Abstract

Literature has argued that income inequality crowds out trust. However, whether income inequality makes people less trusting depends on how they perceive income inequality within their personal social context and social cognition. In this paper we therefore conjecture that the relationship of income inequality to trust depends on how income inequality affects inequality of life satisfaction. If life satisfaction inequality is high, distrust is generated among the least happy. This will increase polarization and the risk of rebellion, thereby also affecting trust among the happier people. Thus, life satisfaction inequality may be an essential factor in the relationship between income inequality and trust. In previous literature, the potential mediating role of life satisfaction inequality in the relationship between income inequality and social trust has not yet received attention. We test our model by panel analysis on 25 OECD countries in the period 1990–2014. The panel analysis shows that income inequality increases life satisfaction inequality and that both income inequality and life satisfaction inequality have a significant negative impact on social trust. Mediation tests show complementary mediation: besides the direct negative effect of income inequality on trust, we find an indirect effect mediated by life satisfaction inequality. This indirect effect counts for 20% of the total effect of income inequality on trust. Our results imply that policy options for increasing trust are not limited to countering income inequality, but can also include policy measures that directly reduce inequality of life satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In recent years, research interest has increasingly shifted to the role of income inequality as a determinant of well-being. With data based on fifteen years of research on income and wealth inequality, Piketty (2014) showed that income and wealth inequality have both been rising continuously since the 1980s. Sixty per cent of economic growth since the 1960s has gone to the top 1% (Piketty and Saez 2013). This has spurred interest in the effect of income inequality on well-being (Berg and Ostry 2011; Bastagli et al. 2012; Ostry et al. 2014; OECD 2012; Berg and Veenhoven 2010; Oshio and Kobayashi 2010; Schneider 2012; Zagorski et al. 2014; Verme 2011). Wilkinson and Pickett (2010) have argued that inequality negatively affects physical and mental health and therefore, ultimately, human flourishing. Empirical research has shown income inequality to have an impact on all kinds of socio-economic processes, posing a threat to the social tissue that is essential to keep the economy going (Berg and Veenhoven 2010; Oshio and Kobayashi 2010; Verme 2011; Zagorski et al. 2014).

Previous research has also shown that income inequality affects social trust (Kawachi and Kennedy 1997; Knack and Keefer 1997; Zak and Knack 2001; Oishi et al. 2011; Elgar and Aitken 2011; Barone and Mocetti 2016). Social trust in a society is important for several reasons. First, it is a prerequisite for achieving collective prosperity in a capitalist economy (Fukuyama 1995). Trust leads to openness and a willingness to close deals with other members of society (Rahn and Transue 1998). In addition, it reduces transaction costs, since high levels of trust require fewer checks and balances, as well as less detailed contracts or resources in the form of deposits or other guarantees to ensure the fulfillment of mutual obligations. As a result, countries with increased social capital levels, which strongly correlates with trust, have more efficient financial and labor markets. Another reason that the average level of social trust is so important is that it is a relational concept that captures those interpersonal or collective dimensions of a good society that are not reducible to the aggregation of how individuals are doing (Helliwell and Putnam 2004). Individuals can only truly flourish in relationship to other human beings.

That income inequality has a negative influence on social trust is not a given, however, as other research has not been able to identify this effect (Leigh 2006; Steijn and Lancee 2011; Bergh and Bjørnskov 2014). In this paper we will therefore focus on life satisfaction inequality. Since humans are social beings, a society would need relative equality in happiness levels to keep functioning peacefully (Kalmijn and Veenhoven 2005). Ovaska and Takashima (2010) have argued that keeping happiness inequality to a minimum is necessary in order to ensure that everyone benefits from increases in average happiness. The reason is that although there are macroeconomic policies that can ‘lift all boats’, an increase in average happiness does not by definition mean that everyone benefits. This is problematic, since big differences in happiness within countries pose a threat to social trust and political stability (Caruso and Schneider 2011; Guimaraes and Sheedy 2012).

Life satisfaction inequality might be a better predictor of social trust than income inequality, because there are theoretical reasons that the relationship between income inequality and social trust is contingent. Basing her argument on social cognition literature, Schneider (2012) has suggested that whether income inequality makes people more or less happy depends on how they perceive it within their personal social context. If income inequality is considered as representing a high potential for social mobility, people with low income might see significant inequality offering an opportunity for improving their situation later in life. The inequality has a positive value in this case. Then, the negative relationship between income inequality and social trust will disappear. Only insofar as income inequality is valued negatively will it increase inequality in life satisfaction and crowd out social trust. That means that income inequality may ultimately have a negative influence on social trust, but only indirectly through its influence on life satisfaction inequality.

While the link between income inequality and inequality in life satisfaction has had some attention in literature (Ott 2005; Ovaska and Takashima 2010; Delhey and Kohler 2011; Becchetti et al. 2013), the influence of life satisfaction inequality on social trust—and the potential mediating role of this type of inequality in the relationship between income inequality and social trust—has not so far been researched. It is the subject of investigation in this paper. Our principal research question is therefore as follows: How does life satisfaction inequality affect social trust, and to what extent does life satisfaction inequality mediate the relationship between income inequality and social trust? In order to answer our principal question, we look at two sub questions. First, how is life satisfaction inequality related to income inequality? Second, how is social trust related to life satisfaction inequality? Based on a sample of 25 countries, we used panel analysis to estimate the relationships between income inequality, life satisfaction inequality and social trust.

The structure of this paper will be as follows. Section 2 presents a review of the literature on the relationships between income inequality and trust, and between income inequality and life satisfaction inequality. Section 3 describes the relationship between life satisfaction inequality and trust, and introduces the conceptual framework and hypotheses, including the mediation hypothesis. Section 4 outlines our methodology. Section 5 presents the results of the empirical analysis, and Sect. 6 summarizes the main findings and discusses their policy implications.

2 Literature review

No society can surely be flourishing and happy, of which the greater part of the members are poor and miserable. Adam Smith (1776, VIII page 94)

In this section we first present an overview of the literature on the relationship between income inequality and social trust. Then we examine the literature on the influence of income inequality on inequality in life satisfaction.

2.1 Income inequality and trust

Generalized trust is one of the measurable components of social cohesion (Helliwell and Putnam 2004; Bjørnskov 2005). Generalized trust entails trusting people you do not know personally (Berggren and Jordahl 2006). If a certain group in a society is marginalized, this might make it feel less associated with the rest of the society, and trust that society less. If the marginalization endures, this group might either opt for violent resistance or develop aggressive opportunistic behavior towards the rest of society, resulting in higher crime rates and deteriorating social trust generally. In the words of Caruso and Schneider (2011: S38): “poverty and income inequality would feed frustration, hatred and grievance which make political violence more likely.” Thus, as income inequality decreases the life satisfaction of certain groups, it affects social cohesion and social trust within society as a whole. Piazza (2011) provides an overview of the literature on the link between socio-economic factors and terrorism, concluding that the economic status of a country’s minority groups is more important than the overall wealth of the country. This fits with the above literature on the psychological effects of income inequality.

A number of articles have been published on the link between income inequality and trust. Kawachi and Kennedy (1997) found a strong association between income inequality and the lack of social trust. Knack and Keefer (1997) and Zak and Knack (2001) provided further empirical evidence for this association, while Oishi et al. (2011) found that social trust is a robust mediator of the impact of income inequality on average life satisfaction. Elgar and Aitken (2011) also found a significant negative causal relationship between income inequality and trust, and showed trust to be a significant mediator in the relationship between income inequality and homicide statistics across countries. Leigh (2006) claimed that on a regional level, ethnic heterogeneity appears to be of greater importance than income inequality in explaining trust. On a national level however, he found a negative causal effect from inequality to trust. Steijn and Lancee (2011) have provided a thorough discussion of this relationship and the weaknesses of research on the topic. They argued that one must distinguish between inequality effects and wealth effects and must control for different impacts for high income countries and other countries. Their analysis of income inequality in 20 countries led to the conclusion that once national wealth is controlled for, inequality no longer seems to explain trust. They stressed, however, that their sample only includes countries with very little inequality, and this may explain their results. Nor did Bergh and Bjørnskov (2014) find a causal relationship between inequality and trust, while they did find an opposite causal relationship. However, they do not use panel data. Barone and Mocetti (2016) used a panel regression, in which they exploited predicted exposure to technological change as an instrument for income inequality. They also considered the income shares of the top 10 and the top 1 percent, as well as intergenerational income mobility, in addition to the traditional Gini index. They found that inequality negatively affects generalized trust in developed countries, regardless of which measure is used.

2.2 Income Inequality and Inequality of Life Satisfaction

Among life evaluation standards, life satisfaction is one of the most prominent. It provides a comprehensive appraisal of life as it is, in comparison with how life should be (Chin-Hon-Foei 1989; Veenhoven 1990, 1995, 2000, 2002). While a vast body of literature exists on the study of average life satisfaction within nations as well as its relationship with income inequality (Oshio and Kobayashi 2010; Verme 2011; Zagorski et al. 2014), only a few papers have drawn attention to the relationship between income inequality and inequality in life satisfaction (Ott 2005; Ovaska and Takashima 2010; Delhey and Kohler 2011; Becchetti et al. 2013).

The positive link between inequality in life satisfaction and income inequality can be based on the standard micro assumption that utility increases with income (or consumption that income buys). People with higher income are generally more satisfied than people with low income. This means that the more unequal the income distribution, the higher the differences in life satisfaction. While this is true, marginal utility of income diminishes as income increases. Thus, one should expect that life satisfaction inequality would always be less than income inequality. The law of diminishing marginal utility is well established in economics and confirmed by much research (Hagerty and Veenhoven 2003; Easterlin and Angelescu 2009; Clark and Senik 2011; Layard 2010; Deaton 2008; Inglehart et al. 2008). Gandelman and Porzecanski (2013), who computed Gini-coefficients for income, happiness and utility, found that the Gini coefficient for happiness is indeed significantly lower than the Gini coefficient for income. Thus, they confirm that the concept of diminishing marginal utility also applies to life satisfaction (inequality).

Another explanation for the presumed link between income inequality and inequality in life satisfaction given by Becchetti et al. (2013) follows from the well-known finding that it is not absolute income but the differences in absolute income that people care about (Alpizar et al. 2005; Brekke and Howarth 2002; Carlsson et al. 2007; Clark and Oswald 1996; Solnick and Hemenway 1998). The impact of income on life satisfaction depends on the reference group to which most people compare their personal situation. On the one hand, if people associate with a nation or overall income at country level, national statistics will have an impact on how people feel about their social position, and thus impact on their life satisfaction. This may translate as an effect of income inequality on life satisfaction inequality, as the focus on relative income position enforces the perception of inequality.

On the other hand, a well-known phenomenon in economics is the keeping-up-with-the-Joneses effect, stating that comparison with neighbors and family in a comparable socio-economic position is more important than comparison with people or groups with whom one has no personal connection. In this case, overall income inequality may not be that important for life satisfaction inequality, as people do not compare their income with incomes at the national level. The reason for the gap between a person’s own income and their reference income causing concern is related to issues of envy and to greater work satisfaction, which in capitalist economies is often associated with high incomes (Van Praag 2011; Scitovsky 1973). If, for example, one has a high income in absolute terms, but little compared to his or her reference group, the high income would not lead to a high level of life satisfaction. On the other hand, it also implies that if one has a low income that is higher than the income of one’s reference group, then low income would lead to a high level of life satisfaction.

The empirical evidence on the relationship between income inequality and inequality in life satisfaction is mixed. Ott (2005) found no evidence that income inequality causes an increase in happiness inequality. In contrast to Ott, Ovaska and Takashima (2010) detected a strong and significant positive relationship between income inequality and happiness inequality. Delhey and Kohler (2011) found a similar result, while employing a slightly different measure for happiness inequality than that used by Ott (2005). Finally, using dummy variables for income lower than 60% of the mean income and for income greater than 200%, Becchetti et al. (2013) found that relative poverty has a positive effect on happiness inequality, while the second dummy representing relative affluence has no effect. An important note with respect to the empirical literature is that while Ott only looked at correlations (not at causal relations or regression analysis), Becchetti et al. used simple regression analysis, looking at the change over two time periods, whereas Delhey and Kohler and Ovaska and Takashima performed only a static cross-country analysis.

3 Conceptual Framework

Based on the literature review discussed in Sect. 2, we can conclude that income inequality is likely to increase inequality in life satisfaction and decrease social trust. However, in our paper, we are principally interested in the missing link in the triangle of income inequality—life satisfaction inequality—trust, that is: the relationship between life satisfaction inequality and trust. In this section, we first describe this relationship. Next, we present the hypotheses and the model. Lastly, we discuss the mediating role of life satisfaction inequality in the relationship between income inequality and trust.

3.1 Life Satisfaction Inequality and Trust

Whereas there is a substantial amount of research into the relationship between income inequality and trust (see Sect. 2.1) and average life satisfaction and trust (Helliwell 2003, 2006; Bjørnskov et al. 2007, 2010; Oishi et al. 2011; Graafland and Compen 2015), there is no literature that presents empirical research on the influence of inequality in life satisfaction on social trust. But based on social cognition literature, some conjectures can be made.

Schneider (2012) has shown public perceptions to be important to the significance of income inequality. She has argued that individuals may not be affected by income inequality at the contextual level (i.e. as a concept or philosophical idea of fairness), but by ‘their personal experiences within their immediate environment’ (i.e. the displeasure over the fact that they earn less income for the same amount of work than their neighbor, or the loss in status associated with that). Whether income inequality makes people more happy or less happy depends on how they perceive that inequality within their personal social context and social cognition (Howard 1994; Fiske and Taylor 1984). This in turn shapes their perception of society and of other people’s behavior. Schneider mentioned two ways in which inequality is evaluated by individuals, which are (the fairness of) distributional outcomes and distributional procedures (also Wegener 1999). The first is referred to as the degree of preference for equality, while the second is referred to as the degree of preference for social mobility. Schneider concluded that theoretically, individuals with little education and limited control over their resources are likely to perceive social mobility to be impossible, and therefore tend to be more strongly affected by income inequality in a negative way. It would then be this negative perception and the resulting dissatisfaction that would lead to other negative outcomes, such as a lack of trust. But if income inequality is considered to represent high potential for social mobility, it could have a negative rather than a positive effect on life satisfaction inequality, as even people with low income would perceive high inequality as an opportunity to improve their situation later in life. Hence, based on her empirical analysis, Schneider concluded that it is the perception of the level of legitimacy of income inequality, related to both ways of evaluation, that affects subjective well-being, rather than the level of income inequality as such (although one affects the other). Based on this argument, inequality in life satisfaction is expected to be more closely correlated with social trust than income inequality, as the influence of the latter is contingent on the social cognition.

Using discontent theories and expected utility theories, Guimaraes and Sheedy (2012) have also linked happiness inequality to social unrest. The idea put forward by Guimaraes and Sheedy is that power differences generate happiness inequality. Because of the lack of freedom and the frustration this generates among the oppressed, they harbor distrust and contempt for the powerful and are likely to support rebellion. The lack of happiness provides a strong ground for social upheaval. Individuals rebel only if they feel miserable and perceive that things cannot get any worse for them (Caruso and Schneider 2011). Whether violence breaks out therefore depends on the level of dissatisfaction and moral frustration. This also lowers trust among the powerful, and destabilizes a country. Thus, higher life satisfaction inequality supposedly has a strong impact on trust across all classes. The higher the inequality in life satisfaction, the higher the level of dissatisfaction among the least advantaged and the lower social trust will be.

Based on these arguments from social cognition theory and discontent theories and expected utility theories, we conjecture that inequality in life satisfaction increases social distrust.

3.2 Model

From the preceding findings and arguments discussed in Sects. 2 and 3.1 we propose a set of three interrelated hypotheses regarding the relationships between income inequality, life satisfaction inequality and trust:

H1

Income inequality decreases social trust

H2

Income inequality increases life satisfaction inequality

H3

Life satisfaction inequality decreases social trust

Whereas hypothesis 1 and hypothesis 2 can be derived from previous literature, it is the combination with hypothesis 3 that creates a new conceptual framework for studying the relationship between income inequality and trust. This framework is reflected in Fig. 1.

In mathematical form, the model can be formulated as:

Xi denotes control variables in the equation of trust and Zj control variables in the equation of life satisfaction inequality (see below).

3.3 Life satisfaction inequality as mediator in the relation between income inequality and trust

The framework summarized in Fig. 1 can be interpreted as a mediation model. A mediation model is a model that seeks to identify and explain the mechanism or process that underlies an observed relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable via the inclusion of a third hypothetical variable, known as a mediator variable. Mediation analysis thus facilitates a better understanding of the relationship between the independent and dependent variables. Baron and Kenny (1986) state that a given variable may be said to function as a mediator (M) to the extent that it accounts for the relation between the predictor (X) and the criterion (Y). In a formula: X → M → Y.

In the context of our model, X represents income inequality, M life satisfaction inequality, and Y trust. As argued above: whether income inequality makes people less trusting depends on how they perceive it within their personal social context and social cognition. Only if income inequality leads to more inequality in life satisfaction, is it to be expected to have a negative effect on social trust. If income inequality is positively valued by both high and low- income groups, as in the case of preference for social mobility, it is to be expected that the negative relationship between income inequality and social trust breaks down. But if the preference for equality dominates, income inequality will increase inequality in life satisfaction and be a source of social tension and distrust. In this paper, we therefore conjecture that inequality in life satisfaction mediates the impact of income inequality and trust. This leads to the following mediating hypothesis:

H4

Life satisfaction inequality mediates the negative effect of income inequality on trust

In our model, trust may therefore not only be directly but also indirectly related to income inequality. In Fig. 1, α1 represents the direct effect of income inequality on trust that is not mediated through life satisfaction inequality. α2β1 represents the indirect or mediation effect and has been termed the product of coefficients. (Preacher and Hayes 2008). The product of α2 and β1 is, in essence, the amount of variance in trust that is accounted for by the income inequality through the mediation mechanism of life satisfaction inequality. The total effect of income inequality on trust is equal to the sum of the direct and the indirect effects. The indirect effect thus reinforces the direct effect of income inequality on trust.

Zhao et al. (2010) state that, for mediation to be empirically confirmed, α2β1 should be significant. If α2β1 and α1 are both significant and share the same sign, this is called complementary mediation. If α2β1 and α1 are both significant but have different directions, there is so-called competitive mediation.

4 Methodology and Data

4.1 Sample and Data Sources

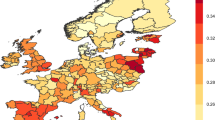

For reasons of comparability and availability of data, we created a sample of 25 countries that are all members of the OECD. The countries included in the regression analysis are reported in Table 1.

Most data in our model cover the period of 1990–2014, while the number of observations per country varies from 1 to 5 for trust, and from 9 to 18 for income and life satisfaction inequality. As shown in Table 2, the dataset used in the empirical analysis has been constructed from different sources.

The data for income inequality are taken from Solt’s Standardized World Income Inequality Database, and refer to the net Gini coefficient (after taxes) (Solt 2016).

The data for life satisfaction inequality (LSI) were taken from Veenhoven’s World Database of life satisfaction. Our indicator for life satisfaction inequality consists of the normal standard deviation of average life satisfaction per country.Footnote 1 Life satisfaction is based on the self-rating of individuals answering the question “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life” and is measured on a four point scale.

For social trust, we used two different measurements. First, we used the well-known trust data of the World Value Studies (WVS) and European Value Studies (EVS). These data reflect self-rated responses to the question “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you need to be careful in dealing with people.” People could respond “most people can be trusted” or “need to be very careful.” The scales in WVS and EVS express the share of respondents that selected the option that “most people can be trusted.”Footnote 2 In addition, we used data for trust from the Social Indicators database of the Institute of Social Studies of Erasmus University Rotterdam (ISS). This indicator consists of a harmonized measure of trust based on various statistical reports such as social trust (similar to the WVS indicator) and perceptions of safety, combined with a number of crime statistics. These include statistics for various types of theft, assault, and homicide. Thus, it provides a measure of trust that is more objective than the trust indicator of World Value Studies, as it does not only rely on people’s perceptions, which are prone to cultural biases, but also on simple indicators of the strength of communities. This allows us to not only analyze whether income inequality and life satisfaction inequality affect the perception of trust, but also whether they affect the actual strength of the bonds between members of societies. Since there is some debate in literature as to whether measures of perceived trust are suitable for economic analysis, due to cultural characteristics that might affect comparability (Bjørnskov 2005; Leigh 2006), we prefer to use both perceived trust and this more objective alternative. If we find support for the hypotheses for both types of datasets, we believe this makes our analysis stronger, as it shows that our conclusions do not depend on subjective indicators alone.

While we used inequality of income and life satisfaction, we used average (or levels of) trust, in accordance with the literature. The main theoretical reason is that levels of trust, across the whole range of the population of a society, are more important in maintaining a functioning nation. Low trust, among one group or within the broader population, becomes problematic when it starts to affect even the most trusting segment of the population, and this is reflected in low levels of average trust. However, it would be interesting to study this in more detail and distinguish between in-group trust and out-group trust for example. Unfortunately, data availability makes this impossible.

4.2 Control Variables

In our analysis, we controlled for a number of different variables. First, we controlled for the logarithm of GDP per capita. GDP per capita has been shown to affect trust (Barone and Mocetti 2016; Dolan et al. 2008; Frey and Stutzer 2002; Stevenson and Wolfers 2008; Fischer 2008). Furthermore, it is likely that GDP also affects the inequality in life satisfaction. The law of diminishing marginal utility of income implies that, given a certain level of income inequality, a rise in the average level of income per capita will reduce inequality in happiness. The reason is that it will lift many people out of poverty and put them in a situation of comparable life satisfaction, while the impact on life satisfaction of people with higher incomes will be limited. As Gropper et al. (2011) argued, other potential control variables (for example, life expectancy, skill level, and other indicators) are highly correlated with GDP per capita. Thus, GDP per capita is likely to capture most of the variation associated with any omitted variable.

Based on previous literature, we added several other control variables. First, we controlled for the ratio between men and women for trust as a cultural characteristic (Leigh 2006). Furthermore, the unemployment rate may affect inequality in life satisfaction and trust (Ovaska and Takashima 2010; Steijn and Lancee 2011; Barone and Mocetti 2016). As institutional variables, we include religion (Christianity and Islam) (Steijn and Lancee 2011), political rights, civil liberty, and monarchy. Monarchies are deemed to be more trusting, having a more stable political system and less need for full democratic accountability (Bergh and Bjørnskov 2014; Bjørnskov 2005; Bjørnskov et al. 2007; Robbins 2012). As demographic variables, we include the share of population aged 65 and above, the population dependency ratio and infant mortality ratio (Bjørnskov et al. 2008; Ovaska and Takashima 2010; Barone and Mocetti 2016). Finally, in the regression analysis of trust we include the share of exports over GDP (Barone and Mocetti 2016) and the urbanization rate (Bennett and Nikolaev 2014) as additional controls.Footnote 3

4.3 Estimation Method and Causality

Before performing regression analysis using panel data, one must test whether there are random or fixed effects in the data. Fixed effects are generally used to control for unobserved heterogeneity when heterogeneity is constant over time. Random effects models are more appropriate when it is expected that differences across entities (or countries) influence the dependent variable. To determine which model is correct, we performed the Hausman test. This tests whether the residuals are correlated with the independent variables. If the error terms are significantly correlated with the other regressors in the model, the fixed effect model is consistent and the random effects model is inconsistent. If the individual effects are not correlated with the other regressors in the model, both random and fixed effects are consistent and the random effects model is more efficient. As the Hausman tests were not significant, we used the random effects model. Furthermore, since we found some indication of heteroscedasticity in the regressions of trust, we used robust standard errors.

In order to control for correlation between the residuals for life satisfaction inequality and social trust, we use the CMP (“conditional mixed process”) estimator with robust standard errors to test the hypotheses. CMP fits a large family of multi-level and seemingly unrelated systems. Random effects at a given level are allowed by default to be correlated across equations. The method is conditional, meaning that the model can vary by observation. This is a great advantage for our model, since we have many more observations for estimating the equation for life satisfaction inequality than for the equation of social trust. In short, it is an estimation method that accommodates differences in the number of observations per country and per variable, while allowing for complex relations and a flexible model definition.

In the interpretation of the results of the regression analysis, we should be aware of the possibility of a simultaneity bias because of inverse causality from dependent on independent variables. As Bergh and Bjørnskov (2011) showed, countries with higher trust levels are more prone to have larger welfare states, thereby reducing inequality. This suggests that higher trust might have a negative reverse effect on income inequality. However, as discussed above, research by Barone and Mocetti (2016) using instrumental variables showed that there is a negative causal effect of income inequality on trust. Furthermore, it can be noted that reverse effects would materialize with long lags, as institutional changes take a long time to accomplish. The shorter the time period in which the negative effect of income inequality on trust becomes manifest, the more likely it is that the estimated relationship stems from the causal effect of income inequality on trust as predicted by hypothesis 1.

Furthermore, Guimaraes and Sheedy (2012) have argued that redistribution is a common tool used to quash the risk of rebellion that springs from high inequality in life satisfaction. This suggests there is also a theoretical possibility that high life satisfaction inequality has a negative reverse impact on income inequality. However, inequality in life satisfaction may also have a positive reverse effect on income inequality because people that are happier may be more inclined to work harder, or be more creative and entrepreneurial, and earn a higher income (Frey and Stutzer 2002). If these positive and negative reverse effects cancel out, our estimation results will be unbiased. Unfortunately, proof can only be given if we can disentangle the causal relations predicted by our conceptual framework from possible other, reverse, causal effects, by using instrumental variables. But we lack data for such instrumental variables. Also, Ott (2005), Becchetti et al. (2013), Delhey and Kohler (2011) and Ovaska and Takashima (2010) do not test causality in their estimation of the relationship between income inequality and life satisfaction inequality. Therefore, we should interpret the results of our empirical analysis with care. However, as the reverse effect of life satisfaction inequality on income inequality can be positive as well as negative, it is a priori likely to be rather small. That means that if we find a strong positive effect from income inequality on life satisfaction inequality, the posterior probability that this empirical relationship reflects the causal impact predicted by our model is relatively high.

5 Results

This section presents the results of the empirical analysis, starting with the correlation analysis of dependent and independent variables. Next, we will present the panel regression analysis.

5.1 Bivariate Correlation Analysis

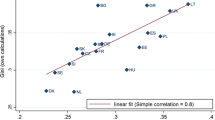

Table 3 reports the Pearson correlation coefficients. Trust is negatively correlated with life satisfaction inequality and the net Gini coefficient. Furthermore, the indicators for life satisfaction inequality (LSI) and net income inequality are positively correlated, as are also the two indicators for trust.

5.2 Panel Regression Analysis

In this section we present the results of panel regression analysis for life satisfaction inequality and trust. The estimation results are reported in Table 4.

We experimented with several different lag structures, varying from unlagged to 3 years lagged influences of income inequality on life satisfaction inequality, and of both inequality variables on social trust. The results did not differ very much, but the use of a lag of 1 year provided the best fit.Footnote 4 Therefore, we employed 1-year lagged variables in both regression equations. This relatively short period provides indications that our estimation results express a causal impact of income inequality on trust and life satisfaction inequality, instead of a reverse effect of trust and life satisfaction inequality on income inequality.

Columns 1 and 3 of Table 4 show that income inequality has a large and highly significant effect on life satisfaction inequality (LSI).Footnote 5 As argued above, the large effect makes it likely that the results express a causal influence of income inequality on life satisfaction inequality. Thus we find support for hypothesis 2. We also find a positive effect of the unemployment rate, female population rate, religion, and civil liberty. We find a negative impact of the share of aged population and the monarchy dummy.

Columns 2 and 4 report the estimation results for trust. For both measurements of trust, we find that income inequality has a significant negative effect on trust, which provides support for hypothesis 1. But we also detect an additional negative effect of life satisfaction inequality on trust, which supports hypothesis 3.Footnote 6 Furthermore, we find some indications that religion, political rights, civil liberty, the age structure, and exports affect trust.

5.3 Test on Mediation

In order to test hypothesis 4, whether life satisfaction inequality significantly mediates the effect of income inequality on trust, we used the Sobel test. The Sobel test uses the magnitude of the product of α2 and β1 (see Fig. 1) compared to its estimated standard error of measurement to determine the significance of the mediation effect. The β1 term represents the magnitude of the relationship between the independent variable (income inequality) and the mediator (life satisfaction inequality). The α2 term represents the magnitude of the relationship between the mediator (life satisfaction inequality) and dependent variable (social trust) after controlling for the effect of the independent variable.

The results are reported in Table 5. The first row reports the direct effect of income inequality on trust (see also Table 4). The second row presents the indirect effect through mediation by life satisfaction inequality. The third row shows the significance of the mediation effect by reporting the P value of the Sobel test. For both types of measurement of trust, the Sobel test shows that the mediation effect is significant.

The total effect of income inequality on trust is equal to the sum of the direct and indirect effects and is reported in the fourth row. The last row shows the percentage of the total effect of income inequality on trust caused by mediation by life satisfaction inequality. We see that the mediation effect constitutes a relatively small part of the total effect of income inequality on trust. The direct effect of income inequality on trust accounts for the greater part of its total impact. Finally, as we find that the sign of the direct and indirect effects are both positive, our results point at so-called complementary mediation (Zhao et al., 2010).

6 Conclusions

In this article, we have investigated the relationship between income inequality, life satisfaction inequality, and trust. We developed four hypotheses that we tested through panel regression analysis.

The main result is that life satisfaction inequality has a significant diminishing effect on trust and should therefore be considered equally with income inequality when it comes to its impact on trust. Life satisfaction equality therefore has not only intrinsic value, as an end in itself for reasons of fairness, but also instrumental value for society by fostering economic growth through increasing trust.

Another important result of our study is that life satisfaction inequality mediates the relationship between income inequality and trust, as income inequality is found to significantly increase life satisfaction inequality. Whereas previous research into the relationship between income inequality and life satisfaction inequality has been based on static cross-country regression or correlation analysis, our analysis provides the first panel analysis of life satisfaction inequality in relation to income inequality and trust. Our mediation analysis provides more detail about the specifics of the relationship between income inequality and trust.

But income inequality also has a direct impact on trust, on top of its indirect effect mediated through inequality in life satisfaction. This confirms the analysis of previous literature on the relationship between income inequality and trust (Leigh 2006; Oishi et al. 2011; Schneider 2012; Hajdu and Hajdu 2014; Barone and Mocetti 2016). A possible reason for this finding could be that life satisfaction inequality is less objective and less visible to most people, while they can observe and relate to income inequality. One explanation of this limited visibility is related to cultural norms, which often do not allow one to express feelings of unhappiness. Another explanation is that life satisfaction, being a very personal measure of a mostly psychological nature, depends much more on comparison with close neighbors than on class differences on a national level. Income inequality, on the other hand, is a national and more objective measure that is related to the concept of fairness. Fairness, and the resulting notion of social trust, depends more on one’s position in the broader environment (be it a nation or even the global context) than on one’s close relationships.

These results are a stimulus for further economic research on social trust and the underlying concept of social cohesion. They also underscore the fundamental role of income inequality in our economic system, and the need to address such inequality, whether because of its direct impact on life satisfaction inequality, or because of its impact on trust and social cohesion. As a follow-up to this paper, we therefore suggest research on a better way to define and measure social cohesion, as well as on the relationship of social cohesion to alternative measures of income inequality and wealth inequality.

As for policy implications, our research indicates first of all that income inequality affects trust in different ways. Its direct effect is negative, suggesting that policies aiming to increase trust should decrease income inequality. In practical terms, these results imply that policy reforms consisting of tax cuts and subsidies mostly benefitting the wealthy are not to be recommended.

In addition, our results imply that policy options for increasing trust are not limited to countering income inequality. If there are other ways of influencing life satisfaction inequality directly that do not focus on income inequality, they will also be beneficial to trust. First, policies targeting unemployment among low skilled workers, for example by earned income tax credits, will increase life satisfaction among poor people, thereby reducing the inequality in life satisfaction and increasing trust. Also, policies that provide health care access to low-income families will raise the level of life satisfaction for them and provide them with more opportunities to participate fully in society, thereby reducing the frustration and disconnectedness of these population groups. Health is one of the most important variables explaining subjective well-being, and the life satisfaction of unhealthy people is much more affected by these policies than that of the healthy. Third, policies should foster civil liberties, which include freedom of expression and belief but also freedom of association and the rule of law. This is especially important with respect to lower income classes to protect them against abuse by the economically and politically powerful, as well as allowing them to mitigate their own vulnerability by speaking out and by organizing themselves. Political parties should take care that they do not alienate themselves from those parts of the population that face hardship and have little opportunity to improve their personal lives. The voices of the disadvantaged groups in society should be heard. This will increase their participation in elections and increase their self-esteem. Finally, educational policies targeting children from low income, disadvantaged groups will have substantial long-term effects on life satisfaction inequality, by providing these children with a better starting point in life.

Notes

Source: R. Veenhoven, World Database of Happiness, collection happiness in nation, Overview of happiness surveys using Measure type 121C/4-step verbal Life Satisfaction. Viewed on 2-12-2016 at http://worlddatabaseofhappiness.eur.nl.

As the number of observations became very small after matching the WVS and EVS data for perceived social trust with data for income inequality and life satisfaction inequality, we obtained data for missing years via interpolation. We applied interpolation by taking the average of the closest years surrounding the missing year. 22 out of 78 observations in the regression model reported in column 2 of Table 4 are based on interpolation. For the method of interpolation, see “Appendix 1”. For the more objective measure of social trust measured by ISS, interpolation was unnecessary.

Barone and Mocetti (2016) also include the immigration rate and level of schooling as controls. However, data availability for these variables is very limited. Therefore, we did not include them in our regression analysis.

If we include year dummies in order to capture a trend in trust and inequality, the significance of the results does not change.

The estimation results for the equation for life satisfaction inequality (LSI) in columns 1 and 3 are based on the same data sample. The only difference is that in column 1, the equation for LSI is estimated simultaneously with the equation of perceived social trust, whereas in column 3 it is estimated simultaneously with the equation for objective social trust. Table 4 shows that the coefficients for the LSI equation hardly differ in column 1 and column 3. The small changes are due to differences in the estimated standard errors, as the correlations between the residuals of LSI and social trust depend on the set of equations that are simultaneously estimated (life satisfaction inequality and perceived trust in model 1, and life satisfaction and objective social trust in model 2, respectively).

If we run model I without the interpolated observations, the effects of income inequality on both life satisfaction inequality and trust remain significant. The estimated coefficient of life satisfaction inequality in the trust equation slightly decreases from 0.34 to 0.29 and becomes insignificant, due to the low number of observations.

References

Alpizar, F., Carlsson, F., & Johansson-Stenman, O. (2005). How much do we care about absolute versus relative income and consumption? Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 56(3), 405–421.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical consideration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Barone, G., & Mocetti, S. (2016). Inequality and trust: New evidence from panel data. Economic Inquiry, 54(2), 794–809.

Bastagli, F., Coady, D., & Gupta, S. (2012). Income inequality and fiscal policy. IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN/12/08.

Becchetti, L., Massari, R., & Naticchioni, P. (2013). The drivers of happiness inequality: Suggestions for promoting social cohesion. Oxford Economic Papers, 66(2), 419–442.

Bennett, D. & Nikolaev, B. (2014). On the ambiguous economic freedom-inequality relationship. SSRN 2467222.

Berg, A., & Ostry, J. (2011). Inequality and unsustainable growth: Two sides of the same coin? IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN/11/08.

Berg, M., & Veenhoven, R. (2010). Income inequality and happiness in 119 nations. In B. Greve (Ed.), Social policy and happiness in Europe (chap. 11, pp. 174–194). Cheltenham: E. Elgar.

Berggren, N., & Jordahl, H. (2006). Free to trust: Economic freedom and social capital. Kyklos, 59(2), 141–169.

Bergh, A., & Bjørnskov, C. (2011). Historical trust levels predict the current size of the welfare state. Kyklos, 64, 1–19.

Bergh, A., & Bjørnskov, C. (2014). Trust, welfare states and income equality: Sorting out the causality. European Journal of Political Economy, 35, 183–199.

Bjørnskov, C. (2005). The determinants of trust. Working Paper, Department of Economics, Aarhus School of Business. http://ssrn.com/abstract=900183.

Bjørnskov, C., Dreher, A., & Fischer, J. A. V. (2007). The bigger the better? Evidence of the effect of government size on life satisfaction around the world. Public Choice, 130, 267–292.

Bjørnskov, C., Dreher, A., & Fischer, J. (2008). Cross-country determinants of life satisfaction: Exploring different determinants across groups in society. Social Choice and Welfare, 30(1), 119–173.

Bjørnskov, C., Dreher, A., & Fischer, J. A. V. (2010). Formal institutions and subjective well-being: Revisiting the cross-country evidence. European Journal of Political Economy, 26, 419–430.

Brekke, K. A., & Howarth, R. B. (2002). Status, growth and the environment: goods as symbols in applied welfare economics. Cheltenham: E. Elgar.

Carlsson, F., Johansson-Stenman, O. L. O. F., & Martinsson, P. (2007). Do you enjoy having more than others? Survey evidence of positional goods. Economica, 74(296), 586–598.

Caruso, R., & Schneider, F. (2011). The socio-economic determinants of terrorism and political violence in Western Europe (1994–2007). European Journal of Political Economy, 27, S37–S49.

Chin-Hon-Foei, S. (1989). Life satisfaction in the EC countries, 1975–1984. In R. Veenhoven (Ed.), Did the crisis really hurt? Effects of the 1980–82 economic recession on satisfaction, mental health and mortality (pp. 24–43). Rotterdam: Universitaire Pers Rotterdam.

Clark, A. E., & Oswald, A. J. (1996). Satisfaction and comparison income. Journal of Public Economics, 61(3), 359–381.

Clark, A. & Senik, C. (2011). Will GDP growth increase happiness in developing countries? IZA Discussion Paper No. 5595.

Deaton, A. (2008). Height, health, and inequality: The distribution of adult heights in India. The American Economic Review, 98(2), 468.

Delhey, J., & Kohler, U. (2011). Is happiness inequality immune to income inequality? New evidence through instrument-effect-corrected standard deviations. Social Science Research, 40(3), 742–756.

Dolan, P., Peasgood, T., & White, M. (2008). Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29, 94–122.

Easterlin, R. A. & Angelescu, L. (2009). Happiness and growth the world over: Time series evidence on the happiness-income paradox. IZA Discussion Paper No. 4060.

Elgar, F., & Aitken, N. (2011). Income inequality, trust and homicide in 33 countries. European Journal of Public Health, 21(2), 241–246. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckq068.

Fischer, C. S. (2008). What wealth-happiness paradox? A short note on the American case. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 219–226.

Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (1984). Social cognition. New York, NY: Random House.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). What can economists learn from happiness research? Journal of Economic Literature, 40, 402–435.

Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The social virtues and the creation of prosperity. New York: Free Press.

Gandelman, N., & Porzecanski, R. (2013). Happiness inequality: How much is reasonable? Social Indicators Research, 110(1), 257–269.

Graafland, J., & Compen, B. (2015). Economic freedom and life satisfaction: Mediation by income per capita and generalized trust. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(3), 789–810.

Gropper, D. M., Lawson, R. A., & Thorne, J. T., Jr. (2011). Economic freedom and happiness. Cato Journal, 31, 237–255.

Guimaraes, B. & Sheedy, K. D. (2012). A model of equilibrium institutions. CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP8855.

Hagerty, M. R., & Veenhoven, R. (2003). Wealth and happiness revisited- growing national income does go with greater happiness. Social Indicators Research, 64(1), 1–27.

Hajdu, T., & Hajdu, G. (2014). Reduction of income inequality and subjective well-being in Europe. Economics: The Open-Access, Open Assessment E-Journal, 8, 2014–2035.

Helliwell, J. F. (2003). How’s life? Combining individual and national variables to explain subjective well-being. Economic Modelling, 20, 331–360.

Helliwell, J. F. (2006). Well-being, social capital and public policy: What’s new? The Economic Journal, 116, C34–C45.

Helliwell, J. F., & Putnam, R. D. (2004). The social context of well-being. Philosophical Transactions-Royal Society of London series B Biological Sciences, 359, 1435–1446.

Howard, J. A. (1994). A social cognitive conception of social structure. Social Psychology Quarterly, 57(3), 210–227.

Inglehart, R., Foa, R., Peterson, C., & Welzel, C. (2008). Development, freedom, and rising happiness: A global perspective (1981–2007). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(4), 264–285.

Kalmijn, W., & Veenhoven, R. (2005). Measuring inequality of happiness in nations: In search for proper statistics. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6(4), 357–396.

Kawachi, I., & Kennedy, B. P. (1997). Health and social cohesion: Why care about income inequality? BMJ. British Medical Journal, 314(7086), 1037.

Knack, S., & Keefer, P. (1997). Does social capital have an economic pay-off? A cross-country investigation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112(4), 1251–1288.

Layard, R. (2010). Measuring subjective well-being. Science, 327(5965), 534–535.

Leigh, A. (2006). Trust, inequality and ethnic heterogeneity. Economic Record, 82(258), 268–280.

OECD. (2012). Reducing income inequality while boosting economic growth: Can it be done? Economic Policy Reforms 2012: Going for growth. OECD.

Oishi, S., Kesebir, S., & Diener, E. (2011). Income inequality and happiness. Psychological Science, 22(9), 1095–1100.

Oshio, T., & Kobayashi, M. (2010). Income inequality, perceived happiness, and self-rated health: Evidence from nationwide surveys in Japan. Social Science and Medicine, 70, 1358–1366.

Ostry, J., Berg, A., & Tsangarides, C. (2014). Redistribution, inequality, and growth. IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN/14/02.

Ott, J. (2005). Level and inequality of happiness in nations: Does greater happiness of a greater number imply greater inequality in happiness? Journal of Happiness Studies, 6(4), 397–420.

Ovaska, T., & Takashima, R. (2010). Does a rising tide lift all the boats? Explaining the national inequality of happiness. Journal of Economic Issues, 44(1), 205–224.

Piazza, J. A. (2011). Poverty, minority economic discrimination, and domestic terrorism. Journal of Peace Research, 48(3), 339–353.

Piketty, T. (2014). Capital in the 21st Century. London: Beldknap/Harvard.

Piketty, T., & Saez, E. (2013). Top incomes and the Great recession: Recent evolutions and policy implications. IMF Economic Review, 61(3), 456–478.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891.

Rahn, W. M., & Transue, J. E. (1998). Social trust and value change: The decline of social capital in American youth, 1976–1995. Political Psychology, 19(3), 545–563.

Robbins, B. G. (2012). A blessing and a curse? Political institutions in the growth and decay of generalized trust: A cross-national panel analysis, 1980–2009. Public Library of Science one, 7(4), e35120.

Schneider, S. (2012). Income inequality and its consequences for life satisfaction: What role do social cognitions play? Social Indicators Research, 106, 419–438.

Scitovsky, T. (1973). Inequalities: Open and hidden, measured and immeasurable. Annals of American Academy of Political and Social Science (AAPSS), 409, 112–119.

Smith, A. (1776). An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. London: George Routledge and Sons.

Solnick, S. J., & Hemenway, D. (1998). Is more always better?: A survey on positional concerns. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 37(3), 373–383.

Solt, F. (2016). The standardized world income inequality database. Social Science Quarterly 97. SWIID Version 5.1, July 2016.

Steijn, S. & Lancee, B. (2011). Does income inequality negatively affect general trust? Examining three potential problems with the inequality/trust hypothesis. Gini Discussion Papers.

Stevenson, B. & Wolfers, J. (2008). Economic growth and subjective well-being: Reassessing the Easterlin paradox. National Bureau of Economic Research, Working paper no. w14282.

Van Praag, B. (2011). Well-being inequality and reference groups: An agenda for new research. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 9(1), 111–127.

Veenhoven, R. (1990). Inequality in happiness: Inequality in countries compared between countries. In 12th world congress of sociology.

Veenhoven, R. (1995). The cross-national pattern of happiness: Test of predictions implied in three theories of happiness. Social Indicators Research, 34(3), 33–68.

Veenhoven, R. (2000). Freedom and happiness. In E. Diener & E. M. Suh (Eds.), Culture and subjective wellbeing (pp. 257–288). Boston: MIT Press.

Veenhoven, R. (2002). Die Rückkehr der Ungleichheit in die modern Gesellschaft? Die Verteilung der Lebenszufriedenheit in den EU-Ländern von 1973 bis 1996. In W. Glatzer, R. Habich & K.-U. Maier, pp. 273–294.

Verme, P. (2011). Life satisfaction and income inequality. Review of Income and Wealth, 57(1), 111–137.

Wegener, B. (1999). Belohnungs- und Prinzipiengerechtigkeit: Die zwei Weltern der empirischen Gerechtigkeitsforschung. In U. Druwe & V. Kunz (Eds.), Politische Gerechtigkeit (pp. 167–214). Opladen: Leske and Budrich.

Wilkinson, R., & Pickett, K. (2010). The spirit level: Why equality is better for everyone. London: Penguin Books.

Zagorski, K., Evans, M., Kelley, J., & Piotrowska, K. (2014). Does national income inequality affect individuals’ quality of life in Europe? Inequality, happiness, finances, and health. Social Indicators Research, 117, 1089–1110.

Zak, P. J., & Knack, S. (2001). Trust and growth. The Economic Journal, 111, 295–321.

Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G., Jr., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny”Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(August), 197–206.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Templeton World Charity Foundation, Inc. The authors thank two reviewers for their comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix 1 Interpolation of Perceived Social Trust

Appendix 1 Interpolation of Perceived Social Trust

Column 2 in Table 6 presents the number of observations of perceived social trust per country that match with observations of other variables. Column 3 reports the other years for which observations for perceived social trust are available and column 4 the years for which we used interpolation. The interpolated values for 1995 were calculated as the average of the values in 1990 and 2000, for 2005 we used the average of 2000 and 2010. Since we did not observe much volatility in trust over time from 1990 to 2010, we assume that our estimates are sufficiently reliable to be used in our analysis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Graafland, J., Lous, B. Income Inequality, Life Satisfaction Inequality and Trust: A Cross Country Panel Analysis. J Happiness Stud 20, 1717–1737 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0021-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0021-0