Abstract

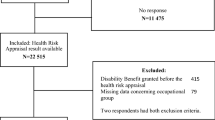

Purpose Unintentional injuries occur frequently and many of the accident survivors suffer from temporary or permanent disabilities. Although most accident victims recover quickly, a significant fraction of them shows a complicated recovery process and accounts for the majority of disability costs. Thus, early identification of vulnerable persons may be beneficial for compensation schemes, government bodies, as well as for the worker themselves. Here we present the Work and Health Questionnaire (WHQ), a screening tool that is already implemented in the case management process of the Swiss Accident Insurance Fund (Suva). Moreover, we demonstrate its prognostic value for identifying workers at risk of a complicated recovery process. Methods A total of 1963 injured workers answered the WHQ within the first 3 months after their accident. All of them had minor to moderate accidental injuries; severely injured workers were excluded from the analyses. The anonymized individual-level data were extracted from insurance databases. We examined construct validity by factorial analyses, and prognostic validity by hierarchical multiple regression analyses on days of work disability. Further, we evaluated well-being and job satisfaction 18 months post-injury in a subsample of 192 injured workers (9.8 %) Results Factor analyses supported five underlying factors (Job Design, Work Support, Job Strain, Somatic Condition/Pain, and Anxiety/Worries). These subscales were moderately correlated, thus indicating that different subscales measured different aspects of work and health-related risk factors of injured workers. Item analysis and reliability analysis showed accurate psychometric properties. Each subscale was predictive at least for one of the evaluated outcomes 18 months post-injury. Conclusion The WHQ shows good psychometric qualities with high clinical utility to identify injured persons with multiple psychosocial risk factors. Thus, the questionnaire appears to be suitable for exploring different rehabilitation needs among minor to moderate injured workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organization. Injuries and violence: the facts 2014. Geneva: WHO; 2014.

Centers of Disease Control and Prevention Appendix II. Definitions and methods [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2016 May 21]. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/injury/Definitions_of_injury_terms.pdf.

Adams PF, Martinez ME, Vickerie JL, Kirzinger WK. Summary health statistics for the U.S. population: National Health Interview Survey, 2012. Vital Health Stat. 2013;10(259):1–95.

Hashemi L, Webster BS, Clancy EA, Courtney TK. Length of disability and cost of work-related musculoskeletal disorders of the upper extremity. J Occup Environ Med. 1998;40(3):261–9. doi:10.1097/00043764-199803000-00008.

Siegenthaler F. Ich glaube, dass ich mindestens drei Monate nicht normal arbeiten gehen kann [I think that I am not able to work normally within 3 months]. Suva Med. 2010;22–39.

Harper S. Economic and social implications of aging societies. Science. 2014;346(6209):587–91. doi:10.1126/science.1254405.

Waddell G, Burton AK. Is work good for your health and well-being?. London: Stationery Office; 2006.

Saunders SL, Nedelec B. What work means to people with work disability: a scoping review. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24(1):100–10. doi:10.1007/s10926-013-9436-y.

Laisné F, Lecomte C, Corbière M. Biopsychosocial determinants of work outcomes of workers with occupational injuries receiving compensation: a prospective study. Work. 2013;44(2):117–32. doi:10.3233/WOR-2012-1378.

Lange C, Burgmer M, Braunheim M, Heuft G. Prospective analysis of factors associated with work reentry in patients with accident-related injuries. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17(1):1–10. doi:10.1007/s10926-006-9039-y.

Lin KH, Guo NW, Shiao SC, Liao SC, Hu PY, Hsu JH, et al. The impact of psychological symptoms on return to work in workers after occupational injury. J Occup Rehabil. 2013;23(1):55–62. doi:10.1007/s10926-012-9381-1.

Mason S, Wardrope J, Turpin G, Rowlands A. Outcomes after injury: a comparison of workplace and non workplace injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2002;53(1):98–103. doi:10.1097/00005373-200207000-00019.

Schultz IZ, Crook J, Berkowitz J, Milner R, Meloche GR. Predicting return to work after low back injury using the psychosocial risk for occupational disability instrument: a validation study. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(3):365–76. doi:10.1007/s10926-005-5943-92005.

Schultz IZ, Stowell AW, Feuerstein M, Gatchel RJ. Models of return to work for musculoskeletal disorders. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17(2):327–52. doi:10.1007/s10926-007-9071-6.

Stover B, Wickizer TM, Zimmerman F, Fulton-Kehoe D, Franklin G. Prognostic factors of long-term disability in a workers’ compensation system. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(1):31–40. doi:10.1097/01.jom.0000250491.37986.b6.

Hepp U, Moergeli H, Buchi S, Bruchhaus-Steinert H, Sensky T, Schnyder U. The long-term prediction of return to work following serious accidental injuries: a follow up study. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11(1):53. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-11-53.

Meerding WJ, Looman CW, Essink-Bot ML, Toet H, Mulder S, van Beeck EF. Distribution and determinants of health and work status in a comprehensive population of injury patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2004;56(1):150–61. doi:10.1097/01.TA.0000062969.65847.8B.

Tecic T, Lefering R, Althaus A, Rangger C, Neugebauer E. Pain and quality of life 1 year after admission to the emergency department: Factors associated with pain. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2013;39(4):353–61. doi:10.1007/s00068-013-0271-9.

Fadyl J, McPherson K. Return to work after injury: a review of evidence regarding expectations and injury perceptions, and their influence on outcome. J Occup Rehabil. 2008;18(4):362–74. doi:10.1007/s10926-008-9153-0.

Franche RL, Krause N. Readiness for return to work following injury or illness: conceptualizing the interpersonal impact of health care, workplace, and insurance factors. J Occup Rehabil. 2002;12(4):233–56. doi:10.1023/A:1020270407044.

Hepp U, Schnyder U, Hepp-Beg S, Friedrich-Perez J, Stulz N, Moergeli H. Return to work following unintentional injury: a prospective follow-up study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(12):e003635. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003635.

Pjanic I, Messerli-Bürgy N, Bachmann MS, Siegenthaler F, Hoffmann-Richter U, Znoj HJ. Predictors of depressed mood 12 months after injury. Contribution of self-efficacy and social support. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(15):1258–63. doi:10.3109/09638288.2013.837971.

Seland K, Cherry N, Beach J. A study of factors influencing return to work after wrist or ankle fractures. Am J Ind Med. 2006;49(3):197–203. doi:10.1002/ajim.20258.

Krause N, Dasinger LK, Deegan LJ, Rudolph L, Brand RJ. Psychosocial job factors and return-to-work after compensated low back injury: a disability phase-specific analysis. Am J Ind Med. 2001;40(4):374–92. doi:10.1002/ajim.1112.

Feuerstein M. A multidisciplinary approach to the prevention, evaluation, and management of work disability. J Occup Rehabil. 1991;1(1):5–12. doi:10.1007/BF01073276.

Brouwer S, Franche RL, Hogg-Johnson S, Lee H, Krause N, Shaw WS. Return-to-work self-efficacy: development and validation of a scale in claimants with musculoskeletal disorders. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21(2):244–58. doi:10.1007/s10926-010-9262-4.

Siegenthaler F. Psychische Gesundheit und Rückkehr zur Arbeit von Verletzten nach leichten und moderaten Unfallereignissen—Prädiktoren für die Früherkennung komplizierter Heilungsverläufe [Mental health and return to work of minor to moderate injured persons—predictors for early identification of complicated recovery trajectories] [unpublished doctoral thesis]. [Bern (CH)]: University of Berne; 2011 [cited 2016 May 21]. http://www.zb.unibe.ch/download/eldiss/11siegenthaler_f.pdf.

Znoj HJ. ISRCTN05534684, Improving the diagnostic procedure for injured patients—Optimization for the questionnaire “Fragebogen Arbeit und Befinden” (OptiFAB) [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2016 May 21]. Available from ISRCTN: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/ISRCTN05534684.

Grob A, Lüthi R, Kaiser FG, Flammer A, Mackinnon A, Wearing AJ. Berner Fragebogen zum Wohlbefinden Jugendlicher (BFW) [The Bern Subjective Well-Being Questionnaire on Adolescents (BFW)]. Diagnostica. 1991;37(1):66–75.

Bruggemann A. Zur empirischen Untersuchung verschiedener Formen von Arbeitszufriedenheit [Empirical investigation of different different kinds of job satisfaction]. Z Arbeitswiss. 1976;30:71–4.

Fox J, Weisberg S. An R companion to applied regression. Washington: Sage; 2010.

Rosseel Y. Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw. 2012;48(2):1–36. doi:10.18637/jss.v048.i02.

Revelle W. Psych: procedures for personality and psychological research [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2016 May 21]. Available from Northwestern University, Illinois. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psychVersion=1.5.4.

Su YS, Yajima M, Gelman AE, Hill J. Multiple imputation with diagnostics (mi) in R: Opening windows into the black box. J Stat Softw. 2011;45(2):1–31. doi:10.18637/jss.v045.i02.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Open source: R Foundation for Statistical Computing [Internet]. Vienna; 2015 [cited 2016 May 21]. http://www.R-project.org/.

Flora DB, Curran PJ. An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychol Methods. 2004;9(4):466–91. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.466.

Schermelleh-Engel K, Moosbrugger H, Müller H. Evaluating the fit of structural equation models: Tests of significance and descriptive goodness-of-fit measures. Methods Psychol Res Online. 2003;8(2):23–74.

Dunn TJ, Baguley T, Brunsden V. From alpha to omega: a practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. Br J Psychol. 2014;105(3):399–412. doi:10.1111/bjop.12046.

Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Market Res. 1981;18(1):39–50. doi:10.2307/3151312.

Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An introduction to the bootstrap. New York: Chapman Hall; 1994.

Little RJA. A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. J Am Statist Assoc. 1988;83(404):1198–202. doi:10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722.

Horn JL. A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1965;30:179–85.

Revelle W, Rocklin T. Very simple structure: An alternative procedure for estimating the optimal number of interpretable factors. Multivar Behav Res. 1979;14(4):403–14. doi:10.1207/s15327906mbr1404_2.

O’Connor BP. SPSS and SAS programs for determining the number of components using parallel analysis and Velicer’s MAP test. Behav Res Methods Instr. 2000;32(3):396–402. doi:10.3758/BF03200807.

Cohen J. Statistical power for the social sciences. Hillsdale: Laurence Erlbaum; 1988.

Elfering A, Semmer NK, Schade V, Grund S, Boos N. Supportive colleague, unsupportive supervisor: the role of provider-specific constellations of social support at work in the development of low back pain. J Occup Health Psychol. 2002;7(2):130–40. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.7.2.130.

Uchino BN, Cacioppo JT, Kiecolt-Glaser JK. The relationship between social support and physiological processes: a review with emphasis on underlying mechanisms and implications for health. Psychol Bull. 1996;119(3):488–531. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.488.

Frank JW, Kerr MS, Brooker AS, DeMaio SE, Maetzel A, Shannon HS, et al. Disability resulting from occupational low back pain. Part I: what do we know about primary prevention? A review of the scientific evidence on prevention before disability begins. Spine. 1996;21(24):2908–17. doi:10.1097/00007632-199612150-00024.

Prümper J, Hartmannsgruber K, Frese M. KFZA. Kurz-Fragebogen zur Arbeitsanalyse [KFZA. A short questionnaire for job analysis]. Z Arb Organ. 1995;39(3):125–31.

Baillod J, Semmer N. Fluktuation und Berufsverläufe bei Computerfachleuten [Turnover and career paths of computer specialists]. Z Arb Organ. 1994;8(4):152–63.

Rimann M, Udris I. Fragebogen Salutogenetische Subjektive Arbeitsanalyse (SALSA) [Subjective analysis of work—The questionaire SALSA]. In: Dunckel H, editor. Handbuch psychologischer Arbeitsanalyseverfahren [Handbook of psychological methods of work analysis]. Zürich: vdf Hochschulverlag ETH; 1999. p. 239–63.

Stieglitz RD, Nyberg E, Albert M, Frommberger U, Berger M. Entwicklung eines Screeninginstrumentes zur Identifizierung von Risikopatienten für die Entwicklung einer Posttraumatischen Belastungsstörung (PTBS) nach einem Verkehrsunfall [Development of a screening instrument to identify patients at risk of developing a posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after an accident]. Z Kl Psych Psychoth. 2002;31(1):22–30. doi:10.1026/0084-5345.31.1.22.

Gerdes N, Jäckel WH. Der IRES-Fragebogen für Klinik und Forschung [IRES-24 patient questionnaire]. Rehabilitation. 1995;34(2):XIII–XXIII.

Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D, Main CJ. A fear-avoidance beliefs questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain. 1993;52(2):157–68. doi:10.1016/0304-3959(93)90127-B.

Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiat Scand. 1983;67(6):361–70. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x.

Mittag O, Raspe H. Eine kurze Skala zur Messung der subjektiven Prognose der Erwerbstätigkeit: Ergebnisse einer Untersuchung an 4279 Mitgliedern der gesetzlichen Arbeiterrentenversicherung zu Reliabilität (Guttman-Skalierung) und Validität der Skala [A Brief Scale for Measuring Subjective Prognosis of Gainful Employment: Findings of a Study of 4279 Statutory Pension Insurees Concerning Reliability (Guttman Scaling) and Validity of the Scale]. Die Rehabil. 2003;42(3):169–74. doi:10.1055/s-2003-40095.

Derogatis LR, Lipman RS. SCL-90. Administration, scoring and procedures manual-I for the R (revised) version and other instruments of the psychopathology rating scales series. Chicago: Johns Hopkins University; 1977.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Livia Kohli, Bettina Gerber, and Romy Schnyder for their help with the recruitment and data management, and Mey Boukenna and Madeleine Hänggli for their critical proofreading. The study was supported by the Swiss Accident Insurance Fund (Suva). No commercial sponsorship was involved in the design and conduction of the study.

Funding

This study was supported by the Swiss Accident Insurance Fund (Suva). No commercial sponsorship was involved in the design and conduction of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Sandra Abegglen, Ulrike Hoffmann-Richter, Volker Schade, Hans Jörg Znoj declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

‘All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.’ Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Commission University of Berne under reference No. 2011-04-172.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix: WHQ Items

Appendix: WHQ Items

No. | English version | German version | Rating scale | Origin scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

WHQ_Work | ||||

W1 | Can you independently plan and organize your work? | Können Sie Ihre Arbeit selbständig planen und einteilen? | Likert scale (1–5) | KFZA |

W2 | Can you learn something new in your job? | Können Sie bei Ihrer Arbeit Neues dazu lernen? | Likert scale (1–5) | KFZA |

W3 | In my job, I can see from the result whether my work was good or not | Bei meiner Arbeit sehe ich selber am Ergebnis, ob meine Arbeit gut war oder nicht | Likert scale (1–5) | KFZA |

W4 | In my work I can carry out a working task, from A to Z | Bei meiner Arbeit kann ich eine Sache oder ein Produkt von A bis Z herstellen resp. Ausführen | Likert scale (1–5) | SALSA |

W5 | My job is not ideal, but it could be even worse | Meine Arbeit ist zwar nicht gerade ideal, aber schliesslich könnte Sie noch schlimmer sein | Likert scale (1–7) | AZK |

W6 | I have too much work | Ich habe zu viel Arbeit | Likert scale (1–5) | KFZA |

W7 | Needed information or working tools (e.g., computer) are often not available | Oft stehen mir die benötigten Informationen, Arbeitsmittel (z.B. Computer) nicht zur Verfügung | Likert scale (1–5) | KFZA |

W8 | I am often interrupted in my work (e.g., telephone calls) | Ich werde bei meiner Arbeit immer wieder unterbrochen (z.B. durch Telefon) | Likert scale (1–5) | KFZA |

W9 | The working conditions at my workplace are unfavorable. There are disturbances, such as noise, temperature, dust | An meinem Arbeitsplatz gibt es ungünstige Umgebungsbeding ungen wie Lärm, Klima, Staub | Likert scale (1–5) | KFZA |

W10 | In case of any difficulties, I can rely on my colleagues | Ich kann mich auf meine Arbeitskollegen/-kolleginnen verlassen, wenn es bei der Arbeit schwierig wird | Likert scale (1–5) | KFZA |

W11 | In case of any difficulties, I can rely on my boss/supervisor | Ich kann mich auf meine/n direkte/n Vorgesetzte/n verlassen, wenn es bei der Arbeit schwierig wird | Likert scale (1–5) | KFZA |

W12 | I always get feedback about the quality of my work from my colleagues or my supervisor | Ich bekomme von Vorgesetzten sowie Arbeitskollegen/-innen immer Rückmeldung über die Qualität meiner Arbeit | Likert scale (1–5) | KFZA |

WHQ_Health | ||||

H1 | Did you feel helpless during or after the accident? | Fühlten Sie sich während des Unfalls oder kurz danach hilflos? | 0, 1 | PTBS |

H2 | Do pictures about it (the accident) pop up into your mind? | Haben Sie plötzlich auftretende Bilder (vom Unfall) im Kopf? | 0, 1 | PTBS |

H3 | How would you describe your actual general health condition? | Wie würden Sie ihren gegenwärtigen Gesundheits-zustand beschreiben? | VAS (0–100) | IRES |

H4 | How often did you suffer from pain recently? | Wie häufig haben Sie in der letzten Zeit unter Schmerzen gelitten? | VAS (0–100) | IRES |

H5 | How much do you feel that this pain affects your daily life? | Wie stark fühlen Sie sich durch diese Schmerzen im täglichen Leben beeinträchtigt? | VAS (0–100) | IRES |

H6 | I think that I am not able to work normally within 3 months | Ich glaube, dass ich mindestens 3 Monate nicht normal arbeiten gehen kann | Likert scale (0–6) | FABQ |

H7 | (In the past week) I felt as if I am slowed down | (In der letzten Woche) fühlte ich mich in meinen Aktivitäten gebremst | Likert scale (0–3) | HADS |

H8 | (In the past week), worrying thoughts go through my mind | (In der letzten Woche) gingen mir beunruhigende Gedanken durch den Kopf | Likert scale (0–3) | HADS |

H9 | Have you recently been worrying about earning less in the future because of the accident? | Machen Sie sich in der letzten Zeit Sorgen darüber, dass Sie in Zukunft wegen des Unfalls weniger verdienen? | Likert scale (0–3) | SPE |

H10 | How much were you bothered or distressed over the past 7 days by feeling lonely? | Wie sehr litten Sie in den letzten 7 Tagen unter Einsamkeitsgefühlen? | Likert scale (0–4) | SCL-90 |

H11 | How much were you bothered or distressed over the past 7 days by feeling fearful? | Wie sehr litten Sie in den letzten 7 Tagen unter Furchtsamkeit? | Likert scale (0–4) | SCL-90 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abegglen, S., Hoffmann-Richter, U., Schade, V. et al. Work and Health Questionnaire (WHQ): A Screening Tool for Identifying Injured Workers at Risk for a Complicated Rehabilitation. J Occup Rehabil 27, 268–283 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-016-9654-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-016-9654-1