Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this systematic review is to identify vocational rehabilitation (VR) interventions that are effective to enhance return-to-work (RTW) for people on long-term sick leave (> 90 days) and to identify main elements of these interventions.

Methods

Six electronic databases were searched for peer-reviewed studies published up to February 2022. Each article was screened independently by two different reviewers. Thereafter, one author performed the data-extraction which was checked by another author. The EPHPP quality assessment tool was used to appraise the methodological quality of the studies.

Results

11.837 articles were identified. 21 articles were included in the review, which described 25 interventions. Results showed that ten interventions were more effective than usual care on RTW. Two interventions had mixed results. The effective interventions varied widely in content, but were often more extensive than usual care. Common elements of the effective interventions were: coaching, counseling and motivational interviewing, planning return to work, placing the worker in work or teaching practical skills and advising at the workplace. However, these elements were also common in interventions that were not effective on RTW compared to usual care and can therefore not explain why certain interventions are effective and others are not.

Conclusion

The effective interventions included in this study were often quite extensive and aimed at multiple phases of the RTW-process of the worker. In the future, researchers need to describe the population and the content of the investigated interventions more elaborate to be able to better compare VR interventions and determine what elements make interventions effective.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Long-term sickness absence has consequences for a person’s social and psychological well-being [1,2,3] and leads to high costs for society [4, 5]. Thus, it is important for these people to return to work sustainably as fast as possible. To increase their chances of returning to work, they are often supported in their return to work process, by offering them vocational rehabilitation (VR) interventions. Scientific evidence for the elements that these VR interventions should consist of to make them effective is lacking.

Literature shows that VR interventions are most effective if they are offered early in the return to work (RTW)-process [6] and thus prevent people from becoming long-term work disabled. These studies show that a focus on RTW, behavioral activation, and on psychoeducation [7] and a multidisciplinary approach [6] are elements of effective VR interventions for people with a shorter sick leave duration. However even though there are examples of interventions that are effective for people with a longer duration of sick leave [8], it remains to be seen if these contain the same elements. A reason why different interventions are effective in a later stage of the RTW-process could be that people on long-term sick leave often experience multiple problems that play an important role in prohibiting them from returning to work [8, 9] that take more time to address. On top of this, they often suffer from multiple disorders [10], experience multiple psychosocial problems [11] and multiple social disadvantages [12] in comparison to people with shorter sick leave. VR interventions specifically targeting people on long-term sick leave should address these problems, to increase work participation of this group.

Currently, there are no reviews available that explore intervention elements of VR interventions that are effective on RTW for people on long-term sick leave, however a few reviews investigated which type of interventions are effective on RTW. A review by Aasdahl and Fimland [8] showed that more complex interventions, such as a combination of an occupational intervention and a clinical intervention, are effective on RTW for people with a long-term illness. An overview of systematic reviews by Levack [13] to examine the effectiveness of vocational intervention for people with a chronic illness on returning and maintaining work, showed that supported employment is an effective intervention for people with chronic illness. For other VR interventions no final conclusion was reached, due to a lack of high-quality studies.

In order to better understand why certain VR interventions are effective to support people on long-term sick leave with their return to work, while others are not, it is important to identify elements of these interventions that might explain their effectiveness. This insight can be used to develop more effective VR interventions. The only review that investigated the elements of effective interventions for people on longer-term sick leave focused exclusively on mental disorders [1]. This study showed that interventions with contact to the workplace (e.g. refamiliarization with workplace) and multicomponent interventions are effective. It is of interest to see if these elements are also present in interventions that are effective for people on long-term sick leave because of a wide range of disorders.

This review aims to identify which VR interventions are effective for the RTW of people on long-term sick leave or receiving a work disability pension for more than 90 days, regardless of the type of disorder they have. Additionally, this review aims to identify the main elements of these effective VR interventions in comparison to the usual care.

Methods

We performed a systematic literature review. We included studies that investigated the effect of VR interventions on RTW among long-term (> 90 days) sick-listed workers in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement ([14]; www.prisma-statement.org). A protocol of this review was registered at PROSPERO (CRD42022104283).

Search Strategy

A comprehensive search was performed in the bibliographic databases PubMed, Embase.com, APA PsycInfo (via Ebsco), Cinahl (via Ebsco), Scopus and the Cochrane Library from inception to February 7th 2022, in collaboration with a medical librarian (LS). Search terms included controlled terms (MeSH in PubMed, Emtree in Embase, Thesaurus terms in PsycInfo and Cinahl Headings in Cinahl) as well as free text terms. The following terms were used (including synonyms and closely related words) as index terms or free-text words: ‘return to work’ and ‘disability insurance’ and ‘interventions’. We used four blocks in our search strategy (appendix 1) to search studies that fit our PICO. Block 1 (e.g. absenteeism) and 2 (e.g. disability insurance) described the population and outcome, block 3 described the type of intervention (e.g. vocational rehabilitation) and block 4 described the type of study (e.g. controlled clinical trial). Since we included all types of usual care as control condition we did not include terms referring to a certain type of control. A search filter was applied to limit results to randomized controlled trials. The search was performed without date restrictions. Duplicate articles were excluded by a medical information specialist (LS) using Endnote X20.0.1 (Clarivatetm), following the Amsterdam Efficient Deduplication (AED)-method [15, 16]. The references of the included articles and known systematic literature reviews [6,7,8, 17, 18] on the same topic were checked for additional relevant studies. The full search strategies for all databases can be found in the Supplementary Information (Appendix 1).

Selection Process

Two reviewers (CdG and MdMB) independently screened all potentially relevant titles and abstracts for eligibility using Rayyan [19]. Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (i) Employees and former employees of working age (18–67 years) who were (partially) sick-listed or received a work disability pension for at least 90 days on average at baseline, and who were absent from work for either work-related or non-work-related reasons. Studies which did not mention the sick leave duration of the participants or which included veterans were excluded; (ii) Interventions aimed at enhancing return to work or vocational rehabilitation. Medical interventions aimed at the treatment of the disease (e.g. drugs, surgeries) were excluded; (iii) Randomized controlled trial; (iv) Study involving RTW-related outcome measures (e.g. return-to-work, work retention, absenteeism, work status, competitive employment, time to RTW). Studies that were not published in a peer-reviewed academic journal or written in a different language then English were excluded. After screening based on title and abstract, the full text of the articles were independently checked by the two reviewers for the eligibility criteria. In case of disagreement, the disagreement was solved through discussion. If there was no consensus after discussion, a third reviewer (MH) decided if the article should be included in the review.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

One author (CdG) extracted the data from the studies. This data was checked by another reviewer (MdMB). In case of discrepancies in the data extraction, the data extraction was discussed until consensus was reached. Data extraction to identify the different elements of the interventions was conducted by reviewer CdG and reviewer JvR, independently. Differences between the reviewers was discussed with reviewer MH.

Due to the expected heterogeneity of the included interventions a narrative synthesis was conducted based on the steps developed by Popay et al. [20]: 1) developing a preliminary synthesis, 2) exploring relationships in the data and 3) assessing the robustness of the synthesis product. In order to develop a preliminary synthesis and explore relationships in the data, we extracted data from the articles on general study elements (e.g. authors, year of publication, study design, type of outcome measure) and participant elements (number of participants, age, gender, type of disease, average sick leave duration, job elements). Next, the elements of the interventions were extracted from the included articles using a deductive synthesis. Based on the elements of the first six analyzed articles and categories used in three other reviews [6, 7, 21] a framework was developed. The elements of the other articles were categorized according to this framework. If elements did not fit in the framework, new categories were added. The intervention elements according to the framework are described in Table 1.

We described the strength of our evidence based on the quality and quantity of the primary studies included in the review. Two reviewers (CdG and MdMB) independently evaluated the methodological quality of the full text papers using the EPHPP quality assessment [22]. The EPHPP tool was used to assess the quality of a study on six categories (selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods and withdrawals and drop-outs). For each category the studies were scored weak, moderate or strong. Based on these ratings a global rating was calculated. Studies received a strong global rating if they had no categories with a weak rating, a moderate global rating if they had one category with a weak rating or a weak global rating if they had two or more categories with a weak rating. The construct and content validity of the EPHPP tool have been demonstrated [23]. Differences in judgement were resolved through a consensus procedure. If consensus could not be reached, the item was discussed with reviewer MH and resolved.

Results

Study Search and Inclusion

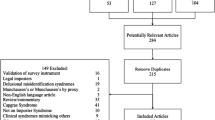

The literature search generated a total of 23,740 references: 4230 in PubMed, 3940 in Embase, 2211 in Cinahl, 975 in PsycInfo, 4886 in the Cochrane Library and 7498 in Scopus. The flow chart of the search and selection process is presented in Fig. 1. We identified 333 possible relevant articles in the database of which the full-text was assessed. During the search we identified 38 relevant systematic reviews of which the reference lists were assessed for eligible studies. At the end we also checked the reference lists of the eligible articles to identify additional articles. In total we checked the full text of 389 studies. Twenty-one studies were included. The 21 studies describe 25 different interventions. For one study a subsample of workers on long-term sick leave was used [24]. For another study the sample was divided in two subsamples based on sick leave duration (average sick leave duration of 3 months and 26 months) [25], we describe the outcomes of the intervention for both subsamples.

Quality of Included Studies

Quality ratings are shown in Table 2. Of the 21 identified articles, eight were assessed as weak in the global rating [26, 28,29,30,31,32,33, 45], nine studies were assessed as moderate [24, 27, 34,35,36,37,38,39,40], and four studies were assessed as having a strong quality [25, 41, 42, 44]. Selection bias was present in many studies due to a low participation rate of the invited participants. Since only randomized controlled trials (RCT’s) were included, the study design was mostly assessed as strong. However, if the randomization was not properly described, study design was rated ‘moderate’. Blinding was often assessed as weak due to participants not being blinded to the condition (intervention or usual care group) they were allocated. The data collection methods were often assessed as weak, because self-reported questionnaires were used to measure return-to-work instead of more reliable methods, such as using data obtained from registries of social security institutes.

General Study Characteristics

General characteristics of the studies are presented in Table 3. Almost all studies had two arms (intervention and control) except for four studies with three arms [26, 30, 34, 36]. The number of participants ranged from 38 [32] to 2238 [45]. The mean sick leave duration ranged from 3 months [25] to 12.3 years [31]. Most studies (n = 12) included more women than men. Two studies [25, 36] only included women, all other studies included both men and women. The mean age ranged from 32.3 years [27] to 49.1 years [37]. Studies were mostly executed in Northern Europe (n = 16). Most common RTW outcome measures were RTW status, duration until RTW and claim duration. Only studies involving populations on sick-leave with a mean or median duration of more than 90 days were included, but within these studies the length of sick-leave varied considerably. Twenty-two interventions could be categorized based on the average or median sick leave duration of their sample or inclusion criterion. Nine studies concerned people with a sick leave duration with a median/mean of more than 3 months and less than one year. Twelve studies had a population on sick leave for 1 year or more (range: 12 months to 12.9 years). One study included both groups. Follow-up duration of the studies varied from “at program discharge” to 36 months. Eighteen interventions followed participants for at least 12 months (range 12 months-36 months).

Study Results

Of the 25 different interventions, ten interventions were effective in improving the RTW outcome compared to usual care (Table 3). Two interventions showed mixed results; one intervention [40] showed that compared to usual care the intervention (advice from the psychiatrist to the occupational physician about RTW) was only effective on return to work rates at three months (58% versus 44%), while at six months this difference had disappeared (~ 85% in both groups). Another intervention, a cognitive behavioural RTW-program [25] showed only to be effective for people with relatively short-term sick leave (mean 3 months) but not for people with a long-term sick leave (mean 26 months). In addition, there was one study which reported a positive effect in favor of the usual care group at 6 months, compared to the group receiving physical therapy, but this effect was not present at 12 months [30].

Elements of Interventions

Table 4 shows the characteristics and the elements of the interventions that were studied. Both effective and not effective studies varied widely in type of intervention. In general, studies examined the effect of psychosocial interventions, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) [25, 30, 31, 34] and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) [26, 36]. There were no differences in type of intervention when comparing the effective to the not effective interventions. Most (n = 15) of the interventions of which the duration was described (n = 20), lasted between 1 and 6 months. Six of these interventions were effective. Many interventions (n = 11, of which 3 effective) had a high intensity, meaning they contained 12 or more hours of vocational rehabilitation. A minority of interventions were solely group interventions (n = 3, n = 1 effective). Only a few (n = 3 of which 1 was effective) contained homework assignments. There were no notable differences in duration, intensity and type of intervention between the effective and the not effective interventions.

All included interventions were aimed at preparing the worker to return to work. Nearly half of the interventions were also aimed at helping the worker find work (8 interventions) or remain in work (12 interventions). Six interventions included all three aims: preparing the worker to RTW, helping the worker find work and helping the worker remain in work. Of the six interventions that included all three aims, two were effective on RTW [42, 45], while the other four were not [25, 33, 40, 44]. In the next paragraphs, the content of the interventions for each main aim is further described.

Main Aim 1: Preparing the Worker for Return to Work

Ten of the 25 interventions aimed at preparing the worker to return to work were effective on RTW compared to the usual care. The effective interventions all contained various types of activities that were aimed at preparing the worker to return to work: these often contained a form of counselling, coaching or motivational interviewing (n = 6) or education (n = 4), and often started with assessing the underlying problems for RTW of the worker (n = 5). In general, studies that were aimed at preparing the worker for returning to work often included assessing the underlying problems for RTW of the worker (n = 14) and formulating a rehabilitation plan aimed at RTW, which is often based on this assessment (n = 11). This, however, was not necessarily an element in effective interventions. Only two interventions that were effective included both of these activities, while ten ineffective interventions included this combination of activities. The interventions that contained a psychological intervention based on CBT, ACT or cognitive restructuring (n = 11) were often aimed at managing pain or being able to cope with problems. Only three of these interventions were effective. There was no clear difference in the content of the psychological interventions between effective and not effective studies. The effective interventions that contained a physical aspect included (among others) graded activity [37, 41] and work hardening [27], but again, there was no clear difference in the content of effective and non-effective physical interventions.

Main Aim 2: Helping the Worker Find Work

Eight interventions included elements focused on helping the worker find work. Three of these interventions were effective to improve the RTW outcome compared to the usual care (the combined intervention of study [34] and studies [42, 45]. The effective interventions contained planning returning to work with the worker [34], placing the worker in work [45] or teaching practical skills and helping the worker look for work [42]. However, these elements were comparable to those of the ineffective interventions.

Main Aim 3: Helping the Worker Remain in Work

Twelve of the interventions included elements focused on helping the worker remain in the workplace, of which four were effective on the RTW outcome compared to the usual care [27, 41, 42, 45]. These effective interventions existed of advising at the workplace [27, 41, 42] or advising on working circumstances at the workplace and a follow-up at the workplace [45]. Other interventions that included advising at the workplace, however, were not effective (e.g. [32, 38]). Both interventions that included physical training at the workplace were not more effective than the usual care ([30] or workplace specific exercises [25]). Also, interventions including a follow-up (booster sessions or ongoing support if needed) at the workplace (e.g. [25]) were not effective. The interventions that were only effective on short-term RTW included physical therapy and following up at the workplace or advising at the workplace and following up at the workplace.

Discussion

We included 25 interventions that were tested in 21 studies. Ten interventions showed a positive effect on RTW compared to usual care, two interventions showed mixed results, one study showed an effect in favor of the usual care group at 6 months and no effect at 12 months. Twelve interventions were not effective. As for the main aims of the intervention, all effective interventions were aimed at helping the worker prepare to RTW, while one intervention had the additional aim to help the worker find work and two interventions were also aimed at helping the worker remain in work. Two interventions contained all three main aims. The elements analyzed in this study could not explain why some interventions were effective and others were not.

Comparison with Other Studies

The results show that VR interventions are sometimes more effective and often just as effective than usual care in helping people who have been on long-term sick leave (> 90 days) return to work. This review thus shows that effective interventions also exist for people on long-term sick leave. This is in agreement with earlier reviews, which showed that it is possible to influence return to work of people on long-term sick leave [8, 13]. Earlier reviews [7, 8] also suggested that interventions offered to this group should be high intensive interventions. The identified interventions in our study were often high intensive in terms of contact hours and duration, and most were comprehensive by including multiple aims. However, we could not explain differences in effectiveness by differences in intensity, comprehensiveness or the multiple disciplines included. Additionally, the identified characteristics of the studies, such as duration of the intervention or who provided the intervention, could also not explain the differences in effectiveness of the interventions.

The elements that we found, are comparable to the elements that vocational rehabilitation professionals mentioned as crucial for VR interventions [46]. Especially formulating a rehabilitation plan was often part of the effective interventions (5 interventions). But it was also an element in many not effective interventions (9 interventions). Another review [1] concluded that contact with the workplace and including multiple components, are elements of effective interventions. Our results show that these elements are indeed part of the effective interventions, but were often also a part of the not effective interventions. A qualitative review by Reed et al. [47] studied elements that help ensure that workers experience VR interventions as supportive and effective. These elements are also often included in the effective interventions identified in this review. Especially personalized services (n = 4) and collaboration with the employing organization (n = 4) are often included. However, Reed et al. also concluded that skills development, and sustainable and ongoing interventions is what workers find supportive and effective, while these elements were only scarcely part of the effective (and the not-effective) interventions included in this review. The perspective of an effective intervention of a worker might thus be different from the actual effectiveness of an intervention.

With this review we contributed to identifying which elements effective VR interventions entail. We could, however, not conclude which elements make a VR intervention effective (or ineffective) in helping people with a long-term sick leave return to work. This study shows that including multiple phases of helping a worker return to work does not mean the intervention will be effective. It is possible that other elements that were not identified in this review do make an intervention effective. This could be due to the often minimal description of the interventions, which made it difficult to determine the elements. Often studies did not report on personal elements, such as motivation, illness perception and societal participation that do have a large influence on whether or not a person on (long-term) sick leave benefits from interventions and returns to work [48]. Studies also often did not report on the context, such as the organization, in which the VR intervention was tested, while this can be of influence on the effectiveness of the intervention [49]. It is also a possibility that the usual care offered in the studies with the not-effective studies were more elaborate than the usual care offered in the studies with the effective VR interventions. Due to the limited description of the usual care we could not determine if this was the case.

Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of this systematic review is that it is specifically aimed at people with a longer duration of sick leave (> 90 days). It is often thought that VR interventions are not effective or less effective for people with a sick leave duration of more than 90 days. Another strength of this review is that we included populations with any disease type. This is in line with the assumptions of the ICF-model [50] and Gragnano [51], that factors that influence RTW are often the same for people with different diseases. A methodological strength of this study is that we conducted a very broad literature search which limited the chance that we missed important studies, by including a large variety of search terms related to “rehabilitation” and by searching in multiple databases. A limitation of this review is that the included studies often minimally described the intervention and the usual care and only few used a protocol, such as the TIDieR checklist [52], to describe the intervention. Because of this, we were often not able to retrieve all elements in detail and may have missed elements that were relevant, but not described. The included studies were also not always of a high quality, in fact 8 studies had a low quality, often due to a selection bias or weak data collection methods. Another limitation of this study is that only four of the 21 included articles obtained a high (strong) score in the quality assessment. This was mainly due to selection bias, participants that were not blinded for the condition they were allocated to and using self-reported questionnaires to measure return to work.

Implications for Policy, Practice and Research

Based on the results of this review we first can conclude that people on long-term sick leave can return to work and that VR interventions can contribute to this. With this information, social security institutes and other organizations aimed at vocational rehabilitation have an evidence-base to offer VR interventions to people who have been on long-term sick leave or who receive a disability pension. Based on this review we cannot give an overview of the elements of (effective) VR interventions. Future studies are needed to gain (more) knowledge about what elements make VR interventions effective in different settings for people with long-term sick leave. Only after research has shed more light on this, organizations which offer RTW support can focus on individual elements of interventions. This knowledge can be used in tools to provide VR professionals with evidence-based knowledge on effective VR interventions for people on long-term sick leave to ensure workers receive good VR. Our previous studies [48, 53] showed that a decision aid to identify barriers for RTW and to choose appropriate VR interventions can help in reducing practice variation among VR professionals. This review can improve the decision aid with evidence-based knowledge. Future research should investigate how this information can best be implemented in the decision aid. It is recommended that future studies improve the participation rate and use more reliable methods to measure the main outcome to improve the quality of these studies.

Conclusions

This study showed that VR interventions can contribute to the RTW of people with a long-term sick leave. But no specific characteristics or elements were found that could explain why an interventions was more effective on RTW than the offered usual care. There is still much to gain in understanding which characteristics or elements of VR interventions that are aimed at helping people with a long-term sick leavereturn to work are effective or not. More knowledge is needed on which elements constitute effective VR interventions for this group tailored to personal and contextual characteristics to facilitate a better perspective on RTW. In order to improve vocational rehabilitation for people on long-term sick leave or receiving a work disability pension, more high quality studies are needed, in which the study population and intervention content is better described in order to be able to identify what elements make the intervention effective for whom.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy reasons (given the relatively small population of professionals in this field), but are available from the corresponding author (MAH) on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- VR:

-

Vocational rehabilitation

- RTW:

-

Return to work

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- CBT:

-

Cognitive behavioral therapy

- ACT:

-

Accteptance and commitment therapy

References

Mikkelsen MB, Rosholm M. Systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions aimed at enhancing return to work for sick-listed workers with common mental disorders, stress-related disorders, somatoform disorders and personality disorders. Occup Environ Med. 2018;75(9):675–86.

Eklund M, Hansson L, Ahlqvist C. The importance of work as compared to other forms of daily occupations for wellbeing and functioning among persons with long-term mental illness. Commun Ment Health J. 2004;40(5):465–77.

Milner A, LaMontagne A, Aitken Z, Bentley R, Kavanagh AM. Employment status and mental health among persons with and without a disability: evidence from an Australian cohort study. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2014;68(11):1064–71.

Henderson M, Glozier N, Elliott KH. Long term sickness absence. British Med J Publ Gr. 2005. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.330.7495.802.

Publishing O. Sickness, disability and work: breaking the barriers: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2010.

Hoefsmit N, Houkes I, Nijhuis FJ. Intervention characteristics that facilitate return to work after sickness absence: a systematic literature review. J Occup Rehabil. 2012;22(4):462–77.

Venning A, Oswald TK, Stevenson J, Tepper N, Azadi L, Lawn S, Redpath P. Determining what constitutes an effective psychosocial ‘return to work’ intervention: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–25.

Aasdahl L, Fimland MS. Is there really a “golden hour” for work disability interventions? a narrative review. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(4):586–93.

Waddell G. Volvo award in clinical sciences. A new clinical model for the treatment of low-back pain. Spine. 1987;12(7):632–44.

Louwerse I, Huysmans MA, van Rijssen HJ, van der Beek AJ, Anema JR. Characteristics of individuals receiving disability benefits in the Netherlands and predictors of leaving the disability benefit scheme: a retrospective cohort study with five-year follow-up. BMC Publ Health. 2018;18:1–12.

Brongers KA, Hoekstra T, Roelofs PD, Brouwer S. Prevalence, types, and combinations of multiple problems among recipients of work disability benefits. Disabil Rehabil. 2022;44(16):4303–10.

Waddell G, Aylward M. The scientific and conceptual basis of incapacity benefits: Stationery Office; 2005.

Levack WMM, Fadyl JK. Vocational interventions to help adults with long-term health conditions or disabilities gain and maintain paid work: an overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12):e049522.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:105906.

Otten R, de Vries R, Schoonmade L. Amsterdam efficient deduplication (AED) method (version 1). Zenodo; 2019.

Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, Holland L, Bekhuis T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in endnote. J Med Libr Assoc: JMLA. 2016;104(3):240.

Finnes A, Enebrink P, Ghaderi A, Dahl J, Nager A, Öst L-G. Psychological treatments for return to work in individuals on sickness absence due to common mental disorders or musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2019;92(3):273–93.

Vogel N, Schandelmaier S, Zumbrunn T, Ebrahim S, de Boer WE, Busse JW, Kunz R. Return‐to‐work coordination programmes for improving return to work in workers on sick leave. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017(3).

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5:1–10.

Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. Prod ESRC Methods Progr Vers. 2006;1(1):b92.

Liu S, Huang JL, Wang M. Effectiveness of job search interventions: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2014;140(4):1009.

Ciliska D, Miccouci S, Dobbins M. Effective public health practice project. quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. Hamilton, On: Effective Public Health Practice Project. 1998.

Thomas B, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid-Based Nurs. 2004;1(3):176–84.

Fleten N, Johnsen R. Reducing sick leave by minimal postal intervention: a randomised, controlled intervention study. Occup Environ Med. 2006;63(10):676–82.

Marhold C, Linton SJ, Melin L. A cognitive–behavioral return-to-work program: effects on pain patients with a history of long-term versus short-term sick leave. Pain. 2001;91(1–2):155–63.

Berglund E, Anderzen I, Andersen A, Carlsson L, Gustavsson C, Wallman T, Lytsy P. Multidisciplinary intervention and acceptance and commitment therapy for return-to-work and increased employability among patients with mental illness and/or chronic pain: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112424.

Cheng AS, Hung LK. Randomized controlled trial of workplace-based rehabilitation for work-related rotator cuff disorder. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17(3):487–503.

Corey DT, Koepfler LE, Etlin D, Day H. A limited functional restoration program for injured workers: a randomized trial. J Occup Rehabil. 1996;6(4):239–49.

Hees HL, de Vries G, Koeter MW, Schene AH. Adjuvant occupational therapy improves long-term depression recovery and return-to-work in good health in sick-listed employees with major depression: results of a randomised controlled trial. Occup Environ Med. 2013;70(4):252–60.

Heinrich J, Anema JR, de Vroome EM, Blatter BM. Effectiveness of physical training for self-employed persons with musculoskeletal disorders: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:200.

Huibers MJ, Beurskens AJ, Van Schayck CP, Bazelmans E, Metsemakers JF, Knottnerus JA, Bleijenberg G. Efficacy of cognitive–behavioural therapy by general practitioners for unexplained fatigue among employees: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184(3):240–6.

Nilsson I, von Buxhoeveden L. An attempt to work rehabilitation after long sick-leave. Work. 1996;7(3):183–9.

van Egmond MP, Duijts SF, Jonker MA, van der Beek AJ, Anema JR. Effectiveness of a tailored return to work program for cancer survivors with job loss: results of a randomized controlled trial. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(9–10):1210–9.

Blonk RWB, Brenninkmeijer V, Lagerveld SE, Houtman ILD. Return to work: a comparison of two cognitive behavioural interventions in cases of work-related psychological complaints among the self-employed. Work Stress. 2006;20(2):129–44.

Della-Posta C, Drummond PD. Cognitive behavioural therapy increases re-employment of job seeking worker’s compensation clients. J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16(2):217–24.

Lytsy P, Carlsson L, Anderzen I. Effectiveness of two vocational rehabilitation programmes in women with long-term sick leave due to pain syndrome or mental illness: 1-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med. 2017;49(2):170–7.

Magnussen L, Strand LI, Skouen JS, Eriksen HR. Motivating disability pensioners with back pain to return to work–a randomized controlled trial. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39(1):81–7.

Myhre K, Marchand GH, Leivseth G, Keller A, Bautz-Holter E, Sandvik L, et al. The effect of work-focused rehabilitation among patients with neck and back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine(Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39(24):1999–2006.

Park J, Esmail S, Rayani F, Norris CM, Gross DP. Motivational interviewing for workers with disabling musculoskeletal disorders: results of a cluster randomized control trial. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28(2):252–64.

van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Hoedeman R, de Jong FJ, Meeuwissen JA, Drewes HW, van der Laan NC, Adèr HJ. Faster return to work after psychiatric consultation for sicklisted employees with common mental disorders compared to care as usual. A randomized clinical trial. Neuropsychiatr dis treat. 2010;6:375.

Lambeek LC, van Mechelen W, Knol DL, Loisel P, Anema JR. Randomised controlled trial of integrated care to reduce disability from chronic low back pain in working and private life. BMJ. 2010;340:c1035.

Li-Tsang CW, Li EJ, Lam CS, Hui KY, Chan CC. The effect of a job placement and support program for workers with musculoskeletal injuries: a randomized control trial (RCT) study. J Occup Rehabil. 2008;18(3):299–306.

Hellström L, Bech P, Nordentoft M, Lindschou J, Eplov LF. The effect of IPS-modified, an early intervention for people with mood and anxiety disorders: study protocol for a randomised clinical superiority trial. Trials. 2013;14(1):1–10.

Hellstrom L, Bech P, Hjorthoj C, Nordentoft M, Lindschou J, Eplov LF. Effect on return to work or education of Individual Placement and Support modified for people with mood and anxiety disorders: results of a randomised clinical trial. Occup Environ Med. 2017;74(10):717–25.

Drake RE, Frey W, Bond GR, Goldman HH, Salkever D, Miller A, et al. Assisting Social Security Disability Insurance beneficiaries with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression in returning to work. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(12):1433–41.

Dekkers-Sánchez PM, Wind H, Sluiter JK, Frings-Dresen MH. What promotes sustained return to work of employees on long-term sick leave? perspectives of vocational rehabilitation professionals. Scand J Work, Environ Health. 2011. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3173.

Reed K, Fadyl JK, Anstiss D, Levack WM. Experiences of vocational rehabilitation and support services for people living with a long term condition: qualitative systematic review. Disabil Rehabilit. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2021.2022779.

de Geus CJ, Huysmans MA, van Rijssen HJ, Anema JR. Return to work factors and vocational rehabilitation interventions for long-term, partially disabled workers: a modified Delphi study among vocational rehabilitation professionals. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):875.

Durand M-J, Sylvain C, Fassier J-B, Tremblay D, Shaw WS, Anema JR, et al. Musculoskeletal Disorders - Realist Review of Theories Underlying Rehabilitation Programs that Include a Workplace Intervention. In French. Rapport R-942. Montréal: IRSST.

Üstün TB, Chatterji S, Bickenbach J, Kostanjsek N, Schneider M. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: a new tool for understanding disability and health. Disabil Rehabil. 2003;25(11–12):565–71.

Gragnano A, Negrini A, Miglioretti M, Corbière M. Common psychosocial factors predicting return to work after common mental disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and cancers: a review of reviews supporting a cross-disease approach. J Occup Rehabil. 2018;28:215–31.

Hoffmann TC, Glasziou PP, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D, et al. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1687.

de Geus CJ, Huysmans MA, van Rijssen HJ, Juurlink TT, de Maaker-Berkhof M, Anema JR. A decision aid to support vocational rehabilitation professionals offering tailored care to benefit recipients with a long-term work disability: a feasibility study. J Occup Rehabil. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-023-10105-7.

Funding

This study was funded by the Dutch Social Security Institute. The funding organization had no role in analysis and interpretation of the data, in writing the paper and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the writing and revisions of the manuscript. CdG was the main contributor to the data collection, analyses, interpretation of the data and first drafts of the manuscript. LS contributed to the search strategy and writing the methods section. MAH, MM, HJVR and JRA were major contributors to the design of the study, selecting studies, interpretation of the data and revisions of the manuscript. All authors have seen, read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

HJvR was employed at the Dutch Social Security Institute while this study was carried out. JRA is advisor of Amsterdam University Medical Center’s spin-off companies Evalua Nederland BV and IKherstel BV. JRA holds a chair in Insurance Medicine sponsored by the Dutch Social Security Institute. CdG, MMB and MAH are partly paid by the Dutch SSI.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Amsterdam UMC, VU University Medical Centre Amsterdam. The committee declared that no comprehensive ethical approval was needed for this study. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

de Geus, C.J.C., Huysmans, M.A., van Rijssen, H.J. et al. Elements of Return-to-Work Interventions for Workers on Long-Term Sick Leave: A Systematic Literature Review. J Occup Rehabil (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-024-10203-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-024-10203-0