Abstract

During the past decades, migration policies in Western societies have grown stricter by the day. As part of this retrenchment, migrants are required to pass language tests to gain access to human and democratic rights such as residency, family reunification, and citizenship, as well as to enter the labour market or higher education. The use of language tests to control migration and integration is not value neutral. The question discussed in this paper is whether those who develop language tests should strive to remain neutral, or, on the contrary, whether they have a moral and professional responsibility to take action when their tests are misused. In this paper, a case is made for the latter: arguing along the lines of critical language testing, we encourage professional language testers to take on a more active role in order to prevent harmful consequences of their tests. The paper introduces the concept language test activism (LTA) to underscore the importance of scholars taking a more active role for social justice, following the pathway of proponents of intellectual activism in related fields like sociology and linguistics. We argue that language testers have a special responsibility for justice and consequences, as these are integrated in the very concept of validity upon which modern language testing is based. A model of language test activism is presented and illustrated by real-life examples of language test activism in Norway and Italy showing that language test activism may need to take on different forms to be successful, depending on the context in which it takes place.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

During the past decades, migration and integration policy in the Western world has grown stricter by the day (Bruzos et al., 2018; Khan & McNamara, 2017). What would have struck us as inhuman, unjust and undemocratic just a few years back, has now become mainstream policy (Simpson & Whiteside, 2015). As part of this trend, language tests are not only used for admission to education and jobs, but also as gatekeepers to citizenship, residency, and family reunification (Rocca et al., 2020; Strik et al., 2010; Van Avermaet & Pulinx, 2014). The actual language proficiency levels required in these contexts, however, vary considerably from country to country, indicating that rather than representing real language needs to perform certain tasks, these demands reflect the relative harshness of the migration policy in the receiving country (Böcker & Strik, 2011; McNamara & Shohamy, 2008:92).Footnote 1 In many European countries today, learning the majority language and passing a language test is interpreted as a symbol of a migrant’s willingness to adapt to the values of the host country, as a “lever” for integration (Van Avermaet & Pulinx, 2014) or as a shibboleth (McNamara, 2005) – in short, as a mechanism for exclusion and control (Extra & Spotti, 2009; McNamara & Shohamy, 2008).

As a result, the professional field of language testing (LT) is, perhaps more than any other area of applied linguistics, intrinsically linked to politics, social context, values and ethics (Hamp-Lyons, 1997:323). Already 30–40 years ago, language testers began to acknowledge the inherently political nature of language tests as well as the potentially harmful consequences of tests on individuals and society (Hamp-Lyons, 1997; Shohamy, 2001). These early works on test ethics marked a radical shift in the orientation of language testers from a focus on test-internal qualities to a recognition of the importance of including a concern for how tests are used in society and the impact they have on those affected by them. This reorientation in the field found its theoretical underpinning in Samuel Messick’s definition of validity (test quality), away from a restricted focus on whether a test measures what it is supposed to measure, to a wider conception including test use and consequences (McNamara, 2006; Messick, 1989). Recent publications, conference presentation and professional debates in the LT field demonstrate a professional recognition of the fact that language tests are political tools, and that LT can never be value neutral. A related question, then, is whether language testers themselves should strive to remain value-neutral or whether on the contrary they should engage more actively to prevent test misuse and harmful consequences of the tests they develop.

The aim of this paper is twofold: First and foremost, we wish to encourage language testers to take a more active role in preventing language test misuse, e.g. a use of a test beyond its intended purpose, or a use that has harmful consequences for those affected by them (Carlsen & Rocca, 2021). To achieve this first aim, we will argue that adopting a more active role is a logical consequence of taking Messick’s definition of validity seriously. Building on the radical thinking of critical language testers like Shohamy (1998, 2001) and McNamara (2006, 2009), and arguing along the lines of Intellectual Activism (Contu, 2018, 2020; Hill Collins, 2013a, Contu, 2018, 2020), the paper introduces the term language test activism (LTA). A model of LTA is introduced and illustrated with real-life examples from two European countries, Norway and Italy, stressing the fact that different contexts may require different kinds of action in order to lead to political and social change.

We use the terms activism and activist deliberately in this paper where others might prefer the terms advocacy and advocate (e.g. the title of this special issue). This is done to emphasize how important it is that language testers and researchers not only ask critical questions about whether or not the use of a test has harmful consequences, which one might call an act of advocacy, but take an active role to try to prevent such consequences and to speak out when injustice is detected. Moreover, the terms activism and activist are used to underline that such actions are not risk-free. Working actively to prevent social injustice or to stop a policy that requires language tests to be used in unethical ways, comes at a cost. What is at stake comes more clearly across when the term activism is used over the more neutral term advocacy, in our opinion. Indeed, activism is often associated with energetic, visible and noisy actions, typically represented by protest marches or other group demonstrations. Our definition of activism is wider, though, building on scholars like Martin, Hanson & Fontaine (2007) and Jenkins (2017), who include in the concept activities that “take place beyond emblematic and high profile protests and away from the media spotlight” (Jenkins, 2017:1445). Hence activism, in our view, encompasses a range of different activities, from protests and demonstrations to everyday resistance and commitments to social justice.

Language Test Activism, as understood in this paper, builds on the concept of intellectual activism (Collins, 2013a; Contu, 2018, 2020) and is related to activism in other fields within the social sciences and humanities (SSH), such as public sociology (Buroway, 2005) and language activism (Florey, Penfield & Tucker, 2009; Combs & Penfield, 2012). LTA fits into a general trend in SSH the past decades, where researchers are starting to take on a more active, participatory role.

Researchers as neutral observers or active participants?

A critical question for researchers in the fields of social sciences and humanities, particularly for those working in politicized and highly value-embedded research fields like migration, social justice, equality, racism, welfare, etc., is whether objectivity and value-neutrality should be an ideal for teaching, research and research communication, or whether, on the other hand, scholars ought to see it as their responsibility to use their voices as experts to fight oppression, inequality and injustice.Footnote 2 The public role and responsibility of researchers within SSH is still vividly debated in the field today, and researchers differ greatly in their stands.

Andersson’s (2018) investigation, based on interviews with 31 migration researchers in Norway about their conception of their public role and research communication ideals, clearly showed these different research ideals. She identified four archetypes based on researchers’ ideals for research communication – the purists, the pragmatists, the critics, and the activistsFootnote 3 – ranging from those striving for strict objectivity and neutrality, on the one hand, to those who consider their responsibilities as encompassing active efforts to influence policy makers and achieve social change, on the other. The research activists in Andersson’s study expressed a clear aim to achieve social change and influence policy and considered policy makers to be an explicit audience for research communication. Some research activists reported working closely with different groups and organizations to achieve political and social change. One researcher in Andersson’s study put it this way: “Social science should be an intervention in society. The aim is to influence the public opinion, which is the only way to make politicians act”Footnote 4 (Andersson, 2018:89).

An important contribution to the discussion about academics’ engagement in policy questions is the work by the American sociologist Patricia Hill Collins on intellectual activism (Collins, 2013a). As explained by Contu (2018):

Intellectual activism invites us to become aware of our role and our position in social reproduction and social change. It invites us to make a clear stand on which kind of world we want and what kind of people we want to be by making our everyday work at the service of progressive social, economic and epistemic justice, in whatever way we can and in the issues that are most salient in the conditions where we live. (Contu, 2018: 285)Footnote 5

Collins points to two primary strategies of intellectual activism. One is to “speak the truth to power”, challenging existing discriminatory policies, structures and practices. Collins underscores that this strategy is often most effectively done as an insider, which in turn requires learning to speak the language(s) of power convincingly. The other strategy, “speaking the truth to the people”, emphasizes the importance of talking directly to the masses. Collins points to education and teaching as an important arena for intellectual activism, recognizing teaching as a profoundly political act (Katz-Fishman, 2015).

Collins points to the rediscovery of public sociology in the US as an academic field that has provided a vocabulary for talking about issues of intellectual activism (Collins, 2013b). In his speech For Public Sociology, the presidential address to the American Sociological Association (ASA) in 2004, Michael Burawoy encouraged sociologists to take a more active, participatory role in the public debate and engage more directly in communication with a non-academic audience (Burawoy, 2005). Burawoy’s plea led to a lively debate in the field, and the following year a series of papers discussing his speech was published in a special issue of The British Journal of Sociology. In one of these papers, Etzioni argued that being a public sociologist implies taking a normative position and an active role, stressing that:

[e]very public sociologist must decide how far along the action chain he or she is willing to proceed. […] The further one goes, the more of an activist one becomes and the more likely it is that one will evoke the ire of those who firmly believe in leaving the academic ivory tower is bound to undermine scholarship. (Etzioni, 2005:375)

Like in sociology, a more participatory and politicized linguistics has emerged the past decades, building on the early work of Joshua Fishman in the 1970s (Flores & Chaparro, 2018; Florey, 2008) and clearly formulated by Lo Bianco & Wickert, among others: “[…] we need to be conscious of our roles as active participants in influencing policy or, even more directly, in making policy” (Lo Bianco & Wickert, 2001:2). Similar ideas are expressed by Florey, Penfield & Tucker (2009), who encourage linguists to reconsider their roles and engage more actively in language activism. Combs and Penfield (2012) define language activism as “[…] energetic action focused on language use in order to create, influence and change existing language policies” (Combs & Penfield, 2012: 462), and they, too, call upon linguists to “transform our perhaps passive roles related to language issues into more active efforts to promote and participate in language activism and the process of making and influencing language policies” (Combs & Penfield, 2012: 474).

Within this new participatory linguistics, activism manifests itself in different ways and contexts. Language activism is perhaps most strongly associated with revitalization efforts of indigenous languages, both as a result of efforts from within the endangered language communities and from the outside (Hinton et al., 2018). Language activists also play an important role in changing policy to achieve social justice for migrants and other minoritized language users (Avineri et al., 2018), and many linguistics in the field of second-language acquisition (SLA) fight for minoritized children’s right to use their mother tongue in schooling and education, and work actively to influence and develop education policy in this area (Skutnabb-Kangas et al., 2009; Van Avermaet et al., 2018, Dewaele et al., 2022). As Hudley puts it: “At the heart of a linguistics-centered social justice framework is the most basic right of a speaker: the right to speak his or her language of choice at all times” (Hudley, 2013:2). The linguistic rights of a speaker are also central in the Linguistic Human Rights approach linking language to human rights (Skutnabb-Kangas, 1995). Probably the most systematic, long-term efforts towards achieving a recognition of language rights as human rights at an international level, is the important work of the Council of Europe Department of Language Education and Policy, as summarized by Joe Sheils, its former Head of Department:

Our policy work […] aims to promote the development of language policies that are not simply dictated by economic considerations, but take full account of social inclusion, stability, democratic citizenship and linguistic rights. The promotion of linguistic diversity and opportunities for language learning are <sic> an issue of human rights and democratic citizenship on a European scale. (Sheils, 2001)

Within the Council of Europe, the LIAM-group (Linguistic Integration of Adult Migrants)Footnote 6 has taken several important initiatives over the years to gear European migration policies towards a greater concern for human rights and social justice, in line with the CoE central values (CoE 2020b). Also worth mentioning is the network of SLA-linguists, psycholinguists and teachers focusing particular attention on the understudied group of non-literate or low-literate adult migrants,Footnote 7 (Tarone, 2010), a group for which special attention in language teaching and testing is critical (Carlsen, 2017; Rocca et al., 2020).

Language testers’ responsibility for justice

Language testers share many similarities with professionals in other areas of SSH, particularly those who work with politicized topics of public controversy. In this paper, we argue that – perhaps even more than other researchers in SSH – language testers have an ethical and professional responsibility for justice and a particular responsibility to take action when their tests are misused.

In language testing, the concept of validity is central. Validity is another word for test quality, and definitions of validity therefore decides what professional language testers consider to be their professional responsibility (Chalhoub-Deville & O’Sullivan, 2020). Validity has been defined in different ways through the history of LT, and its content has changed considerably, from meaning the degree to which the test measures what it is supposed to measure to a notion encompassing the relevance and utility, value implications and social consequences of tests (Chapelle, 2012). The American psychologist Samuel Messick has played a central role in this redefinition of validity. Messick’s concept of validity foregrounds the consequences of score interpretations and use. According to Messick, validity is:

[…] an integrated evaluative judgement of the degree to which empirical evidence and theoretical rationales support the adequacy and appropriateness of inferences and actions based on test scores or other modes of assessment […]. (Messick, 1989:13)

The social consequences of tests on those affected by them form part of validity, as underlined by Messick (1996: 251). Validity, then, does not only involve empirical questions of truth, but also questions of worth (Messick, 1998). Messick thereby rejects the idea of LT as a value-free science (McNamara, 2006:40). Most professional language testers today refer to his definition of validity, as it strongly influences the guidelines for good practice and professional and ethical conduct of the large LT organizations such as ILTA (International Language Testing Association), EALTA (European Association for Language Testing and Assessment) and ALTE (Association of Language Testers in Europe). Language testers and test organizations who build their work on the definition of validity presented by Messick can therefore not choose to ignore questions of values, ethics and consequences, as they are embedded in the very definition of test quality.

Within the field of LT, the direction focusing most consistently and explicitly on language test misuse and potentially harmful consequences of language tests, is that of Critical language testing (Shohamy, 1998, 2017). Critical language testing stresses the inherently political power of language tests. Posing critical questions about test policy, test impact and test consequences, is a core commitment of Critical Language Testing, and as Shohamy argues:

[w]e need to study how language tests affect people, societies, teachers, teaching, students, schools, language policies, and language itself. We need to examine the ramifications of tests, their uses, misuses, ethicality, power, biases, and the discrimination and language realities they create for certain groups and for nations, and we need to use a critical language testing perspective. All these topics fall under the theoretical legitimacy of Messick’s (1994, 1996) work on the consequences and values of tests. (Shohamy, 2007:145)

The ground-breaking writings of Shohamy and McNamara the past 30 years have contributed significantly to raising awareness in the LT community that language tests can be, and indeed are being, deliberately misused by those in power to control the lives of those without (Shohamy & McNamara, 2009:1) and that even when the intended purpose of a test is positive, the unintended consequences may be detrimental (Shohamy, 2001; Fulcher, 2005). A growing number of language testers and test researchers have started to follow their lead by raising critical questions about test use and misuse and taking their responsibility for test misuse seriously (Bruzos et al., 2018; Carlsen, 2019; Khan, 2019; Pochon-Berger & Lenz, 2014; Strik et al., 2010; Van Avermaet & Pulinx, 2014).Footnote 8

Language test activism (LTA)

Using Messick’s validity framework as the theoretical rationale and continuing the focus on test misuse among proponents of critical language testing, the logical next step for language testers is to take on a more active role in order to prevent language test misuse and harmful consequences of tests (Carlsen, 2019; Carlsen & Rocca, 2021). An active, participatory role for language testers is in line with recent development in other fields within the SSH, such as intellectual activism, public sociology and linguistic activism, as we saw above. However, despite a general agreement that consequences are part of what determines a test’s validity and that critical questions regarding the use, misuse and impact of tests need to be raised, not all language testers are willing to take on the role of language test activists. McNamara proposes one possible reason for their reservation, namely that language testers in general are ill-equipped through their formal training to operate in the interface between language tests and policy (McNamara, 2009). Academics’ lack of understanding of the power relations and policy discourse referred to as policy literacyFootnote 9 has been repeatedly underlined by Lo Bianco over the past decades (2001, 2014), and is a point taken up by Deygers and Malone (2019) in the context of LT. As a step towards equipping language testers to take a more active role, this paper introduces a model of language test activism. The purpose of the model is to illustrate different contexts and areas for LTA and to widen language testers’ conception of what LTA is and can be. The model is not intended to be all-encompassing and definitive; on the contrary: Activism, also in the field of LT, takes many forms and changes with context and time.

A model of language test activism

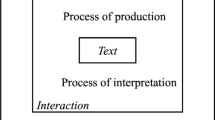

A model of LTA needs to cover areas related to LT in the widest sense,Footnote 10 and to consider both top–down approaches, such as efforts directed towards policy makers or public opinion, and bottom–up approaches, like test development and teacher training. The different areas are interrelated and often interact and influence each other. To achieve change, language test activists will often have to work actively in different areas simultaneously. For example, a language test activist may conduct test research to gather evidence to use in communication with policy makers and in newspaper articles to inform and influence public opinion. These research findings may also be a driver for change in test development, and they can be used to inform pre-service and in-service teachers about harmful consequences of tests, which may in turn inspire and give teachers courage to engage in intellectual activism themselves from their contexts and positions. The model should not be understood as suggesting that components that are next to each other influence each other to a larger degree than components that are further apart (Fig. 1).

Starting at the top of the model, LTA in the area of policy means taking action to influence or change policies in which language tests form a part. It includes writing responses to public hearings when tests are introduced as part of migration and integration policies, and to speak out when tests are used in potentially harmful ways in the educational system, or when employers at local, regional or national levels set unjustifiable language requirements to regulate entrance to the labour market. Sometimes language test activists need to engage directly in communication with policy makers to explain what the test scores and proficiency levels mean, what the test measures, and what the consequences might be for different groups of migrants if requirements are set too high. LTA in the policy area also means getting involved directly in developing language test policy at national or regional levels. Activism at this level is what Collins refers to as “speaking the truth to power” (Collins, 2013a).

LTA in the area of public opinion means taking an active role to prevent test misuse by informing the general public about potentially harmful consequences of tests on individuals and society. In democratic societies people choose their politicians, hence informing and influencing public opinion is important in order to achieve political change. Being a language test activist often implies writing newspaper articles, taking part in public debates and meetings, radio and TV-interviews, etc. In many cases, it also means putting LT and language test policy on the agenda of the public debate. This is what Collins refers to as “speaking the truth to the people” (Collins, 2013a).

Another important area that language test activists can influence, is pre-service and in-service teacher training. Assessment is an integrated part of teachers’ everyday classroom activities. In addition, teachers are often the ones preparing learners for standardized language test and explaining matters related to the test to their pupils (and parents). Language teachers therefore play a crucial role when it comes to promoting the tests, which is important for the tests to have positive washback effect on learning (Wall, 2012). In addition, they are the ones who experience how tests and test results affect test takers, and they are therefore in a position where they can speak out against misuse of tests when necessary. To do this, teachers need knowledge and skills in the field referred to as language assessment literacy related to language assessment, test use and consequences. Several scholars have pointed to the importance of teachers having assessment literacy (Inbar-Lourie, 2017; Taylor, 2009), yet studies have shown that language teachers typically lack formal training through which their assessment literacy can be enhanced (Vogt & Tsagari, 2014).

Language test activists can also work to achieve social justice within the area of practical test development, where they may take action to focus attention on vulnerable and marginalized test-taker groups, such as refugees, low-literate learners, LGBTQ+ , candidates with disabilities or post-traumatic stress disorder, etc. Giving all candidates equal opportunities to perform their best may be considered central to the enterprise of developing high-quality and fair tests, and hence not something that requires particular advocacy. In practice, however, taking these concerns seriously may require considerable extra time and resources, something that those who pay for the test may not always be willing to provide unless they are convinced of its necessity. Language test activists are also the ones in a team of test developers who dare speak out and oppose the use of test items, topics or task illustrations which may reproduce gender stereotypes or other prejudices, and they are the ones who are brave enough to advocate for marginalized groups even when it requires extra work, time and resources.

Finally, LTA in the area of research implies using language test research as a driver for change. It implies focusing research attention on topics such as why tests are introduced; what their consequences on individuals and society may be; how vulnerable groups are affected by tests; how tests influence migrants’ opportunities in education and labour, and their democratic rights; how tests and requirements may affect democracy, labour market and the welfare state in the long run; and how they relate to human rights – in short, asking questions about test use, misuse and consequences, as argued by Shohamy over the past 20 years (Shohamy, 1998, 2001, 2006, 2007). To some, it may look like a contradiction in terms that researchers can be activists and that activists can use research as part of their action. As discussed earlier in this paper, some would argue that researchers should strive towards being value neutral and objective and have no other agenda than the pursuit of truth. Others, however, would argue that in the SSH truth doesn’t exist as such, only more or less reasonable and valid interpretations of truth. Hence, researchers in these fields cannot achieve objectivity and value-neutrality but should strive towards being open about and reflect upon their own values and how these may affect their research. Importantly, the quality of research and the trustworthiness of research findings do not depend on whether researchers are objective and value-neutral or inspired by a will to make a change, but on the scientific quality of the design of the study, the quality of the hypotheses, the solidity of the data and the thoroughness and depth of the discussion of the findings. To achieve political and social change, arguments need to be backed by empirical evidence, hence research and research findings have an important role to play in LTA as in intellectual activism in general.

Examples from Norway & Italy

In the following, we will illustrate the LTA model with real-life examples of activism in Norway and Italy related to policy, public opinion, teacher training, test development and research.Footnote 11 In order to grasp the overall picture, a brief introduction to the migration context and integration models for the two countries will be provided.

Norway has a total population of 5.4 million. 14.7 percent are immigrants, and 3.5 percent are children of immigrants born in Norway. The largest immigrant groups are migrant workers from Poland, Lithuania and Sweden, while refugees make up 4.4 percent of the total population (SSB, 2020). For refugees and people arriving under family reunion rules, language and knowledge of society (KoS) courses are compulsory and free of charge, as is passing a test of Norwegian and KoS. Norwegian Directorate for Higher Education and Skills (HK-dir), a directorate under the Ministry of Knowledge (Kunnskapsdepartementet), is in charge of both language and KoS curricula, courses and tests. In 2015–2016 the conservative coalition government introduced a series of retrenchments in the migration legislation. In 2017, passing the oral part of the language test and the KoS test was made a condition for permanent residency (level A1 of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) (CoE, 2001) and citizenship (CEFR-level A2, raised to B1 in 2022).

Italy has a total population of near 60 million, out of which 8.8 percent are immigrants. The largest migrant communities come from Romania, Morocco and Albania. Within compulsory education 30 percent of students are migrants, of which 54 percent are born in Italy. The number of refugees is limited to 3.4 in 1 000 habitants.Footnote 12 Language and KoS courses are free of charge, with learning opportunities provided by a state school called CPIA. In terms of compulsory tests, three laws introduced, in turn, the CEFR level A2 for permanent residency (2010), the CEFR level A2+KoS for temporary residency (2014) and, more recently, the CEFR level B1 for citizenship (2018).

Policy examples

In 2015, the Italian Ministry of Interior introduced what is referred to as the Integration Agreement, deciding that migrants applying for a renewal of their temporary residency would have to demonstrate a proficiency in Italian in all four skills at the CEFR level A2, in addition to passing a separate multiple-choice test of KoS in writing, requiring reading skills and knowledge of abstract concepts. The ministry organized a three-day seminar in order to operationalize these two separate tests.

During the seminar, participants, including language testers and teachers from CPIAs, expressed their opposition to the ministry’s proposal, pointing in particular to the specific challenges migrants with low literacy profiles would have when it came to meet these requirements. After long discussions, the joined efforts of language teachers and testers finally convinced the policy makers to reconsider their original plan. The concrete outcome of language teachers and testers speaking out to policy makers, then, was a unified A2-KoS oral test using spoken interaction tasks and covering contents more clearly related to the daily life of migrants, such as the ability to use key sectors like public services, education, work and health care. As a result of these efforts of LT activism, Italy is to date one of the very few Council of Europe member states having only oral requirements for both language and KoS for temporary residency.Footnote 13

Public opinion examples

In Norway, like in other European countries, employers in private companies as well as employers at local, regional and national levels, often require non-native speaking job applicants to demonstrate a certain level of the language(s) of the host country (Carlsen et al., 2019). The requirements typically relate to the proficiency levels of the CEFR from A1 to C2, and test certificates are often necessary to prove that the applicant has attained the required level. While one may question the ethical and professional legitimacy of language requirements for residency and citizenship purposes, language requirements for labour is not so much a question of whether the practice is justifiable per se, as it is a question of what level is necessary, i.e. high enough to ensure that employers can do their job, but also not so high that non-native speakers are shut out from the labour market. To determine what level ought to be required, a needs analysis for the profession in question should be carried out (Bachman & Palmer, 1996). This, however, is rarely done (Haugsvær, 2018). Moreover, many employers lack knowledge about the content of the CEFR-levels they use when setting requirements (Haugsvær, 2018), and the levels required seem often to be rather arbitrary. Since test developers are the ones who best know what their tests measure, what the levels represent, and how difficult it is to reach a certain level for all or specific groups of candidates, this is an obvious situation in which the expertise of language test professionals is sorely needed and where active engagement from test developers may prevent discrimination in the labour market.

The past years, we have witnessed numerous examples of employers at local, regional and national levels in Norway requiring language proficiency levels that are clearly too high to be justifiable. There have been several examples of employers proposing academic language requirements (B2) in all four language skills for non-academic, practical occupations such as taxi drivers, kindergarten assistants and healthcare assistants. Language test developers have engaged actively to stop such requirements from being used and to argue in favour of a profiled approach, e.g. differentiated requirements in the different language skills. On the one hand, language test developers have taken an active role informing and influencing the public opinion and employers through newspaper articles, radio interviews and public meetings. In addition, they have communicated with the employers directly through letters, meetings and responses to public hearings. Language test developers’ effort to work against discriminating language requirements in the labour market illustrates how activists need to operate at several levels – the policy level and the public level – simultaneously, and to build their argument on test research. This is also an example of successful intervention that has led to employers reconsidering and lowering their original level requirements.

Test development examples

In Norway, refugees and people arriving under family reunion rules have a right and a duty to take part in Norwegian and KoS classes (Norwegian Ministry of Knowledge, 2020). In order to give tailored language courses, participants are divided into three tracks based on their degree of prior schooling and levels of literacy. Track 1 is for adult learners with no or little prior schooling and low levels of literacy (LESLLA-learners). The track for LESLLA-learners has slower progression, lower learning aims and more hours of instruction. In 2013 it was made compulsory for all participants in the introductory programme to take a test of Norwegian when the programme ended. Hence, LESLLA-learners became part of the test population for the first time. At the same time, the test developers were commissioned to develop a new test of Norwegian for adult migrants, which meant an opportunity to take these learners into consideration from the very beginning. Several measures were taken to ensure that these most vulnerable and often marginalized test-takers were given the best possible chance to show their language abilities (Carlsen, 2017).

Since LESLLA-learners lack in print literacy (reading and writing), as well as experience with testing, i.e. test literacy (Allemano, 2013), catering for this test-taker group means taking measures to face both challenges (Carlsen, 2017). Firstly, to prevent the lack in general literacy from affecting test scores also in the tests of the oral modes, it is crucial that the different language skills be tested separately, or at least that the oral and the written skills be separated. In Norskprøven for voksne innvandrere the skills are measured in separate tests yielding individual CEFR-based results: The listening tasks ranging from level A1 to A2 require no reading whatsoever, and also at the B1 level, reading skills are kept at a bare minimum. Since the test is digital, test formats and illustrations are used in new and creative ways to allow candidates to give their responses without having to read or write, taking into account learners’ uneven profiles and making sure their weakest skills (often written production) does not affect their scores on other parts of the test, as recommended by the CoE (Rocca et al., 2020) and underlined in recommendations and guidelines provided by the ALTE LAMI-group.Footnote 14

To accommodate to LESLLA-learners’ lack of test-literacy, test developers took great care that the test formats were as simple and self-explanatory as possible. In addition, all task formats that appear on the test are made available in online example tests so that test-takers with little prior test experience can get familiarized with the task formats they will meet on the real test. Teachers are encouraged to prepare their students for the test in order to reduce stress and the effect of test-wiseness or lack of such. Another measure that was taken to reduce stress and anxiety in the test situation, was to have a paired exam format for the oral production and interaction test. Video-recorded examples of the oral test are available to candidates.

A similar concern for LESLLA-learners can be observed in Italy: During the past decade, there has been harsh debates and strong controversies as a result of the fact that the compulsory A2 written test for permanent residency has a failing rate of up to 70 percent among LESLLA candidates. In 2020, the CLIQ association, formed by the four evaluation centers recognized by the state,Footnote 15 obtained recognition from the Ministry of Interior (DLCI, 14 May 2020) of the importance of developing a test tailored to a larger degree of non-literate and low-literate migrants, which focused only on oral reception, production and interaction. Therefore, since June 2020, LESLLA learners can achieve permanent residency by passing a speaking test only: Their rights to be assessed on the skills they can reasonably demonstrate has finally been affirmed. This represents a sign of ethical use of tests, in that respect is shown for the most vulnerable users, in accordance with the concern for human rights and the modular approach highlighted in the CEFR as key also for language certification (CoE, 2001:176).

Teacher training examples

Already in 2005, professional language testers in Norway, as among the first in Europe, developed a university course in language testing and assessment. Language testers have been responsible for developing the content of the course and for providing the lectures. The purpose of the course is to raise teachers’ language assessment literacy through familiarizing them with key concepts in LT and assessment. The course covers central topics like validity and validation; communicative language tests; the CEFR and the CEFR Companion Volume (CoE, 2020a); the measurement of reading, listening, speaking and writing; classroom assessment and assessing young learners; fairness; justice; test ethics and test impact. The course has a strong test critical approach aimed at developing students’ critical thinking about test ethics and test misuse. Finally, in 2019, language testers authored an introductory book in language testing and assessment written in Norwegian containing ample examples from language tests and testing policy in a Norwegian context (Carlsen & Moe, 2019). From 2021 the course has been available online to reach a wider audience.Footnote 16

Research examples

We could have given several examples of research focusing on test use and test impact related to migration policies, education, the labour market, etc. We have chosen a research example related to admission tests for foreign students in higher education that illustrates a successful intervention from language test activists. In Norway, as in many other European countries (Deygers et al., 2018), foreign students need to document a certain level of proficiency in the majority language when applying for access to higher education, and they can do so through a series of different tests of Norwegian.Footnote 17 A correlation study of the entrance requirements of two of the entrance tests revealed a significant lack of equivalence in terms of the actual proficiency levels required for admission, passing the test being considerably easier for one of the tests than for the other (Andersen, 2007). This systemic unfairness would not only impact students’ opportunities to enter higher education, but also the calculation of points necessary to enter certain study programmes like teacher education, medicine, law studies or engineering, since the Norwegian Universities and Colleges Admission Service, NUCAS (Samordna Opptak), recodes applicants’ scores on the Norwegian tests into the same 1–6-point scale. The points obtained, both on the Norwegian test and on prior education, form the basis for application to education programs that require a certain number of points to enter.

In 2016 test developers took action to rectify what they believed to be a serious unfairness in the admission and recoding practice and initiated a survey to investigate the correlation between the three main tests of Norwegian for university admission. Again, the findings of the study revealed a considerable and significant discrepancy between the admission requirements for the different tests, passing one test being significantly easier than passing the others (Samfunnsøkonomisk analyse, 2017). A meeting between test developers at Skills Norway,Footnote 18 NUCAS and policy makers responsible for higher education admission was arranged, and the results of the report were presented and discussed.Footnote 19 As a direct consequence, the recoding system was changed to ensure a fairer recoding practice, giving applicants with higher levels of proficiency more points than those with lower levels, thus reflecting their real level of language competence and making the calculation of points more fair and just and less dependent on the particular test of Norwegian that the aspiring students had happened to take.

Concluding remarks: what do language test activists risk?

Language test activism is not risk free, and there are numerous reasons why professional language testers may be reluctant to get more actively involved in policy questions. A reason already mentioned above is language testers’ lack of relevant training for active critique of, or involvement with, language test policy. To influence and change policy and society through dialogue with policy makers requires skills and expertise that far from all language testers possess, as argued above. McNamara points to lack of training as one reason why testers don’t engage more actively, stating that language test specialists “[…] are usually unsuited to a role of public policy advocacy which is what is required to alter it […]” (McNamara, 2006:37).

Another possible reason is the fear of not being taken seriously as professionals. Even when activism is defined broadly, as it is in this paper, activism requires a value stance, and, as we have seen, researchers and professionals differ when it comes to their willingness to be open about their values: Many researchers strive to remaining value-neutral and objective, what Etzioni (2005) refers to as a position to stay put in the “ivory tower”. Collins emphasizes that intellectual activists run the risk of being marginalized by colleagues who consider their efforts to be non-academic. Intellectual activism is regarded with suspicion and often meet opposition from forces that seek to maintain status quo (Contu, 2020).Footnote 20 There is indeed a very real danger that opponents will try to dismiss research activists as being untrustworthy.Footnote 21

Moreover, language testers engaging in the public debate risk threats and public harassment. Engaging actively in public debate, even just presenting research results and empirical facts in value-loaded, politicized fields like migration, language learning and testing, comes at a cost. When newspaper articles are published online, anonymous harassment is to be expected. This risk has not decreased the past years, as the public debate over politized value questions tend to be severely polarized and overly simplified.

A final likely reason why many language testers do not take a more active role when it comes to speaking out against test misuse, is that they want to keep their jobs. Many language testers work for large commercial test companies and criticizing the way the tests are being used might not be well received, as it would be bad for business. Similarly, many language testers work on assignment for the policy makers. Once one has chosen to accept a position, a certain degree of loyalty with one’s employer is expected, making it difficult or even impossible to speak out against test misuse and harmful consequences. In the end, it comes down to the hard choice of following one’s ideals and values or “withdraw one’s services”, as stated in ILTAFootnote 22 Code of Ethics, Principle 9. This is a choice not every language tester is in a position to make.

We hope, however, to have shown that language test activism may take many forms. In light of Collins’s and Contu’s arguments for intellectual activism in general, and as evident from our model and the examples given above, language test activism may also mean working from within a language test organization, being willing to walk that extra mile to make sure ones tests cater for vulnerable and marginalized test-taker groups, being willing to explain the meaning of test scores to teachers and the public, and to engage in dialogue for change with policy makers. Following Collins, intellectual activism means being responsible for how our work is put into service to promote social justice from whatever position we are in. The same holds true for language test activism.

Notes

A clear example of this is the language requirements for citizenship in the three Scandinavian countries, Denmark, Norway and Sweden: At present, Denmark has the strictest requirement in Europe, and demands that citizenship applicants demonstrate an academic level of Danish, while the neighbouring country, Sweden, has no language requirements for new citizens. Norway finds itself somewhere between these two extremes.

This question is closely linked to the issue of scientific objectivity versus subjectivity, or neutrality versus normativity, which has been debated for centuries and was a central topic in the positivist dispute on differences between the social and natural sciences in the 1960s (Adorno et al., 1977).

The Norwegian term used is “påvirkeren”, literally meaning “the influencer”.

Translated from Norwegian, our translation.

Important to note at this point: Despite a will to do good, activists may be unaware or unwilling to acknowledge forms of discrimination or inequalities that they themselves produce, for instance in relation to racial questions, as underscored by (Hudley et al., 2021:14).

This learner group is commonly referred to as LESLLA-learners (Literacy Education and Second Language Learning for Adults), www.LESLLA.org

As Shohamy (2001) points out, even the most perfect test in terms of test-internal qualities may be misused. The focus of this paper is not on how to develop tests that are internally fair and unbiased, which no professional language testers would dispute is their responsibility, but the more controversial question about the responsibility to take active steps to prevent test misuse.

See also Collins’s points about this, mentioned above.

Language tests are part of a larger reality; they are but one factor in integration and education policies, and the language test activist model could surely be complemented by more and other areas in which language test activists may play a role (Spolsky, 2018).

We’ve chosen to give examples from Norway and Italy because those are the local contexts most familiar to us. Day-to-day LTA often take place “away from the media spotlight” (Jenkins, 2017:1445) and is often not documented in scientific papers. It is therefore often only those who have been involved in a particular local context who know what has been done to influence policy and what means have been used.

Caritas e Migrantes, 2020, https://www.caritas.it/caritasitaliana/allegati/9090/RICM_2020_Finale.pdf.

LAMI (Language Assessment for Migration and Integration) is a project group in the European network of language testers ALTE (the Association of Language Testers in Europe): https://www.alte.org/LAMI-SIG.

University for foreigners of Perugia, University for foreigners of Siena, University ‘Roma Tre’, Dante Alighieri society, www.associazionecliq.it

Noran 609 Testing og vurdering av språkferdigheter (Language testing and assessment), University of Bergen Testing og vurdering av språkferdigheiter | Universitetet i Bergen (uib.no).

Skills Norway changed its name to Directorate for Higher Education and Skills in 2021 as it merged with other directorates in charge of higher education in Norway.

Skills Norway never considered trying to lower the admission requirement of their test, however. An earlier study of the predictive validity of the B2-requirement had revealed that this was indeed a necessary level to master academic studies (Carlsen, 2018). B2 ( ±) is also found to be the most commonly required level for admission to higher education in other European countries (Deygers et al., 2018).

Also, researchers and other professionals who strive for neutrality may of course have an impact on policy development. What distinguishes them from activists, is that they do not work openly to make this happen.

Not surprisingly, Anderson (2018) finds that older researchers are more inclined to engage in activism than their younger colleagues who might need to be more careful as they do often not hold permanent positions and will often be concerned about building a scientific career.

The International Language Testing Association https://www.iltaonline.com/.

References

Adorno, T., Albert, H., Habermas, J., Pilot, H. & Popper, K. (1977). The Positivist Dispute in German Sociology. Heinemann Educational Books Ltd.

Allemano, J. (2013). Testing the reading ability of low-educated ESOL learners. Apples– Journal of Applied Language Studies, 7(1), 67–81.

Andersen, R. O. (2007). Korrelasjonsundersøkelsen, Fase 1 (Unpublished report). Norsk språktest.

Andersson, M. (2018). Kampen om vitenskapeligheten. (The fight over science). Universitetsforlaget.

Avineri, N., Graham, L. R., Johnson, E. J., Conley Riner, R. & Rosa, J. (2018). (Eds.). Language and Social Justice in Practice. Routledge.

Bachman, L. & Palmer, A. (1996). Language Testing in Practice: Designing and Developing Useful Language Tests. Oxford University Press

Böcker, A., & Strik, T. (2011). Language and knowledge tests for permanent residence rights: Help or hindrance for integration. European Journal of Migration and Law, 13(2), 157–184.

Bruzos, A., Erdocia, I., & Khan, K. (2018). The path to naturalization in Spain: Old ideologies, new language testing regimes and the problem of test use. Language Policy, 17(4), 419–441.

Burawoy, M. (2005). Response: Public sociology: Populist fad or path to renewal? The British Journal of Sociology, 56(3), 417–432.

Carlsen, C. H. (2017). Giving LESLLA-learners a fair chance in testing. In M. Sosinski (Ed.), Proceedings LESLLA 2016 12th annual symposium, 8–10 September 2016 (pp. 135–148). Universidad de Granada.

Carlsen, C. H. (2018). The adequacy of the B2 level as university entrance requirement. Language Assessment Quarterly, 15(1), 75–89.

Carlsen, C. H. (2019). Justice in practice – what it means and why it is our responsibility. 53 ALTE conference, Gent, Belgium.

Carlsen, C. H., Deygers, B., Zeidler, B., & Vilcu, D. (2019). CEFR-based language requirements in the European labour market. In Huhta, A., Erickson, G. & Figueras, N. (Eds.). Developments in Language Education: A Memorial Volume in Honour of Sauli Takala. EALTA.

Carlsen, C. H. & Moe, E. (2019). Vurdering av språkferdigheter. Fagbokforlaget.

Carlsen, C. H., & Rocca, L. (2021). Language Test Misuse. Language Assessment Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2021.1947288

Chalhoub-Deville, M. & O’Sullivan, B. (2020). Validity: Theoretical Development and Integrated Argument. British Council Monographs.

Chapelle, C. (2012). Conceptions of validity. In Fulcher, G. & Davidson, F. (Eds.) The Routledge handbook of language testing. pp. 35–47.

Collins, P. H. (2013a). On intellectual activism. Temple University Press.

Collins, P. H. (2013b). Truth-telling and intellectual activism. Context, 12(1), 36–39.

Combs, M. C. & Penfield, S. D. (2012). Language activism and language policy. In Spolsky, B. (Ed.) The Cambridge handbook of language policy. pp. 461–474.

Contu, A. (2018). ‘… The point is to change it’ – Yes, but in what direction and how? Intellectual activism as a way of ‘walking the talk’ of critical work in business schools. Organization, 25(2), 282–293.

Contu, A. (2020). Answering the crisis with intellectual activism: Making a difference as business schools scholars. Human Relations, 73(5), 773–757.

Council of Europe. (2001). The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. Cambridge University Press.

Council of Europe (2020), Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: learning, teaching, assessment – Companion volume with new descriptors, Council of Europe.

Dewaele, J.-M., Bak, T. H., & Ortega, L. (2022). Why the mythical 'native speaker' has mud on its faceSlavkov, N., Kerschhofer-Puhalo, N. & Melo-Pfeifer, S. M. (Eds.) (2022) Changing Face of the "Native Speaker": Perspectives from Multilingualism and Globalization. Mouton De Gruyter.

Deygers, B., & Malone, M. (2019). Language assessment literacy in university admission policies, or the dialogue that isn’t. Language Testing, 00, 1–22.

Deygers, B., Zeidler, B., Vilcu, D., & Carlsen, C. H. (2018). One framework to unite them all? Use of the CEFR in European University Entrance Policies. Language Assessment Quarterly, 15(1), 3–15.

Etzioni, A. (2005). Bookmarks for public sociologists. The British Journal of Sociology, 56(3), 373–378.

Extra, G. & Spotti, M. (2009). Testing regimes for newcomers to the Netherlands. In Extra, G., Spotti, M. & van Avermaet, P. (Eds.). Language Testing, Migration and Citizenship.Cross-national Perspectives on Integration Regimes. Advances in Sociolinguistics. Continuum (pp. 128–147).

Flores, N., & Chaparro, S. (2018). What counts as language education policy? Developing a materialist Anti-racist approach to language activism. Language Policy, 17, 365–384.

Florey, M. (2008). Language activism and the “new linguistics”: expanding opportunities for documenting endangered languages in Indonesia. In P. K. Austin (Ed.). Language Documentation and Description, vol 5. SOAS. Pp. 120–135.

Florey, M., Penfield, S. & Tucker, B. (2009). Towards a framework for language activism. Paper presented at the 1st International Conference on Language Documentation and Conservation (ICLDC), 14 March 2009, Honolulu, Hawaii [Online]. Available at http://hdl.handle.net/10125/5014

Hamp-Lyons, L. (1997). Ethics in language testing. In Clapham, C. & Corson, D. (Eds.). Encyclopedia of language and Education, Vol. 7: Language Testing and Assessment (pp. 323–333). Kluwer Academic Publisher.

Haugsvær, K. (2018). Arbeidsgiveres kjennskap til og bruk av norskprøver for voksne innvandrere. (Employers familiarity with and use of the test of Norwegian for adult migrants). Skills Norway, Report.

Hill Collins, P. (2013a). On Intellectual Activism. Temple University Press

Hill Collins, P. (2013b). Truth telling and intellectual activism. Contexts, 12(1), 36–39.

Hinton, L., Huss, L. & Roche, G. (2018) (Eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Language Revitalization. Routledge.

Hudley, A. H. C. (2013). Sociolinguistics and social activism. In R. Bayley, R. Cameron, & C. Lucas (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Sociolinguistics. Oxford University Press.

Hudley, A. H. C, Mallinson, C. & Bucholtz, M. (2021). Toward racial justice in linguistics: Interdisciplinary insights into theorizing race in the discipline and diversifying the profession. Language. [forthcoming issue] https://dl.orangedox.com/W3CerHXKR89AnMzF6V

ILTA (2020). Code of Ethics. ILTA Code of Ethics - International Language Testing Association (iltaonline.com)

Inbar-Lourie, O. (2017) Language assessment literacy. In Shohamy, E., Or, l, May, S. (Eds.) Language testing and assessment. encyclopedia of language and education (3rd ed.). Springer.

Jenkins, K. (2017). Women anti-mining activists’ narratives of everyday resistance in the Andes: Staying put and carrying on in Peru and Ecuador. Gender, Place & Culture, 24(10), 1441–1459.

Katz-Fishman, W. (2015). Review of on intellectual activism. Contemporary Sociology, 44(1), 44–45.

Khan K. (2019). Becoming a citizen. Linguistic trials and negotiations in the UK. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Khan, K. & McNamara,T. (2017). Citizenship, immigration laws, and language. In Canagarajah, S. (Ed.). The Routledge Handbook of Migration and Language. Routledge.

Lo Bianco, J. (2001). Policy Literacy. Language and Education, 15(2&3), 212–227.

Lo Bianco, J. & Wickert, R. (2001). Introduction: Activists and policy politics. In Lo Bianco, J. & Wickert, R. (Eds.). Australian Policy Activism in Language and Literacy, pp. 1–9.

Martin, D., Hanson, S., & Fontaine, D. (2007). What counts as activism?: The role of individuals in creating change. Women’s Studies Quarterly, 35(3/4), 78–95.

McNamara, T. (2005). 21st century shibboleth: Language tests, identity and intergroup conflict. Language Policy, 4, 351–370.

McNamara, T. (2006). Validity in language testing: the challenge of Sam Messick’s legacy. Language Assessment Quarterly, 3(1), 31–51.

McNamara, T. (2009). Language tests and social policy: A commentary. In G. Hogan-Brun, C. Mar-Molinero & P. Stevenson (Eds.). Discourses on language and integration: Critical perspectives on language testing regimes in Europe. John Benjamins.

McNamara, T., & Shohamy, E. (2008). Language tests and human rights. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 18(1), 89–95.

Messick, S. (1989). Validity. In R. L. Linn (Ed.), Educational Measurement (pp. 13–104). Mcmillan.

Messick, S. (1996). Validity and washback in language testing. Language Testing, 13, 241–256.

Messick, S. (1998). Validity: A matter of consequences. Social Indicators Research, 45(1–3), 35–44.

Norwegian Ministry of Knowledge. (2020). Integreringsloven. (The law of integration).Lov om integrering gjennom opplæring, utdanning og arbeid (integreringsloven) - Lovdata

NUCAS (Samordna Opptak) (2018). Recoding of grades to common scale.

Pochon-Berger, E. & Lenz, P. (2014). Language requirements and language testing for immigration purposes. A synthesis of academic literature. Report of the Research Centre on Multilingualism.

Rocca, L., Carlsen, C. H. & Deygers, B. (2020). Linguistic Integration of Adult Migrants: Requirements and Learning Opportunities. Report on the 2018 Council of Europe and ALTE Survey of Language and Knowledge of Society Policies for Migrants. Council of Europe.

Samfunnsøkonomisk analyse. (2017). Undersøkelse av samsvar mellom prøver i norsk språk for opptak til høyere utdanning Rapport 67–2017 (Survey about the correlation between tests in Norwegian for admission to higher education. Report 67–2017).

Sheils, J. (2001). Information Bulletin. April 7. http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/elc/bulletin/7/en/shiels.html

Shohamy, E. (1998). Critical language testing and beyond. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 24, 331–345.

Shohamy, E. (2001). The power of tests. A Critical Perspective on the Use of Language Tests. Pearson Education Ltd.

Shohamy, E. (2006). Language policy. Routledge.

Shohamy, E. (2007). Tests as power tools looking back, looking forward. In J. Fox, M. Wexche, D. Bayliss, L. Cheng, C. Turner, & C. Doe (Eds.), Language testing reconsidered. University of Ottawa Press.

Shohamy, E., & McNamara, T. (2009). Language tests for citizenship, immigration and asylum. Language Assessment Quarterly, 6(1), 1–5.

Simpson, J. & Whiteside, A. (2015) (Eds.). Adult langauge education and migration: Challenging agendas in policy and practice. Routledge.

Skutnabb-Kangas, T. (1995) (Ed.). Linguistic Human Rights. De Gruyter.

Skutnabb-Kangas, T., Phillipson, R., Mohanty, K. & Panda, M. (2009) (Eds.) Social Justice through Multilingual Education, Channel View Publications, 2009. ProQuest Ebook Central.

Spolsky, B. (2018). A modified and enriched theory of language policy (and management). Language Policy., 18, 323–338.

SSB (Statistisk Sentral Byrå). (2020). https://www.ssb.no/

SSB (Statistisk Sentral Byrå). (2021). https://www.ssb.no/statbank/table/07114/chartViewLine/

Strik, T., Böcker, A., Liten, M., & van Oers, R. (2010). The INTEC project: synthesis report. integration and naturalisation tests: The new way to European citizenship. Centre for Migration Law.

Tarone, E. (2010). Second language acquisition by low-literate learners: An under-studied population. Language Teaching, 43, 75–83.

Taylor, L. (2009). Developing assessment literacy. University of Bedfordshire.

Van Avermaet, P., & Pulinx, R. (2014). Language testing for immigration to europe. In A. Kunnan (Ed.), The companion to language assessment (pp. 1–14). Wiley.

Van Avermaet, P., Slembrouck, S., Van Gorp, K, Sierens, S. & Maryns, K. (2018). (Eds.) The Multilingual Edge of Education. Palgrave Macmillan.

Vogt, K., & Tsagari, D. (2014). Assessment literacy of foreign language teachers: Findings of a European study. Language Assessment Quarterly, 11(4), 374–402.

Wall, D. (2012). Washback. In Fulcher, G. & Davidson, F. (Eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Language Testing. Routledge, pp.79–92.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the insightful comments and helpful advice from two anonymous reviewers of this paper, which have contributed significantly to its quality. We also wish to thank the editors of this special issue of Language Policy for the opportunity to be part of this issue on the important topic of advocacy in language policy.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Western Norway University Of Applied Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Carlsen, C.H., Rocca, L. Language test activism. Lang Policy 21, 597–616 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-022-09614-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-022-09614-7