Abstract

This article examines de jure language officialization policies in Andorra and Luxembourg, and addresses how these are discursively reproduced, sustained or challenged by members of resident migrant communities in the two countries. Although the two countries bear similarities in their small size, extensive multilingualism and the pride of place accorded to the ‘small’ languages of Catalan and Luxembourgish respectively, they have adopted different strategies as regards according official status to the languages spoken there. We start by undertaking a close reading of language policy documents and highlight the ways that they are informed by ‘strategic ambiguity’, wherein certain key elements are deliberately left open to interpretation via a range of textual strategies. We then conduct a thematic analysis of individual speaker testimonies to understand how this strategic ambiguity impacts on the ways that speakers negotiate fluid multilingual practices while also having to navigate rigid monolingual regimes. In given contexts, these hierarchies privilege Catalan in Andorra and Luxembourgish in Luxembourg, particularly in relation to the regimentation of migrants' linguistic behaviour. In this way, the paper provides insights into the complex ideological fields in which small languages are situated and demonstrates the ways in which language policy is intertwined with issues of power and dominance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Andorra and Luxembourg are very small, Western European countries that are characterized by extensive individual and societal multilingualism. Each country finds itself surrounded by larger neighbours, whose official languages are widely spoken on a global level, and these adjacent ‘larger’ languages co-exist with the ‘smaller’ autochthonous languages of the two tiny states. Andorra is a country of just 468 km2 that straddles the border of France and Spain and, as such, the official language of Catalan has long coexisted with both French and Spanish. Luxembourg is only slightly bigger at 2586 km2, and is bordered by France, Germany and Belgium–therefore the national language of Luxembourgish is used alongside French and German. This situation is rendered even more complex by the fact that both Andorra and Luxembourg are popular destinations for migrants–around 47% of Luxembourg’s population is made up of resident foreigners (Statec, 2021), while in Andorra, this figure is roughly 51% (Govern d’Andorra, 2019a: 44). This has resulted in the increased presence of other languages, such as Portuguese and English, in addition to those already mentioned.

Despite these superficial similarities, the two countries have pursued different strategies when it comes to choosing and implementing official languages in their territories, due to a range of political, historical and ideological factors. In Andorra, Catalan has been declared the state’s official language, while in Luxembourg, French, German and Luxembourgish are all accorded different roles, and the term ‘official’ is avoided. How does this complex societal configuration of languages, large and small, officially declared or not, influence the lived experiences of residents of Andorra and Luxembourg, particularly those of a migrant background? How are governmental decisions regarding the officiality, role and status of different languages discursively reproduced, sustained or challenged by speakers on an individual level?

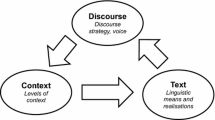

In line with Barakos and Unger’s (2016: 1) statement that “language policy is a multi-layered phenomenon that is constituted and enacted in and through discourse,” we adopt a discursive approach to the study of language policy, examining policy at the governmental level as well as drawing on individual speaker testimonies that demonstrate engagement with the issues under discussion. We will be focusing on the notion of ‘official’ languages and as such, start with a brief historical overview of scholarship that has addressed questions of language officiality. We will then undertake close readings of de jure officialization policies in Andorra and Luxembourg, paying particular attention to political, historical and ideological factors that shape these policies. These policy analyses will reveal some striking similarities, as well as important differences between the two countries–a common thread running through all these de jure policies will be the notion of ‘strategic ambiguity’, wherein certain key policy elements are deliberately left open to interpretation. In order to explore how language officialization policies are enacted or challenged discursively by migrants to Andorra and Luxembourg, we will undertake a thematic analysis of individual speaker testimonies. Drawing on the notion of ‘strategic ambiguity’, we will discuss how speakers navigate complex linguistic situations and hierarchies in their daily lives, before arriving at our conclusions.

Officiality in language policy: implications of discourse, ideology and ambiguity

Granting a language official status in a given territory is a frequently cited example of de jure language policy, and has been the focus of scholarly attention for decades. From the earliest works in the field of classic language planning (cf. Ricento, 2000: 206, for use of this term), a language’s officiality is expressed in terms of its legal status, and Kloss (1966: 143) contrasts languages with official status in a given territory with those that are merely tolerated or actively prohibited. Stewart (2012 [1968]), in a taxonomy of societal multilingualism, lists the first two potential functions of a language as official and provincial. Officiality is defined as ‘legally appropriate… for all politically and culturally representative purposes.’ (Stewart, 2012 [1968]: 540). For Stewart (2012 [1968]), the only difference between official and provincial languages is territorial, with the protections awarded to provincial languages being limited to smaller geographic areas. In a discussion of status planning, Cooper (1989: 100–104) develops Stewart’s taxonomy, distinguishing between languages declared as official by a government (statutory officiality), those which a government uses as the vehicle for its daily business (working officiality) and those which a government uses for symbolic purposes (symbolic officiality). While symbolic officiality draws on collective symbols to foster a sense of shared groupness, statutory officiality also is informed by the manipulation of collective symbols (such as identity and common memory) but with the goal of maintaining and perpetuating hegemonic power structures (Cooper, 1989: 102) and is the outcome of explicit status planning. Working officiality is sometimes the result of status planning, while symbolic officiality never is (Cooper, 1989: 103). Based on these early studies, we see two key themes emerge – rights and territoriality. What rights are granted to speakers of an official language, and in what jurisdictions and spaces do these rights apply?

Patten and Kymlicka (2003) frame the discussion of officiality in terms of speaker rights and access to services, while also noting that governments are more reticent to articulate situations of official state multilingualism as rights issues, instead preferring to view such decisions as simply ‘pragmatic accommodations’ (Patten & Kymlicka, 2003: 5). Different domains of official language usage raise a series of practical issues. For example, should governments be prescriptive about the languages used in internal communications, and what gatekeeping consequences does this entail for the hiring of public servants (Patten & Kymlicka, 2003: 17)? In dealing with the general public, how should official languages be interactionally enforced, and what are the consequences in terms of citizens’ access to necessary services (Patten & Kymlicka, 2003: 18)? Declarations of language officiality are shown to have both substantive and symbolic components. Substantively, according a language official status has consequences for speakers’ rights and abilities to use government services, while symbolically, a declaration of officiality can affect how a person identifies with a particular territory, depending on whether they are a member of the official language community or not (Patten & Kymlicka, 2003: 25). Importantly for the present study, Patten and Kymlicka (2003: 7) also address the issue of migrant communities’ engagement with processes of language officialization, highlighting that such groups are unlikely to demand official status for their own languages, instead it being ‘assumed that immigrants will learn the dominant language of their new country.’

Shohamy (2006: 59–63) reminds us that officialization, as a form of language legislation, is a political mechanism capable of turning ideologies into practice, through its ability to impose sanctions for linguistic infractions. As detailed above, language officiality can be used as an effective gatekeeping device, ensuring that certain linguistic communities or individual speakers of certain languages are granted rights, while others are denied those same rights. Through its promotion of homogeneous nation-states, language officiality functions as a propaganda tool, encouraging people to support notions of linguistically motivated group identity (Shohamy, 2006: 62). In order to understand language officiality, it is crucial to consider the bidirectional links between de jure officialization policies and the language ideologies underpinning them. What sorts of ideologies are invoked when a language becomes official in a given territory and how does this impact on linguistic practices?

Existing scholarship on language officiality has highlighted a number of key themes that will inform our approach to this study. Since officiality is primarily a means of granting or denying rights to speakers and language communities, what exactly are the rights in question and where do these reside–are they individual or territorial? De jure instances of language officialization policy in Andorra and Luxembourg will be analysed in order to consider the relationship between ideologies and linguistic practices. The focus on two small states that grant officiality to a small language serves as an instructive lens for exploring potential tensions between declarations of officiality and the implementation of policy. Close attention to language policy documentation will allow us to better understand how officiality is discursively constructed, sustained and challenged in relation to debates (cf. Blommaert, 1999: 8) surrounding these language policies which are marked by degrees of what we refer to as ‘strategic ambiguity’.

In the case of strategic ambiguity, certain key elements are deliberately left unspecified in policy texts and hence open to interpretation. It will be demonstrated how discursive strategies such as the explicit naming (or lack of naming) of languages and the foregrounding and backgrounding of information add a layer of ambiguity that impacts on the officiality of small languages. These strategies bear affinities to what Irvine and Gal (2000) refer to as semiotic processes, including iconisation and erasure. Indeed, the backgrounding of information and the absence of naming specific languages may be regarded as manifestations of (degrees of) erasure. As Pietikäinen et al., (2016: 41) point out, “small languages exist in cluttered fields of competing ideologies,” so it follows that the officiality of small languages is prone to elements of negotiation in de jure policy. While Grenoble and Whaley (2006: 15, after UNESCO, 2003) use the terms dominant and non-dominant (or threatened or endangered) language to highlight power asymmetries, the term small language underlines the non-binary circumstances in which Catalan and Luxembourgish are situated (cf. Pietikäinen et al., 2016: 3–9). The subsequent focus on testimonies from informants with a migration background will reveal how they engage with language officiality and strategic ambiguity in these small states, which in turn underlines the need for research to consider language policy both at the level of the state and in relation to the broader social and political field that transcends the state.

De Jure language policy in Andorra and Luxembourg

This section explores how officiality is discursively and materially embedded in de jure language policy in Andorra and Luxembourg, in addition to challenges inherent to the ongoing negotiation of these multifaceted policies and practices. We first examine how the exceptional officiality of small languages in these small states resonates with the deployment of strategic ambiguity in de jure language policy. We then discuss perceived threats that cast Catalan and Luxembourgish (as small languages) as endangered with close attention to the role of de jure language policy in constructing threats and/or responding to them. Perceived threats are connected to increasing levels of migration and societal multilingualism. This discussion provides a springboard to explore the ways in which officiality and strategic ambiguity impact on migrants’ experiences in the following section.

Officiality, strategic ambiguity and the exceptionalism of small languages

Various European treaties have determined the size and shape of Andorra and Luxembourg, with their respective trajectories as borderland zones impacting on language officiality in different ways. Luxembourg was declared an independent state following the Congress of Vienna in 1815 and its political borders have remained unchanged since the Treaty of London in 1839, when the Grand Duchy was partitioned and the western part ceded to the newly formed state of Belgium following from its break from the Kingdom of the Netherlands.Footnote 1 The Luxembourg constitution, adopted in 1848, was drawn up bilingually in German and French with the only de jure language policy statement in Article 2.30: ‘The usage of the French and German languages is optional. Such usage cannot be restricted’ (Journal officiel du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg 1848, our translation). The avoidance of explicit officiality and the dual orientation to German and French as written languages, with Luxembourgish being the unnamed yet widely spoken language, fulfilled various practical functions. At the same time, this policy fostered a nation-building orientation that demarcated Luxembourg from the one nation, one language ideology that informed policies in neighbouring Germany and France. In contrast with Luxembourg, the Andorran constitution was only ratified in 1993, after a long period of quasi-feudalism dating back to the late thirteenth century when the treaties known as the Pariatges d’Andorra set out its status as a feudal microstate.Footnote 2 The Andorran constitution stipulates de jure policy in monolingual terms by declaring in Article 2.1 that ‘the official state language is Catalan’ (Govern d’Andorra, 1993: 448, our translation), which in turn sets Andorra apart as the only country where Catalan is the sole official language. Regardless of official state monolingualism, Catalan has long co-existed with Spanish and French, but in spite of this, the use of other languages is partially erased, and the focus is on the small language of Catalan. The backgrounding of the key roles that Spanish and, to a lesser extent, French play in Andorra constitutes a form of strategic ambiguity that positions Catalan at the top of the linguistic hierarchy. In Luxembourg, the backgrounding of Luxembourgish in the 1848 constitution is rooted in its historical use mainly as a means of oral communication, with German and French fulfilling written key functions, thus impacting on elements of erasure and strategic ambiguity that inform more recent forms of de jure language policy and debates linked to officiality.

De jure language policy in Andorra contrasts with that in Luxembourg not only by granting Catalan statutory officiality but also by extensively elaborating on its usage in official contexts. The Andorran Llei d’ordenació de l’ús de la llengua oficial (‘Law establishing the usage of the official language’, henceforth Llei d’ordenació) was passed in 1999 in order to outline the domains of usage of Catalan as the ‘official state language’, while explicitly taking the multilingual context into account. Then, in 2005, these directives were developed into specific guidance on language usage in the public sector in a decree entitled Reglament d’ús de la llengua oficial en organismes públics (‘Rules of usage of the official language in public institutions’, henceforth Reglament d’ús). These two policy texts–the Llei d’ordenació and the Reglament d’ús–are focused on elucidating the nature of officiality as it pertains to the Catalan language in Andorra. In contrast, the ratification of the concisely worded 1984 language law in Luxembourg constitutes a move towards more explicit de jure language policy that provides Luxembourgish with symbolic recognition. However, this text largely avoids statutory officiality and designates the functions of Luxembourgish, German and French as administrative languages in Article 3, and French as the legislative language in Article 2. Article 1 declares that ‘the national language of the Luxembourgers is Luxembourgish’ (Journal officiel du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg, 1984). Although the law is written in French, Article 1 discursively constructs an iconic link between people who are ‘Luxembourgers’ and the Luxembourgish language, not only in terms of language use but also with regard to the symbolic role of the language in national group membership. In this way, the 1984 law also intersects with long-established state educational policies and practices that prioritise individual multilingualism of French and German alongside the use of Luxembourgish.

Thus, elements of strategic ambiguity embedded in Luxembourgish and Andorran declarations of officiality inform the ways that subsequent language policy documents are formulated. De jure language policy in Andorra foregrounds the statutory officiality of Catalan and elaborates its functionality as a working language in detail, while statutory officiality as well as the (relative absence of the) functionality of Luxembourgish as a (written) working language are backgrounded in Luxembourg. In a related vein, language policy in Luxembourg emphasises the importance of individual multilingualism, which is backgrounded, and sometimes even problematised, in Andorra. In both cases, there appear to be certain mismatches between statutory (declared), working (functional) and symbolic (groupness) officiality. However, residents need to navigate this state of affairs in their day-to-day linguistic practices. It may be argued that the particularism of Catalan and Luxembourgish, which are recognised as the official and national language in Andorra and Luxembourg respectively, is bound up with degrees of strategic ambiguity in de jure language policy. This strategy enables the recognition of small languages in contexts where individual multilingualism is a necessity for day to day operations. Nevertheless, these de jure policies constitute a delicate balance that is challenged by rapid forms of social, economic and demographic change.

Societal multilingualism, migration and endangerment discourses

Both countries are impacted by growing levels of societal multilingualism and major demographic shifts, with the 1999 law in Andorra and the 1984 law in Luxembourg as reactions to and as springboards for language(-related) policies and debates, including in particular those concerning linguistic (non-)dominance, power relations and endangerment. Societal multilingualism is foregrounded as a key motivating factor behind the creation of the 1999 Andorran Llei d’ordenació, as part of the document’s opening statement:

The geographical proximity to two widely spoken languages, the Andorran tradition of teaching in these two languages, the presence of mass media and, more recently, extensive immigration linked to the economic and societal growth seen in Andorra in the last decades: all of these factors have the potential to endanger the vitality of our language (Govern d’Andorra, 2000: 66, our translation from Catalan).

The Llei d’ordenació questions the pride of place of Catalan in Andorra, highlighting the international demographic importance and extensive influence of the other ‘widely spoken’ languages (even if these are not accorded the same legal protections as Catalan). Developing the officiality of a societally dominant language as a defence against perceived threats posed by non-dominant languages is nothing new (Shohamy, 2006: 62). However, this takes on new layers of complexity when the officially declared language of the state has lower ethnolinguistic vitality (cf. Giles et al., 1977)–at least on a global level–than other languages also used in the jurisdiction in question. As noted in the previous section, the policy document is informed by strategic ambiguity in that only Catalan is specified by name. Other languages used in Andorra are heavily alluded to through references to ‘geographical proximity’ (French and Spanish) and ‘extensive immigration’ (Spanish and Portuguese), but are not overtly named. Moreover, an iconic link is constructed between the Catalan language as ‘our language’ and in-group members of the Andorran nation-state, with speakers of ‘other’ languages positioned in the out-group.

In the above extract, it is discourses of threat and endangerment that are overt (Duchêne & Heller, 2007), due to Andorra’s unassuming position as a small state whose statutory official language has been subjected to minoritizing policies elsewhere. Such policies include decades of overt oppression and subjugation during Francisco Franco’s dictatorship in Spain from 1939 to 1975. The fact that the Llei d’ordenació only mentions Catalan by name suggests that the various ‘widely spoken’ languages used in Andorra are perceived to constitute different types of threat. French and Spanish are cast as threats by their geographical proximity, the size of their speech communities, and the popularity of mass media, as well as existing Andorran education policy decisions that had made these the chief languages of instruction.Footnote 3 The mention of immigration in recent decades indexes the increased presence of Spanish and Portuguese in the country–in 2018, 51.2% of Andorra’s population were not Andorran nationals (Govern d’Andorra, 2019a: 44), with over half of these people (37.1% of the total population) from Spain and Portugal. These ‘other’ languages are presented as potential threats to the survival of ‘our language’, i.e. Catalan, even though in 2018 only 45.9% of Andorra’s population claimed to identify with Catalan as their ‘own’ language (Govern d’Andorra, 2019b: 10).

Interestingly, it is not just societal multilingualism driving the need for greater official protections for Catalan in Andorra, but also individual speaker multilingualism:

The diversity of speakers of different languages; the role played by each linguistic group in society; the markedly tourist-related nature of [Andorra’s] wealth, and the interactions that result from this; and, above all, the fact that [Andorra’s] population can easily communicate in several languages. All of these reasons justify the need for more thorough legislation […] that provides people with the necessary tools in order to preserve Andorra’s linguistic identity (Govern d’Andorra, 2000: 66, our translation from Catalan and our emphasis).

Catalan speakers’ multilingual competence is highlighted as potentially detrimental to the status of Catalan in Andorra. State language policies may often disfavour multilingual practices in order to bolster the status of the official language. Such resistance to multilingualism could manifest as limited support for community or other minoritized languages, citing impracticality or financial concerns, as in de facto monolingual policies in the United States (Grenoble & Whaley, 2006: 30–31). However, it is rare for individual multilingualism to be targeted explicitly as harmful for the official language in a policy text, and this is linked to the specific Andorran context. Is Catalan in Andorra dominant, non-dominant or a mixture of both? On the one hand, Catalan is the sole official language of Andorra, and is the language of the dominant sector of society, namely the numerical minority of non-migrant Andorrans, who are accorded certain political rights and freedoms not given to migrant groups. Indeed, this segregation of roles between linguistic communities is alluded to in the above extract, with groups presented as playing different roles in Andorran society. On the other hand, Catalan is, generally speaking, a non-dominant language, given its co-existence with other, more demographically important languages, as well as historical and contemporary policies in other territories that have subjugated it to a position of reduced power. Given Andorra’s small size and population, granting Catalan sole official status in Andorra does little to offset this general picture of Catalan as an otherwise non-dominant language. Moreover, even within Andorra, the dominance of Catalan is questionable since this quality is linked to ‘social and economic opportunity’ (UNESCO, 2003: 9), and the utilitarian value of Catalan in Andorra, particularly for migrant workers, is far from clear.Footnote 4 In short, the Llei d’ordenació has to contend with a unique situation, in which Catalan dominance cannot be detached from its international context of non-dominance. The societal and individual multilingualism found in Andorra is to be treated very delicately, as this involves competence in languages that subjugate Catalan to a position of non-dominance in other territories.

Having adopted the stance that languages like Spanish and French may constitute a threat to Catalan, Andorran language policies seek to discourage or prevent multilingual practices in the official sphere by legislating what languages are to be used and in what contexts. Such practicalities were not made sufficiently clear in the Llei d’ordenació, hence the creation of the Reglament d’ús. For example, the requirement to use Catalan in Andorran government communications, be these internal or public facing, is specified in the Reglament d’ús. Article 5 states that public sector workers must use Catalan to address all those requiring assistance, regardless of whether those people are Andorran or whether they used Catalan in the interaction. Public sector workers may only use languages other than Catalan if the addressee makes it clear that they cannot understand Catalan. Article 5 also states that all oral conversations between public servants must take place in Catalan if these are on government property (Govern d’Andorra, 2005: 1248). These are examples of the official monolingualism policies pursued in order to establish Catalan’s status as dominant language in Andorra, which in turn echo Shohamy’s (2006: 60) discussion on the power of language laws to impose linguistic behaviours on people. As mentioned above, Catalan possesses a complex mixture of dominant and non-dominant qualities and, as such, Andorran language policy favours an approach where citizens’ multilingual repertoires are sidelined in favour of monolingual Catalan usage, and only drawn on in cases when communication would otherwise break down. The motivation behind this policy is presented as one of inclusivity – Andorra is thus an inclusive nation where all residents can be linguistically ‘integrated’ with Catalan as ‘our language’.

As is the case in Andorra, the ratification of de jure language policy coincides with increasing levels of societal multilingualism in Luxembourg. More specifically, the 1984 language law was ratified at a time of major demographic and socio-economic change, including a marked rise in the proportion of resident foreigners as well as accelerated cross-border working patterns by residents in Belgium, France and Germany. Societal multilingualism has become increasingly diversified and widespread, with French spoken more widely as a lingua franca among migrants and cross-border workers alike, thus raising concerns about the ethnolinguistic vitality and future of Luxembourgish. In this context, the potential dominance of Luxembourgish is questionable since its utilitarian value, particularly for migrant workers, is nebulous in many situations including the globalizing workplace. Shohamy (2006) underlines the importance of taking a holistic approach to language officiality by considering multiple policy mechanisms and diverse sites. Luxembourg contrasts with Andorra in that there is not extensive de jure language policy documentation. However, it is the case that language policy is extensively embedded in policies on citizenship, employment and education, with the interface between language and migration central to ongoing discussions and debates.

New forms of citizenship legislation were introduced in the early twenty-first century as a response to the rise in the resident foreigner population which was approaching the fifty percent mark. While this legislation entailed a relaxation of certain criteria (e.g. shortened residency requirements), the introduction of language requirements created new challenges and obstacles for applicants. More specifically, these requirements focused largely on demonstrating oral proficiency in Luxembourgish, thus echoing the iconic link between the Luxembourgish language and nationhood constructed in the text of the 1984 language law. In 2001, amendments to Article 7 of the law on Luxembourgish nationality stipulated language requirements for the first time in Luxembourgish history and replaced the term ‘assimilation’ by ‘integration’:

Naturalization will be refused to the foreigner [...] if he [sic] does not demonstrate sufficient integration, notably if he [sic] does not demonstrate sufficient active and passive knowledge of at least one of the languages stipulated by the language law of February 24 1984 and, if he [sic] does not have at least a basic knowledge of the Luxembourgish language, supported by certificates or official documents. (Journal officiel du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg, 2001, our translation from French)

In 2008, this legislation was elaborated by introducing testing regimes mapped onto CEFR levels (A2 for oral production/ B1 for listening comprehension in Luxembourgish). While the introduction of language tests for citizenship applicants resonated with policy in many other EU states (Extra et al., 2009; Hogan-Brun et al., 2009), the emphasis on aural/oral language testing in Luxembourg stands out. The discourse of integration has been central to the justification and implementation of these policies with Luxembourgish being strategically positioned as the key to integration for migrants, even if this claim also has been met with criticism in terms of whether such policies include or exclude migrants (Horner, 2015). In 2017, further changes were introduced to allow applicants the option of demonstrating proficiency via course participation rather than testing. There has been an increase in citizenship applications but the citizen/resident foreigner ratio is 53%/47% (Statec 2021). In this context, languages ‘other’ than Luxembourgish often are presented as potential threats, especially French, but discourses of endangerment are more prominent in popular discourse than official discourse. Thus, while de jure language policy documents do not foreground threats to Luxembourgish, endangerment discourses are prominent in other arenas and they inform other policies, particularly those on citizenship and education, which often erase the fact that Luxembourgish continues to be used as a primarily spoken rather than written language in formal and institutionalised contexts.Footnote 5

Grassroots activity concerning the promotion of Luxembourgish, in addition to related issues of dominance and endangerment, have had some impact on language policy in Luxembourg. The 2017 governmental white paper in response to a 2016 petition calling for Luxembourgish to be used as the main administrative language of the country constitutes a prime example. Receiving more signatures than any other petition in the history of the country, the timing of petition 698 followed a 2015 national referendum that included a question whether to allow resident foreigners to vote in national elections. It was turned down by an overwhelming majority of 78% Luxembourgish citizens, with some people voicing concerns about the vitality of Luxembourgish couched by discourses of endangerment that French could eventually displace the national language. Government efforts were ramped up to promote Luxembourgish and a 40-step policy was ratified in 2018. A key action was the creation of the Zenter fir d’Lëtzebuerger Sprooch (Centre for the Luxembourgish Language) to serve as an umbrella organization for the coordination of projects to promote Luxembourgish. At present, much of the work is focused on projects to normalize Luxembourgish, including the elaboration of the Luxembourgish Online Dictionary (LOD), the implementation of further minor orthographical reforms and the documentation of old vocabulary. While this legislation and related activity is centred on Luxembourgish, political statements continue to strike a balance between promoting Luxembourgish and emphasising the country’s historically entrenched multilingualism, as illustrated in Claude Meisch’s (Minister of Education, Childhood and Youth) prologue to a 2018 report concerning the promotion of Luxembourgish:

Multilingualism is one of the great opportunities but also challenges of Luxembourg […] The key element of this mix of languages is, and has always been, Luxembourgish–as the language of integration as well as a means of everyday communication (SCRIPT 2018: 2)

While Luxembourgish holds great symbolic value, the use of French and to a lesser extent German is central to the economic and social fabric of contemporary Luxembourg. Moreover, the use of all three languages is institutionalised in the state educational system with language-in-education policy demonstrating a historically entrenched pattern of privileging students who use Luxembourgish as a home language while also valorising prescribed patterns of individual multilingualism (see Weber, 2009; Weber & Horner, 2012; Muller, 2021). In this way, the relationship between what Grenoble and Whaley (2006: 15) refer to as dominant and non-dominant languages constitutes a delicate balancing act with no one language mapping out fully onto either category in all contexts.Footnote 6

In summary, language policy and officialization in Luxembourg and Andorra draw on elements of strategic ambiguity as a means of striking a linguistic balance. In both cases, this strategy enables the privileging of Luxembourgish and Catalan in officially designated spaces and contexts, while also allowing for the use of more widely-spoken languages in many other domains bound up with the globalizing economy. It is notable that requirements setting out the use of Luxembourgish and Catalan have been ratified in tandem with augmented levels of societal multilingualism and, in this way, are indirectly or directly informed by endangerment discourses. Given that these policies aim to regiment migrants’ linguistic behaviour, the following section explores how they discursively reproduce and/or challenge elements of state language policies on an individual level. How does strategic ambiguity in de jure language policy impact on the learning and use of small languages by migrants in highly multilingual contexts?

Migrants’ experiences and the consequences of strategic ambiguity

The superficial similarities between Andorra and Luxembourg are clear–their small size, their location in Western Europe, their historical contexts of societal trilingualism involving two ‘larger’ neighbouring languages, and the increased presence of migrant groups in recent decades. However, our examination of de jure instances of language officialization policy has highlighted an important common theme that gives rise to key differences between the two countries–namely, strategic ambiguity. Although both countries’ policies are characterized by a degree of strategic ambiguity–whereby certain languages are named or not, or recognised as official or not–this is used in different ways in each country. In Andorra, officiality is granted to the ‘smaller’ autochthonous language of Catalan, with other languages alluded to through references to ‘widely spoken languages’ (French and Spanish) and ‘extensive migration’ (Spanish and Portuguese), but not named. In Luxembourg, officiality has not been overtly granted to any language, though explicit mention of French and German was made in early documents; Luxembourgish has more recently been granted the status of ‘national’ language, analogous to the usage of ‘own’ language (‘llengua pròpia’) in surveys regarding language use in Andorra.

Given recent increases in migration to both countries, this section provides an analysis of speaker testimonies from participants with a migration background. The data is taken from semi-structured interviews conducted in Andorra and Luxembourg between autumn 2017 and spring 2019. Depending upon speakers’ linguistic repertoires, interviews were conducted in a range of languages by the authors of this paper (Luxembourgish, French and English in Luxembourg; Spanish, French, Catalan and Portuguese in Andorra). The interviews took place in informal social settings (cultural centres, cafés, etc.) and chiefly focused on topics related to multilingualism and mobility. We focus on speaker testimonies as a means of examining how the strategic ambiguity witnessed in language policy is discursively reproduced and challenged by residents of Andorra and Luxembourg, focusing on two key dimensions. The first examines speaker linguistic habitus in relation to individual rights and practices. The second considers governmental regimes of officiality that map out onto territorial rights and duties.

Linguistic habitus: navigating strategic ambiguity in de jure language policy

In this section, we address the issue of how strategic ambiguity witnessed in the de jure policy documents informs speakers’ linguistic habitus (Bourdieu, 1990: 53)– in other words, to what extent are people’s dispositions towards certain behaviour patterns reflective of the broader trends identified in official language policy? The following quote comes from Raquel,Footnote 7 daughter of two Portuguese migrants who was born in Andorra and now, in her early twenties, has returned to the country having undertaken university studies in France, and provides information about speaker linguistic habitus formationFootnote 8:

Extract 1: Although we’re in a country where Catalan is the official language, there’s a lot of freedom around language. I think people also understand that it’s a complicated situation because, yes, we’re in [our own] country, but we’re in between two [other] countries, we have to live among lots of immigrants, and so I think people understand the situation a bit. And besides, it’s not like we’re in a dictatorship where it’s like “No! You have to speak Catalan, whether you like it or not!” (our translation of the original Spanish).

There is a clear awareness of the status of Catalan as ‘official’ in Andorra, with this speaker (and other interviewees) using this word to describe the language. However, many factors are shown to bolster the status of the other languages – not named in the policy documents – used in the country. Andorra’s small size is juxtaposed against the larger neighbouring countries of France and Spain, and by synecdochic extension, the global status of Catalan as a ‘small’ language is contrasted with the ‘larger’ languages of French and Spanish. Moreover, Raquel acknowledges the increased presence of migrant groups, which in this case alludes to Portuguese, given her personal background and the level of usage of this language in Andorra. As such, official de jure state monolingualism is (more accurately) recast as a situation of de facto societal multilingualism. But how is the strategic ambiguity within Andorran de jure officialization policy seen to influence speakers’ linguistic habitus? Speakers’ dispositions towards linguistic behaviours are not static and are constantly re-evaluated according to the fluctuating values attached to language practices in their relevant domain-specific contexts – in Bourdieusian terms, the habitus is dynamic and derives from rules of price formation in the linguistic market (Bourdieu, 1993). The linguistic market in which Andorra finds itself is complex and transnational and, as a small country, the rules of price formation are intrinsically bound to its relationship with its larger neighbours and, naturally, their languages. Despite official Catalan monolingualism, Andorra’s diminutive size and strong historical ties to France and Spain mean that utilitarian value is still attached to multilingual language practices in French and Spanish. The strategic ambiguity in the de jure policy allows for Catalan to take its place at the top of the linguistic hierarchy, and by implication, relegates the other unnamed languages to inferior positions. However, this is offset by the value ascribed to these ‘unnamed’ languages (French, Spanish and even Portuguese) by the rules of price formation in the linguistic market operating in Andorra, which gives importance to multilingualism, influenced as it is by the importance of the country’s two larger neighbours. The result is the compromise seen in Raquel’s testimony where Catalan is acknowledged as ‘official’, but the reality on the ground is far more flexible.

As we saw in the previous section, strategic ambiguity takes a different form but is nonetheless present in language officialization policies enacted in Luxembourg. The following extract comes from Nadine, who arrived in Luxembourg from Cabo Verde as a child and is now in her forties. Here, she discusses language use in her workplace at a school:

Extract 2: Yes, well it is really that French is for writing and if you really want to make it more official, I always do it like that. If I’m now going to send a message to the entire staff, something official, an announcement or, some kind of whatever, a memo [note de service, quoted in French], then I do that in French. But if I’m now going to write to a teacher or three members of a department, then I can do that, then I write that in Luxembourgish. That is funny. […] If it is quite formal, they send everything, please find attached [quoted in French], a letter from the Minister or something like that. That is all in French. But then someone who writes something to me personally, ‘the contract is ready’ or something, then that is in Luxembourgish, that is always a bit like that […] Official French, but more relaxed Luxembourgish (our translation of the original Luxembourgish).

In this quote, Nadine is discussing written means of communication and uses the term ‘official’ to refer to French, in contrast to the more ‘relaxed’ domains reserved for Luxembourgish. This dichotomy between official and relaxed domains is then mapped onto public and private written communication within professional settings; a distinction is drawn between the language appropriate for ‘the entire staff’ (French) and the language used for ‘three members of a department’ (Luxembourgish), even if both interactions occur in the same professional domain. The formality indexed by the usage of French even triggers a change in footing (Goffman, 1979) from Nadine, in which she switches from Luxembourgish to French for the formulaic ‘veuillez trouver en annexe’ (‘please find attached’), reproducing the elements of her linguistic repertoire that she associates with formal interactions in professional contexts. It should be noted that these processes seem to operate below the level of conscious awareness, as revealed by her pausing and reflecting ‘that is funny’. Again, this begs the question of how the strategic ambiguity present in Luxembourgish de jure officialization policy affects speakers’ linguistic habitus. The 1984 language law places Luxembourgish, French and German in an equal position as ‘administrative languages’. In the same legislation, Luxembourgish is granted the distinction of ‘national language of the Luxembourgers’ while French is given the high-domain privilege of ‘legislative language’. This same dynamic–in which Luxembourgish fulfils the role of everyday communication and French assumes high-level functions–is clearly echoed in Nadine’s testimony above. As always, speaker dispositions towards certain language usage patterns are dictated by the rules of price formation in the linguistic market and, like Andorra, Luxembourg finds itself in a highly complex transnational marketplace in which value is derived from the relationship of this small multilingual country with its larger neighbours. The position of French as a high-domain language is thus consolidated, with Luxembourgish reserved for less formal, interpersonal domains. Recent political discourse reflects Luxembourgers’ linguistic habitus in this respect. Meisch’s prologue to the 2018 report (quoted in the previous section and contemporaneous with our speaker testimonies) centres Luxembourgish as the linchpin of multilingualism in the country, valuing it as a ‘means of everyday communication’ and ‘the language of integration’. However, Luxembourgish is still not granted ‘official’ status, either solely or in conjunction with French and German, which allows French to assume the position of de facto ‘official’ language in certain domains (seen in Nadine’s testimony). There are thus similarities between current Luxembourgish language policy on the macro-level (the Meisch report) and the individual speaker habitus level (Nadine’s testimony).

Clear alignment is seen between speakers’ linguistic habitus and the strategic ambiguity present in de jure language officialization policies in Andorra and Luxembourg. Our findings echo Moraru (2019: 93), according to whom “the linguistic habitus of the second-generation [migrants] adapts to the rules and laws of price formation of the new linguistic market; however, these new rules are internalized only by building on the previous states of the linguistic habitus.” Raquel (a second-generation migrant) and Nadine (1.5-generation) have fashioned their linguistic habitus by combining their home experiences (as children of migrants) with the complex rules of price formation in small multilingual states that are heavily influenced by languages spoken in the larger neighbouring countries.

Officiality regimes: non-negotiable spaces of small language dominance

This section addresses an application of language policy texts which, despite being contingent on strategic ambiguity, is more explicit in its stipulation that specific languages must be used in certain contexts. An important difference between the two countries relates to ‘smaller’ languages as keys to citizenship and integration. In Luxembourg, the requirement of prospective citizens to demonstrate a degree of aural and oral competence in Luxembourgish reinforces the ‘national’ nature of the language. In Andorra, this angle is largely absent from discourses of officiality since active participation in Andorran society is arguably less predicated on citizenship.Footnote 9 Thus, in addition to considering speaker linguistic habitus, we also explore how institutional officiality regimes impact on speakers’ multilingual experiences in Andorra and Luxembourg. We draw on Costa’s (2019: 2) critical discussion of language regimes and definition of the concept of regime, which resonates with a Bourdieusian approach to legitimate language, as constituting “a spatial and temporal set of practices, either physical or symbolic, through which rules are established to determine an inside and an outside, and in which not anyone is allowed to participate or seen as legitimate.” Thus, regimes constitute an interesting lens through which to examine scenarios where one language, Catalan or Luxembourgish, is prioritized in certain contexts despite language policy in Andorra and Luxembourg being contingent on elements of strategic ambiguity in other contexts.

What follows are speakers’ testimonies on language choices and scenarios that are quite rigid as opposed to the more negotiable ones discussed above. We wish to address the issue of how strategic ambiguity witnessed in the de jure policy documents nevertheless exists in parallel to officiality regimes and examine what people’s views are on this state of affairs. The following quote comes from Gustavo, a first-generation Portuguese migrant who came to Andorra at the age of twenty and now, at nearly thirty, runs a small business:

Extract 3:

G: I use Spanish, almost always Spanish. Even with Portuguese people, even with Portuguese friends and everything, even with my cousin, I tend to speak in Spanish… it’s natural. I do use Catalan, I can speak Catalan, but writing is harder. I can speak it, I understand it perfectly, but since I don’t practise it every day…

J: When do you try to use Catalan?

G: It’s more when I go, when I go to the immigration office, when I go to government buildings, because they DO only speak in Catalan to you. It’s rare that they would speak to you in any other language. And when I go to the doctor, the doctor speaks to me in Spanish. Straight away, I speak in Spanish with the doctor. It’s just easier to express yourself. You’re used to the words and it’s much easier to express yourself. And you’re used to it. Now, in Catalan, only… only in, well, the government, immigration… places where they only speak in Catalan to you straight away (our translation of the original Portuguese).

The officiality of Catalan in Andorra is rooted in expectations of its usage in government offices ‘because they DO only speak in Catalan to you’. These spaces are governed by explicit language policy and rooted in power dynamics that shape who is considered to be on the inside and who is on the outside. The de jure status of Catalan as ‘official’ in Andorra is not mentioned here but its link with institutional settings underlines its officiality. At the same time, Gustavo describes how he uses Spanish in many other settings, including the doctor’s office, and how Spanish is widely spoken in everyday life in line with its value in the broader linguistic market. It is notable that migrants are required to linguistically adapt in certain settings such as the immigration office. Although this rigidity of the linguistic playing field differs from those illustrated in Extracts 1 and 2, the pride of place of Catalan in specific spaces as illustrated in Extract 3 is taken for granted by Gustavo, who has lived in Andorra for nearly a decade. There is alignment between his linguistic habitus and the de jure language officialization policy as well as the navigation of linguistic practices in various spaces in Andorra. The explicit de jure policy positions Catalan at the top of the linguistic hierarchy, and by implication, relegates the other unnamed languages to inferior positions in these specific institutional settings. As was the case with Raquel, the prioritization of Catalan is partially offset by the value ascribed to the ‘unnamed’ language of Spanish in the linguistic market of Andorra, where Spanish functions as a widely used lingua franca in line with historical links to this bordering country as well as contemporary cross-border mobility patterns. The result is that Catalan is linked to officiality regimes in governmental settings; however, the reality of everyday life entails much more flexibility in line with Gustavo’s description of the widespread use of Spanish as being ‘natural’, which in turn resonates with elements of strategic ambiguity.

As noted previously, strategic ambiguity takes a different form but is nonetheless present in language officialization policies enacted in Luxembourg. The following extract comes from Kathy, who was born in the United States and arrived in Luxembourg five years ago, after having lived in France for many years, and now is in her late forties:

Extract 4: I mean there is power in language and I understand why people are putting energy and effort in language to AFFECT culture, but in Luxembourg it feels a little bit defensive, it feels like a defensive mechanism […] I understand if you want to become a citizen you should speak A language and so if Luxembourgish is THE official language, I get it. At the same time like, you know, Luxembourgish is literally only spoken here, so for someone like me who's fluent in French, I'm building up my motivation to learn Luxembourgish, and I'll start in September. But it's harder to build up motivation to learn a language that is spoken in such a limited quantity, you know (original quote in English).

Kathy questions the officiality of Luxembourgish due to her experience of it being ‘spoken in such a limited quantity’ and ‘only spoken here’. These considerations appear to operate above the level of conscious awareness, underlined by her reflections on certain ambiguities in the de jure language policy by stating ‘if Luxembourgish is THE official language I get it’. This raises the question of how the strategic ambiguity present in Luxembourgish de jure officialization policy meshes with officiality regimes which, in line with Costa (2019: 4), “exist only through the continuous process of regimentation: they are the continuous production of particular social orders through everyday actions, acting through the continuous reproduction of naturalising or contesting ideologies, and drawing on as well as defining what counts as a resource.” While the 1984 language law declares Luxembourgish as the ‘national language of the Luxembourgers’, French is designated as the ‘legislative language’ and as a result generally serves as the default language of administration of the state. While the latter pattern of language use is familiar to Kathy, the former does not pertain to Kathy’s experience because French rather than Luxembourgish fulfils the role of everyday communication. Indeed, the global status of Luxembourgish as a ‘small’ language is contrasted with the ‘larger’ language of French, as Kathy notes that Luxembourgish ‘is only spoken here’. The small size of Luxembourg, in addition to governmental decisions to prioritize French in the post WWII period and more recent forms of cross-border mobility, mean that utilitarian value is still attached to multilingual language practices in French and to a lesser degree German. Unlike in the case of Nadine who grew up in Luxembourg, there are thus divergences between current Luxembourgish language policy on the macro-level (Meisch’s prologue to the 2018 report) and the individual speaker habitus level in Kathy’s testimony. So, this example illustrates how strategic ambiguity present in Luxembourgish de jure officialization policy does not always resonate with certain speakers’ linguistic habitus, notably in the case of a more recently arrived migrant.

In summary, we have seen how Catalan and Luxembourgish are positioned at the top of the linguistic hierarchy in specific institutionalized settings (government offices) and contexts (citizenship requirements) and by implication, how officiality regimes relegate the other languages to inferior positions in those instances. However, these official de jure state monolingual policies stand in contradiction with widely practiced de facto societal multilingualism. It can be argued that small states rely on elements of strategic ambiguity with regard to language officiality and all the more so when small languages fulfil the role of symbolic officiality (cf. Stewart, 2012 [1968]). This state of affairs creates a complex situation to which migrants need to adapt. Whereas certain contexts allow for linguistic practices to be negotiated, there are others where linguistic practices are more highly regimented, which notably are scenarios that entail the regimentation of migrants’ linguistic behaviour and impact on their rights and duties.

Conclusions

Strategic ambiguity has been shown to be characteristic of de jure language policies regulating small languages in small states, and we have witnessed how notions of officiality are discursively reproduced, upheld or challenged by social actors in Andorra and Luxembourg. Such a form of ambiguity opens up the possibility for different interpretations of the policy documents, which in turn allows for the development of flexible multilingual price formation rules that govern the transnational linguistic marketplaces in which these small countries are situated. In other words, it shapes the negotiation of multilingual practices in these spaces and informs speakers’ linguistic habitus. The analysis further suggests that small states rely on strategic ambiguity when the autochthonous small language fulfils functions of symbolic officiality, as seen in both Andorra and Luxembourg. Specifically for migrants in these small states, engagement with the small language is contingent on the ways in which officiality regimes impact on their lives–different people may be able to negotiate their interaction with governmental organisations and official requirements to different degrees, depending on their social standing, length of residency, etc. Strategic ambiguity in de jure policy documents allows for these varying degrees of impact of officiality regimes.

We hope that future work will further explore the mechanisms of strategic ambiguity, and how it plays a decisive role in the construction of social order, obliging some people to partake in rigid monolingual hierarchies, while affording others the chance to opt out. Indeed, we have seen that linguistic hierarchies engendered by officiality regimes can pose a particular problem for migrants with low levels of competence in or even lack of access to the ‘smaller’ language (here, Catalan or Luxembourgish). People may nonetheless be obliged to engage with these hierarchies, not possessing the resources to be able to opt out, and may then question the validity of such officiality regimes, and even be unable to fully participate in social life or access certain rights in their new home country. We can therefore see that small multilingual states like Andorra and Luxembourg constitute fruitful sites to explore the interface between governmental language policy, speaker ideologies, and issues of migration and mobility.

Notes

Until 1982, the French and Spanish education systems operated exclusively in Andorra. This changed with the introduction of the Andorran education system, which lists as one of its principal aims to ‘ensure the use of Catalan in different communicative settings through spreading knowledge of its range of registers’ (Govern d’Andorra, n.d., our translation from Catalan).

The value of small languages as tools of socioeconomic mobility for migrant groups will be discussed at greater length in Hawkey and Horner (forthcoming).

These discourses frequently evoke the period of Nazi German occupation (1940–1944/5), a focal moment in collective memory, when German was imposed as the sole official language and Luxembourgish was declared a dialect of German (see Horner and Wagner 2012).

At the time of editing (30 July 2021), a public petition (number 1946) opened, requesting that citizenship applicants be permitted to have the choice of demonstrating proficiency in French or German, rather than having to do so in Luxembourgish. A core premise of the petition is that ‘Luxembourg recognises 3 official languages.’.

All names used in the article are pseudonyms.

Given the limited range of courses offered at the University of Andorra, many young Andorrans go to either Toulouse or Barcelona (the two nearest big cities) to study degree programmes.

In order to acquire Andorran nationality, a migrant would need to have had their primary residence in the country for at least twenty years (if arriving after the completion of compulsory education) and to give up all other nationalities. This frequently entails relinquishing EU membership, since Andorra is not a member state. Luxembourg, on the other hand, only has a five-year residency requirement, is a full EU member state, and opened the path to enable dual nationality in 2008. The barriers to acquiring Andorran nationality do not necessarily make it an appealing or feasible prospect for migrants, and issues of language and citizenship do not take the same prominence as in Luxembourg.

References

Barakos, E., & Unger, J. W. (2016). Introduction: Why are discursive approaches to language policy necessary? In E. Barakos & J. W. Unger (Eds.), Discursive approaches to language policy (pp. 1–9). Palgrave Macmillan.

Blommaert, J. (1999). The debate is open. In J. Blommaert (Ed.), Language ideological debates (pp. 1–38). Mouton de Gruyter.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). The Logic of Practice (translated by R. Nice). Oxford: Polity.

Bourdieu, P. (1993). Sociology in question. Sage.

Calmes, C., & Bossaert, D. (1996). Geschichte des Großherzogtums Luxemburg: von 1815 bis heute. Luxemburg: Editions Saint-Paul.

Cooper, R. L. (1989). Language planning and social change. CUP.

Costa, J. (2019). Introduction: Regimes of language and the social, hierarchized organization of ideologies. Language and Communication, 66, 1–5.

Duchêne, A., & Heller, M. (Eds.). (2007). Discourses of endangerment: Ideology and interest in the defence of languages. Continuum.

Emerson, M. (2007). Andorra and the European Union. Centre for European Policy Studies.

Extra, G., Spotti, M., & van Avermaet, P. (Eds.). (2009). Language testing, migration and citizenship: Cross-National perspectives on integration regimes. Continuum.

Giles, H., Bourhis, R. Y., & Taylor, D. M. (1977). Towards a theory of language in ethnic group relations. In H. Giles (Ed.), Language, ethnicity and intergroup relations (pp. 307–348). Academic Press.

Goffman, E. (1979). Footing. Semiotica, 25(1/2), 1–30.

Govern d'Andorra (1993). Constitució del Principat d’Andorra. Butlletí Oficial del Principat d’Andorra, 5(24), 448–458.

Govern d'Andorra (2000). Llei d’ordenació de l’ús de la llengua oficial. Butlletí Oficial del Principat d’Andorra, 12(2), 66–72.

Govern d'Andorra. (2005). Decret d’aprovació de la modificació del Reglament d’ús de la llengua official en organismes públics. Butlletí Oficial del Principat d'Andorra, 17(28), 1246–1252.

Govern d’Andorra. (2019a). Andorra en xifres 2019. Andorra: Govern d’Andorra.

Govern d’Andorra. (2019b). Coneixements i usos lingüístics de la población d’Andorra. Situació actual i evolució (1995–2018). Andorra: Govern d’Andorra.

Govern d’Andorra. (n.d.) Sistema Educatiu Andorrà. Retrieved 25th May 2021 from https://www.educacio.ad/sistema-educatiu-andorra

Grenoble, L. A., & Whaley, L. J. (2006). Saving Languages: An introduction to language revitalization. CUP.

Hawkey, J. & Horner, K. (forthcoming). Multilingualism, Mobility and Small States: The Sociolinguistics of Migration in Andorra and Luxembourg (provisional title).

Hogan-Brun, G., Mar-Molinero, C., & Stevenson, P. (Eds.). (2009). Discourses on language and integration: Critical perspectives on language testing regimes in Europe. John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Horner, K. (2015). Language regimes and acts of citizenship in multilingual Luxembourg. Journal of Language and Politics, 14(3), 359–381.

Horner, K., & Wagner, M. (2012). Remembering World War II and legitimating Luxembourgish as the national language: Consensus or conflict? In N. Langer, S. Davies, & W. Vandenbussche (Eds.), Language and history, linguistics and historiography (pp. 447–464). Peter Lang.

Irvine, J., & Gal, S. (2000). Language ideology and linguistic differentiation. In P. V. Kroskrity (Ed.), Regimes of language: Ideologies, polities and identities (pp. 35–84). School of American Research Press.

Journal officiel du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg. (1848). Constitution du 9 juillet 1848 du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg, Mémorial A52. Luxembourg: http://legilux.public.lu/

Journal officiel du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg. (1984). Loi du 24 février 1984 sur le régime des langues, Mémorial A16. Luxembourg: http://legilux.public.lu/

Journal officiel du Grand-Duché de Luxembourg. (2001). Loi du 24 juillet 2001 portant modification de la loi du 22 février 1968 sur la nationalité luxembourgeoise, telle qu'elle a été modifiée, Mémorial A101. Luxembourg: http://legilux.public.lu

Klieger, P. C. (2013). The microstates of Europe: Designer nations in a post-modern world. Lexington Books.

Kloss, H. (1966). Types of multilingual communities: A discussion of ten variables. Sociological Inquiry, 36(2), 7–17.

Moraru, M. (2019). Toward a Bourdieusian theory of multilingualism. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 17(2), 79–100.

Muller, S. (2021). The Lived Experience of Language (Education Policy): Multimodal Accounts by Primary School Children in Luxembourg. PhD Thesis: University of Sheffield.

Patten, A. & Kymlicka, W. (2003). Introduction: Language rights and political theory: Context, issues and approaches. In W. Kymlicka & A. Patten (Eds.), Language Rights and Political Theory (pp. 1–51). Oxford: OUP.

Péporté, P., Kmec, S., Majerus, B. & Margue, M. (2010). Inventing Luxembourg: Representations of the Past, Space and Language from the Nineteenth to the Twenty-First Century. Leiden: Brill.

Pietikäinen, S., Kelly-Holmes, H., Jaffe, A., & Coupland, N. (2016). Sociolinguistics from the periphery: Small languages in new circumstances. Cambridge University Press.

Ricento, T. (2000). Historical and theoretical perspectives in language policy and planning. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 4, 196–213.

SCRIPT (Service de Coordination de la Recherche et de l’Innovation Pédagogiques et Technologiques). (2018). Zesummen d’Lëtzebuerger Sprooch Fërderen. Luxembourg: Ministère de l’Éducation nationale, de l’Enfance et de la Jeunesse.

Shohamy, E. (2006). Language Policy: Hidden Agendas and New Approaches. Routledge.

Spizzo, D. (1995). La nation luxembourgeoise: Genèse et structure d’une identité. L’Harmattan.

Statec. (2021). Le Portail des Statistiques – Grand Duché de Luxembourg. Retrieved 11th May 2021 from https://statistiques.public.lu/fr/index.html

Stewart, W. A. (2012). A sociolinguistic typology for describing national multilingualism. In J. A. Fishman (Ed.), Readings in the sociology of language. The Hague: Mouton.

UNESCO. (2003). Language Vitality and Endangerment. Retrieved 12th February 2021 from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000183699.

Villaró, A. (2011). New Description of the Principality and Valleys of Andorra. Andorra: Editorial Andorra.

Weber, J.-J. (2009). Multilingualism, education and change. Peter Lang.

Weber, J.-J., & Horner, K. (2012). The trilingual Luxembourgish school system in historical perspective: Progress or regress? Language, Culture and Curriculum, 25(1), 3–15.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Sarah Muller and Katiuska Ferrer Portillo for transcribing the interviews and for their work as members of the research project. Also, thanks to Sarah for reading a draft of this article and providing great feedback.

Funding

This research was supported by the British Academy’s Tackling the UK’s International Challenges initiative (reference: IC160082).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hawkey, J., Horner, K. Officiality and strategic ambiguity in language policy: exploring migrant experiences in Andorra and Luxembourg. Lang Policy 21, 195–215 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-021-09602-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-021-09602-3