Abstract

Organic–inorganic hybrid materials, prepared via chemical synthesis route or physical blending of functionalized nanofillers within polymer matrix, have gained an increased attention in the recent years. Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) nanoparticles, due to their nanometer size and functionalization possibilities, are applied as effective modifiers—both chemical and physical, for polymer matrices, including polyurethanes (PU). In this work, we describe the synthesis and processing of polyurethane/POSS hybrid nanocomposites and discuss the influence of POSS moieties on the thermal properties of PU matrices. Glass transition, the crystallinity of the soft phase, as well as the order–disorder transitions are affected by the incorporation of POSS in the polyurethane structure. Direct polymer-POSS interaction, or -indirect—due to the suppression or enhancement of microphase separation by the POSS moieties are discussed in terms of topology of the polymeric structure with the key role of POSS functionalization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Polyurethanes (PUs) are widely used in different industrial sectors due to their light weight and excellent thermal insulation. However, thermoplastic polyurethanes (TPUs) have lower modulus and strength when compared to metals and ceramics [1], which may make PU plastics less attractive as engineering materials. An effective way to improve mechanical properties is by reinforcing the PU matrix with fillers, such as platelets, fibers or nanoparticles. Enhancement of a certain physical property of TPU by incorporating macro-sized particles often increases processing costs [2]. That’s why, a new class of hybrid materials composed of polymers into which nanosized inorganic particles are dispersed, could produce desirable structural and functional properties without high processing costs and without compromising other valuable properties. Nanoparticles impart many functional properties, and PU macromolecules provide structure and processability [3,4,5,6]. Numerous studies showed that nanometer-sized fillers have a large surface-area-to-volume ratio and could be easily dispersed in a PU matrix, hence facilitating the enhancement of a desired property, such as barrier property, heat resistance, modulus, strength and flammability [7, 8].

In the technology of nanocomposites the degree of dispersion is a critical factor. Moreover, in the case of copolymers—as are polyurethanes—the targeted placing of nanoparticles in one of the two phase-separated components is often beneficial for the tailoring of properties. Both issues are facilitated by the so-called nanobuilding block, i.e., using functional reinforcing moieties which react with the monomers or macromonomers, becoming thus parts of the macromolecular chain itself.

Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes (POSS) are a family of molecules, very appropriate for this approach. They consist of a siliceous core with size less than a nanometer, typically cubic with silicon atoms on the vertices and oxygen on the edges. Their particularity is that on every Si atom, an organic ligand or vertex group is attached; in that respect POSS are organic–inorganic materials. The vertex groups may contain one or more reactive groups which allow covalent bonding to the host matrix or may be non-reactive, properly chosen to tune physical compatibility with the host polymer.

From the chemical point of view, polyurethanes are the copolymers whose constituent units bind to each other with the urethane bond. In the simplest case, the urethane bond is formed by the addition reaction of a diisocyanate group and a hydroxyl one [9]. This reaction is quite fast and very intense, so polyurethane materials are easy to make from the chemical point of view. In addition, recently environmental and safety concerns motivated the design of polyurethane materials from other kinds of monomers and macromonomers [10]. Elastomeric polyurethanes consist of the so-called soft segments, typically an OH terminated flexible polyether or polyester, and the hard segments, typically a sequence of a diisocyanate and a short diol. Proper selection of those monomers and macromonomers, as well as small alterations, i.e., using multifunctional polyols or isocyanates, allows for an enormous flexibility in the final materials in terms of chemistry, chain architecture, etc.

It is also obvious now that a proper selection of the POSS substituents, e.g., with ligands with hydroxyl or isocyanate functionality will allow for easy and effective chemical incorporation of the POSS moieties in the polyurethane structure and—most important—on the desired location in the chain. The POSS particles could be incorporated into the PU by different methods such as copolymerization, grafting or melt blending methods. The melt blending method with TPU has the advantages that compounding could be carried out by using traditional technology and thereby TPU/POSS nanocomposite with significant properties could be obtained. Incorporation of POSS nanoparticles in the polymer matrix could improve the processability of TPU, the use temperature and oxidation resistance, as well the thermooxidative stability [11].

Hence, in this review, we describe in detail the chemical and processing methods by which POSS can be incorporated in polyurethane matrices, in laboratory and industrial scale. Moreover, we will explore the effects they have on the thermal transitions of polyurethane matrices, paying attention to the complex underlying mechanisms behind them.

Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes (POSS)—definition and architecture

The term silsesquioxanes refer to molecules, which have the basic composition of RnSinO1.5n, where R-group—the so-called vertex group is a hydrogen atom, an inert organic group such as alkyl, phenyl or isobutyl or even carry a reactive group such as hydroxyl, carboxyl or an unsaturated bond. POSS feature a Si atom at each vertex of a polyhedral cage. The shape of the cage is typically cubic (n = 8) but cages of 6–12 vertices are often noted. The Si vertices are interconnected with–O–linkages. The R-group is attached to each of the Si atoms and is pretty much tailored to the specific application. The backbone of those cages substituents determines to a large extent the compatibility of these molecules to the polymer, possible chemical reactions and thus the final structure of the POSS composite. It will directly or indirectly alter, to an extent, the thermal, barrier, flammability reduction and other physical properties [12,13,14,15,16,17,18].

Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane compounds with well-defined cube-like structures have been extensively researched as the nanoscale building blocks of organic–inorganic hybrid materials. Optically transparent films of a single POSS compound are rarely formed without crosslinking reagents because of their high symmetry and crystallinity. Araki and Naka reported that dumbbell-shaped POSS derivatives linked by simple aliphatic chains can be used, depending on their aliphatic chains, to form optically transparent films [19, 20]. Those dumbbell-shaped POSS compounds are the first examples of optical transparent POSS films exhibiting thermoplastic properties. As crystallinity and thermal characteristics of POSS molecules are very much dependent on their organic substituents, further studies are required to develop various thermoplastic POSS derivatives with the desired properties. Mitsudo and coworkers synthesized dendritic POSS derivatives for application to homogeneous catalyst supports [21]. Wang et al. [22] also synthesized a star-shaped POSS supramolecules. The examples of star- and dumbbell-shaped molecular architecture are presented in Fig. 1.

Examples of star- and dumbbell-shaped molecular architecture of silsesquioxanes: a dumbbell-shaped isobutyl-substituted C2-linked POSS ((1,2-bis(heptaisobutyl-T8-silsesquioxy)ethane) IBDE); b C3-linked POSS ((1,3-bis(heptaisobutyl-T8-silsesquioxy)propane) IBDP); c C6-linked POSS ((1,6-bis(heptaisobutyl-T8-silsesquioxy)hexane) IBDH); d star-shaped POSS

Silsesquioxane cages are synthesized by hydrolytic condensation, where the polyhedral Si–O core (of completely condensed nanofiller cages) is formed by a hydrolytic condensation of trifunctional monomers. These monomers have usually structure of YSiX3, where Y is a suitable organic substituent that will form the R-group, and X is a highly reactive substituent (Cl or alkoxy group) [23]. Incompletely condensed cages with hydroxyl groups in the so-called missing corner have also attracted some interest both as standalone particles, to be introduced in polymer matrices, and as precursors for fully condensed backbones with a differing eighth vertex group.

It should be noted that reactions of trisilanols with ligand-deficient trivalent-metal complexes, usually lead to more complex structures because of the inability of these trisilanols to support trigonal planar coordination environments [23]. Silsesquioxanes, such as other highly symmetric molecules, including dendrimers, interacts with the matrix host in the three dimensions of the surrounding space. The characteristic size of the POSS particle is usually comparable to the dimensions of polymeric segments but shows nearly double typical intermolecular spacing. Incorporation of silsesquioxane moieties into linear polyurethane chains or networks could modify the local molecular interactions, segmental mobility and molecular topology [24]. In that respect, POSS fill the gap between conventional nanoparticles and large oligomers. In the following, we will explore how this double nature affects in an interesting and complicated way the properties of the polymers.

Polyurethane/POSS nanocomposites—synthesis and processing

The building blocks used to obtain PUs, both thermoplastics and thermosets, are diisocyanates and polyisocyanates, as well as compounds with a broad array of molar masses containing two or more hydroxyl groups. The isocyanate (–N=C=O) and hydroxyl (–OH) groups react forming the urethane group [25, 26]. Two general methods are very common for the production of PU/POSS hybrid systems: melt blending and chemical synthesis.

According to the number of groups at the eight corners of POSS molecules, chemical synthesis can be divided into copolymerization, grafting, and crosslinking. POSS as organic/inorganic hybrid material has the special nature of surface effect and nano quantum size effects. When incorporated into polyurethane, the nanoscale POSS improves the thermal stability, water resistance, flame-retardant behavior and mechanical strength of the polyurethane.

In melt blending, POSS and polyurethane are mixed by physical blending through a solution method or melt method. Usually, TPU pellets are mixed in blending device in appropriate conditions such as high temperature above melting temperature and with special selected speed of screws. For example, in reference [27] melt method was used to mix a TPU and POSS using a Brabender mixer running in nitrogen flow at 50 rpm for 10 min. Although physical blending is simple, the solubility parameters of polyurethane and POSS are different. Nanoscale POSS easily forms aggregates, which lead to macroscopic phase separation and have a negative effect on the modification [28, 29].

As second option consists of POSS incorporation into the main chain, with conventional chemical methods. This is mainly carried out in a one or two step process, following standard polyurethane chemistry procedures. In this case, functionalized POSS, usually containing one or more OH groups participate in the reaction and form urethane bonds with diisocyanates leading to often complex architectures which we are going to describe in the following. The reaction may take place in the presence of small amounts of a suitable solvent such as tetrahydrofuran (THF) [30], N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) [31], methyl ethyl ketone (MEK) [32], dimethylacetamide (DMAC) [33] or even in solvent-free environments [34, 35] in which case the polyol dissolves the other components (diisocyanate and POSS). The selection of the solvent is obviously crucial for the effective reaction and good dispersion of the POSS moieties. Following the standard PU synthesis procedures, the reaction should be carried out in an inert gas to avoid side reactions of the diisocyanates with water.

According to the type and number of functional groups at the eight corners of POSS, the structures of the hybrids formed by copolymerization can be divided into four architectures of PU/POSS composites [36]:

-

Non-reactive POSS molecules dispersed in PU matrix as filler, POSS monomer containing only one reactive group. The suspension type of POSS/PU nanocomposites mainly used the T8X7Y type of POSS, where X is an inert functional group, Y is a functional group with two hydroxyl groups or two amino groups and POSS suspends in the polyurethane segment by the prepolymer method.

-

Bead type—POSS core with two reactive functional groups is incorporated in the backbone of PU.

-

Pendant type—POSS molecules with a single reactive functional group and can be polymerized as a monomer or comonomer.

-

Network or crosslinked type—synthesized by the polymerization of a POSS cage containing multifunctional polymerizable groups which will form three-dimensional networks. To obtain these type of structure, it could be used amino-POSS, hydroxy-POSS, isocyanate-POSS, epoxy-POSS or vinyl-POSS nanoparticles [35, 37,38,39,40].

In Fig. 2, architectures classification of PU/POSS composites, depending on the type of POSS, was presented.

General architectures of PU/POSS composites [16]. Copyright 2011. Reproduced with permission from Elsevier

Among various works on PU/POSS materials, it’s worth mentioning the Hsiao et al. work [41]. This time polyurethane/POSS nanocomposites were prepared through the reactions of POSS derivative featuring one corner group substituted by either a 3-(allylbisphenol-A) propyldimethylsiloxy or a hydridomethylsiloxy group. A polyurethane system using an organic biodegradable PDLA soft block and an inorganic diol-POSS hard block was obtained by Mather et al. [42]. Pielichowski’s group in a series of publications [35, 39, 43,44,45,46] synthesized and studied polyurethane/POSS nanocomposites using a methylene diphenyl isocyanate (MDI)—poly(tetramethylene ether glycol) PTMEG-based polyurethanes with 1,4-butanediol as chain extender. In this series, POSS particles with different number and configuration of functional groups were used leading to a plurality of chain architectures. Turri et al. [47, 48] synthesized a linear ionomeric PU/POSS nanocomposite through a diol-functionalized POSS macromer. More recently Huang et al. [49, 50] reported on systems based on natural resources, i.e., castor oil and soy-castor oil, combined with isophorone diisocyanate and a double-decker POSS moiety.

Hydroxyl functionalized POSS moieties are far more common in the literature; however, systems with isocyanate functionalized POSS have been also reported: Neumann et al. [51] and Mya et al. [52] synthesized a POSS macromer with eight reactive isocyanate groups ((NCO)8-POSS) through hydrosilylation of m-isopropenyl-R,R-dimethylbenzyl isocyanate with Si–H bonds of Q8M8H. The moieties were then reacted and bound with each other, with appropriate polyethers.

The biggest obstacle during the preparation of PU/POSS nanocomposites is the aggregation tendency of the silsesquioxanes. As they possess high specific surface area, POSS may aggregate between themselves very easily, and the aggregation may act as defect center and sometimes leads to worsen the thermal and mechanical properties of the polyurethane. The main question is, how we should disperse POSS nanoparticles especially at higher loading up to 10 wt.%. Nowadays, different methods are used to disperse the silsesquioxanes into the polymer matrix, such as shear mixing, mechanical mixing, in situ polymerization and sonication, but some of them could be very complicated. In order to get the necessary dispersion of POSS, the surface of nanoparticles should be modified and/or suitable compatibilizer should be used. High dispersion is not easily achieved, but when the POSS nanoparticles are homogeneously dispersed in the PU matrix, the full potential of these nanomaterials could be exploited. Regardless of the preparation approach, the dispersion and self-assembly of POSS moieties inside the PU host are the key factors affecting the final physicochemical properties. If the POSS–PU interaction is favorable compared to the POSS–POSS interaction, silsesquioxane moieties will disperse well; otherwise, nanoparticles will aggregate. Unlike a filled hybrid system or blend, however, proper functionalization of POSS may limit aggregation due to covalent attachment to the PU backbone, or an appropriate choice of non-reactive R-groups, may prevent aggregation beyond a scale of ca. one radius of gyration [53,54,55,56,57]. The resulting effect on physicochemical properties will vary with the silsesquioxane moieties dispersion or the aggregation level. Therefore, it is of crucial importance to understand the nanostructure—property—processing relationships for given hybrid systems in order to successfully tailor properties to intended applications [53,54,55,56,57]. Most inorganic ceramic or silica particles are immiscible in organic systems because of poor specific interactions within these organic–inorganic hybrid systems and the negligibly small combined entropy contribution to the free energy of homogenization. Specific intermolecular interactions such as: interactions include hydrogen bonding, dipole–dipole interactions and acid/base complexation are required to enhance the miscibility of PU matrix with inorganic particles [58].

The processing routes of typical polymer nanocomposites reinforced with polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes were described briefly in reference [59].

Depending on the form of occurrence of polyurethane matrix (resin, liquid substrates and thermoplastic pellets) we distinguish several methods of processing. Polyurethanes and its composites could be processing with some main techniques such as:

-

direct skinning,

-

filament-winding,

-

lamination,

-

pultrusion,

-

reaction injection molding (RIM),

-

rebounded foam and spray foam.

The direct skinning process is mainly a combination of TPU/POSS processing and injection molding. It brings injection molding and reaction molding together in one device to give the surface of the component a more opulent appearance. The clue of this technique is that the thermoplastic substrate produced conventionally is not demolded after injection molding but remains on the mold core after the mold is opened. The highly crosslinked thermoset of PU/POSS composites obtained in this way displays not only excellent heat stability but also very good chemical resistance [17, 60, 61].

Lamination production process is based on special slicing devices long PU/POSS blocks which are cut to sheet-products with the desired thicknesses of 2–5 mm at different length and then rolled for semi-finished product. In the next step, semi-finished product is used to the lamination of the foams with the contour cutting and sewing. This technique is used mainly to combination with different textiles, leather or other trim materials [62,63,64].

Pultrusion is a major manufacturing technology for the continuous production of POSS reinforced thermoplastics polyurethanes with structural shapes despite that these techniques are often used for PU hybrids with glass fiber. The pultrusion process is achieved by a series of steps that are geared toward creating a quality composite material like:

-

continuous filler reinforcement, where rolls of filament or fabric work are used to keep strength across the profile of the product and the material is fed into the machinery to begin the process,

-

preforming guides where the composites material spools and reinforcements are threaded into a machine known as a tension roller,

-

impregnation and resin bath where in impregnating stage of the pultrusion may utilize different types of resin, such as polyester and vinylester. In this step pigments could be added into mixture to enhance the product’s appearance. Catalysts that could also assist in curing or solidifying the profile also find their way into the mixture.

-

exposure to heat source where the product enters a hot, steel-forming die. This hot die is pivotal to the pultrusion process as it creates the hard shape of the composite material.

-

caterpillar pull mechanism and cutting saw there the cured profile is now advanced along a pull mechanism. The profile meets the cutting saw, where it is cut into appropriate lengths [60,61,62,63, 65].

Injection molding or blending is a common process for polyurethane/silsesquioxanes composites. In many applications, the mold release agent is applied to the mold, and then a paint coating is applied over the mold release agent. Then, the mold is closed and the injection take place. The final hybrid product is removed fully painted. A closed mold usually contains some form of channels after the mixer gate designed to improve the laminar flow of injected POSS systems at the entrance to the mold. Injection molding differs from the open pour in contact angle and mixing motion, which leads to different stresses on the mold release agents. Other type of injection molding processing is reaction injection molding (RIM). In RIM process, a high-pressure impingement-mixed two component stream is used into a mold or cavity, where nanoparticles are dispersed in one of them with lower viscosity. These liquid components—an isocyanate and a polyol—are developed in two-part formulations, which are often called polyurethane RIM systems. As it is presented in Fig. 3, when injection of the liquids into the mold begins, the valves in the mix head open. The liquid reactants enter a chamber in the mix head at pressures between 100 and 200 bar, and they are intensively mixed by high-velocity impingement. From the mix chamber, the liquid then flows into the mold at approximately atmospheric pressure. Inside the mold, the liquid undergoes an exothermic chemical reaction, which forms the polyurethane polymer in the mold. Shot and cycle times vary, depending on the part size of filler and other components and the polyurethane system used. An average mold for an elastomeric part may be filled in one second or less and be ready for demolding in 30–60 s. Special extended gel-time polyurethane RIM systems allow the processor enough time to fill very large molds using equipment originally designed for smaller molds [61,62,63, 66,67,68,69,70].

Release agents used in RIM processes need to be able to resist movement and disruption during injection and still be mobile enough to produce a slippery surface, once the PU/POSS system has been cured. Additionally, the material composition of the polyurethanes can interact differently with the mold release agents. That’s why concentration of POSS particles and its homogeneity come into play with respect to the amount of material that is left behind by the mold release agent. A low amount of residual material left in the mold is highly desirable to reduce the cleaning frequency of the mold. Depending on how the PU or PU/POSS RIM system is formulated, the parts molded with it can be a foam or a solid, and they can vary from flexible to extremely rigid. Thus, polyurethane RIM processing can produce virtually anything from a very flexible foam-core part to a rigid solid part, with specific gravities ranging from 0.2 to 1.6 [61, 63].

Incorporation of silsesquioxanes into polyurethane matrix give these composites barrier properties, thus these hybrid materials have much better thermal insulation than conventional PU foams. The PU/POSS line of spray polyurethane foam insulation and roofing systems could provide a high R-value and the ability to reduce air intrusion, accumulation, radiative heat transfer and air movement. The application technology allows the spray PU/POSS foam to expand, filling cracks, crevices and voids. This creates a “seamless” air barrier system that provides exceptional building envelope performance. In order to utilization of PU wastes, there is some type of recycling process used called rebounded foam processing. In this technique, PU wastes are shredded into flakes, mixed with nanofiller and then sprayed with an isocyanate-terminated prepolymer and chemically bound to the required grade of foam using a superheated steam injection process. Despite intense efforts to develop alternative technologies such as hydrolysis, glycolysis, adhesive pressing or even grinding into powder producing hybrids rebounded foams is the method of material recycling with the greatest technical and economic potential [62, 63, 70].

Polyurethane formations could be monitored in situ to obtain the structural information during the gelation process. This technique investigates the connectivity of polyurethane as a function of time, temperature and composition by measuring storage and loss modulus during gelation. The gel point of polyurethane during the gelation process could also be obtained by rheological experiments. This characteristic moment is reached at a critical degree of crosslinking, when the largest connected cluster diverges to infinity [71].

For the preparation of PU nanocomposites reinforced with POSS by processing in melt, mainly a Brabender-type mixer was applied [27]. According to this reference, thermoplastic polyurethane was mixed in melt with 10 wt.% of poly(vinylsilsesquioxane) using a Brabender device operating at 50 rpm for 10 min at 180 °C under nitrogen flow. Mass loss calorimetry results revealed a large reduction of the maximum peak of heat release rate (PHRR) in thermoplastic composites as compared to pure TPU. The intumescent material has been found to be composed of ceramified char made of silicon network in a polyaromatic structure. This intumescent PU nanocomposite acts as a thermal barrier at the surface of the substrate limiting thus the heat and mass transfer as evidenced by lowered HRR.

There is also known novel method to prepare PU/POSS hybrids by melt reactive blending, proposed by Monticelli et al. [66]. This practical approach is based on the reaction between OH groups in functionalized oligomeric silsesquioxanes molecules and the isocyanate functional groups, which could formed during the melt blending through a controlled scission of the thermoplastic polyurethane. These nanosystems were then prepared by mixing at 220 °C under inert gas atmosphere for 10 min the neat polymer and trans-cyclohexanediolisobutyl or octaisobutyl POSS at concentrations up to 20 wt.%. Results showed an increase in glass transition temperature and better surface water wettability—water contact angle decreased from 95° for pure matrix to 70° in nanosystems with 10 wt.% of nanofiller.

Lopes et al. [32] also proposed novel method to processing PU/POSS composites and additionally explained how changes in the thermal behavior reflect in rheological properties of dispersions systems. The addition of silsesquioxanes nanoparticles showed a clear tendency toward higher intrinsic viscosities as the amount of the chain modifier was increased. Samples tended toward a linear pseudo-plastic behavior, with a higher amount of nanofiller leading to higher intrinsic viscosities at all shear rates evaluated. Nanda et al. [68] confirmed similar behavior in polyurethane hybrid systems, as well. They observed that the incorporation of POSS into the TPU backbone produced a significant change in the viscosity. The viscosity increases linearly with nanoparticles concentration, corroborating the reinforcing efficiency of nanofiller in the matrix backbone. Authors observed that the viscosity of PU/POSS composites at low frequencies was significantly higher than that obtained at high frequencies. These results suggested that the viscosity strongly depends on frequency, revealing the non-Newtonian behavior of TPU/POSS hybrid systems, and POSS particles restraint the movement of flexible domain probably by the formation of silicate layers. Besides, Nanda et al. [68], noted that the incorporation of POSS with eight OH functional vertex groups in polyurethane films resulted in higher thermal stability and crosslink density. Aqueous polyurethane dispersions with functionalized POSS were prepared through homogeneous solution polymerization by the use of acetone as the initial polymerization solvent enabled the facile incorporation of both diamine- and diol-functional POSS monomers (3-(2-aminoethyle)amino)propyl-heptaisobutyl-POSS and 2,3-propanediol propoxy-hep-taisobutyl-POSS, respectively).

Thermal properties of PU/POSS hybrid systems

Up to now, it should be clear that polyurethanes, even in themselves, are quite complex systems and the possible combinations of macromolecular components, flexible segments, diisocyanates and chain extenders, can give a large number of possible systems that differ in chemical properties, architecture, rigidity, mechanical modulus, and of course molecular mobility. The situation gets even more complex given the extended number of available POSS moieties and the various techniques used for their incorporation in the matrices.

Before discussing the effects of POSS on the thermal properties, we would like to comment briefly on some principles that govern the thermal behavior of polyurethanes, and apply to virtually all members of the family. We remind here that as a general rule, the hard segments tend to segregate and form hard microdomains, often crystalline. Those hard microdomains are distributed in a soft phase consisting predominantly of soft segments, but also contain a non-negligible amount of diluted hard segments. The final micromorphology depends strongly on the chemical nature of the components, the geometry of the chain, and the thermal history of the material. The resulting degree of microphase separation is crucial to the thermal properties to be discussed immediately.

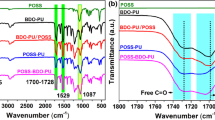

In principle, the thermal transitions expected in a polyurethane system are the glass transitions of the soft and hard microdomains, the melting/crystallization of the soft component where possible, and the order–disorder transition, i.e., the dissolution of hard segments in the soft matrix (Fig. 4).

Reversing (continuous lines) and non-reversing (dashed lines) components of the modulated DSC signal of a model polyurethanes and its hybrids with crosslinking POSS moieties, in a broad temperature range. The curves are typical of segmented polyurethanes: The glass transition of the soft domains is observed as a step in the reversing component at subambient temperatures, while at higher temperatures the order disordered transition is evident as a series of endotherm peaks, mainly in the non-reversing component [40]. Copyright 2015. Reproduced with permission from American Chemical Society

Glass transition

Being essentially copolymers, phase-separated polyurethanes exhibit in principle two glass transitions: one of the soft phase and in principle one of the hard microdomains. The latter though may be very weak, practically undetectable, especially in the case of aromatic diisocyanates because of the rigidity of the chains and possible strong crystallinity. This one has rarely been studied in the literature [72]. However, a broad endotherm peak between the glass transitions of the bulk hard and soft segments is often related to the glass transition or softening of the hard microdomains.

The soft phase glass transition though has attracted a lot of attention because it is essentially the main transition of the system. Its temperature T g lies, as expected, above the T g of the soft segments. The temperature rise of T g is discussed usually in terms of slowing of dynamics because of the diluted hard segments, according to the mixing laws which apply to blends and copolymers, i.e., a poorly phase-separated polyurethane will have a higher soft phase T g than a well phase-separated one, all other parameters (chemistry—composition) being the same [73,74,75].

The effect on POSS on the molecular dynamics of the soft phase is a challenging question. So far, investigations by us and others, on which we are going to refer in detail in the following, has shown rather increasing trend of the soft matter glass transition temperature T g with increasing POSS content. An increasing T g is associated with slowing of dynamics. However, the extent of this increase and the mechanisms driving it depend strongly on the type of the incorporated POSS, the chain architecture and of course the amount of POSS diluted in the soft phase, and their degree of dispersion. That said, we would like to point out that the mechanisms by which POSS affect the dynamics of any polymer—not only copolymers like PUs—are very complex [18]. The reason is that POSS themselves are moieties with size smaller than a nanoparticle and comparable to an oligomer: their siliceous core is of size ~ 0.5 nm [76], smaller than that of a conventional filler. It is thus expected and observed that moieties which cannot crystalize present their own glass transition [18, 77]. So, if the moieties dilute well in a polymer matrix they behave as simple diluents in the sense of the mixing models like that of Fox [78]. On the other hand, most of the moieties are strongly crystalline. In this case, they tend to form crystallites, often of the size of nm which essentially behave as nanoparticles, and affect dynamics in the same way conventional nanofillers do.

Returning to the specific question of polyurethanes with POSS, Fig. 5 summarizes our investigations on a polyurethane matrix with methylene diphenyl isocyanate (MDI) and butanediol (BD) forming the hard domains, and poly(tetramethylene ether glycol) with M w ~ 1400 forming the soft domains. It shows the rise of calorimetric T g on addition of various POSS with respect to the matrix. In this series of investigations, the POSS substituents have been incorporated covalently in three distinctively different chain architectures. Namely, they have been bonded as (1) pendent groups on the hard domains, using the POSS substituents with one bifunctional ligand [34, 79] (2,3-Propanediol)propoxy-heptaisobutyl POSS), (2) as part of the main chain, forming a bead-like copolymer, using an open cage with OH groups attached to the two “disconnected” Si atoms [35] (disilanol octaisobutyl POSS), and (3) as crosslinks, forming a polyurethane network, using an octafunctional moiety [45] (octa(3-hydroxy-3- methylbutyldimethylsiloxy) POSS). Note that all inert vertex groups in these cases are isobutyl, which in principle drives to strong crystallization. A fourth system was prepared by blending a non-functional moiety during the polyurethane reaction. A PEG (M w ~ 600) substituted moiety was chosen for this investigation, because octaisobutyl-substituted POSS were immiscible to the system. In all the systems, the POSS content varied up to 10 wt.% with respect to total polyurethane mass.

The pendent POSS cause a moderate but consistent increase in T g (Fig. 5) by a few degrees. A comparative study of the specific heat increase at T g as well as dielectric and morphological properties [79] showed that both direct and indirect effects drove this slowing of dynamics. For polyurethane with shorter segments (PU1000), POSS increased miscibility of the hard domains in the soft phase, while at larger segment lengths, POSS crystallites, suppressed the chains which were anchored on them and even formed a rigid amorphous fraction.

In the PU copolymer with POSS incorporated on the chain as “beads”, the soft calorimetric T g remained practically unaffected (Fig. 5). However, a closer investigation by dielectric methods showed that a slower segmental relaxation, with weak, if not nonexistent, thermal footprint was severely enhanced on addition of POSS (Fig. 6). This relaxation present (but weaker) in all the systems, including the matrices, is due to soft chains anchored on bulky structures (hard domains, POSS crystallites, soft segment crystallites). The morphological investigation indeed showed the existence of domains consisting of PU chain extended practically only with POSS.

Dielectric spectra of a polyurethane and its hybrids with the POSS cage along the chain contour, as “beads,” at − 15 °C. A slow relaxation α′ (10 Hz), attributed to segmental dynamics of anchored chains accompanies the slower main α relaxation (10.000 Hz) corresponding to the dynamic glass transition. The locations of the two relaxations are shown for a representative sample [35]. Copyright 2013. Reproduced with permission from American Chemical Society

The only prominent increase occurred with the crosslinking moiety. At a first glance, this is hardly surprising: Crosslinking is expected to restrict dynamics. However, the Young’s modulus at the rubbery phase decreased by an order of magnitude despite the crosslinking. This was attributed to the severe reduction of microphase separation, which was confirmed also by SAXS and other methods [45]. In this view, it is concluded that the hard domains are better reinforcing agents as compared to the POSS moieties.

Finally, the PEG-POSS blended in the system, caused even an acceleration of dynamics as manifested by a decrease in T g. We believe here, that this was the effect of the flexible PEG chains well diluted in the soft phase according to the mixing laws [39].

The aforementioned studies show the crucial role of the chain architecture and the mode of incorporation of POSS. Despite the chemical similarity of all the systems the behavior of dynamics with incorporation of POSS is much different, not only in magnitude but also in the underlying mechanisms. A point to stress though is that the aforementioned slow dynamics (α′ relaxation), with the strong dielectric but weak thermal response, seem to be very similar for chains anchored on much different rigid structures.

In addition, the role of the chemistry of the bonding was demonstrated in [79]. In this work, POSS were bonded with urea bonds as opposed to urethane. Urea groups have a much stronger tendency to aggregation; hence, the microphase separation was promoted to some extent, and counteracted the slowing down of dynamics. The counteracting phenomenon was so strong that for longer segments, the calorimetric T g even decreased by a few degrees. Interestingly, the slow dynamics α′ were more intense in this system.

In a very similar PTMG-MDI-BD polyurethane, pendent POSS, but with cyclopentyl inert vertex groups, caused an increase in the calorimetric T g very similar in magnitude to the one by POSS with isobutyl inert groups. Here again, a weakening of microphase separation was observed [30].

Slightly more intense increase in T g was reported for a polycaprolactone-based PU with pendent POSS substituting their macrodiol with pendent POSS similar to those in [34]. More prominent increase in T g was reported for systems where POSS with a cyclohexyl ring on their sole reactive vertex group, were pendent on a polypropylene oxide (PPO)–MDI–BD system [81]. The inert vertex groups were isobutyl, as in the previous works. The POSS here substituted part of the macrodiol as opposed to the previous system where POSS substituted part of the chain extender. TEM here showed an excellent dispersion, and DMA a weakening of the hard segment-related phenomena; hence, we believe that the increase here is rather due to improved microphase mixing.

The same particle was introduced in a polybutadiene–isophorone diisocyanate–BD system by substitution of the chain extender by a sol–gel technique [82]. Although the dispersion was in the order of micrometers, the glass transition temperature increased significantly. Increase in T g was reported also for a system moderately crosslinked by a trisilanol open-cage moiety [83]. Despite the crosslinking, the authors based on the relative stability of the activation energy of the dynamic glass transition conclude that the reduction of mobility is related to nanocrystals formed by the POSS moieties.

Recently, Huang et al. showed that the mechanisms of POSS may be concentration dependent: In a castor oil-based system incorporating a double-decker POSS, less than 1.5 wt.% of POSS reinforced the system, leading to an increase in T g by more than 30 K, as compared to the matrix; however, beyond that concentration aggregates were formed and acted as plasticizers, increasing the mobility of the system and decreasing T g [49].

Crystallization of the soft phase

Similar to the glass transition the degree of microphase separation governs to some extent the ability of the soft segments to crystallize, provided that they are crystalline in their bulk form. The soft segment polyethers or polyesters in bulk have melting temperatures below 100 °C. If the PU segments are short, then the hard segments that intervene in the chain, introduce a disorder and crystallization is not possible. However, longer segments, typically of molar mass greater than 2000, can fold and eventually crystalize [73, 74]. The melting temperature and degree of crystallinity increase with the molar mass of the segments, reflecting an increase in the quality and size of the crystallites.

In our work, we have observed that POSS pendent on a PTMG-based polyurethane affect crystallinity in a way very much dependent on the nature of the chemical bond used for their incorporation on the chain [79]. The PU chain in this case contained a PTMEG chain of M w ~ 2000, which in bulk form crystalized 25 K below the melting temperature of the bulk PTMEG. POSS tethered on the chain with urethane linkage suppressed completely the crystallinity at content as low as 4 wt.%, as a result of the increased disorder—disruption of microphase separation. The POSS linked with urea bond though, improved the microphase separation, increased the purity of the soft phase and as a result, the crystallinity was greatly increased.

On the other hand, a new component in the system, unavoidably would introduce some disorder and therefore reduce the ability of chains to fold and organize themselves. In that respect, a suppression of crystallinity was observed also in polycaprolactone-based polyurethane elastomers, when the POSS substituents moiety with isobutyl as inert vertex groups was pendent on it [84]. This happened, albeit the polyurethane in this case was not phase separated, and no significant effect on glass transition by the POSS was observed.

Order–disorder transition

Maybe the most common transition of polyurethanes is the order–disorder transition observed at temperatures well above the glass transition of the hard domains. During this transition, the hard domains vanish and dissolve in the soft phase forming a homogeneous material. This transition is rather complex and happens in more than two steps [85]. It is usually discussed in terms of dissolution of the hydrogen bonding network between the urethane groups of the chain, and therefore it resembles a lot melting, albeit it is not always the case that the hard domain are actually crystalline. In calorimetric experiments, it manifests itself as a broad endothermic peak with multiple components.

In our investigation, we have observed that POSS bonded to the chain as pendent groups, using urethane linkages [79] did not impose any significant change in the temperature of the transition, but its enthalpy was moderately suppressed, indicating that the quality of the hard domains did not change, i.e., the POSS likely did not penetrate the hard domains. However, urea bonds were used for the covalent attachment, the hydrogen bonding increased and led to hard domains with higher dissolution temperature. Crosslinking POSS caused an increase in the temperature of one of the components of the transition but the other one remained unaffected [45]. The strength of the two however decreased with increasing POSS content. This can be attributed to the formation of less but sturdier hard domains. Finally, when the POSS where introduced as beads on the macromolecular chain, the components of the peak did not change position in the temperature domain but their relative intensity seemed to change significantly.

Conclusions

We reviewed in this work, the most common methods for the production of polyurethane–POSS hybrid elastomers, either by chemical synthesis or by melt blending. In this process, the importance of the degree and length scale of dispersion of the moieties, in the molecular level or in nanosized-crystals, was stressed. The methods for improving it were also discussed.

Several transitions occur in polyurethanes, namely the glass transitions of the hard and soft components, the crystallinity of the soft phase, as well as the order–disorder transition (also related to the melting of the hard domains). All of them—with the exception possibly of the hard domain glass transition—are effected by the incorporation of POSS in the structure. The effects are either due to direct polymer–POSS interaction, or -indirect—due to the suppression or enhancement of microphase separation by the POSS moieties. In this very complex interplay, the topology of the polymeric structure plays a key role and is governed by the functionality of POSS moieties.

References

Camargo PHC, Satyanarayana KG, Wypych F. Nanocomposites: synthesis, structure, properties and new application opportunities. Mater Res Mater Res. 2009;12:1–39.

Morgan A, Wilkie C. Flame retardant polymer nanocomposites. Hoboken: Wiley; 2007.

Balazs AC, Emrick T, Russell TP. Nanoparticle polymer composites: where two small worlds meet. Science. 2006;314:1107–10.

Lagashetty A, Venkataraman A. Polymer nanocomposites. Reson J Sci Educ. 2005;10:49–60.

Bockstaller MR, Mickiewicz RA, Thomas EL. Block copolymer nanocomposites: perspectives for tailored functional materials. Adv Mater. 2005;17:1331–49.

Winey KI, Vaia RA. Polymer nanocomposites. MRS Bull. 2007;32:314–22.

Iyer P, Mapkar JA, Coleman MR. A hybrid functional nanomaterial: POSS functionalized carbon nanofiber. Nanotechnology. 2009;20:325603.

Iyer P, Iyer G, Coleman M. Gas transport properties of polyimide–POSS nanocomposites. J Memb Sci. 2010;358:26–32.

Prisacariu C. Polyurethane elastomers: from morphology to mechanical aspects. Vienna: Springer; 2011.

Zhang K, Nelson A, Talley S, Chen M, Margaretta E, Hudson AG, et al. Non-isocyanate poly(amide-hydroxyurethane)s from sustainable resources. Green Chem. 2016;18:4667–81.

Romero-Guzmán ME, Romo-Uribe A, Zárate-Hernández BM, Cruz-Silva R. Viscoelastic properties of POSS–styrene nanocomposite blended with polystyrene. Rheol Acta. 2009;48:641–52.

Pan M-J, Gorzkowski E, McAllister K. Dielectric properties of polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS)-based nanocomposites at 77k. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2011;18:82006.

Lickiss P, Rataboul F. Fully condensed polyhedral oligosilsesquioxanes (POSS): from synthesis to application. In: Hill AF, Fink MJ, editors. Advances in organometallic chemistry. San Diego: Elsevier Academic Press; 2008. p. 1–116.

Shea KJ, Loy DA. Bridged polysilsesquioxanes. Molecular-engineered hybrid organic–inorganic materials. Chem Mater. 2001;13:3306–19.

Cordes DB, Lickiss PD, Rataboul F. Recent developments in the chemistry of cubic polyhedral oligosilsesquioxanes. Chem Rev. 2010;110:2081–173.

Kuo SW, Chang FC. POSS related polymer nanocomposites. Prog Polym Sci. 2011;36:1649–96.

Wu J, Mather PT. POSS polymers: physical properties and biomaterials applications. Polym Rev. 2009;49:25–63.

Raftopoulos KN, Pielichowski K. Segmental dynamics in hybrid polymer/POSS nanomaterials. Prog Polym Sci. 2016;52:136–87.

Araki H, Naka K. Syntheses and properties of star- and dumbbell-shaped POSS derivatives containing isobutyl groups. Polym J. 2012;44:340–6.

Araki H, Naka K. Syntheses of dumbbell-shaped trifluoropropyl-substituted poss derivatives linked by simple aliphatic chains and their optical transparent thermoplastic films. Macromolecules. 2011;44:6039–45.

Wada K, Watanabe N, Yamada K, Kondo T, Mitsudo T. Synthesis of novel starburst and dendritic polyhedral oligosilsesquioxanes. Chem Commun. 2005;41:95–7.

Wang X, Ervithayasuporn V, Zhang Y, Kawakami Y. Reversible self-assembly of dendrimer based on polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes (POSS). Chem Commun. 2011;47:1282–4.

Pielichowski K, Njuguna J, Janowski B, Pielichowski J. polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes (POSS)—containing nanohybrid polymers. Adv Polym Sci. 2006;201:225–96.

Rubinstein M, Colby R. Polymer physics. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003.

Pompe G, Pohlers A, Pötschke P, Pionteck J. Influence of processing conditions on the multiphase structure of segmented polyurethane. Polymer. 1998;39:5147–53.

Lu Q-W, Hernandez-Hernandez ME, Macosko CW. Explaining the abnormally high flow activation energy of thermoplastic polyurethanes. Polymer. 2003;44:3309–18.

Bourbigot S, Turf T, Bellayer S, Duquesne S. Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane as flame retardant for thermoplastic polyurethane. Polym Degrad Stab. 2009;94:1230–7.

Gu X, Wu J, Mather PT. Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS) suppresses enzymatic degradation of PCL-based polyurethanes. Biomacromol. 2011;12:3066–77.

Ayandele E, Sarkar B, Alexandridis P. Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS)-containing polymer nanocomposites. Nanomaterials. 2012;2:445–75.

Fu BX, Zhang W, Hsiao BS, Rafailovich M, Sokolov J, Johansson G, et al. Synthesis and characterization of segmented polyurethanes containing polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes nanostructured molecules. High Perform Polym. 2000;12:565–71.

Liu H, Zheng S. Polyurethane networks nanoreinforced by polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2005;26:196–200.

Lopes GH, Junges J, Fiorio R, Zeni M, Zattera AJ, Floresta B. Thermoplastic polyurethane synthesis using POSS as a chain modifier. Mater Res. 2012;15:698–704.

Kannan RY, Salacinski HJ, Odlyha M, Butler PE, Seifalian AM. The degradative resistance of polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane nanocore integrated polyurethanes: an in vitro study. Biomaterials. 2006;27:1971–9.

Raftopoulos KN, Pandis C, Apekis L, Pissis P, Janowski B, Pielichowski K, et al. Polyurethane-POSS hybrids: molecular dynamics studies. Polymer. 2010;51:709–18.

Raftopoulos KN, Jancia M, Aravopoulou D, Hebda E, Pielichowski K, Pissis P. POSS along the hard segments of polyurethane. Phase separation and molecular dynamics. Macromolecules. 2013;46:7378–86.

Xu H, Kuo SS-W, Lee J-SJ, Chang FF-C. Glass transition temperatures of poly(hydroxystyrene-co-vinylpyrrolidone-co-isobutylstyryl polyhedral oligosilsesquioxanes). Polymer. 2002;43:5117–24.

Pan G. Polyhedral Oligomeric Silsesquioxane (POSS). Physical properties of polymers handbook. New York: Springer; 2007. p. 577–84.

Lichtenhan JD. Polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes: building blocks for silsesquioxane-based polymers and hybrid materials. Comments Inorg Chem. 1995;17:115–30.

Koutsoumpis S, Raftopoulos KN, Jancia M, Pagacz JM, Hebda E, Papadakis CM, et al. POSS moieties with PEG vertex groups as diluent in Polyurethane elastomers: morphology and phase separation. Macromolecules. 2016;49:6507–17.

Raftopoulos KN, Koutsoumpis S, Jancia M, Lewicki JP, Kyriakos K, Mason HE, et al. Reduced phase separation and slowing of dynamics in polyurethanes with three-dimensional POSS-based cross-linking moieties. Macromolecules. 2015;48:1429–41.

Fu B, Hsiao B, Pagola S, Stephens P, White H, Rafailovich M, et al. Structural development during deformation of polyurethane containing polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes (POSS) molecules. Polymer. 2001;42:599–611.

Knight PT, Lee KM, Qin H, Mather PT. Biodegradable thermoplastic polyurethanes incorporating polyhedral oligosilsesquioxane. Biomacromol. 2008;9:2458–67.

Janowski B, Pielichowski K. Thermo (oxidative) stability of novel polyurethane/POSS nanohybrid elastomers. Thermochim Acta. 2008;478:51–3.

Raftopoulos KNN, Janowski B, Apekis L, Pissis P, Pielichowski K. Polyurethane-POSS organic-inorganic hybrid materials. The effect of soft segment length and nanoparticle content on the molecular dynamics. Mod Polym Mater Environ Appl. 2010;4:81–90.

Zhang H, Kulkarni S, Wunder SL. Polyethylene glycol functionalized polyoctahedral silsesquioxanes as electrolytes for lithium batteries. J Electrochem Soc. 2006;153:A239.

Pielichowski K, Jancia M, Hebda E, Pagacz J, Pielichowski J, Marciniec B, et al. Poliuretany modyfikowane funkcjonalizowanym silseskwioksanem—synteza i wlasciwosci. (Polyurethanes modified with functionalized silsesquioxanes—synthesis and properties.). Polimery. 2013;58:783–93.

Turri S, Levi M. Wettability of polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane nanostructured polymer surfaces. Macromol Rapid Commun. 2005;26:1233–6.

Turri S, Levi M. Structure, dynamic properties, and surface behavior of nanostructured ionomeric polyurethanes from reactive polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes. Macromolecules. 2005;38:5569–74.

Huang J, Jiang P, Wen Y, Haryono A. Synthesis and properties of castor oil based polyurethanes reinforced with double-decker silsesquioxane. Polym Bull. 2017;74:2767–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00289-016-1838-5.

Huang J, Jiang P, Wen Y, Deng J, He J. Soy-castor oil based polyurethanes with octaphenylsilsesquioxanetetraol double-decker silsesquioxane in the main chains. RSC Adv R Soc Chem. 2016;6:69521–9.

Neumann D, Fisher M, Tran L, Matisons JG. Synthesis and characterization of an isocyanate functionalized polyhedral oligosilsesquioxane and the subsequent formation of an organic-inorganic hybrid polyurethane. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:13998–9.

Mya KY, Wang Y, Shen L, Xu J, Wu Y, Lu X, et al. Star-like polyurethane hybrids with functional cubic silsesquioxanes: preparation, morphology, and thermomechanical properties. J Polym Sci Part A Polym Chem. 2009;47:4602–16.

Bharadwaj R, Berry R, Farmer B. Molecular dynamics simulation study of norbornene-POSS polymers. Polymer. 2000;41:7209–21.

Bizet S, Galy J, Gérard J-F. Molecular dynamics simulation of organic–inorganic copolymers based on methacryl-POSS and methyl methacrylate. Polymer. 2006;47:8219–27.

Zhang X, Chan ER, Glotzer SC. Self-assembled morphologies of monotethered polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane nanocubes from computer simulation. J Chem Phys. 2005;123:184718.

Striolo A, McCabe C, Cummings PT. Organic-inorganic telechelic molecules: solution properties from simulations. J.Chem Phys. 2006;125:104904.

Patel RR, Mohanraj R, Pittman CU. Properties of polystyrene and polymethyl methacrylate copolymers of polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes: a molecular dynamics study. J Polym Sci Part B Polym Phys. 2006;44:234–48.

Coleman M, Painter P. Hydrogen bonded polymer blends. Prog Polym Sci. 1995;20:1–59.

Pielichowski K, Majka TM, Leszczyńska A, Giacomelli M. Optimization and scaling up of the fabrication process of polymer nanocomposites: polyamide-6/montmorillonite case study. 2013. p. 75–103.

Mohamed M, Vuppalapati RR, Bheemreddy V, Chandrashekhara K, Schuman T. Characterization of polyurethane composites manufactured using vacuum assisted resin transfer molding. Adv Compos Mater. 2015;24:13–31.

Efrat T, Dodiuk H, Kenig S, McCarthy S. Nanotailoring of polyurethane adhesive by polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane (POSS). J Adhes Sci Technol. 2006;20:1413–30.

Connolly M, King J, Shidaker T, Duncan A. Processing and characterization of pultruded polyurethane composites, Technical Paper. Huntsmann International LLC; 2006. p. 1–16.

Bai J. Advanced fibre-reinforced polymer (frp) composites for structural applications. Oxford: Woodhead Publishing; 2013.

Davim J, Charitidis C. Nanocomposites: materials, manufacturing and engineering. Berlin/Boston: Walter De Gruyter Inc.; 2013.

Connolly M, King J, Shidaker T, Duncan A. Characterization of pultruded polyurethane composites: environmental exposure and component assembly testing. Composites 2006 Convention and trade show American composites manufacturers association, St Luis, MO USA; 2006.

Monticelli O, Fina A, Cavallo D, Gioffredi E, Delprato G. On a novel method to synthesize POSS-based hybrids: an example of the preparation of TPU based system. Express Polym Lett. 2013;7:966–73.

Mouritz A, Gibson A. Fire properties of polymer composite materials. Dordrecht: Springer; 2007.

Nanda AK, Wicks DA, Madbouly SA, Otaigbe JU. Nanostructured polyurethane/POSS hybrid aqueous dispersions prepared by homogeneous solution polymerization. Macromolecules. 2006;39:7037–43.

Hao T, Liu X, Hu G-H, Jiang T, Zhang Q. Preparation and characterization of polyurethane/POSS hybrid aqueous dispersions from mono-amino substituted POSS. Polym Bull. 2017;74:517–29.

Xue M, Zhang X, Wu Z, Wang H, Ding X, Tian X. Preparation and flame retardancy of polyurethane/POSS nanocomposites. Chin J Chem Phys. 2013;26:445–50.

Winter HH, Mours M. The cyber infrastructure initiative for rheology. Rheol Acta. 2006;45:331–8.

Fernandez-DArlas B, Eceiza A. Structure-property relationship in high urethane density polyurethanes. J Polym Sci Part B Polym Phys. 2016;54:739–46.

Vallance M, Yeung AS, Cooper SL. A dielectric study of the glass transition region in segmented polyether-urethane copolymers. Colloid & Polym. Sci. 1983;261:541–54.

Vallance MA, Castles JL, Cooper SL. Microstructure of as-polymerized thermoplastic polyurethane elastomers. Polymer. 1984;25:1734–46.

Raftopoulos KN, Janowski B, Apekis L, Pielichowski K, Pissis P. Molecular mobility and crystallinity in polytetramethylene ether glycol in the bulk and as soft component in polyurethanes. Eur Polym J. 2011;47:2120–33.

Zhang W, Müller AHE. Architecture, self-assembly and properties of well-defined hybrid polymers based on polyhedral oligomeric silsequioxane (POSS). Prog Polym Sci. 2013;38:1121–62.

Hao N, Böhning M, Goering H, Schönhals A, Bo M, Scho A. Nanocomposites of Polyhedral oligomeric phenethylsilsesquioxanes and poly(bisphenol A carbonate) as investigated by dielectric spectroscopy. Macromolecules. 2007;40:2955–64.

Fox T. Influence of diluent and of copolymer composition on the glass temperature of a polymer system. Bull Am Phys Soc. 1956;1:123.

Raftopoulos KN, Janowski B, Apekis L, Pissis P, Pielichowski K. Direct and indirect effects of POSS on the molecular mobility of polyurethanes with varying segment Mw. Polymer. 2013;54:2745–54.

Raftopoulos KN, Koutsoumpis S, Hebda E, Papadakis CM, Pielichowski K, Pissis P. Architecture effects on the morphology and segmental dynamics in Polyurethane-POSS organic inorganic hybrids. In Pielichowski K, editors Modern polymeric materials for environmental applications. 2016. p. 297–306.

Tan J, Jia Z, Sheng D, Wen X, Yang Y. Thermomechanical and surface properties of novel poly(ether urethane)/polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxane nanohybrid elastomers. Polym Eng Sci. 2011;51:795–803.

Lai YS, Tsai CW, Yang HW, Wang GP, Wu KH. Structural and electrochemical properties of polyurethanes/polyhedral oligomeric silsesquioxanes (PU/POSS) hybrid coatings on aluminum alloys. Mater Chem Phys. 2009;117:91–8.

Pan R, Shanks R, Kong I, Wang L. Trisilanolisobutyl POSS/polyurethane hybrid composites: preparation. WAXS and thermal properties. Polym Bull. 2014;71:2453–64.

McMullin E, Rebar HT, Mather PT. Biodegradable thermoplastic elastomers incorporating POSS: synthesis, microstructure, and mechanical properties. Macromolecules. 2016;49:3769–79.

Koberstein JT, Russell TP. Simultaneous SAXS-DSC study of multiple endothermic behavior in polyether-based polyurethane block copolymers. Macromolecules. 1986;19:714–20.

Acknowledgements

This work has been financed by the National Science Centre of Poland under Contract No. DEC-2011/02/A/ST8/00409.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Majka, T.M., Raftopoulos, K.N. & Pielichowski, K. The influence of POSS nanoparticles on selected thermal properties of polyurethane-based hybrids. J Therm Anal Calorim 133, 289–301 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-017-6942-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10973-017-6942-8