Abstract

We use data on over 800 early-stage technology transaction negotiations to model the impact of different types of risk on whether the transaction was executed and then test for contractual factors that may ameliorate these risks. Our data highlight the importance of project risk in determining which negotiations result in a signed contract. We find that transactions aiming to sell early-stage technology to large corporates are less likely to be executed when the buyer is large, and the contract contains royalties, holding constant five different types of risk involved in the transaction. Other risk-reducing contract modes do not appear to increase the probability of an executed contract. Our results support the view that technology sellers’ reliance on royalties may reflect organisational preferences or capabilities which may not be economically or managerially optimal. We also find that ‘people risk’ matters more than ‘technological’, ‘market’, ‘appropriation’ and ‘freedom-to-operate’ risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

This paper quantifies the effects of the major technology transaction risks on transaction success and tests for whether contract design can moderate their impact using data on over 800 technology transactions. Transactions in early-stage technology—technology that needs further development before commercialization—are critical junctures in the pathway to market (Arora et al., 2004).Footnote 1

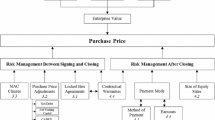

Contracts governing technology transfer typically include a mix of upfront payments and success-contingent payments to manage trading hazards. The stakes are high. An improperly designed contract can diminish overall project value or result in expensive legal disputes (Reslinski & Wu, 2016). Royalties are the most common form of success-contingent payment, but milestone payments and equity can be highly remunerative when the technology is successful (Jensen & Thursby, 2001; Reslinski & Wu, 2016). Despite their popularity in practice, the drawbacks of royalties are well understood by contract theorists. Royalties can be costly to monitor and difficult to design where the future use of the technology, and its contribution to product value, are unknown (Dechenaux et al., 2011; Reslinski & Wu, 2016; Savva & Taneri, 2014). Compounding this puzzle, it has been found that where universities do take equity, the return is higher than royalty revenues (Bray & Lee, 2000).

This article makes three contributions to the literature. First, most existing evidence on contract design for early-stage technology trades is limited to technology transfer licences from university technology transfer offices (Jensen & Thursby, 2001, Feldman et al., 2002, Siegel et al., 2007, Dechenaux et al., 2011).Footnote 2 In this paper, we consider early-stage technology transactions from and between for-profit firms as well as public sector research organisations. Including for-profit firms allows greater disparity in the explanatory variables, especially risk and firm size.

Secondly, theories of the role contract design plays in mitigating risk focus on the optimal division of remuneration between two types of payment: upfront (fixed) payment share and variable (success-contingent) payment share. They do not usually distinguish between the specific form that any success contingent payments might take such as royalties, milestone payments or equity (Crama et al., 2008; Dechenaux et al., 2011; Gallini & Wright, 1990). Feldman et al (2002) have made cogent arguments for why both parties might prefer equity over royalties, but these ideas have yet to be tested econometrically using a representative sample of data. In this article, we investigate this distinction.

Finally, as part of assessing the impact of contract design, we are also able to test and compare the relative impact of types of transaction risk on the probability that a contract will be executed. Not surprisingly we find that greater risk is associated with a reduced probability of a successfully concluded contract, but we estimate which risks matter most by estimating standardised coefficients.

The most common discussions over contract design relate to the need to allocate risk to the seller or incentivise inventor participation. By this argument, technology sellers may rely on royalties simply because of the risky nature of technology traded or the importance of tacit knowledge in their ongoing development. However, milestone payments and equity also reallocate risk to the seller and incentivise their participation in ongoing development but avoid the trailing administrative burden associated with royalties (Jensen & Thursby, 2001; Savva & Taneri, 2014). Feldman et al. (2002) articulate five reasons why both the buyer and seller would prefer equity over royalties: the seller can extract value before any sales are made through selling shares in the buying firms; equity aligns the interests of the buyer and seller so negotiations are not a zero-sum game; equity can make it easier to negotiate follow-on deals; equity avoids the necessity of defining a large number of contingent items in a contract; and following from these points, equity reduces the need for litigation as both parties have strong incentives to negotiate in good faith.

In this article we test the theory that inclusion of royalties in contracts can reduce the probability that the contract will be executed. This idea is based on discussions we undertook with 66 professional technology intermediaries around Australia. Our data comprises a random sample of 848 contracts for the trade of early-stage technologies. These data were collected via a systematic survey of the market for early-stage technology in Australia and cover all forms of technology transfer across all technology fields. As mentioned, existing studies of the market for early-stage technology have been limited to technology transfer from universities at the expense of corporate sellers and we believe this is the first empirical study reporting systematic evidence on contracts for trade in early-stage technology both from public-sector technology transfer offices and between for-profit firms.

Our results show that royalty contracts involving large corporate buyers are less likely to be executed (i.e., signed off), holding constant all other relevant factors. This finding supports the view that use of royalties when transferring technology to large firms reflects the sellers’ organisational preferences or capability which may not be economically or managerially optimal. Our interviews with professional intermediaries suggested two managerial norms to explain this. First that sellers, especially public sector sellers, prefer exposure to upside risk due to reputational cost to an employee who fails to capture a substantial share of a major blockbuster technology. In contrast, evaluating failure in technology transfer office negotiating performance where negotiations break down is difficult since few invention disclosures are ever successfully transferred.Footnote 3 Secondly, that public sector managers typically have the authority to sign contracts for milestone and royalty payments but not equity deals.Footnote 4

2 Characteristics of successful technology transfer

The characteristics of successful public sector technology transfer offices has been well studied. Studies typically examine correlations between inputs, such as university research, university resources, office age, size and legal resources; and outputs, such as patent or licensing deals (see Hamilton & Philbin, 2020; and Aksoy & Beaudry, 2021 for recent reviews).

This line of inquiry is not our focus. Instead, we model the impact of different types of risk, for both corporate and public sector organisations, associated with the technology or idea being transacted and then test for contractual factors that may ameliorate these risks. Mowery (1983) and Pisano (1990) argue that these risks stem from three features of unformed or early-stage transactions: uncertainty, non-codifiability and opacity. First, uncertainty about future cost- or demand-side conditions can create an expectation that ex post renegotiations will be needed later as unforeseeable circumstances unfold. If there is a fear that the other party will behave opportunistically, parties may choose not to transact with each other (Williamson, 1985). Secondly, where it is difficult to accurately codify the nature of the product traded—fuzzy boundaries and polysemous words being common in new fields—parties may fail to trade if there is a suspicion that the other party will act on the literal terms rather than the spirit of the agreement. And finally, when quality is opaque—because assessing the quality of work done is complicated and costly —then an exchange can also fail to occur as it is difficult to agree on a reasonable price. These risks can erode confidence to the point where markets collapse, and no technology transaction takes place.

Our semi-structured interviews revealed a number of risks in closing a deal and we have categorised these into five types:

-

Technical risk—over the technical feasibility of the technology. Many people, especially business angels and public sector intermediaries, reported that the robustness of the technology and how well the technology performed in varying contexts, was an issue. To the buyer, the technology was often a black-box and a high level of trust in the sellers’ evidence was needed in order to make the purchase

-

Market risk—over the existence of a market for the final product. The expected cost of production was most often raised by business angel and farming sector intermediaries. Costs often depended on the scale of production and expected learning-by-doing. For new processes, the major costs were re-tooling, maintenance and reliability. For new products, the costs included marketing and consumer resistance/awareness in addition to any new production processes.

-

Appropriation risk—over the presence and validity of exclusive rights. The risk that other parties will copy the technology was not a significant risk for new processes that could be kept as a trade secret. Although, this risk was raised by the industry, patent attorneys and venture capitalists, it was not a major issue for intermediaries from the public research sector.

-

Freedom-to-operate risk—over the felt certainty of freedom-to-operate warrantees. The risk of being sued for infringement by another party was primarily raised by business angel intermediaries. It was less mentioned by intermediaries from public sector organisations

-

People risk—over the degree of divergence between buyers’ and sellers’ motivations. The issue of dealing with difficult inventors and parties who had unrealistic notions of value were highlighted by patent attorneys and staff from university technology transfer offices.

Interviewees claimed, that in their experience, negotiators undertake four actions to mitigate some of these risks.

-

The first action is to screen technologies for these risks, especially technical feasibility and market need risks.

-

The second action is to favour technologies where the parties have an existing relationship of trust.

-

The third action is to design contractual terms that apportion risk in accordance with each party’s ability to bear risk and their appetite for risk.

-

The last action is to adopt contractual terms that minimises the cost of compliance to each party.

The rationales for the first two actions are straightforward. Anecdotally, we know that that technology intermediaries use large patent and research databases to assess congestion in given technology spaces and will often supplement this information with qualitative evidence from technology consultants on the size and growth of target markets. On the second action, there is empirical evidence that a high levels of trust between the two parties can overcome some of these issues and lead to a successful market trade (see Jensen et al., 2015).

The last two actions concerning contract design relate to this study and require more explanation. With respect to the third action listed above, the literature discusses how success-contingent payments shift risk from the buyer to the seller to enable more frequent technology trades. These modes of payment comprise equity—whereby sellers receive a (minority) equity stake in the commercialization entity; royalties—whereby sellers receive dues on future sales of products embodying the technologyFootnote 5; and milestone payments—whereby sellers receive payments that are contingent on demonstration of specified technical feasibility. In empirical work, it is standard to infer the risk preferences based on firm size (Ackerberg & Botticini, 2002; Allen & Lueck, 1995). The cost of bearing risk is argued to be lower for large, diversified firms including universities and public research organisations. As risk-averse entities, small buyers with a relatively high cost of bearing risk are conjectured to prefer contingent payments to early-stage cash outlays such as upfront and milestone payments. Royalties and equity transfer both upside and downside risk to the seller (Bray & Lee, 2000; Feldman et al., 2002).

With respect to the last action, our interviewees indicated that transaction costs are a consideration in contract design. Transaction costs comprise both the cost of information required to shape the terms of the sale and ongoing costs including monitoring, verification, and enforcement of payments (Chueng, 1969; Stiglitz, 1974; Hallagan, 1978; Leffler & Rucker, 1991). Valuation costs are similar across payment types, but ongoing relationship costs differ substantially.Footnote 6 Setting royalties can be particularly problematic for early-stage technology due to difficulties in defining the basis of payment where the exact use of the technology may be poorly defined, or unknown (Dechenaux et al., 2011). Cost of enforcement and monitoring are avoided by upfront ‘cash’ payments and milestone payments, which typically rely on narrowly defined, observable technical outcomes. By contrast, ongoing costs of equity and royalties can be considerable. Equity deals invoke well-known monitoring costs associated with ensuring managers do not act to minimise accounting profits, and therefore payments to equity holders. Royalty enforcement requires the seller to observe sales, and audit provisions are routinely included in royalty contracts.

In this paper, we estimate the impact of the five types of risk on whether the deal was done, and the contract executed, and then test for whether the mitigating factors, trust and contract design are effective.

3 Data and descriptive statistics

We aimed to get representative data on early-stage technology transactions from the population of people in Australia who mainly work as intermediaries in the market for early-stage technology. We approached this aim in two stages.Footnote 7 First, we undertook 66 semi-structured interviews with people involved in buying and selling early-stage technology around Australia. The interviews provided a dual benefit of identifying the survey population and of collecting qualitative information on the preferences and the functioning of the market to inform our analysis. Details regarding the survey development are provided at Appendix 1. Our lists included both R&D intensive firms and industry partners of university technology transfer offices and government agencies. This resulted in the collection of 1,867 named individuals identified as buyers, sellers or brokers in the market for early-stage technology in Australia. We only had complete addresses for 1427 people. There are no official registration organisations that buy, sell or broker early-stage technology but by a process of consulting lists and chasing referrals we believe we have a list of the most people who regularly trade.

Secondly, we posted questionnaires to these 1427 people and received 670 returned questionnaires—a response rate 47.0 per cent. This high response rate was achieved by the provision of an incentive in the first mail-out (a A$50 gift voucher was given whether people responded or not).Footnote 8 Respondents were asked to provide information on the most recent executed and the last abandoned negotiation (to form roughly equal numbers of executed and non-executed contracts). Sampling the last transaction (as opposed to letting the respondents choose which transactions to report) ensures that the transactions in the sample are not systematically correlated with their size or with their importance to respondents’ organizations. Some brokers were in a position to both buy and sell technology and we asked this group about their last four negotiations (executed and non-executed, buy and sell). Other brokers were only asked about either buy or sell (e.g., universities were only asked about selling). Some respondents indicated that they had not been involved in a technology transaction with their current employer, and some did not have complete information on contract design. This left 456 respondents. This is a high response rate for this type of business survey and given that they survey frame approximates a census of relevant firms we have some confidence in the representative nature of the responses. Ultimately, we had data on 848 complete contracts from the 456 survey respondents.

Table 1 shows the average attributes of technology being transacted for this sample of 848 contracts. Buyer and seller type were identified from our data base or self-reported characteristics of the respondent or about the counterparty.

Survey respondents nominated the stage of development of early-stage technology between basic science; applied science; proof-of-concept; prototype; pilot manufacturing and other. They were asked about their patent and copyright status and the content of the proposed contract for transferring the technology. Respondents were asked about when and how the buyers and sellers met and the difference in their objectives. They rated several risks on a Likert scale, with anchors, ‘very certain’ (= 1) to ‘very uncertain’ (= 7). These risks comprised the feasibility of the technology; the existence of a market for the final product; intellectual property (IP) protection; rights to complementary technologies; the value of the technology and freedom-to-operate warrantees.

We grouped these responses to form the five composite measures of risk reflecting the five categories of risk commonly nominated both in the relevant literature and by practitioners subject to our semi-structured interviews. The five types of risk are: Technical risk (i.e., will it work), market risk (will it sell, is there adequate demand), appropriation risk (will the innovator profit from demand), freedom-to-operate risk (does the innovator risk litigation for infringing IP); and people risk (risk of losing support from difficult-to-replace scientists and innovators). Technical risk is the average of positive responses to whether the technology was: basic science, applied science or proof-of-concept, an early-stage technology, and of the respondents’ assessment of the uncertainty regarding the feasibility of the technology measured on a Likert scale. Appropriation risk is the average of positive responses to whether the technology was covered by a patent or copyright, was never refused a patent, or deemed unpatentable subject matter; was not the subject of IP uncertainty and the contract had exclusivity clauses. Freedom-to-operate risk was the average of positive responses to certainty about the rights to complementary technologies and freedom-to-operate warrantees. Market risk was the average of responses to whether the technology was specific (rather than general purpose) and there was certainty about the existence of a market for the technology and the value of the technology. People risk was the average of responses to questions about the similarity of buyers’ and sellers’ objectives, whether ongoing inventor participation was needed, and whether the first in-person meeting between buyers and sellers occurred early in the negotiations. Items that are combined to form each risk variable are givens and therefore should not be determined by contract mode but rather a driver of contract mode. Appendix 2 gives details of survey items use to construct the risk variables.

Ex ante trust was based on the how the parties met with cold called being the lowest, and repeat business and former colleague or friend, being the highest (See Jensen et al., 2015 for a fuller discussion). Finally, we asked respondents whether the proposed contract included payments based on equity, royalty, milestone, or upfront payments.

Table 1 presents a summary of the survey data according to whether or not the contract was executed. The t-test shows statistically significant differences in the level of risk between executed and not executed contracts. However, there was no difference according to contract type, buyer type and seller type. Transactions involving higher levels of trust between the parties were significantly more likely to have been executed. Table 1 also reveals that two-thirds of contracts contain royalty payments and about half include milestone payments, and one in five include equity payments.

4 Approach and estimation results

We aim to evaluate whether inclusion of royalties in contracts reduces the probability that a technology transaction is successfully executed and which mitigating factors appear important. Our dependent variable is equal to 1 if the contract was executed (i.e., the transaction was successful), = 0 otherwise. The explanatory variables are survey measures of the five types of risk: Technical, Appropriation, Freedom-to-operate, Market and People and the two types of moderating factors—the degree of trust between parties and the contract design.

In Table 2, we report beta coefficients, which normalise the regression coefficient for the measurement units of the variable, to enable us to compare the relative influence of each type of risk. These tables present the OLS estimations, but the results are similar if we used a probit model. Our estimates reveal that People risk is the largest risk in transactions followed by market, appropriation and technical risks. Freedom-to-operate risks was not associated with transaction failure. Not surprisingly given the magnitude of the effects of People risk, our measure of Ex ante trust showed considerable positive effects on transaction success.

The inclusion of equity, royalty or milestone payments in contact design did not appear to have any impact on transaction success. However, as shown in Table 3, when contract design was interacted with the type of buyer, we found that large corporate buyers who were presented with a contract that included royalties were less likely to execute the contract. There appeared to be no impact of equity, milestone payments and upfront payments on transaction success regardless of the type of buyer.

We then investigated which type of sellers are using royalties. According to Tables 4 and 5, public sector organisation technology transfer offices are most likely to include royalties—two in three transactions include royalties. On the other hand, large corporations, as sellers, are the least likely to include royalties—only a third include them. This is consistent with our semi-structured interviews which revealed that large corporations find that royalties, either as a buyer or seller, have high administrative marginal costs on already complex operational arrangements.

We did find that intermediaries from public sector organisations were less experienced and, not surprisingly, dealt with technologies that were more inherently risky from a technical viewpoint. The overuse of less experienced technology intermediaries in public sector organisations should be a concern given the role of these organisations in driving fundamental research. It may relate to their conditions of employment, especially pay, or a general lack of understanding by public organisations executives of the capabilities needed for these roles. It is possible, as mentioned before that a lack of agency given to intermediaries in the public sector could cause frustration and high labour turnover. An investigation of what makes for a successful career as a technology intermediary would reveal more about this situation.

5 Concluding remarks

It is increasingly common for technology to pass between several companies on its way to market. Potential gains from trade in early-stage technology are large but are difficult to achieve due to pervasive risks and contracting hazards. These trading hazards are managed using an array of contractual tools including various success-contingent payment modes. Of the available options, royalties are by far the most prevalent success-contingent payment mode for contracts governing transfer of early-stage technology, consistent with international evidence. In this paper we test for whether the design of the contact—in terms of the payment modes—affects whether the contract was successfully executed. To the best of our knowledge, no other empirical study has compared the effect of types of contingent contract terms (equity, milestones and royalties) whether a potential technology trade is finalised (although Razgaitis [2006] undertook a study on contract execution rates in Canada and the USA but did not investigate the role of contract terms).

Previous analysis of contracts in market for early-stage technology have been largely restricted to contracts governing technology transfer licences from universities (Jensen & Thursby, 2001, Feldman et al., 2002, Siegel et al., 2007, Dechenaux et al., 2011).Footnote 9 Departing from a well-established literature on contracts for market-ready technology, our data were collected via an extensive survey of Australian buyers and sellers of immature technology resulting in a random sample of contracts governing both business-to-business sales as well as public sector-to-business sales.

We find that risks involving people have the largest negative impact on whether the contract is executed and a high level of ex ante trust between the buyer and seller can mitigate this effect. Whereas in general, the form of payment embodied in a proposed contract—equity, royalties, and milestones—do not affect its execution success, large corporate buyers appear to walk away from contracts with royalty payments. This is consistent with one of our interviewees, who observed that their employer, a large buyer, avoids royalties in order to reduce the administrative burden. The latter is an increasing function of the number of (overlapping) claims on any of their products. It is also consistent with Dechenaux et al. (2011)’s finding that large businesses prefer milestone payments to incentivise ongoing inventor participation when in-licensing from universities (survey of 112 US businesses).

One therefore wonders, why are royalties are so prevalent? An alternative reason lies in the feature of the institutions selling the technology, rather than the feature of the technology being traded. Bray and Lee (2000) and Feldman et al. (2002), both argue that universities are prone to ‘over-use’ royalties because managers lack experience, or do not have the necessary institutional support for contracts involving equity or milestone payments.

Notes

Equity agreements need to be authorised by the peak governing body of the university and this additional tier of governance creates a disincentive for their use.

Royalties are most commonly defined ad valorem on total value of sales or as a price per unit basis.

Accurate valuation is required to set optimal total payment, regardless of the payment mode. Valuation costs are explicit in the case of equity deals, but royalty rates are often based on a ‘rule of thumb’ rather than detailed valuation.

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

The $50 vouchers were given whether or not the individual replied to the questionnaire. The vouchers were included in the first mailout. Perhaps those who kept the $50 and did not reply are too busy or less civic minded than those who replied. We cannot know the extent of unobservable differences, but we do present more information on non-respondents in Appendix A.

This is a reproduction of the appendix written by one of the authors in Jensen, P., Palangkaraya, A. and Webster, E. (2015) ‘Trust and the Market for Technology’, Research Policy, 44, 340–356.

2.2 per cent of contacts were not ‘in scope’ as their contact address had changed or the person replied that they were not involved in technology transactions. Other company surveys we undertake, which do not include in the hand incentives, typically achieve response rates of 15 per cent.

References

Ackerberg, D. A., & Botticini, M. (2002). Endogenous matching and the empirical determinants of contract form. Journal of Political Economy, 110(3), 564–591.

Aksoy, A. Y., & Beaudry, C. (2021). How are companies paying for university research licenses? Empirical evidence from university-firm technology transfer. Journal of Technology Transfer, 46, 2051–2121.

Allen, D. W., & Lueck, D. (1995). Risk preferences and the economics of contracts. The American Economic Review, 85(2), 447–451.

Anand, B. N., & Khanna, T. (2000). The structure of licensing contracts. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 48(1), 103–135.

Arora, A., & A. Gambardella. (2010). ‘The Market for Technology’, in Bronwyn H. Hall and Nathan Rosenberg, eds. Handbook of the Economics of Innovation, North-Holland, 1, 641–678.

Arora, A., Fosfuri, A., & Gambardella, A. (2004). Markets for technology: The economics of innovation and corporate strategy. MIT press.

Arora, A., Fosfuri, A., & Rønde, T. (2013). Managing licensing in a market for technology. Management Science, 59, 1092–1106.

Bianchi, M., Cavaliere, A., Chiaroni, D., Frattini, F., & Chiesa, V. (2011). Organisational modes for Open Innovation in the bio-pharmaceutical industry: An exploratory analysis. Technovation, 31(1), 22–33.

Bray, M. J., & Lee, J. N. (2000). University revenues from technology transfer: Licensing fees vs. equity positions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5), 385–392.

Caves, R. E., Crookell, H., & Killing, J. P. (1983). The imperfect market for technology licenses. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 45(3), 249–267.

Chesbrough, H. W. (2006). Open innovation: The new imperative for creating and profiting from technology. Harvard Business Press.

Chueng, S. N. G. (1969). The theory of share tenancy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Crama, P., De Reyck, B., & Degraeve, Z. (2008). Milestone payments or royalties? Contract Design for R&d Licensing, Operations Research, 56(6), 1539–1552.

Dechenaux, E., Thursby, J., & Thursby, M. (2011). Inventor moral hazard in university licensing: The role of contracts. Research Policy, 40(1), 94–104.

Feldman, M., Feller, I., Bercovitz, J., & Burton, R. (2002). Equity and the technology transfer strategies of American research universities. Management Science, 48(1), 105–121.

Gallini, N. T., & Wright, B. D. (1990). Technology transfer under asymmetric information. The RAND Journal of Economics, 21, 147–160.

Gans, J. S., & Stern, S. (2010). Is there a market for ideas? Industrial and Corporate Change, 19(3), 805–837.

Hallagan, W. S. (1978). Share contracting for California gold. Explorations in Economic History, 15(2), 196–210.

Hamilton, C., & Philbin, S. P. (2020). Knowledge based view of university tech transfer—A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Administrative Sciences, 10(3), 62.

Jensen, P. H., Palangkaraya, A., & Webster, E. (2015). Trust and the market for technology. Research Policy, 44(2), 340–356.

Jensen, R., & Thursby, M. (2001). Proofs and prototypes for sale: The licensing of university inventions. American Economic Review, 9(1), 240–259.

Lamoreaux, N. R., & Sokoloff, K. L. (2001). Market trade in patents and the rise of a class of specialized inventors in the 19th-century United States. American Economic Review, 91(2), 39–44.

Leffler, K. B., & Rucker, R. R. (1991). Transactions costs and the efficient organization of production: A study of timber-harvesting contracts. Journal of Political Economy, 99(5), 1060–1087.

Macho-Stadler, I., Martinez-Giralt, X., & Perez-Castrillo, J. D. (1996). The role of information in licensing contract design. Research Policy, 25(1), 43–57.

Marjit, S., & Mukherjee, A. (2001). Technology transfer under asymmetric information: The role of equity participation. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics (JITE) Zeitschrift Für Die Gesamte Staatswissenschaft, 157(2), 282–300.

Mowery, D. (1983). The relationship between intrafirm and contractual forms of industrial research in American manufacturing, 1900–1940. Explorations in Economic History, 20, 351–374.

Piachaud, B. S. (2002). Outsourcing in the pharmaceutical manufacturing process: An examination of the CRO experience. Technovation, 22(2), 81–90.

Pisano. (1990). The R&D boundaries of the firm: an empirical analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1990), 153–176.

Prakash, K., Churchill, S. A., & Smyth, R. (2022). Are you puffing your Children’s future away? Energy poverty and childhood exposure to passive smoking. Economic Modelling, 114, 105937.

Razgaitis, R. (2006). U.S./Canadian Licensing in 2005—Survey Results. Nouvelles-Journal of the Licensing Executives Society, 42(4), 641.

Reslinski, M. A., & Wu, B. S. (2016). The value of royalty. Nature Biotechnology, 34(7), 685–690.

Savva, N., & Taneri, N. (2014). The role of equity, royalty, and fixed fees in technology licensing to university spin-offs. Management Science, 61(6), 1323–1343.

Siegel, D. S., Veugelers, R., & Wright, M. (2007). Technology transfer offices and commercialization of university intellectual property: Performance and policy implications. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 23(4), 640–660.

Stiglitz, J. E. (1974). Incentives and risk sharing in sharecropping. The Review of Economic Studies, 41(2), 219–255.

Thomson, R., & Webster, E. (2013). External ventures: Why firms do not develop their inventions in-house? Oxford Economic Papers, 65(3), 653–674.

Vishwasrao, S. (2007). Royalties vs. fees: How do firms pay for foreign technology? International Journal of Industrial Organization, 25(4), 741–759.

Williamson, O. (1985). The economic institutions of capitalism: Firms, markets, relational contracting. New York: Free Press.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. 2008 Australian Research Council Linkage Grant LP0989343.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1—The survey process

A technology broker is defined in this study as a person who acts as a go-between or match-maker connecting the buyers and sellers of technologies that need further development before they can be used.Footnote 10 As comprehensive lists do not exist for people employed in this capacity, we undertook an extensive process to uncover the names and addresses of all relevant people in Australia. This process took over two years and involved: 66 semi-structured interviews with people who were referred to us as being in technology transaction business; extensive on-line searches; and a wide range of industry contact lists. The organisations covered by this search process included: business angels; Commercialisation Australia; COMET; cooperative research centres (CRCs); the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO); state departments of primarily industry; large companies conducting significant R&D; public providers of innovation services and information; patent attorneys; public-sector research institutes; universities; R&D corporations; venture capitalists and independent firms which specifically act as technology brokers.

In all, by the beginning of 2011 we had collected 1867 names and addresses. Although many of these could be described as in-house brokers—business development managers for large organisations—some were employed by stand-alone businesses whose express function was to act as a broker. We were interested only in people who had a hands-on role in technology transactions and thus did not survey managers with only supervisory or policy roles. Table

6 shows that of our final list of brokers, 626 were in the business of assisting both buyers and sellers (mainly commercial companies); 535 assisted the seller only (mainly business development managers for public sector or semi-public sector bodies); and 706 acted more remotely as facilitators of the exchange (patent attorneys and public sector advisors).

Our intention with the survey was two-fold: first, to scope the characteristics of the market for technology in Australia; and second, to analyse the determinants of a successful technology transaction. As mentioned, in order to collect a random sample of data on transactions that succeeded and those that did not, we asked each person to answer a set of questions about the last completed (executed) transaction and the last abandoned (non-executed) transaction in which they had been involved. Asking about the last transaction is a well-known technique for reducing sample selection. For example, we did not want people to report on the most successful, or the largest, or the most time-consuming transaction. With respect to our meaning of success: we sought only to record whether or not the deal was done since we did not believe this was the appropriate type of survey to record what happened to the technology after the transaction was completed (or not). As such we do not report on any standard measure of success such as whether or not the technology was used.

The first mail-out for the survey took place in June 2011, with 99 per cent of responses returned by December 2011. We surveyed the whole population except in relation to patent attorneys, who we limited to 200 randomly selected people (for cost reasons). Table 6 presents the response rates across different types of broker. The overall response rate was 47.0 per cent, which is high for a company-based survey and reflects the provision of an incentive (A$50 gift voucher) in the first mail-out.Footnote 11 The response rates vary from 31.6 per cent (Business Angels) to 65.0 per cent (Public Sector Research Organisations). In total 670 people responded to the survey, but 214 indicated that they had not been involved in a technology transaction with their current employer, leaving 456 respondents.

Appendix 2—items use to construct the risk variables

Risk type & item | Response options (either yes/no or likert scale) | Scoring (high = more risky) |

|---|---|---|

Technical risk | ||

How commercial-ready was this technology when you began the negotiations?) | Basic science, applied science, proof of concept | 1 point |

If there was no patent or pending patent, do you know why? | Early-stage technology | 1 point |

How uncertain was the feasibility of the technology | Very certain–very uncertain | Likert scale 1–7 |

Market risk | ||

In terms of its specificity of application, how would you characterise the technology? | General purpose–specific | Likert scale 1–7 |

How uncertain was the existence of a market for the final product | Very certain–very uncertain | Likert scale 1–7 |

How uncertain was the value of the technology | Very certain–very uncertain | Likert scale 1–7 |

Appropriate risk | ||

At the time of negotiations, what type of formal intellectual property (IP) protection did this technology have a Registered patent | Yes/no | 1 point (reversed) |

At the time of negotiations, what type of formal intellectual property (IP) protection did this technology have copyright | Yes/no | 1 point (reversed) |

If there was no patent or pending patent, do you know why? Patent refused | Yes/no | 1 point |

If there was no patent or pending patent, do you know why? Subject matter not patentable | Yes/no | 1 point |

How uncertain was IP protection | Very certain–very uncertain | Likert scale 1–7 |

Did the signed contract include exclusivity clauses? | Yes/no | 1 point (reversed) |

Freedom-to-operate risk | ||

How uncertain was rights to complementary technologies? | Very certain–very uncertain | Likert scale 1–7 |

How uncertain was Freedom-to-operate warrantees? | Very certain–very uncertain | Likert scale 1–7 |

Did the signed contract include warrantee for freedom-to-operate? | Yes/no | 1 point (reversed) |

People risk | ||

How different were buyer’s and seller’s objectives? | Very different–very similar | Likert scale 1–7 (reversed and standardised with mean = 0.5, standard deviation = 0.3) |

Did the signed contract include ongoing inventor participation? | Yes/no | 1 point (reversed) |

For this transaction, when did you first meet in-person with the seller? Early in negotiations | Yes/no | 1 point (reversed) |

For this transaction, when did you first meet in-person with the seller? Never | Yes/no | 1 point |

Ex ante trust | ||

In what context did the buyer and seller meet? | Conference or professional seminar (1), Third party introduction (2), Cold called (3), Industry network (4), REPEAT business (5), Other (6) | Points in brackets |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Doran, P., Thomson, R. & Webster, E. When royalties impede technology transfer. J Technol Transf (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-024-10095-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-024-10095-5