Abstract

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is associated with alterations in coronary vascular smooth muscle and endothelial function. The current study examined the contractile response of the isolated coronary arterioles to serotonin in pigs with and without MetS and investigated the signaling pathways responsible for serotonin-induced vasomotor tone. The MetS pigs (8-weeks old) were fed with a hyper-caloric, fat/cholesterol diet and the control animals (lean) were fed with a regular diet for 12 weeks (n = 6/group). The coronary arterioles (90–180 μm in diameter) were dissected from the harvested pig myocardial tissues and the in vitro coronary arteriolar response to serotonin was measured in the presence of pharmacological inhibitors. The protein expressions of phospholipase A2 (PLA2), TXA2 synthase, and the thromboxane-prostanoid (TP) receptor in the pigs’ left ventricular tissue samples were measured using Western blotting. Serotonin (10−9–10−5 M) induced dose-dependent contractions of coronary-resistant arterioles in both non-MetS control (lean) and MetS pigs. This effect was more pronounced in the MetS vessels compared with those of non-MetS controls (lean, P < 0.05]. Serotonin-induced contraction of the MetS vessels was significantly inhibited in the presence of the selective PLA2 inhibitor quinacrine (10−6 M), the COX inhibitor indomethacin (10−5 M), and the TP receptor antagonist SQ29548 (10−6 M), respectively (P < 0.05). MetS exhibited significant increases in tissue levels of TXA2 synthase and TP receptors (P < 0.05 vs. lean), respectively. MetS is associated with increased contractile response of porcine coronary arterioles to serotonin, which is in part via upregulation/activation of PLA2, COX, and subsequent TXA2, suggesting that alteration of vasomotor function may occur at an early stage of MetS and juvenile obesity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Approximately 50 million Americans are affected by metabolic syndrome (MetS), which is described by a cluster of metabolic abnormalities including hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypertension. These patients experience a significantly higher risk for coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes [1,2,3,4]. MetS is associated with alterations in endothelial function, vasomotor control, and the dysregulation of coronary blood flow, which in turn could underlie increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in these patients [5,6,7,8,9,10,11]. Notably, these changes occur prior to overt atherosclerotic disease, and have been associated with left ventricular dysfunction in human and animal models of MetS [9,10,11,12].

Vascular diseases are the principal contributors to the increased morbidity and mortality associated with MetS [13, 14]. Endothelial dysfunction is considered to be a major risk factor of cardiovascular complications in patients with MetS and specifically contributes to the exacerbation of vasospasm, myocardial dysfunction, and low cardiac output syndrome. Given that MetS affects as much as 27% of the population of the United States and is increasing dramatically in prevalence, this remains a considerable clinical problem.

The mechanism behind the alteration in the MetS induced microvascular dysfunction is incompletely understood, but may involve the dysregulation of chemical and electrical signaling in the coronary microcirculation. The endothelium controls the tone of the underlying vascular smooth muscle through the release of various vasoactive substances, including nitric oxide (NO), prostacyclin (PGI2), thromboxane A2 (TXA2), serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT), and endothelium-dependent hyperpolarizing factors (EDHF) [9, 10, 15, 16].

Serotonin is a vasoactive amine responsible for alterations in vessel contractile response in numerous organs. Previous studies by Metais and colleagues have shown that serotonin is responsible for mediating the increased coronary contraction associated with myocardial dysfunction after cardioplegic ischemia and cardiopulmonary bypass (CP/CPB), as well as with the change from serotonin-induced coronary vasodilation before CP/CPB [15, 16]. A possible cause for this may be the activation of phospholipase A2 (PLA2) by serotonin [16].

It has previously been shown that serotonin activates PLA2, which leads to the release of inflammatory mediators in the human heart [15,16,17]. This occurs via serotonin’s release of arachidonic acid, which then reacts with cyclooxygenase (COX) to form the vasoconstrictive agent TXA2, which likely contributes to the subsequent vasoconstriction seen following CP/CPB and cardiac surgery [15,16,17]. Therefore, we hypothesized that early stage of MetS may cause significant increase in the coronary arteriolar response to serotonin and the overexpression/activation of PLA2 and TXA2 may contribute to altered coronary microvascular reactivity. Thus, this study examined the contractile response of the isolated coronary arterioles to serotonin in pigs with or without MetS and investigated the signaling pathways responsible for serotonin-induced vasomotor tone.

Methods

Pig model of metabolic syndrome

Twelve Yorkshire swine (8-week old) arrived at our facility and after a week of acclimation, were separated into two groups: the normal (lean) diet group (n = 6) and the high-fat diet group (n = 6). The non-MetS control group (lean) received 500 g/day of regular chow for 12 weeks. The high-cholesterol animals received 500 g/day of high-cholesterol chow consisting of 4% cholesterol, 17.2% coconut oil, 2.3% corn oil, 1.5% sodium cholate, and 75% regular chow (Sinclair Research, Columbia, MO) for 12 weeks. The high-fat diet used in our animal model administered for 12 weeks has been shown to induce obesity, hyperlipidemia, high blood pressure, insulin resistance, and glucose intolerance, all of which are components of MetS [18,19,20,21]. After 12 weeks, the pigs were then euthanized by exsanguination following removal of the heart while under deep isoflurane anesthesia. The harvested myocardial tissues and segments of the coronary arteries in the LAD were placed in cold (4 °C) Kreb solution for vascular physiological study.

All experiments were approved by the Rhode Island Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals were cared for in compliance with the “Principles of Laboratory Animal Care” formulated by the National Society for Medical Research and the “Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (NIH publication number 5377-3, 1996).

Microvessel reactivity

Coronary arterioles (90- to 180-μm internal diameters) of the left anterior descending (LAD) territory were dissected from the harvested left ventricular (LV) tissue samples. Microvessel studies were performed by in vitro organ bath video-microscopy as described previously [15, 16]. After a 60-min stabilization period, the microvessels were constricted with serotonin (10−9–10−5 M) in the absence or presence of the selective PLA2 inhibitor quinacrine (10−6 M) or the COX inhibitor indomethacin (10−5 M) or the selective thromboxane-prostanoid (TP) receptor antagonist SQ29548 (10−6 M). Some of the microvessels were constricted with TXA-2 analog U46619 (10−9–10−6 M). One or three interventions were performed on each vessel. The order of drug administration was random.

Immunoblot

The methods for pig-LV tissue protein purification, Western blotting, and imaging quantification have been described previously [15]. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA2), TXA2 synthase, and TP receptors (abcam, Cambridge, UK). After washing with TBST, membranes were incubated with the appropriate secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase. All membranes were also incubated with GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate) or alpha-tubulin (Cell Signaling) for loading controls.

Measurement of PLA2 activity

Left ventricular heart tissue (100 mg) was dissected and washed with PBS containing 0.16 mg/ml heparin to remove any red blood cells and clots. Tissue was homogenized in 1 ml of cold buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, containing 1 mM EDTA). After centrifuge at 10,000×g for 15 min at 4 °C, the 10 μl supernatant was used for assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Chemicals

Serotonin, U46619, quinacrine, indomethacin, and SQ29548 were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and dissolved on the day of the study.

Data analysis

Data are presented as the mean and standard deviation (SD) of the mean. Microvessel responses are expressed as percent relaxation of the pre-constricted diameter. Microvascular reactivity was analyzed using 2-way repeated-measures ANOVA with a post hoc Bonferroni test. (GraphPad Software, Inc, San Diego, CA). A growth model was used to test the degree to which treatment groups and MetS affected the degree to which 5-HT-induced vasoconstriction, P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Pig model of MetS

Phenotypic characteristics of lean and MetS pigs are shown in Table 1. Compared to their counterparts, pigs with MetS exhibited significant increases in body weight, total cholesterol, HDL, LDL/VLDL, triglyceride, blood insulin, and blood glucose.

Increased coronary arteriolar constriction to serotonin and U46619 in the MetS pig

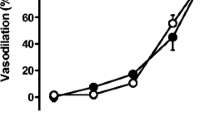

Both serotonin (10−9–10−5 M) and U46619 (10−9–10−6 M) induced dose-dependent contractions of coronary-resistant arterioles in both control (lean) pigs and in pigs with MetS. These effects were more pronounced in the MetS vessels as compared with those of the control group (lean), with a 60% increase of contraction to serotonin (10−5 M, Fig. 1a, P = 0.01 vs. lean) and an 86% increase to U46619 (10−7 M, Fig. 1b, P = 0.001 vs. lean) in MetS vessels compared to the 45% contraction to serotonin and 65% to U46619 in the control (lean) vessels, respectively.

Dose-dependent contractile response of coronary-resistant arterioles to serotonin (10−9–10−5 M) and U46619 (10−9–10−6 M) in control (lean) pigs and pigs with MetS, respectively; a Coronary arteriolar contractile response to serotonin (10−9–10−5 M) in the non-MetS control (lean) vessels and in MetS vessels,*P < 0.05 versus lean; b Contractile response to U46619 (10−9–10−6 M) in the lean and MetS vessels. *P < 0.05 versus lean

The blockade of PLA2, COX, and TXA2 on serotonin-induced contraction

Pretreatment of the MetS and control (lean) vessels with selective PLA2, COX, and TXA2 inhibitors significantly diminished serotonin-induced coronary arteriolar contraction (Figs. 2, 3, 4). Specifically, administration of the selective PLA2 inhibitor quinacrine (10−6 M) significantly inhibited serotonin-induced contraction in both the MetS and non-MetS control vessels (P = 0.002 vs. serotonin alone of non-MetS control, P = 0.004 vs. serotonin alone of MetS, Fig. 2). Inclusion of the COX inhibitor indomethacin (10−5 M) also significantly reduced serotonin-induced contraction in both the MetS and non-MetS control vessels (P = 0.001 vs. serotonin alone of non-MetS control, P = 0.003 vs. serotonin alone of MetS, Fig. 3). Furthermore, pretreatment of the vessels with the selective thromboxane-prostanoid (TP) receptor antagonist SQ29548 also significantly inhibited serotonin-induced contraction (P = 0.001 vs. serotonin alone of non-MetS control, P = 0.002 vs. serotonin alone of MetS, Fig. 4). Finally, there were significant differences in the vasoconstrictive responses to serotonin compared to the relative degree of change induced by the selective COX, PLA2, and TP receptor inhibitors between control (lean) and MetS groups, respectively (P < 0.05 vs. Lean alone, Figs. 2, 3, 4).

Administration of the PLA2 inhibitor quinacrine (10−6 M) significantly inhibited serotonin (5-HT)-induced contraction in both the non-MetS control (lean, a) and MetS vessels [*P < 0.05 vs. 5-HT alone of non-MetS control (lean, a) or vs. 5-HT alone of MetS (b)]; #P < 0.05 versus non-MetS control (lean)

Protein expression of PLA2, TXA2 synthase, and TP receptors in the pig myocardium

There were no significant differences in the tissue levels of PLA2, between the control lean and MetS groups (Fig. 5). However, MetS exhibited significant increases in tissue levels of TXA2 synthase and TP receptors (P < 0.05 vs. lean, Fig. 5), respectively.

a Representative immunoblots of pig left ventricular tissues. Lanes 1–8 loaded with 40 µg protein were developed for PLA2, TXA2 synthase, and TP receptors; b Immunoblot band intensity and analysis; c Bar graph showing cytosolic PLA2 (cPLA-2) activity of the pig myocardium in the 2 groups; n = 4–6/group; mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 versus lean

PLA2 activity

MetS significantly increased the PLA2 activity in the LV myocardium compared with normal diet control group (lean) (P < 0.05, Fig. 5c).

Discussion

There are a number of novel findings in the current study. First, early stage of MetS caused an increased contractile response of coronary arterioles to serotonin in the juvenile pig. Second, the enhanced responses to serotonin were significantly prevented in the presence of PLA2, COX, and TXA2 inhibitors. Finally, MetS induced activation of PLA2, and protein overexpression of TXA2 synthase/TXA2 receptors of heart tissue in the juvenile pigs.

MetS impairs endothelium-dependent relaxations to several platelet-derived substances in coronary microvasculature [10, 12]. MetS also markedly alters the response of coronary microcirculation to serotonin and TXA2 in a monkey model [12]. In most blood vessels, if the smooth muscle cells are exposed to serotonin, vasoconstriction occurs following activation of 5-HT receptors [15, 16]. We have recently found that the coronary arteriolar contractile response to serotonin was further altered after chronic myocardial ischemia in pigs with MetS [21, 22, 24, 25].

In the current study, we further observed that MetS without myocardial ischemia significantly increased constriction of coronary arterioles to serotonin and the TXA2 analog U46619 in the juvenile pig. This finding indicates that early-stage MetS may cause coronary arteriolar spasm, resulting in downregulation of myocardial perfusion.

The mechanisms responsible for serotonin-induced coronary constriction have been studied by our group and other investigators [12, 15, 16, 21,22,23, 27]. We have previously found that myocardial ischemia/reperfusion causes PLA2 expression/activation, which contributes to serotonin-induced coronary vasoconstriction in patients after CP/CPB and cardiac surgery [15, 16]. In the present study, we found that serotonin-induced coronary arteriolar constriction was prevented by the selective PLA2 inhibitor quinacrine, suggesting that activation of PLA2 contributes to serotonin-induced vasoconstriction in the setting of early MetS.

High-fat diet alters lipid profiles, which may lead to a pro-inflammatory state of the vascular wall and increases the risk of coronary heart disease. Changes in the arachidonic acid (AA) metabolism via COX may affect coronary function in MetS and obesity in a rodent model [23]. We have found that COX inhibition in pigs with chronic myocardial ischemia and hypercholesterolemia improves coronary microvascular function without effects on collateral-dependent territory [21, 22]. We and others have also demonstrated that diabetes and cardioplegic ischemia upregulate COX expression in the human myocardium and coronary microvasculature, which contributes to regulation of coronary microcirculation [15, 16, 22, 24, 25]. The current study further demonstrates that serotonin-induced vasoconstriction was enhanced in the MetS microvessels and inhibited in the presence of the COX inhibitor indomethacin in the non-ischemic heart tissue/vessels, suggesting that MetS regulation of serotonin induced constriction via activation of COX in the juvenile pigs.

Arachidonic acid is mainly metabolized to vasoconstrictor prostanoids, including TXA2 via COX in coronary arterioles from animals and humans [15, 16, 22,23,24,25]. We and others have previously reported that diabetic and ischemic upregulation of TXA2 contributes to modification of coronary arteriolar vasodilation and vasoconstriction in humans [15, 16, 22,23,24,25]. A high-fat diet impairs tissue perfusion in ischemic myocardium of naproxen-treated swine by shifting the prostanoid balance to favor production of TXA2 over PGI2 [22, 24, 25]. Furthermore, in the present study, we observed that the selective TP receptor inhibitor markedly diminished the coronary arteriolar contraction to serotonin in the pig model of MetS alone in the absence of chronic myocardial ischemia and drug pretreatment. In support of our physiological study, we also observed that early-stage MetS is associated with increased PLA2 activity protein expression of TXA2 synthase and TP receptors in the pig heart tissues.

Impaired microvascular insulin signaling may develop before overt indices of microvascular endothelial dysfunction and represent an early pathological feature of adolescent obesity [26]. Microvascular insulin resistance and endothelial dysfunction in skeletal muscle, brain, and heart occur early in the development of juvenile obesity in pigs [26, 27]. In the current study, we further observed the enhanced vasomotor tone of the coronary microcirculation in 5-month-old juvenile pigs with MetS. These novel findings suggest that coronary microvascular dysfunction is therefore an early manifestation of obesity/MetS and might contribute to the increased cardiovascular risk and can partially explain the reduced coronary flow reserve and increased minimal vascular resistance in patients with MetS. Thus, the present study paves the way for finding new strategies to improve prevention of complications of early pediatric obesity [28, 29].

In conclusion, these results indicate that MetS is associated with the increased contractile response of porcine coronary arterioles to serotonin, which is in part via upregulation/activation of PLA2, COX and subsequent TXA2. These novel findings suggest that the alteration of coronary arteriolar vasomotor function may occur during early stages of metabolic syndrome and juvenile obesity.

References

Galassi A, Reynolds K, He J (2006) Metabolic syndrome and risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Med 119(10):812–819

Grundy SM (2008) Metabolic syndrome pandemic. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28(4):629–636

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM (2006) Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999–2004. JAMA 295(13):1549–1555

Mottillo S, Filion KB, Genest J, Joseph L, Pilote L, Poirier P, Rinfret S, Schiffrin EL, Eisenberg MJ (2010) The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 56(14):1113–1132

Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, Donato KA, Eckel RH, Franklin BA, Gordon DJ, Krauss RM, Savage PJ, Smith SC Jr, Spertus JA, Costa F (2006) Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: an American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute scientific statement. Curr Opin Cardiol 21(1):1–6

Lakka HM, Laaksonen DE, Lakka TA, Niskanen LK, Kumpusalo E, Tuomilehto J, Salonen JT (2002) The metabolic syndrome and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in middle-aged men. JAMA 288(21):2709–2716

Tune JD, Gorman MW, Feigl EO (2004) Matching coronary blood flow to myocardial oxygen consumption. J Appl Physiol (1985) 97(1):404–415

Bassenge E, Heusch G (1990) Endothelial and neuro-humoral control of coronary blood flow in health and disease. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 116:77–165

Berwick ZC, Dick GM, Tune JD (2012) Heart of the matter: coronary dysfunction in metabolic syndrome. J Mol Cell Cardiol 52(4):848–856

Campia U, Tesauro M, Cardillo C (2012) Human obesity and endothelium-dependent responsiveness. Br J Pharmacol 165(3):561–573

Wheatcroft SB, Williams IL, Shah AM, Kearney MT (2003) Pathophysiological implications of insulin resistance on vascular endothelial function. Diabet Med 20(4):255–268

Quillen JE, Sellke FW, Armstrong ML, Harrison DG (1991) Long-term cholesterol feeding alters the reactivity of primate coronary microvessels to platelet products. Arterioscler Thromb 11(3):639–644

Haffner SM, Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, Pyorala K, Laakso M (1998) Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 339(4):229–234

Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Parise H, Sullivan L, Meigs JB (2005) Metabolic syndrome as a precursor of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation 112(20):3066–3072

Robich MP, Araujo EG, Feng J, Osipov R, Clements RT, Bianchi C, Sellke FW (2009) Altered coronary microvascular serotonin receptor expression after coronary artery bypass grafting with cardiopulmonary bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 139(4):1033–1040

Metais C, Li J, Simons M, Sellke FW (1999) Serotonin-induced coronary contraction increases after blood cardioplegia-reperfusion: role of COX-2 expression. Circulation 100:II328–II334

Berg KA, Clarke WP (2001) Regulation of 5-HT(1A) and 5-HT(1B) receptor systems by phospholipid signaling cascades. Brain Res Bull 56:471–477

Elmadhun NY, Sabe AA, Robich MP, Chu LM, Lassaletta AD, Sellke FW (2013) The pig as a valuable model for testing the effect of resveratrol to prevent cardiovascular disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1290:130–135

Potz BA, Sabe AA, Elmadhun NY, Feng J, Liu Y, Mitchell H, Quesenberry P, Abid MR, Sellke FW (2015) Calpain inhibition decreases myocardial apoptosis in a swine model of chronic myocardial ischemia. Surgery 158:445–452

Sabe AA, Potz BA, Elmadhun NY, Liu Y, Feng J, Abid MR, Abbott JD, Senger DR, Sellke FW (2016) Calpain inhibition improves collateral-dependent perfusion in a hypercholesterolemic swine model of chronic myocardial ischemia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 151:245–252

Robich MP, Osipov R, Chu L, Feng J, Burgess T, Oyamada S, Clements RT, Laham R, Sellke FW (2010) Temporal and spatial changes in collateral formation and function during chronic myocardial ischemia. J Am Coll Surg 211:470–480

Robich MP, Chu LM, Burgess TA, Feng J, Bianchi C, Sellke FW (2011) Effects of selective cyclooxygenase-2 and nonselective cyclooxygenase inhibition on myocardial function and perfusion. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 57:122–130

Sánchez A, Contreras C, Martínez P, Villalba N, Benedito S, García-Sacristán A, Salaíces M, Hernández M, Prieto D (2010) Enhanced cyclooxygenase 2-mediated vasorelaxation in coronary arteries from insulin-resistant obese Zucker rats. Atherosclerosis 213(2):392–399

Chu LM, Robich MP, Lassaletta AD, Feng J, Xu SH, Heinl RE, Liu Y, Sellke E, Sellke FW (2011) High-fat diet alters prostanoid balance and perfusion in ischemic myocardial of naproxen treated swine. Surgery 150:490–496

Chu LM, Robich MP, Bianchi C, Feng J, Liu YH, Xu SH, Burgess T, Sellke FW (2012) Effects of cyclooxygenase inhibition on cardiovascular function in a hypercholesterolemic swine model of chronic ischemia. Am J Physiol 302:H479–488

Olver TD, Grunewald ZI, Jurrissen TJ, MacPherson REK, LeBlanc PJ, Schnurbusch TR, Czajkowski AM, Laughlin MH, Rector RS, Bender SB, Walters EM, Emter CA, Padilla J (2018) Microvascular insulin resistance in skeletal muscle and brain occurs early in the development of juvenile obesity in pigs. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 314(2):R252–R264

Galili O, Versari D, Sattler KJ, Olson ML, Mannheim D, McConnell JP, Chade AR, Lerman LO, Lerman A (2007) Early experimental obesity is associated with coronary endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292(2):H904–911

Graf C, Ferrari N (2016) Metabolic syndrome in children and adolescents. Visc Med 32:357–362

Sorop O, Olver TD, van de Wouw J, Heinonen I, van Duin RW, Duncker DJ, Merkus D (2017) The microcirculation: a key player in obesity-associated cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res 113(9):1035–1045

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the staff of the Animal Facility Laboratory for their support and animal handling.

Funding

This research project was supported by AHA-Grant-in-Aid-15GRNT25710105 (J. F.), and supported in part by the NIH1R01HL127072-01A1, 1R01 HL136347-01, and NIGMS/NIH Grant (pilot project) 1P20GM103652 (J.F.) R01-HL-46716, RO1HL128831, and U54GM115677 (F.W.S), and the NIH 5T32GM065085-13 Grant (L.A.S).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lawandy, I., Liu, Y., Shi, G. et al. Increased coronary arteriolar contraction to serotonin in juvenile pigs with metabolic syndrome. Mol Cell Biochem 461, 57–64 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-019-03589-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-019-03589-6