Abstract

This paper provides a narrative review of the existing literature on differences in demographic and biological features of breast cancer at time of diagnosis between Black and White women in Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States. Electronic database searches for published peer-reviewed articles on this topic were conducted, and 78 articles were included in the final narrative review. Differences between Black and White women were compared for eight categories including age, tumour stage, size, grade, lymph node involvement, and hormone status. Black women were significantly more likely to present with less favourable tumour features at the time of diagnosis than White women. Significant differences were reported in age at diagnosis, tumour stage, size, grade and hormone status, particularly triple negative breast cancer. Limitations on the generalizability of the review findings are discussed, as well as the implications of these findings on future research, especially within the Canadian context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Breast cancer continues to be a significant cause of morbidity and mortality for Canadian women. Breast cancer was responsible for a quarter of new cancer diagnoses in women and 13% of all cancer-related deaths in women in 2017 [1]. The influence of various social and demographic factors on the morbidity and mortality associated with breast cancer has been well established in the literature [2]. Race is one such factor, which in some contexts is used as a variable in analysis and reporting.

Race is a social construct rather than a biological determinant of health. However, the product of the construct of race—racism, experienced at an institutional and interpersonal level—has a profound and measurable impact on racialized individuals in all sectors of society including the health care system. In this review the term race is used as a proxy for racism and to denote two groups of women, those identified as Black and those defined as White, whilst recognizing the diversity of experiences within these categories. The influence of race and arguably racism on the experience of breast cancer amongst women in the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US) is particularly striking and well-established in the literature. Less is known about how breast cancer outcomes differ between racialized women in Canada, given the current lack of race-based data collected in the Canadian health care system. Significant differences in breast cancer incidence, diagnosis and prognosis have been demonstrated between ethnic and racial groups in the US and the UK [2]. Despite a greater incidence of breast cancer amongst White women [3], prognosis for Black women with breast cancer has been noted to be poorer in numerous studies [4,5,6]. Black women had a lower rate of overall 5-year survival in some studies [7], as well as lower rates of distant relapse-free survival [8]. Disease recurrence was also noted to be greater amongst Black women in the US diagnosed with earlier-stage breast cancers [9]. However, similar findings were not observed in other studies based in the US or the UK. For example, Roseland et al. [10] noted no differences in mortality for patients diagnosed with stages I–III breast cancer in Michigan when data was stratified by race. In another retrospective single centre study in London, UK by Bowen et al. [11], no significant difference in overall survival was noted by race.

A number of social and demographic factors have been proposed to contribute to these findings, including differences in age at diagnosis [12,13,14], geographic location [14], socioeconomic status [4, 12], as well as individual and regional differences in breast cancer screening [15]. In addition to these factors, a number of studies have demonstrated differences in tumour biology and have suggested that these differences may also contribute to differences in breast cancer prognosis between Black and White women. In particular, later cancer stage at time of diagnosis [5], larger tumour size [6], and higher incidence of triple negative breast cancers [8, 16] amongst Black women have been noted in a number of studies in both the UK and the US.

This paper sets out to conduct a narrative review of the existing literature regarding the differences in certain demographic and biological features of breast cancer at the time of diagnosis, including age, tumour size, grade, hormone receptor status, and lymph node involvement, between Black and White women in the UK, Canada and the US. These features in particular are known to be associated with breast cancer prognosis, with poorer prognosis for patients with larger tumours at the time of diagnosis, triple negative hormone status, and axillary lymph node involvement [17,18,19].

Investigating the association of race and racism on these features of malignant breast tumours is particularly challenging in the Canadian context, where there is a lack of surveillance data that examines health outcome disparities among racialized groups, particularly amongst Black women. Surveillance data that includes information about race and ethnicity is collected in the US through organizations like the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program and the National Cancer Database (NCDB). In the UK, with a centralized publicly funded healthcare system that is more similar to the Canadian model of healthcare, race data is similarly collected through the National Health Service (NHS). Reviewing the existing UK and US literature can provide general trends in the characteristics of breast tumours in women belonging to these racialized groups, and may shed some light on the etiology of the aforementioned differences in diagnosis and prognosis. The implications of the findings of this narrative review are key for improved equity in breast cancer prevention, screening, and diagnosis and can guide future endeavours in research regarding breast cancer in the Canadian context.

Methods

A research librarian conducted electronic database searches of Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, Ovid EMB Reviews, CINAHL, and Web of Science. Searches were limited to English language reports and peer-reviewed literature from Canada, the US and the UK, published between 2005 and 2016. Search terms and keywords used with these bibliographic databases included but were not limited to: “African American”, “Black”, “Caribbean”, “non-White”, “breast neoplasms”, “carcinoma, lobular”, “tumour”, “age factors”, “delayed diagnosis”, “neoplasm grading”, “neoplasm invasiveness”, and “health status disparities”. For the Ovid MEDLINE search, similar terms were combined using the Boolean operator OR and separate concepts were combined using the Boolean operator AND. This initial search yielded a total of 6,434 results, which were reduced to 3215 entries following the removal of duplicate publications using EndNote.

Two authors (SG, JO) reviewed titles and abstracts of these publications to identify those that met inclusion criteria for full-text review (see Fig. 1). Eligibility was determined using the research question and was limited to articles reporting breast cancer characteristics at the time of diagnosis for Black women compared to White women. Articles that included other racialized groups in addition to Black and White women were also included. This preliminary screen identified 108 publications for full-text review. Details of the study design, population, time period, variables, outcomes, age at diagnosis, tumour type, stage of tumour, and prognosis were abstracted to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet by the authors. Of these, one article could not be accessed through the University of Toronto library system and a further 29 publications were deemed irrelevant, upon review. As such, the final number of publications included in this narrative literature review was 78 [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14, 20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81].

Results

Description of Studies

Almost all of the studies included in this study were conducted in the US, with two of the included studies conducted in the UK, and no studies from Canada met the inclusion criteria (see Table 1). There was a great deal of geographical variation within the US, with study locations including New York, California, Florida, Georgia, Utah, and Illinois. The studies included were published between 2005 and 2016, including patients diagnosed with breast cancer between 1975 and 2014.

Most of the included studies were retrospective and observational studies. There were eight prospective studies included, with an additional two studies utilizing prospective databases. The sample sizes varied widely in the included studies and ranged from a few hundred participants to hundreds of thousands of participants. Thirty-three of the included studies utilized data collected nationally by the SEER Program and the NCDB in the US. The remaining 45 studies utilized data from single centres, or multiple centres within a specific geographical region.

One of the studies included from the UK was a retrospective observational study conducted using data from a single East London hospital, enrolling a total of 445 participants [11]. The second UK study was a prospective cohort study, obtaining data from the medical records of 2956 patients at 127 hospitals across the UK [8].

Age at Diagnosis

Forty-four of the 78 articles included in this narrative review analyzed differences in age at diagnosis stratified by race (Table 1). Race was significantly associated with age at diagnosis in the thirty-two of these papers, and Black women were generally found to be diagnosed with breast cancer at a younger age than White women.

Method of reporting age varied substantially, with 28 of the articles reviewed using the median or mean age at diagnosis to analyze differences by race. Other methods of analysis include comparison of the incidence rate of breast cancer by age group [42, 55] and analysis of the proportion of breast cancer by race within given age brackets. The range of mean age at diagnosis for Black and White women were similar, ranging from 36 years [8] to 74.5 years [69]. However, Black women were younger than their White counterparts at diagnosis in thirty of the studies reviewed. A similar trend was noted in the incidence of breast cancer in younger age brackets. Black women were more likely to be diagnosed before the age of 50 [9, 32, 60, 75], and a higher incidence of breast cancer was noted amongst Black women before the age of 40 [42, 55].

Twelve of the articles reviewed found no statistically significant difference in average age at diagnosis by race. Most of these papers reported an average age at diagnosis between 50 and 65 years of age for both Black and White women [22, 28, 37,38,39, 50, 57, 82]. Additionally, two studies found that Black women were more likely to be diagnosed at an older age than White women [30, 74]. Of significance, Nassar et al. [30] looked at the age of diagnosis for ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), finding that Black women were diagnosed at a significantly older age (60 years) compared to White women (56 years; p < 0.001). However, another article in this review also looked at incidence of DCIS by race and noted that Black women were more likely to be diagnosed with DCIS at a younger age (≤ 40 years old) than White women [35].

Stage at Diagnosis

Breast cancer staging describes the degree of metastasis and disease progression. The reviewed literature reported breast cancer stage at the time of diagnosis either using a scale from 0 to IV or by describing tumour stage as local, regional or distant. Sixteen publications reported a significant difference in breast cancer stage between Black and White women, whilst no significant difference was observed in nine studies (Table 1).

Black women were significantly less likely to be diagnosed at earlier stages (I and II) of breast cancer compared to White women [2, 14, 66, 69]. An additional six studies found that a greater proportion of Black women were diagnosed with stage II, III, or IV breast cancers compared to White women [6, 7, 64, 71, 75, 80]. Warner et al. [71] found that 20% and 6% of Black women were diagnosed with stage III (n = 344/1718) and IV (n = 103/1718) breast cancers, compared to 11% and 4% of White women (n = 1947/17,696; n = 708/17,696) (p < 0.0001). Furthermore, the odds of Black women being diagnosed with stage III or IV tumours was significantly greater than White women (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.16–1.56). Similarly, Stark et al. [37] and Short et al. [77] found that a greater proportion (4.7% and 2.5%) of Black women were diagnosed with stage IV breast cancer compared to White women.

Two studies described breast cancer stage based on localization of the tumour and in both instances, differences were observed between Black and White women. Black women were significantly more likely to present with distant breast cancers compared to White women [5, 62]. However, it is important to note that nine studies reported no significant difference in stage at diagnosis between Black and White women [12, 22, 28, 39, 47, 58, 70, 78, 82].

Tumour Size

Twenty-seven articles included in this review analyzed tumour size at diagnosis. Of these articles, twenty articles indicated a significant difference in tumour size by race (Table 2). There was heterogeneity in the method of reporting tumour size. Fourteen articles used ranges of measurements similar to those found in the TNM classification system, the most commonly used system for tumour classification and gold standard of measurement. For this classification system, size was reported as ≤ 2 cm (T1), 2–5 cm (T2), or > 5 cm (T3 or greater). Of the remaining studies, ten compared results by mean size (cm).

Using different size cut-off points for comparison, Black women tended to be diagnosed with larger tumours compared to White women. Based on the TNM classification system, Black women were more likely to be diagnosed with larger (T3 or greater) tumours [22] and were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with tumours ≥ 5 cm compared to White women [4, 5, 81]. Using a lower measurement of ≥ 2 cm, a large proportion of women diagnosed with larger tumours were Black [43, 54, 67, 68, 80]. Eight of the studies looking at the relationship between race and tumour size at diagnosis found significant differences in mean and median tumour size at diagnosis, with Black women being diagnosed with significantly larger tumours [8, 38, 43, 74]. Average tumour size for Black women ranged from 1.7 [75] to 3.0 cm [28]. For White women, tumour size ranged from 1.2 [30] to 2.6 cm [38].

Seven studies found no significant difference in tumour size at diagnosis between Black and White women. Method of reporting tumour size was similar to the studies described above. Crowe et al. [57] and Stead et al. [25] found no significant difference in tumour size using the TNM classification system (p > 0.05). Furthermore, Maloney et al. [50] and Swede et al. [62] found no significant difference in mean tumour size at diagnosis between Black and White women (p > 0.05).

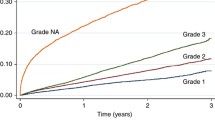

Tumour Grade

Grading of tumours describes the degree of differentiation of tumour cells, with poorly differentiated tumour cells carrying a worse prognosis. In the reviewed literature, tumours were assigned a grade of I (low), II (intermediate), or III (high). Low grade tumours were well differentiated tumours, carrying a more favourable prognosis, while high grade tumours were poorly differentiated. Twenty-eight articles included in this review reported tumour grade/tumour differentiation at the time of diagnosis (Tables 2 and 3). Of these articles, six studies reported no significant difference in tumour grade at the time of diagnosis based on race [8, 22, 30, 39, 74, 78]. Despite the lack of statistical significance, Copson et al. [8] observed that there was a greater proportion of Black women (n = 77/118, 68.1%) diagnosed with grade III tumours compared to White women (n = 1586/2690, 60.4%). Similar findings were reported by Baquet et al. [42], where 43.6% of Black women (n = 6922/15,877) were diagnosed with poorly differentiated breast cancer compared to 29.7% of White women (n = 46,182/155,495). However, the authors did not indicate whether this finding was statistically significant.

Of the articles reviewed, 21 found a significant difference between Black and White women in tumour grade at the time of diagnosis. These studies found that Black women were more likely to be diagnosed with poorly differentiated (grade III) tumours than White women. After adjusting for age, DeSantis et al. [4] found that the odds of Black women being diagnosed with a poorly differentiated tumour was 2.6 times greater than that of White women (OR 2.6, 95% CI 2.4–2.7). In addition, some studies reported that a smaller proportion of Black women were diagnosed with grade I tumours compared to White women. For example, Stark et al. [37] observed that at time of diagnosis 45.2% of Black women (n = 196/441) were diagnosed with grade III tumours and 19.6% were diagnosed with grade I tumours. This significantly differed from White women (n = 232/822), where 29.3% were diagnosed with grade III tumours and 30.3% with grade I tumours (p < 0.001).

Lymph Node Involvement

Twenty-one of the reviewed studies analyzed differences between Black and White women in relation to lymph node involvement (Table 3). Sixteen of these studies reported nodal involvement as either positive (i.e. at least one lymph node was involved) or negative (i.e. no lymph node involvement). Three studies reported nodal involvement as the average number of positive lymph nodes for Black and White participants [7, 8, 62].

Eleven of the studies reviewed found no significant difference in lymph node involvement by race. Of those studies that found a significant difference in nodal involvement by race, nine indicated a greater likelihood of positive lymph node involvement amongst Black women [4, 5, 7, 10, 57, 80]. Only one study reported a significantly greater likelihood of positive nodal involvement amongst White women with inflammatory breast cancer relative to Black women [12]. Of note, 46.8% of White women (n = 364/777) and 60.0% of Black women (n = 78/130) did not have lymph node involvement [12].

Tumour Type

Thirty-five out of the 78 reviewed publications assessed the expression of hormone receptors at the time of diagnosis for Black and White women (Table 4). The majority of studies presented findings on the expression of estrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR) and the expression of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) was discussed to a lesser extent. Ten studies reported that there was no significant difference in the expression of ER, PR and HER2, eight studies provided findings on the positive expression of ER and PR and seventeen studies presented results in relation to the negative expression of ER and PR. Twenty studies discussed the occurrence of triple negative breast cancer for Black and White women.

No Significant Difference

As mentioned above, ten studies found no significant difference in the expression of hormone receptors (ER and PR) and HER2 between Black and White women. Lund et al. [39] observed that the frequency of hormone receptor and HER2 expression did not differ between Black and White women (ER, p = 0.109; PR, p = 0.156; HER2, p = 0.765). Furthermore, Rizzo et al. [28] found that the frequency of triple negative breast cancer was not significantly different (p = 0.540). Findings from Chagpar et al. [74] indicate that there was no significant difference in the ER+ and PR+ tumours for Black and White women, 97.7% (n = 256/469) vs. 97.6% (n = 903/1415), (p = 0.682) and 86.0% (n = 222/469) vs 86.0% (n = 784/1415) (p = 0.873). Four studies found no significant difference in the frequency of HER2 expression for Black and White women [8, 9, 37, 67].

Positive Hormone Receptor Expression

With regards to the positive expression of ER or PR, four studies observed that a smaller proportion of Black women than White women presented at the time of diagnosis with ER+ or PR+ tumours [2, 54, 58, 75]. In Vicini et al. [75], 44% of Black women (n = 16/39) were diagnosed with ER+ tumours, whereas 82% of White women (n = 430/660) presented with ER+ tumours (p < 0.001). The same study found that 42% (n = 15/39) of Black women and 65% (n = 343/660) of White women were diagnosed with PR+ tumours (p = 0.004). Crowe et al. [57] and Short et al. [77] explored the expression of ER+/PR+ tumours in newly diagnosed women in the US. Both studies found that fewer Black women (n = 190/313; n = 40/99) were diagnosed with ER+/PR+ tumours than White women (n = 1541/2012; n = 267/476) (67.0% vs 82.0%, p < 0.001; 56.3% vs 75.4%, p = 0.001). Using all three markers of hormone receptor expression, Parise et al. [29] assessed differences between Black and White women using the California Cancer Registry. Findings indicate that Black women had a lower odds of being diagnosed with ER+/PR+/HER2+ (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.70–0.91) and ER+/PR+/HER2− (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.63–0.76) tumours when compared to White women.

Negative Hormone Receptor Expression

Seventeen of the reviewed articles compared the frequency of the absence of ER and PR expression on breast cancer tumours for Black and White women. Eleven studies found a significant difference in the proportion of Black and White women who presented with either ER−, PR−, or ER−/PR− tumours at the time of diagnosis. Findings indicate that the frequency of ER−, PR−, or ER−/PR− tumours was greater for Black women compared to White women. For example, Stead et al. [25] found that a significantly greater proportion of Black women (n = 52/177, 30%) were diagnosed with hormone receptor negative tumours than White women (n = 19/148, 13%) (p < 0.001). Moreover, Trivers et al. [16] and DeSantis et al. [4] found that Black women had a higher odds than White women of being diagnosed with hormone receptor negative (ER−/PR−) tumours (OR 1.90, 95% CI 1.05–3.46, and OR 2.11, 95% CI 2.04–2.18). Stark et al. [37] further observed differences in ER and PR expression. For ER− tumours, the proportion diagnosed was 35.7% for Black women (n = 157/441) and 22.1% for White women (n = 182/822), for PR− tumours the proportions were 45.2% vs 30.1%, and for ER−/PR− tumours the proportions were 35.0% vs 21.3% (p < 0.001). A study reporting only ER− tumour status, found that a greater proportion of Black women were diagnosed with ER− tumours (n = 101/272, 37.1%) than White women (n = 63/321, 19.8%) (p < 0.0001) [82]. Similarly, Rizzo et al. [28] observed a significant stage specific difference in the frequency of Black women (n = 47/93, 50.5%) with PR− tumours as compared to White women (n = 3/14, 21.5%) (p = 0.04). Finally, Anderson et al. [43] estimated the incident rate of ER− tumours using SEER databases and found a significantly higher incidence rate among Black women compared to White women (IRR = 1.4, 95% CI 1.4–1.4).

Triple Negative

Twenty of the articles included in this review explored the incidence of triple negative breast tumours, or tumours that are negative for estrogen, progesterone, or amplified HER2 receptors, by race. Seventeen of these articles found a significant difference in the incidence of triple negative tumours amongst women with breast cancer by race, with a significantly higher likelihood of triple negative tumours amongst Black women with breast cancer. For example, in one study conducted by Trivers et al. [16], Black women were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with triple negative tumours than White women (OR 2.41, 95% CI 1.81–3.21). In the UK, Copson et al. [8] similarly found a significantly higher incidence of triple negative breast cancer amongst Black women relative to White women (n = 30/118, 26.1% vs n = 478/2690, 18.6%, p < 0.05).

Interestingly, only three studies found no significant difference in triple negative tumours by race. For example, Bowen et al. [11] found no significant difference in the likelihood of triple negative tumours by race (p = 0.2) amongst women diagnosed with breast cancer in the UK. In a retrospective study by Lund et al. [39] using data obtained from the SEER Atlanta database, a greater proportion of Black women were diagnosed with triple negative tumours in comparison to non-Black women (n = 49/167, 29.3% vs n = 3/23, 13%), though this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.05). This study was small, including only 23 non-Black women in a sample size of 190 patients. In contrast, a larger retrospective study by Lund et al. [31] using data from the SEER Atlanta database found that Black women in the US were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with triple negative tumours than White women (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.2–2.9), even after adjusting for the patient’s age and income, as well as the stage and grade of the breast tumour.

HER2 Expression

As described above, only ten of the studies included in this narrative review analyzed HER2 expression by race. Overall, no significant difference in HER2 expression was found by race in any of the included studies. The POSH Study, a multi-centre prospective study examining the outcomes of breast cancer in younger women in the UK, found no significant difference in HER2 status by race or ethnicity (p = 0.065). The study did find significant differences by race in other measures, including tumour size at presentation, triple negative tumours, and distant relapse free survival [8]. Nonetheless, there was no significant difference noted by race regarding HER2 status.

In another prospective cohort study by Stark et al. [37], no significant difference was noted in HER2 status between Black and White women in the state of Michigan (n = 110/441, 25.0% Black vs n = 187/822, 22.8% White, p = 0.369). In this study, HER2 status was associated with tumour grade and stage for White women, though no significant interaction was noted for Black women.

Discussion

The aim of this narrative review was to provide an overview of the differences in breast tumour characteristics in the existing US, UK and Canadian literature for Black and White women (although no Canadian literature was found). Statistically significant differences were found in a number of categories described in this review. In those categories in which differences were found, Black women were consistently at greater risk of high-risk cancer features.

Age at diagnosis differed significantly by race, and Black women were over-represented in younger age groups. Younger age at diagnosis has been consistently linked with more aggressive breast cancers, especially when diagnosis is before 40 years of age [83]. As described above, the method of describing age at diagnosis varied between studies. Most studies looked at the median or mean age at diagnosis for comparison. While statistically significant differences were found, many of these studies reported an average age at diagnosis that was above the age of 50 years [13, 62]. There may be limited clinical application of those findings, given that most breast screening programs begin at the age of 50. In comparison, studies comparing incidence of breast cancer in younger age brackets found that Black women were over-represented in breast cancer diagnoses before the age of 50 [9, 20, 32, 60, 75]. Future studies looking at age of diagnosis should consider the clinical application of this data and include analysis on breast cancer diagnosis prior to 50 years of age.

Interestingly, two of the included studies found that Black women were more likely to be older at age of diagnosis [30, 74]. Nassar et al. [30] found that Black women were more likely to be diagnosed with DCIS at a significantly older age (60 years) compared to White women (56 years, p < 0.001). DCIS, or ductal carcinoma in situ, is an early stage of breast cancer and typically found during breast cancer screening with mammography. This is consistent, therefore, with other studies that found that Black women were more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer at a later stage of disease and less likely to be diagnosed at an earlier stage, as described above. Chagpar et al. [74] also found that Black women were more likely to be diagnosed at a later age (57 years) compared to White women (55 years, p < 0.05), but they also found that Black women were diagnosed with larger tumours (19 mm vs 17 mm, p = 0.009) at the time of diagnosis. In this single centre study, it can be speculated that Black women in this population were diagnosed with later stage disease at an older age and does not necessarily point to earlier disease in White women.

Fewer studies included stage at diagnosis in their analysis. Nonetheless, in sixteen of those studies which included tumour stage at diagnosis in their analysis, a significant difference was noted by race. Black women were significantly less likely to be diagnosed at earlier stages of cancer (Stage I–II) and were significantly more likely to be diagnosed at a later stage (Stage III–IV). Similarly, Black women were also more likely to have larger, poorly differentiated tumours at the time of diagnosis. Several explanations have been proposed in the literature for these differences. Newman [84] highlighted in the review the role of socioeconomic status in diagnosis of later stage breast cancer in Black women in the United States, despite similar uptake of screening mammography. Barriers to accessing healthcare may result in a delay of tissue diagnosis from the time of an abnormal screening test, for example, resulting in a later stage of disease at the time of diagnosis. However, Newman also argues that race cannot be seen as a substitute for socioeconomic status, pointing to differences in prevalence of more aggressive breast cancer subtypes (e.g. triple negative) by race. Continued research is needed to further elucidate the interaction between race, biology and socioeconomic factors to better interpret the differences in stage at diagnosis by race.

In terms of hormone receptor status, Black women were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with triple negative breast cancer relative to White women. They were also found to be more likely to have estrogen and progesterone receptor negative tumours, but no significant differences in HER2 receptor expression was found by race in any of the included studies. Triple negative breast tumours are not responsive to conventional and currently available targeted therapies and are associated with an overall poorer prognosis [25]. There are some who speculate that this may contribute to the differences in disease prognosis and recurrence by race, along with other tumour characteristics, treatment modalities and certain social factors [6, 8, 31]. Given the importance of targeted therapies in breast cancer management, further research into this area is warranted.

Several limitations of the studies included in this review are noted. The etiology of differences in tumour characteristics for Black and White women appears to be multifactorial, and not fully understood at this time [5]. However, several factors are known to be associated with breast cancer prognosis. These include the tumour traits included in this study, cancer screening uptake and availability [15], socioeconomic status [4, 12], and geography [14]. While many of the included studies included these factors in their analysis, there was significant variation between studies regarding which factors were included and how factors were controlled for.

Interestingly, a number of studies that included certain social and demographic factors found that the impact of race on the prevalence of high-risk cancer features persisted. In a large scale retrospective study using data collected from the National Cancer Database, DeSantis et al. [4] found that Black women were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer relative to White women even after controlling for the independent effects of health insurance status and educational attainment (OR 1.54, 95% CI 1.45–1.63). Similarly, Woods et al. [2] found that Black participants were significantly less likely to have stage I cancer (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.67–0.96, p = 0.02) at the time of diagnosis, and were significantly more likely to have stage III cancer (OR 1.50, 95% CI 1.11–2.01, p = 0.01) compared to White women, even after controlling for family history, health insurance, smoking, marital status, and whether the participant had reached menopause. Whilst no publications specific to differences in breast cancer prognosis for Black and White women in Canada were identified in this review, a recent Canadian study by Lofters et al. [85] found that immigrant women from Latin America and the Caribbean had a later stage of breast cancer at the time of diagnosis compared to non-immigrants, despite similar access to primary care in two Canadian provinces. It was speculated that there may be a component of genetic susceptibility to aggressive breast cancers amongst women of West African ancestry, given similar findings in studies of African American women in the US [85]. It is, however, challenging to tease these features apart, especially given the lack of race-based data collected in Canada or provided in this study.

In other studies included in this review, the effect of race diminished or was eliminated once social and demographic factors were accounted for. In a retrospective study using data from the SEER Detroit and Los Angeles databases by Lantz et al. [52], Black women were initially found to be significantly less likely to be diagnosed at an earlier stage of breast cancer (Stage I) relative to White women. However, after controlling for age, study site, education, income, and method of detection, no significant difference was found by race (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.57–1.10). In another smaller single centre retrospective study, no significant difference in age of diagnosis, tumour size, lymph node involvement, or hormone receptor status was found once SES was controlled for [50]. While the current narrative review focused on the incidence of high-risk tumour features by race, it has also highlighted the importance of accounting for social and demographic factors when assessing the impact of these high-risk tumour features on the disparities observed in breast cancer prognosis by race.

Finally, the majority of the studies included in this review did not describe how race information was obtained from participants. Amongst those studies that did describe how this information was obtained, there was significant variability. Methods included self-report [53, 54] and inference based on the race/ethnicity of the participant’s parents, birthplace, surname, or maiden name [41]. The importance of method of reporting race was highlighted in a retrospective study by Boehmer et al. [86], where they compared self-reported race to administrative race data in the context of a dental procedure. They found that administrative data was more likely to be incorrect for individuals who belong to a racial or ethnic group other than White. Future studies investigating breast cancer outcomes by race should make note of the method of reporting of race, as well as the number of individuals for whom race/ethnicity data is missing.

Overall, the literature currently demonstrates significant differences in the prevalence of high-risk breast cancer features by race in the US, and in a few more recent studies conducted in the UK. Given the unique social and political histories of each of these countries, generalizability of these findings to the Canadian context is somewhat limited. Furthermore, as Black is an umbrella term that includes a great deal of diversity, the composition of Black communities differs in each of these countries. Likewise, the impact of health insurance and differing modalities of healthcare delivery on breast cancer outcomes cannot be underestimated. Nonetheless, the findings of this review reinforce the importance of collecting race data in order to identify the impact of structural racism on health outcomes and better inform health screening practices, management guidelines, and to detect and reduce inequity in healthcare outcomes within the Canadian healthcare system.

References

Canadian Cancer Society’s Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics: Canadian Cancer Statistics 2017. https://www.cancer.ca/~/media/cancer.ca/CW/cancer%20information/cancer%20101/Canadian%20cancer%20statistics/Canadian-Cancer-Statistics-2017-EN.pdf. Accessed Jan 2019.

Woods SE, Luking R, Atkins B, Engel A. Association of race and breast cancer stage. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(5):4.

Smigal C, Jemal A, Ward E, Cokkinides V, Smith R, Howe HL, et al. Trends in breast cancer by race and ethnicity: update 2006. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56(3):168–83.

DeSantis C, Jemal A, Ward E. Disparities in breast cancer prognostic factors by race, insurance status, and education. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(9):1445–50.

Barcenas CH, Wells J, Chong D, French J, Looney SW, Samuel TA. Race as an independent risk factor for breast cancer survival: breast cancer outcomes from the Medical College of Georgia Tumor Registry. Clin Breast Cancer. 2010;10(1):59–63.

Tao L, Gomez SL, Keegan THM, Kurian AW, Clarke CA. Breast cancer mortality in African-American and Non-Hispanic White women by molecular subtype and stage at diagnosis: a population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2015;24(7):1039–45.

McBride R, Hershman D, Tsai W-Y, Jacobson JS, Grann V, Neugut AI. Within-stage racial differences in tumor size and number of positive lymph nodes in women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2007;110(6):1201–8.

POSH study steering group, Copson E, Maishman T, Gerty S, Eccles B, Stanton L, et al. Ethnicity and outcome of young breast cancer patients in the United Kingdom: the POSH study. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(1):230–41.

Moran MS, Yang Q, Harris LN, Jones B, Tuck DP, Haffty BG. Long-term outcomes and clinicopathologic differences of African-American versus white patients treated with breast conservation therapy for early-stage breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;113(9):2565–74.

Roseland ME, Pressler ME, Lamerato EL, Krajenta R, Ruterbusch JJ, Booza JC, et al. Racial differences in breast cancer survival in a large urban integrated health system: disparities in breast cancer survival. Cancer. 2015;121(20):3668–75.

Bowen RL, Duffy SW, Ryan DA, Hart IR, Jones JL. Early onset of breast cancer in a group of British black women. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(2):277–81.

Yang R, Cheung MC, Hurley J, Byrne MM, Huang Y, Zimmers TA, et al. A comprehensive evaluation of outcomes for inflammatory breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;117(3):631–41.

Kwan ML, Kushi LH, Weltzien E, Maring B, Kutner SE, Fulton RS, et al. Epidemiology of breast cancer subtypes in two prospective cohort studies of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11(3):R31.

Sariego J. Patterns of breast cancer presentation in the United States: does geography matter? Am Surg. 2009;75(7):545–50.

Anderson WF, Jatoi I, Devesa SS. Assessing the impact of screening mammography: breast cancer incidence and mortality rates in Connecticut (1943–2002). Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;99(3):333–40.

Trivers KF, Lund MJ, Porter PL, Liff JM, Flagg EW, Coates RJ, et al. The epidemiology of triple-negative breast cancer, including race. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(7):1071–82.

Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, Hanna WM, Kahn HK, Sawka CA, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(15):4429–34.

Bundred NJ. Prognostic and predictive factors in breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2001;27:137.

Carter C, Allen C, Henson DE. Relation of tumor size, lymph node status, and survival in 24,740 breast cancer cases. Cancer. 1989;63(1):181–7.

Cunningham JE, Montero AJ, Garrett-Mayer E, Berkel HJ, Ely B. Racial differences in the incidence of breast cancer subtypes defined by combined histologic grade and hormone receptor status. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(3):399–409.

Cronin KA, Harlan LC, Dodd KW, Abrams JS, Ballard-Barbash R. Population-based estimate of the prevalence of HER-2 positive breast cancer tumors for early stage patients in the US. Cancer Investig. 2010;28(9):963–8.

Chu QD, Burton G, Glass J, Smith MH, Li BDL. Impact of race and ethnicity on outcomes for estrogen receptor-negative breast cancers: experience of an academic center with a Charity Hospital. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(5):585–92.

Yang R, Cheung MC, Franceschi D, Hurley J, Huang Y, Livingstone AS, et al. African-American and low-socioeconomic status patients have a worse prognosis for invasive ductal and lobular breast carcinoma: do screening criteria need to change? J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208(5):853–68.

Virnig BA, Baxter NN, Habermann EB, Feldman RD, Bradley CJ. A matter of race: early-versus late-stage cancer diagnosis. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(1):160–8.

Stead LA, Lash TL, Sobieraj JE, Chi DD, Westrup JL, Charlot M, et al. Triple-negative breast cancers are increased in black women regardless of age or body mass index. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11(2):R18.

Setiawan VW, Monroe KR, Wilkens LR, Kolonel LN, Pike MC, Henderson BE. Breast cancer risk factors defined by estrogen and progesterone receptor status: the Multiethnic Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(10):1251–9.

Schootman M, Jeffe DB, Gillanders WE, Aft R. Racial disparities in the development of breast cancer metastases among older women: a Multilevel Study. Cancer. 2009;115(4):731–40.

Rizzo M, Lund MJ, Mosunjac M, Bumpers H, Holmes L, O’Regan R, et al. Characteristics and treatment modalities for African American women diagnosed with stage III breast cancer. Cancer. 2009;115(13):3009–15.

Parise CA, Bauer KR, Brown MM, Caggiano V. Breast cancer subtypes as defined by the estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) among Women with Invasive Breast Cancer in California, 1999–2004. Breast J. 2009;15(6):593–602.

Nassar H, Sharafaldeen B, Visvanathan K, Visscher D. Ductal carcinoma in situ in African American versus Caucasian American women: analysis of clinicopathologic features and outcome. Cancer. 2009;115(14):3181–8.

Lund MJ, Trivers KF, Porter PL, Coates RJ, Leyland-Jones B, Brawley OW, et al. Race and triple negative threats to breast cancer survival: a population-based study in Atlanta. GA Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;113(2):357–70.

Gnerlich JL, Deshpande AD, Jeffe DB, Sweet A, White N, Margenthaler JA. Elevated breast cancer mortality in women younger than age 40 years compared with older women is attributed to poorer survival in early-stage disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208(3):341–7.

Coughlin SS, Richardson LC, Orelien J, Thompson T, Richards B, Sabatino SA, et al. Contextual analysis of breast cancer stage at diagnosis among women in the United States. Open Health Serv Policy J. 2004;2011:21.

Campbell RT, Li X, Dolecek TA, Barrett RE, Weaver KE, Warnecke RB. Economic, racial and ethnic disparities in breast cancer in the US: towards a more comprehensive model. Health Place. 2009;15(3):870–9.

Bharat A, Aft RL, Gao F, Margenthaler JA. Patient and tumor characteristics associated with increased mortality in young women (≤40 years) with breast cancer: young women with breast cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100(3):248–51.

Ambrosone CB, Ciupak GL, Bandera EV, Jandorf L, Bovbjerg DH, Zirpoli G, et al. Conducting molecular epidemiological research in the age of HIPAA: a Multi-Institutional Case-Control Study of breast cancer in African-American and European-American Women. J Oncol. 2009;2009:1–15.

Stark A, Kapke A, Schultz D, Brown R, Linden M, Raju U. Advanced stages and poorly differentiated grade are associated with an increased risk of HER2/neu positive breast carcinoma only in White women: findings from a prospective cohort study of African-American and White-American women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(3):405–14.

Marti JL. Receptor status and ethnicity of indigent patients with breast cancer in New York City. Arch Surg. 2008;143(12):1227.

Lund MJB, Butler EN, Bumpers HL, Okoli J, Rizzo M, Hatchett N, et al. High prevalence of triple-negative tumors in an urban cancer center. Cancer. 2008;113(3):608–15.

Kenney RJ, Marszalek JM, McNally ME, Nelson BV, Herati AS, Talboy GE. The effects of race and age on axillary lymph node involvement in breast cancer patients at a Midwestern safety-net hospital. Am J Surg. 2008;196(1):64–9.

Brown M, Tsodikov A, Bauer KR, Parise CA, Caggiano V. The role of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 in the survival of women with estrogen and progesterone receptor-negative, invasive breast cancer: the California Cancer Registry, 1999–2004. Cancer. 2008;112(4):737–47.

Baquet CR, Mishra SI, Commiskey P, Ellison GL, DeShields M. Breast cancer epidemiology in blacks and whites: disparities in incidence, mortality, survival rates and histology. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(5):480–9.

Anderson WF, Rosenberg PS, Menashe I, Mitani A, Pfeiffer RM. Age-related crossover in breast cancer incidence rates between black and white ethnic groups. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(24):1804–14.

Morris GJ, Naidu S, Topham AK, Guiles F, Xu Y, McCue P, et al. Differences in breast carcinoma characteristics in newly diagnosed African-American and Caucasian patients: a single-institution compilation compared with the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and end results database. Cancer. 2007;110(4):876–84.

Karami S, Young HA, Henson DE. Earlier age at diagnosis: another dimension in cancer disparity? Cancer Detect Prev. 2007;31(1):29–34.

Halpern MT, Bian J, Ward EM, Schrag NM, Chen AY. Insurance status and stage of cancer at diagnosis among women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2007;110(2):403–11.

Hahn KME, Bondy ML, Selvan M, Lund MJ, Liff JM, Flagg EW, et al. Factors associated with advanced disease stage at diagnosis in a population-based study of patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(9):1035–44.

Bauer KR, Brown M, Cress RD, Parise CA, Caggiano V. Descriptive analysis of estrogen receptor (ER)-negative, progesterone receptor (PR)-negative, and HER2-negative invasive breast cancer, the so-called triple-negative phenotype: a population-based study from the California cancer Registry. Cancer. 2007;109(9):1721–8.

Sassi F, Luft HS, Guadagnoli E. Reducing racial/ethnic disparities in female breast cancer: screening rates and stage at diagnosis. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2165–72.

Maloney N, Koch M, Erb D, Schneider H, Goffman T, Elkins D, et al. Impact of race on breast cancer in lower socioeconomic status women. Breast J. 2006;12(1):58–62.

Li CI, Malone KE, Saltzman BS, Daling JR. Risk of invasive breast carcinoma among women diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ and lobular carcinoma in situ, 1988–2001. Cancer. 2006;106(10):2104–12.

Lantz PM, Mujahid M, Schwartz K, Janz NK, Fagerlin A, Salem B, et al. The influence of race, ethnicity, and individual socioeconomic factors on breast cancer stage at diagnosis. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2173–8.

Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, Conway K, et al. Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA. 2006;295:2492.

Yankaskas BC, Gill KS. Diagnostic mammography performance and race: outcomes in Black and White women. Cancer. 2005;104(12):2671–81.

Joslyn SA, Foote ML, Nasseri K, Coughlin SS, Howe HL. Racial and ethnic disparities in breast cancer rates by age: NAACCR Breast Cancer Project. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;92(2):97–105.

Hance K, Anderson WF, Devesa SS, Young HA, Levine P. Trends in inflammatory breast carcinoma incidence and survival: the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program at the National Cancer Institute. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(13):966–75.

Crowe JP, Patrick RJ, Rybicki LA, Grundfest-Broniatowski S, Kim JA, Lee KB. Race is a fundamental prognostic indicator for 2325 Northeastern Ohio Women with Infiltrating Breast Cancer. Breast J. 2005;11(2):124–8.

Chlebowski RT, Chen Z, Anderson GL, Rohan T, Aragaki A, Lane D, et al. Ethnicity and breast cancer: factors influencing differences in incidence and outcome. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(6):439–48.

Wieder R, Shafiq B, Adam N. African American race is an independent risk factor in survival from initially diagnosed localized breast cancer. J Cancer. 2016;7(12):1587–98.

Thomas P, Killelea BK, Horowitz N, Chagpar AB, Lannin DR. Racial differences in utilization of breast conservation surgery: results from the national cancer data base (NCDB). Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(10):3272–83.

Tao L, Chu L, Wang LI, Moy L, Brammer M, Song C, et al. Occurrence and outcome of de novo metastatic breast cancer by subtype in a large, diverse population. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27(9):1127–38.

Swede H, Sarwar A, Magge A, Braithwaite D, Cook LS, Gregorio DI, et al. Mortality risk from comorbidities independent of triple-negative breast cancer status: NCI-SEER-based cohort analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2016;27(5):627–36.

Roberts MC, Weinberger M, Dusetzina SB, Dinan MA, Reeder-Hayes KE, Carey LA, et al. Racial variation in the uptake of onco type DX testing for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(2):130–8.

Monzavi-Karbassi B, Siegel ER, Medarametla S, Makhoul I, Kieber-Emmons T. Breast cancer survival disparity between African American and Caucasian women in Arkansas: a race-by-grade analysis. Oncol Lett. 2016;12(2):1337–42.

Krok-Schoen JL, Fisher JL, Baltic RD, Paskett ED. White-Black differences in cancer incidence, stage at diagnosis, and survival among adults aged 85 years and older in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2016;25(11):1517–23.

Iqbal J, Ginsburg O, Rochon PA, Sun P, Narod SA. Differences in breast cancer stage at diagnosis and cancer-specific survival by race and ethnicity in the United States. JAMA. 2015;313(2):165.

George P, Chandwani S, Gabel M, Ambrosone CB, Rhoads G, Bandera EV, et al. Diagnosis and surgical delays in African American and white women with early-stage breast cancer. J Womens Health. 2015;24(3):209–17.

Chen L, Li CI. Racial disparities in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment by hormone receptor and HER2 status. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2015;24(11):1666–72.

Aggarwal H, Callahan CM, Miller KD, Tu W, Loehrer PJ. Are there differences in treatment and survival between poor, older black and white women with breast cancer? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(10):2008–13.

Sturtz LA, Melley J, Mamula K, Shriver CD, Ellsworth RE. Outcome disparities in African American women with triple negative breast cancer: a comparison of epidemiological and molecular factors between African American and Caucasian women with triple negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2014;14(1):62.

Warner ET, Tamimi RM, Hughes ME, Ottesen RA, Wong Y-N, Edge SB, et al. Time to diagnosis and breast cancer stage by race/ethnicity. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;136(3):813–21.

Lepeak L, Tevaarwerk A, Jones N, Williamson A, Cetnar J, LoConte N. Persistence in breast cancer disparities between African Americans and Whites in Wisconsin. WMJ. 2011;110(1):6.

Downing S, Akinrinlola A, Siram SM, DeWitty RL, Paul H, Dawson K, et al. T4b breast masses: a retrospective review of 12 cases presenting to a metropolitan tertiary care center. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(8):757–61.

Chagpar AB, Crutcher CR, Cornwell LB, McMasters KM. Primary tumor size, not race, determines outcomes in women with hormone-responsive breast cancer. Surgery. 2011;150(4):796–801.

Vicini F, Jones P, Rivers A, Wallace M, Mitchell C, Kestin L, et al. Differences in disease presentation, management techniques, treatment outcome, and toxicities in African-American women with early stage breast cancer treated with breast-conserving therapy. Cancer. 2010;116(14):3485–92.

Stark A, Kleer CG, Martin I, Awuah B, Nsiah-Asare A, Takyi V, et al. African ancestry and higher prevalence of triple-negative breast cancer: Findings from an international study. Cancer. 2010;116(21):4926–32.

Short LJ, Fisher MD, Wahl PM, Kelly MB, Lawless GD, White S, et al. Disparities in medical care among commercially insured patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer: opportunities for intervention. Cancer. 2009;116:193.

Sachdev J, Ahmed S, Mirza M, Farooq A, Kronish L, Jahanzeb M. Does race affect outcomes in triple negative breast cancer? Breast Cancer Basic Clin Res. 2010;4:23–33.

O’Brien KM, Cole SR, Tse C-K, Perou CM, Carey LA, Foulkes WD, et al. Intrinsic breast tumor subtypes, race, and long-term survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(24):6100–10.

Lund MJ, Butler EN, Hair BY, Ward KC, Andrews JH, Oprea-Ilies G, et al. Age/race differences in HER2 testing and in incidence rates for breast cancer triple subtypes: a population-based study and first report. Cancer. 2010;116:2549.

Katz A, Burke LP, Brinson M. Demographic characterization of patients with large breast-cancer: an under-recognized public health problem. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(2):666–79.

Jiagge E, Jibril AS, Chitale D, Bensenhaver JM, Awuah B, Hoenerhoff M, et al. Comparative analysis of breast cancer phenotypes in African American, White American, and West Versus East African patients: correlation between african ancestry and triple-negative breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(12):3843–9.

Anders CK, Johnson R, Litton J, Phillips M, Bleyer A. Breast cancer before age 40 years. Semin Oncol. 2009;36(3):237–49.

Newman L. Breast cancer disparities: socioeconomic factors versus biology. Ann Surg Oncol. 2017;24:2869–75.

for the CanIMPACT Team, Lofters AK, McBride ML, Li D, Whitehead M, Moineddin R, et al. Disparities in breast cancer diagnosis for immigrant women in Ontario and BC: results from the CanIMPACT study. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):42.

Boehmer U, Kressin NR, Berlowitz DR, Christiansen CL, Kazis LE, Jones JA. Self-reported vs administrative race/ethnicity data and study results. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(9):1471–2.

Robbins HA, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Shiels MS. Age at cancer diagnosis for blacks compared with whites in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(3):dju489. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju489.

Acknowledgements

Grant funding was provided by the CIBC Medical Bursary in Breast Cancer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest to report for any of the authors.

Ethical Approval

All authors have reviewed the submitted manuscript and approve the manuscript for submission.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Osei-Twum, JA., Gedleh, S., Lofters, A. et al. Differences in Breast Cancer Presentation at Time of Diagnosis for Black and White Women in High Resource Settings. J Immigrant Minority Health 23, 1305–1342 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01161-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01161-3