Abstract

Purpose

Young mothers are an understudied group at high risk for dating violence (DV) victimization and perpetration. Prior research has investigated depressive symptomatology as a predictor of DV in female adolescents and young women; however, minimal research focuses on young mothers, and the specific mechanisms influencing the relationship between depressive symptomatology and DV for young mothers remain elusive. Interpersonal competency is one potential mechanism given its role in creating healthy foundations for romantic relationships. The present study examined interpersonal competency as a potential mechanism linking depressive symptomatology and DV victimization and perpetration in a sample of young mothers. We hypothesized young mothers with elevated depressive symptomatology would report higher rates of DV victimization and perpetration, and that these associations would be mediated by interpersonal competence.

Methods

Young mothers ages 18–21 in the United States (n = 238) completed questionnaires pertaining to our primary variables of interest via an online, cross-sectional survey. We conducted a mediation analysis to examine the average causal mediation and average direct effects.

Results

DV experiences were related to depressive symptomatology and interpersonal competency. Interpersonal competency was not a mediator; however, direct effects were present between depressive symptomatology and DV victimization and perpetration.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that prevention interventions should target depressive symptomatology (i.e., hopelessness, feeling easily bothered, social isolation) and interpersonal competency (i.e., initiation, disclosure, emotional support) to reduce young mothers’ DV experiences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Thirty-six percent of U.S. women and 34% of U.S. men experience at least one form of dating violence (DV) victimization in their lifetime (Smith et al., 2018). Although anyone can be at risk for experiencing DV victimization, the risk is substantially higher for certain groups of people. For example, individuals between the ages of 18 and 24 years old are at higher risk of DV victimization compared to older individuals (Smith et al., 2018; Truman & Morgan, 2014). Women in this age range report higher rates of DV victimization compared to their male counterparts (Truman & Morgan, 2014). Adolescents experience high rates of DV with 80% encountering either some form of DV victimization and perpetration before reaching adulthood, indicating that DV is a serious, widespread problem in adolescent romantic relationships (Smith et al., 2009). Psychological abuse victimization and perpetration is the most common form of DV among adolescents at 66% for DV victimization and 62% for perpetration respectively (Taylor & Mumford, 2016). An estimate of 8–20% of adolescents report physical DV victimization and 7–18% report sexual DV victimization in their romantic relationships (Kann et al., 2018; Taylor & Mumford, 2016; Wincentak et al., 2016). Moreover, an estimate of 12–25% of adolescents disclose perpetrating physical DV while 3–12% disclose perpetrating sexual DV (Taylor & Mumford, 2016; Wincentak et al., 2016). Other reasons for female perpetration include difficulty with emotion regulation and communication skills as well as previously witnessing interparental violence (Narayan et al., 2014; O’Leary & Slep, 2012; Temple et al., 2013). Finally, rates of DV victimization and perpetration, particularly for verbal and physical DV, ranged from 30 to 35% revealing that a substantial portion of DV among adolescents in romantic relationships is mutual (Fedina et al., 2016; Haynie et al., 2013).

Adolescents and young women between the ages of 12–25 who have children or are currently pregnant, collectively referred to as young mothers, are at high risk for DV victimization and perpetration (Harrykissoon et al., 2002; Joly & Connolly, 2016). Rates of both physical and psychological DV are higher for young mothers compared to non-parenting adolescent women (Herrman et al., 2019; Sue Newman & Campbell, 2011; Wiemann et al., 2005) and older mothers (D’Angelo et al., 2007). Across multiple studies with young mothers, ranging in age from 12 to 21, between 24 and 59% reported experiencing some form of DV victimization (Jacoby et al., 1999; Kennedy & Bennett, 2006; Madkour et al., 2014). Young mothers also face unique DV experiences, such as reproductive coercion, including pressure to have more children and birth control sabotage (i.e., tampering with birth control, refusal to utilize contraception) (Herrman, 2013; Herrman et al., 2019). Additionally, young mothers who did not report DV experiences prior to delivery, endorsed the highest rates of DV victimization 3 months post-partum at 21% (Harrykissoon et al., 2002). Young mothers are particularly at risk for sexual violence, which includes sexual coercion and sexual assault (Lévesque & Chamberland, 2016), and emotional abuse (e.g., insults directed towards the women’s bodies after having a child) (Herrman et al., 2019). Further, young mothers engage in DV perpetration, particularly psychological and physical abuse (Sue Newman & Campbell, 2011). Common reasons for perpetrating DV include stress, punishment for actions their romantic partners’ committed in the past, or in retaliation due to small or large stressors (e.g., partner changes a diaper poorly or cheats) (Herrman et al., 2019). Despite prior studies identifying young mothers are at higher risk of DV victimization and perpetration compared to non-parenting, female adolescents, less is known about the mechanisms that may influence young mothers’ DV experiences.

Theoretical Framework

A developmental perspective can help explain why young mothers are at higher risk for DV victimization and perpetration compared to non-parenting, female adolescents (Sadler & Catrone, 1983). Young mothers are not only developing their identities but are also engaging in parenting responsibilities such as ensuring their children’s basic needs are met (Florsheim et al., 2003; Moore et al., 2007; Osofsky et al., 1988). For young mothers, the stress of adolescence is coupled with parenting stress; an exemplary quote from one young mother states, “You don’t have as much room to figure out how you want to do things because [your parents] are still parenting you. . especially when you’re growing up in the same house” (Herrman et al., 2019, p. 283). It can be overwhelming for young mothers to balance these new responsibilities, especially if they do not have a strong social support system (Florsheim et al., 2003). In some instances, young mothers may choose to become pregnant to cultivate some sense of identity (Unger et al., 2000) and/or to preserve their romantic relationship (Bekaert & SmithBattle, 2016; Kegler et al., 2001). Additionally, young mothers are often stigmatized for violating the social norms assigned to their developmental period (e.g., becoming a parent while also considered to be a child themselves) (Wood & Barter, 2015). This mismatch within young mothers’ developmental period can hinder young mothers’ parenting (Emery et al., 2008), the quality of their romantic relationships (Herrman et al., 2019; Sue Newman & Campbell, 2011), and mental health (Moore & Florsheim, 2001).

Another reason for high rates of DV in young mothers is increased psychological distress, particularly symptoms of depression. Young mothers experience high psychological distress nearly twice as often (13%) compared to their non-parenting peers (7%) (Mollborn & Morningstar, 2009). Young mothers endorse higher rates of depression during the prenatal period as well as 6-months postpartum compared to older mothers regardless of older mothers’ socioeconomic status (Lanzi et al., 2009). Further, during the postpartum period, young mothers’ mean psychological distress scores are higher than older mothers by 6% (Mollborn & Morningstar, 2009). Between 4 and 44% of young mothers met criteria for major depressive disorder postpartum compared to 0 and 20% of older mothers (Hodgkinson et al., 2014; Lanzi et al., 2009). Half of young mothers under the age of 21 met criteria for clinically significant depressive symptoms during the first two years after childbirth (Easterbrooks et al., 2016). However, it is also important to note that most young mothers with depressive symptoms during pregnancy and/or after childbirth, experienced these symptoms and other psychological distress before and unrelated to their pregnancies (Mollborn & Morningstar, 2009). Young mothers who experience mutually violent DV situations, in which both romantic partners perpetrate some form of DV, have higher rates of depression, stress, and hostility, compared to young mothers who do not experience DV or are in a relationship where only one partner perpetrates violence (Lewis et al., 2017; Sue Newman & Campbell, 2011).

Depressive Symptomatology

The relationship between depressive symptomatology and DV is bidirectional. Some research indicates that DV is a predictor of depressive symptomatology (Ackard et al., 2007; Brown et al., 2009; Haynie et al., 2013; Lindhorst & Oxford, 2008), while other studies suggest that depressive symptomatology predicts DV (DiClemente et al., 2001; Exner-Cortens et al., 2013; Foshee et al., 2010). Depressive symptomatology in female adolescents is associated with increased DV victimization and perpetration, especially physical violence (Collibee et al., 2018). Likewise, depressive symptomatology is related to unhealthy relationship norms as well as perceived loss of control in female adolescents’ romantic relationships (DiClemente et al., 2001). Existing research with young women also shows that depressive symptomatology is a predictor of DV victimization (Rao et al., 1999) and perpetration (Capaldi & Crosby, 1997). Although minimal research on depressive symptomatology and DV has been conducted with young mothers, the existing research is consistent with female adolescent and young women literature, in that depressive symptomatology is related to DV (Lewis et al., 2017; Silverman et al., 2006; Thomas et al., 2019). Despite research linking depressive symptomatology to DV experiences, the specific mechanisms influencing this relationship with young mothers remain elusive.

Elevated symptoms of depression can interfere with social functioning resulting in greater DV experiences (Collibee et al., 2018). Impaired social cognition has been recognized as a crucial component to major depressive disorder particularly due to issues with verbal communication and interpersonal skills (Jones et al., 2019; Weightman et al., 2019). Individuals with depression often interpret social situations negatively due to cognitive distortions (e.g., overgeneralization, catastrophizing, rumination) and learned negative schemas about relationships (Craighead et al., 2013). These depressive symptoms can then lead to increased social isolation and feeling withdrawn from others, as well as increased irritability, and further compromising interpersonal functioning (Craighead et al., 2013; Hames et al., 2013; Jones et al., 2019). Likewise, people’s view of themselves can be modified due to social disruptions, or negative life events in one’s environment, which could result in negative, or maladaptive, social functioning skills (Oatley & Bolton, 1985).

According to interpersonal stress generation theory, individuals with depressive symptomatology have an active role in generating stressful situations with others which not only increase interpersonal vulnerabilities but also depressive symptoms (Hammen, 1991, 2006). Female adolescents with depressive symptoms, who also experience early onset of puberty, are at higher risk for subsequent interpersonal vulnerabilities compared to later-maturing youth (Conley & Rudolph, 2009; Rudolph, 2008). Furthermore, interpersonal stress partially mediated the relationship between female adolescents’ initial and later depressive symptoms (Meiser & Esser, 2019). Similarly, difficulties in social functioning among youth partially mediated the relationship between depressive symptoms and DV victimization (Keenan-Miller et al., 2007). For young mothers between the ages of 15–20, depressive symptoms predicted interpersonal difficulties (Hammen et al., 2011).

Interpersonal Competency

Interpersonal skills help to create healthy foundations for romantic relationships and are considered a significant life skill to acquire in the transition between adolescence and adulthood (Scales et al., 2016). According to Buhrmester and colleagues (1988), there are five interpersonal skills that comprise a person’s “interpersonal competency”: (1) initiation (of interactions and relationships), (2) assertiveness (of personal rights and displeasure with others), (3) self-disclosure (of personal information), (4) conflict management (of conflicts that arise in close relationships), and (5) emotional support (of others). However, most research has primarily examined the interpersonal skills of assertiveness, conflict management, and emotional support. Assertiveness, which can also be defined as the ability to communicate one’s needs in a respectful and non-combative way, has been linked to positive problem-solving skills (Xia et al., 2018) and is a protective factor against DV victimization (Simpson Rowe et al., 2012; Wolfe et al., 2003). Conflict management is related to both adolescent DV victimization and perpetration (Bonache et al., 2017). For example, female adolescents who engaged in withdrawing strategies (e.g., becoming silent, refusing to discuss and/or avoiding conflict) were less likely to experience psychological and physical violence, serving as a counterintuitive protective factor within their relationship context, meanwhile, female adolescents who engaged in conflict engagement strategies (e.g., criticizing, attacking, and losing self-control) experienced higher levels of psychological abuse (Bonache et al., 2017). Similarly, adolescents who engaged in poor conflict management (e.g., using aggression to resolve conflict) predicted physical DV perpetration (Cohen et al., 2018). Furthermore, adolescent couples with greater levels of hostility and lower levels of warmth within their romantic relationship experienced higher rates of physical DV perpetration and victimization (Moore et al., 2007). While limited research exists demonstrating the link between interpersonal competency and DV, there is a dearth of evidence demonstrating this relationship in young mothers.

Present Study

The present study seeks to examine interpersonal competency as a potential mechanism responsible for the relationship between depressive symptomatology and DV victimization and perpetration in a sample of young mothers. Depressive symptoms can interfere with individuals’ social functioning (Hammen, 2006; Moore et al., 2007). Both depressive symptoms (Collibee et al., 2018; Exner-Cortens et al., 2013) and interpersonal skills (Bonache et al., 2017; Simpson Rowe et al., 2012; Wolfe et al., 2003; Xia et al., 2018) are related to DV risk. Thus, it is plausible that lower interpersonal competency may explain the link between depressive symptoms and young mothers’ DV victimization and perpetration. We hypothesize the following: (1) higher depressive symptomatology will be associated with greater DV victimization and perpetration, (2) higher depressive symptomatology will be associated with lower interpersonal competency, (3) lower interpersonal competency will be associated with greater DV victimization and perpetration, and (4) lower interpersonal competency will mediate the relationship between depressive symptomatology and DV victimization and perpetration. This study hopes to fill a gap in the literature about young mothers’ interpersonal skills and why they should be targeted in future DV prevention-interventions for young mothers.

Method

Participants

This study uses the term “young mothers” to define adolescents and young women between the ages of 18 and 21 who gave birth to a child when they were 21 years of age or younger. Young mothers had to be at least 18 years old to participate in the online survey. Young mothers also had to live with at least one biological child and be able to speak and read English. Our sample consisted of 238 young mothers who were predominantly white (84%), non-Hispanic/Latina (85%), and female-identifying (98%). Participants were given the opportunity to select more than one racial identity. Self-reported racial identities included 14% Black, 3% Asian, 3% American Indian/Alaskan Native, and 0.8% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander. The average age of young mothers was M = 19.8 years (SD = 1.0) and the age in which young mothers gave birth to their first child ranged from 14 to 21, M = 18.6 years (SD = 1.6). Eighty-one percent of young mothers were currently or most recently in a romantic relationship with the biological father of their children. Most young mothers (81%) had only one child, followed by 15% of young mothers who had two children. Fourty-eight percent were high school graduates, 30% had some college education (at least 1 year), and 16% had some high school education (at least 10th or 11th grade). Most young mothers in our sample were currently unemployed (60%), 20% worked full-time, and 19% worked part-time. Fourty-nine percent grew up in rural communities and 36% grew up in suburban communities, meanwhile, only 4% grew up in either an urban or megalopolis community.

Procedure

Young mothers ages 18–21 were recruited nationwide, using social media ads, to complete a series of questionnaires via an online survey. Participants had to provide electronic consent before viewing the questionnaires. Data was collected over the course of three years (2016 to 2019) and a part of a larger research study on young mothers’ relationships. Response time, on average, was approximately 80 min. A $10 gift card was distributed to participants as compensation. All study procedures were approved by the university’s institutional review board.

Measures

Depressive Symptomatology

The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale-10 (CES-D-10) is a 10-item self-report measure of major depressive disorder symptoms (Andresen et al., 1994). The measure has been found to be reliable with low-income, single mothers (Carpenter et al., 1998) as well as individuals who identify as Hispanic/Latina (González et al., 2017). Participants were asked to rate their depressive symptoms within the past week on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = “rarely or none of the time” to 3 = “most or all of the time”). Total summed scores range from 0 to 30, with a cutoff score of 10 or more indicating significant depressive symptoms and marking participants as “at-risk” for depression (Andresen et al., 1994). A total summed score was computed to assess overall depressive symptomatology. Cronbach’s α for the CES-D-10 is 0.85 (Andresen et al., 1994). Within our sample, the Cronbach’s α is 0.89.

Interpersonal Competency

The Interpersonal Competence Questionnaire (ICQ; Buhrmester et al., 1988) is a 40-item, self-report questionnaire that measures interpersonal skills on five subscales: (1) initiation, (2) negative assertion, (3) disclosure, (4) emotional support, and (5) conflict management. Participants rated their interpersonal competency on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “I’m poor at this” to 5 = “I’m extremely good at this”). Mean scores were computed for each subscale and then used to compute an overall total interpersonal competency score. Greater scores indicate stronger interpersonal competency while lower scores indicate a lower interpersonal competency. Although the ICQ has only been normed on college students (Buhrmester et al., 1988), the internal consistency of the ICQ subscales ranged from 0.77 to 0.87. Cronbach’s α for the ICQ within our sample is 0.95.

Dating Violence

The Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (CADRI; Wolfe et al., 2001) is a 70-item, self-report questionnaire that assesses both DV perpetration and victimization in adolescent relationships. Young mothers’ relationships, similar to adolescents’ relationships, tend to be brief, exploratory, and have lower levels of commitment (Cascardi, 2016; Florsheim et al., 2003); thus, we used the CADRI to measure DV experiences in young mothers. This measure has also been deemed appropriate to use with individuals from varying races/ethnicities (Shorey et al., 2019). The CADRI measures a wide range of DV behaviors that are broken down into five subscales: (1) threatening behavior, (2) relational aggression, (3) physical abuse, (4) emotional abuse, and (5) sexual abuse. Participants rated their potential DV experiences from the past year of their relationship on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = “never” to 3 = “often”). We computed a mean score for each subscale and then summed these means to create total perpetration and victimization scores. Greater scores indicate higher levels of DV perpetration and victimization. Internal consistency of the CADRI subscales ranged from 0.54 to 0.83 (Wolfe et al., 2001). Cronbach’s α for the CADRI within our sample is 0.92.

Analytic Strategy

The univariate distributions of our two continuous outcome variables, DV perpetration and victimization, were positively skewed. Consequently, we used a generalized linear model, specifically a gamma regression model, to model our data and answer our research question (Fife, 2020). Study hypotheses were tested using the mediation R package (Tingley et al., 2014), which estimates the average causal mediation effects (ACME), and the average direct effects (ADE) (Tingley et al., 2014), as well as bootstrapped confidence intervals.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

DV experiences among our sample of young mothers were relatively high. 173 participants out of 238 reported engaging in DV perpetration over the past year (M = 2.1, SD = 2.0). Thirty-five percent of young mothers perpetrated threatening behavior, 39% perpetrated physical abuse, 38% perpetrated sexual abuse, 17% perpetrated relational aggression, and 98% perpetrated emotional abuse. Furthermore, 175 out of 238 participants reported experiencing DV victimization over the past year (M = 2.9, SD = 3.2). Fourty-five percent of young mothers experienced threatening behavior, 33% experienced physical abuse, 59% experienced sexual abuse, 23% experienced relational aggression, and 97% experienced emotional abuse. Additionally, depressive symptomatology was moderately elevated in our sample (M = 13.6, SD = 7.3). Sixty-eight percent of young mothers showed a clinical risk of depression. Finally, young mothers’ total interpersonal competency was moderately strong (M = 3.6, SD = 0.7).

Preliminary Analyses: Model Comparisons

We utilized the flexplot R package to visualize and compute how interpersonal competency may improve the fit of our reduced models, containing depressive symptomatology and DV experiences; one model for perpetration and another for victimization (Rodgers, 2010). Thus, we compared the following full and reduced models:

Statistics for the model comparisons including the AIC, BIC, Bayes factor, and p-value, can be found in Tables 1 and 2. All statistics favored the full models which included interpersonal competency as a predictor of DV perpetration and victimization.

Primary Analyses: Mediation

DV Perpetration

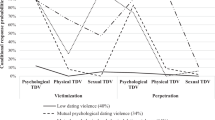

We tested each pathway of our proposed gamma mediation model (X = depressive symptomatology, M = interpersonal competency, and Y = DV perpetration) using gamma regressions. There is a positive relationship between depressive symptomatology and DV perpetration b1 = 0.22, p < .001. Greater depressive symptomatology was associated with less interpersonal competency, b2 = -0.01, p < .01. When controlling for depressive symptomatology, greater interpersonal competency was associated with less DV perpetration, b3 = -0.22, p < .001. When interpersonal competency was present in the regression, it reduced the effect of depressive symptomatology, b4 = 0.18, p < .01. A mediation analysis using nonparametric bootstrapping revealed that the effect of depressive symptomatology on DV perpetration was not mediated by interpersonal competency, ACME = 0.00, CI [-0.09, 0.11], p = .82. However, there was a direct effect between depressive symptomatology and DV perpetration, ADE = 0.04, CI [0.02, 0.06], p < .001; see Fig. 1.

DV Victimization

We used the same procedure for a second mediation analysis with DV victimization as the outcome variable. A positive relationship between depressive symptomatology and DV victimization was present, b1 = 0.04, p < .001. Similarly, greater depressive symptomatology was associated with less interpersonal competency, b2 = -0.01, p < .01. Greater interpersonal competency was associated with less DV victimization after controlling for depressive symptomatology, b3 = -0.25, p < .001. The effect of depressive symptomatology was reduced when interpersonal competency was present in the regression, b4 = 0.03, p < .001. A mediation analysis using nonparametric bootstrapping suggested the effect of depressive symptomatology on DV victimization was not mediated by interpersonal competency, ACME = -0.07, CI [-0.08, 0.11], p = .81. However, there was a direct effect between depressive symptomatology and DV victimization, ADE = 0.08, CI [0.05, 0.10], p < .001; see Fig. 2.

Sensitivity Analyses

Interpersonal competency did not mediate the relationship between depressive symptomatology and DV perpetration and victimization. We hypothesized three subscales of interpersonal competency may mediate the relationship between depressive symptomatology and DV perpetration and victimization based on prior research with specific assets of interpersonal competency, such as assertiveness (Simpson Rowe et al., 2012), conflict management (Bonache et al., 2017) and emotional support (Moore et al., 2007), rather than our total interpersonal competency variable. We conducted sensitivity analyses utilizing the same mediation analysis procedure as our primary analyses to better understand whether our results would be affected if our mediator variable changed (Thabane et al., 2013).

Conflict management did not mediate the relationships between depressive symptomatology and DV victimization and perpetration, ACME = 0.01, CI [-0.21, 0.21], p = .96 and ACME = 0.09, CI [-0.07, 0.07], p = .99. Emotional support also did not mediate these relationships, ACME = -0.02, CI [-0.26, 0.11], p = .54 and ACME = 0.02, CI [-0.03, 0.06], p = .68. Further, assertiveness did not mediate these relationships, ACME = -0.05, CI [-0.22, 0.22], p = .97 and ACME = 0.01, CI [-0.04, 0.04], p = .96. Our exploratory results showed independent, negative associations between conflict management and DV victimization and perpetration, respectively, b3 = -0.31, p < .001 and b3 = -0.15, p < .001. Similar results were found between assertiveness and DV victimization and perpetration, b3 = -0.30, p < .001 and b3 = -0.08, p < .05. There was a positive association between emotional support and DV victimization, b3 = 0.13, p < .01 but no association between emotional support and DV perpetration, b3 = -0.46, p > .05.

Discussion

Our first hypothesis, that higher depressive symptomatology is associated with higher DV victimization and perpetration, was supported. This finding is consistent with previous work showing the link between depressive symptomatology and DV in young mothers (Lewis et al., 2017; Silverman et al., 2006; Thomas et al., 2019). It is notable that 68% of the young mothers in our sample obtained scores that signify they are at-risk for clinical depression, delineating their experiences of psychological distress. This finding continues to support past literature relating to how young mothers experience greater psychological distress compared to non-parenting, female adolescents as well as older mothers (Lanzi et al., 2009; Mollborn & Morningstar, 2009). Although prior research has demonstrated a bidirectional relationship between depressive symptomatology and DV (Exner-Cortens et al., 2013; Haynie et al., 2013), our results add to the body of literature of how salient depressive symptomatology can be in predicting DV experiences. Young mothers with moderately elevated depressive symptomatology may be more vulnerable to experiences of DV victimization by their romantic partner while also, more vulnerable to perpetrating acts of DV themselves. Depressive symptomatology seems to be a barrier for young mothers’ and having healthy relationships, without instances of DV victimization or perpetration.

Our second hypothesis, that higher depressive symptomatology would be associated with less interpersonal competency, was supported, thereby extending this association from the non-parenting, female adolescent literature to young mothers (Collibee et al., 2018). Depressive symptomatology, which can include but is not limited to, feeling everything they do is an effort, increased loneliness and irritability, and decreased hope about the future, appears to negatively influence young mothers’ social functioning within their romantic relationships. Young mothers’ endorsement of depressive symptomatology is negatively correlated with their interpersonal skills. Similarly, our third hypothesis associating less interpersonal competency to higher DV victimization and perpetration was also supported. Our findings show interpersonal competency is a pertinent construct when examining DV in young mothers, as with adolescent girls’ dating relationships (Bonache et al., 2017; Moore et al., 2007). Effective, interpersonal skills may serve as foundational, building blocks to having a healthy relationship. Thus, young mothers who may experience difficulties with interpersonal competency, or in other words, ineffectively utilizing the five core interpersonal skills of initiation, assertiveness, self-disclosure, conflict management, and emotional support, may be at risk for DV victimization and perpetration.

Interpersonal competency did not mediate the relationship between depressive symptomatology and DV victimization and perpetration on contrary to our fourth hypothesis. This result led us to investigate whether our summed interpersonal competency variable as the mediator was the most effective choice within our mediation analyses, given the support of our bivariate associations within our mediation models, as well as prior literature on specific interpersonal skills in relation to DV. Specific interpersonal skills that comprise interpersonal competency may still influence young mothers’ DV experiences, despite neither interpersonal competency nor individual skills mediating these relationships. It is reasonable to note the importance of interpersonal competency in healthy, romantic relationships given that this construct independently relates to young mothers’ condom negotiation (Herrman, 2013; Kershaw et al., 2007), sexual risk behaviors (Cox et al., 1999), and DV experiences (Moore et al., 2007). Nevertheless, the relationship between depressive symptomatology and DV victimization and perpetration may be mediated by a different mechanism such as cognitive appraisals of traumatic experiences (e.g., witnessing domestic violence as a child) (Bekaert & SmithBattle, 2016) or cognitive distortions (e.g., catastrophizing) (Craighead et al., 2013).

There were several limitations to this study that are important to consider when interpreting our results. First, our primary predictor variable of young mothers’ depressive symptomatology was measured with the instructions to report symptomatology over the past week compared to young mothers’ report of their DV experiences over the past year. A longer assessment of young mothers’ depressive symptomatology may remove any potential reporting bias when reflecting on their DV experiences. Yet, despite this limitation, depressive symptoms are theorized to make adolescent females more vulnerable to remaining in low quality or abusive romantic relationships (Collibee et al., 2018). Thus, the salience of depressive symptomatology may also explain why reported depressive symptoms within the past week among young mothers contributed to their DV experiences over the past year which may in turn, continue to influence their depressive symptoms. As previously mentioned, there is evidence of a negative feedback loop between depressive symptomatology and interpersonal competency (Hames et al., 2013; Jones et al., 2019). Although we chose to utilize our data to examine how depressive symptomatology can increase DV experiences, future cross-sectional and longitudinal research should not only continue to examine this pathway but also how DV experiences may increase depressive symptomatology. Second, although there are other measures to assess DV perpetration, such as the newly developed Relationship Behavior Survey (RBS; Cascardi et al., 2023) which includes a more robust assessment of emotional/psychological abuse among adolescents as well as appraisal of perpetrator intent, there is no inclusion of DV victimization. Thus, a measure such as the CADRI, was selected to assess both victimization and perpetration given high rates of mutual DV among young mothers. However, since rates of emotional abuse perpetration and victimization was quite high within our sample at 98 and 97% respectively, it would be helpful if future studies included the RBS to assess types of emotional abuse experiences in young mother samples. It may also be vital to include an assessment of young mothers’ attachment styles, given their influence on romantic relationships, particularly as it relates to interpersonal competency and DV (Bonache et al., 2017; Théorêt et al., 2021).

Next, a more diverse age range of young mothers, such as 15 to 25, could have uncovered more variability within our primary variables due to developmental level and parenting experience. Relatedly, our sample was overwhelmingly white which may not capture experiences faced by young mothers of underrepresented racial/ethnic groups. Future recruitment strategies should include nationwide social media ads coupled with outreach to community-based organizations (e.g., OB/GYN and pediatric clinics, non-profit organizations for young mothers) as well as oversampling of young mothers from various backgrounds to increase overall diversity in our sample. Moreover, the young mothers in this sample scored relatively high on the ICQ questionnaire, indicating a higher baseline of interpersonal skills. Thus, creating two groups (high vs. low interpersonal competency) could have been a better fit for our mediation models. Future studies could extend this line of research by correcting these limitations and investigating the possibility of a different underlying mechanism as the mediator between depressive symptomatology and DV.

Despite study limitations, the present study is one of the first of its kind to assess the relationships between depressive symptomatology, interpersonal competency, and DV perpetration and victimization among young mothers. These results will be utilized to inform needed future DV and sexual risk behavior prevention-intervention for young mothers. To authors’ knowledge, there is a critical evidence gap within interventions focused on reducing DV victimization and perpetration for young mothers (Laurenzi et al., 2020). Since there was a direct effect present between depressive symptomatology and DV victimization and perpetration, providers working with young mothers may reduce DV experiences by targeting depressive symptomatology (i.e., hopelessness, feeling easily bothered, social isolation) through a skills-based intervention as similarly done with non-parenting, female adolescents (Rizzo et al., 2018). Our results provide preliminary support for an adaptation of this intervention model for young mothers. Further, our finding that less interpersonal competency (i.e., initiation, disclosure, conflict management) is negatively associated with increased DV victimization and perpetration shows the need for providers to target young mothers’ interpersonal competency skills. We believe our focus on interpersonal competency begins to answer the urgent call for interventions to better support young mothers (Laurenzi et al., 2020). Teaching young mothers concrete skills to improve their interpersonal competency may be a more viable and straightforward way to build and strengthen healthy romantic relationships, thus preventing DV experiences.

Finally, our research team will take a community based participatory approach to research by disseminating study results to nearby OB/GYN and pediatric clinics as well as organizations dedicated to the well-being of young mothers. The purpose in engaging in this dissemination work is to support the translation of research into practice. We intend to accomplish dissemination by packaging findings in an appropriate format, including the use of visualizations such as charts, graphs, and infographics as well as offering didactics/workshops. We hope through dissemination we can strengthen our relationships with community partners and work together with local providers to improve understanding of DV among young mothers.

References

Ackard, D. M., Eisenberg, M. E., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2007). Long-term impact of adolescent dating violence on the Behavioral and Psychological Health of Male and female youth. The Journal of Pediatrics, 151(5), 476–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.034.

Andresen, E. M., Malmgren, J. A., Carter, W. B., & Patrick, D. L. (1994). Screening for Depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10(2), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(18)30622-6.

Bekaert, S., & SmithBattle, L. (2016). Teen mothers’ experience of intimate Partner violence. Advances in Nursing Science, 39(3), 272–290. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANS.0000000000000129.

Bonache, H., Gonzalez-Mendez, R., & Krahé, B. (2017). Romantic attachment, Conflict Resolution styles, and Teen dating violence victimization. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46, 1905–1917. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0635-2.

Brown, A., Cosgrave, E., Killackey, E., Purcell, R., Buckby, J., & Yung, A. R. (2009). The Longitudinal Association of Adolescent Dating Violence with Psychiatric Disorders and Functioning. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(12), 1964–1979. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260508327700.

Buhrmester, D., Furman, W., Wittenberg, M. T., & Reis, H. T. (1988) Five domains of interpersonal competence in peer relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55(6), 991–1008. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.55.6.991

Capaldi, D. M., & Crosby, L. (1997). Observed and reported psychological and physical aggression in Young, At-Risk couples. Social Development, 6(2), 184–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.1997.tb00101.x.

Carpenter, J. S., Andrykowski, M. A., Wilson, J., Hall, L. A., Rayens, M. K., Sachs, B., & Cunningham, L. L. (1998). Psychometrics for two short forms of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 19(5), 481–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/016128498248917.

Cascardi, M. (2016). From violence in the home to physical dating violence victimization: The mediating role of psychological distress in a prospective study of female adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 777–792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0434-1.

Cascardi, M., Hassabelnaby, R., Schorpp, H., Smith Slep, A. M., Jouriles, E. N., & O’Leary, K. D. (2023). The Relationship Behavior Survey: A Comprehensive measure of psychological intimate Partner violence for adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(9–10), 7012–7036. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221140044.

Cohen, J. R., Shorey, R. C., Menon, S. V., & Temple, J. R. (2018). Predicting Teen dating violence perpetration. Pediatrics, 141(4). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-2790.

Collibee, C., Rizzo, C. J., Kemp, K., Hood, E., Doucette, H., Stone, D. I. G., & DeJesus, B. (2018). Depressive symptoms moderate dating violence Prevention outcomes among adolescent girls. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518770189.

Conley, C. S., & Rudolph, K. D. (2009). The emerging sex difference in adolescent depression: Interacting contributions of puberty and peer stress. Development and Psychopathology, 21(2), 593–620. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579409000327.

Craighead, E. W., Miklowitz, D. J., & Craighead, L. W. (2013). Psychopathology history, diagnosis, and empirical foundations (2nd ed.). Wiley.

D’Angelo, D., Williams, L., Morrow, B., Cox, S., Harris, N., Harrison, L., Posner, S. F., Hood, R., J. R., & Zapata, L. (2007). Preconception and Interconception Health Status of Women Who Recently Gave Birth to a Live-Born Infant—Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), United States, 26 Reporting Areas, 2004. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 56(SS10), 1–35.

DiClemente, R. J., Wingood, G. M., Crosby, R. A., Sionean, C., Brown, L. K., Rothbaum, B., Zimand, E., Cobb, B. K., Harrington, K., & Davies, S. (2001). A prospective study of psychological distress and sexual risk Behavior among Black adolescent females. PEDIATRICS, 108(5), e85–e85. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.108.5.e85.

Easterbrooks, M. A., Kotake, C., Raskin, M., & Bumgarner, E. (2016). Patterns of Depression among adolescent mothers: Resilience related to Father Support and Home Visiting Program. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 86(1), 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000093.

Exner-Cortens, D., Eckenrode, J., & Rothman, E. (2013). Longitudinal associations between Teen dating violence victimization and adverse Health outcomes. PEDIATRICS, 131(1), 71–78. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1029.

Fedina, L., Howard, D. E., Wang, M. Q., & Murray, K. (2016). Teen dating violence victimization, perpetration, and Sexual Health Correlates among Urban, Low-Income, ethnic, and racial Minority Youth. International Quaterly of Community Health Education, 37(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272684X16685249.

Fife, D. (2020). The Eight Steps of Data Analysis: A graphical Framework to Promote Sound Statistical Analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 15(4), 1054–1075. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620917333.

Florsheim, P., Sumida, E., McCann, C., Winstanley, M., Fukui, R., Seefeldt, T., & Moore, D. (2003). The transition to parenthood among young African American and latino couples: Relational predictors of risk for parental dysfunction. Journal of Family Psychology, 17(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.17.1.65.

Foshee, V. A., McNaughton Reyes, H. L., & Ennett, S. T. (2010). Examination of sex and race differences in longitudinal predictors of the initiation of adolescent dating violence perpetration. Journal of Aggression Maltreatment & Trauma, 19(5), 492–516. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2010.495032.

González, P., Nuñez, A., Merz, E., Brintz, C., Weitzman, O., Navas, E. L., Camacho, A., Buelna, C., Penedo, F. J., Wassertheil-Smoller, S., Perreira, K., Isasi, C. R., Choca, J., Talavera, G. A., & Gallo, L. C. (2017). Measurement properties of the Center for epidemiologic studies Depression Scale (CES-D 10): Findings from HCHS/SOL. Psychological Assessment, 29(4), 372–381. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000330.

Hames, J. L., Hagan, C. R., & Joiner, T. E. (2013). Interpersonal processes in Depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 355–377. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185553.

Hammen, C. (1991). Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 100(4), 555–561. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.100.4.555.

Hammen, C. (2006). Stress generation in depression: Reflections on origins, research, and future directions. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(9), 1065–1082. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20293.

Hammen, C., Brennan, P. A., & Le Brocque, R. (2011). Youth depression and early childrearing: Stress generation and intergenerational transmission of depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(3), 353–363. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023536.

Harrykissoon, S. D., Rickert, V. I., & Wiemann, C. M. (2002). Prevalence and patterns of intimate partner violence among adolescent mothers during the postpartum period. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 156(4), 325–330. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.156.4.325.

Haynie, D. L., Farhat, T., Brooks-Russell, A., Wang, J., Barbieri, B., & Iannotti, R. J. (2013). Dating violence perpetration and victimization among US adolescents: Prevalence, patterns, and associations with health complaints and substance use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(2), 194–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.02.008.

Herrman, J. W. (2013). How teen mothers describe dating violence. Journal of Obstetric Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 42(4), 462–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/1552-6909.12228.

Herrman, J. W., Palen, L. A., Kan, M., Feinberg, M., Hill, J., Magee, E., & Haigh, K. M. (2019). Young mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of Relationship Violence: A Focus Group Study. Violence against Women, 25(3), 274–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801218780356.

Hodgkinson, S., Beers, L., Southammakosane, C., & Lewin, A. (2014). Addressing the mental health needs of pregnant and parenting adolescents. Pediatrics, 133(1), 114–122.

Jacoby, M., Gorenflo, D., Black, E., Wunderlich, C., & Eyler, A. E. (1999). Rapid repeat pregnancy and experiences of interpersonal violence among low-income adolescents. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 16(4), 318–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0749-3797(99)00029-x.

Joly, L. E., & Connolly, J. (2016). Dating violence among high-risk Young women: A systematic review using quantitative and qualitative methods. Behavioral Sciences, 6(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs6010007.

Jones, J. D., Gallop, R., Gillham, J. E., Mufson, L., Farley, A. M., Kanine, R., & Young, J. F. (2019). The Depression Prevention Initiative: Mediators of interpersonal psychotherapy–adolescent skills training. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 0(0), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2019.1644648.

Kann, L., McManus, T., Harris, W. A., Shanklin, S. L., Flint, K. H., Queen, B., Lowry, R., Chyen, D., Whittle, L., Thornton, J., Lim, C., Bradford, D., Yamakawa, Y., Leon, M., Brener, N., & Ethier, K. A. (2018). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2017. MMWR Surveillance Summaries, 67(8), 1–114. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6708a1.

Keenan-Miller, D., Hammen, C., & Brennan, P. (2007). Adolescent psychosocial risk factors for severe intimate partner violence in young adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(3), 456–463. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.75.3.456.

Kegler, M. C., Bird, S. T., Kyle-Moon, K., & Rodine, S. (2001). Understanding teen pregnancy from the perspective of Young adolescents in Oklahoma City. Health Promotion Practice, 2(3), 242–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/152483990100200308.

Kennedy, A. C., & Bennett, L. (2006). Urban adolescent mothers exposed to community, family, and partner violence: Is cumulative violence exposure a barrier to school performance and participation? Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21(6), 750–773. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260506287314.

Lanzi, R. G., Bert, S. C., & Jacobs, B. K. (2009). Depression among a sample of first-time adolescent and adult mothers. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 22(4), 194–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2009.00199.x.

Laurenzi, C. A., Gordon, S., Abrahams, N., du Toit, S., Bradshaw, M., Brand, A., Melendez-Torres, G. J., Tomlinson, M., Ross, D. A., Servili, C., Carvajal-Aguirre, L., Lai, J., Dua, T., Fleischmann, A., & Skeen, S. (2020). Psychosocial interventions targeting mental health in pregnant adolescents and adolescent parents: A systematic review. Reproductive Health, 17(1), 65. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-00913-y.

Lévesque, S., & Chamberland, C. (2016). Intimate Partner Violence among pregnant Young women: A qualitative Inquiry. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31(19), 3282–3301. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515584349.

Lewis, J. B., Sullivan, T. P., Angley, M., Callands, T., Divney, A. A., Magriples, U., Gordon, D. M., & Kershaw, T. S. (2017). Psychological and relational correlates of intimate partner violence profiles among pregnant adolescent couples. Aggressive Behavior, 43(1), 26–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21659.

Lindhorst, T., & Oxford, M. (2008). The long-term effects of intimate partner violence on adolescent mothers’ depressive symptoms. Social Science & Medicine, 66, 1322–1333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.045.

Madkour, A. S., Xie, Y., & Harville, E. W. (2014). Pre-pregnancy dating violence and birth outcomes among adolescent mothers in a National Sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(10), 1894–1913. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260513511699.

Meiser, S., & Esser, G. (2019). Interpersonal stress Generation—A girl problem? The role of depressive symptoms, dysfunctional attitudes, and gender in early adolescent stress generation. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 39(1), 41–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431617725197.

Mollborn, S., & Morningstar, E. (2009). Investigating the relationship between teenage childbearing and psychological distress using Longitudinal Evidence*. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 50(3), 310–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650905000305.

Moore, D. R., & Florsheim, P. (2001). Interpersonal processes and psychopathology among expectant and nonexpectant adolescent couples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.69.1.101.

Moore, D. R., Florsheim, P., & Butner, J. (2007). Interpersonal behavior, psychopathology, and relationship outcomes among adolescent mothers and their partners. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology : The Official Journal for the Society of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, American Psychological Association, Division 53, 36(4), 541–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410701662709.

Narayan, A. J., Englund, M. M., Carlson, E. A., & Egeland, B. (2014). Adolescent conflict as a developmental process in the prospective pathway from exposure to Interparental Violence to dating violence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(2), 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9782-4.

O’Leary, K. D., & Slep, A. M. S. (2012). Prevention of partner violence by focusing on behaviors of both young males and females. Prevention Science, 13(4), 329–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-011-0237-2.

Oatley, K., & Bolton, W. (1985). A Social-Cognitive Theory of Depression in reaction to life events. Psychological Review, 92(3), 372–388. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.92.3.372.

Osofsky, J. D., Osofsky, H. J., & Diamond, M. O. (1988). The transition to parenthood: Special tasks and risk factors for adolescent parents. In G. Y. Michaels, W. A. Goldberg, G. Y. (Ed.) Michaels, & W. A. (Ed.) Goldberg (Eds.), The transition to parenthood: Current theory and research (1988-98534-008; pp. 209–232). Cambridge University Press.

Rao, U., Hammen, C., & Daley, S. E. (1999). Continuity of depression during the transition to adulthood: A 5-year longitudinal study of young women. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(7), 908–915. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199907000-00022.

Rizzo, C. J., Joppa, M., Barker, D., Collibee, C., Zlotnick, C., & Brown, L. K. (2018). Project date smart: A dating violence (dv) and sexual risk prevention program for adolescent girls with prior dv exposure. Prevention Science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0871-z.

Rodgers, J. L. (2010). The epistemology of mathematical and statistical modeling: A quiet methodological revolution. American Psychologist, 65(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018326.

Rudolph, K. D. (2008). Developmental influences on interpersonal stress generation in depressed youth. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117(3), 673–679. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.117.3.673.

Sadler, L. S., & Catrone, C. (1983). The adolescent parent. Journal of Adolescent Health Care, 4(2), 100–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-0070(83)80027-8.

Scales, P. C., Benson, P. L., Oesterle, S., Hill, K. G., Hawkins, J. D., & Pashak, T. J. (2016). The dimensions of successful young adult development: A conceptual and measurement framework. Applied Developmental Science, 20(3), 150–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2015.1082429.

Shorey, R. C., Allan, N. P., Cohen, J. R., Fite, P. J., Stuart, G. L., & Temple, J. R. (2019). Testing the factor structure and measurement invariance of the conflict in adolescent dating relationship inventory. Psychological Assessment, 31(3), 410–416. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000678.

Silverman, J. G., Decker, M. R., Reed, E., & Raj, A. (2006). Intimate partner violence victimization prior to and during pregnancy among women residing in 26 U.S. states: Associations with maternal and neonatal health. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 195(1), 140–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2005.12.052.

Simpson Rowe, L., Jouriles, E. N., McDonald, R., Platt, C. G., & Gomez, G. S. (2012). Enhancing women’s resistance to sexual coercion: A randomized controlled trial of the DATE program. Journal of American College Health, 60(3), 211–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2011.587068.

Smith, P. H., White, J. W., & Moracco, K. E. (2009). Becoming who we are: A theoretical explanation of gendered social structures and social networks that shape adolescent interpersonal aggression. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33, 25–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.01470.x.

Smith, S. G., Zhang, X., Basile, K. C., Merrick, M. T., Wang, J., Kresnow, M. J., & Chen, J. (2018). The national intimate Partner and sexual violence survey: 2015 data brief – updated release. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/2015data-brief508.pdf.

Sue Newman, B., & Campbell, C. (2011). Intimate Partner Violence among pregnant and parenting latina adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 26(13), 2635–2657. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260510388281.

Taylor, B. G., & Mumford, E. A. (2016). A National descriptive portrait of adolescent relationship abuse: Results from the National Survey on Teen relationships and intimate Violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31(6), 963–988. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514564070.

Temple, J. R., Shorey, R. C., Tortolero, S. R., Wolfe, D. A., & Stuart, G. L. (2013). Importance of gender and attitudes about violence in the relationship between exposure to interparental violence and the perpetration of teen dating violence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(5), 343–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.02.001.

Thabane, L., Mbuagbaw, L., Zhang, S., Samaan, Z., Marcucci, M., Ye, C., Thabane, M., Giangregorio, L., Dennis, B., Kosa, D., Debono, V. B., Dillenburg, R., Fruci, V., Bawor, M., Lee, J., Wells, G., & Goldsmith, C. H. (2013). A tutorial on sensitivity analyses in clinical trials: The what, why, when and how. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 92. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-92.

Théorêt, V., Hébert, M., Fernet, M., & Blais, M. (2021). Gender-specific patterns of Teen dating violence in Heterosexual relationships and their associations with attachment insecurities and emotion dysregulation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(2), 246–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01328-5.

Thomas, J. L., Lewis, J. B., Martinez, I., Cunningham, S. D., Siddique, M., Tobin, J. N., & Ickovics, J. R. (2019). Associations between intimate partner violence profiles and mental health among low-income, urban pregnant adolescents. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 19(1), 120. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2256-0.

Tingley, D., Yamamoto, T., Hirose, K., Keele, L., & Imai, K. (2014). Mediation: R Package for Causal Mediation Analysis. Journal of Statistical Software, 59(5). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v059.i05.

Truman, J., & Morgan, R. E. (2014). Nonfatal Domestic Violence, 2003–2012. The U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ 244697, 1–20.

Unger, J. B., Molina, G. B., & Teran, L. (2000). Perceived consequences of teenage childbearing among adolescent girls in an urban sample. Journal of Adolescent Health, 26(3), 205–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(99)00067-1.

Weightman, M. J., Knight, M. J., & Baune, B. T. (2019). A systematic review of the impact of social cognitive deficits on psychosocial functioning in major depressive disorder and opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Psychiatry Research, 274, 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.035.

Wiemann, C. M., Rickert, V. I., Berenson, A. B., & Volk, R. J. (2005). Are pregnant adolescents stigmatized by pregnancy? J Adolesc Health, 36(4), 352 e1-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.06.006.

Wincentak, K., Connolly, J., & Card, N. (2016). Teen dating violence: A Meta-Analytic Review of Prevalence Rates. Psychology of Violence. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040194.

Wolfe, D. A., Scott, K., Reitzel-Jaffe, D., Wekerle, C., Grasley, C., & Straatman, A. L. (2001). Development and validation of the conflict in adolescent dating relationships Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 13(2), 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.13.2.277.

Wolfe, D. A., Wekerle, C., Scott, K., Straatman, A. L., Grasley, C., & Reitzel-Jaffe, D. (2003). Dating violence prevention with at-risk youth: A controlled outcome evaluation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(2), 279–291. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.71.2.279.

Wood, M., & Barter, C. (2015). Hopes and fears: Teenage mothers’ experiences of intimate Partner violence. Children & Society, 29(6), 558–568. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12100.

Xia, M., Fosco, G. M., Lippold, M. A., & Feinberg, M. E. (2018). A developmental perspective on young adult romantic relationships: Examining family and individual factors in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47, 1499–1516. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0815-8.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Rowan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Institutional Review Boards of Rowan University (No. Pro2016000980) and Cooper Health System (No. 15-141EX).

Consent to Participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Competing Interests

The authors have no known financial or non-financial conflict of interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wallace, L.C., Jones, M.C., Angelone, D.J. et al. Young Mothers and Dating Violence: An Examination of Depressive Symptomatology and Interpersonal Competency. J Fam Viol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-024-00688-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-024-00688-x