Abstract

This article revisits the long-standing issue of the alternation between wh-in-situ and wh-ex-situ questions in French in the light of diglossia and cross-linguistic data. A careful preliminary examination of the numerous wh-structures in Metropolitan French leads us to focus on Colloquial French, which undoubtedly displays both wh-in-situ and wh-ex-situ questions. Within this dataset, wh-ex-situ questions without the est-ce que ‘is it that’ marker are more permissive than in-situ regarding weak-islandhood and superiority. In a Relativized Minimality framework, we suggest that wh-ex-situ items bear an additional feature, which permits them to bypass these constraints. Colloquial French is thus a wh-in-situ language that allows for wh-ex-situ under specific conditions, like other wh-in-situ languages. Hence we argue against free variation and claim that wh-fronting is not driven by a wh-feature, but by another feature. Exploring the contexts where wh-ex-situ is licensed, we highlight a type of non-exhaustive contrast specific to questions, namely Exclusivity, and provide a formalization. The article therefore also contributes to the larger debate on information structure in questions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Preliminaries: Optionality?

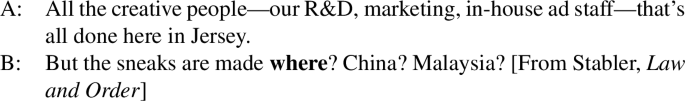

The present article discusses the common idea that wh-ex-situ is the normal/default way to form a wh-question in Colloquial Metropolitan French and argues that wh-ex-situ is actually more marked than wh-in-situ.Footnote 1 In tackling this question, we shall contribute to the more general problem of information structure in questions, which is notably thorny and yet understudied (Beyssade 2006; Constant 2014; Engdahl 2006).

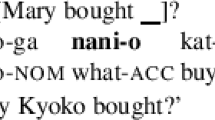

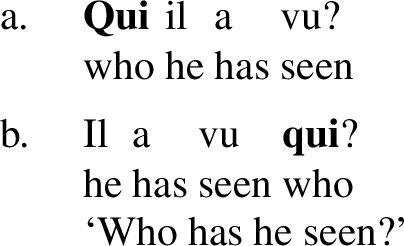

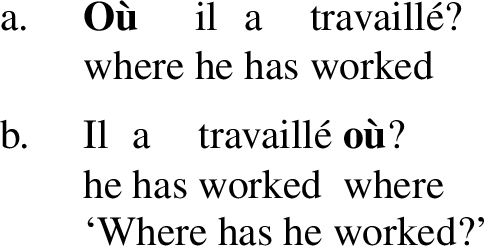

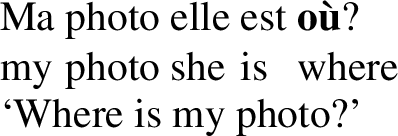

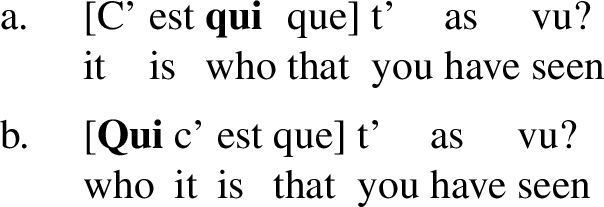

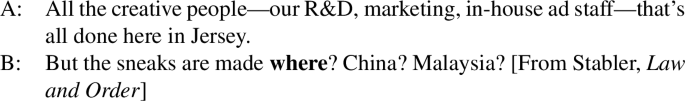

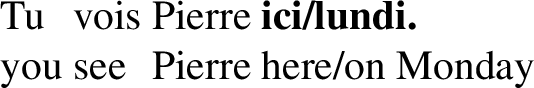

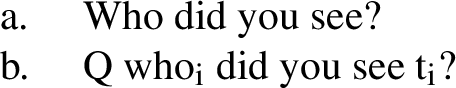

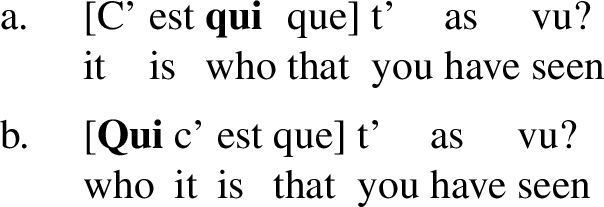

Metropolitan French is a ‘mixed language’ in the typological literature on wh-positions.Footnote 2,Footnote 3 This language hence features both in-situ and ex-situ wh-phrases (whPs), as illustrated in (1) and (2) with an argument and an adjunct, respectively

-

(1)

-

(2)

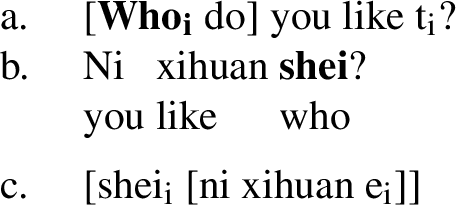

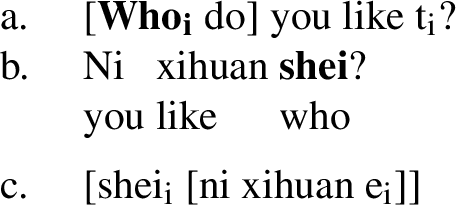

The received view is that speakers set a binary parameter in relation with the checking of the inherent wh-feature on the wh-item. This parameter can be described as overt vs. covert wh-movement (e.g., English in 3a vs. Chinese in 3b; Huang 1982) or unobligatory (English) vs. obligatory (Chinese) formation of a prosodic chunk between the wh-item and the verb (Richards 2010, 2016; among other analyses). In both approaches, Chinese Logical Form (in 3c) is identical to English surface form (in 3a) with regard to wh-placement.

-

(3)

In this binary perspective, Colloquial French is deemed to follow the same pattern as English, and wh-in-situ questions are seen as marked, which entails that they have received most of the attention.Footnote 4 However, works like Baunaz (2011, 2016) and Vergnaud and Zubizarreta (2005) have shown that wh-in-situ questions actually come in several guises, one of which is only very slightly marked.Footnote 5Wh-ex-situ questions must then be either an optional, freely available variant (of at least one of the varieties of wh-in-situ questions) or a different type of wh-question. Surprisingly, wh-ex-situ are understudied and still await more careful analysis, which we intend to provide here (but see Baunaz 2011:223, fn. 229).

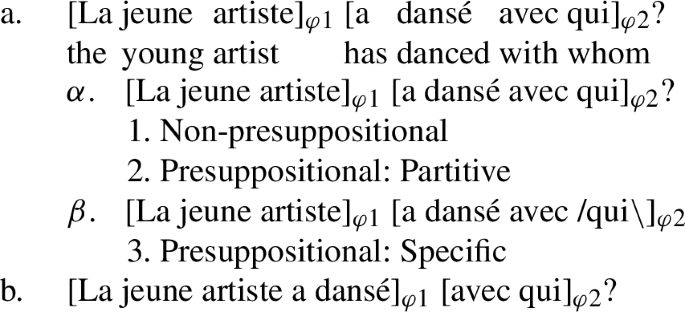

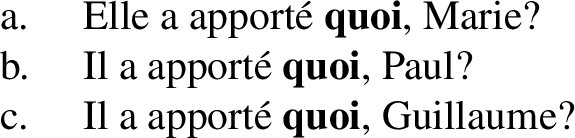

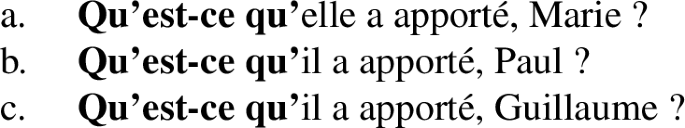

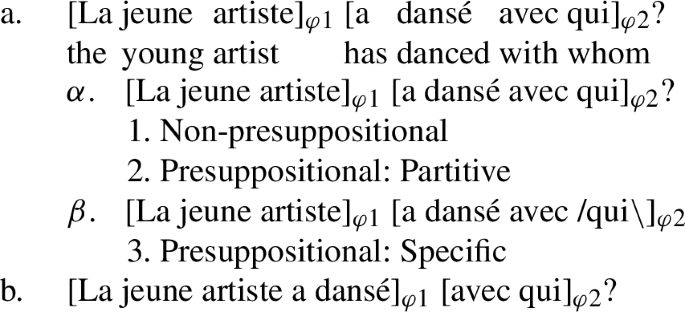

We shall be restricting our attention to the syntactic structures displayed in (1) and (2), a stand that calls for explanation, given the many other options available in French (Mathieu 2009). First, in order to be relevant, the ex- and in-situ counterparts examined in this article need to be strict prosodic minimal pairs, which leads us to exclude some types of wh-in-situ questions. According to Martin (1975) and Vergnaud and Zubizarreta (2005), wh-in-situ questions come in two prosodically distinct guises, as in (4a-b) (their 3).Footnote 6 Both can be divided into two prosodic phrases φ1 and φ2. However, the first guise (a) has a rising accent on the subject DP (φ1) and a falling accent on the VP (φ2), whereas the second one (b) has a rising accent on the subject DP+V (φ1) and a falling accent on the PP containing the wh (φ2). The latter has an emphatic flavor.

-

(4)

Moreover, type (4a) is also reported to come in two prosodic types, α and β, the latter displaying an additional rise-fall accent on the wh (Baunaz and Patin 2011). Finally, α and β correspond to three different interpretations (1, 2, 3; Baunaz 2011, 2016).Footnote 7 In order to control for the prosodic facts, we shall ignore the subtle difference between 1. and 2. (as in Baunaz and Patin 2011) and use the least-marked type of wh-in-situ questions (aα) to contrast it with wh-ex-situ. The exceptional types (aβ) and (b) will be mentioned only when needed in order to avoid confusion.Footnote 8 We shall informally refer to (aβ) and (b) as ‘stressed wh-in-situ.’ Finally, we shall not elaborate on the final, interrogative intonation in wh-in-situ questions, which was argued to be like yes/no questions along with a presuppositional analysis of these questions (Cheng and Rooryck 2000; Déprez et al. 2013). Indeed, there is variation among speakers (Déprez et al. 2012; Tual 2017), and this type of intonation seems to concern only a variety of French in which wh-in-situ is excluded from subordinate clauses, which is not the case of the one under study here (see also Baunaz 2011:43). Second, French allows variation in its wh-ex-situ questions with the possible, additional insertion of est-ce que ‘is it that’. In this contribution, in order to work from minimal pairs, we shall only consider the ex-situ qu’est-ce que ‘what is it that’ in contrast with the in-situ quoi ‘what’. The other combinations (e.g., où est-ce que ‘where is it that’), which are quite rare in adult, oral corpora, are left for further investigation.Footnote 9

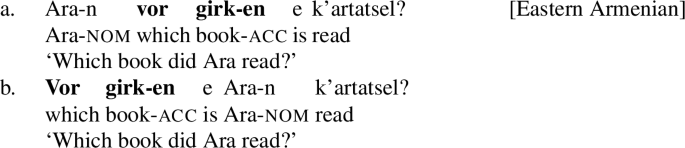

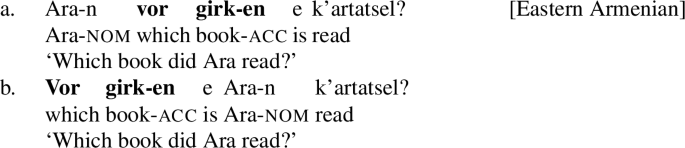

This said, the article will argue against optionality between wh-ex-situ and in-situ questions, and will claim that French is actually a wh-in-situ language that sometimes allows for wh-ex-situ, under specific conditions, much like other wh-in-situ languages. Such an alternation is well documented in languages across the world and is illustrated in (5) with Eastern Armenian (Megerdoomian and Ganjavi 2000, glosses as in original).

-

(5)

The unmarked way to form a wh-question is (5a). (5b) is an instance of fronting or scrambling. This type of alternation is widespread and is also attested in American Sign Language (Abner 2011), Korean (Beck 2006; Beck and Kim 1997), Mandarin Chinese (Hoh and Chiang 1990, Cheung 2008), some Northern Italian Dialects, including Trevigiano (Bonan 2019), Persian (Megerdoomian and Ganjavi 2000), and Turkish (Özsoy 2009), to name but a few.

A reasonable claim is that this additional movement of a wh-item in wh-in-situ languages does not come for free. However, no or little motivation has been given for these frontings and scramblings in the past literature. Based on child and adult data, we shall aim to show that French behaves like a wh-in-situ language, and to provide a motivation for the whP not to be in-situ, but ex-situ. In our view, the movement is triggered by a focus feature that can be defined as Exclusive, and for which we propose a semantics.

The article is organized as follows: In Sect. 2, we define the contours of Colloquial French, as opposed to Standard French, by relying on the Diglossic Hypothesis. This point is crucial because not all patterns of wh-questions belong to the same variety. Section 3 then examines in-situ and ex-situ, simple and multiple questions in order to test and compare their sensitivity to constraints on wh-movement. Since (at least some) wh-in-situ questions appear as the unmarked way to form wh-questions in Colloquial French, the semantic properties of wh-ex-situ are further investigated in Sect. 4 in order to uncover a possible and common trigger to wh-fronting in this language. Section 5 then formalizes the suggested trigger, namely Exclusivity, a contrastive operator. Finally, we draw some conclusions and suggest leads to further research in Sect. 6.

2 Defining Colloquial French

The study must consider only one variety of Metropolitan French in order to explain the in-situ/ex-situ alternation. Thus, it is crucial to start with a definition of Colloquial French (the subject of our study), in contrast with Standard French (which we shall leave aside).We claim that the diglossic hypothesis provides touchstones for determining which wh-structures belong to one or the other variety, Subject-Clitic inversion (henceforth SCLI) being particularly relevant to the issue. Note that no variety possesses all the patterns of wh-questions.

2.1 The diglossic hypothesis

Syntactic variability has been widely acknowledged in Metropolitan French. Three main areas of variation have been thoroughly examined in adult speech: subject clitics, negation and interrogative structures (Ashby 1977a,b, 1981; Coveney 2002, 2003; Lambrecht 1981; Pohl 1965, 1975, among others). Two different hypotheses currently account for this variability, that is, Variationism and Diglossia.Footnote 10 The debate mainly hinges upon the number of grammars that a French native speaker actually handles. The variationist approach suggests that the different variants of French belong to the same grammar, and that variation is due to social and stylistic factors (Beeching et al. 2009; Blanche-Benveniste 1997; Coveney 2011; Gadet 2003, among others). There are no grammatical constraints on the combinations of variants in this unique grammar (Rowlett 2011). In contrast, the diglossic hypothesis, which builds on Ferguson’s (1959) work, suggests that a variant of French belongs to one of two cognate, but nevertheless distinct, grammars (Barra-Jover 2004, 2010; Massot 2008, 2010; Massot and Rowlett 2013; Zribi-Hertz 2011). Variation is explained by the coexistence of two grammars in the minds/brains of the French native speakers. Let us call these two grammars G1 and G2.

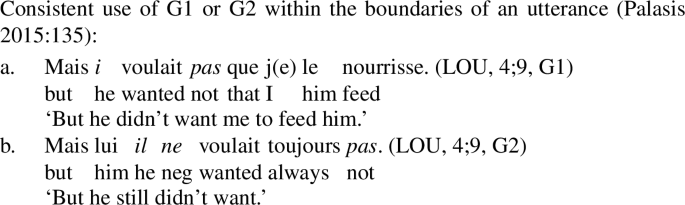

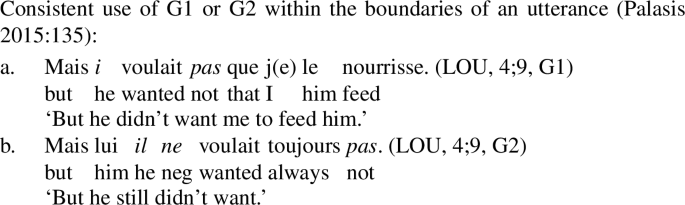

In the framework of Diglossia, Massot (2010) examined the combination of six binary variables in spontaneous adult data, for example, simple negation pas ‘not’ (G1) vs. discontinuous negation ne…pas (G2), and the use of the third-singular pronoun on ‘one’ (G1) vs. first-plural pronoun nous ‘we’ (G2). The author reported that his informant never code-switched within the boundaries of his clauses, and hence argued in favor of the strong grammatical constraint that a characteristic of one grammar (e.g., G1 pas or on) cannot co-occur with a characteristic of the other grammar (e.g., G2 ne…pas or nous) within the same clause. Thus, a sentence with code-switching (e.g., *on ne gagnait pas énormément ‘one did not earn much’) is not expected within the diglossic hypothesis (Massot 2010:100).

Other variants in adult French are also well documented and the most emblematic topic is probably the morpho-syntactic status of subject clitics, notably il ‘he’ (Ashby 1984; Culbertson 2010; De Cat 2005; Kayne 1975; Legendre et al. 2010; Morin 1979; Rizzi 1986; Roberge 1990; Zribi-Hertz 1994, among others). In G1, il takes the elided form i- before consonant-initial constituents (e.g., i-travaille ‘he works’), is analyzed as a preverbal agreement marker, and hence cannot undergo SCLI. In contrast, in G2, il is never elided and, as a proper pronoun, can appear pre- or postverbally (e.g., il travaille, travaille-t-il).

More evidence in favor of the diglossic approach has been adduced in studies in acquisition. Indeed, the two grammars are assumed to emerge subsequently, the first one being acquired at home and the second being mainly learned ‘by the means of formal education’ (Ferguson 1959:331). Preschool children are therefore expected to initially handle G1 only and develop G2 later. Palasis (2013, 2015) highlighted this asynchrony in kindergarten data, and showed that children consistently used the items of the same grammar within the boundaries of their utterances, as detailed in Table 1 and instantiated in (6).

-

(6)

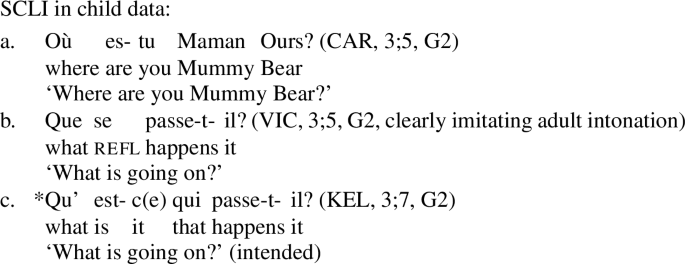

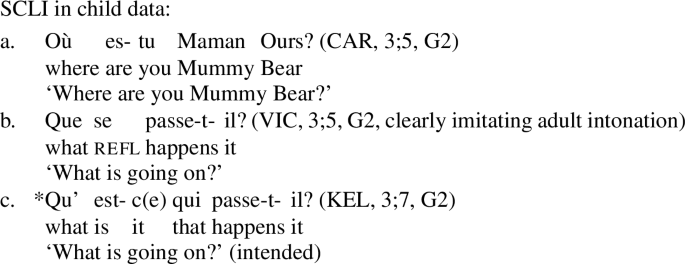

SCLI is rare in child questions (0.1% of the interrogatives with a subject clitic) and, when instantiated, not always fully mastered, as seen in (7c).Footnote 11

-

(7)

These facts are consistent with the diglossic hypothesis that French children start with G1 (no SCLI) and develop G2 (SCLI) only later.

2.2 Diglossia and wh-questions

Let us now place wh-questions in the picture by determining which wh-interrogative structures belong to G1 and G2. SCLI, which is found only in G2, is particularly relevant to the matter, as illustrated in Table 2.

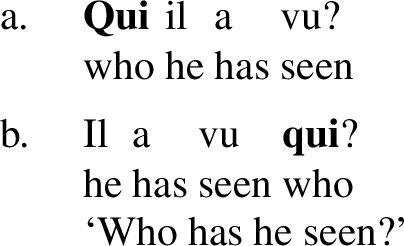

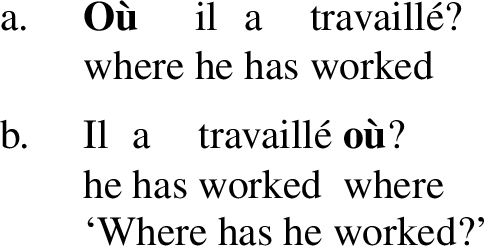

Table 2 highlights that G1 displays both in-situ (in a) and ex-situ wh-positions (in b). In contrast, we have no positive evidence in our child dataset that G2 also features wh-in-situ, that is, there are no occurrences combining a non-elided clitic and an in-situ wh-word (e.g., il travaille où? ‘he works where’). Therefore, no conclusion can be drawn with regard to variation of the wh-position in G2, which at this stage may or may not be described as an exclusively wh-ex-situ language, on a par with English.Footnote 12 We shall assume that G1 is Colloquial French and G2 Standard French.

In this section, we observed that Colloquial French is the only variety of French that undoubtedly features an in-situ/ex-situ alternation and that wh-ex-situ questions with SCLI belong exclusively to Standard French (Table 2). Consequently, we shall concentrate on Colloquial French in the remainder of the paper and leave Standard French for further research.Footnote 13

3 Evidence that wh-in-situ questions are unmarked questions

In this section, we compare wh-in-situ and wh-ex-situ questions, provide evidence that wh-in-situ is the unmarked counterpart of wh-ex-situ, and conclude that Colloquial French displays only covert wh-movement. In Sect. 3.1, we examine simple and multiple questions with regard to strong and weak islands. This leads us to adopt the theoretical framework of Relativized Minimality in Sect. 3.2. Section 3.3 then widens the investigation to Superiority. These tests highlight when in-situ is either unacceptable or degraded compared to ex-situ, and hence enable us to pinpoint the feature(s) ex-situ wh-items carry, contrary to their in-situ counterparts.

Before we proceed however, a note on D-linking and the French counterpart of which is in order. The demonstration will rely on bare whPs only and thus discard quel ‘which’ whPs for three reasons. First, French quel whPs are ambiguous between ‘which (book)’ and ‘what (book)’ and, therefore, cannot be used straightforwardly to test D-linking. Second, French has an unambiguously D-linked wh-item, namely lequel ‘which one.’ But French lequel needs to be more strongly related to the context than English which. Pending more research on this topic, we decide to leave it aside. Finally, the best reason is that bare whPs can be contextually D-linked, as already noted in Pesetsky’s (1987) seminal paper. This means that when comparing a ‘which’ phrase with a bare whP, we can never be sure that we are comparing a D-linked and a non-D-linked whP. Consequently, in order to exclude possible D-linking effects, we shall contrast only bare whPs in strongly controlled contexts.

3.1 Islands

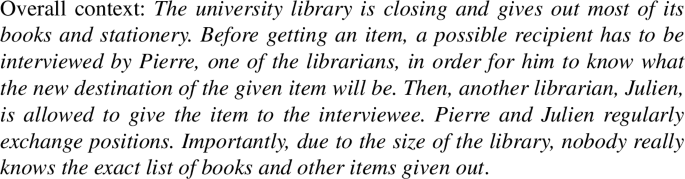

In wh-ex-situ languages, some configurations are degraded when the whP is in the (matrix) CP-domain and in a relation with certain types of embedded clauses or after a negative operator. This degradation is assessed when the movement from the lower to the higher position is blocked. These configurations thus provide good tests to check whether movement takes place overtly or covertly. They are metaphorically named ‘islands,’ and can be either ‘strong’ (i.e., they block all types of extractions) or ‘weak’ (i.e., some extractions are possible; Cinque 1990; Ross 1967; Szabolcsi 2006). Adjuncts are well-known strong islands, as in (9), and negative operators are examples of weak islands, as in (17) and (18). In each configuration, wh-in-situ is provided in (a) and wh-ex-situ in (b). As mentioned earlier, context is crucial to the analysis. (8) sets an overall context for the examples in Sect. 3 and is fleshed out when necessary.Footnote 14

-

(8)

3.1.1 Strong islands

In this section, we shall see two crucial points: wh-in-situ involves covert movement; wh-ex-situ is more constrained, a point that we shall verify in the next section as well.

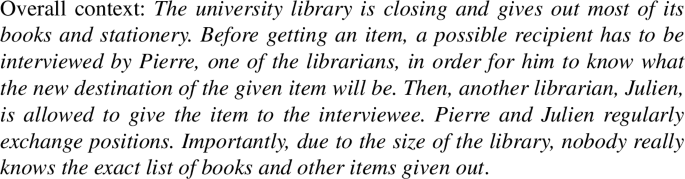

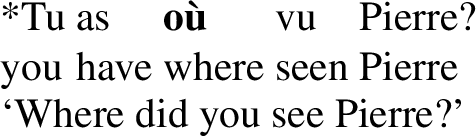

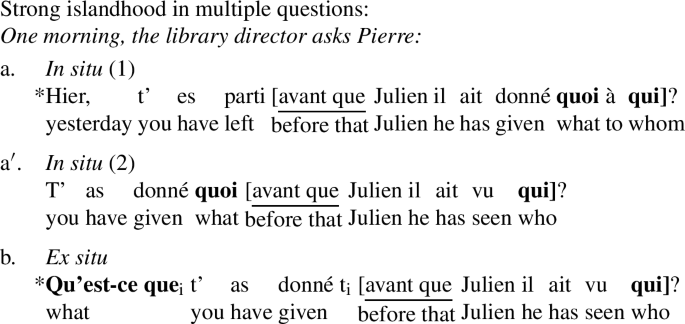

Examples (9) display strong, adjunct islands (i.e., avant que ‘before that’ clauses):

-

(9)

In these simple questions, both in-situ and ex-situ whPs are unacceptable. The reason for b’s unacceptability is obviously syntactic: qui is prevented from moving out of the avant que clause. Crucially, we also take a’s unacceptability as indication that qui normally covertly moves to check the wh-feature, which it cannot do here because there is no possible escape from the island. In fact, contrary to weak islands (see fn. 24 and Sect. 3.1.2), all accounts of adjunct, strong islands we are aware of are dependent on the whP moving out of the clause, be it in terms of subjacency/barriers (Huang 1982; Chomsky 1976), phases (Müller 2010), or the eventive structure of the whole sentence (Truswell 2007).Footnote 15 The relevant LF of both a and b is schematized in (10).

-

(10)

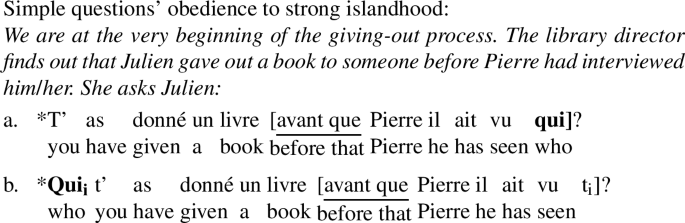

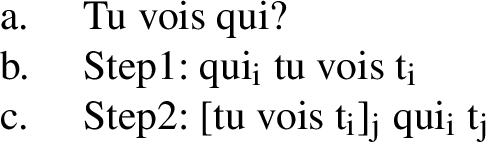

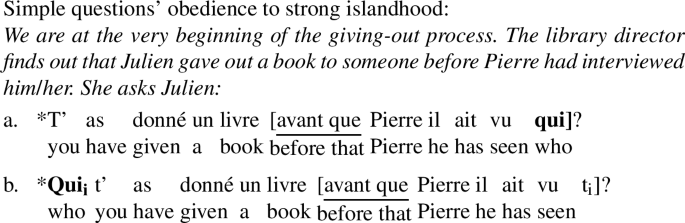

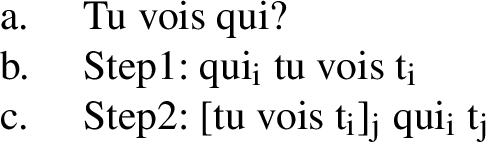

It is time to pause here to consider another very influential explanation, namely the hypothesis of an overt movement of the whP followed by a remnant-IP movement (Munaro et al. 2001, and followers). A simple sentence like (11a) is derived through the steps described in b and c.

-

(11)

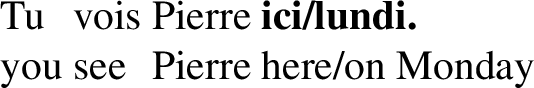

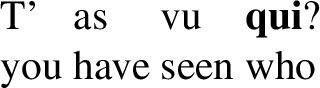

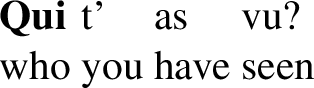

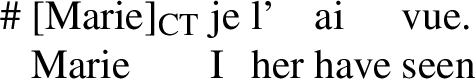

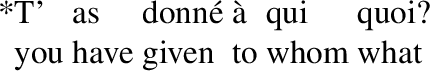

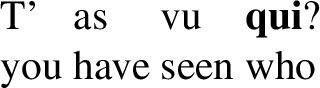

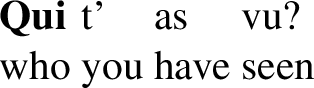

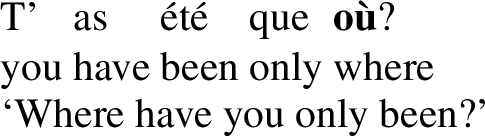

According to this hypothesis, (9a) is ruled out because the strong island blocks the wh-movement required in Step1. As appealing as it may be, this theory will not be retained here, mainly because it does not seem to extend to Colloquial FrenchFootnote 16 (see Bonan 2019; Etxepare and Uribe-Etxebarria 2005; Manzini and Savoia 2011; Poletto and Pollock 2015; Uribe-Etxebarria 2003, for more details and tests on Spanish and Italian dialects; and Bonan 2019; Baunaz 2011; Cheng and Rooryck 2000; Mathieu 2002, for a stand similar to ours on Colloquial French). Indeed, the theory predicts that the wh-term should always be rightmost (i.e., the “sentence-finality requirement”), whereas Colloquial French displays sentences like T’as vu quoi hier? ‘what did you see yesterday?,’ T’as donné quoi à Paul? ‘what did you give to Paul,’ in which the prosodic pause signaling deaccenting of hier and à Paul is optional after quoi. Another option would be to assume several derivational steps topicalizing hier or à Paul, then fronting the wh-items before the remnant movement,Footnote 17 but these steps would be loosely motivated.

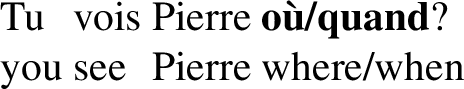

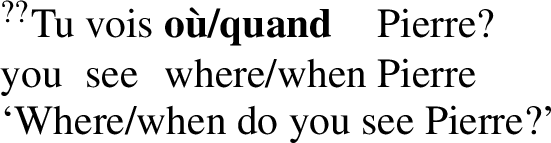

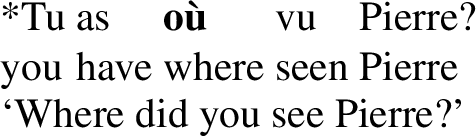

Moreover, Bonan (2019) entertains the idea that patterns like (14) could be evidence for a French wh-position of a third type, namely intermediate, IP-internal, above vP, as in Trevigiano.Footnote 18

-

(12)

-

(13)

-

(14)

-

(15)

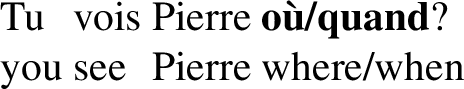

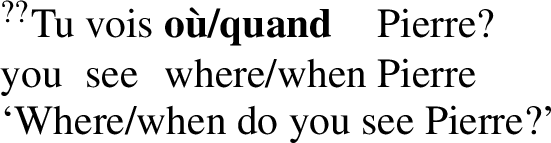

Time and location adjuncts appear clause-finally in French as evidenced in (12), which is also possible for the corresponding wh-terms in (13), but not obligatorily if we consider (14). In (14), où/quand have moved to an IP-internal position. However, Baunaz (2011) points out the optionality and degradation of this kind of example, and the specific semantic (strongly presuppositional) and prosodic conditions under which this kind of sentence is marginally acceptable. Bonan (2019) concludes that (14) is better seen as an instance of non-featurely-driven scrambling. This is all the more plausible given that an IP-internal movement would also derive a sentence like (15), where où would ungrammatically surface between the T (auxiliary as) and v/V (past participle vu). Be that as it may, its presuppositional character and its specific prosodic conditions exclude this intermediate wh-position from our study (see 4 and fn. 7).

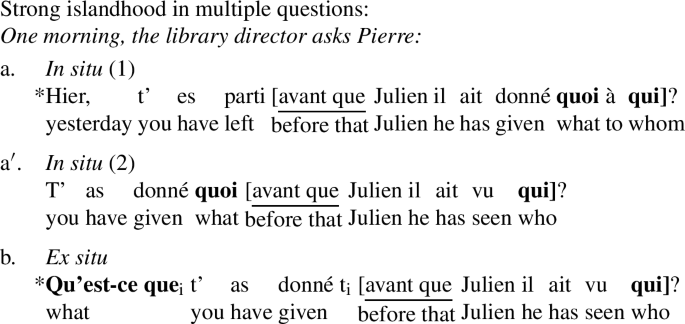

Coming back to the hypothesis that both overt and covert movement must be considered if we want to explain the patterns under examination, multiple questionsFootnote 19 confirm the previous results and take us a step further in hinting at the possibility that wh-ex-situ structures are more constrained than wh-in-situ ones:Footnote 20

-

(16)

While unacceptable when both wh-arguments are in the island in (16a), the sentence becomes better when the matrix verb displays a wh-argument as in (16a′). A possible explanation is that one wh-item in the matrix clause is required (if the other one is trapped in an embedded island) and suffices to covertly check the wh-feature on matrix C, hence freezing the movement of the second wh-item (here qui in the embedded clause).Footnote 21

In contrast with wh-in-situ, strong islandhood blocks ex-situ multiple questions (16b), albeit one of the wh-items is in the matrix. Following what we just saw, this indicates that it is not sufficient that the wh-feature on C is checked by the moved wh. Our hypothesis is that the degradation is due to the necessity for the second wh to move as well, which it cannot do because it is trapped in the adjunct island.Footnote 22 Weak island facts also point towards wh-ex-situ structures involving an additional operation.

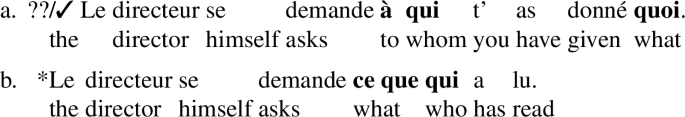

3.1.2 Weak islands

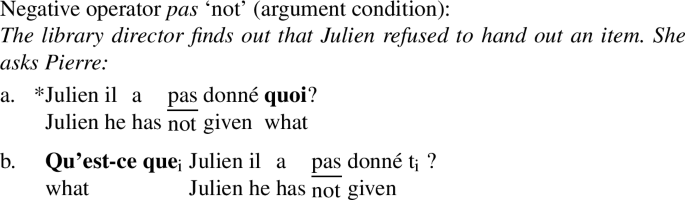

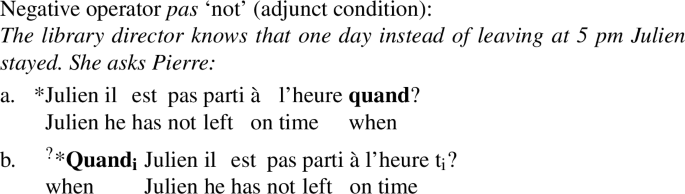

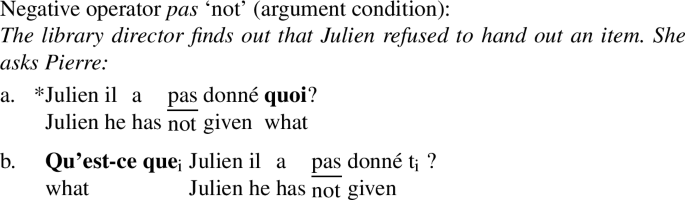

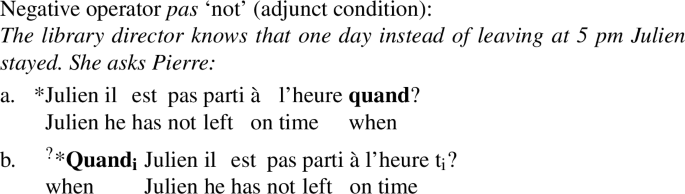

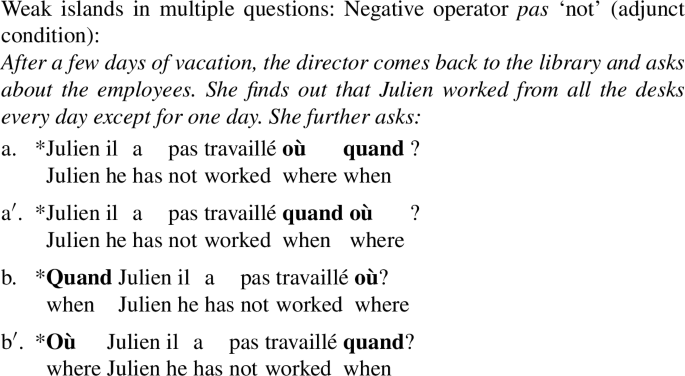

In this section, we show that both syntax (more precisely, Minimality but not Intervention) and semantics (Contradiction) are at play in our weak-island facts. As in the previous section, we give simple and multiple question examples. We illustrate weak-island effects with a negative operator in (17) and (18).Footnote 23

-

(17)

-

(18)

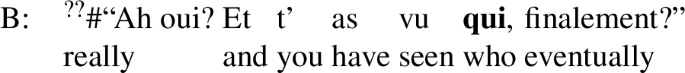

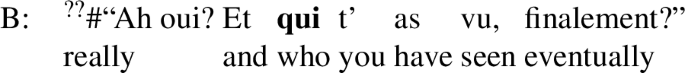

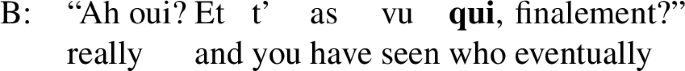

Weak islands are taken to display an acceptability asymmetry between argument and adjunct extractions, which is also reported here for wh-ex-situ questions (17b vs. 18b).Footnote 24 However, the examples are of interest here because wh-in-situ questions do not feature the asymmetry, and are rated as badly for arguments as for adjuncts (a-sentences in 17 and 18). Even if this is not exactly in line with the judgments reported in Baunaz (2011), whose informants tend to accept the configurations represented in (17a) and (18a), Baunaz (2011:44, 60–61) nevertheless notes that they are constantly felt to be degraded with respect to their ex-situ counterparts and that the argument/adjunct asymmetry exists in ex-situ questions only.Footnote 25

This means that the in-situ argument questions in (17a) are probably degraded because of a factor independent from Abrusán’s contradiction theory, which explains why the adjunct questions in (18a-b) are degraded. Importantly, note that the degradation CANNOT be due to an intervention effect, because under current accounts (Beck 2006; Haida 2008; Mayr 2014, and works based on them) intervention effects arise when the LF is as in (19) (intervention between Q and the wh), that is when the wh-item does not move. This is different from what we saw in (10) in Sect. 3.1.1 with covert movement and no possible intervener between Q and the wh (see Beck 2006 building on a reasoning on D-linked multiple questions in Pesetsky 2000).

-

(19)

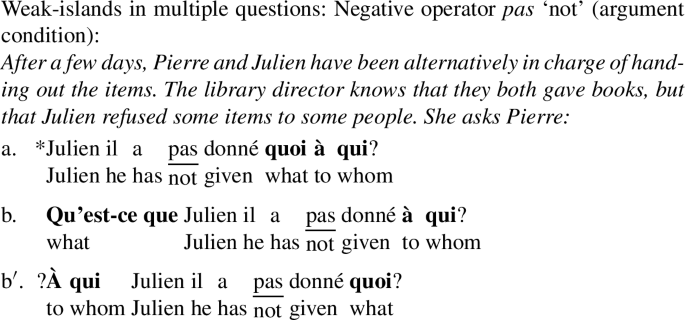

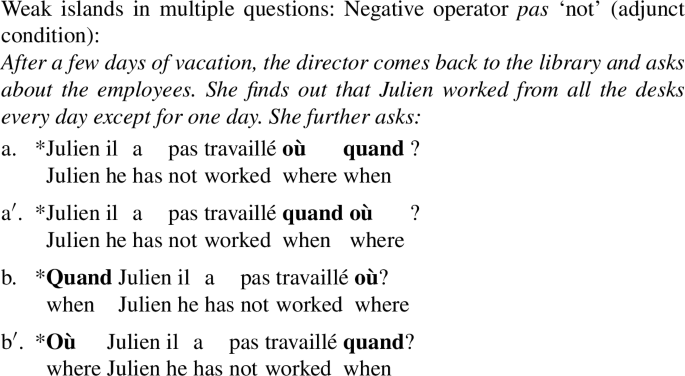

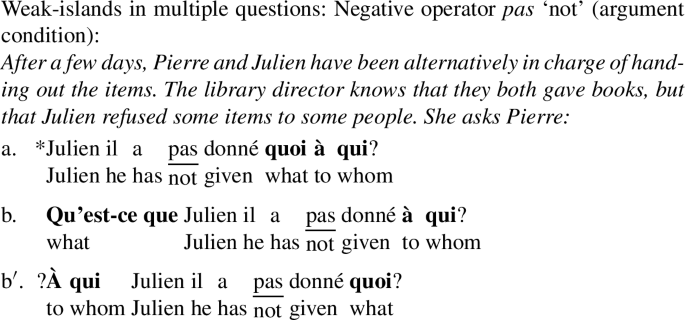

The multiple-question data in (20) and (21) confirm these results:

-

(20)

-

(21)

-

(22)

Multiple ex-situ questions in weak-island contexts are noteworthy in three respects: 1) Like simple questions, they display the argument/adjunct asymmetry, as illustrated in (20b/b′) vs. (21b/b′); 2) Multiple ex-situ questions are better than their in-situ counterparts; 3) They are degraded, however, with respect to simple ex-situ questions in the same contexts (see 17b). Aspect 1) is expected in weak-island situations, where adjunct wh-questions are ungrammatical for independent semantic reasons (see fn. 24). Aspect 3) is unexpected. However, the marginal acceptability of (20b/b′) suggests that the contrast between simple and multiple questions may be due to processing difficulties.Footnote 26

Finally Aspect 2) confirms the observation made on simple questions: French wh-in-situ, but not wh-ex-situ questions are degraded in contexts where Abrusán’s (2014) principle (fn. 24) is not at play, namely when the question bears on an argument. Consequently, the degradation must be attributed to another factor. We follow Baunaz (2016) in positing that a Relativized Minimality effect applies here à la Starke (2001) and Rizzi (2004).

3.2 Relativized minimality

In this section, we explain what Relativized Minimality is and how it can account for the marginality of in-situ questions, but also for the acceptability of ex-situ questions, provided that we posit that the latter are endowed with an additional feature.

In a configuration such as (23) or (24),Footnote 27 Y intervenes between X and Z because they share a feature (or a bundle of features) α. Note that if Y has a richer feature structure (for example bearing both α and β features), the same effect arises, as in (24). In derivational terms (i.e., Minimal Link or Attract Closest Constraint; Chomsky 1995), X probes for an item that bears the feature α, but it meets Y “before” its actual goal Z, Z is therefore left behind, and the derivation crashes. In contrast, (25) displays no effect because the feature structure of X is richer than that of the possible intervener Y. Thus X is allowed to probe for Z past Y to check its feature β.

-

(23)

*Xα … Yα … Zα …

-

(24)

*Xα … Yαβ … Zα …

-

(25)

Xαβ … Yα … Zαβ …

Following Rizzi (2004, 2014) and Baunaz (2011, 2016), we assume that Minimality effects arise between features of the same family. In particular, Wh, Neg, and Focus features belong to the same group of Quantificational features. In this framework, the in-situ sentences in (17a, 20a) are degraded because the C[+wh] head, the wh-in-situ, and the intervening operator (e.g., pas ‘not’) all share the same quantificational feature. Thus, the wh is not attracted to CP at LF and the derivation crashes (see also Beck 1996; Kratzer and Shimoyama 2017 [2001]:139–140).Footnote 28

Put otherwise, wh-in-situ questions in (17) and (20) are ruled out because the wh-items are not endowed with an extra feature that would allow them to escape, namely they only carry a wh-feature. Conversely, the acceptability of (17b) shows that the ex-situ wh-item carries an extra feature. Ex-situ questions like (17b) provide evidence that wh-items can sometimes be extracted from weak islands (e.g., with a negative operator). Under the previous analysis, the extraction is possible only if ex-situ, but not in-situ wh-items bear an additional β feature, as schematized in (25).Footnote 29 The remainder of Sect. 3 will test these assumptions against the Superiority Condition.

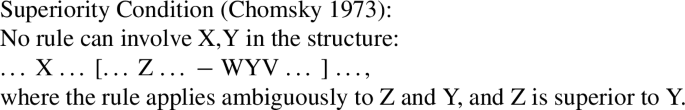

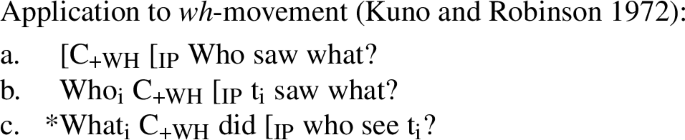

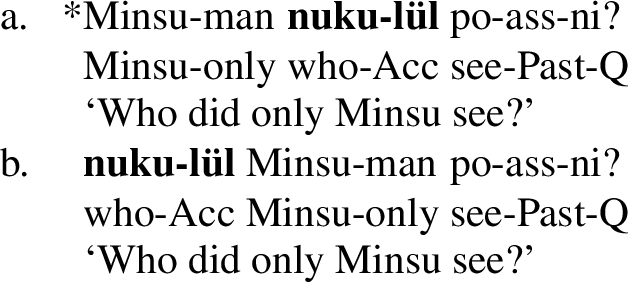

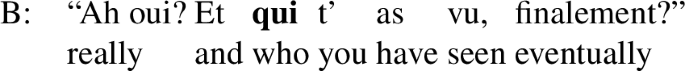

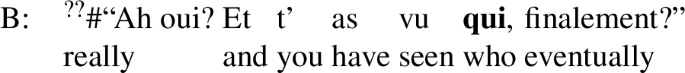

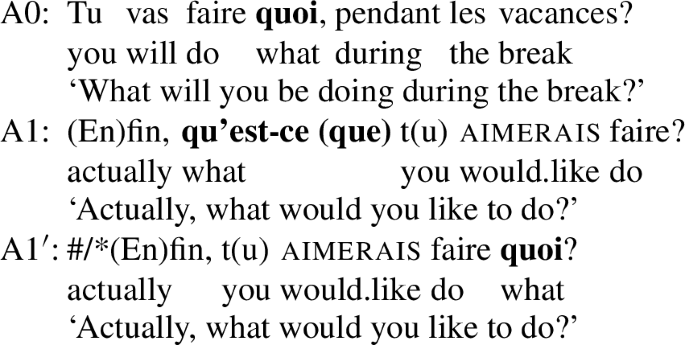

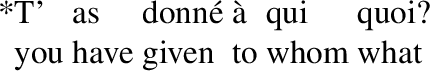

3.3 Superiority

In addition to strong- and weak-island effects, multiple questions allow us to test Superiority, another hallmark of wh-movement (Chomsky 1973). We shall examine in-situ and ex-situ facts separately and show that the former, but not the latter exhibit such an effect.

3.3.1 Superiority and in-situ

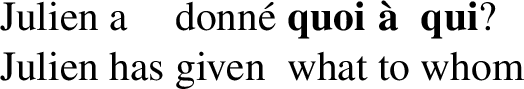

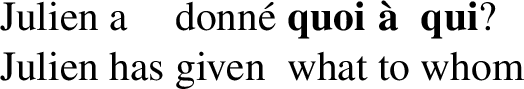

Let us observe the following multiple question, which features two in situ whPs:

-

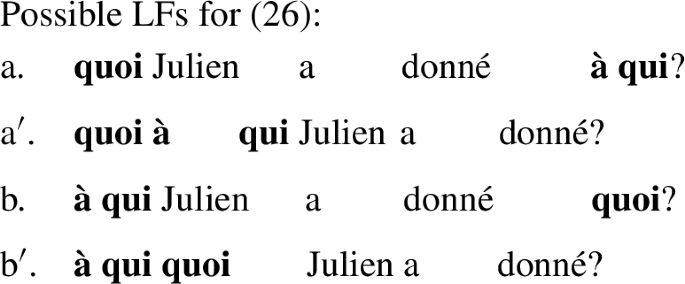

(26)

-

(27)

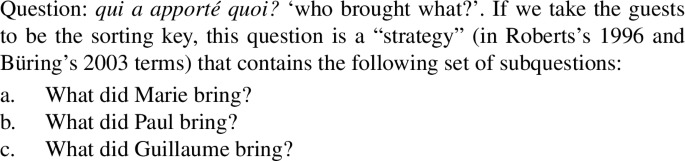

First, it is noteworthy that a single-pair reading for a multiple question like (26) seems to be freely available. However, some speakers also allow for a pair-list reading. Second, two competing LFs are possible in this case: (27a),Footnote 30 in which quoi checks the wh-feature on C and is the sorting key (i.e., the answer is (28a), and (27b), in which à qui checks the wh-feature on C and is the sorting key (i.e., the answer is (28b)). Crucially, (with no wh stressed), (28a) is highly preferred over (b), which suggests that the LF of (26) is (27a).

-

(28)

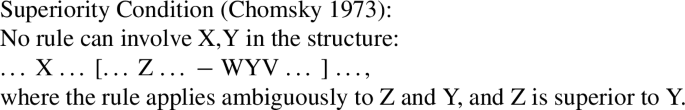

This is reminiscent of the Superiority Condition (29), whose application to wh-movement predicts the ungrammaticality in (30c).

-

(29)

-

(30)

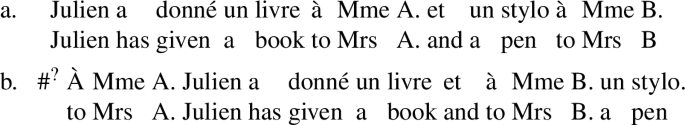

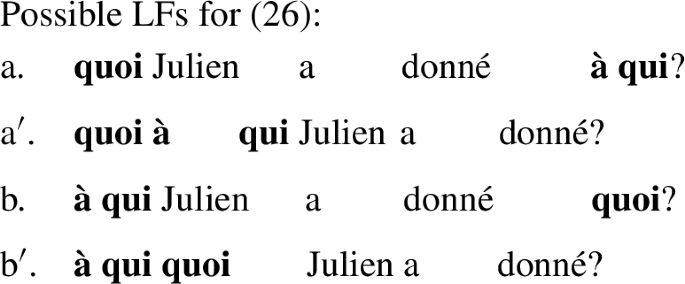

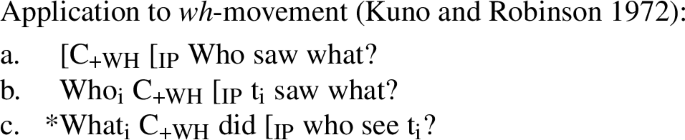

In (30), C[+wh] can attract the closest wh as in (b), but not the farthest, as in (c); (23) illustrates this configuration. Crucially, (c) dramatically improves if what is D-linked (Pesetsky 1987), which could correspond to the configuration in (25).Footnote 31 For Colloquial French, there is further complication though. The fact that D-linking rescues Superiority violation as just mentioned for English can be seen from the embedded-question patterns in (31) (still in the library scenario).

-

(31)

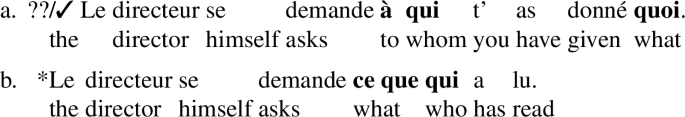

As expected, in (31a), movement of the indirect object à qui over the direct object quoi gives rise to a Superiority effect. However, as in English, (a) improves a lot in a context where à qui and quoi are D-linked, for example if the library director knows that there are only two items to give out (a book and a pen) and only two visitors (say, Maria and Samantha). Crucially, (b), with the object that has moved past the subject, is unacceptable and does not improve in any context. Whatever the reason for that, Superiority tests involving subjects do not apply in French and we shall test Superiority based only on direct and indirect objects.Footnote 32 Thus, (26) and (28) show that Colloquial French wh-in-situ questions are actually sensitive to Superiority.

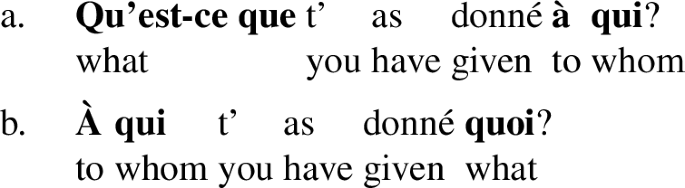

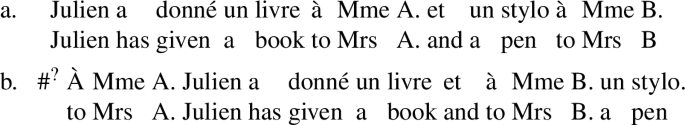

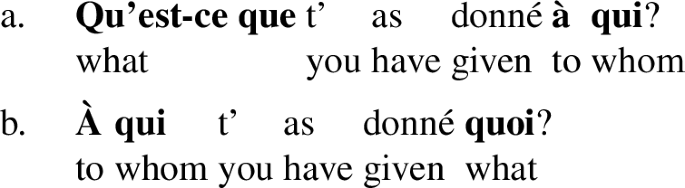

3.3.2 Superiority and ex-situ

Multiple questions with wh-ex-situ lack the Superiority effect, as shown in (32).Footnote 33 Note that speakers manifest a strong preference for a pair-list reading of these questions, even if some of them do not exclude a single-pair reading.

-

(32)

3.4 Intermediate summary

Table 3 summarizes the facts observed in Sect. 3 with regard to islands, Superiority and interpretation. It shows that wh-ex-situ questions differ from in-situ ones in their weaker sensitivity to weak islands and Superiority, properties we attributed to a specific, additional property, which we shall discuss in Sect. 5 (the difference between single-pair and pair-list readings is touched upon in conclusion).

Property A shows that both wh-in-situ and wh-ex-situ questions involve movement. Property B shows that covert movement in wh-in-situ questions is more restricted than overt movement in wh-ex-situ questions. Property C shows that (covert) movement in wh-in-situ questions is in fact wh-movement. On the other hand, weaker sensitivity to weak islandhood and lack of Superiority effect point to a movement of a different nature for wh-ex-situ (see configuration 25). Economy and parsimony also dictate such a conclusion. Since covert movement checks the wh-feature, we conclude that Colloquial French is a wh-in-situ language and that another type of feature is necessary to trigger overt movement.

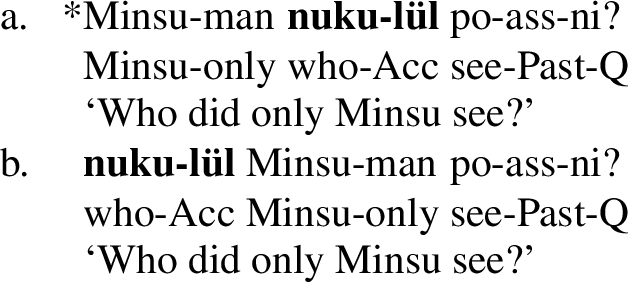

This is reminiscent of the alternation mentioned in Sect. 1 with wh-ex-situ questions analyzed as more marked than wh-in-situ questions based on the cross-linguistic observation that when a language has the parameter ‘(unmarked) wh-in-situ,’ it also displays marked, overtly-moved counterparts via fronting, as in Armenian in (5b) (Megerdoomian and Ganjavi 2000), or via scrambling, as in Korean in (33) (Beck 2006, glosses as in original).

-

(33)

Uncovering the content of the markedness assumed for wh-ex-situ in Colloquial French will be the goal of the remainder of the article. Our task is to clarify the properties of the additional feature advocated in Sect. 3.2 in the frame of Relativized Minimality. Wh-fronting without wh-movement is not a new idea though. Bošković (2002) attributed movement to focus in multiple wh-fronting languages, such as Bulgarian, and Hamlaoui (2010, 2011) tied wh-fronting and focus together in French in an OT framework. We shall agree with these proposals in Sect. 4, and elaborate on Focus in Sect. 5.

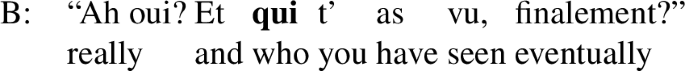

4 Semantic properties of wh-ex-situ questions: Acquaintance with contrast

This section aims to clarify which contexts license wh-ex-situ questions in order to uncover their semantics in Colloquial French. We shall examine three contexts where wh-ex-situ are possible and (unstressed) in-situ impossible. First, wh-ex-situ is acquainted with contrast in exclusive-pairing contexts in child speech (Sect. 4.1) and explicitly contrastive scenarios in adult speech (Sect. 4.2). Note that, in these contexts, contrast on other elements in the question is just a hint at the contrast on the whP. Second, an exclusive selection in a set also triggers wh-fronting (Sect. 4.3). It should be emphasized that stressed wh-in-situ often (though probably not always) seems to appear in free alternation with wh-ex-situ in these situations. The emphasis that goes along with stress also points towards focus. Stress must then be carefully controlled for when evaluating the in-situ examples.

4.1 Exclusive pairing in child speech

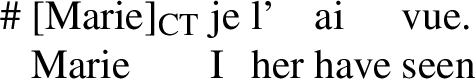

Let us start with child speech, which offers the clearest patterns. In our corpus (detailed in fn. 11), children often ask questions out of the blue, as in (34). The situation is as follows: The child (WIL, 2;10.18) is playing, stops, turns to the adult, and asks the question. These questions feature in-situ wh-words.

-

(34)

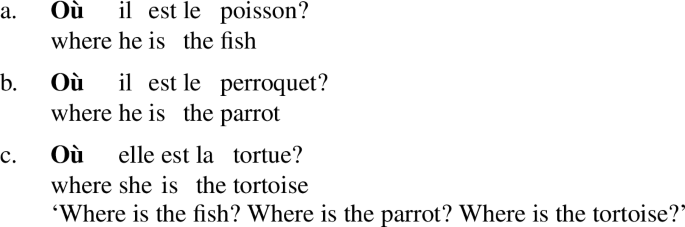

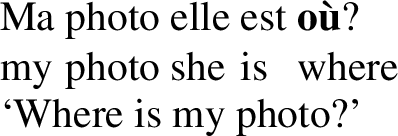

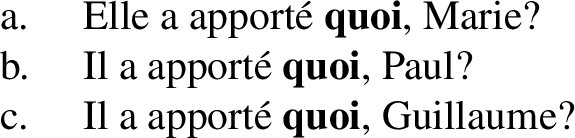

Nevertheless, the corpus also displays ex-situ wh-questions, as in (35), uttered in a row by the same child (MAS, 2;7.5):

-

(35)

In (35), the child was given a board with six animal pictures to match with six individual cards, which means that we have two sets of items, each member of which has a unique correspondent in the other set. In other terms, we have a mapping of the member of a set onto the member of another set. Moreover, the position of an item is only understandable with respect to another one, namely in contrast with another one. In our view, this contrast triggers the fronting of the wh-word où ‘where’ because it requires information about the relative position of the card on the board.Footnote 34

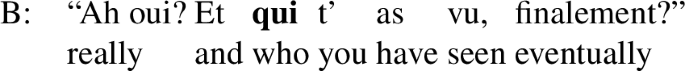

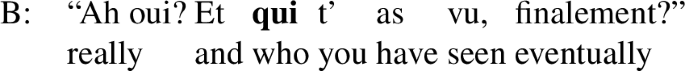

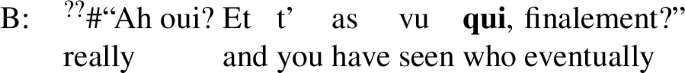

4.2 Explicitly contrastive contexts

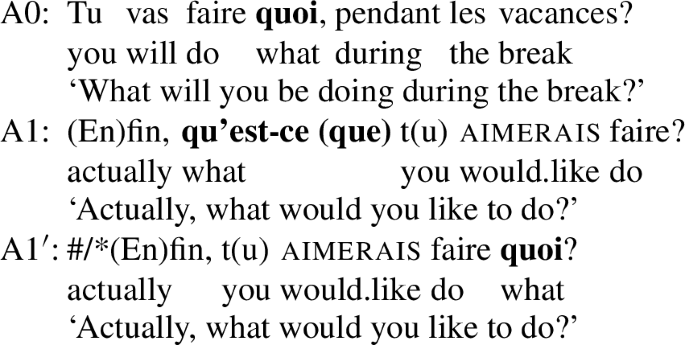

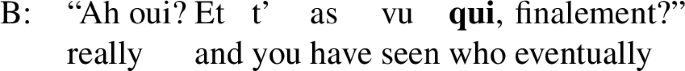

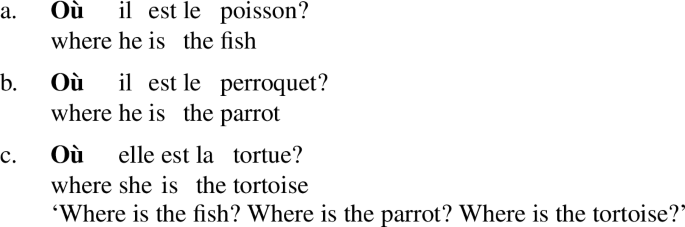

Hamlaoui (2011:fn. 22) noted that explicit contrast triggers obligatory wh-ex-situ questions in adult French. We reproduce the author’s minimal pair A1/A1′Footnote 35 in (36).

-

(36)

Hamlaoui (2011) considered the relationship between modal verbs and the in/ex-situ alternation and convincingly argued that modal verbs such as tu aimerais ‘you would like’ do not favor wh-fronting per se. They favor fronting only when they are contrastively focused, as in A1, where aimerais ‘would like (to do)’ is focused in contrast with the preceding verb vas ‘will (do)’ in A0.Footnote 36 We observe that the speaker wants to identify an object (what the addressee would like to do), whose identity may be different from that of another object (what the addressee will actually do). Thus, the contrast between aimerais and vas goes along with a contrast between the content of qu’est-ce que in A1 and quoi in A0.Footnote 37

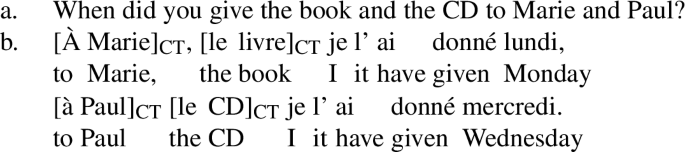

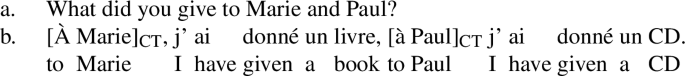

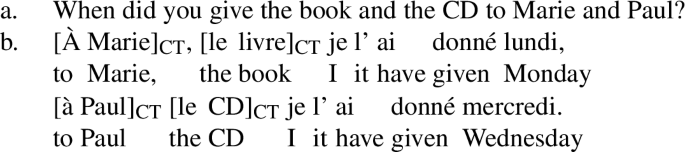

4.3 Teasing apart Contrast on the wh-item and Contrast on the non-wh-part

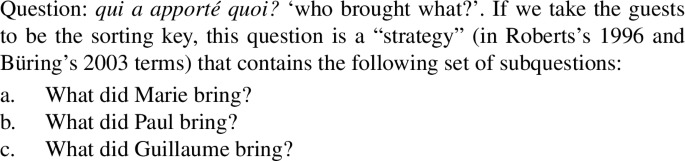

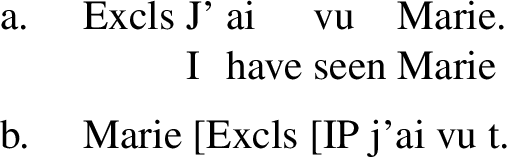

The previous two sections have shown that when a non wh-element is contrasted in a question (i.e., when it is a contrastive topic), the contrast is not limited to the non-wh part of the question and wh-fronting occurs. The contrasted non-wh part plus the whP form a pair that is in turn contrasted with another alternative pair (e.g., 35: <the fish card, the fish square> vs. <the parrot card, the parrot square>, etc.).Footnote 38 These examples show that fronting requires the whP to be an active part of the contrast, otherwise fronting does not occur. The following scenario and examples buttress the argument:

-

(37)

Dinner scenario: Three guests: Marie, Paul and Guillaume. The host cooks the main course and asks the guests to bring three items: wine, dessert and cheese.

-

(38)

Let us know consider the next two subscenarios:

-

(39)

Subscenario 1: The host said: “I need wine, dessert and cheese. Bring what you want.”

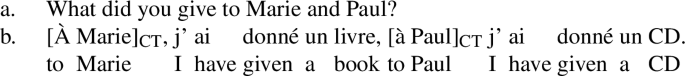

The key point is that the three required items might not distribute complementarily across the guests, that is they might all bring wine for example. In this scenario, the subquestions (38a–c) can translate as (40), where Marie, Paul and Guillaume all bear a C-accent, that is, they are contrastive topics (CT).Footnote 39

-

(40)

In these (sub)questions, note that the wh- is in-situ despite the CT. Examples (40) thus illustrate that CT per se does not trigger wh-fronting. Let us now consider Subscenario 2:

-

(41)

Subscenario 2: The host said: “I need wine, dessert and cheese. May each of you choose an item, so that we have everything for dinner.”

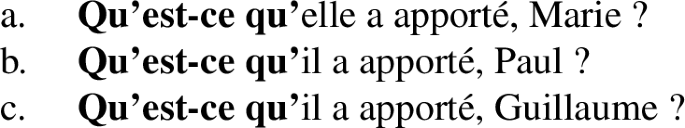

In this scenario, the subquestions (38a-c) can translate as (42), where Marie, Paul and Guillaume are again contrastive topics.

-

(42)

The difference between Subscenario 1 (wh-in-situ) and Subscenario 2 (wh-ex-situ) is that the three items (wine, dessert and cheese) are mutually exclusive in the latter only. They are in complementary distribution: If Marie brings wine, Paul cannot bring wine and he has to bring cheese or dessert. The contexts for (40) and (42) thus disentangle Contrast on the non-wh-part of the question and Contrast on the wh-item. Although Contrast on the non-wh-part favors Contrast on the wh-item, it does not necessarily trigger wh-fronting (40), whereas Contrast on the wh-item does (42) because the items underlying the wh- (wine, dessert and cheese) are in mutually exclusive distribution.

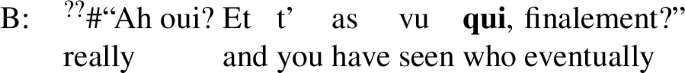

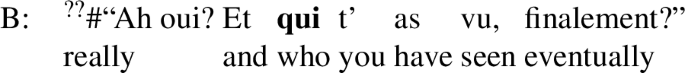

To make it clearer, here is another situation where wh-fronting is available in simple questions with no contrast on the non-wh part. Consider context (43) and questions (44) and (45):

-

(43)

A: “At work, I had a computer issue. I had to go to Marie, Paul or Guillaume to solve it.”

-

(44)

-

(45)

B has to select one of three individuals and does not know which one. S/he asks the question in order for A to perform this operation for him/her. In this context, (45)Footnote 40 with the prosody described for (4aα) is felt to be degraded. In contrast, (44) is perfectly natural, which shows that wh-ex-situ questions are optimal when there is a selection in a set, EXCLUDING the rest of the set.

4.4 Intermediate summary

In Sect. 4, we observed that wh-fronting occurs when:

-

1)

There is a one-to-one mapping from one set onto another set (4.1, 4.3).

-

2)

There is a potential contrast between two (sets of the) possible referents of the whP (4.2).

-

3)

The speaker’s question implies that the addressee can select one item only from a set, and hence has to exclude the rest of the set in order to answer the question (4.3, ex. 44).

Section 5 will aim to provide a formalization that captures the above observations.

5 Formalizing an exclusivity operator

In the previous section, we highlighted that contrast seems to be the hallmark of wh-ex-situ in Colloquial French and that it is thus absent in (unstressed) wh-in-situ. Section 5 will address the matter of what it means for a wh-item to be contrasted and will attempt to formalize this contrastive feature. We shall review two hypotheses: 1) The feature is a Contrastive Topic feature, 2) The feature is an idiosyncratic feature, and elaborate on the latter.

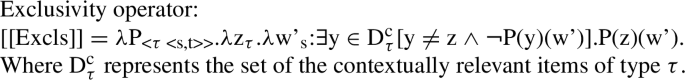

5.1 Hypothesis 1: Contrastive Topic

A brief presentation of Rooth’s (1985, 1992) semantics for focus and Constant’s (2014) semantics for contrastive topics (henceforth CT) is in order before we concentrate on CT in wh-questions.

5.1.1 Rooth’s semantics for focus and Constant’s semantics for Contrastive Topics

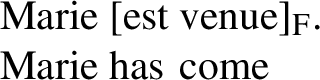

The crucial idea in Rooth (1985, 1992) is that focus marking on a phrase yields a set of alternatives (focus is indicated with the subscript F). To see how these alternatives work, let us consider (46).

-

(46)

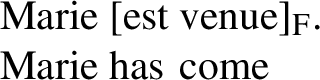

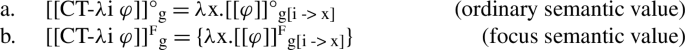

A sentence like (46) has two semantic values corresponding to two levels of interpretation. For its ordinary semantic value, the meaning of the sentence obtains via the usual rules of composition. Thus, (46) has the meaning (47) (ignoring tense and intensions). The focus semantic value (noted F) is obtained by generating a set of propositions that includes the asserted proposition and all the propositions that can be obtained by substituting the possible alternatives for the focused item, thus yielding (48).

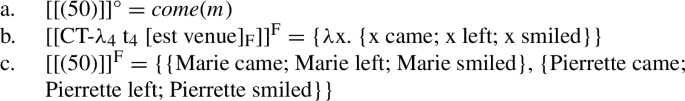

-

(47)

[[Marie [est venue]F]]° = come(m)

-

(48)

[[Marie [est venue]F]]F = {λw.P(m)(w)|P<e<s,t>>} = {Marie came; Marie left; Marie smiled}

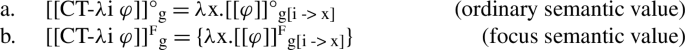

Let us now see what happens if some phrase in the sentence is additionally CT-marked. According to Constant (2014), sentences with a CT contain an operator responsible for the movement of the phrase that bears the CT feature, movement which triggers a λ-abstraction (much like Quantifier Raising). (49) gives the semantics of this operator and (50) a simple example.

-

(49)

-

(50)

[Marie4]CT CT-\(\lambda_{4}\) t4 [est venue]F.

Like Rooth (1985, 1992), Constant (2014) assumes a two-tier semantics. The first tier is the ordinary semantics in (49a). At this level, (50) means come(m), much like (47). The second tier is the level where the foci (including CT) are evaluated (49b). In the example, two phrases bear a focus feature: the DP Marie and the VP est venue. Combining the focus semantic value of est venue (see 48) with the operator gives (51b), which can then combine with the focus semantic value of Marie (say, the set {Marie, Pierrette}) by pointwise functional application, yielding the set of sets of propositions (51c).Footnote 41

-

(51)

5.1.2 A CT-feature on wh?

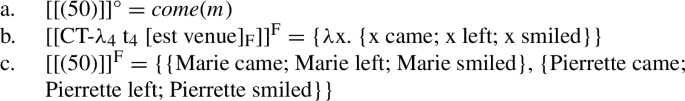

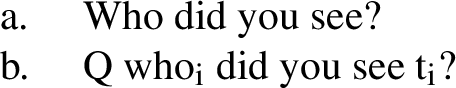

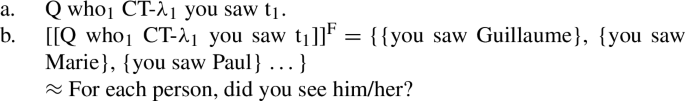

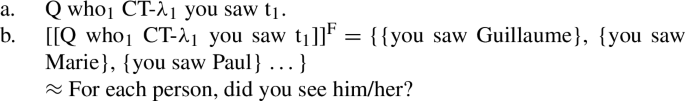

Let us now move on to wh-questions. According to Rooth (1992) and Vallduví and Vilkuna (1998), wh-items are intrinsically endowed with a focus feature that “generates a ‘wh-set,’ a domain over which they ‘quantify’’’ (Vallduví and Vilkuna 1998:86). Consequently, the meaning of a question is the set of propositions that constitutes the possible answers (Hamblin 1973). In order to understand its mechanics, let us consider question (52a) and its LF (52b). Let us moreover assume that the denotation of who in w is the set of individuals given in (53) and that the denotation of you saw (ignoring tense) is as (54). By pointwise functional application of (54) to (53), we obtain (55), the meaning of (52). Note that (55) is a set of propositions, much like (48) the focus semantic value of (46).

-

(52)

-

(53)

[[who]]w = {Guillaume; Paul; Marie}

-

(54)

[[you saw]]w = λxe.you saw x (w)

-

(55)

[[Who did you see]]w = {you saw Guillaume; you saw Marie; you saw Paul}

Now, we saw abundant evidence in the previous sections that some wh-items are contrastive while others are not.Footnote 42 Consequently, we propose that the wh may be both focused and contrastive in some questions. If, as we saw, focus is responsible for questions denoting sets of propositions, contrast (another type of focus) would make them a set of sets of propositions. This idea was tentatively entertained as a theoretical possibility in Constant (2014:112–113), who hypothesized that wh-items could be endowed with a CT feature on top of their focus feature. Under this hypothesis, (52) has two possible LFs. The first one is (52b) with the meaning (55) and the second one is (56a) with the meaning (56b):

-

(56)

Under interpretation (55), (52) will translate in French as the wh-in-situ question (57), whereas under interpretation (56), it will take the form of the wh-ex-situ question (58) (for a context in which such a question can be used, see the discussion around 44).

-

(57)

-

(58)

One advantage of this hypothesis is that the CT feature exists independently from questions. French CT occupies a position above IP, arguably the same as in English in (59).

-

(59)

Nevertheless, though appealing, there are several reasons to be suspicious about this idea of a wh-item marked as CT. First, we have no independent evidence that a CT feature can be assigned to a wh-item in a question in French, although we know that an element of the non-wh part of the question can receive such a feature (see 35, 36, 40 and fn. 36).

Second, CT can be assigned to multiple elements in a French assertive clause, as shown in (60), which is not the case for questions. Otherwise, we would expect multiple wh-fronting, even if it can be banned for independent reasons.

-

(60)

The third (related) objection is that the instantiation of the wh in the answer cannot be a CT, but must be focus. (58) cannot be felicitously answered with (61) (which we indicate with #). Note that a sentence like (61) is felicitous in certain circumstances, notably when it is an instance of ‘Lone CT’ (Constant 2014 contra Wagner 2012).

-

(61)

To conclude this section, although the idea of imposing a CT feature on the wh-item in French wh-ex-situ is appealing, it cannot be fully probed, and runs into too many objections. Instead, we shall pursue the second hypothesis, namely that there is an idiosyncratic feature on Colloquial French wh-ex-situ items.

5.2 Hypothesis 2: Exclusivity

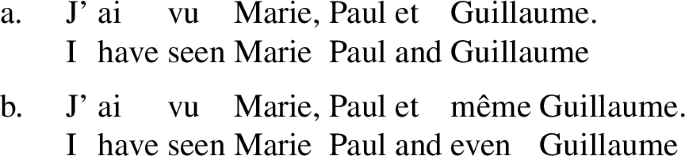

In the previous section, we tackled the idea that wh-items are intrinsically focused and can be contrastive on top of that, in a Hamblin semantics for questions, in which wh-items are variables. However, our findings in Sect. 3 showed that Colloquial French displays covert wh-movement, which points more towards wh-items being quantifiers than variables. This is why we adopt Karttunen’s (1977) semantics for questions, in which wh-words are treated as existential quantifiers and whPs as generalized quantifiers of type <<e,t> t>. In this framework, a question also denotes a set of propositions, but this set is created by the question operator and not by the wh-variable.

Before we proceed, it is important to note that the operator we are going to discuss is not a question operator. It is a separate, focus operator that feeds the question operator in the same way as the operator que ‘only’ applies in (62). This does not mean that que or our operator interact in a neutral way with the problem of whether the question is weakly exhaustive, strongly exhaustive, or non-exhaustive,Footnote 43 but they are clearly distinct (see the discussions in 5.3.2 and 5.3.3).

-

(62)

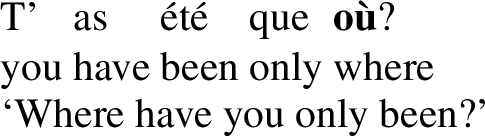

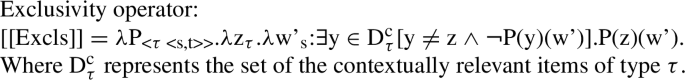

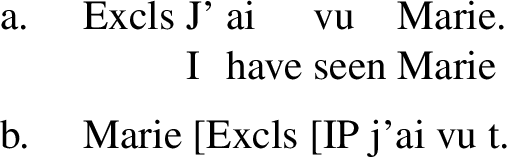

Building on the results in Sect. 4, (58) roughly means “Which x, y and z ∈ {Marie; Paul; Guillaume} are such that you saw x, but not y and z.” We propose that this meaning can arise through composition with a contrastive operator that overtly attracts the wh. Since the role of this operator is to exclude alternatives, we dub it Exclusivity (henceforth [Excls]). It is also more precise and has the advantage of avoiding the overused term contrast. (63) provides a formalization for this Exclusivity operator:Footnote 44

-

(63)

The operator is polymorphic since questions can bear on items of any type τ. It says that the property obtained once we have abstracted over the IP is true of a referent to the exclusion of some other(s). The first, presupposed part of the formula (∃y ∈ D\(^{\mathrm{c}}_{\tau}\)[y ≠ z ∧ ¬P(y)(w’)]) requires further discussion.

5.3 Presuppositions in questions

This section explores the presuppositional status of the subpart ∃y ∈ D\(^{\mathrm{c}}_{\tau}\)[y ≠ z ∧ ¬P(y)(w’)]. First, we unfold our approach in an answer-based theory of presuppositions in questions (5.3.1). Second, we motivate the existential quantifier and show that it implies that Exclusivity is distinct from Exhaustivity (5.3.2). Third, we develop the answer-set approach and the predictions [Excls] makes on a specific example to better illustrate its behavior (5.3.3).

5.3.1 Favoring an answer-based approach

We formalized presupposition as a definedness condition on questions, making use of Heim and Kratzer’s (1998) convention. Presuppositions in questions are far less studied than in declarative sentences. There are two families of approaches, either answer-based or question-based (phrasing as in Fitzpatrick 2005):

-

(64)

Answer-based approach:

A presupposition of a question is something that is entailed by every possible answer to it. (Keenan and Hull 1973)

-

(65)

Question-based approach:

A presupposition of a question is a necessary condition for a successful interrogative speech act. (Katz 1972)

While the latter posits that a question can inherit the presupposition from its constituents, the former assumes that no presupposition projects in questions, but that a question is infelicitous only if none of its answers is defined. Here is Guerzoni’s (2003) Question Bridge Principle (based on Stalnaker 1978):

-

(66)

Question Bridge Principle:

A question in felicitous in c ONLY IF it can be felicitously answered in c

(i.e., if at least one of its answers is defined in context c).

Although both could be necessary,Footnote 45 the answer-based approach is less redundant because in most cases the question-based approach predicts two reasons for the infelicity of the question: The question is undefined AND its possible answers are undefined (Guerzoni 2003, here simplified a lot). For this reason, we follow answer-based approaches, although our results are in principle harmlessly translatable to the other framework.

5.3.2 Existential quantification and Exhaustivity

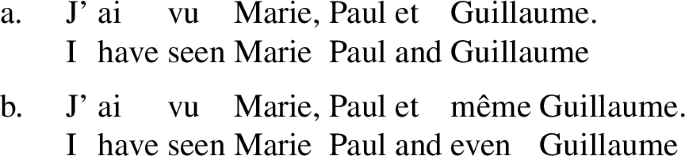

Regarding the quantifier in ∃y ∈ D\(^{\mathrm{c}}_{\tau}\)[y ≠ z ∧ ¬P(y)(w’)], existentiality must be posited for both logical and empirical reasons. First positing a universal quantifier would result in a contradiction.Footnote 46 Assuming the set D of three individuals {Guillaume; Paul; Marie}, if each proposition about one x in D in the question denotation of Who did you see? is defined only if some y ≠ x in D was not seen, the projection must be existential. Indeed, if it were universal we would end up presupposing for each x in D that there is a y ≠ x in D such that y was not seen, which is contradictory. Second, an answer like (67) is perfectly felicitous for (58) because (67) displays an exclusion, but not of all the alternatives in the set (55), as shown by the possibility of remaining agnostic about Guillaume.Footnote 47 Consequently, [Excls] implies that at least one element must be excluded.Footnote 48

-

(67)

J’ai vu Marie, j’ai pas vu Paul, mais je me souviens pas pour Guillaume.

‘I saw Marie, I didn’t see Paul, but regarding Guillaume, I cannot remember.’

A note is in order here on how Exclusivity relates to Exhaustivity because the latter can also involve exclusion. On the one hand, a question like (52) Who did you see? can be answered exhaustively in two ways, assuming that the speaker saw Marie: (68a) is the weakly exhaustive answer and (68b) is the strongly exhaustive one.Footnote 49

-

(68)

On the other hand, (68c) and (d) are exclusive but partial, non-exhaustive answers. Finally, if the correct answer is (68e), it is exhaustive but not exclusive (all three accessible individuals were seen, none being excluded). Consequently, Exclusivity does not imply Exhaustivity and Exhaustivity does not imply Exclusivity. They are two distinct operations. We argue that this applies to declarative sentences, as illustrated in (68), and questions. Put otherwise, the structure under examination here, wh-ex-situ, is not a mark of exhaustivity in Colloquial French questions.

A confirmation comes from a close, but distinct construction, namely clefts. One (frequent) means to mark exhaustivity in French questions is to cleft the wh-item, as illustrated in (69a) (Rouquier 2014). (69b) then shows that Exhaustivity and [Excls] are separate features and that both can aggregate to form an interrogative cleft with additional wh-fronting.Footnote 50 The combination of Exhaustivity and Exclusivity yields (70), the answer-set to (69b), to be compared to (74) (without Exhaustivity) and (72) (without Exhaustivity and Exclusivity).

-

(69)

-

(70)

[[Who Excls did you see]]w = {you saw Guillaume but not Marie and Paul; you saw Marie but not Guillaume and Paul; you saw Paul but not Marie and Guillaume; you saw Guillaume and Marie, but not Paul; you saw Guillaume and Paul but not Marie; you saw Marie and Paul but not Guillaume}

5.3.3 In-situ and ex-situ Answer-sets

To illustrate the effect of the presupposition ∃y ∈ D\(^{\mathrm{c}}_{\tau}\)[y ≠ z ∧ ¬P(y)(w’)], let us reuse scenario (43), and questions (44) and (45), repeated here and modified to (43′), (44′) and (45′) (underlined part added, judgments reassessed):

-

(43)

A: “At work, I had a computer issue. I had to go to Marie, Paul or Guillaume to solve it.”

-

(44)

-

(45)

-

(43′)

A: “At work, I had a computer issue. I had to go to Marie, Paul or Guillaume, or the three of them to solve it.”

-

(44)

-

(45)

We have to clarify why in-situ (45′) is better than ex-situ (44′) in the latter scenario, whereas ex-situ (44) is better than in-situ (45) in (43). To explain this observation, let us consider the answer-sets corresponding to (44)/(44′) and (45)/(45′), starting with (45)/(45′). (55) was a first approximation, not taking into account that qui ‘who’ is ambiguous between singular and plural. First, we assume here that the correct answer is selected by Dayal’s (1996) answerhood operator (71), which picks up the maximally informative answer in the answer-set, that is (72) for (45)/(45′).

-

(71)

Ans(Q) = λw.ιp[pw ∧ p ∈ Q ∧ ∀p’ [[p’w ∧ p’ ∈ Q] → p ⊆ p’]]

-

(72)

[[Who did you see]]w = {you saw Guillaume; you saw Marie; you saw Paul; you saw Guillaume and Marie; you saw Guillaume and Paul; you saw Marie and Paul; you saw Guillaume, Marie and Paul}

Second, to construe the answer-set to (44)/(44′), let us consider answers like (73a).

-

(73)

To be felicitous, (73a) must mean ‘I saw Marie and there is someone else (either Guillaume or Paul) that I did not see.’ Put otherwise, Marie is attracted to the specifier of Excls°. (73b) is (73a)’s LF. Note that Marie is in situ in (73a) whereas qui is ex-situ in the corresponding question. But in the context of (44) Marie carries the rise-fall accent marking specificity that the out-of-the-blue utterance would not display (see the analysis of example 4b and fn. 7). The reason why questions have both the options of fronting and accenting, whereas only accenting is available to the answer is left to future research. The answer-set corresponding to (44)/(44′) is thus (taking the exclusion “but not” into account, boldface and underlining explained below):

-

(74)

[[Who Excls did you see]]w = {you saw Guillaume but not Marie; you saw Guillaume but not Paul; you saw Guillaume but not Marie and Paul; you saw Marie but not Guillaume; you saw Marie but not Paul; you saw Marie but not Guillaume and Paul; you saw Paul but not Marie; you saw Paul but not Guillaume; you saw Paul but not Marie and Guillaume; you saw Guillaume and Marie, but not Paul; you saw Guillaume and Paul but not Marie; you saw Marie and Paul but not Guillaume}

The two answer-sets being in place (72 to the in-situ question and 74 to the ex-situ question), let us come back to Scenarios (43) and (43′), starting with (43).

Scenario (43) implies that the speaker did not meet all three individuals, and hence cannot entail the proposition you saw Guillaume, Marie and Paul. This latter proposition being part of the answer-set (72) to the in-situ question (45), this question is not optimal in this context because it includes an answer that is undefined. Conversely, a question like (44) featuring [Excls] will be felicitous. All the propositions in its answer-set (74) are defined in context (43). Suppose now that Guillaume is the only person that the speaker saw. In this frame, the bolded and underlined answers in (74) are the correct answers to ex-situ (44). Note that if the question is also exhaustive, the correct answer will be the underlined one only.

In contrast, in the frame of (43′), A’s utterance entails that the proposition ‘you saw Guillaume, Marie and Paul’ is a contextually possible answer, that is, there is a possible answer that is in the denotation of the in-situ question (45′), but not of the ex-situ question (44′). Consequently in-situ (45′) comes out as more optimal than ex-situ (44′).

Note that in the frame of (43), uttering in-situ (45) is not impossible but would sound like a presupposition cancellation; that is, the pre-construed answer-set, which is narrower and more specific than in-situ (45), will be enriched with the proposition ‘you saw Guillaume, Marie and Paul.’ Conversely, ex-situ (44′) is not impossible, but sounds bizarre because the pre-construed answer-set of possibilities in the frame of (43′) is larger than what (44′) denotes (it includes ‘you saw Guillaume, Marie and Paul’). Uttering (44′) then has the effect of narrowing down the pre-construed answer-set. In a nutshell, depending on the contexts, either in-situ or ex-situ questions will sound degraded, because a pragmatic adjustment will be required. Nevertheless, because this operation is available, the judgments are never as clear-cut as in the case of a presupposition cancellation like (75), where there is a contradiction between the presupposition ‘Jean smoked’ and b’s utterance.

-

(75)

a. Jean il a arrêté de fumer. b. #En fait, il a jamais fumé.

‘Jean stopped smoking. Actually, he has never smoked.’

Finally, imagine that ex-situ (44) is answered with (76a) (which does not belong to its answer-set). Here again an adjustment is necessary and (76a) sounds like (76b), with the corrective même ‘even’ in the context of (43). Likewise, this adjustment is not as sharp as a presupposition cancellation. This comes as natural in the answer-based approach to questions presuppositions (64), since in this frame (44)’s presupposition is only pragmatic, i.e., construed on the pre-construed answer-set (74). More research is needed however to better understand how this transfer between the answers and the question works exactly.

-

(76)

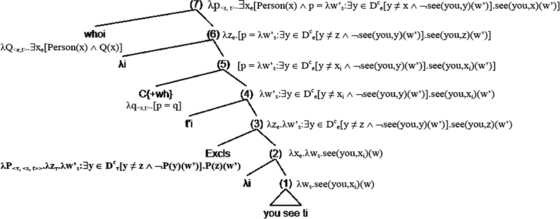

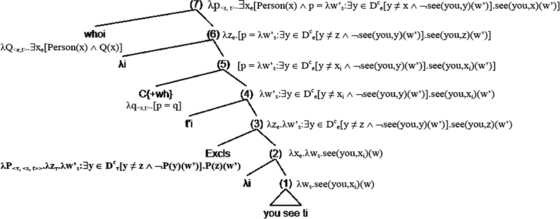

5.4 Representing the Exclusivity operator

Figure (77) shows how this operator works in example (44). [Excls] is placed above IP to account for the landing site of the ex-situ whP. If it were not for this surface position, other locations could have been envisaged, like above vP. Let us note that ∃y ∈ D\(^{\mathrm{c}}_{\mathrm{e}}\)[y ≠ x ∧ ¬see(you,y)(w’)] is embedded as expected in an answer-based approach to presuppositions in questions (it does not project and is therefore not a definedness condition for the question itself, but rather for its answers).

-

(77)

Remarks:

-

We ignore tense.

-

We set up the operator to type e.

-

We treat the traces as free variables of type e, which we represent with an x bearing the index of their binder.

-

We follow Karttunen’s (1977) semantics for questions revised as in Dayal (2016). In particular, we do not claim that questions denote the set of their true answers but only of their possible answers, as in Hamblin (1973).

-

The wh-item undergoes two movements, first to the [Excls] operator’s specifier, second (covertly) to the interrogative complementizer C[+wh]’s specifier.

-

The appended λ (under nodes 2 and 6) represent the abstraction triggered by these movements (see coindexation).

The steps of the composition are as follows (numbers refer to 77):

-

(2)

λxe.λws.see(you,xi)(w) (predicate abstraction)

-

(3)

[[Excls]] ([[2]])= λze.λw’s:∃y ∈ D\(^{\mathrm{c}}_{\mathrm{e}}\)[y ≠ z ∧ ¬see(you,y)(w’)].see(you,z)(w’) (functional application)

-

(4)

[[3]] ([[ti]]) = λw’s:∃y ∈ D\(^{\mathrm{c}}_{\mathrm{e}}\)[y ≠ xi ∧ ¬see(you,y)(w’)].see(you,xi)(w’) (functional application)

-

(5)

[[C[+wh]]] ([[4]]) = [p = λw’s:∃y ∈ D\(^{\mathrm{c}}_{\mathrm{e}}\)[y ≠ xi ∧ ¬see(you,y)(w’)].see(you,xi) (w’)] (functional application)

-

(6)

=> λze.[p = λw’s:∃y ∈ D\(^{\mathrm{c}}_{\mathrm{e}}\)[y ≠ z ∧ ¬see(you,y)(w’)].see(you,z)(w’)] (predicate abstraction)

-

(7)

[[whoi]] ([[6]]) = ∃xe[Person(x) ∧ p = λw’s:∃y ∈ D\(^{\mathrm{c}}_{\mathrm{e}}\)[y ≠ x ∧ ¬see(you,y)(w’)]. see(you,x)(w’)] (functional application)

The outcome is in (78) (abstraction over the free variable p and creation of a set of propositions/a question). In words, (44) means that the speaker is asking the hearer which person the hearer has seen, presuming that there is also at least one person that the hearer could have seen but has not seen.

-

(78)

λp<s,t>.∃xe[Person(x) ∧ p = λw’s:∃y ∈ D\(^{\mathrm{c}}_{\mathrm{e}}\)[y ≠ x ∧ ¬see(you,y)(w’)]. see(you,x)(w’)]

In this section, we proposed a formalization of the observations presented in Sect. 4 on the contrast that drives overt wh-fronting in Colloquial French. Trying to import a CT feature, we found out that contrast in questions is better viewed as a presupposition triggered by an Exclusivity operator that excludes at least one of the possible answers.

6 Conclusions

This article examined in-situ and ex-situ wh-questions in Colloquial French, a language that undoubtedly displays both structures, as shown in Sect. 2. The aims were twofold: establish which wh-position is the unmarked, default one, and describe the characteristics of the other, marked wh-position.

In Sect. 3, we showed that (a subset of) wh-in-situ questions are sensitive to constraints on wh-movement (i.e., weak-islandhood and Superiority), which indicates that in-situ questions are cases of unmarked questions with covert wh-movement. We also examined wh-ex-situ questions and showed that they are insensitive to these constraints, which makes them instances of a special type of question, where wh-fronting is not driven by a wh-feature, but by another feature. Consequently, we suggested that Colloquial French is a wh-in-situ language and that wh-ex-situ is wh-fronting, not wh-movement. These results provide arguments against the optionality stance.

In Sect. 4, we examined which feature could be triggering wh-fronting in Colloquial French, and we showed that it is a type of contrast, namely Exclusivity, which implies that at least one of the possible answers is excluded, thus putting the focus on the correct ones. Interestingly, this exclusive/contrastive feature, although cognate to well-known features like Contrastive Topic, is not reducible to them. This way, we have contributed to the debate on information structure in questions (Beyssade 2006; Constant 2014; Engdahl 2006) by showing that phenomena like focus or contrast need to be adjusted to be able to fit in with the semantics of questions, sometimes giving rise to specific pragmatic effects. In Sect. 5, we formalized the Exclusivity operator [[Excls]] as a definedness condition (63).

Finally and more generally, this article opens a program of research on the varieties of questions across languages. First, it might be interesting to consider other wh-in-situ languages that also display wh-ex-situ questions (see Sect. 1) in light of the Exclusivity operator defined in Sect. 5. It is promising to note that (Cheung 2008) argues that wh-fronting marks contrastive focus in Chinese, a result close to ours.

Another question concerns pair-list readings, which most speakers highly prefer for wh-ex-situ multiple questions (Sect. 3.2), whereas single-pair readings are freely accessible for wh-in-situ ones. Moreover, the strong-island facts in (16) showed that in LF both wh-words have to be in CP in ex-situ multiple wh-questions much like what is required to have a pair-list reading (Dayal 2003, 2006; Kitagawa et al. 2004; Kotek 2017). Yet, it is difficult to derive this reading from our Exclusivity operator, unless the contrast the operator involves just favors it. More work is definitely needed to assess this hypothesis.

Embedded questions also challenge the present analysis because they supposedly never feature wh-in-situ (Bobaljik and Wurmbrand 2015), although they can have the semantics of wh-in-situ direct questions (see Baunaz 2011:227, fn. 213). Yet, recently-collected data show that wh-in-situ is gaining ground in embedded questions (Gardner-Chloros and Secova 2018; Poletto and Pollock to appear). Further research could establish whether embedded in-situ introduces an alternation equivalent to what is found in direct questions.

Finally, the ex-situ/in-situ alternation is not limited to wh-in-situ languages. For example, English has at least three varieties of wh-questions: ex-situ with and without pied-piping, the latter being more expressive (79, 80, from Obenauer 1994); and wh-in-situ questions, especially when the wh is focused (81, from Bobaljik and Wurmbrand 2015).

-

(79)

(*Well,) on whose help did you count?

-

(80)

Well, whose help did you count on?

-

(81)

More research is definitely needed in order to broaden the empirical coverage of the proposal on Exclusivity in Colloquial French and see whether it can also capture cross-linguistic facts.

Notes

Metropolitan French refers to the language used in European France (so-called ‘Metropole’), as opposed to other varieties of French in other parts of the world (e.g., Overseas France, Belgium, Switzerland, Quebec, etc.). We elaborate on Colloquial Metropolitan French in Sect. 2 and do not take a stand on the other varieties of French. However, we wish to thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing out that the results achieved here carry over to other varieties of French.

We shall leave aside echo questions, which strongly favor wh-in-situ across languages (Wachowicz 1974a,b). We shall not be examining embedded questions either because they mostly appear with ex-situ whPs for reasons that might be different from what we have in direct questions (but see Sect. 6 for a few remarks). Finally, we shall omit questions with subject whPs since they always appear preverbally in French and it cannot be shown whether they are in-situ or fronted.

See Baunaz (2011, 2016); Boeckx (2000); Boeckx et al. (2001); Bošković (2000); Chang (1997); Cheng and Rooryck (2000); Coveney (1989, 1995); Denham (2000); Déprez (2018); Déprez et al. (2012, 2013); Larrivée (2016); Lasnik and Saito (1992); Mathieu (2004, 2009); Munaro et al. (2001); Munaro and Pollock (2005); Myers (2007); Quillard (2000); Shlonsky (2012); Tailleur (2014); Vergnaud and Zubizarreta (2005); Zubizarreta (2003). See also GENWH 2018, The Geneva WH-orkshop on Optional Insituness at https://genwh2018.wordpress.com/, last accessed 18 May 2020.

Here are Baunaz’s (2016) definitions (The reader is referred to the original article for details):

“A partitive wh-phrase is an object, which belongs to a presupposed set containing more objects. Each of the objects of the set can potentially be referents to the answer of the wh-phrase, i.e., all are alternatives.” (p. 134).

“Specificity narrows down the context to familiar individuals, excluding alternatives. A constituent question involving specificity entails an answer referring to a familiar individual that the interlocutor has in mind.” (p. 137)

(4b) is arguably a case of ‘Question with Declarative Syntax,’ in which the focus is replaced in situ by a wh, and the interrogative meaning is acquired at the pragmatic level and does not directly follow from clause-typing (Bobaljik and Wurmbrand 2015), which solves Baunaz’s (2011) issue on a subset of D-linked multiple questions in English. It is beyond the scope of this article to compare the syntax of the various types of wh-in-situ questions. Poletto and Pollock (to appear) (and in earlier work) argue that there are at least two syntactic types of wh-in-situ, respectively displaying overt remnant-IP and remnant-vP movement. We claim that there is at least one type with covert wh-movement and no IP-movement (see Sect. 3), in line with Bonan’s (2019) cross-Romance perspective.

Villeneuve and Auger (2013) have aimed to reconcile both approaches based on French and Picard data.

Examples are from our corpus of seminaturalistic data, which contains a total of 913 finite, matrix wh-questions produced by 17 children between 2;06 and 4;11, all native speakers of L1 Metropolitan French (Palasis et al. 2019).

For an insightful account of the behavior of whPs in SCLI G2 questions, see Poletto and Pollock (to appear) (and previous work).

In all the examples in Sect. 3, it is important for the whP not to range among a given set, i.e., not to be D(iscourse)-linked (Pesetsky 1987). Otherwise, another type of wh-in-situ question is triggered (partitive, or exclusive with stressed wh-), whose behavior regarding islandhood is different, as shown in Baunaz (2011, 2016).

No good representational account in terms of Minimality is available, as acknowledged by Luigi Rizzi himself, who also posits a subjacency constraint to explain strong islands (Rizzi 2001). The reason for that is that no feature has been found so far that could be responsible for the Minimality effect. More on Relativized Minimality in Sect. 3.2. Another family of explanations accounts for sentences like (9b) in terms of processing difficulties involving the interaction between the necessity of holding a term in working memory until the gap (its interpretation position) is reached, and the lexical semantic processing factors at the embedded clause boundary (Kluender and Kutas 1993). But they do not address the degradation of cases like (9a), where supposedly nothing has to be held in memory.

It crucially rests on varieties of French that feature SCLI (G2), which we excluded (see Sect. 2), but are well accounted for in the remnant-movement approach. This means that Bonan’s (2019) position is right, according to which both remnant-IP movement and bona fide wh-insituness are necessary to account for the variety of wh-insituness across (and sometimes within) languages.

Jean-Yves Pollock (p.c.).

We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing out this fact to us.

We limit ourselves to two wh-items here.

(16a′) sounds echoic to an anonymous reviewer (native speaker of French), whereas our informants found it acceptable in the given context as a request for information. This discrepancy may be due to an idiolectal difference.

Alternatively, one could propose an explanation along the lines of Richards’s (1998:604–608) Principle of Minimal Compliance. Simplifying the framework, constraints apply only once. In our example (16a′), both wh move, but the second one is not submitted to subjacency, since this constraint was already checked and found non-violated by the first wh. “It appears to be true quite generally that in cases involving multiple wh-movement to a single [+wh] complementizer, only the first-moved wh-word will have to obey Subjacency; the other wh-movements are free from Subjacency. This is true regardless of the levels at which the wh-words move [SS or LF].” (p. 608)

Once again, additional stress on the wh-in-situ repairs the island violation and triggers a pair-list reading (Hirschbühler 1979).

We shall not use factive islands here because the judgments of our informants are less clear-cut and no clear contrast appears when the context changes.

We follow Abrusán’s (2014) semantic theory of weak islands based on the idea that the interaction between the island that contains certain types of predicates and some question words (but crucially not all) yields a contradiction (i.e., configurations in which there is no maximally informative answer contrary to what is required in the act of questioning). This account best explains the argument/adjunct asymmetry and why the unacceptability disappears in certain contexts.

Note that the asymmetry resurfaces and (only) the argument questions become better when the in-situ questions are set in a context that makes them partitive or specific (in which case, the wh-item is stressed, a pattern that we do not examine in detail here; see the discussion around 4 in Sect. 1).

Unless speakers construe the second wh as remaining in situ, in which case we are in configuration (i) hereafter and an intervention effect could arise between Q and WH2. This is unlikely, however, given our analysis of (16b) and Dayal’s (1996, 2003) account for multiple questions, in which both wh must be in CP (i.e., configuration (i) does not arise for multiple ex-situ questions).

(i) Q WH1 … intervener … WH2

Where X asymmetrically c-commands Y and Y asymmetrically c-commands Z, X and Y being of the same structural type, and where X and Z form a chain.

Likewise, some speakers of French, including an anonymous reviewer, find (18b) slightly better than (18a) (hence the rating ?∗) because the former violates only Abrusán’s island constraint, while the latter additionally violates Relativized Minimality.

Despite much resemblance, Superiority is not easily amenable to Relativized Minimality, as pointed out in Rizzi (2011).

There has also been discussion around the order of direct and indirect objects (Larson 1988). Note however that (i), which features the reverse order of (26), is strongly unacceptable, no matter the prosody. We take it to be proof that (26) features the basic word order.

-

(i)

-

(i)

(a) is sometimes rated as slightly better than (b), but both are deemed acceptable.

This is in line with (Palasis et al. 2019): In child speech, wh-ex-situ questions are favored when the sentence has more content, namely when it contains elements that can be contrasted with others in the context. On the other hand, presentational sentences with the fixed (and semantically empty) be form c’est ‘it is’ strongly favor wh-in-situ.

Numbering as in the original document, glosses and translations adapted. Once again, in A1′ the wh-in-situ question with a modal is rescued if quoi is stressed.

On the basis of expressive contexts, Obenauer (1994:357) already suggested that in ex-situ wh-questions the referent is outside the domain Δ examined by the speaker, whereas in-situ wh-questions locate the variable in a non-empty domain Δ.

The result is close to Büring’s (2003), but is syntactically anchored and achieved compositionally.

For independent evidence on a distinction between contrast and focus, on both the prosodic and the interpretive sides, see Erteschik-Shir (2007), Katz and Selkirk (2011), É. Kiss (1998); Kratzer and Selkirk (2010), Lee (1999), Molnár (2002), Rochemont (1986), Selkirk (2008) and Vallduví and Vilkuna (1998).

Unless we transfer to an operator below the question operator part of the burden attributed to it in the discussions around weak/strong/absence of exhaustivity in questions. This research program is beyond the scope of this article, but see the commentary to the answer-set (74).

We follow Heim and Kratzer’s (1998) convention in placing the presuppositional part of the formula between ‘:’ and ‘.’ (to be discussed below).

See Fitzpatrick (2005) on how-come and why-questions. To our knowledge, a detailed study of this phenomenon and whether the various presupposition triggers have the same effect is still to be done.

This was pointed out to us by an anonymous reviewer.

Part of the discussion here was inspired by Yabushita’s (2017) discussion on contrastive operators. Note that (55), which serves as a baseline for the present discussion, is provisional and is revised in (72)/(74).

A weakly exhaustive answer contains all the positive answers to a question, whereas a strongly exhaustive answer contains both the positive and the negative answers to a question (Beck and Rullman 1999; George 2011; Groenendijk and Stokhof 1984; Heim 1994; Sharvit 2002, among others). To account for exhaustive answers, Heim (1994) and Dayal (2016) designed specific answerhood operators. Alternatively, one can imagine a covert wh-only operator that is below C[+WH] and accounts for exhaustivity (Nicolae 2015).

Zumwald Küster (2018:105) proposes that the third form with additional est-ce inversion (e.g., qui est-ce que) is not used as a clefting device but as an unanalyzed chunk that allows the speaker to dispense with subject-verb inversion (qui est-ce que t’as vu? vs qui as-tu vu?).

References

Abner, Natasha. 2011. WH-words that go bump in the right. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 28, eds. Mary Byram Washburn, Katherine McKinney-Bock, Erika Varis, Ann Sawyer, and Barbara Tomaszewicz, 24–32. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project.

Abrusán, Marta. 2014. Weak island semantics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Adli, Aria. 2006. French wh-in-situ questions and syntactic optionality: Evidence from three data types. Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft 25: 163–203.

Aoun, Joseph, Norbert Hornstein, and Dominique Sportiche. 1981. Some aspects of wide scope quantification. Journal of Linguistic Research 1(3): 69–95.

Ashby, William J. 1977a. Clitic inflection in French: A historical perspective. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Ashby, William J. 1977b. Interrogative forms in Parisian French. Semasia 4: 35–52.

Ashby, William J. 1981. The loss of the negative particle ne in French: A syntactic change in progress. Language 57: 647–687.

Ashby, William J. 1984. The elision of /l/ in French clitic pronouns and articles. In Romanitas: Studies in Romance linguistics, ed. Ernst Pulgram, 1–16. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Barra-Jover, Mario. 2004. Interrogatives, négatives et évolution des traits formels du verbe en français parlé. Langue Française 141: 110–125.

Barra-Jover, Mario. 2010. «Le» français ou ce qui arrive lorsqu’un état de choses est observé comme une entité. Langue Française 168(4): 3–18.

Baunaz, Lena. 2011. The grammar of French quantification. Dordrecht: Springer.

Baunaz, Lena. 2016. French “quantifiers” in questions: Interface strategies. Acta Linguistica Hungarica 63(2): 125–168.

Baunaz, Lena, and Cédric Patin. 2011. Prosody refers to semantic factors: Evidence from French wh- words. In Actes de interface discours et prosodie 2009, eds. Hiyon Yoo and Elisabeth Delais-Roussarie, 96–107.

Beck, Sigrid. 1996. Quantified structures as barriers for LF movement. Natural Language Semantics 4: 1–56.

Beck, Sigrid. 2006. Intervention effects follow from focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 14: 1–56.

Beck, Sigrid, and Shin-Sook Kim. 1997. On Wh- and operator scope in Korean. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 6: 339–384.

Beck, Sigrid, and Hotze Rullman. 1999. A flexible approach to exhaustivity in questions. Natural Language Semantics 7(3): 249–298.

Beeching, Kate, Nigel Armstrong, and Françoise Gadet. 2009. Sociolinguistic variation in contemporary French. Amsterdam: Benjamins.