Abstract

It is generally thought that wh-in-situ, like overt movement, is potentially unbounded. At the same time, certain languages have been argued to disallow long-distance wh-in-situ. This paper argues that even in languages that show apparent clause-boundedness effects, wh-in-situ, like wh-movement, can in principle cross an arbitrary number of clauses. Failure to license a wh-phrase across a clause boundary, when it occurs, can be shown to result from the interaction between wh-agreement and independent operations affecting embedded clauses. Evidence will be drawn primarily from Malayalam (Dravidian), which has been argued to disallow long-distance wh-in-situ with finite embedded clauses. I will show that the relevant factor for wh-licensing is not finiteness, but Ā-movement of embedded clauses, an operation that is common with finite CPs. The core of the problem lies in the fact that interrogative C is a generalized [Ā]-probe that can interact with a number of featurally more specific goals, including the [Ā]-features on the head of the moving clause. It will be shown that this approach can account for a number of facts about Malayalam wh-question formation, including selective transparency of certain finite clauses for long-distance wh-licensing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

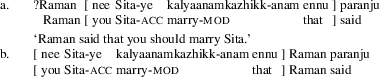

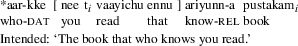

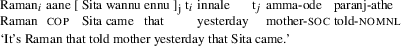

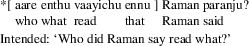

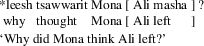

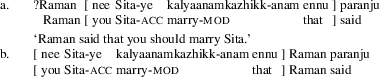

The syntax of in-situ wh-expressions is much-debated. At least three camps of analysis can be found in the literature: (i) wh-phrases covertly move to C (e.g. Huang 1982), (ii) some Q-related operator, not the wh-element itself, undergoes movement (Hagstrom 1998; Cable 2010) and (iii) there is no movement at all (Baker 1970; Reinhart 1998). As will be shown in Sect. 2, a covert-movement analysis is not supported by the Malayalam data. For present purposes, I will assume that Malayalam wh-phrases remain in their base position. The syntactic link between the wh-expression and its scope position is taken to be established via Agree.

There is debate as to what counts as a finite clause in Malayalam. For instance, Amritavalli and Jayaseelan (2005) argues that only clauses that can host certain modals, mood morphology and “high” negation can be considered finite. Though this debate is not crucial to the issues in this paper—it will be shown shortly that finiteness is not a relevant factor for wh-scope—the relevant finite clauses in the examples used in this section satisfy the aforementioned criteria of finiteness.

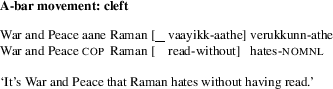

See Sect. 5 for evidence that Malayalam clefts involve overt movement.

See Dryer (1991) for a typological survey showing that movement of medial clauses to a peripheral position is commonplace for SOV languages.

Mohanan (1982) argues that what matters for binding in Malayalam is linear precedence. This does not seem to be the case for the dialect spoken by my informants (from the Pathanamthitta region of Kerala, India).

The precise reason for the restriction to Ā-movement is debated. Nissenbaum (2000), for instance, proposes that parasitic gaps involve the composition, by way of Predicate Modification (Heim and Kratzer 1998), of two predicates of type \(\left \langle e,t \right \rangle \), one derived by null-operator movement and the other by overt movement. The Ā-movement constraint follows if only this type of movement leaves the sort of variable that would result in the requisite type \(\left \langle e,t \right \rangle \) predicate.

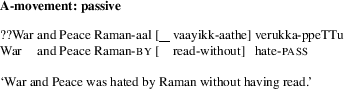

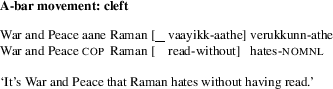

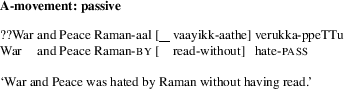

A word of caution is in order, however, since certain properties of Malayalam make parasitic gap licensing a less-than-perfect diagnostic for Ā-movement in this language. Malayalam is a topic-drop language (Ross 1982; Huang 1984), so it is possible to ameliorate the ill-formedness of unlicensed gaps in the right contexts by imagining a dropped topic in that position. But such a strategy is generally difficult where no prior discourse exists to license topic-drop. Thus, in the absence of a rich context, there is a contrast between truly grammatically licensed gaps and those “rescued” by a topic-drop strategy. We see this when comparing a parasitic gap in a cleft construction (ii) versus a passive (i); in the absence of a rich context, the cleft sentence with a gap is grammatical, but the passive sentence is quite odd.

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(i)

Embedded clauses with pronominal subjects are more acceptable in a medial position than those with lexical subjects, though dispreferred in comparison to embedded clauses with null subjects.

-

(i)

This gives preliminary evidence that the acceptability of medial clauses is not categorical, but gradient, a property that would be difficult to capture under analyses on which fronting is an operation that is obligatory for finite clauses. Relevantly for present purposes, the availability of wide-scope for embedded wh-questions correlate with fronting, even for these kinds of examples, as shown in (ii).

-

(ii)

For ease of exposition, however, I will restrict my examples to the clear-cut cases of acceptable (null subjects) and unacceptable (overt lexical subjects) medial clauses.

-

(i)

This could be related to the fact that canonically subjects are construed as topical in Malayalam (see e.g. Mathew 2014).

Note that in scrambling configurations, it is the scrambled element that receives prominence and heads its own phonological phrase (Swenson et al. 2015). As pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, we then expect that clauses that otherwise could remain in-situ are forced to front if scrambling has taken place. This prediction seems to be borne out, as shown in (i) below. The form in (b), where the direct object has scrambled to the left of the indirect object, but the clause remains in-situ, is degraded in comparison to (c), where that clause has fronted.

-

(i)

-

(i)

Though I have presented the prosodic requirements at play as obligatory rules for ease of exposition, they can be reformulated as violable constraints and incorporated into an Optimality Theoretic Model and the same conclusions should follow. However, doing so involves making claims about the syntax-prosody interface (e.g. what constitutes the input that defines the competing candidates) that go beyond the scope of this paper.

Not every one of these analyses take clausal movement to take place in the syntax, as I have argued is the case in Malayalam.

It is very difficult to form examples of the sort in (40) or (41) in Malayalam due to a number of language-specific confounds:

-

1.

Since Malayalam has short scrambling, it is often impossible to tell whether we have crossing paths or whether movement of a potential Minimality-violator is fed by scrambling (see e.g. Wiltschko 1997).

-

2.

Malayalam does not permit scrambling across a finite-clause-boundary (a fact that is independent of clause fronting), so one might consider constructing sentences where the two interacting elements are separated by a finite clause boundary. However, these examples would frequently implicate a third factor, namely Ā-movement of the finite clause.

-

3.

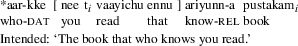

I was able to come up with examples like (i), which avoid the aforementioned problems, but they introduce a confound of their own, as they involve extraction from a wh-island.

-

(i)

Consequently, the remnant movement cases above are, as far as I can tell, the most clear-cut evidence in the language for Ā-interactions.

-

1.

An alternative would be to posit that finite clauses in Malayalam are not phasal. Some researchers have argued in favor of a more contextual approach to phasehood (see e.g. Bošković 2005; Bošković 2014). Adjudicating between the two alternatives is not important for us at present, as the current proposal is compatible with either one.

Though the question morpheme is not overtly present in wh-questions, I will follow Hagstrom (1998) and Cable (2010), among others, in assuming that a phonologically null variant is nevertheless present. Additional support for this comes from the fact that in pre 19th-century Malayalam, the question particle -oo was pronounced even in wh-questions (Jayaseelan 2001).

Since in the Ā-domain, Agree is not accompanied by morphological cues to the feature-specifications on the probe, we can only infer the feature-structure based on what kinds of elements the probe does and does not interact with. We reason that H is not equipped with a flat probe, because fronting can take place past an intervening Ā-feature-bearing element, as shown in (i). In (i), a cleft sentence, fronting of the embedded clause successfully takes place within the cleft-clause, although Ā-features are active on an intervening matrix subject.

-

(i)

-

(i)

One of these alternatives involves violating a syntactic locality constraint generally taken to be fundamental, whereas the other involves illicit prosody. We might expect that derivations involving the prosodic violation are more tolerable than those involving the former. Testing this prediction is difficult, as it involves comparing ill-formedness of different types, but my informants do find wh-in-situ with medial heavy clauses to be somewhat better than wh-in-situ inside fronted clauses.

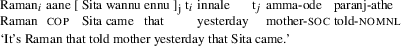

Thus far, we have restricted our attention to single wh-questions. The pattern of wh-licensing is the same in multiple wh-questions when there are one or more matrix-scope taking embedded wh-phrases: the wh-question is licensed when the clause is medial, but blocked when it is fronted, as shown in (i).

-

(i)

The approach advocated here should account for cases like (i) under the assumption that there are as many Ā-probes as there are wh-goals: the first Ā-probe will find the matrix wh-phrase, but the second probe will find the Ā-features on the clause first.

The situation is slightly different, though no less fatal, for cases like (ii), where there are multiple wh-phrases within the embedded clause.

-

(ii)

In such cases, we would expect that the first Ā-probe find and Agree with the intervening [fr] features. These features will be inactive thereafter, making it possible for the second Ā-probe to find one of the wh-phrases. However, in such a derivation, the clause should not be able to front, as the probe triggering this movement will not be able to find the requisite [fr] features. Thus, sentences like (ii), where the clause has fronted, cannot be generated.

-

(i)

It is also the case that clefts are prosodically distinct from canonical sentences, with main stress falling on the clefted constituent (e.g. Swenson et al. 2015). It could be the case that prosodic ill-formedness that could lead to clausal movement in canonical sentences simply do not arise in cleft configurations.

Given that clefting interacts with clausal fronting, another Ā-operation, as seen in e.g. (47) earlier, it is possible that the Focus head bears a generalized probe. However, since this distinction does not make a difference for present purposes—it is the order of the heads that matters—I will mark the head as bearing [Foc]-features for ease of exposition.

A reviewer wonders why Malayalam permits successive-cyclic Focus-movement in clefts, but the same strategy is not available in wh-questions. All that I am able to say about this at present is that Malayalam simply does not (overtly or covertly) move its wh-phrases to C, in short or long-distance questions (see evidence in Sects. 2.1 and 5.2 above). It is beyond the scope of this paper to offer an explanation for why Malayalam wh-elements fit into the typology as they do.

For Jayaseelan, clausal complements are base-generated to the right of the verb and move to a preverbal position like other internal arguments. However, because of a dispreference in the language for center-embedding, they extrapose.

Like clausal fronting in Malayalam, the post-verbal clause position does not have obvious semantic or information-structural correlates.

A number of authors have attempted to account for the binding facts within an anti-symmetric approach (Mahajan 1997; Simpson and Bhattacharya 2003; Simpson and Choudhury 2015). These authors take SVO to be the “default” word-order and argue that nominals get to a pre-verbal position via leftward movement, likely for Case reasons. I will not adopt this analysis here for a number of reasons. First, such an approach fails to explain the optional post-verbal positioning of non-finite clauses. Second, anti-symmetric approaches cannot explain the correlation between clause position and wh-scope and take them to be spurious (Simpson and Choudhury 2015). If patterns of restricted wh-scope across languages reflect the same underlying phenomenon, then the Malayalam data we saw in previous sections provide a compelling argument against such a view. The Malayalam fronted clauses we examined here do not appear in a post-verbal position to begin with and therefore the clausal movement patterns cannot be explained by resorting to anti-symmetry. On the other hand, an overt movement approach can capture the patterns in both Hindi-Urdu and Malayalam in a uniform fashion. For further arguments against anti-symmetric approaches, I refer the reader to Bhatt and Dayal (2007).

Note that Malayalam does not allow cases like (76).

Malayalam, unlike Hindi, does not allow scrambling as a rescue strategy, a fact that relates to the fact pointed out in fn. 13 that Malayalam disallows long-distance scrambling altogether. While I do not have an explanation for why this is, it should be pointed out that having short-scrambling, while lacking long-scrambling is a property that the language shares with many others, e.g. German, Mandarin, Czech, Tzezm Nez-Perce, a.o. Another long-distance question formation strategy in Hindi-Urdu is scope marking. One might ask whether the same is true for Malayalam. Since we never find cases in which one wh-element marks the scope of a different pronounced wh-element, I take it to be the case that scope-marking as found in languages like Hindi-Urdu, German, Hungarian, Russian, etc. does not exist in Malayalam (though see Jayaseelan 2004 for a differing view). We are grateful to a reviewer for raising these questions.

As pointed out in Ouhalla (1996), Iraqi Arabic does not allow scrambling, which suggests that this is genuine wh-movement.

It is worth noting that analyses positing wh-in-situ-specific locality conditions are also empirically inadequate when it comes to Iraqi Arabic. As was noted by Wahba (1991), restrictions on long-distance wh-question formation in Iraqi Arabic seem to extend beyond embedded wh-in-situ; long-distance movement of non-nominal wh-phrases is also blocked in the language, as shown in (1).

-

(1)

Thus, a full account of Iraqi Arabic long-distance question-formation would need to provide explanations for both (i) the apparent ban on long-distance wh-in-situ and (ii) the asymmetry between nominal and non-nominal wh-expressions when it comes to overt wh-fronting.

-

(1)

Another language that has clausal movement and allows wh-in-situ is German, and a reviewer asks what the present analysis predicts for this language. Finite clauses appear in an extraposed position, but they are often taken to right-adjoin to a lower position than CP (Müller 1996; Moulton 2015, a.o). This would mean that the probe triggering this movement is lower than C, and an intervention configuration should in principle be avoided.

References

Abels, Klaus. 2012. The Italian left periphery: A view from locality. Linguistic Inquiry 43: 229–254.

Adger, David, and Gillian Ramchand. 2005. Merge and move: Wh-dependencies revisited. Linguistic Inquiry 36 (2): 161–193.

Amritavalli, R., and K. A. Jayaseelan. 2005. Finiteness and negation in Dravidian. In The Oxford handbook of comparative syntax, eds. Guglielmo Cinque and Richard S. Kayne, 178–220. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baker, C. L. 1970. Double negatives. Linguistic Inquiry 1 (2): 169–186.

Barss, Andrew. 1986. Chains and anaphoric dependence: On reconstruction and its implications. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Basilico, David. 1998. Wh-movement in Iraqi Arabic and Slave. The Linguistic Review 15 (4): 301–339.

Bayer, Josef. 1997. CP extraposition as argument shift. In Rightward movement, eds. Dorothee Beerman, David LeBlanc, and Henk van Riemsdijk, 37–58. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Beck, Sigrid. 2006. Intervention effects follow from focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 14 (1): 1–56.

Béjar, Susana, and Milan Rezac. 2009. Cyclic agree. Linguistic Inquiry 40 (1): 35–73.

Bhatt, Rajesh, and Veneeta Dayal. 2007. Rightward scrambling as rightward remnant movement. Linguistic Inquiry 38 (2): 287–301.

Bošković, Željko. 2005. On the locality of left branch extraction and the structure of NP. Studia Linguistica 59 (1): 1–45.

Bošković, Željko. 2014. Now I’m a phase, now I’m not a phase: On the variability of phases with extraction and ellipsis. Linguistic Inquiry 45: 27–89.

Brody, Michael. 1990. Some remarks on the focus field in Hungarian.

Cable, Seth. 2010. The grammar of Q: Q-particles, Wh-Movement and Pied-Piping. London: Oxford University Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 1973. Conditions on transformations. In Essays on form and interpretation, 81–162. New York: Elsevier.

Chomsky, Noam. 1977. On wh-movement. In Formal syntax, eds. Peter Culicover, Thomas Wasow, and Adrian Akmajian. New York: Academic Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In Step by step: Essays on minimalist syntax in honor of Howard Lasnik, eds. Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka, 89–156. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Dayal, Veneeta. 1996. Locality in Wh-quantification: Questions and relative clauses in Hindi. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Dryer, Matthew S. 1991. SVO languages and the OV/VO typology. Journal of Linguistics 27: 443–482.

Elfner, E. 2012. Syntax-prosody interactions in Irish. Doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Engdahl, Elisabet. 1983. Parasitic gaps. Linguistics and Philosophy 6 (1): 5–34.

Fanselow, Gisbert. 2007. The restricted access of information structure to syntax: A minority report. In The notions of information structure, eds. Caroline Féry, Gisbert Fanselow, and Manfred Krifka. Working papers of SFB632: Interdisciplinary studies on information structure. Potsdam: Universitätsverlag Potsdam.

Féry, Caroline. 2009. Indian languages as intonational ‘phrase languages’. Ms., University of Potsdam.

Féry, Caroline. 2011. German sentence accents and embedded prosodic phrases. Lingua 121: 1906–1922.

Frascarelli, Mara, and Francesca Ramaglia. 2013. ‘phasing’ contrast at the interfaces: A feature-compositional approach to topics. In Information structure and agreement, eds. Victoria Camacho-Taboada, Ángel L. Jiménez-Fernández, Javier Martín-González, and Mariano Reyes-Tejedor. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Göbbel, Edward. 2007. Extraposition as PF movement. In Western Conference on Linguistics (WECOL). California State University: Department of Linguistics.

Grewendorf, Günther, and Joachim Sabel. 1999. Scrambling in German and Japanese: Adjunction versus multiple specifiers. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 17 (1): 1–65.

Hagstrom, Paul. 1998. Decomposing questions. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Hamblin, Charles. 1973. Questions in Montague grammar. Foundations of Language 10 (1): 41–53.

Hany Babu, M. T. 1997. The syntax of functional categories. PhD diss., Central Institute of English and Foreign Languages.

Harley, Heidi, and Elizabeth Ritter. 2002. Person and number in pronouns: A feature-geometric analysis. Language 78 (3): 482–526.

Hartmann, Katharina. 2013. Rightward movement in a comparative perspective, eds. Gert Webelhuth, Manfred Sailer, and Heike Walker. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Hayes, Bruce. 1990. Precompiled phrasal phonology. In The phonology-syntax connection, eds. Sharon Inkelas and Draga Zec, 85–108. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Heim, Irene, and Angelika Kratzer. 1998. Semantics in generative grammar. Malden: Blackwell.

Huang, C. T. James. 1982. Logical relations in Chinese and the theory of grammar. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Huang, C. T. James. 1984. On the distribution and reference of empty pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry 15: 531–574.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 1998. Blocking effects and the syntax of Malayalam taan. In The yearbook of South Asian languages and linguistics, ed. Rajendra Singh. 11–27. New Delhi: SAGE.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 2001. Questions and question-word incorporating quantifiers in Malayalam. Syntax 4 (2): 63–93.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 2003. Question words in focus positions. In Linguistic variation yearbook, Vol. 3, 69–99. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Jayaseelan, K. A. 2004. Question movement in some sov languages and the theory of feature checking question movement in some SOV langauages and the theory of feature checking. Language and Linguistics 5 (1): 5–27.

Kidwai, A. 2013. EX-It: On the syntax of finite clause extraposition and pronominal correlates in Hindi and Bangla. Talk given at MIT, April 25, 2013.

Kim, S. 2002. Focus matters: Two types of intervention effect. Paper presented at WCCFL XXI.

Kitahara, H. 1997. Elementary operations and optimal derivations. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kiss, Katalin É. 1998. Identificational focus versus information focus. Language 74: 245–273.

Kotek, Hadas. 2014. Composing questions. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Kratzer, Angelika, and Junko Shimoyama. 2002. Indeterminate pronouns: The view from Japanese. In Tokyo conference on psycholinguistics, ed. Yukio Otsu, Vol. 3, 1–25. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo.

Lebeaux, David. 1988. Language acquisition and the form of the grammar. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2005. Phases and cyclic agreement. In Perspectives on phases, eds. Martha McGinnis and Norvin Richards. Cambridge: MIT.

Madhavan, Punnapurtath. 2013. Multiple wh-questions and the cleft construction in Malayalam. In Cleft structures, eds. Katharina Hartmann and Tonjes Veenstra, 269–284. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Mahajan, Anoop. 1990. The A/A-bar distinction and movement theory. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Mahajan, Anoop. 1997. Rightward scrambling. In Rightward movement, eds. Dorothee Beerman, David LeBlanc, and Henk van Riemsdijk, 185–213. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Mahajan, Anoop K. 1987. Notes on wh-questions in Hindi. Paper presented at Sala, Cornell and Syracuse Universities.

Manetta, Emily. 2012. Reconsidering rightward scrambling: Postverbal constituents in Hindi-Urdu. Syntax 43 (1): 43–74.

Mathew, Rosmin. 2014. The syntactic effect of head movement: Wh and verb movement in Malayalam. PhD diss., University of Tromsø.

McCloskey, James. 2002. Resumption, successive cyclicity, and the locality of operations. In Derivation and explanation in the minimalist program, eds. Samuel David Epstein and T. Daniel Seely, 184–226. Malden: Blackwell.

Menon, Mythili. 2011. Revisiting Infinitives: The need for Tense in Malayalam. University of Tromsø. Talk at Finiteness in South Asian Languages. University of Tromsø.

Miyagawa, Shigeru. 1997. Against optional scrambling. Linguistic Inquiry 28 (1): 1–25.

Mohanan, K. P. 1982. Infinitival subjects, government, and the abstract case. Linguistic Inquiry 13 (2): 323–327.

Moulton, K. 2015. CPs: copies and compositionality. Linguistic Inquiry 45 (2): 305–342.

Müller, G. 1996. On extraposition and successive cyclicity. In On extraction and extraposition in German, eds. Uli Lutz, and Jürgen Pafel, 213–243. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Müller, Gereon. 2000. Shape conservation and remnant movement. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 30, eds. Masako Hirotani, Andries Coetzee, Nancy Hall, and Ji-yung Kim, 525–540. Amherst: GLSA.

Müller, Gereon, and Wolfgang Sternefeld. 1993. Improper movement and unambiguous binding. Linguistic Inquiry 24 (3): 461–508.

Munataka, Takashi. 2006. Intermediate Agree: Complementizer as a bridge. In Workshop on Altaic Formal Linguistics (WAFL) 3, ed. Sergei Tatevosov. Moscow: Maks Press.

Nakamura, Masanori. 1998. Reference set, Minimal Link Condition, and parameterization. In Is the best good enough?, eds. Pilar Barbosa, Danny Fox, Paul Hagstrom, Martha McGinnis, and David Pesetsky, 291–314. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Nespor, Marina, and Irene Vogel. 1986. Prosodic phonology. Dordrecht: Foris.

Nissenbaum, Jon. 2000. Covert movement and parasitic gaps. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 30, eds. Masako Hirotani, Andries Coetzee, Nancy Hall, and Ji-yung Kim, 541–556. Amherst: GLSA.

Ouhalla, Jamal. 1996. Remarks on the binding properties of wh-pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry 27 (4): 676–707.

Percus, Orin. 1997. Prying open the cleft. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 27, ed. Kiyomi Kusumoto, 337–351. Amherst: GLSA.

Pesetsky, David. 1982. Paths and categories. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Pesetsky, David. 2000. Phrasal movement and its kin. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Potsdam, Eric, and Daniel Edmiston. 2016. Extraposition in Malagasy. In 22nd Meeting of the Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association (AFLA), ed. Henrison Hsieh, 121–138. Canberra: Asia-Pacific Linguistics.

Preminger, Omer. 2012. Agreement as a fallible operation. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Reinhart, Tanya. 1998. Wh-in-situ in the framework of the Minimalist Program. Natural Language Semantics 6 (1): 29–56.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1990. Relativized minimality. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Elements of grammar, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Rizzi, Luigi. 2004. Locality and left periphery. In Structures and beyond: The cartography of syntactic structures, ed. Adriana Belletti, Vol. 3, 223–251. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rizzi, Luigi. 2006. In Wh-movement: Moving on, eds. Lisa Lai Shen Cheng and Norbert Corver, 97–133. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rizzi, Luigi, and Ur Shlonsky. 2007. Interfaces + recursion = language? Chomsky’s minimalism and the view from syntax-semantics, eds. Hans-Martin Gartner and Uli Sauerland, 115–160. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Rooth, Mats. 1985. Association with focus. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Ross, John R. 1982. Pronoun deleting processes in German. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Linguistic Society of America, San Diego, California.

Sauerland, Uli. 1996. The interpretability of scrambling. In Formal approaches to Japanese linguistics (FAJL) 2, eds. Masatoshi Koizumi, Masayuki Oishi, and Uli Sauerland. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Selkirk, Elisabeth. 2011. The syntax-phonology interface. In Handbook of phonological theory, eds. John A. Goldsmith, Jason Riggie, and Alan Yu. Oxford: Blackwell.

Selkirk, Elisabeth O. 1984. Phonology and syntax: The relation between sound and structure. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Simpson, Andrew. 2000. Wh-movement and the theory of feature-checking. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Simpson, Andrew, and Tanmoy Bhattacharya. 2003. Obligatory overt wh-movement in a wh-in-situ language. Linguistic Inquiry 34 (1): 127–142.

Simpson, Andrew, and Arunima Choudhury. 2015. The nonuniform syntax of postverbal elements in SOV languages: Hindi, Bangla, and the rightward scrambling debate. Linguistic Inquiry 46 (3): 533–551.

Srikumar, K. 1992. Question-word movement in Malayalam and GB theory. PhD diss., Osmania University, Hyderabad.

Srikumar, K. 2007. Clausal pied-piping and subjacency. In Linguistic theory and South Asian languages: Essays in honour of K.A. Jayaseelan, eds. Joseph Bayer, Tanmoy Bhattacharya, and MT Hany Babu, 53–69. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Starke, Michal. 2001. Move dissolves into merge: A theory of locality. PhD diss., University of Geneva.

Swenson, Amanda, Athulya Aravind, and Paul Marty. 2015. The expression of information structure in Malayalam. Ms., MIT.

Szabolcsi, Anna. 1981. Compositionality in focus. Acta Linguistica Societatis Linguistice Europaeae 1: 141–162.

Truckenbrodt, Hubert. 1995. Extraposition from NP and prosodic structure. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 25, ed. Jill Beckman, 503–518. Amherst: GLSA.

Wahba, Wafaa. 1991. LF movement in Iraqi Arabic. In Logical structure and linguistic structure: Cross-linguistic perspectives, eds. C.T. James Huang and Robert May, 253–276. Dordrecht: Springer.

Watanabe, Akira. 2006. Wh-movement: Moving on. In The pied-piper feature, eds. Lisa Lai Shen Cheng and Norbert Corver. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Wexler, Kenneth, and Peter Culicover. 1980. Formal principles of language acquisition. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Wiltschko, Martina. 1997. Superiority in German. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL), eds. Emily Curtis, James Lyle, and Gabriel Webster, 431–445. Stanford: Stanford Linguistics Association.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Adam Albright, Kenyon Branan, Veneeta Dayal, Sabine Iatridou, Norvin Richards, Roger Schwarzchild, Coppe van Urk, Michelle Yuan, the audience at NELS 46 and especially Danny Fox and David Pesetsky for comments and generous feedback. I am also grateful to three anonymous NLLT reviewers and the managing editor, Kyle Johnson, for extensive comments on an earlier draft. All errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aravind, A. Licensing long-distance wh-in-situ in Malayalam. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 36, 1–43 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-017-9371-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-017-9371-2