Abstract

Context

Global warming has been exerting an increasing stress on mammal populations occurring at the bioclimatic edges of their ranges. Moose, as heat-sensitive ungulates, are expected to be increasingly susceptible to thermal stress; however, the behavioral responses of animals could mitigate unfavorable weather conditions.

Objectives

We aimed to evaluate the temperature-mediated behavioral changes in moose occurring at the southwestern edge of the species’ range in Europe. We predicted that increasing temperature in summer would modify the daily activity pattern of animal and fine-scale utilization of thermal cover.

Methods

We analysed data from 36 moose, who were fitted with GPS collars from two study sites located in Eastern Poland. The distance between moose locations served for assessing moose activity. We applied additive modelling to test the effect of the daily temperature on daily activity patterns and landscape use of moose.

Results

Moose, when exposed to temperatures exceeding thermal comfort, increased their activity during cooler twilight hours. On the hottest days, moose were more likely to use tree canopy cover, especially during midday hours. Finally, with increased temperatures and the risk of thermal stress, at that part of the day, moose utilized denser forest stands which could have provided extra protection against solar radiation.

Conclusions

Our observations suggested that under a scenario of further climate warming, moose at the southwestern periphery of their range will be forced to make further behavioral alterations. However, it is not clear whether they will be able to compensate for the negative effects of on-going climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Global warming causes large-scale changes in ecosystem composition and functioning. The highest rate of change has been projected for the high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere, where increasing temperatures are supposed to drive the shift of northern animal and plant ranges; they are predicted to move northward, while in mountainous regions an upward shift is anticipated (Parmesan and Yohe 2003; Root et al. 2003; Walther 2004; Chen et al. 2011). Therefore, the negative effects of climate change will be most pronounced in populations occurring at the bioclimatic edges of their ranges (Lawton 1993; Vucetich and Waite 2003; Hampe and Petit 2005). Elevated temperatures are expected to influence animals both directly through increased thermoregulatory costs exerted by higher needs for heat dissipation and indirectly via unfavorable changes in forage quality and quantity. Yet, animals can counteract adverse temperatures through behavioral changes and optimized patterns of their daily activity and habitat selection (Belovsky 1981; Kie 1999). Many large herbivores avoid heat stress by decreasing activity and selecting less optimal habitats in terms of foraging, but instead, provide efficient shelter against solar radiation during the hottest time of the day (e.g. Mule deer Odocoileus hemionus: Sargeant et al. 1994; Alpine ibex Capra ibex: Aublet et al. 2009; Mason et al. 2017; black wildebeest Connochaetes gnou: Maloney et al. 2005; moose Alces alces: Ditmer et al. 2018). Nonetheless, prolonged exposure of animals to extreme temperatures in summer could make such behavioral modifications insufficient with regard to facilitating thermoregulation. The accompaniment of thermal stress together with utilization of less profitable foraging habitats, could have a negative influence on the animals’ fitness components, resulting in reduced fecundity and survival, leading to population density decrease and distribution shift (Lenarz et al. 2009; Speakman and Król 2010; Monteith et al. 2015; Hoy et al. 2018).

Moose is a boreal species whose current range is limited by temperature to northern parts of Eurasia and North America (Geist 1987; Karns 1997). Moose lose heat predominantly through respiration and conduction, since the species are unable to dissipate heat via the mechanism of sweating. As a large bodied mammal with a low surface-to-volume ratio, moose have a lower rate of heat exchange compared with smaller species, that drives delayed response and decreased tolerance to temperature changes (Kingsolver and Huey 2008; Gardner et al. 2011). This makes the moose an ideal model species for surveys targeted at tracing the effects of increasing temperatures on behavioral changes and their translation into individual fitness traits (Demarchi and Bunnell 1993; Brown 2011; Broders et al. 2012; van Beest et al. 2012). According to Renecker and Hudson (1986), the thermal stress in moose occurs when individuals are exposed to temperatures exceeding 14 ºC in summer and − 5 ºC in winter, while McCann et al. (2013) provided higher summer heat-stress thresholds, i.e. 17 ºC under calm conditions and 24 ºC on windy days. Above those limits, moose started panting, indicating greater thermoregulatory costs due to accelerated respiration and elevated oxygen consumption (Renecker and Hudson 1986). Free-ranging moose responded to the heat-imposed stress by adjusting their behavior. Under elevated temperatures above thermal comfort, moose decreased their activity and, when available, selected thermal shelters under canopy cover, where mean temperatures can be on average 2–3 ºC cooler, compared with open habitats (Lowe et al. 2010; van Beest et al. 2012; Broders et al. 2012).

In Europe, previous studies on thermal stress in moose have been conducted on populations inhabiting the northern latitudes (Scandinavia and Fennoscandia) which indicated that moose escaped elevated temperatures by hiding under canopy cover and selecting high and dense forest stands (van Beest et al. 2012; Melin et al. 2014). Yet, there appears to be little information about the effect of increasing temperatures on the daily pattern of moose activity. This study aimed to bridge this gap. The study area was located in NE Poland, where moose inhabit the southwestern edge of the species distribution and have been exposed to more extreme warmth throughout the year, compared with Scandinavian populations. In our paper, we assessed the effect of maximum daily temperatures on activity and habitat use of GPS-collared moose from two refugial areas for the species in Poland.

We hypothesized that temperatures above the critical threshold, which increase the risk of thermal stress, would cause behavioral responses in moose with regard to changed daily activity patterns and increased utilization of canopy cover. We predicted that elevated temperatures would cause longer periods of increased activity during cooler hours of the day to compensate thermoregulatory costs connected with heat dissipation during the hottest midday hours. Finally, we predicted that moose, when utilizing canopy cover, would search for denser cover providing more efficient protection against solar radiation.

Methods

Study area and sites

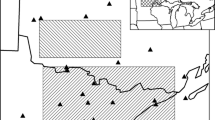

Our study area was located in NE Poland, at the southwestern edge of the species European distribution (Fig. 1). It covered two refugial areas, with the most viable moose populations in Poland (Gębczyńska and Raczyński 2004). The northern study site (22º 35′ E, 53º 26′ N) encompassed the southern part of Biebrza National Park and the adjacent forest districts. The southern study site (23º 8′ E, 51º 26′ N) nestled in the Polesie National Park with surrounding forest districts. The southern part of Biebrza NP comprises the largest marshland valley in Central Europe (12–15 km wide) that spreads longitudinally over a distance of 30 km. The majority of Biebrza valley covers peats (1–2 m thick), while the outskirts are dominated by dunes overgrown with coniferous forests (Żurek 2005). Polesie NP is a plain, with a high diversity of wetland and forest habitats, which are interwoven with numerous oligotrophic lakes, with varying accumulations of organic material (Gazda 2005; Harasimiuk 2009). In both study sites, vegetation in open wetlands constituted variable sedge, sedge-moss, and reed communities. Large parts of wetlands are overgrown with dense willow bushes. Forest habitats are dominated by pine (Pinus sylvestris), black alder (Alnus glutinosa) and downy birch (Betula pubescens) (Bartoszuk 2005; Piasecki 2005; Urban 2005). Both study sites are inhabited by four ungulate species: moose, red deer (Cervus elaphus), roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), and wild boar (Sus scrofa; Wawrzyniak et al. 2010; Borowik et al. 2013) and their predator wolf (Canis lupus; Jędrzejewski et al. 2012).

The climate in the study area is transitional between Atlantic and continental types. Growing season lasts ca. 200 days, on average. Snow cover lingers up to 110–120 days. Mean maximum snow cover is 25–30 cm. The warmest month is July (Biebrza study site: mean = 18.4 ºC, range: 2.1–33.7 ºC; Polesie study site: mean = 19.7 ºC, range: 7.5–34.1 ºC), whilst the coldest is January (Biebrza study site: mean = − 3.9 ºC, range: − 23.3–8.1 ºC; Polesie study site: mean = − 2.9 ºC, range: − 21.5–10.9 ºC). Annual precipitation is about 550 mm and summer rains represented 40% of the annual precipitation. (Kaszewski 2005).

Data collection and analyses

Our dataset comprised summer (June 1–August 31) locations of GPS collared adult moose in Biebrza NP – 24 moose (13 females and 11 males) and in Polesie NP – 12 individuals (10 females and 2 males) in 2012–2016 (Borowik et al. 2018, 2020). Out of all positions, we chose only fixes registered at 1 h intervals that led to a final database of 139,948 fixes in Biebrza NP and 32,652 positions in Polesie NP. We analysed moose activity as a categorical variable (non-active = 0, active = 1). This classification was done on the basis of moose step length (distance between two consecutive positions). We assessed the location errors of four GPS collars set stationary in the field conditions and found that most of them (86%) were not greater than 50 m (Fig. S1). Thus, we used this value as a threshold in activity classification: we assumed moose to be non-active when the step length was below 50 m and active for step lengths above 50 m. Then, we intersected all positions with a high resolution layer (20 m) of Tree Cover Density (TCD) 2015 from the Copernicus observation system, providing level of tree cover density in a range from 0 to 100% for the 2015 reference year (Re3data.Org 2019). Next, we classified locations into two categories: within and outside the canopy cover (tree cover density above and equaling zero, respectively). Finally, for all the locations classified as under canopy cover, we attributed the canopy cover density, which ranged from 8 to 100% (Fig. 1). For both study sites, maximum daily temperatures were derived from the weather stations located within sites collected by the Institute of Meteorology and Water Management, National Research Institute, Poland.

To identify whether the maximum temperature had an influence on the probability of moose activity throughout the day in summer, we fitted generalized additive model (GAM) with binomial error structure in the mgcv package implemented in R (GAM1; Wood 2006). We added animal activity (non-active, active) as a dependent variable, while main and interactive effects of independent variables, i.e. maximum daily temperature and time of the day, were fitted as nonparametric smoothing terms (tensor product smooth). As we assumed a higher level of curvilinearity in the effect of time of the day rather than in temperature, for time variable, we increased smoothing range (maximum available degrees of freedom). Time of the day was incorporated into model formula by a cubic regression spline which allowed us to obtain the same activity predictions at both extremes of the time range. To verify whether maximum daily temperature and time of the day affected the probability of using canopy cover by moose and the density of utilized canopy cover, we applied GAMs with binomial (GAM2) and gaussian (GAM3) error structures, respectively. In GAM2, we set the utilization of canopy cover (no or yes) as a dependent variable, while in GAM3, it was a tree density cover. In GAM3, we used only moose positions located under canopy cover (tree density cover > 0; n = 59,650). In both models, explanatory variables included the main and interactive effects of maximum daily temperature and time of the day that were fitted as nonparametric smoothing terms. We used the same smoothing settings as applied in GAM1. We repeated sampling of the same individuals over 5 years. Therefore we added moose identification number (ID) and year as categorical random factors to all GAMs as penalized regression terms (Wood 2006). For each global model (GAM1-GAM3), we created a set of submodels which were ranked with the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) (Burnham and Anderson 2002). All competing models had the same set of random factors. Submodels differed in their composition regarding explanatory variables and the presence/absence of interaction term (for more details see Supplementary material, Table S1). All submodels close to the top submodel (lowest AIC), having ΔAIC < 2, were considered to have substantial empirical support.

In order to validate the prediction accuracy of applied models (GAM1-GAM3), we performed the tenfold cross-validation (Burnham 1989; James et al. 2013). For models with categorical responses (GAM1-GAM2), from all available data records, we randomly selected 1000 data records with response variable = 1, and 1000 data records with response variable = 0, so a random sample of 2000 records had an equal number of observations in both categories of response value. Then, each random sample was randomly split into 10 subset (n = 200 records each), and one subset was used for model evaluation with the remaining nine subsets (i.e. 1800 records) for model fit. Next, we made predictions from the fitted model for the evaluation subset. Prediction accuracy was estimated as a proportion of 200 records correctly classified. This procedure was repeated 10 times, each time a different subset served for evaluation. The whole cross-validation, starting from drawing 2000 samples, was repeated 100 times and all prediction accuracy estimates were averaged. As we selected an equal number of samples in both categories of binomial responses, i.e. the same number of records classified as moose non-active and active and an equal number of records within an outside canopy cover, the probability of correct classification to each class by chance was 50%. In case of GAM3, which had a continuous response variable, prediction accuracy was expressed as the correlation between predicted and observed tree density cover. Statistical analyses were done in R (R Development Core Team 2018).

Results

For all surveyed global models (GAM1-GAM3), among all combinations of considered submodels, the top-ranked models were global models i.e. including both main and interactive effects of the maximum daily temperature and time of the day (Table S1). Results of GAM1 indicated significant differences in the probability of moose activity across time of the day (Table 1, Χ2 = 49.0, P < 0.001). There were two peaks of moose activity that coincided with the dawn and dusk hours (Fig. 2). Increasing maximum daily temperature caused significant increase of the probability of moose activity at dawn (1.00–4.00 h) and dusk (18.00–21.00 h) hours but did not influence activity in day hours (5.00–17.00 h; Table1; Χ2 = 276.6; P < 0.001). With maximum temperature increasing from 18 to 36 ºC, the probability of moose activity increased from 49 to 64% at 4.00 h and from 61 to 73% at 20.00 h (Fig. 2). Moreover, when temperatures were elevated, moose expressed longer periods of increased activity at dawn and dusk, compared with cooler days. At dawn, the probability of moose activity equaling at least 50% occurred for 1.2 h at 15 ºC and for 3.5 h at 35ºC, while at dusk for 2.1 h and 4.5 h, respectively. The maximum daily temperature also significantly influenced the daily pattern of canopy cover utilization by moose (GAM2; Table 1, Χ2 = 162.5, P = 0.007). Maximum daily temperatures exceeding 28 ºC increased the probability of canopy utilization by moose throughout the day (Fig. 3). Moreover, the highest effect of temperature was indicated at midday. With maximum daily temperatures increasing from 28 to 36 ºC at noon, the probability of canopy utilization increased from 38 to 47% (Fig. 3). We observed that forests utilized by moose in summer differed in tree density, depending on maximum daily temperature and time of the day (GAM3; Table 1, F = 3.34, P < 0.001). Regardless of maximum daily temperature, moose used denser forest during the daytime rather than night hours (Table 1, F = 28.5, P < 0.001). Increasing temperature resulted in the increased utilization of denser tree stands, mainly during daytime (Fig. 4). Cross-validation revealed varying prediction accuracy of applied models (GAM1-GAM3). The highest model accuracy was indicated for the model which tested the interactive effect of maximum daily temperature and time of the day on the probability of utilization of canopy cover by moose (81%; GAM2), while GAM1 and GAM3 had a lower prediction accuracy (64%, R = 0.41, respectively; Table1).

Predicted association between maximum daily temperature in summer (June 1–August 31), time of the day (hour) and the probability of moose activity (main panel; GAM1). Upper panel contains figures presenting the relationship between the time of the day and the probability of moose activity at different temperatures (15, 25 and 35 ºC). Right panel shows figures presenting the association between maximum daily temperature and the probability of moose activity at different time of the day (4, 12, 20 h)

Predicted effect of the maximum daily temperature in summer (June 1–August 31) and time of the day (hour) on the probability of canopy cover utilization by moose (main panel; GAM2). Upper panel contains figures presenting the relationship between the time of the day and the probability of canopy cover utilization at different temperatures (15, 25 and 35 ºC). Right panel shows figures presenting the association between maximum daily temperature and the probability of moose activity at different time of the day (4, 12, 20 h)

Predicted effect of the maximum daily temperature in summer (June 1–August 31) and time of the day (hour) on the density of canopy cover utilized by moose (main panel, GAM3). Upper panel contains figures presenting the relationship between the time of the day and the probability of canopy cover utilization at different temperatures (15, 25 and 35 ºC). Right panel shows figures presenting the association between maximum daily temperature and canopy cover utilization at different time of the day (4, 12, 20 h)

Discussion

Moose, as a boreal species, are expected to be negatively affected by global warming. However, the unfavourable influence of increasing temperatures can at least be partly mitigated by the adjustment of behaviours that allow animals to escape heat stress and thus maintain optimal fitness. Our study has identified evidence for temperature-mediated behavioural changes in moose occurring at the southwestern edge of the species range. On the hottest days, the probability of moose activity substantially increased during twilight hours and remained unchanged (equally low) in the afternoon hours. At the same time, elevated temperatures (above 20 ºC) caused significantly more intensive utilization of habitat patches, especially those with denser tree cover, which might more efficiently protect against the adverse impact of solar radiation.

The increased utilization of dense canopy cover as a strategy of overheating avoidance was broadly reported by previous studies worldwide, from other parts of the moose range (Schwab and Pitt 1991; Olson et al. 2014). On the hottest days, the sheltering efficiency of canopy cover increased with the height and density of the forest patches (van Beest et al. 2012; Melin et al. 2014). The temperatures at the ground level decreased with the increasing canopy height and crown closure (Demarchi and Bunnell 1993; Melin et al. 2014; Street et al. 2015). Additionally, during hot periods, canopy cover can also provide an effective protection against blood sucking insects, whose harassment is greater in open habitats compared with shadowed sites (Schneider et al. 2013).

Longer periods of greater moose activity at twilight throughout the hottest days suggests that moose might have tried to compensate for energy losses by increased foraging activity during cooler parts of the day. According to the heat dissipation limit (HDL) hypothesis, the energy budget of endotherms can be substantially affected by the capacity of discarding body heat (Speakman and Król 2010). This is especially true for large endotherms which are less able to dissipate heat and avoid overheating by changing patterns of daily activity and forage predominantly at nighttime when temperatures abate (Hamel and Côté 2008; Aublet et al. 2009). On the other hand, increased activity of moose at dawn and dusk might have been partly influenced by the habitat switching.

Compensatory foraging activity at twilight seems to be a basic mechanism that allows heat-sensitive species to maintain daily energy balance during the warmest summer days. This is especially important for moose and other ungulates inhabiting temperate environments, with severe winters, where efficient food acquisition during summer, determines body condition affecting successful reproduction and survival during the following winter and early spring (Cook et al. 2004; Parker et al. 2009). Although, our study was able to capture clear behavioral changes in daily activity patterns under high ambient temperatures, we still know little about how it translated into physiological states of the animals and their fitness components. Such knowledge would be crucial to understanding whether observed behavioral changes in activity pattern would be sufficient to be able to counteract ongoing climatic changes and to predict how species might react to future warming scenarios. Examples from North America, highlighted evidence that moose populations occurring at the southwestern edge of the species range could no longer offset the losses incurred by prolonged exposure to increasing temperature. The negative effects of elevated temperatures were expressed in lower moose reproduction (Ruprecht et al. 2016), reduced overwinter survival (Lenarz et al. 2009), decline in lifespan with body mass (Hoy et al. 2018) and finally shrinking species range (Murray et al. 2006; Dou et al. 2013).

To summarize, our obtained results revealed that, similarly to the populations from more northern latitudes (van Beest et al. 2012; Melin et al. 2014), moose at the southwestern edge of the species’ range in Europe, counteract the negative impact of increasing temperatures by seeking thermal shelter under dense canopy cover. Therefore, under ongoing global warming, we anticipate increasing demand by moose for such refuge habitats during the hottest part of the day. This notion can be of great importance for the conservation and management of moose populations, as the availability of shelter-providing habitats can determine future species survival across its southern range. In addition, our study indicated that during the hottest summer days, moose changed their daily activity pattern which was expressed in increased twilight activity. However, our findings do not provide evidence as to whether these behavioral modifications sufficed to keep individuals in their thermal comfort zone. Hence, a proper understanding of how increasing temperatures translate into individual fitness components needs further investigation. Such knowledge is of paramount importance, since as a temperature-induced decline in moose fitness, can eventually lead to a contraction of the species range. This would have a profound impact on the entire moose population throughout Europe, because southwestern populations of moose in Europe harbor the highest genetic diversity (Świsłocka et al. 2013; Niedziałkowska et al. 2016).

References

Aublet JF, Festa-Bianchet M, Bergero D, Bassano B (2009) Temperature constraints on foraging behavior of male Alpine ibex (Capra ibex) in summer. Oecologia 159:237–247

Bartoszuk H (2005) Zbiorowiska roślinne Biebrzańskiego Parku Narodowego. In: Dyrcz A, Werpachowski C (eds) Przyroda Biebrzańskiego Parku Narodowego. Biebrzański Park Narodowy, Osowiec-Twierdza, pp 133–148

Belovsky GE (1981) Optimal activity times and habitat choice of moose. Oecologia 48:22–30

Borowik T, Cornulier T, Jędrzejewska B (2013) Environmental factors shaping ungulate abundances in Poland. Acta Theriol 58:403–413

Borowik T, Ratkiewicz M, Maślanko W, Duda N, Kowalczyk R (2020) The level of habitat patchiness influences movement strategy of moose in Eastern Poland. PLoS ONE 15(3):e0230521

Borowik T, Ratkiewicz M, Maślanko W, Duda N, Rode P, Kowalczyk R (2018) Living on the edge: predicted impact of renewed hunting on moose in national parks in Poland. Basic Appl Ecol 30:87–95

Broders HG, Coombs AB, McCarron JR (2012) Ecothermic responses of moose (Alces alces) to thermoregulatory stress on mainland Nova Scotia. Alces 48:53–61

Brown GS (2011) Patterns and causes of demographic variation in a harvested moose population: evidence for the effects of climate and density-dependent drivers. J Anim Ecol 80:1288–1298

Burnham P (1989) A comparative study of ordinary cross-validation, v-folds cross-validation and the repeated learning-testing method. Biometrika 76:503–514

Burnham KP, Anderson DR (2002) Model selection and multi-model inference: a practical information-theoretic approach. Springer, New York

Chen IC, Hill JK, Ohlemüller R, Roy DB, Thomas CD (2011) Rapid change shifts of species associated with high levels of climate warming. Science 333:1024–1026

Cook JG, Johnson BK, Cook RC, Riggs RA, Delcurto T, Bryant LD, Irwin LL (2004) Effects of summer-autumn nutrition and parturition date on reproduction and survival of elk. Wildl Monogr 155:1–61

Demarchi MW, Bunnell FL (1993) Estimating forest canopy effects on summer thermal cover for Cervidae (deer family). Can J For Res 23:2419–2426

Ditmer MA, Moen RA, Windels SK, Forester JD, Ness TE, Harris TR (2018) Moose at their bioclimatic edge alter their behavior based on weather, landscape, and predators. Curr Zool 64:419–432

Dou H, Jiang G, Scott P, Piao R (2013) Climate change impacts population dynamics and distribution shift in moose Alces alces in Heilongjiang Province of China. Ecol Res 28:625–632

Gardner JL, Peters A, Kearney MR, Joseph L, Heinsohn R (2011) Declining body size: a third universal response to warming? Trends Ecol Evol 26:285–291

Gazda L (2005) Geologia, geomorfologia i gleby Rezerwatu Biosfery „Polesie Zachodnie”. In: Chmielewski TJ (ed) Rezerwat Biosfery „Polesie Zachodnie”: walory, funkcjonowanie, perspektywy rozwoju. PPH Zapol, Lublin, pp 29–35

Gębczyńska Z, Raczyński J (2004) Łoś w Kotlinie Biebrzańskiej. Sytuacja łosia w Polsce: materiały z konferencji. Biebrzański Park Narodowy, Osowiec-Twierdza, pp 5–19

Geist V (1987) On the evolution and adaptations of Alces. Swed Wildl Res Suppl 1:11–23

Hamel S, Côté SD (2008) Trade-offs in activity budget in an alpine ungulate: contrasting lactating and non-lactating females. Anim Behav 75:217–227

Hampe A, Petit RJ (2005) Conservation biodiversity under climate change: the rear edge matters. Ecol Lett 8:461–467

Harasimiuk M (2009) Analiza geologicznych, geomorfologicznych i hydrologicznych uwarunkowań powstania krajobrazów hydrogenicznych w rejonie objętym statusem Rezerwatu Biosfery „Polesie Zachodnie”. In: Chmielewski TJ (ed) Rezerwat Biosfery „Polesie Zachodnie”: walory, funkcjonowanie, perspektywy rozwoju. PPH Zapol, Lublin, pp 37–46

Hoy SR, Peterson RO, Vucetich JA (2018) Climate warming is associated with smaller body size and shorter lifespans in moose near their southern range limit. Glob Change Biol 24:2488–2497

James G, Witten D, Hastie T, Tibshirani R (2013) An introduction to statistical learning with applications in R. Springer, New York

Jędrzejewski W, Niedziałkowska M, Hayward MW, Goszczyński J, Jędrzejewska B, Borowik T, Bartoń KA, Nowak S, Harmuszkiewicz J, Juszczyk A, Kałamarz T, Kloch A, Koniuch J, Kotiuk K, Mysłajek RW, Nędzyńska M, Olczyk A, Teleon M, Wojtulewicz M (2012) Prey choice and diet of wolves related to ungulate communities and wolf subpopulations in Poland. J Mammal 93:1480–1492

Karns PD (1997) Population distribution, density and trends. In: Franzmann AW, Schwartz CC, McCabe RE (eds) Ecology and management of the North American moose. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington and London, pp 125–140

Kaszewski BM (2005) Warunki klimatyczne Rezerwatu Biosfery „Polesie Zachodnie”. In: Chmielewski TJ (ed) Rezerwat Biosfery „Polesie Zachodnie”: walory, funkcjonowanie, perspektywy rozwoju. PPH Zapol, Lublin, pp 36–44

Kie JG (1999) Optimal foraging and risk of predation: effects on behavior and social structure in ungulates. J Mammal 80:1114–1129

Kingsolver JG, Huey RB (2008) Size, temperature, and fitness: three rules. Evol Ecol Res 10:251–268

Lawton JH (1993) Range, population abundance and conservation. Trends Ecol Evol 8:409–413

Lenarz MS, Nelson ME, Schrage MW, Edwards AJ (2009) Temperature mediated moose survival in northeastern Minnesota. J Wild Manag 73:503–510

Lowe SJ, Patterson BR, Schaefer JA (2010) Lack of behavioral responses of moose (Alces alces) to high ambient temperature near the southern periphery of their range. Can J Zool 88:1032–1041

Maloney SK, Moss G, Cartmell T, Mitchell D (2005) Alteration in diel activity patterns as a thermoregulatory strategy in black wildebeest (Connochaetes gnou). J Comp Physiol A 191:1055–1064

Mason THE, Brivio F, Stephens PA, Apollonio M, Grignolio S (2017) The behavioral treade-off between thermoregulation and foraging in a heat-sensitive species. Behav Ecol 28:908–918

McCann NP, Moen RA, Harris TR (2013) Warm-season heat stress in moose (Alces alces). Can J Zool 91:893–898

Melin M, Mutala J, Mehtätalo L, Tiilikainen R, Tikkanen OP, Maltamo M, Pusenius J, Packalen P (2014) Moose (Alces alces) reacts to high summer temperatures by utilizing thermal shelters in boreal forests—an analysis based on airborne laser scanning of the canopy structure at moose locations. Glob Change Biol 20:1115–1125

Monteith KL, Klaver RV, Hersey KR, Holland AA, Thomas TP, Kauffman MJ (2015) Effects of climate on plant phenology on recruitment of moose at the southern extent of their range. Oecologia 178:1137–1148

Murray DL, Cox EW, Ballard WB, Whitlaw HA, Lenarx MS (2006) Pathogens, nutritional deficiency, and climate influences on a declining moose population. Wildl Monogr 166:1–30

Niedziałkowska M, Hundertmark KJ, Jędrzejewska B, Sidorovich VE, Zalewska H, Veeroja R, Solberg E, Laaksonen S, Sand H, Solovyev VA, Sagaydak A, Tiainen J, Juskaitis R, Done G, Borodulin VA, Tulandin EA, Niedziałkowski K (2016) The contemporary genetic pattern of European moose is shaped by postglacial recolonization, bottlenecks, and the geographical barrier of the Baltic Sea. Biol J Linn Soc 117:879–894

Olson B, Windels SK, Fulton M, Moen R (2014) Fine-scale temperature patterns in the southern boreal forest: implications for the cold-adapted moose. Alces 50:105–120

Parker KL, Barboza PS, Gillingham MP (2009) Nutrition integrates environmental responses of ungulates. Funct Ecol 23:57–69

Parmesan C, Yohe G (2003) A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature 421:37–42

Piasecki D (2005) Ekosystemy leśne regionu. In: Chmielewski TJ (ed) Rezerwat Biosfery „Polesie Zachodnie”: walory, funkcjonowanie, perspektywy rozwoju. PPH Zapol, Lublin, pp 64–67

R Development Core Team (2018) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria

Re3data.Org (2019) Copernicus. re3data.org—Registry of Research Data Repositories. https://doi.org/10.17616/R3TW53

Renecker LA, Hudson RJ (1986) Seasonal energy expenditures and thermoregulatory responses of moose. Can J Zool 64:322–327

Root TL, Price JT, Hall KR, Schneider SH, Rosenzweig C, Pounds JA (2003) Fingerprints of global warming on wild animals and plants. Nature 421:57–60

Ruprecht JS, Hersey KR, Hafen K, Monteith KL, DeCesare NJ (2016) Reproduction in moose at their souther range limit. J Mammal 97:1355–1365

Sargeant G, Eberhardt LE, Peek JM (1994) Thermoregulation by mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) in arid rangelands of southcentral Washington. J Mammal 75:536–544

Schneider TC, Kowalczyk R, Köhler M (2013) Resting site selection by large herbivores—the case of European bison (Bison bonasus) in Białowieża Primeval Forest. Mamm Biol 78:438–445

Schwab FE, Pitt MD (1991) Moose selection of canopy cover types related to operative temperture, forage, and snow depth. Can J Zool 59:3071–3077

Speakman JR, Król E (2010) Maximal heat dissipation capacity and hyperthermia risk: neglected key factors in the ecology of endotherms. J Anim Ecol 79:726–746

Street GM, Rodgers AR, Fryxell JM (2015) Mid-day temperature variation infleunces seasonal habitat selsection by moose. J Wildl Manag 79:505–512

Świsłocka M, Czajkowska M, Duda N, Danylow J, Owadowska-Cornil E, Ratkiewicz M (2013) Complex patterns of population genetic structure of moose, Alces alces, after recent spatial expansion in Poland revealed by sex-linked markers. Acta Theriol 58:367–378

Urban D (2005) Ekosystemy torfowiskowe Rezerwatu Biosfery „Polesie Zachodnie”. In: Chmielewski TJ (ed) Rezerwat Biosfery „Polesie Zachodnie”: walory, funkcjonowanie, perspektywy rozwoju. PPH Zapol, Lublin, pp 60–63

Van Beest FM, Van Moorter B, Milner JM (2012) Temperature-mediated habitat use and selection by a heat-sensitive northern ungulate. Anim Behav 84:723–735

Vucetich JA, Waite TA (2003) Spatial patterns of demography and genetic processes across the species’ range: null hypotheses for landscape conservation genetics. Conserv Gen 4:639–645

Walther R (2004) Plants in a warmer world. Perspect Plant Ecol 6:169–185

Wawrzyniak P, Jędrzejewski W, Jędrzejewska B, Borowik T (2010) Ungulates and their management in Poland. In: Apollonio M, Andersen R, Putman R (eds) European ungulates and their management in the 21st century. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 223–242

Wood SN (2006) Generalized additive models: an introduction with R. Texts in statistical science. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton

Żurek S (2005) Rzeźba i budowa geologiczna doliny Biebrzy. In: Chmielewski TJ (ed) Rezerwat Biosfery „Polesie Zachodnie”: walory, funkcjonowanie, perspektywy rozwoju. PPH Zapol, Lublin, pp 19–32

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the authorities of the Biebrza and Polesie National Parks, as well as the Knyszyn, Rajgród, Parczew, Sobibór, and Włodawa forest districts and P. Rode (University of Białystok) for their help with moose immobilisation and collaring. We also thank M. Żmihorski for his advice regarding data analyses. Furthermore, we express our gratitude to reviewers whose remarks substantially improved the paper. This study was financed by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education of Poland, Project No. NN3042809940 (National Science Centre, NCN; Poland) granted to M. Ratkiewicz and under subsidy for maintaining the research potential of the Faculty of Molecular Zoology, University of Bialystok (for moose in the Biebrza NP) and the budget of the University of Life Sciences in Lublin (for moose in the Polesie NP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Borowik, T., Ratkiewicz, M., Maślanko, W. et al. Too hot to handle: summer space use shift in a cold-adapted ungulate at the edge of its range. Landscape Ecol 35, 1341–1351 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-020-01018-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-020-01018-4