Augst 1979; Wurzel 1998; Neef 1998; Wunderlich 1999, and the online supplementary material):Footnote 4

-

(20)

Central generalizations on plural umlaut and suffix allomorphy

In the following subsections, I will introduce step-by-step the optimality-theoretic constraints which capture these generalizations. In Sect. 5, I will show that a minimal extension of the analysis developed here also captures Wiese’s Generalization—the word-final strong-weak template in noun plurals. I start my discussion by introducing the bare backbone mechanics I assume for umlaut, the two constraints in (21):

-

(21)

Central constraints governing umlaut

c → V captures the preference for associating a floating coronal feature to a vowel (instead of a consonant or to leaving it floating). This preference is restricted by higher ranked *V\(_{\mbox{2\{c,d,p\}}}\) which encodes the fact that German vowels are either front, back or low, but never combine the relevant Vplace features. Thus *V\(_{\mbox{2\{c,d,p\}}}\) blocks association of coronal to vowels that are already specified for Dorsal or Pharyngeal (i.e., fully specified back and low vowels) resulting in representations as in (22):

-

(22)

The effect of c → V is best visible in one of the most transparent patterns, masculine nouns with -e and obligatory umlaut in the plural, such as Sohn [zoːn] ∼ Söhne [ˈzøː.nə] ‘sons(s)’ (23a). Recall from Sect. 2.3 that the stem vowel of Sohn is mid ([-high -low]) and Labial, but otherwise underspecified for VPlace (indicated by capital O in the input) as in (18-a), and the only underlying affix here is the generic plural marker, whose floating Coronal feature ( ) is realized by association to the stem vowel (indicated by subscripting) resulting in front [øː] whereas its segmental root node is realized as [ə] (23a-ii).

) is realized by association to the stem vowel (indicated by subscripting) resulting in front [øː] whereas its segmental root node is realized as [ə] (23a-ii).

By assumption, a minimally distinct noun such as Thron [tʀoːn] ∼ Thron-e [ˈtʀoː.nə] ‘throne(s)’, for which umlaut plural is impossible, differs underlyingly only in that the stem vowel is specified by association to Dorsal (indicated by subscripted ‘d’, see (17-b) for the full vowel representation for (23b-i), and (22a) for (23b-ii)). Since *V\(_{\mbox{2\{c,d,p\}}}\) outranks c → V, umlaut as in (23b-ii) is blocked. Since Max Coronal is ranked too low to have an effect, the feature remains floating and unpronounced (23b-i) (see Sect. 3.2 for a formal account of this fact):

-

(23)

The analysis for low-vowel stems is completely parallel. An alternating root such as Rat [ʀa ːt] ∼ Räte [ˈʀεː.tə] ‘council(s)’ has a stem vowel whose aperture features are low ([+low -high]), but which is fully underspecified for VPlace (indicated by capital A (18-c), allowing for satisfaction of c → V (24a) without violating *V\(_{\mbox{2\{c,d,p\}}}\), whereas a root vowel that is underlyingly specified as Pharyngeal as in Maat [ma ːt] ∼ Maat-e [ˈma ː.tə] ‘steward(s)’ is immune to association of floating coronal (24b) (see (17-d) for the full vowel representation for (24b-i), and (22b) for (24b-ii)):

-

(24)

So far, the analysis is a conservative constraint-based restatement of classic autosegmental analyses: Floating features are associated whenever possible, restricted by underspecification to contexts where it is not feature-changing (see Lodge 1989; Yu 1992; Scharinger 2009 for earlier proposals tying German umlaut to underspecification). Note however an important containment effect: *V\(_{\mbox{2\{c,d,p\}}}\) is the general clone of the constraint under containment (cf. (15) in Sect. 2.1). Thus even if we make the underlying Pharyngeal association of the vowel in (24b) phonetically invisible and associate it to Coronal, the constraint is still violated. Underspecification captures the fact that plural umlaut (and its consequences for segmental plural allomorphy) is not fully predictable from the bare singular stem, which is the first half of Wunderlich’s problem.Footnote 5 In the following subsections, I will extend the analysis to also capture the implicational generalizations on plural formation to solve this dilemma.

3.1 Generalization I: Complementary distribution of umlaut and plural-n

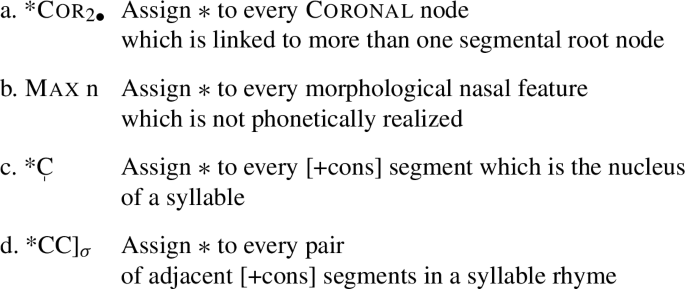

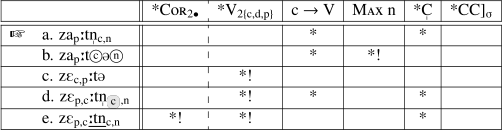

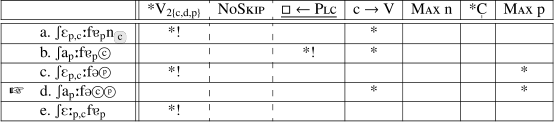

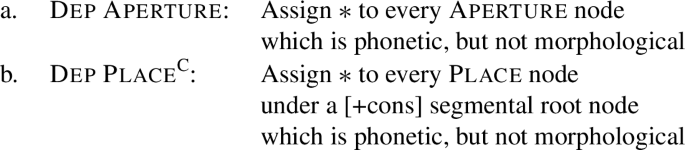

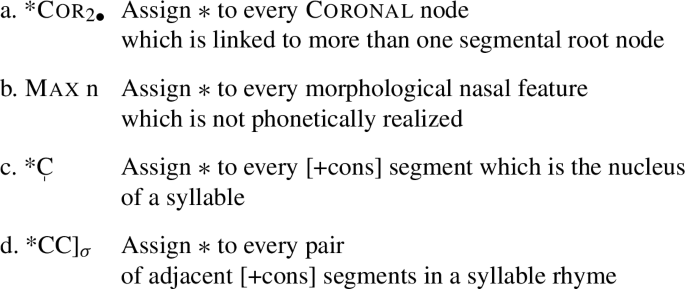

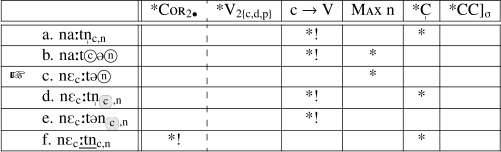

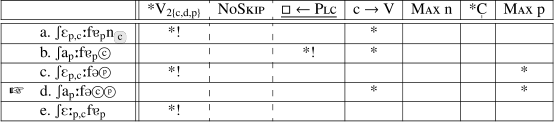

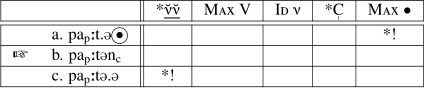

We are now in a position to derive the mutual exclusiveness of plural-n and umlaut, based on underlying affix material, the Coronal feature shared by all plural forms and the floating [nasal] introduced by feminine plurals. Their surface realization is crucially governed by the four constraints in (25):

-

(25)

Constraints governing [ Coronal ] and [nasal]

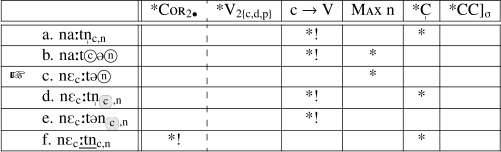

*Cor\(_{\mbox{2$\bullet$}}\) is the crucial constraint in deriving the complementarity of umlaut and -n. In a feminine noun such as Naht [na ːt] ∼ Nähte [ˈnεː.tə] ‘seam(s)’ the underlying vowel is again underspecified, allowing in principle for umlaut. The floating coronal feature could now either be realized as part of a n-suffix as in (26a) (or even a stem segment as in (26b)) or as umlaut as in the correct output in (26c). That the umlaut candidate, where the nasal feature realizing the feminine plural affix remains floating is preferred over the n-candidate (which hosts the floating nasal) is due to the ranking of c → V above Max n, but this doesn’t exclude a further option: the affix feature might be associated to both the suffix segment and the stem vowel as in (26f) (double association of Coronal is marked here informally as two subscript c’s connected by a horizontal line), which is blocked by *Cor\(_{\mbox{2$\bullet$}}\). Thus the constraint ensures that the plural Coronal feature is available only in one segment and can either trigger umlaut or form part of a coronal nasal, but not serve both duties simultaneously. Note finally that inserting an additional epenthetic Coronal feature as in (26d,e) is also excluded by c → V since the epenthetic Coronal would also not be associated to a full vowel.Footnote 6

-

(26)

Input: nAːt+

•+

•+ (Naht ‘seem’, fem.)

(Naht ‘seem’, fem.)

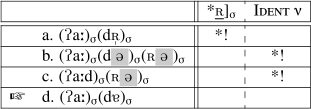

The tableau in (27) illustrates the complementary situation, a feminine noun (Saat [za ːt] ∼ Saaten [ˈza ː.t ] ‘seed(s)’) with an underlyingly fully specified back vowel. As in (24-b), the floating coronal feature cannot trigger umlaut due to undominated *V\(_{\mbox{2\{c,d,p\}}}\) (27c,d,e) and is thus forced to combine with the floating root node and the nasal feature of the feminine plural suffix to form -n (27a) by virtue of Max n (excluding (27b)):

] ‘seed(s)’) with an underlyingly fully specified back vowel. As in (24-b), the floating coronal feature cannot trigger umlaut due to undominated *V\(_{\mbox{2\{c,d,p\}}}\) (27c,d,e) and is thus forced to combine with the floating root node and the nasal feature of the feminine plural suffix to form -n (27a) by virtue of Max n (excluding (27b)):

-

(27)

Input: za \(_{\mbox{p}}\)ːt+

•+

•+ (Saat ‘seed’, fem.)

(Saat ‘seed’, fem.)

Note that the novel, purely phonological, explanation for Generalization I provide here is essentially parallel to classical analyses of floating featural affixes such as labialization in Chaha (Akinlabi 1996; Rose 1997, 2007), where the same morphemic material can show up in different segmental positions in a word according to phonological well-formedness conditions (see also Zoll 1996 and Kim and Pulleyblank 2009 for cases of glottalization which alternate with full glottal segments). In Sect. 4, I will show that generalizations of this type are inherently problematic for amorphous approaches to morphophonology which deny that phonological exponence is piece-based (Neef 1996; Russel 1999; Inkelas 2012, 2014).

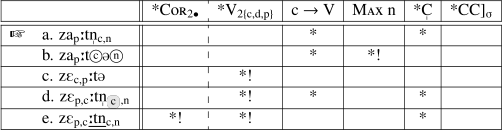

3.2 Generalization II: The feminine-nasal correlation

The predisposition of feminine nouns for plural-n in contexts where masculine and neuter nouns exhibit -ə is evident from non-umlauting masculine nouns such as Maat ∼ Maate (24-b) which forms a quasi-minimal pair with feminine Saat ∼ Saaten in (27). This difference is an emergent effect of  which ensures that non-umlauting masculine and neuter nouns, which have a freely available (floating) token of Coronal, still avoid forming an n-suffix as in (28a). Note that (28a) doesn’t violate *CC]σ since the stem-final t is not in a rhyme, but the onset of the following syllabic n.Footnote 7 (28) gives the full derivation of a masculine non-umlauting noun such as Maate (24-b). Since masculine nouns lack the floating nasal feature introduced by the [+feminine +plural] affix, and

which ensures that non-umlauting masculine and neuter nouns, which have a freely available (floating) token of Coronal, still avoid forming an n-suffix as in (28a). Note that (28a) doesn’t violate *CC]σ since the stem-final t is not in a rhyme, but the onset of the following syllabic n.Footnote 7 (28) gives the full derivation of a masculine non-umlauting noun such as Maate (24-b). Since masculine nouns lack the floating nasal feature introduced by the [+feminine +plural] affix, and  isn’t protected by any high-ranked faithfulness constraint, Max n becomes inert, and the suffixal coronal feature stays floating and unpronounced (since the constraint is undominated, I omit *Cor\(_{\mbox{2$\bullet$}}\) and candidates violating it in (28) and the following tableaux):Footnote 8

isn’t protected by any high-ranked faithfulness constraint, Max n becomes inert, and the suffixal coronal feature stays floating and unpronounced (since the constraint is undominated, I omit *Cor\(_{\mbox{2$\bullet$}}\) and candidates violating it in (28) and the following tableaux):Footnote 8

-

(28)

Input: ma \(_{\mbox{p}}\)ːt+

• (Maat ‘steward’, masc.)

• (Maat ‘steward’, masc.)

A similar asymmetry with suffixal -n showing up in feminines, but not in neuter and masculine nouns, holds for nouns ending in syllabic l, where feminine nouns consistently show -n, but non-feminine nouns show no segmental suffix at all, as shown in (29). Once again, umlaut is in complementary distribution with suffix-n:

-

(29)

Nouns ending in C+

Footnote 9

Footnote 9

Now recall that noun roots orthographically ending in en and el have syllabic final consonants in the Stem-Level phonology, but exhibit free variation with [əl] and [ən] at the Phrase Level. I assume that word-final syllabic sonorants already acquire their status as syllabic nuclei at the Root Level, and are forced to preserve their syllabic role at the Stem Level by the faithfulness constraint in (30):

-

(30)

Assuming that Ident  is undominated, as in (31), it blocks the possibility to break up a [

is undominated, as in (31), it blocks the possibility to break up a [ n] cluster by an epenthetic ə as in (31a,b), and *CC]σ becomes decisive in choosing non-realization of the defective affix-• (31d) over -n (31c). For explicitness, (31) also contains the faithfulness constraint Max • which requires segmental realization of the defective plural segment, but is ranked below all other markedness and faithfulness constraints discussed so far (‘

n] cluster by an epenthetic ə as in (31a,b), and *CC]σ becomes decisive in choosing non-realization of the defective affix-• (31d) over -n (31c). For explicitness, (31) also contains the faithfulness constraint Max • which requires segmental realization of the defective plural segment, but is ranked below all other markedness and faithfulness constraints discussed so far (‘ ’ denotes an undominated hence phonetically unrealized root node).Footnote 10

’ denotes an undominated hence phonetically unrealized root node).Footnote 10

-

(31)

Input: ta \(_{\mbox{p}}\)ːd

+

+ • (Tadel ‘reproach’, masc.)

• (Tadel ‘reproach’, masc.)

Feminine nouns again differ in triggering morphological insertion of a floating nasal feature. Since Max n is ranked above *CC]σ, we get a full segmental n-suffix:

-

(32)

Input: na \(_{\mbox{p}}\)ːd

+

+ •+

•+ (Nadel ‘needle’, fem.)

(Nadel ‘needle’, fem.)

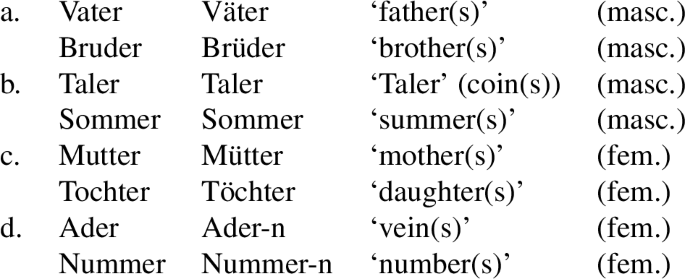

The feminine-nasal correlation also extends to [ɐ]-final nouns (cf. masculine Anker ∼ Anker [ˈʔa ŋ.kɐ] ‘anchor’ vs. feminine Ader [ˈʔa ː.dɐ] ∼ Ader-n [ˈʔa ː.dɐn] ‘vein(s)’), a pattern I will take up in detail in Sect. 4.2.

3.3 Generalization III: Schwa-final nouns always take -n (and never umlaut)

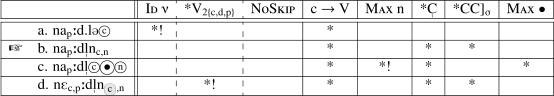

Whereas consonant-final nouns show a marked -n vs. -ə/-Ø asymmetry reflecting the feminine/non-feminine distinction, this contrast breaks down with ə-final nouns which all form their plural following an identical pattern, independently of gender (in fact all umlauting examples discussed so far didn’t have final [ə]). While the generalization has two parts ① Nouns lexically ending in …ə never umlaut (Pate [ˈpa ː.tə] → *Päte [ˈpεː.tə]/*Päte-n [ˈpεː.tən]/*Päter [ˈpεː.tɐ]) and ② Nouns lexically ending in …ə always suffix -n (Pate [ˈpa ː.tə] → Pa.te-n [ˈpa ː.tən]/*Pate [ˈpa ː.tə]), under the approach here both parts are inextricably linked because the analysis developed so far already predicts that umlaut and plural-n are in complementary distribution.

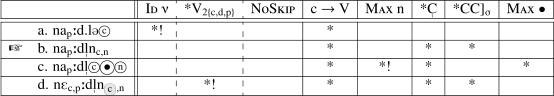

The gist of the derivation of Generalization III is that schwa is a defective intervenor which cannot itself serve as the host for floating material, but blocks association of the umlaut trigger (floating VPlace + Coronal) to the full vowels preceding it. Technically this amounts to the standard autosegmental no-gapping restriction that association might not skip intervening nodes (Archangeli and Pulleyblank 1994; Walker 1998; Ní Chiosáin and Padgett 2001), which is formulated with reference to VPlace and Place nodes in (33):

-

(33)

(34) shows an exemplary configuration violating NoSkip. The floating Coronal of the generic plural suffix associates to the VPlace node of the [a] in Rate [ˈʀa ː.tə] ∼ Rate-n [ˈʀa ː.tən] ‘rate(s)’ (fem.) which leads to a violation because the empty VPlace node of the final [ə] intervenes:

-

(34)

Violating NoSkip

Under the assumption that NoSkip is undominated (alongside *V\(_{\mbox{2\{c,d,p\}}}\)) the featural affixation analysis straightforwardly captures the second part of Generalization III (the observation that ə-final nouns never exhibit umlaut) as shown in (35) for Rate. All umlauting candidates (35c,d,) are ruled out directly by NoSkip, and the lower-ranked faithfulness constraints ensure that affixal root node, [nasal], and [Coronal] form an n-suffix:

-

(35)

Input: ʀAːtə+

•+

•+ (Rate ‘rate’, fem.)

(Rate ‘rate’, fem.)

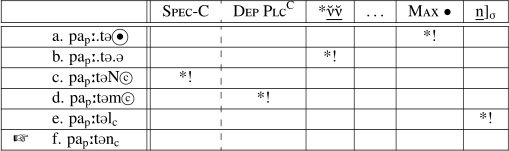

The same result follows for ə-final masculine nouns such as Pate ‘godfather’ under the proviso that an undominated phonotactic constraint rules out two adjacent weak syllable nuclei ( ) as in (36b), a combination systematically excluded in German (see Sect. 5 for a full analysis). Note also that in contrast to (35a) the [nasal] feature in (36a) is epenthetic, indicating that general faithfulness constraints against nasal epenthesis (e.g. Dep n) are ranked too low to be effective (for consonant-final masculine roots such as Maat ∼ Maat-e creation of a nasal suffix is excluded by

) as in (36b), a combination systematically excluded in German (see Sect. 5 for a full analysis). Note also that in contrast to (35a) the [nasal] feature in (36a) is epenthetic, indicating that general faithfulness constraints against nasal epenthesis (e.g. Dep n) are ranked too low to be effective (for consonant-final masculine roots such as Maat ∼ Maat-e creation of a nasal suffix is excluded by  , not by faithfulness constraints, cf. tableau (28)):

, not by faithfulness constraints, cf. tableau (28)):

-

(36)

Input: pAːtə+

• (Pate ‘godfather’, masc.)

• (Pate ‘godfather’, masc.)

This effectively derives part 2 of Generalization III (ə-final nouns always suffix -n): n is the only phonotactically licit realization of the root node provided by the generic plural suffix, and independently enforced by faithfulness constraints on suffixal segments for feminine nouns as in (35). Note finally that it is irrelevant whether the non-front stem vowels in ə-final nouns are assumed to be specified or unspecified for vocalic place. Blocking of umlaut follows under the assumption of underspecification as in (35) and (36), and would only be redundantly enforced through *V\(_{\mbox{2\{c,d,p\}}}\) if we posit underlying Pharyngeal or Dorsal specifications.

Importantly, there is good evidence that the complementary distribution of stem-final schwa and plural umlaut is not an idiosyncratic morphological pattern, but follows a more general phonological restriction. German diminutives which show virtually exceptionless umlaut (Féry 1994; Wiese 1996a; Klein 2000) (e.g. Bänd-chen [ˈbεnt.çən] from Band [bant] ‘volume’ and Söhnchen [ˈzøːn.çən] from Sohn [zoːn] ‘son’) trigger dropping of stem-final schwas (e.g. Läd-chen [ˈlεːt.çən] from Lade [ˈla ː.də] ‘chest’ and Büd-chen [ˈbyː.tçən] from Bude [ˈbuː.də] ‘booth’) thus effectively eliminating the problematic intervenor (see Trommer 2016 for a phonological account of why diminutive umlaut is ‘stronger’ than plural umlaut and Hermans and van Oostendorp 2008 for discussion of a related pattern in Limburg Dutch). German verbs ending in coronal stops exhibit a regular schwa epenthesis process before inflectional suffixes starting with a coronal obstruent (37c,d), but not after other consonants (37a,b). Crucially, schwa epenthesis is suppressed if the verb exhibits umlaut in the 2sg and 3sg present (37e,f) (Neef 1996):

-

(37)

Schwa (non-)epenthesis in German verbs

Whereas an analysis of these patterns is beyond the scope of this paper, it should be clear that the complementarity between intervening schwa and umlaut is pervasive and achieved by at least three different repair strategies: deletion of schwa in diminutives, suppression of schwa-epenthesis in verb inflection, and failure to umlaut in nominal plurals. These three patterns hence form a classical phonological conspiracy (Kisseberth 1970; Kager 1999), which is directly captured in a phonological analysis based on a ban against intervening schwas, as proposed here, but remains accidental in a purely morphological analysis of plural allomorphy.

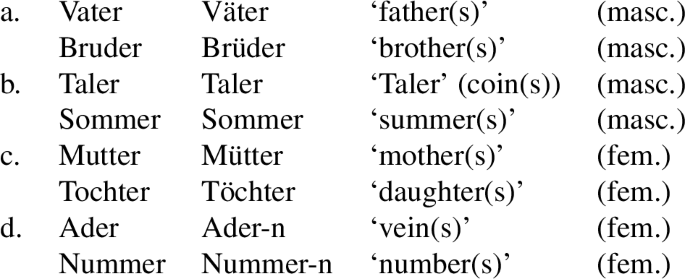

3.4 Generalization IV: ɐ-plurals always umlaut

Plural-er (-ɐ) is the near mirror image to plural-n: While -n is dominant with feminine nouns, -er is restricted to non-feminine, especially neuter nouns (see Sect. 6.1 for an analysis of exceptional masculine nouns with plural -er); and where -n is in complementary distribution with umlaut, er-plurals always exhibit umlaut whenever the stem vowel is not already front. (38) shows this distributional gap schematically:

-

(38)

-er-plurals in neuter nouns Footnote 11

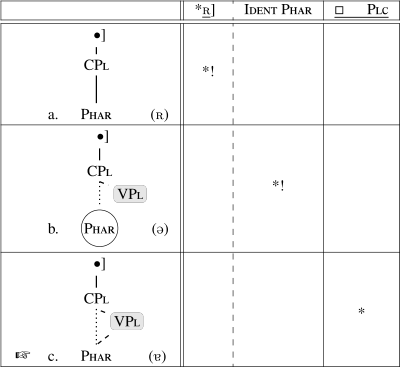

Under the subsegmental analysis proposed here, all instances of neuter plural -er result from a combination of the generic plural suffix  • and the more specific gender-number affix (6-c) repeated in (39):

• and the more specific gender-number affix (6-c) repeated in (39):

-

(39)

Representation for plural-er

Given this representation, the restriction of regular -er to neuter nouns follows directly from the morphosyntactic feature specification of (39). In the following, I will show that its obligatory co-occurrence with umlaut falls out as a natural consequence of the feature-geometric analysis developed so far.

Let us first have a look at the feature-geometric details of an umlauting plural with -er. In contrast to the other number suffixes,  contains a CPlace node, it is in effect a defective consonantal [ʀ] (lacking a segmental root node).Footnote 12 That it cannot surface as a ‘real’ consonant is due to the phonotactic restriction against [ʀ] in syllable rhymes (cf. Sects. 2.3 and 4.2 below).Footnote 13 Since

contains a CPlace node, it is in effect a defective consonantal [ʀ] (lacking a segmental root node).Footnote 12 That it cannot surface as a ‘real’ consonant is due to the phonotactic restriction against [ʀ] in syllable rhymes (cf. Sects. 2.3 and 4.2 below).Footnote 13 Since  also lacks a root node and a VPlace node, and Max Phar is ranked below Dep VPl and Dep •, the only scenario where it can surface is when a free VPlace + • becomes available. This is exactly what happens in neuter nouns with umlaut, as shown in (40a) for Räd-er in contrast to a non-umlauting neuter noun plural such as Schaf-e (40b). The coronal feature of the generic plural suffix shifts to the underspecified VPl node of the noun, thus vacating its own VPlace node By additional association of the plural-VPl to the tautomorphemic root node a complete vocalized [ɐ] results. For Schaf-e, Cor cannot associate to the noun VPl (already associated to Phar) hence blocking spreading of affix Phar to plural VPl:

also lacks a root node and a VPlace node, and Max Phar is ranked below Dep VPl and Dep •, the only scenario where it can surface is when a free VPlace + • becomes available. This is exactly what happens in neuter nouns with umlaut, as shown in (40a) for Räd-er in contrast to a non-umlauting neuter noun plural such as Schaf-e (40b). The coronal feature of the generic plural suffix shifts to the underspecified VPl node of the noun, thus vacating its own VPlace node By additional association of the plural-VPl to the tautomorphemic root node a complete vocalized [ɐ] results. For Schaf-e, Cor cannot associate to the noun VPl (already associated to Phar) hence blocking spreading of affix Phar to plural VPl:

-

(40)

I implement the link between Coronal and Pharyngeal shifting by the constraint in (41), which requires every Place feature (Cor, Phar, Dor, or Lab) to be associated to an underlying (colored) CPlace or VPlace node (where ‘□’ symbolizes color):

-

(41)

to every Place node which is not phonetically dominated by a colored VPlace or CPlace node

to every Place node which is not phonetically dominated by a colored VPlace or CPlace node

is satisfied by both forms in (40) since every instance of Phayryngeal and Coronal is dominated phonetically by a colored CPlace or VPlace node (although these are not necessarily pronounced, such as the final Cplace node in (40b) which is not dominated by a segmental root node). On the other hand,

is satisfied by both forms in (40) since every instance of Phayryngeal and Coronal is dominated phonetically by a colored CPlace or VPlace node (although these are not necessarily pronounced, such as the final Cplace node in (40b) which is not dominated by a segmental root node). On the other hand,  blocks hypothetical examples of non-umlauting stems with -ɐ, where Coronal is left afloat (42a) or linked to an epenthetic VPlace node as in (42b) (recall also that pharyngeal [ʀ] is excluded in rhymes, hence Cplace – Pharyngeal cannot associate directly to the floating plural root node):

blocks hypothetical examples of non-umlauting stems with -ɐ, where Coronal is left afloat (42a) or linked to an epenthetic VPlace node as in (42b) (recall also that pharyngeal [ʀ] is excluded in rhymes, hence Cplace – Pharyngeal cannot associate directly to the floating plural root node):

-

(42)

Crucially, under this analysis, there is no sense in which plural-er ‘enforces’ umlaut. It is in fact the other way around: Only if underspecification of root vowels independently creates a free segment+VPl slot, this configuration enforces plural-er by Emergence of the Unmarked for low-ranked Max Pharyngeal, as shown by the contrast of (43b) and (43e) (corresponding to (40-a)):

-

(43)

Input: ʀAːd+

•+

•+ (Rad ‘cycle’, neut.)

(Rad ‘cycle’, neut.)

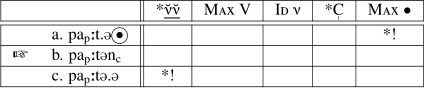

For a neuter noun such as Schaf [ʃa ːf] ∼ Schaf-e [ˈʃa ː.fə] ‘sheep’ (sg./pl.) without umlaut (and hence a stem vowel specified for [Pharyngeal]),  blocks reassociation of Pharyngeal as in (44) (where (44b) corresponds to (42), and (44d) to (40-b):

blocks reassociation of Pharyngeal as in (44) (where (44b) corresponds to (42), and (44d) to (40-b):

-

(44)

Input: ʃa \(_{\mbox{p}}\)ːf+

•+

•+ (Schaf ‘sheep’, neut.)

(Schaf ‘sheep’, neut.)

It follows correctly as a corollary that schwa-final nouns can never take plural -er since they block umlaut. Note finally that there is an apparent problem for the correlation between -er suffixation and umlaut: frontvowel stems with -er such as Kind [kɪnt] ∼ Kinder [ˈkɪn.dɐ] ‘child(ren)’. I will take up this pattern in Sect. 4.3.

4 Surface opacity

The subsegmental analysis highlights the fact that the generalizations governing German plural exponence are in crucial respects surface-opaque. Thus we might attempt to capture the complementarity between plural suffix-n and umlaut (Generalization I) by a phonological surface constraint as in (45):

-

(45)

*V\(_{\mbox{front}}\) …n

Crucially, (45) would overapply. Beyond excluding plurals such as *Päten, it also rules out many correct German word forms such as the infinitives wetten [ˈvε.tən] ‘to bet’ and dösen [ˈdøː.zən] ‘to doze’. This cannot be amended by restricting (45) to nominal plural forms since here also n and front vowels can freely co-occur if either the [n] or the front vowel are an underlying part of a noun root as in Becken ∼ Becken [ˈbε.kən] ‘pool(s)’, and Gräte [ˈgʀεː.tə] ∼ Gräten [ˈgʀεː.tən] ‘fishbone(s)’ respectively. What is blocked is not phonological surface co-occurrence, but double realization of the same morphological exponent. This kind of opacity, which follows naturally in a morpheme-based account, is inherently problematic for an amorphous approach where morphological exponence is governed by phonological constraints on surface representations (Neef 1996; Russel 1999; MacBride 2004). The same kind of opacity also holds for generalization IV ([ɐ]-plurals always umlaut) which cannot be captured without recourse to concatenative morphological structure by something like (46):

-

(46)

*V\(_{\mbox{non-front}}\) …ɐ

Thus whereas a singular such as Rad can only have an umlauting plural (Räd-er not *Rader), there are non-umlauting roots when [ɐ] is not the segmental plural affix, but part of the noun root, as in Anker ∼ Anker ‘anchor(s)’, Otter ∼ Otter ‘otter’ besides umlauting examples such as Vater ∼ Väter and Mutter ∼ Mütter.

The third case of opacity which cannot be captured by a surface constraint is the schwa-umlaut generalization (Generalization III). For example, the plurals of Lade ‘tray’ (Laden) and of Fladen ‘thin bread’ (Fladen) are virtually homophonous, but the plural of Laden ‘shop’ is Läden whereas Lade could in principle not be umlauting in the plural. Thus umlaut markedly differentiates between Laden and Lade-n.

This last example however also points to a potential opacity problem for the concatenativist analysis proposed here: If the impossibility of Läden as the plural of Lade is due to the phonological intervention of [ə], why does schwa not intervene in the same way in the plural Läden for Laden? Similarly, vocalic intervention seems to be potentially problematic for [ɐ]-final roots such as Vater/Väter for which we might expect intervention against umlauting (i.e. against Coronal-spreading) in analogy to Lade and Pate.

The answer I propose in this section is that these cases not only involve opacity of morphological structure, but also genuinely phonological opacity where the plurals for Laden and Lade are different in intermediate steps of their derivational history, a fact which falls out naturally from the cyclic architecture of Stratal Containment and the traditional assumption that the relevant word-final post-sonorants (orthographic el, en, etc.) are syllabic consonants at the point when they enter the Stem-Level phonology. I will work out this analysis in Sect. 4.1 for root-final n-cases and show in Sect. 4.2 that it also derives the behavior of root-final [ɐ] by taking into account the fine structure of feature-geometric representations.

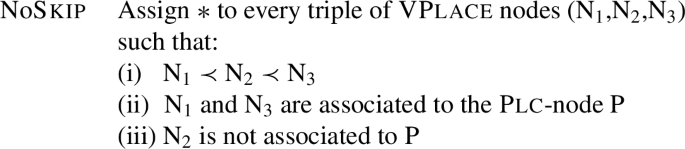

4.1 Umlaut-non-intervention of final schwas

(47) presents more data illustrating the crucial asymmetry in syllabic n-final plurals between the possibility of umlaut with underlying root-n and its impossibility with affixal -n:

-

(47)

n-final nouns Footnote 14

Now remember from Sect. 2.3 that orthographic en is phonetically variably pronounced as schwa+n (e.g. [ˈla ː.dən]) or as a syllabic [n] ([ˈla ː.d ]). My interpretation of these facts in terms of Stratal OT follows the traditional position of Wiese (1996b) that at the input of the Stem Level nouns like Laden have consistently syllabic sonorants (/la ː.d

]). My interpretation of these facts in terms of Stratal OT follows the traditional position of Wiese (1996b) that at the input of the Stem Level nouns like Laden have consistently syllabic sonorants (/la ː.d /), not schwas. The only schwa syllables at this level are hence word-final schwas that are lexically distinctive (cf. Lade vs. the verb lad ‘to invite’).Footnote 15n-affixation at the Stem Level leads then to a final [ə+n] sequence. The phrase-level phonology of German neutralizes postconsonantal sonorants, and schwa+sonorant variants (Wiese 1986, 1996b; Noske 1993), resulting in free variation between both realizations.Footnote 16

/), not schwas. The only schwa syllables at this level are hence word-final schwas that are lexically distinctive (cf. Lade vs. the verb lad ‘to invite’).Footnote 15n-affixation at the Stem Level leads then to a final [ə+n] sequence. The phrase-level phonology of German neutralizes postconsonantal sonorants, and schwa+sonorant variants (Wiese 1986, 1996b; Noske 1993), resulting in free variation between both realizations.Footnote 16

Late neutralization allows us to locate the opacity in umlaut blocking at the Stem Level (the stratum where plural inflection is concatenated and evaluated phonologically). Here Lade-n has a schwa, whereas Laden has not:

-

(48)

At the Stem Level, the syllabic status of final syllabic sonorants is protected by the undominated faithfulness constraint Ident  (30).

(30).

Now, since there is no schwa in nouns with a root-final syllabic n, NoSkip is not violated (as in the suboptimal candidates in (35) and (36), and the possibility of umlaut becomes contingent on the full or partial specification of the stem vowel, predicting the distinctive behavior of Fladen (with fully specified underlying a, and hence no umlaut), and umlauting Laden (49). Ident  blocks the realization of the underspecified plural root node as schwa (49a) so that it remains floating and unpronounced:

blocks the realization of the underspecified plural root node as schwa (49a) so that it remains floating and unpronounced:

-

(49)

Input: lAːd

+

+ • (Laden ‘shop’, masc.)

• (Laden ‘shop’, masc.)

4.2 Non-intervention in ɐ-final roots

Noun roots ending in [ɐ] (underlying [ʀ]) present a further variant of the opacity problem of vocalic intervention. These nouns show the familiar three options, ① umlaut with Ø-plural (without [n]) (50a,c), ② masculine plurals without umlaut and Ø-suffix (50b), and ③ feminine plurals without umlaut, but with plural-n (50d):

-

(50)

Basic plural patterns of [ɐ]-final nouns Footnote 17

(51) and (52) show the basic analysis for Vater and Taler. Note that (51b) and (52)[b] violate the generalized markedness constraint *CC]σ since n is a surface and ɐ an underlying consonant:

-

(51)

Input: fAːt

+

+ • (Vater ‘father’, masc.)

• (Vater ‘father’, masc.)

-

(52)

Input: ta \(_{\mbox{p}}\)ːl

+

+ • (Taler (coin) , masc.)

• (Taler (coin) , masc.)

These evaluations presuppose that NoSkip is not violated in the winning candidates (51d) and (52c2), but since the output correspondent of /ʀ/ is the vowel [ɐ] (hence a segment with a VPlace node), we would expect that it intervenes for association of Coronal to preceding stem vowels, leading to a fatal violation of NoSkip. Hence umlaut for Vater in (51) should be blocked counter to fact.

In the following, I will show that the non-intervention of [ɐ] follows from the very fact that it is derived from [ʀ], and not an underlying vowel.Footnote 18 Apart from their complementary distribution, the central motivation for the claim that [ɐ] is vocalized [ʀ] comes from the pervasive role of alternations between [ɐ] and [ʀ] in stem-final position illustrated in (53) with examples from the verbal paradigm, where the 1sg forms (with the suffix -ə) show [ʀ] in onset, and the imperatives (which are bare roots) [ɐ] in coda position:

-

(53)

ʀ-vocalization in verbs

Following the bulk of the literature on German phonology, I will assume that all instances of output [ʀ]/[ɐ] are /ʀ/ at the the input of the Stem Level (see Hall 1993; Wiese 1996b and references cited there). To show that the autosegmental approach predicts the fact that derived [ɐ] does not intervene in umlaut (Coronal) association, I will first spell out a specific implementation of [ʀ]-vocalization. I assume that both [ʀ] and [ɐ] are characterized by the feature Pharyngeal (Clements 1991; McCarthy 1994). In the Clements and Hume feature geometry adopted here, ʀ-vocalization then amounts to inserting a VPlace node and to reassociating the consonantal Place feature to the epenthetic class node as shown in (54):

-

(54)

I implement [ʀ]-vocalization by two constraints.  captures the insight of Wiese (1996b) that uvular [ʀ] is blocked in all rhyme positions in German:

captures the insight of Wiese (1996b) that uvular [ʀ] is blocked in all rhyme positions in German:

-

(55)

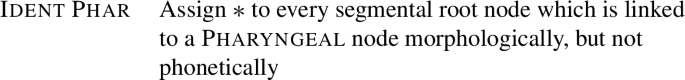

Ident Pharyngeal ensures that pharyngeal segments remain pharyngeal even under vocalization:

-

(56)

Both constraints are ranked above  which would otherwise block surface association of Pharyngeal to an epenthetic Vplace node. (57) shows the interaction of all three constraints:Footnote 19

which would otherwise block surface association of Pharyngeal to an epenthetic Vplace node. (57) shows the interaction of all three constraints:Footnote 19

-

(57)

Input: = a.

(57) illustrates the common core of all [ʀ]-vocalizations in German (i.e., also instances where vocalization happens in codas as in [høː.ʀ-ə] ∼ [ˈhøːɐ] ‘hear’, cf. (53) above). For the cases under discussion here, where [ʀ] is post-consonantal and a syllable nucleus at the input of Stem-Level phonology,  conspires with Ident

conspires with Ident  to enforce vocalization, as shown for the derivation of (ʔa ː)

to enforce vocalization, as shown for the derivation of (ʔa ː) (dɐ)

(dɐ) from underlying (a ː)

from underlying (a ː) (d

(d )

) in (58). Insertion of ə (the major repair process of German for phonotactic violations) could avoid the violation of

in (58). Insertion of ə (the major repair process of German for phonotactic violations) could avoid the violation of  by ‘moving’ [ʀ] into onset position as in (58b,c), but this would violate Ident

by ‘moving’ [ʀ] into onset position as in (58b,c), but this would violate Ident  , which, as we have already seen above, is crucially undominated in the Stem-Level phonology of German.

, which, as we have already seen above, is crucially undominated in the Stem-Level phonology of German.

-

(58)

Input: (a ː)

(d

(d )

) (Ader ‘vein’, fem.)

(Ader ‘vein’, fem.)

Now the potential intervention problem can be made more concrete as in (59) for the plural of Vater (omitting the feature specification of the initial consonant). This configuration fatally violates Noskip, since the epenthetic VPlace node intervenes between the VPlace node dominating the affixal Cor and the VPlace node of the stem vowel just as for Pate in (34):

-

(59)

This is the point where it becomes crucial that the VPlace node in the [ɐ] of Vater is epenthetic unlike the corresponding node in the [ə] of Pate. In (59), this node is inserted before the VPl node of the plural suffix, but while Gen in Containment Theory doesn’t allow for metathesis (i.e. moving the intervening VPl node in Pate), insertion of an epenthetic node is possible in any linear position. Hence a minimally different output candidate for Väter would have the epenthetic VPlace node after the VPlace node of the plural suffix as in (60). Since here no VPl intervenes between the plural Vpl and the base VPl, NoSkip is satisfied.

-

(60)

There is an additional problem which might be suspected here. Although (60) avoids skipping, it seems to aggravate a problem already lurking in (59), namely line crossing. But this is in fact an optical illusion under the standard assumption that line crossing only obtains for elements on the same plane (Cole 1987; Clements and Hume 1995:266; Padgett 2011). Thus technically the association between Cor and VPl in (60) would only cross another association line between the VPlace tier and the Coronal tier, but all other place associations in (60) involve either the Pharyngeal or the CPlace tiers and belong hence to other planes.

Since the VPlace node of [ɐ] does hence not intervene for the purposes of NoSkip, the derivation of umlaut becomes fully parallel to the cases with other base-final sonorants as already shown for Väter in (51).

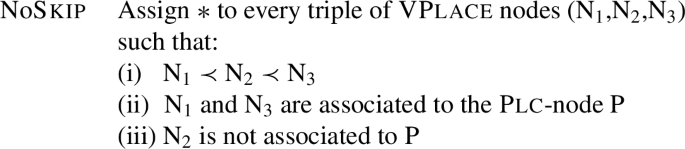

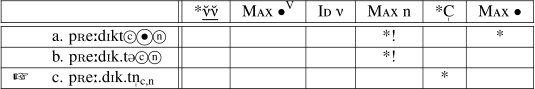

4.3 Covert umlaut

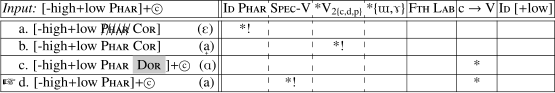

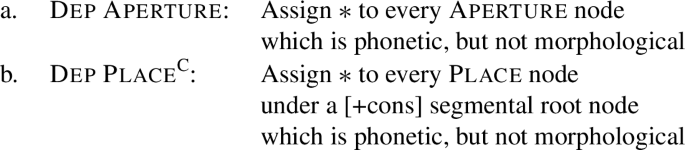

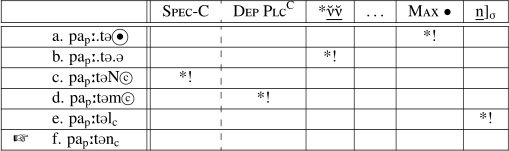

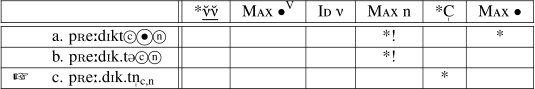

In Sect. 3.4, I have argued that plurals with suffixal -er always umlaut. An apparent problem for this claim is the fact that there are nouns that take plural -er, but have immutable front vowels such as Kind [kɪnt] ∼ Kind-er [ˈkɪn.dɐ] ‘child(ren)’ or Feld [fεlt] ∼ Feld-er [ˈfεl.dɐ] ‘field(s)’. In this section, I show that the behavior of these words is a natural consequence of the defectiveness assumption for umlautable root vowels, which allows different degrees of underspecification. High and mid vowels that are underspecified for lingual place (i.e., Dorsal and Coronal) but have an underlying Labial (rounding) specification alternate between back round and front round vowels (e.g. Grund [gʀʊnt] ∼ Gründ-e [ˈgʀʏn.də] ‘reason(s)’, Rock [ʀɔk] ∼ Röck-e [ˈʀœ.kə] ‘gown(s)’). Non-low vowels which are not underlyingly specified as Labial (as in Kind and Feld) umlaut in the plural by associating the floating Coronal of the plural suffix, but are also realized as front in the singular (by epenthesizing Coronal) since German disallows unrounded non-low back vowels ([ɯ] and [ɤ]). To make this concrete, I assume the constraint in (61) (a more specific version of HavePlace, see McCarthy 2008:279 and references cited there), which has so far been implicit in the analysis, and enforces underspecified full vowels to adopt a default specification whenever no floating Coronal is accessible (recall from Sect. 2.3 that full vowels are by definition vocalic segments that dominate an Aperture node).

-

(61)

Spec-V: A vowel with an Aperture node must be specified for lingual Place

Moreover, I will use *{ɯ,ɤ} as a shorthand for the constraints which exclude these segments from the Standard German vowel inventory, *{y,ø} for the well-known markedness of front round mid vowels (Liljencrants and Lindblom 1972; Flemming 2002), and Fth Lab as a cover term for constraints blocking insertion or deletion of underlying Labial features. The tableaux in (62) and (63) show the ranking of these constraints, and their role in deriving the umlaut pattern for the alternation in Grund [gʀʊnt] ∼ Gründ-e [ˈgʀʏn.də] ‘reason(s)’ (masc.) (similarly neut. Buch [buːx] ∼ Büch-er [ˈbyː.çɐ] ‘book(s)’), where the feature-geometric representations are abbreviated by non-hierarchical feature structures (strikethrough as in “ ” indicating phonetic invisibility and grey shading as in “

” indicating phonetic invisibility and grey shading as in “ ” epenthesis) for reasons of space; I will restrict my attention here to high vowels since mid vowels work in a completely parallel way. The plural (63) shows again integration of floating

” epenthesis) for reasons of space; I will restrict my attention here to high vowels since mid vowels work in a completely parallel way. The plural (63) shows again integration of floating  and fronting, driven by c → V. In the singular, Spec-V enforces insertion of either Coronal or Dorsal, Fth Lab excludes a realization as [i] or [ɯ] (62a,c), and vocalic markedness (*{y,ø}) favors [u] (62d) over [y] (62b):

and fronting, driven by c → V. In the singular, Spec-V enforces insertion of either Coronal or Dorsal, Fth Lab excludes a realization as [i] or [ɯ] (62a,c), and vocalic markedness (*{y,ø}) favors [u] (62d) over [y] (62b):

-

(62)

Standard overt umlaut configuration: singular (Grund)

-

(63)

Standard overt umlaut configuration: plural (Gründe)

As already shown in the skeletal analysis for Thron ∼ Throne in (23-b) (Sect. 3), segments underlyingly specified as Dorsal avoid umlauting due to undominated *V\(_{\mbox{2\{c,d,p\}}}\). This is replicated with the fuller constraint ranking for Pfund [pfʊnt] ∼ Pfunde [ˈpfʊn.də] ‘pound(s)’ (neut.) in (64) and (65) (recall that *V\(_{\mbox{2\{c,d,p\}}}\) is a containment-based generalized markedness constraint and hence also sensitive to phonetically unrealized Place features as  in (64a,b)):

in (64a,b)):

-

(64)

No umlaut ---- stable [u]: singular (Pfund)

-

(65)

No umlaut ---- stable [u]: plural (Pfunde)

(66) and (67) now show the crucial case of covert umlaut for the vowel in Kind ∼ Kinder which by assumption is specified neither for lingual Place nor for Labial. Whereas undominated Fth Lab has blocked unrounding for Grund ∼ Gründ-e above, here it excludes rounding ([u] and [y]) in both the singular and the plural (66b,d), (67)[b,d]. Since a back unrounded vowel is also blocked (by *{ɯ,ɤ}, (66c), (66c)), [i] is the output in both singular and plural, the only difference being that the Coronal feature in the plural form originates in the suffix whereas it is epenthetic in the singular:

-

(66)

Covert umlaut configuration: singular (Kind)

-

(67)

Covert umlaut configuration: plural (Kinder)

Crucially, under the constraint ranking assumed, all possible underspecification patterns for Coronal, Dorsal and Labial in full vowels result in an attested empirical pattern, as summarized in (68). Maximal specification for Lab and either Cor and Dor will lead to consistent realization of the underlying form due to undominated Fth Lab and *V\(_{\mbox{2\{c,d,p\}}}\) (68a,b). Vocalic markedness produces the same output for [+high-low DOR] (68c) as I have shown in tableaux (64) and (65). (68d) is the standard umlaut pattern for high vowels derived in tableaux (62) and (63). I assume that nouns such as Wind [vɪnt] ∼ Wind-e [ˈvɪn.də] ‘wind(s)’ (masc.) and Schiff [ʃɪf] ∼ Schiff-e [ˈʃɪ.fə] ‘ship(s)’ (neut.) are simply underlyingly specified as Coronal. Due to *V\(_{\mbox{2\{c,d,p\}}}\) the floating  of the plural suffix cannot associate to the root vowel node. As a consequence, Schiffe blocks evacuation of

of the plural suffix cannot associate to the root vowel node. As a consequence, Schiffe blocks evacuation of  to the root node and association of

to the root node and association of  to its VPlace node and the plural suffix is spelled out as [ə] as in non-umlauting Schaf ∼ Schafe above (tableaux (44)), whereas (68f) (Kind ∼ Kinder, tableaux (66) and (67)) is completely parallel to overtly umlauting Rad ∼Räder (tableaux (43)) which licenses the ‘chain shift’ of Coronal and Pharyngeal, i.e. umlaut and the spellout of the affix segment as -ɐ:

to its VPlace node and the plural suffix is spelled out as [ə] as in non-umlauting Schaf ∼ Schafe above (tableaux (44)), whereas (68f) (Kind ∼ Kinder, tableaux (66) and (67)) is completely parallel to overtly umlauting Rad ∼Räder (tableaux (43)) which licenses the ‘chain shift’ of Coronal and Pharyngeal, i.e. umlaut and the spellout of the affix segment as -ɐ:

-

(68)

Different degrees of V-underspecification (non-low vowels)

Let us finally return to low vowels. In Sect. 4.2, I have argued that Ident Phar is undominated. Hence low stem vowels specified for this feature are immune to umlaut as shown in (69) and (70):

-

(69)

No umlaut with low vowel: stable [a]: singular (Schaf)

-

(70)

No umlaut with low vowel: stable [a]: plural (Schafe)