Abstract

This paper analyses the interrelations between academic disciplines and society beyond academia by the case of sociology in Norway. For that purpose, this paper introduces the concept of disciplines’ societal territories, which refer to bounded societal spaces that are shaped by the knowledge of a discipline, premised on the linkages between the discipline and its audience. By mapping sociologists’ reported contributions to societal changes beyond academia, the paper firstly shows how societal territories are established by sociologists’ recurring engagement with certain topics and research users. Secondly, it traces the interactions between researchers and their users, and identifies four ideal typical pathways by which the cognitive territory of Norwegian sociology is transformed into societal territories. A key observation is that the establishment of societal territories is co-determined by the structures of research use among its audience. As for the case of sociology in Norway, questions therefore arise over the interdependency between sociologists as knowledge ‘suppliers’ and the ‘demand side’ for research, and the autonomy of the sociological discipline in selecting its focus of attention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite the surge of interdisciplinary research as a strategy to solve society’s grand challenges (Lyall et al. 2013; Lindvig and Hillersdal 2019), universities and other academic institutions still tend to organize their academic activities in departments along the boundaries of disciplines (Jacobs 2017; Lyall 2019). Academics’ identities are constructed and sustained in the context of the disciplines (Henkel 2005), and academic recognition is predominantly awarded within the disciplines (Abbott 2001; Lyall 2019). But disciplines have also been accused of being silos that have outlived their usefulness (e.g. Wallerstein 2003), preventing communication and suppressing innovation and the development of cohesive solutions to urgent social problems, among other things (Jacobs 2013). The structures of academic disciplines are believed to restrain “socially robust knowledge” (Gibbons et al. 1994; Klein 2015), yet academic disciplines have nevertheless retained the status as a basic feature of academia. The aim of this article is to revisit the discipline to explore the processes whereby also discipline-based research may lead to societal changes. For that purpose, this paper introduces the concept of disciplines’ societal territories, which refer to bounded societal spaces that are shaped by the knowledge of a discipline, premised on the linkages between the discipline and its audience.

Disciplines are both social and epistemological entities (Hammarfelt 2019). They make up distinct knowledge domains based on particular forms of inquiry and theoretical outlooks, but also social domains that present the members of a discipline with a shared set of cultural values and practices (Clark 1987; Heilbron 2004; Becher and Trowler 2001). This outline motivated Becher and Trowler (ibid) to portray disciplines as different tribes—each controlling their own cognitive territory, distinguished by distinct dialects and ways of seeing the world. The social and the cognitive—the tribe and the territory—is mutually constitutive, with the territory providing structures that both enable and constrain the practices of the tribe. However, disciplines are also interdependently linked with societal processes beyond academia, and science and society shape and reshape each other in dynamic processes (Jasanoff 2004). Disciplines do not only operate within the boundaries of science, they also continually interact with and influence society, providing knowledge for social action and change. The argument of this paper is that disciplines by this also occupy territories in society beyond academia, that is: the territory of a discipline can also be manifested in the form of societal territories. The outline of the societal territories of disciplines is explored in this paper by the case of sociology in Norway: What topics and audiences are Norwegian sociologists engaged with, and by what pathways is the societal territory of sociology in Norway shaped and sustained?

Whereas the cognitive territory of a discipline is established on institutionalized academic arenas such as in the curriculums of disciplinary courses or in academic journals (see e.g. Schwemmer and Wieczorek 2020), societal territories are found outside of the boundaries of academia. The term refers to where and how research is applied in society, and thus how research contributes to recognizing, defining and providing solutions to given societal issues. A key argument of this paper is, however, that these are not merely ideationally driven processes by which the knowledge of a discipline is transformed into social consequences. They should also be studied as social processes whereby researchers engage with and develop mutual social relations with particular societal audiences. Taking its cue from a specific discipline, one of the main contributions of this paper is therefore its demonstration of how particular societal territories are established in the social space between a specific discipline’s cognitive territory and its societal audience which applies the perspectives and solutions of the discipline in their undertakings. This paper thereby argues how the societal territory of a discipline is not only established through the unilateral actions of researchers but is also co-determined by the structures of research use among its audience.

As for the case of sociology, it is commonly recognized for its broad and general cognitive territory (Turner and Turner 1990; Abbott 2001). Rather than being associated with a particular methodology or study object—such as pedagogics being about teaching and learning—sociology is united by its ‘sociological imagination' (Mills 2000) or the ‘sociological eye’ (Collins 1998) which can be utilized to analyze any human interaction and social context. As a discipline, it is accordingly characterized as a low-consensus discipline marked by methodological as well as paradigmatic divides that are accompanied by a differentiation in research topics (Schwemmer and Wieczorek 2020). This all-encompassing character makes sociology a special case as its societal territory cannot be theorized a priori from the objects of its cognitive territory. With regard to the Norwegian context, sociology has, however, been known for its ‘problem-oriented empiricism’ (Mjøset 1991; Thue 2010), referring to the applied nature of early sociological research in Norway. The discipline was known as a major supplier of analyses for the functioning of the welfare state (Engelstad 1997; Burawoy 2004), and it is has been claimed that the influence of sociology in society is larger in Norway than in any other country (Allardt et al. 1995). By taking Norwegian sociology as a starting point for the empirical analysis, the study will accordingly also shed light on the current status of these previous observations and demonstrate the characteristics of sociology’s present-day societal territory.

The empirical analysis is based on 58 so-called narrative impact cases written by sociologists who, either as individuals or by representing groups of researchers, describe how their research has contributed to changes in society beyond academia by linking societal changes to specific research efforts. By analyzing the interactions between sociologists and their societal audiences as described in the impact cases, four main pathways through which Norwegian sociology has carved out a societal territory are identified. Further, the analysis suggests that while Norwegian sociology still nurtures strong relations to policymakers and practitioners in the state-centered welfare sector, sociologists are also increasingly establishing linkages to societal actors in other sectors where sociologists contribute with expertise on risk society and environmental risk management and prevention—a contribution that has not previously been discussed in relation to Norwegian sociology (see Thue 2020; Aakvaag 2019).

In the next section, the theoretical framework and its application is outlined. This is followed by a presentation of data and the analytical strategy of the study. The empirical sections present firstly the topics and main audiences that sociologists engage with, which also outlines the basis for Norwegian sociology’s societal territory. Secondly, the pathways and interactions by which the societal territory of sociology is established are analyzed. The paper ends with a discussion of the preconditions for the establishment of societal territories and the application of societal territories as a heuristic to capture disciplines’ interlinkages with society beyond academia.

The Disciplines and Their Societal Territories

The dynamics between science and society, and the question of how research is intertwined with other social processes has been dealt with by generations of scholars across a range of disciplines—from science studies, including science and technology studies, to history, political science, sociology and higher education studies. It is not possible, within the scope of an article, to comprehensively review the literature underlying the current understanding of this relation and its discords.Footnote 1 However, while sociologists of science and higher education scholars tend to focus on how disciplines advance and draw boundaries towards other disciplines within academia (e.g. Bourdieu 1975; Abbott 2001; Fridahl 2010), scholars who study science in society have on the contrary focused more on the boundaries between science and society (e.g. Gieryn 1983; Jasanoff 2004). The way disciplines as social and epistemological entities (cf. Hammarfelt 2019) interact with audiences in society have received far less scholarly attention. As a fundamental feature of academia, disciplines provide the basis of teaching and research, and they deliver structures of approval and authority to speak on scientific matters within the field of the discipline (Merton 1972; Heilbron 2004). Yet their social and cognitive practices are not delimited by the institutional boundaries of academia as science and research are intimately intertwined with extra-scientific actors and organizations (Nowotny et al. 2001).

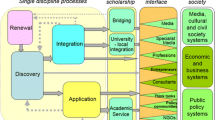

While having in mind the abundant complexities involved in the relations between science and society, and acknowledging the blurred boundaries between science and society (cf. Jasanoff 2004), the concept of societal territories draws on a two-pronged analytical approach to capture how disciplines engage with society beyond academia. Firstly, it takes into account how disciplines influence society by cognitive means; by providing (research-based) representations of certain topics, disciplines offer interpretations and classifications that may shape our understanding of society (Nowotny 1991; Jasanoff 2004). Secondly, it emphasizes that such cognitive influences rely on social relations and the mobilization of relevant audiences that acknowledge the cognitive authority of disciplines (Abbott 2005; Fourcade and Khurana 2013).

Disciplines and Their Topics

Despite the significant social processes that underline the division of labor between the modern disciplines, disciplines are fundamentally founded cognitive structures of shared sets of concepts, questions, references and methods (Heilbron 2004). This is also the basis of disciplines’ cognitive territories (cf. Becher and Trowler 2001). They provide researchers with tools to describe and analyze the world, as well as classifications and distinctions that allow us to make sense of our contexts. In this, there is also a transformative potential; when disciplines describe and analyse the world, they are similarly productive of the social world. Hence, knowledge also has an enabling capacity when we act in accordance with the ‘realities’ (cf. Law 2009) constructed by the tools of the disciplines.

Yet, disciplines do not only revolve around tools, distinctions and classifications. They also engage in certain topics that are scrutinized by the discipline. While discipline-specific tools and classifications may be context-independent, their application on certain topics provide acknowledgment and meaning to these topics. In doing this, the disciplines also contribute to certain topics becoming named, recognized and interpreted (Nowotny 1991). By extension, one can assume that the cognitive territory of a discipline is not only characterized by how they make sense of and explain the world, but also by what parts of the world disciplines make sense of. When disciplines place certain topics on the agenda, they raise societal awareness and offer interpretations of events and processes as possible solutions to problems that are addressed, thus forming the basis for collective action in relation to the topic (Béland and Cox 2011; Nowotny 1991). In line with this understanding, the topics that disciplines engage in and apply their discipline-specific tools on, are an essential link between a discipline’s cognitive territory and its societal territory.

The Social Processes of Transforming Topics into Territories

The processes whereby disciplines engage in certain topics may also be studied as social processes where disciplines gain societal influence by the mobilization of relevant audiences (Fourcade and Khurana 2013). To demonstrate this process, Fourcade and Khurana (ibid) show how the expansion of the economic discipline in the US was dependent on the growth of linkages between specific intellectual, practical and political fields which transformed the cognitive ideas of economics into societal and political influence. By making claims on their superior expertise on particular topics towards relevant audiences in policy and finance, academic economists carved out a jurisdiction in which economic expertise provided the legitimate tools and concepts to act on certain issues. One example of this is the work of academic economists as expert witnesses and consultants in the service of stakeholders and corporations, contributing to reduce the space between science and practice. Economists’ influence in the US can, however, not simply be attributed to the economists themselves. Rather, their expansion must be understood in parallel with the growth of audiences in policy and finance who valued the ideas provided by economists, choosing to apply economic expertise on certain topics and thereby supporting the further academic progress of the economic discipline (ibid).

The development of economics in the US is a typical case of what Andrew Abbott (2005) calls ‘linked ecologies’: different ecologies or fields, each controlled and coordinated by a group of actors with shared tasks and shared knowledge, are linked in a set of social relations structured by support and opposition, supply and demand. Such ecologies can enter into strategic coalitions where actors from one ecology can move between different ecologies. In these processes, the ideas and skills of one ecology are transferred to others through the creation of knowledge networks that remove previous boundaries between ecologies. A key argument of Abbott is accordingly that the growth and influence of disciplines emerges in the space between the discipline and its audience. Disciplines claim authority to provide diagnoses and solutions to certain problems and themes, and succeed when external audiences approve of the legitimacy of the discipline’s superior knowledge and ‘ownership’ of these themes. Who these audiences are will depend on the specific location of actors and the links between them, as well as their influence on the arenas where claims for influence take place.

Societal Territories: Between Topics and Audiences

A key contribution of the ecology-approach is the emphasis on the overlap and the mutual influence between disciplines and their audience. The cognitive territory of a discipline is accordingly not expected to simply be converted into societal territories by the unitary actions of the members of a discipline. Rather, the societal territory of a discipline is expected to emerge in the interlinkages between the discipline and its audience which makes demands and subsequently approves of the disciplines’ authority. Disciplines can draw attention to and offer definitions and solutions to given topics, yet the societal territory is established only when they acquire societal legitimacy and are appropriated by audiences and actors in the service of societal change. By this, the initial subject matter—the topic—of the discipline changes, and the discipline and its audience enter in a mutual relation whereby the cognitive and the societal territory is continuously constituted in reflexive processes. These processes are also social processes, in which actors are involved in repeated interactions, and in which alliances and interdependencies arise. It is therefore necessary to explore the links and interactions between the discipline and its audiences in order to understand how the societal territory of a discipline arises and takes form.

The Way Forward: Tracing the Linkages Between Disciplines, Their Topics and Their Audiences

The studies of Abbott (2005) and Fourcade and Khurana (2013) are premised on a macro-historical forward-tracing of the co-evolution of disciplines and broader social processes. In contrast, the purpose of the present study is to provide a contemporary account of the societal territory of disciplines by the case of sociology. To distinguish the linkages and the audiences that enable the societal territory of Norwegian sociology, this study follows a micro-oriented pathways approach by tracing backwards the ‘productive interactions’ (Spaapen and van Drooge 2011) between sociologists and their audiences. The approach outlines interactions—both direct and indirect—between researchers and their audiences as linkages between different systems which may transform as the interactions unfold. Such interactions may involve exchanges of information and knowledge, but also financial resources which may enable researchers to research certain topics. Hence, such interactions are not just transformational for society; they likewise have the capacity to steer the questions asked by researchers and their topics for analysis (Gläser 2019).

The unfolding of productive interactions constitute pathways which are characteristic of the interactions between researchers and their audiences (Muhonen et al. 2019). While such pathways are descriptive heuristics, they provide a means to capture the patterns of interaction between researchers and their (different) audiences: on what arenas do they meet and what is conditioning their interactions? What is the status and the position of their audiences and how do they make use of the knowledge and expertise that they access when they build social relations with sociologists? These are highly context-dependent questions, and each interaction will have their particular origin and outcome. Yet by carefully mapping and categorizing the common features of the interactions, some shared pathways and thus linkages may be outlined.

Background: Sociology in Norway

The blurred boundaries of sociology and disagreements over its core has brought about concerns about the survival of sociology internationally (Burawoy 2005; Carroll 2013). In Norway, however, sociology is one of the largest social science disciplines measured by the number of researchers employed in Norwegian universities, university colleges and research institutes. In a recent evaluation of the social sciences in Norway (Evaluation of the Social Sciences in Norway 2018), 567 researchers were enlisted as sociologists, and economic-administrative research was the only larger social science research field. However, only about half of the sociologists are based in higher education institutions. The other half is employed in so-called research institutesFootnote 2 which form a considerable part of the Norwegian research sectorFootnote 3 and have research and development as their core activity. They receive a small share of public basic funding (about 12.5%), yet their main income is from competitive assets, including funding from the Research Council of Norway and the European Research Council, as well as contract research, often commissioned by government ministries, state agencies or other public and private organizations. Hence, these institutes have a hybrid character by being committed to both academic and user-driven concerns (Gulbrandsen 2011).

As to the social science institutes, their establishment from the 1950s and onwards is commonly explained by public demands for social science research linked to the development of the Norwegian welfare state and regional knowledge needs. Many of these institutes had an interdisciplinary social science research profile, yet sociology was a main pillar in their establishment. Early pioneers received inspiration from American pragmatist sociology and laid the foundation of what is commonly referred to as the problem-oriented empiricism which characterized Norwegian sociology for many years (Thue 1997; Mjøset 1991). Sociologists focused their attention on empirical topics and developed their diagnoses of society thereafter. This orientation has provided sociology in Norway with a strong common identity, and interactions between research institutes and higher education institutions have been extensive (Harpviken and Heie 2019). A formal decoupling between the research institutes and their original clients over the last 25 years combined with increased competition for external research funding has moreover made research conditions more similar for sociologists in research institutes and higher education institutions, respectively.

Data and Methodology

The data analyzed in this study is 58 so-called narrative case studies written by sociologists for the evaluation of the social sciences in Norway, initiated by the Research Council of Norway in 2017.Footnote 4 The cases cover all institutions hosting sociological researchers and offer a unique and comprehensive material documenting the role of Norwegian sociology in society. The purpose of the cases is to demonstrate how research has made a difference in society beyond academia by linking societal changes to specific research efforts. In doing this, researchers have followed a given template where they first provide detailed descriptions of research efforts before they go on to demonstrate how research has been taken up by audiences and users and eventually contributed to specific societal changes. In doing this, the cases typically include details on the organization and funding of the research as well as the activities and interactions between researchers and different users. All cases are about the same length in total: 900 words plus references to research and external sources to support the claims made in the text, as well as statements by key stakeholders. The cases are published digitally in a joint report (The Research Council of Norway 2018a).

As the cases are written in the context of a research evaluation, they must be read as researchers’ self-representation rather than strictly neutral descriptions. This also means that they represent foremost academics’ own perspective on their societal impact. The essence of the claims is, however, in most cases corroborated by key users or stakeholders, providing the cases with a certain degree of intersubjectivity between the researchers and their audience which strengthens the credibility of the case narratives. They are information-rich and often include detailed descriptions of researchers’ interactions with different audiences as well as reflections on the nature of their contribution to possible societal changes. Compared to equivalent British case studies, the Norwegian cases have been assessed as less polished and uniform, and more nuanced in how they assess the unfolding of their research impact (Wróblewska 2019). As such, they appear as open documents, accounting for how researchers have engaged with societal actors and how their research has been taken up beyond academia in the eyes of the researchers. For the purpose of this paper, the cases are accordingly analyzed to develop empirical knowledge on what topics sociological researchers have contributed to, and how the interactions between researchers and societal actors have come about, rather than to question the scope and reach of the cases.

Representativity of the Cases

The criteria for case submission suggest that the cases offer a broad, although not complete, image of the societal contributions of Norwegian sociological research. Every institution could submit one case per 10 researchers, plus one case per research group, which meant that institutions had to select which cases to submit. This implies that there is sociological research not accounted for in the material. The evaluation context suggests, however, that cases were selected because they were considered to be representative of the institution and its linkages with society upon submission. In all, 20 institutions, 11 higher education institutions (HEIs) and 9 research institutes,Footnote 5 submitted in total 58 cases (Table 1). While several of the institutions and research institutes have an interdisciplinary profile, the researchers that are enlisted for the evaluation represent sociological ‘enclaves’ within these institutions/research institutes.Footnote 6

The larger number of cases submitted by research institutes reflect the higher number of research groups in the institutes compared to the higher education institutions. There were also a couple of research groups in the higher education institutions who chose to refrain from delivering impact cases, suggesting that they wanted to communicate a certain degree of separation from society.

Analytical Proceeding

Each of the cases were analyzed and categorized according to the topics they addressed following an inductive strategy. Cases addressing similar topics were grouped together, and eventually assembled according to the broader societal topics they addressed (cf. Table 2). This displayed three broad societal topics that the cases addressed: (a) cases concerned with social equality and inclusion, (b) environment and risk management, and (c) human rights and law enforcement. A couple of cases are categorized under the label ‘other’ as they did not fit thematically together under the previous labels.

Furthermore, each case was mapped and analyzed with the purpose of detailing the processes of interaction between researchers and other societal actors. This included a coding of main audiences and users of the research; the context and preconditions for their interactions; what kind of productive interactions (cf. Spaapen and van Drooge 2011) they engaged in as well as the timeline of events. In doing this, five main audiences stood out (cf. Table 2): international organizations; European policymakers; Norwegian policymakers; practitioners (such as social workers applying research in their practice); and private companies/NGOs. Information regarding the organization of research in universities, research institutes, research groups or single researchers (cf. Table 3) as well as funding source was also added to the analyses.

The Societal Territory of Norwegian Sociology

The societal territory of a discipline is observed when specific societal topics or social spaces in society are shaped by the knowledge of that discipline, premised on the linkages between the discipline and its audience. As for Norwegian sociology, the image of sociology as a general discipline is not only appropriate for the cognitive territory of sociology but is also found in the breadth of topics reported in the cases. As shown in Table 2, the cases address a wide array of topics, ranging from gender equality, immigrant integration and social work practices to risk regulation in the petroleum sector and climate adaption. Norwegian sociologists engage with audiences and research users both in the private and the public sector, in Norway and abroad, and in most cases, sociologists have engaged with several different audiences at once. They contribute to policymaking, to the work of practitioners and to the regulation of risk and safety.

Even though the breadth of cases in total illustrates the widespread societal contribution of sociology, the analysis of the cases nevertheless shows that sociology’s societal territory centers on issues concerning social equality and inclusion of different groups in society. The list of such topics is extensive, demonstrating sociologists’ contributions to the integration of immigrants and disabled people, work inclusion in general and other work-life related measures at the core of the Norwegian welfare state and the Nordic labor market model. Sociologists have been key providers of knowledge on issues concerning gender equality, both in the households and on the labor market, in the development of integration policies in Norway, and in the design and implementation of instruments supporting the labor force in the Norwegian social security system. In other words, the purpose of a long series of cases is about how—often vulnerable—social groups can participate in society, be it immigrants, social security beneficiaries, disabled people, drug users, older workers or for that matter women. Here, the sociologists have often provided knowledge on the social conditions of these groups, but also measures on how to improve their conditions.

One typical example of how sociologists have contributed with recognition of societal exclusion is the research done at the Institute of Social Research to document systematic ethnic discrimination in the Norwegian labor market. The results, confirming the practice of ethnic discrimination by employers, have been used extensively in policy documents as well as by other governmental organizations and professionals working to prevent discrimination, and have also had a substantial effect on the public debate on ethnic discrimination. The case is typical not only in its focus on a vulnerable social group. It is also typical by the way of the main audience it engaged; national policymakers which are responsible for labor market and integration measures accepted the conclusions and have used them to develop policies against ethnic discrimination.

But there are also cases that illustrate how the sociological ‘gaze’ is directed at topics that are not, at the outset, related to social equality and inclusion. One case, submitted by sociologists at Oslo Metropolitan University, concern the role of libraries in society. While the mandate of libraries traditionally is about archiving and the dissemination of books and documents, the sociologists developed a new understanding of libraries; as meeting places in a complex digital and multicultural society, facilitating interactions across cultural and ethnic boundaries. The concept of libraries as public meeting spaces—contributing to social inclusion—were eventually taken up by lawmakers who adopted the concept in the mission statement to the Norwegian law on public libraries approved in 2013.

A common denominator of the cases concerning social equality and inclusion is that the main audience of the research is predominantly found in the public sector. On many instances, sociological research has fed into policymaking processes and has contributed to the evaluation and development of means and measures, new laws, or the performance and organization of welfare-related public agencies. In such cases, the contributions of research are—as expected—observed not only at the policy level, but also in the performance of the practitioners, so-called street level bureaucrats who carry out and enforce the actions required by public policies (Lipsky 2010). A few cases also demonstrate the uptake of sociological research concerned with social equality and inclusion in the private sector and abroad, suggesting that this particular concern also has an audience beyond the public sector territory. One example is the contribution of sociologists to the law on gender equity in the boardrooms of private sector corporations, raising the share of women on such boards from 6% in 2002 to 40% in 2009. Nevertheless, the vast majority of the cases refer to changes taking place within the public sector either at the level of national policymaking or through interactions with practitioners, demonstrating the interlinkages between sociologists and key actors in the public sector.

A second recurring topic, yet to a much lesser degree than the above, concerns environment and risk management. Nine out of the 58 cases arise out of research on human-nature relations and discuss how society can respond and organize in the face of environmental risks. One such case is submitted by Nord University, where a professor in sociology and her team have contributed with knowledge on local communities’ adaptive capacity in the face of climate change coupled with other societal changes. The uptake of this research is seen not only in municipalities which have implemented the research in local planning documents, but also in national policymaking, following from the professor’s participation on a public commission on climate adaption as well as internationally in the assessment undertaken by Working Group 2 of the IPCC. Other cases were concerned with risk regulation in the petroleum sector, one of the largest export sectors in Norway, but with previously few recognized links to sociological research.

Sociological engagement with environment and risk management can be seen in relation to Norway as a country with large natural resources, while at the same time being committed to green ambitions and the principles of sustainable development (Lafferty et al. 2007). Seen together, however, the cases concerned with this topic do not display the stable linkages between sociologists and a specific audience, such as those concerned with social equity and inclusion. While all nine cases document that sociological research has contributed to national policymaking, they moreover document links to arenas abroad as well as in the private sector. This reflects the broad relevance of research on environment and risk management, which transcends national boundaries as well as the private-public divide seen in other topics.

The remaining cases are linked to topics concerning human rights and law enforcement. While these cases have links to the territory on social equality and inclusion, it has grown out of a particular strand of sociological research –sociology of law and criminology. Interestingly, despite law being a largely national subject, several of these cases demonstrate sociologists’ contributions to both international and European law enforcement and regulations. An example of this is the involvement of sociologists in the prevention of human trafficking at the border of Bulgaria, a gateway to the Schengen area. Based on long-term research on migration and vulnerability to human trafficking, researchers contributed with training of police officers and border guards as well as longer term capacity building.

To sum up, the cases demonstrate Norwegian sociologists’ extensive engagement with public welfare authorities by providing research and expertise to substantiate the politics and practices of the welfare state. Still, this societal territory extends beyond the boundaries of the Norwegian welfare state, and into, inter alia, the private sector and abroad, although to a much lesser extent. Additionally, the cases demonstrate an emerging territory concerning environment and risk management that transcends traditional sectoral dividing lines—thus reflecting the cross-sectoral challenge of this issue.

The Pathways Linking the Cognitive and the Societal Territory of Norwegian Sociology

The question of how sociologists have established the observed societal territories varies according to several factors, including under what conditions the research is produced and the character of the productive interactions between the researchers and their audience. Often, the cases show how researchers engage in multiple kinds of productive interactions with different audiences and research users over time. Also, research is produced over longer periods within different contexts; it can start out as a small project commissioned by a ministry and develop into a larger project with a broader academic and societal scope which engages with several kinds of research users. By distinguishing the different pathways linking the research production of the cognitive territory to the research use in the societal territory, four distinct pathways stand out from the cases (see Table 3).

-

1.

The commissioned research pathway

A considerable share of the interactions between researchers and research users is related to commissioned research. Ministries and state agencies in Norway have dedicated budgets to commission research, and they use this to procure research for policy and practice by announcing research projects with a pre-given research problem and often also guidelines for research design. Hence, the main audience of sociological research under this pathway is state agencies and ministries, but there are also examples of research that was commissioned by private companies and organizations such as the cases concerned with risk regulation in the petroleum sector. Often, the calls involve empirical mappings and evaluations of specific policy instruments or development of tools for professional practice, but there are also examples of commissioned research projects where sociologists contribute with more exploratory studies. As regards the sociologists involved in commissioned research, they are predominantly based in research institutes, reflecting differences in funding sources between research institutes and higher education institutions. While sociologists in research institutes often report participation in both commissioned research projects and projects financed by the Research Council of Norway or the European Research Council, sociologists in higher education institutions are mainly oriented towards the latter funding source.

One typical example of commissioned research pathway is a research project carried out by sociologists at the Centre for Welfare and Labour Research, commissioned by the Labour and Welfare administration with the purpose of evaluating the so-called “Comprehensive, Methodological, Principle-based Approach”. The project was an intervention-based study, and the approach under evaluation was introduced to improve professional practices for work inclusion. The results of the research contributed to an upscaling of the approach with new methods for professional practices in the welfare administration as well as more people going back to work.

The project is illustrative of the pathway in the sense that the commission process and the larger system of commissioning research in Norway was a precondition for the research taking place—the research would not have been carried out without it. It is also typical by its explicit contribution to policy and practice. Such “research for policy” suggest that the research’s societal relevance and application is largely determined even before the research is carried out.

-

2.

The project pathway

The project pathway refers to typical academic research projects extending several years with external funding from either the Research Council of Norway or the European Research Council, and where the outputs of the projects have had an uptake beyond academia. While the project pathway is similar to the commissioned research pathway in its focus on one given topic at a given time, the origin of the research and the conditions for knowledge production differs substantially, as does the nature of the interactions with different audiences. The knowledge production in the project pathway typically takes place independently of interactions with potential research users. The research has been awarded funding based on its excellence, and engagement with audiences happens rather when research is disseminated to the public or in dialogues with affected stakeholders. Hence, they follow to a larger extent the so-called linear model of societal impact where the research itself and the ‘uptake’ of the research follow in a successive sequence. The aforementioned research project on libraries as public meeting spaces, which was a four-year research project funded by the Research Council of Norway is typical for this pathway. While the researchers did not engage directly with policymakers, they argue that their research was taken up after active communication of their findings and perspectives to the field of practice.

-

3.

The expertise pathway

Whereas the former two pathways start out from the contribution of specific knowledge outputs to society, the expertise pathway is based on the societal contributions of specific individuals, either in the capacity of academic experts or as public intellectuals (cf. Kalleberg 2008). This pathway is characterized by the contributions of sociologists who have generated extensive knowledge and expertise on a given topic, and who apply this expertise to current issues affecting society. This can happen by acting as public intellectuals, where sociologists translate specialized academic knowledge to the public, often as they comment upon the public agenda. Or they act in the role of experts who offer advice to clients on the basis of their expertise. The public intellectual typically disseminates their expertise in the public sphere and thus with an unspecified audience, whereas experts more often offer their advice behind closed doors to an exclusive audience which has already recognized the relevance of applying sociological knowledge. An example of this, which is observed repeatedly, is researchers who participate as members of governmental commissions. Such commissions are established temporarily by the government with a mandate to offer advice on given issues. While they have some similarities with commissioned research, commissions should not only contribute with factual descriptions and analyses, but also with specific advice to policymakers. They are typically composed by members from different parts of society, including both researchers and societal stakeholders, and they are considered to have a profound influence on Norwegian policymaking (Tellmann 2017; Christensen and Holst 2017).

One example of such influence is presented by the aforementioned case of the professor from Nord University, who was an expert on a Norwegian governmental commission as well as in the IPCC. Another example is a professor from the University of Oslo who has chaired two commissions on integration policy that has contributed to a paradigmatic shift in the ways policies are developed in this field. While she is an expert on integration policy, her influence is based as much on her position as a chair of the commissions as on her scholarly work.

-

4.

Monopoly pathway

While the three former pathways report on ‘pure’ pathways where the productive interactions either center around one person, one project or one societal output, there are a number of narratives that report on parallel involvement in several different pathways. This can be groups of sociologists with expertise and knowledge related to a specific topic which repeatedly answer calls for commissioned research related to that topic, but also develop larger projects where they advance the knowledge base of that topic. Over time, this leads to some research institutes and research groups developing ownership of certain topics and research questions in the Norwegian context, and where they become the main provider of knowledge to society on these issues and are also invited to contribute on governmental commission and in public debates. Such monopolization of certain topics occurs through two different mechanisms; one cognitive and one social.

The cognitive monopoly pathway is established by researchers who develop a specific method or database that they have intellectual ownership to and which society depends on to enlighten and solve certain societal tasks and problems. One example is the “Reference budget for consumption”, developed over decades by the Consumption Research Norway that is now used daily not only by the government when adopting rates for income grants or need limits for support, but also by private banks when it comes to calculating how large a loan burden each individual can handle. Another example is a survey-based database called UngData which is developed by the research institute NOVA since 2010. The database is the origin of much research on youth in Norway, and findings are regularly referred to and used by national policymakers as well as by municipalities and schools; it has become virtually impossible to discuss the conditions for youth in Norway without referring to UngData.

The social monopoly-pathway is, on the other hand, established by researchers who work on a given topic over many years, and who thereby develop extensive networks with decision-makers and key stakeholders who become dependent on their particular knowledge and expertise. One example of this is sociologists at Fafo Institute for Labour and Social Research who do research on the labor market and working life with a special emphasis on the collective institutions characterizing the so-called Nordic model. While their research has become a shared point of reference for the government and labor market organizations, they have also engaged in repeated productive interactions as experts in the service of the state and trade unions since their establishment by the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions (LO) in 1982. Thus, they dominate as a contributor to questions related to the Norwegian labor market in the eyes of specific audiences.

Discussion: Establishing Societal Territories by Way of Monopolizing Topics?

The different pathways show how smaller groups of sociologists and even single sociologists have established social relations with key actors in specific areas of society who authorize their expertise and take their research into use. The outline of the discipline of sociology’s societal territories is, on the other hand, inferred from clusters of topics where sociologists—independently of their organizational affiliation—are recognized as key providers of knowledge. By looking at the different pathways and topics together, one can see the contours of how sociologists overall have established monopolizing pathways—linking their cognitive and societal territories. This applies in particular to issues concerning social equality and inclusion where sociologists jointly have grown extensive relations to the public authorities of the welfare system in Norway.

Sociology’s commitment to the welfare state is not a new observation: A recurring claim in earlier discussions on the role of sociology in Norway as well as in neighboring Scandinavian countries is sociology’s close linkages to the development of social policies and the broader welfare system (Engelstad 1997; Fridjonsdottir 1991). This has laid the foundation for societal changes that are founded on sociologists' knowledge base and way of seeing the world. But this has also changed the social reality as sociologists see it, and the processes of stable interactions between sociologists and their audience is illustrative of how the cognitive and the societal territory become mutually constitutive. The historical success of sociology as an ‘opposition science’ has contributed to the gradual transformation of sociology into a science for steering (Slagstad 2009). These processes are shown to be both cognitive and social: The way some sociologists have succeeded in gaining control over certain topics reflects Abbott’s (2005) analysis of how ecologies link up with each other to establish settlements where knowledge is shared and co-produced over time as sociologists respond to the demands of specific audiences, such as ministries and directorates who commission research. In the case of the societal territory of social inclusion and equality, this is reinforced by the fact that the welfare system in Norway is characterized by stable sector organizations with clearly defined tasks, creating a firm foundation for long-term settlements between sociologists and their research users. This has generated stable alliances between sociologists and key societal actors who regularly use and recognize the value of ‘the sociological eye’. But this has also had a possible feedback effect, where the audience has defined the topics of the discipline. While it may be argued that the sociologists and their audience have enjoyed a mutual interest and gain in their stable settlement, this has possibly also narrowed the scope for explorations and scrutiny into alternative topics.

The different pathways moreover illustrate how settlements depend upon specific societal arenas where users of research can connect with researchers, and where demands for sociological knowledge and expertise are formulated. Hence, there are certain arenas or instruments which facilitate the interlinkages and the repeated interactions between the cognitive and the societal territory of the discipline. In Norway, the budgets for commissioning of research in public administrations and the use of experts on governmental commissions stand out as such arenas. Both involve the government’s recognition of sociological expertise and operate as direct channels to policy influence and are thus critical preconditions for the establishment of sociology’s societal territories in Norway. The cases show that these channels have also been decisive in facilitating the emergence of a societal territory for sociologists, linked to environment and risk management. As a topic, this is, however, coordinated across more heterogeneous audiences compared to welfare-related topics, and time will show whether sociologists will succeed in settling this as a bounded societal territory for Norwegian sociology.

Concluding Remarks

Norwegian sociology may be a special case by way of how researchers have established close linkages with certain societal audiences. The case nevertheless demonstrates how the cognitive territory of a discipline has societal consequences by engaging with related topics and the societal actors who oversee them. But this also has potential transformative effects on the discipline. As sociological research has concentrated its empirical efforts around certain topics and its stakeholders, this has also shaped the cognitive outlook of the discipline and what sociologists see as relevant in their research. In this way, the concept of societal territories may offer a heuristic to broaden our understanding of where and how the territory of a discipline is developed and sustained. While the territories of disciplines certainly are most visible within academia, they are also shaped by the linkages they cultivate with certain societal audiences, which are often premised on financial mechanisms and structures of research use. As for the case of sociology in Norway, questions therefore arise over the interdependency between sociologists as knowledge ‘suppliers’ and the ‘demand side’ for research (Sarewitz and Pielke 2007), and the autonomy of the sociological discipline in selecting its focus of attention (Merton 1972). This is most visible in regard to Norwegian sociology’s long-term commitment to societal stakeholders from welfare authorities. Yet the analysis also showed how ‘the sociological eye’ has received acknowledgement on societal areas that are rarely discussed in the context of Norwegian sociology, showing the potential of the discipline to broaden its societal territory.

This study has provided a first step towards tracing the linkages between the members of a discipline and their audience. Further research should, however, investigate the prevalence of the cognitive territory and the degree of overlap between the cognitive and the societal territory. While this study has focused on the societal outputs, there are certainly examples of cognitive inputs from Norwegian sociology without a (direct) societal reception. However, this does not indicate that these parts of the sociological discipline are without social relevance. A further development of the heuristics of societal and cognitive territories should therefore take into account how academics also negotiate between academic and societal audiences in selecting their focus of attention (cf. Merton 1972). Moreover, this study is an investigation into the societal territory of one discipline and the relations between the discipline and its audience. Yet, as discussed by inter alia Calhoun (2017), societal problem areas are often approached by several different disciplines. This can lead to “parallel play” (ibid: 11) or even competition between disciplines (cf. Fourcade et al. 2015), but also cooperation and integration. The topics that form the societal territories of a discipline are not necessarily theirs exclusively, and more engagement across and between disciplines is commonly expected to produce more ‘socially robust knowledge’ (Gibbons et al. 1994; Klein 2015). Furthering our understanding of how societal territories are established and maintained may also increase our understanding of how to facilitate more interdisciplinary approaches to societal problems.

Data availability

The empirical data underlying the analysis are published here: https://wsww.forskningsradet.no/siteassets/publikasjoner/1254035787331.pdf.

Code availability

Not relevant.

Notes

See, however, Hammarfelt (2019) for a recent review of perspectives on disciplines.

Some of these institutes have merged with higher education institutions, but they still operate and are accounted for as research institutes.

20 per cent of the research effort in Norway takes place in the institute sector, compared to 35 per cent in the higher education sector (Solberg and Wendt 2019).

The case methodology and template were inspired by the British Research Excellence Framework (REF) yet adjusted to Norwegian conditions. The Norwegian case studies were neither graded nor linked to funding and rather labelled as a learning exercise.

The Centre for Welfare and Labour Research merged with Oslo Metropolitan University in 2015 but still operates under the terms of research institutes and is therefore labelled accordingly in this material.

For a full explanation of the enlisting, see The Research Council of Norway (2018b).

References

Aakvaag, Gunnar C. 2019. Fragmented and Critical? The Institutional Infrastructure and Intellectual Ambitions of Norwegian Sociology. In Social Philosophy of Science for the Social Sciences, ed. Jaan Valsiner, 243–267. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Abbott, Andrew. 2001. Chaos of disciplines. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Abbott, Andrew. 2005. Linked Ecologies: States and Universities as Environments for Professions. Sociological Theory 23(3): 245–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0735-2751.2005.00253.x.

Allardt, E., T. Gulbrandsen, R. Liljestrorn, N. Rogoff Ramøy, and B.A. Sørensen. 1995. Nasjonal evaluering av høyere utdanning. Fagområdet soiologi. Oslo: Kirke-utdannings-og forskningsdepartementet.

Becher, Tony, and Paul R. Trowler. 2001. Academic tribes and territories: Intellectual enquiry and the culture of disciplines, 2nd ed. Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education/Open University Press.

Béland, Daniel, and Robert Henry Cox. 2011. Ideas and politics in social science research. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1975. The specificity of the scientific field and the social conditions of the progress of reason. Social Science Information 14(6): 19–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847501400602.

Burawoy, Michael. 2004. The world needs public sociology. Sosiologisk Tidsskrift 12(3): 255–272.

Burawoy, Michael. 2005. For Public Sociology. American Sociological Review 70(1): 4–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240507000102.

Calhoun, Craig. 2017. Integrating the Social Sciences: Area Studies, Quantitative Methods, and Problem-Oriented Research. In The Oxford handbook of interdisciplinarity, eds. Robert Frodeman, Julie Thompson Klein, and Roberto C. S. Pacheco. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Carroll, William K. 2013. Discipline, Field, Nexus: Re-Visioning Sociology. Canadian Review of Sociology/revue Canadienne De Sociologi 50(1): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/cars.12000.

Christensen, Johan, and Cathrine Holst. 2017. Advisory commissions, academic expertise and democratic legitimacy: The case of Norway. Science and Public Policy 44(6): 821–833. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scx016.

Clark, Burton. 1987. The Academic Life: Small Worlds, Different Worlds. Princeton: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Collins, Randall. 1998. The Sociological Eye and Its Blinders. Contemporary Sociology 27(1): 2–7. https://doi.org/10.2307/2654697.

Engelstad, Fredrik. 1997. Norway: Sociology in a Welfare State. ISA Regional Conferences, Copenhagen.

Evaluation of the Social Sciences in Norway. 2018. The Research Council of Norway. Lysaker: The Research Council of Norway.

Fourcade, Marion, and Rakesh Khurana. 2013. From social control to financial economics: The linked ecologies of economics and business in twentieth century America. Theory and Society 42(2): 121–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11186-012-9187-3.

Fourcade, Marion, Etienne Ollion, and Yann Algan. 2015. The Superiority of Economists. The Journal of Economic Perspectives 29(1): 89–113. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.29.1.89.

Fridahl, Mathias. 2010. Understanding Boundary Work Through Discourse Theory: Inter/Disciplines and Interdisciplinarity. Science and Technology Studies 23(2): 14.

Fridjonsdottir, K. 1991. Social Science and the “Swedish Model.” In Discourses on Society, eds. P. Wagner, B. Wittrock, and R. Whitley. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Gibbons, Michael, Camille Limoges, Helga Nowotny, Simon Schwartzman, Peter Scott, and Martin Trow. 1994. The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies. London: Sage Publications.

Gieryn, Thomas F. 1983. Boundary-Work and the Demarcation of Science from Non-Science: Strains and Interests in Professional Ideologies of Scientists. American Sociological Review 48(6): 781–795. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095325.

Gläser, Jochen. 2019. How does governance change research content? Linking science policy studies to the sociology of science. In Handbook on Science and Public Policy, eds. Dagmar Simon, Stefan Kuhlmann, Julia Stamm, and Weert Canzler, 419–447. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Gulbrandsen, Magnus. 2011. Research institutes as hybrid organizations: Central challenges to their legitimacy. Policy Sciences 44(3): 215–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-011-9128-4.

Hammarfelt, Björn. 2019. Discipline.

Harpviken, Kristian Berg, and Magnus Heie. 2019. NA Reports: Norwegian Sociological Association(NSA). 02.10.2021. https://www.europeansociologist.org/na-reports-norwegian-sociological-association-nsa.

Heilbron, Johan. 2004. A Regime of Disciplines: Towards a Historical Sociology of Disciplinary Knowledge. In The Dialogical Turn, eds. Charles Camic and Hans Joas, 23–42. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc.

Henkel, Mary. 2005. Academic Identity and Autonomy in a Changing Policy Environment. Higher Education 49(1/2): 155–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-2919-1.

Jacobs, Jerry A. 2013. In defense of disciplines: Interdisciplinarity and specialization in the research university. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jacobs, Jerry A. 2017. The Need for Disciplines in the Modern Research University. Oxford University Press.

Jasanoff, Sheila. 2004. States of knowledge: The co-production of science and social order. International Library of Sociology. London: Routledge.

Kalleberg, Ragnvald. 2008. Sociologists as public intellectuals during three centuries in the Norwegian project of enlightenment, 17–48. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Klein, Julie Thompson. 2015. Reprint of “Discourses of transdisciplinarity: Looking back to the future.” Futures 65: 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2015.01.003.

Lafferty, W.M., Jørgen Knudsen, and Olav Mosvold Larsen. 2007. Pursuing sustainable development in Norway: The challenge of living up to Brundtland at home. European Environment 17(3): 177–188. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.451.

Law, John. 2009. Seeing Like a Survey. Cultural Sociology 3(2): 239–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975509105533.

Lindvig, Katrine, and Line Hillersdal. 2019. Strategically Unclear? Organising Interdisciplinarity in an Excellence Programme of Interdisciplinary Research in Denmark. Minerva 57(1): 23–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-018-9361-5.

Lipsky, Michael. 2010. Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. 30th Anniversary Expanded. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Lyall, Catherine. 2019. Being an Interdisciplinary Academic: How Institutions Shape University Careers. Cham: Springer International Publishing, Palgrave Pivot.

Lyall, Catherine, Ann Bruce, Wendy Marsden, and Laura Meagher. 2013. The role of funding agencies in creating interdisciplinary knowledge. Science and Public Policy 40(1): 62–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scs121.

Merton, Robert K. 1972. Insiders and Outsiders: A Chapter in the Sociology of Knowledge. American Journal of Sociology 78(1): 9–47. https://doi.org/10.1086/225294.

Mills, C. Wright. 2000. The sociological imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mjøset, Lars. 1991. Kontroverser i norsk sosiologi. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Muhonen, Reetta, Paul Benneworth, and Julia Olmos-Peñuela. 2019. From productive interactions to impact pathways: Understanding the key dimensions in developing SSH research societal impact. Research Evaluation. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvz003.

Norway, The Research Council of. 2018a. Evaluation of the Social Sciences in Norway. Impact Cases. Lysaker: The Research Council of Norway.

Norway, The Research Council of. 2018b. Evaluation of the Social Sciences in Norway. Report from the Principal Evaluation Committee. Lysaker: The Research Council of Norway.

Nowotny, Helga. 1991. Knowledge for certainty: Poverty, welfare institutions and the institutionalization of social science. In Discourses on Society, eds. Peter Wagner, Björn Wittrock, and Richard Whitley. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Nowotny, Helga, Peter Scott, and Michael Gibbons. 2001. Re-Thinking Science: Knowledge and the Public in an Age of Uncertainty. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Sarewitz, Daniel, and Roger A. Pielke. 2007. The neglected heart of science policy: Reconciling supply of and demand for science. Environmental Science & Policy 10(1): 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2006.10.001.

Schwemmer, Carsten, and Oliver Wieczorek. 2020. The Methodological Divide of Sociology: Evidence from Two Decades of Journal Publications. Sociology (Oxford) 54(1): 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038519853146.

Slagstad, Rune. 2009. Styringsvitenskap - ånden som går. Nytt Norsk Tidsskrift 26(3–04): 411–429.

Solberg, Espen, and Kaja Wendt. 2019. Det norske forsknings- og innovasjonssystemet – statistikk og indikatorer : Overblikk og hovedtrender 2019. Norges forskningsråd.

Spaapen, Jack, and Leonie van Drooge. 2011. Introducing ‘productive interactions’ in social impact assessment. Research Evaluation 20(3): 211–218. https://doi.org/10.3152/095820211X12941371876742.

Tellmann, Silje Maria. 2017. Bounded deliberation in public committees: The case of experts. Critical Policy Studies 11(3): 311–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2015.1111155.

Thue, Fredrik W. 1997. Empirisme og demokrati : norsk samfunnsforskning som etterkrigsprosjekt. Det Blå bibliotek. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Thue, Fredrik W. 2010. Empiricism, Pragmatism, Behaviorism: Arne NÆss and the Growth of American-styled Social Research in Norway after World War II. In The Vienna Circle in the Nordic Countries, eds. Juha Manninen and Friedrich Stadler, 220–229. Dordrecht: Springer.

Thue, Fredrik W. 2020. TfS 60 år: Den lange kjølen i norsk samfunnsforskning. Tidsskrift for Samfunnsforskning 61(1): 12–29. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1504-291X-2020-01-02.

Turner, Stephen P., and Jonathan H. Turner. 1990. The impossible science: An institutional analysis of American sociology, Sage Library of Social Research, vol. 181. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 2003. Anthropology, Sociology, and Other Dubious Disciplines. Current Anthropology 44(4): 453–465. https://doi.org/10.1086/375868.

Wróblewska, Marta Natalia. 2019. Impact evaluation in Norway and in the UK. University of Twente (Twente). https://ris.utwente.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/102033214/ENRESSH_01_2019.pdf.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Marte Mangset, Espen D. H. Olsen, Maria Karaulova, Reetta Muhonen and colleagues in the OSIRIS-center, TIK’s innovation group and the VTK-group at TIK for valuable comments on earlier drafts of the manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Oslo (incl Oslo University Hospital). The research is carried out within the OSIRIS project, funded by the Research Council of Norway’s Grant Number 256240.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that she has no conflict of interests.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tellmann, S.M. The Societal Territory of Academic Disciplines: How Disciplines Matter to Society. Minerva 60, 159–179 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-022-09460-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11024-022-09460-1