Abstract

We examine whether the probability of innovating a company’s business model towards the Industry 4.0 paradigm is affected by external institutional support and family leadership. Industry 4.0 is the information-intensive transformation of global manufacturing enabled by Internet technologies aimed at reinventing products and services from design and engineering to manufacturing. Using a sample of 3000 firms from a corporate survey on the manufacturing industry in Italy, our results showed that family leadership has a significant positive influence on the adoption of Industry 4.0 business models, but only in terms of family ownership. By contrast, family management has a negative influence on the probability of adopting a new business model. However, this negative influence is almost totally offset by the presence of the Triple Helix, i.e. the external support by public institutions and universities, which counterbalances the lower propensity of family managers to adopt Industry 4.0 business models. This supporting role only occurs when institutions and universities act together.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Institutional support from public institutions and universities plays an important role in sustaining the competitiveness of private companies, as it provides firms with critical resources that they can use for innovation and development (Li and Atuahene-Gima 2001; Sheng et al. 2013; Shu et al. 2015). SMEs and non-innovating firms are usually indicated as important policy targets because of the gaps in their resource endowment and managerial abilities (Kotlar et al. 2013; Müller et al. 2018). For these firms, external support from development agencies, universities or research centres provides an opportunity to take advantage of the most promising technologies, which are crucial for enhancing performance (Büchi et al. 2020). It also enables them to adopt the most appropriate business model for the new industry landscape of the Industry 4.0 digital revolution (Müller et al. 2020; Müller et al. 2018). As a radically new approach to manufacturing and value chain management, Industry 4.0 is transforming global industry. This transformation is much harder to manage for small and non-innovating firms, and can prevent them from exploiting the full benefits of hyper-personalized products and services driven by innovative business models.

Company ownership and management, i.e. company leadership, provides a further rationale for external support for SMEs. A vast literature shows that company leadership plays a crucial role in explaining the observed differences in the innovation behaviour of incumbents, as it influences the incentives and expected returns of decision-makers and shapes the innovative profile of target firms. Among the different owners, family owners are ideal candidates to explore this issue. Several features associated with this type of ownership are behind this claim. Firstly, despite their flexibility and long-term orientation, family firms are often weak innovators because of the narrow resource endowment that limits their ability to catch up with technology (König et al. 2012). Secondly, the conservative attitude that characterizes this particular form of governance may sometimes prevent family firms from interpreting policies and programs correctly (Peng 2003; Ma et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2017) and impede collaboration with external sources of knowledge, such as networks and alliances (Powell and Grodal 2005; Tether 2002). Thirdly, a risk-avoiding behaviour may limit the ability to seize business opportunities and hinder decisions concerning the adoption of disruptive technologies or risky business models. Finally, Pucci et al. (2017) highlighted that family involvement positively moderates R&D effectiveness, but only within the framework of local relationships. Institutional support may therefore be particularly critical for family firms, as it helps overcome specific limitations that are inherent to their governance structure.

This paper explores if and to what extent the institutional support provided by public institutions (government and agencies) and universities influences the adoption of new business models when corporate leadership is taken into account. Specifically, we study whether the Triple Helix model, i.e. the interaction between institutions, universities and industry within an entrepreneurial ecosystem, helps firms overcome the ownership-related disadvantages that inhibit - or delay - the adoption of business models consistent with the Industry 4.0 paradigm (henceforth, business model 4.0).

To the best of our knowledge, no studies have demonstrated empirically how the ability of a company to adopt or innovate its business model relates to both the nature of the firm leadership and the presence of institutional support. In addition, no ownership-driven mechanisms of business model change have been proposed to explain the ability of incumbent firms to modify their business profile when institutional support is explicitly taken into account.

This research attempts to address these gaps by studying the influence of company leadership and external support on the adoption of 4.0 business models in a sample of Italian manufacturing firms. We use the company relationship with public institutions and universities (Triple Helix) to identify differences in the adoption of 4.0 business models in specific types of ownership and management. To test our predictions, we draw on information from a survey carried out in 2019 by the Italian Union of Chambers of Commerce (Unioncamere) on a sample of 3000 Italian manufacturing firms. Firm-level information included in the survey is related to the investment in digital technologies, the adoption of 4.0 business models, the type of ownership and the relationship of the focal firm with institutions and universities. Following a consolidated line of research, we consider simultaneous interactions between the three actors (firms, government and university) as a source of the generation of new knowledge and resources crucial for innovation (Ranga and Etzkowitz 2013; Etzkowitz 2006). The evidence in the paper confirms the validity of this assumption.

Our estimation results show that despite family firms being very proactive in the introduction of 4.0 business models, family firms run by family CEOs (family management) come out as weak adopters of 4.0 business models. More specifically, family management – not ownership – comes out as the weakest form of company leadership in the development and use of 4.0 business models. However, when the influence of the Triple Helix is taken into account, the disadvantage of family management almost disappears, as the connection with institutions and universities increases the propensity of family CEOs to adopt 4.0 business models.

We found that the Triple Helix helps to overcome the managerial gaps that impede family leaders from acquiring superior technological assets and disruptive business models. This evidence confirms the role of the Triple Helix as a mechanism that offsets the different managerial abilities and innovation propensities of family CEOs and, more generally, confirms the appropriateness of this form of external support as a policy tool to deal with leadership-related shortcomings in the adoption of 4.0 business models.

The paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, we discuss the nexus between the Triple Helix and the adoption of disruptive technologies. We distinguish between family ownership and family management in the development of hypotheses, as we also do in the empirical analysis. Section 3 describes the dataset and estimation methods. Section 4 presents the variables used and summary statistics from the empirical analysis, and Sect. 5 presents the estimation results. Section 6 concludes and suggests future research.

2 Literature background and hypotheses

2.1 The Triple Helix and the emergence of disruptive technologies

2.1.1 The supporting role of the Triple Helix

The emergence of the "Triple Helix" paradigm (Etzkowitz and Leydesdorff 2000; Etzkowitz 2002; 2003) highlighted the key role of interactions between university, industry and government as a model for knowledge-based economies to overcome barriers that cannot be overcome by one entity alone.

The relationship between firms and universities is crucial for accessing and absorbing new knowledge for innovation purposes (Wang and Lu 2007). By collaborating with universities, firms can access complementary knowledge and experience, gain competitive benefits (D’Este et al., 2012), and reinforce internal capabilities (Daghfous 2004). Firms that establish partnerships with universities reach higher productivity levels compared with those with lower universities ties (Boardman 2008; Powell et al. 1996; Zucker et al. 1998; Stuart et al. 999, González-López et al. (2014); Rybnicek and Königsgruber (2019). Universities are thus a key actor in a regional innovation system. By increasing social interactions with other actors in the innovation ecosystem, universities can play an active role in supporting innovation, which then positively affects their reputation (Villani and Lechner 2020).

The participation of public institutions (government and agencies) can strengthen the cooperation even further (Mohnen and Hoareau 2003; Freeman 1987; Lundvall 1992; Nelson 1993; OECD 1999, Fagerberg and Verspagen 2009; Boardman 2009) by creating a local environment that is more favourable to innovation (Mars and Rios-Aguilar 2010). In addition to setting up policy actions (Leišytė and Fochler 2018), the government translates research into use, negotiates R&D contracts with universities and local providers (Edquist 2004), and also acts as a venture capitalist by providing financial resources for new business activities. Public institutions can also improve cross-fertilization targeted at bridging knowledge between different sectors and actors, generating consensus, and avoiding conflicts of interests. This collaboration also helps in integrating skills and enabling businesses to increase their own competencies, by favoring practical implementation and opportunities for knowledge exchange (Archer and Cameron, 2009; Doloreux and Parto 2005). The interplay between firms, industry and government can thus foster the innovation performance on the basis of how these actors interact rather than how they perform separately (Smith 1994).

2.1.2 The industry 4.0 paradigm

With the recent advent of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (Schwab 2017), the need to support firms’ competitiveness is even greater. Discontinuous technological change refers to a new technological paradigm that breaks down the current technological trajectory (Dosi 1982; Rosenbloom and Christensen 1994). This discontinuity is often considered as a "radical innovation of changing components, systems, techniques, or methods required for producing organizational outputs” (Lavie 2006: 154; Schumpeter, 1942). In fact, technological discontinuity is based on new knowledge and capabilities that can potentially shift products, firms, and transform old mechanisms and existing technologies into challenging processes in line with new market expectations (Anderson and Tushman 1990; Dahlin and Behrens 2005). The uncertainty connected to discontinuous change generates variations in the forms of adoption (Westphal et al. 1997; Goodrick and Salancik 1996), which may influence incumbent firms differently according to their heterogeneity and variety in the supply of goods, and in their motivations and cultural values (e.g. Bijker et al. 1987).

Since discontinuous technologies are value creators «that depart dramatically from the norm of continuous incremental innovation» (Anderson and Tushman 1990, p. 606) and from the traditional innovation trajectory, we believe that Industry 4.0, and its influence on the development of new business models, fully reflects the abovementioned concept and fits in its own right within the discontinuous technology paradigm.

Industry 4.0 is used to indicate the so-called Fourth industrial revolution (Schwab 2017). The term Industry 4.0 originates from the German government’s “Industrie 4.0” initiative to support the long-term competitiveness of the manufacturing sector (Kagermann et al. 2013). Industry 4.0 is referred to with different names in other countries, such as “Industrial Internet Consortium” or “Industrial Internet of Things” in the United States, “Internet Plus” or “Made in China 2025” in China and “Smart Manufacturing Innovation Strategy” or “Manufacturing Innovation 3.0” in South Korea. In Europe, it has been indicated as “Factories of the Future” by the European Commission, the “Future of Manufacturing” in the United Kingdom and “Industria 4.0 in Italy (Büchi et al. 2020; Müller et al. 2020; Müller et al. 2018). The two crucial advantages of the pervasiveness of Industry 4.0 are its integration and interoperability (Wei et al. 2014). The core technology of Industry 4.0 is represented by Cyber-Physical Systems, which are integrated into the value creation process and help the mixture between physical and digital processes (Kagermann et al. 2013). Industry 4.0 connects embedded systems, which generate a synergy between industry, business, and internal functions and processes. With the advent of Industry 4.0, technologies such as robotics, but also automation, production, sales and distribution methods have disrupted entire value chains, leading to the formation of new business ecosystems. The Industry 4.0 model is able of support various functions, from process optimization to new business models (Kagermann et al. 2013; Oesterreich and Teuteberg 2016).

This change also involves the use of new elements such as the industrial Internet of things (IoT) and digitalization to make firms more dynamic and flexible (Kagermann et al. 2013; Ghobakhloo 2018; Liao et al. 2017; OECD 2017; Evangelista et al. 2014. For a literature review see Oztemel et al. Gursev 2020). Research on Piedmont, a region in northwest Italy (Büchi et al. 2020), has highlighted the positive effects of an openness to Industry 4.0 on performance in terms of greater opportunities, such as higher production flexibility, speed, output capacity, quality, fewer costs and errors, and better customer opinions of products.

With the rapid spread of Industry 4.0, firms can leverage on external sources in collaborating for innovation rather than relying entirely on internal resources (Chesbrough 2006; Kellermanns and Hoy 2016). The innovation of the company relies on the extent to which the environment boosts knowledge transfer through networking among stakeholders, as well as skills, finance, advice and supply chain partners (OECD 2013). Collaboration with external sources of knowledge, such as networks, alliances and other forms of interaction, can foster firms to innovate and achieve technological upgrading (Powell and Grodal 2005; Tether 2002; Chen et al. 2011; Love and Roper 2001; Nieto and Santamaría 2007; Zeng et al. 2010; Rammer et al. 2009).

2.2 New technologies and family firms

Since success in technological innovation requires high-level expertise in business skills and managerial effectiveness (Covin and Slevin 1998; Kuratk et al. 1997; Xu et al. 2018; Liao et al. 2017; Puangpronpitag 2019), the beneficial influence of the external environment on individual firm performance can compensate for any lack of specific competencies and abilities. More generally, management skills and other complementary capabilities needed to face the changes brought about by the disruptive technologies are even more significant for Industry 4.0 (Martín et al. 2013), thus making governance-dependent gaps in the availability of resources and capabilities a significant issue. Footnote 1

König et al. (2012) show that the nexus between the adoption of discontinuous technologies and family firms has not been fully explored and the findings are still inconsistent. Among the many features of company governance, specific aspects of family leadership are crucial for the adoption of disruptive technologies. First, repetitive and unchanging business models are strong inhibitors in the recognition of discontinuous technologies. Family firms appear to have less flexible mental approaches than non-family firms due to the longer tenure of management (e.g., Berrone et al. 2010; Gómez-Mejía et al. 2001; Schulze et al. 2001), higher management homogeneity (Sirmon and Hitt 2003), lower involvement of outside actors in decision making processes (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007), and lower management turnover (Cho and Hambrick 2006). Moreover, family-owned companies are more likely to have concerns regarding the speed of adoption of discontinuous technologies.

Second, family firms present a lower level of formalization due to their high sense of sentiment and emotion (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2001), as well as their long-term targets that often drive them towards a non-formalized exploration of new opportunities (Carney 2005).

Third, according to the literature on socio-economic wealth (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007), family firms are more emotionally tied to existing assets. This partially explains their higher risk aversion (Naldi et al. 2007) mostly due to the dominance of non-economic goals over economic goals (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007; Gómez-Mejía et al. 2001), which can hinder the adoption of disruptive technologies. Finally, many scholars (Wu et al. 2015; Banalieva and Eddleston 2011) have focused on the lower levels of managerial capital in family firms.

All these aspects make family firms particularly suitable candidates for benefitting from outside partnerships and networks, in terms of facilitating knowledge sharing and supporting higher innovation output (Del Giudice et al. 2010). In the following section we explore the Triple Helix framework to put forward specific hypotheses on the relationship between external support and governance-related gaps arising from company leadership.

2.3 Disruptive technologies and family ownership

The adoption of new technologies – including business models suited to disruptive technologies – depends on the characteristics of firm ownership and management (Bank of Italy 2009; Giacomelli and Trento 2005; Bianchi et al. 2005; Bloom et al. 2008). A family can influence a firm in various ways (Astrachan et al. 2002), via both ownership and management (Astrachan et al. 2002; Cucculelli and Marchionne 2012). This section examines the effects of family ownership on the propensity to adopt disruptive technologies. We consider the role of family management in the next Section.

Family owners tend to value their firms for beyond purely financial reasons (Astrachan and Jaskiewicz 2008; Block 2009; Zellweger and Astrachan 2008). This includes investments in brands or sectors that are connected to the history and reputation of the family. Family owners may also gain non-financial benefits from investments in projects that create opportunities for future family generations, but that do not pay off in the immediate term (Casson 1999; James 1999; Tagiuri and Davis 1992). Non-financial goals may also lead to creating a positive firm culture as well as a strong sense of belonging within the business-owning family.

This greater emphasis on non-financial goals makes these individuals more concerned about the survival of the business itself (Kepner 1983; Lee and Rogoff 1996; Tagiuri and Davis 1992, 1996; Claessens et al. 2000; Claessens et al. 2002; Morck and Yeung, 2003, 2004). The shared goals of the business-owning family and of the firm itself may lead such owners to identify more strongly with the firm as a social entity than other types of owners, who are primarily focused on financial goals, and feel a greater degree of organizational identification (Ashforth and Mael 1989; Riketta 2005).

Family owners may be more concerned about the reputation of the firm and thus be more inclined than other owners to avoid reputation-damaging corporate actions, such as adopting risky innovations (Boone and Uysal 2018). Compared to other types of owners, family owners are thus more likely to care about their reputation for social responsibility in the community in which their firm is located. This greater concern for reputation makes them more fearful of the negative image associated with risky investment decisions.

We therefore formulated the following:

Hypothesis 1a

There is a negative relationship between family ownership and the likelihood of developing 4.0 business models.

By contrast, a number of theoretical and empirical analyses have stressed the beneficial influence of family ownership on the ability to innovate and bear the risk of disruptive innovation. The incentives provided by the ownership to managers, who are expected to act on behalf of shareholders plays an important role here. According to the agency theory (Schulze et al. 2001), the alignment between owners and managers helps in mitigating the negative influence of asymmetric information and incentives on the conduct of family managers, thus supporting innovation (Chrisman et al.2004; Gómez-Mejía et al. 2001; Jensen and Meckling 1976; Fama and Jensen 1983a; 1983b; Demsetz 1988; Ang et al. 2000). By contrast, conflicts in agency relationships might be significant for non-family managers, who are more likely to pursue their own goals rather than those of the owner (Fama and Jensen 1983b; Jensen and Meckling 1976).

Similarly, the concept of “familiness” (Habbershon and Williams 1999) and family capital (Hoffman et al. 2006) in the stewardship approach helps to explain why family firms run by family managers perform better than other firms with short-term incentives and interests (Davis et al., 2000; Miller and Breton-Miller 2005; Miller Le Breton-Miller 2006). Because of their long-term orientation, family owners pay more attention to stakeholders and the overall internal organization, thus benefitting from risk taking and innovation (Davis et al. 1997; Donaldson and Davis 1991; Fox and Hamilton 1994: Miller and Le Breton Miller, 2005).

Finally, the resource-based and knowledge-based views (Barney 1991; Grant 1991; Peteraf 1993) highlight the importance of knowledge transfer within family firms. Specifically, the stronger interaction between the family unit, business unit and individual family members fostered by family stakeholders creates a unique system of unique resources and capabilities (Chua et al. 1999; Zahra et al. 2004). These include commitment, trust, reputation, knowhow, valuable relationships, talent in innovation, corporate culture and organization (Cabrera-Suarez et al. 2001; Barney and Hansen 1994). This synergy positively influences the decision-making process (Gersick et al. 1997). Given these favorable arguments, we posit that:

Hypothesis 1b

There is a positive relationship between family ownership and the likelihood of developing 4.0 business models.

2.4 Disruptive technologies and family management

Family firms can be divided between firms run by family members and firms run by external managers (Le Breton-Miller et al. 2011). The type of management can be an important factor in determining the development of 4.0 business models, since the decision to involve family or non-family managers may influence the propensity to innovate in many ways. Among the most relevant are the resource management and deployment (Sirmon and Hitt 2003), the desired degree of risk accepted (Gómez-Mejía et al. 2007; Miller and Le Breton-Miller 2006; Naldi et al. 2007; Bianco et al. 2013; Chrisman et al. 2015), the role of debt financing (Miller and Le Breton-Miller 2006; Cabrera-Suárez et al. 2001; Carney 2005; Naldi et al. 2007; Villalonga and Amit 2006), short- and long-term company interests (Davis et al. 2000; Miller and Le Breton-Miller 2006; Manso 2011), and various other incentives (Ang et al. 2000; Demsetz 1988; Fama and Jensen 1983a, 1983b).

Family managers often share a long common history with the family firm and its actors. In many cases, they have grown up in the organization and learned skills and practices that are idiosyncratic to their organization (Block 2012). Kepner (1983) argues that the family and business systems in a family firm co-evolve and cannot be separated without great damage to one or both systems. A closer look at family management is thus crucial to understand whether and to what extent new technologies fit the strategic and organisational structure of the family firm.

Family managers are able to discover opportunities (Ardichvili et al. 2003; Shane and Venkataraman 2000) thanks to their capacity to take advantage of overlooked potentialities in well-known commercial and technological domains (Tang and Khan 2007; Patel and Fiet 2011). Despite not being significantly proactive in identifying opportunities, family firms are often more reactive in the subsequent phases, i.e. in identifying avenues that will aid their longevity (Zaefarian et al. 2016), and being better positioned to seize opportunities over time (Bhave 1994; Fiet et al. 2005). This legacy enables family managers to exploit new scientific areas and discover new technological knowledge (Shalley et al. 2015). Family managers may even adopt risky innovation strategies during industry maturity, given their strong involvement in the company and higher risk propensity in times of crisis (Gomez-Mejia et al. 2007; Hoskisson et al. 2017). Thus, we posit the following:

Hypothesis 2a

There is a positive relationship between family management and the likelihood of developing 4.0 business models.

The possible negative influence of family managers on innovation is mainly related to their willingness to avoid risk and their lower investment in human capital and education. The limited pool of talent available within the family, or the rivalry among family members, may adversely affect the managerial quality and business skills of family CEOs, who prefer safe innovation strategies and low risk initiatives (Schulze et al. 2001). In fact, Dohse et al. (2019) demonstrate the positive nexus between female owners and the probability of innovation, compared with female managers.

Non-family managers are different: they usually have more varied organizational and occupational experiences. In particular, they generally have wider experience outside the firm, they have often worked in large firms, and change jobs frequently. Most have completed formal and generic management education, and have been exposed to many innovations, which they are better equipped at managing.

According to Schulze et al. (2003), and Chrisman et al. (2004), non-family managers are able to improve performance because they tend to reduce excessive entrenchment and altruism that impede innovation. Second, when family management is predominant, there is a risk of pursuing different goals other than profit or firm value maximization, thus leading to mismanagement or under-management of the business (Levie and Lerner 2009; Schulze et al. 2003; Westhead and Howorth 2007; Chrisman et al. 2012). Third, non-family managers may avoid the problems of family members holding onto power and authority even at the expense of curbing the firm’s potential benefits (Kotlar et al. 2013). Fourth, non-family managers can provide new expertise, goals and perspectives and improve resource allocation, which may be overlooked by family members (Anderson and Reeb 2004; Dalton et al. 1998).Footnote 2 In summary, given the above arguments we posit that:

Hypothesis 2b

There is a negative relationship between family management and the likelihood of developing 4.0 business models.

2.5 The Triple Helix and family firms

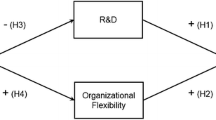

Most of the studies that have examined the nexus between family firms and innovation have highlighted moderator effects, such as the role of different generations (Werner et al. 2018, the openness to external stakeholders (Chlosta et al. 2012), family cohesiveness (Zahra 2012), and organizational flexibility (Broekaert et al. 2016).

However, despite the extensive research on innovation in family firms (for a recent discussion see Werner et al. 2018), to the best of our knowledge, studies are still lacking on the relationship between family ownership and external partnerships in relation to innovation under the lens of the Triple Helix.

The Triple Helix enhances the transition from a low-risk and low-development model to a higher-risk and higher-gain development model, fostering radical innovation, new growth opportunities and skills (Ranga and Etzkowitz 2013), and also shaping a broader perspective of innovation (Qian 2017). However, it would seem that only the simultaneous interactions between industry, governments and universities can generate a particular institutional pattern that produces new combinations of knowledge and resources for innovation, as each actor carries out not only its traditional functions, but can “take the role of the other” (Ranga and Etzkowitz 2013; Etzkowitz 2006).

The Triple Helix model is particularly strategic for family firms in overcoming management constraints as well as other gaps related to their ownership structure, values and culture (Wiklund and Shepherd 2003). By leveraging the collaboration between academia, government and industry (Etzkowitz 2008; Carayannis and Campbell 2010), family firms can improve their internal and external knowledge assets (Tranekjer 2017; Ferraris et al. 2017) and reduce the potential gap required by the Industry 4.0 strategy. As argued by Filieri and Alguezaui (2014) and Del Giudice and Maggioni (2014), this enables them to absorb knowledge for developing new ideas or improving the existing ones, also supporting new knowledge formation, which in turn positively affects the implementation of new business models.

By counterbalancing the negative effects of family ownership and management on innovation, the Triple Helix helps family firms to reduce the limitations inherent in their strategic and operational profile. The issue of reputation can be addressed by including the family firm in a larger network that favors social acceptance, and the negative influence of higher risk aversion can be reduced by defining an investment profile whose risk is in line with the risk propensity of the firm. Expert advice can thus be provided to family managers, which favors the exposure of family firms to the innovative ecosystem.

Collaborative innovation through the Triple Helix can therefore effectively overcome innovation barriers and provide crucial sources of competitive advantage for family firms (De Mattos et al. 2013; Hitt et al. 2000; Sirmon et al. 2008). We set the final hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 3

There is a positive moderating role of the Triple Helix and the likelihood of developing 4.0 business models by family-run firms

3 Data and methods

Our data source is a survey carried out by the Italian Union of Chambers of Commerce in mid-2019 on a sample of 3000 Italian manufacturing firms with at least five employees. The survey was conducted using the CATI method by a professional contractor in order to gather both qualitative and quantitative information on the firms. The sample represents about 2.4% of the entire Italian population in terms of firms and 3.6% in terms of employees. Specifically, the stratification considered three firm dimensions: (i) industry (24 divisions of the section C manufacturing sector of the Nace Rev.2 classification); (ii) size class in terms of employees (5–9, 10–19, 20–49, 50 and above); (iii) geographical location (North-West, North-East, Center, South). The data include information on ownership and management, investment in Industry 4.0, workforce characteristics, financial performance, internationalization, and relationship with suppliers and customers.

To study the probability of adopting a 4.0 business model, we ran multinomial probit regressions, as there were several different categories that the dependent variable could be classified with Footnote 3. For the purposes of our study, the dependent variable can have three different values, summarizing three different business statuses: (i) the firm has not adopted any 4.0 business models, (ii) the firm is planning to adopt 4.0 business models; and (iii) the firm has already adopted 4.0 business models. We used the non-adoption possibility as the base category.

Our empirical model is:

where pij is the probability that observation i will select alternative j, which is one of the three business statuses described above, dependent on a set of specific covariates. As heteroscedasticity can be an issue, we ensured consistency by selecting a larger sample size than the guidance put forward by Long and Ervin (2000). All models were estimated by the maximum likelihood.

We estimated separate models to test the “family-ownership effect” and the “family-management effect”. For the first, we estimated the influence of family ownership on the development of 4.0 business models (Hp 1a, Hp 1b); for the second, we analyzed the influence of family and external management within the subsample of family firms (Hp 2a, Hp 2b). Finally, we tested our key hypothesis on the moderating role of the Triple Helix (Hp 3) using interaction dummies for public institutions and universities on the baseline effect of the governance variables (ownership and management).

4 Description of variables and summary statistics

4.1 Dependent variable

Industry 4.0 is pushing firms to develop organizational structures that are suited to the new digital paradigm and to adopting 4.0 business models (Müller et al. 2018, 2020; Ibarra et al. 2018; Ehret and Wirtz 2017; Crnjac et al. 2017).

As the literature has not yet provided a clear definition of a 4.0 business model, we use the antecedents to a change in the organizational profile of the company as the identification mechanism (Bocken et al. 2014; Chesbrough 2007; Saebi et al. 2017; Schneckenberg et al. 2017; Velu and Stiles 2013).

Our definition of a 4.0 business model therefore includes any activity targeted at influencing one or more areas of value generation through digital technology (Müller et al. 2018). Specifically, activities included in value generation are: (i) digitization of the processes that favor data availability and the speed of decision-making (value creation); (ii) provision of customer-tailored products of a higher quality (value offer); (iii) comprehensive interactions between suppliers and customers, including involvement in product engineering and design (value capture). Our definition of development of a 4.0 business model, i.e. our dependent variable is thus based on the adoption (or planning) of one or more of these activities through digital technologies.

To consider the development stage of firms, we followed Zahra and George (2002) and Müller et al. (2020) by distinguishing between the planned and adoption stages. We therefore coded the development of new 4.0 business models using a three-level categorical structure: zero, if the firm has not developed any 4.0 business models (reference group); one, if the firm is planning to adopt a new 4.0 business model; two, if the firm has already adopted a 4.0 business model. The variables used in the analysis are summarized in Table 1.

4.2 Independent variables

4.2.1 Family firms

Several indicators have been used to measure family involvement in the empirical literature (Chua et al. 1999; Astrachan and Shanker 2003; Miller, Le Breton-Miller, Lester, & Cannella Jr, 2007). According to the ownership criteria (Donckels and Lambrecht 1999), a family-owned firm can be considered as a company whose owner is an individual or a family entity. In the subsample of family firms, we distinguish between firms run by family members (Family-owned Family Managed) and firms run by external managers (Family-owned External Managed) (Le Breton-Miller et al. 2011). This last group includes firms owned by a family that has hired an external CEO to run the business.

To test the “family ownership effect” we differentiated between non-family firms with family-owned firms run by external managers (Family-owned EM). This ensures that firms are compared under the same type of management, which is external, leaving ownership with the role of residual explanatory factor. To test the “family management effect”, we differentiated between family firms run by family members with family firms run by external CEOs. As both types of firms are owned by a family, the invariance in ownership structure highlights the influence of management on firm decisions.

4.2.2 Relationships

Relationships with external actors have been proven to be key factors for improving innovation and competitiveness, as in the case of collaborations between industry and universities (e.g. Chen 1994; Boardman 2008). Public institutions have also been shown to be another important driver of innovation, as they facilitate the improvement in technological capabilities (Freeman 1987; Lundvall 1992; Nelson 1993; OECD 1999; Mohnen and Hoareau 2002). We thus generated two binary variables: (i) University and (ii) Public institutions. In terms of academic cooperation, we coded 1 the variable University if the firm has a strong relationship with universities regarding research projects, cooperation agreements and technological transfer. Similarly, we coded 1 the variable Public Institutions if the firm has a strong relationship with chambers of commerce, local public authorities, government agencies, and other public institutions, and zero otherwise. Relationships with public institutions mainly include the provision of information, support for technological investments, and training.

4.2.3 Control variables

We included a set of control variables that might affect the propensity of family firms in adopting disruptive technologies (4.0 business models). To take into account the influence of human capital on business organization and IT adoption (Bresnahan et al. 2002; Falk 2002), we considered a variable that accounts for the share of employees with a university degree (Human capital). To capture the competences accumulated and learning mechanisms embedded within the company (Balabanis and Katsikea 2003), we included two continuous variables that account for the firm’s age (Age), measured as the years since the firm’s establishment; and firm size (Size), measured by the number of employees (Becheikh et al. 2006; Tsai and Wang 2005). We also included quadratic terms for age and size to account for potential non-linear relationships with our dependent variable.

In line with Barker and Mueller (2002), we controlled for the influence of a firm’s performance on strategic decisions (Turnover is a dummy variable coded as 1 if the firm had an increase in sales in the previous year). As stated by Nieto et al. (2015), internationalization is an important leverage for innovation (Ascani and Gagliardi 2020; Galende and De La Fuente 2003; Veugelers and Cassiman 1999). We thus included a dummy variable set to 1 if the firm exported (Export) and zero otherwise. To take into account that certification also influences a firm’s performance (Goel and Nelson 2020), we included a dummy variable (Quality certification): coded 1 if the firm has an internationally-recognized quality certification, and zero otherwise. Since the sectoral affiliation may reflect different technology opportunities (Mohnen and Therrien 2005), we also controlled for sectoral technological intensity (the dummy variable High-tech is coded 1 if the firm belongs to high/medium-high technology intensive sectors, according to the EUROSTAT taxonomy of manufacturing industries by technological intensity). Finally, we included four dummy variables (north-west, north-east, center, south) for the influence of geographical location on firms’ decisions (Del Monte and Papagni 2003).

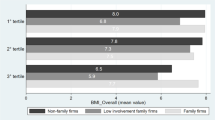

Table 2 reports the summary statistics. Family-owned firms run by family members represent the vast majority of the total (78.3%), whereas the share of family firms run by external managers is much lower (4.1%). The firms with strong relationships with universities represent about 16% of the total sample. A similar share was observed for relationships with public institutions.

The share of employees with a university degree is on average about 6%. Almost half the sample is made up of exporting firms (45.2%). The average age of the firms is 36 years, and the average size is 38 employees. About 17% of the sample firms have a quality certification. One-fifth of the firms (18.9%) operate in high or medium-high technology sectors. Most of the firms are located in the Northern Italy: one-third in the North-West (33.4%) and about one-third in the North-East (31.0%). A total of 20% of the sampled firms are located in Central Italy, and 16% in the South. Table 3 reports the correlation matrix. Correlations ranged from − 0.393 to 0.349. A moderate negative correlation was found between Family-owned FM and Family-owned EM (r = − 0.393) whereas a positive correlation was found between Public institutions and University (r = 0.349). Similarly, a moderate positive correlation emerged between Human capital and Size (r = 0.310).

5 Results

5.1 The role of family ownership and management

Table 4 reports the results. To estimate the influence of family ownership on the adoption of 4.0 business models, we tested the “ownership effect” by comparing non-family firms with family firms run by external managers (Family-owned EM), thus focusing on ownership-related effects. The estimated results (columns 1 and 2) show a positive and statistically significant effect of family ownership: family-owned firms are more likely than non-family firms to plan and adopt 4.0 business models. Overall, these results do not reject Hp 1b and support the positive relationship between family ownership and the likelihood of developing (planning and adopting) 4.0 business models. Footnote 4

As for the “family-management effect”, i.e. the influence of family management on the probability of developing 4.0 business models, the results are reported in columns 3–4. In these models, we compared family-owned firms run by family members (Family-owned and Family Managed) with family-owned firms run by external managers. In this case, the ownership effect is hypothesized as being constant across firms. Results show a negative impact of family management on the probability of adopting a 4.0 business model. The marginal effects are negative and statistically significant, in particular considering the adoption of new business models. This evidence does not reject Hypothesis 2b of a negative relationship between family management and the likelihood of developing 4.0 business models. This evidence is also in line with the findings by Dohse et al. (2019).

The estimated coefficients are negative for public institutions and not significant for universities (columns 1 and 2). By contrast, the influence of universities is positive and significant in terms of family management (Column 4). Overall, family ownership becomes a compensating factor in the case of weak institutional support, whereas relationships with universities play a role in the adoption of new business models only when the support by family managers is inadequate.

5.2 The influence of the Triple Helix

The full model, which includes interactions between components of the Triple Helix and the type of company governance, provides further evidence on the adoption of new business models (Hypothesis 3).

In the case of family ownership (Columns 5 and 6), the estimated results do not show any influence of the Triple Helix on the probability of adopting a new business model, as the coefficients are not significant and all very close to zero. The direct effect of public institutions is still negative, almost completely compensated for by the coefficient of family ownership.

By contrast, in the case of family management (Column 8), the combination of universities and public institutions plays a crucial role in the adoption of 4.0 business models: that is, the Triple Helix almost completely offsets the lower probability of adoption associated with family management. Unlike with family ownership, these findings show that the Triple Helix is crucial in firms run by family members, and emphasize the need for mainstream intermediaries to support family-managed firms.Footnote 5

The overall scenario that emerges from the regressions is consistent with Hp 3, that is the positive role of the Triple Helix in adopting 4.0 business models by family firms run by family members. This may be related to the better managerial ability of non-family managers, or the generic lower willingness to make risky investments by family managers, which slows down the adoption of 4.0 business models. Support from public Institutions and universities, within the Triple Helix framework, may help in filling the gaps of family management by transferring knowhow and providing other support that encompasses, for instance, education and training programmes to upgrade professional skills and the innovative behaviour of managers and employees.

6 Conclusions

The new and still unknown logic of value creation, offer and capture launched by the industrial paradigm 4.0 reveals gaps in the ability of individual firms to benefit from the digital revolution and pushes them to find new ways of generating and appropriating value. The supply of external knowledge and institutional support can help firms to be more proactive in changing or adapting their business models towards Industry 4.0 in order to gain a larger share of value from their business activities.

This paper shows that the interaction between firms, universities and public institutions is an important driver for developing 4.0 business models in family firms. Support from external sources of knowledge is crucial to upgrade internal capabilities, which, in turn, encourages family firms to become more proactively innovative. The evidence in this paper provides empirical support to the hypothesis that family firms run by family members are more likely to adopt disruptive technologies when the "Triple Helix" is at play, compared to when firms do not cooperate or only collaborate separately with institutions or universities. Being on average less prone to adopt risky and innovative business models, family firms run by internal CEOs are more likely to be involved in the exploitative strategies of new business models when they collaborate with public institutions and universities. This collaboration represents the catalyst for fruitful collaborations along a complex knowledge-chain, likely involving various stakeholders and requiring radical changes in the organisation of the company.

The weak reaction to paradigm changes and the need to support family firms in the adoption of innovative business models require a policy perspective. If the propensity to adopt disruptive technologies is also a cultural issue, the Triple Helix can act as a leveraging factor to convert a rigid entrepreneurial mindset into a more flexible and dynamic problem-solving approach. Openness to collaboration with public institutions and universities may improve a firm’s internal organizational culture and ensures the appropriate atmosphere of trust for adopting disruptive technologies.

This paper naturally has some limitations. Inferences from this study are limited by the data used in the empirical analysis, including the focus on industrial systems with a prevalence of small-sized firms. The cross-sectional approach also has a clear influence on causality. Finally, proxies for culture, as well as other confounding factors such as public incentives aimed at the technological upgrading of firms, could help in describing a more nuanced picture of the ecosystem.

Despite these limitations, we believe that our findings help to resolve some of the inconsistencies in existing research. To the best of our knowledge, this study represents the first case in which family firms' governance and ownership structure have been studied within the narrow framework of the Triple Helix model, aimed at understanding the ownership-related ability of a company to catch up with digital technologies.

Future research could benchmark these results with those obtained in other countries with different economic structures, to better understand the relevance of firm ownership in the adoption of new business models and technologies.

Notes

The discontinuous technological change (Gilbert, 2005) brought into by the new digital paradigm identifies dimensions of technology adoption (speed of adoption, resource commitment, and flexibility) that may be crucial for family firms.

On the specific issue of the influence of inside vs outside managers on innovation, the extant literature shows mixed results. The case study on Germany firms by Matzler, Veider, Hautz, & Stadler (2015) showed positive effects of family managers on innovation output (patent counts and citation of patents) and negative on innovation input (R&D). Analyzing Spanish firms, Nieto, Santamaria, & Fernandez (2015) found that family-management increases the likelihood of carrying out incremental innovation rather than radical ones. Cucculelli, Le Breton-Miller, and Miller (2016) found that family governance limits product innovation that renews technological competencies, while Minetti, Murro, and Paiella (2015) observed a negative relationship between product innovation and the share of external managers

The multinomial probit model is a tool to estimate processes characterized by alternatives that have correlated error terms. It provides several advantages over other discrete choice models, including the fact that it relaxes the unlikely independence from irrelevant alternative hypotheses, that is adding alternatives to the base scenario does not influence the relative odds between other alternatives.

Concerning control variables, the status of exporter is significantly associated to the adoption of a new business model, whereas human capital, sales growth and affiliation to high tech sectors are correlated to the intention of developing a 4.0 business model 4.0.

Although we are interested to the effect of the Triple Helix on the adoption of disruptive business models, we have also run estimates on separate interactions between family firms and Public institutions on the one side, and family firms and University on the other side. Consistently with our initial assumption, estimated results do not provide any significant evidence of a separate contribution from individual actors.

References

Almada-Lobo, F. (2016). The industry 4.0 revolution and the future of manufacturing execution systems (MES). Journal of Innovation Management, 3(4), 16–21.

Anderson, R. C., & Reeb, D. M. (2004). Board composition: Balancing family influence in S&P 500 firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49(2), 209–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/4131472.

Anderson, P., & Tushman, M. L. (1990). Technological discontinuities and dominant designs: A cyclical model of technological change. Administrative science quarterly, 35, 604–633.

Ang, J. S., Cole, R. A., & Lin, J. W. (2000). Agency costs and ownership structure. The Journal of Finance, 55(1), 81–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00201.

Archer, D., & Cameron, A. (2009). Collaborative Leadership – How to Succeed in an Interconnected World. Oxford: Butterworth- Heinemann.

Ardichvili, A., Cardozo, R., & Ray, S. (2003). A theory of entrepreneurial opportunity identification and development. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(01)00068-4.

Ascani, A., & Gagliardi, L. (2020). Asymmetric spillover effects from MNE investment. Journal of World Business, 55(6), 101146.

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1989.4278999.

Astrachan, J. H., & Jaskiewicz, P. (2008). Emotional returns and emotional costs in privately held family businesses: Advancing traditional business valuation. Family Business Review, 21(2), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2008.00115.x.

Astrachan, J. H., & Shanker, M. C. (2003). Family businesses’ contribution to the US economy: A closer look. Family Business Review, 16(3), 211–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/08944865030160030601.

Astrachan, J. H., Klein, S. B., & Smyrnios, K. X. (2002). The F-PEC scale of family influence: A proposal for solving the family business definition problem1. Family Business Review, 15(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2002.00045.x.

Balabanis, G. I., & Katsikea, E. S. (2003). Being an entrepreneurial exporter: Does it pay? International Business Review, 12(2), 233–252.

Banalieva, E. R., & Eddleston, K. A. (2011). Home-region focus and performance of family firms: The role of family vs non-family leaders. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(8), 1060–1072. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2011.28.

Bank of Italy (2009). Rapporto sulle tendenze nel sistema produttivo italiano (Questioni di Economia e Finanza No. 45). Retrieved from Bank of Italy Website: https://www.bancaditalia.it/pubblicazioni/qef/2009-0045/QEF_45.pdf.

Barker, V. L., III., & Mueller, G. C. (2002). CEO characteristics and firm R&D spending. Management Science, 48(6), 782–801. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.48.6.782.187.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108.

Barney, J. B., & Hansen, M. H. (1994). Trustworthiness as a source of competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 15(S1), 175–190. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250150912.

Becheikh, N., Landry, R., & Amara, N. (2006). Lessons from innovation empirical studies in the manufacturing sector: A systematic review of the literature from 1993–2003. Technovation, 26(5–6), 644–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2005.06.016.

Berrone, P., Cruz, C., Gomez-Mejia, L. R., & Larraza-Kintana, M. (2010). Socioemotional wealth and corporate responses to institutional pressures: Do family-controlled firms pollute less? Administrative science quarterly, 55(1), 82–113. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2010.55.1.82.

Bhave, M. P. (1994). A process model of entrepreneurial venture creation. Journal of business venturing, 9(3), 223–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(94)90031-0.

Bianchi, M., Bianco, M., Giacomelli, S., Pacces, A. M., & Trento, S. (2005). Proprietà e controllo delle imprese in Italia. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Bianco, M., Bontempi, M. E., Golinelli, R., & Parigi, G. (2013). Family firms investments, uncertainty and opacity. Small Business Economics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-012-9414-3.

Bijker, W. E., Hughes, T. P., & Pinch, T. J. (Eds.). (1987). The social construction of technological systems: New directions in the sociology and history of technology. London: MIT press.

Block, J. (2009). Long-term orientation of family firms: An investigation of R&D investments, downsizing practices, and executive pay. Springer Science & Business Media.

Block, J. (2012). R&D investments in family and founder firms: an agency perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(2), 248–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.09.003.

Bloom, N., Sadun, R., & Van Reenen, J. (2008). Measuring and explaining management practices in Italy. Rivista di Politica Economica, 98(2), 15–56.

Boardman, P. C. (2008). Beyond the stars: The impact of affiliation with university biotechnology centers on the industrial involvement of university scientists. Technovation, 28(5), 291–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2007.06.001.

Boardman, P. C. (2009). Government centrality to university–industry interactions: University research centers and the industry involvement of academic researchers. Research Policy, 38(10), 1505–1516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2009.09.008.

Bocken, N. M., Short, S. W., Rana, P., & Evans, S. (2014). A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. Journal of Cleaner Production, 65, 42–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.11.039.

Boone, A. L., Uysal, V. B. (2018). Reputational Concerns in the Market for Corporate Control. AFA 2013 San Diego Meetings Paper. 2018.

Bresnahan, T. F., Brynjolfsson, E., & Hitt, L. M. (2002). Information technology, workplace organization, and the demand for skilled labor: Firm-level evidence. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(1), 339–376. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355302753399526.

Broekaert, W., Andries, P., & Debackere, K. (2016). Innovation processes in family firms: the relevance of organizational flexibility. Small Business Economics, 47(3), 771–785. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9760-7.

Büchi, G., Cugno, M., & Castagnoli, R. (2020). Smart factory performance and Industry 4.0. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119790.

Cabrera-Suárez, K., De Saá-Pérez, P., & García-Almeida, D. (2001). The succession process from a resource and knowledge-based view of the family firm. Family Business Review, 14(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2001.00037.x.

Carayannis, E. G., & Campbell, D. F. (2010). Triple helix, quadruple helix and quintuple helix and how do knowledge, innovation and the environment relate to each other?: A proposed framework for a trans-disciplinary analysis of sustainable development and social ecology. International Journal of Social Ecology and Sustainable Development (IJSESD), 1(1), 41–69. https://doi.org/10.4018/jsesd.2010010105.

Carney, M. (2005). Corporate governance and competitive advantage in family–controlled firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(3), 249–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00081.x.

Casson, M. (1999). The economics of the family firm. Scandinavian Economic History Review, 47(1), 10–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/03585522.1999.10419802.

Chen, J., Chen, Y., & Vanhaverbeke, W. (2011). The influence of scope, depth, and orientation of external technology sources on the innovative performance of Chinese firms. Technovation, 31(8), 362–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2011.03.002.

Chesbrough, H. (2006). Open innovation: a new paradigm for understanding industrial innovation. Open innovation: Researching a new paradigm, 400, 0-19. In H. Chesbrough, W. Vanhaverbeke, % J. West (Eds.). Open innovation: Researching a new paradigm (pp. 1-12). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chesbrough, H. (2007). Business model innovation: It’s not just about technology anymore. Strategy and Leadership., 35(6), 12–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/10878570710833714.

Chlosta, S., Patzelt, H., Klein, S. B., & Dormann, C. (2012). Parental role models and the decision to become self-employed: The moderating effect of personality. Small Business Economics, 38(1), 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-010-9270-y.

Cho, T. S., & Hambrick, D. C. (2006). Attention as the mediator between top management team characteristics and strategic change: The case of airline deregulation. Organization Science, 17(4), 453–469. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1060.0192.

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., & Litz, R. A. (2004). Comparing the agency costs of family and non–family firms: Conceptual issues and exploratory evidence. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(4), 335–354. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2004.00049.x.

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., Pearson, A. W., & Barnett, T. (2012). Family involvement, family influence, and family-centered non-economic goals in small firms. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(2), 267–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00407.x.

Chrisman, J. J., Chua, J. H., De Massis, A., Frattini, F., & Wright, M. (2015). The ability and willingness paradox in family firm innovation. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 32(3), 310–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12207.

Chua, J. H., Chrisman, J. J., & Sharma, P. (1999). Defining the family business by behavior. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 23(4), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879902300402.

Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. (1988). The influence of organization structure on the utility of an entrepreneurial top management style. Journal of Management Studies, 25(3), 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1988.tb00033.x.

Crnjac, M., Veža, I., & Banduka, N. (2017). From concept to the introduction of industry 4.0. International Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management, 8(1), 21–30.

Cucculelli, M., & Marchionne, F. (2012). Market opportunities and owner identity: Are family firms different? Journal of Corporate Finance, 18(3), 476–495. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2012.02.001.

Cucculelli, M., Le Breton-Miller, I., & Miller, D. (2016). Product innovation, firm renewal and family governance. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 7(2), 90–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2016.02.001.

Daghfous, A. (2004). Absorptive capacity and the implementation of knowledge-intensive best practices. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 69(2), 21.

Dahlin, K. B., & Behrens, D. M. (2005). When is an invention really radical?: Defining and measuring technological radicalness. Research Policy, 34(5), 717–737.

Dalton, D. R., Daily, C. M., Ellstrand, A. E., & Johnson, J. L. (1998). Meta-analytic reviews of board composition, leadership structure, and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 19(3), 269–290.

Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., & Donaldson, L. (1997). Toward a stewardship theory of management. Academy of Management Review, 22(1), 20–47. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1997.9707180258.

Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., Mayer, R. C., & Tan, H. H. (2000). The trusted general manager and business unit performance: Empirical evidence of a competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 21(5), 563–576.

Del Giudice, M., & Maggioni, V. (2014). Managerial practices and operative directions of knowledge management within inter-firm networks: A global view. Journal of Knowledge Management, 18(5), 841–846. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-06-2014-0264.

Del Giudice, M., Della Peruta, M. R., & Carayannis, E. (2010). Knowledge and the family business. New York: Springer.

Del Monte, A., & Papagni, E. (2003). R&D and the growth of firms: empirical analysis of a panel of Italian firms. Research Policy, 32(6), 1003–1014.

De Mattos, C., Burgess, T. F., & Shaw, N. E. (2013). The impact of R&D-specific factors on the attractiveness of small-and medium-sized enterprises as partners vis-à-vis alliance formation in large emerging economies. R&D Management, 43(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2012.00699.x.

Demsetz, H. (1988). Ownership, control and the firm: The organization of economic activity. Oxford, UK: Basil Blackwell.

D’Este, P., Mahdi, S., Neely, A., & Rentocchini, F. (2012). Inventors and entrepreneurs in academia: What types of skills and experience matter? Technovation, 32(5), 293–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2011.12.005.

Dohse, D., Goel, R. K., & Nelson, M. A. (2019). Female owners versus female managers: Who is better at introducing innovations? Journal of Technology Transfer, 44, 520–539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-018-9679-z.

Doloreux, D., & Parto, S. (2005). Regional innovation systems: Current discourse and unresolved issues. Technology in Society, 27(2), 133–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2005.01.002.

Donaldson, L., & Davis, J. H. (1991). Stewardship theory or agency theory: CEO governance and shareholder returns. Australian Journal of Management, 16(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/031289629101600103.

Donckels, R., & Lambrecht, J. (1999). The re-emergence of family-based enterprises in east central Europe: What can be learned from family business research in the Western world? Family Business Review, 12(2), 171–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1999.00171.x.

Dosi, G. (1982). Technological paradigms and technological trajectories. Research Policy, 2(3), I47-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-7333(82)90016-6.

Dunning, J. H. (1998). Location and the multinational enterprise: A neglected factor? Journal of International Business Studies, 29(1), 45–66. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490024.

Dyer, W. G. (1989). Integrating professional management into a family owned business. Family Business Review, 2(3), 221–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1989.00221.x.

Edquist, C. (2004). Systems of Innovation: Perspectives and Challenges. In J. Fagerberg, D. Mowery & RR Nelson (Eds.). Oxford Handbook of Innovation (pp. 181-208). Oxford University Press.

Ehret, M., & Wirtz, J. (2017). Unlocking value from machines: Business models and the industrial Internet of things. Journal of Marketing Management, 33(1–2), 111–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2016.1248041

Etzkowitz, H. (2002). Incubation of incubators: Innovation as a triple helix of university-industry-government networks. Science and Public Policy, 29(2), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.3152/147154302781781056.

Etzkowitz, H. (2003). Innovation in innovation: The triple helix of university-industry-government relations. Social Science Information, 42(3), 293–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/05390184030423002.

Etzkowitz, H. (2006). The new visible hand: An assisted linear model of science and innovation policy. Science and public policy, 33(5), 310–320. https://doi.org/10.3152/147154306781778911.

Etzkowitz, H. (2008). The triple helix: Industry, university, and government in innovation. Social Science Information, 42(3), 293–337.

Etzkowitz, H., & Leydesdorff, L. (2000). The dynamics of innovation: From national systems and “Mode 2” to a triple helix of university–industry–government relations. Research Policy, 29(2), 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(99)00055-4.

Evangelista, R., Guerrieri, P., & Meliciani, V. (2014). The economic impact of digital technologies in Europe. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 23(8), 802–824. https://doi.org/10.1080/10438599.2014.918438.

Fagerberg, J., & Verspagen, B. (2009). Innovation studies: The emerging structure of a new scientific field. Research Policy, 38(2), 218–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2008.12.006.

Falk, M. (2002). Endogenous organizational change and the expected demand for different skill groups. Applied Economics Letters, 9(7), 419–423. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504850110088141.

Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. C. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. The Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 301–325. https://doi.org/10.1086/467037.

Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. C. (1983). Agency problems and residual claims. The Journal of Law and Economics, 26(2), 327–349. https://doi.org/10.1086/467038.

Ferraris, A., Santoro, G., & Dezi, L. (2017). How MNC’s subsidiaries may improve their innovative performance? The role of external sources and knowledge management capabilities. Journal of Knowledge Management, 21(3), 540–552. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-09-2016-0411.

Fiet, J. O., Piskounov, A., & Patel, P. C. (2005). Still searching (systematically) 1 for entrepreneurial discoveries. Small Business Economics, 25(5), 489–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-004-2277-5.

Filieri, R., & Alguezaui, S. (2014). Structural social capital and innovation Is knowledge transfer the missing link? Journal of Knowledge Management, 18(4), 728–757.

Fox, M. A., & Hamilton, R. T. (1994). Ownership and diversification: Agency theory or stewardship theory. Journal of Management Studies, 31(1), 69–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1994.tb00333.x.

Freeman, C. (1987). Technology and economic performance: Lessons from Japan. London, England: Pinter Publishers.

Galende, J., & de la Fuente, J. M. (2003). Internal factors determining a firm’s innovative behaviour. Research Policy, 32(5), 715–736. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00082-3.

Gebauer, H., Worch, H., & Truffer, B. (2012). Absorptive capacity, learning processes and combinative capabilities as determinants of strategic innovation. European Management Journal, 30(1), 57–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2011.10.004.

Gersick, K. E., Davis, J. A., Hampton, M. M., & Lansberg, I. (1997). Generation to generation: life cycles of the family business. Harvard: Harvard Business Press.

Ghobakhloo, M. (2018). The future of manufacturing industry: A strategic roadmap toward Industry 4.0. Journal of Manufacturing Technology Management., 29(6), 910–936.

Giacomelli, S., and Trento, S. (2005). Proprietà, controllo e trasferimenti nelle imprese italiane: Cosa è cambiato nel decennio 1993-2003? (Bank of Italy Working Papers No. 550). Retrieved from Bank of Italy website: https://www.bancaditalia.it/pubblicazioni/temi-discussione/2005/2005-0550/tema_550.pdf.

Gilbert, C. G. (2005). Unbundling the structure of inertia: Resource versus routine rigidity. Academy of Management Journal, 48(5), 741–763. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2005.18803920.

Goel, R. K., & Nelson, M. A. (2020). Do external quality certifications improve firms’ conduct? International evidence from manufacturing and service industries. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 76, 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.qref.2019.03.006.

Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Núñez-Nickel, M., Gutierrez I. (2001). The role of family ties in agency contracts. Academy of Management Journal, 44(1), 81–95.

Gómez-Mejía, L. R., Haynes, K. T., Núñez-Nickel, M., Jacobson, K. J., & Moyano-Fuentes, J. (2007). Socioemotional wealth and business risks in family-controlled firms: Evidence from Spanish olive oil mills. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52(1), 106–137. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.52.1.106.

Gonzalez-Lopez, M., Dileo, I., & Losurdo, F. (2014). University-industry collaboration in the European regional context: the cases of Galicia and Apulia region. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation, 10(3), 57–87. https://doi.org/10.7341/20141033.

Goodrick, E., & Salancik, G. R. (1996). Organizational discretion in responding to institutional practices: Hospitals and cesarean births. Administrative Science Quarterly. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393984.

Grant, R. M. (1991). The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for strategy formulation. California Management Review, 33(3), 114–135. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166664.

Habbershon, T. G., & Williams, M. L. (1999). A resource-based framework for assessing the strategic advantages of family firms. Family Business Review, 12(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1999.00001.x.

Hitt, M. A., Dacin, M. T., Levitas, E., Arregle, J. L., & Borza, A. (2000). Partner selection in emerging and developed market contexts: Resource-based and organizational learning perspectives. Academy of Management Journal, 43(3), 449–467. https://doi.org/10.5465/1556404.

Hoffman, J., Hoelscher, M., & Sorenson, R. (2006). Achieving sustained competitive advantage: A family capital theory. Family Business Review, 19(2), 135–145.

Hoskisson, R. E., Chirico, F., Zyung, J. D., & Gambeta, E. (2017). Managerial Risk Taking: A Multitheoretical Review and Future Research Agenda. Journal of Management, 43(1), 137–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316671583.

Ibarra, D., Ganzarain, J., & Igartua, J. I. (2018). Business model innovation through Industry 4.0: A review. Procedia Manufacturing, 22, 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.promfg.2018.03.002.

James, H. S. (1999). Owner as manager, extended horizons and the family firm. International journal of the economics of business, 6(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/13571519984304.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X.

Kagermann, H., Wahlster, W., & Helbig, J. (2013). Recommendations for implementing the strategic initiative INDUSTRIE 4.0. Final report of the Industrie 4.0 Working Group. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Acatech.

Kellermanns, F. W., & Hoy, F. (Eds.). (2016). The routledge companion to family business. New York: Routledge.

Kepner, E. (1983). The family and the firm: A coevolutionary perspective. Organizational Dynamics, 12(1), 57–70.

König, A., Schulte, M., & Enders, A. (2012). Inertia in response to non-paradigmatic change: The case of meta-organizations. Research Policy, 41(8), 1325–1343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2012.03.006.

Kontinen, T., & Ojala, A. (2010). The internationalization of family businesses: A review of extant research. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 1(2), 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfbs.2010.04.001.

Kontinen, T., & Ojala, A. (2011). International opportunity recognition among small and medium-sized family firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 49(3), 490–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2011.00326.x.

Kotlar, J., De Massis, A., Frattini, F., Bianchi, M., & Fang, H. (2013). Technology acquisition in family and nonfamily firms: A longitudinal analysis of Spanish manufacturing firms. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(6), 1073–1088. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12046.

Kuratko, D. F., Hornsby, J. S., & Naffziger, D. W. (1997). An examination of owner’s goals in sustaining entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business Management, 35(1), 24–33.

Lane, P. J., Koka, B. R., & Pathak, S. (2006). The reification of absorptive capacity: A critical review and rejuvenation of the construct. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 833–863. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.22527456.

Lavie, D. (2006). The competitive advantage of interconnected firms: An extension of the resource-based view. The Academy of Management Review, 31(3), 638–658.

Le Breton-Miller, I., Miller, D., & Lester, R. H. (2011). Stewardship or agency? A social embeddedness reconciliation of conduct and performance in public family businesses. Organization Science, 22(3), 704–721. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0541.

Lee, M. S., & Rogoff, E. G. (1996). Research note: Comparison of small businesses with family participation versus small businesses without family participation: An investigation of differences in goals, attitudes, and family/business conflict. Family Business Review, 9(4), 423–437. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1996.00423.x.

Leišytė, L., & Fochler, M. (2018). Topical collection of the triple helix journal: Agents of change in university-industry-government-society relationships. Triple Helix, 5, 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40604-018-0056-6.

Levie, J., & Lerner, M. (2009). Resource mobilization and performance in family and nonfamily businesses in the United Kingdom. Family Business Review, 22(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486508328812.

Liao, Y., Deschamps, F., Loures, E. D. F. R., & Ramos, L. F. P. (2017). Past, present and future of Industry 4.0-a systematic literature review and research agenda proposal. International Journal of Production Research, 55(12), 3609–3629.

Li, H., & Atuahene-Gima, K. (2001). Product innovation strategy and the performance of new technology ventures in China. Academy of Management Journal, 44(6), 1123–1134. https://doi.org/10.5465/3069392.

Long S. J., & Ervin, L. H. (2000) Using heteroscedasticity consistent standard errors in the linear regression model. The American Statistician, 54(3), 217–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.2000.10474549.

Love, J. H., & Roper, S. (2001). Outsourcing in the innovation process: Locational and strategic determinants. Papers in Regional Science, 80(3), 317–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1435-5597.2001.tb01802.x.

Lundvall, B. A. (1992). National innovation system: Towards a theory of innovation and interactive learning. London, England: Pinter Publishers.

Manso, G. (2011). Motivating innovation. The Journal of Finance, 66(5), 1823–1860. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01688.x.

Mars, M. M., & Rios-Aguilar, C. (2010). Academic entrepreneurship (re) defined: significance and implications for the scholarship of higher education. Higher Education, 59(4), 441–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-009-9258-1.

Martín-Rojas, R., García-Morales, V. J., & Bolívar-Ramos, M. T. (2013). Influence of technological support, skills and competencies, and learning on corporate entrepreneurship in European technology firms. Technovation, 33(12), 417–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2013.08.002.

Matzler, K., Veider, V., Hautz, J., & Stadler, C. (2015). The impact of family ownership, management, and governance on innovation. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 32(3), 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12202.

Ma, Z., Yu, M., Gao, C., Zhou, J., & Yang, Z. (2014). Institutional constraints of product innovation in China: Evidence from international joint ventures. Journal of Business Research, 68(5), 949–956.

Miller, D., & Le Breton-Miller, I. (2005). Managing for the long run: Lessons in competitive advantage from great family businesses. Harvard: Harvard Business Press.

Miller, D., & Le Breton-Miller, I. (2006). Family governance and firm performance: Agency, stewardship, and capabilities. Family Business Review, 19(1), 73–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2006.00063.x.

Miller, D., Le Breton-Miller, I., Lester, R. H., & Cannella, A. A., Jr. (2007). Are family firms really superior performers? Journal of Corporate Finance, 13(5), 829–858. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2007.03.004.

Minetti, R., Murro, P., & Paiella, M. (2015). Ownership structure, governance, and innovation. European Economic Review, 80, 165–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2015.09.007.

Mohnen, P., & Hoareau, C. (2003). What type of enterprise forges close links with universities and government labs? Evidence from CIS 2. Managerial and Decision Economics, 24(2–3), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.1086.

Mohnen, P., and Therrien, P. (2005). Comparing the innovation performance in Canadian, French and German manufacturing enterprises, mimeo.

Morck, R., & Yeung, B. (2003). Agency problems in large family business groups. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 27(4), 367–382. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-8520.t01-1-00015.

Morck, R., & Yeung, B. (2004). Family control and the rent–seeking society. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(4), 391–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2004.00053.x.