Abstract

Community health workers (CHWs) are frontline public health workers who bridge the gap between historically marginalized communities, healthcare, and social services. Increasingly, states are developing the CHW workforce by implementing training and certification policies. Health departments (HDs) are primarily responsible for community health through policy implementation and provision of public health services. The two objectives of this study are to explore: (1) state progress in establishing CHW training and certification policies, and (2) integration of CHWs in HD workforces. In this scoping review, we searched PubMed, CINAHL, and Google Scholar for articles published between 2012 and 2022. We looked for articles that discussed state-level certification and training for CHWs and those covering CHWs working with and for city, county, state, and federal HDs. We excluded studies set outside of the US or published in a language other than English. Twenty-nine studies were included for review, documenting CHWs working at all levels of HDs. Within the included studies, HDs often partner with organizations that employ CHWs. With HD-sponsored programs, CHWs increased preventative care, decreased healthcare costs, and decreased disease risk in their communities. Almost all states have begun developing CHW training and certification policies and are at various points in the implementation. HD-sponsored CHW programs improved the health of marginalized communities, whether CHWs were employed directly by HDs or by a partner organization. The success of HD-sponsored CHW programs and state efforts around CHW training and certification should encourage increased investment in CHW workforce development within public health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

As trusted members of the communities they serve, community health workers (CHWs) are valuable assets to the healthcare, social service, and public health workforce. CHWs bridge the gap, serving as connectors between their communities, the healthcare system, and social services, particularly in historically marginalized and/or underserved populations. CHW-led interventions have been shown to reduce healthcare utilization, lower the risk of cardiovascular disease, promote cancer screening, and improve diabetes outcomes, among other benefits [1,2,3]. CHWs help community members navigate health care and other systems, and address health-related social needs by referring community members to resources for food, transportation, housing, and other social services [4, 5].

CHWs work in a variety of organizations, with over 80% employed by non-profit organizations, community clinics, or hospitals [6]. Fewer than 10% of CHWs work for health departments [6]. Health departments, as governmental agencies, coordinate and provide a range of public health services at local, state, and federal levels. Their services span domains such as communicable diseases, environmental health, immunizations, and community outreach. Health departments are also heavily involved in training and certifying public health professionals, including CHWs, although their involvement varies state to state. While the overall mission of most health departments is to improve community health, in recent years, an increasing number of health departments, from the federal level down, are also focusing on racial health inequities [7].

The number of CHWs working within, or in partnership with, health departments has increased dramatically in recent years. The acceleration of state policies for certification and reimbursement of CHWs has been a major driving factor. In addition, since 2020, health departments have employed more CHWs as part of their COVID-19 pandemic response efforts [8]. For instance, the Illinois Department of Public Health used pandemic relief funds from the federal government to establish the Pandemic Health Navigator Program, a workforce of over 650 CHWs [8]. With the end of the public health emergency, it is important to understand how CHWs are integrated more broadly into the work of health departments. To this end, the current study explores how health departments in the United States: (1) support the CHW workforce through CHW training and certification policies, and (2) integrate CHWs into their workforce.

Methods

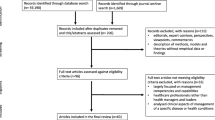

In this review, we used a scoping review methodology to assess the scope of CHW research as it relates to health departments, drawing from both peer-reviewed literature and gray literature. From July 2022 to December 2022, we searched PubMed, CINAHL, and Google Scholar for peer-reviewed literature published between 2012 and 2022. We included articles that discussed CHWs along with health departments at any level, including city, county, state, and federal. Our search strings included combinations of the following terms: “community health worker”, “[state name]”, “health department” OR “department”, “training”, and “certification”. We excluded articles that were set outside of the United States, were published in a language other than English, or did not mention health departments. After screening abstracts and full text, we compiled key characteristics from each study into a standardized table, including elements such as study design, CHW program interventions, and quantitative and qualitative outcomes. We also searched gray literature for news articles and press releases about the role of CHWs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results

Twenty-nine studies were selected for inclusion in this review. Table 1 reflects “health department sponsored programs” which includes programs where CHWs are employed by the health department, and programs where CHWs are employed by another organization but collaborate with a health department. Table 2 reflects studies related to CHW training and certification. The earliest studies were published in 2013, and 14 of the studies were published in 2020 or later. Twelve studies focused on CHW training and certification, while the remaining 17 studies focused on CHW programs associated with health departments. Study designs varied from case studies to randomized controlled trials, and study results included both quantitative and qualitative data.

Statewide CHW Workforce Development

Barbero et al. developed a model to assess progress in developing CHW initiatives in all 50 states [9]. They identified 12 strategies being used to support CHW initiatives, such as involving CHWs in statewide health systems and supporting statewide CHW organizations. On average, states have addressed eight of the 12 strategies in their initiatives. Over 46 states are investing in initiatives, establishing statewide standards and policies, and developing statewide training and development opportunities for CHWs.

As of 2021, 45 states had a multi-stakeholder CHW coalition and 31 had a statewide CHW organization [9]. For example, the Utah Department of Health established a statewide CHW coalition in 2015 focusing on sustainable reimbursement of CHWs, standardized training and certification, and a defined scope of practice for CHWs [10]. The Massachusetts Department of Public Health and Massachusetts Association of Community Health Workers were instrumental in creating CHW certification in that state [11].

Several statewide CHW census surveys have examined state-level CHW demographics and workforce development needs. The proportion of CHWs working under local health departments in each state varies widely, ranging from 9% in Texas to 22% in Florida to 32% in Nebraska [12,13,14].

Most surveys identified certification as a primary workforce development issue [12, 13, 15, 16]. In Louisiana, CHWs and CHW employers agreed that certification would support CHWs in learning new skills, improving job prospects, and expanding the CHW workforce [15]. Certification is not without its concerns, however. Louisiana CHWs and CHW employers were concerned that CHWs may not be able to afford certification, and most Texas CHW employers felt they did not have the capacity to compensate for certified continuing education for their CHWs [12, 15].

Progress in establishing CHW certification standards varies from state to state. Twenty-three states have certification processes in place, whether through health departments or state CHW organizations, while 14 states are in the process of developing certification standards [17]. For example, Texas already has certification processes in place, with 75% of CHW employers requiring their CHWs to be certified by the Texas Department of State Health Services [12]. Oregon is another example of state CHW certification, with standards developed by the Oregon Health Authority Office of Equity and Inclusion and the Multnomah County Health Department [18]. The Rhode Island Department of Health also created standards for certification of CHWs throughout the state [19]. In Arizona, promotoras de salud and community health representatives collaborated to create a voluntary certification legislative effort with support from the Arizona Department of Health Services [20]. Meanwhile, Florida and Louisiana do not have certification processes, but a majority of CHWs there have expressed interest in becoming certified [13, 15].

Other workforce development needs included funding and reimbursement of CHW services and continuing education and training for CHWs [12, 16]. In 2022, 29 out of 48 states surveyed allowed Medicaid payment for CHW services, indicating an opportunity for growth in state-level support of CHWs [21]. State health departments can also support CHW workforce development by helping to integrate CHWs in ambulatory care settings [22].

Health Department-Sponsored CHW Programs

City Health Departments

There are several examples of CHW programs with city health departments. For example, the Detroit Health Department collaborated with a community organization, a university, and Medicaid health plans to create a CHW program in one of Detroit’s low-income neighborhoods [23]. The program contributed to fewer emergency department (ED) visits and lower ED visit costs [23]. In Texas, the City of El Paso Department of Public Health partnered with a university to create a CHW program called Healthy Fit, which aimed to reduce Hispanic health inequities [24, 25]. CHWs screened participants, provided vouchers for health resources, and conducted motivational interviews to further support participants [25]. Healthy Fit ultimately helped increase cancer screenings and immunizations in the community, recruiting over 2500 participants [25].

City health departments also partner with state health departments to provide CHW services. In Virginia, the Richmond City Health District and the Virginia Department of Health implemented satellite clinics staffed by CHWs and public health nurses in low-income public housing [26, 27]. The CHWs provided health screenings and referrals to other community resources, such as employment assistance.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, some city health departments further expanded their CHW workforce. In September 2021, the New York City (NYC) Department of Health and Mental Hygiene and NYC Health + Hospitals spearheaded the NYC Public Health Corps, which worked to support NYC’s public health workforce and address health inequities exacerbated by the pandemic [28]. The NYC Public Health Corps trained new CHWs and provided grants for CHWs to serve the communities most adversely affected during the pandemic. The CHWs not only provided COVID-19 preventative care, vaccinations, and treatment, but they also addressed communities’ social needs such as food and housing [28].

County Health Departments

There are fewer examples of CHW programs under county health departments. In Minnesota, the Hennepin County Human Services and Public Health Department and community organizations contracted with the Minnesota Department of Human Services to create an accountable care organization (ACO) [29]. The CHWs at participating clinics coordinated social services for low-income residents, and preliminary results showed the ACO decreased the rate of ED and inpatient admissions in Hennepin County [29]. Another study showed that CHWs employed by Arizona county health departments and clinics were associated with a positive impact on the emotional well-being of Latino/Latina participants, including improved social support, hopefulness, and quality of life [30].

State Health Departments

Most CHW programs associated with health departments were found at the state level. Many state health department sponsored CHW programs have successfully improved health outcomes, such as decreasing rates of low birth weights among minority women in Arizona, improving diet and exercise among women in Utah, and reducing the risk of coronary heart disease in counties in Colorado [31,32,33]. CHWs employed by state health departments have also made positive impacts on preventative care, such as in Louisiana, where CHWs helped 40% of their referred clients complete sexually transmitted infection testing and receive health education materials [34].

Additionally, state health department sponsored CHW programs have shown economic benefits. The Delaware Public Health Department partnered with Nemours Children’s Health System to promote advancement of CHWs in a collaboration between community-based prevention efforts and clinical care for children with asthma [35]. Preliminary data suggested that ED visits decreased by 60% from 2012 to 2014 and healthcare costs for children with asthma decreased compared to children in the control group [35].

Health department sponsored CHW programs are not without their challenges. For instance, the Hawaii Department of Health partnered with federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) and the Hawaii Primary Care Association to create a CHW-led health promotion effort supporting diabetes prevention and hypertension control [36]. In this effort, CHWs were employed by the FQHCs. However, there were barriers in establishing links between the clinical and community settings, and sustainability was impacted by reimbursement [36]. The type of care that CHWs provide varies in effectiveness as well. For instance, in a pilot project for Texas’ Transformation and Quality Improvement Program, the Texas Department of Health and Human Services certified CHWs to work with patients with diabetes [37]. Blood sugar control was more rapid in patients who received in-person care from CHWs compared to patients who participated in telehealth with CHWs [37].

Federal Health Departments

At the national level, Alaskan Community Health Aides/Practitioners (CHA/Ps) operate under a scope of practice defined by the Indian Health Service, which is under the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) [38]. CHA/Ps’ responsibilities include but are not limited to prenatal care and education, emergency deliveries, and general health education for teenagers. Many Alaskan communities are in rural and remote areas, and CHA/Ps are often the only healthcare providers for these communities [38].

HHS also runs a program called Healthy Start, which aims to address inequities in maternal and infant health [39]. To fulfill this mission, the program heavily relies on CHWs. A survey of Healthy Start programs revealed that 91% employed CHWs in some capacity. The CHWs work with women, infants, and their families, providing culturally competent services and addressing social determinants of health [39].

Finally, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) implemented a CHW program in 2002 called the Tribal Veterans Representatives (TVRs) [40]. TVRs, who are often American Indian and Alaska Native veterans themselves, help American Indian and Alaska Native veterans connect with the VA and gain access to its healthcare services by conducting outreach at veterans’ homes and community events. The program has trained over 800 TVRs and has led to multiple advances in veterans’ healthcare access, including the establishment of a primary care clinic and a resource center [40]. As of 2017, the program was still ongoing.

Discussion

Health departments at all levels employ CHWs, from short-term interventions to long-term programs. They often partner with universities and community organizations to develop CHW programs and employ them. Health department involvement ranges widely, from providing only funding to organizations, to directly employing the CHWs involved in the interventions or programs. Many CHW programs focus on communities of color and low-income or rural communities. CHWs under federal health departments, in particular, often serve communities in the most remote areas of the country. Most programs have been successful, with common outcomes including improved health outcomes, lower medical costs, and decreased acute care utilization. Despite the successes of the programs, sustainability is unknown as it is unclear whether such programs continued after study publication.

State health departments have an additional layer of involvement in CHW workforce development through establishing certification and training standards for CHWs. Certification was consistently the biggest need identified by both CHWs and their employers. Some states such as Texas already have certification standards for CHWs, some are in the process of developing certification processes, and others have no certification processes at all. While most CHWs expressed interest in certification, cost was a primary concern, with many CHWs (and their employers) possibly unable to afford the certification process.

This review has several limitations. Our search of the literature likely did not identify every health department with a CHW program. We were only able to find CHW census surveys for a few states and the CHW workforce demographics from these states may not be broadly applicable to others. Furthermore, although there was a variety of study designs among the included articles, eight of the 29 articles were case studies. Further studies with stronger study designs, such as randomized controlled trials, would better support the effectiveness of CHW programs. Finally, information about state level CHW certification and reimbursement policies can change rapidly.

Most of the articles in our review were published before 2020. At the time of this writing, few articles have examined how specific health departments have employed CHWs during the COVID-19 pandemic. CHWs have played a major role in pandemic responses worldwide by raising awareness in their communities, participating in disease surveillance, and providing resources for preventative care [41], In the U.S., CHWs do not regularly respond to infectious disease outbreaks [41]. With the COVID-19 pandemic, however, the role of CHWs expanded dramatically. The White House’s American Rescue Plan invested heavily in the CHW workforce, providing funds for local and national organizations to hire, train, and deploy CHWs [42]. In September 2022, the White House announced that $225 million from the American Rescue Plan would go towards training over 13,000 CHWs, not just to support the U.S. pandemic response but also the public health workforce beyond the pandemic [42]. With the ending of the public health emergency, future studies should examine the impact of CHWs on community health outcomes post-pandemic. Future studies should also examine how CHWs are integrated within the focus of health departments and their scope of practice within governmental public health.

Conclusion

Health departments are becoming increasingly involved in the CHW workforce, from developing CHW interventions and programs to establishing certification processes. Overall, CHW programs under health departments have made progress toward improving the health of marginalized communities. The results should encourage further investment in CHW initiatives and workforce development by governmental public health agencies.

References

Jack, H. E., Arabadjis, S. D., Sun, L., Sullivan, E. E., & Phillips, R. S. (2017). Impact of community health workers on use of healthcare services in the United States: A systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 32(3), 325–344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3922-9

Kim, K., Choi, J. S., Choi, E., Nieman, C. L., Joo, J. H., Lin, F. R., Gitlin, L. N., & Han, H. R. (2016). Effects of community-based health worker interventions to improve chronic disease management and care among vulnerable populations: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 106(4), e3–e28. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302987

Palmas, W., March, D., Darakjy, S., Findley, S. E., Teresi, J., Carrasquillo, O., & Luchsinger, J. A. (2015). Community health worker interventions to improve glycemic control in people with diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of general internal medicine, 30(7), 1004–1012. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3247-0

Washburn, D. J., Callaghan, T., Schmit, C., Thompson, E., Martinez, D., & Lafleur, M. (2022). Community health worker roles and their evolving interprofessional relationships in the United States. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 36(4), 545–551. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2021.1974362

Hartzler, A. L., Tuzzio, L., Hsu, C., & Wagner, E. H. (2018). Roles and functions of community health workers in primary care. Annals of Family Medicine, 16(3), 240–245. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2208

Ingram, M., Reinschmidt, K. M., Schachter, K. A., Davidson, C. L., Sabo, S. J., De Zapien, J. G., & Carvajal, S. C. (2012). Establishing a professional profile of community health workers: Results from a national study of roles, activities and training. Journal of Community Health, 37(2), 529–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-011-9475-2

American Public Health Association. (2021). Analysis: Declarations of racism as a public health crisis. American Public Health Association. https://www.apha.org/-/media/Files/PDF/topics/racism/Racism_Declarations_Analysis.ashx

Weber, L. (2022). Pandemic funding is running out for community health workers. Kaiser Health News. Retrieved November 7, 2022, from https://khn.org/news/article/community-health-workers-covid-pandemic-funding-running-out-illinois

Barbero, C., Mason, T., Rush, C., Sugarman, M., Bhuiya, A. R., Fulmer, E. B., Feldstein, J., Cottoms, N., & Wennerstrom, A. (2021). Processes for implementing community health worker workforce development initiatives. Frontiers in Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.659017

Simonsen, S. E., Ralls, B., Guymon, A., Garrett, T., Eisenman, P., Villalta, J., Tavake-Pasi, O. F., Mukundente, V., Davis, F. A., Digre, K., Hayes, S., Alexander, S., Coalition for a Healthier Community for Utah Women and Girls and the Utah Women’s Health Coalition University of Utah. (2017). Addressing health disparities from within the community: Community-based participatory research and community health worker policy initiatives using a gender-based approach. Women’s Health Issues, 27(Suppl 1), S46–S53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2017.09.006

Wilkinson, G. W., Mason, T., Hirsch, G., Calista, J. L., Holt, L., Toledo, J., & Zotter, J. (2016). Community health worker integration in health care, public health, and policy: A partnership model. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 39(1), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1097/JAC.0000000000000124

Dunn, M., Peterson Johnson, E., Smith, B., Cooper, M., & Bhakta, N. (2021). Perspectives on workforce development needs for community health workers (CHWs): Results from a statewide survey of CHW employers. Journal of Community Health, 46(5), 1020–1028. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-021-00986-1

Tucker, C. M., Smith, T. M., Hogan, M. L., Banzhaf, M., Molina, N., & Rodríguez, B. (2018). Current demographics and roles of Florida community health workers: Implications for future recruitment and training. Journal of Community Health, 43(3), 552–559. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-017-0451-3

Trout, K. E., Chaidez, V., & Palmer-Wackerly, A. L. (2020). Rural-urban differences in roles and support for community health workers in the midwest. Family & Community Health, 43(2), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.1097/FCH.0000000000000255

Sugarman, M., Ezouah, P., Haywood, C., & Wennerstrom, A. (2021). Promoting community health worker leadership in policy development: Results from a Louisiana Workforce Study. Journal of Community Health, 46(1), 64–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-020-00843-7

Rodriguez, N. M., Ruiz, Y., Meredith, A. H., Kimiecik, C., Adeoye-Olatunde, O. A., Kimera, L. F., & Gonzalvo, J. D. (2022). Indiana community health workers: Challenges and opportunities for workforce development. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07469-6

State Community Health Worker Models. NASHP. (2023). Retrieved April 6, 2023, from https://www.nashp.org/state-community-health-worker-models/#tab-id-7

Wiggins, N., Kaan, S., Rios-Campos, T., Gaonkar, R., Morgan, E. R., & Robinson, J. (2013). Preparing community health workers for their role as agents of social change: Experience of the community capacitation center. Journal of Community Practice, 21(3), 186–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705422.2013.811622

Dunklee, B., & Garneau, D. (2018). Community health workers in Rhode Island: A study of a growing public health workforce. Rhode Island Medical Journal (2013), 101(6), 40–43.

Ingram, M., Sabo, S., Redondo, F., Soto, Y., Russell, K., Carter, H., Bender, B., & de Zapien, J. G. (2020). Establishing voluntary certification of community health workers in Arizona: A policy case study of building a unified workforce. Human Resources for Health, 18(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-020-00487-7

Haldar, S., & Hinton, E. (2023). State policies for expanding medicaid coverage of community health worker (CHW) Services. KFF. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/state-policies-for-expanding-medicaid-coverage-of-community-health-worker-chw-services/

Allen, C., Brownstein, J. N., Jayapaul-Philip, B., Matos, S., & Mirambeau, A. (2015). Strengthening the effectiveness of state-level community health worker initiatives through ambulatory care partnerships. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 38(3), 254–262. https://doi.org/10.1097/JAC.0000000000000085

Heisler, M., Lapidos, A., Kieffer, E., Henderson, J., Guzman, R., Cunmulaj, J., Wolfe, J., Meyer, T., & Ayanian, J. Z. (2022). Impact on health care utilization and costs of a medicaid community health worker program in Detroit, 2018–2020: A randomized program evaluation. American Journal of Public Health, 112(5), 766–775. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306700

Brown, L. D., Vasquez, D., Salinas, J. J., Tang, X., & Balcázar, H. (2018). Evaluation of healthy fit: A community health worker model to address hispanic health disparities. Preventing Chronic Disease, 15, E49. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd15.170347

Portillo, E. M., Vasquez, D., & Brown, L. D. (2020). Promoting Hispanic immigrant health via community health workers and motivational interviewing. International Quarterly of Community Health Education, 41(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272684X19896731

Obasanjo, I., Griffin, M., Scott, A., Oberoi, S., Westhoff, C., Shelton, P., & Toney, S. (2022). A case study of a community health worker program located in low-income housing in Richmond, Virginia. Journal of Community Health, 47(2), 316–323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-021-01057-1

Cooper, J., Bejster, M., Policicchio, J., Langhorne, T., Jackson, S., Shelton, P., & Toney, S. (2021). Public health nursing and community health worker teams: A community-based preventive services clinic exemplar. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management, 44(4), 264–270. https://doi.org/10.1097/JAC.0000000000000393

Mayor de Blasio launches the NYC Public Health Corps. NYC Health + Hospitals. (2022). Retrieved December 10, 2022, from https://www.nychealthandhospitals.org/pressrelease/mayor-de-blasio-launches-the-nyc-public-health-corps/

Blewett, L. A., & Owen, R. A. (2015). Accountable care for the poor and underserved: Minnesota’s Hennepin Health model. American Journal of Public Health, 105(4), 622–624. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302432

Lohr, A. M., Doubleday, K., Ingram, M., Wilkinson-Lee, A. M., Coulter, K., Krupp, K., Espinoza, C., Redondo-Martinez, F., David, C., & Carvajal, S. C. (2021). A community health worker-led community-clinical linkage model to address emotional well-being outcomes among Latino/a people on the US-Mexico border. Preventing Chronic Disease, 18, E76. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd18.210080

Sabo, S., Wightman, P., McCue, K., Butler, M., Pilling, V., Jimenez, D. J., Celaya, M., & Rumann, S. (2021). Addressing maternal and child health equity through a community health worker home visiting intervention to reduce low birth weight: Retrospective quasi-experimental study of the Arizona Health Start Programme. British Medical Journal Open, 11(6), e045014. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045014

Buder, I., Zick, C., Waitzman, N., Simonsen, S., Sunada, G., & Digre, K. (2018). It takes a village coach: Cost-effectiveness of an intervention to improve diet and physical activity among minority women. Journal of Physical Activity & Health, 15(11), 819–826. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2017-0285

Krantz, M. J., Coronel, S. M., Whitley, E. M., Dale, R., Yost, J., & Estacio, R. O. (2013). Effectiveness of a community health worker cardiovascular risk reduction program in public health and health care settings. American Journal of Public Health, 103(1), e19–e27. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301068

Hammack, A. Y., Bickham, J. N., Gilliard, I., 3rd., & Robinson, W. T. (2021). A community health worker approach for ending the HIV epidemic. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 61(5 Suppl 1), S26–S31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2021.06.008

Gratale, D., & Haushalter, A. (2016). Optimizing health outcomes for children with asthma in Delaware: A population health case report. NAM Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.31478/201609a

Stupplebeen, D. A., Sentell, T. L., Pirkle, C. M., Juan, B., Barnett-Sherrill, A. T., Humphry, J. W., Yoshimura, S. R., Kiernan, J., Hartz, C. P., & Keliikoa, L. B. (2019). Community health workers in action: Community-clinical linkages for diabetes prevention and hypertension management at 3 community health centers. Hawai’i Journal of Medicine & Public Health, 78(6 Suppl 1), 15–22.

Turner, B. J., Liang, Y., Ramachandran, A., & Poursani, R. (2020). Telephone or visit-based community health worker care management for uncontrolled diabetes mellitus: A longitudinal study. Journal of Community Health, 45(6), 1123–1131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-020-00849-1

Chernoff, M., & Cueva, K. (2017). The role of Alaska’s tribal health workers in supporting families. Journal of Community Health, 42(5), 1020–1026. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-017-0349-0

DeAngelis, K. R., Doré, K. F., Dean, D., & Osterman, P. (2017). Strengthening the healthy start workforce: A mixed-methods study to understand the roles of community health workers in healthy start and inform the development of a standardized training program. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 21(Suppl 1), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-017-2377-x

Kaufmann, L. J., Buck Richardson, W. J., Jr., Floyd, J., & Shore, J. (2014). Tribal Veterans Representative (TVR) training program: The effect of community outreach workers on American Indian and Alaska Native Veterans access to and utilization of the Veterans Health Administration. Journal of Community Health, 39(5), 990–996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-014-9846-6

Rahman, R., Ross, A., & Pinto, R. (2021). The critical importance of community health workers as first responders to COVID-19 in USA. Health Promotion International, 36(5), 1498–1507. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daab008

The United States Government. (2022). Fact sheet: Biden-Harris Administration announces American Rescue Plan's historic investments in Community Health Workforce. The White House. Retrieved December 3, 2022, from https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/09/30/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-announces-american-rescue-plans-historic-investments-in-community-health-workforce

Funding

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SI conceived of the study. SI, MB and SG conceptualized the study. SG and AE performed the literature search and analysis. SG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. MB, SI and SG critically revised manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ignoffo, S., Gu, S., Ellyin, A. et al. A Review of Community Health Worker Integration in Health Departments. J Community Health 49, 366–376 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-023-01286-6

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-023-01286-6