Abstract

Context

Abandonment of extensively managed meadows is an ongoing global challenge in recent decades, particularly in mountain regions, and directly affects plant diversity. However, the extent to which plant diversity further affects associated insect pollinators or herbivores is little investigated.

Objectives

We focused on the effects of abandonment of mountain meadows on species richness and assemblages of bumblebees, bugs and grasshoppers. Specifically, we investigated the influence of vegetation cover, flower cover, plant richness and surrounding landscape on the three insect groups.

Methods

Species richness, abundance and species assemblages of bumblebees, bugs and grasshoppers were surveyed in one Swiss and two Austrian regions: three meadows which had been abandoned for 15–60 years, and three extensively managed meadows (mown once a year, no use of fertilizers). We surveyed bumblebees and bugs by sweep net, and grasshoppers using the time-effective soundscape approach.

Results

Bumblebee species richness and abundance were significantly higher in managed meadows, whereas bug and grasshopper richness and abundance showed no differences between both management types. Managed and abandoned meadows harboured significantly different species assemblages of bugs and grasshoppers, but not of bumblebees. Increasing flower cover and plant richness increased bumblebee richness, but correlated negatively with richness of bugs. Surrounding open landscape positively affected bugs. Caelifera positively correlated with surrounding forest cover and negatively with vegetation cover. Vegetation cover positively affected Ensifera.

Conclusions

Abandoned and extensively managed meadows are important habitat types for the conservation of the three insect groups, thus suggesting the maintenance of both habitat types within mountain landscapes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Grasslands are an integral part of Central European cultural landscapes, and most grassland communities originate from human land use (Moog et al. 2002; Poschlod et al. 2009). Human land use is one of the most important determinants of grassland biodiversity (Maurer et al. 2006; Fischer et al. 2008; McGinlay et al. 2017). In recent decades, especially in European mountain grasslands, two contrasting trends could be observed: management of productive and easily accessible areas has been intensified, whereas areas that do not allow mechanised agricultural techniques have been abandoned (Tasser and Tappeiner 2002; Strijker 2005; Prévosto et al. 2011). Steep and inaccessible slopes in mountain regions, in particular, are more prone to abandonment (Tasser et al. 2007). Mountain meadows were maintained for centuries by local farmers (Tappeiner and Cernusca 1993). Due to socioeconomic factors, a cessation of grassland management is taking place, especially on grassland with marginal agricultural value (Bohner et al. 2012; Hinojosa et al. 2016) such as extensively managed meadows in mountain regions. Changes in agriculture either by intensification or abandonment have resulted in a reduction of semi-natural grasslands in Europe (Baur et al. 2006a; Graf et al. 2014). After land-use abandonment, succession starts immediately (Tasser and Tappeiner 2002), leading to shrub encroachment and establishment of woody species in open grassland (Komac et al. 2013; Wiezik et al. 2013). The process of shrub encroachment depends on several factors such as proximity to forest, altitude and steepness of the slope (Tasser et al. 2007). Regular management is important for the maintenance of semi-natural grassland (Fonderflick et al. 2014).

The aim of this study was to investigate the impact of abandonment on species richness, abundance and species assemblages of bumblebees, heteropteran bugs and grasshoppers within three regions across the Alps by comparing extensive (annually mown, non-fertilized) and abandoned meadows.

Bumblebees were studied because they are important pollinators in many areas (Corbet et al. 1991; Wood et al. 2016) and have been shown to be suitable bioindicators for human impacts at the landscape level (Sepp et al. 2004). In recent decades, bumblebees are known to be in decline due to e.g. reduction of floral resources or loss of suitable nest sites (Carvell 2002; Nieto et al. 2014). As bumblebees require unimproved, flower-rich grasslands (Williams 1988), the loss of flower-rich grasslands and consequent loss of suitable floral resources due to abandonment is assumed to decrease bumblebee species richness and abundance.

Heteropteran bugs were investigated because they are an appropriate indicator for total insect diversity in managed landscapes (Duelli and Obrist 1998). They are influenced by various vegetation factors (e.g. Frank and Künzle 2006; Zurbrügg and Frank 2006) and might respond differently to changes of microclimatic conditions (Di Giulio et al. 2001).

Many grasshopper species, which are important primary and secondary consumers in grasslands (Ingrisch and Köhler 1998), are tightly bound to their habitat, react very sensitively to environmental changes (Baur et al. 2006b) and are prone to grassland abandonment (Marini et al. 2009; Uchida et al. 2016). They are suitable indicators for land-use change as they show a clear response to succession (Fartmann et al. 2012).

In the present study, we expected that bumblebees, heteropteran bugs and grasshoppers would show a clear response to abandonment. Therefore, we included factors such as vegetation cover, flower cover, plant richness and surrounding landscape structure (forest cover and open landscape) in the analysis.

We addressed the following hypotheses:

-

1.

There is a significant difference in species richness and species assemblages of bumblebees, heteropteran bugs and grasshoppers between managed and abandoned meadows.

-

2.

There is a specific influence of vegetation cover, flower cover, plant richness and surrounding landscape structure on species richness and abundance of bumblebees, heteropteran bugs and grasshoppers.

Materials and methods

Study regions and sites

The study was conducted in June and August 2015 in three regions across the Austrian and Swiss Alps (Fig. 1). The study regions comprised the Eisenwurzen region (Styria, Austria, mean annual air temperature: 6.9 °C, mean annual precipitation: 1 087 mm) with study sites in the municipalities of St. Gallen (47°41′N, 14°37′E), Stainach (47°32′N, 14°06′E) and Pürgg (47°31′N, 14°03′E), the Biosphere Reserve Großes Walsertal region (Vorarlberg, Austria, mean annual air temperature: 5.7 °C, mean annual precipitation: 1 630 mm) in the municipality of Sonntag/Buchboden (47°14′N, 9°57′E) and the Biosphere Reserve Val Müstair region (Graubünden, Switzerland, mean annual air temperature: 5.9 °C, mean annual precipitation: 810 mm) in the municipalities Tschierv (46°37′N, 10°20′E), Valchava (46°36′N, 10°24′E) and St. Maria (46°36′N, 10°25′E). Altogether, we surveyed six semi-dry meadows located on south-facing slopes within each study region, three of them extensively managed and three abandoned. Extensively managed meadows are mown once a year, usually between mid-July and the beginning of August, and receive no fertilizer treatment. Cessation of management in the abandoned meadows occurred at least 15 years ago, with the shortest time since abandonment in the Biosphere Reserve Val Müstair (15–20 years) and the longest time since abandonment in the Biosphere Reserve Großes Walsertal (35–60 years). Abandoned sites in the Eisenwurzen region were between 20 and 40 years old. Before cessation of management, abandoned meadows were used as extensively managed meadows and were never used as pastures. Information on former management was gathered via interviews with land owners. The meadows in the Eisenwurzen region were situated between 660 and 790 m above sea level, the meadows in the Biosphere Reserves Großes Walsertal and Val Müstair were situated between 1180 and 1250 m a. s. l., and between 1740 and 1800 m a. s. l., respectively. The sizes of managed meadows ranged between 470 and 5150 m2, the sizes of abandoned meadows between 300 and 4300 m2. There was no significant difference between size of abandoned and managed meadows for each of the three regions (Eisenwurzen: F = 1.832, p = 0.247; Großes Walsertal: F = 3.561, p = 0.132; Val Müstair: F = 1.378, p = 0.306; ANOVA). To assess the influence of the surrounding landscape structure, a circle with a radius of 500 m was drawn around the centre of each study site and the proportion of open landscape (intensive meadows, extensive meadows, pastures) and forest cover (closed forest) was measured in ArcGIS based on existing maps (ArcGIS basemap). Built-up land (single houses, villages, huts) was not considered since it occurred only at the circle margins of one site in the Eisenwurzen region and had a maximum proportion of only 5% within the 500 m radius.

Location of the three study regions Eisenwurzen, Großes Walsertal and Val Müstair. Detailed inset maps are shown for the study region Großes Walsertal (open square delineates location of managed meadows, open circle delineates location of abandoned meadows) (data source: www.basemap.at)

Bumblebee sampling

Species richness and abundance of bumblebees was surveyed once in June and once in August 2015. We observed four 20 m2 (4 × 5 m squares) study plots within each meadow for 15 min each, and collected and counted every individual bumblebee occurring in these study plots. The first plot was chosen randomly, approximately in the centre of each meadow. Further plots were selected along a straight transect in a standardised manner at distances of 3, 9 and 27 m from the first plot (logarithmic distances). Sampling was carried out during suitable weather conditions (dry vegetation, no more than slight wind, temperature >15 °C, sunshine) and between 9 a.m. and 5 p.m. On-site identification of species was performed following the approach proposed by Gokcezade et al. (2015). To identify bumblebees, single individuals were caught in plastic tubes and fixed at the bottom of the tube with a plastic foam plug. After immobilisation of a bumblebee, identification was conducted using a hand lens (magnification ×20). After identification, bumblebees were released on-site. Any individual that could not be identified on-site was killed using acetic ether and stored in previously prepared plastic bags. Additionally, the collected individuals were treated with Thymol (2-isopropyl-5-methylphenol), a fungicide, inhibiting mould formation and infestation of collected bumblebees. Identification of collected bumblebees was subsequently performed in the laboratory using a stereo microscope, with reference to Mauss (1990). For further analysis, we classified bumblebees as long-tongued species (long- and intermediate long-tongued) and short-tongued species (short- and intermediate short-tongued) (von Hagen and Aichhorn 2014).

Heteropteran bug sampling

Heteropteran bug species richness and abundance was assessed once in June and once in August 2015. For sampling, a sweep net method was applied along defined transects approximately in the centre of each meadow. We conducted a total of 90 sweeps per meadow, separated in 3 × 30 sweeps. The net, consisting of a white heavy cloth, was approximately 70 cm long with an opening diameter of 40 cm, mounted on a stick of 1 m length. In the laboratory, identification of species was performed using a stereo microscope, with reference to Wagner (1952, 1966, 1967) and Strauss (2010). For further analysis, species were classified into phytophagous and zoophagous trophic levels. Overwintering strategy was classified, differentiating heteropteran bugs overwintering as imagoes or eggs. All information regarding food preference and overwintering strategy was gathered from Wagner (1952, 1966, 1967) and Strauss (2010).

Grasshopper sampling

Grasshoppers (Orthoptera: Ensifera and Caelifera) were surveyed once in August 2015 during the peak of almost all of the species’ populations (Marini et al. 2010). Surveys were performed with recording devices (Olympus LS-12, Olympus Europa SE & CO. KG) to record sound production, which represents a suitable method for assessing species richness of grasshoppers within their environment (Chesmore and Ohya 2004; Lehmann et al. 2014). The soundscape approach provides a time-effective field method for examining species richness, compared to conventional methods (Gardiner and Hill 2006; Buri et al. 2013). A heterodyne bat detector was connected to the recorder as an ultrasonic microphone, in order to amplify grasshopper sounds (Batbox III D, Batbox Ltd. Steyning, UK). The frequency range of the heterodyne bat detector was adjusted to a frequency of 27 kHz with a bandwidth of 16 kHz. The recorders and the bat detectors were placed in the centre of each study site at a height of 80 cm. Sampling was carried out during dry weather conditions, sunshine, temperatures above 20 °C and no more than slight wind. The recording time lasted from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., leading to a total recording time of 7 h per day. We identified species by listening to the records in the laboratory using acoustic comparison material from the field and archives (e.g. Roesti and Keist 2009). For further analysis, grasshoppers were subdivided into the suborders Ensifera and Caelifera in accordance with Baur et al. (2006b).

Plant parameters

To assess the influence of several plant parameters on bumblebees, bugs and grasshoppers, we investigated plant species richness, vegetation cover and flower cover in four randomly chosen 1 m2 study plots in the centre of each meadow in June and August 2015. A frame of 1 m2 size (1 × 1 m) was placed on the ground with the edges parallel to the hill slope (Karrer 2015), and each plant species within the 1 m2 study plot was identified to species level. Vegetation cover in percent, including both necromass and living biomass, and proportion of open ground (bare soil, rocks) were estimated within the 1 m2 frame. Proportion of flower cover was also assessed within the 1 m2 frame. Individual plant species were subdivided into plants with open and hidden nectar flowers, since this is an important factor for bumblebees in relation to their tongue length.

Statistical analysis

We checked the data for normal distribution graphically by creating QQ-plots, and statistically using Shapiro-test. We tested for homogeneity of variances (homoscedasticity) using Bartlett-test. In order to assess the effects of the two habitat types—managed and abandoned meadows—on species richness and abundance of bumblebees, heteropteran bugs and grasshoppers, we calculated GLMs with a Poisson distribution, with management and region as explanatory variables (fixed factors). We tested data for over- and under dispersion by applying the function dispersion.test() in R (R-package “AER” 1.2-4, Kleiber et al. 2015). Many of the datasets were over- or under dispersed, which we corrected by specifying quasi-poisson errors (Crawley 2013). We also used GLMs to analyse differences between managed and abandoned meadows regarding trophic levels and overwintering strategy types of heteropteran bugs, tongue length of bumblebees, suborders of grasshoppers, effects of plant parameters (plant species richness, vegetation cover, flower cover, plants with hidden and open nectar flowers) and surrounding landscape structures on the three insect groups. After assessing possible correlations between plant parameters, we found it appropriate to test plant parameters separately, since plant parameters were highly correlated and could not be used in a single GLM model. To test for significant associations of any individual bumblebee, heteropteran bug and grasshopper species with managed or abandoned meadows, we calculated the point-biserial correlation coefficient r pb for each species (Anjum-Zubair et al. 2015). To investigate associations of bumblebee, heteropteran bug and grasshopper species with study sites, we computed the strength and significance of the association using the R-functions strassoc() and signassoc() in R (R-package “indicspecies” 1.7.5, De Cáceres and Jansen 2015). We assessed the significance of the associations with two-sided permutation tests, and calculated confidence intervals by bootstrapping data 999 times with replacement, following Anjum-Zubair et al. (2015).

To assess differences in species assemblages of bumblebees, heteropteran bugs and grasshoppers between managed and abandoned meadows, we conducted a principal coordinate analysis (PCO) based on a resemblance matrix of Bray–Curtis similarity measures. We computed a permutational ANOVA (PERMANOVA) to test for significant differences in species assemblages between managed and abandoned meadows. As with the univariate analysis, we included region as a fixed factor. Residuals were permuted 9999 times under a reduced model. In order to exclude the factors that did not differ in their dispersion, we conducted the PERMDISP-routine in analogy to a homogeneity test before applying an ANOVA. The test was performed on the basis of distances to the centroid with 9999 permutations. P-values were obtained by using permutation of residuals.

In addition, we conducted the SIMPER-routine (similarity percentages) to analyse the role of individual species in contributing to the differences between managed and abandoned meadows.

We conducted PCO, PERMANOVA, PERMDISP and SIMPER routines using the software Primer, version 6.1.13 with PERMANOVA + (PRIMER-E Ltd., Plymouth, UK). All other statistical tests were performed in R-Studio, version 3.1.3 (R Core Team 2015).

Results

Bumblebees

We recorded a total of 83 bumblebee individuals (Bombus sp.) of 14 species (Online Appendix Table 1). Fifty-seven individuals, belonging to 13 species, were identified in managed meadows, and 26 individuals belonging to 9 species were identified in abandoned meadows. One of the total 14 species was a cuckoo bumblebee (Bombus [Psithyrus] sp.). Seven of the 14 species were classified as long-tongued and 7 as short-tongued.

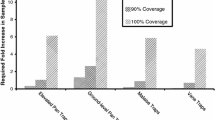

Total species richness of bumblebees was significantly higher in managed meadows compared to abandoned meadows (Table 1; Fig. 2a). Similarly, total number of individuals was also higher in managed meadows (Table 1; Fig. 2b). There was no effect of management on long-tongued and short-tongued species, nor on long-tongued and short-tongued individuals. Total number of individuals and number of individuals of short-tongued species differed significantly between regions (Table 1). Both flower cover and plant richness had a significant influence on total bumblebee species richness (Table 1). Bumblebee species richness increased with increasing flower cover and plant species richness (Table 1). Long-tongued species increased with increasing plant richness, number of short-tongued individuals increased with increasing flower cover (Table 1). No association was found between bumblebees and vegetation cover. Plants with open nectar flowers had a significant positive influence on total number of individuals, short-tongued bumblebee species and individuals (Table 1). A positive association was detected between plants with hidden nectar flowers, total species richness of bumblebees and species richness of long-tongued bumblebees (Table 1).

Neither percentage of open landscape nor forest area had an influence on bumblebees. Results of the point-biserial correlation did not indicate an association of any individual bumblebee species with either managed or abandoned meadows.

The graphical representation of species assemblages in the principal coordinate analysis (PCO) showed no clear separation of species assemblages between managed and abandoned meadows (PERMANOVA, main-test: p = 0.1196, Table 2). Both axes (PCO 1 and PCO 2) of the PCO explained 56% of the total variance (Fig. 3).

SIMPER-analysis showed that the average Bray–Curtis similarity in managed meadows was 25.02, where the five species B. lucorum, B. terrestris, B. lapidarius, B. hortorum and B. humilis explained 88.36% of the similarity. The average Bray–Curtis similarity in abandoned meadows was 6.37, due to the three species B. lapidarius, B. pascuorum and B. humilis, which explained 91.27% of the similarity. An average dissimilarity of 87.11 was detected between managed and abandoned meadows, where 78.91% of the dissimilarity was explained by the six species B. lucorum, B. lapidarius, B. hortorum, B. terrestris, B. mucidus and B. humilis.

Heteropteran bugs

We collected a total of 390 individuals comprising 35 bug species (Online Appendix Table 2). 187 individuals belonging to 21 species were found in managed meadows and 203 individuals belonging to 29 species were found in abandoned meadows. The majority of collected bugs were phytophagous, only three individuals belonging to three species were zoophagous. Regarding overwintering strategy, 28 of the bug species overwinter as imagoes and 9 species overwinter as eggs.

No significant effects of management could be detected for total species richness and total number of individuals, number of phytophagous species/individuals or number of species/individuals overwintering as eggs (Table 1). However, higher numbers of both species and individuals that overwinter as imagoes were found in abandoned meadows. The total number of individuals as well as the number of phytophagous individuals, and the number of individuals overwintering as imagoes differed between regions (Table 1). No significant influence of vegetation cover on bug parameters could be detected. Total species richness of heteropteran bugs, richness of phytophagous species and number of species and individuals overwintering as imagoes decreased with increasing flower cover and plant species richness (Table 1). There was evidence that proportion of surrounding open landscape increased total species richness, total number of individuals, phytophagous species and number of phytophagous individuals (Table 1). Proportion of forest cover had a significant negative influence on total number of species and richness of phytophagous species (Table 1).

Bug species assemblages differed significantly between managed and abandoned meadows. In the PCO (Fig. 4), and confirmed by PERMANOVA analysis, both assemblages were clearly separated (PERMANOVA, main-test: p = 0.0107, Table 2). Both axes of the PCO (PCO 1 and PCO 2) explained 46.8% of the total variation. The average Bray–Curtis similarity in managed meadows according to the SIMPER-routine was 18.68, where the four species Leptopterna dolabrata, Plagiognathus chrysanthemi, Carpocoris purpureipennis and Hadrodemus m-flavum explained 90.43% of the similarity. An average Bray–Curtis similarity of 17.32 was observed in abandoned meadows, where Myrmus miriformis, Stenodema holsata and Carpocoris purpureipennis explained 76% of the similarity. An average dissimilarity of 88.4 was detected between managed and abandoned sites. Sixty-seven percent of the dissimilarity was explained by 10 species (Leptopterna dolabrata, Myrmus miriformis, Stenodema holsata, Stenodema sericans, Plagiognathus crysanthemi, Carpocoris purpureipennis, Spilostethus saxatilis, Hadrodemus m-flavum, Dolycoris baccarum, Stenodema calcarata). The point-biserial correlation coefficient r pb clearly indicated a significant positive association of Myrmus miriformis (r pb association index: 0.54, lower and upper confidence intervals: 0.33 and 0.88, respectively) with abandoned meadows. None of the other species revealed associations with either managed or abandoned meadows.

Grasshoppers

A total of 17 species of grasshoppers were recorded in managed and abandoned meadows (Online Appendix Table 3). Fifteen species were detected in managed meadows and 14 species in abandoned meadows. Due to the method of assessing grasshopper diversity with soundscapes, no data on numbers of individuals was available. Six species belonged to the Ensifera and eleven species belonged to the Caelifera.

There were no significant effects of management on total species richness and no difference in grasshopper parameters between regions. Vegetation cover, flower cover and the proportion of open landscape and forest cover did not significantly influence total grasshopper species richness. Caelifera and Ensifera did not differ significantly between managed and abandoned meadows. Increasing vegetation cover significantly decreased the number of Caelifera, proportion of surrounding forest cover had a significant positive effect on Caelifera, and increasing vegetation cover had a significant positive effect on Ensifera (Table 1).

Grasshopper species assemblages differed significantly between managed and abandoned meadows. In the PCO (Fig. 5), and further confirmed by PERMANOVA analysis, both assemblages were clearly separated (PERMANOVA, main-test: p = 0.001, Table 2). Both axes of the PCO (PCO 1 and PCO 2) explained 77.4% of total variation. The average Bray–Curtis similarity in abandoned meadows according to the SIMPER-routine was 55.8, where five species (Pseudochorthippus parallelus, Roeseliana roeselii, Euthystira brachyptera, Gomphocerippus rufus, Pholidoptera griseoaptera) explained 81% of the similarity. An average Bray–Curtis similarity of 58.5 was observed in managed meadows made up by Stenobothrus lineatus, Chorthippus biguttulus and Pseudochorthippus parallelus which explained 74% of the similarity in managed meadows.

An average dissimilarity of 54.6 was detected between managed and abandoned sites where 68.9% was explained by eight species (Stenobothrus lineatus, Gomphocerippus rufus, Pholidoptera griseoaptera, Chorthippus biguttulus, Tettigonia cantans, Metrioptera brachyptera, Euthystira brachyptera, Roeseliana roeselii). The point-biserial correlation coefficient r pb clearly indicated a significant positive association of Stenobothrus lineatus with managed meadows (r pb association index: 0.89, lower and upper confidence intervals: 0.67 and 1, respectively). None of the other species revealed associations with either managed or abandoned meadows.

Vegetation parameters and landscape structure

Plant species richness and flower cover were significantly higher in managed than in abandoned meadows (ANOVA, F = 16.31; p < 0.001 and F = 34.3; p < 0.001, respectively). Similarly, there were significantly more plants with hidden nectar flowers in managed meadows (F = 24.43; p < 0.001). Vegetation cover was significantly higher in abandoned than in managed meadows (F = 6.52; p = 0.02). No differences between habitat types were found for plants with open nectar flowers. Proportion of open landscape and forest cover were negatively correlated (r = −0.95, p < 0.001).

Discussion

Response of bumblebees to land-use change

Of the 47 bumblebee species occurring in Austria, Germany and Switzerland (Gokcezade et al. 2015), a third of the species could be recorded within the three study regions. Four species (B. lucorum, B. humilis, B. lapidarius, B. hortorum) comprised more than 60% of the total observations. A high abundance of few species has also been shown elsewhere (Dramstad and Fry 1995). Extensively managed meadows revealed a higher bumblebee species richness and abundance than abandoned meadows—as was expected by hypothesis 1. Loosing suitable foraging habitats and floral resources negatively affects bumblebees (Goulson et al. 2008). The present study indicates that abandonment has an adverse impact on bumblebee richness and abundance. Succession and a shift in the cover of dominant plant species (Pavlů et al. 2011) leads to a loss of floral resources. Both higher plant richness and flower cover in managed meadows increased bumblebee richness and abundance supporting the findings of other studies (Ebeling et al. 2008; Fründ et al. 2010). In the present study, higher flower cover was associated with higher plant species richness, illustrating the importance of maintaining a high plant species richness and flower cover within grassland habitats to benefit bumblebee richness. In addition, the diverse, plant species rich managed meadows provide sufficient food supply throughout the almost entire flight season of the bumblebees. Another important point is that managed meadows offer higher amounts of plants with hidden nectar being particularly important for long-tongued bumblebee species. The result that short-tongued bumblebees responded positively to plants with open nectar flowers and long-tongued bumblebees responded positively to plants with hidden nectar flowers is in line with other studies (Dramstad and Fry 1995; Carvell et al. 2004; Goulson 2010).

The majority of bumblebee species observed use a very broad range of habitat types (von Hagen and Aichhorn 2014; Gokcezade et al. 2015), which might explain the lack of difference between the bumblebee species assemblages of managed and abandoned meadows. An abandoned meadow generally undergoes different stages of succession, but some stages may remain stable for decades (Maag et al. 2001) and provide at least a certain amount of floral resources. Due to the high mobility of bumblebees (e.g. Darvill et al. 2004; Osborne et al. 2008) it is very likely that a high species turnover between managed and abandoned meadows occurred in this study since both meadow types were located within the action radius of the recorded bumblebees (e.g. Westphal et al. 2006).

Response of bugs to land-use change

The total number of heteropteran bugs was dominated by only a few species, of which Leptopterna dolobrata comprised more than 39% of the total observations. Hypothesis 1 could not be confirmed for total heteropteran bug species and abundance, but was confirmed for species and individuals overwintering as imagoes. Numbers of bug species and individuals overwintering as imagoes benefitted from the altered environmental conditions in the abandoned meadows. Since many bugs overwintering as imagoes are known to hibernate beneath the litter layer near their host plants (e.g. Rabitsch 2007), it can be assumed that the higher vegetation cover in abandoned meadows provides better protection against environmental influences such as high solar radiation and against dehydration and is therefore a preferred overwintering habitat.

The negative relationship between heteropteran bug species and flower frequency as well as plant richness was rather surprising as it contradicts available literature (e.g. Brändle et al. 2001; Frank and Künzle 2006; Zurbrügg and Frank 2006). Many phytophagous bug species are monophagous or oligophagous and thus require distinct plant species for their development. For example, Leptopterna dolobrata, the most abundant oligophagous species in the present study, feeds on tall grasses like Phleum, Alopecurus, Holcus and Dactylis (Wachmann et al. 2004). The restriction to a single plant species or only several distinct plant species might explain why higher plant species richness does not further increase phytophagous bug species richness. Since species overwintering as imagoes—which were negatively related to plant species richness—hibernate near their host plants, they will not benefit from increasing plant species richness. The positive relationship between bug species and surrounding open landscape may be explained by the fact that open land bugs can use surrounding meadows as retention sites during mowing of the extensive meadows.

Higher vegetation cover, above ground biomass and necromass in the studied abandoned meadows (Karrer 2015) most likely affect microclimatic conditions. Differences in microclimatic conditions are known to influence bugs (Di Giulio et al. 2001; Stoutjesdijk and Barkman 2014), which probably contributed to the significantly different bug assemblages observed between managed and abandoned meadows. For example, Myrmus miriformis, a character species for abandoned meadows in the present study, inhabits a wide range of habitats with the exception of xerothermic habitats (Wachmann et al. 2007). Higher above-ground biomass and necromass in abandoned meadows likely decrease temperature which makes this habitat type more suitable for M. myriformis. This suggests that microclimate has an important influence on the occurrence of this species, which could explain its almost exclusive occurrence in the abandoned meadows.

Response of grasshoppers to land use change

Vegetation cover, which was significantly higher in abandoned meadows, affected grasshoppers, in that Caelifera declined with increasing vegetation cover whereas Ensifera responded positively to increased vegetation cover. Several species of both suborders were restricted to either managed or abandoned meadows. Especially, Stenobothrus lineatus requires short vegetation and a certain amount of open soil (Behrens and Fartmann 2004). S. lineatus was a character species for managed meadows in the present study, and probably required regular mowing for its development and maintenance of viable populations (Marini et al. 2009). Maintenance of management was particularly important for species such as Psophus stridulus, Omocestus rufipes and Decticus verrucivorus, which are listed in the Red List of Austrian Orthoptera (Berg et al. 2005). These species show similar requirements to their habitat and, with the exception P.stridulus, occurred exclusively in managed meadows. Males of P. stridulus require at least some amount of dense vegetation (Hemp and Hemp 2003), which may explain its occurrence in abandoned meadows. Several Ensifera such as Tettigonia cantans, Metrioptera brachyptera and Pholidoptera aptera showed a particular preference for the abandoned meadows. These species require well-structured habitat types with a certain amount of shrubs and dense vegetation (Baur et al. 2006b), and mown meadows generally seem to be particularly unsuitable habitats for most Ensifera (e.g. Braschler et al. 2009). The positive response of Caelifera to surrounding forest cover must not be over-interpreted because Caelifera inhabiting open land would not select forest as suitable habitat. Only forest glades might be a suitable habitat for some species such as Omocestus rufipes (Baur et al. 2006b). It can be possible that forest edges act as refuge for Caelifera during mowing or are used as additional food resource.

The different species assemblages in managed and abandoned meadows are due to different habitat conditions. Thus, abandoned and managed meadows represent suitable habitats for distinct grasshopper species assemblages, and managed meadows proved particularly important for the conservation of three detected endangered species. Our results indicate that managed as well as abandoned meadows are crucial for maintaining grasshoppers in mountain grassland, as both promote distinct, co-existing species assemblages.

Conclusion

Whereas abandonment has often been shown to adversely affect arthropod diversity (e.g. Marini et al. 2009; Uchida and Ushimaru 2014), the present study showed that abandoned meadows that have not yet regrown with forest can provide valuable habitat for heteropteran bugs and grasshoppers. Thus, the occurrence of both managed and abandoned meadows may support the establishment of unique species assemblages, increasing the diversity of heteropteran bugs and grasshoppers across Central European mountain grassland. However, management schemes should aim at regularly removing shrubs and woody plants to prevent the establishment of closed forests on abandoned meadows, which in turn would be detrimental for many open land species. For the conservation of bumblebee diversity, annual mowing is an important management measure to maintain sufficient foraging sources in the long term. In conclusion, regarding conservation of the three insect groups investigated in mountain regions, we recommend that management measures should aim at preserving a heterogeneously structured landscape containing managed as well as abandoned meadows.

References

Anjum-Zubair M, Entling MH, Bruckner A, Drapela T, Frank T (2015) Differentiation of spring carabid beetle assemblages between semi-natural habitats and adjoining winter wheat. Agric Forest Entomol 17(4):355–365

Baur B, Baur H, Roesti C, Roesti D (2006a) Die Heuschrecken der Schweiz. Haupt, Bern

Baur B, Cremene C, Groza G, Rakosy L, Schileyko AA, Baur A, Stoll P, Erhardt A (2006b) Effects of abandonment of subalpine hay meadows on plant and invertebrate diversity in Transylvania, Romania. Biol Conserv 132(2):261–273

Behrens M, Fartmann T (2004) Habitatpräferenzen und Phänologie der Heidegrashüpfer Stenobothrus lineatus, Stenobothrus nigromaculatus und Stenobothrus stigmaticus in der Medebacher Bucht (Südwestfalen/Nordhessen). Articulata 19(2):141–165

Berg HM, Bieringer G, Zechner L (2005) Rote Liste der Heuschrecken (Orthoptera) Österreichs. In: K. P. Zulka, Umweltbundesamt (Red.): Rote Listen gefährdeter Tiere Österreichs. Checklisten, Gefährdungsanalysen, Handlungsbedarf. Teil 1: Säugetiere, Vögel, Heuschrecken, Wasserkäfer, Netzflügler, Schnabelfliegen, Tagfalter. Grüne Reihe des Lebensministeriums, Bd. 14/1, Böhlau Verlag, Wien

Bohner A, Starlinger F, Koutecky P (2012) Vegetation changes in an abandoned montane grassland, compared to changes in a habitat with low-intensity sheep grazing–a case study in Styria, Austria. Eco Mont 4:5–12

Brändle M, Amarell U, Auge H, Klotz S, Brandl R (2001) Plant and insect diversity along a pollution gradient: understanding species richness across trophic levels. Biodivers Conserv 10:1497–1511

Braschler B, Marini L, Thommen GH, Baur B (2009) Effects of small-scale grassland fragmentation and frequent mowing on population density and species diversity of orthopterans: a long-term study. Ecol Entomol 34(3):321–329

Buri P, Arlettaz R, Humbert JY (2013) Delaying mowing and leaving uncut refuges boosts orthopterans in extensively managed meadows: evidence drawn from field-scale experimentation. Agric Ecosyst Environ 181:22–30

Carvell C (2002) Habitat use and conservation of bumblebees (Bombus spp.) under different grassland management regimes. Biol Conserv 103(1):33–49

Carvell C, Meek WR, Pywell RF, Nowakowski M (2004) The response of foraging bumblebees to successional change in newly created arable field margins. Biol Conserv 118(3):327–339

Chesmore ED, Ohya E (2004) Automated identification of field-recorded songs of four British grasshoppers using bioacoustic signal recognition. Bull Entomol Res 94(4):319–330

Corbet SA, Williams IH, Osborne JL (1991) Bees and the pollination of crops and wild flowers in the European Community. Bee World 72:47–59

Crawley MJ (2013) The R Book. Wiley, New York

Darvill B, Knight ME, Goulson D (2004) Use of genetic markers to quantify bumblebee foraging range and nest density. Oikos 107(3):471–478

De Cáceres M, Jansen F (2015) Indicspecies: relationship between species and group of sites. R Package Version 1(7):5

Di Giulio M, Edwards PJ, Meister E (2001) Enhancing insect diversity in agricultural grasslands: the roles of management and landscape structure. J Appl Ecol 38(2):310–319

Dramstad W, Fry G (1995) Foraging activity of bumblebees (Bombus) in relation to flower resources on arable land. Agric Ecosyst Environ 53(2):123–135

Duelli P, Obrist MK (1998) In search of the best correlates for local organismal biodiversity in cultivated areas. Biodivers Conserv 7(3):297–309

Ebeling A, Klein AM, Schumacher J, Weisser WW, Tscharntke T (2008) How does plant richness affect pollinator richness and temporal stability of flower visits? Oikos 117(12):1808–1815

Fartmann T, Krämer B, Stelzner F, Poniatowski D (2012) Orthoptera as ecological indicators for succession in steppe grassland. Ecol Indic 20:337–344

Fischer M, Rudmann-Maurer K, Weyand A, Stöcklin J (2008) Agricultural land use and biodiversity in the Alps: how cultural tradition and socioeconomically motivated changes are shaping grassland biodiversity in the Swiss Alps. Mt Res Dev 28(2):148–155

Fonderflick J, Besnard A, Beuret A, Dalmais M, Schatz B (2014) The impact of grazing management on Orthoptera abundance varies over the season in Mediterranean steppe-like grassland. Acta Oecol 60:7–16

Frank T, Künzle I (2006) Effect of early succession in wildflower areas on bug assemblages (Insecta: Heteroptera). Eur J Entomol 103(1):61–70

Fründ J, Linsenmair KE, Blüthgen N (2010) Pollinator diversity and specialization in relation to flower diversity. Oikos 119(10):1581–1590

Gardiner T, Hill J (2006) A comparison of three sampling techniques used to estimate the population density and assemblage diversity of Orthoptera. J Orthoptera Res 15(1):45–51

Gokcezade JF, Gereben-Krenn B-A, Neumayer J, Krenn HW (2015) Feldbestimmungsschlüssel für die Hummeln Österreichs, Deutschlands und der Schweiz (Hymenoptera, Apidae)—Linz Biolo Beitr 0047_1:5–42

Goulson D (2010) Bumblebees: behaviour, ecology and conservation. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Goulson D, Lye GC, Darvill B (2008) Decline and conservation of bumblebees. Annu Rev Entomol 53:191–208

Graf R, Müller M, Korner P, Jenny M, Jenni L (2014) 20% loss of unimproved farmland in 22 years in the Engadin, Swiss Alps. Agric Ecosyst Environ 185:48–58

Hemp C, Hemp A (2003) Lebensraumansprüche und Verbreitung von Psophus stridulus (Orthoptera: Acrididae) in der Nördlichen Frankenalb. Articulata 18:51–70

Hinojosa L, Napoléone C, Moulery M, Lambin EF (2016) The “mountain effect” in the abandonment of grasslands: insights from the French Southern Alps. Agric Ecosyst Environ 221:115–124

Ingrisch S, Köhler G (1998) Die Heuschrecken Mitteleuropas. Die neue Brehm Bücherei, Bd. 629, Westarp-Wissenschaften, Magdeburg

Karrer J (2015) Abandonment of nutrient poor meadows: Impacts on regulating ecosystem services (decomposition, greenhouse gas efflux) and plant diversity. Master-thesis, University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU), Vienna

Kleiber C, Zeileis A, Zeileis MA (2015) Package ‘AER’: Applied econometrics with R, R Package 1.2-4

Komac B, Kéfi S, Nuche P, Escós J, Alados CL (2013) Modeling shrub encroachment in subalpine grasslands under different environmental and management scenarios. J Environ Manag 121:160–169

Lehmann GU, Frommolt KH, Lehmann AW, Riede K (2014) Baseline data for automated acoustic monitoring of Orthoptera in a Mediterranean landscape, the Hymettos. Greece. J Insect Conserv 18(5):909–925

Maag S, Nösberger J, Lüscher A (2001) Mögliche Folgen einer Bewirtschaftungsaufgabe von Wiesen und Weiden im Berggebiet. Ergebnisse des Komponentenprojektes D, Polyprojekt PRIMALP

Marini L, Bommarco R, Fontana P, Battisti A (2010) Disentangling effects of habitat diversity and area on orthopteran species with contrasting mobility. Biol Conserv 143(9):2164–2171

Marini L, Fontana P, Battisti A, Gaston KJ (2009) Response of orthopteran diversity to abandonment of semi-natural meadows. Agric Ecosyst Environ 132(3):232–236

Maurer K, Weyand A, Fischer M, Stöcklin J (2006) Old cultural traditions, in addition to land use and topography, are shaping plant diversity of grasslands in the Alps. Biol Conserv 130(3):438–446

Mauss V (1990) Bestimmungsschlüssel für die Hummeln der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Deutscher Jugendbund für Naturbeobachtungen (DJN), Hamburg

McGinlay J, Gowing DJG, Budds J (2017) The threat of abandonment in socio-ecological landscapes: farmers´ motivations and perspectives on high nature value grassland conservation. Environ Sci Policy 69:39–49

Moog D, Poschlod P, Kahmen S, Schreiber KF (2002) Comparison of species composition between different grassland management treatments after 25 years. Appl Veg Sci 5(1):99–106

Nieto A, Roberts SPM, Kemp J, Rasmont P, Kuhlmann M, García Criado M, Biesmeijer JC, Bogusch P, Dathe HH, De la Rúa P, De Meulemeester T, Dehon M, Dewulf A, Ortiz-Sánchez FJ, Lhomme P, Pauly A, Potts SG, Praz C, Quaranta M, Radchenko VG, Scheuchl E, Smit J, Straka J, Terzo M, Tomozii B, Window J, Michez D (2014) European red list of bees. Publication Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

Osborne JL, Martin AP, Carreck NL, Swain JL, Knight ME, Goulson D, Hale RJ, Sanderson RA (2008) Bumblebee flight distances in relation to the forage landscape. J Anim Ecol 77:406–415

Pavlů L, Pavlů V, Gaisler J, Hejcman M, Mikulka J (2011) Effect of long-term cutting versus abandonment on the vegetation of a mountain hay meadow (Polygono-Trisetion) in Central Europe. Flora 206(12):1020–1029

Poschlod P, Baumann A, Karlik P (2009) Origin and development of grasslands in Central Europe. In: Veen P et al (eds) Grasslands in Europe of high nature value. KNNV Publishing, Zeist, pp 15–25

Prévosto B, Kuiters L, Bernhardt-Römermann M, Dölle M, Schmidt W, Hoffmann M, Van Uytwanck J, Bohner A, Kreiner D, Stadler J, Klotz S, Brandl R (2011) Impacts of land abandonment on vegetation: successional pathways in European habitats. Folia Geobot 46(4):303–325

R Core Team (2015) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL http://www.R-project.org/

Rabitsch W (2007) Rote Listen ausgewählter Tiergruppen Niederösterreichs – Wanzen (Heteroptera), 1. Fassung 2005. Amt der Niederösterreichischen Landesregierung, Abteilung Naturschutz & Abteilung Kultur und Wissenschaft, St. Pölten

Roesti C, Keist B (2009) Die Stimmen der Heuschrecken. Haupt, Bern

Sepp K, Mikk M, Mänd M, Truu J (2004) Bumblebee communities as an indicator for landscape monitoring in the agri-environmental programme. Landsc Urban Plan 67:173–183

Stoutjesdijk P, Barkman JJ (2014) Microclimate, vegetation & fauna. KNNV Publishing, Zeist

Strauss G (2010) CORISA Wanzenabbildungen. Biberach. www.corisa.de

Strijker D (2005) Marginal lands in Europe—causes of decline. Basic Appl Ecol 6(2):99–106

Tappeiner U, Cernusca A (1993) Alpine meadows and pastures after abandonment. Results of the Austrian MaB-programme and the EC-STEP project INTEGRALP. Pirineos 41:97–118

Tasser E, Tappeiner U (2002) Impact of land use changes on mountain vegetation. Appl Veg Sci 5(2):173–184

Tasser E, Walde J, Tappeiner U, Teutsch A, Noggler W (2007) Land-use changes and natural reforestation in the Eastern Central Alps. Agric Ecosyst Environ 118(1):115–129

Uchida K, Takahashi S, Shinohara T, Ushimaru A (2016) Threatened herbivorous insects maintained by long-term traditional management practices in semi-natural grasslands. Agric Ecosyst Environ 221:156–162

Uchida K, Ushimaru A (2014) Biodiversity declines due to abandonment and intensification of agricultural lands: patterns and mechanisms. Ecol Monogr 84(4):637–658

Von Hagen E, Aichhorn A (2014) Hummeln: Bestimmen, ansiedeln, vermehren, schützen. Fauna-Verlag, Nottuln

Wachmann E, Melber A, Deckert J (2004) Die Tierwelt Deutschlands. Vol.75. Wanzen Band 2 Cimicomorpha. Goecke & Evers, Keltern

Wachmann E, Melber A, Deckert J (2007) Die Tierwelt Deutschlands. Vol.78. Wanzen Band 3 Pentatomorpha I. Goecke & Evers, Keltern

Wagner E (1952) Blindwanzen und Miriden. Die Tierwelt Deutschlands und der angrenzenden Meeresteile 41. Gustav Fischer, Jena

Wagner E (1966) Die Tierwelt Deutschlands und der angrenzenden Meeresteile nach ihren Merkmalen und nach ihrer Lebensweise. Wanzen oder Heteroptera I. Pentatomorpha, vol 54. Fischer, Jena

Wagner E (1967) Die Tierwelt Deutschlands und der angrenzenden Meeresteile nach ihren Merkmalen und nach ihrer Lebensweise, vol 55. Wanzen oder Heteroptera II. Cimicomorpha, Fischer, Jena

Westphal C, Steffan-Dewenter I, Tscharntke T (2006) Bumblebees experience landscapes at different spatial scales: possible implications for coexistence. Oecologia 149:289–300

Wiezik M, Svitok M, Wieziková A, Dovčiak M (2013) Shrub encroachment alters composition and diversity of ant communities in abandoned grasslands of western Carpathians. Biodivers Conserv 22(10):2305–2320

Williams PH (1988) Habitat use by bumblebees (Bombus spp.). Ecol Entomol 13(2):223–237

Wood TJ, Holland JM, Goulson D (2016) Providing foraging resources for solitary bees on farmland: current schemes for pollinators benefit a limited suite of species. J Appl Ecol 54:323–333

Zurbrügg C, Frank T (2006) Factors influencing bug diversity (Insecta: Heteroptera) in semi-natural habitats. Biodivers Conserv 15:275–294

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna (BOKU). Thanks to Gerlind Lehmann, Thomas Zuna-Kratky and Martin Riesing for advises on the acoustic detection of grasshoppers and to Alexander Bruckner for statistical advises. Thanks to Mathias Hofmann and Jörg Clavadetscher for help on study site selection in Val Müstair and to Josef Türtscher for help on study site selection in Großes Walsertal. Thanks to Norbert Schuller for the provision of working materials and the lively exchange of ideas. Special thanks to all the farmers and land owners for their permission to conduct investigations on their meadows. This study was supported by the Austrian Academy of Sciences (project: Healthy Alps). All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Walcher, R., Karrer, J., Sachslehner, L. et al. Diversity of bumblebees, heteropteran bugs and grasshoppers maintained by both: abandonment and extensive management of mountain meadows in three regions across the Austrian and Swiss Alps. Landscape Ecol 32, 1937–1951 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-017-0556-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-017-0556-1