Abstract

Divergence in forelimb morphology is often associated with functional habits exhibited within the Xenarthra, ranging from terrestrial-digging in armadillos to arboreal-suspension in sloths. We hypothesized that quantitative differences in hind limb form also will be predictive of the diverse lifestyles observed in this small clade. A total of 26 morphofunctional indices were calculated from 42 raw measurements of bone length/width/depth in a sample of N = 76 skeletal specimens (18 species). Index data for each species were categorized by substrate preference and use and then evaluated using a combination of stepwise Discriminant Function Analysis (DFA) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to determine significant osteological correlates (traits) among extant taxa. Additionally, character states of the morphometric data were inferred using a recent hypothesis of xenarthran phylogeny. DFA determined 14 distinct morphofunctional indices relating to femur robustness, hip/ankle/limb mechanical advantage, and foot and claw length as the most discriminating features. PCA clearly separated armadillos from sloths in morphospace based on overall robustness versus gracility, as well as proximal versus distal lengths of skeletal elements (including the claws), whereas these characteristics were intermediate in the hind limbs of anteaters and selected armadillos having either a larger greater trochanter or modified foot/claw proportions. Two-toed and three-toed sloths showed further separation from each other in morphospace primarily driven by proportions of their tibia and hind feet despite evidence of convergence for numerous functional traits. Moreover, the majority of the traits measured had significant phylogenetic signal and several of these indicated clear patterns of convergent and divergent evolution in xenarthrans by evaluation of their tip states. Our assessments expand functional interpretations of xenarthran limb form and identify potentially conserved and secondarily modified traits related to fossoriality across taxa, including in three-toed sloths, demonstrate possible morphological trade-offs between digging and climbing habits, and suggest derived traits adapted for arboreal lifestyle and suspensory function.

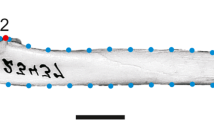

taken from the a femur, b proximal femur, c tibio-fibula, d tibia, e hind foot, f calcaneus, and g claw. The measurements shown here were used for index calculations: FL, femur length; FMW, femur mid-shaft width; FMD, femur mid-shaft depth; FHL, femur head length; FHW, femur head width; FHD, femur head depth; PFL, proximal femur length; GTL, greater trochanter length; GTW, greater trochanter width; FCW, femur condylar width; FCL-M, femur condylar length-medial; FCD-M, femur condylar depth-medial; FCL-L, femur condylar length-lateral; FBL, fibula length; TL, tibia length; TMW, tibia mid-shaft width; TMD, tibia mid-shaft depth; TPEW, tibia proximal end width; TDED, tibia distal end depth; TDEW, tibia distal end width; MML, medial malleolus length; MMW, medial malleolus width; MT3L, third metatarsal length; MT3W, third metatarsal width; PP3L, proximal phalanx length of digit III; PP3W, proximal phalanx width of digit III; CL, calcaneus length; PC3L, pes claw length of digit III. Greater trochanter depth and femur condylar depth (lateral) are not illustrated. Selected measurements adapted from Salton and Sargis (2009)

Adapted from Gibb et al. (2016)

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Data generated for this study are included in this published article in adherence with disclosure policy of the journal. The authors also share condensed osteological and index data as a supplement. Additional raw data is available upon reasonable request.

References

Abba AM, Superina M (2016) Dasypus hybridus (Cingulata: Dasypodidae). Mammal Species 48:10-20

Attias N, Miranda FR, Sena LMM, Tomas WM, Mourão GM (2016) Yes, they can! Three-banded armadillos Tolypeutes sp. (Cingulata: Dasypodidae) dig their own burrows. Zoologia (Curitiba) 33:1-8

Beebe W (1926) The three-toed sloth. Bradypus cuculliger cuculliger Wagler. Zoologica 7:1-67

Biewener AA (2005) Biomechanical consequences of scaling. J Exp Biol 208:1665-1676

Blomberg SP, Garland T Jr, Ives AR (2003) Testing for phylogenetic signal in comparative data: behavioral traits are more labile. Evolution 57:717-745

Borghi CE, Campos CM, Giannoni SM, Campos VE, Sillero-Zubiri C (2011) Updated distribution of the pink fairy armadillo Chlamyphorus truncatus (Xenarthra, Dasypodidae), the world's smallest armadillo. Edentata 12:14-19

Britton SW (1941) Form and function in the sloth. Q Rev Biol 16:13-34

Carillo E, Fuller TK, Saenz JC (2009) Jaguar (Panthera onca) hunting activity: effects of prey distribution and availability. J Trop Ecol 25:563-567

Carter TS, Superina M, Leslie DM Jr (2016) Priodontes maximus (Cingulata: Chlamyphoridae). Mammal Species 48:21-34

Clerici GP, Rosa PS, Costa FR (2018) Description of digging behavior in armadillos Dasypus novemcinctus (Xenarthra: Dasypodidae). Mastozool Neotrop 25:283-291.

Copploe JV II, Blob RW, Parrish JHA, Butcher MT (2015) In vivo strains in the femur of the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus). J Morphol 276:889-899

Costa FR, Clerici GP, Lobo-Ribiero L, Rosa PS, Rocha-Barbosa O (2019) Analysis of the spatio-temporal parameters of gaits in Dasypus novemcinctus (Xenarthra: Dasypodidae). Acta Zool 100:61-68

Costa FR, Clerici GP, Rosa PS, Lobo-Ribiero L, Rocha-Barbosa O (2017) Kinematic description of the vertical climbing of Dasypus novemcinctus (Xenarthra, Dasypodidae): the first report of this ability in armadillos. Mastozool Neotrop 24:451-456

Delsuc F, Kuch M, Gibb GC, Karpinski E, Hackenberger D, Szpak P, Billet G (2019) Ancient mitogenomes reveal the evolutionary history and biogeography of sloths. Curr Biol 29:2031-2042

Delsuc F, Scally M, Madsen O, Stanhope MJ, de Jong WW, Catzeflis FM, Springer MS, Douzery EJP (2002) Molecular phylogeny of living xenarthrans and the impact of character and taxon sampling on the placental tree rooting. Mol Biol Evol 19:1656-1671

Delsuc F, Stanhope MJ, Douzery EJP (2003) Molecular systematics of armadillos (Xenarthra, Dasypodidae): contribution of maximum likelihood and Bayesian analyses of mitochondrial and nuclear genes. Mol Phylogenet Evol 28:261-275

Delsuc F, Vizcaíno SF, Douzery EJP (2004) Influence of Tertiary paleoenvironmental changes on the diversification of South American mammals: a relaxed molecular clock study within xenarthrans. BMC Evol Biol 4:11

Desbiez ALJ, Massocato GF, Kluyber D, Santos RCF (2018) Unraveling the cryptic life of the southern naked-tailed armadillo, Cabassous unicinctus squamicaudis (Lund, 1845), in a Neotropical wetland: home range, activity pattern, burrow use and reproductive behaviour. Mammal Biol 91:95-103

Echeverría AI, Becerra F, Vassallo AI (2014) Postnatal ontogeny of limb proportions and functional indices in the subterranean rodent Ctenomys talarum (Rodentia: Ctenomyidae). J Morphol 275:902-913

Engelmann GF (1985) The phylogeny of the Xenarthra. In: Montgomery GG (ed) The Evolution and Ecology of Armadillos, Sloths, and Vermilinguas. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington and London, pp 51-64

Enger PS, Bullock TH (1965) Physiological basis of slothfulness in the sloth. Hvalradets Skriftet 48:143-160

Fariña RA, Vizcaíno SF, Bargo MS (1998) Body mass estimations in Lujanian (late Pleistocene-early Holocene of South America) mammal megafauna. Mastozool Neotrop 5:87-108

Felsenstein J (1985) Phylogenies and the comparative method. Am Nat 125:1-15

Gaudin TJ, Croft DA (2015) Paleogene Xenarthra and the evolution of South American mammals. J Mammal 96:622-634

Gaudin TJ, McDonald HG (2008) Morphology-based investigations of the phylogenetic relationships among extant and fossil xenarthrans. In: SF Vizcaíno, WJ Loughry (eds) The Biology of the Xenarthra. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, pp 24-36

Gibb GC, Condamine FL, Kuch M, Enk J, Moraes-Barros N, Superina M, Poinar HN, Delsuc F (2016) Shotgun mitogenomics provides a reference phylogenetic framework and timescale for living xenarthrans. Mol Biol Evol 33:621-642

Goffart M (1971) Function and Form in the Sloth. Pergamon Press, Oxford, 225 pp

Gorvet MA, Wakeling JM, Morgan DM, Hidalgo Segura D, Avey-Arroyo JA, Butcher MT (2020) Keep calm and hang on: EMG activation in the forelimb musculature of three-toed sloths. J Exp Biol 223. https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.21837

Granatosky MC, Karantanis NE, Rychlik L, Youlatos D (2018) A suspensory way of life: integrating locomotion, postures, limb movements, and forces in two-toed sloths Choloepus didactylus (Megalonychidae, Folivora, Pilosa). J Exp Zool 329:570-588

Greegor DH Jr (1985) Ecology of the little hairy armadillo Chaetophractus vellerosus. In: Montgomery GG (ed) The Evolution and Ecology of Armadillos, Sloths, and Vermilinguas. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington and London, pp 397-405

Hamlett GWD (1939) Identity of Dasypus septemcinctus Linnaeus with notes on some related species. J Mammal 20:328-336

Hanna JB, Granatosky MC, Rana P, Schmitt D (2017) The evolution of vertical climbing in primates: evidence from reaction forces. J Exp Biol 220:3039-3052

Hayssen V (2011) Tamandua tetradactyla (Pilosa: Myrmecophagidae). Mammal Species 43:64-74

Hayssen V, Miranda F, Pasch B (2012) Cyclopes didactylus (Pilosa: Cyclopedidae). Mammal Species 44:51-58

Hildebrand M (1985) Digging of quadrupeds. In: Hildebrand M, Bramble KF, Wake DB (eds) Functional Vertebrate Morphology. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, pp 89-109

Kilbourne BM, Hutchinson JR (2019) Morphological diversification of biomechanical traits: mustelid locomotor specialization and macroevolution of long bone cross-sectional morphology. BMC Evol Biol 19:37

Kley NJ, Kearney M (2007) Adaptations for digging and burrowing. In: Hall BK (ed) Fins into Limbs: Evolution, Development, and Transformation. University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, pp 284-309

Loughry WJ, McDonough CM (2013) The Nine-banded Armadillo: A Natural History. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman

Marechal G, Goffart M, Aubert X (1963) Nouvelles recherches sur les proprieties du muscle squelettiques de Paresseux (Choloepus hoffmanni Peters). Arch Int Physiol Bioch 71:236-40

Marshall SK, Superina M, Spainhower KB, Butcher MT (2020) Forelimb myology of armadillos (Xenarthra: Cingulata, Chlamyphoridae): anatomical correlates with fossorial ability. J Anat. https://doi.org/10.1111/joa.13326

Martin ML, Travouillon KJ, Sherratt E, Fleming PA, Warburton NM (2019) Covariation between forelimb muscle anatomy and bone shape in an Australian scratch-digging marsupial: comparison of morphometric methods. J Morphol 280:1900-1915

McNab BK (1984) Physiological convergence amongst ant-eating and termite-eating mammals. J Zool 203:485-510

Melchor RN, Genise JF, Umazano AM, Superina M (2012) Pink fairy armadillo meniscate burrows and ichnofabrics from Miocene and Holocene interdune deposits of Argentina: paleoenvironmental and paleoecological significance. Paleogeogr Paleoclimatol Paleoecol 350-352:149-170

Mendel FC (1981) Use of hands and feet of two-toed sloths (Choloepus hoffmanni) during climbing and terrestrial locomotion. J Mammal 62:413-421

Mendel FC (1985) Use of hands and feet of three-toed sloths (Bradypus variegatus) during climbing and terrestrial locomotion. J Mammal 66:359-366

Miles SS (1941) The shoulder anatomy of the armadillo. J Mammal 22:157-169

Milne N, Toledo N, Vizcaíno SF (2011) Allometric and group differences in the xenarthran femur. J Mammal Evol 19:199-208

Minoprio JDL (1945) Sobre el Chlamyphorus truncatus Harlan. Acta Zool Lilloana 3:5-58

Miranda FR, Casali DM, Perini FA, Machado FA, Santos FR (2017) Taxonomic review of the genus Cyclopes Gray, 1821 (Xenarthra: Pilosa), with the revalidation and description of new species. Zool J Linnean Soc 183:687-721

Montgomery GG, Sunquist ME (1975) Impact of sloths on Neotropical forest energy flow and nutrient cycling. In: Golley FB, Medina E (eds) Tropical Ecological Systems: Trends in Terrestrial and Aquatic Research. Springer-Verlag, New York, pp 69-98

Montoya-Sanhueza G, Wilson LAB, Chinsamy A (2019) Postnatal development of the largest subterranean mammal (Bathygerus suillus): morphology, osteogenesis, and modularity of the appendicular skeleton. Dev Dyn 248:1101-1128

Murphy WJ, Eizirik E, Johnson WE, Zhang YP, Ryder OA, O’Brien SJ (2001a) Molecular phylogenetics and the origins of placental mammals. Nature 409:614-618

Murphy WJ, Eizirik E, O’Brien SJ, Madsen O, Scally M, Douady CJ, Teeling E, Ryder OA, Stanhope MJ, de Jong WW, Springer MS (2001b) Resolution of the early placental mammal radiation using Bayesian phylogenetics. Science 294:2348-2351

Nowak RM (1999) Walker’s Mammals of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Nyakatura JA (2012) The convergent evolution of suspensory posture and locomotion in tree sloths. J Mammal Evol 19:225-234

Nyakatura JA, Fischer MS (2011) Functional morphology of the muscular sling at the pectoral girdle in tree sloths: convergent morphological solutions to new functional demands? J Anat 319:360-374

Nyakatura JA, Petrovitch A, Fischer MS (2010) Limb kinematics during locomotion in the two-toed sloth (Choloepus hoffmanni, Xenarthra) and its implications for the evolution of the sloth locomotor apparatus. Zoology 113:221-234

Olson RA, Glenn ZD, Cliffe RN, Butcher MT (2018) Architectural properties of sloth forelimb muscles (Pilosa: Bradypodidae). J Mammal Evol 25:573-588

Olson RA, Womble MD, Thomas DR, Glenn ZD, Butcher MT (2016) Functional morphology of the forelimb of the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus): comparative perspectives on the myology of Dasypodidae. J Mammal Evol 23:49-69

R Core Team (2017) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna. https://www.R-project.org/

Revell LJ (2011) Phytools: an R package for phylogenetic comparative biology (and other things). Methods Ecol Evol 3:217-223

Richard-Hansen C, Vié JC, Vidal N, Kéravec J (1999) Body measurements on 40 species of mammals from French Guiana. J Zool 247:419-428

Rood JP (1970) Notes on the behavior of the pygmy armadillo. J Mammal 51:179

Rose J, Moore A, Russell A, Butcher M (2014) Functional osteology of the forelimb digging apparatus of badgers. J Mammal 95:543-558

Salton JA, Sargis EJ (2009) Evolutionary morphology of the Tenrecoidea (Mammalia) hindlimb skeleton. J Morphol 270:367-387

Salton JA, Szalay FS (2004) The tarsal complex of Afro-Malagasy Tenrecoidea: a search for phylogenetically meaningful characters. J Mammal Evol 11:73-104.

Samuels JX, Van Valkenburgh B (2008) Skeletal indicators of locomotor adaptations in living and extinct rodents. J Morphol 269:1387-1411

Sargis EJ (2002) Functional morphology of the hindlimb of tupaiids (Mammalia, Scandentia) and its phylogenetic implications. J Morphol 254:149-185

Scheidt A, Wolfer J, Nyakatura JA (2019) The evolution of femoral cross-sectional properties in sciuromorphic rodents: influence of body and locomotor ecology. J Morphol 280:1156-1169

Silveira L, de Almeida Jácomo AT, Furtado MM, Torres NM, Sollmann R, Vynne C (2009) Ecology of the giant armadillo (Priodontes maximus) in the grasslands of central Brazil. Edentata 8-10:25-34

Smith P (2009) FAUNA Paraguay Handbook of the Mammals of Paraguay. http://www.faunaparaguay.com

Spainhower KB, Cliffe RN, Metz AK, Barkett EM, Kiraly P, Thomas DR, Kennedy S, Avey-Arroyo J, Butcher MT (2018) Cheap labor: myosin fiber type expression and enzyme activity in the forelimb musculature of sloths (Pilosa: Xenarthra). J Appl Physiol 125:799-811

Spainhower KB, Metz AK, Yusuf ARS, Johnson LE, Avey-Arroyo J, Butcher MT (2020) Coming to grips with life upside down: how myosin fiber type and metabolic properties of sloth hindlimb muscles contribute to suspensory function. J Comp Physiol B. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00360-020-01325-x

Superina M (2008) The natural history of the pichi, Zaedyus pichiy, in western Argentina. In: Vizcaíno SF, Loughry WJ (eds) The Biology of The Xenarthra. University Press of Florida, Gainesville, pp 313-318

Superina M, Loughry WJ (2015) Why do xenarthrans matter? J Mammal 96:617-621

Szalay FS, Sargis EJ (2001) Model-based analysis of postcranial osteology of marsupials from the Palaeocene of Itaboraí (Brazil) and the phylogenetics and biogeography of Metatheria. Geodiversitas 23:139-302

Taylor BK (1978) The anatomy of the forelimb in the anteater (Tamandua) and its functional implications. J Morphol 157:347-367

Toledo N, Bargo MS, Cassini GH, Vizcaíno SF (2012) The forelimb of early Miocene sloths (Mammalia, Xenarthra, Folivora): morphometrics and functional implications for substrate preferences. J Mammal Evol 19:185-198

Toledo N, Cassini GH, Vizcaíno SF, Bargo, MS (2014) Mass estimation in Santacrucian sloths from the early Miocene Santa Cruz Formation of Patagonia, Argentina. Acta Palaeontol Pol 59:267-280

Urbani B, Bosque C (2007) Feeding ecology and postural behavior of the three-toed sloth (Bradypus variegatus flaccidus) in northern Venezuela. Mammal Biol 72:321-329

Vizcaíno SF, Fariña RA, Mazzetta GV (1999) Ulnar dimensions and fossoriality in armadillos. Acta Theriol 44:309-320

Vizcaíno SF, Milne N (2002) Structure and function in armadillo limbs (Mammalia: Xenarthra: Dasypodidae). J Zool 257:117-127

Wetzel RM (1985) The identification and distribution of recent Xenarthra (Edentata). In: Montogomery GG (ed) The Evolution and Ecology of Armadillos, Sloths, and Vermilinguas. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington and London, pp 5-21

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Darren Lunde (NMNH), Eileen Westwig (AMNH), and Bruce Patterson and Lauren Smith (FMNH) for coordinating access to museum collections. We thank The Sloth Sanctuary of Costa Rica for the opportunity to harvest bones from frozen sloth specimens. Thanks to the Instituto de Medicina y Biología Experimental de Cuyo, Mendoza, Argentina for access to rare armadillo specimens. Special thanks to Mykaela Wagner, Brooke Copland, Amber Landsman, Lindsey Moon, Chris Riwniak, Jacob Aiello, and Jessica Yeager for assistance with data collection and data entry. Portions of the work were submitted as a Masters Thesis by S.K.M.. The YSU Department of Biological Sciences and College of STEM are also gratefully acknowledged.

Funding

This work was supported by a Journal of Experimental Biology Travelling Fellowship to S.K.M. award number JEBTF-170817.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.K.M. developed the concepts and experimental approach, collected and analyzed data, and drafted and edited the manuscript; K.B.S collected data and revised the manuscript; B.T.S. developed the analytical approach, analyzed data, and edited the manuscript; T.P.D. developed the analytical approach, analyzed data, and edited the manuscript; M.T.B. developed the concepts and approach, collected and analyzed data, and drafted and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix 1

Appendix 1

List of skeletal specimens and museum collection or origin. Museum acronyms are as follows: NMNH, National Museum of Natural History (Washington D.C. USA); AMNH, American Museum of Natural History (New York, NY USA); FMNH, Field Museum of Natural History (Chicago, IL USA).

Species | Museum | Specimen Number |

|---|---|---|

Tolypeutes matacus | NMNH | 583,927 |

Tolypeutes matacus | NMNH | 291,935 |

Tolypeutes matacus | NMNH | 598,002 |

Tolypeutes matacus | AMNH | 248,394 |

Priodontes maximus | NMNH | 261,024 |

Priodontes maximus | NMNH | 270,373 |

Priodontes maximus | NMNH | 299,630 |

Chaetophractus villosus | NMNH | 396,655 |

Chaetophractus villosus | NMNH | 543,430 |

Chaetophractus villosus | NMNH | 155,411 |

Chaetophractus villosus | FMNH | 153,772 |

Chaetophractus villosus | FMNH | 134,611 |

Chaetophractus villosus | FMNH | 60,467 |

Chaetophractus vellerosus | – | Cve1a |

Chlamyphorus truncatus | – | Ct1a |

Zaedyus pichiy | FMNH | 153,782 |

Zaedyus pichiy | FMNH | 104,817 |

Zaedyus pichiy | FMNH | 23,809 |

Zaedyus pichiy | FMNH | 15,626 |

Cabassous centralis | FMNH | 121,224 |

Cabassous centralis | FMNH | 134,458 |

Cabassous unicinctus | AMNH | 209,943 |

Cabassous unicinctus | AMNH | 133,314 |

Cabassous unicinctus | AMNH | 133,317 |

Cabassous unicinctus | AMNH | 23,441 |

Euphractus sexcinctus | NMNH | 256,115 |

Euphractus sexcinctus | NMNH | 258,603 |

Euphractus sexcinctus | NMNH | 257,968 |

Dasypus septemcinctus* | AMNH | 133,258 |

Dasypus hybridus | AMNH | 205,708 |

Dasypus hybridus | AMNH | 205,707 |

Dasypus novemcinctus | – | Dn1b |

Dasypus novemcinctus | – | Dn2b |

Dasypus novemcinctus | – | Dn3b |

Dasypus novemcinctus | – | Dn4b |

Dasypus novemcinctus | NMNH | 053,321 |

Dasypus novemcinctus | NMNH | 240,091 |

Dasypus novemcinctus | NMNH | A49398 |

Cyclopes didactylus | NMNH | 304,941 |

Cyclopes didactylus | NMNH | 283,876 |

Cyclopes didactylus | NMNH | 012,097 |

Cyclopes didactylus | NMNH | 200,353 |

Cyclopes didactylus | AMNH | 139,228 |

Cyclopes didactylus | AMNH | 130,107 |

Cyclopes didactylus | AMNH | 97,317 |

Cyclopes didactylus | FMNH | 51,889 |

Tamandua tetradactyla | NMNH | 589,602 |

Tamandua tetradactyla | NMNH | 172,999 |

Tamandua tetradactyla | NMNH | 339,663 |

Tamandua tetradactyla | NMNH | 21,658 |

Tamandua tetradactyla | AMNH | 211,662 |

Tamandua tetradactyla | AMNH | 96,258 |

Tamandua tetradactyla | AMNH | 150,733 |

Tamandua tetradactyla | FMNH | 256,759 |

Bradypus variegatus | – | Bv1c |

Bradypus variegatus | – | Bv2c |

Bradypus variegatus* | – | Bv3c |

Bradypus variegatus | – | Bv4c |

Bradypus variegatus | – | Bv5c |

Bradypus variegatus* | – | Bv6c |

Bradypus variegatus | – | Bv7c |

Bradypus variegatus | – | Bv8c |

Bradypus tridactylus | FMNH | 93,296 |

Bradypus tridactylusd | AMNH | 130,106 |

Bradypus tridactylus | AMNH | 74,136 |

Choloepus hoffmanni | – | Ch3-Rc |

Choloepus hoffmanni | – | Ch3-Lc |

Choloepus hoffmanni | – | Ch5c |

Choloepus hoffmanni | – | Ch7c |

Choloepus hoffmanni | – | Ch8c |

Choloepus hoffmanni | – | Ch9c |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Marshall, S.K., Spainhower, K.B., Sinn, B.T. et al. Hind Limb Bone Proportions Reveal Unexpected Morphofunctional Diversification in Xenarthrans. J Mammal Evol 28, 599–619 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10914-021-09537-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10914-021-09537-w