Abstract

In line with Significance Quest Theory (SQT, Kruglanski et al., 2022) and Costly Signaling Theory (CST, Zahavi, 1995), the present research aims to investigate the relationship between individual differences in ambition and support for costly (in terms of investment of personal resources) aid programs. Consistent with SQT, which holds that the quest for significance is a universal need that may lead to any type (e.g., violent or prosocial) of extreme behavior in order to satisfy it, we hypothesized that ambitious (vs. less ambitious) people are more motivated to engage in resource-intensive aid programs. In four studies (Total N = 744), both correlational (Studies 1 and 4) and experimental (Studies 2 and 3), we found a significant positive relationship between levels of ambition and support for resource-intensive aid programs; this relationship was mediated by difficulty perceived as important, i.e., the attribution of high value to difficult tasks and goals (Study 4).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Ambition is often mentioned in the academic literature with respect to career goals and professional choices. Individuals who desire to achieve high professional positions are seen as ambitious by others. However, ambition consists of more than an aspiration to high professional achievement. Ambition is a motivational construct common in many individuals, not only those who aspire to make a career and be successful in the workplace. Rather, ambition has been defined as a middle-level trait that is related to extraversion and conscientiousness (Jones et al., 2017). Judge and Kammeyer-Mueller (2012) defined ambition as “persistent and generalized striving for success, attainment, and accomplishment” (p. 759), in which ‘persistent’ means that the striving is not expected to cease to exist once a certain level of achievement is reached, and ‘generalized’ means that ambition is not restricted to a single life domain. The motivation to achieve a certain status, rank, or wealth is one characteristic of ambition (Hansson et al., 1983); as is the importance of the goal for which one is aiming. Ambitious people are strongly determined to achieve socially valued goals, so they work hard to achieve this end (Pettigrove, 2007).

Because of these characteristics, the construct of ambition has recently been incorporated into the Significance Quest Theory (SQT, Kruglanski et al., 2022). According to SQT, the quest for significance is a universal human need to have social worth, the desire to be appreciated and respected within one’s social reference group. Central to the quest for significance is its public and social nature, unlike self-esteem, which is private and individual by nature. Indeed, although the two concepts are often aligned, they often diverge within individuals, as one may have high self-esteem but feel a sense of low social worth. In this case, individuals are motivated to regain dignity and respect in society. In fact, the need for significance can be activated by significance loss, but also by an opportunity for significance gain, as is observed in ambitious individuals. The means for satisfying it depend on the sociocultural context to which one belongs and are defined by the narratives supported by and validated within one’s social network (Kruglanski et al., 2019).

Within this theoretical framework, ambition can be seen as a proxy for the quest for significance (Kruglanski et al., 2022), wherein significance can be achieved through professional accomplishments, but also in other ways consistent with the values of one’s culture.

Ambition and difficulty

Since ambitious individuals aim to do something special, that leaves a mark, they may choose many different means to achieve their goals. Because attaining social worth is of the utmost importance to them, ambitious individuals (vs. less ambitious people) may be more prone to engage in behaviors that require strong effort and investment of resources (i.e., required by difficult tasks), for the purpose of signaling personal quality to others and to increase in this way an opportunity to acquire dignity and higher social recognition, and, thus, for significance gain. For example, involvement in a resource-intensive aid program, in which one is required to organize fundraisers, participate in charity activities, and promote the program in various ways (i.e., requiring considerable resources investment in terms of time, money, effort, etc.), may be instrumentally used by an ambitious person as a means to achieve a higher social value and position. Following this reasoning, the difficulty of a given activity may play a central role in the decision of the ambitious person whether to engage in that activity.

The instrumental value of difficulty as a respected and important aspect of goal attainment is emphasized by the Costly Signaling Theory (CST, Grafen, 1990; Zahavi, 1975, 1977). According to the CST, individuals enact certain behaviors for the purpose of signaling something to others. In this view, altruistic acts are a way of publicizing desirable personal qualities or resources, yet CST does not clarify the ultimate goal which is served by such signaling. Other research, however, has indicated a clear link between costly signaling and the attainment of significance. For example, people who contribute considerable resources to their community rather than safeguarding their own personal interests indirectly recover the costs to themselves through long-term benefits such as increased opportunities to find a partner, access to resources and positive regard from others (McAndrew, 2021), increased social status (Farthing, 2005), and prestige and recognition within the community (Park et al., 2017).

According to CST, there are some characteristics that define a behavior as a “costly signal” (Smith & Bird, 2000). To be a signal, that behavior must be visible, i.e., there must be an audience observing it. Also, to be costly, the behavior must be difficult. That is, there must be an implication that a behavior results in a personal cost in terms of investment of time, money, or energy. For example, one cultural tradition of the Meriam, a Melanesian society in Australia, consists of very dangerous and time-consuming turtle hunting. This practice requires a great deal of effort, diving ability, and physical strength (i.e., many resources), but the products of the hunt are shared with other members of community without any kind of immediate reciprocity. The only gain for the hunter is the increment of social prestige (Zahavi, 1997). In this theoretical framework, the difficulty of the behavior, and ergo its costliness in terms of personal resources, is the main characteristic that gives importance and value to the behavior. Because one characteristic of ambitious people is to aim for important goals, they may view goals which are difficult to attain as more important. This perception is exemplified by the adage, “no pain, no gain.” Therefore, difficulty could be perceived as importance, as it provides high social value to the behavior and goal.

A desire to engage in difficult behaviors is inconsistent with the general tendency for individuals to enact simple behaviors because they are more confident of the result and thus of achieving their goals. However, if individuals are highly ambitious, they may be more attracted to difficulty because they believe that difficulty enables them to achieve higher, more important goals. This is also consistent with research on the martyrdom effect (Olivola & Shafir, 2013, 2018), wherein individuals are more willing to donate for a prosocial cause when they consider the donation/fundraising process as painful and effortful. This occurs because “the prospect of enduring pain and effort for charity led people to ascribe greater meaning to donating, which motivated them to donate more” (Olivola & Shafir, 2018, p. 2). The martyrdom hypothesis is consistent with the present theoretical framework, as well as with previous work (Bélanger, 2013) demonstrating that individuals who think and behave in this way also have higher levels of quest for significance, activated by both loss of significance and the opportunity to gain significance. Specifically, in a series of studies, Bélanger (2013, studies 8–10) showed that motivation to self-sacrifice for an ideology increases when individuals’ sense of personal worth is reduced, or the quest for significance is activated. Unlike previous work by Bélanger and others, however, in the present research we focused on ambition as a proxy for quest for significance, and prosocial behavior, particularly helping behavior, rather than antisocial behavior. Within the SQT and CST frameworks, we might concisely explain this phenomenon thusly: individuals with a high level of ambition – which is a specific aspect of the quest for significance – want to gain more respect, value, and social recognition, and their motivation might lead them to engage in costly behaviors because they see difficulty as a means to achieve their ultimate goal of significance. In other words, more ambitious individuals may think that if they are involved in very difficult behaviors, they will be more likely to receive more significance.

In their work on experienced difficulty, Fisher and Oyserman (2017) argue that the most common interpretation of difficulty is the implication of impossibility, meaning that the odds of success are low (i.e., “I don’t know this, or cannot learn it, this is not for me,” p. 134), and thus people are less motivated to engage in such behaviors. However, there is a less common interpretation of difficulty, which is when difficulty implies importance, because the value of task is high (i.e., “I really care about this, ‘no pain, no gain,’ this is for me,” p. 134). Presently, we argue that this interpretation of difficulty (i.e., difficulty-as-importance) is typical of ambitious individuals, and that they are consequently more motivated to engage in such costly/difficult behaviors.

Helping behavior as extreme behavior

The presently described studies are focused on resource-intensive helping behavior as a type of extreme behavior. Kruglanski and colleagues (2021) argue that two main characteristics define an event or a state as extreme: rarity, because extreme phenomena are infrequent, and intensity, because their underlying motivation is characterized by pronounced magnitude. Based on these characteristics, any behavior can become extreme when the underlying motivation becomes predominant, overriding other individual needs (Kruglanski et al., 2021). In this view, even helping behavior could be called extreme when individual resources (in terms of time, money, and effort) are focused on enacting that behavior at the expense of other goals. Since individual resources are limited, engaging in this type of behavior inevitably means sacrificing others. For example, support for an aid program that requires a direct personal involvement in program activities (e.g., promoting the program in various ways, participating in charity activities, and/or organizing fundraisers, etc.), may fall under the definition of extreme behavior if individuals overwhelmingly devote their free time, efforts, and other resources to supporting the program.

Past research has shown that the quest for significance, including high levels of ambition as its proxy (Resta et al., 2022a), may lead to extreme behaviors (e.g., Jasko et al., 2017; Kruglanski et al., 2013; Webber et al., 2017), but there are no studies focusing on the relationship between ambition and (extreme) helping behavior, and on the mediating role of difficulty-as-importance. Previous studies of the relationship between costs and helping behavior showed that the higher the perceived cost of helping, the less people are motivated to help (e.g., Sargeant &Woodliffe, 2007; Wiepking & Breeze, 2012), suggesting that, generally, people are more likely to help when significant self-sacrifice is not required. However, we assume that when the difficulty is high (i.e., higher cost and resources required), ambitious people are more likely to engage because of their higher motivation to attain significance.

The present research

Through four studies, both correlational (Studies 1 and 4) and experimental (Studies 2 and 3), we aimed to empirical test the following two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

There will be a positive relationship between high levels of ambition and support for resource-intensive aid programs.

Hypothesis 2

The perception of difficulty as important will mediate the relationship between levels of ambition and support for resource-intensive aid programs.

Study 1

In accordance with Hypothesis 1, our first study aimed to verify the basic relationship between the individual differences in ambition and support for resource-intensive aid programs.

Method

Participants

One hundred participants were recruited online through a paid procedure provided by Prolific. All participants were American adults (51% male) aged 18 to 58 years (M = 33.77, SD = 10.90). 36% of participants had a bachelor’s degree, 28% had a master’s degree, 15% had a high school diploma or equivalent, 12% had a vocational education, 3% had a PhD, and 6% reported “other” with regard to their educational attainment. After giving their informed consent, participants completed an online questionnaire through Qualtrics comprised of the measures described below. The requisite sample size was calculated through G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2009), assuming a medium effect size, power of 80%, and alpha of 0.05. Results indicated a required sample of at least 55 participants. We recruited a larger sample to detect any minor effects.

Instruments

Ambition

Individuals’ ambition was assessed through the Ambition Scale (Resta et al., 2022a, b), in which participants were asked to indicate their degree of agreement with statements, using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“Definitely disagree”) to 5 (“Definitely agree”). This scale consists of 10 items regarding personal goals and characteristics of ambitious individuals (e.g., “One of my goals is doing something that leaves a mark”). High scores indicate high levels of ambition (M = 3.58; SD = 1.01). Internal consistency reliability was excellent in this sample (α = 0.94).

Index of support

Participants were presented with the following scenario, previously used by Kossowska and colleagues (2020), describing children with a rare disease:

Dear Participant, the Institute of Psychology is currently supporting money-raising programs to save sick children, whose story you can read below. A group of five children who suffer from a serious kidney condition are now in the hospital. The condition will soon lead to a kidney failure which will put the children’s life in danger. For medical reasons, a kidney transplant is impossible as is hemodialysis. Recently, however, a medication which can stop the disease was discovered. Unfortunately, the treatment is very expensive. If the necessary amount is not collected in the very near future, the progress of the disease will be so advanced that it will be impossible to save these children.

They were then told that they could help these children by supporting one of two different aid programs. Both of them required a donation, but Program A also required direct personal involvement in the program activities (e.g., promote the program in various ways, participate in charities organized on the weekend, and/or organize fundraisers, etc.), while Program B did not require a direct personal involvement. Participants were asked to indicate their preference/support for one program over the other, from 1 (Strong Preference for Program A) to 6 (Strong Preference for Program B), and their willingness to support one over the other, from 1 (Very Willing for Program A) to 6 (Very Willing for Program B). These two items were highly correlated (r = .84, p < .001), so, after having properly reversed them, we used their averaged scores as the support index, wherein higher scores indicated more support for the resource-intensive aid program (Program A) over the resource-non-intensive program (Program B) (M = 2.42; SD = 1.54).

Check

Participants were asked to answer the following questions for both Program A and Program B: In your opinion, how difficult would it be for a person to support this program?, and In your opinion, how costly (in terms of money, time, effort, etc.) is it for a person to support this program?, using a response scale from 1 (Not at all) to 6 (Completely). Then we computed two composite scores (one for Program A and one for Program B) by averaging the responses to each item (r for Program A = 0.34, p < .001; r for Program B = 0.36, p < 001).

Data analysis

First, we tested the perception of participants of the difficulty and costliness of the programs presented through a paired t-test. We then performed a regression analysis in order to test the relationship between the ambition scale (IV) and support for the more resource-intensive aid program (DV).

Results

The results from the paired t-test showed that there was a significant difference on participants’ perception of difficulty and costliness between the two programs (t = 12.79; p < .001), indicating that Program A (M = 3.74; SD = 0.89) was perceived as more difficult and more costly than Program B (M = 2.21; SD = 1). To ensure that the perception of the cost of programs was not affected by participants’ level of ambition, we calculated the difference in perceived programs’ difficulty and costliness (i.e., Program A minus Program B), and regressed the obtained scores on ambition. The results showed that the relationship was not statistically significant (b = − 0.10, p = .384).

More importantly, the regression analysis conducted to test Hypothesis 1 showed that individuals high in ambition were more likely to support the more resource-intensive aid program (e.g., Program A; b = 0.33, p = .033) Notably, the results remained the same after controlling for age, gender, and educational level.

Discussion

Study 1 provided initial correlational support for Hypothesis 1, suggesting that more ambitious people are more supportive of aid programs which require a higher degree of personal involvement. This result aligns with the idea that extreme behavior is in part defined by the predominance of the given behavior over behaviors aimed at achieving other goals. Prosocial behavior is not necessarily extreme, of course, but can be considered extreme when the individual engages in it at the expense of their other needs, including by devoting one’s limited resources to others, as was required in Program A but not Program B. This study is limited, however, in its correlational nature. One cannot draw causal inferences regarding the relationship between ambition and support for resource-intensive prosocial behaviors. Moreover, this study did not take into account the possibility that prosocial behavior is due to individual altruistic tendencies (i.e., one being primarily motivated by concern for the needs and welfare of others) rather than personal ambition. Study 2 aimed to address these limitations manipulating the IV (i.e., ambition) variable and measuring altruistic tendency.

Study 2

In Study 2, the ambition was experimentally manipulated through a recall task with the aim of testing its causal role in the relationship with support for resource-intensive aid programs. Altruism was included in the analysis as control variable.

Method

Participants

We recruited 146 American adults through Prolific (49.3% female) aged 19–74 years (M = 39.16, SD = 14.06). Of the participants, 35.6% had a high school diploma or equivalent, 33.6% had a bachelor’s degree, 13.7% had a vocational education, 10.3% had a master’s degree, 1.4% had a PhD, and 5.5% reported “other.” After we obtained their informed consent, participants were randomly assigned to two experimental conditions and then completed the measures of support for the aid programs, altruism, and a manipulation check. The sample size was calculated through G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2009), assuming a medium effect size, power of 80% and alpha of 0.05. Results showed us that we needed a sample of at least 128 participants.

Instruments

Manipulation of ambition

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions. Using a modified version of recall paradigm used by Avnet and Higgins (2003; see also Bélanger et al., 2022), in both conditions, individuals were asked to recall and to carefully describe two situations. In the experimental condition, using items from ambition scale used in Study 1, participants were first asked to carefully describe a situation in which they aimed to do something important, special, that leaves a mark. Second, they were asked to carefully describe a situation in which they tried to stand out from others in what they did. In the control condition, participants were first asked to describe what constituted their last meal and then to carefully describe their typical day.

Manipulation check

After the experimental manipulation, participants were asked to indicate their degree of agreement with three items (i.e., “One of my goals is doing something that leaves a mark”, “I aspire to do something special” and “I always try to stand out in what I do”) from the Ambition Scale previously used in Study 1 and from which the experimental condition for the present study was derived. The mean score of these items was 3.35 (SD = 0.99, α = 0.82).

Index of support

After reading the scenario previously used in Study 1, participants were asked to indicate their preference/support and willingness to support the program A over the program B, using the same response scale of the first study. As in the previous study, because these two items were highly correlated (r = .86, p < .001), we reversed them and used their averaged scores as the support index, wherein higher scores indicated more support for the resource-intensive aid program (Program A) over the resource-non-intensive program (Program B) (M = 2.46; SD = 1.41).

Check

To verify that participants perceived the different difficulty and costliness of the programs presented, we used the same questions used in the previous study. As in Study 1, we computed two composite scores (one for Program A and one for Program B) averaging the responses to each item (r for Program A = 0.35, p < .001; r for Program B = 0.30, p < 001).

Altruism

We used a sub-scale of Prosocial Tendencies Measures (PTM, Carlo & Randall, 2002) as measure of altruism, consisting of 5 items (e.g., “I feel that if I help someone, they should help me in the future” – reverse item) with a 5-point Likert response scale, from 1 (Does not describe me at all) to 5 (Describes me greatly) (α = 0.86).

Data analysis

First, we tested manipulation check through a one-way ANOVA in order to verify whether there were differences in participants’ ambition levels between the two conditions. Then we tested the participants’ perception of the difficulty and costliness of the aid programs through a paired t-test. To verify Hypothesis 1 and the causal role of ambition variable, we tested the support for the resource-intensive aid program based on participants’ exposure to the experimental or control condition through a one-way ANOVA, including altruism as a covariate. In addition, we also tested the interaction between altruism and experimental (vs. control) condition by using Process macro version 3.5.3 (Hayes, 2018), model 1. All analyses were performed with SPSS.

Results

Results from the manipulation check showed that there was a significant difference in participants’ ambition between the two conditions (F = 7.44, p = .007), indicating that the participants’ levels of ambition in the experimental condition (M = 3.58; SD = 0.93) were higher than in control condition (M = 3.14; SD = 0.99). Significant differences were also found from the paired t-test (t = 16.28; p < .001), showing that participants perceived Program A (M = 3.62; SD = 0.84) to be more difficult and more costly than Program B (M = 1.98; SD = 0.81). A one-way ANOVA was conducted to check whether manipulation of ambition influenced the participants’ perception of difficulty and costliness of programs. The results showed that the effect was not statistically significant (F = 0.83, p = .364), indicating that there were not differences in perception of programs between the two experimental conditions.

Descriptive statistics and correlations between the variables are presented in Table 1.

In line with Hypothesis 1, the results of the one-way ANOVA showed that there was a significant main effect of condition on support for the aid program (F = 5.43, p = .021), indicating that individuals in the experimental condition (M = 2.71) supported the resource-intensive aid program more that individuals in control condition (M = 2.18). The effect of altruism included as covariate was not significant (F = 0.36, p = .552), and the results were unchanged (F = 5.39, p = .022). Similarly, the moderation analysis showed a non-significant main effect of altruism (p = .731) and a non-significant interaction effect of altruism and experimental (vs. control) condition (p = .137) on support for the resource-intensive aid program. Conversely, the main effect of the experimental (vs. control) condition remained significant (b = 0.27, p = .021) when controlling for altruism.

Discussion

Study 2 builds upon the results of Study 1 by providing additional support for Hypothesis 1 and specifying a causal role of ambition in the relationship tested. Specifically, when ambition was activated through the exposure to the experimental condition, participants were more likely to support the resource-intensive aid program than the resource-non-intensive program. This pattern of results suggests that high levels of ambition can lead people to engage in costly prosocial behavior, in line with SQT and CST, as discussed above. In addition, the results controlled for altruism, indicating that the effect of ambition on prosocial behavior exists regardless of individual altruistic tendencies. However, this study did not allow us to clarify whether it was the high cost/difficulty of the program that induced ambitious people to support it. In Study 3, we addressed this limitation by exposing participants to only the high resource-intensive program or to the resource-non-intensive program and asked them to indicate their support for it, after measuring their level of ambition.

Study 3

In Study 3, we used an experimental condition (resource-intensive vs. resource-non-intensive aid program) as a moderator in the relationship between levels of ambition and support for the program.

Method

Participants

We recruited 301 American adults through Prolific (74.8% female) aged 18–65 years (M = 27.58, SD = 8.43). Of them, 35.5% had a bachelor’s degree, 28.6% had a high school diploma or equivalent, 18.6% had a master’s degree, 5% had a vocational education, 2.3% had a PhD, and 10% reported “other.” After we obtained their informed consent, participants were randomly assigned to two experimental conditions and then completed the measure of support and the ambition scale used in Study 1 through Qualtrics. The sample size was calculated through G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2009), assuming a medium effect size, power of 80% and alpha of 0.05. Results showed us that we needed a sample of at least 128 participants. Following the suggestions of Aberson and colleagues (2020) for calculating the sample size in the moderation model, we considered a sample size of 2 N, so we would have to recruit at least 256 participants.

Instruments

Ambition

The Ambition Scale is the same as that used in Study 1 (α = 0.90; M = 3.54, SD = 0.81).

Experimental condition

Participants were asked to read the same scenario used in Study 1, but instead of being exposed to both programs, participants were only presented one or the other, depending on their condition (resource-intensive or resource-non-intensive program). One hundred and fifty participants were randomly assigned to the non-intensive condition (i.e., The Program requests a free donation, but it does not require direct personal involvement in the program activities, contrast coded = -1) and 151 were assigned to the resource-intensive condition (i.e., The Program requests a free donation and requires direct personal involvement in the program activities (e.g., you will be required to promote the program in various ways, participate in charities organized on the weekend, and/or organize fundraisers, etc., contrast coded = 1).

Index of support

After reading the scenario, participants were asked to indicate their willingness to support the program, using a response scale from 1 (Very unwilling) to 6 (Very willing).

Manipulation check

Participants were asked to answer the following questions: In your opinion, how difficult would it be for a person to support this program?, and In your opinion, how costly (in terms of money, time, effort, etc.) is it for a person to support this program?, using a response scale from 1 (Not at all) to 6 (Completely). Then we averaged the responses to the two items (r = .45, p < .001).

Data analysis

First, we tested the manipulation check through a one-way ANOVA. Next, we performed correlation and moderation analyses. We tested a moderation model with the level of ambition as the IV, the manipulation as the moderator, and the support for the program as the DV. The analyses were performed with the use of Process macro for SPSS version 3.5.3 (Hayes, 2018), model 1. 5,000 bootstrap samples were used in the analysis.

Results

Results from the manipulation check showed that there was a significant difference between the two experimental conditions (F = 17.09, p < .001). Specifically, the resource-intensive condition (M = 3.42; SD = 1.07) was perceived as more difficult and more costly than the resource-non-intensive condition (M = 2.92; SD = 1.03). In addition, ambition did not have a significant relationship with the perceived difficulty and costliness of programs (r = .04, p = .486).

Descriptive statistics and correlations between the variables are presented in Table 2.

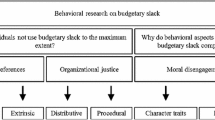

The results of moderation analysis showed a significant and positive main effect of ambition on support for the aid program (b = 0.17, SE = 0.08, t = 2.29, 95% CI [0.024, 0.323], p = .023), with individuals high in ambition more inclined to support the aid programs, regardless of difficulty and costliness. We also found a significant and negative main effect of experimental condition on the dependent variable (b = − 0.21, SE = 0.06, t = − 3.32, 95% CI [− 0.327, − 0.084], p = .001), with the resource-non-intensive condition more supported than resource-intensive condition. This result is consistent with studies of the relationship between costs and helping behavior showing that the higher the perceived cost of helping, the less people are motivated to help (e.g., Sargeant &Woodliffe, 2007; Wiepking & Breeze, 2012). More importantly, we found a positive and significant effect of the interaction between ambition and condition on support for the aid program (b = 0.19, SE = 0.08, t = 2.53, 95% CI [0.043, 0.342], p = .012). The simple slopes analysis revealed that the effect of ambition on support for the aid program was positive and significant in resource-intensive condition (b = 0.37, SE = 0.11, t = 3.43, 95% CI [0.156, 0.575], p < .001), while this effect became non-significant in the resource-non-intensive condition (b = -0.02, SE = 0.11, t = -0.17, 95% CI [− 0.232, 0.195], p = .861). This pattern of results suggests that when the cost/difficulty was low, all people generally tended to support the aid program, regardless of their level of ambition (see Sargeant &Woodliffe, 2007, and Wiepking & Breeze, 2012), but when the cost/difficulty was high, only more ambitious individuals tended to support that behavior. Results are displayed on Fig. 1. As in Study 1, the results remained the same after controlling for age, gender, and educational level.

Discussion

Study 3 builds upon the results of Studies 1 and 2 by providing additional support for Hypothesis 1 and specifying that there is indeed a causal relationship of the high cost/difficulty of a particular aid program and ambitious people’s support for it. Put simply, when charitable behavior is not difficult or costly, most people tend to support it, but when the cost of charitable behavior is high, highly ambitious people are more likely to support it. Study 3 is not without limitations, however. In particular, none of the three studies provides an explanation as to why ambitious people are more likely to support resource-intensive prosocial behaviors. Study 4 aimed to address this limitation by testing Hypothesis 2, that ambitious people are more supportive of costly prosocial behaviors because they perceive the difficulty by which these behaviors are characterized as important. Ambitious people aim for important goals, so if they perceive difficulty as important, they are more likely to engage in difficult behaviors.

Study 4

In Study 4, we introduced the difficulty being perceived as important as a potential mediator of the relationship between levels of ambition and support for a resource-intensive aid program (i.e., support for program that required a direct involvement of personal resources, e.g., time, effort, etc.).

Method

Participants

One hundred and ninety-seven American adults (different from previous studies) were recruited through Prolific (73.6% female) aged 18 to 64 years. Their mean age was 28.14 years (SD = 8.85). Of the participants, 38.6% had a bachelor’s degree, 24.4% had a master’s degree, 24.4% had a high school diploma or equivalent, 6.6% had a vocational education, 0.5% had a PhD, and 5.6% reported “other.” All participants gave informed consent and then completed an online questionnaire through Qualtrics consisting of the measures used in Study 1, with the addition of a measure of difficulty perceived as important. The sample size was calculated through the tool by Schoemann et al. (2017). Setting power to 80% and assuming medium effect sizes, a sample of at least 160 participants was suggested by 5,000 Monte Carlo simulations.

Instruments

Ambition

The Ambition Scale was the same as the previous two studies (α = 0.88; M = 3.65; SD = 0.76),

Index of support

Participants were presented with the same scenario as was used in Study 1 and 2. They were then told that they could help the aid target involved in the scenario (i.e., the children who suffer from a serious kidney condition) by supporting one of the same two different aid programs (Program A and Program B). As in Study 1 and 2, participants were asked to indicate, using the same two items, their preference/support for one program over the other. The index of support was obtained averaging the responses to each item (r = .85, p < .001; M = 2.79; SD = 1.56): Higher scores indicated higher support for the resource-intensive aid program (Program A) than non-intensive program (Program B).

Check

To verify the participants’ perception of the different difficulty and costliness of the programs presented, we asked participants to answer, for both Programs A and B, the same questions used in Study 1 and 2. Similarly, we computed two composite scores (one for Program A and one for Program B) by averaging the responses to each item (r for Program A = 0.37, p < .001; r for Program B = 0.55, p < 001).

Interpretation of experience scale

We used a subscale of Interpretation of Experience Scale (Fisher & Oyserman, 2017) to assess difficulty perceived as important (i.e., “difficulty-as-importance”). This subscale consists of six items (e.g., “If a task feels difficult, my gut says that it really matters for me,” “When a goal feels difficult to attain, then it is probably worth my effort,” and “When taking the steps towards a goal feels difficult, I’m likely to think that the goal is very important”), and participants were asked to indicate their agreement for each statement, using a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (Totally disagree) to 6 (Totally agree). High scores indicate high perception of difficulty as important (M = 3.82, SD = 1.10). In this sample, internal reliability was excellent (α = 0.93).

Data analysis

We tested participants’ perception of the difficulty and costliness of the programs presented through a paired t-test. We then performed correlation analyses and, finally, we tested a mediation model in which the ambition was the IV, difficulty-as-importance was the mediator, and the index of support was the DV. The analyses were performed using Process macro for SPSS version 3.5.3 (Hayes, 2018), model 4. 95% CIs were employed and 5,000 bootstrapping resamples were run.

Results

Results from the paired t-test showed that there were significant differences on participants’ perception of the difficulty and costliness of the two programs (t = 12.47; p < .001), indicating, again, that Program A (M = 3.52; SD = 0.92) was perceived as more difficult and more costly than Program B (M = 2.24; SD = 1.10). As in Study 1, with the aim of excluding the possible explanation that perceptions of program difficulty and costliness were influenced by participants’ level of ambition, we regressed the difference in perceived cost on ambition. As expected, the result was not statistically significant (b = − 0.21, p = .131).

Descriptive statistics and correlations between variables are presented in Table 3.

The results of the mediation analysis showed that ambition had a significant and positive effect on perception of difficulty-as-importance (b = 0.81, SE = 0.09, t = 9.32, 95% CI [0.638, 0.980], p < .001), which, in turn, had a significant and positive effect on support for the resource-intensive aid program (b = 0.27, SE = 0.12, t = 2.24, 95% CI [0.032, 0.502], p = .026). More important, and consistent with our mediation hypothesis, the indirect effect of ambition on support for the resource-intensive aid program through difficulty-as-importance was significant and positive (indirect effect = 0.22, 95% CI [0.034, 0.373]). The total effect of ambition on support for the resource-intensive aid program was positive and significant (b = 0.30, SE = 0.15, t = 2.05, 95% CI [0.012, 0.586], p = .042), whereas the direct effect was not significant (b = 0.08, SE = 0.17, t = 0.48, 95% CI [-0.259, 0.425], p = .633) when including the mediator, meaning that the relationship between ambition and support for the resource-intensive aid program was completely mediated by difficulty-as-importance. Overall, the mediation model was significant, F(2,194) = 4.66, R2 = 0.05, p = .011. As in the previous studies, the results remained the same after controlling for age, gender, and educational level. The results obtained from the analysis are summarized in Fig. 2.

In order to demonstrate that ambition drives the effect on support for the resource-intensive aid program demonstrated above, we also tested the alternative model in which difficulty-as-importance predicted ambition, which, in turn, predicted support for resource-intensive aid program. As expected, the results showed no significant indirect effect of difficulty-as-importance on support for resource-intensive aid program through ambition (indirect effect = 0.03, 95% CI [-0.085, 0.158]).

Discussion

Study 4 provides support for Hypothesis 2 and expands upon the findings of the previous three studies. Specifically, we found in Study 4 that the relationship found in Study 1, 2 and 3, that ambitious people are more supportive of resource-intensive prosocial behaviors, is completely explained by ambitious people’s perceptions of difficulty as important. This indicates that the results of Study 2 and 3, that high levels of ambition and high cost of a particular prosocial behavior caused individuals to support it more, are explained completely by ambitious people’s perception that behaviors which are resource-intensive, and hence more costly and difficult, are more important, and they are thus more supportive of them. In contrast, people who are less ambitious do not support more resource-intensive prosocial behaviors not because they are not prosocial, or because they do not have a need for significance, which is universal, but rather because they do not perceive difficult goals as important. Thus, their need for significance is not activated by exposure to difficult behaviors and they are not prompted to support those behaviors. However, this study is not without limitations. First, although we have shown that ambition drives the effect by testing the alternative model using difficulty-as-importance as the IV and ambition as the mediator, this was nevertheless a correlational study and we cannot infer a causal relationship between variables, which can be demonstrated only through longitudinal or experimental studies.

General discussion

In four studies, both correlational (Study 1 and 4) and experimental (Studies 2 and 3), our hypotheses were supported. First, we found that there is a significant and positive relationship between individuals’ level of ambition and support for a resource-intensive aid program, in line with Hypothesis 1. Furthermore, the experimental nature of Study 2 suggests a causal role of ambition (conceptualized as a proxy for quest for significance) in this relationship. Specifically, when ambition was activated in the experimental (vs. control) condition, people expressed more support for a resource-intensive and high-cost prosocial behavior because of their high level of ambition, and thus their high need for significance. Again because of its experimental nature, Study 3 showed a causal role of resource-intensiveness as a moderator of the relationship between ambition and support for a given aid program. Specifically, the results suggested that people generally tended to support the aid program when the cost was perceived as low, but only ambitious individuals supported the aid program when the cost was high. In addition, our findings showed that the relationship between levels of ambition and support for resource-intensive aid programs was mediated by ambitious individuals’ perception of difficulty as important, in line with Hypothesis 2. This suggests that people oriented toward goals of success and achievement (i.e., with high levels of ambition) are more supportive of costly/difficult aid programs that require a greater commitment of resources (i.e., time, effort, energy) because they place more value and importance on more difficult tasks and goals. According to SQT (Kruglanski et al., 2022), these individuals may have a greater desire to gain social respect and recognition (i.e., significance), and in order to attain this, they enact behaviors which are socially accepted and rewarded (Kruglanski et al., 2019).

This study makes a novel contribution to the literature in several ways. First, although there is ample research on helping behavior and specifically on motivation to help through monetary donations (e.g., Smith & McSweeney, 2007; Shearman & Yoo, 2007), there are few studies focusing on other types of prosocial costs, such as the willingness to donate one’s time to participate in volunteer activities (Ein-Gar & Levontin, 2013). Moreover, to our knowledge, there have been no studies investigating the relationship between motivation, particularly the construct of ambition, and support for an aid program which is costly in terms of individual resources such as time and energy. In addition, as a second important novelty aspect, we introduced a mediator (i.e., difficulty-as-importance) in explaining this relationship, showing that perceiving difficult behaviors as more important seems to play a central role in ambitious peoples’ chosen means to attaining their goals. Furthermore, this research contributes to studies of the construct of ambition. Recently, Resta and colleagues (2022a) found a relationship between high levels of ambition and extreme behavior generally, but the present work is the first study to apply this result in the specific context of helping behavior, as well as the first to experimentally manipulate ambition. In addition, assuming that ambition is a proxy for the quest for significance, the present research makes a contribution to the literature related to incentivization (i.e., the opportunity for gain) activating the need for significance. The existing literature has focused primarily on deprivation (i.e., loss or threatened loss of significance). Indeed, most studies of the relationship between the quest for significance and extreme behaviors are related to terrorism, showing that the deprivation of significance may activate attempts to restore it in several ways, including by engaging in extremist violence (e.g., Jasko et al., 2017; Kruglanski et al., 2013; Webber et al., 2017). In contrast, the present research considered the quest for significance from the perspective of gain rather than loss through the concept of ambition as theorized by Kruglanski and colleagues (2022). Finally, because we conceptualized resource-intensive helping behavior as extreme behavior following the reasoning discussed previously, these studies extend the research on extremism by investigating prosocial behaviors instead of antisocial/violent behaviors that have been typically cited as examples of extremism.

In the present research, we focused on a specific type of extreme behavior (i.e., involvement in resource-intensive aid programs), but in order to generalize our results to a wider range of contexts, future research should replicate the models with several dependent variables representing other kinds of extreme behaviors, especially prosocial (e.g., heroic) behaviors. Furthermore, the next step in this line of research is to consider and manipulate the public (vs. anonymous) dimension in interaction with the difficulty dimension, as theorized by CST (Smith & Bird, 2000), to test whether the ambitious are more likely to support a resource-intensive aid program when their contribution is visible to others. In line with the SQT and the hypotheses tested in the presently described studies, individuals with higher levels of ambition may be more likely to support an aid program when it is difficult and visible, with the ultimate goal of gaining respect and recognition (i.e., significance) within their social network, as supporting such difficult programs anonymously would not allow them to attain such respect from others. Future studies will include this variable in analyses, as well as a measure of social worth and recognition that participants expected to gain (i.e., significance gained measure) if they were engaged in costly behaviors.

Overall, the present research helps to connect SQT and CST, given their commonalities, with the aim of providing empirical support to idea that some behaviors, especially extreme ones and even extreme helping behaviors, are driven primarily by the universal need for significance. These two reference theories may also help to explain the martyrdom effect, which holds that the expectation of pain and effort increases one’s willingness to contribute prosocially because it increases the meaning and value of the contribution (Olivola & Shafir, 2013). In the authors’ words, “the fact that people will make sacrifices (both physical and financial) for a cause, even when they stand to gain nothing tangible in return, leads us to conclude that the motivation to suffer for a cause deserves further study” (Olivola & Shafir, 2013, p. 104). Therefore, through the present work, we also attempted to extend this perspective by introducing the basic motivational component underlying the martyrdom effect, namely, the need for significance. Following our reasoning, the increased value of the contribution indicates a more effective means to achieve the ultimate goal of significance.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aberson, C. L., Bostyn, D. H., Carpenter, T., Conrique, B. G., Giner-Sorolla, R., Lewis, N. A. Jr., Montoya, A. M., Ng, B. W., Reifman, A., Schoemann, A. M., & Soderberg, C. (2020). Techniques and solutions for sample size determination in psychology: Supplementary material for “power to detect what? Considerations for planning and evaluating sample size.” (unpublished manuscript).

Avnet, T., & Higgins, E. T. (2003). Locomotion, assessment, and regulatory fit: Value transfer from how to what. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39(5), 525–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1031(03)00027-1.

Bélanger, J. (2013). The psychology of martyrdom. University of Maryland.

Bélanger, J. J., Adam-Troian, J., Nisa, C. F., & Schumpe, B. M. (2022). Ideological passion and violent activism: The moderating role of the significance quest. British Journal of Psychology, 113(4), 917–937. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12576.

Carlo, G., & Randall, B. A. (2002). The development of a measure of prosocial behaviors for late adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31, 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014033032440.

Ein-Gar, D., & Levontin, L. (2013). Giving from a distance: Putting the charitable organization at the center of the donation appeal. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 23(2), 197–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2012.09.002.

Farthing, G. W. (2005). Attitudes toward heroic and nonheroic physical risk takers as mates and as friends. Evolution and Human Behavior, 26(2), 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2004.08.004.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160.

Fisher, O., & Oyserman, D. (2017). Assessing interpretations of experienced ease and difficulty as motivational constructs. Motivation Science, 3(2), 133–163. https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000055.

Grafen, A. (1990). Biological signals as handicaps. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 144(4), 517–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5193(05)80088-8.

Hansson, R. O., Hogan, R., Johnson, J. A., & Schroeder, D. (1983). Disentangling type A behavior: The roles of ambition, insensitivity, and anxiety. Journal of Research in Personality, 17(2), 186–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-6566(83)90030-2.

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. The Guilford Press.

Jasko, K., LaFree, G., & Kruglanski, A. (2017). Quest for significance and violent extremism: The case of domestic radicalization. Political Psychology, 38(5), 815–831. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12376.

Jones, A. B., Sherman, R. A., & Hogan, R. T. (2017). Where is ambition in factor models of personality? Personality and Individual Differences, 106, 26–31.

Judge, T. A., & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. (2012). On the value of aiming high: The causes and consequences of ambition. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(4), 758–775. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028084.

Kossowska, M., Szumowska, E., Szwed, P., Czernatowicz-Kukuczka, A., & Kruglanski, A. W. (2020). Helping when the desire is low: Expectancy as a booster. Motivation and Emotion, 44(6), 819–831. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-020-09853-3.

Kruglanski, A. W., Bélanger, J. J., Gelfand, M., Gunaratna, R., Hettiarachchi, M., Reinares, F., & Sharvit, K. (2013). Terrorism—A (self) love story: Redirecting the significance quest can end violence. American Psychologist, 68, 559–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032615.

Kruglanski, A. W., Bélanger, J. J., & Gunaratna, R. (2019). The three pillars of radicalization: Needs, narratives and networks. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190851125.001.0001.

Kruglanski, A. W., Szumowska, E., Kopetz, C. H., Vallerand, R. J., & Pierro, A. (2021). On the psychology of extremism: How motivational imbalance breeds intemperance. Psychological Review, 128(2), 264–289. https://doi.org/10.1037/rev0000260.

Kruglanski, A. W., Molinario, E., Jasko, K., Webber, D., Leander, N. P., & Pierro, A. (2022). Significance-Quest Theory. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916211034825.

McAndrew, F. T. (2021). Costly signaling theory. Encyclopedia of evolutionary psychological science, 1525–1532. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19650-3.

Olivola, C. Y., & Shafir, E. (2013). The martyrdom effect: When pain and effort increase prosocial contributions. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 26(1), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.767.

Olivola, C. Y., & Shafir, E. (2018). Blood, sweat, and cheers: The martyrdom effect increases willingness to sponsor others’ painful and effortful prosocial acts. Available at SSRN 3101447.

Park, J., Chae, H., & Choi, J. N. (2017). The need for status as a hidden motive of knowledge-sharing behavior: An application of costly signaling theory. Human Performance, 30(1), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2016.1263636.

Pettigrove, G. (2007). Ambitions. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 10(1), 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-006-9044-4.

Resta, E., Ellenberg, M., Kruglanski, A. W., & Pierro, A. (2022a). Marie Curie vs. Serena Williams: Ambition leads to extremism through obsessive (but not harmonious) passion. Motivation and Emotion, 46(3), 382–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-022-09936-3.

Resta, E., Ellenberg, M., Kruglanski, A. W., & Pierro, A. (2022b). The Ambition Scale: Italian and English Validation. [Unpublished Manuscript].

Sargeant, A., & Woodliffe, L. (2007). Gift giving: An interdisciplinary review. International Journal of Nonproft and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 12(4), 275–307. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.308.

Schoemann, A. M., Boulton, A. J., & Short, S. D. (2017). Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8, 379–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617715068.

Shearman, S. M., & Yoo, J. H. (2007). Even a penny will help! Legitimization of paltry donation and social proof in soliciting donation to a charitable organization. Communication Research Reports, 24(4), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824090701624148.

Smith, E. A., & Bird, R. L. B. (2000). Turtle hunting and tombstone opening: Public generosity as costly signaling. Evolution and Human Behavior, 21(4), 245–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1090-5138(00)00031-3.

Smith, J. R., & McSweeney, A. (2007). Charitable giving: The effectiveness of a revised theory of planned behaviour model in predicting donating intentions and behaviour. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 17(5), 363–386. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.906.

Webber, D., Klein, K., Kruglanski, A., Brizi, A., & Merari, A. (2017). Divergent paths to martyrdom and significance among suicide attackers. Terrorism and Political Violence, 29, 852–874. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2015.1075979.

Wiepking, P., & Breeze, B. (2012). Feeling poor, acting stingy: The effect of money. Perceptions on charitable giving. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 17, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.415.

Zahavi, A. (1975). Mate selection—a selection for a handicap. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 53(1), 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-5193(75)90111-3.

Zahavi, A. (1977). Reliability in communication systems and the evolution of altruism. Evolutionary ecology (pp. 253–259). Palgrave.

Zahavi, A., & Zahavi, A. (1997). The Handicap Principle: A missing piece of Darwin’s puzzle. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/auk/117.1.

Funding

No funding was received for conducting this study.

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Miss. Marta Viola and Dr. Antonio Pierro. The frst draft of the manuscript was written by Miss. Marta Viola. Reviews and editing were provided by Miss. Molly Ellenberg and Dr. Arie W. Kruglanski. All authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Social and Developmental Psychology, Sapienza University of Rome (Prot. N. 1180, 27 September 2021.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant fnancial or non-fnancial interests to disclose.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the present research.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Viola, M., Kruglanski, A.W., Ellenberg, M. et al. Ambitious people are more prone to support resource-intensive aid programs. Motiv Emot 47, 1027–1039 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-023-10044-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-023-10044-z